ca0d66c5bd91d6ab3bac5869cb36dc96.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 20

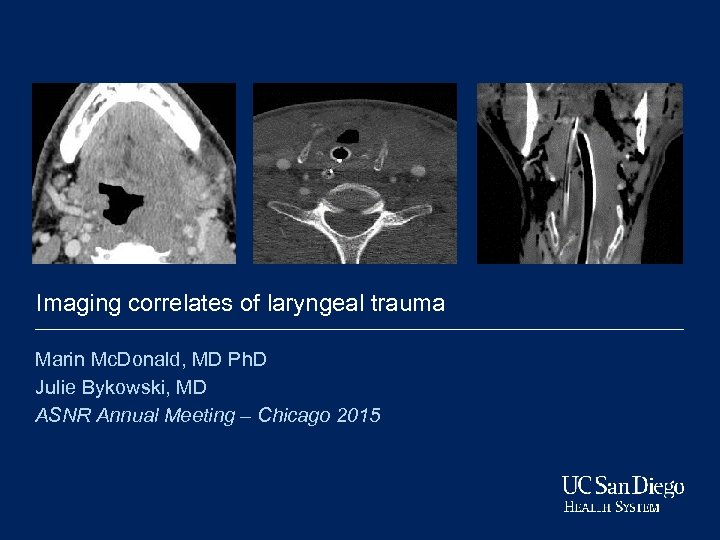

Imaging correlates of laryngeal trauma Marin Mc. Donald, MD Ph. D Julie Bykowski, MD ASNR Annual Meeting – Chicago 2015

Imaging correlates of laryngeal trauma Marin Mc. Donald, MD Ph. D Julie Bykowski, MD ASNR Annual Meeting – Chicago 2015

Disclosures • The authors have nothing to disclose.

Disclosures • The authors have nothing to disclose.

Educational Goals • To develop a systematic review of suspected acute laryngeal injury based on supraglottic, glottic and subglottic locations • To recognize findings which have implications for airway management • To review chronic sequelae of laryngeal injury

Educational Goals • To develop a systematic review of suspected acute laryngeal injury based on supraglottic, glottic and subglottic locations • To recognize findings which have implications for airway management • To review chronic sequelae of laryngeal injury

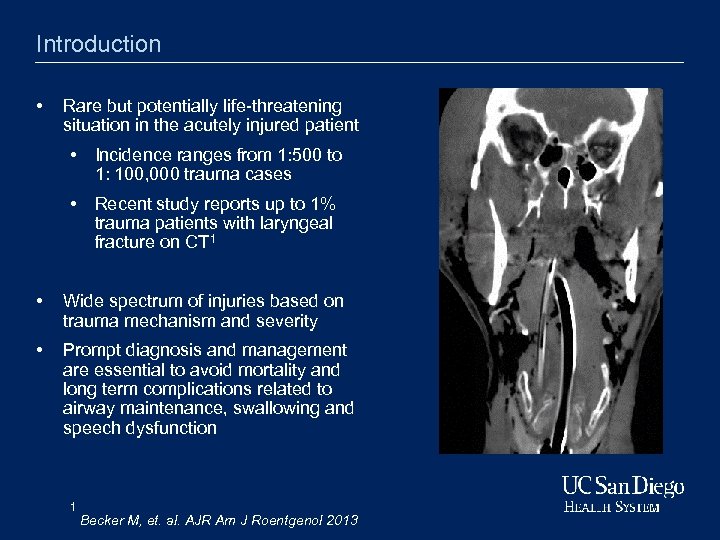

Introduction • Rare but potentially life-threatening situation in the acutely injured patient • Incidence ranges from 1: 500 to 1: 100, 000 trauma cases • Recent study reports up to 1% trauma patients with laryngeal fracture on CT 1 • Wide spectrum of injuries based on trauma mechanism and severity • Prompt diagnosis and management are essential to avoid mortality and long term complications related to airway maintenance, swallowing and speech dysfunction 1 Becker M, et. al. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013

Introduction • Rare but potentially life-threatening situation in the acutely injured patient • Incidence ranges from 1: 500 to 1: 100, 000 trauma cases • Recent study reports up to 1% trauma patients with laryngeal fracture on CT 1 • Wide spectrum of injuries based on trauma mechanism and severity • Prompt diagnosis and management are essential to avoid mortality and long term complications related to airway maintenance, swallowing and speech dysfunction 1 Becker M, et. al. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013

