Immunophysiology of renal system.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 28

Immunophysiology of renal system

Immunophysiology of renal system

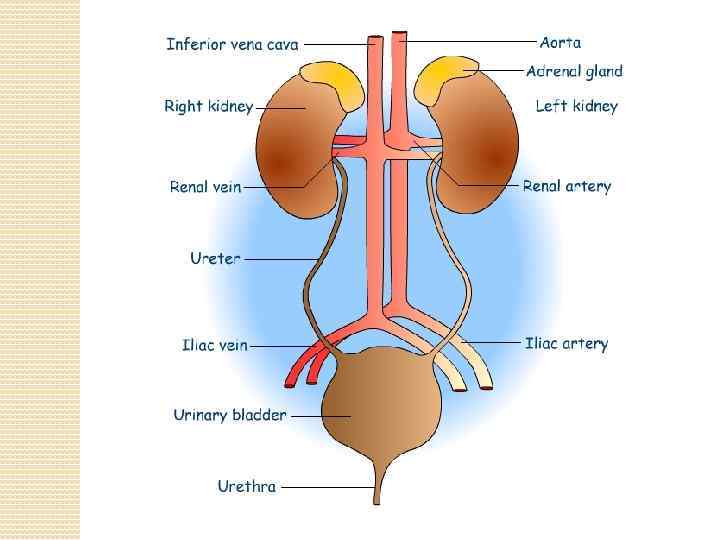

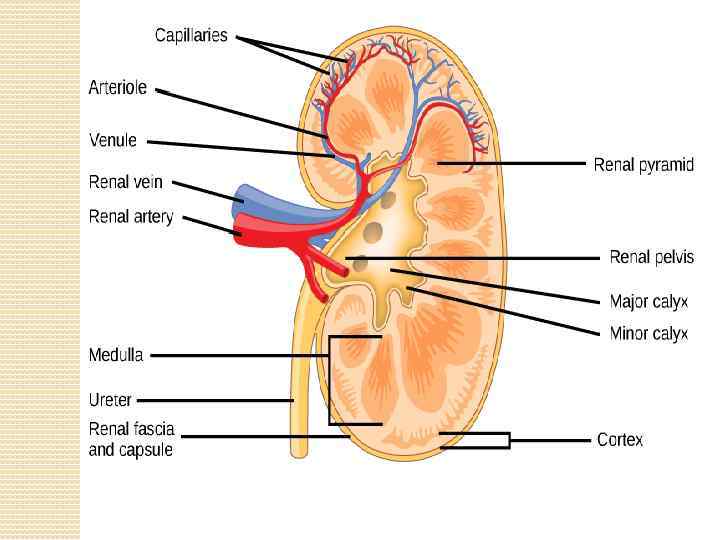

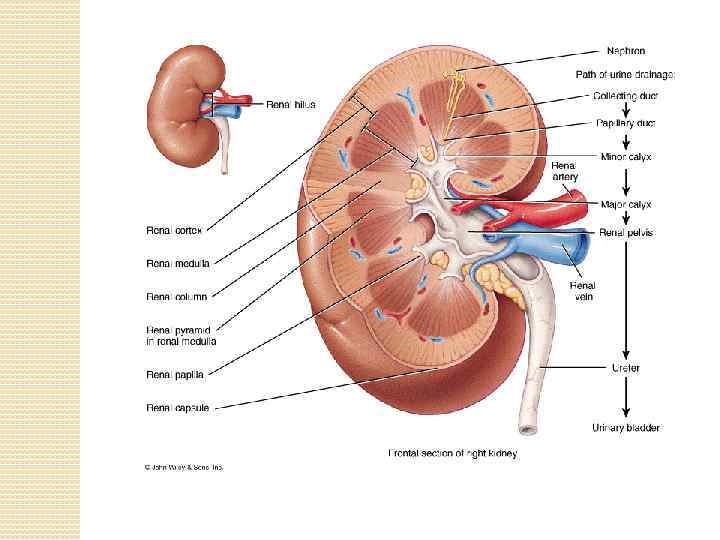

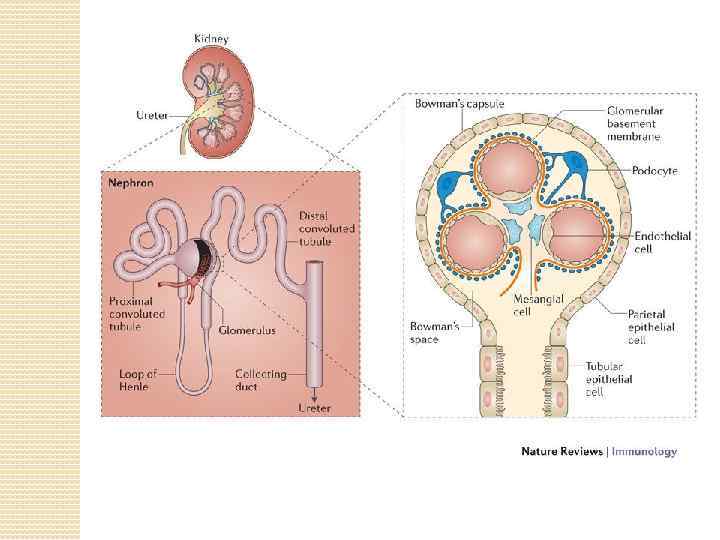

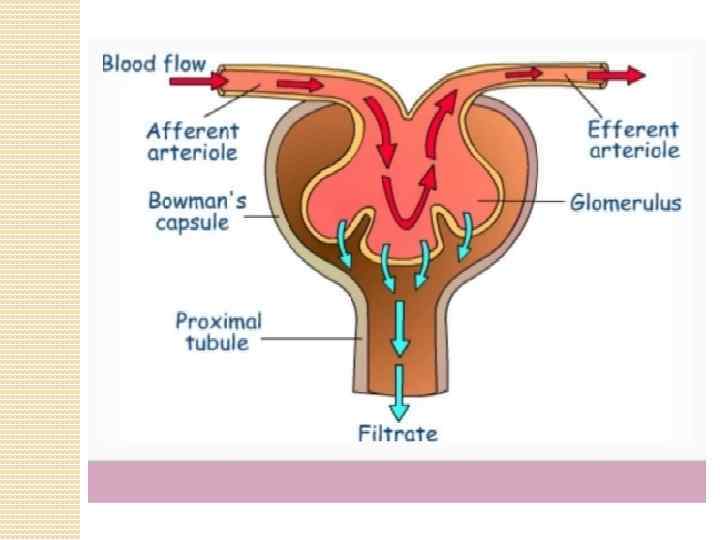

The kidneys purify toxic metabolic waste products from the blood in several hundred thousand functionally independent units called nephrons. A nephron consists of one glomerulus and one double hairpin-shaped tubule that drains the filtrate into the renal pelvis. The glomeruli located in the kidney cortex are bordered by the Bowman's capsule. They are lined with parietal epithelial cells and contain the mesangium with many capillaries to filter the blood. The glomerular filtration barrier consists of endothelial cells, the glomerular basement membrane and visceral epithelial cells (also known as podocytes). All molecules below the molecular size of albumin (that is, 68 k. Da) pass the filter and enter the tubule, which consists of the proximal convoluted tubule, the loop of Henle and the distal convoluted tubule. An intricate countercurrent (противоточная) system forms a high osmotic gradient in the renal medulla that concentrates the filtrate. The tubular epithelial cells reabsorb water, small proteins, amino acids, carbohydrates and electrolytes, thereby regulating plasma osmolality, extracellular volume, blood pressure and acid–base and electrolyte balance. Non-reabsorbed compounds pass from the tubular system into the collecting ducts to form urine. The space between the tubules is called the interstitium and contains most of the intrarenal immune system, which mainly consists of dendritic cells, but also of macrophages and fibroblasts.

The kidneys purify toxic metabolic waste products from the blood in several hundred thousand functionally independent units called nephrons. A nephron consists of one glomerulus and one double hairpin-shaped tubule that drains the filtrate into the renal pelvis. The glomeruli located in the kidney cortex are bordered by the Bowman's