dbce8875d19e42db9902710f3b92e4b1.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 147

International Business Economics Lecture Notes Christos Pitelis January 2004

2 Contents 1. Introduction: Globalisation (Nature, Evolution, Perspectives) 2. Why Multinational Corporations (MNCs) and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)? 3. Strategy and Strategic Options of MNCs 4. MNCs, Government Policy and (Inter)national Competitiveness - Overall Conclusion and the Future of MNCs

International Business Economics Session 1 Introduction: ‘Globalisation’ (Nature, Evolution, Perspectives)

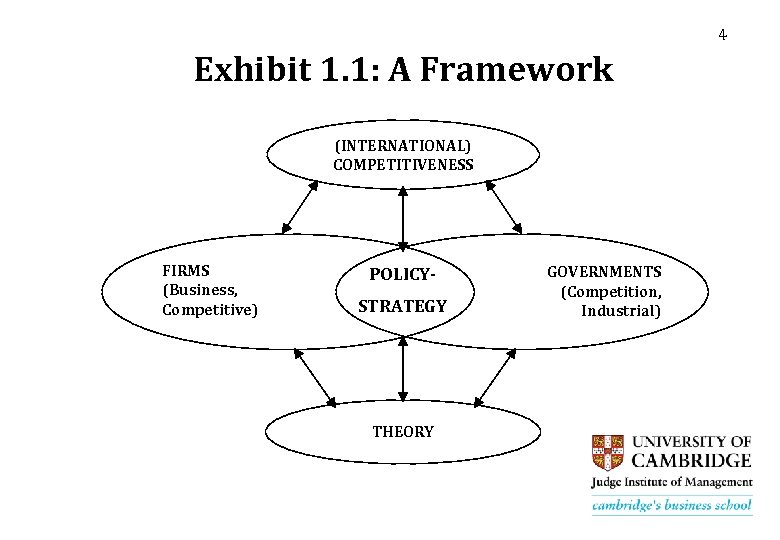

4 Exhibit 1. 1: A Framework (INTERNATIONAL) COMPETITIVENESS FIRMS (Business, Competitive) POLICYSTRATEGY THEORY GOVERNMENTS (Competition, Industrial)

5 The Nature and Scope of International Business • International Business (IB) deals with the nature, strategy and management of international business enterprises and their effects on business and national performance (e. g. , efficiency, growth, profitability, employment). • IB is interdisciplinary. It draws, among others, on economics, politics, sociology, marketing, management (human resources, strategic).

6 Some definitions (i) • FDI is the control of production which takes place in one country (‘host country’) by a firm based in another country (‘home country’). FDI is the defining feature of the multinational corporation (MNC). • Globalisation refers to the increasing integration of markets (exchange) and production, to include the mobility of resources (capital, labour, ‘organization and knowledge’).

7 Some definitions (ii) • A firm is an organisation which produces commodities for sale in the market for a profit, and allocates resources (such as capital and labour) without direct reliance on the price mechanism (the market) on the basis of internal entrepreneurial decisions (hierarchy). • An MNC is a firm which controls production in countries other than (and including) its home base.

8 Some definitions (iii) • The market (price mechanism) is an institution of resource allocation, based on voluntary exchanges (transactions) by individuals, motivated by preferences and market prices. • The state is an institution which allocates resources and influences the organization of economic activity through a legal monopoly on force.

9 Origins of IB (i) • IB is the result of the internationalisation of production and the emergence of the multinational corporations (MNCs), the subject matter of IB. • Internationalisation of production (‘globalisation’) involves international capital flows, international trade of commodities (exports-imports) and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) by MNCs.

10 Origins of IB (ii) • Until the 1980 s, there has been a tendency towards concentration of industry, and oligopolistic market structures. Firms have observed a ‘law of increasing size’ consisting of four stages: – First, the owner managed and controlled small firm (nineteenth century). – Second, the public limited ‘national’ company (limited liability, separation of ownership from management). – Third, the multidivisional (M-form) organisation (division- based), separation of strategic (long term) and operational (day-to-day) decisions. – Fourth, multinational corporations (MNCs) with production activities outside (and including) their home-base.

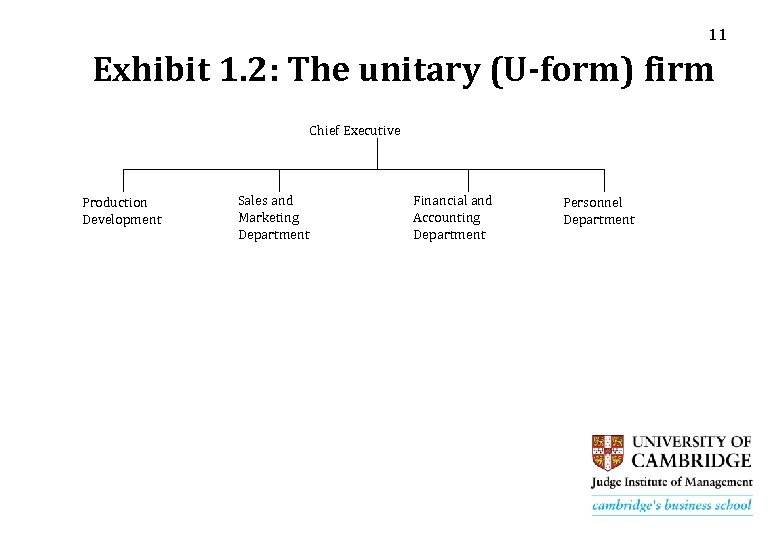

11 Exhibit 1. 2: The unitary (U-form) firm Chief Executive Production Development Sales and Marketing Department Financial and Accounting Department Personnel Department

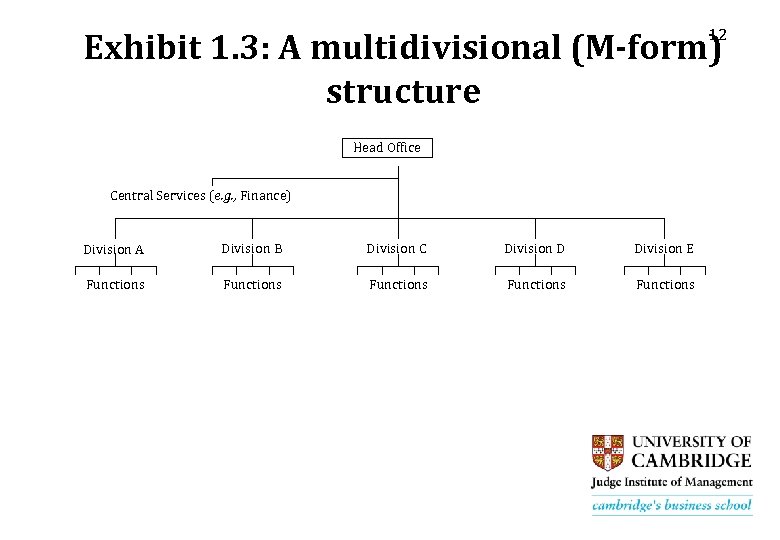

12 Exhibit 1. 3: A multidivisional (M-form) structure Head Office Central Services (e. g. , Finance) Division A Division B Division C Division D Division E Functions Functions

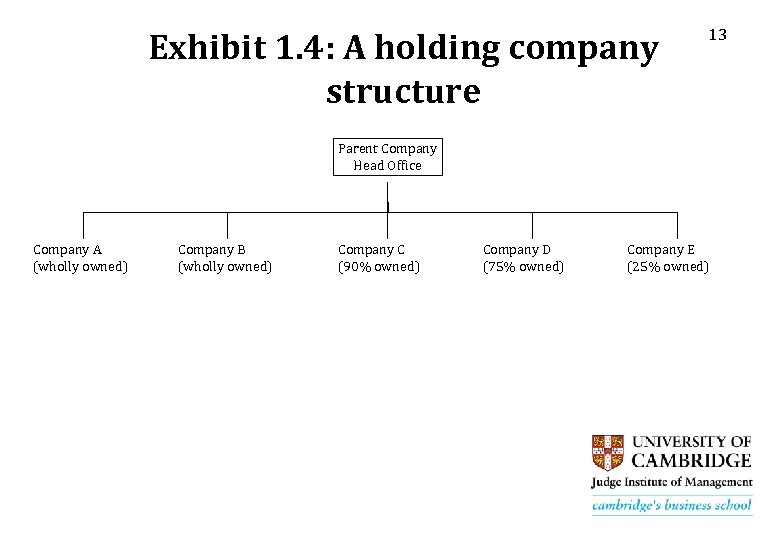

Exhibit 1. 4: A holding company structure 13 Parent Company Head Office Company A (wholly owned) Company B (wholly owned) Company C (90% owned) Company D (75% owned) Company E (25% owned)

14 Some facts and trends in IB (i) • International trade inside the world’s largest 350 MNCs accounts for almost 40 per cent of world merchandise trade. • The world’s largest MNCs (e. g. , General Motors, Exxon, Microsoft etc) have annual sales higher than the annual gross national product (GNP) of all but around 15 nation states. • In the early 2000 s in the USA, nearly half of manufacturing exports and around two thirds of imports were flowing within MNCs (intra-firm trade).

15 Some facts and trends of IB (ii) • FDI increased by over 20 per cent between 1985 and 2000, twice the growth rate of exports or output. • In the period 1991 -2000, 63 per cent of global FDI flows was received by the developed countries (DCs) (down from almost 80% in 1989), around 33 per cent by developing countries and just over 3 per cent by Eastern European countries. • Among the developing countries, China receives the lion’s share of FDI.

16 Some facts and trends of IB (iii) • Within the DCs, the US, the UK, Canada, France and Germany are leading players. • Since 1960 the relative importance of the US and the UK as sources of outward FDI has been declining. • In the ‘Triad’ (Europe, USA, Japan), total FDI between US and the EU was almost one third of global FDI in 2000. • European FDI is largely due to M&As. • FDI declined sharply in 2001 (over 50%, the largest drop in 30 years), 2002 and 2003.

