8502e73986d26dfcf0208151ad7078c2.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 43

Implementation Science: a letter from the UK Martin Eccles

Implementation Science: a letter from the UK Martin Eccles

What’s in a name? That which we call KT by any other name would smell as sweet. (Shakespear W, 1597) • A study of 33 applied research funding agencies across nine countries identified 29 terms used to refer to some aspect of the processes around clinically effective practice (Tetroe et al, 2008) • And what about “Translational Research”? – First and second translation gaps – Mainly thought of as the T 1 bench to bedside process of transferring basic science knowledge into new drugs and technologies – Attracting about 1% of the research funding devoted to T 1 research the T 2 Translational Research is the process of taking current scientific knowledge and ensuring it is applied in routine clinical care (Woolf 2008)

What’s in a name? That which we call KT by any other name would smell as sweet. (Shakespear W, 1597) • A study of 33 applied research funding agencies across nine countries identified 29 terms used to refer to some aspect of the processes around clinically effective practice (Tetroe et al, 2008) • And what about “Translational Research”? – First and second translation gaps – Mainly thought of as the T 1 bench to bedside process of transferring basic science knowledge into new drugs and technologies – Attracting about 1% of the research funding devoted to T 1 research the T 2 Translational Research is the process of taking current scientific knowledge and ensuring it is applied in routine clinical care (Woolf 2008)

Crazy little thing called … Implementation Research? (Queen, 1994) • “Implementation research is the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of clinical research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and hence to improve the quality (effectiveness, reliability, safety, appropriateness, equity, efficiency) of health care. It includes the study of influences on healthcare professional and organisational behaviour. ” – (adapted from Implementation Science http: //www. implementationscience. com/info/about/ accessed 10/03/08).

Crazy little thing called … Implementation Research? (Queen, 1994) • “Implementation research is the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of clinical research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and hence to improve the quality (effectiveness, reliability, safety, appropriateness, equity, efficiency) of health care. It includes the study of influences on healthcare professional and organisational behaviour. ” – (adapted from Implementation Science http: //www. implementationscience. com/info/about/ accessed 10/03/08).

Good behavior is the last refuge of mediocrity. (Henry S. Haskins) • Implementation research centrally involves the study of changing behaviour and maintaining changed behaviours – of and in organizations and the groups and individual healthcare professionals within them • It concerns: – The study of behaviour – The determinants of behaviour – How to change and maintain behaviour • All with due cognisance of the organisational context within which behaviours are enacted

Good behavior is the last refuge of mediocrity. (Henry S. Haskins) • Implementation research centrally involves the study of changing behaviour and maintaining changed behaviours – of and in organizations and the groups and individual healthcare professionals within them • It concerns: – The study of behaviour – The determinants of behaviour – How to change and maintain behaviour • All with due cognisance of the organisational context within which behaviours are enacted

Those that are good manners at the court are as ridiculous in the country as the behaviour of the country is most mockable at the court. (As you like it) • This is worth emphasizing because there is often confusion between the study of behaviour and its determinants and the study of changing behaviour • Consequences for the design and conduct of studies – Use experimental designs – Describing (often complex) interventions – Describing the important elements of care delivered in the control group – Clarifying the “active ingredients” of interventions – Defining outcomes – Considering measurement of process variables – Calculating effect sizes

Those that are good manners at the court are as ridiculous in the country as the behaviour of the country is most mockable at the court. (As you like it) • This is worth emphasizing because there is often confusion between the study of behaviour and its determinants and the study of changing behaviour • Consequences for the design and conduct of studies – Use experimental designs – Describing (often complex) interventions – Describing the important elements of care delivered in the control group – Clarifying the “active ingredients” of interventions – Defining outcomes – Considering measurement of process variables – Calculating effect sizes

• Why is Implementation Research important?

• Why is Implementation Research important?

1. There are important gaps in applying clinical evidence in routine healthcare – The findings from clinical and health services research can not change population health outcomes unless health care systems, organizations and professionals adopt them in practice – A consistent finding is that the transfer of research findings into practice is unpredictable and can be a slow and haphazard process

1. There are important gaps in applying clinical evidence in routine healthcare – The findings from clinical and health services research can not change population health outcomes unless health care systems, organizations and professionals adopt them in practice – A consistent finding is that the transfer of research findings into practice is unpredictable and can be a slow and haphazard process

UK care gaps • • The Chief Medical Officer’s 2005 report On the State of the Public Health. A review of quality of care studies – In almost all studies the process of care did not reach the standards set out in national guidelines or set by the researchers themselves An evaluation of the impact of NICE guidance across nine areas: – effects on the use of drugs or technologies that could be confidently ascribed to the release of the guidance occurring in only two cases. The Health Foundation report on quality gaps in stroke care reported figures from the RCP Sentinel Stoke Audit – rates of achievement against a set of key indicators varying from 54% to 76%

