9e09ba84a3100cecc1bdfab302319be7.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 98

IMPLEMENTATION

IMPLEMENTATION

Implementation l Process of translating the detailed design into code l Real-life products are generally too large to be implemented by a single programmer l “programming-in-the-many” – a team working at the same time on different components of the product

Implementation l Process of translating the detailed design into code l Real-life products are generally too large to be implemented by a single programmer l “programming-in-the-many” – a team working at the same time on different components of the product

Choice of Programming Language l The programming language is usually specified in the contract l But what if the contract specifies that ¡The product is to be implemented in the “most suitable” programming language l What language should be chosen?

Choice of Programming Language l The programming language is usually specified in the contract l But what if the contract specifies that ¡The product is to be implemented in the “most suitable” programming language l What language should be chosen?

Choice of Programming Language How to choose a programming language ¡Cost–benefit analysis as well as risk analysis should be performed ¡Compute costs and benefits of all relevant languages l Which is the most appropriate object-oriented language? ¡C++ is C-like ¡Thus, every classical C program is automatically a C++ program ¡Java enforces the object-oriented paradigm ¡Training in the object-oriented paradigm is essential before adopting any object-oriented language

Choice of Programming Language How to choose a programming language ¡Cost–benefit analysis as well as risk analysis should be performed ¡Compute costs and benefits of all relevant languages l Which is the most appropriate object-oriented language? ¡C++ is C-like ¡Thus, every classical C program is automatically a C++ program ¡Java enforces the object-oriented paradigm ¡Training in the object-oriented paradigm is essential before adopting any object-oriented language

Good programming practice l Variable names should be consistent and meaningful l As program will be studied by many people – especially during maintenance ¡If frequency, freq refer to the same item then should only use one name ¡If freq_max is being used then should use freq_min instead of min_freg

Good programming practice l Variable names should be consistent and meaningful l As program will be studied by many people – especially during maintenance ¡If frequency, freq refer to the same item then should only use one name ¡If freq_max is being used then should use freq_min instead of min_freg

The Issue of Self-Documenting Code l Program does not need comment because it is carefully written with proper variable names, structured etc l Self-documenting code (the program is written so well that it reads like a document) is exceedingly rare l The key issue: Can the code artifact (program ) be understood easily and unambiguously by ¡The SQA (software quality assurance) team ¡Maintenance programmers ¡All others who have to read the code ¡Even the original programmers after couple of years l A prologue comments should be included in every program

The Issue of Self-Documenting Code l Program does not need comment because it is carefully written with proper variable names, structured etc l Self-documenting code (the program is written so well that it reads like a document) is exceedingly rare l The key issue: Can the code artifact (program ) be understood easily and unambiguously by ¡The SQA (software quality assurance) team ¡Maintenance programmers ¡All others who have to read the code ¡Even the original programmers after couple of years l A prologue comments should be included in every program

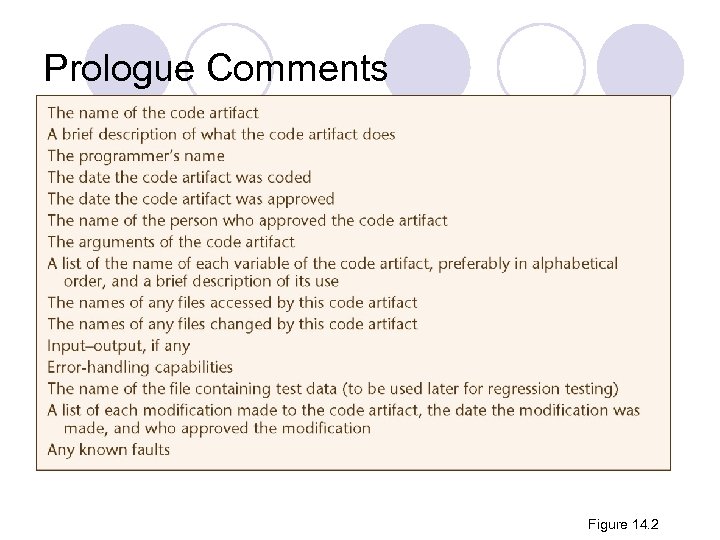

Prologue Comments l Minimal prologue comments for a code artifact Figure 14. 2

Prologue Comments l Minimal prologue comments for a code artifact Figure 14. 2

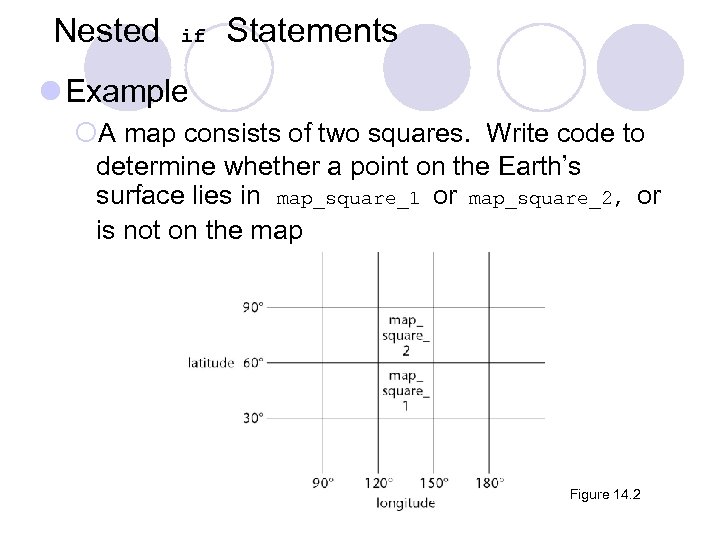

Nested if Statements l Example ¡A map consists of two squares. Write code to determine whether a point on the Earth’s surface lies in map_square_1 or map_square_2, or is not on the map Figure 14. 2

Nested if Statements l Example ¡A map consists of two squares. Write code to determine whether a point on the Earth’s surface lies in map_square_1 or map_square_2, or is not on the map Figure 14. 2

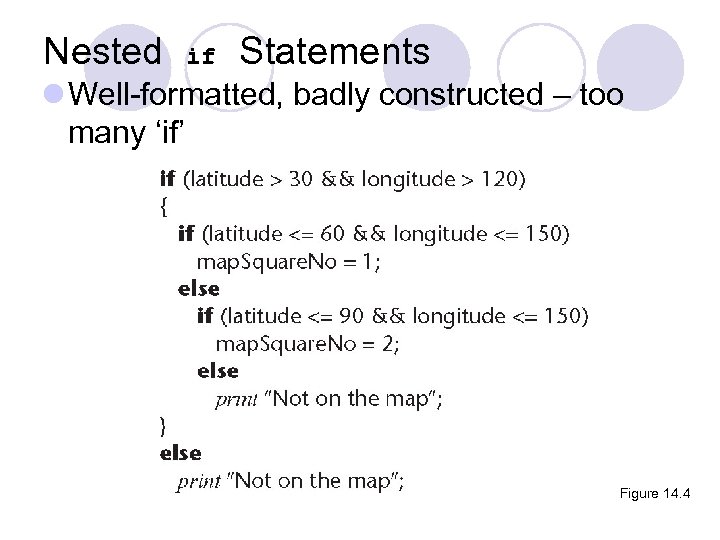

Nested if Statements l Well-formatted, badly constructed – too many ‘if’ Figure 14. 4

Nested if Statements l Well-formatted, badly constructed – too many ‘if’ Figure 14. 4

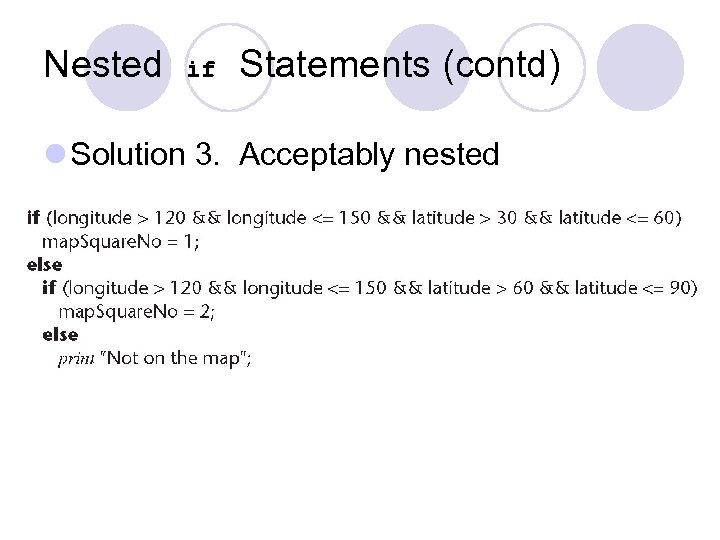

Nested if Statements (contd) l Solution 3. Acceptably nested Figure 14. 5

Nested if Statements (contd) l Solution 3. Acceptably nested Figure 14. 5

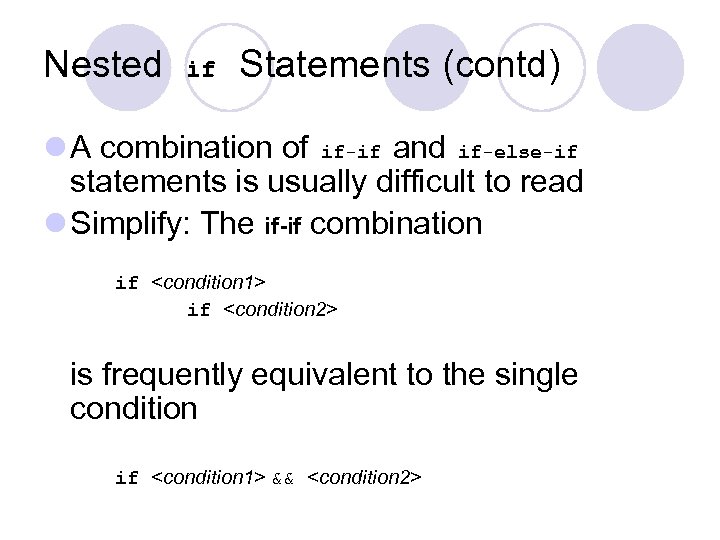

Nested if Statements (contd) l A combination of if-if and if-else-if statements is usually difficult to read l Simplify: The if-if combination if

Nested if Statements (contd) l A combination of if-if and if-else-if statements is usually difficult to read l Simplify: The if-if combination if

Nested if Statements (contd) l Rule of thumb statements nested to a depth of greater than three should be avoided as poor programming practice ¡ if

Nested if Statements (contd) l Rule of thumb statements nested to a depth of greater than three should be avoided as poor programming practice ¡ if

Programming Standards l Setting rules for the program writing – such as “each module will consist of between 35 and 50 executable statements” l Aim of coding standards is to make maintenance easier. l Flexibility should be considered when designing the rules, example ¡“Programmers should consult their managers before constructing a module with fewer than 35 or more than 50 executable statements”

Programming Standards l Setting rules for the program writing – such as “each module will consist of between 35 and 50 executable statements” l Aim of coding standards is to make maintenance easier. l Flexibility should be considered when designing the rules, example ¡“Programmers should consult their managers before constructing a module with fewer than 35 or more than 50 executable statements”

Remarks on Programming Standards l No standard can ever be universally applicable ¡Developing different systems may require different rules l Standards imposed from above will be ignored ¡Rules should be discussed and agreed by the programmers l Standard must be checkable by machine ¡How can you check if rules are being followed?