capsule. They are lined with parietal epithelial cells and contain the mesangium with many capillaries to filter the blood. The glomerular filtration barrier consists of endothelial cells, the glomerular basement membrane and visceral epithelial cells (also known as podocytes). All molecules below the molecular size of albumin (that is, 68 k. Da) pass the filter and enter the tubule, which consists of the proximal convoluted tubule, the loop of Henle and the distal convoluted tubule. An intricate countercurrent (противоточная) system forms a high osmotic gradient in the renal medulla that concentrates the filtrate. The tubular epithelial cells reabsorb water, small proteins, amino acids, carbohydrates and electrolytes, thereby regulating plasma osmolality, extracellular volume, blood pressure and acid–base and electrolyte balance. Non-reabsorbed compounds pass from the tubular system into the collecting ducts to form urine. The space between the tubules is called the interstitium and contains most of the intrarenal immune system, which mainly consists of dendritic cells, but also of macrophages and fibroblasts.

The kidneys produce several hormones that directly or indirectly affect immune responses, including vitamin D, which regulates bone homeostasis and phagocyte function, erythropoietin, which is induced in response to hypoxia to regulate erythropoiesis, and renin, which induces angiotensin and aldosterone to regulate electrolyte balance, extracellular osmolarity and blood pressure.

The kidneys produce several hormones that directly or indirectly affect immune responses, including vitamin D, which regulates bone homeostasis and phagocyte function, erythropoietin, which is induced in response to hypoxia to regulate erythropoiesis, and renin, which induces angiotensin and aldosterone to regulate electrolyte balance, extracellular osmolarity and blood pressure.

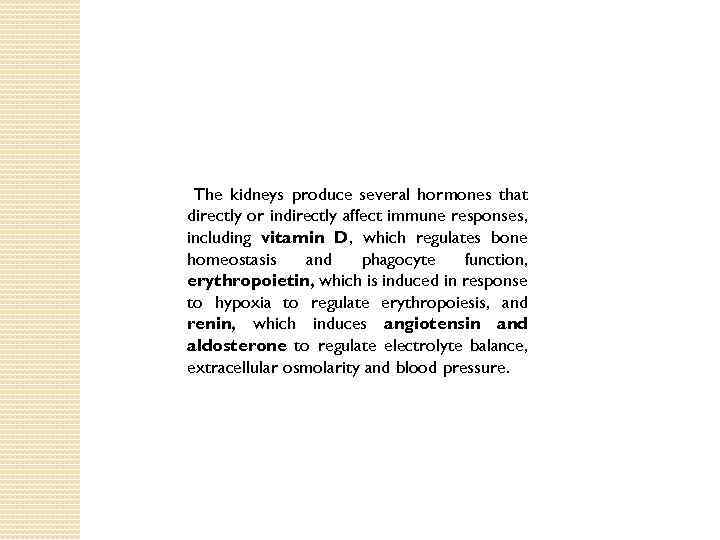

Vitamin D regulates the innate and adaptive immune response to a pathogenic challenge. Abbreviations: DC, dendritic cell; MØ, macrophage; TH, T-helper cell; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TREG, T regulatory cell.

