2f1c11ec33e7c44bf6df0bc9f0a764f1.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 97

Integrating Genetic and Biomarker Data with Social Science Research: Genetics Jason Fletcher Assistant Professor Health Policy and Administration Yale University RWJ Health and Society Scholar Columbia University

Goals n Introduce some terminology n n Requires multiple exposures Focus n Limitations n n What findings from genetics should you believe? Opportunities How might social scientists use genetic data? n Advances in both genetics and social science n

Data Opportunities n Currently Available—DNA data n Add Health n n Fragile Families n n National longitudinal sample, 5 K, Mothers and children, lower income/immigrant samples Wisconsin Longitudinal Study n n National longitudinal sample, 15 K, Age 12 -30, siblings, school friends, focus on health 1957 HS grads and sibs, long follow up Framingham Heart Study n Medical focus, multigenerational study n Many international datasets

Eventually available(? ) n Health and Retirement Study n n Panel study of income dynamics n n National longitudinal study, ages 50+, spouses, health and aging National longitudinal study, multigenerational families/all ages, income and labor market, health National Longitudinal Survey of Youth n National longitudinal study, labor market focus, multigenerational, siblings

Outline n Background Behavioral genetics (non-molecular) n Molecular genetics n n Integration with Social Science Gene X Environment interactions n Instrumental variables n

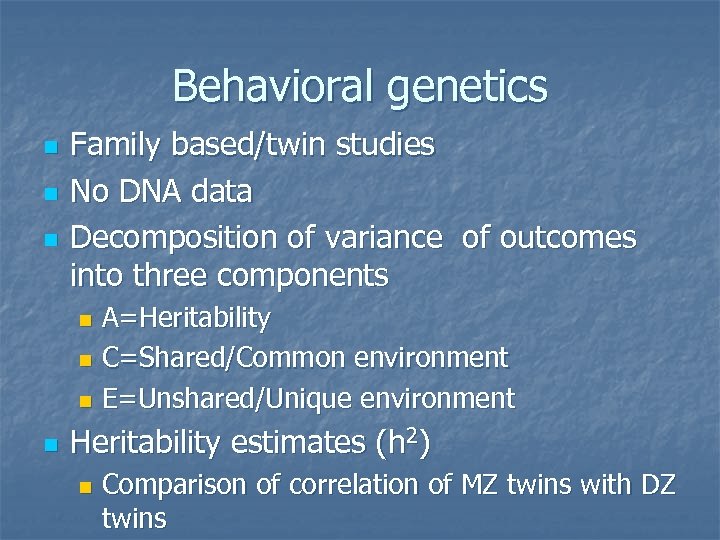

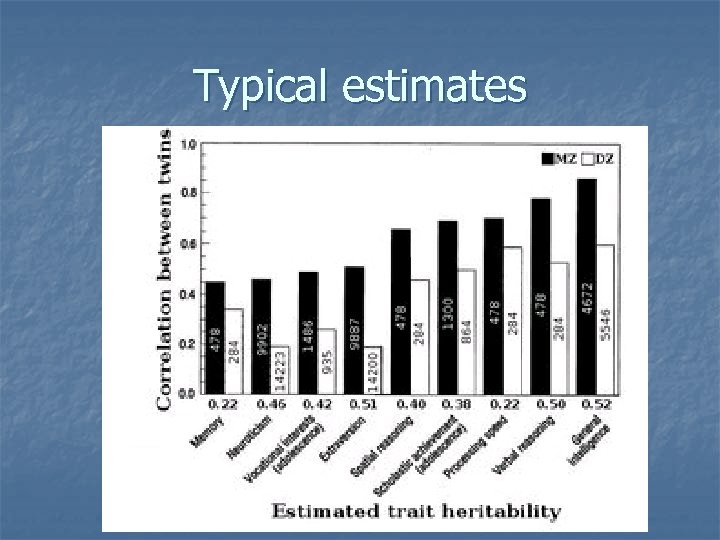

Behavioral genetics n n n Family based/twin studies No DNA data Decomposition of variance of outcomes into three components A=Heritability n C=Shared/Common environment n E=Unshared/Unique environment n n Heritability estimates (h 2) n Comparison of correlation of MZ twins with DZ twins

The basic BG model n Variation in phenotype (outcome/observable characteristic) is a function of variation in additive genetic (genotype) and environmental contributions (shared and unshared)

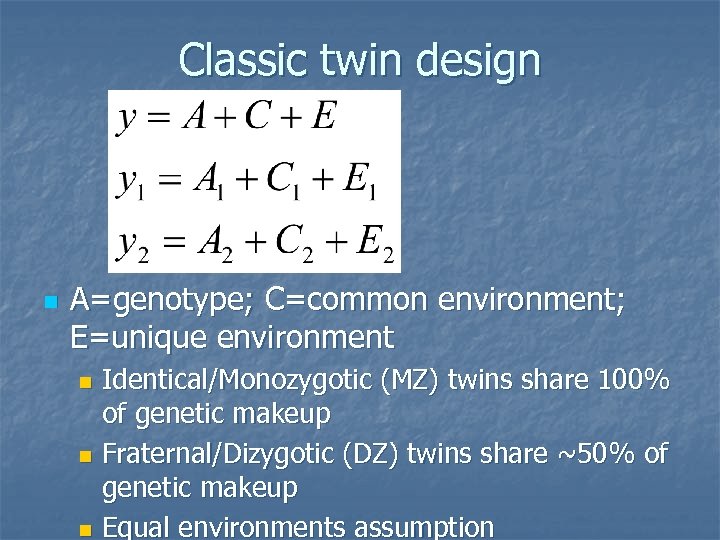

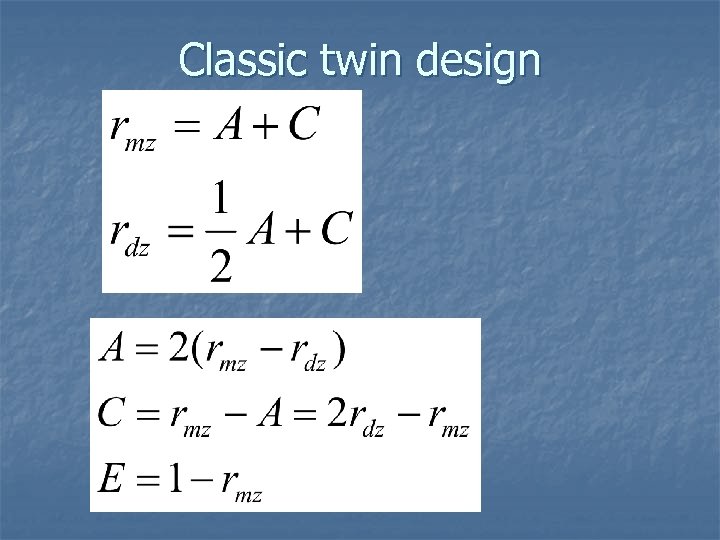

Classic twin design n A=genotype; C=common environment; E=unique environment Identical/Monozygotic (MZ) twins share 100% of genetic makeup n Fraternal/Dizygotic (DZ) twins share ~50% of genetic makeup n Equal environments assumption n

Classic twin design

Typical estimates

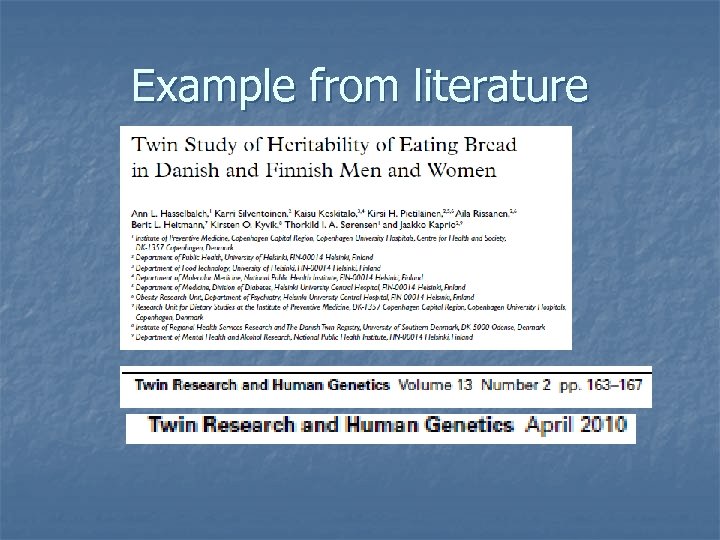

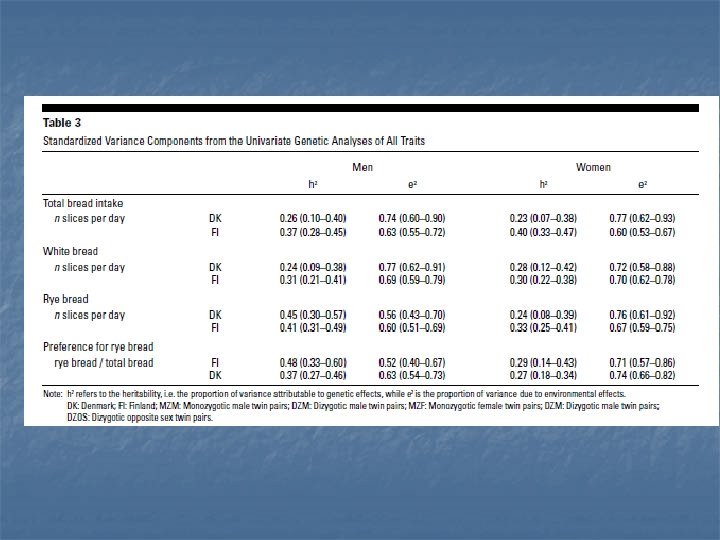

Example from literature

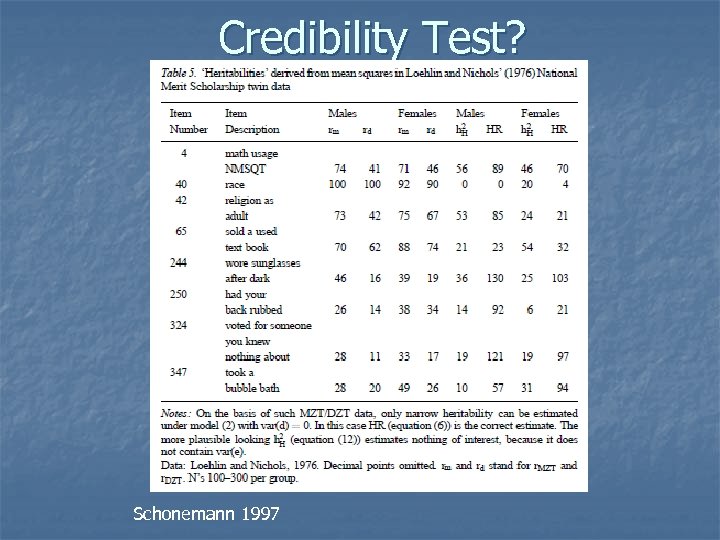

Credibility Test? Schonemann 1997

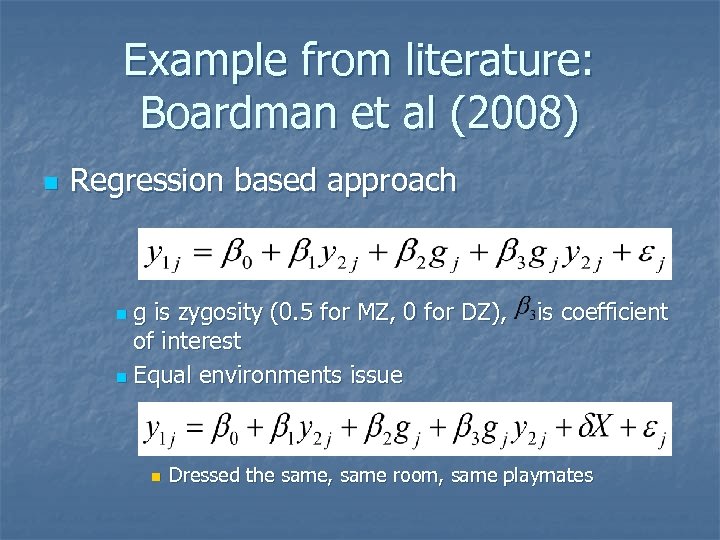

Example from literature: Boardman et al (2008) n Regression based approach g is zygosity (0. 5 for MZ, 0 for DZ), of interest n Equal environments issue n n is coefficient Dressed the same, same room, same playmates

