d8ea6149bffa9816de74ad9d550a22fe.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 36

Inequality, poverty, social exclusion and policy John Hills ESRC Research Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion International Centre for Health and Society 23 October 2002

Inequality, poverty, social exclusion and policy John Hills ESRC Research Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion International Centre for Health and Society 23 October 2002

• • Views of ‘what is social exclusion? ’ Links between dimensions of exclusion Links over time: incomes Does talking about ‘social exclusion’ change the policy agenda? • How well are current policies matching up?

• • Views of ‘what is social exclusion? ’ Links between dimensions of exclusion Links over time: incomes Does talking about ‘social exclusion’ change the policy agenda? • How well are current policies matching up?

What is ‘social exclusion’? Social Exclusion Unit “… a short-hand label for what can happen when individuals or areas suffer from a concentration of linked problems such as unemployment, poor skills, low income, poor housing, high crime, bad health and family breakdown”

What is ‘social exclusion’? Social Exclusion Unit “… a short-hand label for what can happen when individuals or areas suffer from a concentration of linked problems such as unemployment, poor skills, low income, poor housing, high crime, bad health and family breakdown”

Ruth Levitas (‘The Inclusive Society’) MUD: Code for ‘the underclass’ SID: Focus on participation in paid work. Ignores importance of unpaid work and poverty of non-workers RED: Poverty is the central issue, but goes beyond material poverty, and focuses on processes that produce inequality

Ruth Levitas (‘The Inclusive Society’) MUD: Code for ‘the underclass’ SID: Focus on participation in paid work. Ignores importance of unpaid work and poverty of non-workers RED: Poverty is the central issue, but goes beyond material poverty, and focuses on processes that produce inequality

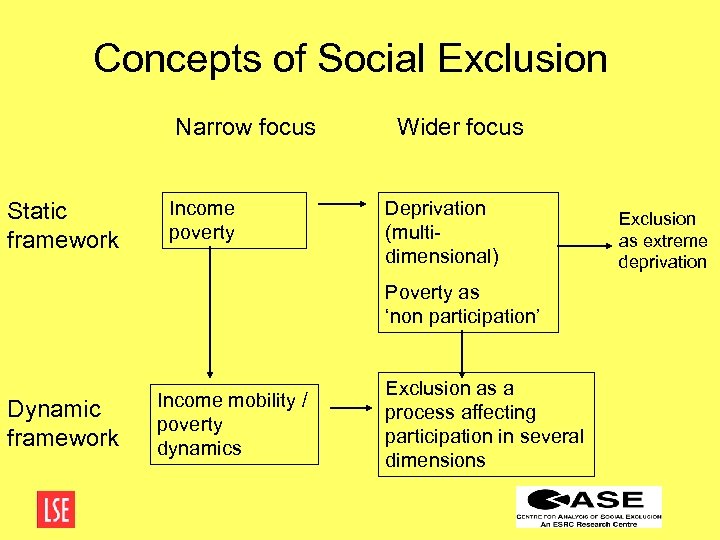

Concepts of Social Exclusion Narrow focus Static framework Income poverty Wider focus Deprivation (multidimensional) Poverty as ‘non participation’ Dynamic framework Income mobility / poverty dynamics Exclusion as a process affecting participation in several dimensions Exclusion as extreme deprivation

Concepts of Social Exclusion Narrow focus Static framework Income poverty Wider focus Deprivation (multidimensional) Poverty as ‘non participation’ Dynamic framework Income mobility / poverty dynamics Exclusion as a process affecting participation in several dimensions Exclusion as extreme deprivation

‘……incorporating multidimensional measures of disadvantage into poverty measurement…in effect forces one to make the shift to a dynamic analysis of processes’ (Nolan and Whelan, 1996)

‘……incorporating multidimensional measures of disadvantage into poverty measurement…in effect forces one to make the shift to a dynamic analysis of processes’ (Nolan and Whelan, 1996)

‘If…poverty is seen in terms of income deprivation only, then introducing the notion of social exclusion as part of poverty would vastly broaden the domain of poverty analysis. However, if poverty is seen as deprivation of basic capabilities, then there is no real expansion of domain of coverage, but a very important pointer to a useful investigative focus’ (Sen, 2000)

‘If…poverty is seen in terms of income deprivation only, then introducing the notion of social exclusion as part of poverty would vastly broaden the domain of poverty analysis. However, if poverty is seen as deprivation of basic capabilities, then there is no real expansion of domain of coverage, but a very important pointer to a useful investigative focus’ (Sen, 2000)

FOUR ASPECTS OF ‘SOCIALEXCLUSION’ • It is about participation in today’s society. Inclusion/exclusion are matters of degree. They are relative to the society in question. • Multi-dimensional: includes income/consumption poverty, but also involvement in productive activity, political participation and social interaction. • Dynamics: inclusion and exclusion are processes which happen over time. • Multi-layered: operates at different levels – individual, household, community/neighbourhood, institutions.

FOUR ASPECTS OF ‘SOCIALEXCLUSION’ • It is about participation in today’s society. Inclusion/exclusion are matters of degree. They are relative to the society in question. • Multi-dimensional: includes income/consumption poverty, but also involvement in productive activity, political participation and social interaction. • Dynamics: inclusion and exclusion are processes which happen over time. • Multi-layered: operates at different levels – individual, household, community/neighbourhood, institutions.