Remarks on Programming Standards l No standard can ever be universally applicable ¡Developing different systems may require different rules l Standards imposed from above will be ignored ¡Rules should be discussed and agreed by the programmers l Standard must be checkable by machine ¡How can you check if rules are being followed?

Examples of Good Programming Standards l “Nesting of if statements should not exceed a depth of 3, except with prior approval from the team leader” l “Modules should consist of between 35 and 50 statements, except with prior approval from the team leader” l “Use of goto should be avoided. However, with prior approval from the team leader, a forward goto (force exit) may be used for error handling”

Examples of Good Programming Standards l “Nesting of if statements should not exceed a depth of 3, except with prior approval from the team leader” l “Modules should consist of between 35 and 50 statements, except with prior approval from the team leader” l “Use of goto should be avoided. However, with prior approval from the team leader, a forward goto (force exit) may be used for error handling”

Integration l The approach up to now: ¡Implementation followed by integration l This is a poor approach l Better: ¡Combine implementation and integration methodically l Code and test each code artifact separately l Link all artifacts together, test the product as a whole

Integration l The approach up to now: ¡Implementation followed by integration l This is a poor approach l Better: ¡Combine implementation and integration methodically l Code and test each code artifact separately l Link all artifacts together, test the product as a whole

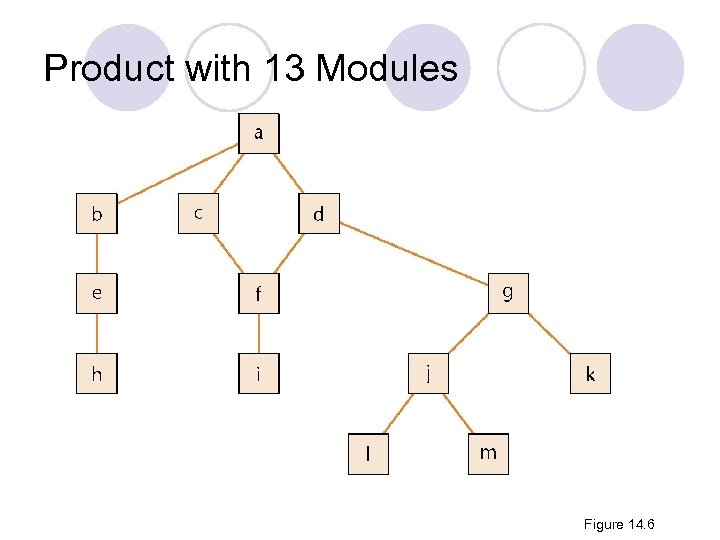

Product with 13 Modules Figure 14. 6

Product with 13 Modules Figure 14. 6

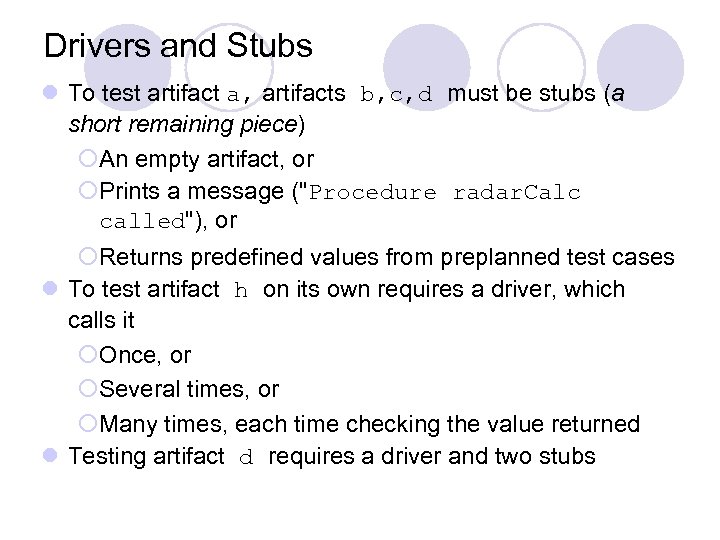

Drivers and Stubs l To test artifact a, artifacts b, c, d must be stubs (a short remaining piece) ¡An empty artifact, or ¡Prints a message ("Procedure radar. Calc called"), or ¡Returns predefined values from preplanned test cases l To test artifact h on its own requires a driver, which calls it ¡Once, or ¡Several times, or ¡Many times, each time checking the value returned l Testing artifact d requires a driver and two stubs

Drivers and Stubs l To test artifact a, artifacts b, c, d must be stubs (a short remaining piece) ¡An empty artifact, or ¡Prints a message ("Procedure radar. Calc called"), or ¡Returns predefined values from preplanned test cases l To test artifact h on its own requires a driver, which calls it ¡Once, or ¡Several times, or ¡Many times, each time checking the value returned l Testing artifact d requires a driver and two stubs

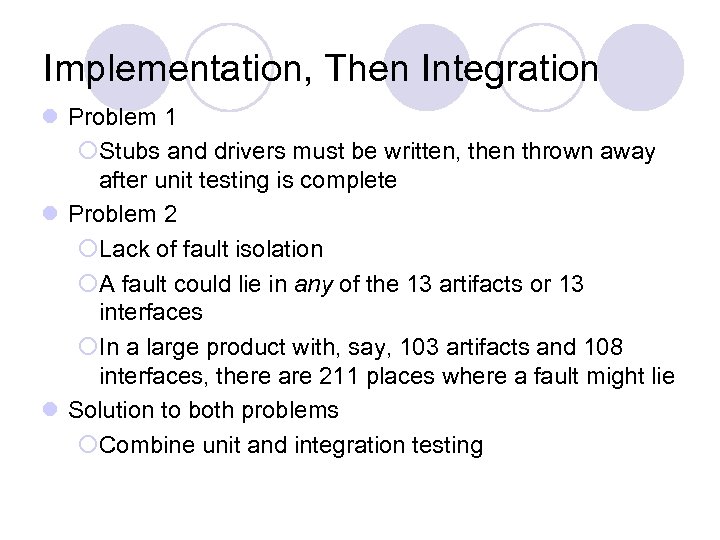

Implementation, Then Integration l Problem 1 ¡Stubs and drivers must be written, then thrown away after unit testing is complete l Problem 2 ¡Lack of fault isolation ¡A fault could lie in any of the 13 artifacts or 13 interfaces ¡In a large product with, say, 103 artifacts and 108 interfaces, there are 211 places where a fault might lie l Solution to both problems ¡Combine unit and integration testing

Implementation, Then Integration l Problem 1 ¡Stubs and drivers must be written, then thrown away after unit testing is complete l Problem 2 ¡Lack of fault isolation ¡A fault could lie in any of the 13 artifacts or 13 interfaces ¡In a large product with, say, 103 artifacts and 108 interfaces, there are 211 places where a fault might lie l Solution to both problems ¡Combine unit and integration testing

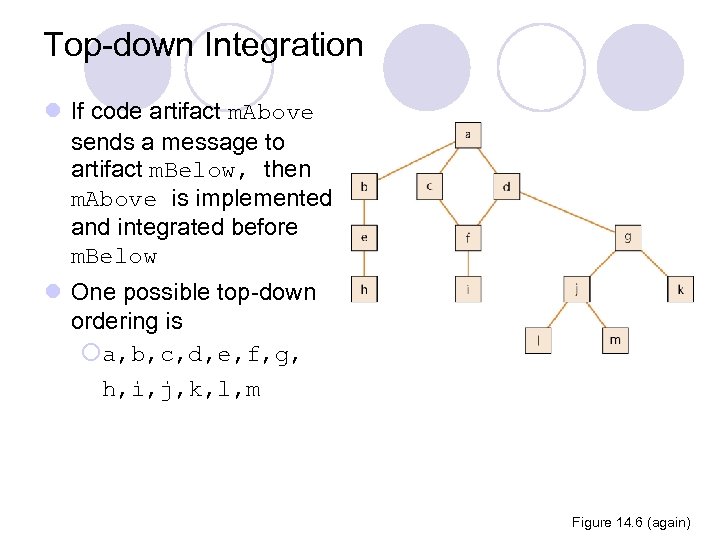

Top-down Integration l If code artifact m. Above sends a message to artifact m. Below, then m. Above is implemented and integrated before m. Below l One possible top-down ordering is ¡a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m Figure 14. 6 (again)

Top-down Integration l If code artifact m. Above sends a message to artifact m. Below, then m. Above is implemented and integrated before m. Below l One possible top-down ordering is ¡a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m Figure 14. 6 (again)

