3d3124d43ad58139a741af204a68ff66.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 77

Health Sector PERS PEAM Course March 2005, Washington, D. C. George Schieber Health Policy Advisor Human Development Network

Health Sector PERS PEAM Course March 2005, Washington, D. C. George Schieber Health Policy Advisor Human Development Network

Organization of Presentation • • Health Systems Reform Basics Underlying Health Dynamics Health Expenditures Fundamentals of Health Financing Provider Payment Health Reform Issues Implementation

Organization of Presentation • • Health Systems Reform Basics Underlying Health Dynamics Health Expenditures Fundamentals of Health Financing Provider Payment Health Reform Issues Implementation

Health Systems Reform Basics

Health Systems Reform Basics

Objectives of Health Systems • • Improve health status of population Assure equity and universal access Provide financial protection Be efficient from macroeconomic and microeconomic perspectives • Assure quality of care and consumer satisfaction

Objectives of Health Systems • • Improve health status of population Assure equity and universal access Provide financial protection Be efficient from macroeconomic and microeconomic perspectives • Assure quality of care and consumer satisfaction

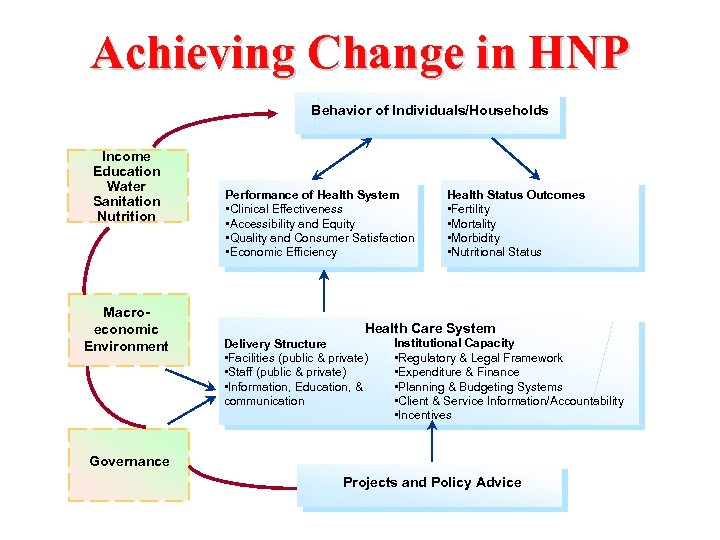

Achieving Change in HNP Behavior of Individuals/Households Income Education Water Sanitation Nutrition Macroeconomic Environment Performance of Health System • Clinical Effectiveness • Accessibility and Equity • Quality and Consumer Satisfaction • Economic Efficiency Health Status Outcomes • Fertility • Mortality • Morbidity • Nutritional Status Health Care System Delivery Structure • Facilities (public & private) • Staff (public & private) • Information, Education, & communication Institutional Capacity • Regulatory & Legal Framework • Expenditure & Finance • Planning & Budgeting Systems • Client & Service Information/Accountability • Incentives Governance Projects and Policy Advice

Achieving Change in HNP Behavior of Individuals/Households Income Education Water Sanitation Nutrition Macroeconomic Environment Performance of Health System • Clinical Effectiveness • Accessibility and Equity • Quality and Consumer Satisfaction • Economic Efficiency Health Status Outcomes • Fertility • Mortality • Morbidity • Nutritional Status Health Care System Delivery Structure • Facilities (public & private) • Staff (public & private) • Information, Education, & communication Institutional Capacity • Regulatory & Legal Framework • Expenditure & Finance • Planning & Budgeting Systems • Client & Service Information/Accountability • Incentives Governance Projects and Policy Advice

Why Public Intervention? • Health services with collective benefits (public verses personal health services) • Redistribution/Equity • Health insurance market failures • Other market failures in the direct consumption and provision of health services

Why Public Intervention? • Health services with collective benefits (public verses personal health services) • Redistribution/Equity • Health insurance market failures • Other market failures in the direct consumption and provision of health services

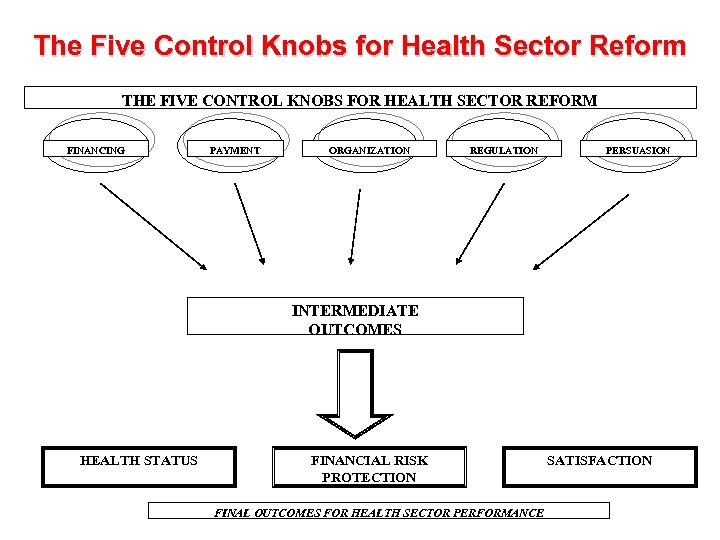

The Five Control Knobs for Health Sector Reform THE FIVE CONTROL KNOBS FOR HEALTH SECTOR REFORM FINANCING PAYMENT ORGANIZATION REGULATION PERSUASION INTERMEDIATE OUTCOMES HEALTH STATUS FINANCIAL RISK PROTECTION FINAL OUTCOMES FOR HEALTH SECTOR PERFORMANCE SATISFACTION

The Five Control Knobs for Health Sector Reform THE FIVE CONTROL KNOBS FOR HEALTH SECTOR REFORM FINANCING PAYMENT ORGANIZATION REGULATION PERSUASION INTERMEDIATE OUTCOMES HEALTH STATUS FINANCIAL RISK PROTECTION FINAL OUTCOMES FOR HEALTH SECTOR PERFORMANCE SATISFACTION

Underlying Health Dynamics

Underlying Health Dynamics

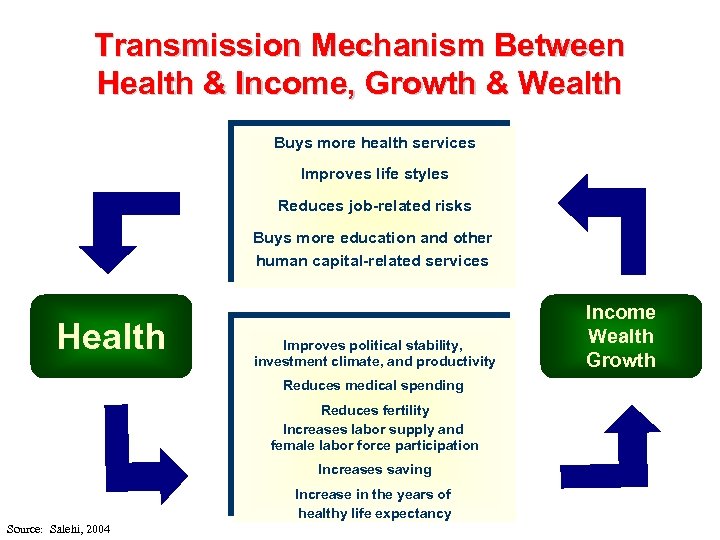

Transmission Mechanism Between Health & Income, Growth & Wealth Buys more health services Improves life styles Reduces job-related risks Buys more education and other human capital-related services Health Improves political stability, investment climate, and productivity Reduces medical spending Reduces fertility Increases labor supply and female labor force participation Increases saving Increase in the years of healthy life expectancy Source: Salehi, 2004 Income Wealth Growth

Transmission Mechanism Between Health & Income, Growth & Wealth Buys more health services Improves life styles Reduces job-related risks Buys more education and other human capital-related services Health Improves political stability, investment climate, and productivity Reduces medical spending Reduces fertility Increases labor supply and female labor force participation Increases saving Increase in the years of healthy life expectancy Source: Salehi, 2004 Income Wealth Growth

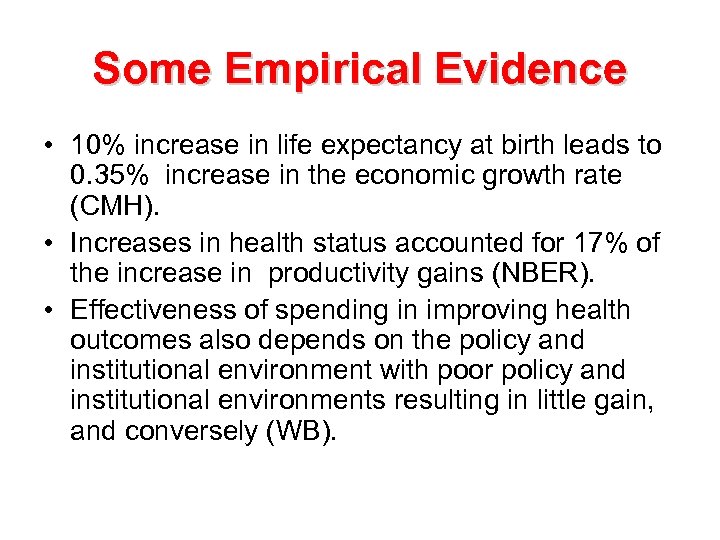

Some Empirical Evidence • 10% increase in life expectancy at birth leads to 0. 35% increase in the economic growth rate (CMH). • Increases in health status accounted for 17% of the increase in productivity gains (NBER). • Effectiveness of spending in improving health outcomes also depends on the policy and institutional environment with poor policy and institutional environments resulting in little gain, and conversely (WB).