Evidence on extent of exclusion: summary • There’s not much social exclusion about: no evidence of an ‘underclass’ • There’s lots of social exclusion about: the links between dimensions and over time are strong, but not deterministic

Evidence on extent of exclusion: summary • There’s not much social exclusion about: no evidence of an ‘underclass’ • There’s lots of social exclusion about: the links between dimensions and over time are strong, but not deterministic

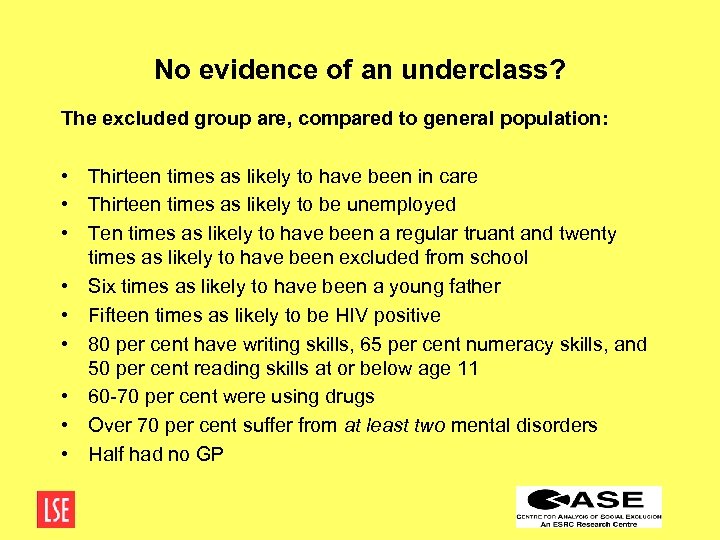

No evidence of an underclass? The excluded group are, compared to general population: • Thirteen times as likely to have been in care • Thirteen times as likely to be unemployed • Ten times as likely to have been a regular truant and twenty times as likely to have been excluded from school • Six times as likely to have been a young father • Fifteen times as likely to be HIV positive • 80 per cent have writing skills, 65 per cent numeracy skills, and 50 per cent reading skills at or below age 11 • 60 -70 per cent were using drugs • Over 70 per cent suffer from at least two mental disorders • Half had no GP

No evidence of an underclass? The excluded group are, compared to general population: • Thirteen times as likely to have been in care • Thirteen times as likely to be unemployed • Ten times as likely to have been a regular truant and twenty times as likely to have been excluded from school • Six times as likely to have been a young father • Fifteen times as likely to be HIV positive • 80 per cent have writing skills, 65 per cent numeracy skills, and 50 per cent reading skills at or below age 11 • 60 -70 per cent were using drugs • Over 70 per cent suffer from at least two mental disorders • Half had no GP

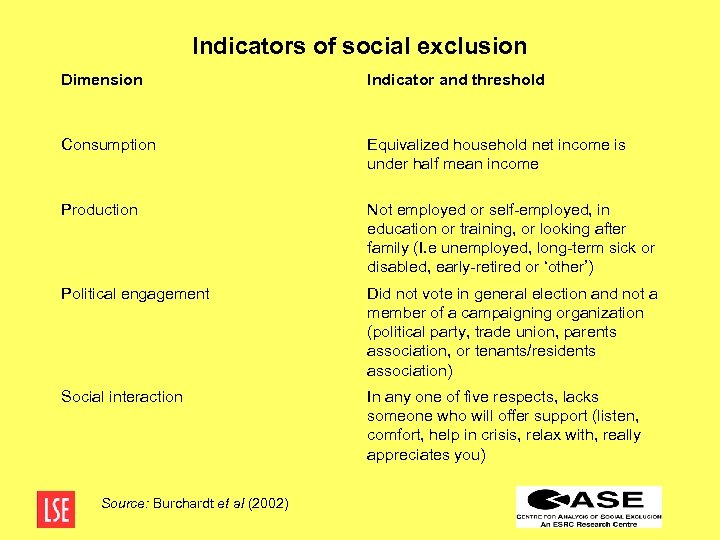

Indicators of social exclusion Dimension Indicator and threshold Consumption Equivalized household net income is under half mean income Production Not employed or self-employed, in education or training, or looking after family (I. e unemployed, long-term sick or disabled, early-retired or ‘other’) Political engagement Did not vote in general election and not a member of a campaigning organization (political party, trade union, parents association, or tenants/residents association) Social interaction In any one of five respects, lacks someone who will offer support (listen, comfort, help in crisis, relax with, really appreciates you) Source: Burchardt et al (2002)

Indicators of social exclusion Dimension Indicator and threshold Consumption Equivalized household net income is under half mean income Production Not employed or self-employed, in education or training, or looking after family (I. e unemployed, long-term sick or disabled, early-retired or ‘other’) Political engagement Did not vote in general election and not a member of a campaigning organization (political party, trade union, parents association, or tenants/residents association) Social interaction In any one of five respects, lacks someone who will offer support (listen, comfort, help in crisis, relax with, really appreciates you) Source: Burchardt et al (2002)

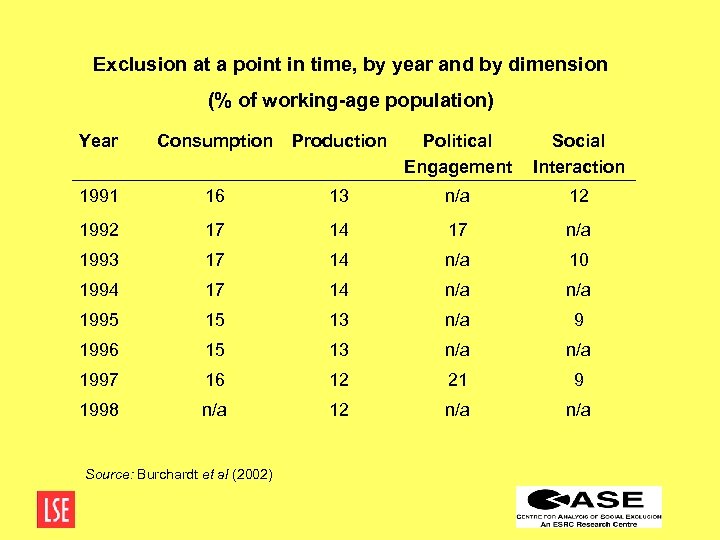

Exclusion at a point in time, by year and by dimension (% of working-age population) Year Consumption Production Political Engagement Social Interaction 1991 16 13 n/a 12 1992 17 14 17 n/a 1993 17 14 n/a 10 1994 17 14 n/a 1995 15 13 n/a 9 1996 15 13 n/a 1997 16 12 21 9 1998 n/a 12 n/a Source: Burchardt et al (2002)

Exclusion at a point in time, by year and by dimension (% of working-age population) Year Consumption Production Political Engagement Social Interaction 1991 16 13 n/a 12 1992 17 14 17 n/a 1993 17 14 n/a 10 1994 17 14 n/a 1995 15 13 n/a 9 1996 15 13 n/a 1997 16 12 21 9 1998 n/a 12 n/a Source: Burchardt et al (2002)