17 Some issues in IB (i) • The main issues which arise from the facts and trends of FDI concern the following: – Why international production, FDI and MNCs? – How do (should) MNCs conduct their business strategies? (competitive and corporate strategies)

18 Some issues in IB (ii) • What is the relationship between MNCs, nation states (in developed and developing countries) and international organisations and what is the impact of MNCs on growth and development? • What is the link between MNCs and international competitiveness?

Background 1 (pp 20 -28, starts here): Firms & Industries

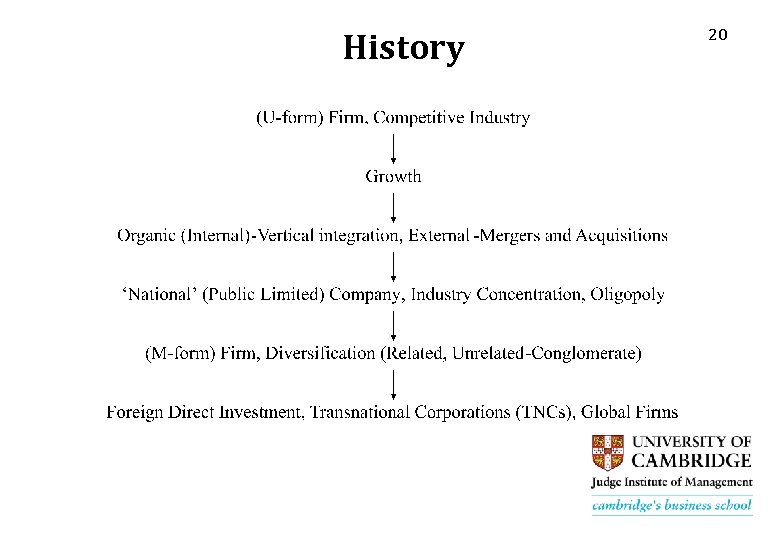

History 20

21 Firm integration “Strategies” • Vertical Integration (VI): Backward (raw materials) and forward (distribution). • Mergers and acquisitions (M&A): coming together of two or more firms. • Conglomerate diversification: operations-expansion of firms in ‘unrelated’ products-markets. • Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and MNCs. • ‘Hybrid’ (networks, clusters, joint ventures, strategic alliances …)

22 Main perspectives • (Market) Power: Firms pursue profit and/through (market) power. • Efficiency: Firms pursue profit through reduction of production and transaction costs. • Hybrid: Firms pursue profits through efficiency and (market) power.

23 Theories (i) • Neoclassical: Firm is ‘a production function’, a ‘black box’; it is concerned with the industry price-output ‘equilibrium’, which maximizes profits. Price-output equilibria depend on market structure, e. g. , perfect competition, monopoly. – Managerial: Firms maximize utility of managers, e. g. , sales revenue, growth. Based on alleged ‘separation of ownership from control’. – Transaction Costs: Firms are multi-person hierarchies which result from, and give rise to reduced market transaction costs, resulting in efficient industry structures.

24 Theories (ii) • Resource-Based: Firms are bundles of human and non-human resources under administrative coordination. There are internal and external stimuli to growth which lead to industry concentration. • Behavioural: Given ‘bounded rationality’ and different objectives of groups within them, firms do not maximize, they ‘satisfice’.

25 Theories (iii) • ‘Austrian’ - Chicago School - Schumpeterian: Alert, profit seeking entrepreneurs, enhance market co-ordination and give rise to ephemeral monopoly profits, eroded through competitive process of ‘creative destruction’ (innovations). • ‘Marxist’: Firms produce commodities for sale in the market for a profit, under hierarchical control of capital over labour. Dialectic link between competition and monopoly, for maintenance of monopoly (power).

Some critical elements for economic analysis (DISCO) (i) 26 • Demand (D): The demand conditions firms face, in the form of a Demand Curve, derived from ‘Theory of Demand’. • Industry Structure (IS): The extent of industry concentration, barriers to entry, etc, leading to competitive, imperfectly competitive, oligopolistic, or monopolistic industry structures.

Some critical elements for economic analysis (DISCO) (ii) 27 • Costs (C): The cost conditions faced by the firm, in the shape of a Cost Curve, derived from ‘Theory of Production and Costs’. • Objectives (O): The firms’ aim. It allows the derivation of price-output ‘equilibria’. Usual assumption is profit maximization (Marginal Cost equals Marginal Revenue). Others are maximization of sales revenue or growth. Alternatives are ‘satisficing’, ‘entrepreneuring’…

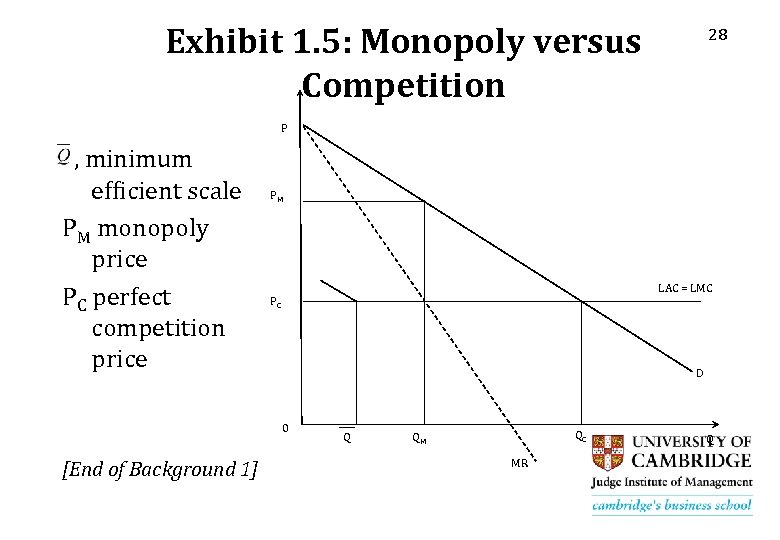

Exhibit 1. 5: Monopoly versus Competition 28 P , minimum efficient scale PM monopoly price PC perfect competition price PM D 0 [End of Background 1] LAC = LMC PC Q QC QM MR Q

29 ‘Globalization’: causes • Firm growth because of – Use of excess internal resources at near zero marginal cost – Sale of products to new markets at high profit rates (due to high fixed costs).

30 ‘Globalization’: facilitators • Reductions in transportation costs. • Improvements in information and communication technologies.

International Business Economics Session 2 Why MNCs and FDI?

32 The Multinational Corporation (MNC) • Definition – MNC = firm which controls production across national boundaries through intra-firm (nonmarket) operations. • Question – Why MNCs as opposed to exports, franchising, licensing, etc. ?

Background 2 (pp 32 -65, starts here): Perspectives on theory of firm

34 The Neoclassical analysis (i) Simple Market Structure Analysis (Perfect Competition vs Monopoly) • Perfect Competition defined: Market structure characterised by a large number of profit maximising buyers and sellers selling homogeneous products, and no entry barriers. • Result: Price taking behaviour, price at minimum long run average cost (LAC) curve Þ ‘normal’ profits.

35 The Neoclassical analysis (ii) • Monopoly defined: market structure characterised by a single profit maximising producer and very high entry barriers (no entry). • Result: monopoly prices exceeding minimum LAC Þ ‘Excess’ (monopoly) profits. • Conclusion: departures from perfect competition result in increases in prices and reductions in output. Also to ‘welfare losses’ due to ‘monopoly power’.

The Neoclassical analysis (iii) Oligopoly • Defined: market structure characterised by interdependence of (usually a small number of) producers-firms. Duopoly is the case of two firms. 36

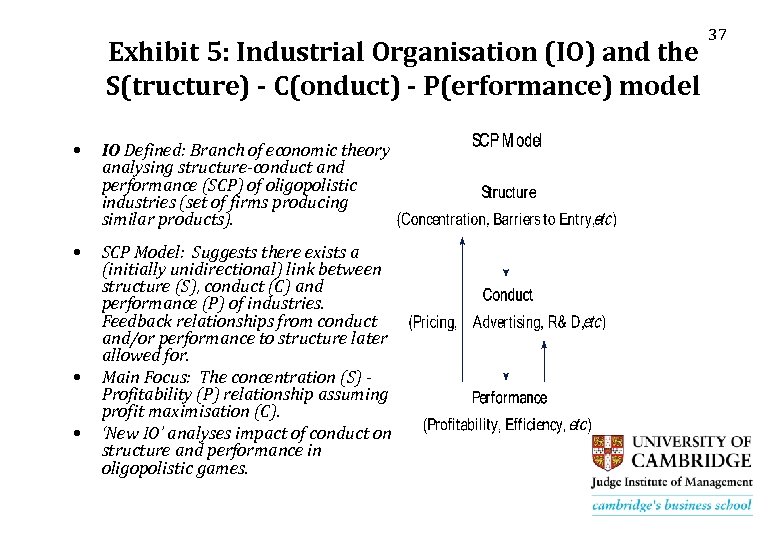

Exhibit 5: Industrial Organisation (IO) and the S(tructure) - C(onduct) - P(erformance) model • IO Defined: Branch of economic theory analysing structure-conduct and performance (SCP) of oligopolistic industries (set of firms producing similar products). • SCP Model: Suggests there exists a (initially unidirectional) link between structure (S), conduct (C) and performance (P) of industries. Feedback relationships from conduct and/or performance to structure later allowed for. Main Focus: The concentration (S) Profitability (P) relationship assuming profit maximisation (C). ‘New IO’ analyses impact of conduct on structure and performance in oligopolistic games. • • 37

Theoretical specification of industry structures 1. Limit pricing 2. Unconstrained profit maximizing oligopoly 3. Contestable markets 38

39 1. Limit Pricing • Assumes constrained profit maximisation (maximum profits subject to no entry), barriers to entry (minimum efficiency scale) and that incumbents leave post-entry output at pre-entry levels and entrants know this. • Result: Limit price derives from limit output found by subtracting the minimum efficient scale level of output from the perfect competition level.