Some Empirical Evidence • 10% increase in life expectancy at birth leads to 0. 35% increase in the economic growth rate (CMH). • Increases in health status accounted for 17% of the increase in productivity gains (NBER). • Effectiveness of spending in improving health outcomes also depends on the policy and institutional environment with poor policy and institutional environments resulting in little gain, and conversely (WB).

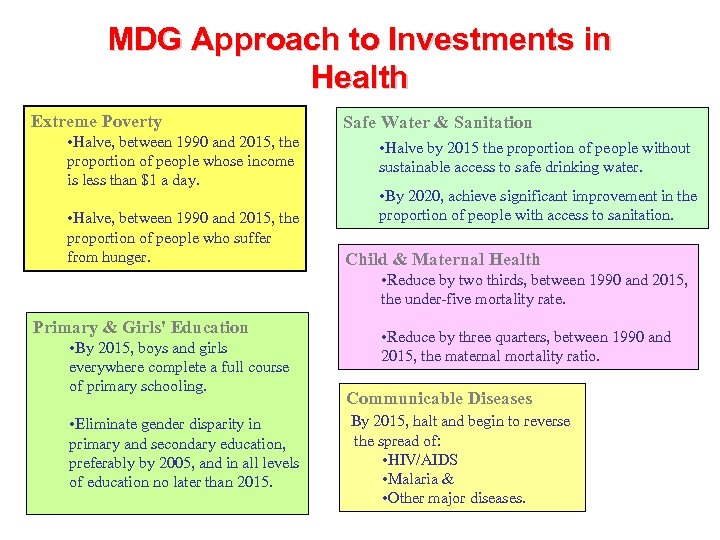

MDG Approach to Investments in Health Extreme Poverty • Halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people whose income is less than $1 a day. • Halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people who suffer from hunger. Safe Water & Sanitation • Halve by 2015 the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water. • By 2020, achieve significant improvement in the proportion of people with access to sanitation. Child & Maternal Health • Reduce by two thirds, between 1990 and 2015, the under-five mortality rate. Primary & Girls' Education • By 2015, boys and girls everywhere complete a full course of primary schooling. • Eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education, preferably by 2005, and in all levels of education no later than 2015. • Reduce by three quarters, between 1990 and 2015, the maternal mortality ratio. Communicable Diseases By 2015, halt and begin to reverse the spread of: • HIV/AIDS • Malaria & • Other major diseases.

MDG Approach to Investments in Health Extreme Poverty • Halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people whose income is less than $1 a day. • Halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people who suffer from hunger. Safe Water & Sanitation • Halve by 2015 the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water. • By 2020, achieve significant improvement in the proportion of people with access to sanitation. Child & Maternal Health • Reduce by two thirds, between 1990 and 2015, the under-five mortality rate. Primary & Girls' Education • By 2015, boys and girls everywhere complete a full course of primary schooling. • Eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education, preferably by 2005, and in all levels of education no later than 2015. • Reduce by three quarters, between 1990 and 2015, the maternal mortality ratio. Communicable Diseases By 2015, halt and begin to reverse the spread of: • HIV/AIDS • Malaria & • Other major diseases.

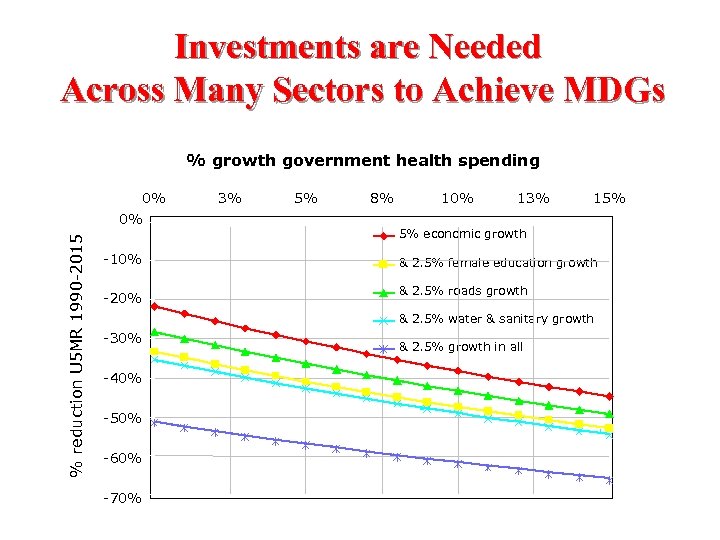

Investments are Needed Across Many Sectors to Achieve MDGs % growth government health spending % reduction U 5 MR 1990 -2015 0% 0% 3% 5% 8% 10% 13% 15% 5% economic growth -10% & 2. 5% female education growth -20% & 2. 5% roads growth & 2. 5% water & sanitary growth -30% -40% -50% -60% -70% & 2. 5% growth in all

Investments are Needed Across Many Sectors to Achieve MDGs % growth government health spending % reduction U 5 MR 1990 -2015 0% 0% 3% 5% 8% 10% 13% 15% 5% economic growth -10% & 2. 5% female education growth -20% & 2. 5% roads growth & 2. 5% water & sanitary growth -30% -40% -50% -60% -70% & 2. 5% growth in all

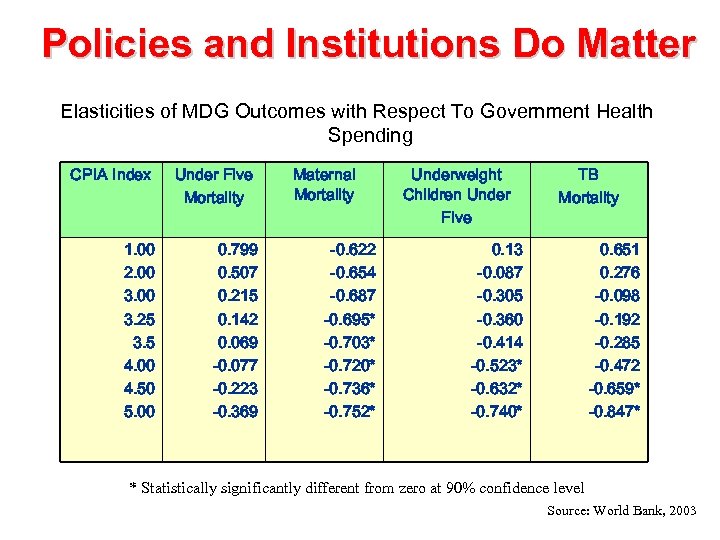

Policies and Institutions Do Matter Elasticities of MDG Outcomes with Respect To Government Health Spending CPIA Index 1. 00 2. 00 3. 25 3. 5 4. 00 4. 50 5. 00 Under Five Mortality 0. 799 0. 507 0. 215 0. 142 0. 069 -0. 077 -0. 223 -0. 369 Maternal Mortality -0. 622 -0. 654 -0. 687 -0. 695* -0. 703* -0. 720* -0. 736* -0. 752* Underweight Children Under Five TB Mortality 0. 13 -0. 087 -0. 305 -0. 360 -0. 414 -0. 523* -0. 632* -0. 740* 0. 651 0. 276 -0. 098 -0. 192 -0. 285 -0. 472 -0. 659* -0. 847* * Statistically significantly different from zero at 90% confidence level Source: World Bank, 2003

Policies and Institutions Do Matter Elasticities of MDG Outcomes with Respect To Government Health Spending CPIA Index 1. 00 2. 00 3. 25 3. 5 4. 00 4. 50 5. 00 Under Five Mortality 0. 799 0. 507 0. 215 0. 142 0. 069 -0. 077 -0. 223 -0. 369 Maternal Mortality -0. 622 -0. 654 -0. 687 -0. 695* -0. 703* -0. 720* -0. 736* -0. 752* Underweight Children Under Five TB Mortality 0. 13 -0. 087 -0. 305 -0. 360 -0. 414 -0. 523* -0. 632* -0. 740* 0. 651 0. 276 -0. 098 -0. 192 -0. 285 -0. 472 -0. 659* -0. 847* * Statistically significantly different from zero at 90% confidence level Source: World Bank, 2003

Cost-effective Interventions are Key to the MDGs • • • Which interventions to choose? How to transfer them to many countries? How to implement them to scale? How much will they cost? What kind of supporting environment is needed? • Can we monitor their impact?