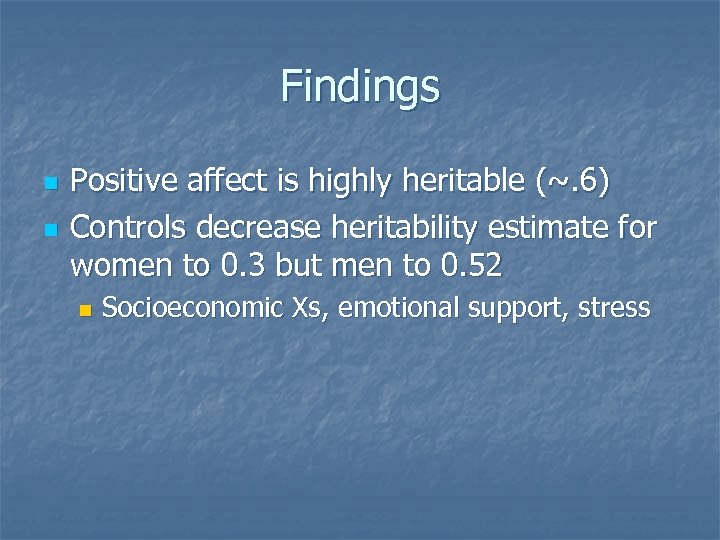

Findings n n Positive affect is highly heritable (~. 6) Controls decrease heritability estimate for women to 0. 3 but men to 0. 52 n Socioeconomic Xs, emotional support, stress

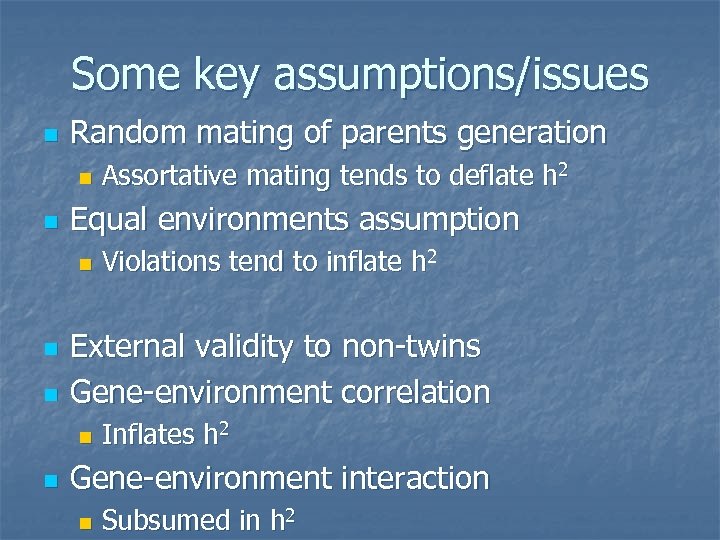

Some key assumptions/issues n Random mating of parents generation n n Equal environments assumption n Violations tend to inflate h 2 External validity to non-twins Gene-environment correlation n n Assortative mating tends to deflate h 2 Inflates h 2 Gene-environment interaction n Subsumed in h 2

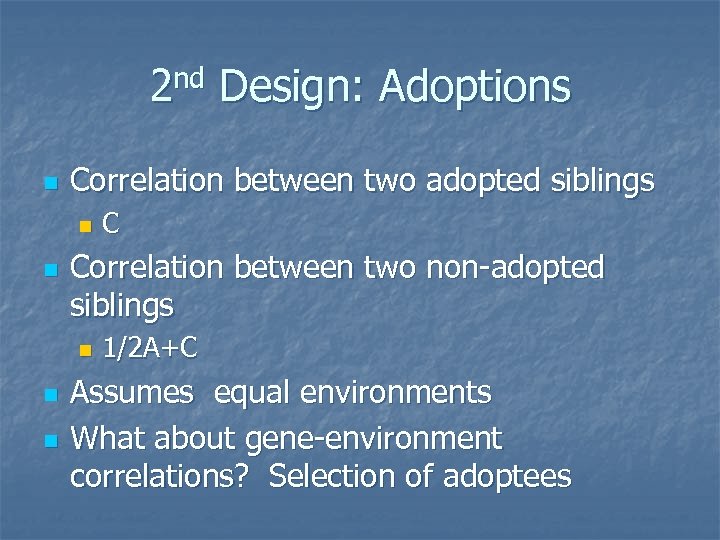

2 nd Design: Adoptions n Correlation between two adopted siblings n n Correlation between two non-adopted siblings n n n C 1/2 A+C Assumes equal environments What about gene-environment correlations? Selection of adoptees

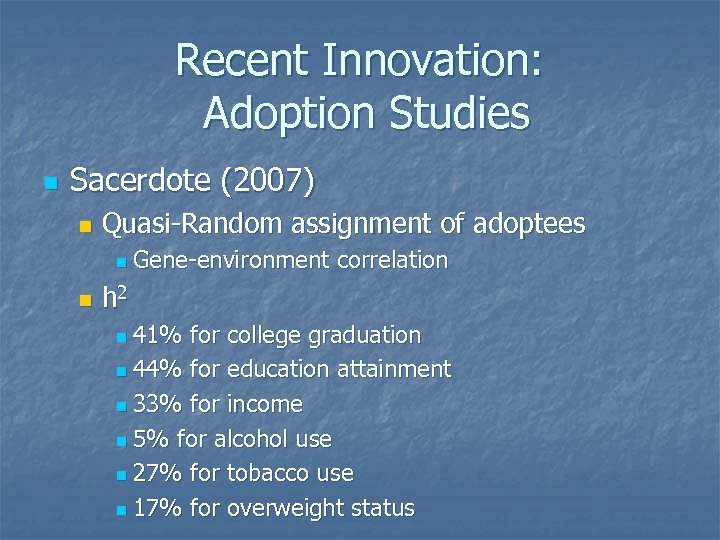

Recent Innovation: Adoption Studies n Sacerdote (2007) n Quasi-Random assignment of adoptees n n Gene-environment correlation h 2 41% for college graduation n 44% for education attainment n 33% for income n 5% for alcohol use n 27% for tobacco use n 17% for overweight status n

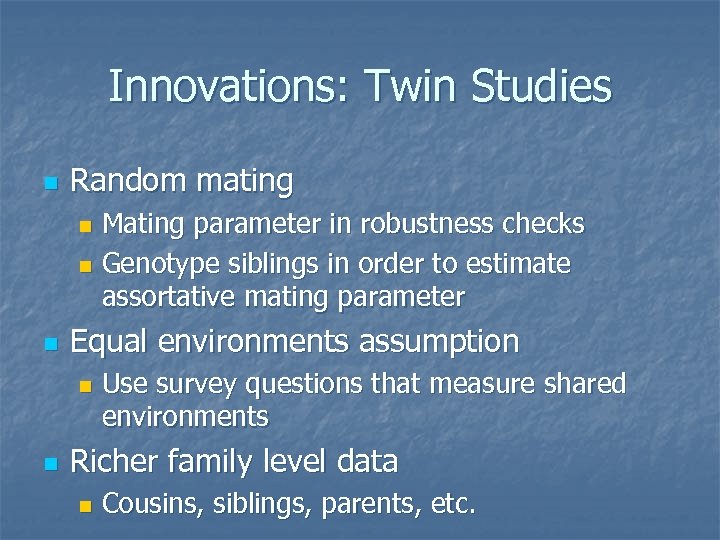

Innovations: Twin Studies n Random mating Mating parameter in robustness checks n Genotype siblings in order to estimate assortative mating parameter n n Equal environments assumption n n Use survey questions that measure shared environments Richer family level data n Cousins, siblings, parents, etc.

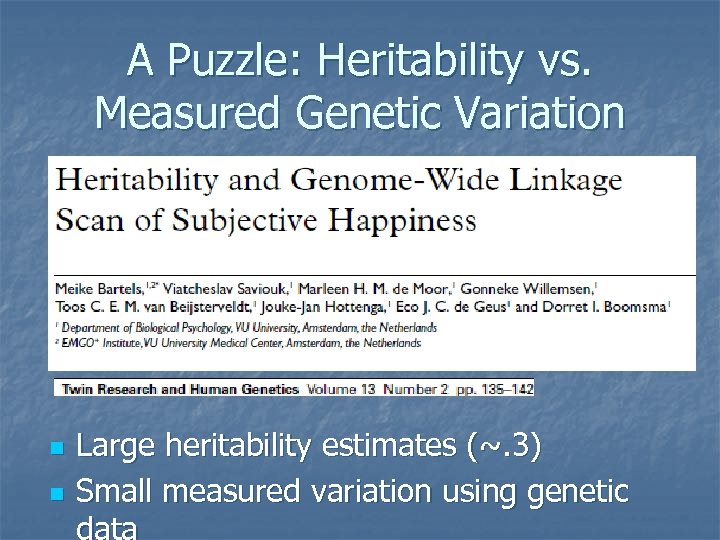

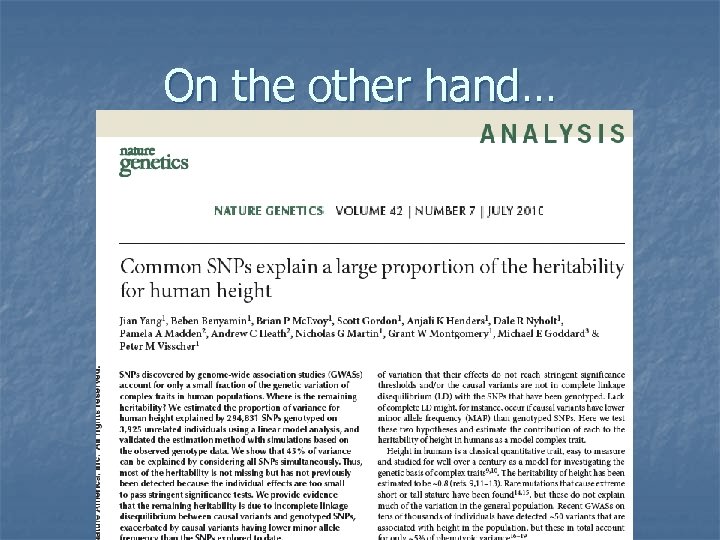

A Puzzle: Heritability vs. Measured Genetic Variation n n Large heritability estimates (~. 3) Small measured variation using genetic

On the other hand…

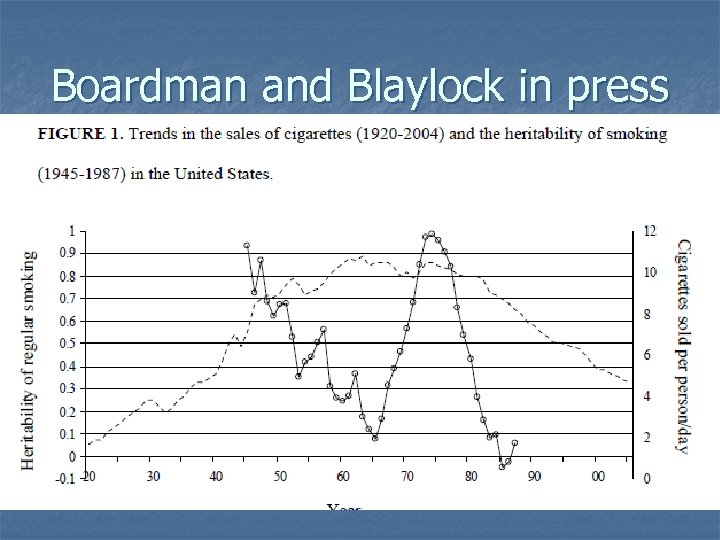

Additional new directions n Variation of h 2 by study population n n Gender, Race, Country, Time Period Can this tell us anything about gene x environment interactions?

