b206fe8aedfc95b66f2d8e9b06295adc.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 51

Incorporating Domain. Specific Information into the Compilation Process Samuel Z. Guyer Supervisor: Calvin Lin April 14, 2003 1

Incorporating Domain. Specific Information into the Compilation Process Samuel Z. Guyer Supervisor: Calvin Lin April 14, 2003 1

Motivation Two different views of software: l Compiler’s view l l l Abstractions: numbers, pointers, loops Operators: +, -, *, ->, [] Programmer’s view l l Abstractions: files, matrices, locks, graphics Operators: read, factor, lock, draw This discrepancy is a problem. . . 2

Motivation Two different views of software: l Compiler’s view l l l Abstractions: numbers, pointers, loops Operators: +, -, *, ->, [] Programmer’s view l l Abstractions: files, matrices, locks, graphics Operators: read, factor, lock, draw This discrepancy is a problem. . . 2

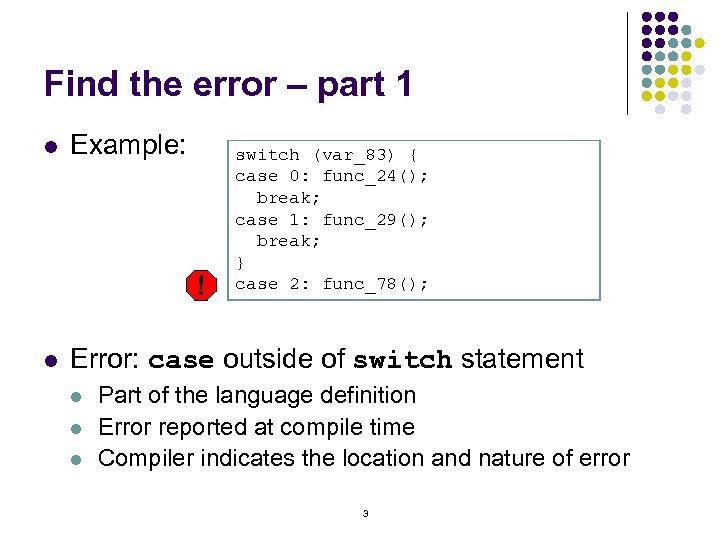

Find the error – part 1 l Example: ! l switch (var_83) { case 0: func_24(); break; case 1: func_29(); break; } case 2: func_78(); Error: case outside of switch statement l l l Part of the language definition Error reported at compile time Compiler indicates the location and nature of error 3

Find the error – part 1 l Example: ! l switch (var_83) { case 0: func_24(); break; case 1: func_29(); break; } case 2: func_78(); Error: case outside of switch statement l l l Part of the language definition Error reported at compile time Compiler indicates the location and nature of error 3

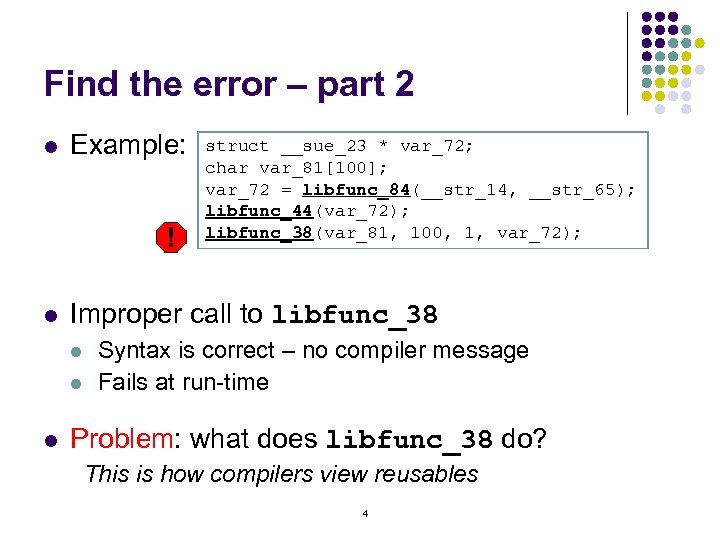

Find the error – part 2 l Example: ! l Improper call to libfunc_38 l l l struct __sue_23 * var_72; char var_81[100]; var_72 = libfunc_84(__str_14, __str_65); libfunc_44(var_72); libfunc_38(var_81, 100, 1, var_72); Syntax is correct – no compiler message Fails at run-time Problem: what does libfunc_38 do? This is how compilers view reusables 4

Find the error – part 2 l Example: ! l Improper call to libfunc_38 l l l struct __sue_23 * var_72; char var_81[100]; var_72 = libfunc_84(__str_14, __str_65); libfunc_44(var_72); libfunc_38(var_81, 100, 1, var_72); Syntax is correct – no compiler message Fails at run-time Problem: what does libfunc_38 do? This is how compilers view reusables 4

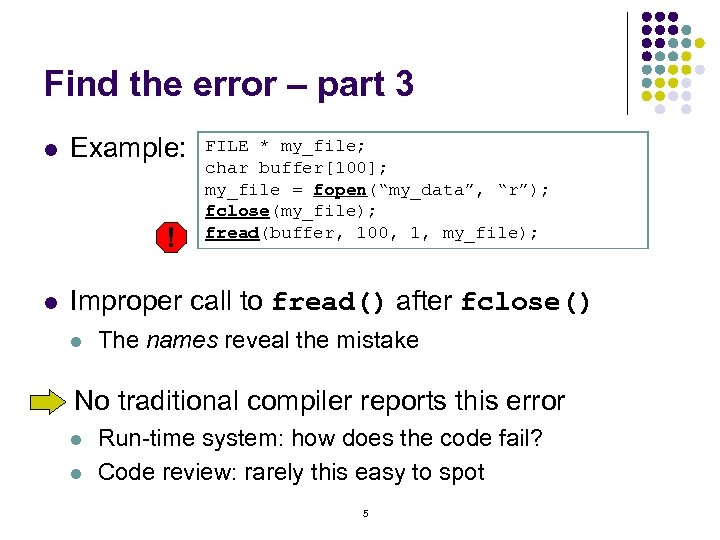

Find the error – part 3 l Example: ! l FILE * my_file; char buffer[100]; my_file = fopen(“my_data”, “r”); fclose(my_file); fread(buffer, 100, 1, my_file); Improper call to fread() after fclose() l The names reveal the mistake No traditional compiler reports this error l l Run-time system: how does the code fail? Code review: rarely this easy to spot 5

Find the error – part 3 l Example: ! l FILE * my_file; char buffer[100]; my_file = fopen(“my_data”, “r”); fclose(my_file); fread(buffer, 100, 1, my_file); Improper call to fread() after fclose() l The names reveal the mistake No traditional compiler reports this error l l Run-time system: how does the code fail? Code review: rarely this easy to spot 5

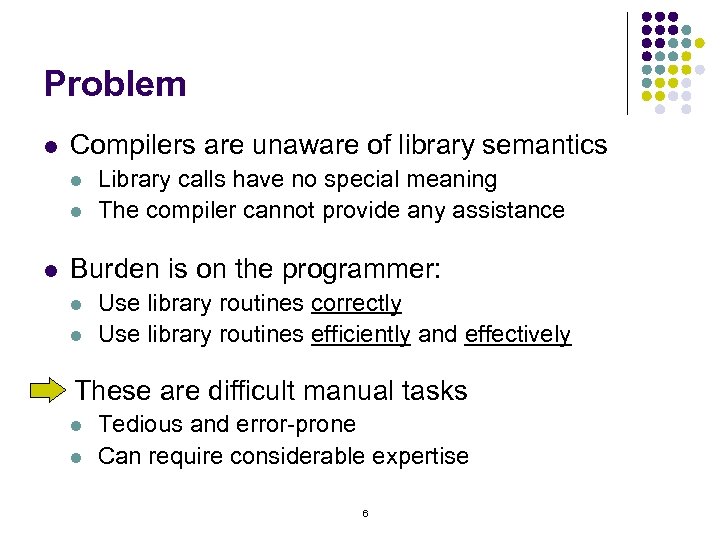

Problem l Compilers are unaware of library semantics l l l Library calls have no special meaning The compiler cannot provide any assistance Burden is on the programmer: l l Use library routines correctly Use library routines efficiently and effectively These are difficult manual tasks l l Tedious and error-prone Can require considerable expertise 6

Problem l Compilers are unaware of library semantics l l l Library calls have no special meaning The compiler cannot provide any assistance Burden is on the programmer: l l Use library routines correctly Use library routines efficiently and effectively These are difficult manual tasks l l Tedious and error-prone Can require considerable expertise 6

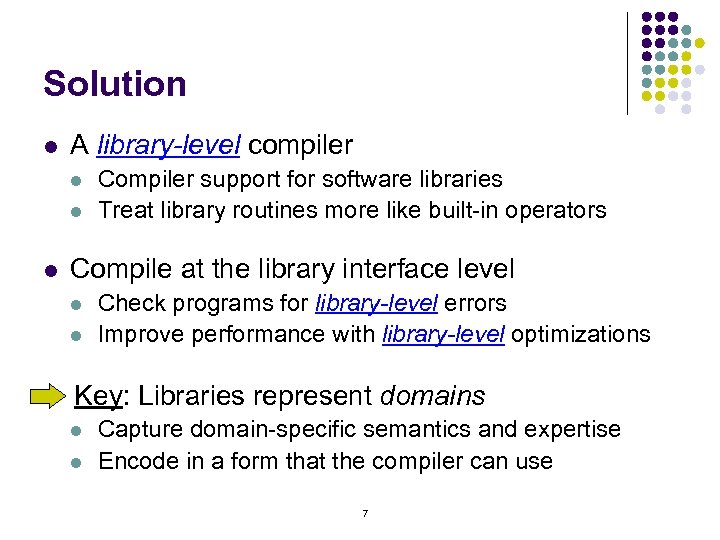

Solution l A library-level compiler l l l Compiler support for software libraries Treat library routines more like built-in operators Compile at the library interface level l l Check programs for library-level errors Improve performance with library-level optimizations Key: Libraries represent domains l l Capture domain-specific semantics and expertise Encode in a form that the compiler can use 7

