b628b03de5f7c0b223b4f5fa06e52935.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 35

How can School Quality and Performance be Improved? The Evidence on School Choice Simon Burgess

Introduction • Set out the issues and the economics evidence on school choice and performance: – Assignment – Issues and claims – Evidence • Focus on England, brief refs elsewhere • Note – “school choice” means different things in different countries. April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 2

Performance OK ? ? • Number of concerns expressed: – “Standards”: the typical level of educational achievement – “Basics”: the skills achieved at the lower end of the attainment distribution – Equity: how school influences attainment gaps – by socioeconomic status, gender, ethnicity – Efficiency: productivity in schools – the resources used to achieve these outcomes. April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 3

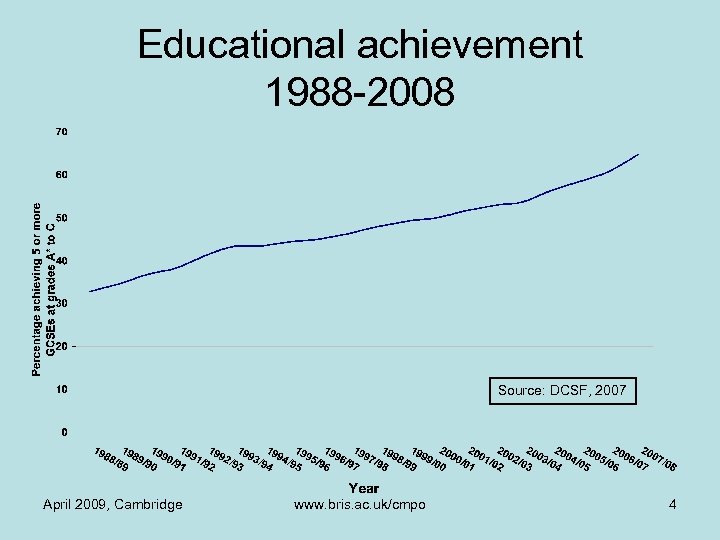

Educational achievement 1988 -2008 Source: DCSF, 2007 April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 4

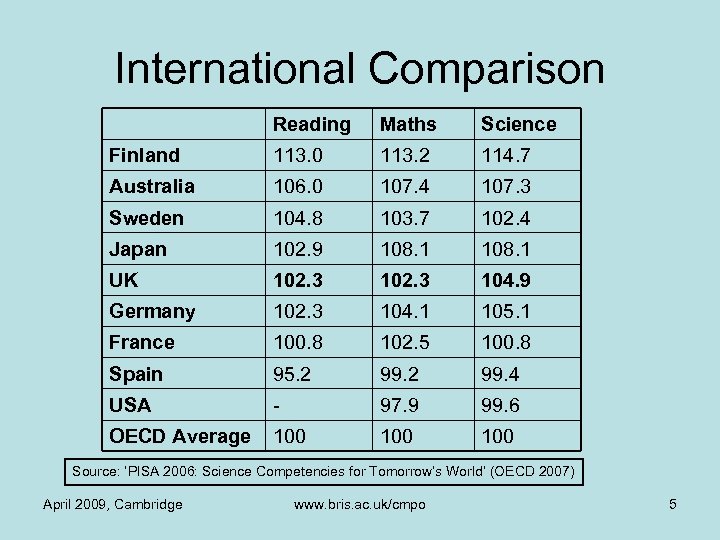

International Comparison Reading Maths Science Finland 113. 0 113. 2 114. 7 Australia 106. 0 107. 4 107. 3 Sweden 104. 8 103. 7 102. 4 Japan 102. 9 108. 1 UK 102. 3 104. 9 Germany 102. 3 104. 1 105. 1 France 100. 8 102. 5 100. 8 Spain 95. 2 99. 4 USA - 97. 9 99. 6 OECD Average 100 100 Source: ‘PISA 2006: Science Competencies for Tomorrow’s World’ (OECD 2007) April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 5