UK care gaps • • The Chief Medical Officer’s 2005 report On the State of the Public Health. A review of quality of care studies – In almost all studies the process of care did not reach the standards set out in national guidelines or set by the researchers themselves An evaluation of the impact of NICE guidance across nine areas: – effects on the use of drugs or technologies that could be confidently ascribed to the release of the guidance occurring in only two cases. The Health Foundation report on quality gaps in stroke care reported figures from the RCP Sentinel Stoke Audit – rates of achievement against a set of key indicators varying from 54% to 76%

International care gaps • Researchers in the US and the Netherlands – estimated that 35 -45% of patients are not receiving care according to the scientific evidence – 20 -25% of care provided is not needed or could cause harm • Australia’s National Institute of Clinical Studies – monitors performance against standards for 11 conditions that span a range of clinical conditions and primary and secondary care. – They show varying sized gaps between the evidence and current performance. – Monitor these indicators over time they also chart the changes in the gaps and service and policy initiatives to close them. They demonstrate persisting gaps.

International care gaps • Researchers in the US and the Netherlands – estimated that 35 -45% of patients are not receiving care according to the scientific evidence – 20 -25% of care provided is not needed or could cause harm • Australia’s National Institute of Clinical Studies – monitors performance against standards for 11 conditions that span a range of clinical conditions and primary and secondary care. – They show varying sized gaps between the evidence and current performance. – Monitor these indicators over time they also chart the changes in the gaps and service and policy initiatives to close them. They demonstrate persisting gaps.

2. Healthcare professionals and organisations are unlikely to innovate systematically and reliably – Structured review of healthcare professionals views on clinician engagement in quality improvement (Davies et al, 2007) • 86 empirical reports relevant to the review • Healthcare professionals are heterogeneous » » • their definition of quality their perception of the need for quality improvement their attitudes to quality improvement initiatives their attitudes to clinical guidelines and evidence-based practice In addition, they have a limited understanding of the concepts and methods of quality improvement and quality improvement is often the scene of turf battles.

2. Healthcare professionals and organisations are unlikely to innovate systematically and reliably – Structured review of healthcare professionals views on clinician engagement in quality improvement (Davies et al, 2007) • 86 empirical reports relevant to the review • Healthcare professionals are heterogeneous » » • their definition of quality their perception of the need for quality improvement their attitudes to quality improvement initiatives their attitudes to clinical guidelines and evidence-based practice In addition, they have a limited understanding of the concepts and methods of quality improvement and quality improvement is often the scene of turf battles.

3. The health gains from successful implementation can exceed those of enhancing current technologies – Woolf (2005) has argued that the relative inattention to implementing what we know is costing lives. • Imbalance between investment in the development of new drugs and technologies versus improving the fidelity with which care is delivered • The latter attracts 1% of the resources of the former • Two examples – studies to produce new drugs with enhanced efficacy would fail to achieve the health gains that could be achieved by delivering older agents to all eligible patients.

3. The health gains from successful implementation can exceed those of enhancing current technologies – Woolf (2005) has argued that the relative inattention to implementing what we know is costing lives. • Imbalance between investment in the development of new drugs and technologies versus improving the fidelity with which care is delivered • The latter attracts 1% of the resources of the former • Two examples – studies to produce new drugs with enhanced efficacy would fail to achieve the health gains that could be achieved by delivering older agents to all eligible patients.

Implementation Research – a sizeable evidence base but … • Over the past 15 -20 years a body of implementation research has developed – Interventions can be effective – The effects are “worth having” • Effectiveness of interventions varies across different clinical problems, contexts and organizations

Implementation Research – a sizeable evidence base but … • Over the past 15 -20 years a body of implementation research has developed – Interventions can be effective – The effects are “worth having” • Effectiveness of interventions varies across different clinical problems, contexts and organizations

but … still a young science • Studies provided scant theoretical or conceptual rationale for their choice of intervention (Davies et al, 2003) • Limited descriptions of the interventions and contextual data (Grimshaw et al, 2004) • Provides less information to guide the choice or optimise the components of (often complex) interventions in practice (Foy et al, 2005) • Research on economic and political approaches to change is scarce – Not surprising that little is known about how best to integrate disease and case management interventions into existing healthcare at the system level

but … still a young science • Studies provided scant theoretical or conceptual rationale for their choice of intervention (Davies et al, 2003) • Limited descriptions of the interventions and contextual data (Grimshaw et al, 2004) • Provides less information to guide the choice or optimise the components of (often complex) interventions in practice (Foy et al, 2005) • Research on economic and political approaches to change is scarce – Not surprising that little is known about how best to integrate disease and case management interventions into existing healthcare at the system level

Theory is splendid but until put into practice, it is valueless. (James Cash Penney) The use of theory in Implementation Research offers (at least) three important potential advantages – Theories offer • a generalisable framework that can apply across differing settings and individuals • the opportunity for the incremental accumulation of knowledge • an explicit framework for analysis So far, so good …. but …

Theory is splendid but until put into practice, it is valueless. (James Cash Penney) The use of theory in Implementation Research offers (at least) three important potential advantages – Theories offer • a generalisable framework that can apply across differing settings and individuals • the opportunity for the incremental accumulation of knowledge • an explicit framework for analysis So far, so good …. but …

In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is (Yogi Berra) • No clear agreement about what makes a study or an intervention “theory-based” – Range of phrases such as “informed by theory”, “underpinned by theory”, “theory-inspired” and “theory-based” • Little agreement about which theories are important and under what circumstances • There is considerable overlap between theories • And then there are models and frameworks ….