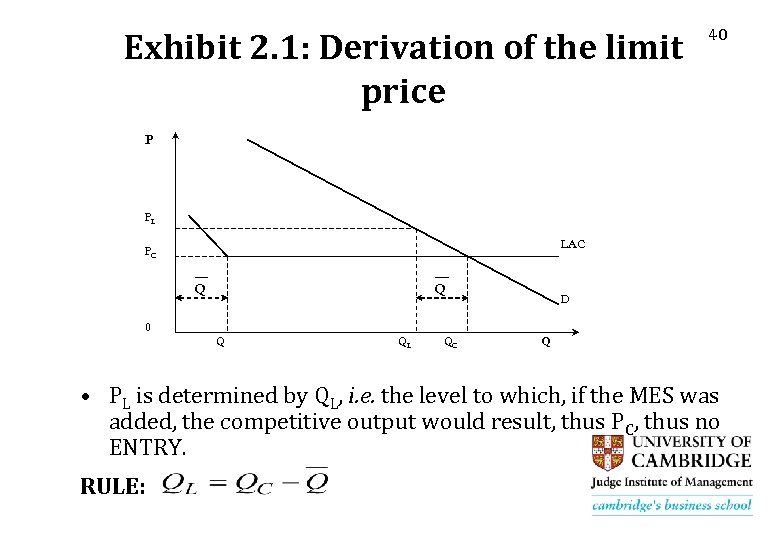

Exhibit 2. 1: Derivation of the limit price 40 P PL LAC PC Q Q D 0 Q QL QC Q • PL is determined by QL, i. e. the level to which, if the MES was added, the competitive output would result, thus PC, thus no ENTRY. RULE:

2. Unconstrained profit maximising oligopoly • Assumes blockaded entry and joint profit maximising price-output levels (Monopoly). Entry is blockaded through strategic entry barriers, e. g. , investment in excess capacity. 41

42 3. Contestable markets • Assume free entry and costless exit. This ensures perfectly competitive price-output levels, even in the presence of economies of scale and oligopolistic market structures, as any departures from perfectly competitive prices lead to hit-and-run entry and exit.

43 IO models compared • Main issue is the nature and importance of entry barriers, both ‘innocent’/structural (scale economies) and strategic (conscious actions by incumbents designed to deter entry), e. g. , excess capacity, product proliferation. • Well analysed strategic entry deterrence strategy, the investment in ‘excess capacity’. In the limit even monopoly pricing is sustainable if incumbents have excess capacity sufficient to produce full perfect competition output. To be credible, excess capacity investment should be optimal post-entry.

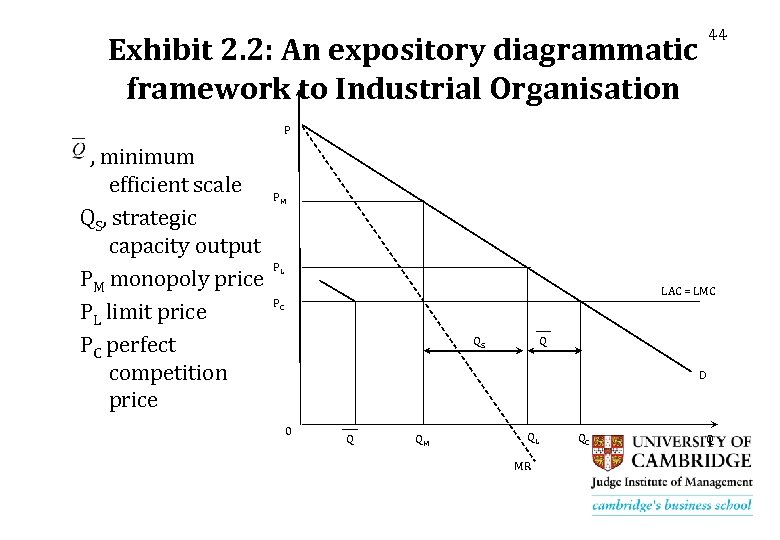

44 Exhibit 2. 2: An expository diagrammatic framework to Industrial Organisation P , minimum efficient scale QS, strategic capacity output PM monopoly price PL limit price PC perfect competition price PM PL LAC = LMC PC QS Q D 0 Q QM QL MR QC Q

45 Firm-industry structures and business strategy • Oligopoly, crucial for (competitive) strategy, which is absent in cases of both perfect competition and monopoly. Emergence and effects of oligopoly analysed by theory of Industrial Organization (IO), which is based on and extends the Cournot/Bertrand models of oligopoly. • M-Form organisation is important condition for development of corporate strategy (existence of multitude of business units).

Theory of Firms & Industries: Alternative Perspectives • Transaction Costs, Markets and Hierarchies • Resource-Based and related perspectives 46

Transaction Costs, Markets & Hierarchies (i) • Origin: Coase (1937) • Assumptions i) Market is ‘original’ means of resource allocation => ii) Existence of hierarchies (e. g. , firms) due to market failure • Nature of market failure – Cognitive (natural) not structural; i. e. , due to transaction costs and not monopoly power. 47

Transaction Costs, Markets & Hierarchies (ii) 48 • (Market) Transaction Costs are costs of information, bargaining, contracting, policing and enforcing agreements. • Main Proposition (Coase, Williamson, etc. ): internalization of markets by hierarchies, i. e. , replacement of voluntary exchanges with hierarchy => savings in transaction costs => hierarchy (firm) more efficient way to allocate resources. • Horizontal and vertical integration, the M-form, and conglomeration result from pursuit of transaction cost reductions.

Transaction Costs, Markets & Hierarchies (iii) 49 • Policy Implications – In neoclassical approach departures from perfect competition => market failure (structural) => => need for government intervention. – In transaction costs approach hierarchies (including Mform conglomerates and MNCs) = efficiency improving solutions to (natural) market failure => => less need to interfere with the markets.

50 Resource-based & related perspectives (i) • Early work by Penrose (1959) – Firm = “a collection of resources bound together in an administrative framework, the boundaries of which are determined by the ‘area of administrative co-ordination and authorative communication’” (Penrose, 1995, p xi). – Focus on ‘the internal resources of the firm’, then the external environment. Latter is different for each firm depending ‘on its specific collection of human and other resources’. Environment can be manipulated by firms to serve their objectives.

51 Resource-based & related perspectives (ii) • Dynamic interaction between internal and perceived external environment (‘image’, and ‘productive opportunity’). • Endogenous Growth, results from i) resource indivisibility, ii) knowledge creation within firms, which releases resources. • A firm’s prospects are in terms of existing and new products; diversification as new markets become relatively more attractive than existing ones.

52 Resource-based & related perspectives (iii) • Knowledge is tacit. • ‘History matters’, growth is an evolutionary process, based on cumulative growth of collective knowledge in the context of a purposeful firm. • Rate of firm’s growth limited by growth of knowledge within it, and a firm’s size by the extend to which administrative effectiveness continues to reach expanding boundaries.

53 Resource-based & related perspectives (iv) • Firm strategies result of differential capability, e. g. , – Vertical Integration, due to ability of firms to serve their own needs better. – Diversification, due to growth and multiple applicability of resources. – Mergers and Acquisitions; to acquire managerial resources for expansion. – MNCs, due to differential ability e. g. , in transferring tacit knowledge (Kogut-Zander).

54 Resource-based & related perspectives (v) (Nelson & Winter, 1982) • In Nelson and Winter’s evolutionary theory of the firm, routines, search (changes in routines) and competition are economic analogues to genes, heredity and struggle for existence in biology.

55 Resource-based & related perspectives (vi) (Capabilities-based) • Use and develop hard to imitate and costly to apply internal capabilities. • Rents in equilibrium.

56 Resource-based & related perspectives (viii) (knowledge-based theories, Penrose, etc. ) • Firms better than markets in using, preserving, transferring and developing knowledge. • Value creation – growth through knowledge and value appropriation.

57 Resource-based & related perspectives (ix) (Richardson and co-operation) • “Dense network of co-operation and affiliation by which firms are inter-related. ” • Markets, hierarchy and networks are a function of degree of complementarity and similarity of activities – weakly complementary activities => MARKET – complementary and similar activities => HIERARCHY – complementary and dissimilar activities => COOPERATION [End of Background 2}

58 Theories of the MNC • Two main types: - Supply-side - Demand-side - Other factors – “theories” • Supply-side theories. Mainly - Monopolistic – ‘ownership’ advantage - Transaction costs and internalisation - Eclectic theory (or Ownership, Location, Internalisation - OLI paradigm) - Divide and rule - Resource-based

59 Supply-side theories: Monopolistic ‘ownership’ advantage (i) • Origin: Hymer’s 1960 Ph. D thesis • Assume: ‘Law of increasing firm size’: Firms growth leads to concentration and acquisition of monopolistic advantages (MAs). – Firms’ pursuit of (monopoly) profit => seeking overseas markets. – MAs allow firms to outcompete foreign rivals. – MNCs aim at reducing conflict.

60 Supply-side theories: Monopolistic ‘ownership’ advantage (ii) • Choice of FDI over market-based alternatives due to control potential and oligopolistic interaction. • Collusion allows reduction of conflict and maintenance of monopoly profits. • Conclude: Structural market failure => MNCs => (international) structural market failure

61 Supply-side theories: Transaction costs - internalization (i) • Existence of firms => Economising in transaction costs => Firms more efficient than markets • In case of MNCs, choice is between market transactions, e. g. , exporting, licensing and nonmarket transactions, i. e. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

62 Supply-side theories: Transaction costs - internalization (ii) • Reasons for FDI – Williamson: asset specificity => hold-up problems => need for fully owned subsidiaries (FDI). – Buckley & Casson: intangible assets exhibit ‘public goods’ attributes, thus result in appropriability problems => market failure. – Hennart: internalization of markets due to differential ability to control (overseas) labour.

63 Supply-side theories: Transaction costs - internalization (iii) • Conclusion Internalization of markets through MNCs are efficient solution to intrinsic (transaction costsrelated) market failure.