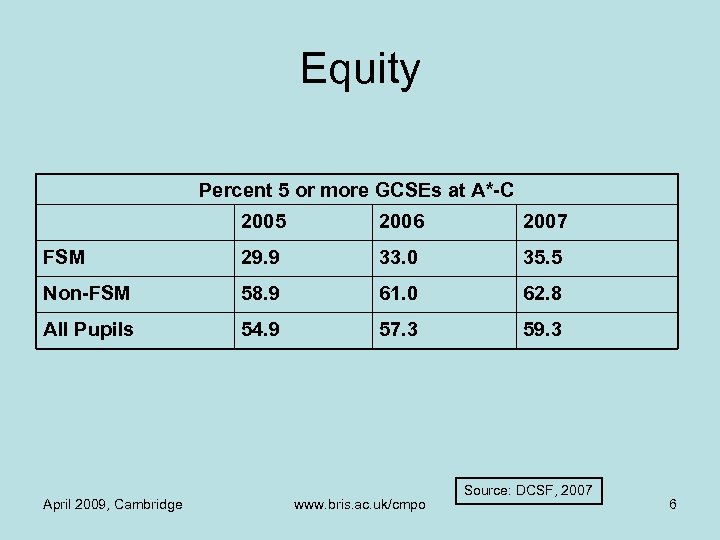

Equity Percent 5 or more GCSEs at A*-C 2005 2006 2007 FSM 29. 9 33. 0 35. 5 Non-FSM 58. 9 61. 0 62. 8 All Pupils 54. 9 57. 3 59. 3 April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo Source: DCSF, 2007 6

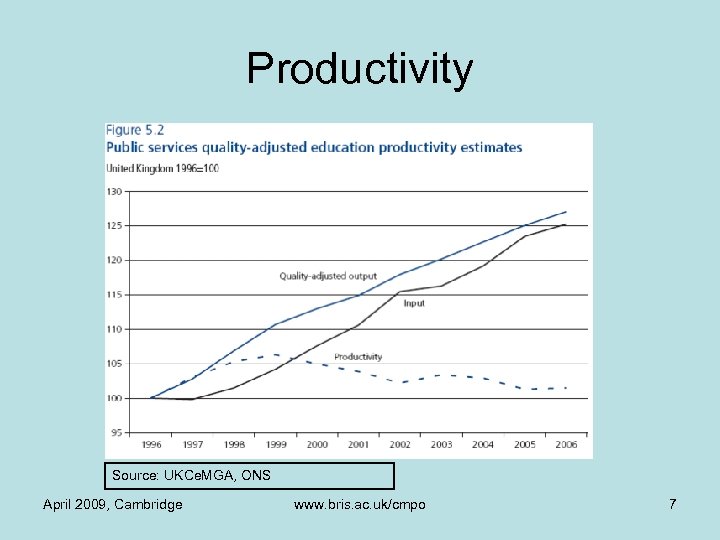

Productivity Source: UKCe. MGA, ONS April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 7

Assignment Problem • Every year: – Half a million pupils allocated to seats in primary schools, and half a million pupils allocated to seats in secondary schools • What’s the best system to do this? • Each system has incentives built into it, implicit or explicit. Incentives for schools, and for families. • We need to understand their impact on the actions of the players, and to adjust the system. April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 8

Alternatives • Neighbourhood schooling • Elite schooling (grammar schools) • Choice-based schooling • Related (supply-side) policies and issues: – – Tie-breakers such as lotteries/ballots Building new schools, Academies Private schools Neighbourhood formation April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 9

Choice-based schooling • School choice has been argued to: – Raise standards (qualifications) – Improve equity • Compare choice to alternative assignment mechanisms, not just by itself. • I will go through: – Evidence on the process – Evidence on the outcomes April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 10

Process of school choice • Choosers must: – be able to access more than one school – care strongly about quality – have good information about quality – generally get their preferred schools • Schools must: – gain by receiving many applications – be able to adjust to demand April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 11