In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is (Yogi Berra) • No clear agreement about what makes a study or an intervention “theory-based” – Range of phrases such as “informed by theory”, “underpinned by theory”, “theory-inspired” and “theory-based” • Little agreement about which theories are important and under what circumstances • There is considerable overlap between theories • And then there are models and frameworks ….

What’s next? (Bartlett J, The West Wing, 2004) • Science of implementation research is still a work in progress • It is a relatively young science • What might be on the agenda? • What happens when you try this for real?

What’s next? (Bartlett J, The West Wing, 2004) • Science of implementation research is still a work in progress • It is a relatively young science • What might be on the agenda? • What happens when you try this for real?

Research Agenda? : 1 • The research areas are: – Context; – Behavioural determinants and evaluation of change strategies; – Testing (& development) of theory in implementation research; – Knowledge attributes and knowledge generation • Cross cutting issues – Methodology; – Implementation Research across different areas of clinical practice; – Knowledge infrastructure for Implementation; – Sustainability of interventions

Research Agenda? : 1 • The research areas are: – Context; – Behavioural determinants and evaluation of change strategies; – Testing (& development) of theory in implementation research; – Knowledge attributes and knowledge generation • Cross cutting issues – Methodology; – Implementation Research across different areas of clinical practice; – Knowledge infrastructure for Implementation; – Sustainability of interventions

Research Agenda? : 2 • Communication strategy/engagement • Workforce issues – Capacity to do implementation; – Capacity to do implementation research • Attributes of research teams addressing this agenda • Implementation and evidence of benefit from clinical and public health interventions So …. What happens when you try to do some of this?

Research Agenda? : 2 • Communication strategy/engagement • Workforce issues – Capacity to do implementation; – Capacity to do implementation research • Attributes of research teams addressing this agenda • Implementation and evidence of benefit from clinical and public health interventions So …. What happens when you try to do some of this?

Two theories good, four theories better (Animal Farm) PRIME • To explore the usefulness of a range of psychological frameworks to predict health professional behaviour relating to the management of: – upper respiratory tract infections without antibiotics (Eccles et al, 2007) • Psychological measures were collected by postal questionnaire survey from a random sample of general practitioners (GPs) in Scotland

Two theories good, four theories better (Animal Farm) PRIME • To explore the usefulness of a range of psychological frameworks to predict health professional behaviour relating to the management of: – upper respiratory tract infections without antibiotics (Eccles et al, 2007) • Psychological measures were collected by postal questionnaire survey from a random sample of general practitioners (GPs) in Scotland

Conclusions • The theories individually each explained a significant proportion of the variance in our dependent variables – Aggregated analysis suggested that they were measuring similar phenomena within their own individual structures • What would be an optimum core set of measures if the aim was to cover most behaviours and clinical groups? – Given our current limited understanding this would have to be the subject of studies replicating this one and further work examining different combinations of theories and models. • Operationalising the constructs with theoretical purity was a challenge • Problems with measuring behaviour • Response rates

Conclusions • The theories individually each explained a significant proportion of the variance in our dependent variables – Aggregated analysis suggested that they were measuring similar phenomena within their own individual structures • What would be an optimum core set of measures if the aim was to cover most behaviours and clinical groups? – Given our current limited understanding this would have to be the subject of studies replicating this one and further work examining different combinations of theories and models. • Operationalising the constructs with theoretical purity was a challenge • Problems with measuring behaviour • Response rates

Next steps: Intervention building and testing • Baseline survey identifies causal determinants • Evaluate the impact of two theory-based interventions on the behavioural intention and simulated behaviour of GPs in relation to the management of uncomplicated URTI – A randomised 2 x 2 factorial design with baseline and postintervention assessment – Measures were delivered in two postal questionnaire surveys, with the study interventions embedded within the second questionnaire – Participants responding to the first survey were included in the second and were randomised twice to receive, or not, each of the two study interventions.

Next steps: Intervention building and testing • Baseline survey identifies causal determinants • Evaluate the impact of two theory-based interventions on the behavioural intention and simulated behaviour of GPs in relation to the management of uncomplicated URTI – A randomised 2 x 2 factorial design with baseline and postintervention assessment – Measures were delivered in two postal questionnaire surveys, with the study interventions embedded within the second questionnaire – Participants responding to the first survey were included in the second and were randomised twice to receive, or not, each of the two study interventions.