Vitamin D regulates the innate and adaptive immune response to a pathogenic challenge. Abbreviations: DC, dendritic cell; MØ, macrophage; TH, T-helper cell; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TREG, T regulatory cell.

Renal tubular epithelial cells (TECs) play an active role in renal inflammation. Previous studies have demonstrated the capacity of TECs to modulate T-cell responses both positively and negatively. Recently, new costimulatory molecules [inducible T cell costimulator-L (ICOS-L) and B 7 - H 1] have been described, which appear to be involved in peripheral T-cell activation. Interaction of tubular epithelial cells and kidney infiltrating T cells via ICOS-L and B 7 -H 1 may change the balance of positive and negative signals to the T cells, leading to IL-10 production and limitation of local immune responses. Interaction of TECs with T cells favors interleukin (IL)-10 production and reduces interferon (IFN)-c production, indicating that TECs may alter the effector function of T cells in renal inflammation. The TECs exert immunosuppressive effects on CD 4+ and CD 8+ T cell proliferation and lead to enhanced T cell apoptosis. This would mean that, in the renal microenvironment, T cells in contact with the TEC barrier are exposed to more inactivation and death by TECs. Infiltrating T cells in the renal interstitial compartment will still be able to mount effective immune responses against alloantigens. Moreover, TECs could also induce regulatory CD 4+ T cells being able to inhibit the proliferation of other immune cells. Parenchymal cells have been shown to exert their immunosuppressive effects in a cell–cell contact-dependent manner, as supernatant experiments did not reveal any inhibitory effect.

Renal tubular epithelial cells (TECs) play an active role in renal inflammation. Previous studies have demonstrated the capacity of TECs to modulate T-cell responses both positively and negatively. Recently, new costimulatory molecules [inducible T cell costimulator-L (ICOS-L) and B 7 - H 1] have been described, which appear to be involved in peripheral T-cell activation. Interaction of tubular epithelial cells and kidney infiltrating T cells via ICOS-L and B 7 -H 1 may change the balance of positive and negative signals to the T cells, leading to IL-10 production and limitation of local immune responses. Interaction of TECs with T cells favors interleukin (IL)-10 production and reduces interferon (IFN)-c production, indicating that TECs may alter the effector function of T cells in renal inflammation. The TECs exert immunosuppressive effects on CD 4+ and CD 8+ T cell proliferation and lead to enhanced T cell apoptosis. This would mean that, in the renal microenvironment, T cells in contact with the TEC barrier are exposed to more inactivation and death by TECs. Infiltrating T cells in the renal interstitial compartment will still be able to mount effective immune responses against alloantigens. Moreover, TECs could also induce regulatory CD 4+ T cells being able to inhibit the proliferation of other immune cells. Parenchymal cells have been shown to exert their immunosuppressive effects in a cell–cell contact-dependent manner, as supernatant experiments did not reveal any inhibitory effect.

Proximal tubule epithelial cells (PTEC) of the kidney line the proximal tubule downstream of the glomerulus and play a major role in the re-absorption of small molecular weight proteins that may pass through the glomerular filtration process. In the perturbed disease state PTEC also contribute to the inflammatory disease process via both positive and negative mechanisms via the production of inflammatory cytokines which chemo-attract leukocytes and the subsequent downmodulation of these cells to prevent uncontrolled inflammatory responses. It is well established that dendritic cells are responsible for the initiation and direction of adaptive immune responses. Both resident and infiltrating dendritic cells are localised within the tubulointerstitium of the renal cortex, in close apposition to PTEC, in inflammatory disease states. Primary human PTEC are able to modulate autologous DC phenotype and function via multiple complex pathways. The presence of autologous PTEC skew Mo. DC to become phenotypically less mature and functionally less stimulatory.

Proximal tubule epithelial cells (PTEC) of the kidney line the proximal tubule downstream of the glomerulus and play a major role in the re-absorption of small molecular weight proteins that may pass through the glomerular filtration process. In the perturbed disease state PTEC also contribute to the inflammatory disease process via both positive and negative mechanisms via the production of inflammatory cytokines which chemo-attract leukocytes and the subsequent downmodulation of these cells to prevent uncontrolled inflammatory responses. It is well established that dendritic cells are responsible for the initiation and direction of adaptive immune responses. Both resident and infiltrating dendritic cells are localised within the tubulointerstitium of the renal cortex, in close apposition to PTEC, in inflammatory disease states. Primary human PTEC are able to modulate autologous DC phenotype and function via multiple complex pathways. The presence of autologous PTEC skew Mo. DC to become phenotypically less mature and functionally less stimulatory.