Cost-effective Interventions are Key to the MDGs • • • Which interventions to choose? How to transfer them to many countries? How to implement them to scale? How much will they cost? What kind of supporting environment is needed? • Can we monitor their impact?

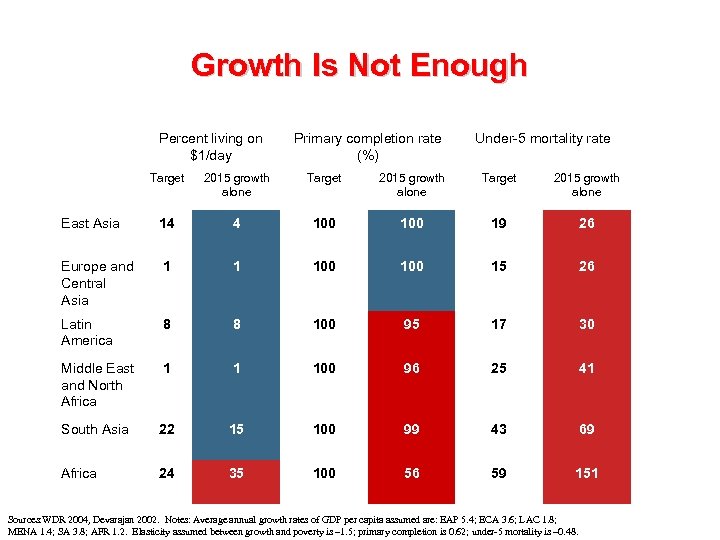

Growth Is Not Enough Percent living on $1/day Primary completion rate (%) Under-5 mortality rate Target 2015 growth alone East Asia 14 4 100 19 26 Europe and Central Asia 1 1 100 15 26 Latin America 8 8 100 95 17 30 Middle East and North Africa 1 1 100 96 25 41 South Asia 22 15 100 99 43 69 Africa 24 35 100 56 59 151 Sources: WDR 2004, Devarajan 2002. Notes: Average annual growth rates of GDP per capita assumed are: EAP 5. 4; ECA 3. 6; LAC 1. 8; MENA 1. 4; SA 3. 8; AFR 1. 2. Elasticity assumed between growth and poverty is – 1. 5; primary completion is 0. 62; under-5 mortality is – 0. 48.

Growth Is Not Enough Percent living on $1/day Primary completion rate (%) Under-5 mortality rate Target 2015 growth alone East Asia 14 4 100 19 26 Europe and Central Asia 1 1 100 15 26 Latin America 8 8 100 95 17 30 Middle East and North Africa 1 1 100 96 25 41 South Asia 22 15 100 99 43 69 Africa 24 35 100 56 59 151 Sources: WDR 2004, Devarajan 2002. Notes: Average annual growth rates of GDP per capita assumed are: EAP 5. 4; ECA 3. 6; LAC 1. 8; MENA 1. 4; SA 3. 8; AFR 1. 2. Elasticity assumed between growth and poverty is – 1. 5; primary completion is 0. 62; under-5 mortality is – 0. 48.

Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction Do we know what works? • • • Poverty reduction can be achieved by economic growth and/or by changing the distribution of income While growth in itself is not a sufficient condition for poverty reduction, it is a critical enabling factor for significant reductions over time Most poverty reduction is in those countries that have experienced sustained periods of economic growth and those with lower initial levels of inequality and poverty A 1% rate of growth in average household income or consumption drops the poverty rate from between 0. 6% to 3. 5% Financial development, trade openness and increases in the size of government are associated with higher growth but increases in inequality, ceteris paribus Recent studies suggest that policy makers should focus on sectors, regions, and factors of production dominated by the poor; redistributive spending focused on the HD assets of the poor; and gender inequalities as there is evidence that improvements in these areas as well as lower inflation lead to both growth and progressive redistribution Source: WB, PREM, Poverty Reduction Group

Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction Do we know what works? • • • Poverty reduction can be achieved by economic growth and/or by changing the distribution of income While growth in itself is not a sufficient condition for poverty reduction, it is a critical enabling factor for significant reductions over time Most poverty reduction is in those countries that have experienced sustained periods of economic growth and those with lower initial levels of inequality and poverty A 1% rate of growth in average household income or consumption drops the poverty rate from between 0. 6% to 3. 5% Financial development, trade openness and increases in the size of government are associated with higher growth but increases in inequality, ceteris paribus Recent studies suggest that policy makers should focus on sectors, regions, and factors of production dominated by the poor; redistributive spending focused on the HD assets of the poor; and gender inequalities as there is evidence that improvements in these areas as well as lower inflation lead to both growth and progressive redistribution Source: WB, PREM, Poverty Reduction Group

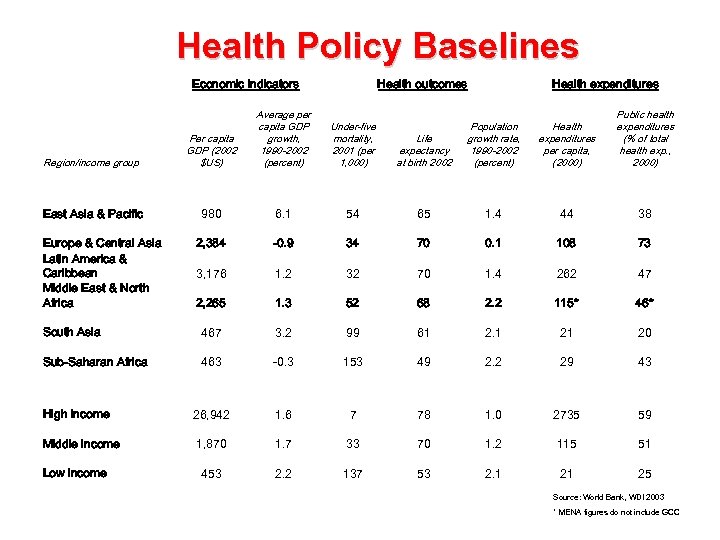

Health Policy Baselines Economic indicators Health outcomes Region/income group Per capita GDP (2002 $US) Average per capita GDP growth, 1990 -2002 (percent) Under-five mortality, 2001 (per 1, 000) East Asia & Pacific 980 6. 1 2, 384 Health expenditures Life expectancy at birth 2002 Population growth rate, 1990 -2002 (percent) Health expenditures per capita, (2000) Public health expenditures (% of total health exp. , 2000) 54 65 1. 4 44 38 -0. 9 34 70 0. 1 108 73 3, 176 1. 2 32 70 1. 4 262 47 2, 265 1. 3 52 68 2. 2 115* 46* South Asia 467 3. 2 99 61 2. 1 21 20 Sub-Saharan Africa 463 -0. 3 153 49 2. 2 29 43 High income 26, 942 1. 6 7 78 1. 0 2735 59 Middle income 1, 870 1. 7 33 70 1. 2 115 51 453 2. 2 137 53 2. 1 21 25 Europe & Central Asia Latin America & Caribbean Middle East & North Africa Low income Source: World Bank, WDI 2003 * MENA figures do not include GCC

Health Policy Baselines Economic indicators Health outcomes Region/income group Per capita GDP (2002 $US) Average per capita GDP growth, 1990 -2002 (percent) Under-five mortality, 2001 (per 1, 000) East Asia & Pacific 980 6. 1 2, 384 Health expenditures Life expectancy at birth 2002 Population growth rate, 1990 -2002 (percent) Health expenditures per capita, (2000) Public health expenditures (% of total health exp. , 2000) 54 65 1. 4 44 38 -0. 9 34 70 0. 1 108 73 3, 176 1. 2 32 70 1. 4 262 47 2, 265 1. 3 52 68 2. 2 115* 46* South Asia 467 3. 2 99 61 2. 1 21 20 Sub-Saharan Africa 463 -0. 3 153 49 2. 2 29 43 High income 26, 942 1. 6 7 78 1. 0 2735 59 Middle income 1, 870 1. 7 33 70 1. 2 115 51 453 2. 2 137 53 2. 1 21 25 Europe & Central Asia Latin America & Caribbean Middle East & North Africa Low income Source: World Bank, WDI 2003 * MENA figures do not include GCC