Solution l A library-level compiler l l l Compiler support for software libraries Treat library routines more like built-in operators Compile at the library interface level l l Check programs for library-level errors Improve performance with library-level optimizations Key: Libraries represent domains l l Capture domain-specific semantics and expertise Encode in a form that the compiler can use 7

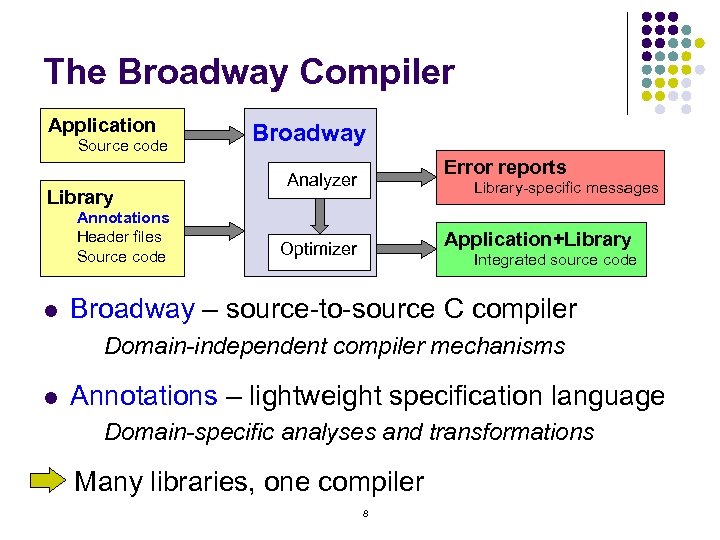

The Broadway Compiler Application Source code Library Annotations Header files Source code l Broadway Error reports Analyzer Library-specific messages Application+Library Optimizer Integrated source code Broadway – source-to-source C compiler Domain-independent compiler mechanisms l Annotations – lightweight specification language Domain-specific analyses and transformations Many libraries, one compiler 8

The Broadway Compiler Application Source code Library Annotations Header files Source code l Broadway Error reports Analyzer Library-specific messages Application+Library Optimizer Integrated source code Broadway – source-to-source C compiler Domain-independent compiler mechanisms l Annotations – lightweight specification language Domain-specific analyses and transformations Many libraries, one compiler 8

Benefits l Improves capabilities of the compiler l l l Works with existing systems l l l Adds many new error checks and optimizations Qualitatively different Domain-specific compilation without recoding For us: more thorough and convincing validation Improve productivity l l Less time spent on manual tasks All users benefit from one set of annotations 9

Benefits l Improves capabilities of the compiler l l l Works with existing systems l l l Adds many new error checks and optimizations Qualitatively different Domain-specific compilation without recoding For us: more thorough and convincing validation Improve productivity l l Less time spent on manual tasks All users benefit from one set of annotations 9

Outline l Motivation The Broadway Compiler l Recent work on scalable program analysis l l l l Problem: Error checking demands powerful analysis Solution: Client-driven analysis algorithm Example: Detecting security vulnerabilities Contributions Related work Conclusions and future work 10

Outline l Motivation The Broadway Compiler l Recent work on scalable program analysis l l l l Problem: Error checking demands powerful analysis Solution: Client-driven analysis algorithm Example: Detecting security vulnerabilities Contributions Related work Conclusions and future work 10

Security vulnerabilities l How does remote hacking work? l l l Most are not direct attacks (e. g. , cracking passwords) Idea: trick a program into unintended behavior Automated vulnerability detection: l l How do we define “intended”? Difficult to formalize and check application logic Libraries control all critical system services l l Communication, file access, process control Analyze routines to approximate vulnerability 11

Security vulnerabilities l How does remote hacking work? l l l Most are not direct attacks (e. g. , cracking passwords) Idea: trick a program into unintended behavior Automated vulnerability detection: l l How do we define “intended”? Difficult to formalize and check application logic Libraries control all critical system services l l Communication, file access, process control Analyze routines to approximate vulnerability 11

![Remote access vulnerability l Example: ! l int sock; char buffer[100]; sock = socket(AF_INET, Remote access vulnerability l Example: ! l int sock; char buffer[100]; sock = socket(AF_INET,](https://present5.com/presentation/b206fe8aedfc95b66f2d8e9b06295adc/image-12.jpg) Remote access vulnerability l Example: ! l int sock; char buffer[100]; sock = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0); read(sock, buffer, 100); execl(buffer); Vulnerability: executes any remote command l l l What if this program runs as root? Clearly domain-specific: sockets, processes, etc. Requirement: Data from an Internet socket should not specify a program to execute l Why is detecting this vulnerability hard? 12

Remote access vulnerability l Example: ! l int sock; char buffer[100]; sock = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0); read(sock, buffer, 100); execl(buffer); Vulnerability: executes any remote command l l l What if this program runs as root? Clearly domain-specific: sockets, processes, etc. Requirement: Data from an Internet socket should not specify a program to execute l Why is detecting this vulnerability hard? 12

![Challenge 1: Pointers l Example: ! l int sock; char buffer[100]; char * ref Challenge 1: Pointers l Example: ! l int sock; char buffer[100]; char * ref](https://present5.com/presentation/b206fe8aedfc95b66f2d8e9b06295adc/image-13.jpg) Challenge 1: Pointers l Example: ! l int sock; char buffer[100]; char * ref = buffer; sock = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0); read(sock, buffer, 100); execl(ref); Still contains a vulnerability l l Only one buffer Variables buffer and ref are aliases We need an accurate model of memory 13

Challenge 1: Pointers l Example: ! l int sock; char buffer[100]; char * ref = buffer; sock = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0); read(sock, buffer, 100); execl(ref); Still contains a vulnerability l l Only one buffer Variables buffer and ref are aliases We need an accurate model of memory 13

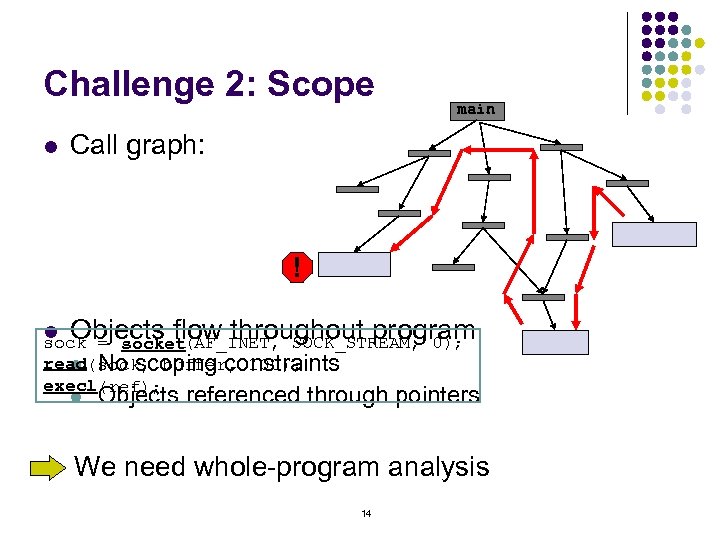

Challenge 2: Scope l main Call graph: ! l Objects flow throughout program sock = (AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0); socket read(sock, buffer, 100); l No scoping constraints execl(ref); l Objects referenced through pointers We need whole-program analysis 14

Challenge 2: Scope l main Call graph: ! l Objects flow throughout program sock = (AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0); socket read(sock, buffer, 100); l No scoping constraints execl(ref); l Objects referenced through pointers We need whole-program analysis 14

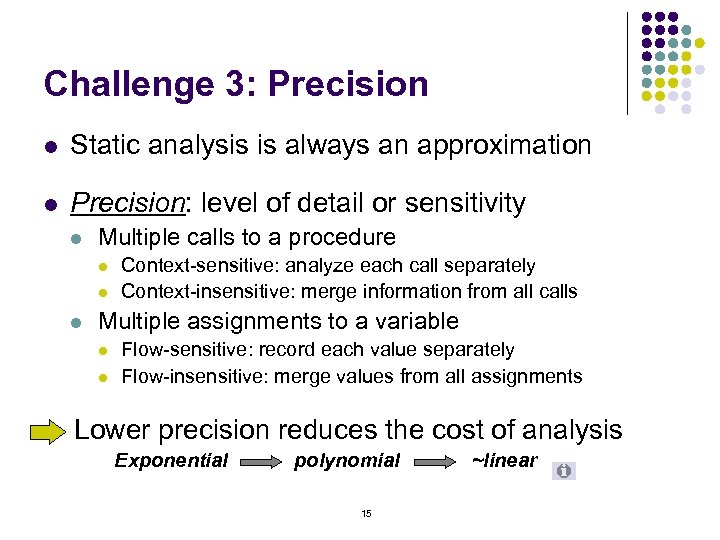

Challenge 3: Precision l Static analysis is always an approximation l Precision: level of detail or sensitivity l Multiple calls to a procedure l l l Context-sensitive: analyze each call separately Context-insensitive: merge information from all calls Multiple assignments to a variable l l Flow-sensitive: record each value separately Flow-insensitive: merge values from all assignments Lower precision reduces the cost of analysis Exponential polynomial 15 ~linear

Challenge 3: Precision l Static analysis is always an approximation l Precision: level of detail or sensitivity l Multiple calls to a procedure l l l Context-sensitive: analyze each call separately Context-insensitive: merge information from all calls Multiple assignments to a variable l l Flow-sensitive: record each value separately Flow-insensitive: merge values from all assignments Lower precision reduces the cost of analysis Exponential polynomial 15 ~linear

