f651b50123d723665c623219e01693e1.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 27

Integrating Model Checking and Procedural Languages David Owen July 19, 2004

Integrating Model Checking and Procedural Languages David Owen July 19, 2004

Overview • Background: verification / search tools, criteria for when to use which tool, combining different strategies. • Experiments: flight guidance system, leader election protocol, dining philosophers, resource arbiter. • Implementation: Lurch, our random simulation tool for finite-state models. • Lean: Lurch + machine learning. • Lean experiment: Chemical factory optimization. 2

Overview • Background: verification / search tools, criteria for when to use which tool, combining different strategies. • Experiments: flight guidance system, leader election protocol, dining philosophers, resource arbiter. • Implementation: Lurch, our random simulation tool for finite-state models. • Lean: Lurch + machine learning. • Lean experiment: Chemical factory optimization. 2

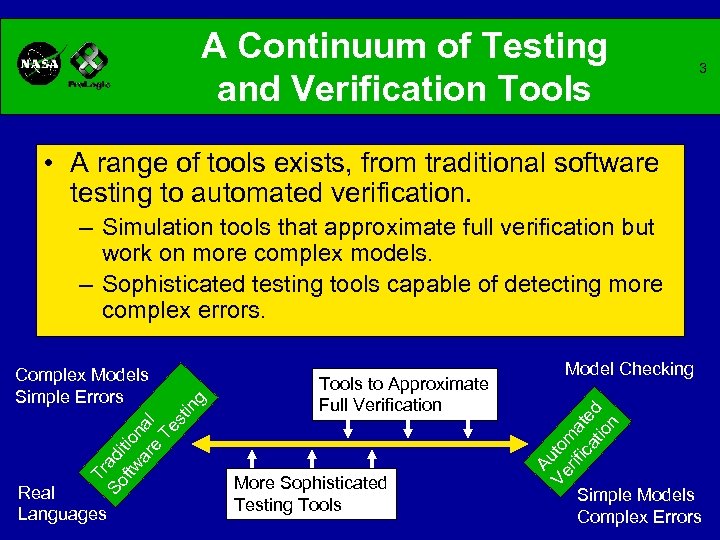

A Continuum of Testing and Verification Tools 3 • A range of tools exists, from traditional software testing to automated verification. Real Languages Tools to Approximate Full Verification More Sophisticated Testing Tools Model Checking Au Ve to rif ma ica te tio d n in Tr So ad ftw itio ar nal e Te st Complex Models Simple Errors g – Simulation tools that approximate full verification but work on more complex models. – Sophisticated testing tools capable of detecting more complex errors. Simple Models Complex Errors

A Continuum of Testing and Verification Tools 3 • A range of tools exists, from traditional software testing to automated verification. Real Languages Tools to Approximate Full Verification More Sophisticated Testing Tools Model Checking Au Ve to rif ma ica te tio d n in Tr So ad ftw itio ar nal e Te st Complex Models Simple Errors g – Simulation tools that approximate full verification but work on more complex models. – Sophisticated testing tools capable of detecting more complex errors. Simple Models Complex Errors

Changing Expectations of a Software Analyst • Cobleigh et. al. idea—three modes of analysis. – Exploratory mode: quick feedback needed to learn how the system works and refine properties. – Fault-finding mode: short and clear error traces needed for debugging. – Maintenance mode: completeness, scalability needed to verify overall system. • Different tools have different strengths. – Simulation tools good for exploratory mode. – Symbolic model checking good for short error traces. – Explicit-state model checking good for speed and scalability. 4

Changing Expectations of a Software Analyst • Cobleigh et. al. idea—three modes of analysis. – Exploratory mode: quick feedback needed to learn how the system works and refine properties. – Fault-finding mode: short and clear error traces needed for debugging. – Maintenance mode: completeness, scalability needed to verify overall system. • Different tools have different strengths. – Simulation tools good for exploratory mode. – Symbolic model checking good for short error traces. – Explicit-state model checking good for speed and scalability. 4

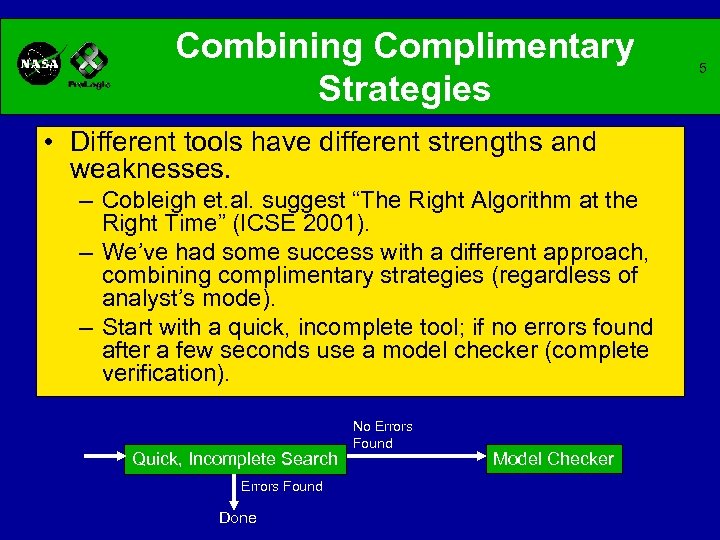

Combining Complimentary Strategies • Different tools have different strengths and weaknesses. – Cobleigh et. al. suggest “The Right Algorithm at the Right Time” (ICSE 2001). – We’ve had some success with a different approach, combining complimentary strategies (regardless of analyst’s mode). – Start with a quick, incomplete tool; if no errors found after a few seconds use a model checker (complete verification). Quick, Incomplete Search Errors Found Done No Errors Found Model Checker 5