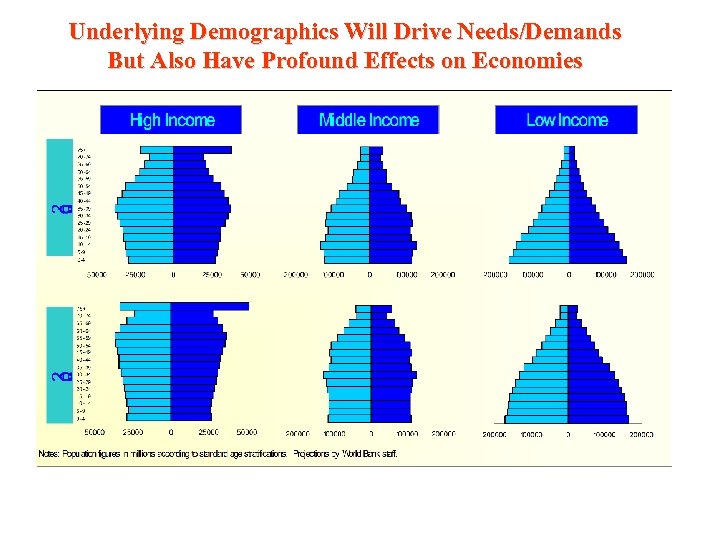

Underlying Demographics Will Drive Needs/Demands But Also Have Profound Effects on Economies

Underlying Demographics Will Drive Needs/Demands But Also Have Profound Effects on Economies

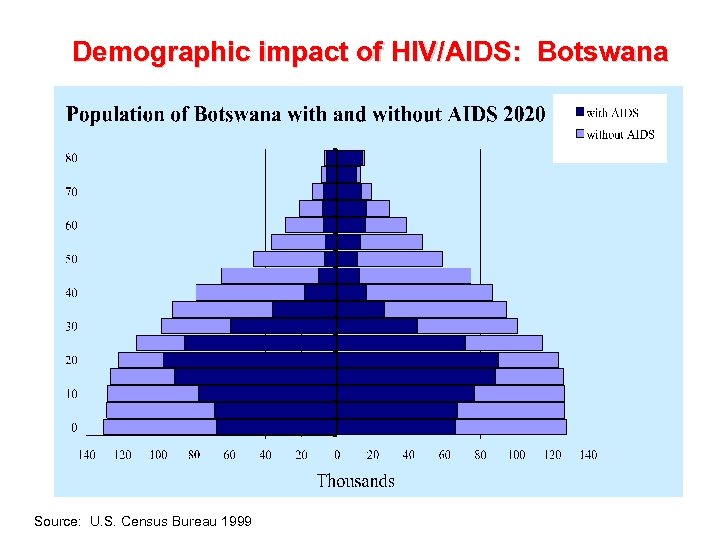

Demographic impact of HIV/AIDS: Botswana Source: U. S. Census Bureau 1999

Demographic impact of HIV/AIDS: Botswana Source: U. S. Census Bureau 1999

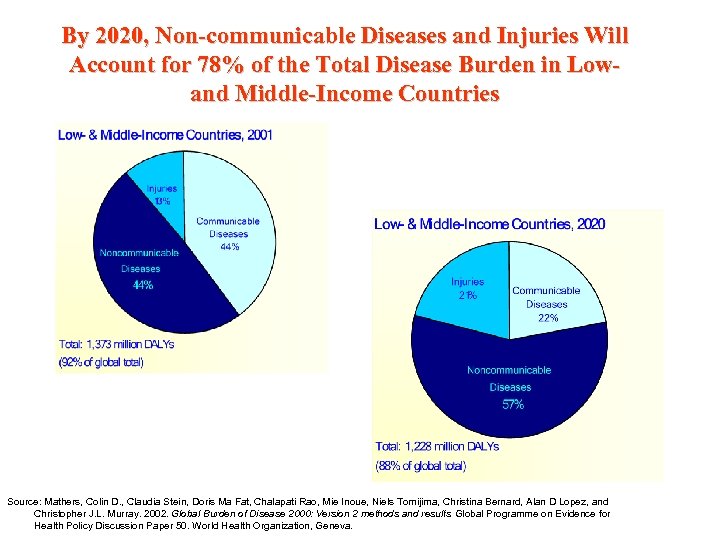

By 2020, Non-communicable Diseases and Injuries Will Account for 78% of the Total Disease Burden in Lowand Middle-Income Countries Source: Mathers, Colin D. , Claudia Stein, Doris Ma Fat, Chalapati Rao, Mie Inoue, Niels Tomijima, Christina Bernard, Alan D Lopez, and Christopher J. L. Murray. 2002. Global Burden of Disease 2000: Version 2 methods and results. Global Programme on Evidence for Health Policy Discussion Paper 50. World Health Organization, Geneva.

By 2020, Non-communicable Diseases and Injuries Will Account for 78% of the Total Disease Burden in Lowand Middle-Income Countries Source: Mathers, Colin D. , Claudia Stein, Doris Ma Fat, Chalapati Rao, Mie Inoue, Niels Tomijima, Christina Bernard, Alan D Lopez, and Christopher J. L. Murray. 2002. Global Burden of Disease 2000: Version 2 methods and results. Global Programme on Evidence for Health Policy Discussion Paper 50. World Health Organization, Geneva.

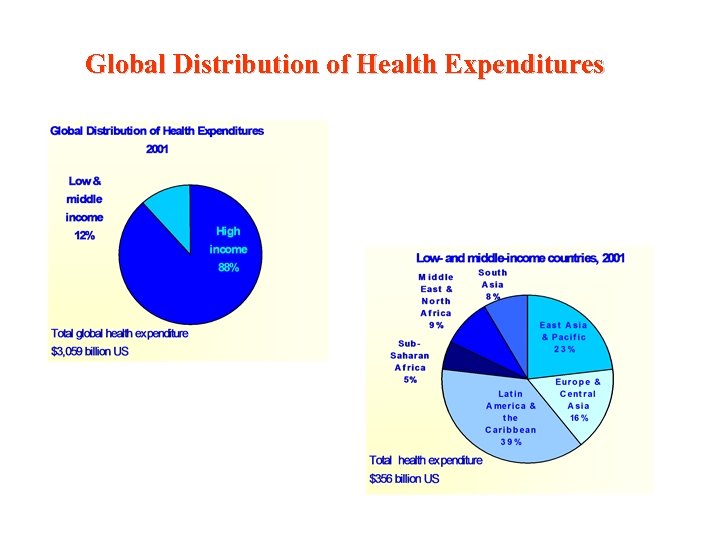

Global Distribution of Health Expenditures

Global Distribution of Health Expenditures

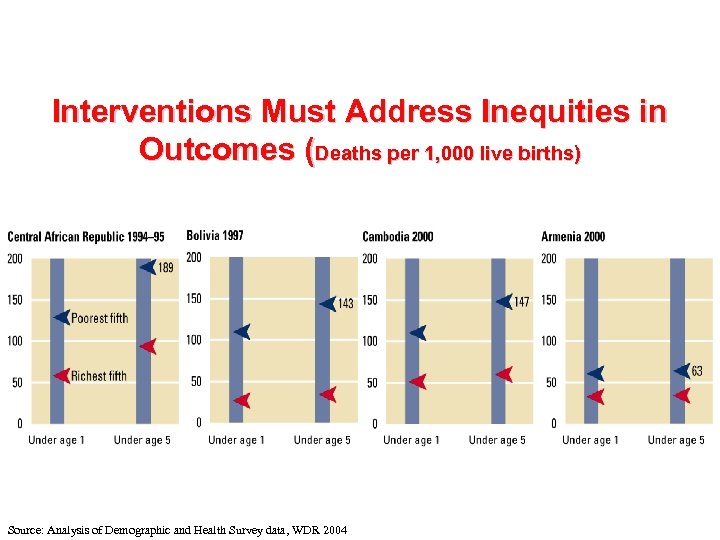

Interventions Must Address Inequities in Outcomes (Deaths per 1, 000 live births) Source: Analysis of Demographic and Health Survey data, WDR 2004

Interventions Must Address Inequities in Outcomes (Deaths per 1, 000 live births) Source: Analysis of Demographic and Health Survey data, WDR 2004