Boardman and Blaylock in press

Quiz from Collegeboard. com n If a person has a disorder with h 2=1, then the person will suffer from the disorder n n The heritability of having fingers on each hand is 1 or close to 1 n n False, it is close to zero because the source is often environmental Heritability and inherited are nearly the opposite in meaning n n False, phenylketonuria (PKU) = 1 but mental retardation can be prevented through diet True; equalizing school environments will increase heritability of achievement The heritability of behaviors of identical twins is 1 n n False, it is zero http: //apcentral. collegeboard. com/apc/members/homepage/45829. ht ml

Discussion/Questions n n What do we learn from h 2 estimates? What are the policy implications of estimates? n n Heritability estimates set no upper limit on the potential effect of reducing or eliminating variation in environmental factors that currently vary in response to genotype, as many do. Nor do they set an upper limit on the effect of creating new environments. Heritability estimates do set an upper limit on the effect of reducing or eliminating environmental variations that are independent of genotype, but other statistics usually provide even better estimates of these effects. There is no evidence that genetically based inequalities are harder to eliminate than other inequalities. Until we know how genes affect specific forms of behavior, heritability estimates will tell us almost nothing of importance (Jenks).

Molecular Genetics n n Describe a few concepts How do scientists/biologists/geneticists use genetic data? Sources: http: //www. psych. umn. edu/courses/fall 09 /mcguem/psy 5137/lectures. htm

Properties of Genetic Material n n Specify a code for protein synthesis (i. e. , code for an the sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain. ) Duplicate or replicate during both mitosis and meiosis

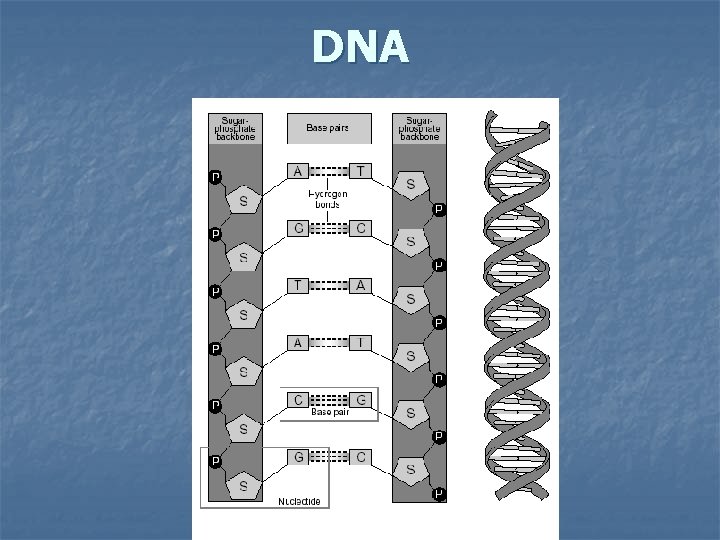

Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) n n Double stranded Strands are held together by (hydrogen) bonds that form between the nucleotide bases of the DNA molecule Adenine (A) <====> Thymine (T) Guanine (G) <====> Cytosine (C)

DNA

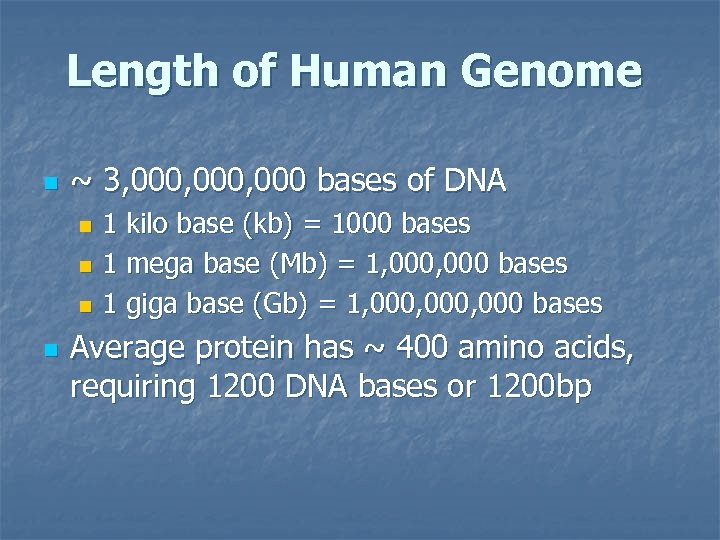

Length of Human Genome n ~ 3, 000, 000 bases of DNA 1 kilo base (kb) = 1000 bases n 1 mega base (Mb) = 1, 000 bases n 1 giga base (Gb) = 1, 000, 000 bases n n Average protein has ~ 400 amino acids, requiring 1200 DNA bases or 1200 bp

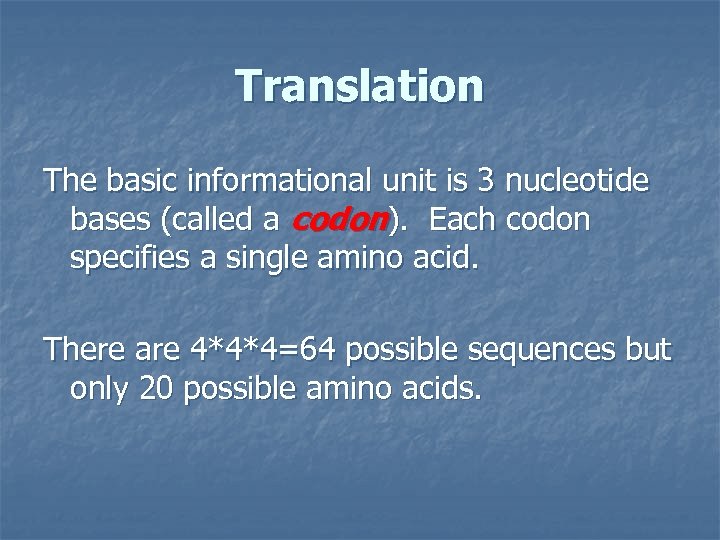

Translation The basic informational unit is 3 nucleotide bases (called a codon). Each codon specifies a single amino acid. There are 4*4*4=64 possible sequences but only 20 possible amino acids.

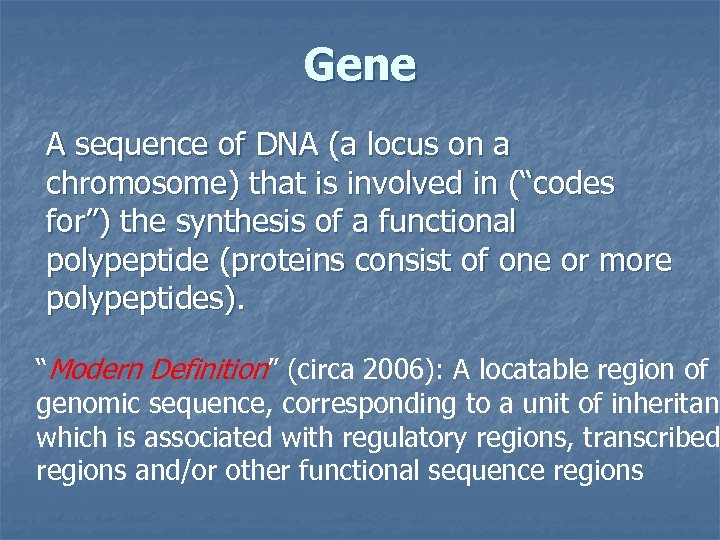

Gene A sequence of DNA (a locus on a chromosome) that is involved in (“codes for”) the synthesis of a functional polypeptide (proteins consist of one or more polypeptides). “Modern Definition” (circa 2006): A locatable region of genomic sequence, corresponding to a unit of inheritanc which is associated with regulatory regions, transcribed regions and/or other functional sequence regions

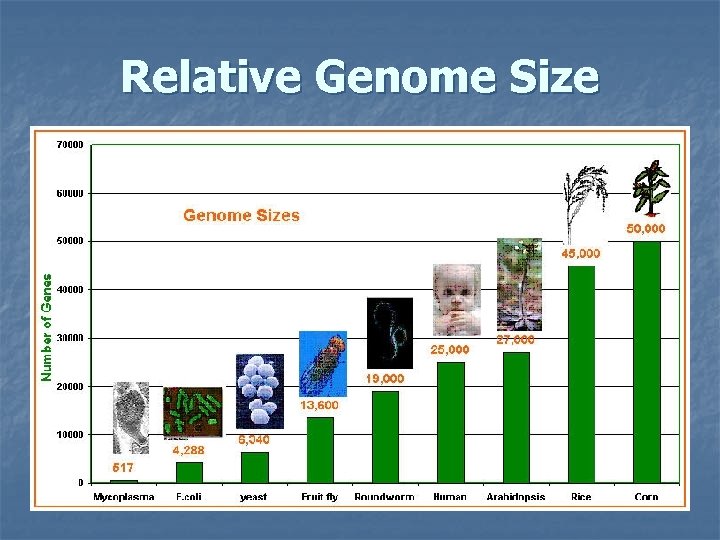

Relative Genome Size

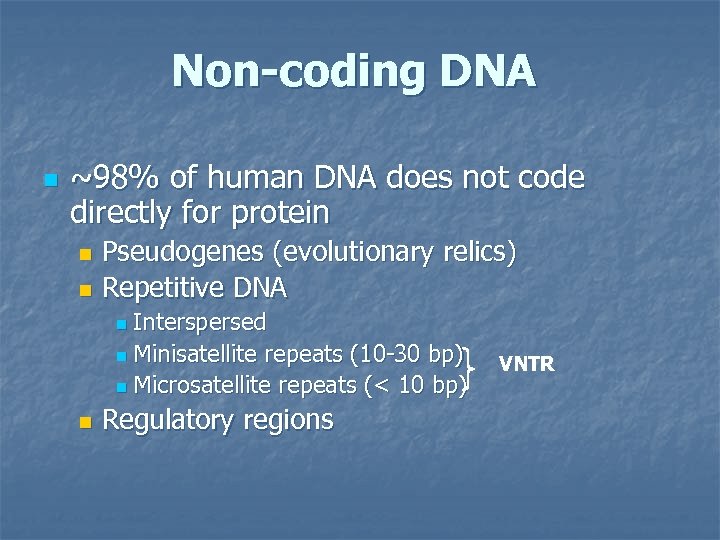

Non-coding DNA n ~98% of human DNA does not code directly for protein Pseudogenes (evolutionary relics) n Repetitive DNA n Interspersed n Minisatellite repeats (10 -30 bp) n Microsatellite repeats (< 10 bp) n n Regulatory regions VNTR

Gene Structure n Typical gene is composed of multiple exons – Expressed sequences of DNA that are translated into protein n introns - Intervening DNA sequences that are not translated n

Genetic Variation Genetic variation between individuals refers to differences in the DNA sequence 1. Originally arose through (gametic) mutation. 2. An estimated 99. 8% - 99. 9% of our DNA is common 3. But then. 1% of 3, 000, 000 = 3 million differences