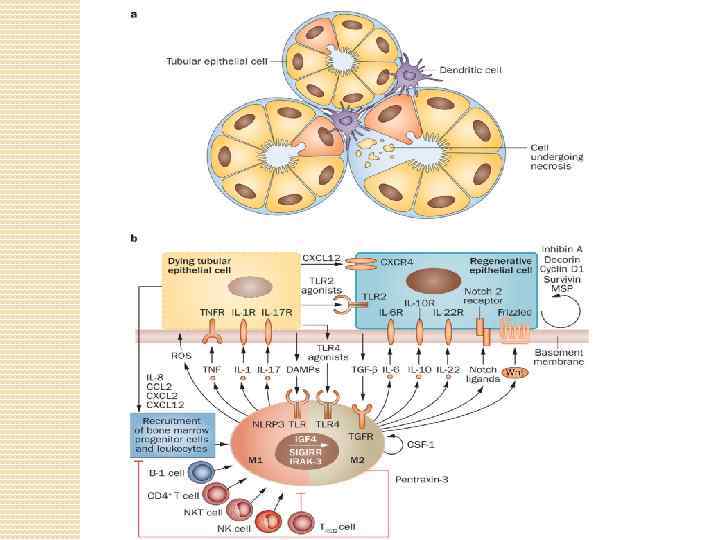

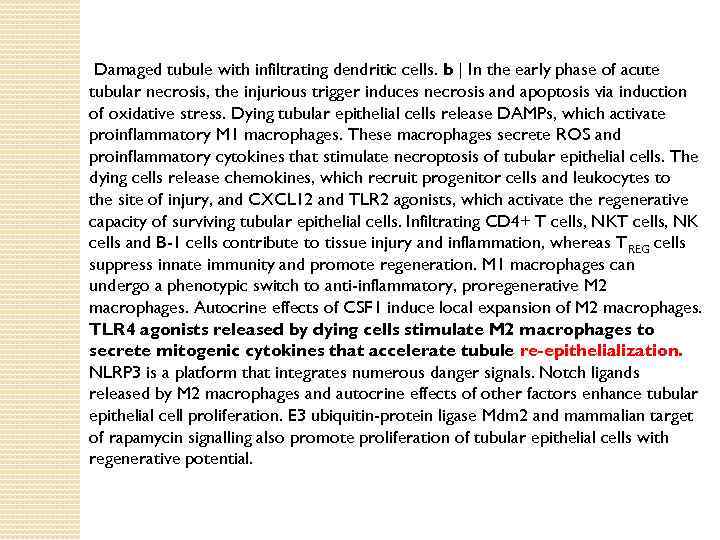

Damaged tubule with infiltrating dendritic cells. b | In the early phase of acute tubular necrosis, the injurious trigger induces necrosis and apoptosis via induction of oxidative stress. Dying tubular epithelial cells release DAMPs, which activate proinflammatory M 1 macrophages. These macrophages secrete ROS and proinflammatory cytokines that stimulate necroptosis of tubular epithelial cells. The dying cells release chemokines, which recruit progenitor cells and leukocytes to the site of injury, and CXCL 12 and TLR 2 agonists, which activate the regenerative capacity of surviving tubular epithelial cells. Infiltrating CD 4+ T cells, NK cells and B-1 cells contribute to tissue injury and inflammation, whereas T REG cells suppress innate immunity and promote regeneration. M 1 macrophages can undergo a phenotypic switch to anti-inflammatory, proregenerative M 2 macrophages. Autocrine effects of CSF 1 induce local expansion of M 2 macrophages. TLR 4 agonists released by dying cells stimulate M 2 macrophages to secrete mitogenic cytokines that accelerate tubule re-epithelialization. NLRP 3 is a platform that integrates numerous danger signals. Notch ligands released by M 2 macrophages and autocrine effects of other factors enhance tubular epithelial cell proliferation. E 3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Mdm 2 and mammalian target of rapamycin signalling also promote proliferation of tubular epithelial cells with regenerative potential.

Damaged tubule with infiltrating dendritic cells. b | In the early phase of acute tubular necrosis, the injurious trigger induces necrosis and apoptosis via induction of oxidative stress. Dying tubular epithelial cells release DAMPs, which activate proinflammatory M 1 macrophages. These macrophages secrete ROS and proinflammatory cytokines that stimulate necroptosis of tubular epithelial cells. The dying cells release chemokines, which recruit progenitor cells and leukocytes to the site of injury, and CXCL 12 and TLR 2 agonists, which activate the regenerative capacity of surviving tubular epithelial cells. Infiltrating CD 4+ T cells, NK cells and B-1 cells contribute to tissue injury and inflammation, whereas T REG cells suppress innate immunity and promote regeneration. M 1 macrophages can undergo a phenotypic switch to anti-inflammatory, proregenerative M 2 macrophages. Autocrine effects of CSF 1 induce local expansion of M 2 macrophages. TLR 4 agonists released by dying cells stimulate M 2 macrophages to secrete mitogenic cytokines that accelerate tubule re-epithelialization. NLRP 3 is a platform that integrates numerous danger signals. Notch ligands released by M 2 macrophages and autocrine effects of other factors enhance tubular epithelial cell proliferation. E 3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Mdm 2 and mammalian target of rapamycin signalling also promote proliferation of tubular epithelial cells with regenerative potential.