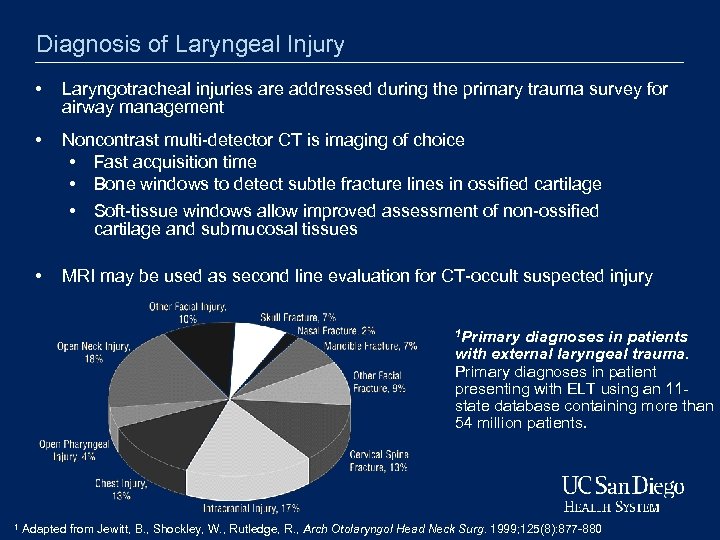

Diagnosis of Laryngeal Injury • Laryngotracheal injuries are addressed during the primary trauma survey for airway management • Noncontrast multi-detector CT is imaging of choice • Fast acquisition time • Bone windows to detect subtle fracture lines in ossified cartilage • Soft-tissue windows allow improved assessment of non-ossified cartilage and submucosal tissues • MRI may be used as second line evaluation for CT-occult suspected injury 1 Primary diagnoses in patients with external laryngeal trauma. Primary diagnoses in patient presenting with ELT using an 11 state database containing more than 54 million patients. 1 Adapted from Jewitt, B. , Shockley, W. , Rutledge, R. , Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999; 125(8): 877 -880

Diagnosis of Laryngeal Injury • Laryngotracheal injuries are addressed during the primary trauma survey for airway management • Noncontrast multi-detector CT is imaging of choice • Fast acquisition time • Bone windows to detect subtle fracture lines in ossified cartilage • Soft-tissue windows allow improved assessment of non-ossified cartilage and submucosal tissues • MRI may be used as second line evaluation for CT-occult suspected injury 1 Primary diagnoses in patients with external laryngeal trauma. Primary diagnoses in patient presenting with ELT using an 11 state database containing more than 54 million patients. 1 Adapted from Jewitt, B. , Shockley, W. , Rutledge, R. , Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999; 125(8): 877 -880

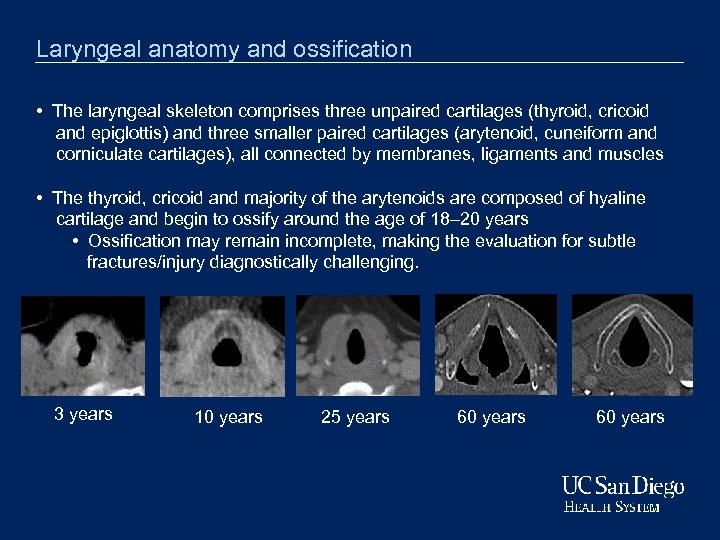

Laryngeal anatomy and ossification • The laryngeal skeleton comprises three unpaired cartilages (thyroid, cricoid and epiglottis) and three smaller paired cartilages (arytenoid, cuneiform and corniculate cartilages), all connected by membranes, ligaments and muscles • The thyroid, cricoid and majority of the arytenoids are composed of hyaline cartilage and begin to ossify around the age of 18– 20 years • Ossification may remain incomplete, making the evaluation for subtle fractures/injury diagnostically challenging. 3 years 10 years 25 years 60 years

Laryngeal anatomy and ossification • The laryngeal skeleton comprises three unpaired cartilages (thyroid, cricoid and epiglottis) and three smaller paired cartilages (arytenoid, cuneiform and corniculate cartilages), all connected by membranes, ligaments and muscles • The thyroid, cricoid and majority of the arytenoids are composed of hyaline cartilage and begin to ossify around the age of 18– 20 years • Ossification may remain incomplete, making the evaluation for subtle fractures/injury diagnostically challenging. 3 years 10 years 25 years 60 years