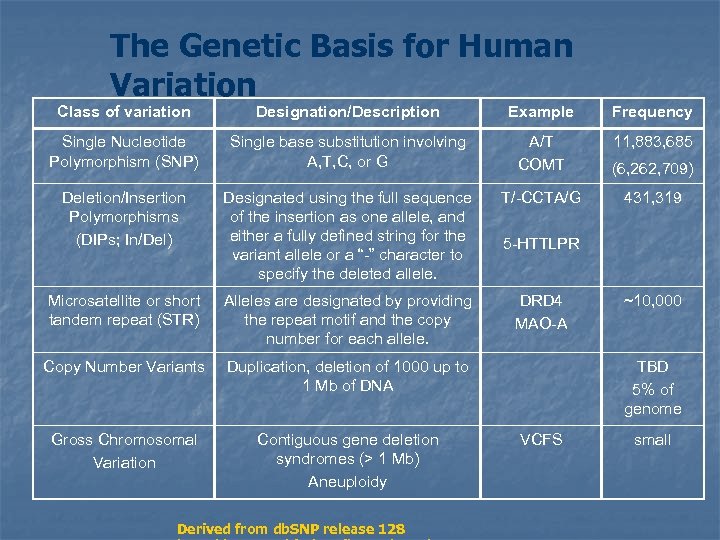

The Genetic Basis for Human Variation Class of variation Designation/Description Example Frequency Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Single base substitution involving A, T, C, or G A/T COMT 11, 883, 685 (6, 262, 709) Deletion/Insertion Polymorphisms (DIPs; In/Del) Designated using the full sequence of the insertion as one allele, and either a fully defined string for the variant allele or a “-” character to specify the deleted allele. T/-CCTA/G 431, 319 Microsatellite or short tandem repeat (STR) Alleles are designated by providing the repeat motif and the copy number for each allele. DRD 4 MAO-A Copy Number Variants Duplication, deletion of 1000 up to 1 Mb of DNA Gross Chromosomal Variation Contiguous gene deletion syndromes (> 1 Mb) Aneuploidy Derived from db. SNP release 128 5 -HTTLPR ~10, 000 TBD 5% of genome VCFS small

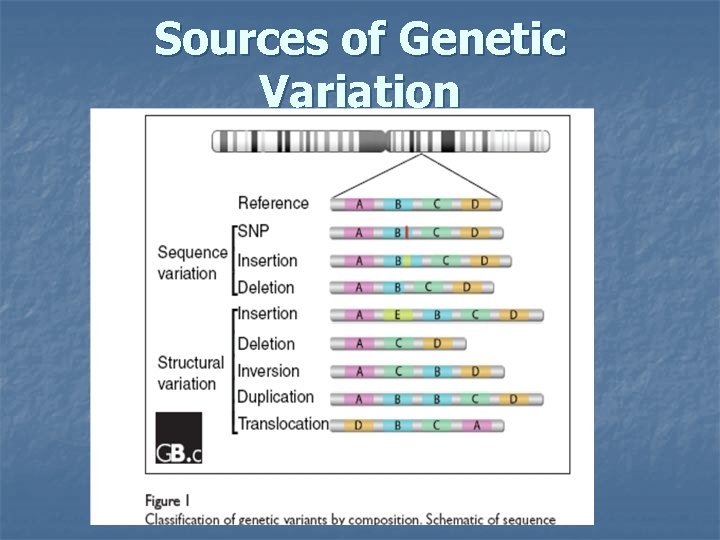

Sources of Genetic Variation

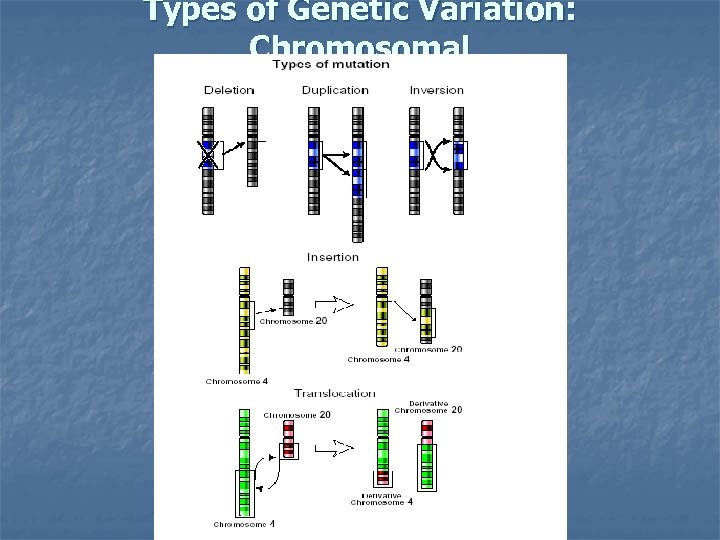

Types of Genetic Variation: Chromosomal

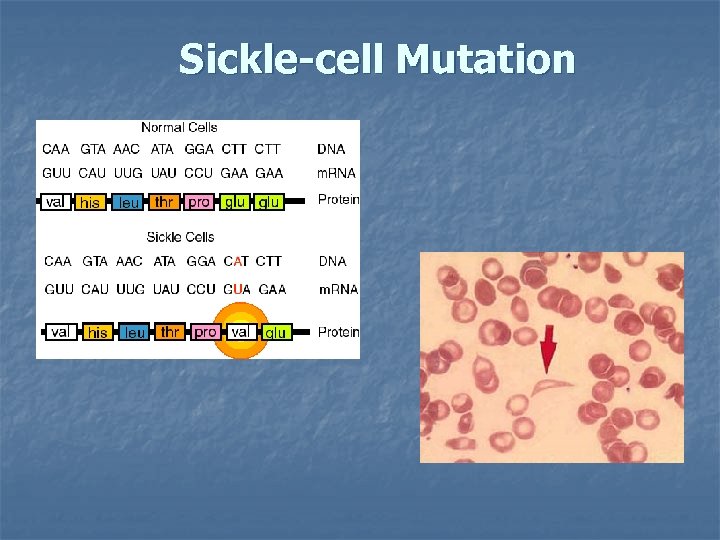

Sickle-cell Mutation

Types of Genetic Variation n n Chromosomal/Structural: Variations (or rearrangements) in the amount of genetic material inherited Polymorphisms: – Variations in the DNA sequence SNPs (~10, 000) n VNTR (STR, SSR) n

Types of Genetic Variation: Variable Number of Tandem Repeats (VNTR) n Microsatellite: Small number of bases (<10) repeated a variable number of times (usually < 100)(>100, 000)

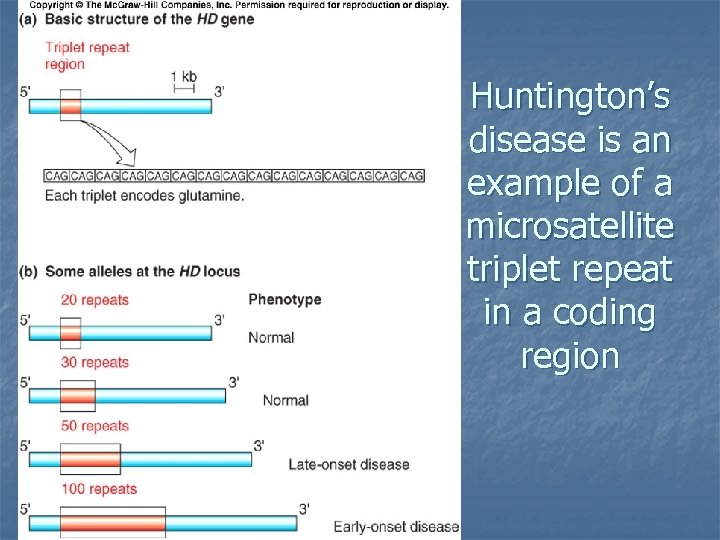

Huntington’s disease is an example of a microsatellite triplet repeat in a coding region

How do researchers link genetic variation to outcomes? n Candidate gene examinations Sometimes from animal models n Specifically examine a small number of polymorphisms and an outcome n Sometimes use family based designs n Replication n n Gene association studies/Genome wide association studies (GWAS) n Gene-finding exercise (atheoretical)

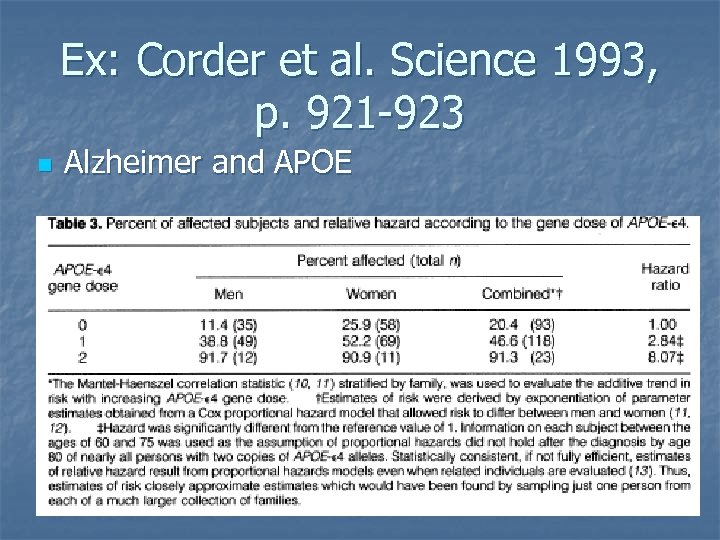

Ex: Corder et al. Science 1993, p. 921 -923 n Alzheimer and APOE

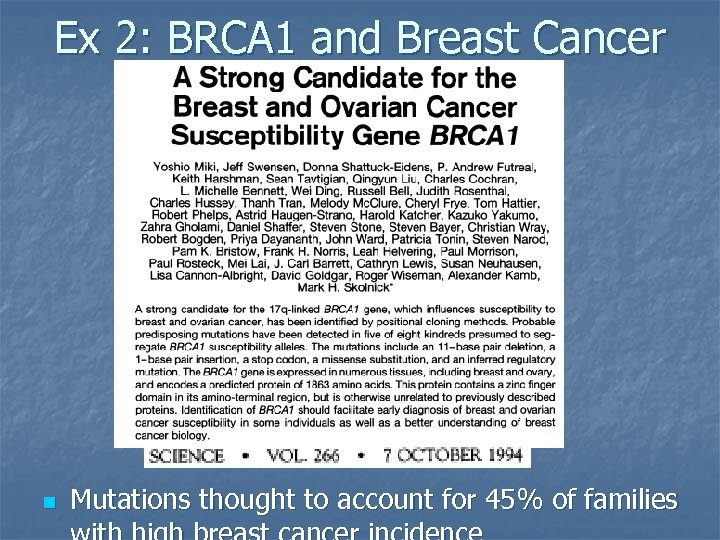

Ex 2: BRCA 1 and Breast Cancer n Mutations thought to account for 45% of families