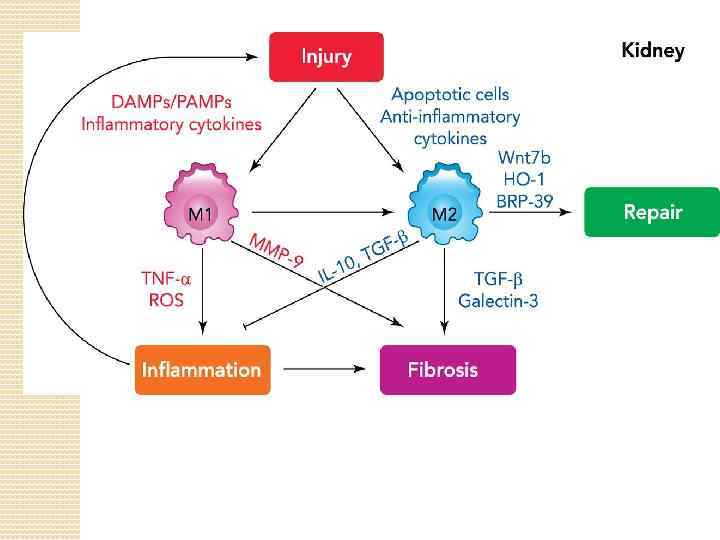

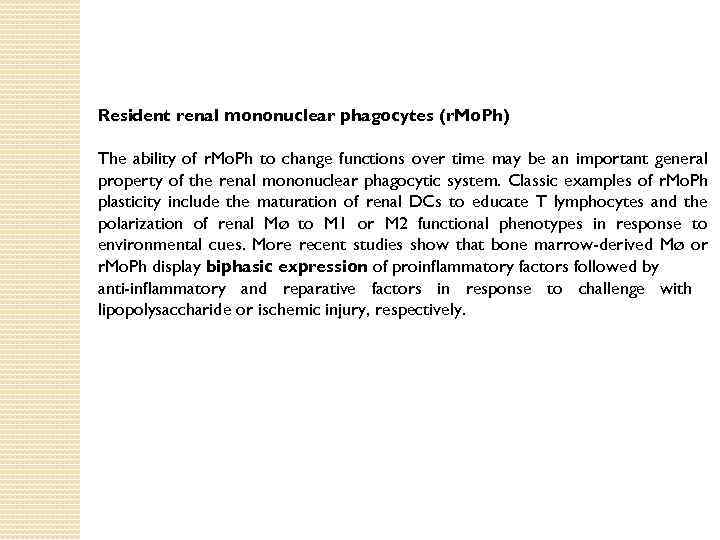

Resident renal mononuclear phagocytes (r. Mo. Ph) The ability of r. Mo. Ph to change functions over time may be an important general property of the renal mononuclear phagocytic system. Classic examples of r. Mo. Ph plasticity include the maturation of renal DCs to educate T lymphocytes and the polarization of renal Mø to M 1 or M 2 functional phenotypes in response to environmental cues. More recent studies show that bone marrow-derived Mø or r. Mo. Ph display biphasic expression of proinflammatory factors followed by anti-inflammatory and reparative factors in response to challenge with lipopolysaccharide or ischemic injury, respectively.

Resident renal mononuclear phagocytes (r. Mo. Ph) The ability of r. Mo. Ph to change functions over time may be an important general property of the renal mononuclear phagocytic system. Classic examples of r. Mo. Ph plasticity include the maturation of renal DCs to educate T lymphocytes and the polarization of renal Mø to M 1 or M 2 functional phenotypes in response to environmental cues. More recent studies show that bone marrow-derived Mø or r. Mo. Ph display biphasic expression of proinflammatory factors followed by anti-inflammatory and reparative factors in response to challenge with lipopolysaccharide or ischemic injury, respectively.

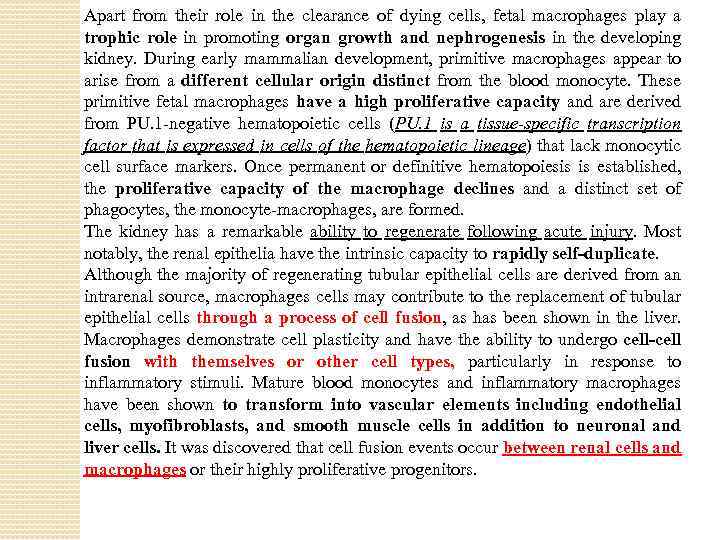

Apart from their role in the clearance of dying cells, fetal macrophages play a trophic role in promoting organ growth and nephrogenesis in the developing kidney. During early mammalian development, primitive macrophages appear to arise from a different cellular origin distinct from the blood monocyte. These primitive fetal macrophages have a high proliferative capacity and are derived from PU. 1 -negative hematopoietic cells (PU. 1 is a tissue-specific transcription factor that is expressed in cells of the hematopoietic lineage) that lack monocytic cell surface markers. Once permanent or definitive hematopoiesis is established, the proliferative capacity of the macrophage declines and a distinct set of phagocytes, the monocyte-macrophages, are formed. The kidney has a remarkable ability to regenerate following acute injury. Most notably, the renal epithelia have the intrinsic capacity to rapidly self-duplicate. Although the majority of regenerating tubular epithelial cells are derived from an intrarenal source, macrophages cells may contribute to the replacement of tubular epithelial cells through a process of cell fusion, as has been shown in the liver. Macrophages demonstrate cell plasticity and have the ability to undergo cell-cell fusion with themselves or other cell types, particularly in response to inflammatory stimuli. Mature blood monocytes and inflammatory macrophages have been shown to transform into vascular elements including endothelial cells, myofibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells in addition to neuronal and liver cells. It was discovered that cell fusion events occur between renal cells and macrophages or their highly proliferative progenitors.