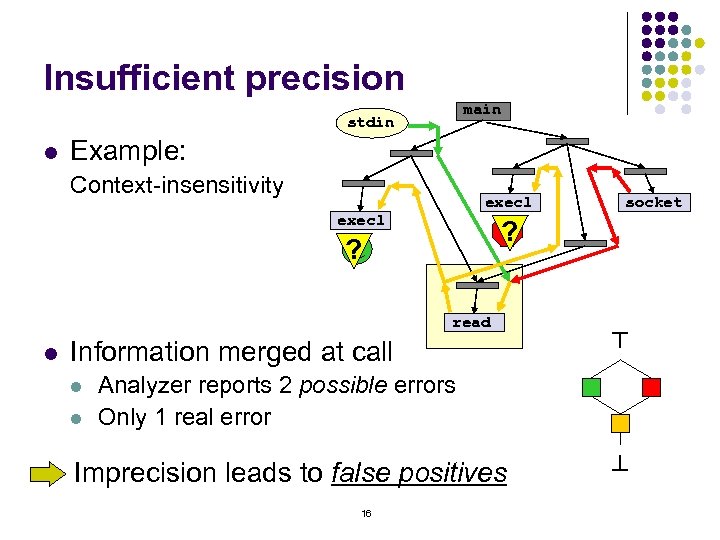

Insufficient precision main stdin Example: Context-insensitivity execl ? ! ? read l Information merged at call l l socket ^ l Analyzer reports 2 possible errors Only 1 real error Imprecision leads to false positives 16 ^

Insufficient precision main stdin Example: Context-insensitivity execl ? ! ? read l Information merged at call l l socket ^ l Analyzer reports 2 possible errors Only 1 real error Imprecision leads to false positives 16 ^

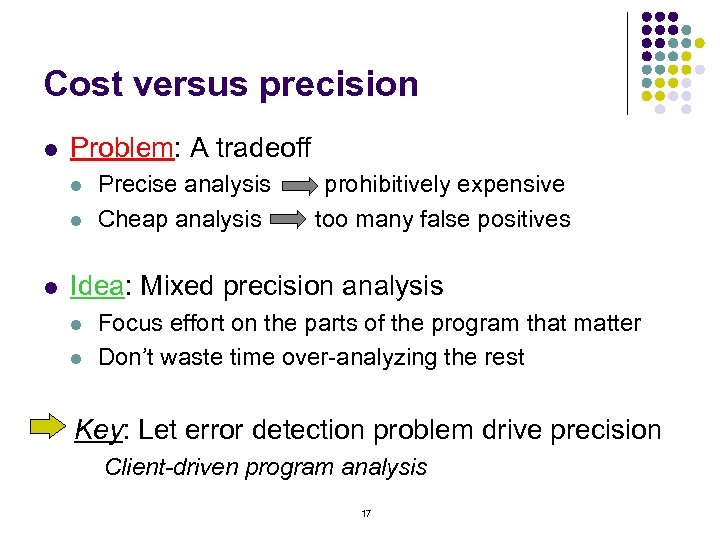

Cost versus precision l Problem: A tradeoff l l l Precise analysis Cheap analysis prohibitively expensive too many false positives Idea: Mixed precision analysis l l Focus effort on the parts of the program that matter Don’t waste time over-analyzing the rest Key: Let error detection problem drive precision Client-driven program analysis 17

Cost versus precision l Problem: A tradeoff l l l Precise analysis Cheap analysis prohibitively expensive too many false positives Idea: Mixed precision analysis l l Focus effort on the parts of the program that matter Don’t waste time over-analyzing the rest Key: Let error detection problem drive precision Client-driven program analysis 17

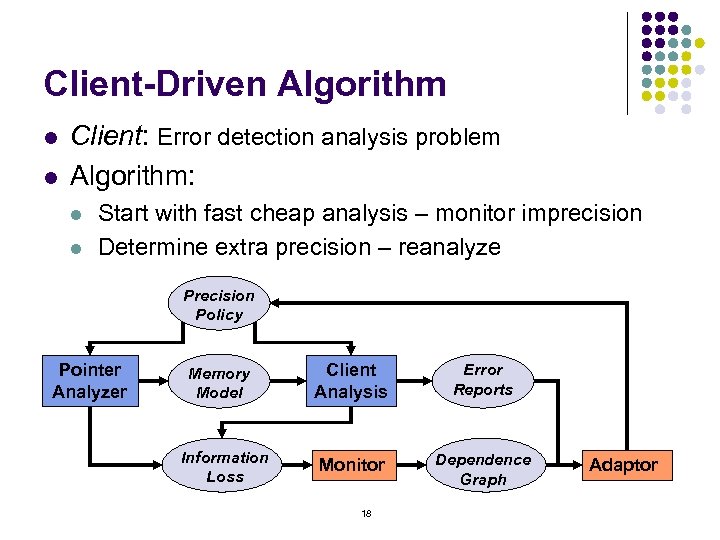

Client-Driven Algorithm l l Client: Error detection analysis problem Algorithm: l l Start with fast cheap analysis – monitor imprecision Determine extra precision – reanalyze Precision Policy Pointer Analyzer Memory Model Information Loss Client Analysis Error Reports Monitor Dependence Graph 18 Adaptor

Client-Driven Algorithm l l Client: Error detection analysis problem Algorithm: l l Start with fast cheap analysis – monitor imprecision Determine extra precision – reanalyze Precision Policy Pointer Analyzer Memory Model Information Loss Client Analysis Error Reports Monitor Dependence Graph 18 Adaptor

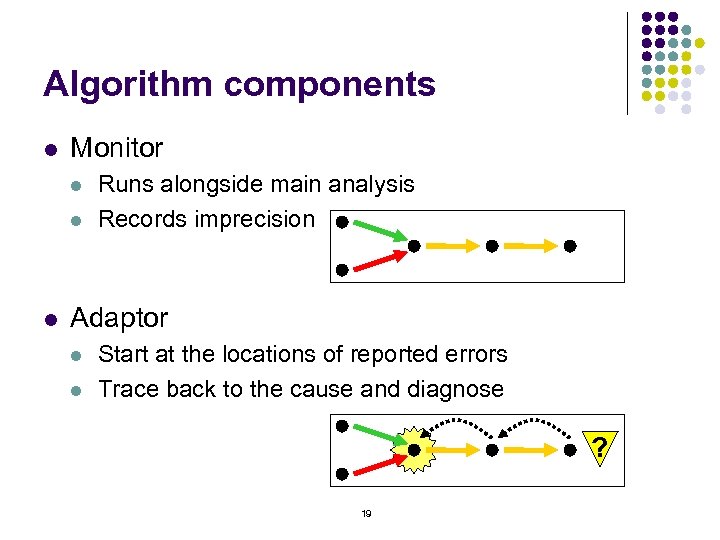

Algorithm components l Monitor l l l Runs alongside main analysis Records imprecision Adaptor l l Start at the locations of reported errors Trace back to the cause and diagnose ? 19

Algorithm components l Monitor l l l Runs alongside main analysis Records imprecision Adaptor l l Start at the locations of reported errors Trace back to the cause and diagnose ? 19

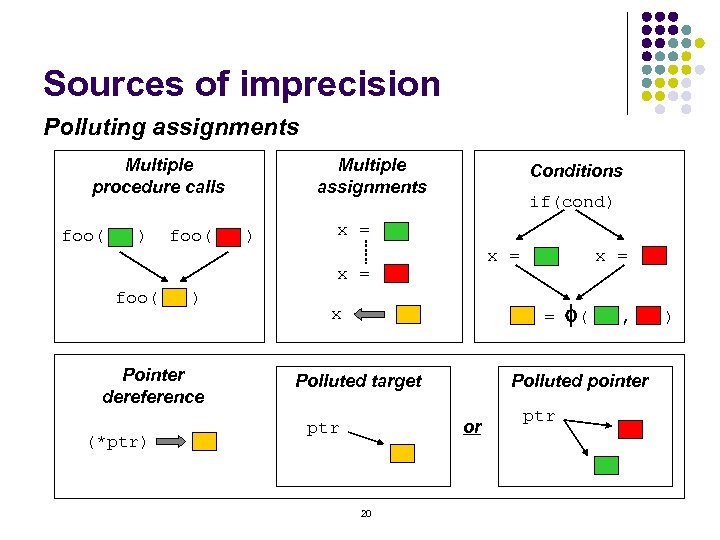

Sources of imprecision Polluting assignments Multiple procedure calls foo( ) Multiple assignments Conditions if(cond) x = foo( ) Pointer dereference (*ptr) = f( , ) x Polluted target Polluted pointer or ptr 20 x = ptr

Sources of imprecision Polluting assignments Multiple procedure calls foo( ) Multiple assignments Conditions if(cond) x = foo( ) Pointer dereference (*ptr) = f( , ) x Polluted target Polluted pointer or ptr 20 x = ptr

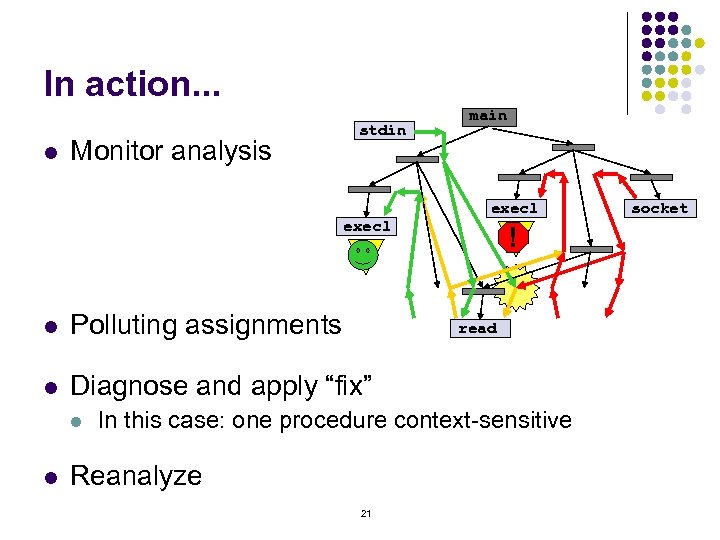

In action. . . l Monitor analysis stdin execl main execl ? ! ? l Polluting assignments l Diagnose and apply “fix” l l read In this case: one procedure context-sensitive Reanalyze 21 socket