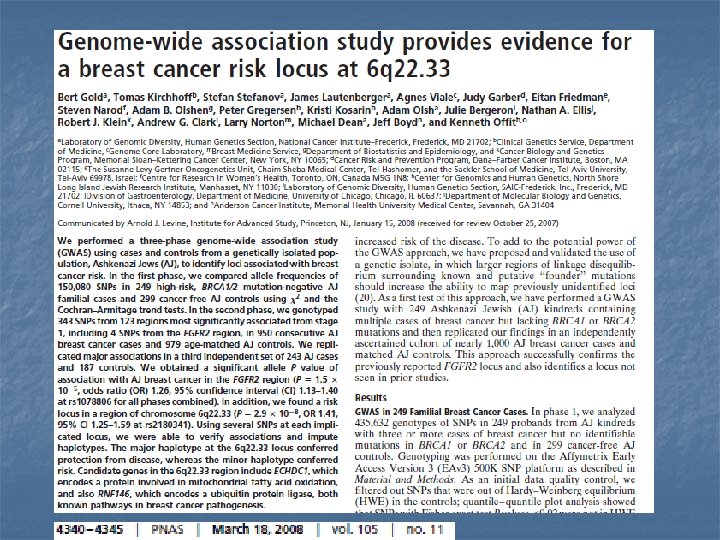

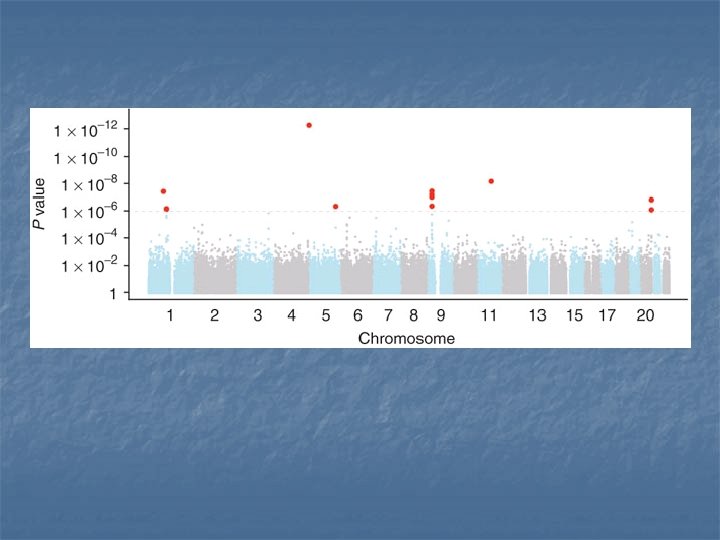

GWAS Example

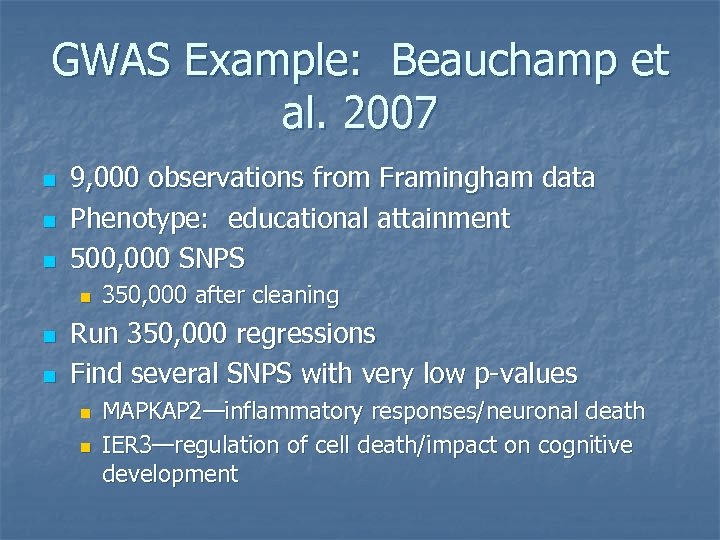

GWAS Example: Beauchamp et al. 2007 n n n 9, 000 observations from Framingham data Phenotype: educational attainment 500, 000 SNPS n n n 350, 000 after cleaning Run 350, 000 regressions Find several SNPS with very low p-values n n MAPKAP 2—inflammatory responses/neuronal death IER 3—regulation of cell death/impact on cognitive development

GWAS vs. Candidate Gene n More powerful for low penetrance variants Better resolution, reduce region of interest Do not need to specify particular variants n But… n n

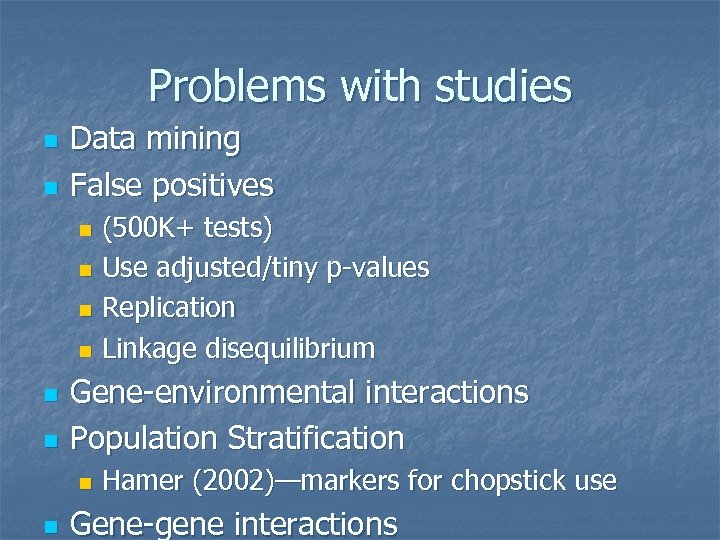

Problems with studies n n Data mining False positives (500 K+ tests) n Use adjusted/tiny p-values n Replication n Linkage disequilibrium n n n Gene-environmental interactions Population Stratification n n Hamer (2002)—markers for chopstick use Gene-gene interactions

Integrating Genetics and Social Science n Improve theory/empirics n Gene X Environment Interactions n New sources of variation

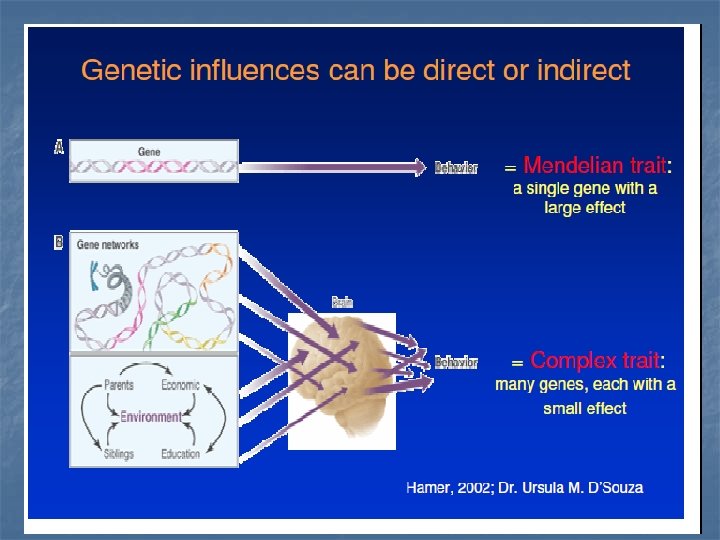

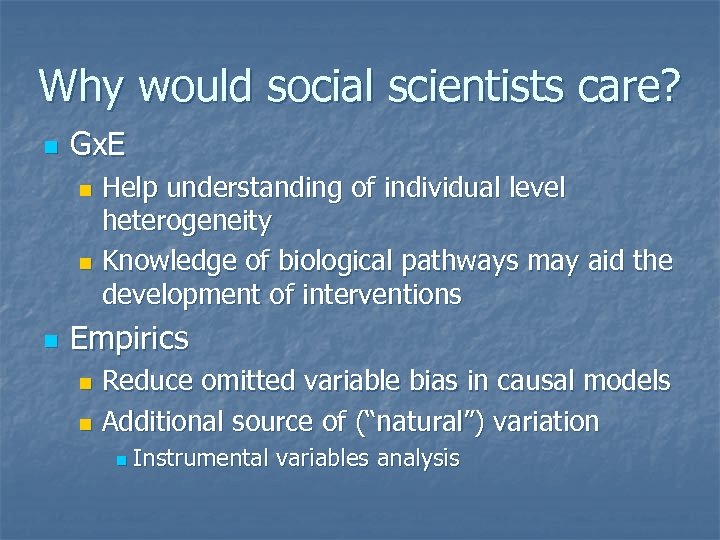

Why would social scientists care? n Gx. E Help understanding of individual level heterogeneity n Knowledge of biological pathways may aid the development of interventions n n Empirics Reduce omitted variable bias in causal models n Additional source of (“natural”) variation n n Instrumental variables analysis

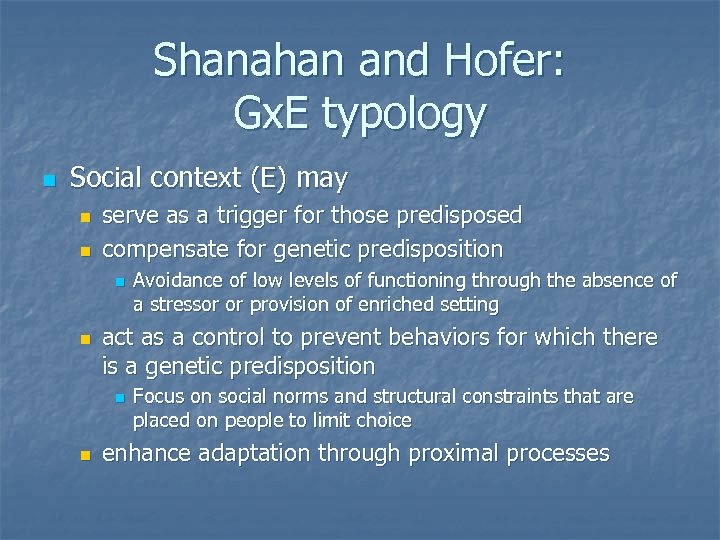

Shanahan and Hofer: Gx. E typology n Social context (E) may n n serve as a trigger for those predisposed compensate for genetic predisposition n n act as a control to prevent behaviors for which there is a genetic predisposition n n Avoidance of low levels of functioning through the absence of a stressor or provision of enriched setting Focus on social norms and structural constraints that are placed on people to limit choice enhance adaptation through proximal processes

Shanahan and Hofer: Promise of Gx. E n n Conclusive evidence from animal models Genetic main effects have been elusive and small n n n But we think that “genes matter” Gene-environment correlations likely will not completely explain variation in outcomes Emerging human evidence

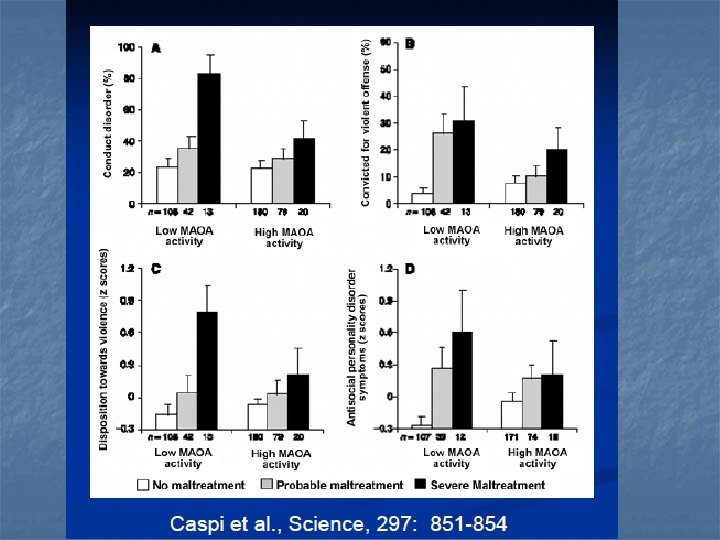

Gene x Environment n Caspi et al. , Science 2002 Why do some maltreated children grow up to develop antisocial behaviors and others do not? n MAOA gene (encodes neurotransmittermetabolizing enzyme) n n n Animal model evidence Found to moderate the effect of childhood maltreatment