Combining Complimentary Strategies • Different tools have different strengths and weaknesses. – Cobleigh et. al. suggest “The Right Algorithm at the Right Time” (ICSE 2001). – We’ve had some success with a different approach, combining complimentary strategies (regardless of analyst’s mode). – Start with a quick, incomplete tool; if no errors found after a few seconds use a model checker (complete verification). Quick, Incomplete Search Errors Found Done No Errors Found Model Checker 5

Random Simulation of Concurrent System Models • Randomized algorithms known to be simple, fast and effective in many domains. • West used random simulation to detect errors in concurrent system models. – This approach was surprisingly successful. – Success was attributed to the fact that most errors detected are much less complex than the overall system. • We have implemented a similar random simulation in a tool called Lurch. – Added early stopping heuristics. – C code can be included in the model. 6

Random Simulation of Concurrent System Models • Randomized algorithms known to be simple, fast and effective in many domains. • West used random simulation to detect errors in concurrent system models. – This approach was surprisingly successful. – Success was attributed to the fact that most errors detected are much less complex than the overall system. • We have implemented a similar random simulation in a tool called Lurch. – Added early stopping heuristics. – C code can be included in the model. 6

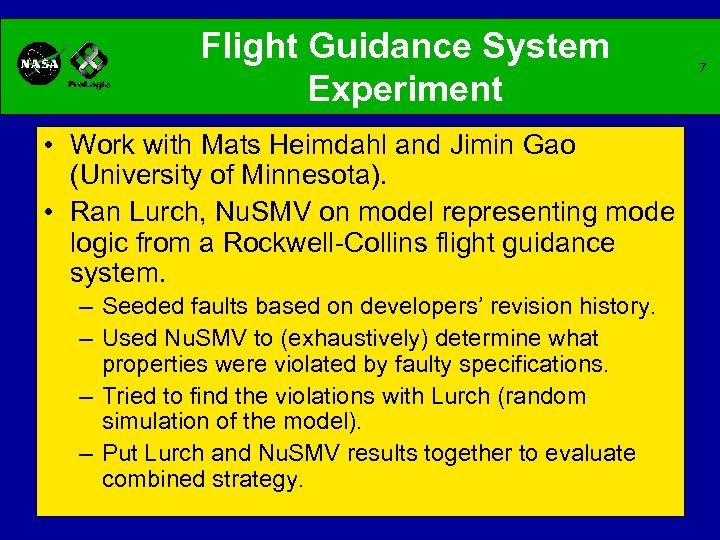

Flight Guidance System Experiment • Work with Mats Heimdahl and Jimin Gao (University of Minnesota). • Ran Lurch, Nu. SMV on model representing mode logic from a Rockwell-Collins flight guidance system. – Seeded faults based on developers’ revision history. – Used Nu. SMV to (exhaustively) determine what properties were violated by faulty specifications. – Tried to find the violations with Lurch (random simulation of the model). – Put Lurch and Nu. SMV results together to evaluate combined strategy. 7

Flight Guidance System Experiment • Work with Mats Heimdahl and Jimin Gao (University of Minnesota). • Ran Lurch, Nu. SMV on model representing mode logic from a Rockwell-Collins flight guidance system. – Seeded faults based on developers’ revision history. – Used Nu. SMV to (exhaustively) determine what properties were violated by faulty specifications. – Tried to find the violations with Lurch (random simulation of the model). – Put Lurch and Nu. SMV results together to evaluate combined strategy. 7

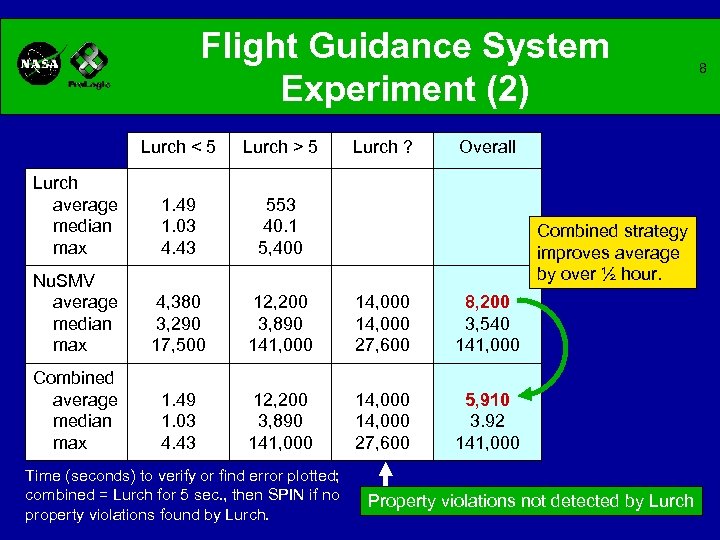

Flight Guidance System Experiment (2) Lurch < 5 Lurch > 5 Lurch average median max 1. 49 1. 03 4. 43 553 40. 1 5, 400 Nu. SMV average median max 4, 380 3, 290 17, 500 12, 200 3, 890 141, 000 14, 000 27, 600 8, 200 3, 540 141, 000 Combined average median max 1. 49 1. 03 4. 43 12, 200 3, 890 141, 000 14, 000 27, 600 5, 910 3. 92 141, 000 Time (seconds) to verify or find error plotted; combined = Lurch for 5 sec. , then SPIN if no property violations found by Lurch ? Overall Combined strategy improves average by over ½ hour. Property violations not detected by Lurch 8

