143019885ee88bf974fe1952fc5461ea.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 23

IBM Almaden Research Center Wringing a Table Dry: Using CSVZIP to Compress a Relation to its Entropy Vijayshankar Raman & Garret Swart © 2006 IBM Corporation

IBM Almaden Research Center Oxide is cheap, so why compress? § Make better use of memory – Increase capacity of in memory database – Increase effective cache size of on disk database § Make better use of bandwidth – I/O and memory bandwidth are expensive to scale – ALU operations are cheap and getting cheaper § Minimize storage and replication costs © 2006 IBM Corporation

IBM Almaden Research Center Why compress relations? § Relations are important for structured information § Text, video, audio, image compression is more advanced than relational § Statistical and structural properties of the relation can be exploited to improve compression § Relational data have special access patterns – Don’t just “inflate. ” Need to run selections, projections and aggregations © 2006 IBM Corporation

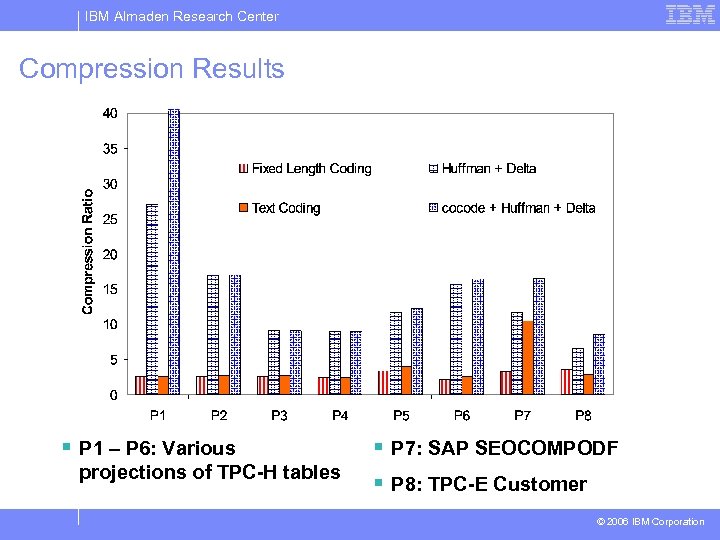

IBM Almaden Research Center Our results § Near optimal compression of relational data – Exploits data skew, column correlations and lack of ordering – Theory: Compress m i. i. d. tuples to within 4. 3 m bits of entropy (but theory doesn’t count dictionaries) – Practice: Between 8 and 40 x compression § Scanning compressed relational data – Directly perform projections, equality and range selections, and joins on entropy compressed data – Cache efficient dictionary usage – Query short circuiting © 2006 IBM Corporation

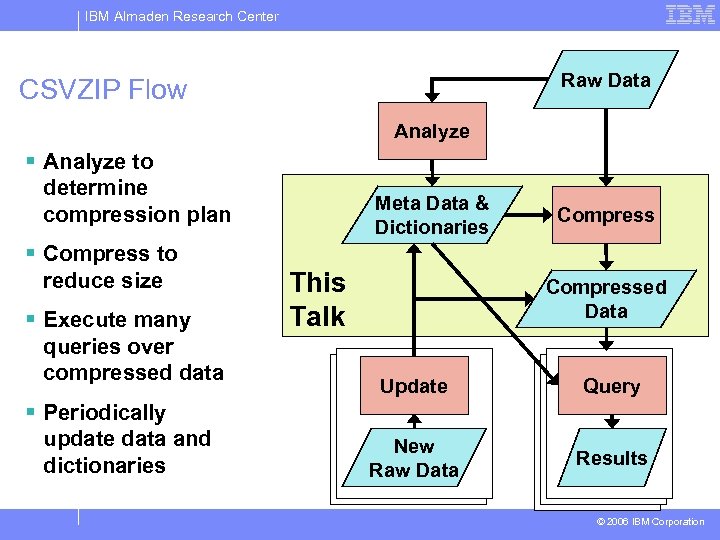

IBM Almaden Research Center Raw Data CSVZIP Flow Analyze § Analyze to determine compression plan Meta Data & Dictionaries Compress § Compress to reduce size § Execute many queries over compressed data This Talk Compressed Data Update Query New Raw Data Results § Periodically update data and dictionaries © 2006 IBM Corporation