In action. . . l Monitor analysis stdin execl main execl ? ! ? l Polluting assignments l Diagnose and apply “fix” l l read In this case: one procedure context-sensitive Reanalyze 21 socket

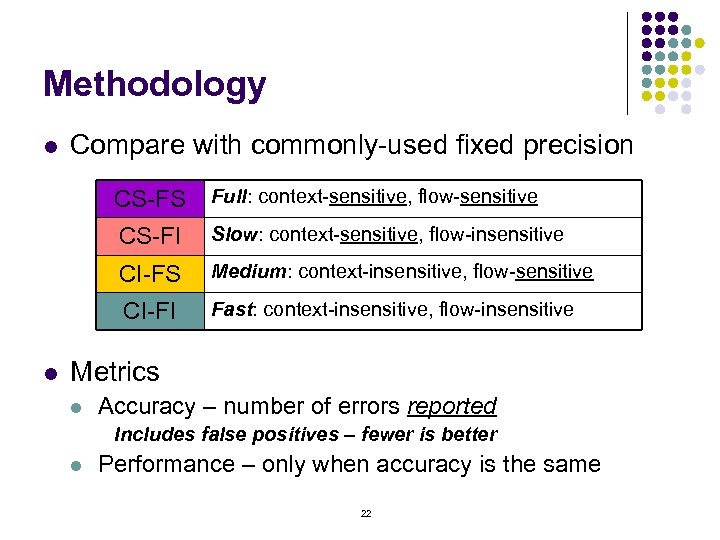

Methodology l Compare with commonly-used fixed precision CS-FS CS-FI Slow: context-sensitive, flow-insensitive CI-FS Medium: context-insensitive, flow-sensitive CI-FI l Full: context-sensitive, flow-sensitive Fast: context-insensitive, flow-insensitive Metrics l Accuracy – number of errors reported Includes false positives – fewer is better l Performance – only when accuracy is the same 22

Methodology l Compare with commonly-used fixed precision CS-FS CS-FI Slow: context-sensitive, flow-insensitive CI-FS Medium: context-insensitive, flow-sensitive CI-FI l Full: context-sensitive, flow-sensitive Fast: context-insensitive, flow-insensitive Metrics l Accuracy – number of errors reported Includes false positives – fewer is better l Performance – only when accuracy is the same 22

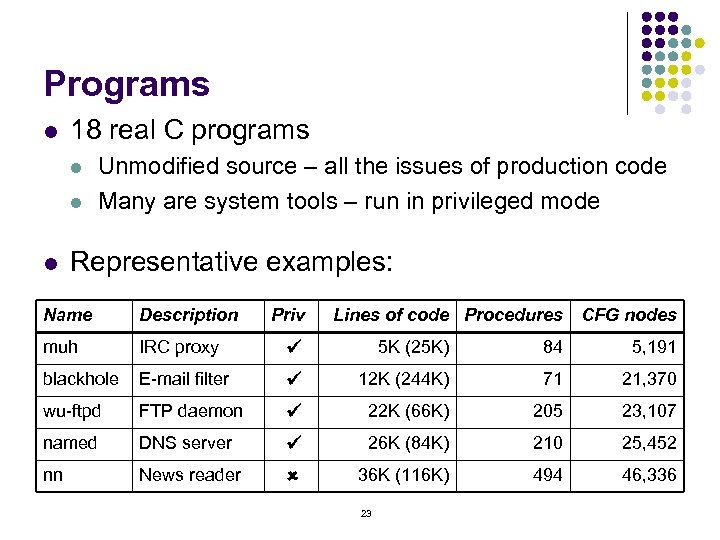

Programs l 18 real C programs l l l Unmodified source – all the issues of production code Many are system tools – run in privileged mode Representative examples: Name Description Priv Lines of code Procedures muh IRC proxy ü 5 K (25 K) 84 5, 191 blackhole E-mail filter ü 12 K (244 K) 71 21, 370 wu-ftpd FTP daemon ü 22 K (66 K) 205 23, 107 named DNS server ü 26 K (84 K) 210 25, 452 nn News reader û 36 K (116 K) 494 46, 336 23 CFG nodes

Programs l 18 real C programs l l l Unmodified source – all the issues of production code Many are system tools – run in privileged mode Representative examples: Name Description Priv Lines of code Procedures muh IRC proxy ü 5 K (25 K) 84 5, 191 blackhole E-mail filter ü 12 K (244 K) 71 21, 370 wu-ftpd FTP daemon ü 22 K (66 K) 205 23, 107 named DNS server ü 26 K (84 K) 210 25, 452 nn News reader û 36 K (116 K) 494 46, 336 23 CFG nodes

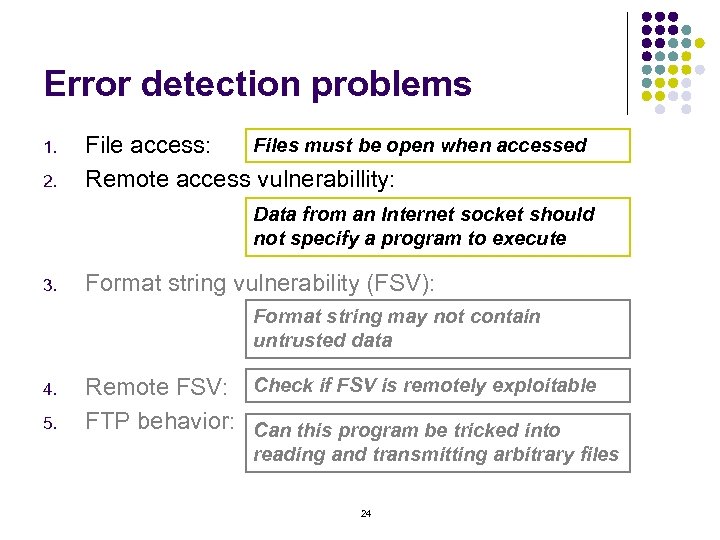

Error detection problems 1. 2. Files must be open when accessed File access: Remote access vulnerabillity: Data from an Internet socket should not specify a program to execute 3. Format string vulnerability (FSV): Format string may not contain untrusted data 4. 5. Remote FSV: Check if FSV is remotely exploitable FTP behavior: Can this program be tricked into reading and transmitting arbitrary files 24

Error detection problems 1. 2. Files must be open when accessed File access: Remote access vulnerabillity: Data from an Internet socket should not specify a program to execute 3. Format string vulnerability (FSV): Format string may not contain untrusted data 4. 5. Remote FSV: Check if FSV is remotely exploitable FTP behavior: Can this program be tricked into reading and transmitting arbitrary files 24

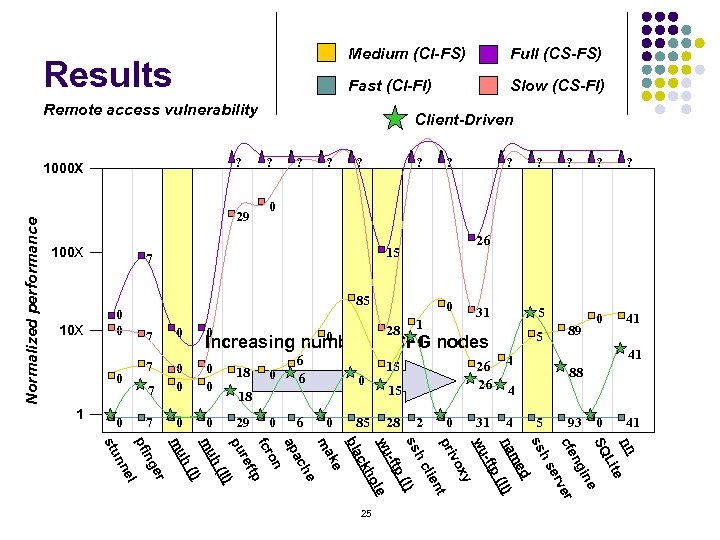

Medium (CI-FS) Fast (CI-FI) Results Full (CS-FS) Slow (CS-FI) Remote access vulnerability ? 29 100 X 10 X ? ? 0 7 0 0 Increasing number 7 0 0 29 mu mu 0 6 6 0 28 1 1 of CFG 0 18 0 6 0 85 ? ? 5 5 nodes 26 26 15 15 28 31 2 0 0 41 4 31 89 88 4 5 93 0 41 nn e Lit SQ ine ng cfe er erv hs ss d me na (II) -ftp wu xy vo pri nt lie hc ss (I) -ftp wu le ho ck bla ke ma he ac ap on fcr tp ref pu II) h( I) er el nn h( 0 ng 0 0 18 7 0 0 pfi 7 ? 26 85 0 0 ? 0 7 0 1 ? 15 stu Normalized performance 1000 X Client-Driven 25

Medium (CI-FS) Fast (CI-FI) Results Full (CS-FS) Slow (CS-FI) Remote access vulnerability ? 29 100 X 10 X ? ? 0 7 0 0 Increasing number 7 0 0 29 mu mu 0 6 6 0 28 1 1 of CFG 0 18 0 6 0 85 ? ? 5 5 nodes 26 26 15 15 28 31 2 0 0 41 4 31 89 88 4 5 93 0 41 nn e Lit SQ ine ng cfe er erv hs ss d me na (II) -ftp wu xy vo pri nt lie hc ss (I) -ftp wu le ho ck bla ke ma he ac ap on fcr tp ref pu II) h( I) er el nn h( 0 ng 0 0 18 7 0 0 pfi 7 ? 26 85 0 0 ? 0 7 0 1 ? 15 stu Normalized performance 1000 X Client-Driven 25

