0e40d25ea058e658c0566717a9f8060e.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 34

History as a second language Mediating content and language in secondary history CLIL Tom Morton Discourse and Disciplinarity in Educational Research School of Education University of Leeds 20 -21 June 2007

History as a second language Mediating content and language in secondary history CLIL Tom Morton Discourse and Disciplinarity in Educational Research School of Education University of Leeds 20 -21 June 2007

Presentation outline 1. 2. 3. 4. CLIL in Spain and needs in bilingual education research; Examples of how teachers mediate content and language/literacies in CLIL secondary history (using a range of modes; intertextuality) A functional approach to language as a way forward in integrating language and disciplinary learning; Conclusions: threats and opportunities in CLIL as a bilingual education practice

Presentation outline 1. 2. 3. 4. CLIL in Spain and needs in bilingual education research; Examples of how teachers mediate content and language/literacies in CLIL secondary history (using a range of modes; intertextuality) A functional approach to language as a way forward in integrating language and disciplinary learning; Conclusions: threats and opportunities in CLIL as a bilingual education practice

Content and language integrated learning (CLIL) “…any dual-focused educational context in which an additional language, thus not usually the first language of the learners involved, is used as a medium in the teaching and learning of nonlanguage content. ” Marsh, 2002: 15

Content and language integrated learning (CLIL) “…any dual-focused educational context in which an additional language, thus not usually the first language of the learners involved, is used as a medium in the teaching and learning of nonlanguage content. ” Marsh, 2002: 15

Spanish Ministry of Education/British Council Bilingual Schools Project Started at infant/primary level in 1996; p Bilingual curriculum in 62 infant and primary schools and 40 secondary schools; p At secondary level, subjects include social sciences (history and geography), biology, technology; p Teachers can be non-language subject trained with competence in English, or language with competence in non-language subject p

Spanish Ministry of Education/British Council Bilingual Schools Project Started at infant/primary level in 1996; p Bilingual curriculum in 62 infant and primary schools and 40 secondary schools; p At secondary level, subjects include social sciences (history and geography), biology, technology; p Teachers can be non-language subject trained with competence in English, or language with competence in non-language subject p

2 needs in research on bilingual education (including CLIL) p The ways languages are actually used in classroom interaction and activities p The demands and affordances of language learning in the context of curriculum subject learning. Leung 2005: 250

2 needs in research on bilingual education (including CLIL) p The ways languages are actually used in classroom interaction and activities p The demands and affordances of language learning in the context of curriculum subject learning. Leung 2005: 250

History in the Bilingual Project Taught with geography (social sciences) p Textbook translated from Spanish – follows Spanish national curriculum p In bilingual project schools, subject totally taught and assessed in English p All 4 years of compulsory secondary education p Continue in Spanish in ‘bachillerato’ (16 -18) p

History in the Bilingual Project Taught with geography (social sciences) p Textbook translated from Spanish – follows Spanish national curriculum p In bilingual project schools, subject totally taught and assessed in English p All 4 years of compulsory secondary education p Continue in Spanish in ‘bachillerato’ (16 -18) p

Classroom 1: Presentations on prehistory First year secondary (12 -13 y. o. ) history class with English language trained teacher doing presentations on prehistory. Lesson consisted of three group presentations: q q q Outing to Arqueopinto (archeological theme park) Prehistoric tools and techniques Prehistoric art and sculpture

Classroom 1: Presentations on prehistory First year secondary (12 -13 y. o. ) history class with English language trained teacher doing presentations on prehistory. Lesson consisted of three group presentations: q q q Outing to Arqueopinto (archeological theme park) Prehistoric tools and techniques Prehistoric art and sculpture

Example 1: encouraging the use of the visual mode The teacher asks the student to: Draw what he is describing p Label the parts p

Example 1: encouraging the use of the visual mode The teacher asks the student to: Draw what he is describing p Label the parts p

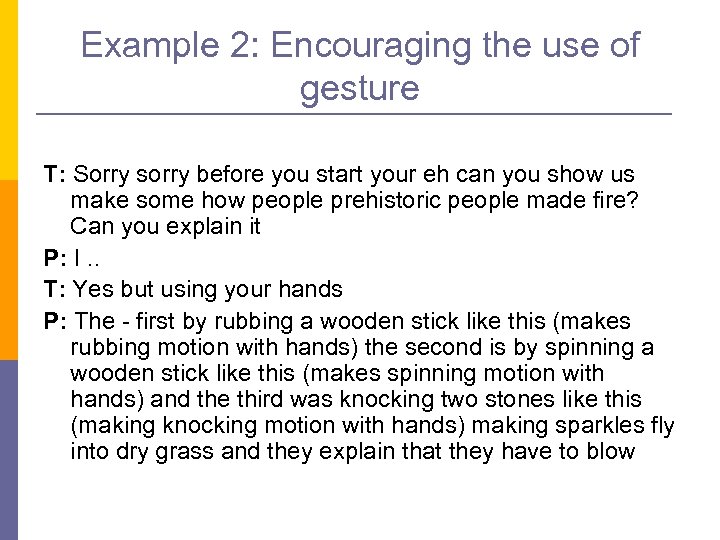

Example 2: Encouraging the use of gesture T: Sorry sorry before you start your eh can you show us make some how people prehistoric people made fire? Can you explain it P: I. . T: Yes but using your hands P: The - first by rubbing a wooden stick like this (makes rubbing motion with hands) the second is by spinning a wooden stick like this (makes spinning motion with hands) and the third was knocking two stones like this (making knocking motion with hands) making sparkles fly into dry grass and they explain that they have to blow