Flight Guidance System Experiment (2) Lurch < 5 Lurch > 5 Lurch average median max 1. 49 1. 03 4. 43 553 40. 1 5, 400 Nu. SMV average median max 4, 380 3, 290 17, 500 12, 200 3, 890 141, 000 14, 000 27, 600 8, 200 3, 540 141, 000 Combined average median max 1. 49 1. 03 4. 43 12, 200 3, 890 141, 000 14, 000 27, 600 5, 910 3. 92 141, 000 Time (seconds) to verify or find error plotted; combined = Lurch for 5 sec. , then SPIN if no property violations found by Lurch ? Overall Combined strategy improves average by over ½ hour. Property violations not detected by Lurch 8

Leader Election Protocol Experiment • Protocol published as an example for SPIN (Holzmann 1997 TSE article). • N processes communicating via message queues interact to choose one leader process. • Checked for liveness property always(eventually(one “leader” chosen)). • Ran Lurch + SPIN combination strategy on original and two fault-seeded versions of the model. – Seeded faults: where a process is sending out a message, the wrong message type was used. – Two different fault-seeded versions created: one that turned out easy, another that turned out harder. 9

Leader Election Protocol Experiment • Protocol published as an example for SPIN (Holzmann 1997 TSE article). • N processes communicating via message queues interact to choose one leader process. • Checked for liveness property always(eventually(one “leader” chosen)). • Ran Lurch + SPIN combination strategy on original and two fault-seeded versions of the model. – Seeded faults: where a process is sending out a message, the wrong message type was used. – Two different fault-seeded versions created: one that turned out easy, another that turned out harder. 9

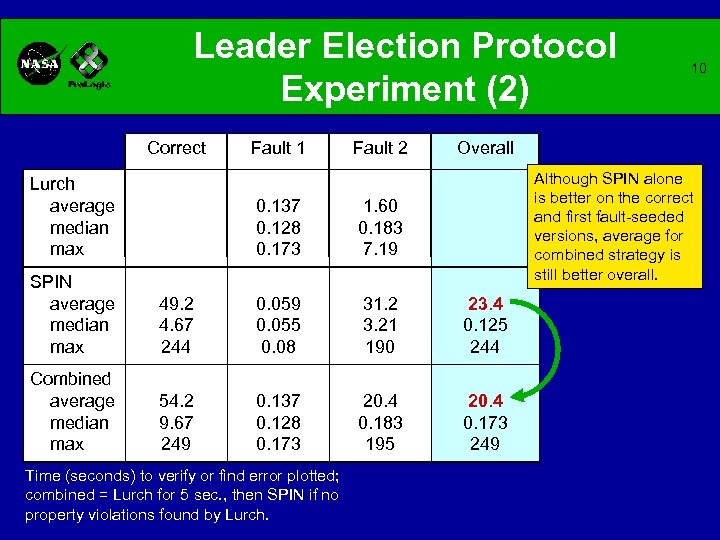

Leader Election Protocol Experiment (2) Correct Lurch average median max Fault 1 Fault 2 0. 137 0. 128 0. 173 Overall Although SPIN alone is better on the correct and first fault-seeded versions, average for combined strategy is still better overall. 1. 60 0. 183 7. 19 SPIN average median max 49. 2 4. 67 244 0. 059 0. 055 0. 08 31. 2 3. 21 190 23. 4 0. 125 244 Combined average median max 54. 2 9. 67 249 0. 137 0. 128 0. 173 20. 4 0. 183 195 20. 4 0. 173 249 Time (seconds) to verify or find error plotted; combined = Lurch for 5 sec. , then SPIN if no property violations found by Lurch. 10

Leader Election Protocol Experiment (2) Correct Lurch average median max Fault 1 Fault 2 0. 137 0. 128 0. 173 Overall Although SPIN alone is better on the correct and first fault-seeded versions, average for combined strategy is still better overall. 1. 60 0. 183 7. 19 SPIN average median max 49. 2 4. 67 244 0. 059 0. 055 0. 08 31. 2 3. 21 190 23. 4 0. 125 244 Combined average median max 54. 2 9. 67 249 0. 137 0. 128 0. 173 20. 4 0. 183 195 20. 4 0. 173 249 Time (seconds) to verify or find error plotted; combined = Lurch for 5 sec. , then SPIN if no property violations found by Lurch. 10

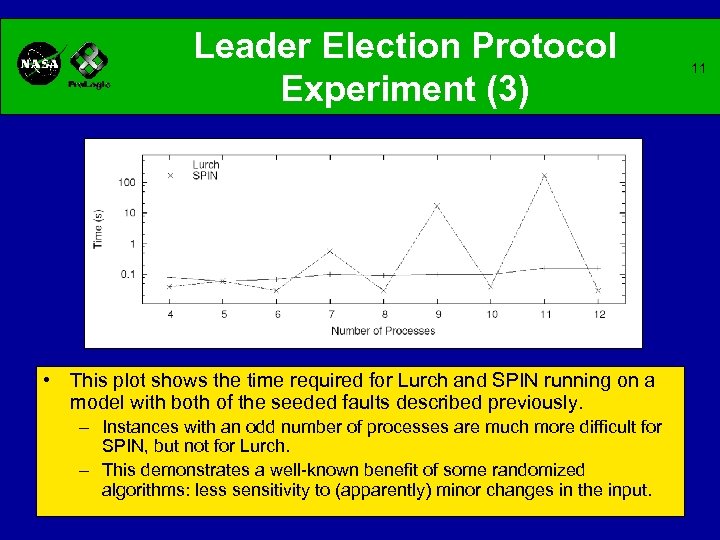

Leader Election Protocol Experiment (3) • This plot shows the time required for Lurch and SPIN running on a model with both of the seeded faults described previously. – Instances with an odd number of processes are much more difficult for SPIN, but not for Lurch. – This demonstrates a well-known benefit of some randomized algorithms: less sensitivity to (apparently) minor changes in the input. 11