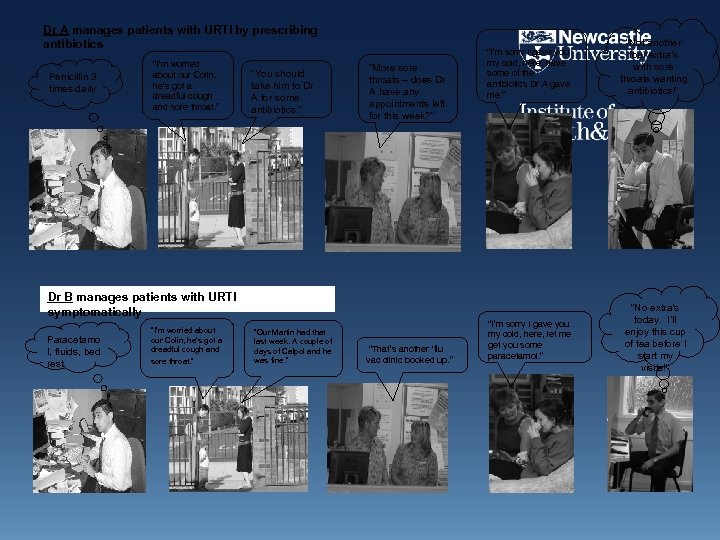

Interventions • Intervention 2 targeted anticipated consequences and risk perception (also from SCT) • Mapped on to theoretical construct domain, “beliefs about consequences” • The main behaviour change technique selected was “persuasive communication” – The aim of this intervention was to encourage GPs to consider some potential consequences for themselves, their patients and society of managing URTI with and without prescribing antibiotics. • This intervention also incorporated the behaviour change technique, “provide information regarding behaviour, outcome and connection between the two”

Interventions • Intervention 2 targeted anticipated consequences and risk perception (also from SCT) • Mapped on to theoretical construct domain, “beliefs about consequences” • The main behaviour change technique selected was “persuasive communication” – The aim of this intervention was to encourage GPs to consider some potential consequences for themselves, their patients and society of managing URTI with and without prescribing antibiotics. • This intervention also incorporated the behaviour change technique, “provide information regarding behaviour, outcome and connection between the two”

Dr A manages patients with URTI by prescribing antibiotics Penicillin 3 times daily “I’m worried about our Colin, he’s got a dreadful cough and sore throat. ” “You should take him to Dr A for some antibiotics. ” “More sore throats – does Dr A have any appointments left for this week? ” “I’m sorry I gave you my cold, here, have some of the antibiotics Dr A gave me. ” Dr B manages patients with URTI symptomatically Paracetamo l, fluids, bed rest “I’m worried about our Colin, he’s got a dreadful cough and sore throat. ” “Our Martin had that last week. A couple of days of Calpol and he was fine. ” “That’s another ‘flu vac clinic booked up. ” “I’m sorry I gave you my cold, here, let me get you some paracetamol. ” “Not another four extra’s with sore throats wanting antibiotics!” “No extra’s today. I’ll enjoy this cup of tea before I start my visits!”

Dr A manages patients with URTI by prescribing antibiotics Penicillin 3 times daily “I’m worried about our Colin, he’s got a dreadful cough and sore throat. ” “You should take him to Dr A for some antibiotics. ” “More sore throats – does Dr A have any appointments left for this week? ” “I’m sorry I gave you my cold, here, have some of the antibiotics Dr A gave me. ” Dr B manages patients with URTI symptomatically Paracetamo l, fluids, bed rest “I’m worried about our Colin, he’s got a dreadful cough and sore throat. ” “Our Martin had that last week. A couple of days of Calpol and he was fine. ” “That’s another ‘flu vac clinic booked up. ” “I’m sorry I gave you my cold, here, let me get you some paracetamol. ” “Not another four extra’s with sore throats wanting antibiotics!” “No extra’s today. I’ll enjoy this cup of tea before I start my visits!”

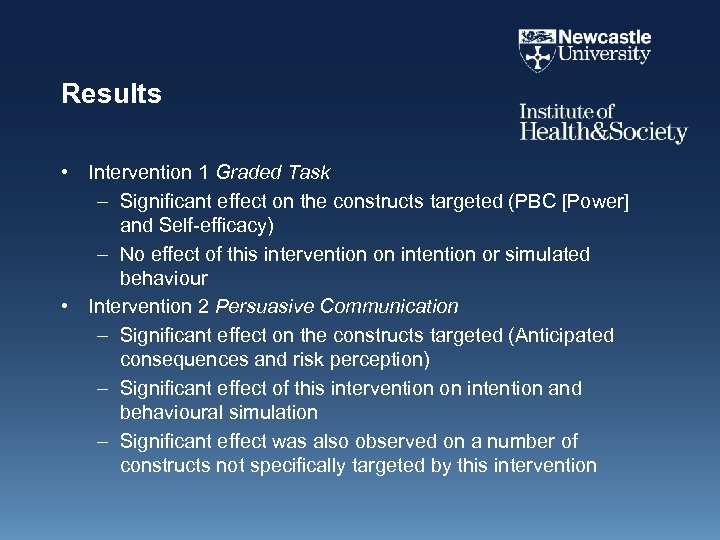

Results • Intervention 1 Graded Task – Significant effect on the constructs targeted (PBC [Power] and Self-efficacy) – No effect of this intervention on intention or simulated behaviour • Intervention 2 Persuasive Communication – Significant effect on the constructs targeted (Anticipated consequences and risk perception) – Significant effect of this intervention on intention and behavioural simulation – Significant effect was also observed on a number of constructs not specifically targeted by this intervention