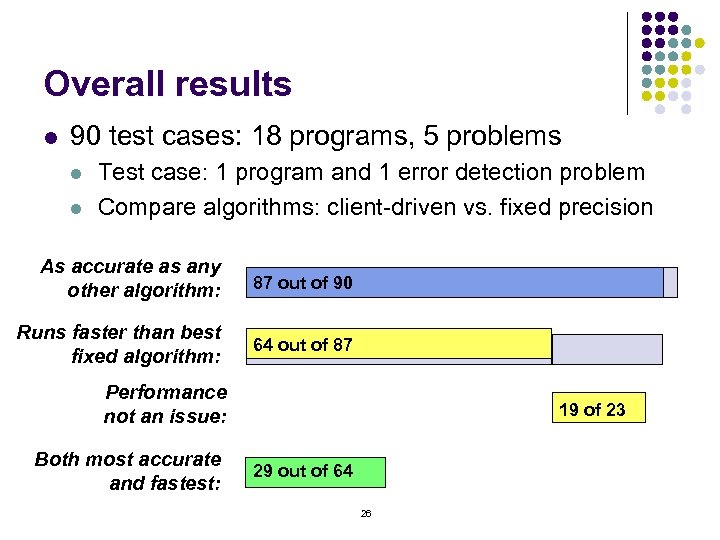

Overall results l 90 test cases: 18 programs, 5 problems l l Test case: 1 program and 1 error detection problem Compare algorithms: client-driven vs. fixed precision As accurate as any other algorithm: 87 out of 90 Runs faster than best fixed algorithm: 64 out of 87 Performance not an issue: Both most accurate and fastest: 19 of 23 29 out of 64 26

Overall results l 90 test cases: 18 programs, 5 problems l l Test case: 1 program and 1 error detection problem Compare algorithms: client-driven vs. fixed precision As accurate as any other algorithm: 87 out of 90 Runs faster than best fixed algorithm: 64 out of 87 Performance not an issue: Both most accurate and fastest: 19 of 23 29 out of 64 26

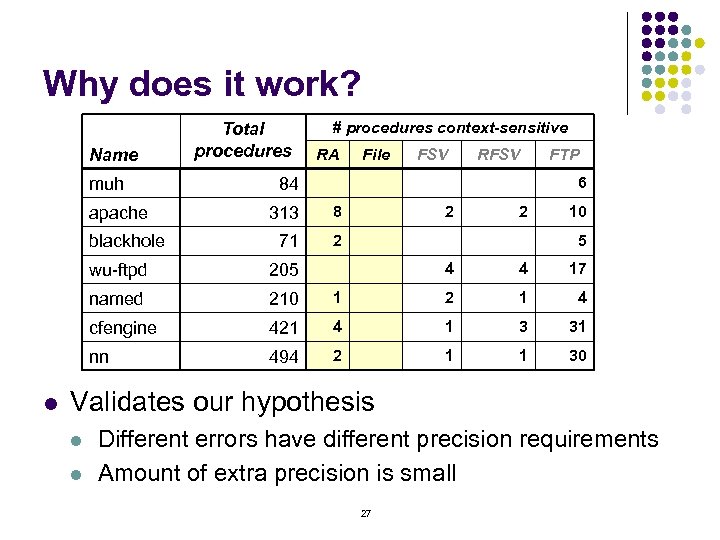

Why does it work? Name muh apache blackhole Total procedures RA File FSV RFSV FTP 6 84 313 8 71 2 2 2 10 5 4 4 17 1 2 1 4 421 4 1 3 31 494 2 1 1 30 wu-ftpd 205 named 210 cfengine nn l # procedures context-sensitive Validates our hypothesis l l Different errors have different precision requirements Amount of extra precision is small 27

Why does it work? Name muh apache blackhole Total procedures RA File FSV RFSV FTP 6 84 313 8 71 2 2 2 10 5 4 4 17 1 2 1 4 421 4 1 3 31 494 2 1 1 30 wu-ftpd 205 named 210 cfengine nn l # procedures context-sensitive Validates our hypothesis l l Different errors have different precision requirements Amount of extra precision is small 27

Outline l Motivation The Broadway Compiler l Recent work on scalable program analysis l l l l Problem: Error checking demands powerful analysis Solution: Client-driven analysis algorithm Example: Detecting security vulnerabilities Contributions Related work Conclusions and future work 28

Outline l Motivation The Broadway Compiler l Recent work on scalable program analysis l l l l Problem: Error checking demands powerful analysis Solution: Client-driven analysis algorithm Example: Detecting security vulnerabilities Contributions Related work Conclusions and future work 28

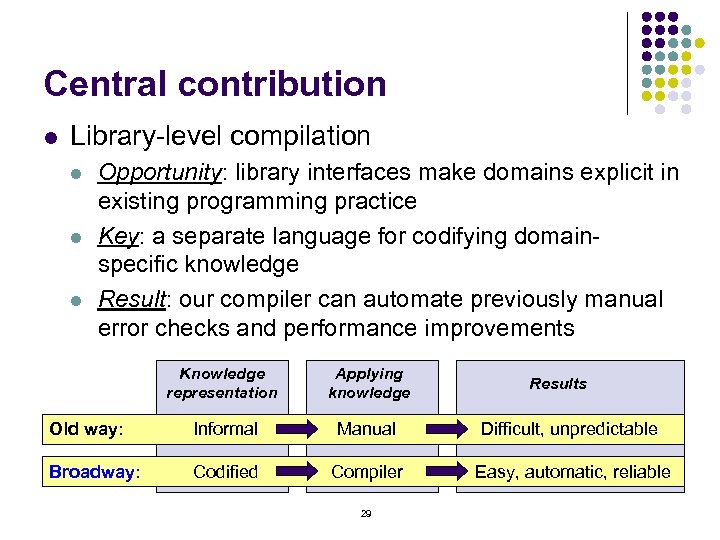

Central contribution l Library-level compilation l l l Opportunity: library interfaces make domains explicit in existing programming practice Key: a separate language for codifying domainspecific knowledge Result: our compiler can automate previously manual error checks and performance improvements Knowledge representation Applying knowledge Old way: Informal Manual Difficult, unpredictable Broadway: Codified Compiler Easy, automatic, reliable 29 Results

Central contribution l Library-level compilation l l l Opportunity: library interfaces make domains explicit in existing programming practice Key: a separate language for codifying domainspecific knowledge Result: our compiler can automate previously manual error checks and performance improvements Knowledge representation Applying knowledge Old way: Informal Manual Difficult, unpredictable Broadway: Codified Compiler Easy, automatic, reliable 29 Results

![Specific contributions l Broadway compiler implementation l l Client-driven pointer analysis algorithm [SAS’ 03] Specific contributions l Broadway compiler implementation l l Client-driven pointer analysis algorithm [SAS’ 03]](https://present5.com/presentation/b206fe8aedfc95b66f2d8e9b06295adc/image-30.jpg) Specific contributions l Broadway compiler implementation l l Client-driven pointer analysis algorithm [SAS’ 03] l l No false positives format string vulnerability Library-level optimization experiments [LCPC’ 00] l l Precise and scalable whole-program analysis Library-level error checking experiments [CSTR’ 01] l l Working system (43 K C-Breeze, 23 K pointers, 30 K Broadway) Solid improvements for PLAPACK programs Annotation language [DSL’ 99] l Balance expressive power and ease of use 30

Specific contributions l Broadway compiler implementation l l Client-driven pointer analysis algorithm [SAS’ 03] l l No false positives format string vulnerability Library-level optimization experiments [LCPC’ 00] l l Precise and scalable whole-program analysis Library-level error checking experiments [CSTR’ 01] l l Working system (43 K C-Breeze, 23 K pointers, 30 K Broadway) Solid improvements for PLAPACK programs Annotation language [DSL’ 99] l Balance expressive power and ease of use 30

Related work l Configurable compilers l l Active libraries l l l Previous work focusing on specific domains Few complete, working systems Error detection l l Power versus usability – who is the user? Partial program verification – paucity of results Scalable pointer analysis l l Many studies of cost/precision tradeoff Few mixed-precision approaches 31

Related work l Configurable compilers l l Active libraries l l l Previous work focusing on specific domains Few complete, working systems Error detection l l Power versus usability – who is the user? Partial program verification – paucity of results Scalable pointer analysis l l Many studies of cost/precision tradeoff Few mixed-precision approaches 31

Future work l Language l l Optimization l l We have only scratched the surface Error checking l l l More analysis capabilities Resource leaks Path sensitivity – conditional transfer functions Scalable analysis l l Start with cheaper analysis – unification-based Refine to more expensive analysis – shape analysis 32

Future work l Language l l Optimization l l We have only scratched the surface Error checking l l l More analysis capabilities Resource leaks Path sensitivity – conditional transfer functions Scalable analysis l l Start with cheaper analysis – unification-based Refine to more expensive analysis – shape analysis 32