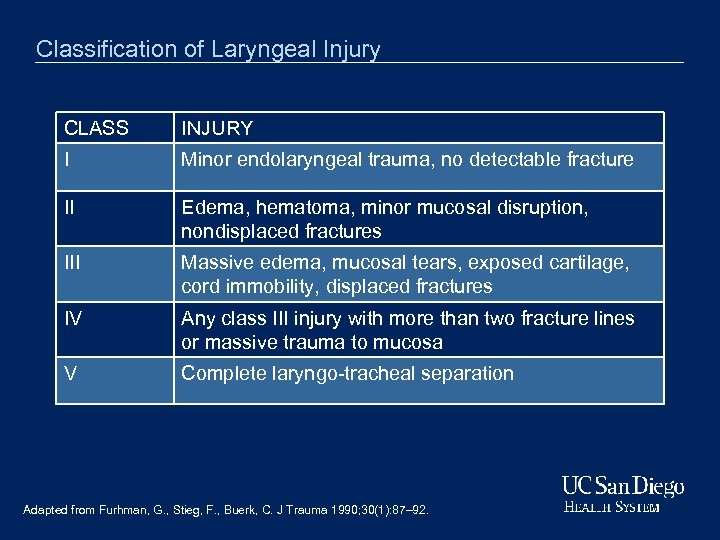

Classification of Laryngeal Injury CLASS INJURY I Minor endolaryngeal trauma, no detectable fracture II Edema, hematoma, minor mucosal disruption, nondisplaced fractures III Massive edema, mucosal tears, exposed cartilage, cord immobility, displaced fractures IV Any class III injury with more than two fracture lines or massive trauma to mucosa V Complete laryngo-tracheal separation Adapted from Furhman, G. , Stieg, F. , Buerk, C. J Trauma 1990; 30(1): 87– 92.

Classification of Laryngeal Injury CLASS INJURY I Minor endolaryngeal trauma, no detectable fracture II Edema, hematoma, minor mucosal disruption, nondisplaced fractures III Massive edema, mucosal tears, exposed cartilage, cord immobility, displaced fractures IV Any class III injury with more than two fracture lines or massive trauma to mucosa V Complete laryngo-tracheal separation Adapted from Furhman, G. , Stieg, F. , Buerk, C. J Trauma 1990; 30(1): 87– 92.

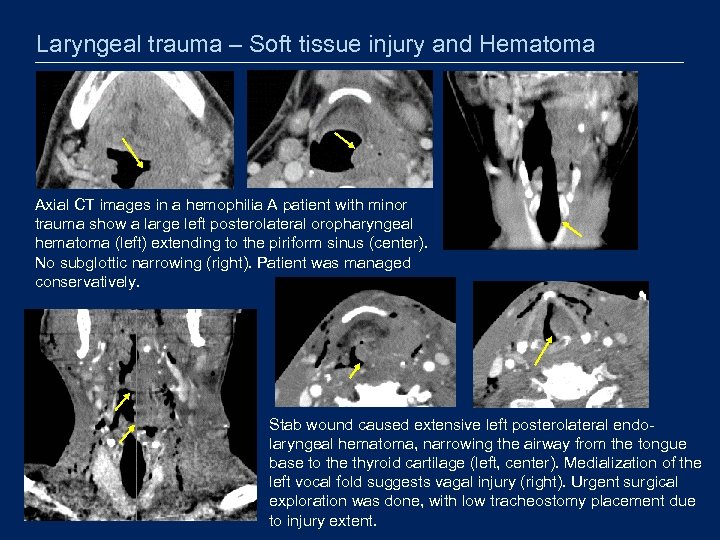

Laryngeal trauma – Soft tissue injury and Hematoma Axial CT images in a hemophilia A patient with minor trauma show a large left posterolateral oropharyngeal hematoma (left) extending to the piriform sinus (center). No subglottic narrowing (right). Patient was managed conservatively. Stab wound caused extensive left posterolateral endolaryngeal hematoma, narrowing the airway from the tongue base to the thyroid cartilage (left, center). Medialization of the left vocal fold suggests vagal injury (right). Urgent surgical exploration was done, with low tracheostomy placement due to injury extent.

Laryngeal trauma – Soft tissue injury and Hematoma Axial CT images in a hemophilia A patient with minor trauma show a large left posterolateral oropharyngeal hematoma (left) extending to the piriform sinus (center). No subglottic narrowing (right). Patient was managed conservatively. Stab wound caused extensive left posterolateral endolaryngeal hematoma, narrowing the airway from the tongue base to the thyroid cartilage (left, center). Medialization of the left vocal fold suggests vagal injury (right). Urgent surgical exploration was done, with low tracheostomy placement due to injury extent.