Supply-side theories: Eclectic theory (or ‘OLI paradigm’) 64 • Dunning, combined a and b as well as location advantages to provide ‘eclectic theory’ or O(ownership), L(ocation), I(nternalization) paradigm. • OLI explains internationalization of production, not the MNC. – O explains why firms are able to become MNCs. – I explains why they benefit from internalizing markets or advantages. – L explains the choice of location.

Supply-side theories: Divide and Rule (Sugden) 65 • Builds on Marglin-Hymer • Focuses on labour markets. He suggests that a reason for MNCs is their ability to divide labour (unions) in country specific groups => Reduce their bargaining power => increase their profits.

Supply-side theories: Resource-based 66 (Penrose, Teece, Kogut-Zander) • MNCs are due to endogenous growth and differential capabilities vis-à-vis market and other firms. • Growth can be national (diversification) or geographical (MNC). • MNCs are better in transferring internationally tacit knowledge than markets.

67 Demand-side theory (i) • Cowling & Sugden, Pitelis: increased concentration => increased profits => reduced consumers expenditure (because a lower proportion of profit is consumed than of wage income). • As consumption decreases so does effective demand => going overseas for demand outlets.

68 Demand-side theory (ii) • The MNC as an All Weather Company – Diversified national firms can ride the industry life cycle (Hymer). – MNCs can ride the national business cycle, becoming All Weather Companies.

69 Other factors – ‘theories’ • Oligopolistic rivalry – Present in most theories (except transaction costs). – Can motivate - shape firms’ payoff matrix => crucial context within which decisions are taken. – Specifically oligopolistic interaction theories (e. g. , Graham), build on Hymer and emphasize role of threats and counter-threats. • Competition between states – Nation states may promote their own MNCs to affect their international competitiveness – could explain some LDC MNCs.

70 Synthesis (i) • Context: Oligopolistic interaction – Endogenous growth (Penrose) => monopolistic advantages (Hymer). – MAs are an inducement to innovation and further growth (Penrose); they can help firms outcompete foreign rivals (Hymer). – Domestic diversification due to pull factors, e. g. , multiple use of resources (Penrose), or push factors, e. g. , the product life cycle (Hymer).

71 Synthesis (ii) • Geographical diversification also due to national-regional business cycles (all weather company). • Mode of expansion due to differential firm capabilities (Penrose, Teece, Kogut & Zander), (dynamic) transaction costs (Teece, Buckley & Casson) and overall control advantages (Hymer). • Locational factors explain the choice of location. • No general theory possible, but a general framework within which each case can be examined.

72 MNCs impact on welfare • Monopolistic advantage theory => possibility of reduced competition due to MNCs => (Pareto) inefficiency á • Internalization hypothesis => transaction reductions => efficiency. • Eclectic view => advantages and disadvantages => ‘trade-off’. • Divide and rule hypothesis => reduced workers welfare => (Pareto) inefficiency. • Resource-based => efficiency and inefficiency may co-exist • Synthesis => coexistence of efficiency and power => ‘trade-off’.

The MNC and ‘Uneven Development’(Hymer) 73 • For Hymer (1972), the operations of MNCs tend to globalize the tendency towards concentration; generate an uneven development between the centre (developed countries) and the periphery (less developed countries); erode the power of labour unions and the nation state, and tend to shape the world to their image by creating ‘superior’ and ‘inferior’ countries. They are responsible for the dependent industrialization of the Newly Industrialized Countries.

International Business Economics Session 3 Strategy and Strategic Options of MNCs

Background 3 (pp 83 -99, starts here) Business Strategy

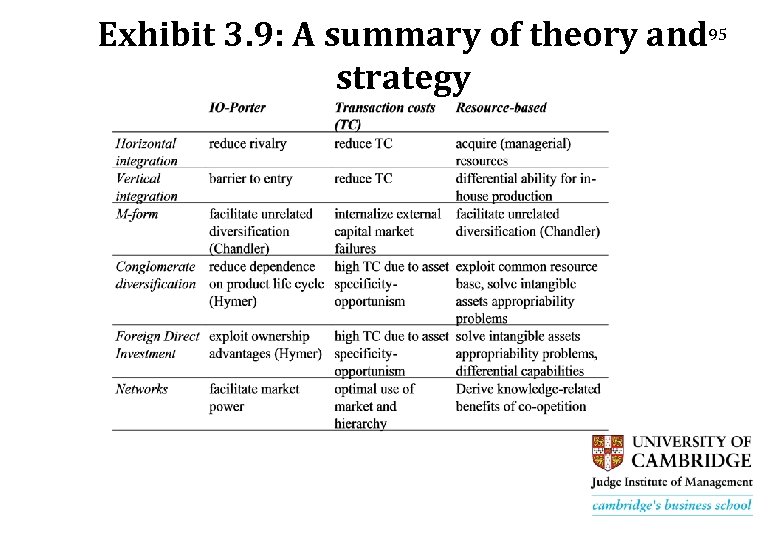

Business Strategy (i) • Firms’ evolution – strategies – – – Horizontal integration (mergers and acquisitions) Vertical integration (backward and forward) Multidivisional (M-) form (business units under central control) Conglomeration (unrelated business activities) Foreign Direct Investment - multinational corporations (foreign direct investment) – Networks, alliances clusters, joint ventures, etc. All such strategies involve future cash flows, thus require ‘capital budgeting’. 76

77 Business Strategy (ii) • Types of strategy – Competitive: Strategy of Business Units – Corporate: Strategy of firm as a whole

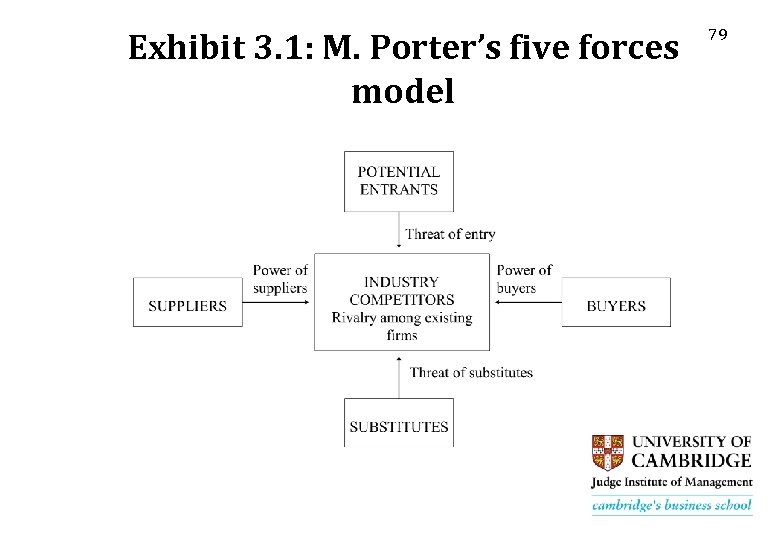

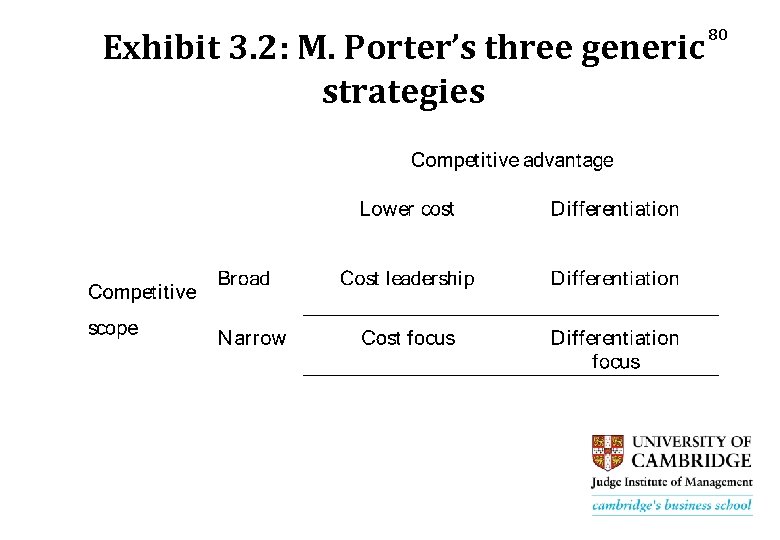

78 Competitive Strategy Porter: based on IO • ‘Five forces’ model (rivalry of existing competitors, potential entrants, power of suppliers-buyers, substitute products). Rule: select and/or create ‘attractive industries’ (with weak forces of competition) • Three generic competitive strategies (cost leadership, differentiation, focus). Rule: do not get stuck in the middle.