Thank You 33

Thank You 33

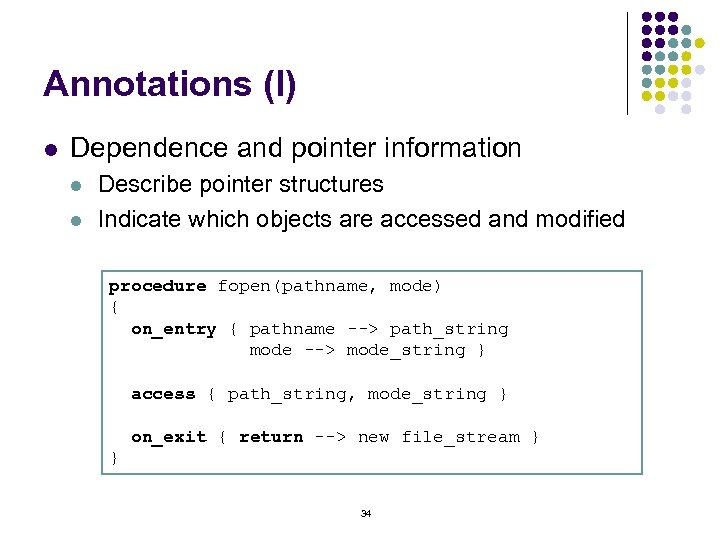

Annotations (I) l Dependence and pointer information l l Describe pointer structures Indicate which objects are accessed and modified procedure fopen(pathname, mode) { on_entry { pathname --> path_string mode --> mode_string } access { path_string, mode_string } on_exit { return --> new file_stream } } 34

Annotations (I) l Dependence and pointer information l l Describe pointer structures Indicate which objects are accessed and modified procedure fopen(pathname, mode) { on_entry { pathname --> path_string mode --> mode_string } access { path_string, mode_string } on_exit { return --> new file_stream } } 34

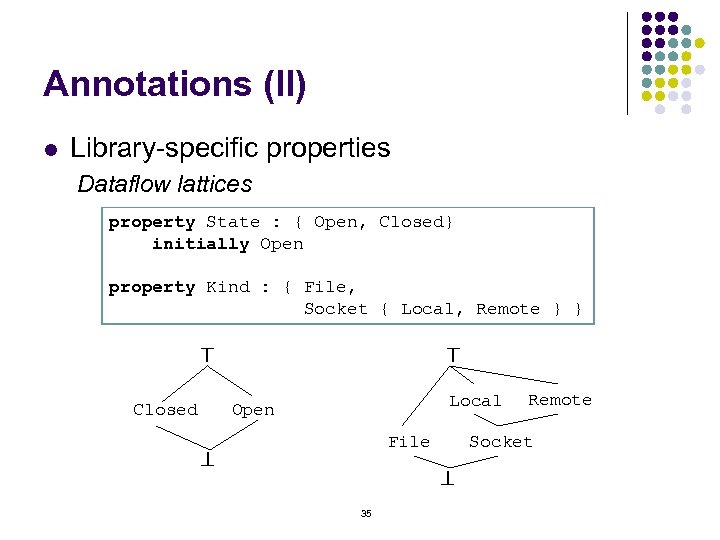

Annotations (II) Library-specific properties Dataflow lattices property State : { Open, Closed} initially Open property Kind : { File, Socket { Local, Remote } } ^ Closed ^ l Local Open File ^ Socket ^ 35 Remote

Annotations (II) Library-specific properties Dataflow lattices property State : { Open, Closed} initially Open property Kind : { File, Socket { Local, Remote } } ^ Closed ^ l Local Open File ^ Socket ^ 35 Remote

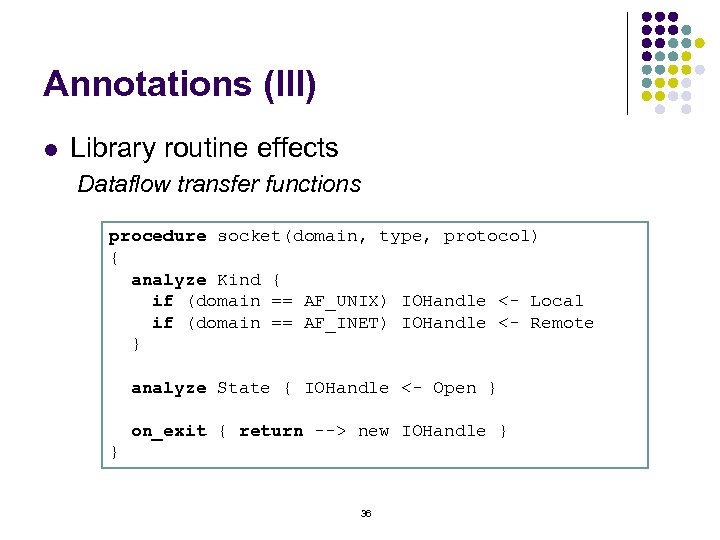

Annotations (III) l Library routine effects Dataflow transfer functions procedure socket(domain, type, protocol) { analyze Kind { if (domain == AF_UNIX) IOHandle <- Local if (domain == AF_INET) IOHandle <- Remote } analyze State { IOHandle <- Open } on_exit { return --> new IOHandle } } 36

Annotations (III) l Library routine effects Dataflow transfer functions procedure socket(domain, type, protocol) { analyze Kind { if (domain == AF_UNIX) IOHandle <- Local if (domain == AF_INET) IOHandle <- Remote } analyze State { IOHandle <- Open } on_exit { return --> new IOHandle } } 36

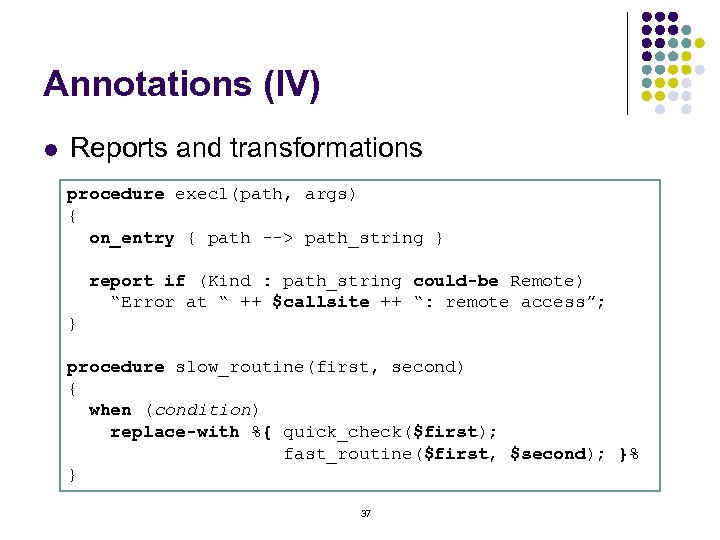

Annotations (IV) l Reports and transformations procedure execl(path, args) { on_entry { path --> path_string } report if (Kind : path_string could-be Remote) “Error at “ ++ $callsite ++ “: remote access”; } procedure slow_routine(first, second) { when (condition) replace-with %{ quick_check($first); fast_routine($first, $second); }% } 37

Annotations (IV) l Reports and transformations procedure execl(path, args) { on_entry { path --> path_string } report if (Kind : path_string could-be Remote) “Error at “ ++ $callsite ++ “: remote access”; } procedure slow_routine(first, second) { when (condition) replace-with %{ quick_check($first); fast_routine($first, $second); }% } 37

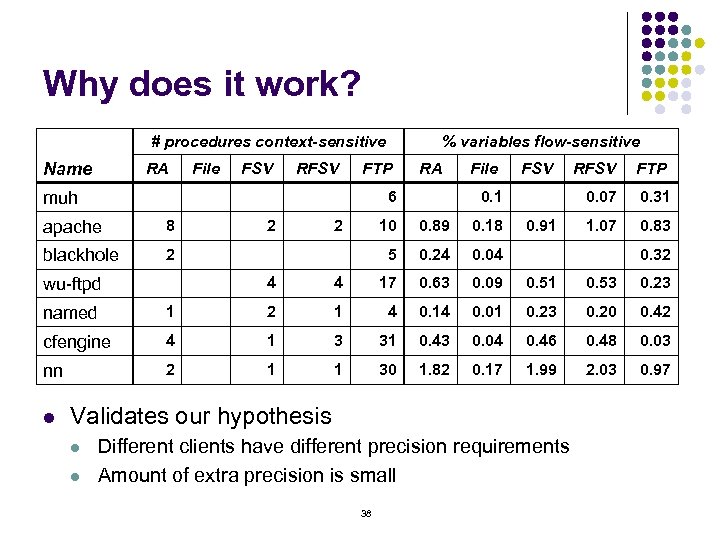

Why does it work? # procedures context-sensitive Name RA File FSV RFSV % variables flow-sensitive FTP RA 6 muh apache 8 blackhole 2 2 2 File FSV 10 0. 89 0. 18 5 0. 24 0. 91 FTP 0. 07 0. 1 RFSV 0. 31 1. 07 0. 83 0. 04 0. 32 4 wu-ftpd 4 17 0. 63 0. 09 0. 51 0. 53 0. 23 named 1 2 1 4 0. 14 0. 01 0. 23 0. 20 0. 42 cfengine 4 1 3 31 0. 43 0. 04 0. 46 0. 48 0. 03 nn 2 1 1 30 1. 82 0. 17 1. 99 2. 03 0. 97 l Validates our hypothesis l l Different clients have different precision requirements Amount of extra precision is small 38

Why does it work? # procedures context-sensitive Name RA File FSV RFSV % variables flow-sensitive FTP RA 6 muh apache 8 blackhole 2 2 2 File FSV 10 0. 89 0. 18 5 0. 24 0. 91 FTP 0. 07 0. 1 RFSV 0. 31 1. 07 0. 83 0. 04 0. 32 4 wu-ftpd 4 17 0. 63 0. 09 0. 51 0. 53 0. 23 named 1 2 1 4 0. 14 0. 01 0. 23 0. 20 0. 42 cfengine 4 1 3 31 0. 43 0. 04 0. 46 0. 48 0. 03 nn 2 1 1 30 1. 82 0. 17 1. 99 2. 03 0. 97 l Validates our hypothesis l l Different clients have different precision requirements Amount of extra precision is small 38