Example 2: Encouraging the use of gesture T: Sorry sorry before you start your eh can you show us make some how people prehistoric people made fire? Can you explain it P: I. . T: Yes but using your hands P: The - first by rubbing a wooden stick like this (makes rubbing motion with hands) the second is by spinning a wooden stick like this (makes spinning motion with hands) and the third was knocking two stones like this (making knocking motion with hands) making sparkles fly into dry grass and they explain that they have to blow

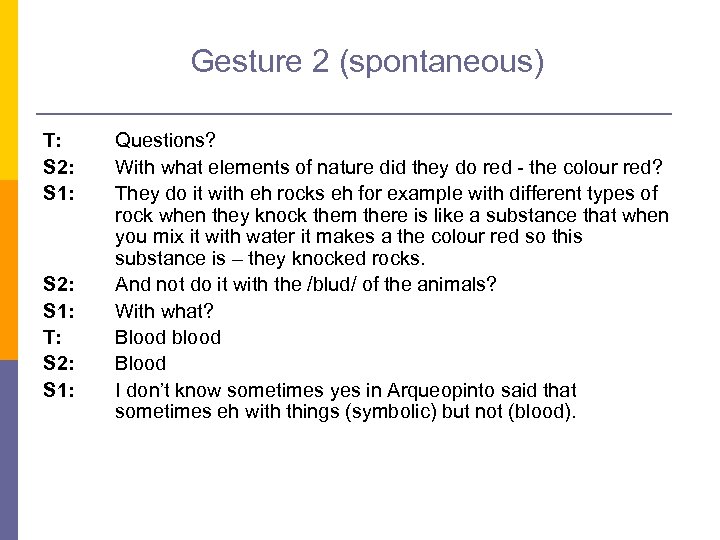

Gesture 2 (spontaneous) T: S 2: S 1: Questions? With what elements of nature did they do red - the colour red? They do it with eh rocks eh for example with different types of rock when they knock them there is like a substance that when you mix it with water it makes a the colour red so this substance is – they knocked rocks. And not do it with the /blud/ of the animals? With what? Blood blood Blood I don’t know sometimes yes in Arqueopinto said that sometimes eh with things (symbolic) but not (blood).

Gesture 2 (spontaneous) T: S 2: S 1: Questions? With what elements of nature did they do red - the colour red? They do it with eh rocks eh for example with different types of rock when they knock them there is like a substance that when you mix it with water it makes a the colour red so this substance is – they knocked rocks. And not do it with the /blud/ of the animals? With what? Blood blood Blood I don’t know sometimes yes in Arqueopinto said that sometimes eh with things (symbolic) but not (blood).

Importance of gesture in mediation of language and content Possible intrapsychological function of gesture, with gesture and speech synchronised as a single unit or ‘growth point’ (Mc. Neill and Duncan, 2000) p Creation of a a site for creating meaning, a Zone of Proximal Development, which “is cognitively at the heart of apprenticing to any new realm of understanding and becoming. ” (Mc. Cafferty, 2002: 193). p

Importance of gesture in mediation of language and content Possible intrapsychological function of gesture, with gesture and speech synchronised as a single unit or ‘growth point’ (Mc. Neill and Duncan, 2000) p Creation of a a site for creating meaning, a Zone of Proximal Development, which “is cognitively at the heart of apprenticing to any new realm of understanding and becoming. ” (Mc. Cafferty, 2002: 193). p

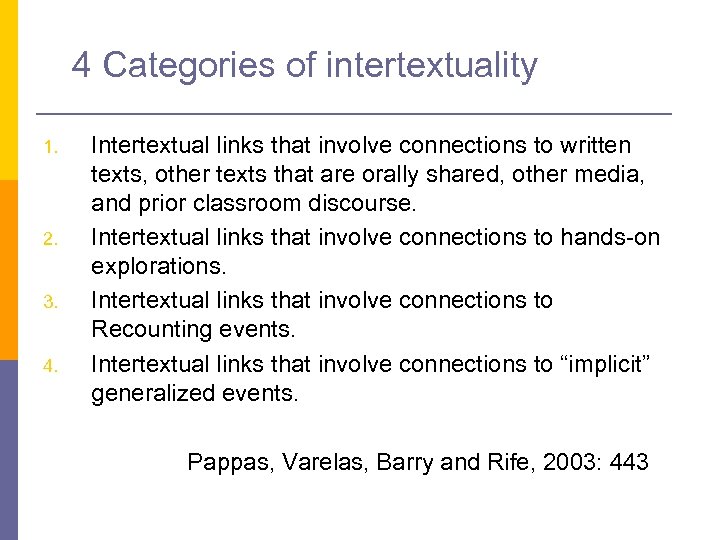

4 Categories of intertextuality 1. 2. 3. 4. Intertextual links that involve connections to written texts, other texts that are orally shared, other media, and prior classroom discourse. Intertextual links that involve connections to hands-on explorations. Intertextual links that involve connections to Recounting events. Intertextual links that involve connections to “implicit” generalized events. Pappas, Varelas, Barry and Rife, 2003: 443

4 Categories of intertextuality 1. 2. 3. 4. Intertextual links that involve connections to written texts, other texts that are orally shared, other media, and prior classroom discourse. Intertextual links that involve connections to hands-on explorations. Intertextual links that involve connections to Recounting events. Intertextual links that involve connections to “implicit” generalized events. Pappas, Varelas, Barry and Rife, 2003: 443