Apart from their role in the clearance of dying cells, fetal macrophages play a trophic role in promoting organ growth and nephrogenesis in the developing kidney. During early mammalian development, primitive macrophages appear to arise from a different cellular origin distinct from the blood monocyte. These primitive fetal macrophages have a high proliferative capacity and are derived from PU. 1 -negative hematopoietic cells (PU. 1 is a tissue-specific transcription factor that is expressed in cells of the hematopoietic lineage) that lack monocytic cell surface markers. Once permanent or definitive hematopoiesis is established, the proliferative capacity of the macrophage declines and a distinct set of phagocytes, the monocyte-macrophages, are formed. The kidney has a remarkable ability to regenerate following acute injury. Most notably, the renal epithelia have the intrinsic capacity to rapidly self-duplicate. Although the majority of regenerating tubular epithelial cells are derived from an intrarenal source, macrophages cells may contribute to the replacement of tubular epithelial cells through a process of cell fusion, as has been shown in the liver. Macrophages demonstrate cell plasticity and have the ability to undergo cell-cell fusion with themselves or other cell types, particularly in response to inflammatory stimuli. Mature blood monocytes and inflammatory macrophages have been shown to transform into vascular elements including endothelial cells, myofibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells in addition to neuronal and liver cells. It was discovered that cell fusion events occur between renal cells and macrophages or their highly proliferative progenitors.

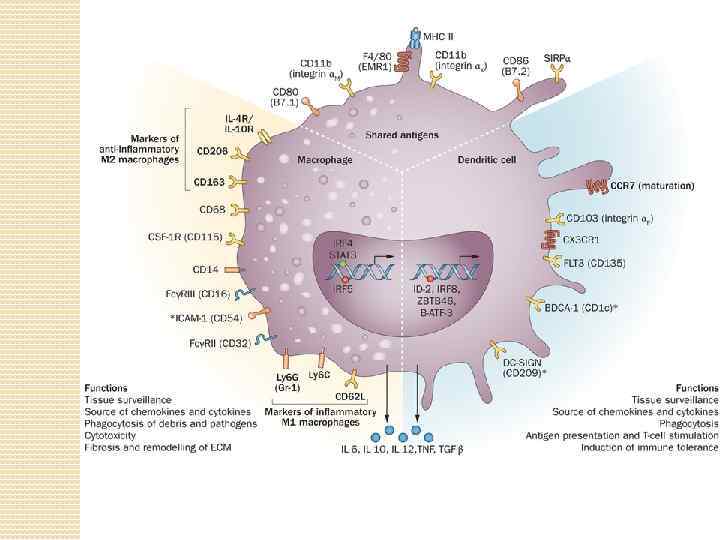

Under homeostatic conditions, the resident immune cells of the kidneys include dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages, as well as a few lymphocytes. DCs are restricted to the tubulointerstitium and are absent from the glomeruli. Macrophages are preferentially found in the renal medulla and capsule and have homeostatic and repair functions. The heterogeneous but overlapping phenotype and functions of renal DCs and macrophages. DCs are traditionally described as mediators of immune surveillance and antigen presentation, and as the primary determinants of responses to antigens—through initiation of either immune effector-cell functions or the development of tolerance. Macrophages also function as innate immune cells, predominantly through phagocytosis and production of toxic metabolites. However, the classical paradigm of DC versus macrophage phenotypes and functions is increasingly indistinct within the kidney, as these cells exhibit overlapping surface markers, functional capabilities, and ontogenic pathways. This molecular and phenotypic overlap between cell types and subsets complicates their identification and evaluation. Renal DCs and macrophages are phenotypically and functionally heterogeneous cells that regulate tissue responses to renal injury and disease. The considerable overlap between DCs and macrophages represents a continuum of phenotype, as well as plasticity of cells of the myeloid–monocytic lineage both in vivo and in vitro.

Under homeostatic conditions, the resident immune cells of the kidneys include dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages, as well as a few lymphocytes. DCs are restricted to the tubulointerstitium and are absent from the glomeruli. Macrophages are preferentially found in the renal medulla and capsule and have homeostatic and repair functions. The heterogeneous but overlapping phenotype and functions of renal DCs and macrophages. DCs are traditionally described as mediators of immune surveillance and antigen presentation, and as the primary determinants of responses to antigens—through initiation of either immune effector-cell functions or the development of tolerance. Macrophages also function as innate immune cells, predominantly through phagocytosis and production of toxic metabolites. However, the classical paradigm of DC versus macrophage phenotypes and functions is increasingly indistinct within the kidney, as these cells exhibit overlapping surface markers, functional capabilities, and ontogenic pathways. This molecular and phenotypic overlap between cell types and subsets complicates their identification and evaluation. Renal DCs and macrophages are phenotypically and functionally heterogeneous cells that regulate tissue responses to renal injury and disease. The considerable overlap between DCs and macrophages represents a continuum of phenotype, as well as plasticity of cells of the myeloid–monocytic lineage both in vivo and in vitro.