Exhibit 3. 1: M. Porter’s five forces model 79

Exhibit 3. 2: M. Porter’s three generic strategies 80

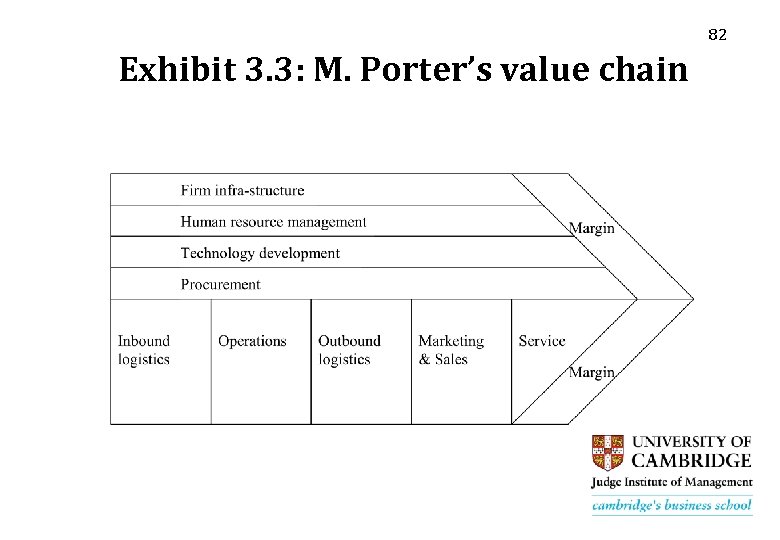

Competitive Strategy Porter (cont’d) 81 • Value chains: firm’s primary and support activities that generate value (margin) – primary: firm infrastructure, human resource management, technology development, procurement – support: inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, service Rule: align value chain to generic strategy

82 Exhibit 3. 3: M. Porter’s value chain

83 Corporate Strategy • Portfolio models - Boston Consulting Group, etc. • Porter • Resources-capabilities

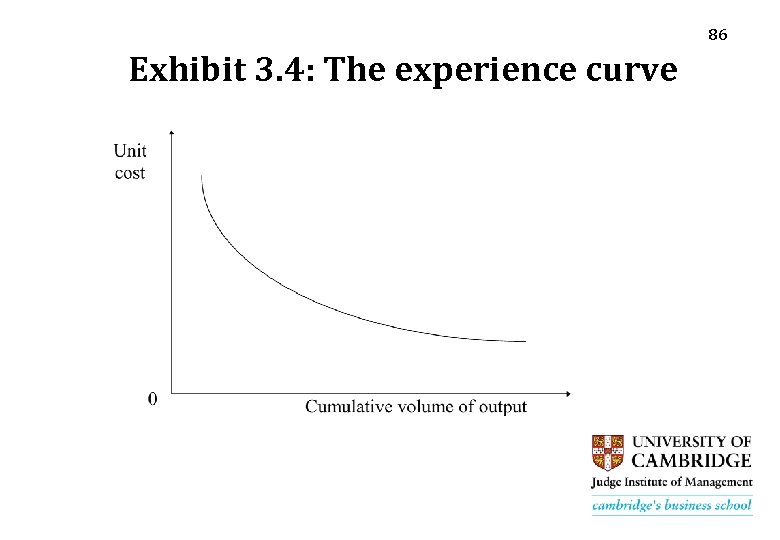

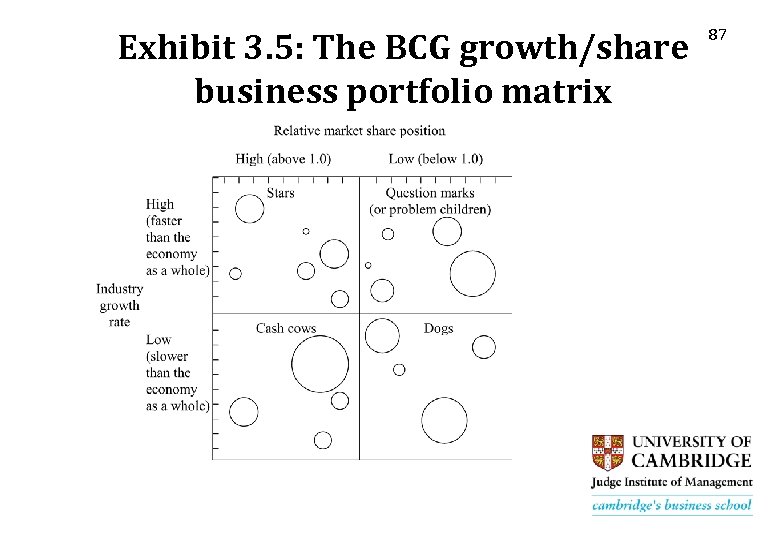

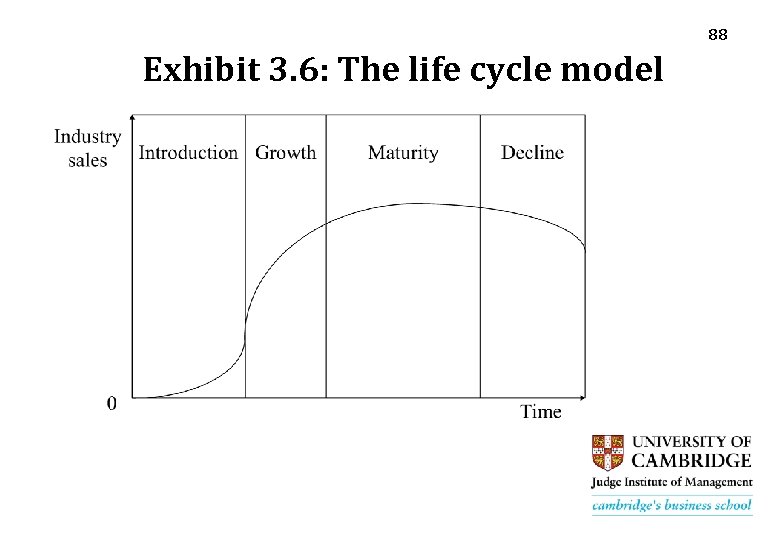

Corporate Strategy: Portfolio models - The Boston Consulting Group (i) 84 • Learning and experience gives rise to reduced unit costs as volume increases • Market share increases profitability • Portfolio matrix: to classify business units as stars, cash cows, question marks and dogs on the basis of industry growth rates and business units’ relative market share Rule: cash-in cash cows, to invest in stars and selected question marks, stars-to-be. Liquidate dogs.

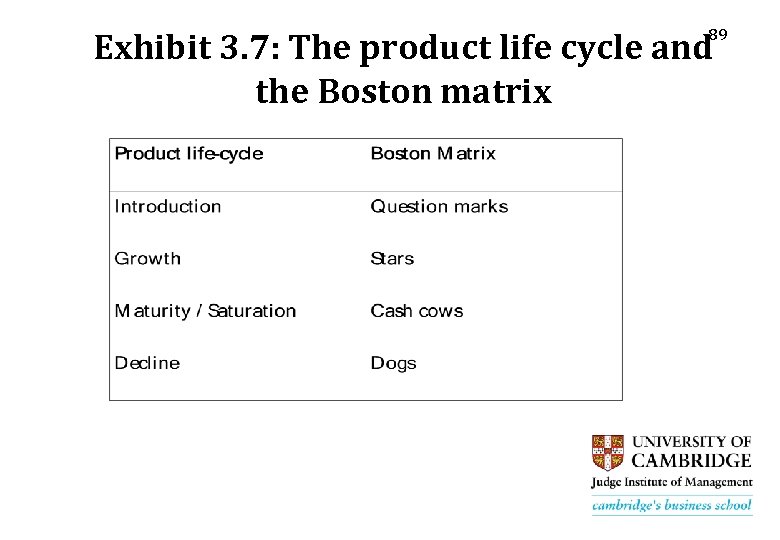

85 Corporate Strategy: Portfolio models. The Boston Consulting Group (ii) • BCG matrix related to the industry product life cycle (introduction-question marks, growth-stars, maturity/saturation-cash cows, decline-dogs). • Portfolio Models: Shell, General Electric – same principle as BCG, different criteria and classifications

86 Exhibit 3. 4: The experience curve

Exhibit 3. 5: The BCG growth/share business portfolio matrix 87

88 Exhibit 3. 6: The life cycle model

89 Exhibit 3. 7: The product life cycle and the Boston matrix

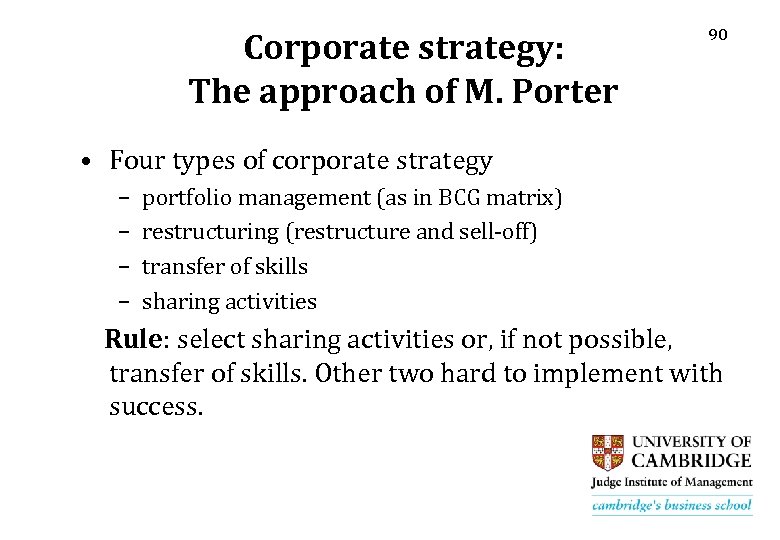

Corporate strategy: The approach of M. Porter 90 • Four types of corporate strategy – – portfolio management (as in BCG matrix) restructuring (restructure and sell-off) transfer of skills sharing activities Rule: select sharing activities or, if not possible, transfer of skills. Other two hard to implement with success.