Leader Election Protocol Experiment (3) • This plot shows the time required for Lurch and SPIN running on a model with both of the seeded faults described previously. – Instances with an odd number of processes are much more difficult for SPIN, but not for Lurch. – This demonstrates a well-known benefit of some randomized algorithms: less sensitivity to (apparently) minor changes in the input. 11

Dining Philosophers Experiment • Two different versions of the problem: – Normal: n philosophers seated around a table; each repeatedly tries to acquire left and right forks, eat, and then set down the forks. – No loop: same as normal version, except philosophers only try to eat once. • Both versions of the problem contain two deadlocks at depth n. • We ran Lurch, SPIN and Nu. SMV, until the shortest path to a deadlock was found. • The normal version was harder for Nu. SMV and Lurch; the no-loop version was harder for SPIN. 12

Dining Philosophers Experiment • Two different versions of the problem: – Normal: n philosophers seated around a table; each repeatedly tries to acquire left and right forks, eat, and then set down the forks. – No loop: same as normal version, except philosophers only try to eat once. • Both versions of the problem contain two deadlocks at depth n. • We ran Lurch, SPIN and Nu. SMV, until the shortest path to a deadlock was found. • The normal version was harder for Nu. SMV and Lurch; the no-loop version was harder for SPIN. 12

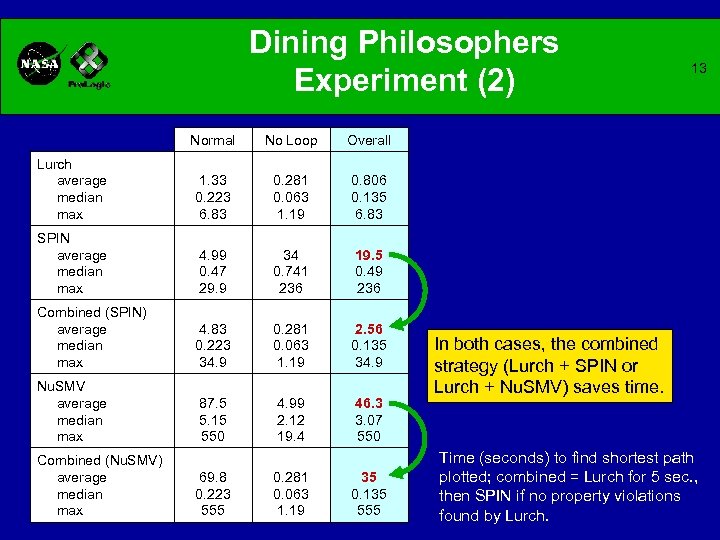

Dining Philosophers Experiment (2) Normal No Loop Overall Lurch average median max 1. 33 0. 223 6. 83 0. 281 0. 063 1. 19 0. 806 0. 135 6. 83 SPIN average median max 4. 99 0. 47 29. 9 34 0. 741 236 19. 5 0. 49 236 Combined (SPIN) average median max 4. 83 0. 223 34. 9 0. 281 0. 063 1. 19 2. 56 0. 135 34. 9 Nu. SMV average median max 87. 5 5. 15 550 4. 99 2. 12 19. 4 46. 3 3. 07 550 13 Combined (Nu. SMV) average median max 69. 8 0. 223 555 0. 281 0. 063 1. 19 35 0. 135 555 In both cases, the combined strategy (Lurch + SPIN or Lurch + Nu. SMV) saves time. Time (seconds) to find shortest path plotted; combined = Lurch for 5 sec. , then SPIN if no property violations found by Lurch.

Dining Philosophers Experiment (2) Normal No Loop Overall Lurch average median max 1. 33 0. 223 6. 83 0. 281 0. 063 1. 19 0. 806 0. 135 6. 83 SPIN average median max 4. 99 0. 47 29. 9 34 0. 741 236 19. 5 0. 49 236 Combined (SPIN) average median max 4. 83 0. 223 34. 9 0. 281 0. 063 1. 19 2. 56 0. 135 34. 9 Nu. SMV average median max 87. 5 5. 15 550 4. 99 2. 12 19. 4 46. 3 3. 07 550 13 Combined (Nu. SMV) average median max 69. 8 0. 223 555 0. 281 0. 063 1. 19 35 0. 135 555 In both cases, the combined strategy (Lurch + SPIN or Lurch + Nu. SMV) saves time. Time (seconds) to find shortest path plotted; combined = Lurch for 5 sec. , then SPIN if no property violations found by Lurch.