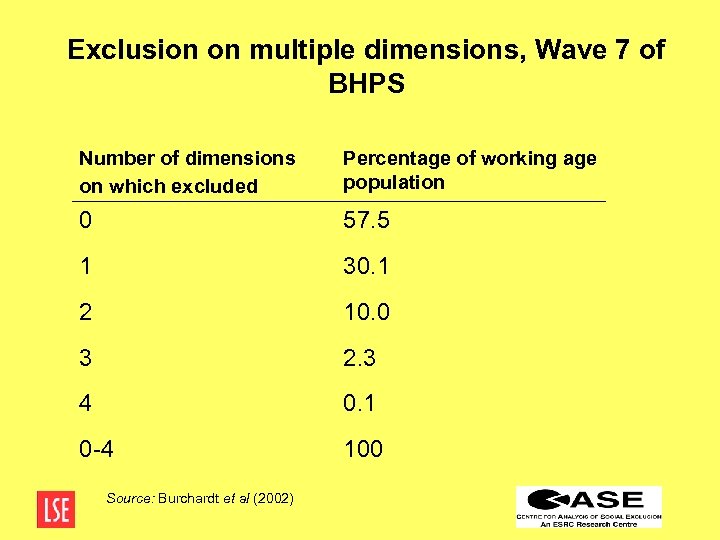

Exclusion on multiple dimensions, Wave 7 of BHPS Number of dimensions on which excluded Percentage of working age population 0 57. 5 1 30. 1 2 10. 0 3 2. 3 4 0. 1 0 -4 100 Source: Burchardt et al (2002)

Exclusion on multiple dimensions, Wave 7 of BHPS Number of dimensions on which excluded Percentage of working age population 0 57. 5 1 30. 1 2 10. 0 3 2. 3 4 0. 1 0 -4 100 Source: Burchardt et al (2002)

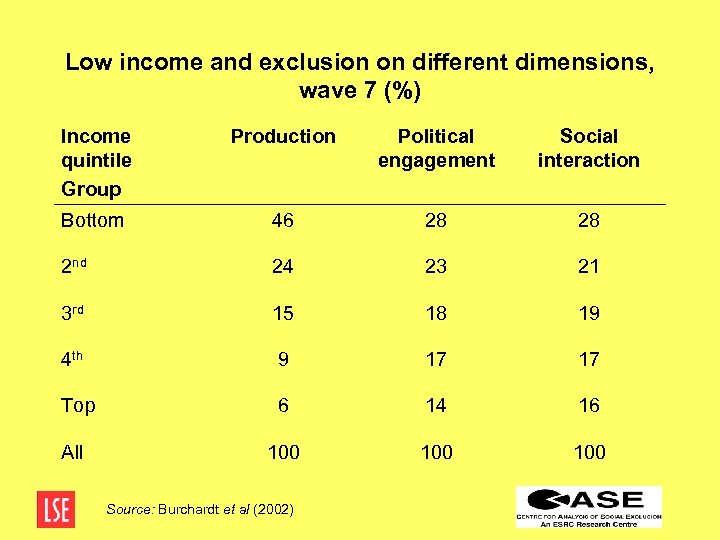

Low income and exclusion on different dimensions, wave 7 (%) Income quintile Group Production Political engagement Social interaction Bottom 46 28 28 2 nd 24 23 21 3 rd 15 18 19 4 th 9 17 17 Top 6 14 16 100 100 All Source: Burchardt et al (2002)

Low income and exclusion on different dimensions, wave 7 (%) Income quintile Group Production Political engagement Social interaction Bottom 46 28 28 2 nd 24 23 21 3 rd 15 18 19 4 th 9 17 17 Top 6 14 16 100 100 All Source: Burchardt et al (2002)

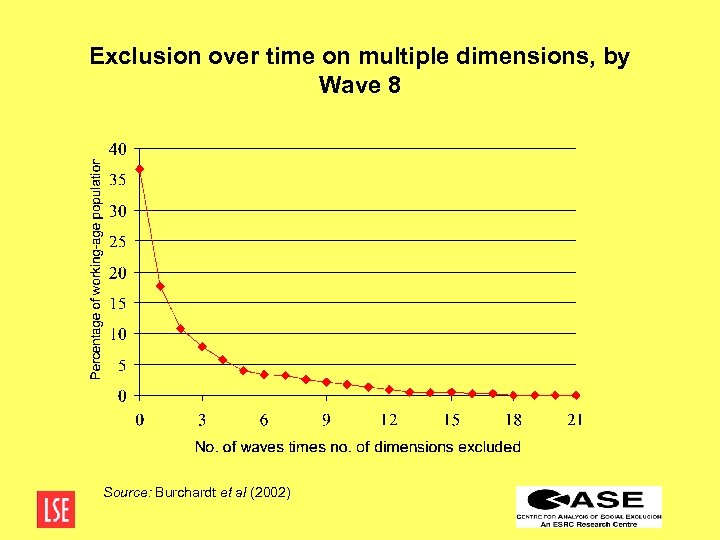

Exclusion over time on multiple dimensions, by Wave 8 Source: Burchardt et al (2002)

Exclusion over time on multiple dimensions, by Wave 8 Source: Burchardt et al (2002)

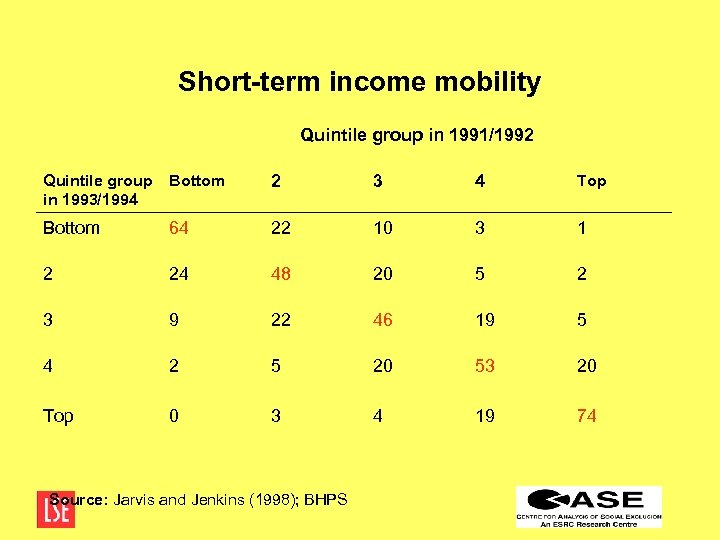

Short-term income mobility Quintile group in 1991/1992 Quintile group in 1993/1994 Bottom 2 3 4 Top Bottom 64 22 10 3 1 2 24 48 20 5 2 3 9 22 46 19 5 4 2 5 20 53 20 Top 0 3 4 19 74 Source: Jarvis and Jenkins (1998); BHPS