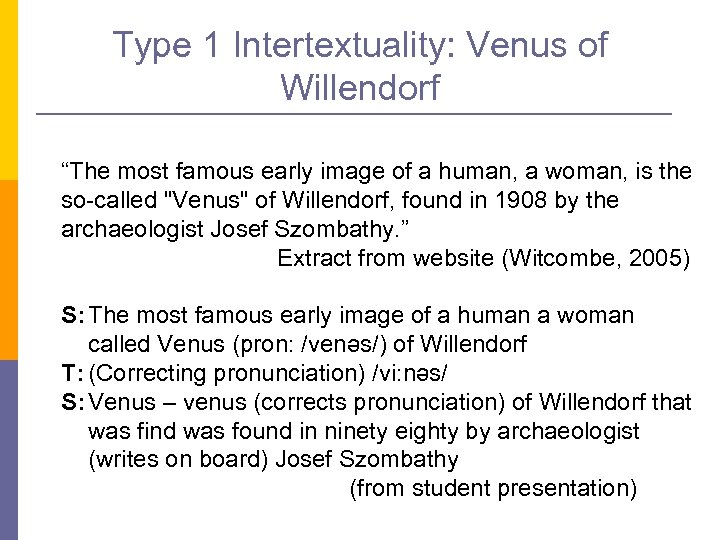

Type 1 Intertextuality: Venus of Willendorf “The most famous early image of a human, a woman, is the so-called "Venus" of Willendorf, found in 1908 by the archaeologist Josef Szombathy. ” Extract from website (Witcombe, 2005) S: The most famous early image of a human a woman called Venus (pron: /venәs/) of Willendorf T: (Correcting pronunciation) /vi: nәs/ S: Venus – venus (corrects pronunciation) of Willendorf that was find was found in ninety eighty by archaeologist (writes on board) Josef Szombathy (from student presentation)

Type 1 Intertextuality: Venus of Willendorf “The most famous early image of a human, a woman, is the so-called "Venus" of Willendorf, found in 1908 by the archaeologist Josef Szombathy. ” Extract from website (Witcombe, 2005) S: The most famous early image of a human a woman called Venus (pron: /venәs/) of Willendorf T: (Correcting pronunciation) /vi: nәs/ S: Venus – venus (corrects pronunciation) of Willendorf that was find was found in ninety eighty by archaeologist (writes on board) Josef Szombathy (from student presentation)

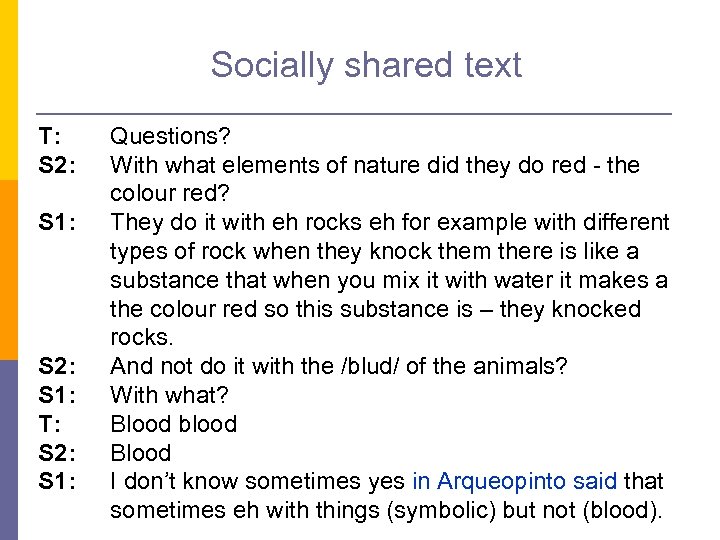

Socially shared text T: S 2: S 1: Questions? With what elements of nature did they do red - the colour red? They do it with eh rocks eh for example with different types of rock when they knock them there is like a substance that when you mix it with water it makes a the colour red so this substance is – they knocked rocks. And not do it with the /blud/ of the animals? With what? Blood blood Blood I don’t know sometimes yes in Arqueopinto said that sometimes eh with things (symbolic) but not (blood).

Socially shared text T: S 2: S 1: Questions? With what elements of nature did they do red - the colour red? They do it with eh rocks eh for example with different types of rock when they knock them there is like a substance that when you mix it with water it makes a the colour red so this substance is – they knocked rocks. And not do it with the /blud/ of the animals? With what? Blood blood Blood I don’t know sometimes yes in Arqueopinto said that sometimes eh with things (symbolic) but not (blood).

Intertextuality 3: Recounting events School outing to Arqueopinto, an open air archeological park/museum near Madrid. Note how they talk about: p What they did p What they learned

Intertextuality 3: Recounting events School outing to Arqueopinto, an open air archeological park/museum near Madrid. Note how they talk about: p What they did p What they learned

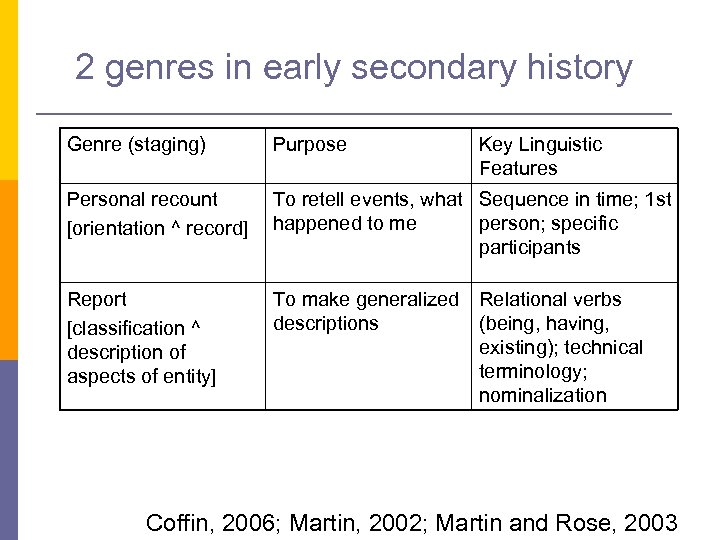

2 genres in early secondary history Genre (staging) Purpose Key Linguistic Features Personal recount [orientation ^ record] To retell events, what Sequence in time; 1 st happened to me person; specific participants Report [classification ^ description of aspects of entity] To make generalized Relational verbs descriptions (being, having, existing); technical terminology; nominalization Coffin, 2006; Martin, 2002; Martin and Rose, 2003