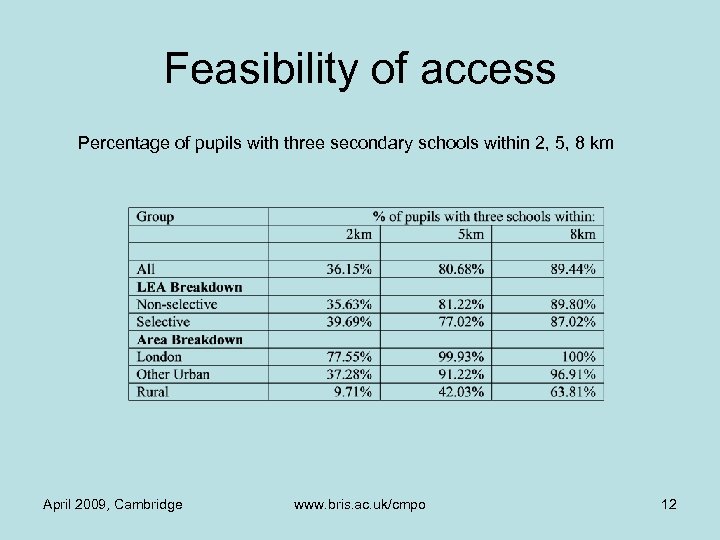

Feasibility of access Percentage of pupils with three secondary schools within 2, 5, 8 km April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 12

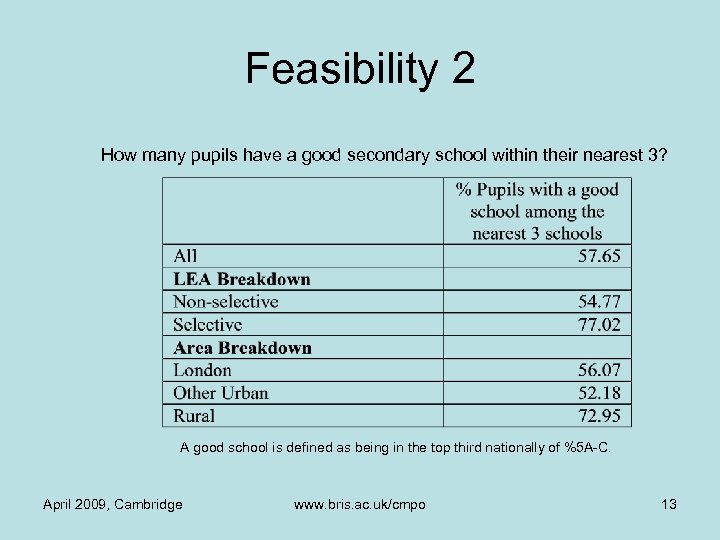

Feasibility 2 How many pupils have a good secondary school within their nearest 3? A good school is defined as being in the top third nationally of %5 A-C. April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 13

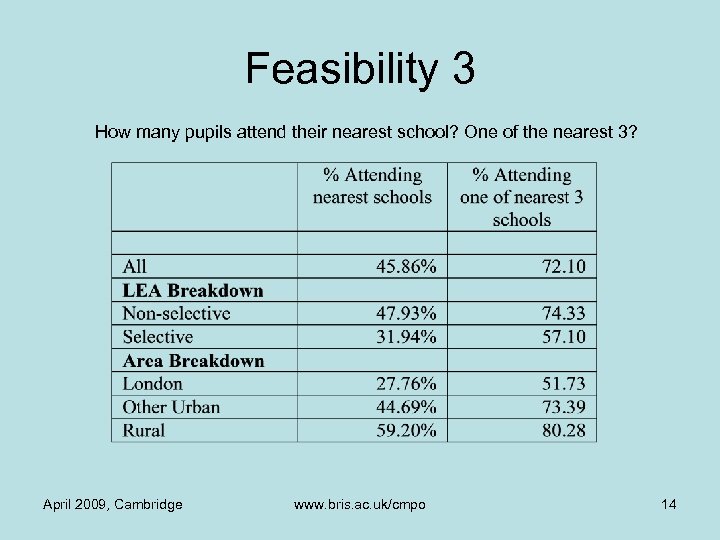

Feasibility 3 How many pupils attend their nearest school? One of the nearest 3? April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 14