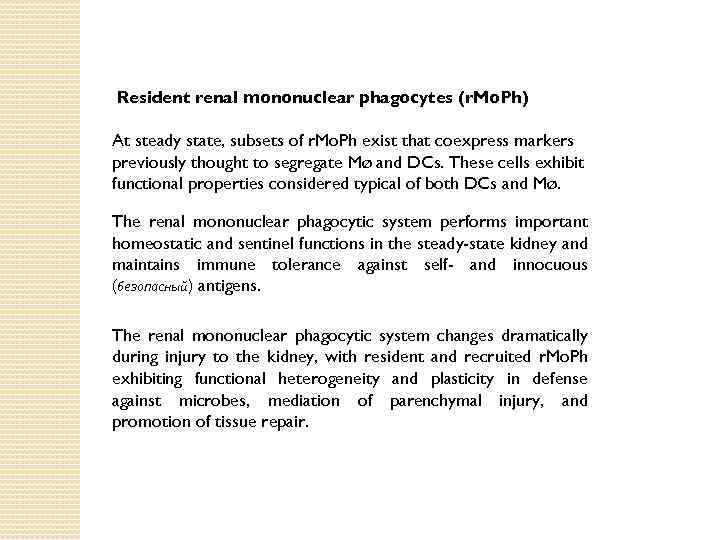

Resident renal mononuclear phagocytes (r. Mo. Ph) At steady state, subsets of r. Mo. Ph exist that coexpress markers previously thought to segregate Mø and DCs. These cells exhibit functional properties considered typical of both DCs and Mø. The renal mononuclear phagocytic system performs important homeostatic and sentinel functions in the steady-state kidney and maintains immune tolerance against self- and innocuous (безопасный) antigens. The renal mononuclear phagocytic system changes dramatically during injury to the kidney, with resident and recruited r. Mo. Ph exhibiting functional heterogeneity and plasticity in defense against microbes, mediation of parenchymal injury, and promotion of tissue repair.

Resident renal mononuclear phagocytes (r. Mo. Ph) At steady state, subsets of r. Mo. Ph exist that coexpress markers previously thought to segregate Mø and DCs. These cells exhibit functional properties considered typical of both DCs and Mø. The renal mononuclear phagocytic system performs important homeostatic and sentinel functions in the steady-state kidney and maintains immune tolerance against self- and innocuous (безопасный) antigens. The renal mononuclear phagocytic system changes dramatically during injury to the kidney, with resident and recruited r. Mo. Ph exhibiting functional heterogeneity and plasticity in defense against microbes, mediation of parenchymal injury, and promotion of tissue repair.

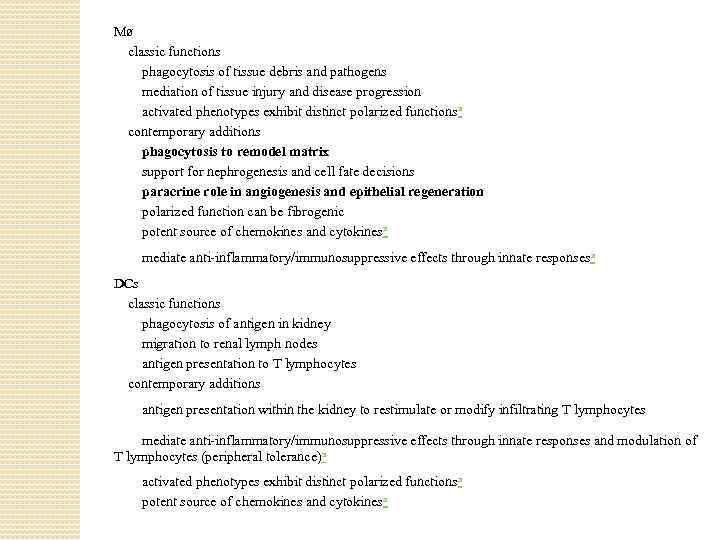

Mø classic functions phagocytosis of tissue debris and pathogens mediation of tissue injury and disease progression activated phenotypes exhibit distinct polarized functionsa contemporary additions phagocytosis to remodel matrix support for nephrogenesis and cell fate decisions paracrine role in angiogenesis and epithelial regeneration polarized function can be fibrogenic potent source of chemokines and cytokinesa mediate anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive effects through innate responsesa DCs classic functions phagocytosis of antigen in kidney migration to renal lymph nodes antigen presentation to T lymphocytes contemporary additions antigen presentation within the kidney to restimulate or modify infiltrating T lymphocytes mediate anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive effects through innate responses and modulation of T lymphocytes (peripheral tolerance)a activated phenotypes exhibit distinct polarized functionsa potent source of chemokines and cytokinesa

Mø classic functions phagocytosis of tissue debris and pathogens mediation of tissue injury and disease progression activated phenotypes exhibit distinct polarized functionsa contemporary additions phagocytosis to remodel matrix support for nephrogenesis and cell fate decisions paracrine role in angiogenesis and epithelial regeneration polarized function can be fibrogenic potent source of chemokines and cytokinesa mediate anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive effects through innate responsesa DCs classic functions phagocytosis of antigen in kidney migration to renal lymph nodes antigen presentation to T lymphocytes contemporary additions antigen presentation within the kidney to restimulate or modify infiltrating T lymphocytes mediate anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive effects through innate responses and modulation of T lymphocytes (peripheral tolerance)a activated phenotypes exhibit distinct polarized functionsa potent source of chemokines and cytokinesa