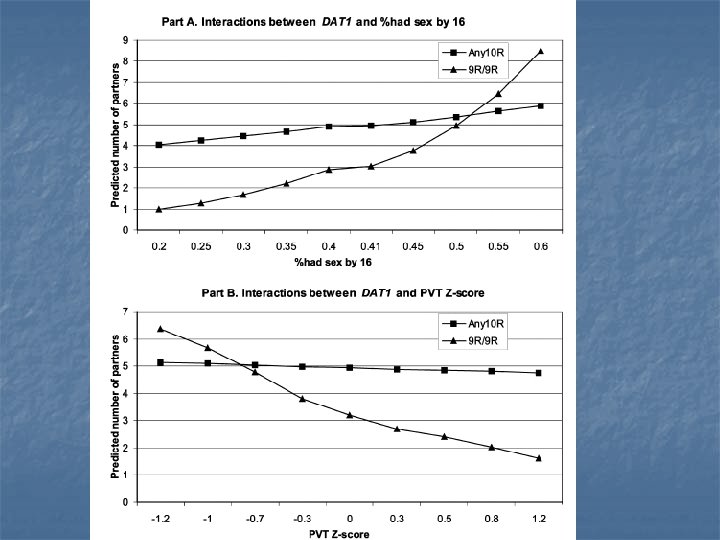

Example: Guo et al. 2008 AJS n n n Outcome: number of sexual partners Gene: DAT (dopamine transporter) Environment: school-level norms: % of kids who have sex early n Cognitive ability n

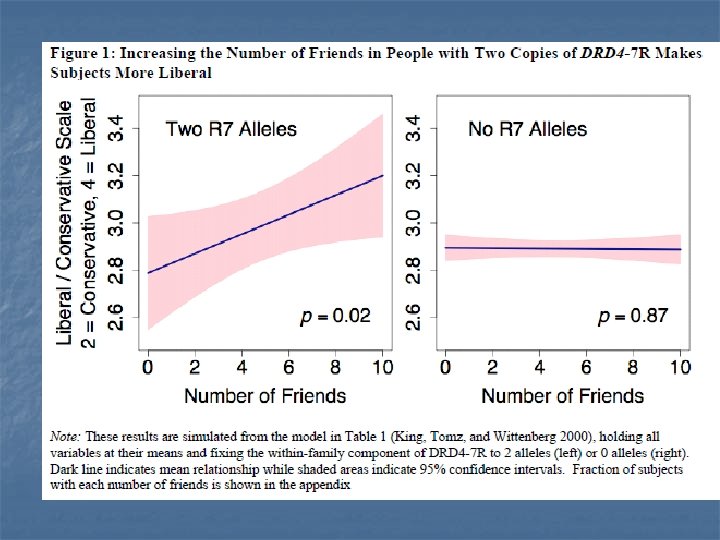

n Forthcoming, Journal of Politics

Issues with Gx. E studies n n n Non-replication Theory Measurement of Environment n n n Endogenous vs. Exogenous Power Data n Environmental variation

Other issues: Shanahan and Hofer n n Static vs. dynamics Multifaceted nature of E Mediating mechanisms Simple statistical models

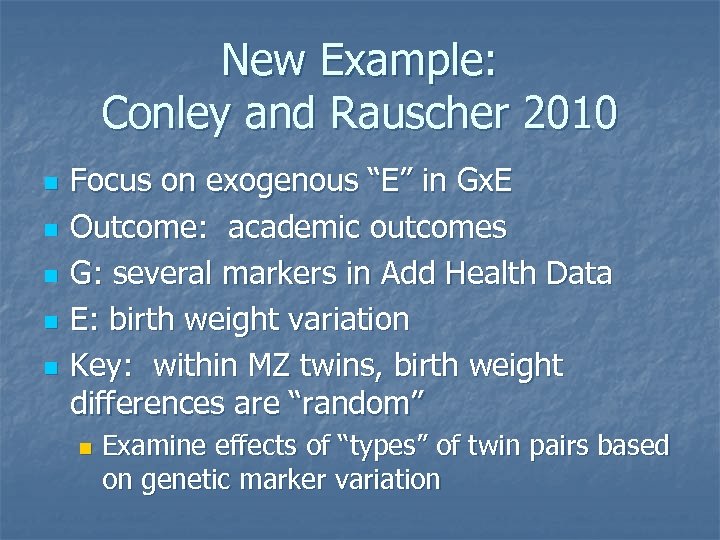

New Example: Conley and Rauscher 2010 n n n Focus on exogenous “E” in Gx. E Outcome: academic outcomes G: several markers in Add Health Data E: birth weight variation Key: within MZ twins, birth weight differences are “random” n Examine effects of “types” of twin pairs based on genetic marker variation

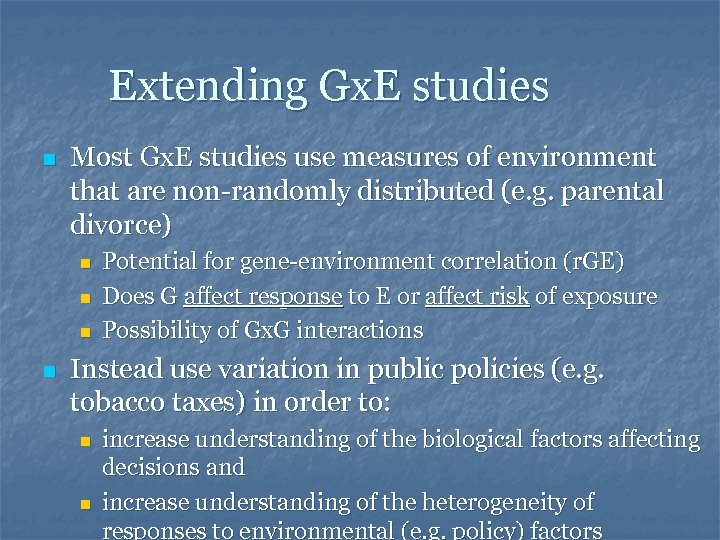

Extending Gx. E studies n Most Gx. E studies use measures of environment that are non-randomly distributed (e. g. parental divorce) n n Potential for gene-environment correlation (r. GE) Does G affect response to E or affect risk of exposure Possibility of Gx. G interactions Instead use variation in public policies (e. g. tobacco taxes) in order to: n n increase understanding of the biological factors affecting decisions and increase understanding of the heterogeneity of responses to environmental (e. g. policy) factors

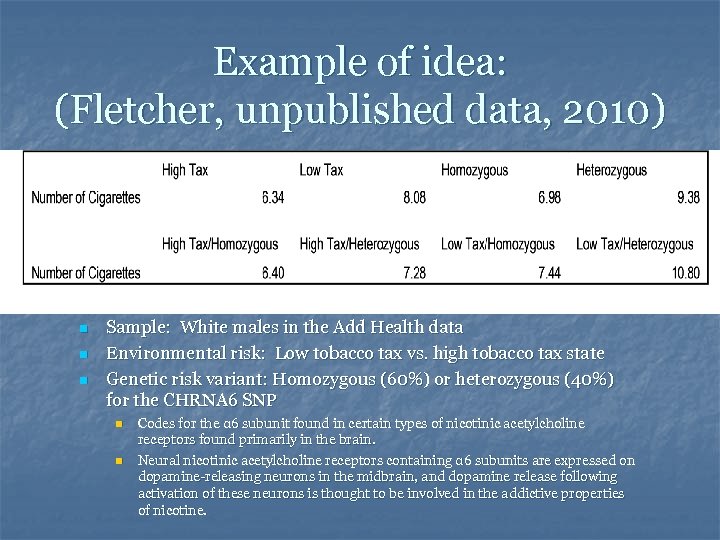

Example of idea: (Fletcher, unpublished data, 2010) n n n Sample: White males in the Add Health data Environmental risk: Low tobacco tax vs. high tobacco tax state Genetic risk variant: Homozygous (60%) or heterozygous (40%) for the CHRNA 6 SNP n n Codes for the α 6 subunit found in certain types of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors found primarily in the brain. Neural nicotinic acetylcholine receptors containing α 6 subunits are expressed on dopamine-releasing neurons in the midbrain, and dopamine release following activation of these neurons is thought to be involved in the addictive properties of nicotine.

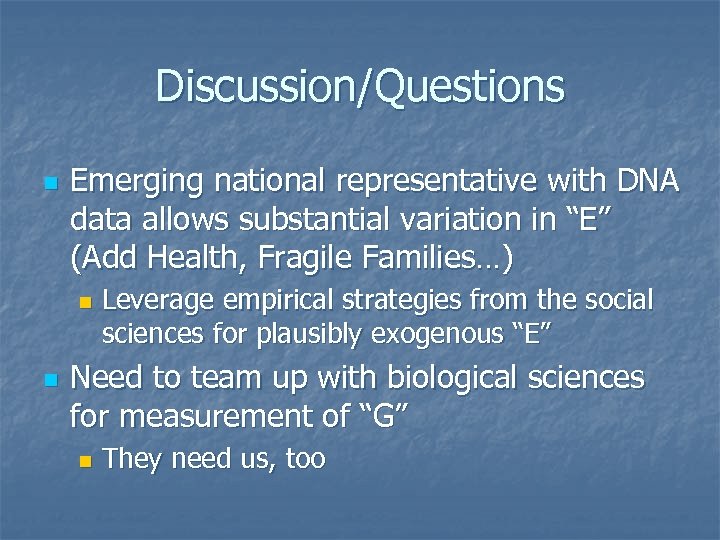

Discussion/Questions n Emerging national representative with DNA data allows substantial variation in “E” (Add Health, Fragile Families…) n n Leverage empirical strategies from the social sciences for plausibly exogenous “E” Need to team up with biological sciences for measurement of “G” n They need us, too

Genetics and Social Science II: New Variation for Causal Inference

Genetic Lotteries within Families Jason M. Fletcher Yale University Steven F. Lehrer Queen’s University

Motivation n n Tremendous advances in research that links molecular genetic markers to health outcomes How might social scientists (economists) leverage new knowledge to advance our own research? n n n Example: links between health and schooling Or: income, socioeconomic status, occupation, labor force participation, marital status… Idea: use sibling differences in genetic inheritance as an “experiment in nature” in order to trace through the effects of poor health on schooling

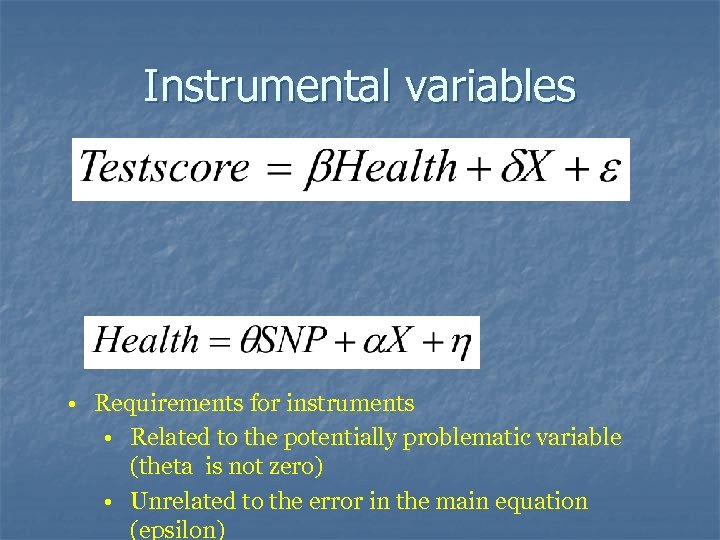

Empirical Example n Issues: n Health and the error term may be correlated n Reverse causality • Would like experimental variation in health, uncorrelated with epsilon • Instrumental variable

A Start: Mendelian Randomization n Definition n Random assortment of genes from parents to offspring that occurs during gamete formation and conception (Smith and Ebrahim IJE 2003) n Used in a growing number of studies n Strengths Not generally susceptible to reverse causation n Scientific basic for link n

Instrumental variables • Requirements for instruments • Related to the potentially problematic variable (theta is not zero) • Unrelated to the error in the main equation (epsilon)