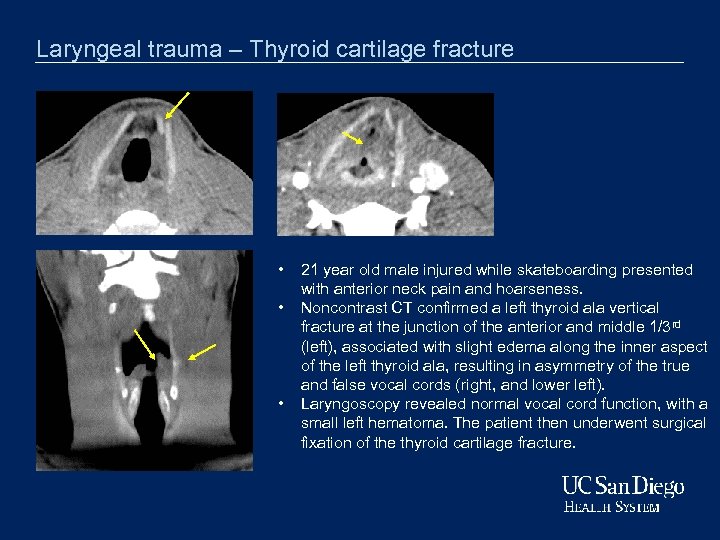

Laryngeal trauma – Thyroid cartilage fracture • • • 21 year old male injured while skateboarding presented with anterior neck pain and hoarseness. Noncontrast CT confirmed a left thyroid ala vertical fracture at the junction of the anterior and middle 1/3 rd (left), associated with slight edema along the inner aspect of the left thyroid ala, resulting in asymmetry of the true and false vocal cords (right, and lower left). Laryngoscopy revealed normal vocal cord function, with a small left hematoma. The patient then underwent surgical fixation of the thyroid cartilage fracture.

Laryngeal trauma – Thyroid cartilage fracture • • • 21 year old male injured while skateboarding presented with anterior neck pain and hoarseness. Noncontrast CT confirmed a left thyroid ala vertical fracture at the junction of the anterior and middle 1/3 rd (left), associated with slight edema along the inner aspect of the left thyroid ala, resulting in asymmetry of the true and false vocal cords (right, and lower left). Laryngoscopy revealed normal vocal cord function, with a small left hematoma. The patient then underwent surgical fixation of the thyroid cartilage fracture.

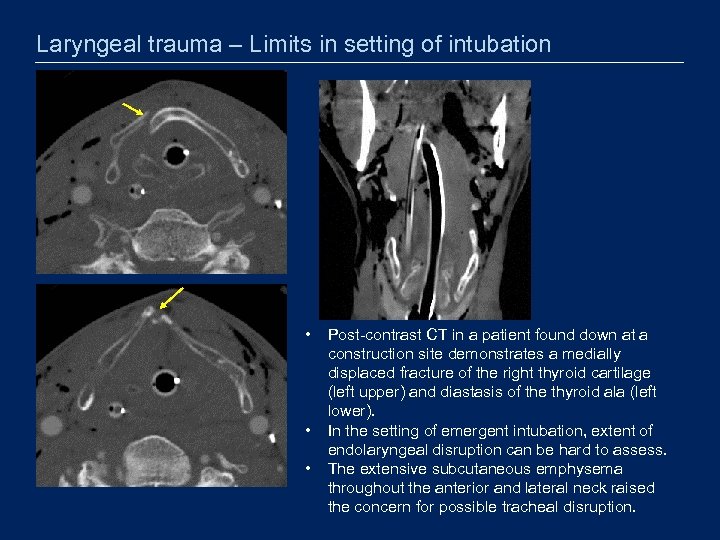

Laryngeal trauma – Limits in setting of intubation • • • Post-contrast CT in a patient found down at a construction site demonstrates a medially displaced fracture of the right thyroid cartilage (left upper) and diastasis of the thyroid ala (left lower). In the setting of emergent intubation, extent of endolaryngeal disruption can be hard to assess. The extensive subcutaneous emphysema throughout the anterior and lateral neck raised the concern for possible tracheal disruption.

Laryngeal trauma – Limits in setting of intubation • • • Post-contrast CT in a patient found down at a construction site demonstrates a medially displaced fracture of the right thyroid cartilage (left upper) and diastasis of the thyroid ala (left lower). In the setting of emergent intubation, extent of endolaryngeal disruption can be hard to assess. The extensive subcutaneous emphysema throughout the anterior and lateral neck raised the concern for possible tracheal disruption.

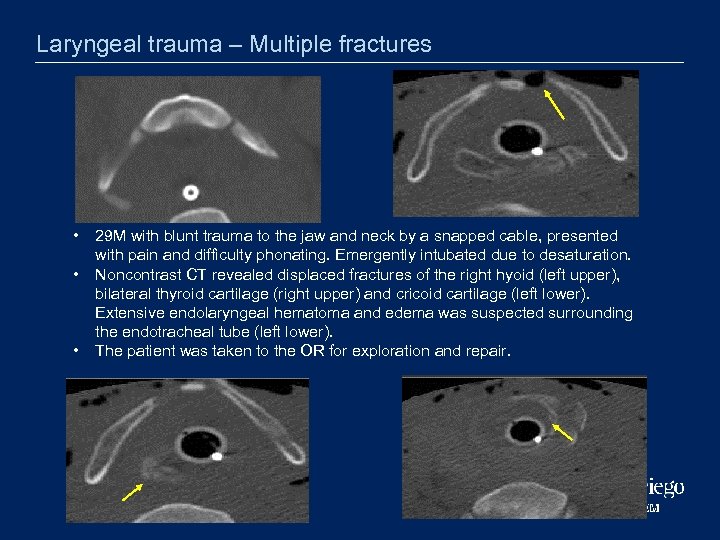

Laryngeal trauma – Multiple fractures • • • 29 M with blunt trauma to the jaw and neck by a snapped cable, presented with pain and difficulty phonating. Emergently intubated due to desaturation. Noncontrast CT revealed displaced fractures of the right hyoid (left upper), bilateral thyroid cartilage (right upper) and cricoid cartilage (left lower). Extensive endolaryngeal hematoma and edema was suspected surrounding the endotracheal tube (left lower). The patient was taken to the OR for exploration and repair.