‘Summary at a glance’: functions of DCs 1. Renal dendritic cells (r. DCs) have homeostatic roles, such as inducing immune tolerance against small innocuous antigens or crosstalk with tubular epithelial cells. 2. r. DCs form an extensive surveillance network in the kidney tubulointerstitium, alerting to infections/injury. 3. r. DCs may exacerbate acute non-immune kidney injury (e. g. , ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI) or unilateral ureter obstruction (UUO)) by inducing harmful immune effector mechanisms. 4. r. DCs have protective anti-inflammatory roles in acute GN, but may acquire injurious pro-inflammatory properties in chronic renal inflammation.

‘Summary at a glance’: functions of DCs 1. Renal dendritic cells (r. DCs) have homeostatic roles, such as inducing immune tolerance against small innocuous antigens or crosstalk with tubular epithelial cells. 2. r. DCs form an extensive surveillance network in the kidney tubulointerstitium, alerting to infections/injury. 3. r. DCs may exacerbate acute non-immune kidney injury (e. g. , ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI) or unilateral ureter obstruction (UUO)) by inducing harmful immune effector mechanisms. 4. r. DCs have protective anti-inflammatory roles in acute GN, but may acquire injurious pro-inflammatory properties in chronic renal inflammation.

major challenges facing the field in the near future 1. Current definitions of renal dendritic cells (r. DCs) and macrophages overlap. Reach consensus on phenotype, functionality, and terminology. 2. Role of r. DCs in homeostasis, in particular cross-talk with intrinsic kidney cells like tubular epithelial cells, needs to be clarified. 3. Role of r. DCs in many diseases is unclear, such as pauci-immune GN and immunoglobulin A (Ig. A) nephritis, but also in prevalent non-immune-mediated diseases like diabetic or hypertensive kidney disease. 4. Define the molecular mechanisms causing r. DC maturation and acquisition of proinflammatory phenotype, in order to allow the development of selective therapeutic strategies. 5. Align murine and human dendritic cell (DC) terminology, so that information on DC functions from experimental models can be extrapolated to kidney biopsy findings.

major challenges facing the field in the near future 1. Current definitions of renal dendritic cells (r. DCs) and macrophages overlap. Reach consensus on phenotype, functionality, and terminology. 2. Role of r. DCs in homeostasis, in particular cross-talk with intrinsic kidney cells like tubular epithelial cells, needs to be clarified. 3. Role of r. DCs in many diseases is unclear, such as pauci-immune GN and immunoglobulin A (Ig. A) nephritis, but also in prevalent non-immune-mediated diseases like diabetic or hypertensive kidney disease. 4. Define the molecular mechanisms causing r. DC maturation and acquisition of proinflammatory phenotype, in order to allow the development of selective therapeutic strategies. 5. Align murine and human dendritic cell (DC) terminology, so that information on DC functions from experimental models can be extrapolated to kidney biopsy findings.

Significant progress in understanding the renal mononuclear phagocytic system has been achieved over the past three decades. Many typical DC and Mø-associated functions of the major r. Mo. Ph subsets have been described, especially in the last 5 years. However, r. Mo. Ph may fulfill definitions and functions both of DCs and Mø, hampering definitive classification. Indeed, parallel streams of literature have been created that do not provide a fully integrated body of knowledge to this point.

Significant progress in understanding the renal mononuclear phagocytic system has been achieved over the past three decades. Many typical DC and Mø-associated functions of the major r. Mo. Ph subsets have been described, especially in the last 5 years. However, r. Mo. Ph may fulfill definitions and functions both of DCs and Mø, hampering definitive classification. Indeed, parallel streams of literature have been created that do not provide a fully integrated body of knowledge to this point.

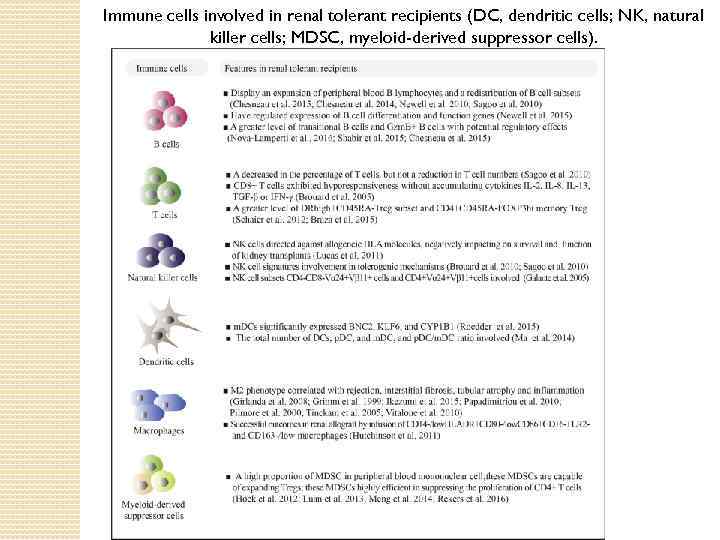

Immune cells involved in renal tolerant recipients (DC, dendritic cells; NK, natural killer cells; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cells).

Immune cells involved in renal tolerant recipients (DC, dendritic cells; NK, natural killer cells; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cells).