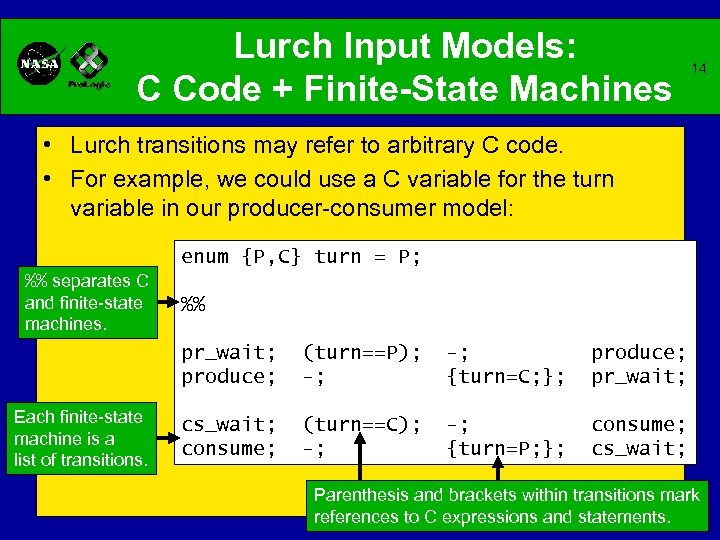

Lurch Input Models: C Code + Finite-State Machines 14 • Lurch transitions may refer to arbitrary C code. • For example, we could use a C variable for the turn variable in our producer-consumer model: enum {P, C} turn = P; %% separates C and finite-state machines. %% pr_wait; produce; Each finite-state machine is a list of transitions. (turn==P); -; {turn=C; }; produce; pr_wait; cs_wait; consume; (turn==C); -; {turn=P; }; consume; cs_wait; Parenthesis and brackets within transitions mark references to C expressions and statements.

Lurch Input Models: C Code + Finite-State Machines 14 • Lurch transitions may refer to arbitrary C code. • For example, we could use a C variable for the turn variable in our producer-consumer model: enum {P, C} turn = P; %% separates C and finite-state machines. %% pr_wait; produce; Each finite-state machine is a list of transitions. (turn==P); -; {turn=C; }; produce; pr_wait; cs_wait; consume; (turn==C); -; {turn=P; }; consume; cs_wait; Parenthesis and brackets within transitions mark references to C expressions and statements.

RA-RRE Model • Work with John Powell (NASA JPL). • Resource arbitration (RA) system on board a robotic remote exploration (RRE) vehicle – User processes make requests for RRE resources through a message queue. – User processes run concurrently with an arbiter process, which responds to requests in the queue. – Arbiter will Grant, Deny, Pend, Rescind or Deny and Rescind a resource request. – Abiter filters out nonsense messages and ignores them. 15

RA-RRE Model • Work with John Powell (NASA JPL). • Resource arbitration (RA) system on board a robotic remote exploration (RRE) vehicle – User processes make requests for RRE resources through a message queue. – User processes run concurrently with an arbiter process, which responds to requests in the queue. – Arbiter will Grant, Deny, Pend, Rescind or Deny and Rescind a resource request. – Abiter filters out nonsense messages and ignores them. 15

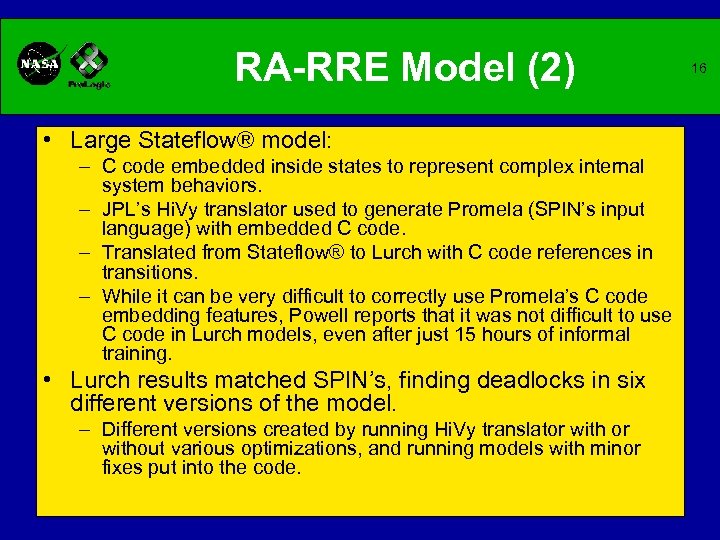

RA-RRE Model (2) • Large Stateflow® model: – C code embedded inside states to represent complex internal system behaviors. – JPL’s Hi. Vy translator used to generate Promela (SPIN’s input language) with embedded C code. – Translated from Stateflow® to Lurch with C code references in transitions. – While it can be very difficult to correctly use Promela’s C code embedding features, Powell reports that it was not difficult to use C code in Lurch models, even after just 15 hours of informal training. • Lurch results matched SPIN’s, finding deadlocks in six different versions of the model. – Different versions created by running Hi. Vy translator without various optimizations, and running models with minor fixes put into the code. 16

RA-RRE Model (2) • Large Stateflow® model: – C code embedded inside states to represent complex internal system behaviors. – JPL’s Hi. Vy translator used to generate Promela (SPIN’s input language) with embedded C code. – Translated from Stateflow® to Lurch with C code references in transitions. – While it can be very difficult to correctly use Promela’s C code embedding features, Powell reports that it was not difficult to use C code in Lurch models, even after just 15 hours of informal training. • Lurch results matched SPIN’s, finding deadlocks in six different versions of the model. – Different versions created by running Hi. Vy translator without various optimizations, and running models with minor fixes put into the code. 16