Laryngeal trauma – Multiple fractures • • • 29 M with blunt trauma to the jaw and neck by a snapped cable, presented with pain and difficulty phonating. Emergently intubated due to desaturation. Noncontrast CT revealed displaced fractures of the right hyoid (left upper), bilateral thyroid cartilage (right upper) and cricoid cartilage (left lower). Extensive endolaryngeal hematoma and edema was suspected surrounding the endotracheal tube (left lower). The patient was taken to the OR for exploration and repair.

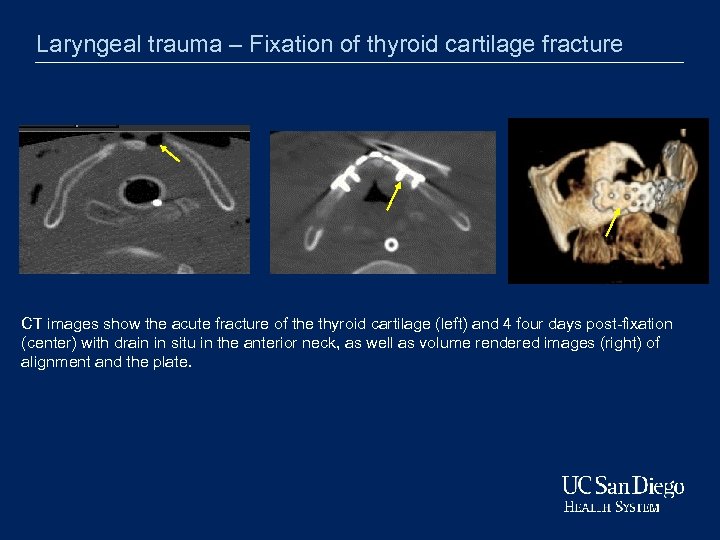

Laryngeal trauma – Fixation of thyroid cartilage fracture CT images show the acute fracture of the thyroid cartilage (left) and 4 four days post-fixation (center) with drain in situ in the anterior neck, as well as volume rendered images (right) of alignment and the plate.

Laryngeal trauma – Fixation of thyroid cartilage fracture CT images show the acute fracture of the thyroid cartilage (left) and 4 four days post-fixation (center) with drain in situ in the anterior neck, as well as volume rendered images (right) of alignment and the plate.

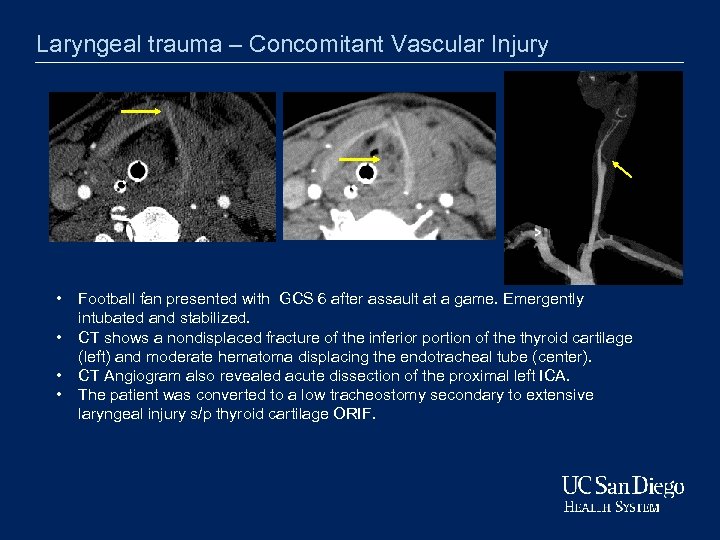

Laryngeal trauma – Concomitant Vascular Injury • • Football fan presented with GCS 6 after assault at a game. Emergently intubated and stabilized. CT shows a nondisplaced fracture of the inferior portion of the thyroid cartilage (left) and moderate hematoma displacing the endotracheal tube (center). CT Angiogram also revealed acute dissection of the proximal left ICA. The patient was converted to a low tracheostomy secondary to extensive laryngeal injury s/p thyroid cartilage ORIF.

Laryngeal trauma – Concomitant Vascular Injury • • Football fan presented with GCS 6 after assault at a game. Emergently intubated and stabilized. CT shows a nondisplaced fracture of the inferior portion of the thyroid cartilage (left) and moderate hematoma displacing the endotracheal tube (center). CT Angiogram also revealed acute dissection of the proximal left ICA. The patient was converted to a low tracheostomy secondary to extensive laryngeal injury s/p thyroid cartilage ORIF.