Short-term income mobility Quintile group in 1991/1992 Quintile group in 1993/1994 Bottom 2 3 4 Top Bottom 64 22 10 3 1 2 24 48 20 5 2 3 9 22 46 19 5 4 2 5 20 53 20 Top 0 3 4 19 74 Source: Jarvis and Jenkins (1998); BHPS

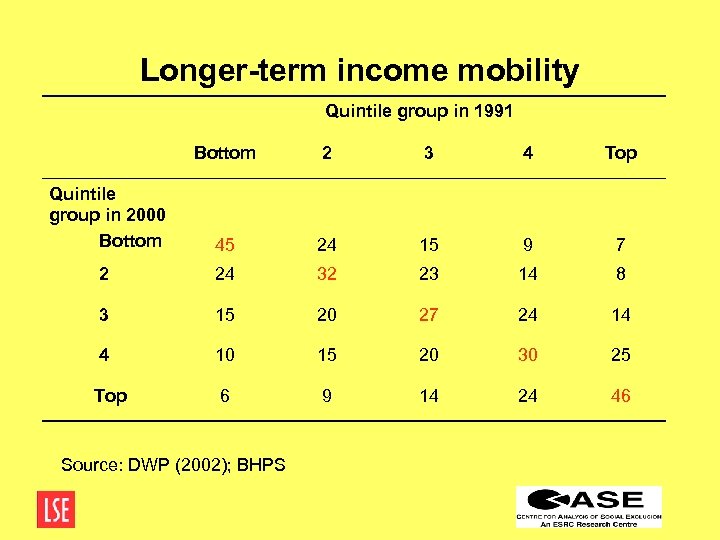

Longer-term income mobility Quintile group in 1991 Bottom 2 3 4 Top Quintile group in 2000 Bottom 45 24 15 9 7 2 24 32 23 14 8 3 15 20 27 24 14 4 10 15 20 30 25 Top 6 9 14 24 46 Source: DWP (2002); BHPS

Longer-term income mobility Quintile group in 1991 Bottom 2 3 4 Top Quintile group in 2000 Bottom 45 24 15 9 7 2 24 32 23 14 8 3 15 20 27 24 14 4 10 15 20 30 25 Top 6 9 14 24 46 Source: DWP (2002); BHPS

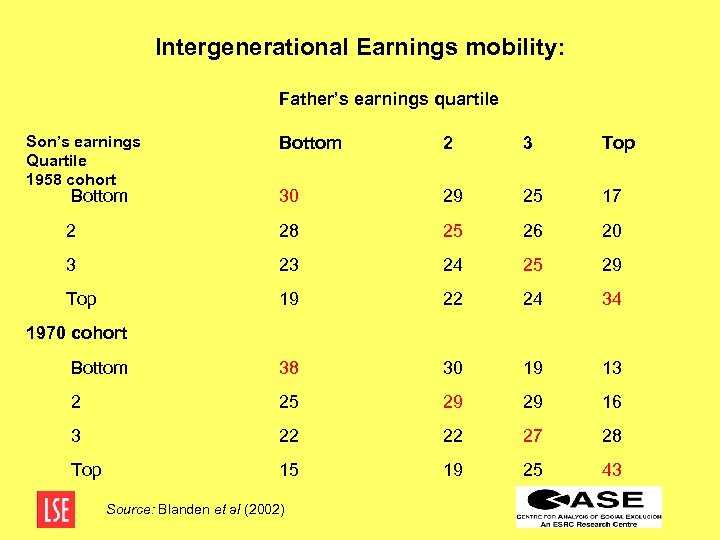

Intergenerational Earnings mobility: Father’s earnings quartile Son’s earnings Quartile 1958 cohort Bottom 2 3 Top Bottom 30 29 25 17 2 28 25 26 20 3 23 24 25 29 Top 19 22 24 34 1970 cohort Bottom 38 30 19 13 2 25 29 29 16 3 22 22 27 28 Top 15 19 25 43 Source: Blanden et al (2002)

Intergenerational Earnings mobility: Father’s earnings quartile Son’s earnings Quartile 1958 cohort Bottom 2 3 Top Bottom 30 29 25 17 2 28 25 26 20 3 23 24 25 29 Top 19 22 24 34 1970 cohort Bottom 38 30 19 13 2 25 29 29 16 3 22 22 27 28 Top 15 19 25 43 Source: Blanden et al (2002)

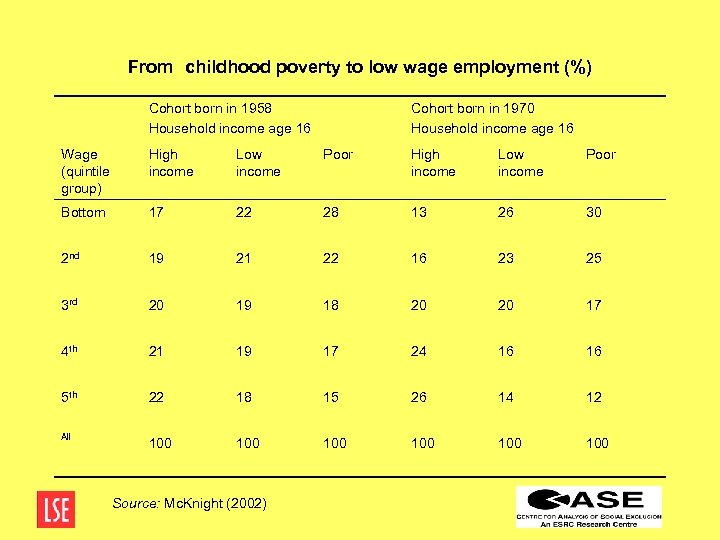

From childhood poverty to low wage employment (%) Cohort born in 1958 Household income age 16 Cohort born in 1970 Household income age 16 Wage (quintile group) High income Low income Poor Bottom 17 22 28 13 26 30 2 nd 19 21 22 16 23 25 3 rd 20 19 18 20 20 17 4 th 21 19 17 24 16 16 5 th 22 18 15 26 14 12 All 100 100 100 Source: Mc. Knight (2002)