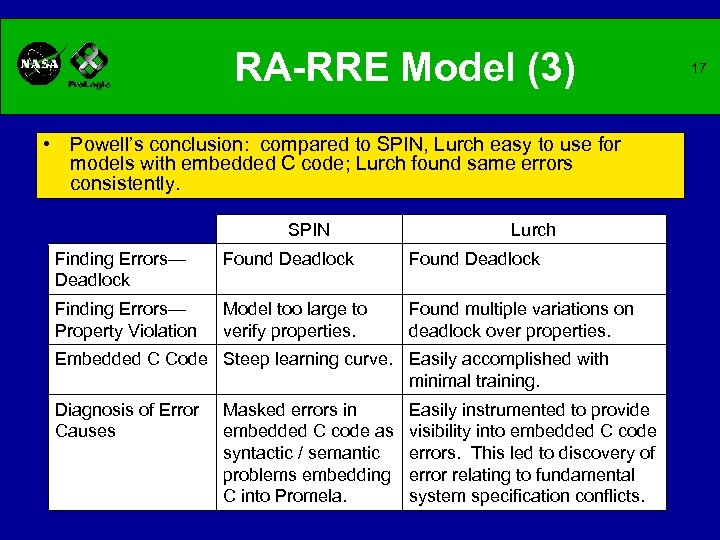

RA-RRE Model (3) • Powell’s conclusion: compared to SPIN, Lurch easy to use for models with embedded C code; Lurch found same errors consistently. SPIN Lurch Finding Errors— Deadlock Found Deadlock Finding Errors— Property Violation Model too large to verify properties. Found multiple variations on deadlock over properties. Embedded C Code Steep learning curve. Easily accomplished with minimal training. Diagnosis of Error Causes Masked errors in embedded C code as syntactic / semantic problems embedding C into Promela. Easily instrumented to provide visibility into embedded C code errors. This led to discovery of error relating to fundamental system specification conflicts. 17

RA-RRE Model (3) • Powell’s conclusion: compared to SPIN, Lurch easy to use for models with embedded C code; Lurch found same errors consistently. SPIN Lurch Finding Errors— Deadlock Found Deadlock Finding Errors— Property Violation Model too large to verify properties. Found multiple variations on deadlock over properties. Embedded C Code Steep learning curve. Easily accomplished with minimal training. Diagnosis of Error Causes Masked errors in embedded C code as syntactic / semantic problems embedding C into Promela. Easily instrumented to provide visibility into embedded C code errors. This led to discovery of error relating to fundamental system specification conflicts. 17

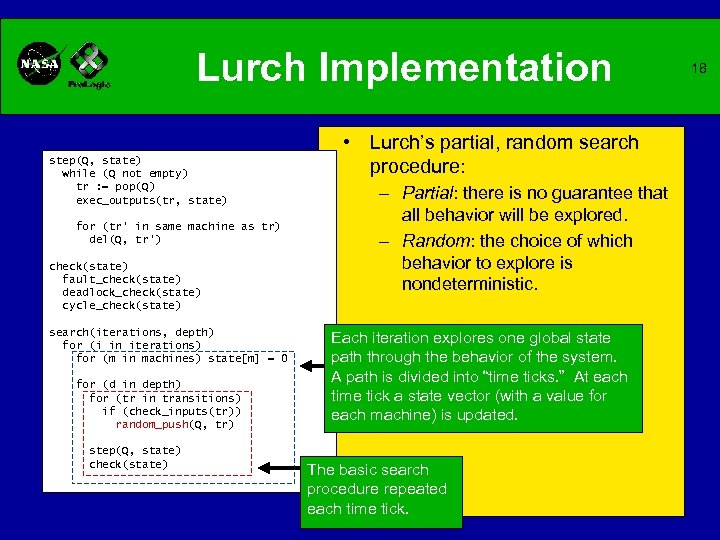

Lurch Implementation step(Q, state) while (Q not empty) tr : = pop(Q) exec_outputs(tr, state) for (tr' in same machine as tr) del(Q, tr') check(state) fault_check(state) deadlock_check(state) cycle_check(state) search(iterations, depth) for (i in iterations) for (m in machines) state[m] = 0 for (d in depth) for (tr in transitions) if (check_inputs(tr)) random_push(Q, tr) step(Q, state) check(state) • Lurch’s partial, random search procedure: – Partial: there is no guarantee that all behavior will be explored. – Random: the choice of which behavior to explore is nondeterministic. Each iteration explores one global state path through the behavior of the system. A path is divided into “time ticks. ” At each time tick a state vector (with a value for each machine) is updated. The basic search procedure repeated each time tick. 18

Lurch Implementation step(Q, state) while (Q not empty) tr : = pop(Q) exec_outputs(tr, state) for (tr' in same machine as tr) del(Q, tr') check(state) fault_check(state) deadlock_check(state) cycle_check(state) search(iterations, depth) for (i in iterations) for (m in machines) state[m] = 0 for (d in depth) for (tr in transitions) if (check_inputs(tr)) random_push(Q, tr) step(Q, state) check(state) • Lurch’s partial, random search procedure: – Partial: there is no guarantee that all behavior will be explored. – Random: the choice of which behavior to explore is nondeterministic. Each iteration explores one global state path through the behavior of the system. A path is divided into “time ticks. ” At each time tick a state vector (with a value for each machine) is updated. The basic search procedure repeated each time tick. 18

Lurch Implementation (2) • The step function is called at each time tick along a global state path. • Input is a queue of transitions whose inputs are satisfied, along with the state vector. • Transitions are popped from the queue, and their outputs are executed. • The effect of transitions executed is stored in the state vector. • Only one transition from each machine can be executed at each time step; others are discarded from the queue. 19

Lurch Implementation (2) • The step function is called at each time tick along a global state path. • Input is a queue of transitions whose inputs are satisfied, along with the state vector. • Transitions are popped from the queue, and their outputs are executed. • The effect of transitions executed is stored in the state vector. • Only one transition from each machine can be executed at each time step; others are discarded from the queue. 19