2 genres in early secondary history Genre (staging) Purpose Key Linguistic Features Personal recount [orientation ^ record] To retell events, what Sequence in time; 1 st happened to me person; specific participants Report [classification ^ description of aspects of entity] To make generalized Relational verbs descriptions (being, having, existing); technical terminology; nominalization Coffin, 2006; Martin, 2002; Martin and Rose, 2003

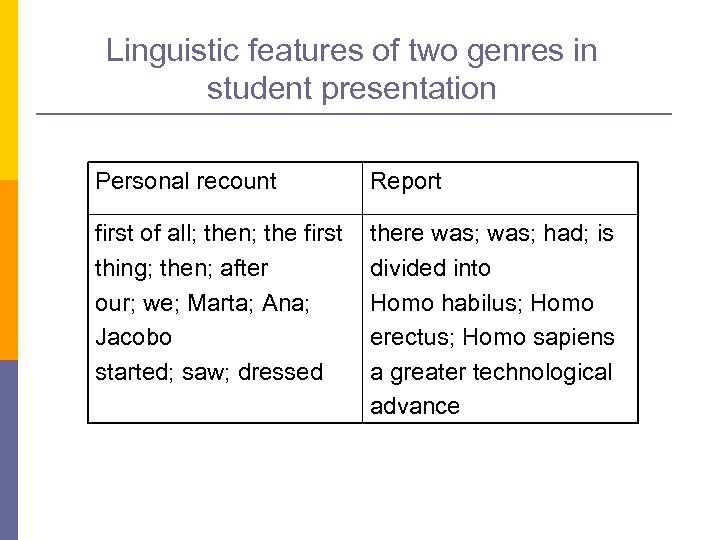

Linguistic features of two genres in student presentation Personal recount Report first of all; then; the first thing; then; after our; we; Marta; Ana; Jacobo started; saw; dressed there was; had; is divided into Homo habilus; Homo erectus; Homo sapiens a greater technological advance

Linguistic features of two genres in student presentation Personal recount Report first of all; then; the first thing; then; after our; we; Marta; Ana; Jacobo started; saw; dressed there was; had; is divided into Homo habilus; Homo erectus; Homo sapiens a greater technological advance

3 rd year history: Oliver Cromwell – hero or villain? Third year secondary history class (approx 15 y. o. ). History trained teacher, lesson on the English Revolution (trial and execution of Charles I, actions of Oliver Cromwell).

3 rd year history: Oliver Cromwell – hero or villain? Third year secondary history class (approx 15 y. o. ). History trained teacher, lesson on the English Revolution (trial and execution of Charles I, actions of Oliver Cromwell).

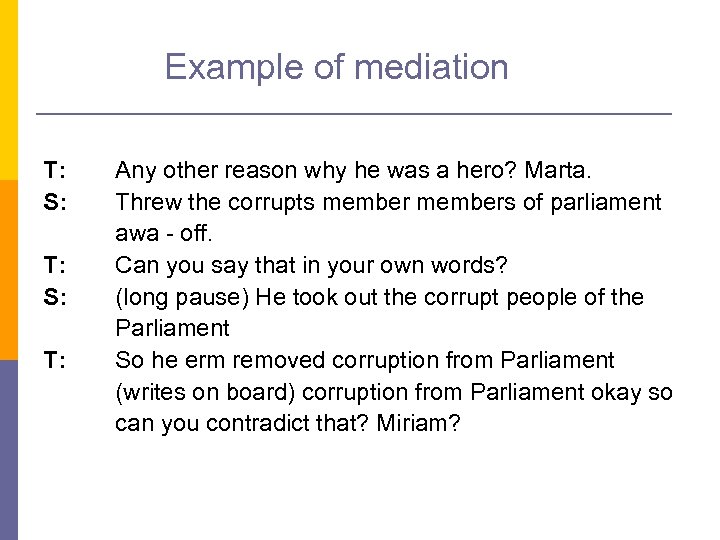

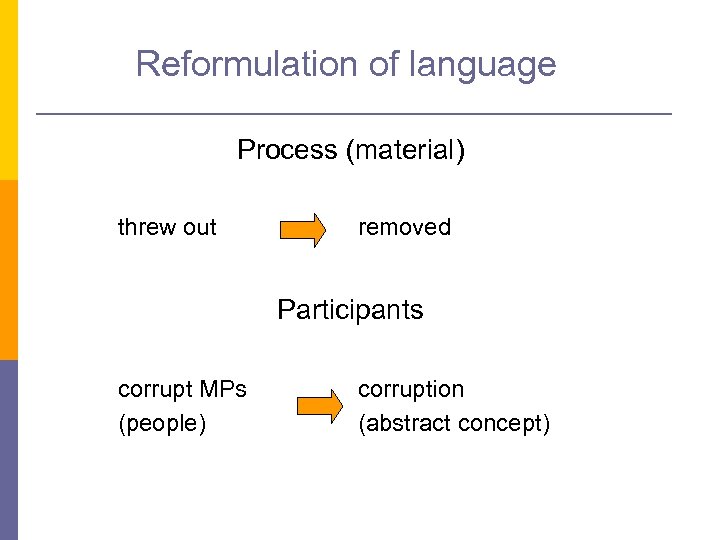

Example of mediation T: S: T: Any other reason why he was a hero? Marta. Threw the corrupts members of parliament awa - off. Can you say that in your own words? (long pause) He took out the corrupt people of the Parliament So he erm removed corruption from Parliament (writes on board) corruption from Parliament okay so can you contradict that? Miriam?