Health Expenditures

Health Expenditures

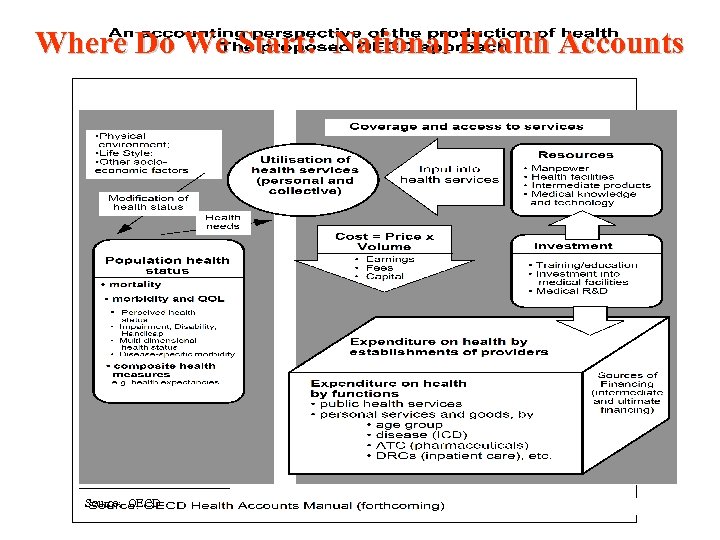

Where Do We Start: National Health Accounts Source: OECD

Where Do We Start: National Health Accounts Source: OECD

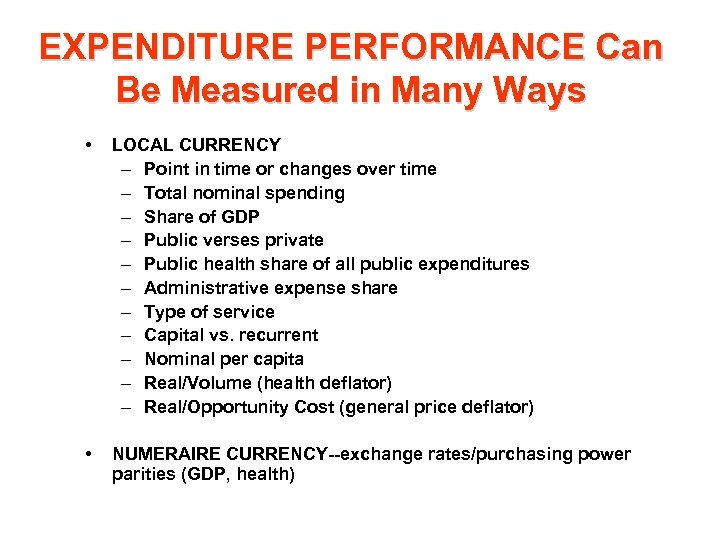

EXPENDITURE PERFORMANCE Can Be Measured in Many Ways • LOCAL CURRENCY – Point in time or changes over time – Total nominal spending – Share of GDP – Public verses private – Public health share of all public expenditures – Administrative expense share – Type of service – Capital vs. recurrent – Nominal per capita – Real/Volume (health deflator) – Real/Opportunity Cost (general price deflator) • NUMERAIRE CURRENCY--exchange rates/purchasing power parities (GDP, health)

EXPENDITURE PERFORMANCE Can Be Measured in Many Ways • LOCAL CURRENCY – Point in time or changes over time – Total nominal spending – Share of GDP – Public verses private – Public health share of all public expenditures – Administrative expense share – Type of service – Capital vs. recurrent – Nominal per capita – Real/Volume (health deflator) – Real/Opportunity Cost (general price deflator) • NUMERAIRE CURRENCY--exchange rates/purchasing power parities (GDP, health)

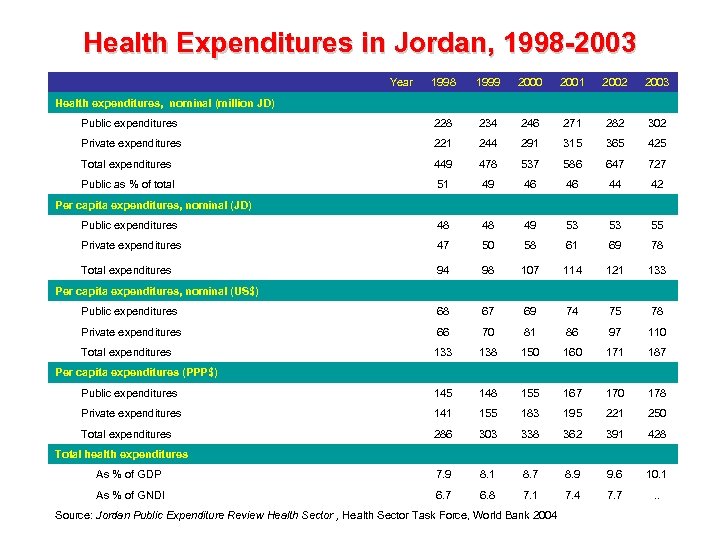

Health Expenditures in Jordan, 1998 -2003 Year 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Public expenditures 228 234 246 271 282 302 Private expenditures 221 244 291 315 365 425 Total expenditures 449 478 537 586 647 727 Public as % of total 51 49 46 46 44 42 Public expenditures 48 48 49 53 53 55 Private expenditures 47 50 58 61 69 78 Total expenditures 94 98 107 114 121 133 Public expenditures 68 67 69 74 75 78 Private expenditures 66 70 81 86 97 110 Total expenditures 133 138 150 160 171 187 Public expenditures 145 148 155 167 170 178 Private expenditures 141 155 183 195 221 250 Total expenditures 286 303 338 362 391 428 As % of GDP 7. 9 8. 1 8. 7 8. 9 9. 6 10. 1 As % of GNDI 6. 7 6. 8 7. 1 7. 4 7. 7 . . Health expenditures, nominal (million JD) Per capita expenditures, nominal (US$) Per capita expenditures (PPP$) Total health expenditures Source: Jordan Public Expenditure Review Health Sector , Health Sector Task Force, World Bank 2004

Health Expenditures in Jordan, 1998 -2003 Year 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Public expenditures 228 234 246 271 282 302 Private expenditures 221 244 291 315 365 425 Total expenditures 449 478 537 586 647 727 Public as % of total 51 49 46 46 44 42 Public expenditures 48 48 49 53 53 55 Private expenditures 47 50 58 61 69 78 Total expenditures 94 98 107 114 121 133 Public expenditures 68 67 69 74 75 78 Private expenditures 66 70 81 86 97 110 Total expenditures 133 138 150 160 171 187 Public expenditures 145 148 155 167 170 178 Private expenditures 141 155 183 195 221 250 Total expenditures 286 303 338 362 391 428 As % of GDP 7. 9 8. 1 8. 7 8. 9 9. 6 10. 1 As % of GNDI 6. 7 6. 8 7. 1 7. 4 7. 7 . . Health expenditures, nominal (million JD) Per capita expenditures, nominal (US$) Per capita expenditures (PPP$) Total health expenditures Source: Jordan Public Expenditure Review Health Sector , Health Sector Task Force, World Bank 2004

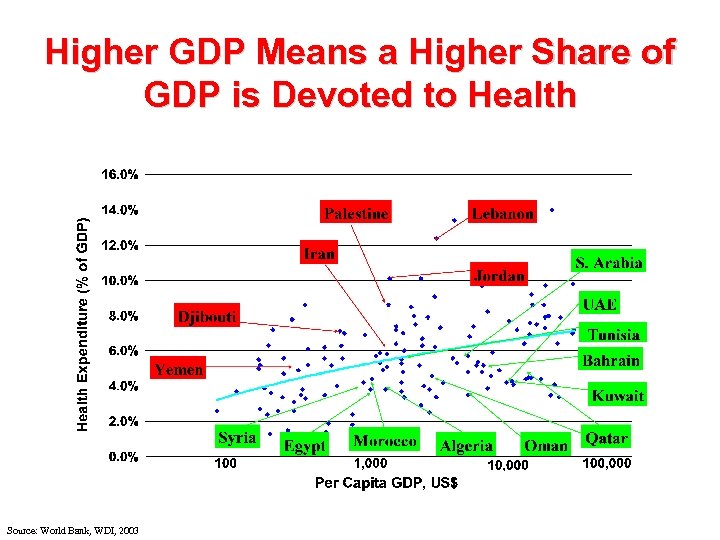

Higher GDP Means a Higher Share of GDP is Devoted to Health Source: World Bank, WDI, 2003

Higher GDP Means a Higher Share of GDP is Devoted to Health Source: World Bank, WDI, 2003