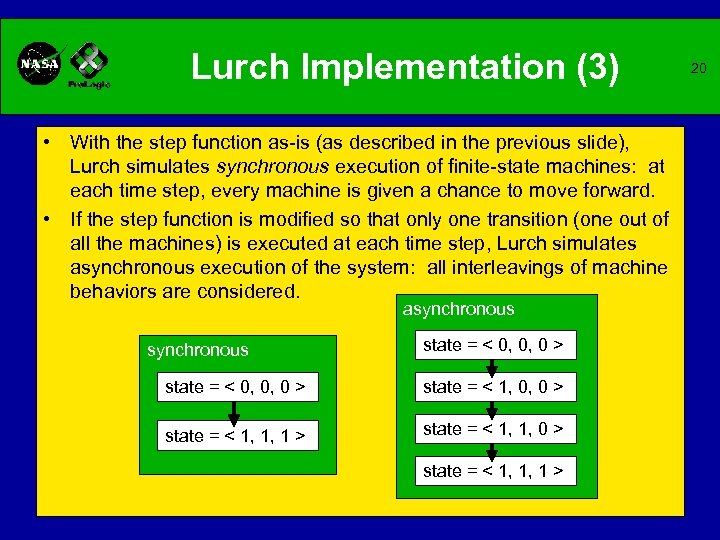

Lurch Implementation (3) • With the step function as-is (as described in the previous slide), Lurch simulates synchronous execution of finite-state machines: at each time step, every machine is given a chance to move forward. • If the step function is modified so that only one transition (one out of all the machines) is executed at each time step, Lurch simulates asynchronous execution of the system: all interleavings of machine behaviors are considered. asynchronous state = < 0, 0, 0 > state = < 1, 1, 1 > state = < 1, 1, 0 > state = < 1, 1, 1 > 20

Lurch Implementation (3) • With the step function as-is (as described in the previous slide), Lurch simulates synchronous execution of finite-state machines: at each time step, every machine is given a chance to move forward. • If the step function is modified so that only one transition (one out of all the machines) is executed at each time step, Lurch simulates asynchronous execution of the system: all interleavings of machine behaviors are considered. asynchronous state = < 0, 0, 0 > state = < 1, 1, 1 > state = < 1, 1, 0 > state = < 1, 1, 1 > 20

Lurch Implementation (4) • At each time tick along a path Lurch checks for local-state faults, deadlocks and cycles. • Local state faults can be found directly from the state vector—if one of the machines is in a state corresponding to a fault, Lurch reports that the fault was reached. • A deadlock occurs when Lurch reaches the end of a global state path (a state for which no new transition’s inputs are satisfied) but not all machines are in a state identified as a legal end state. • Deadlocks are found by looping through the state vector to make sure all local states are legal end states (this is done only when Lurch is at the end of a global state path). 21

Lurch Implementation (4) • At each time tick along a path Lurch checks for local-state faults, deadlocks and cycles. • Local state faults can be found directly from the state vector—if one of the machines is in a state corresponding to a fault, Lurch reports that the fault was reached. • A deadlock occurs when Lurch reaches the end of a global state path (a state for which no new transition’s inputs are satisfied) but not all machines are in a state identified as a legal end state. • Deadlocks are found by looping through the state vector to make sure all local states are legal end states (this is done only when Lurch is at the end of a global state path). 21

Other Applications for Lurch’s Random Simulation • Game playing experiments: n-queens, tic-tac-toe • Lurch is really a fast generator of consistent temporal sequences—so what else can we use it for? • If we generate a score for each temporal sequence, we can use a machine learner to suggest what makes some sequences better than others. • Lurch + Machine Learning = “Lean, ” a randomized heuristic search tool for finite-state models (with optional C code). 22

Other Applications for Lurch’s Random Simulation • Game playing experiments: n-queens, tic-tac-toe • Lurch is really a fast generator of consistent temporal sequences—so what else can we use it for? • If we generate a score for each temporal sequence, we can use a machine learner to suggest what makes some sequences better than others. • Lurch + Machine Learning = “Lean, ” a randomized heuristic search tool for finite-state models (with optional C code). 22

Lean: Combining “Test” and “Task” • Traditional view: specialized devices for different tasks. – Diagnosis, configuration, testing. . . • Alternative: one environment where “test” and “task” are implemented together: – Write down what is known about a domain. – Add an oracle to score a single run (i. e. , score the temporal sequences generated by Lurch). – Instead of different devices for “test” and “task” – “Lean” = Lurch + learn • Run Lurch on sample space of options. • Learn—apply machine learning to find “nudges, ” which are suggestions for which transitions lead to runs with higher scores. • Apply “nudges” in the form of transition probabilities, and run Lurch again, expecting better scores. 23

Lean: Combining “Test” and “Task” • Traditional view: specialized devices for different tasks. – Diagnosis, configuration, testing. . . • Alternative: one environment where “test” and “task” are implemented together: – Write down what is known about a domain. – Add an oracle to score a single run (i. e. , score the temporal sequences generated by Lurch). – Instead of different devices for “test” and “task” – “Lean” = Lurch + learn • Run Lurch on sample space of options. • Learn—apply machine learning to find “nudges, ” which are suggestions for which transitions lead to runs with higher scores. • Apply “nudges” in the form of transition probabilities, and run Lurch again, expecting better scores. 23