![Top-down Integration (contd) l Another possible top-down ordering is a [a] b, e, h Top-down Integration (contd) l Another possible top-down ordering is a [a] b, e, h](https://present5.com/presentation/9e09ba84a3100cecc1bdfab302319be7/image-21.jpg) Top-down Integration (contd) l Another possible top-down ordering is a [a] b, e, h [a] c, d, f, i [a, d] g, j, k, l, m The above integration sequence cannot executed in parallel Figure 14. 6 (again)

Top-down Integration (contd) l Another possible top-down ordering is a [a] b, e, h [a] c, d, f, i [a, d] g, j, k, l, m The above integration sequence cannot executed in parallel Figure 14. 6 (again)

Top-down Integration (contd) l Advantage 1: Fault isolation ¡A previously successful test case fails when m. New is added to what has been tested so far l. The fault must lie in m. New or the interface(s) between m. New and the rest of the product l Advantage 2: Stubs are not wasted ¡Each stub is expanded into the corresponding complete artifact at the appropriate step

Top-down Integration (contd) l Advantage 1: Fault isolation ¡A previously successful test case fails when m. New is added to what has been tested so far l. The fault must lie in m. New or the interface(s) between m. New and the rest of the product l Advantage 2: Stubs are not wasted ¡Each stub is expanded into the corresponding complete artifact at the appropriate step

Top-down Integration (contd) l Advantage 3: Major design flaws show up early l Logic artifacts include the decision-making flow of control ¡In the example, artifacts a, b, c, d, g, j l Operational artifacts perform the actual operations of the product ¡In the example, artifacts e, f, h, i, k, l, m l The logic artifacts are developed before the operational artifacts

Top-down Integration (contd) l Advantage 3: Major design flaws show up early l Logic artifacts include the decision-making flow of control ¡In the example, artifacts a, b, c, d, g, j l Operational artifacts perform the actual operations of the product ¡In the example, artifacts e, f, h, i, k, l, m l The logic artifacts are developed before the operational artifacts

Top-down Integration (contd) l Problem 1 ¡ Reusable artifacts are not properly tested ¡ Lower level (operational) artifacts are not tested frequently (because you start at the top-level!) l Defensive programming (fault shielding) ¡ Example in the driver: if (x >= 0) y = compute. Square. Root (x, error. Flag); ¡ compute. Square. Root is never tested with x < 0 ¡ This has implications for reuse because testing is not thorough

Top-down Integration (contd) l Problem 1 ¡ Reusable artifacts are not properly tested ¡ Lower level (operational) artifacts are not tested frequently (because you start at the top-level!) l Defensive programming (fault shielding) ¡ Example in the driver: if (x >= 0) y = compute. Square. Root (x, error. Flag); ¡ compute. Square. Root is never tested with x < 0 ¡ This has implications for reuse because testing is not thorough

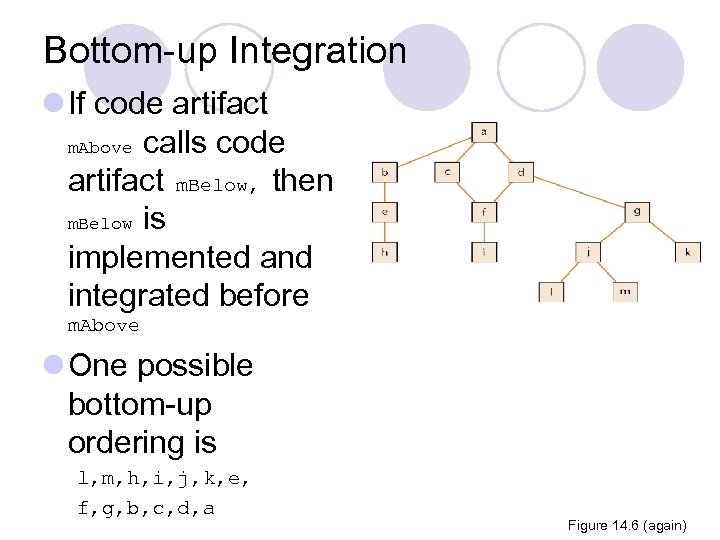

Bottom-up Integration l If code artifact m. Above calls code artifact m. Below, then m. Below is implemented and integrated before m. Above l One possible bottom-up ordering is l, m, h, i, j, k, e, f, g, b, c, d, a Figure 14. 6 (again)

Bottom-up Integration l If code artifact m. Above calls code artifact m. Below, then m. Below is implemented and integrated before m. Above l One possible bottom-up ordering is l, m, h, i, j, k, e, f, g, b, c, d, a Figure 14. 6 (again)

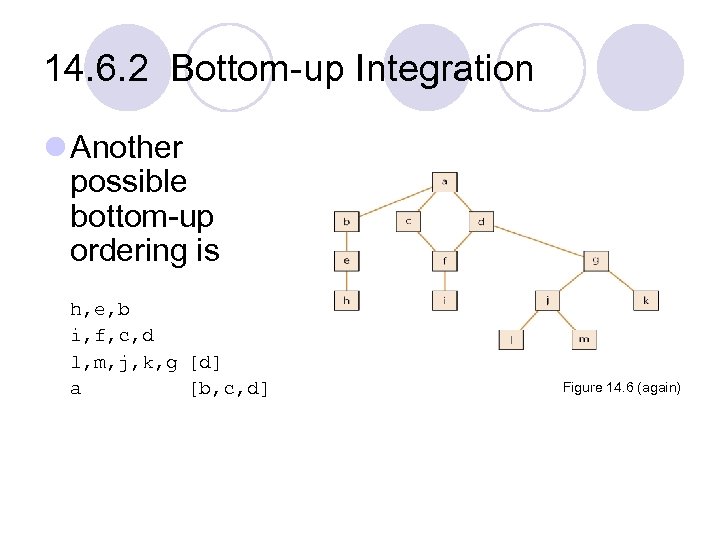

14. 6. 2 Bottom-up Integration l Another possible bottom-up ordering is h, e, b i, f, c, d l, m, j, k, g [d] a [b, c, d] Figure 14. 6 (again)

14. 6. 2 Bottom-up Integration l Another possible bottom-up ordering is h, e, b i, f, c, d l, m, j, k, g [d] a [b, c, d] Figure 14. 6 (again)

Bottom-up Integration (contd) l Advantage 1 ¡Operational artifacts are thoroughly tested l Advantage 2 ¡Operational artifacts are tested with drivers, not by fault shielding, defensively programmed artifacts l Advantage 3 ¡Fault isolation

Bottom-up Integration (contd) l Advantage 1 ¡Operational artifacts are thoroughly tested l Advantage 2 ¡Operational artifacts are tested with drivers, not by fault shielding, defensively programmed artifacts l Advantage 3 ¡Fault isolation

Bottom-up Integration (contd) l Difficulty 1 ¡Major design faults are detected late because design faults usually embedded in the logic modules l Solution ¡Combine top-down and bottom-up strategies making use of their strengths and minimizing their weaknesses

Bottom-up Integration (contd) l Difficulty 1 ¡Major design faults are detected late because design faults usually embedded in the logic modules l Solution ¡Combine top-down and bottom-up strategies making use of their strengths and minimizing their weaknesses

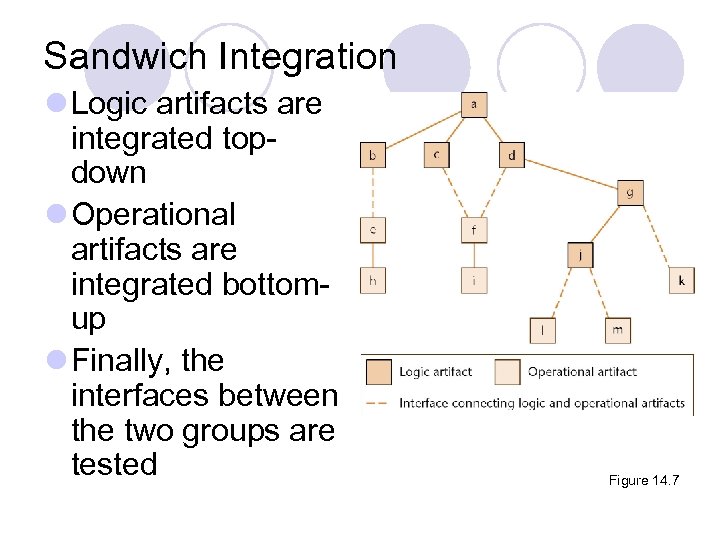

Sandwich Integration l Logic artifacts are integrated topdown l Operational artifacts are integrated bottomup l Finally, the interfaces between the two groups are tested Figure 14. 7

Sandwich Integration l Logic artifacts are integrated topdown l Operational artifacts are integrated bottomup l Finally, the interfaces between the two groups are tested Figure 14. 7

Sandwich Integration (contd) l Advantage 1 ¡Major design faults are caught early l Advantage 2 ¡Operational artifacts are thoroughly tested ¡They may be reused with confidence l Advantage 3 ¡There is fault isolation at all times

Sandwich Integration (contd) l Advantage 1 ¡Major design faults are caught early l Advantage 2 ¡Operational artifacts are thoroughly tested ¡They may be reused with confidence l Advantage 3 ¡There is fault isolation at all times

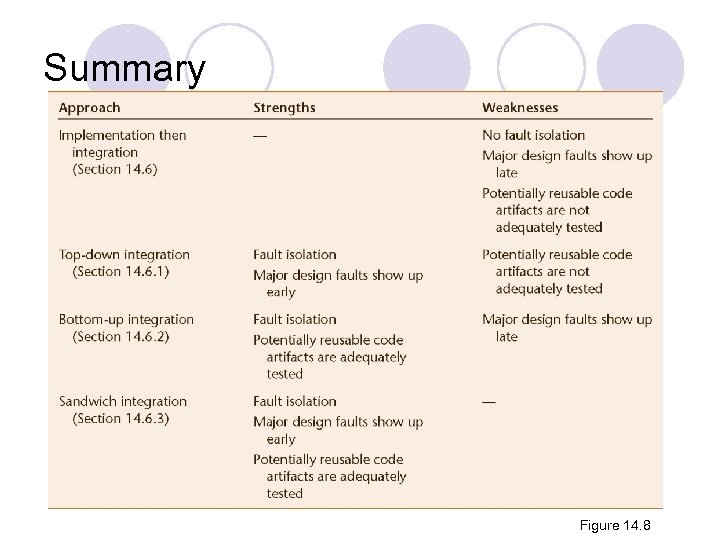

Summary Figure 14. 8

Summary Figure 14. 8

Integration of Object-Oriented Products l Object-oriented implementation and integration ¡Almost always sandwich implementation and integration ¡Objects are integrated bottom-up –assuming objects usually represent the operations ¡Other artifacts are integrated top-down