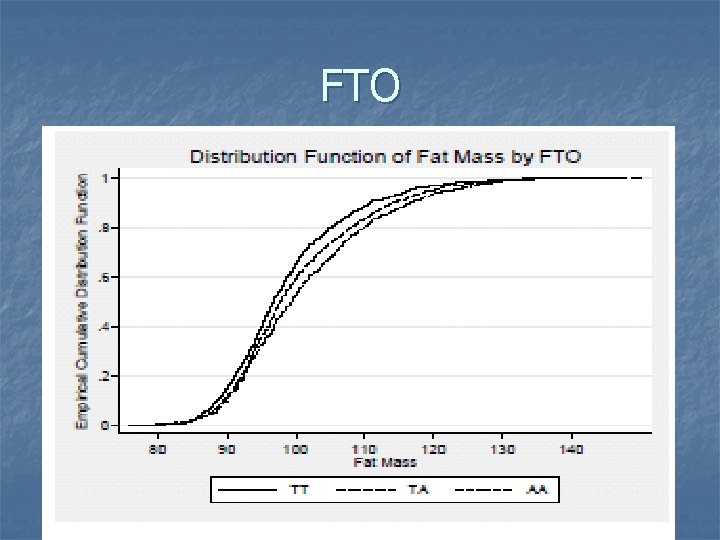

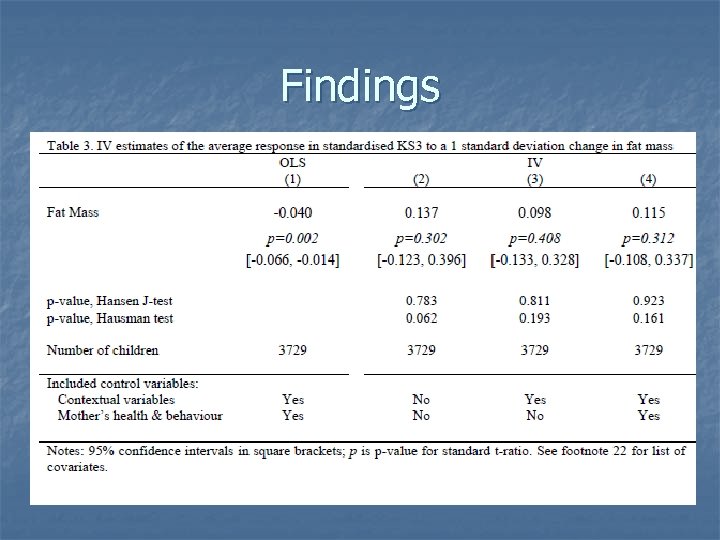

Example: Von Hinke et al. 2010 n n n Examines causal effects of child fat mass on academic achievement ALSPAC data—Avon, England; 12, 000 kids followed from birth Instrument: FTO gene 1 -4 pound increase n R-square is <1% n

FTO n Findings: OLS, 1 SD increase in fat mass reduces achievement by 0. 1 points

Findings

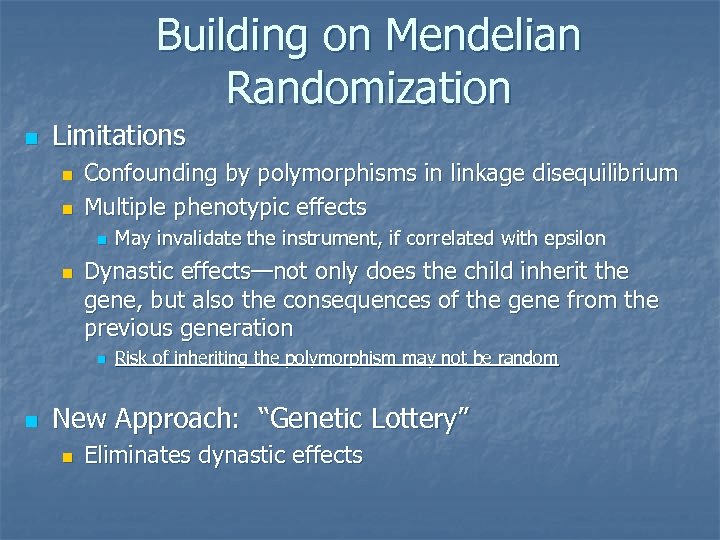

Building on Mendelian Randomization n Limitations n n Confounding by polymorphisms in linkage disequilibrium Multiple phenotypic effects n n Dynastic effects—not only does the child inherit the gene, but also the consequences of the gene from the previous generation n n May invalidate the instrument, if correlated with epsilon Risk of inheriting the polymorphism may not be random New Approach: “Genetic Lottery” n Eliminates dynastic effects

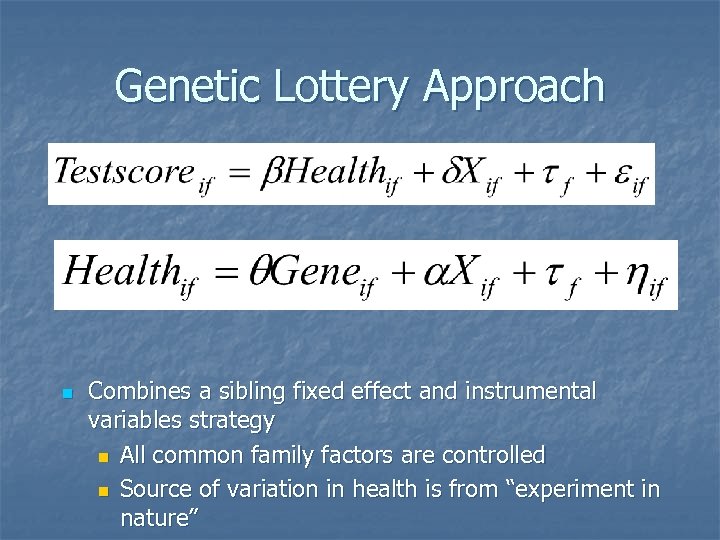

Genetic Lottery Approach n Combines a sibling fixed effect and instrumental variables strategy n All common family factors are controlled n Source of variation in health is from “experiment in nature”

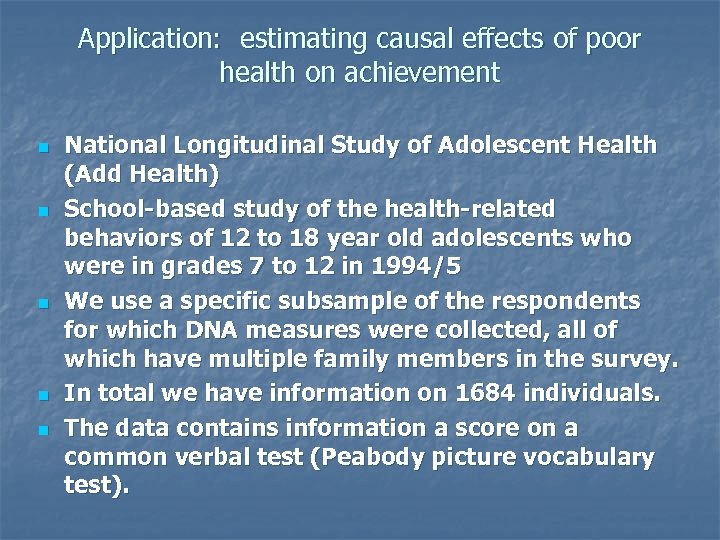

Application: estimating causal effects of poor health on achievement n n n National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) School-based study of the health-related behaviors of 12 to 18 year old adolescents who were in grades 7 to 12 in 1994/5 We use a specific subsample of the respondents for which DNA measures were collected, all of which have multiple family members in the survey. In total we have information on 1684 individuals. The data contains information a score on a common verbal test (Peabody picture vocabulary test).

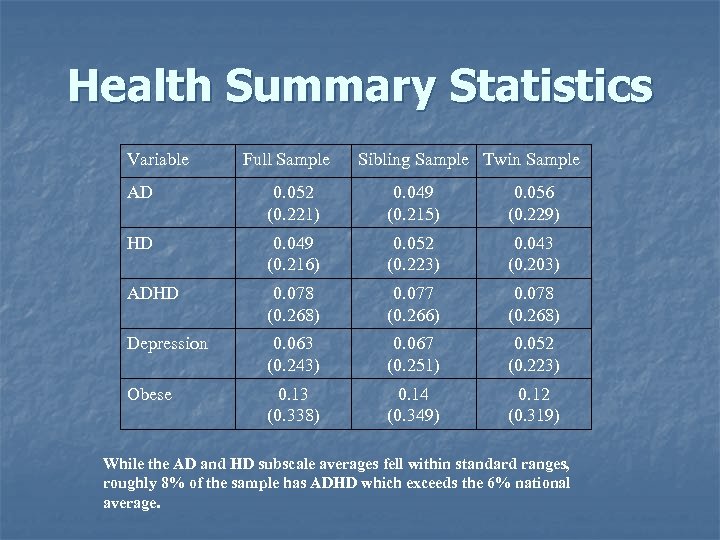

Health Summary Statistics Variable Full Sample Sibling Sample Twin Sample AD 0. 052 (0. 221) 0. 049 (0. 215) 0. 056 (0. 229) HD 0. 049 (0. 216) 0. 052 (0. 223) 0. 043 (0. 203) ADHD 0. 078 (0. 268) 0. 077 (0. 266) 0. 078 (0. 268) Depression 0. 063 (0. 243) 0. 067 (0. 251) 0. 052 (0. 223) Obese 0. 13 (0. 338) 0. 14 (0. 349) 0. 12 (0. 319) While the AD and HD subscale averages fell within standard ranges, roughly 8% of the sample has ADHD which exceeds the 6% national average.

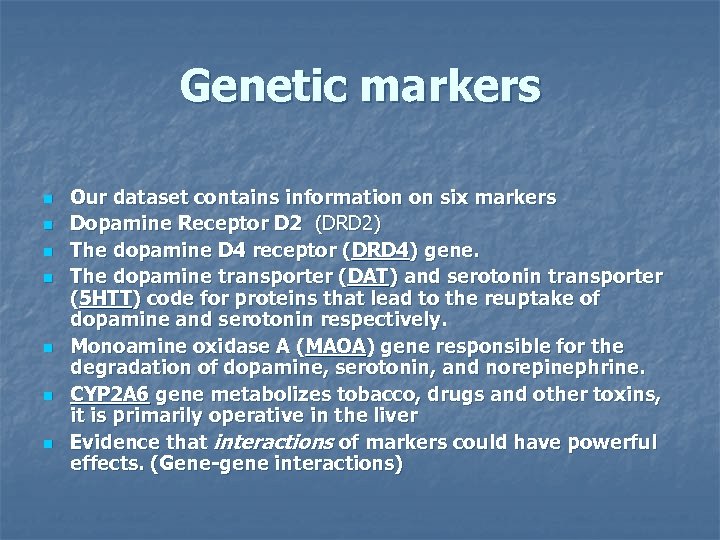

Genetic markers n n n n Our dataset contains information on six markers Dopamine Receptor D 2 (DRD 2) The dopamine D 4 receptor (DRD 4) gene. The dopamine transporter (DAT) and serotonin transporter (5 HTT) code for proteins that lead to the reuptake of dopamine and serotonin respectively. Monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) gene responsible for the degradation of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. CYP 2 A 6 gene metabolizes tobacco, drugs and other toxins, it is primarily operative in the liver Evidence that interactions of markers could have powerful effects. (Gene-gene interactions)