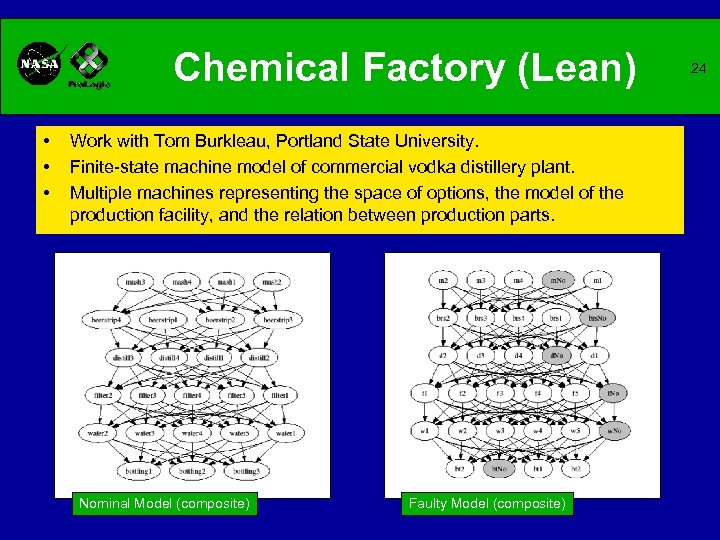

Chemical Factory (Lean) • • • Work with Tom Burkleau, Portland State University. Finite-state machine model of commercial vodka distillery plant. Multiple machines representing the space of options, the model of the production facility, and the relation between production parts. Nominal Model (composite) Faulty Model (composite) 24

Chemical Factory (Lean) • • • Work with Tom Burkleau, Portland State University. Finite-state machine model of commercial vodka distillery plant. Multiple machines representing the space of options, the model of the production facility, and the relation between production parts. Nominal Model (composite) Faulty Model (composite) 24

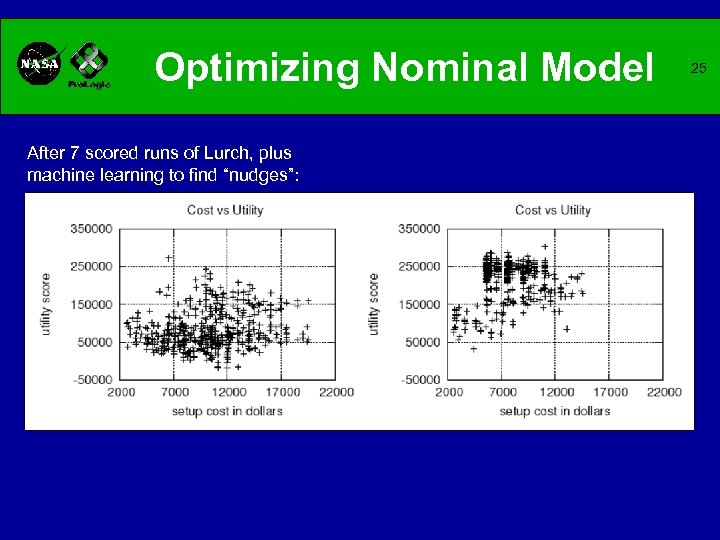

Optimizing Nominal Model After 7 scored runs of Lurch, plus machine learning to find “nudges”: 25

Optimizing Nominal Model After 7 scored runs of Lurch, plus machine learning to find “nudges”: 25

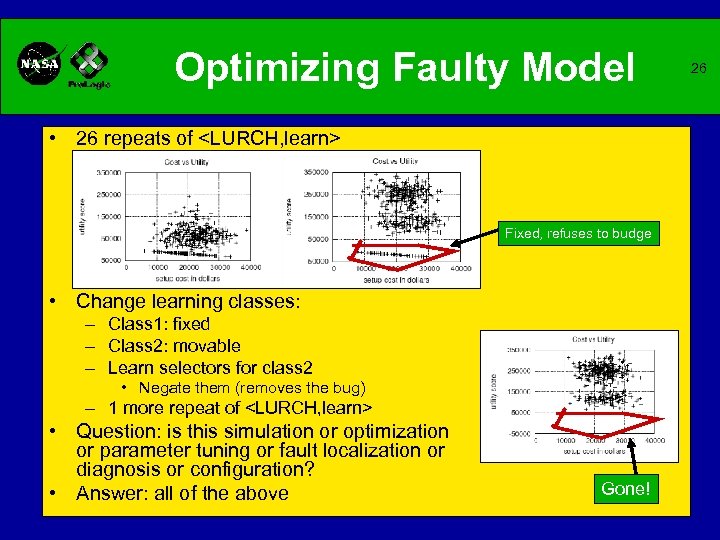

Optimizing Faulty Model • 26 repeats of

Optimizing Faulty Model • 26 repeats of

Conclusion • Combination and model checking of random simulation (Lurch) (SPIN or Nu. SMV) can be faster and more efficient than model checking alone, without sacrificing completeness. – FGS (Heimdahl, Gao at UMN), leader election protocol, dining philosophers experiments. • Lurch allows (easy-to-use) references to arbitrary C code. – RA-RRE model experiments (Powell at JPL). • Lurch uses a simple random search procedure, plus early stopping heuristics and modifications for asynchronous models, hierarchical models, etc. • Lean = Lurch + machine learning. – Chemical factory optimization experiment (Burkleau at PSU). 27

Conclusion • Combination and model checking of random simulation (Lurch) (SPIN or Nu. SMV) can be faster and more efficient than model checking alone, without sacrificing completeness. – FGS (Heimdahl, Gao at UMN), leader election protocol, dining philosophers experiments. • Lurch allows (easy-to-use) references to arbitrary C code. – RA-RRE model experiments (Powell at JPL). • Lurch uses a simple random search procedure, plus early stopping heuristics and modifications for asynchronous models, hierarchical models, etc. • Lean = Lurch + machine learning. – Chemical factory optimization experiment (Burkleau at PSU). 27