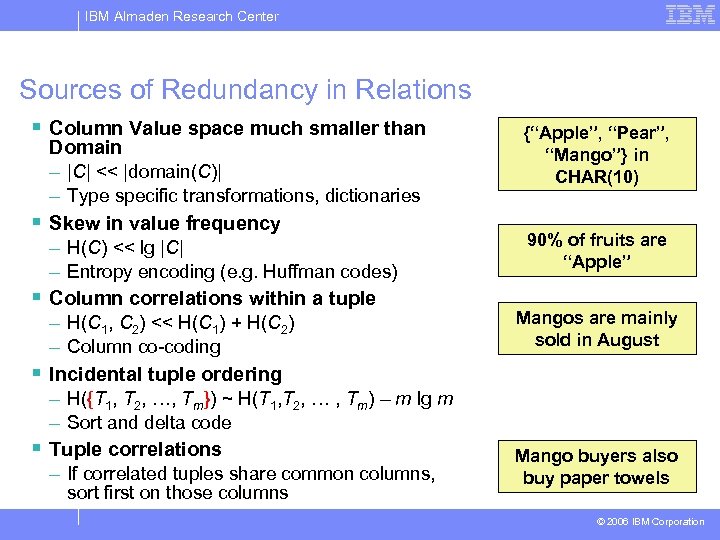

IBM Almaden Research Center Sources of Redundancy in Relations § Column Value space much smaller than § § Domain – |C| << |domain(C)| – Type specific transformations, dictionaries Skew in value frequency – H(C) << lg |C| – Entropy encoding (e. g. Huffman codes) Column correlations within a tuple – H(C 1, C 2) << H(C 1) + H(C 2) – Column co-coding Incidental tuple ordering – H({T 1, T 2, …, Tm}) ~ H(T 1, T 2, … , Tm) – m lg m – Sort and delta code Tuple correlations – If correlated tuples share common columns, sort first on those columns {“Apple”, “Pear”, “Mango”} in CHAR(10) 90% of fruits are “Apple” Mangos are mainly sold in August Mango buyers also buy paper towels © 2006 IBM Corporation