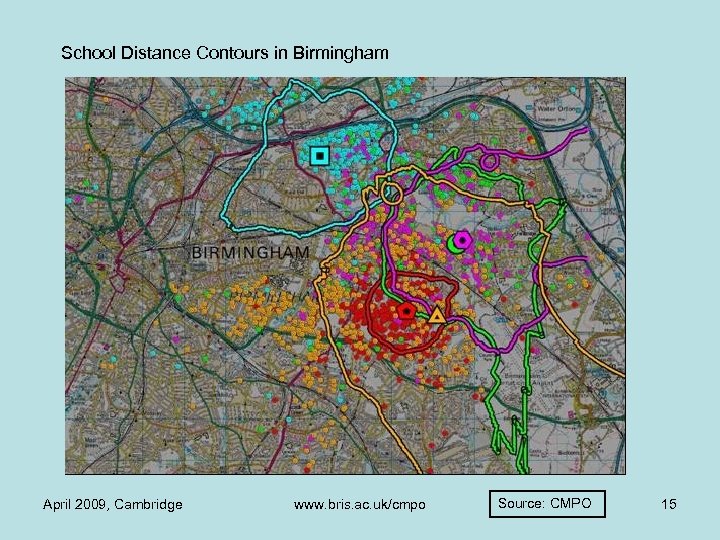

School Distance Contours in Birmingham April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo Source: CMPO 15

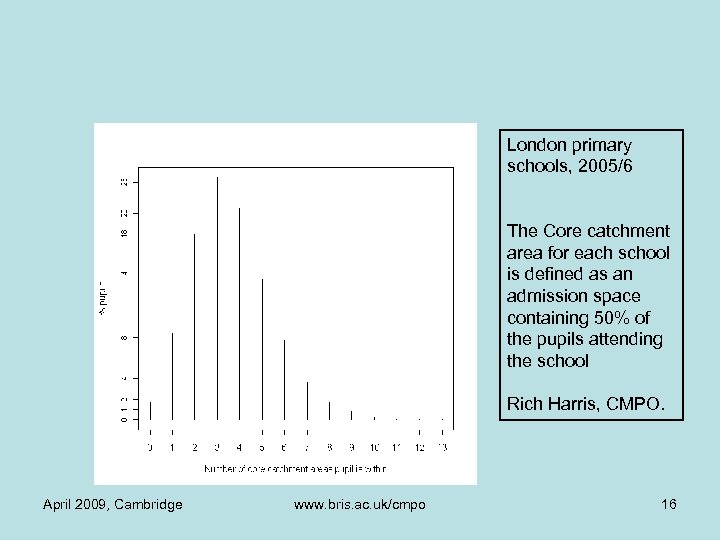

London primary schools, 2005/6 The Core catchment area for each school is defined as an admission space containing 50% of the pupils attending the school Rich Harris, CMPO. April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 16

Preferences • On-going work … • We use information on primary school preferences from the Millennium Cohort Study. • Longitudinal dataset – currently 3 waves • Sample – Born 1 st September 2000 – 31 st August 2001 – Random sample of electoral wards • • • We look at England only Wave 3 – children are aged 5, primary school age Final sample is 9, 468 children School characteristics merged from PLASC/NPD School relative locations derived using GIS April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 17