From childhood poverty to low wage employment (%) Cohort born in 1958 Household income age 16 Cohort born in 1970 Household income age 16 Wage (quintile group) High income Low income Poor Bottom 17 22 28 13 26 30 2 nd 19 21 22 16 23 25 3 rd 20 19 18 20 20 17 4 th 21 19 17 24 16 16 5 th 22 18 15 26 14 12 All 100 100 100 Source: Mc. Knight (2002)

Summary: Income mobility patterns • There is quite a lot of short-term mobility, but mostly short range • Current income is strongly linked to past income • Recurrent poverty is more common than remorseless poverty • Poverty in the UK and US is more persistent than in other OECD countries • There was little change in poverty persistence in the UK in the 1990 s • Intergenerational links in earnings are strong but not determinant • Intergenerational links appear to have strengthened, comparing those growing up in 60 s and 70 s, with those growing up in 70 s and 80 s.

Summary: Income mobility patterns • There is quite a lot of short-term mobility, but mostly short range • Current income is strongly linked to past income • Recurrent poverty is more common than remorseless poverty • Poverty in the UK and US is more persistent than in other OECD countries • There was little change in poverty persistence in the UK in the 1990 s • Intergenerational links in earnings are strong but not determinant • Intergenerational links appear to have strengthened, comparing those growing up in 60 s and 70 s, with those growing up in 70 s and 80 s.

Childhood experiences and risks of adult exclusion • Consistent and powerful childhood predictors of unfavourable adult outcomes: childhood poverty; family disruption; contact with police; and educational test scores. • Children who experienced consistent poverty were two and a half times as likely to have no qualifications by age 33. • Boys who were poor were a quarter as likely to gain degreelevel qualifications. • Low income in adulthood is related to: poor performance at school; lack of parental interest in schooling (especially men); and childhood poverty • Adult benefit receipt is linked to: poor test scores; childhood poverty; father’s interest in schooling (men); and family circumstances (women) Source: Hobcraft (1998),

Childhood experiences and risks of adult exclusion • Consistent and powerful childhood predictors of unfavourable adult outcomes: childhood poverty; family disruption; contact with police; and educational test scores. • Children who experienced consistent poverty were two and a half times as likely to have no qualifications by age 33. • Boys who were poor were a quarter as likely to gain degreelevel qualifications. • Low income in adulthood is related to: poor performance at school; lack of parental interest in schooling (especially men); and childhood poverty • Adult benefit receipt is linked to: poor test scores; childhood poverty; father’s interest in schooling (men); and family circumstances (women) Source: Hobcraft (1998),

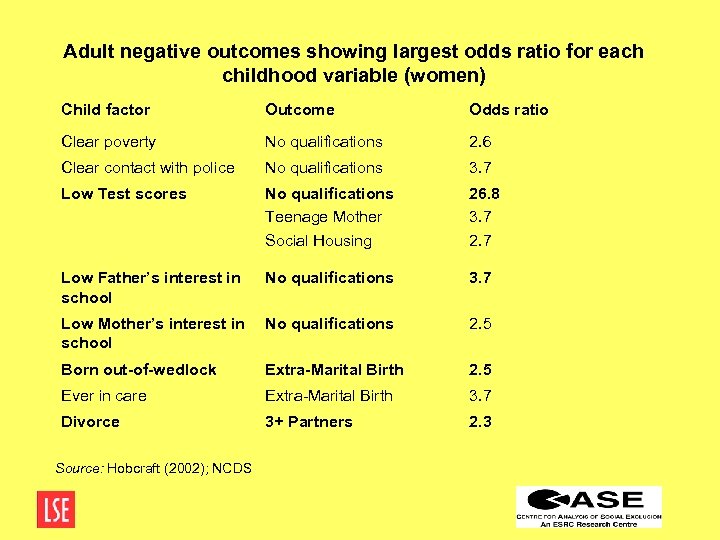

Adult negative outcomes showing largest odds ratio for each childhood variable (women) Child factor Outcome Odds ratio Clear poverty No qualifications 2. 6 Clear contact with police No qualifications 3. 7 Low Test scores No qualifications Teenage Mother Social Housing 26. 8 3. 7 2. 7 Low Father’s interest in school No qualifications 3. 7 Low Mother’s interest in school No qualifications 2. 5 Born out-of-wedlock Extra-Marital Birth 2. 5 Ever in care Extra-Marital Birth 3. 7 Divorce 3+ Partners 2. 3 Source: Hobcraft (2002); NCDS

Adult negative outcomes showing largest odds ratio for each childhood variable (women) Child factor Outcome Odds ratio Clear poverty No qualifications 2. 6 Clear contact with police No qualifications 3. 7 Low Test scores No qualifications Teenage Mother Social Housing 26. 8 3. 7 2. 7 Low Father’s interest in school No qualifications 3. 7 Low Mother’s interest in school No qualifications 2. 5 Born out-of-wedlock Extra-Marital Birth 2. 5 Ever in care Extra-Marital Birth 3. 7 Divorce 3+ Partners 2. 3 Source: Hobcraft (2002); NCDS