Example of mediation T: S: T: Any other reason why he was a hero? Marta. Threw the corrupts members of parliament awa - off. Can you say that in your own words? (long pause) He took out the corrupt people of the Parliament So he erm removed corruption from Parliament (writes on board) corruption from Parliament okay so can you contradict that? Miriam?

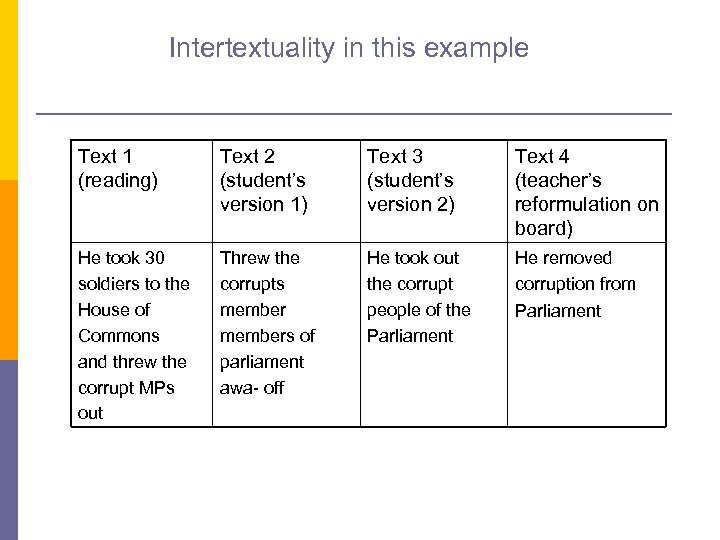

Intertextuality in this example Text 1 (reading) Text 2 (student’s version 1) Text 3 (student’s version 2) Text 4 (teacher’s reformulation on board) He took 30 soldiers to the House of Commons and threw the corrupt MPs out Threw the corrupts members of parliament awa- off He took out the corrupt people of the Parliament He removed corruption from Parliament

Intertextuality in this example Text 1 (reading) Text 2 (student’s version 1) Text 3 (student’s version 2) Text 4 (teacher’s reformulation on board) He took 30 soldiers to the House of Commons and threw the corrupt MPs out Threw the corrupts members of parliament awa- off He took out the corrupt people of the Parliament He removed corruption from Parliament

Reformulation of language Process (material) threw out removed Participants corrupt MPs (people) corruption (abstract concept)

Reformulation of language Process (material) threw out removed Participants corrupt MPs (people) corruption (abstract concept)

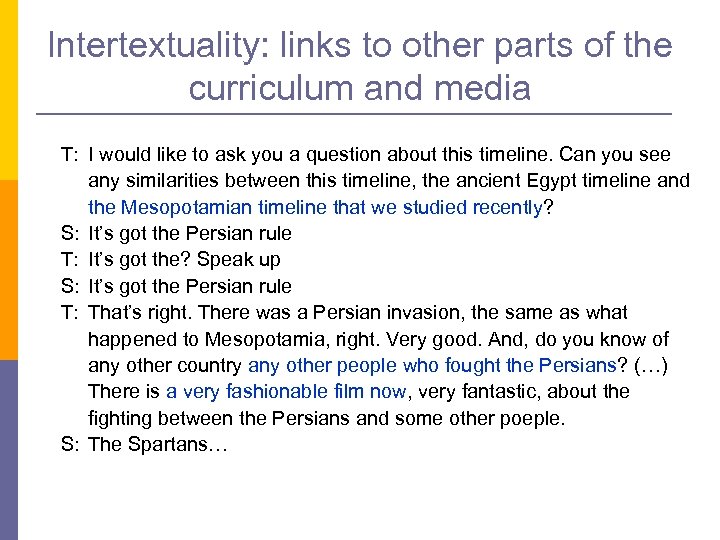

Intertextuality: links to other parts of the curriculum and media T: I would like to ask you a question about this timeline. Can you see any similarities between this timeline, the ancient Egypt timeline and the Mesopotamian timeline that we studied recently? S: It’s got the Persian rule T: It’s got the? Speak up S: It’s got the Persian rule T: That’s right. There was a Persian invasion, the same as what happened to Mesopotamia, right. Very good. And, do you know of any other country any other people who fought the Persians? (…) There is a very fashionable film now, very fantastic, about the fighting between the Persians and some other poeple. S: The Spartans…

Intertextuality: links to other parts of the curriculum and media T: I would like to ask you a question about this timeline. Can you see any similarities between this timeline, the ancient Egypt timeline and the Mesopotamian timeline that we studied recently? S: It’s got the Persian rule T: It’s got the? Speak up S: It’s got the Persian rule T: That’s right. There was a Persian invasion, the same as what happened to Mesopotamia, right. Very good. And, do you know of any other country any other people who fought the Persians? (…) There is a very fashionable film now, very fantastic, about the fighting between the Persians and some other poeple. S: The Spartans…