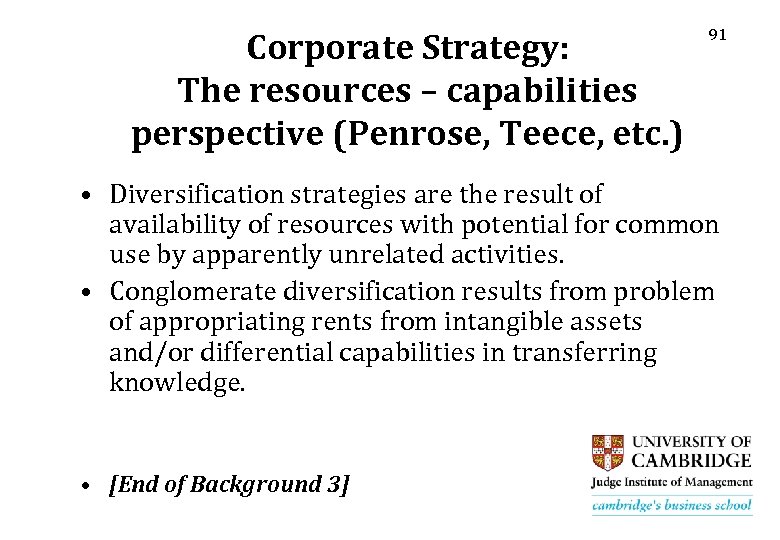

Corporate Strategy: The resources – capabilities perspective (Penrose, Teece, etc. ) 91 • Diversification strategies are the result of availability of resources with potential for common use by apparently unrelated activities. • Conglomerate diversification results from problem of appropriating rents from intangible assets and/or differential capabilities in transferring knowledge. • [End of Background 3]

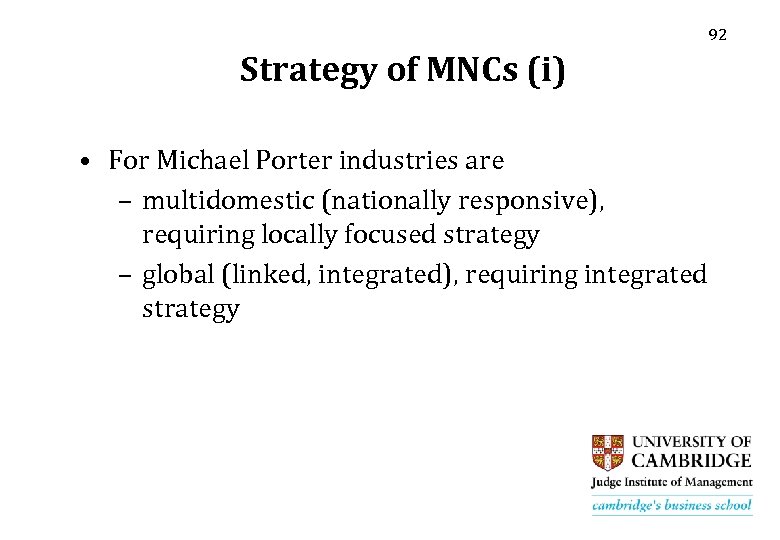

92 Strategy of MNCs (i) • For Michael Porter industries are – multidomestic (nationally responsive), requiring locally focused strategy – global (linked, integrated), requiring integrated strategy

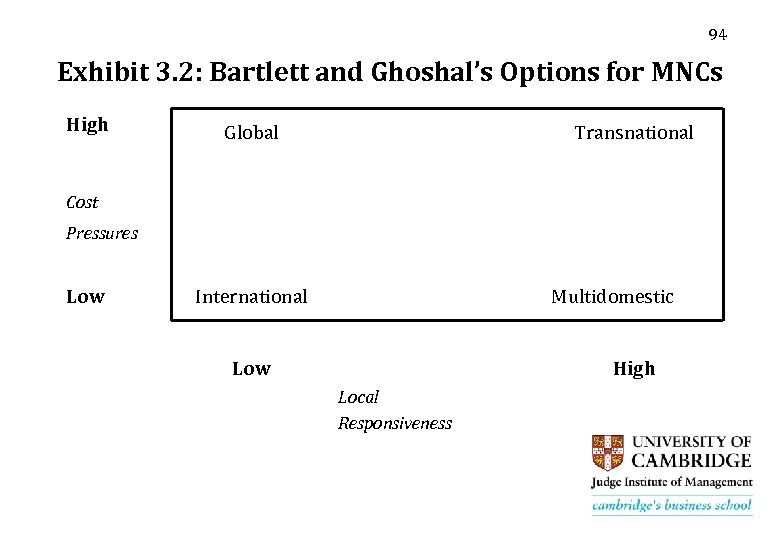

93 Strategy of MNCs (ii) • For Bartlett and Ghoshal: four basic strategies emerge on the basis of cost pressures – local responsiveness matrix: – – international (low, low) multidomestic (low, high) global (high, low) transnational (high, high)

94 Exhibit 3. 2: Bartlett and Ghoshal’s Options for MNCs High Global Transnational Cost Pressures Low International Multidomestic Low High Local Responsiveness

Exhibit 3. 9: A summary of theory and 95 strategy

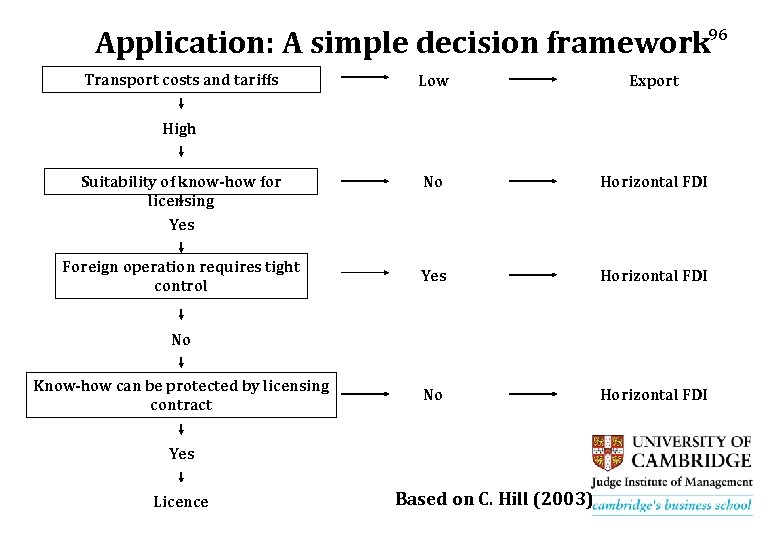

Application: A simple decision framework 96 Transport costs and tariffs Low Export No Horizontal FDI Yes Horizontal FDI No Horizontal FDI High Suitability of know-how for licensing Yes Foreign operation requires tight control No Know-how can be protected by licensing contract Yes Licence Based on C. Hill (2003)

International Business Economics Session 4 MNCs, Government Policy and (Inter)national Competitiveness

98 Competitiveness: definition • Differential productivity, value-added – wealth creation, relative to other economic units (firms, regions, nations…) • Can be achieved through – Business policies – Government (competition, industrial and competitiveness) policies

99 Competition and Industrial Policy • Early competition-industrial policies in West derive from IO theory, in particular the issue of the welfare effects of monopoly (power). This includes analysis of i) Static effects (monopoly and reduced consumer welfare, due to high prices); ii) Dynamic effects (e. g. , monopoly and innovation).

Monopoly & international competitiveness (i) 100 • Main claim that large firms can exploit economies of scale and scope, therefore can compete with large firms from other countries. • Idea particularly prevalent is 1960 s and 1970 s in Europe, in part as response to the ‘American Challenge’, e. g. , Servan-Schreiber’s claim that US multinational corporations dominate technologically European markets. • If large size increases competitiveness (thus export surpluses) these could offset any static losses. • The international competitiveness idea is in part responsible for the permissive (and even encouraging) attitude of European countries to mergers and large size.

Monopoly & international competitiveness (ii) 101 • Counter arguments are: – i) higher X-inefficiency – ii) may suppress major inventions if they result in major re-equipment – iii) inflexibility • Schumpeter’s ‘Differential Innovations Hypothesis’, that large firms are large because they have been more successful innovators to start with.

102 Monopoly and Welfare Conclude • An open question whether the dynamic gains offset the static losses. Evidence inconclusive. • Focus on efficient resource allocation limited. Concentrate on resource creation?

Practice – The Western approach 103 Theoretical Basis i) ‘Competition policy’ to correct market failure due to monopoly (power) and its abuse: e. g. , Treaty of Rome, US Anti-Trust policies ii) Trade through (static) comparative advantage, lenient or encouraging attitude to multinational corporations (MNCs)

Practice – The Western approach (EU) (i) But in 1960 s • ‘Recognition’ in Europe of the ‘international competitiveness’ advantages of ‘large size’ (American challenge thesis) • Relatedly, – ‘National Champions Policy’ (e. g. , UK, France, Italy) – Nationalizations of ‘strategic’ sectors 1970 s • ‘Lame Ducks’ policies 104

Practice – The Western approach (EU) (ii) 105 1980 s • Return to the market (privatisations etc) and focus on ‘Government Failure’. 1990 s • Entrepreneurship and small firms • Horizontal measures, technology and education, tangible and intangible infrastructure, efficiency of public sector.

Practice – The Western approach (USA) 106 • Hidden industrial policy in the form of defence policy? • revival of 1990 s; clusters? Conclude • ‘Grant Theory’ but no industrial strategy including adhocity, discontinuity, undue focus on (dis)advantages of size and static comparative advantage-based (free) trade.

Practice – The Far Eastern approach (Japan) Basis: Industrial Strategy by Ministry of Trade & Industry (MITI) involving: i) Dynamic comparative advantage (created comparative advantage). ii) Managed trade, with initial focus on internal competition. iii) Management of competition (the ‘Golden Mean’) and cooperation. iv) Dynamic competition through innovativeness, as in Schumpeter - Hayek. 107

Practice – The Four Tigers 108 (Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong) (i) Basis: Similar to Japan, adaptive industrial strategy involving i) Import substitution. ii) Export promotion based on labour intensive manufacturing. iii) Promotion of high technology/high value added sectors. iv) Attraction of FDI (Singapore, Taiwan), technology transfer.

Practice – The Four Tigers 109 (Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong) (ii) • Relative success of ‘Far East’ – Result of multitude of complex factors which include culture, high saving, effective public administration, close relation between industry and finance, consensus, new (strategic) management techniques, etc. • Question: Can we exclude role of industrial strategy? Is it unrelated to the other factors?

110 New theories 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. ‘New Trade Theory’ ‘New Competition’ New location economics New (‘Endogenous’) Growth Theory MNCs, deindustrialisdation and ‘Competitive Bidding’

111 1. New trade theory (i) • Traditional focus of Western industrial policy, the welfare effects of monopoly and theory of (static) comparative advantage. According to this countries should specialize and trade in products in which they enjoy a comparative advantage. Benefits from trade arise when each country pursues such a strategy. • Presence of monopolistic competition, economies of scale, positive externalities and first mover advantages led to conclusion that focus on high return industries can affect the distribution of benefits (and even lead to losses, Krugman) – Strategic Trade.