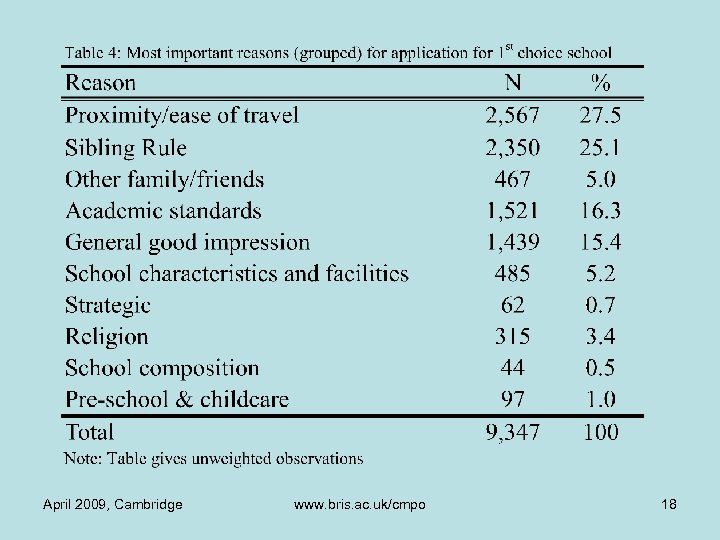

April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 18

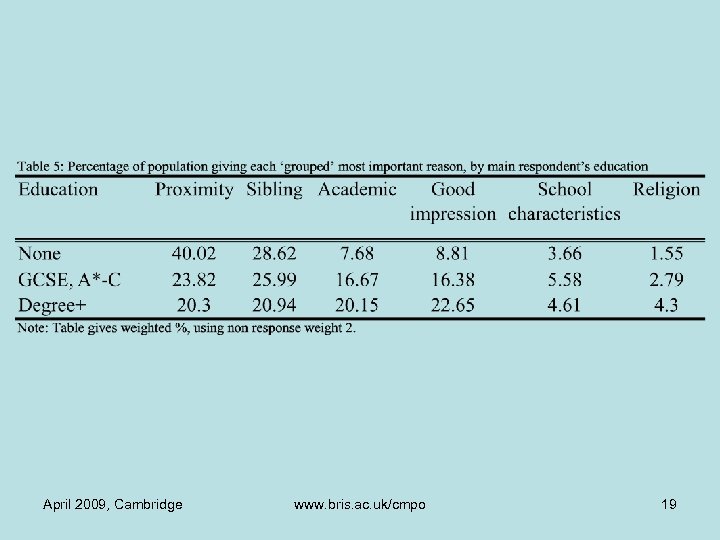

April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 19

Admissions and Strategies • Schools and LEAs have admissions rules • Given those rules and their underlying preferences, families form strategies for the school preference forms (and wider: move house; tutoring; extra-curricula activities; prayer). • Game theoretic analysis of these choices. • Abdulkadiroglu, Pathak, Roth, and Sonmez – Boston and New York mechanisms • Very complex strategies potentially in England, given variety of admissions criteria. • West and co-authors have documented these rules. April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 20

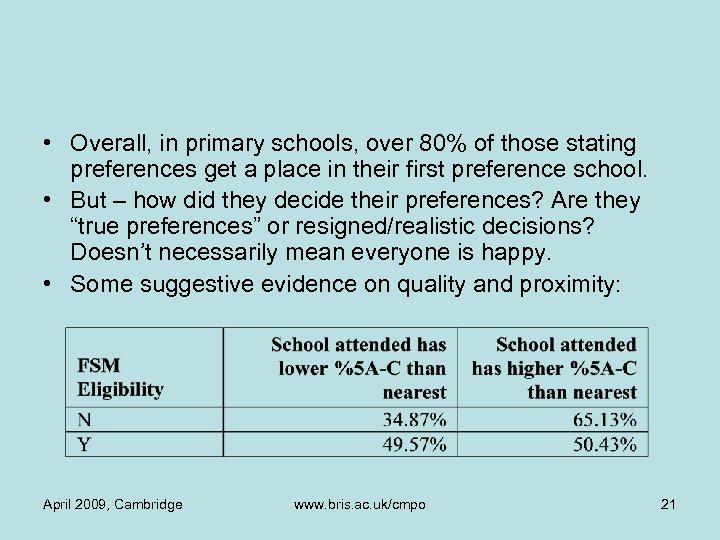

• Overall, in primary schools, over 80% of those stating preferences get a place in their first preference school. • But – how did they decide their preferences? Are they “true preferences” or resigned/realistic decisions? Doesn’t necessarily mean everyone is happy. • Some suggestive evidence on quality and proximity: April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 21

Evidence on Outcomes • • Test scores Sorting Access Neighbourhood sorting • This is evidence from England April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 22

Test scores • Overview: – Only a few papers in England that can reasonably be said to identify a causal effect. – Little effect on pupil progress; some weak and inconsistent positive effects here and there. – Allen and Vignoles (2009) – Burgess and Slater (2006) – Clark (2007) – Gibbons, Machin, and Silva (2008) • We use a boundary change to generate an exogenous change in degree of school choice. April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 23