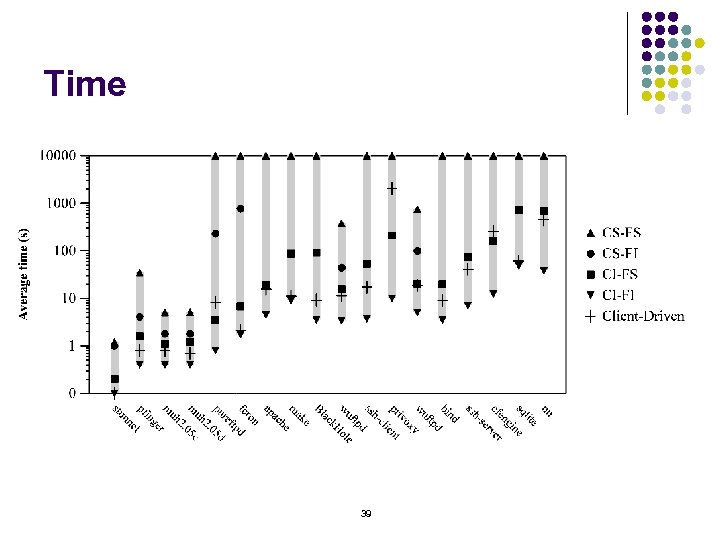

Time 39

Time 39

Validation l Optimization experiments l l l Error checking experiments l l l Cons: One library – three applications Pros: Complex library – consistent results Cons: Quibble about different errors Pros: We set the standard for experiments Overall l Same system designed for optimizations is among the best for detecting errors and security vulnerabilities 40

Validation l Optimization experiments l l l Error checking experiments l l l Cons: One library – three applications Pros: Complex library – consistent results Cons: Quibble about different errors Pros: We set the standard for experiments Overall l Same system designed for optimizations is among the best for detecting errors and security vulnerabilities 40

Type Theory l Equivalent to dataflow analysis (heresy? ) Flow values Types Transfer functions l Different in practice l l l Inference rules Remember Phil Wadler’s talk? Dataflow: flow-sensitive problems, iterative analysis Types: flow-insensitive problems, constraint solver Commonality l l No magic bullet: same cost for the same precision Extracting the store model is a primary concern 41

Type Theory l Equivalent to dataflow analysis (heresy? ) Flow values Types Transfer functions l Different in practice l l l Inference rules Remember Phil Wadler’s talk? Dataflow: flow-sensitive problems, iterative analysis Types: flow-insensitive problems, constraint solver Commonality l l No magic bullet: same cost for the same precision Extracting the store model is a primary concern 41

Generators l Direct support for domain-specific programming l l l Language extensions or new language Generate implementation from specification Our ideas are complementary l l Provides a way to analyze component compositions Unifies common algorithms: l l Redundancy elimination Dependence-based optimizations 42

Generators l Direct support for domain-specific programming l l l Language extensions or new language Generate implementation from specification Our ideas are complementary l l Provides a way to analyze component compositions Unifies common algorithms: l l Redundancy elimination Dependence-based optimizations 42

Is it correct? Three separate questions: l Are Sam Guyer’s experiments correct? l Yes, to the best of our knowledge l l l Is our compiler implemented correctly? l l l Checked PLAPACK results Checked detected errors against known errors Flip answer: who’s is? Better answer: testing suites How do we validate a set of annotations? 43

Is it correct? Three separate questions: l Are Sam Guyer’s experiments correct? l Yes, to the best of our knowledge l l l Is our compiler implemented correctly? l l l Checked PLAPACK results Checked detected errors against known errors Flip answer: who’s is? Better answer: testing suites How do we validate a set of annotations? 43

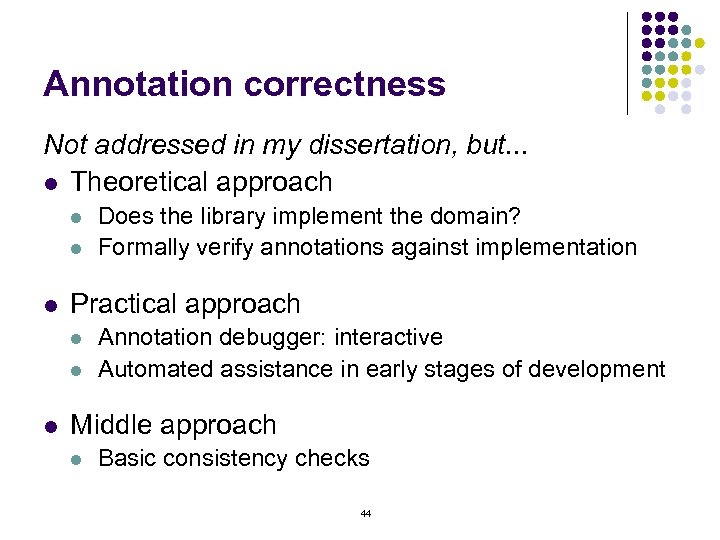

Annotation correctness Not addressed in my dissertation, but. . . l Theoretical approach l l l Practical approach l l l Does the library implement the domain? Formally verify annotations against implementation Annotation debugger: interactive Automated assistance in early stages of development Middle approach l Basic consistency checks 44

Annotation correctness Not addressed in my dissertation, but. . . l Theoretical approach l l l Practical approach l l l Does the library implement the domain? Formally verify annotations against implementation Annotation debugger: interactive Automated assistance in early stages of development Middle approach l Basic consistency checks 44

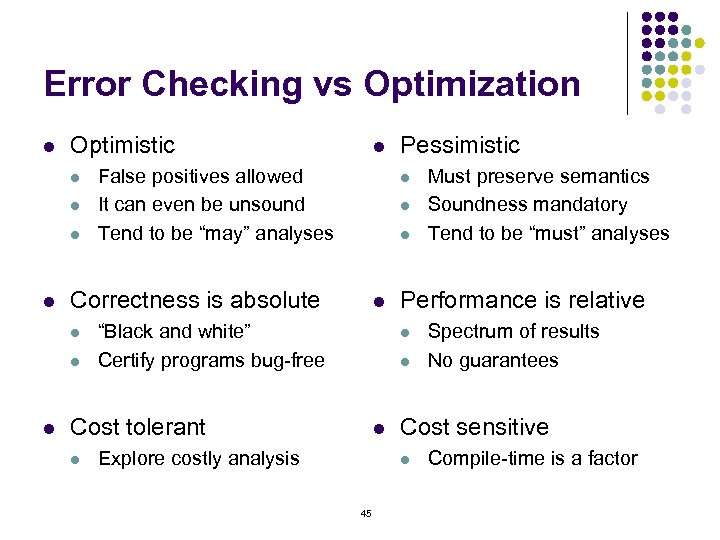

Error Checking vs Optimization l Optimistic l l False positives allowed It can even be unsound Tend to be “may” analyses l l “Black and white” Certify programs bug-free l l Explore costly analysis Spectrum of results No guarantees Cost sensitive l 45 Must preserve semantics Soundness mandatory Tend to be “must” analyses Performance is relative l Cost tolerant l Pessimistic l Correctness is absolute l l l Compile-time is a factor

Error Checking vs Optimization l Optimistic l l False positives allowed It can even be unsound Tend to be “may” analyses l l “Black and white” Certify programs bug-free l l Explore costly analysis Spectrum of results No guarantees Cost sensitive l 45 Must preserve semantics Soundness mandatory Tend to be “must” analyses Performance is relative l Cost tolerant l Pessimistic l Correctness is absolute l l l Compile-time is a factor

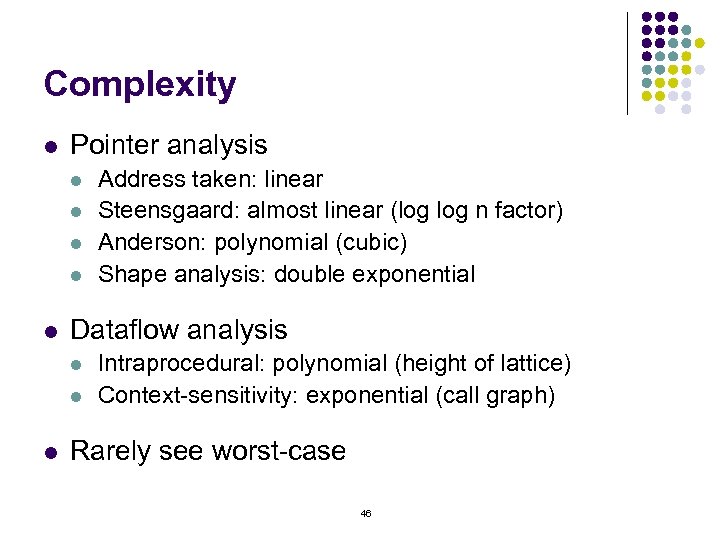

Complexity l Pointer analysis l l l Dataflow analysis l l l Address taken: linear Steensgaard: almost linear (log n factor) Anderson: polynomial (cubic) Shape analysis: double exponential Intraprocedural: polynomial (height of lattice) Context-sensitivity: exponential (call graph) Rarely see worst-case 46

Complexity l Pointer analysis l l l Dataflow analysis l l l Address taken: linear Steensgaard: almost linear (log n factor) Anderson: polynomial (cubic) Shape analysis: double exponential Intraprocedural: polynomial (height of lattice) Context-sensitivity: exponential (call graph) Rarely see worst-case 46