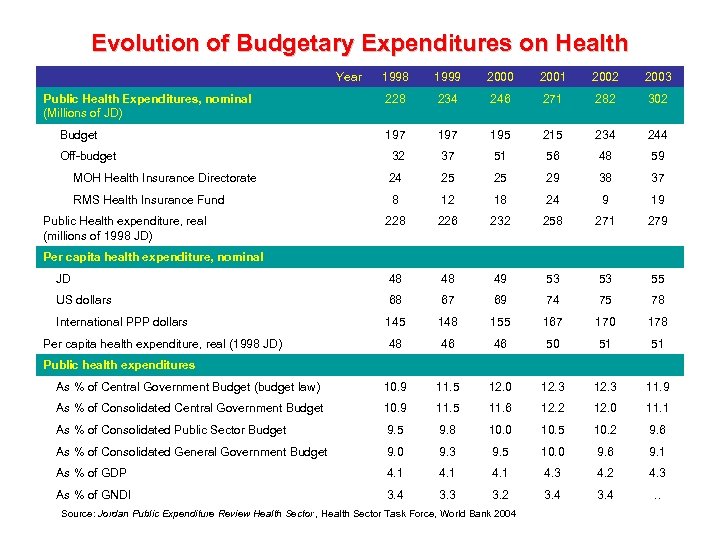

Evolution of Budgetary Expenditures on Health Year 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 228 234 246 271 282 302 197 195 215 234 244 32 37 51 56 48 59 MOH Health Insurance Directorate 24 25 25 29 38 37 RMS Health Insurance Fund 8 12 18 24 9 19 228 226 232 258 271 279 JD 48 48 49 53 53 55 US dollars 68 67 69 74 75 78 International PPP dollars 145 148 155 167 170 178 48 46 46 50 51 51 As % of Central Government Budget (budget law) 10. 9 11. 5 12. 0 12. 3 11. 9 As % of Consolidated Central Government Budget 10. 9 11. 5 11. 6 12. 2 12. 0 11. 1 As % of Consolidated Public Sector Budget 9. 5 9. 8 10. 0 10. 5 10. 2 9. 6 As % of Consolidated General Government Budget 9. 0 9. 3 9. 5 10. 0 9. 6 9. 1 As % of GDP 4. 1 4. 3 4. 2 4. 3 As % of GNDI 3. 4 3. 3 3. 2 3. 4 . . Public Health Expenditures, nominal (Millions of JD) Budget Off-budget Public Health expenditure, real (millions of 1998 JD) Per capita health expenditure, nominal Per capita health expenditure, real (1998 JD) Public health expenditures Source: Jordan Public Expenditure Review Health Sector , Health Sector Task Force, World Bank 2004

Evolution of Budgetary Expenditures on Health Year 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 228 234 246 271 282 302 197 195 215 234 244 32 37 51 56 48 59 MOH Health Insurance Directorate 24 25 25 29 38 37 RMS Health Insurance Fund 8 12 18 24 9 19 228 226 232 258 271 279 JD 48 48 49 53 53 55 US dollars 68 67 69 74 75 78 International PPP dollars 145 148 155 167 170 178 48 46 46 50 51 51 As % of Central Government Budget (budget law) 10. 9 11. 5 12. 0 12. 3 11. 9 As % of Consolidated Central Government Budget 10. 9 11. 5 11. 6 12. 2 12. 0 11. 1 As % of Consolidated Public Sector Budget 9. 5 9. 8 10. 0 10. 5 10. 2 9. 6 As % of Consolidated General Government Budget 9. 0 9. 3 9. 5 10. 0 9. 6 9. 1 As % of GDP 4. 1 4. 3 4. 2 4. 3 As % of GNDI 3. 4 3. 3 3. 2 3. 4 . . Public Health Expenditures, nominal (Millions of JD) Budget Off-budget Public Health expenditure, real (millions of 1998 JD) Per capita health expenditure, nominal Per capita health expenditure, real (1998 JD) Public health expenditures Source: Jordan Public Expenditure Review Health Sector , Health Sector Task Force, World Bank 2004

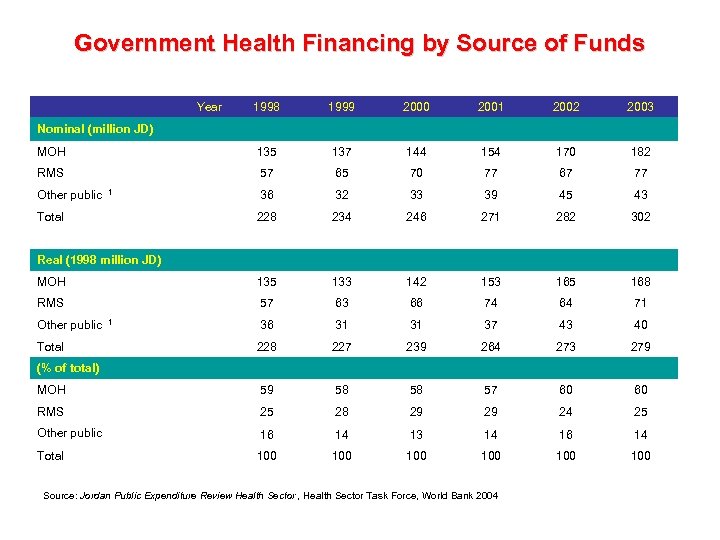

Government Health Financing by Source of Funds Year 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 MOH 135 137 144 154 170 182 RMS 57 65 70 77 67 77 36 32 33 39 45 43 228 234 246 271 282 302 MOH 135 133 142 153 165 168 RMS 57 63 66 74 64 71 36 31 31 37 43 40 228 227 239 264 273 279 MOH 59 58 58 57 60 60 RMS 25 28 29 29 24 25 Other public 16 14 13 14 16 14 Total 100 100 100 Nominal (million JD) Other public 1 Total Real (1998 million JD) Other public Total 1 (% of total) Source: Jordan Public Expenditure Review Health Sector , Health Sector Task Force, World Bank 2004

Government Health Financing by Source of Funds Year 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 MOH 135 137 144 154 170 182 RMS 57 65 70 77 67 77 36 32 33 39 45 43 228 234 246 271 282 302 MOH 135 133 142 153 165 168 RMS 57 63 66 74 64 71 36 31 31 37 43 40 228 227 239 264 273 279 MOH 59 58 58 57 60 60 RMS 25 28 29 29 24 25 Other public 16 14 13 14 16 14 Total 100 100 100 Nominal (million JD) Other public 1 Total Real (1998 million JD) Other public Total 1 (% of total) Source: Jordan Public Expenditure Review Health Sector , Health Sector Task Force, World Bank 2004

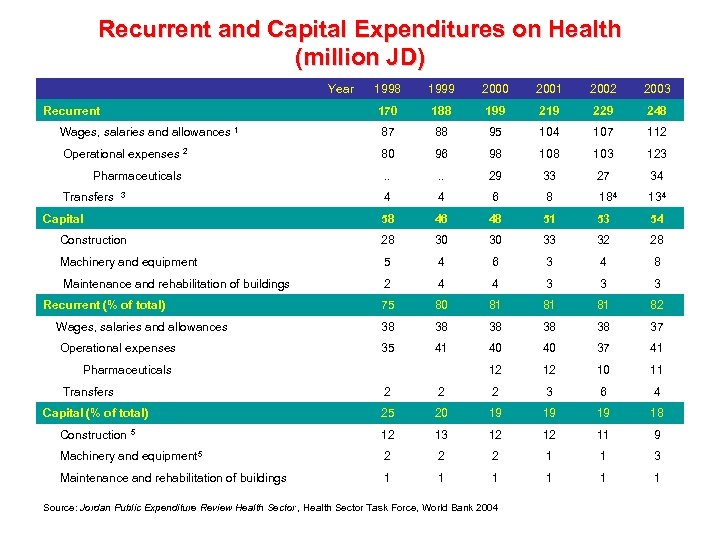

Recurrent and Capital Expenditures on Health (million JD) Year 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 170 188 199 219 229 248 Wages, salaries and allowances 1 87 88 95 104 107 112 Operational expenses 2 80 96 98 103 123 . . 29 33 27 34 4 4 6 8 184 134 58 46 48 51 53 54 Construction 28 30 30 33 32 28 Machinery and equipment 5 4 6 3 4 8 Maintenance and rehabilitation of buildings 2 4 4 3 3 3 75 80 81 81 81 82 Wages, salaries and allowances 38 38 38 37 Operational expenses 35 41 40 40 37 41 12 12 10 11 Recurrent Pharmaceuticals Transfers 3 Capital Recurrent (% of total) Pharmaceuticals Transfers 2 2 2 3 6 4 Capital (% of total) 25 20 19 19 19 18 Construction 5 12 13 12 12 11 9 Machinery and equipment 5 2 2 2 1 1 3 Maintenance and rehabilitation of buildings 1 1 1 Source: Jordan Public Expenditure Review Health Sector , Health Sector Task Force, World Bank 2004