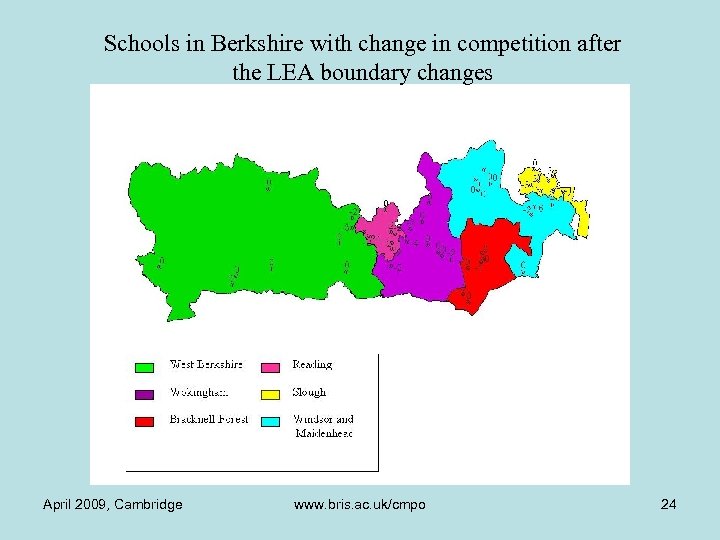

Schools in Berkshire with change in competition after the LEA boundary changes April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 24

Boundary Changes • Many LEA boundaries changed, mainly between 1996 and 1999. There is a strong presumption that pupils will attend a school within the LEA in which they live. • We find: no strong, significant effect of the decline in competition on pupil progress. • In all specifications, the point estimate is negative, but far from significant. • Significantly negative effect for Foundation or Voluntary Aided schools (schools with more control over their own admissions). • In another area, we do find a significant effect: CUBA (Counties that Used to Be Avon) April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 25

Boundary change in Avon April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 26