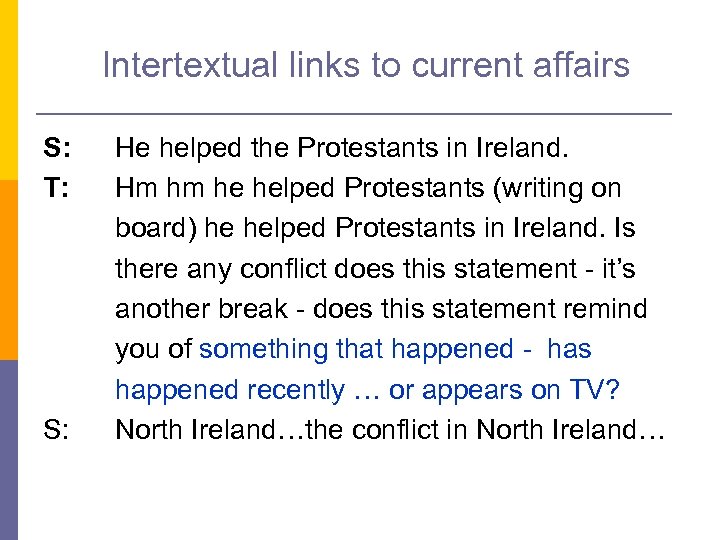

Intertextual links to current affairs S: T: S: He helped the Protestants in Ireland. Hm hm he helped Protestants (writing on board) he helped Protestants in Ireland. Is there any conflict does this statement - it’s another break - does this statement remind you of something that happened - has happened recently … or appears on TV? North Ireland…the conflict in North Ireland…

Intertextual links to current affairs S: T: S: He helped the Protestants in Ireland. Hm hm he helped Protestants (writing on board) he helped Protestants in Ireland. Is there any conflict does this statement - it’s another break - does this statement remind you of something that happened - has happened recently … or appears on TV? North Ireland…the conflict in North Ireland…

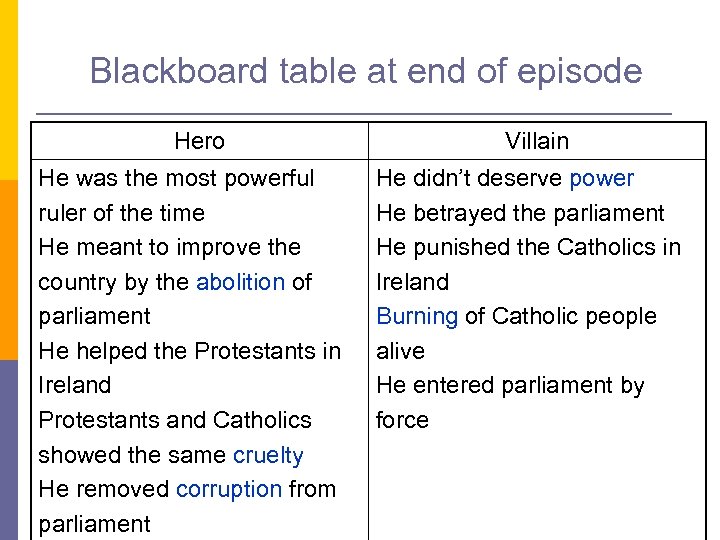

Blackboard table at end of episode Hero He was the most powerful ruler of the time He meant to improve the country by the abolition of parliament He helped the Protestants in Ireland Protestants and Catholics showed the same cruelty He removed corruption from parliament Villain He didn’t deserve power He betrayed the parliament He punished the Catholics in Ireland Burning of Catholic people alive He entered parliament by force

Blackboard table at end of episode Hero He was the most powerful ruler of the time He meant to improve the country by the abolition of parliament He helped the Protestants in Ireland Protestants and Catholics showed the same cruelty He removed corruption from parliament Villain He didn’t deserve power He betrayed the parliament He punished the Catholics in Ireland Burning of Catholic people alive He entered parliament by force

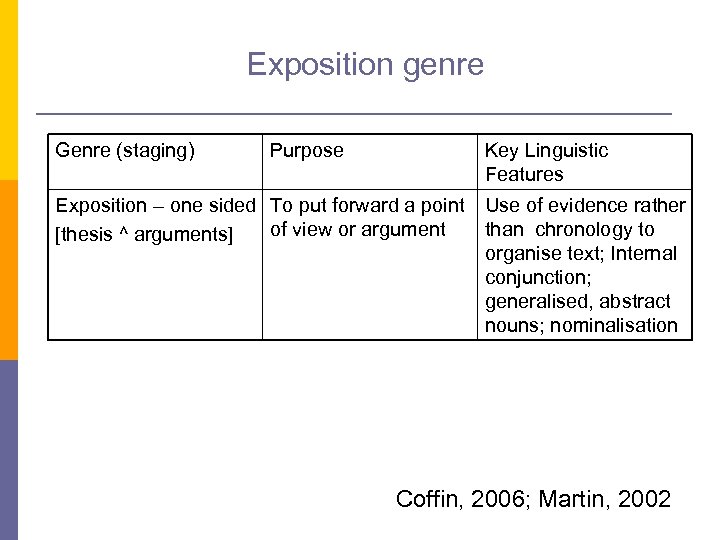

Exposition genre Genre (staging) Purpose Key Linguistic Features Exposition – one sided To put forward a point of view or argument [thesis ^ arguments] Use of evidence rather than chronology to organise text; Internal conjunction; generalised, abstract nouns; nominalisation Coffin, 2006; Martin, 2002

Exposition genre Genre (staging) Purpose Key Linguistic Features Exposition – one sided To put forward a point of view or argument [thesis ^ arguments] Use of evidence rather than chronology to organise text; Internal conjunction; generalised, abstract nouns; nominalisation Coffin, 2006; Martin, 2002