Recurrent and Capital Expenditures on Health (million JD) Year 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 170 188 199 219 229 248 Wages, salaries and allowances 1 87 88 95 104 107 112 Operational expenses 2 80 96 98 103 123 . . 29 33 27 34 4 4 6 8 184 134 58 46 48 51 53 54 Construction 28 30 30 33 32 28 Machinery and equipment 5 4 6 3 4 8 Maintenance and rehabilitation of buildings 2 4 4 3 3 3 75 80 81 81 81 82 Wages, salaries and allowances 38 38 38 37 Operational expenses 35 41 40 40 37 41 12 12 10 11 Recurrent Pharmaceuticals Transfers 3 Capital Recurrent (% of total) Pharmaceuticals Transfers 2 2 2 3 6 4 Capital (% of total) 25 20 19 19 19 18 Construction 5 12 13 12 12 11 9 Machinery and equipment 5 2 2 2 1 1 3 Maintenance and rehabilitation of buildings 1 1 1 Source: Jordan Public Expenditure Review Health Sector , Health Sector Task Force, World Bank 2004

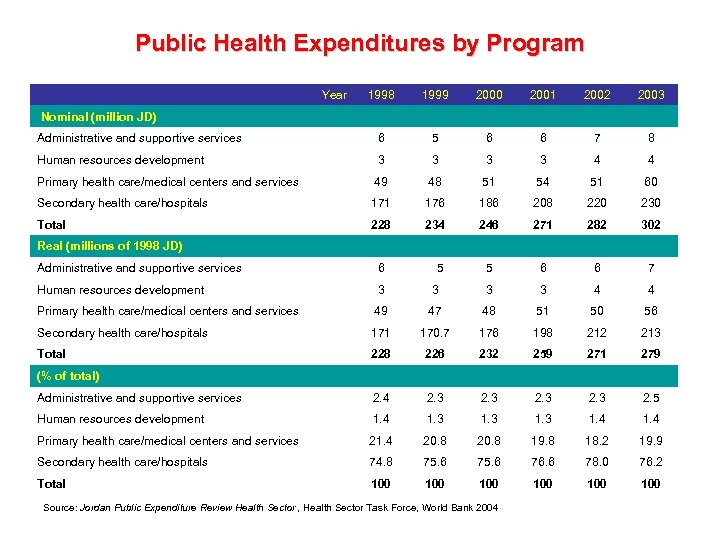

Public Health Expenditures by Program Year 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Administrative and supportive services 6 5 6 6 7 8 Human resources development 3 3 4 4 Primary health care/medical centers and services 49 48 51 54 51 60 Secondary health care/hospitals 171 176 186 208 220 230 Total 228 234 246 271 282 302 5 6 6 7 Nominal (million JD) Real (millions of 1998 JD) Administrative and supportive services 6 5 Human resources development 3 3 4 4 Primary health care/medical centers and services 49 47 48 51 50 56 Secondary health care/hospitals 171 170. 7 176 198 212 213 Total 228 226 232 259 271 279 Administrative and supportive services 2. 4 2. 3 2. 5 Human resources development 1. 4 1. 3 1. 4 Primary health care/medical centers and services 21. 4 20. 8 19. 8 18. 2 19. 9 Secondary health care/hospitals 74. 8 75. 6 76. 6 78. 0 76. 2 Total 100 100 100 (% of total) Source: Jordan Public Expenditure Review Health Sector , Health Sector Task Force, World Bank 2004

Public Health Expenditures by Program Year 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Administrative and supportive services 6 5 6 6 7 8 Human resources development 3 3 4 4 Primary health care/medical centers and services 49 48 51 54 51 60 Secondary health care/hospitals 171 176 186 208 220 230 Total 228 234 246 271 282 302 5 6 6 7 Nominal (million JD) Real (millions of 1998 JD) Administrative and supportive services 6 5 Human resources development 3 3 4 4 Primary health care/medical centers and services 49 47 48 51 50 56 Secondary health care/hospitals 171 170. 7 176 198 212 213 Total 228 226 232 259 271 279 Administrative and supportive services 2. 4 2. 3 2. 5 Human resources development 1. 4 1. 3 1. 4 Primary health care/medical centers and services 21. 4 20. 8 19. 8 18. 2 19. 9 Secondary health care/hospitals 74. 8 75. 6 76. 6 78. 0 76. 2 Total 100 100 100 (% of total) Source: Jordan Public Expenditure Review Health Sector , Health Sector Task Force, World Bank 2004

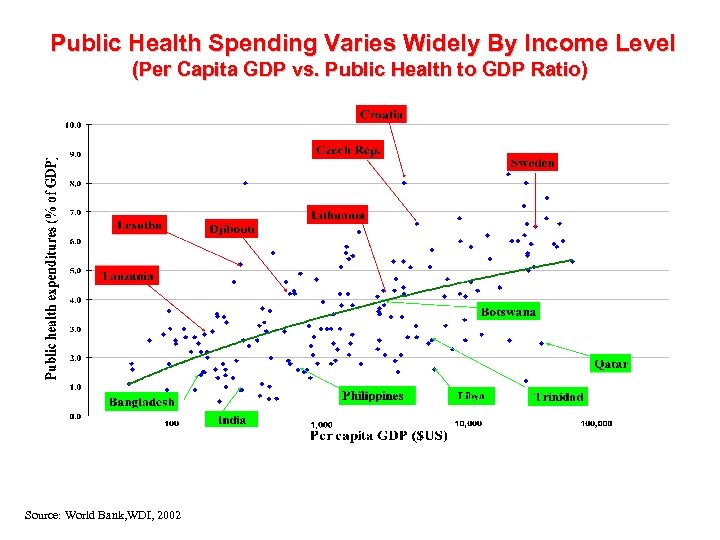

Public Health Spending Varies Widely By Income Level (Per Capita GDP vs. Public Health to GDP Ratio) Source: World Bank, WDI, 2002

Public Health Spending Varies Widely By Income Level (Per Capita GDP vs. Public Health to GDP Ratio) Source: World Bank, WDI, 2002

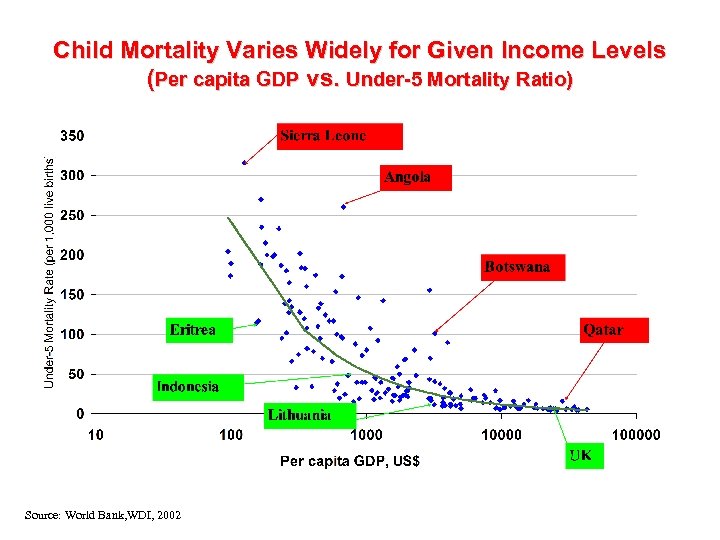

Child Mortality Varies Widely for Given Income Levels (Per capita GDP vs. Under-5 Mortality Ratio) Source: World Bank, WDI, 2002

Child Mortality Varies Widely for Given Income Levels (Per capita GDP vs. Under-5 Mortality Ratio) Source: World Bank, WDI, 2002

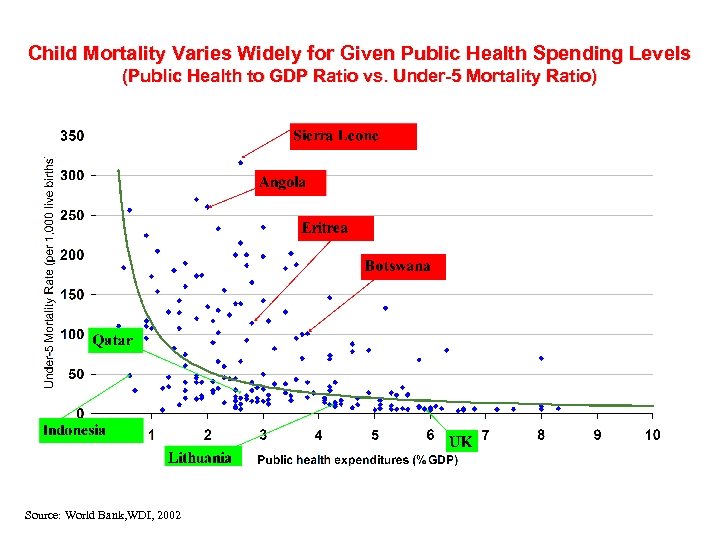

Child Mortality Varies Widely for Given Public Health Spending Levels (Public Health to GDP Ratio vs. Under-5 Mortality Ratio) Source: World Bank, WDI, 2002