Results • Intervention 1 Graded Task – Significant effect on the constructs targeted (PBC [Power] and Self-efficacy) – No effect of this intervention on intention or simulated behaviour • Intervention 2 Persuasive Communication – Significant effect on the constructs targeted (Anticipated consequences and risk perception) – Significant effect of this intervention on intention and behavioural simulation – Significant effect was also observed on a number of constructs not specifically targeted by this intervention

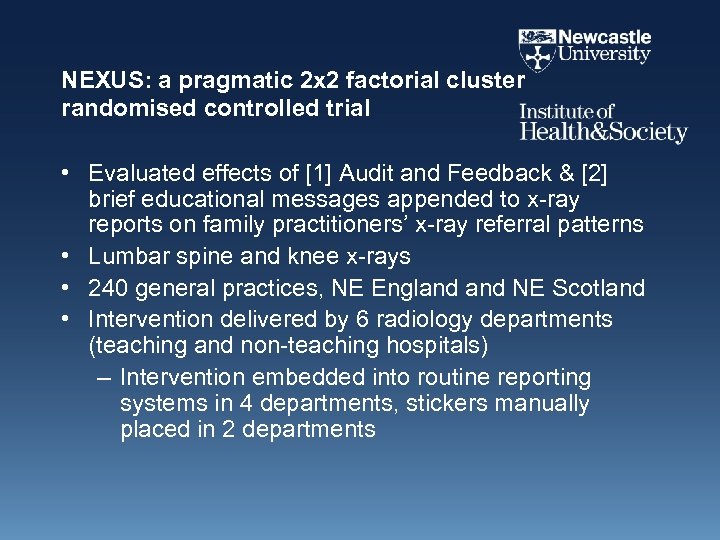

NEXUS: a pragmatic 2 x 2 factorial cluster randomised controlled trial • Evaluated effects of [1] Audit and Feedback & [2] brief educational messages appended to x-ray reports on family practitioners’ x-ray referral patterns • Lumbar spine and knee x-rays • 240 general practices, NE England NE Scotland • Intervention delivered by 6 radiology departments (teaching and non-teaching hospitals) – Intervention embedded into routine reporting systems in 4 departments, stickers manually placed in 2 departments

NEXUS: a pragmatic 2 x 2 factorial cluster randomised controlled trial • Evaluated effects of [1] Audit and Feedback & [2] brief educational messages appended to x-ray reports on family practitioners’ x-ray referral patterns • Lumbar spine and knee x-rays • 240 general practices, NE England NE Scotland • Intervention delivered by 6 radiology departments (teaching and non-teaching hospitals) – Intervention embedded into routine reporting systems in 4 departments, stickers manually placed in 2 departments

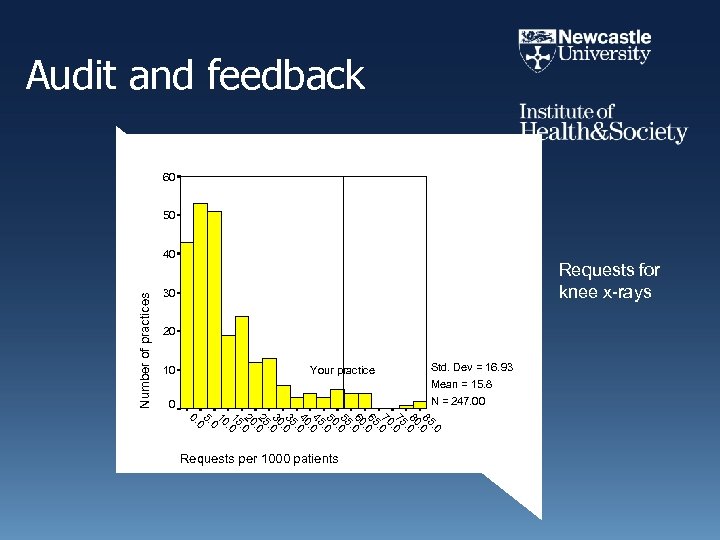

Audit and feedback 60 60 50 50 Number of practices 40 40 Requests for knee x-rays 30 30 20 20 10 10 Your practice 0 0 Std. Dev = 16. 93 Mean = 15. 8 N = 247. 00 . 0. 0 85. 5. 0 80 80. 0. 0 80 75. 5. 0 70 70. 0. 0 70 65. 5. 0 60 60. 0. 0 60 55. 5. 0 50 50. 0. 0 50 45. 5. 0 40 40. 0. 0 40 35. 5. 0 30 30. 0. 0 30 20 25. 5. 0 20 20. 0. 0 10 15. 5. 0 1 10 0 00 5. 5. 00 0. 0. Requests per 1000 patients