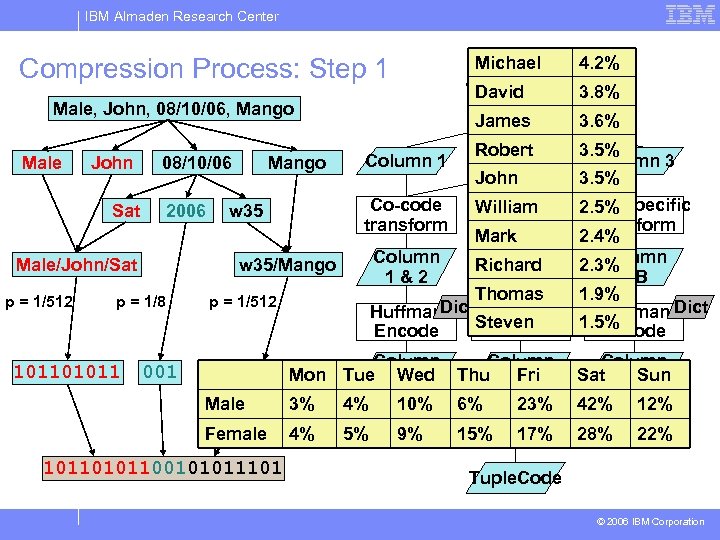

IBM Almaden Research Center Compression Process: Step 1 Michael Input tuple 4. 2% David 3. 8% Male, John, 08/10/06, Mango Male John Sat 08/10/06 2006 Male/John/Sat Male/John p = 1/512 Mango w 35/Mango p = 1/8 p = 1/512 James Robert 3. 5% Column 2 Column 3 John 3. 5% Co-code Type specific William 2. 5% transform Mark 2. 4% Column 2. 3% Column Richard 1&2 3. A 3. B Thomas 1. 9% Dict Huffman Steven 1. 5% Encode Column 1 Male 001 3% 4% 10% Column Thu Code Fri 6% 23% Female 101101011 Column 4% 5% 9% 15% 01011101 Mon Tue Code Wed 101100101011101 3. 6% 17% Column Sat Code Sun 42% 12% 28% 22% Tuple. Code © 2006 IBM Corporation

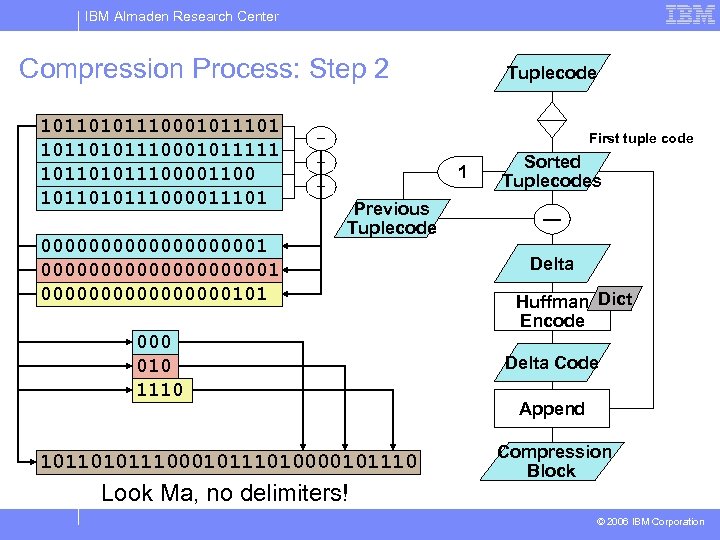

IBM Almaden Research Center Compression Process: Step 2 10110101110001011101 10110101110001011111 101101011100001100 1011010111000011101 0000000000000000000101 Tuplecode First tuple code — — 1 — Previous Tuplecode 000 010 1110 101101011100010111010000101110 Look Ma, no delimiters! Sorted Tuplecodes — Delta Huffman Dict Encode Delta Code Append Compression Block © 2006 IBM Corporation

IBM Almaden Research Center Compression Results § P 1 – P 6: Various projections of TPC-H tables § P 7: SAP SEOCOMPODF § P 8: TPC-E Customer © 2006 IBM Corporation