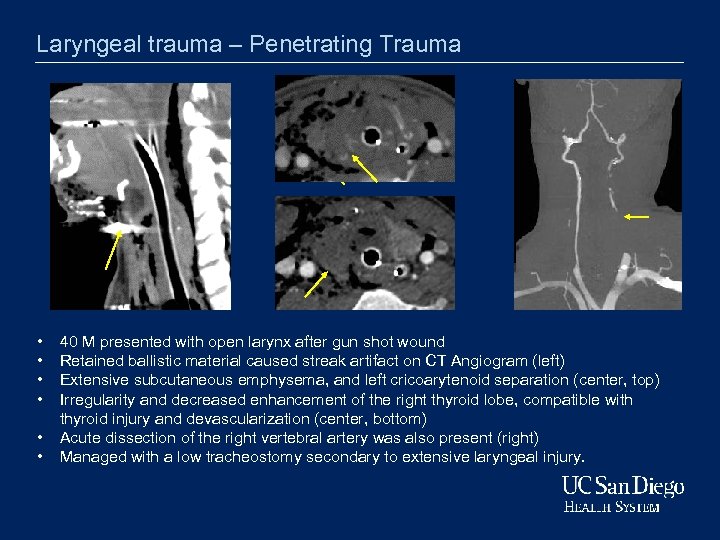

Laryngeal trauma – Penetrating Trauma • • • 40 M presented with open larynx after gun shot wound Retained ballistic material caused streak artifact on CT Angiogram (left) Extensive subcutaneous emphysema, and left cricoarytenoid separation (center, top) Irregularity and decreased enhancement of the right thyroid lobe, compatible with thyroid injury and devascularization (center, bottom) Acute dissection of the right vertebral artery was also present (right) Managed with a low tracheostomy secondary to extensive laryngeal injury.

Laryngeal trauma – Penetrating Trauma • • • 40 M presented with open larynx after gun shot wound Retained ballistic material caused streak artifact on CT Angiogram (left) Extensive subcutaneous emphysema, and left cricoarytenoid separation (center, top) Irregularity and decreased enhancement of the right thyroid lobe, compatible with thyroid injury and devascularization (center, bottom) Acute dissection of the right vertebral artery was also present (right) Managed with a low tracheostomy secondary to extensive laryngeal injury.

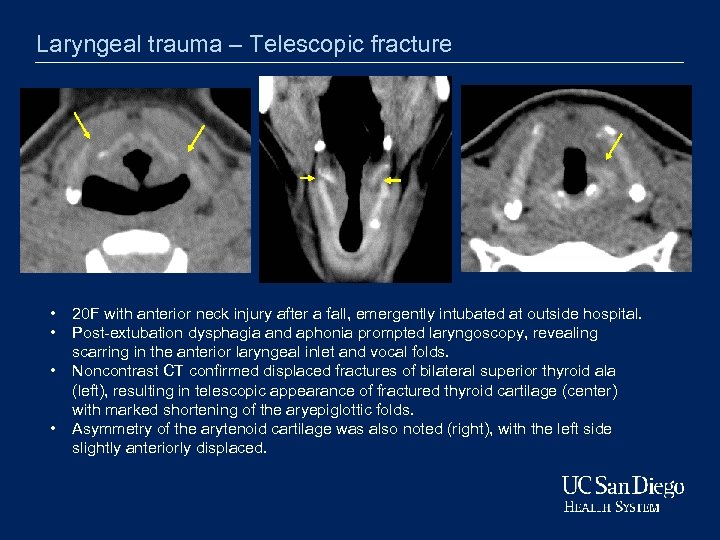

Laryngeal trauma – Telescopic fracture • • 20 F with anterior neck injury after a fall, emergently intubated at outside hospital. Post-extubation dysphagia and aphonia prompted laryngoscopy, revealing scarring in the anterior laryngeal inlet and vocal folds. Noncontrast CT confirmed displaced fractures of bilateral superior thyroid ala (left), resulting in telescopic appearance of fractured thyroid cartilage (center) with marked shortening of the aryepiglottic folds. Asymmetry of the arytenoid cartilage was also noted (right), with the left side slightly anteriorly displaced.

Laryngeal trauma – Telescopic fracture • • 20 F with anterior neck injury after a fall, emergently intubated at outside hospital. Post-extubation dysphagia and aphonia prompted laryngoscopy, revealing scarring in the anterior laryngeal inlet and vocal folds. Noncontrast CT confirmed displaced fractures of bilateral superior thyroid ala (left), resulting in telescopic appearance of fractured thyroid cartilage (center) with marked shortening of the aryepiglottic folds. Asymmetry of the arytenoid cartilage was also noted (right), with the left side slightly anteriorly displaced.