Integration of Object-Oriented Products l Object-oriented implementation and integration ¡Almost always sandwich implementation and integration ¡Objects are integrated bottom-up –assuming objects usually represent the operations ¡Other artifacts are integrated top-down

14. 7 The Implementation Workflow l The aim of the implementation workflow is to implement the target software product l A large product is partitioned into subsystems ¡Implemented in parallel by coding teams l Subsystems consist of components or code artifacts

14. 7 The Implementation Workflow l The aim of the implementation workflow is to implement the target software product l A large product is partitioned into subsystems ¡Implemented in parallel by coding teams l Subsystems consist of components or code artifacts

The Implementation Workflow (contd) l Once the programmer has implemented an artifact, he or she unit tests it l Then the module is passed on to the SQA group for further testing ¡This testing is part of the test workflow

The Implementation Workflow (contd) l Once the programmer has implemented an artifact, he or she unit tests it l Then the module is passed on to the SQA group for further testing ¡This testing is part of the test workflow

The Test Workflow: Implementation l A number of different types of testing have to be performed during the implementation workflow: ¡Unit testing, integration testing, product testing etc l Unit testing ¡Informal unit testing by the programmer ¡Methodical (systematic) unit testing by the SQA group l There are two types of methodical unit testing ¡Non-execution-based testing ¡Execution-based testing

The Test Workflow: Implementation l A number of different types of testing have to be performed during the implementation workflow: ¡Unit testing, integration testing, product testing etc l Unit testing ¡Informal unit testing by the programmer ¡Methodical (systematic) unit testing by the SQA group l There are two types of methodical unit testing ¡Non-execution-based testing ¡Execution-based testing

Test Case Selection l In order to test, proper test cases must be chosen l Worst way — random testing ¡There is no time to test all but the tiniest fraction of all possible test cases, totaling perhaps 10100 or more ¡We need a systematic way to construct test cases

Test Case Selection l In order to test, proper test cases must be chosen l Worst way — random testing ¡There is no time to test all but the tiniest fraction of all possible test cases, totaling perhaps 10100 or more ¡We need a systematic way to construct test cases

Testing to Specifications versus Testing to Code l There are two extremes to testing l Test to specifications (also called blackbox, data-driven, functional, or input/output driven testing) ¡Ignore the code — use the specifications to select test cases l Test to code (also called glass-box, logicdriven, structured, or path-oriented testing) ¡Ignore the specifications — use the code to select test cases

Testing to Specifications versus Testing to Code l There are two extremes to testing l Test to specifications (also called blackbox, data-driven, functional, or input/output driven testing) ¡Ignore the code — use the specifications to select test cases l Test to code (also called glass-box, logicdriven, structured, or path-oriented testing) ¡Ignore the specifications — use the code to select test cases

Feasibility of Testing to Specifications l Example: ¡ The specifications for a data processing product include 5 types of commission and 7 types of discount ¡ 35 test cases l We cannot say that commission and discount are computed in two entirely separate artifacts; and therefore should be tested separately (test cases are not 5+7) l The structure is irrelevant

Feasibility of Testing to Specifications l Example: ¡ The specifications for a data processing product include 5 types of commission and 7 types of discount ¡ 35 test cases l We cannot say that commission and discount are computed in two entirely separate artifacts; and therefore should be tested separately (test cases are not 5+7) l The structure is irrelevant

Feasibility of Testing to Specifications (contd) l Suppose the specifications include 20 factors (input types), each taking on 4 values ¡There are 420 or 1. 1 ´ 1012 test cases ¡If each takes 30 seconds to run, running all test cases takes more than 1 million years l The combinatorial explosion (the many combinations) makes testing to specifications impossible

Feasibility of Testing to Specifications (contd) l Suppose the specifications include 20 factors (input types), each taking on 4 values ¡There are 420 or 1. 1 ´ 1012 test cases ¡If each takes 30 seconds to run, running all test cases takes more than 1 million years l The combinatorial explosion (the many combinations) makes testing to specifications impossible

14. 10. 3 Feasibility of Testing to Code l Each path through an artifact must be executed at least once ¡Combinatorial explosion still a problem

14. 10. 3 Feasibility of Testing to Code l Each path through an artifact must be executed at least once ¡Combinatorial explosion still a problem

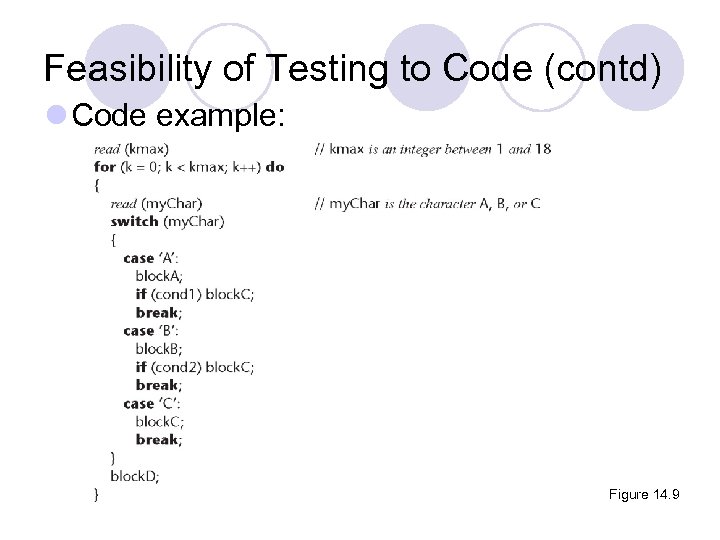

Feasibility of Testing to Code (contd) l Code example: Figure 14. 9

Feasibility of Testing to Code (contd) l Code example: Figure 14. 9

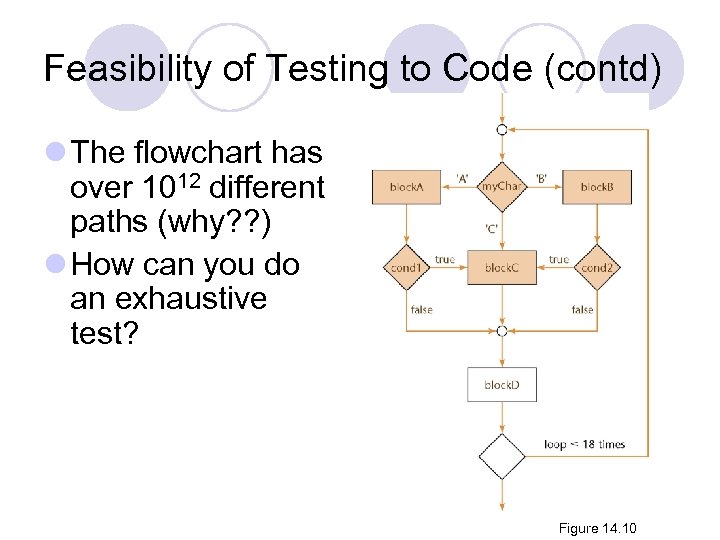

Feasibility of Testing to Code (contd) l The flowchart has over 1012 different paths (why? ? ) l How can you do an exhaustive test? Figure 14. 10

Feasibility of Testing to Code (contd) l The flowchart has over 1012 different paths (why? ? ) l How can you do an exhaustive test? Figure 14. 10

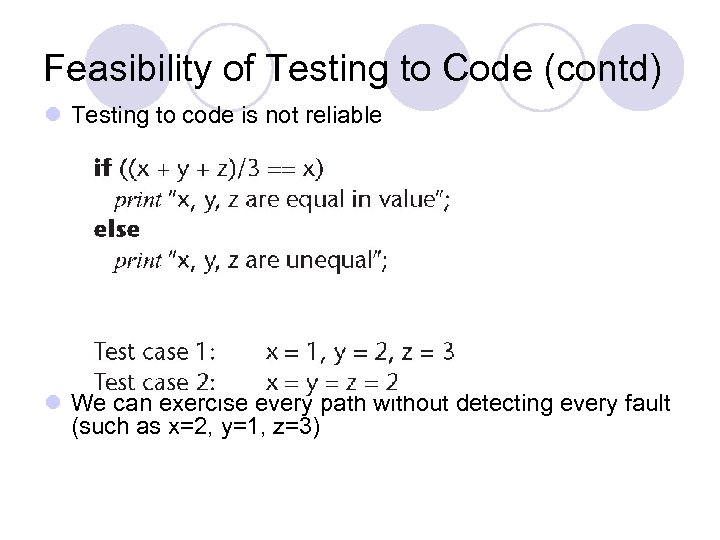

Feasibility of Testing to Code (contd) l Testing to code is not reliable l We can exercise every path without detecting every fault (such as x=2, y=1, z=3)

Feasibility of Testing to Code (contd) l Testing to code is not reliable l We can exercise every path without detecting every fault (such as x=2, y=1, z=3)

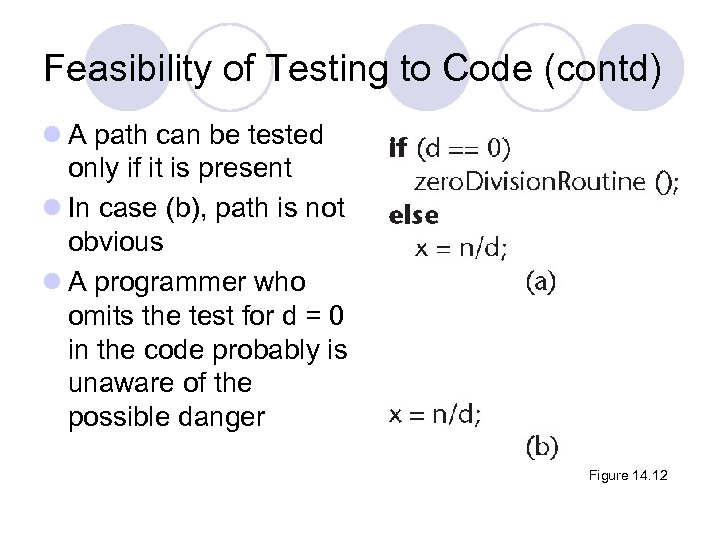

Feasibility of Testing to Code (contd) l A path can be tested only if it is present l In case (b), path is not obvious l A programmer who omits the test for d = 0 in the code probably is unaware of the possible danger Figure 14. 12