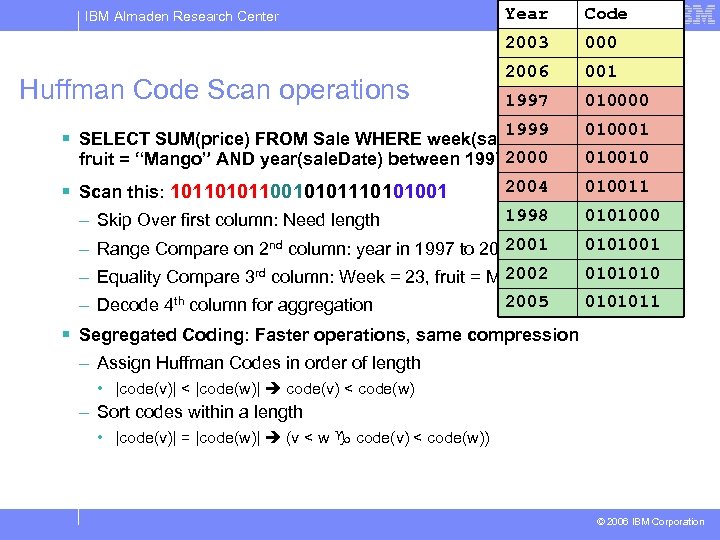

Code 000 2006 001 1997 010000 1999 Huffman Code Scan operations Year 2003 IBM Almaden Research Center 010001 § SELECT SUM(price) FROM Sale WHERE week(sale. Date) = 23 AND 010010 fruit = “Mango” AND year(sale. Date) between 19972000 2005 AND 2004 010011 1998 0101000 2001 – Range Compare on 2 nd column: year in 1997 to 2005 2002 – Equality Compare 3 rd column: Week = 23, fruit = Mango 0101001 2005 0101011 § Scan this: 10110010101110101001 – Skip Over first column: Need length – Decode 4 th column for aggregation 0101010 § Segregated Coding: Faster operations, same compression – Assign Huffman Codes in order of length • |code(v)| < |code(w)| code(v) < code(w) – Sort codes within a length • |code(v)| = |code(w)| (v < w code(v) < code(w)) © 2006 IBM Corporation

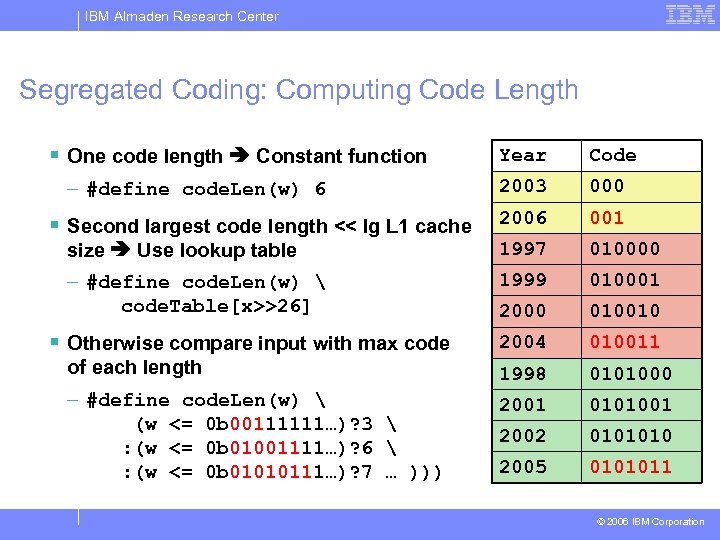

IBM Almaden Research Center Segregated Coding: Computing Code Length § One code length Constant function Year Code 2003 000 2006 001 size Use lookup table 1997 010000 – #define code. Len(w) code. Table[x>>26] 1999 010001 2000 010010 2004 010011 of each length 1998 0101000 – #define code. Len(w) (w <= 0 b 00111111…)? 3 : (w <= 0 b 01001111…)? 6 : (w <= 0 b 01010111…)? 7 … ))) 2001 0101001 2002 0101010 2005 0101011 – #define code. Len(w) 6 § Second largest code length << lg L 1 cache § Otherwise compare input with max code © 2006 IBM Corporation