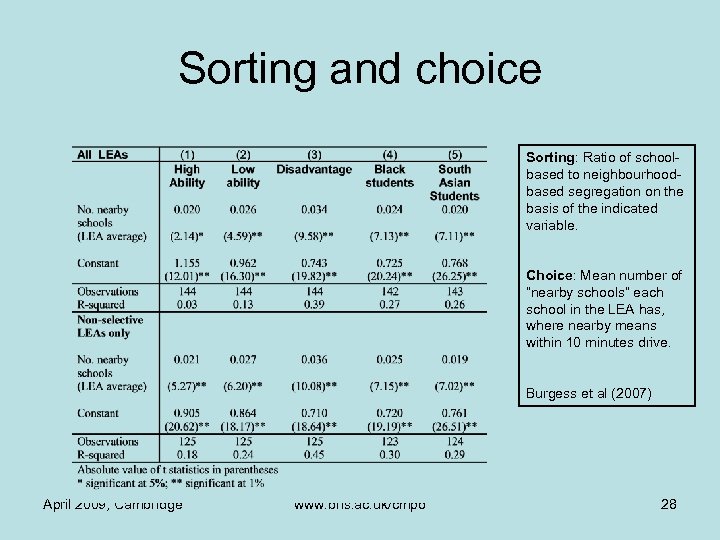

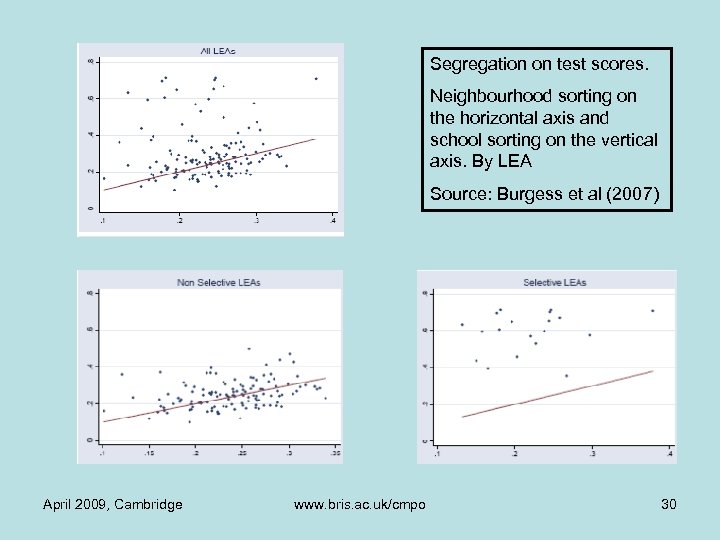

Sorting • Greater feasibility of school choice associated with greater sorting of pupils into schools. • This matters because of potential peer effects in education, and wider social concerns. • Burgess et al (2007): ratio of school segregation to neighbourhood segregation is higher in areas with more feasible choice. • Others: Allen (2008) • This may or may not be a causal link. April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 27

Sorting and choice Sorting: Ratio of schoolbased to neighbourhoodbased segregation on the basis of the indicated variable. Choice: Mean number of “nearby schools” each school in the LEA has, where nearby means within 10 minutes drive. Burgess et al (2007) April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 28

Neighbourhood Sorting • School assignment rules affect nature of communities around schools. • Neighbourhood schooling leads to strong sorting by income into neighbourhoods. • More choice-based (and no proximity rule for tie-breaks) may not. • Selection does not: April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 29

Segregation on test scores. Neighbourhood sorting on the horizontal axis and school sorting on the vertical axis. By LEA Source: Burgess et al (2007) April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 30

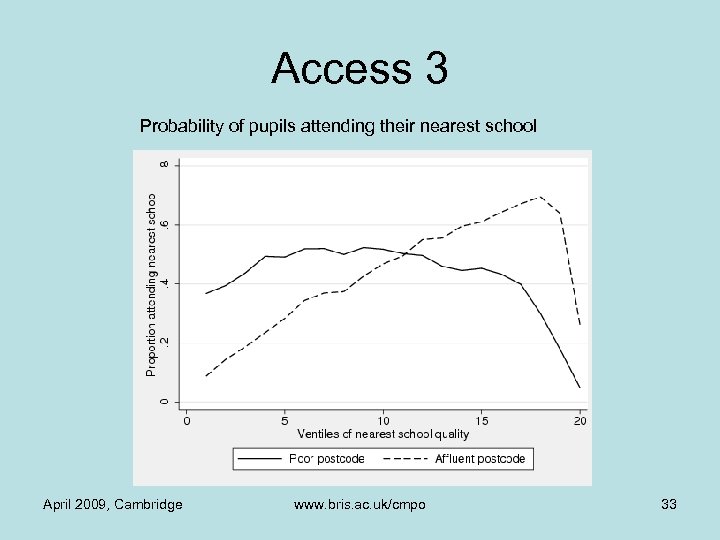

Access • What is the chance of pupils from poor families attending high scoring schools? • This matters for social mobility. • Questions: – What is the extent (if any) of a differential chance of going to a good school? – How does it happen? Comparing role of location (= proximity) and other factors – What would be the impact of increasing choice? April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 31

Access 2 • Poor children are about half as likely to go to high-scoring schools. • Much of that gap, but not all, comes through location. That is, accounting fully for location, the gap is much smaller, but not zero. • This within-location gap doesn’t vary much by degree of choice. • More support for school choice might help reduce the main barrier to attending a highscoring school: location. April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 32

Access 3 Probability of pupils attending their nearest school April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 33

Conclusions • Any assignment system has incentives built into it, implicit or explicit. • Evidence for England suggests choice & competition: – does not systematically raise scores – is associated with higher sorting. – Pure neighbourhood schooling would probably yield even higher sorting of schools and communities. – Supporting choice by poor families would help reduce the socio-economic gap in quality of school attended. • More support for choice won’t work well without accompanying supply side reforms: – Fair tie-breaks, not proximity – lotteries/ballots. – Easier school expansion or take-overs – Building new schools - Academies • Choice, accountability and incentives for schools: – Consider more resources for schools admitting pupils with low scores. – Penalise schools per pupil they fail (e. g. those who do not reach a G grade). April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 34

School choice – Relevant CMPO Papers April 2009, Cambridge www. bris. ac. uk/cmpo 35

b628b03de5f7c0b223b4f5fa06e52935.ppt