Feasibility of Testing to Code (contd) l A path can be tested only if it is present l In case (b), path is not obvious l A programmer who omits the test for d = 0 in the code probably is unaware of the possible danger Figure 14. 12

Black-Box Unit-testing Techniques l Neither exhaustive testing to specifications nor exhaustive testing to code is feasible l The art of testing: ¡Select a small, manageable set of test cases to ¡Maximize the chances of detecting a fault, while ¡Minimizing the chances of wasting a test case l Every test case must detect a previously undetected fault

Black-Box Unit-testing Techniques l Neither exhaustive testing to specifications nor exhaustive testing to code is feasible l The art of testing: ¡Select a small, manageable set of test cases to ¡Maximize the chances of detecting a fault, while ¡Minimizing the chances of wasting a test case l Every test case must detect a previously undetected fault

Black-Box Unit-testing Techniques l We need a method that will highlight as many faults as possible ¡First black-box test cases (testing to specifications) ¡Then glass-box methods (testing to code) l Equivalence testing and boundary value analysis is a form of black-box testing technique

Black-Box Unit-testing Techniques l We need a method that will highlight as many faults as possible ¡First black-box test cases (testing to specifications) ¡Then glass-box methods (testing to code) l Equivalence testing and boundary value analysis is a form of black-box testing technique

Equivalence Testing and Boundary Value Analysis l Example ¡The specifications for a DBMS state that the product must handle any number of records between 1 and 16, 383 (214 – 1) ¡If the system can handle 34 records and 14, 870 records, then it probably will work fine for 8, 252 records l If the system works for any one test case in the range (1. . 16, 383), then it will probably work for any other test case in the range ¡Range (1. . 16, 383) constitutes an equivalence class

Equivalence Testing and Boundary Value Analysis l Example ¡The specifications for a DBMS state that the product must handle any number of records between 1 and 16, 383 (214 – 1) ¡If the system can handle 34 records and 14, 870 records, then it probably will work fine for 8, 252 records l If the system works for any one test case in the range (1. . 16, 383), then it will probably work for any other test case in the range ¡Range (1. . 16, 383) constitutes an equivalence class

Equivalence Testing l Any one member of an equivalence class is as good a test case as any other member of the equivalence class l Range (1. . 16, 383) defines three different equivalence classes: ¡Equivalence Class 1: Fewer than 1 record ¡Equivalence Class 2: Between 1 and 16, 383 records ¡Equivalence Class 3: More than 16, 383 records

Equivalence Testing l Any one member of an equivalence class is as good a test case as any other member of the equivalence class l Range (1. . 16, 383) defines three different equivalence classes: ¡Equivalence Class 1: Fewer than 1 record ¡Equivalence Class 2: Between 1 and 16, 383 records ¡Equivalence Class 3: More than 16, 383 records

Database Example (contd) l Select test cases on or just to one side of the boundary of equivalence classes ¡This greatly increases the probability of detecting a fault l Test case 1: 0 records l Test case 2: 1 record l Test case 3: 2 records l Test case 4: 723 records Member of equivalence class 1 and adjacent to boundary value Boundary value Adjacent to boundary value Member of equivalence class 2

Database Example (contd) l Select test cases on or just to one side of the boundary of equivalence classes ¡This greatly increases the probability of detecting a fault l Test case 1: 0 records l Test case 2: 1 record l Test case 3: 2 records l Test case 4: 723 records Member of equivalence class 1 and adjacent to boundary value Boundary value Adjacent to boundary value Member of equivalence class 2

Database Example (contd) l Test case 5: 16, 382 records l Test case 6: l Test case 7: 16, 383 records 16, 384 records Adjacent to boundary value Boundary value Member of equivalence class 3 and adjacent to boundary value

Database Example (contd) l Test case 5: 16, 382 records l Test case 6: l Test case 7: 16, 383 records 16, 384 records Adjacent to boundary value Boundary value Member of equivalence class 3 and adjacent to boundary value

Equivalence Testing of Output Specifications l We also need to perform equivalence testing of the output specifications l Example: In 2009, the maximum tax return is $6000 Test cases must include input data that should result in return of exactly $0. 00 and exactly $6000 ¡Also, test data that might result in return of less than $0. 00 or more than $6000

Equivalence Testing of Output Specifications l We also need to perform equivalence testing of the output specifications l Example: In 2009, the maximum tax return is $6000 Test cases must include input data that should result in return of exactly $0. 00 and exactly $6000 ¡Also, test data that might result in return of less than $0. 00 or more than $6000

Overall Strategy l Equivalence classes together with boundary value analysis to test both input specifications and output specifications ¡This approach generates a small set of test data with the potential of uncovering a large number of faults

Overall Strategy l Equivalence classes together with boundary value analysis to test both input specifications and output specifications ¡This approach generates a small set of test data with the potential of uncovering a large number of faults

Exercise l Q 2 in 08/09 exam

Exercise l Q 2 in 08/09 exam

Functional Testing l An alternative form of black-box testing for classical software ¡We base the test data on the functionality of the code artifacts l Each item of functionality or function is identified l Test data are devised to test each (lower-level) function separately l Then, higher-level functions composed of these lowerlevel functions are tested

Functional Testing l An alternative form of black-box testing for classical software ¡We base the test data on the functionality of the code artifacts l Each item of functionality or function is identified l Test data are devised to test each (lower-level) function separately l Then, higher-level functions composed of these lowerlevel functions are tested

Functional Testing (contd) l In practice, however ¡Higher-level functions are not always neatly constructed out of lower-level functions using the constructs of structured programming ¡Instead, the lower-level functions are often intertwined ¡For example, consider a complex number division how this can be done?

Functional Testing (contd) l In practice, however ¡Higher-level functions are not always neatly constructed out of lower-level functions using the constructs of structured programming ¡Instead, the lower-level functions are often intertwined ¡For example, consider a complex number division how this can be done?

Functional testing l Also, functionality boundaries do not always coincide with code artifact boundaries ¡The distinction between unit testing and integration testing becomes blurred ¡This problem also can arise in the object-oriented paradigm when messages are passed between objects

Functional testing l Also, functionality boundaries do not always coincide with code artifact boundaries ¡The distinction between unit testing and integration testing becomes blurred ¡This problem also can arise in the object-oriented paradigm when messages are passed between objects

14. 13 Glass-Box Unit-Testing Techniques l Glass-box testing is based on the examination of the code l We will examine ¡Statement coverage ¡Branch coverage ¡Path coverage ¡Linear code sequences ¡All-definition-use path coverage

14. 13 Glass-Box Unit-Testing Techniques l Glass-box testing is based on the examination of the code l We will examine ¡Statement coverage ¡Branch coverage ¡Path coverage ¡Linear code sequences ¡All-definition-use path coverage

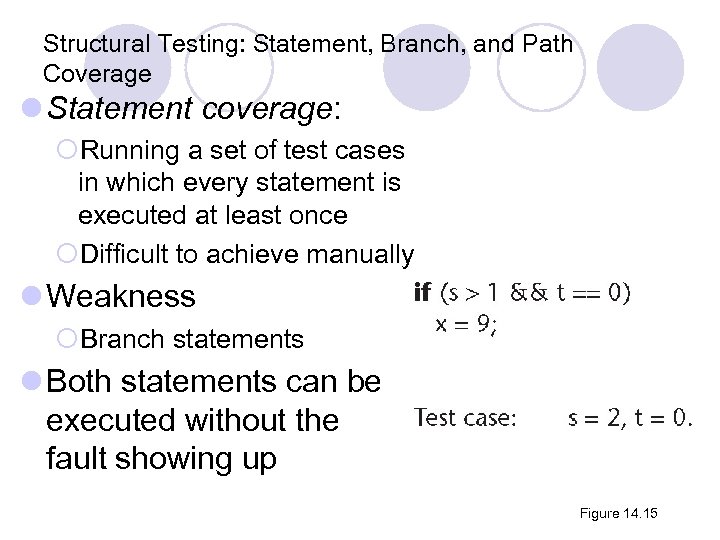

Structural Testing: Statement, Branch, and Path Coverage l Statement coverage: ¡Running a set of test cases in which every statement is executed at least once ¡Difficult to achieve manually l Weakness ¡Branch statements l Both statements can be executed without the fault showing up Figure 14. 15

Structural Testing: Statement, Branch, and Path Coverage l Statement coverage: ¡Running a set of test cases in which every statement is executed at least once ¡Difficult to achieve manually l Weakness ¡Branch statements l Both statements can be executed without the fault showing up Figure 14. 15

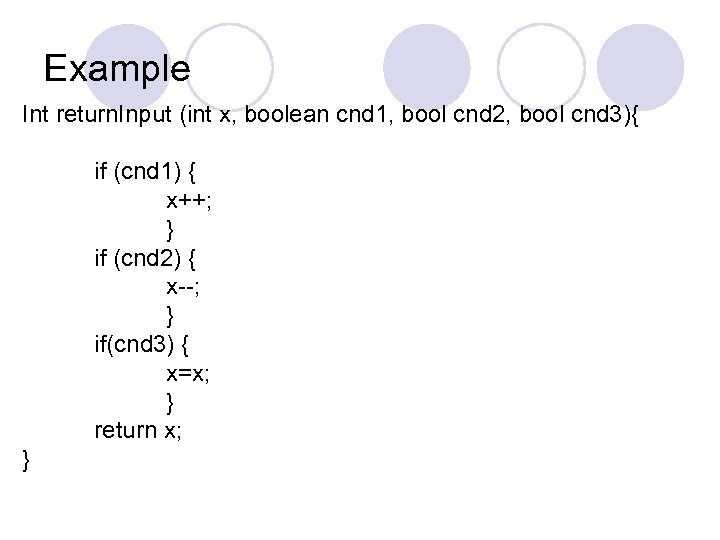

Example Int return. Input (int x, boolean cnd 1, bool cnd 2, bool cnd 3){ if (cnd 1) { x++; } if (cnd 2) { x--; } if(cnd 3) { x=x; } return x; }