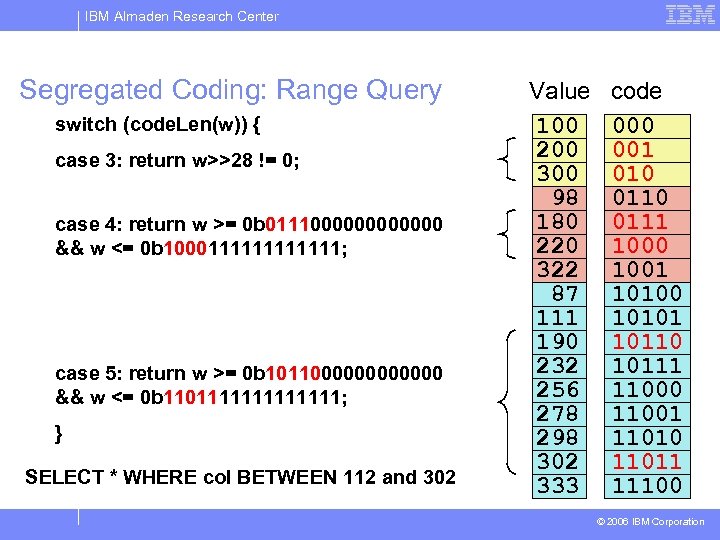

IBM Almaden Research Center Segregated Coding: Range Query switch (code. Len(w)) { case 3: return w>>28 != 0; case 4: return w >= 0 b 0111000000 && w <= 0 b 1000111111; case 5: return w >= 0 b 1011000000 && w <= 0 b 1101111111; } SELECT * WHERE col BETWEEN 112 and 302 Value 100 200 300 98 180 220 322 87 111 190 232 256 278 298 302 333 code 000 001 010 0111 1000 1001 10100 10101 10110 10111 11000 11001 11010 11011 11100 © 2006 IBM Corporation

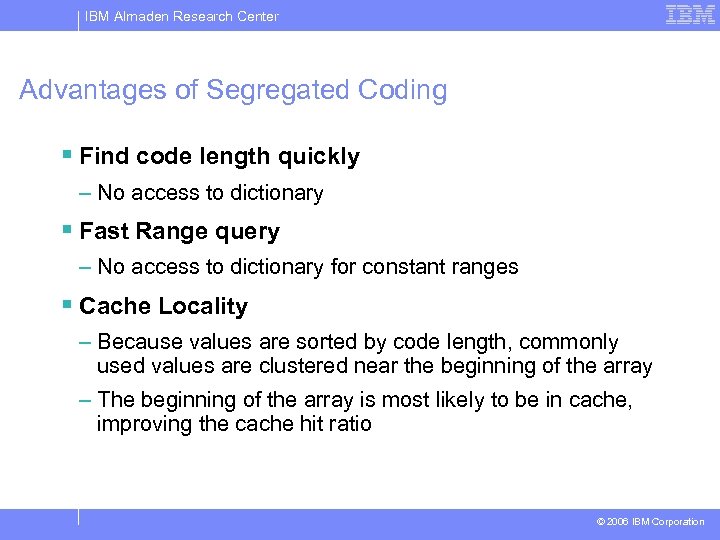

IBM Almaden Research Center Advantages of Segregated Coding § Find code length quickly – No access to dictionary § Fast Range query – No access to dictionary for constant ranges § Cache Locality – Because values are sorted by code length, commonly used values are clustered near the beginning of the array – The beginning of the array is most likely to be in cache, improving the cache hit ratio © 2006 IBM Corporation

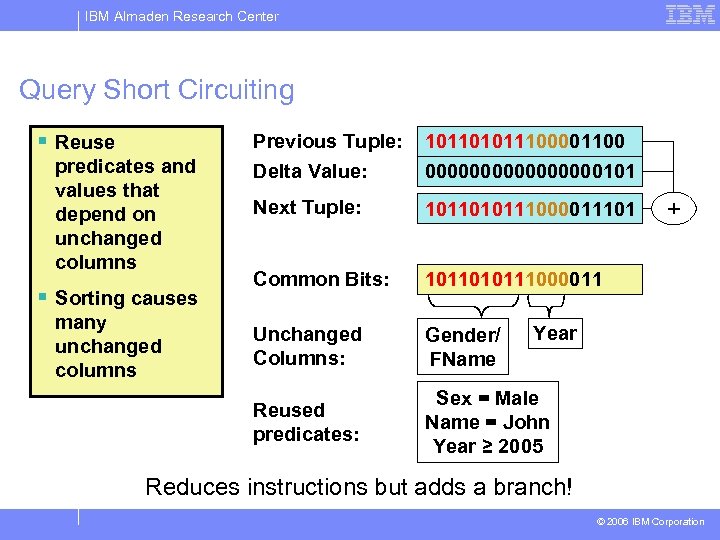

IBM Almaden Research Center Query Short Circuiting § Reuse § Sorting causes many unchanged columns 101101011100001100 00000000101 Next Tuple: 1011010111000011101 Common Bits: 1011010111000011 Unchanged Columns: Gender/ FName Reused predicates: predicates and values that depend on unchanged columns Previous Tuple: Delta Value: Sex = Male Name = John Year ≥ 2005 + Year Reduces instructions but adds a branch! © 2006 IBM Corporation