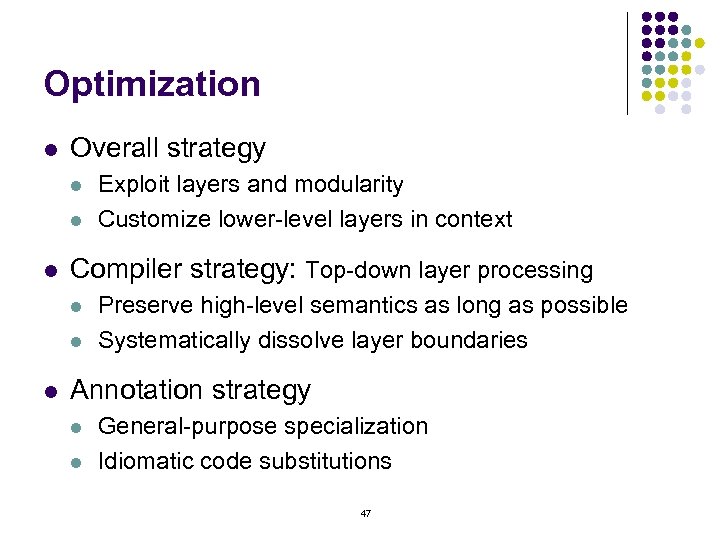

Optimization l Overall strategy l l l Compiler strategy: Top-down layer processing l l l Exploit layers and modularity Customize lower-level layers in context Preserve high-level semantics as long as possible Systematically dissolve layer boundaries Annotation strategy l l General-purpose specialization Idiomatic code substitutions 47

Optimization l Overall strategy l l l Compiler strategy: Top-down layer processing l l l Exploit layers and modularity Customize lower-level layers in context Preserve high-level semantics as long as possible Systematically dissolve layer boundaries Annotation strategy l l General-purpose specialization Idiomatic code substitutions 47

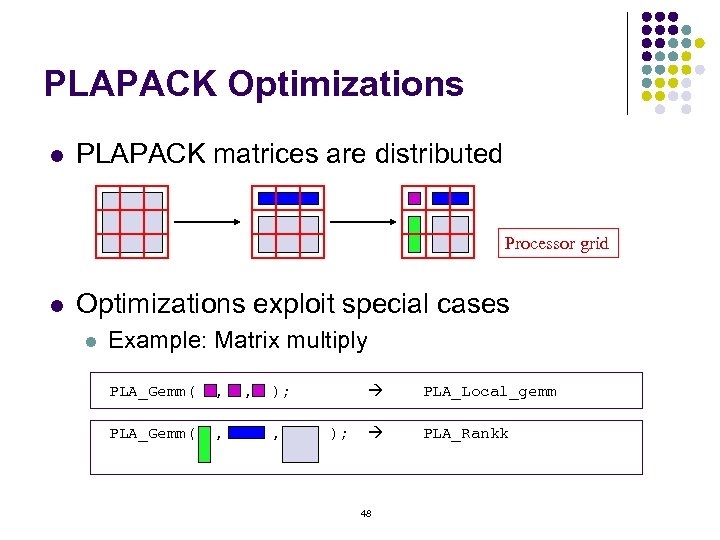

PLAPACK Optimizations l PLAPACK matrices are distributed Processor grid l Optimizations exploit special cases l Example: Matrix multiply PLA_Gemm( , , ); PLA_Local_gemm PLA_Gemm( , , ); PLA_Rankk 48

PLAPACK Optimizations l PLAPACK matrices are distributed Processor grid l Optimizations exploit special cases l Example: Matrix multiply PLA_Gemm( , , ); PLA_Local_gemm PLA_Gemm( , , ); PLA_Rankk 48

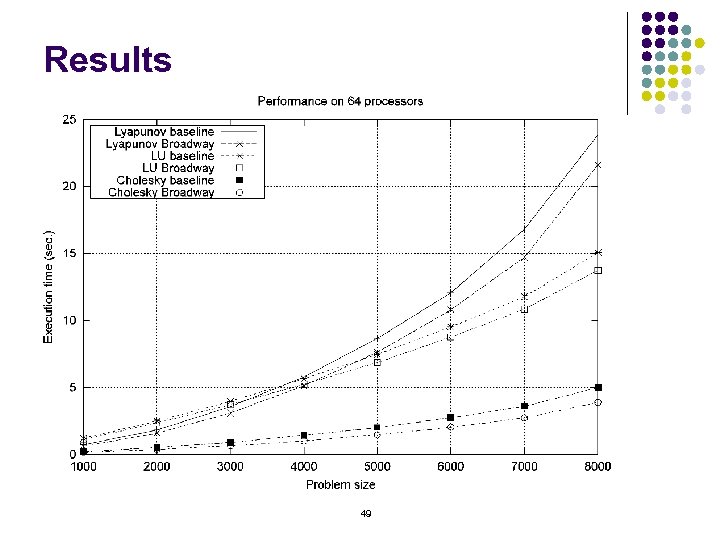

Results 49

Results 49

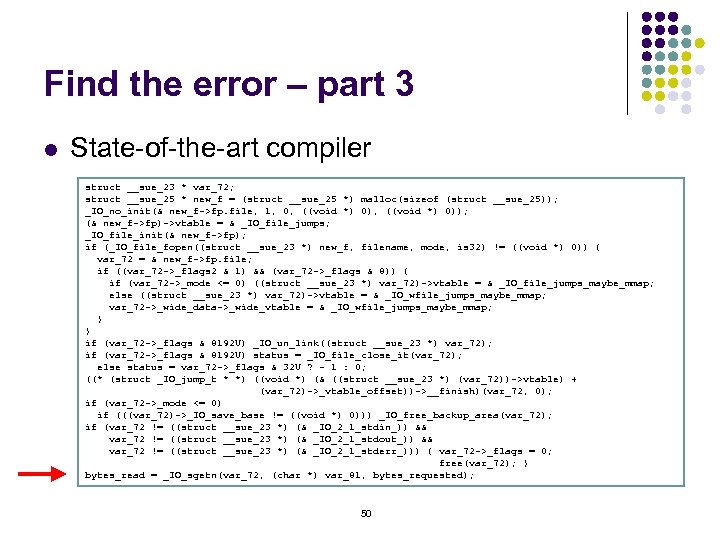

Find the error – part 3 l State-of-the-art compiler struct __sue_23 * var_72; struct __sue_25 * new_f = (struct __sue_25 *) malloc(sizeof (struct __sue_25)); _IO_no_init(& new_f->fp. file, 1, 0, ((void *) 0)); (& new_f->fp)->vtable = & _IO_file_jumps; _IO_file_init(& new_f->fp); if (_IO_file_fopen((struct __sue_23 *) new_f, filename, mode, is 32) != ((void *) 0)) { var_72 = & new_f->fp. file; if ((var_72 ->_flags 2 & 1) && (var_72 ->_flags & 8)) { if (var_72 ->_mode <= 0) ((struct __sue_23 *) var_72)->vtable = & _IO_file_jumps_maybe_mmap; else ((struct __sue_23 *) var_72)->vtable = & _IO_wfile_jumps_maybe_mmap; var_72 ->_wide_data->_wide_vtable = & _IO_wfile_jumps_maybe_mmap; } } if (var_72 ->_flags & 8192 U) _IO_un_link((struct __sue_23 *) var_72); if (var_72 ->_flags & 8192 U) status = _IO_file_close_it(var_72); else status = var_72 ->_flags & 32 U ? - 1 : 0; ((* (struct _IO_jump_t * *) ((void *) (& ((struct __sue_23 *) (var_72))->vtable) + (var_72)->_vtable_offset))->__finish)(var_72, 0); if (var_72 ->_mode <= 0) if (((var_72)->_IO_save_base != ((void *) 0))) _IO_free_backup_area(var_72); if (var_72 != ((struct __sue_23 *) (& _IO_2_1_stdin_)) && var_72 != ((struct __sue_23 *) (& _IO_2_1_stdout_)) && var_72 != ((struct __sue_23 *) (& _IO_2_1_stderr_))) { var_72 ->_flags = 0; free(var_72); } bytes_read = _IO_sgetn(var_72, (char *) var_81, bytes_requested); 50

Find the error – part 3 l State-of-the-art compiler struct __sue_23 * var_72; struct __sue_25 * new_f = (struct __sue_25 *) malloc(sizeof (struct __sue_25)); _IO_no_init(& new_f->fp. file, 1, 0, ((void *) 0)); (& new_f->fp)->vtable = & _IO_file_jumps; _IO_file_init(& new_f->fp); if (_IO_file_fopen((struct __sue_23 *) new_f, filename, mode, is 32) != ((void *) 0)) { var_72 = & new_f->fp. file; if ((var_72 ->_flags 2 & 1) && (var_72 ->_flags & 8)) { if (var_72 ->_mode <= 0) ((struct __sue_23 *) var_72)->vtable = & _IO_file_jumps_maybe_mmap; else ((struct __sue_23 *) var_72)->vtable = & _IO_wfile_jumps_maybe_mmap; var_72 ->_wide_data->_wide_vtable = & _IO_wfile_jumps_maybe_mmap; } } if (var_72 ->_flags & 8192 U) _IO_un_link((struct __sue_23 *) var_72); if (var_72 ->_flags & 8192 U) status = _IO_file_close_it(var_72); else status = var_72 ->_flags & 32 U ? - 1 : 0; ((* (struct _IO_jump_t * *) ((void *) (& ((struct __sue_23 *) (var_72))->vtable) + (var_72)->_vtable_offset))->__finish)(var_72, 0); if (var_72 ->_mode <= 0) if (((var_72)->_IO_save_base != ((void *) 0))) _IO_free_backup_area(var_72); if (var_72 != ((struct __sue_23 *) (& _IO_2_1_stdin_)) && var_72 != ((struct __sue_23 *) (& _IO_2_1_stdout_)) && var_72 != ((struct __sue_23 *) (& _IO_2_1_stderr_))) { var_72 ->_flags = 0; free(var_72); } bytes_read = _IO_sgetn(var_72, (char *) var_81, bytes_requested); 50

End backup slides 51

End backup slides 51