Example Int return. Input (int x, boolean cnd 1, bool cnd 2, bool cnd 3){ if (cnd 1) { x++; } if (cnd 2) { x--; } if(cnd 3) { x=x; } return x; }

Exercise l Test case for statement coverage l X = 0, cnd 1=cnd 2=cnd 3=T

Exercise l Test case for statement coverage l X = 0, cnd 1=cnd 2=cnd 3=T

Structural Testing: Branch Coverage l Running a set of test cases in which every branch is executed at least once (as well as all statements) l A branch is the outcome of a decision ¡This solves the problem on the previous slide ¡Again, a CASE tool is needed as there may be many cases to test manually

Structural Testing: Branch Coverage l Running a set of test cases in which every branch is executed at least once (as well as all statements) l A branch is the outcome of a decision ¡This solves the problem on the previous slide ¡Again, a CASE tool is needed as there may be many cases to test manually

Branch coverage l Test cases ¡X = 0, cnd 1=cnd 2=cnd 3 = T ¡X = 0, cnd 1=cnd 2=cnd 3 = F

Branch coverage l Test cases ¡X = 0, cnd 1=cnd 2=cnd 3 = T ¡X = 0, cnd 1=cnd 2=cnd 3 = F

Structural Testing: Path Coverage l Running a set of test cases in which every path is executed at least once (as well as all statements) l Problem: ¡The number of paths may be very large l We want a weaker condition than all paths but that shows up more faults than branch coverage

Structural Testing: Path Coverage l Running a set of test cases in which every path is executed at least once (as well as all statements) l Problem: ¡The number of paths may be very large l We want a weaker condition than all paths but that shows up more faults than branch coverage

Path coverage l Form a basis path coverage based on the cyclomatic complexity l Test cases derived to test the basis path independently l Each new basis path “changes” exactly one previously executed decision leaving all other executed branches unchanged

Path coverage l Form a basis path coverage based on the cyclomatic complexity l Test cases derived to test the basis path independently l Each new basis path “changes” exactly one previously executed decision leaving all other executed branches unchanged

Exercise l Based on the example used in the branch coverage determine test cases for path coverage

Exercise l Based on the example used in the branch coverage determine test cases for path coverage

Linear Code Sequences and jump l Identify the set of points L from which control flow may jump, plus entry and exit points l Restrict test cases to paths that begin and end with elements of L l This uncovers many faults without testing every path

Linear Code Sequences and jump l Identify the set of points L from which control flow may jump, plus entry and exit points l Restrict test cases to paths that begin and end with elements of L l This uncovers many faults without testing every path

Linear Code Sequences and jump l the start of the linear sequence (basic block) of executable statements l the end of the linear sequence l the target line to which control flow is transferred at the end of the linear sequence.

Linear Code Sequences and jump l the start of the linear sequence (basic block) of executable statements l the end of the linear sequence l the target line to which control flow is transferred at the end of the linear sequence.

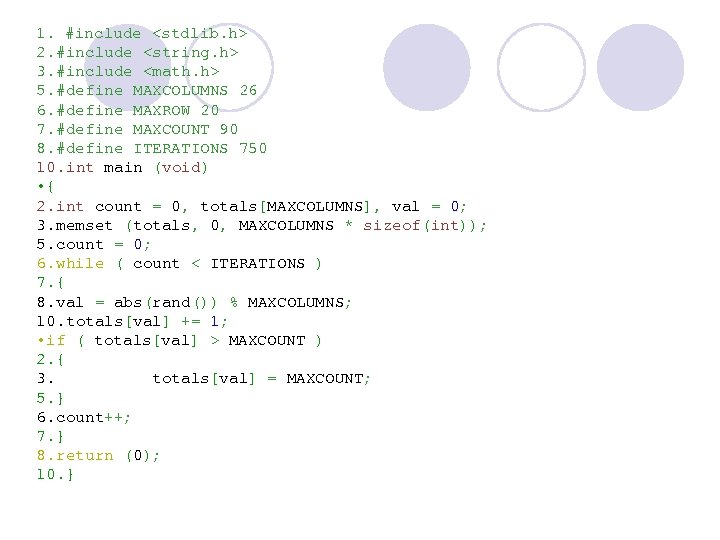

1. #include

1. #include

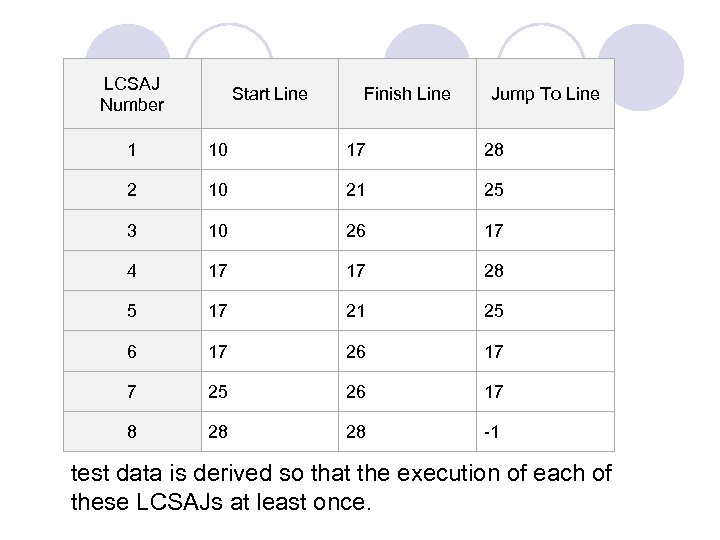

LCSAJ Number Start Line Finish Line Jump To Line 1 10 17 28 2 10 21 25 3 10 26 17 4 17 17 28 5 17 21 25 6 17 26 17 7 25 26 17 8 28 28 -1 test data is derived so that the execution of each of these LCSAJs at least once.

LCSAJ Number Start Line Finish Line Jump To Line 1 10 17 28 2 10 21 25 3 10 26 17 4 17 17 28 5 17 21 25 6 17 26 17 7 25 26 17 8 28 28 -1 test data is derived so that the execution of each of these LCSAJs at least once.

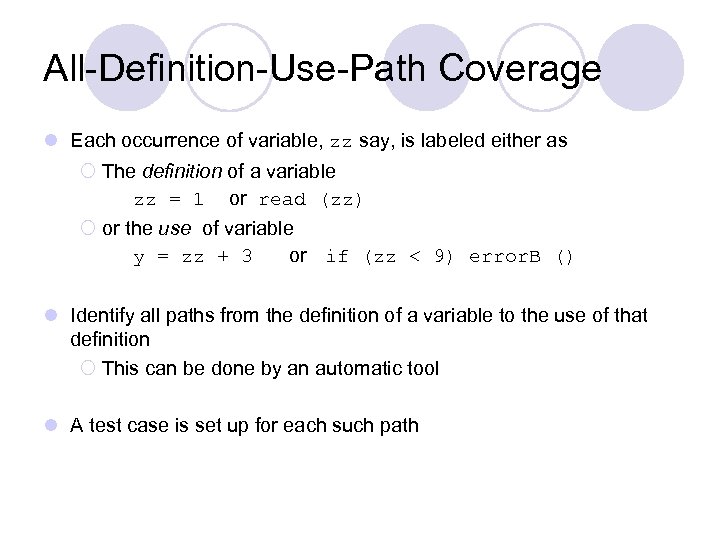

All-Definition-Use-Path Coverage l Each occurrence of variable, zz say, is labeled either as ¡ The definition of a variable zz = 1 or read (zz) ¡ or the use of variable y = zz + 3 or if (zz < 9) error. B () l Identify all paths from the definition of a variable to the use of that definition ¡ This can be done by an automatic tool l A test case is set up for each such path

All-Definition-Use-Path Coverage l Each occurrence of variable, zz say, is labeled either as ¡ The definition of a variable zz = 1 or read (zz) ¡ or the use of variable y = zz + 3 or if (zz < 9) error. B () l Identify all paths from the definition of a variable to the use of that definition ¡ This can be done by an automatic tool l A test case is set up for each such path

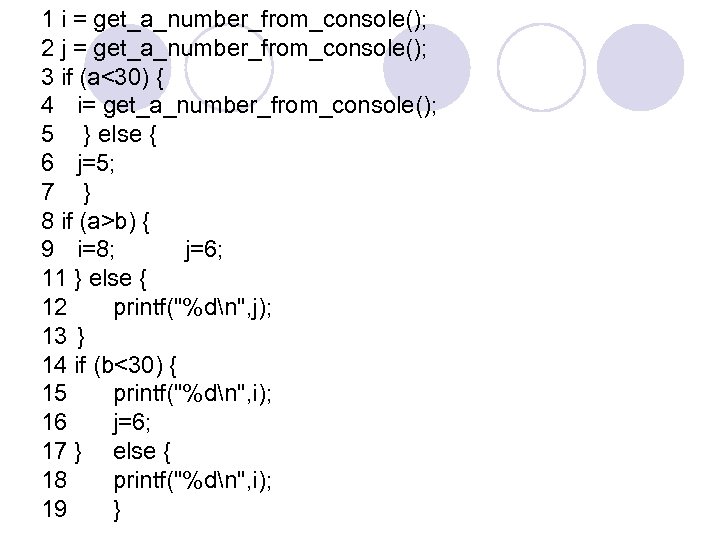

1 i = get_a_number_from_console(); 2 j = get_a_number_from_console(); 3 if (a<30) { 4 i= get_a_number_from_console(); 5 } else { 6 j=5; 7 } 8 if (a>b) { 9 i=8; j=6; 11 } else { 12 printf("%dn", j); 13 } 14 if (b<30) { 15 printf("%dn", i); 16 j=6; 17 } else { 18 printf("%dn", i); 19 }