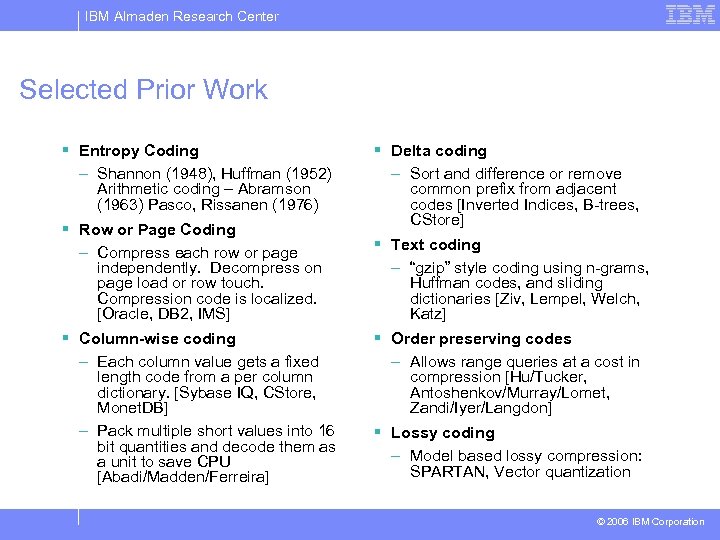

IBM Almaden Research Center Selected Prior Work § Entropy Coding – Shannon (1948), Huffman (1952) Arithmetic coding – Abramson (1963) Pasco, Rissanen (1976) § Row or Page Coding – Compress each row or page independently. Decompress on page load or row touch. Compression code is localized. [Oracle, DB 2, IMS] § Column-wise coding – Each column value gets a fixed length code from a per column dictionary. [Sybase IQ, CStore, Monet. DB] – Pack multiple short values into 16 bit quantities and decode them as a unit to save CPU [Abadi/Madden/Ferreira] § Delta coding – Sort and difference or remove common prefix from adjacent codes [Inverted Indices, B-trees, CStore] § Text coding – “gzip” style coding using n-grams, Huffman codes, and sliding dictionaries [Ziv, Lempel, Welch, Katz] § Order preserving codes – Allows range queries at a cost in compression [Hu/Tucker, Antoshenkov/Murray/Lomet, Zandi/Iyer/Langdon] § Lossy coding – Model based lossy compression: SPARTAN, Vector quantization © 2006 IBM Corporation

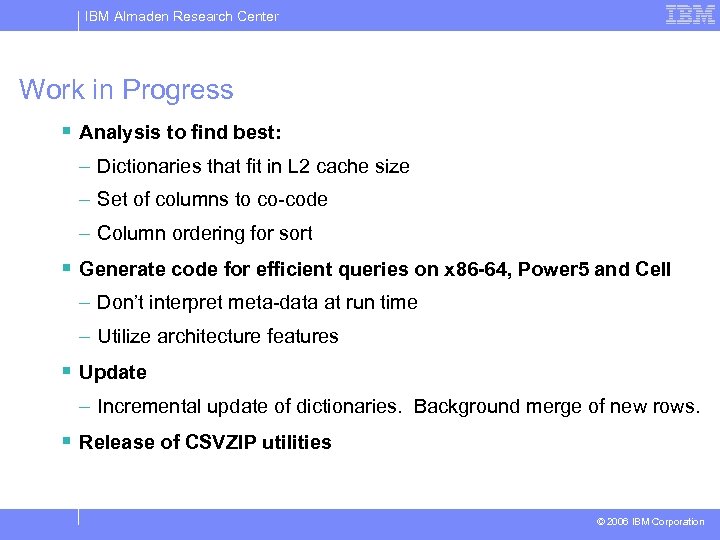

IBM Almaden Research Center Work in Progress § Analysis to find best: – Dictionaries that fit in L 2 cache size – Set of columns to co-code – Column ordering for sort § Generate code for efficient queries on x 86 -64, Power 5 and Cell – Don’t interpret meta-data at run time – Utilize architecture features § Update – Incremental update of dictionaries. Background merge of new rows. § Release of CSVZIP utilities © 2006 IBM Corporation