112 1. New trade theory (ii) • This led to concept of dynamic comparative advantage; i. e. , attempts by countries to create (not accept the existing) comparative advantages. • Best known case of dynamic comparative advantage policy is Japan.

113 2. The New Competition (i) • Based on observation of successful industrial districts, in North Italy, Germany, USA, Cambridge UK, etc. • Such districts consist of small and medium sized, highly innovative, customer oriented firms, with a hands-on approach to management, which cooperate on issues of infrastructure, technology etc and compete in the market for customers. Often rely on support by state/local authorities, are based more on trust than hierarchical relations, try to ‘exploit’ the dispersed knowledge of their labour, suppliers etc and use new production methods such as Just-in-Time, etc.

114 2. The New Competition (ii) • Success of industrial districts questions benefits of large size and provides a different (“Post-Fordist”) model of industrial development. However, such methods are also adopted by major, particularly Japanese, MNCs, through e. g. , subcontracting.

3. New Location Economics (Krugman, Porter) • Importance of location in generating external economies, reducing transaction costs through trust, and further innovation. 115

4. New Endogenous Growth Theory (Lucas, Romer) 116 • Importance of human resources and technological change in effecting (‘endogenous’) macroeconomic growth.

5. MNCs, Deindustrialization and Competitive Bidding 117 • Link between multinational corporations and deindustrialization questions link between large size and international competitiveness • Main idea is that countries like the UK which suffer from deindustrialization tendencies are home bases of privately successful MNCs. This questions the benefits of large size for the case of MNCs home base. • In era of multinational corporations ‘name of the game’ that of ‘competitive bidding’, i. e. , attempt by governments to attract investments by home and foreign firms (MNCs).

118 Theory and Practice • Question: New approaches support/explain ‘Far Eastern’ miracle? • ‘New Industrial Strategy for Democracy’ (Cowling & Sugden) – MNCs give rise to multinationalism, centipetalism and short termism. Needed is a shift of power to communities and regions, e. g. , through appropriate ‘flexible specialization’ policies.

119 Preliminary Conclusion • Possibility for Machiavellian scenario i. e. , adaptive industrial strategy (in partnership with corporate sector) including i) dynamic comparative advantage ii) managed competition and co-operation iii) managed trade iv) playing the ‘competitive bidding game’ and/or v) tackling the challenge of MNCs vi) considering alternative forms of competitiveness, like ‘flexible specialization’

120 Developing countries • Some common features: small internal size of market, lack of large ‘national’ MNC’s (over-) reliance on small family run businesses, and foreign MNCs, relatively underdeveloped industry. • Possible Strategy: i) follow the ‘four tigers’ and ii) consider ‘appropriate’ focus on small and medium sized enterprise, flexible specialization, clustering. • Main issue: selection, suitability, transferability and feasibility of policies.

121 The Importance of Institutions (i) • Main problem of implementation, ‘government failure’. Although a general problem, often more acute in developing countries. Indeed underdevelopment may be the effect of inefficient property rights, and incentive mechanisms? (North) • Culture, consensus, other institutional constraints. • Need for promoting an institutional framework conducive to development. This includes addressing the problem of ‘capture’ of the state by MNCs.

122 The Importance of Institutions (ii) • Government can be enabling (reduce private sector transaction and production costs) to increase output. It can also be developmental, i. e. , try to improve the revenue side. • Analysis of the state suggests that problem of ‘capture’ reduced through pluralism of institutional forms (large and small firms) and competition in the political market. • ‘Capture’ effects support a competitiveness strategy favouring smaller firms (potential competition to established giants).

123 Conclusions (i) • Possible and necessary to devise a competitiveness strategy which learns from economic theory and international practice and addresses the issue of implementation (e. g. , institutions and ‘capture’ of the ‘state’) and for the EU its declared needs to promote Competition and Convergence

124 Conclusions (ii) • Developing countries should consider their policies in the above framework, striving for an emphasis on dynamic competition, value creation and supply-side convergence. Internally they should address the issue of the institutional constraints. • Identification and development of distinct capabilities and competencies of a nation and governments important condition for effective, implementable strategy.

125 ‘Anti-trust’ today: some problems • Potential problems with current policies i) Downplay lessons from the ‘Far East’ and the ‘new approaches’. ii) Do not address the problem of MNCs (as a potential threat to competition). iii) Ignore distribution issues, intra-EU and between EU and ‘The South’, which undermines sustainability. iv) Fail to provide supply-side incentives for convergence. v) Fail to distinguish between policies that re-distribute resources and policies that generate resources. • Need to move from competition to competitiveness policies

126 From competition to competitiveness policies: models of competitiveness • Neoclassical model – Competitive markets – Free trade • ‘Japanese’ • Porter’s ‘Diamond’ • Productivity-Competitiveness Wheel

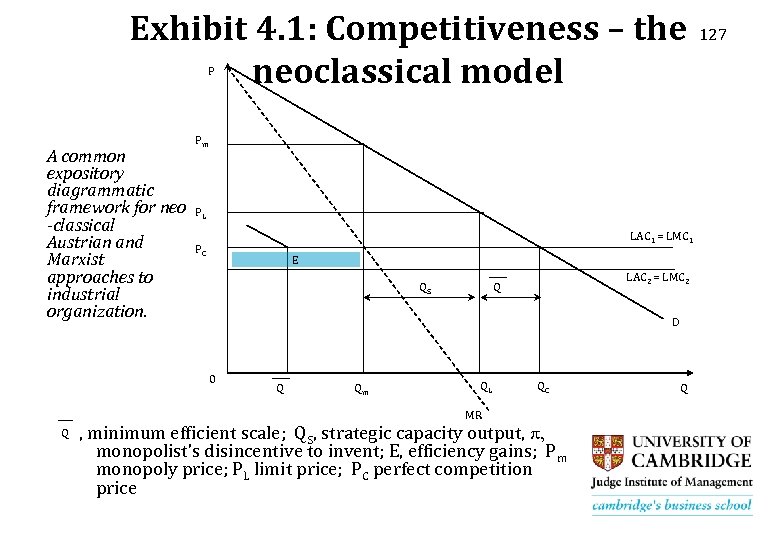

Exhibit 4. 1: Competitiveness – the neoclassical model P A common expository diagrammatic framework for neo -classical Austrian and Marxist approaches to industrial organization. Pm PL LAC 1 = LMC 1 PC E QS D 0 Q Qm QL MR Q LAC 2 = LMC 2 Q QC , minimum efficient scale; QS, strategic capacity output, p, monopolist’s disincentive to invent; E, efficiency gains; P m monopoly price; PL limit price; PC perfect competition price Q 127

128 Competitiveness (i) • The ‘Japanese’ approach ? – High knowledge intensive sectors

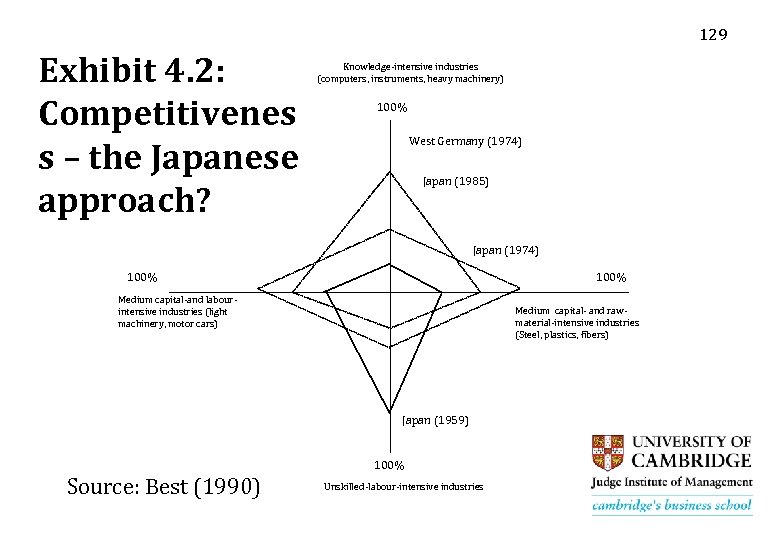

129 Exhibit 4. 2: Competitivenes s – the Japanese approach? Knowledge-intensive industries (computers, instruments, heavy machinery) 100% West Germany (1974) Japan (1985) Japan (1974) 100% Medium capital-and labourintensive industries (light machinery, motor cars) Medium capital- and rawmaterial-intensive industries (Steel, plastics, fibers) Japan (1959) 100% Source: Best (1990) Unskilled-labour-intensive industries

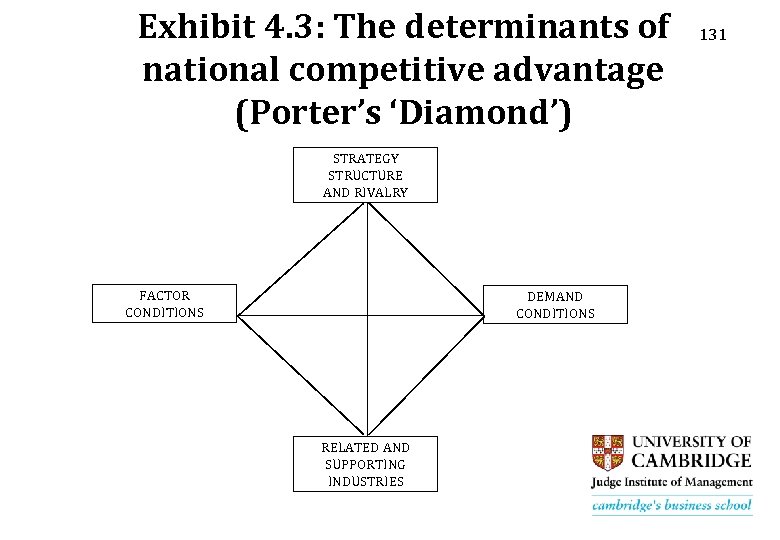

130 Competitiveness (ii) • Porter’s ‘diamond’ – Factor and demand conditions, clusters

Exhibit 4. 3: The determinants of national competitive advantage (Porter’s ‘Diamond’) STRATEGY STRUCTURE AND RIVALRY FACTOR CONDITIONS DEMAND CONDITIONS RELATED AND SUPPORTING INDUSTRIES 131

132 Problems with existing models • Absence of commonly agreed upon conceptual framework. • Absence of links between competitiveness at the firm-regional and national levels. • Insufficient analysis of determinants of productivity and competitiveness. • Insufficient treatment of the issue of sustainability.