1 i = get_a_number_from_console(); 2 j = get_a_number_from_console(); 3 if (a<30) { 4 i= get_a_number_from_console(); 5 } else { 6 j=5; 7 } 8 if (a>b) { 9 i=8; j=6; 11 } else { 12 printf("%dn", j); 13 } 14 if (b<30) { 15 printf("%dn", i); 16 j=6; 17 } else { 18 printf("%dn", i); 19 }

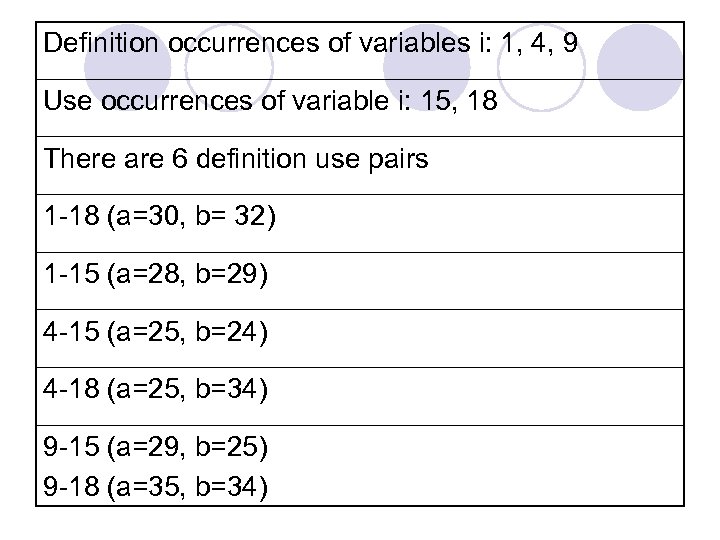

Definition occurrences of variables i: 1, 4, 9 Use occurrences of variable i: 15, 18 There are 6 definition use pairs 1 -18 (a=30, b= 32) 1 -15 (a=28, b=29) 4 -15 (a=25, b=24) 4 -18 (a=25, b=34) 9 -15 (a=29, b=25) 9 -18 (a=35, b=34)

Definition occurrences of variables i: 1, 4, 9 Use occurrences of variable i: 15, 18 There are 6 definition use pairs 1 -18 (a=30, b= 32) 1 -15 (a=28, b=29) 4 -15 (a=25, b=24) 4 -18 (a=25, b=34) 9 -15 (a=29, b=25) 9 -18 (a=35, b=34)

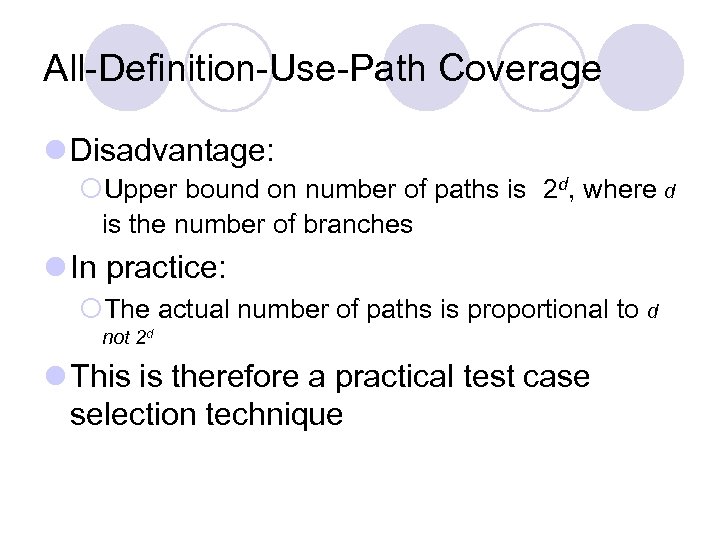

All-Definition-Use-Path Coverage l Disadvantage: ¡Upper bound on number of paths is 2 d, where d is the number of branches l In practice: ¡The actual number of paths is proportional to d not 2 d l This is therefore a practical test case selection technique

All-Definition-Use-Path Coverage l Disadvantage: ¡Upper bound on number of paths is 2 d, where d is the number of branches l In practice: ¡The actual number of paths is proportional to d not 2 d l This is therefore a practical test case selection technique

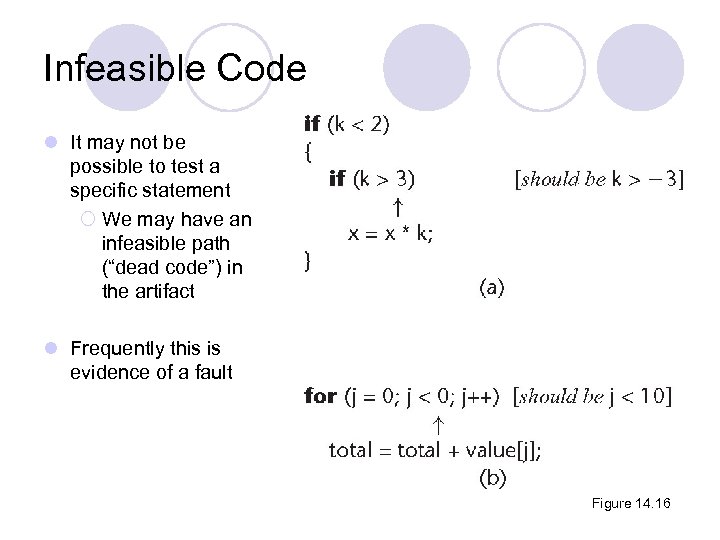

Infeasible Code l It may not be possible to test a specific statement ¡ We may have an infeasible path (“dead code”) in the artifact l Frequently this is evidence of a fault Figure 14. 16

Infeasible Code l It may not be possible to test a specific statement ¡ We may have an infeasible path (“dead code”) in the artifact l Frequently this is evidence of a fault Figure 14. 16

14. 13. 2 Complexity Metrics l A quality assurance approach to glass-box testing l Artifact m 1 is more “complex” than artifact m 2 ¡Intuitively, m 1 is more likely to have faults than artifact m 2 l If the complexity is unreasonably high, redesign and then reimplement that code artifact ¡This is cheaper and faster than trying to debug a faultprone code artifact

14. 13. 2 Complexity Metrics l A quality assurance approach to glass-box testing l Artifact m 1 is more “complex” than artifact m 2 ¡Intuitively, m 1 is more likely to have faults than artifact m 2 l If the complexity is unreasonably high, redesign and then reimplement that code artifact ¡This is cheaper and faster than trying to debug a faultprone code artifact

Lines of Code l The simplest measure of complexity ¡Underlying assumption: There is a constant probability p that a line of code contains a fault l Example ¡The tester believes each line of code has a 2% chance of containing a fault. ¡If the artifact under test is 100 lines long, then it is expected to contain 2 faults l The number of faults is indeed related to the size of the product as a whole

Lines of Code l The simplest measure of complexity ¡Underlying assumption: There is a constant probability p that a line of code contains a fault l Example ¡The tester believes each line of code has a 2% chance of containing a fault. ¡If the artifact under test is 100 lines long, then it is expected to contain 2 faults l The number of faults is indeed related to the size of the product as a whole

Other Measures of Complexity l Cyclomatic complexity M (Mc. Cabe) ¡Essentially the number of decisions (branches) in the artifact ¡Easy to compute ¡A surprisingly good measure of faults (but see next slide) l In one experiment, artifacts with M > 10 were shown to have statistically more errors per line of code

Other Measures of Complexity l Cyclomatic complexity M (Mc. Cabe) ¡Essentially the number of decisions (branches) in the artifact ¡Easy to compute ¡A surprisingly good measure of faults (but see next slide) l In one experiment, artifacts with M > 10 were shown to have statistically more errors per line of code

Problem with Complexity Metrics l Complexity metrics, as especially cyclomatic complexity, have been strongly challenged on ¡Theoretical grounds ¡Experimental grounds, and ¡Their high correlation with LOC l Essentially we are measuring lines of code, not complexity

Problem with Complexity Metrics l Complexity metrics, as especially cyclomatic complexity, have been strongly challenged on ¡Theoretical grounds ¡Experimental grounds, and ¡Their high correlation with LOC l Essentially we are measuring lines of code, not complexity

Code Walkthroughs and Inspections l Code reviews lead to rapid and thorough fault detection ¡Up to 95% reduction in maintenance costs

Code Walkthroughs and Inspections l Code reviews lead to rapid and thorough fault detection ¡Up to 95% reduction in maintenance costs

14. 15 Comparison of Unit-Testing Techniques l Experiments comparing ¡Black-box testing ¡Glass-box testing ¡Reviews - inspection l [Myers, 1978] 59 highly experienced programmers ¡All three methods were equally effective in finding faults ¡Code inspections were less cost-effective l [Hwang, 1981] ¡All three methods were equally effective

14. 15 Comparison of Unit-Testing Techniques l Experiments comparing ¡Black-box testing ¡Glass-box testing ¡Reviews - inspection l [Myers, 1978] 59 highly experienced programmers ¡All three methods were equally effective in finding faults ¡Code inspections were less cost-effective l [Hwang, 1981] ¡All three methods were equally effective

Cleanroom l A different approach to software development l Incorporates a number of different software development techniques: ¡An incremental process model ¡Formal techniques ¡Reviews l With “cleanroom” approach, a software module is not compiled until it has passed inspection (clean!!)

Cleanroom l A different approach to software development l Incorporates a number of different software development techniques: ¡An incremental process model ¡Formal techniques ¡Reviews l With “cleanroom” approach, a software module is not compiled until it has passed inspection (clean!!)