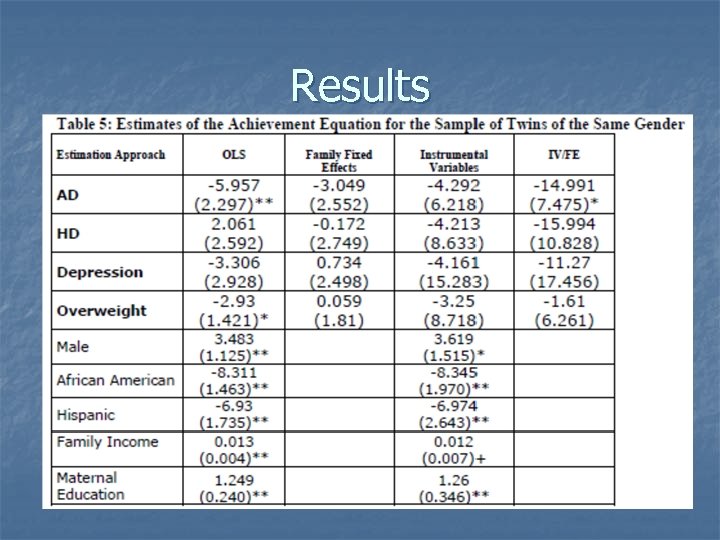

Results

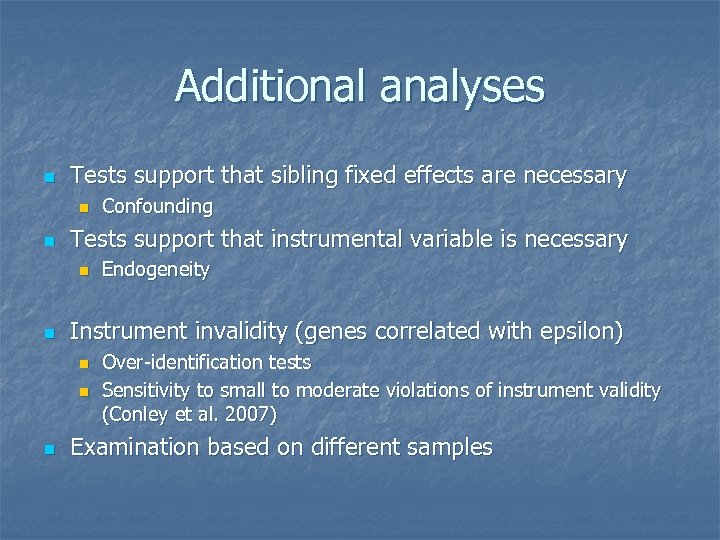

Additional analyses n Tests support that sibling fixed effects are necessary n n Tests support that instrumental variable is necessary n n Endogeneity Instrument invalidity (genes correlated with epsilon) n n n Confounding Over-identification tests Sensitivity to small to moderate violations of instrument validity (Conley et al. 2007) Examination based on different samples

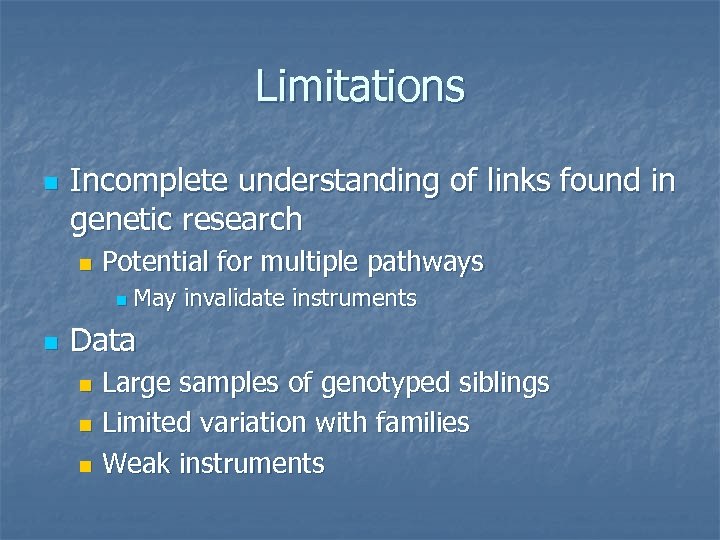

Limitations n Incomplete understanding of links found in genetic research n Potential for multiple pathways n n May invalidate instruments Data Large samples of genotyped siblings n Limited variation with families n Weak instruments n

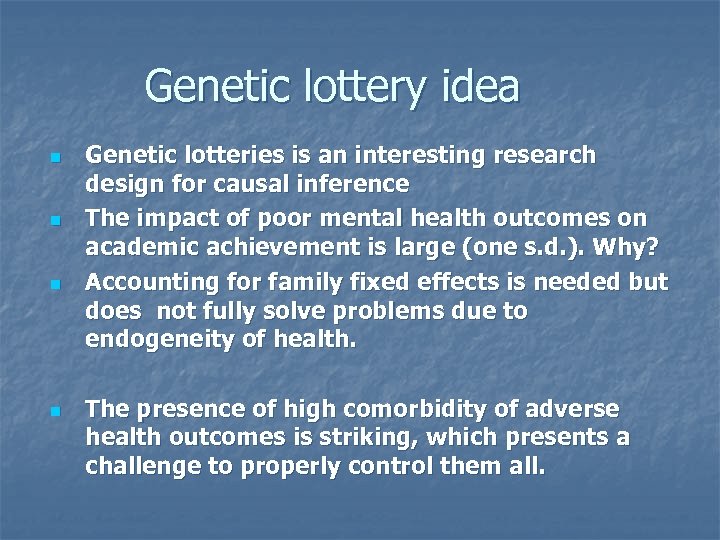

Genetic lottery idea n n Genetic lotteries is an interesting research design for causal inference The impact of poor mental health outcomes on academic achievement is large (one s. d. ). Why? Accounting for family fixed effects is needed but does not fully solve problems due to endogeneity of health. The presence of high comorbidity of adverse health outcomes is striking, which presents a challenge to properly control them all.

Discussion/Questions

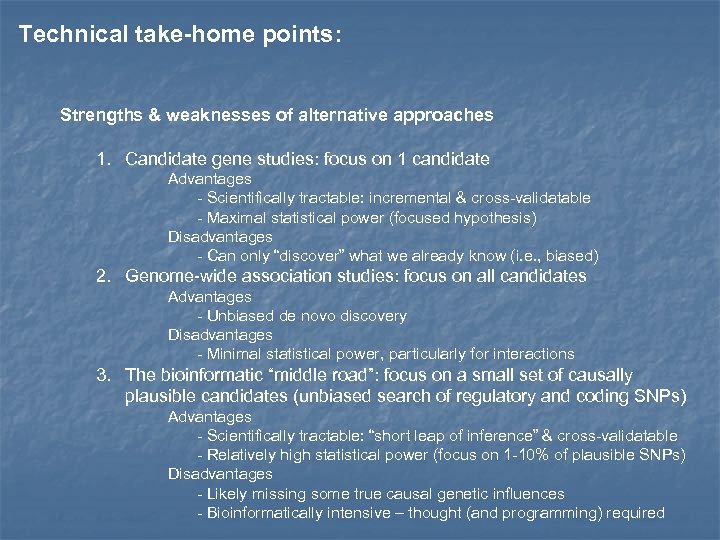

Technical take-home points: Strengths & weaknesses of alternative approaches 1. Candidate gene studies: focus on 1 candidate Advantages - Scientifically tractable: incremental & cross-validatable - Maximal statistical power (focused hypothesis) Disadvantages - Can only “discover” what we already know (i. e. , biased) 2. Genome-wide association studies: focus on all candidates Advantages - Unbiased de novo discovery Disadvantages - Minimal statistical power, particularly for interactions 3. The bioinformatic “middle road”: focus on a small set of causally plausible candidates (unbiased search of regulatory and coding SNPs) Advantages - Scientifically tractable: “short leap of inference” & cross-validatable - Relatively high statistical power (focus on 1 -10% of plausible SNPs) Disadvantages - Likely missing some true causal genetic influences - Bioinformatically intensive – thought (and programming) required

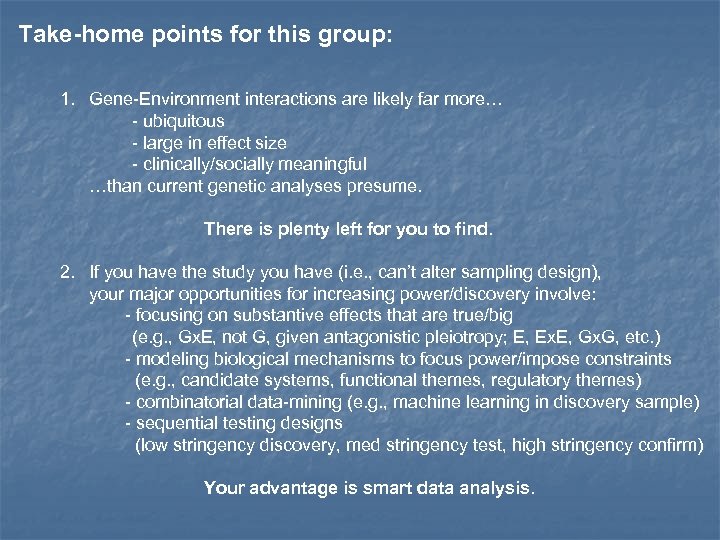

Take-home points for this group: 1. Gene-Environment interactions are likely far more… - ubiquitous - large in effect size - clinically/socially meaningful …than current genetic analyses presume. There is plenty left for you to find. 2. If you have the study you have (i. e. , can’t alter sampling design), your major opportunities for increasing power/discovery involve: - focusing on substantive effects that are true/big (e. g. , Gx. E, not G, given antagonistic pleiotropy; E, Ex. E, Gx. G, etc. ) - modeling biological mechanisms to focus power/impose constraints (e. g. , candidate systems, functional themes, regulatory themes) - combinatorial data-mining (e. g. , machine learning in discovery sample) - sequential testing designs (low stringency discovery, med stringency test, high stringency confirm) Your advantage is smart data analysis.

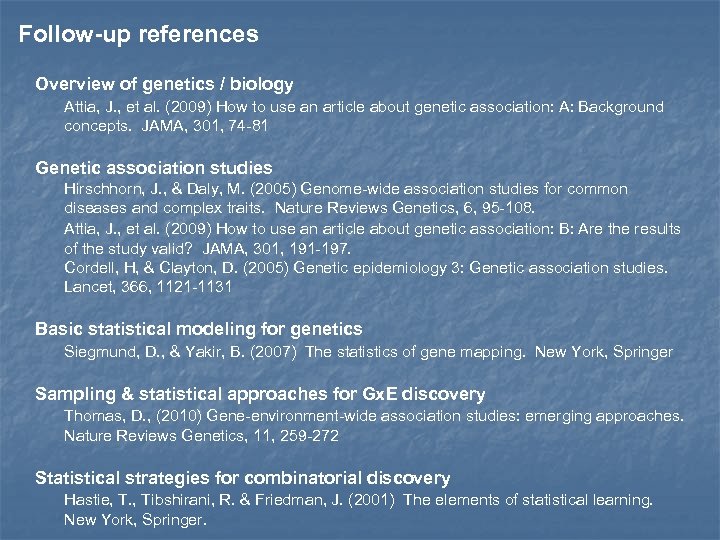

Follow-up references Overview of genetics / biology Attia, J. , et al. (2009) How to use an article about genetic association: A: Background concepts. JAMA, 301, 74 -81 Genetic association studies Hirschhorn, J. , & Daly, M. (2005) Genome-wide association studies for common diseases and complex traits. Nature Reviews Genetics, 6, 95 -108. Attia, J. , et al. (2009) How to use an article about genetic association: B: Are the results of the study valid? JAMA, 301, 191 -197. Cordell, H, & Clayton, D. (2005) Genetic epidemiology 3: Genetic association studies. Lancet, 366, 1121 -1131 Basic statistical modeling for genetics Siegmund, D. , & Yakir, B. (2007) The statistics of gene mapping. New York, Springer Sampling & statistical approaches for Gx. E discovery Thomas, D. , (2010) Gene-environment-wide association studies: emerging approaches. Nature Reviews Genetics, 11, 259 -272 Statistical strategies for combinatorial discovery Hastie, T. , Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J. (2001) The elements of statistical learning. New York, Springer.

Acknowledgements n BG Model slides n http: //www. psych. umn. edu/courses/fall 09/mc guem/psy 5137/lectures. htm

2f1c11ec33e7c44bf6df0bc9f0a764f1.ppt