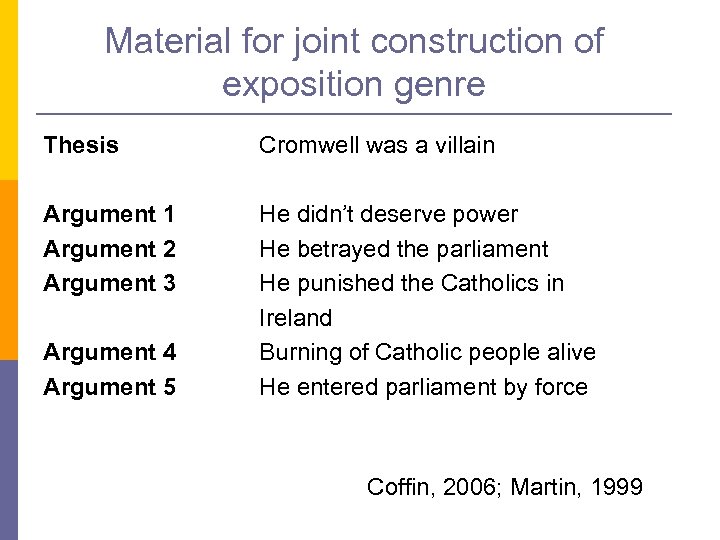

Material for joint construction of exposition genre Thesis Cromwell was a villain Argument 1 Argument 2 Argument 3 He didn’t deserve power He betrayed the parliament He punished the Catholics in Ireland Burning of Catholic people alive He entered parliament by force Argument 4 Argument 5 Coffin, 2006; Martin, 1999

Material for joint construction of exposition genre Thesis Cromwell was a villain Argument 1 Argument 2 Argument 3 He didn’t deserve power He betrayed the parliament He punished the Catholics in Ireland Burning of Catholic people alive He entered parliament by force Argument 4 Argument 5 Coffin, 2006; Martin, 1999

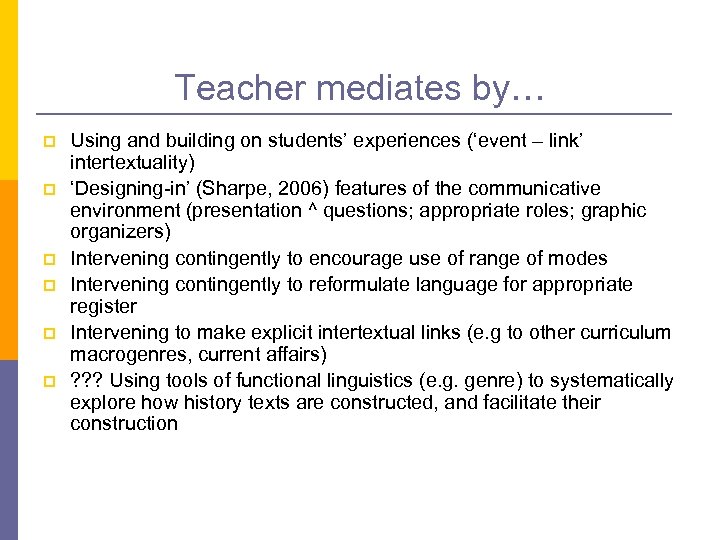

Teacher mediates by… p p p Using and building on students’ experiences (‘event – link’ intertextuality) ‘Designing-in’ (Sharpe, 2006) features of the communicative environment (presentation ^ questions; appropriate roles; graphic organizers) Intervening contingently to encourage use of range of modes Intervening contingently to reformulate language for appropriate register Intervening to make explicit intertextual links (e. g to other curriculum macrogenres, current affairs) ? ? ? Using tools of functional linguistics (e. g. genre) to systematically explore how history texts are constructed, and facilitate their construction

Teacher mediates by… p p p Using and building on students’ experiences (‘event – link’ intertextuality) ‘Designing-in’ (Sharpe, 2006) features of the communicative environment (presentation ^ questions; appropriate roles; graphic organizers) Intervening contingently to encourage use of range of modes Intervening contingently to reformulate language for appropriate register Intervening to make explicit intertextual links (e. g to other curriculum macrogenres, current affairs) ? ? ? Using tools of functional linguistics (e. g. genre) to systematically explore how history texts are constructed, and facilitate their construction

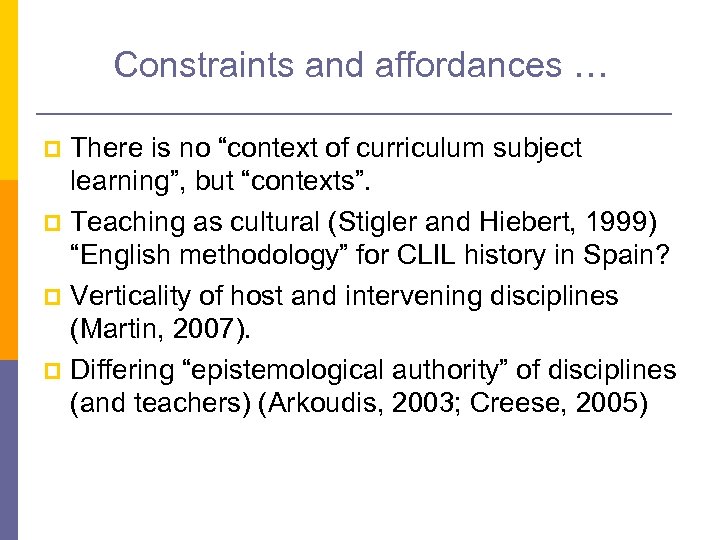

Constraints and affordances … There is no “context of curriculum subject learning”, but “contexts”. p Teaching as cultural (Stigler and Hiebert, 1999) “English methodology” for CLIL history in Spain? p Verticality of host and intervening disciplines (Martin, 2007). p Differing “epistemological authority” of disciplines (and teachers) (Arkoudis, 2003; Creese, 2005) p