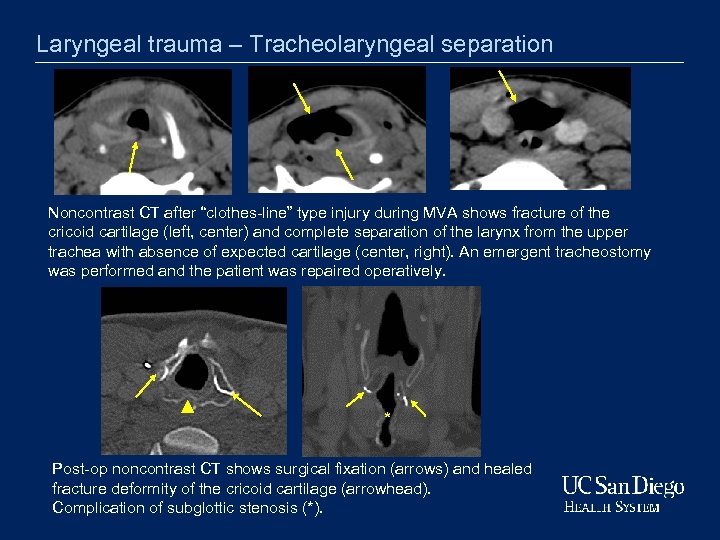

Laryngeal trauma – Tracheolaryngeal separation Noncontrast CT after “clothes-line” type injury during MVA shows fracture of the cricoid cartilage (left, center) and complete separation of the larynx from the upper trachea with absence of expected cartilage (center, right). An emergent tracheostomy was performed and the patient was repaired operatively. * Post-op noncontrast CT shows surgical fixation (arrows) and healed fracture deformity of the cricoid cartilage (arrowhead). Complication of subglottic stenosis (*).

Laryngeal trauma – Tracheolaryngeal separation Noncontrast CT after “clothes-line” type injury during MVA shows fracture of the cricoid cartilage (left, center) and complete separation of the larynx from the upper trachea with absence of expected cartilage (center, right). An emergent tracheostomy was performed and the patient was repaired operatively. * Post-op noncontrast CT shows surgical fixation (arrows) and healed fracture deformity of the cricoid cartilage (arrowhead). Complication of subglottic stenosis (*).

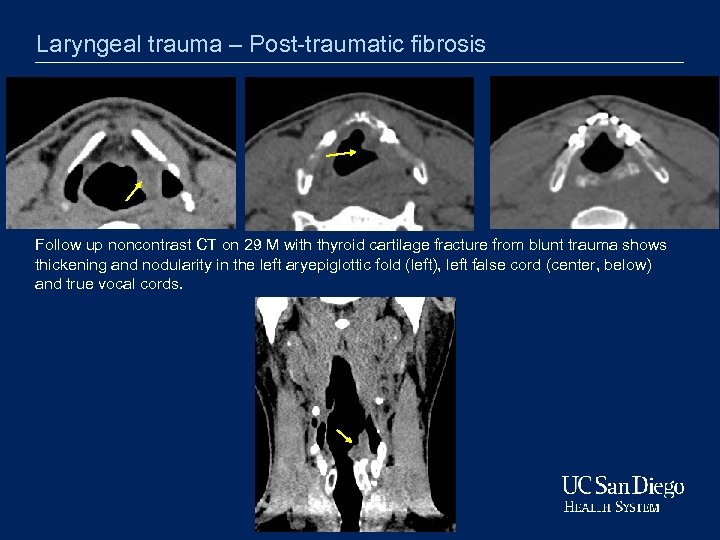

Laryngeal trauma – Post-traumatic fibrosis Follow up noncontrast CT on 29 M with thyroid cartilage fracture from blunt trauma shows thickening and nodularity in the left aryepiglottic fold (left), left false cord (center, below) and true vocal cords.

Laryngeal trauma – Post-traumatic fibrosis Follow up noncontrast CT on 29 M with thyroid cartilage fracture from blunt trauma shows thickening and nodularity in the left aryepiglottic fold (left), left false cord (center, below) and true vocal cords.

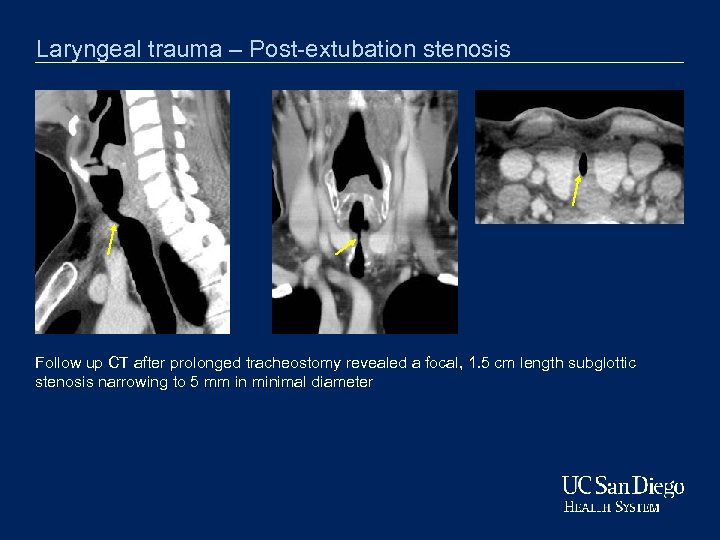

Laryngeal trauma – Post-extubation stenosis Follow up CT after prolonged tracheostomy revealed a focal, 1. 5 cm length subglottic stenosis narrowing to 5 mm in minimal diameter