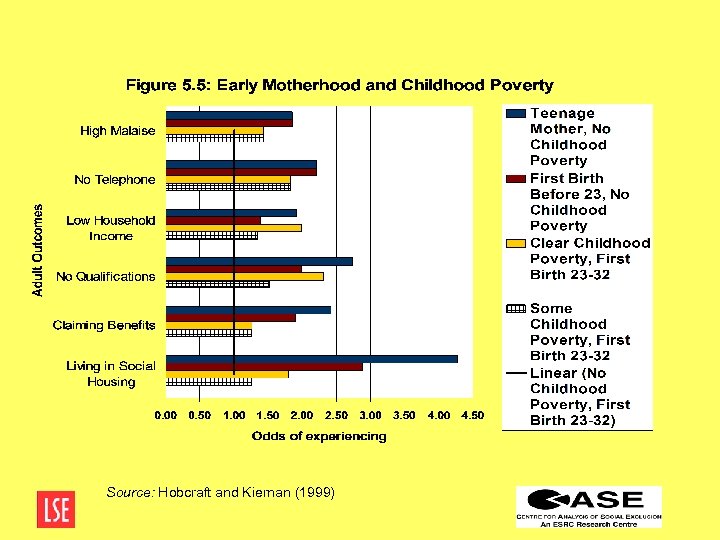

Source: Hobcraft and Kiernan (1999)

Source: Hobcraft and Kiernan (1999)

Drivers of links across the early life-course • Childhood circumstances matter • Early test scores have major links to outcomes • But controlling for a wide range of initial factors, childhood poverty is still associated with adverse outcomes • Family/demographic circumstances matter: eg. teenage motherhood is more strongly associated with adverse outcomes than poverty childhood • Particular childhood factors link most strongly to similar adult factors

Drivers of links across the early life-course • Childhood circumstances matter • Early test scores have major links to outcomes • But controlling for a wide range of initial factors, childhood poverty is still associated with adverse outcomes • Family/demographic circumstances matter: eg. teenage motherhood is more strongly associated with adverse outcomes than poverty childhood • Particular childhood factors link most strongly to similar adult factors

Does a focus on ‘Social Exclusion’ change the policy response? • Does a focus on ‘social exclusion’ produce different policies to focus on ‘poverty’? • Are groups affected by persistent/recurrent low income different from poor in a snapshot? • Does a dynamic focus change policy to an ‘active welfare state’? • Do insights from longitudinal analysis change priorities? • What has impact been in practice since 1997?

Does a focus on ‘Social Exclusion’ change the policy response? • Does a focus on ‘social exclusion’ produce different policies to focus on ‘poverty’? • Are groups affected by persistent/recurrent low income different from poor in a snapshot? • Does a dynamic focus change policy to an ‘active welfare state’? • Do insights from longitudinal analysis change priorities? • What has impact been in practice since 1997?

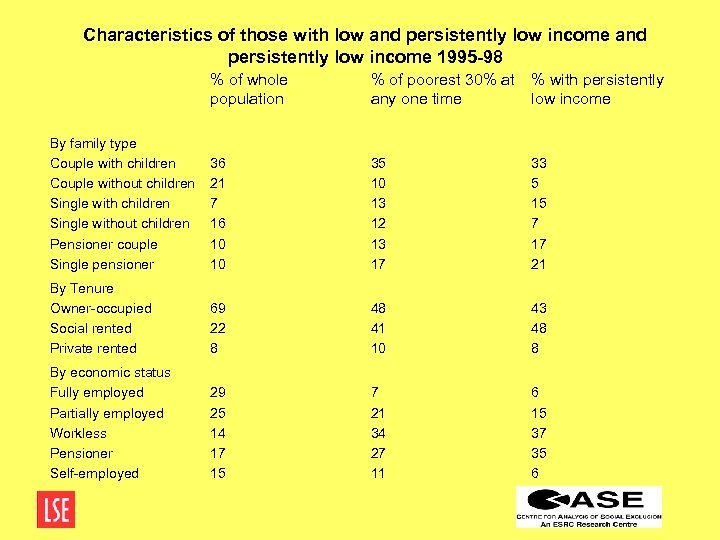

Characteristics of those with low and persistently low income 1995 -98 % of whole population % of poorest 30% at % with persistently any one time low income By family type Couple with children Couple without children Single without children Pensioner couple Single pensioner 36 21 7 16 10 10 35 10 13 12 13 17 33 5 15 7 17 21 By Tenure Owner-occupied Social rented Private rented 69 22 8 48 41 10 43 48 8 By economic status Fully employed Partially employed Workless Pensioner Self-employed 29 25 14 17 15 7 21 34 27 11 6 15 37 35 6

Characteristics of those with low and persistently low income 1995 -98 % of whole population % of poorest 30% at % with persistently any one time low income By family type Couple with children Couple without children Single without children Pensioner couple Single pensioner 36 21 7 16 10 10 35 10 13 12 13 17 33 5 15 7 17 21 By Tenure Owner-occupied Social rented Private rented 69 22 8 48 41 10 43 48 8 By economic status Fully employed Partially employed Workless Pensioner Self-employed 29 25 14 17 15 7 21 34 27 11 6 15 37 35 6

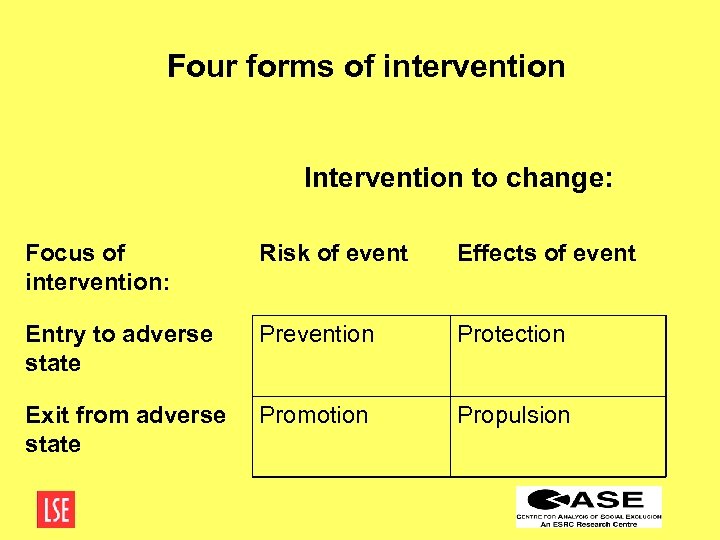

Four forms of intervention Intervention to change: Focus of intervention: Risk of event Effects of event Entry to adverse state Prevention Protection Exit from adverse state Promotion Propulsion

Four forms of intervention Intervention to change: Focus of intervention: Risk of event Effects of event Entry to adverse state Prevention Protection Exit from adverse state Promotion Propulsion

Summary: Can focussing on ‘social exclusion’ help? • Focusing on ‘social exclusion’ can draw attention to deprivation beyond cash, or at least emphasise that this should be focus • Understanding dynamics does allow differentiation of circumstances and refinement of policy. • Thinking about dynamics suggests making sure that policy does achieve all of ‘prevention, promotion, protection and propulsion’. • Can be returns in identifying key events or characteristics with long-term effects. • Emphasis on inclusion may affect choice of service delivery. • But in practice…. . ?