IBM Almaden Research Center Observations § Entropy decoding uses less I/O, but more ALU ops than conventional decoding – Our technique removes the cache as a problem – Have to squeeze every ALU op: Trends in favor § Variable length codes makes vectorization and out -of-order execution hard – Exploit compression block parallelism instead § These techniques can be exploited in a column store © 2006 IBM Corporation

IBM Almaden Research Center Back up © 2006 IBM Corporation

IBM Almaden Research Center Entropy Encoding on a Column Store § Don’t build tuple code: Treat tuple as vector of column codes and sort lexicographically § Columns early in the sort: Run length encoded deltas § Columns in the middle of the sort: Entropy encoded deltas § Columns late in the sort: Concatenated column codes § Independently break columns into compression blocks § Make dictionaries bigger because only using one at a time © 2006 IBM Corporation

IBM Almaden Research Center Entropy: A measure of information content § Entropy of a random variable R – The expected number of bits needed to represent the outcome of R – H(R) = ∑r domain(R) Pr(R = r) lg (1/ Pr(R = r)) § Conditional entropy of R given S – The expected number of bits needed to represent the outcome of R given we already know the outcome of S. – H(R | S) = ∑s domain(S) ∑r domain(R) Pr(R = r & S = s) – lg (1/ Pr(R = r & S = s)) – H(S) § If R is a random relation of size n, then R is a multi-set of random variables {T 1, …, Tn} where each random tuple Ti is a cross product of random attributes C 1 i … Cki © 2006 IBM Corporation

IBM Almaden Research Center The Entropy of a Relation § We define a random relation R of size m over D as a random variable whose outcomes are multi-sets of size m where each element is chosen identically and independently from an arbitrary tuple distribution D. The results are dependent on H(D) and thus on the optimal encoding of tuples chosen from D. – If we do a good job of co-coding and Huffman coding, then the tuple codes are entropy coded: They are random bit strings whose length depends on the distribution of the column values but whose entropy is equal to their length § Lemma 2: The Entropy of random relation R of size m over a distribution D is at least m H(D) – lg m! § Theorem 3: The Algorithm presented compresses a random relation R of size m to within H(R) + 4. 3 m bits, if m > 100 © 2006 IBM Corporation

IBM Almaden Research Center Proof of Lemma 2 § Let R be a random vector of m tuples i. i. d. over distribution D whose outcomes are sequences of m tuples, t 1, …, tm. § Obviously H(R) is m H(D). § Consider an augmentation of R that adds an index to each tuple so that ti has the value i appended. Define R 1 as a set consisting of exactly those values. H(R 1) = m H(D) as there is a bijection between R 1 and R § But the random multi-set R is a projection of the set R 1 and there are exactly m! equal probability sets R 1 that each project to each outcome of R so H(R 1) ≤ H(R) + lg m! and thus H(R) ≥ m H(D) – lg m! © 2006 IBM Corporation

IBM Almaden Research Center Proof sketch of Theorem 3 § Lemma 1 says: If R is random multi-set of m values over the uniform distribution 1. . m and m > 100, then H(delta(sort(R))) < 2. 67 m. § But we have values from an arbitrary distribution, so work by cases – For values longer than lg m bits, truncate, getting a uniform distribution in the range. – For values shorter than lg m bits, append random bits, also getting a uniform distribution. © 2006 IBM Corporation

143019885ee88bf974fe1952fc5461ea.ppt