Cleanroom (contd) l Prototype automated documentation system for the U. S. Naval Underwater Systems Center l 1820 lines of Fox. BASE ¡ 18 faults were detected by “functional verification” ¡Informal proofs were used ¡ 19 faults were detected in walkthroughs before compilation ¡There were NO compilation errors ¡There were NO execution-time failures

Cleanroom (contd) l Prototype automated documentation system for the U. S. Naval Underwater Systems Center l 1820 lines of Fox. BASE ¡ 18 faults were detected by “functional verification” ¡Informal proofs were used ¡ 19 faults were detected in walkthroughs before compilation ¡There were NO compilation errors ¡There were NO execution-time failures

Cleanroom (contd) l Testing fault rate counting procedures differ: l Usual paradigms: ¡Count faults after informal testing is complete (once SQA starts) l Cleanroom ¡Count faults after inspections are complete (once compilation starts)

Cleanroom (contd) l Testing fault rate counting procedures differ: l Usual paradigms: ¡Count faults after informal testing is complete (once SQA starts) l Cleanroom ¡Count faults after inspections are complete (once compilation starts)

Report on 17 Cleanroom Products l Operating system ¡ 350, 000 LOC ¡Developed in only 18 months ¡By a team of 70 ¡The testing fault rate was only 1. 0 faults per KLOC l Various products totaling 1 million LOC ¡Weighted average testing fault rate: 2. 3 faults per KLOC l “[R]emarkable quality achievement”

Report on 17 Cleanroom Products l Operating system ¡ 350, 000 LOC ¡Developed in only 18 months ¡By a team of 70 ¡The testing fault rate was only 1. 0 faults per KLOC l Various products totaling 1 million LOC ¡Weighted average testing fault rate: 2. 3 faults per KLOC l “[R]emarkable quality achievement”

14. 18 Management Aspects of Unit Testing l We need to know when to stop testing l A number of different techniques can be used ¡Cost–benefit analysis ¡Risk analysis ¡Statistical techniques

14. 18 Management Aspects of Unit Testing l We need to know when to stop testing l A number of different techniques can be used ¡Cost–benefit analysis ¡Risk analysis ¡Statistical techniques

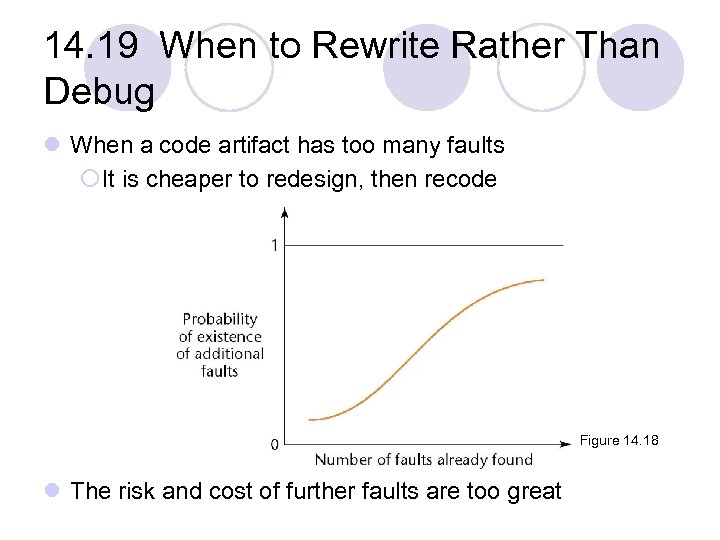

14. 19 When to Rewrite Rather Than Debug l When a code artifact has too many faults ¡It is cheaper to redesign, then recode Figure 14. 18 l The risk and cost of further faults are too great

14. 19 When to Rewrite Rather Than Debug l When a code artifact has too many faults ¡It is cheaper to redesign, then recode Figure 14. 18 l The risk and cost of further faults are too great

![Fault Distribution in Modules Is Not Uniform l [Myers, 1979] ¡ 47% of the Fault Distribution in Modules Is Not Uniform l [Myers, 1979] ¡ 47% of the](https://present5.com/presentation/9e09ba84a3100cecc1bdfab302319be7/image-87.jpg) Fault Distribution in Modules Is Not Uniform l [Myers, 1979] ¡ 47% of the faults in OS/370 were in only 4% of the modules l [Endres, 1975] ¡ 512 faults in 202 modules of DOS/VS (Release 28) ¡ 112 of the modules had only one fault ¡ There were modules with 14, 15, 19 and 28 faults, respectively ¡ The latter three were the largest modules in the product, with over 3000 lines of DOS macro assembler language ¡ The module with 14 faults was relatively small, and very unstable ¡ A prime candidate for discarding, redesigning, recoding

Fault Distribution in Modules Is Not Uniform l [Myers, 1979] ¡ 47% of the faults in OS/370 were in only 4% of the modules l [Endres, 1975] ¡ 512 faults in 202 modules of DOS/VS (Release 28) ¡ 112 of the modules had only one fault ¡ There were modules with 14, 15, 19 and 28 faults, respectively ¡ The latter three were the largest modules in the product, with over 3000 lines of DOS macro assembler language ¡ The module with 14 faults was relatively small, and very unstable ¡ A prime candidate for discarding, redesigning, recoding

When to Rewrite Rather Than Debug (contd) l For every artifact, management must predetermine the maximum allowed number of faults during testing l If this number is reached ¡ Discard ¡ Redesign ¡ Recode l The maximum number of faults allowed after delivery is ZERO

When to Rewrite Rather Than Debug (contd) l For every artifact, management must predetermine the maximum allowed number of faults during testing l If this number is reached ¡ Discard ¡ Redesign ¡ Recode l The maximum number of faults allowed after delivery is ZERO

14. 21 Product Testing l Product testing for COTS (commercial offthe-shelf ) software ¡Alpha, beta testing l Product testing for custom software ¡The SQA group must ensure that the product passes the acceptance test (performed by the client) ¡Failing an acceptance test has bad consequences for the development organization

14. 21 Product Testing l Product testing for COTS (commercial offthe-shelf ) software ¡Alpha, beta testing l Product testing for custom software ¡The SQA group must ensure that the product passes the acceptance test (performed by the client) ¡Failing an acceptance test has bad consequences for the development organization

Product Testing for Custom Software l The SQA team must try to approximate the acceptance test ¡Black box test cases for the product as a whole ¡Robustness of product as a whole l. Stress testing (under peak load) l. Volume testing (e. g. , can it handle large input files? ) ¡All constraints must be checked ¡All documentation must be l. Checked for correctness l. Checked for conformity with standards l. Verified against the current version of the product

Product Testing for Custom Software l The SQA team must try to approximate the acceptance test ¡Black box test cases for the product as a whole ¡Robustness of product as a whole l. Stress testing (under peak load) l. Volume testing (e. g. , can it handle large input files? ) ¡All constraints must be checked ¡All documentation must be l. Checked for correctness l. Checked for conformity with standards l. Verified against the current version of the product

Product Testing for Custom Software (contd) l The product (code plus documentation) is now handed over to the client organization for acceptance testing

Product Testing for Custom Software (contd) l The product (code plus documentation) is now handed over to the client organization for acceptance testing

14. 22 Acceptance Testing l The client determines whether the product satisfies its specifications l Acceptance testing is performed by ¡The client organization, or ¡The SQA team in the presence of client representatives, or ¡An independent SQA team hired by the client

14. 22 Acceptance Testing l The client determines whether the product satisfies its specifications l Acceptance testing is performed by ¡The client organization, or ¡The SQA team in the presence of client representatives, or ¡An independent SQA team hired by the client

Acceptance Testing (contd) l The four major components of acceptance testing are ¡Correctness ¡Robustness ¡Performance ¡Documentation l These are precisely what was tested by the developer during product testing

Acceptance Testing (contd) l The four major components of acceptance testing are ¡Correctness ¡Robustness ¡Performance ¡Documentation l These are precisely what was tested by the developer during product testing

Acceptance Testing (contd) l The key difference between product testing and acceptance testing is ¡Acceptance testing is performed on actual data ¡Product testing is preformed on test data, which can never be real, by definition

Acceptance Testing (contd) l The key difference between product testing and acceptance testing is ¡Acceptance testing is performed on actual data ¡Product testing is preformed on test data, which can never be real, by definition

14. 25 Metrics for the Implementation Workflow l Complexity metrics, fault per KLOC l Fault statistics are important ¡Number of test cases ¡Percentage of test cases that resulted in failure ¡Total number of faults, by types l The fault data are incorporated into checklists for code inspections

14. 25 Metrics for the Implementation Workflow l Complexity metrics, fault per KLOC l Fault statistics are important ¡Number of test cases ¡Percentage of test cases that resulted in failure ¡Total number of faults, by types l The fault data are incorporated into checklists for code inspections

14. 26 Challenges of the Implementation Workflow l Management issues are paramount here ¡Appropriate CASE tools ¡Test case planning ¡Communicating changes to all personnel ¡Deciding when to stop testing

14. 26 Challenges of the Implementation Workflow l Management issues are paramount here ¡Appropriate CASE tools ¡Test case planning ¡Communicating changes to all personnel ¡Deciding when to stop testing

Challenges of the Implementation Workflow (contd) l Code reuse can reduce time and cost during implementation, but l Code reuse needs to be built into the product from the very beginning ¡The software project management plan must incorporate reuse l Implementation is technically straightforward if previous phases such as requirements, analysis were carried out satisfactorily.

Challenges of the Implementation Workflow (contd) l Code reuse can reduce time and cost during implementation, but l Code reuse needs to be built into the product from the very beginning ¡The software project management plan must incorporate reuse l Implementation is technically straightforward if previous phases such as requirements, analysis were carried out satisfactorily.

Challenges of the Implementation Phase (contd) l Make-or-break issues (成敗的關鍵) include: ¡Use of appropriate CASE tools ¡Test planning as soon as the client has signed off the specifications ¡Ensuring that changes are communicated to all relevant personnel ¡Deciding when to stop testing

Challenges of the Implementation Phase (contd) l Make-or-break issues (成敗的關鍵) include: ¡Use of appropriate CASE tools ¡Test planning as soon as the client has signed off the specifications ¡Ensuring that changes are communicated to all relevant personnel ¡Deciding when to stop testing