Summary: Can focussing on ‘social exclusion’ help? • Focusing on ‘social exclusion’ can draw attention to deprivation beyond cash, or at least emphasise that this should be focus • Understanding dynamics does allow differentiation of circumstances and refinement of policy. • Thinking about dynamics suggests making sure that policy does achieve all of ‘prevention, promotion, protection and propulsion’. • Can be returns in identifying key events or characteristics with long-term effects. • Emphasis on inclusion may affect choice of service delivery. • But in practice…. . ?

Focussing on ‘social exclusion’ in practice: Policies since 1997 • Code for ‘the underclass’, with personal responsibility for their fate, and no cause for public action? • A diversion towards ‘softer’ issues, away from more difficult – and harder – ones of material deprivation and redistribution? • Certainly no lack of policy! • ‘Poverty’ has not been ignored: Blair’s child poverty pledge

Focussing on ‘social exclusion’ in practice: Policies since 1997 • Code for ‘the underclass’, with personal responsibility for their fate, and no cause for public action? • A diversion towards ‘softer’ issues, away from more difficult – and harder – ones of material deprivation and redistribution? • Certainly no lack of policy! • ‘Poverty’ has not been ignored: Blair’s child poverty pledge

• Combination of SEU (long-term drivers) agenda and Treasury-driven (stealthy? ) redistribution • Analysis suggests that this mixture is necessary – need both short-term protection and long-term prevention • Policies have navigated with public attitudes – hence emphasis on work-based strategies for working age population. • But in contrast to US, benefits for non-working families have also risen. • The big question is whether the scale of action is enough?

• Combination of SEU (long-term drivers) agenda and Treasury-driven (stealthy? ) redistribution • Analysis suggests that this mixture is necessary – need both short-term protection and long-term prevention • Policies have navigated with public attitudes – hence emphasis on work-based strategies for working age population. • But in contrast to US, benefits for non-working families have also risen. • The big question is whether the scale of action is enough?

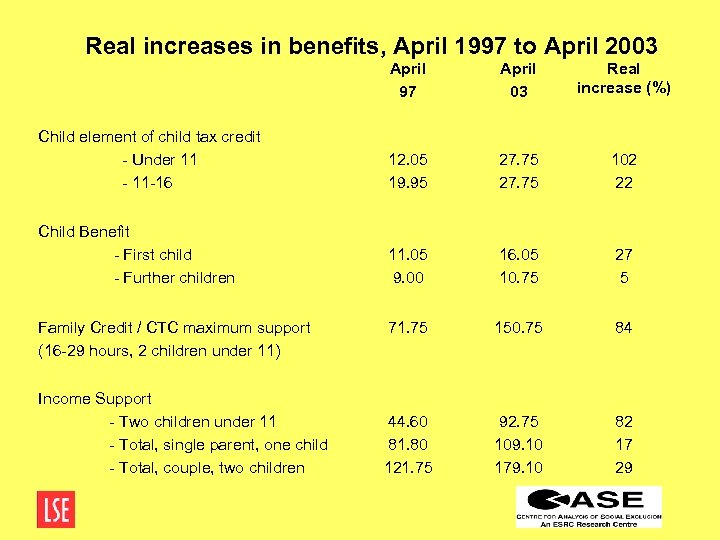

Real increases in benefits, April 1997 to April 2003 April 97 April 03 Real increase (%) Child element of child tax credit - Under 11 - 11 -16 12. 05 19. 95 27. 75 102 22 Child Benefit - First child - Further children 11. 05 9. 00 16. 05 10. 75 27 5 71. 75 150. 75 84 44. 60 81. 80 121. 75 92. 75 109. 10 179. 10 82 17 29 Family Credit / CTC maximum support (16 -29 hours, 2 children under 11) Income Support - Two children under 11 - Total, single parent, one child - Total, couple, two children

Real increases in benefits, April 1997 to April 2003 April 97 April 03 Real increase (%) Child element of child tax credit - Under 11 - 11 -16 12. 05 19. 95 27. 75 102 22 Child Benefit - First child - Further children 11. 05 9. 00 16. 05 10. 75 27 5 71. 75 150. 75 84 44. 60 81. 80 121. 75 92. 75 109. 10 179. 10 82 17 29 Family Credit / CTC maximum support (16 -29 hours, 2 children under 11) Income Support - Two children under 11 - Total, single parent, one child - Total, couple, two children

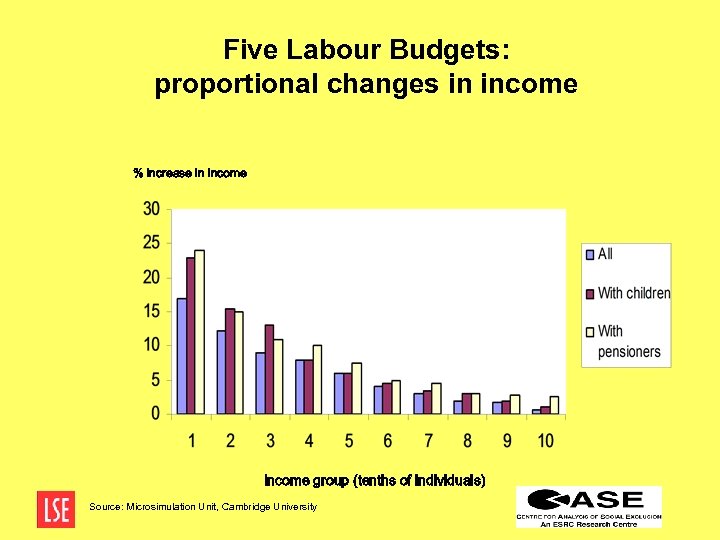

Five Labour Budgets: proportional changes in income % increase in income Income group (tenths of individuals) Source: Microsimulation Unit, Cambridge University

