a8bf098a5d69e455be3960153b31c936.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 1

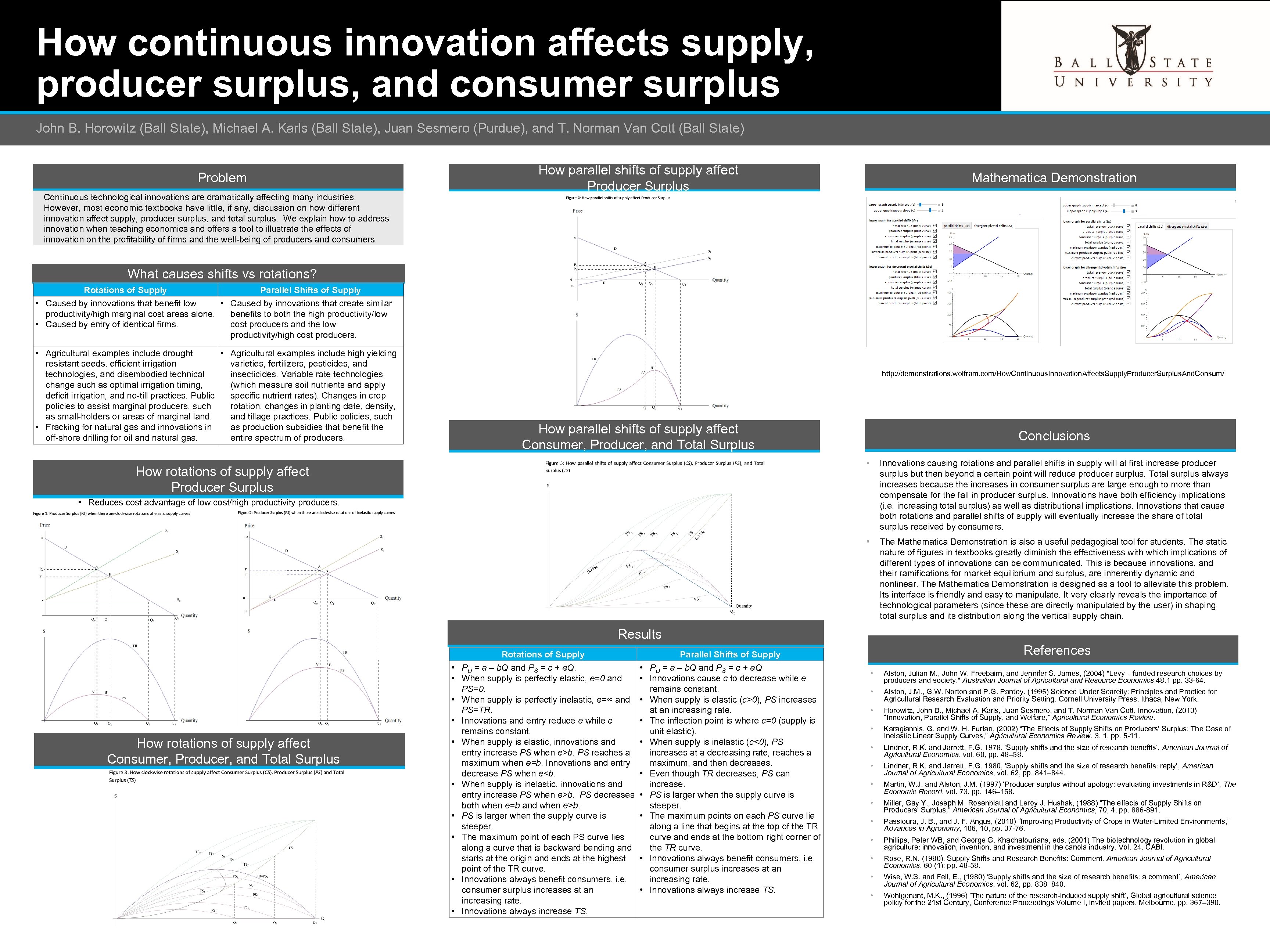

How continuous innovation affects supply, producer surplus, and consumer surplus John B. Horowitz (Ball State), Michael A. Karls (Ball State), Juan Sesmero (Purdue), and T. Norman Van Cott (Ball State) How parallel shifts of supply affect Producer Surplus Problem Continuous technological innovations are dramatically affecting many industries. However, most economic textbooks have little, if any, discussion on how different innovation affect supply, producer surplus, and total surplus. We explain how to address innovation when teaching economics and offers a tool to illustrate the effects of innovation on the profitability of firms and the well-being of producers and consumers. Mathematica Demonstration What causes shifts vs rotations? Rotations of Supply Parallel Shifts of Supply • Caused by innovations that benefit low • Caused by innovations that create similar productivity/high marginal cost areas alone. benefits to both the high productivity/low • Caused by entry of identical firms. cost producers and the low productivity/high cost producers. • Agricultural examples include drought • Agricultural examples include high yielding resistant seeds, efficient irrigation varieties, fertilizers, pesticides, and technologies, and disembodied technical insecticides. Variable rate technologies change such as optimal irrigation timing, (which measure soil nutrients and apply deficit irrigation, and no-till practices. Public specific nutrient rates). Changes in crop policies to assist marginal producers, such rotation, changes in planting date, density, as small-holders or areas of marginal land. and tillage practices. Public policies, such • Fracking for natural gas and innovations in as production subsidies that benefit the off-shore drilling for oil and natural gas. entire spectrum of producers. http: //demonstrations. wolfram. com/How. Continuous. Innovation. Affects. Supply. Producer. Surplus. And. Consum/ How parallel shifts of supply affect Consumer, Producer, and Total Surplus Conclusions • • How rotations of supply affect Producer Surplus Innovations causing rotations and parallel shifts in supply will at first increase producer surplus but then beyond a certain point will reduce producer surplus. Total surplus always increases because the increases in consumer surplus are large enough to more than compensate for the fall in producer surplus. Innovations have both efficiency implications (i. e. increasing total surplus) as well as distributional implications. Innovations that cause both rotations and parallel shifts of supply will eventually increase the share of total surplus received by consumers. The Mathematica Demonstration is also a useful pedagogical tool for students. The static nature of figures in textbooks greatly diminish the effectiveness with which implications of different types of innovations can be communicated. This is because innovations, and their ramifications for market equilibrium and surplus, are inherently dynamic and nonlinear. The Mathematica Demonstration is designed as a tool to alleviate this problem. Its interface is friendly and easy to manipulate. It very clearly reveals the importance of technological parameters (since these are directly manipulated by the user) in shaping total surplus and its distribution along the vertical supply chain. • Reduces cost advantage of low cost/high productivity producers. Results • • How rotations of supply affect Consumer, Producer, and Total Surplus • • • Rotations of Supply PD = a – b. Q and PS = c + e. Q. When supply is perfectly elastic, e=0 and PS=0. When supply is perfectly inelastic, e=∞ and PS=TR. Innovations and entry reduce e while c remains constant. When supply is elastic, innovations and entry increase PS when e>b. PS reaches a maximum when e=b. Innovations and entry decrease PS when e