Audit and feedback 60 60 50 50 Number of practices 40 40 Requests for knee x-rays 30 30 20 20 10 10 Your practice 0 0 Std. Dev = 16. 93 Mean = 15. 8 N = 247. 00 . 0. 0 85. 5. 0 80 80. 0. 0 80 75. 5. 0 70 70. 0. 0 70 65. 5. 0 60 60. 0. 0 60 55. 5. 0 50 50. 0. 0 50 45. 5. 0 40 40. 0. 0 40 35. 5. 0 30 30. 0. 0 30 20 25. 5. 0 20 20. 0. 0 10 15. 5. 0 1 10 0 00 5. 5. 00 0. 0. Requests per 1000 patients

Second intervention • NEXUS EDUCATIONAL MESSAGE In either acute (less than 6 weeks) or chronic back pain, without adverse features, x-ray is not routinely indicated In adults with knee pain, without significant locking or restriction in movement, x-ray is not routinely indicated

Second intervention • NEXUS EDUCATIONAL MESSAGE In either acute (less than 6 weeks) or chronic back pain, without adverse features, x-ray is not routinely indicated In adults with knee pain, without significant locking or restriction in movement, x-ray is not routinely indicated

Results • Over the 12 months of the intervention period – Audit & Feedback • No effect – Brief educational messages • 20 -30% relative reduction in x-ray requests • No difference in effects across radiology departments in different settings or by method of delivery

Results • Over the 12 months of the intervention period – Audit & Feedback • No effect – Brief educational messages • 20 -30% relative reduction in x-ray requests • No difference in effects across radiology departments in different settings or by method of delivery

What about chronic diseases? Multiple actors & different levels • Diabetes QI Study • To improve the quality of care for patients with diabetes cared for in primary care by identifying individual, team & organisational factors that predict high quality care – Obj 1: To measure attributes of individual HCPs, teams and their organisation in primary care within a theoretical framework – Obj 2. To measure the organisational structure in primary care – Obj 3. To measure the process of care, markers of biological control & QOF scores – Obj 4. To identify configurations associated with high quality care

What about chronic diseases? Multiple actors & different levels • Diabetes QI Study • To improve the quality of care for patients with diabetes cared for in primary care by identifying individual, team & organisational factors that predict high quality care – Obj 1: To measure attributes of individual HCPs, teams and their organisation in primary care within a theoretical framework – Obj 2. To measure the organisational structure in primary care – Obj 3. To measure the process of care, markers of biological control & QOF scores – Obj 4. To identify configurations associated with high quality care

Measures 1 • Practice structures and function – Practice demographics (including practice list size; training status of the practice, postcodes covered) – Routine booking intervals for patient consultations – Staffing levels of practice staff (numbers of, and number of sessions worked by, doctors, practice employed nurses & administrative staff) – Skill mix (ratio of doctors to non-medical clinical staff and of clinical to administrative staff) – Organisation of care for the clinical conditions (including specialisation within the clinicians).

Measures 1 • Practice structures and function – Practice demographics (including practice list size; training status of the practice, postcodes covered) – Routine booking intervals for patient consultations – Staffing levels of practice staff (numbers of, and number of sessions worked by, doctors, practice employed nurses & administrative staff) – Skill mix (ratio of doctors to non-medical clinical staff and of clinical to administrative staff) – Organisation of care for the clinical conditions (including specialisation within the clinicians).

Measures 2 • Individual’s cognitions about their own and others behaviour – Social Cognitive Theory – Theory of planned behaviour (TPB) – Self-Report Habit Index – Implementation Intentions (action planning (the initiation of a behaviour) and coping planning (the mental simulation of overcoming anticipated barriers to action in order to maintain changed behaviours) – Operant learning theory

Measures 2 • Individual’s cognitions about their own and others behaviour – Social Cognitive Theory – Theory of planned behaviour (TPB) – Self-Report Habit Index – Implementation Intentions (action planning (the initiation of a behaviour) and coping planning (the mental simulation of overcoming anticipated barriers to action in order to maintain changed behaviours) – Operant learning theory

Measures 3 • Individuals’ cognitions about work characteristics will be measured using – Karasek’s Job Decision Latitude Scale and Job Demands Scale – Siegrist’s effort-reward imbalance measure – Cognitions about the team will be measured using the shortened version of the original Team Climate Inventory – Cognitions about the organisation will be measured using the organizational justice evaluation scale

Measures 3 • Individuals’ cognitions about work characteristics will be measured using – Karasek’s Job Decision Latitude Scale and Job Demands Scale – Siegrist’s effort-reward imbalance measure – Cognitions about the team will be measured using the shortened version of the original Team Climate Inventory – Cognitions about the organisation will be measured using the organizational justice evaluation scale