Laryngeal trauma – Post-extubation stenosis Follow up CT after prolonged tracheostomy revealed a focal, 1. 5 cm length subglottic stenosis narrowing to 5 mm in minimal diameter

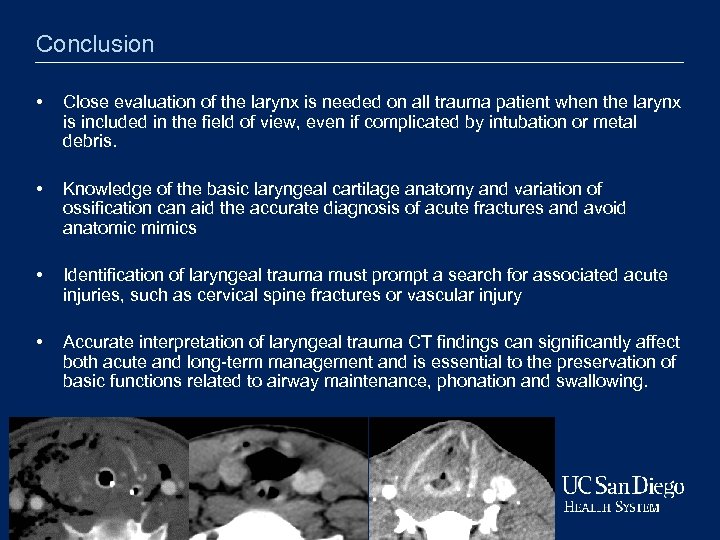

Conclusion • Close evaluation of the larynx is needed on all trauma patient when the larynx is included in the field of view, even if complicated by intubation or metal debris. • Knowledge of the basic laryngeal cartilage anatomy and variation of ossification can aid the accurate diagnosis of acute fractures and avoid anatomic mimics • Identification of laryngeal trauma must prompt a search for associated acute injuries, such as cervical spine fractures or vascular injury • Accurate interpretation of laryngeal trauma CT findings can significantly affect both acute and long-term management and is essential to the preservation of basic functions related to airway maintenance, phonation and swallowing.

Conclusion • Close evaluation of the larynx is needed on all trauma patient when the larynx is included in the field of view, even if complicated by intubation or metal debris. • Knowledge of the basic laryngeal cartilage anatomy and variation of ossification can aid the accurate diagnosis of acute fractures and avoid anatomic mimics • Identification of laryngeal trauma must prompt a search for associated acute injuries, such as cervical spine fractures or vascular injury • Accurate interpretation of laryngeal trauma CT findings can significantly affect both acute and long-term management and is essential to the preservation of basic functions related to airway maintenance, phonation and swallowing.

References • Becker, M. , Leuchter, I. , Platon, A. , Becker, C. , Dulguerov, P. , Varoquax, A. Imaging of laryngeal trauma. 2014; 83 (1)42– 154. • Becker M, Duboé PO, Platon A, et al. Assessment of laryngeal trauma with MDCT: value of 2 D multiplanar and 3 D reconstructions. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013; 201: W 639– 47. • Furhman, G. , Stieg, F. , Buerk, C. Blunt laryngeal trauma: classification and management protocol. J Trauma 1990; 30(1): 87– 92. • Jewitt, B. , Shockley, W. , Rutledge, R. , External Laryngeal Trauma Analysis of 392 Patients. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999; 125(8): 877 -880 • Lorenzo, G. , Peterson, R. , Hudgkins, P. Laryngeal Trauma: Common Findings and Imaging Pearls Neuroographics 2013; 92– 99

References • Becker, M. , Leuchter, I. , Platon, A. , Becker, C. , Dulguerov, P. , Varoquax, A. Imaging of laryngeal trauma. 2014; 83 (1)42– 154. • Becker M, Duboé PO, Platon A, et al. Assessment of laryngeal trauma with MDCT: value of 2 D multiplanar and 3 D reconstructions. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013; 201: W 639– 47. • Furhman, G. , Stieg, F. , Buerk, C. Blunt laryngeal trauma: classification and management protocol. J Trauma 1990; 30(1): 87– 92. • Jewitt, B. , Shockley, W. , Rutledge, R. , External Laryngeal Trauma Analysis of 392 Patients. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999; 125(8): 877 -880 • Lorenzo, G. , Peterson, R. , Hudgkins, P. Laryngeal Trauma: Common Findings and Imaging Pearls Neuroographics 2013; 92– 99