Five Labour Budgets: proportional changes in income % increase in income Income group (tenths of individuals) Source: Microsimulation Unit, Cambridge University

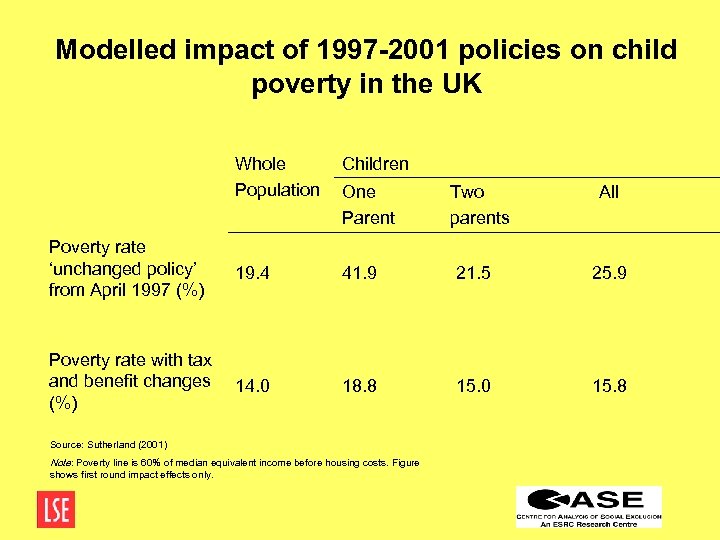

Modelled impact of 1997 -2001 policies on child poverty in the UK Whole Population Children Poverty rate ‘unchanged policy’ from April 1997 (%) 19. 4 41. 9 21. 5 25. 9 Poverty rate with tax and benefit changes (%) 14. 0 18. 8 15. 0 15. 8 One Two All Parent parents Source: Sutherland (2001) Note: Poverty line is 60% of median equivalent income before housing costs. Figure shows first round impact effects only.

Modelled impact of 1997 -2001 policies on child poverty in the UK Whole Population Children Poverty rate ‘unchanged policy’ from April 1997 (%) 19. 4 41. 9 21. 5 25. 9 Poverty rate with tax and benefit changes (%) 14. 0 18. 8 15. 0 15. 8 One Two All Parent parents Source: Sutherland (2001) Note: Poverty line is 60% of median equivalent income before housing costs. Figure shows first round impact effects only.

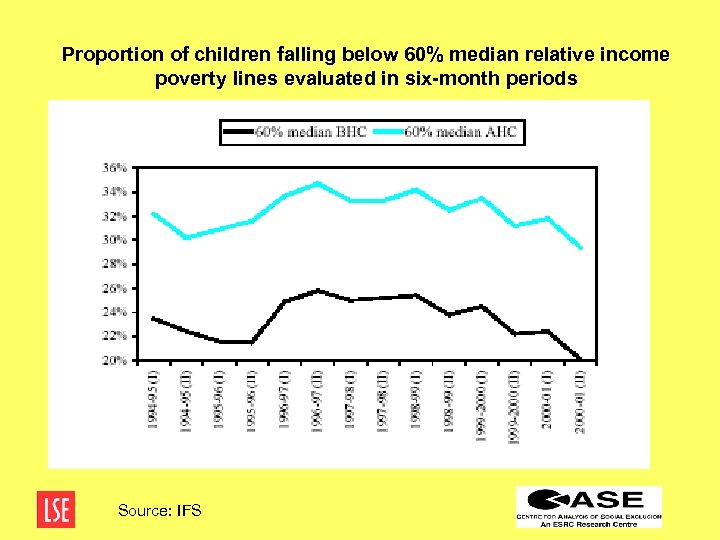

Proportion of children falling below 60% median relative income poverty lines evaluated in six-month periods Source: IFS

Proportion of children falling below 60% median relative income poverty lines evaluated in six-month periods Source: IFS

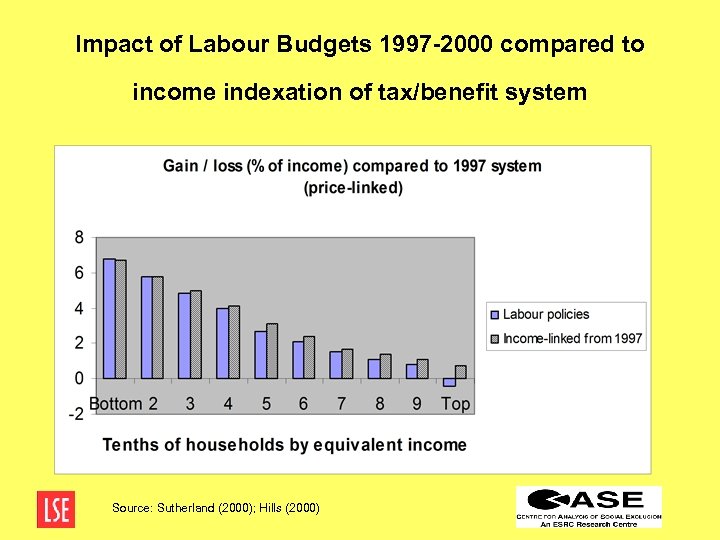

Impact of Labour Budgets 1997 -2000 compared to income indexation of tax/benefit system Source: Sutherland (2000); Hills (2000)

Impact of Labour Budgets 1997 -2000 compared to income indexation of tax/benefit system Source: Sutherland (2000); Hills (2000)

Four possible conclusions • There’s not very much social exclusion about • There’s lots of social exclusion about • Talking about ‘social exclusion’ makes no difference to policy • Talking about social exclusion can make – and has made – a difference to policy

Four possible conclusions • There’s not very much social exclusion about • There’s lots of social exclusion about • Talking about ‘social exclusion’ makes no difference to policy • Talking about social exclusion can make – and has made – a difference to policy