Relating individuals’ cognitions to behaviour • All self report measures are at the individual level • Behaviour (for most chronic diseases) is at practice level and is the product of the behaviour of teams of individuals • How do you best express the collective cognitions of a team in terms of explaining behaviour? – Mean – Use highest intender and most control – Use values of person whose role it is

Relating individuals’ cognitions to behaviour • All self report measures are at the individual level • Behaviour (for most chronic diseases) is at practice level and is the product of the behaviour of teams of individuals • How do you best express the collective cognitions of a team in terms of explaining behaviour? – Mean – Use highest intender and most control – Use values of person whose role it is

Conclusions • Implementation science is a work in progress • Need good collaborators – Multi and inter-disciplinary • Need good methodologists – Methodological challenges

Conclusions • Implementation science is a work in progress • Need good collaborators – Multi and inter-disciplinary • Need good methodologists – Methodological challenges

• “Love means … never having to say you’re sorry” – (Jennifer Cavilleri, Love Story, 1970) • Implementation Science means … never having to say that there is nowhere to publish your protocols, intervention development descriptions, discussion papers, theoretical pieces, policy articles …

• “Love means … never having to say you’re sorry” – (Jennifer Cavilleri, Love Story, 1970) • Implementation Science means … never having to say that there is nowhere to publish your protocols, intervention development descriptions, discussion papers, theoretical pieces, policy articles …

Implementation Science: unofficial Impact Factor 4. 43 Co-Editors in Chief Martin Eccles, Brian Mittman Implementationscience. editors@ncl. ac. uk Scope All aspects of research relevant to the scientific study of methods to promote the uptake of research findings into routine healthcare in both clinical and policy contexts www. implementationscience. com

Implementation Science: unofficial Impact Factor 4. 43 Co-Editors in Chief Martin Eccles, Brian Mittman Implementationscience. editors@ncl. ac. uk Scope All aspects of research relevant to the scientific study of methods to promote the uptake of research findings into routine healthcare in both clinical and policy contexts www. implementationscience. com

Thank you Good Afternoon

Thank you Good Afternoon

Quality gap references • • Seddon ME, Marshall MN, Campbell SM, Roland MO. Systematic review of studies of quality of clinical care in general practice in the UK, Australia and New Zealand. QHC 2001; 10(3): 152 -8. Sheldon TA et al. What's the evidence that NICE guidance has been implemented? Results from a national evaluation using time series analysis, audit of patients' notes, and interviews. BMJ. 2004; 329(7473): 999. Leatherman S, Sutherland K, Airoldi M. Bridging the quality gap: Stroke. The Health Foundation, London, 2008. Royal College of Physicians (2005). National Sentinel Stroke Audit Report, 2004. RCP. Mc. Glynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks A, De. Cristofaro A, Kerr EA. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 2003 ; 348: 2635 -45. Schuster ME, Mc. Glynn E, Brook RH. How good is the quality of healthcare in the Unitd States? Millbank Quarterly 1998; 76: 517 -63. Grol R. Successes and failures in the implementation of evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice. Medical Care 2001; 39: 46 -54. National Institute of Clinical Studies, Evidence-Practice Gaps Report Volume 1: A review of developments: 2004– 2007. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2008.

Quality gap references • • Seddon ME, Marshall MN, Campbell SM, Roland MO. Systematic review of studies of quality of clinical care in general practice in the UK, Australia and New Zealand. QHC 2001; 10(3): 152 -8. Sheldon TA et al. What's the evidence that NICE guidance has been implemented? Results from a national evaluation using time series analysis, audit of patients' notes, and interviews. BMJ. 2004; 329(7473): 999. Leatherman S, Sutherland K, Airoldi M. Bridging the quality gap: Stroke. The Health Foundation, London, 2008. Royal College of Physicians (2005). National Sentinel Stroke Audit Report, 2004. RCP. Mc. Glynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks A, De. Cristofaro A, Kerr EA. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 2003 ; 348: 2635 -45. Schuster ME, Mc. Glynn E, Brook RH. How good is the quality of healthcare in the Unitd States? Millbank Quarterly 1998; 76: 517 -63. Grol R. Successes and failures in the implementation of evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice. Medical Care 2001; 39: 46 -54. National Institute of Clinical Studies, Evidence-Practice Gaps Report Volume 1: A review of developments: 2004– 2007. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2008.