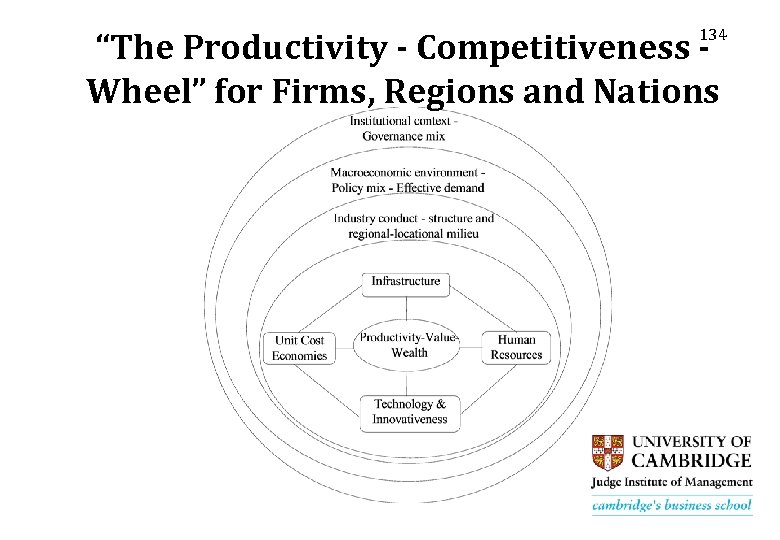

133 Sustainable Competitiveness and Development: a conceptual framework • The Productivity-Competitiveness Model – Competitiveness <=> Productivity - Value Creation • Determinants of Productivity - Value – Firm level • infrastructure • human resources • technology and innovation • unit costs economies – Regional and National levels: As above plus • Industry structure - conduct and regional - locational milieu • macroeconomic environment - policy mix • institutional environment - governance mix

134 “The Productivity - Competitiveness Wheel” for Firms, Regions and Nations

135 Main routes to competitiveness • Firm size & FDI by MNCs • Clusters of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs)

136 What are Clusters? • (Geographical) agglomerations of firms (and other organizations-institutions) linked horizontally (and/or vertically) intra- (and/or inter-) sectorally, in a facilitatory socio-institutional and cultural milieu, which compete & co-operate (co-opete) in (inter)national markets.

137 Clusters and the Wheel • Clusters => – innovation – reduced unit cost economies (economies of scale, scope, transaction costs, learning, external, diversity, etc. ) – better human resources – strong regional infrastructure – more facilitatory institutional context (through co-opetition, etc. )

Despite problems, clusters are important • Clusters improve innovation, productivity & competitiveness at the regional & national levels, they create employment and can lead to convergence. • Clusters are more bottom-up, thus help deepen democracy. • Problems include identifying nature, boundaries, strategies for sustained successful performance. 138

Foreign Direct Investment and Clusters 139 • Large firms and (through) foreign direct investment (FDI) can improve determinants of productivity, yet: – Hard for developing countries to attract FDI – Risk of FDI flight, given options, and flexibility of operations • Clusters have advantage over large firms and FDI because of local base and co-opetitive nature. • Clusters attract FDI and embed it in localities.

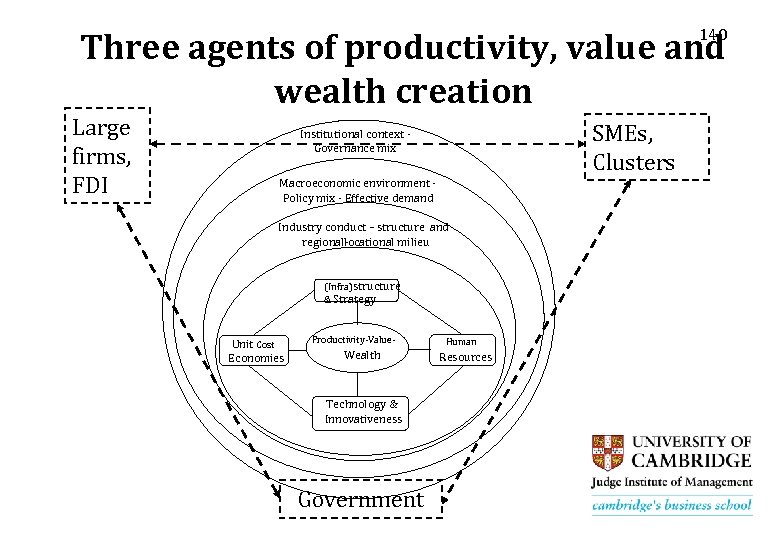

140 Three agents of productivity, value and wealth creation Large firms, FDI SMEs, Clusters Institutional context Governance mix Macroeconomic environment Policy mix - Effective demand Industry conduct – structure and regional-ocational milieu l (Infra)structure & Strategy Unit Cost Economies Productivity-Value- Wealth Technology & Innovativeness Government Human Resources

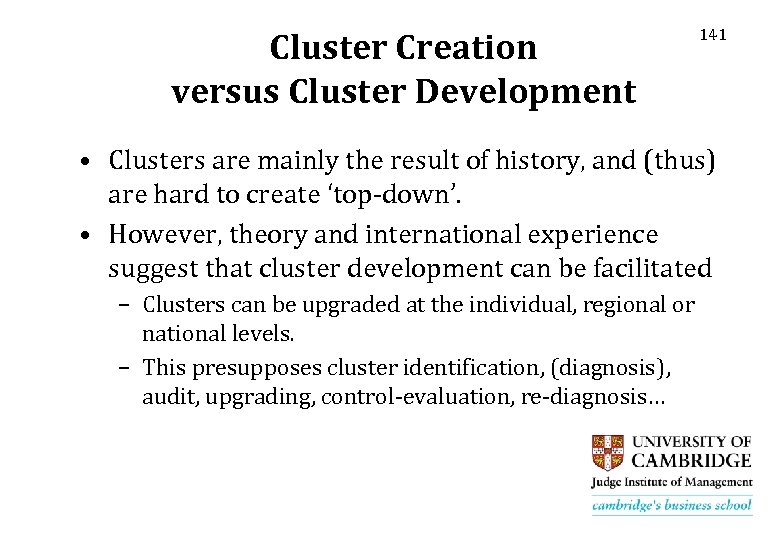

Cluster Creation versus Cluster Development 141 • Clusters are mainly the result of history, and (thus) are hard to create ‘top-down’. • However, theory and international experience suggest that cluster development can be facilitated – Clusters can be upgraded at the individual, regional or national levels. – This presupposes cluster identification, (diagnosis), audit, upgrading, control-evaluation, re-diagnosis…

Strategy for Sustainable Competitiveness 142 • According to the Productivity-Competitiveness model all the following measures can improve productivity and competitiveness – horizontal measures (soft and hard infrastructure) – inter- and intra-firm sectoral restructuring for innovative ‘value for money’ products and services – clusters of SMEs • ‘Regions of Excellence’ (‘mega-clusters’) can encapsulate all three aspects, thus serve as Strategy for Productivity and Competitiveness.

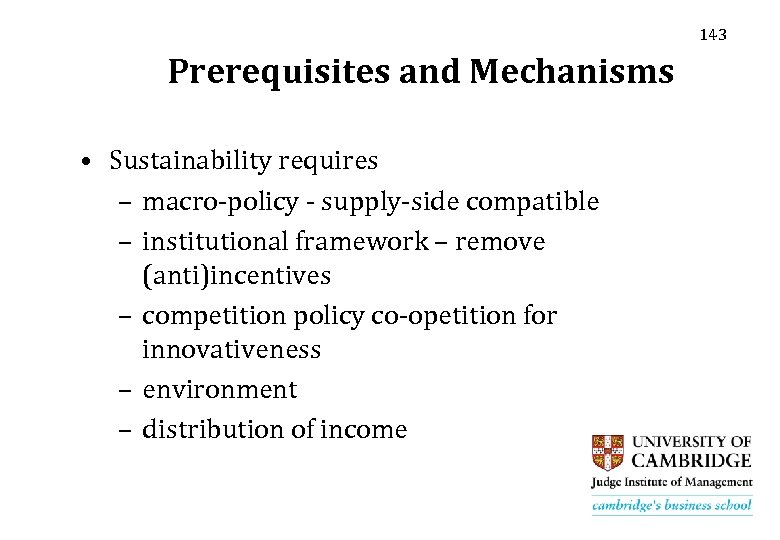

143 Prerequisites and Mechanisms • Sustainability requires – macro-policy - supply-side compatible – institutional framework – remove (anti)incentives – competition policy co-opetition for innovativeness – environment – distribution of income

144 Conclusions • Possible and desirable to identify and develop (mega) clusters, for productivity, competitiveness, regional development, convergence and deepening of democracy. • The state can be a catalyst and facilitator. • Method and tools developed can help in this direction.

International Business Economics Overall Conclusion and the Future of MNCs

146 Conclusions • Value creation, through – firm productivity and competitiveness – government enabling policies, national productivity and competitiveness • Under conditions, MNCs and FDI, SME clusters and government policy can help achieve this objective

147 The Future • The MNC, like ‘competition’ and co-operation itself, is both ‘god and devil’. • MNCs will be a great force of economic growth, yet a threat to diversity, equity and democracy. • Policy and polity should aim at identifying routes that deliver the goods at least cost – this can include painful ‘trade-offs’.

dbce8875d19e42db9902710f3b92e4b1.ppt