Constraints and affordances … There is no “context of curriculum subject learning”, but “contexts”. p Teaching as cultural (Stigler and Hiebert, 1999) “English methodology” for CLIL history in Spain? p Verticality of host and intervening disciplines (Martin, 2007). p Differing “epistemological authority” of disciplines (and teachers) (Arkoudis, 2003; Creese, 2005) p

Constraints and affordances cont’d What are the desired outcomes in disciplinary learning? A “grasp of practice”? (Ford and Forman, 2006) p What are the language and literacy implications of “Guiding principles for disciplinary engagement” (Engle and Conant, 2002), particularly providing resources? p Is CLIL a “competence-based” pedagogy (in Bernstein’s term) at least as far as language is concerned? (see Leung, 2001 on EAL as ‘diffused curriculum concern’). p

Constraints and affordances cont’d What are the desired outcomes in disciplinary learning? A “grasp of practice”? (Ford and Forman, 2006) p What are the language and literacy implications of “Guiding principles for disciplinary engagement” (Engle and Conant, 2002), particularly providing resources? p Is CLIL a “competence-based” pedagogy (in Bernstein’s term) at least as far as language is concerned? (see Leung, 2001 on EAL as ‘diffused curriculum concern’). p

2 approaches to teaching history §Students should be instructed in historical reasoning (i. e. , the way expert historians think when producing historical knowledge). §Students are presented with materials to be worked on, or discussions to be carried out, so that they not only have to understand the narrative but get immersed in the process of making history with the resources provided. Blanco and Rosa, 1994: 195

2 approaches to teaching history §Students should be instructed in historical reasoning (i. e. , the way expert historians think when producing historical knowledge). §Students are presented with materials to be worked on, or discussions to be carried out, so that they not only have to understand the narrative but get immersed in the process of making history with the resources provided. Blanco and Rosa, 1994: 195

What do learners take away? “Any consideration of history teaching should take into account what use learners will make of history after they have been exposed to it. ” (Blanco and Rosa, 1994: 197) A ‘dual-focused’ approach such as CLIL should also take into account what learners will ‘take away’ in terms of literacy and language skills.

What do learners take away? “Any consideration of history teaching should take into account what use learners will make of history after they have been exposed to it. ” (Blanco and Rosa, 1994: 197) A ‘dual-focused’ approach such as CLIL should also take into account what learners will ‘take away’ in terms of literacy and language skills.

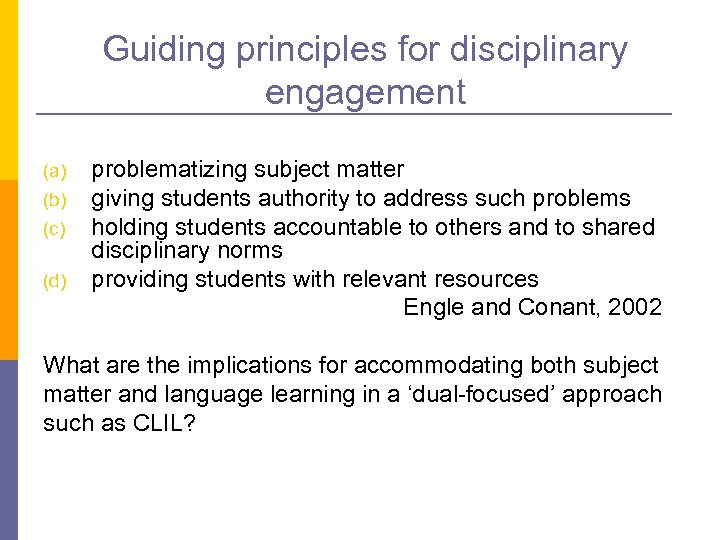

Guiding principles for disciplinary engagement (a) (b) (c) (d) problematizing subject matter giving students authority to address such problems holding students accountable to others and to shared disciplinary norms providing students with relevant resources Engle and Conant, 2002 What are the implications for accommodating both subject matter and language learning in a ‘dual-focused’ approach such as CLIL?

Guiding principles for disciplinary engagement (a) (b) (c) (d) problematizing subject matter giving students authority to address such problems holding students accountable to others and to shared disciplinary norms providing students with relevant resources Engle and Conant, 2002 What are the implications for accommodating both subject matter and language learning in a ‘dual-focused’ approach such as CLIL?

A functional approach as a way forward for CLIL “Instead of using content as a vehicle for teaching language, we use language as a means of teaching content. ” Schleppegrell and de Oliveira, 2006: 255

A functional approach as a way forward for CLIL “Instead of using content as a vehicle for teaching language, we use language as a means of teaching content. ” Schleppegrell and de Oliveira, 2006: 255

Raising expectations… Teachers can design classroom activities that require complex thinking and language patterns valued in academia (and in the professional world). Rather than fact-based charts, fill-in-the-blank worksheets, end-of chapter questions, and formulaic essays, teachers can create scenarios where students think deeply about the facts and concepts and communicate in academic ways in order to accomplish complex, real-world tasks. Zwiers, 2007: 113

Raising expectations… Teachers can design classroom activities that require complex thinking and language patterns valued in academia (and in the professional world). Rather than fact-based charts, fill-in-the-blank worksheets, end-of chapter questions, and formulaic essays, teachers can create scenarios where students think deeply about the facts and concepts and communicate in academic ways in order to accomplish complex, real-world tasks. Zwiers, 2007: 113