Other references • • Davies P, Walker A, Grimshaw J. Theories of behaviour change in studies of guideline implementation. Proceedings of the British Psychological Society 2003; 11(1): 120. Davies H, Powell A, Rushmer R. Healthcare professionals’ views on clinician engagement in quality improvement: A literature review. The Health Foundation, London, 2007. Eccles M, Steen N, Grimshaw J, Thomas L, Mc. Namee P, Soutter J, Wilsdon J, Matowe L, Needham G, Gilbert F, Bond S. Effect of audit and feedback, and reminder messages on primary-care radiology referrals: a randomised trial. Lancet 2001; 357: 1406 -1409. Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, Johnston M, Steen N, Pitts NB, Thomas R, Glidewell E, Maclennan G, Bonetti D, Walker A. Applying psychological theories to evidence-based clinical practice: Identifying factors predictive of managing upper respiratory tract infections without antibiotics. Implementation Science, 2007, 2: 26. Ferlie EB, Shortell SM. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: a framework for change. The Milbank Quarterly 2001; 79(2): 281 -315. Foy R, Eccles M, Jamtvedt G, Grimshaw J, Baker R. What do we know about how to do audit and feedback? BMC Health Services Research 2005; 5: 50. Graham ID, Tetroe J, and the KT Theories Research Group. Some Theoretical Underpinnings of Knowledge Translation. Academic Emergency Medicine 2007; 14: 936– 941.

Other references • • Davies P, Walker A, Grimshaw J. Theories of behaviour change in studies of guideline implementation. Proceedings of the British Psychological Society 2003; 11(1): 120. Davies H, Powell A, Rushmer R. Healthcare professionals’ views on clinician engagement in quality improvement: A literature review. The Health Foundation, London, 2007. Eccles M, Steen N, Grimshaw J, Thomas L, Mc. Namee P, Soutter J, Wilsdon J, Matowe L, Needham G, Gilbert F, Bond S. Effect of audit and feedback, and reminder messages on primary-care radiology referrals: a randomised trial. Lancet 2001; 357: 1406 -1409. Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, Johnston M, Steen N, Pitts NB, Thomas R, Glidewell E, Maclennan G, Bonetti D, Walker A. Applying psychological theories to evidence-based clinical practice: Identifying factors predictive of managing upper respiratory tract infections without antibiotics. Implementation Science, 2007, 2: 26. Ferlie EB, Shortell SM. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: a framework for change. The Milbank Quarterly 2001; 79(2): 281 -315. Foy R, Eccles M, Jamtvedt G, Grimshaw J, Baker R. What do we know about how to do audit and feedback? BMC Health Services Research 2005; 5: 50. Graham ID, Tetroe J, and the KT Theories Research Group. Some Theoretical Underpinnings of Knowledge Translation. Academic Emergency Medicine 2007; 14: 936– 941.

• • • Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, Mac. Lennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guidline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess 2004; 8(6): 1 -84 Hrisos S, Eccles M, Johnston M, Francis J, Kaner E, Steen N, Grimshaw J. An intervention modelling experiment to change GPs' intentions to implement evidence-based practice: Using theory-based interventions to promote GP management of upper respiratory tract infection without prescribing antibiotics. BMC Health Services Research 2008: 8; 10. Hrisos S, Eccles M, Johnston M, Francis J, Kaner E, Steen N, Grimshaw J. Developing the content of two behavioural interventions. Using theory-based interventions to promote GP management of upper respiratory tract infection without prescribing antibiotics. BMC Health Services Research 2008: 8; 11 Tetroe JM, Graham ID, Foy R, Robinson N, Eccles MP, Ward J, Wensing M, Durieux P, Légaré F, Palmhoj Nielson C, Adily A, Porter C, Shea B, Grimshaw J. Health Research Funding Agencies’ Support and Promotion of Knowledge Translation: an International Study. Millbank Quarterly 2008: 86; 125 -155. Woolf SH, Johnson RE. The Break-Even Point: When Medical Advances Are Less Important Than Improving the Fidelity With Which They Are Delivered. Ann Fam Med 2005; 3: 545 -552. Woolf SH. The Meaning of Translational Research and Why It Matters. JAMA, 2008; 299: 211 213.

• • • Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, Mac. Lennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guidline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess 2004; 8(6): 1 -84 Hrisos S, Eccles M, Johnston M, Francis J, Kaner E, Steen N, Grimshaw J. An intervention modelling experiment to change GPs' intentions to implement evidence-based practice: Using theory-based interventions to promote GP management of upper respiratory tract infection without prescribing antibiotics. BMC Health Services Research 2008: 8; 10. Hrisos S, Eccles M, Johnston M, Francis J, Kaner E, Steen N, Grimshaw J. Developing the content of two behavioural interventions. Using theory-based interventions to promote GP management of upper respiratory tract infection without prescribing antibiotics. BMC Health Services Research 2008: 8; 11 Tetroe JM, Graham ID, Foy R, Robinson N, Eccles MP, Ward J, Wensing M, Durieux P, Légaré F, Palmhoj Nielson C, Adily A, Porter C, Shea B, Grimshaw J. Health Research Funding Agencies’ Support and Promotion of Knowledge Translation: an International Study. Millbank Quarterly 2008: 86; 125 -155. Woolf SH, Johnson RE. The Break-Even Point: When Medical Advances Are Less Important Than Improving the Fidelity With Which They Are Delivered. Ann Fam Med 2005; 3: 545 -552. Woolf SH. The Meaning of Translational Research and Why It Matters. JAMA, 2008; 299: 211 213.