How continuous innovation affects supply, producer surplus, and consumer surplus John B. Horowitz (Ball State), Michael A. Karls (Ball State), Juan Sesmero (Purdue), and T. Norman Van Cott (Ball State) How parallel shifts of supply affect Producer Surplus Problem Continuous technological innovations are dramatically affecting many industries. However, most economic textbooks have little, if any, discussion on how different innovation affect supply, producer surplus, and total surplus. We explain how to address innovation when teaching economics and offers a tool to illustrate the effects of innovation on the profitability of firms and the well-being of producers and consumers. Mathematica Demonstration What causes shifts vs rotations? Rotations of Supply Parallel Shifts of Supply • Caused by innovations that benefit low • Caused by innovations that create similar productivity/high marginal cost areas alone. benefits to both the high productivity/low • Caused by entry of identical firms. cost producers and the low productivity/high cost producers. • Agricultural examples include drought • Agricultural examples include high yielding resistant seeds, efficient irrigation varieties, fertilizers, pesticides, and technologies, and disembodied technical insecticides. Variable rate technologies change such as optimal irrigation timing, (which measure soil nutrients and apply deficit irrigation, and no-till practices. Public specific nutrient rates). Changes in crop policies to assist marginal producers, such rotation, changes in planting date, density, as small-holders or areas of marginal land. and tillage practices. Public policies, such • Fracking for natural gas and innovations in as production subsidies that benefit the off-shore drilling for oil and natural gas. entire spectrum of producers. http: //demonstrations. wolfram. com/How. Continuous. Innovation. Affects. Supply. Producer. Surplus. And. Consum/ How parallel shifts of supply affect Consumer, Producer, and Total Surplus Conclusions • • How rotations of supply affect Producer Surplus Innovations causing rotations and parallel shifts in supply will at first increase producer surplus but then beyond a certain point will reduce producer surplus. Total surplus always increases because the increases in consumer surplus are large enough to more than compensate for the fall in producer surplus. Innovations have both efficiency implications (i. e. increasing total surplus) as well as distributional implications. Innovations that cause both rotations and parallel shifts of supply will eventually increase the share of total surplus received by consumers. The Mathematica Demonstration is also a useful pedagogical tool for students. The static nature of figures in textbooks greatly diminish the effectiveness with which implications of different types of innovations can be communicated. This is because innovations, and their ramifications for market equilibrium and surplus, are inherently dynamic and nonlinear. The Mathematica Demonstration is designed as a tool to alleviate this problem. Its interface is friendly and easy to manipulate. It very clearly reveals the importance of technological parameters (since these are directly manipulated by the user) in shaping total surplus and its distribution along the vertical supply chain. • Reduces cost advantage of low cost/high productivity producers. Results • • How rotations of supply affect Consumer, Producer, and Total Surplus • • • Rotations of Supply PD = a – b. Q and PS = c + e. Q. When supply is perfectly elastic, e=0 and PS=0. When supply is perfectly inelastic, e=∞ and PS=TR. Innovations and entry reduce e while c remains constant. When supply is elastic, innovations and entry increase PS when e>b. PS reaches a maximum when e=b. Innovations and entry decrease PS when e