Child Mortality Varies Widely for Given Public Health Spending Levels (Public Health to GDP Ratio vs. Under-5 Mortality Ratio) Source: World Bank, WDI, 2002

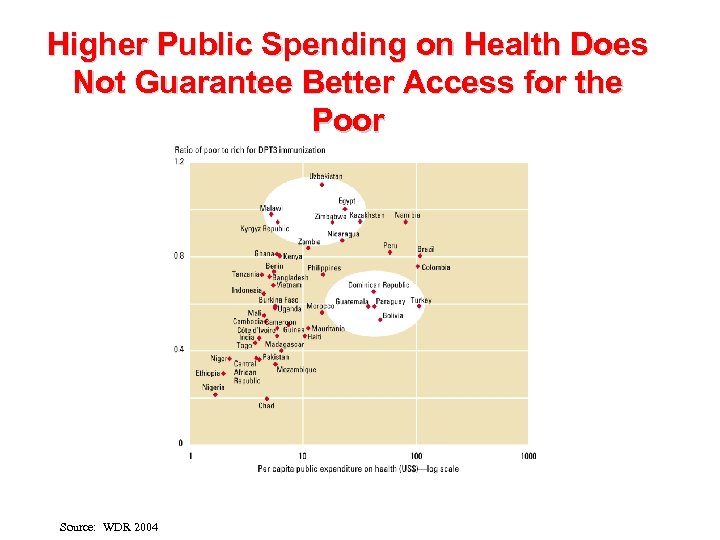

Higher Public Spending on Health Does Not Guarantee Better Access for the Poor Source: WDR 2004

Higher Public Spending on Health Does Not Guarantee Better Access for the Poor Source: WDR 2004

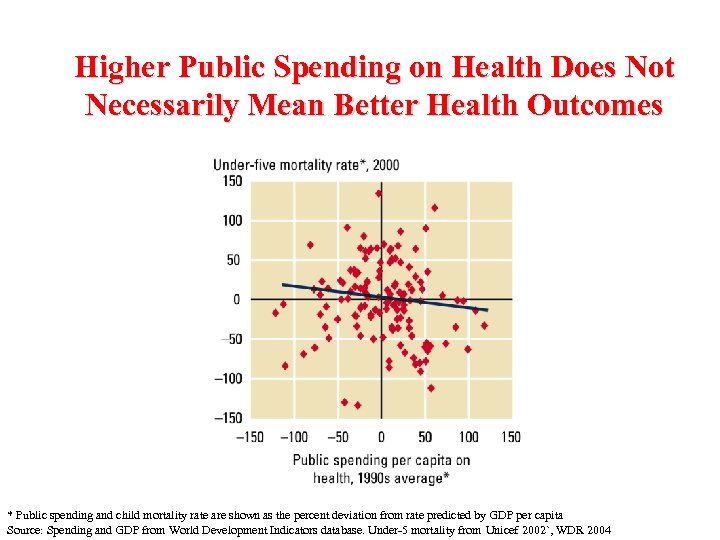

Higher Public Spending on Health Does Not Necessarily Mean Better Health Outcomes * Public spending and child mortality rate are shown as the percent deviation from rate predicted by GDP per capita Source: Spending and GDP from World Development Indicators database. Under-5 mortality from Unicef 2002`, WDR 2004

Higher Public Spending on Health Does Not Necessarily Mean Better Health Outcomes * Public spending and child mortality rate are shown as the percent deviation from rate predicted by GDP per capita Source: Spending and GDP from World Development Indicators database. Under-5 mortality from Unicef 2002`, WDR 2004

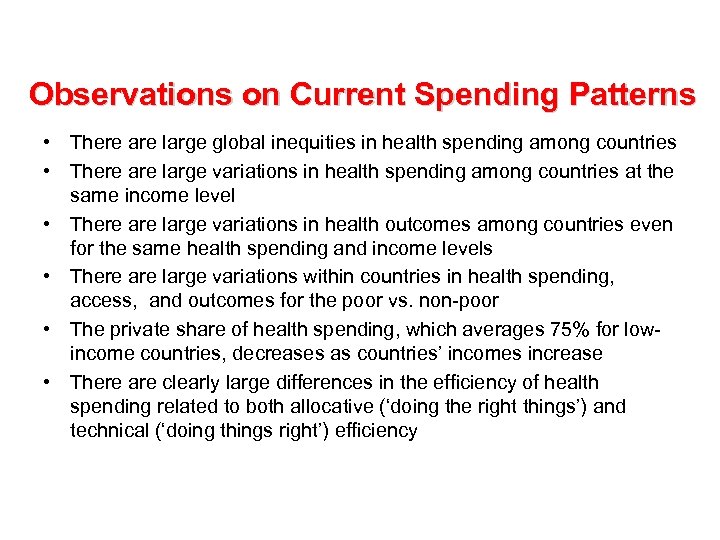

Observations on Current Spending Patterns • There are large global inequities in health spending among countries • There are large variations in health spending among countries at the same income level • There are large variations in health outcomes among countries even for the same health spending and income levels • There are large variations within countries in health spending, access, and outcomes for the poor vs. non-poor • The private share of health spending, which averages 75% for lowincome countries, decreases as countries’ incomes increase • There are clearly large differences in the efficiency of health spending related to both allocative (‘doing the right things’) and technical (‘doing things right’) efficiency

Observations on Current Spending Patterns • There are large global inequities in health spending among countries • There are large variations in health spending among countries at the same income level • There are large variations in health outcomes among countries even for the same health spending and income levels • There are large variations within countries in health spending, access, and outcomes for the poor vs. non-poor • The private share of health spending, which averages 75% for lowincome countries, decreases as countries’ incomes increase • There are clearly large differences in the efficiency of health spending related to both allocative (‘doing the right things’) and technical (‘doing things right’) efficiency

Fundamentals of Health Financing

Fundamentals of Health Financing

Health Financing Functions • • Revenue Collection Pooling of Health Risks Purchasing of Services Provision of Services

Health Financing Functions • • Revenue Collection Pooling of Health Risks Purchasing of Services Provision of Services

Health Financing Objectives • Raising ‘sufficient’, affordable and sustainable revenues in an efficient and equitable manner • Managing these revenues to equitably and efficiently pool health risks among high and low risk individuals, rich and poor, and over individuals’ life cycles • Providing individuals with adequate financial protection against catastrophic financial losses due to illness and injury • Assuring the purchase and provision of health services in the most allocatively and technically efficient manner

Health Financing Objectives • Raising ‘sufficient’, affordable and sustainable revenues in an efficient and equitable manner • Managing these revenues to equitably and efficiently pool health risks among high and low risk individuals, rich and poor, and over individuals’ life cycles • Providing individuals with adequate financial protection against catastrophic financial losses due to illness and injury • Assuring the purchase and provision of health services in the most allocatively and technically efficient manner

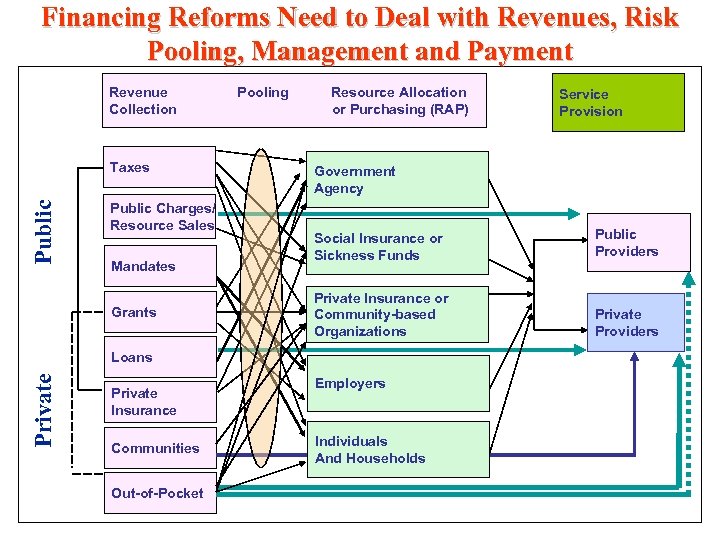

Financing Reforms Need to Deal with Revenues, Risk Pooling, Management and Payment Revenue Collection Public Taxes Public Charges/ Resource Sales Mandates Grants Pooling Resource Allocation or Purchasing (RAP) Government Agency Social Insurance or Sickness Funds Public Providers Private Insurance or Community-based Organizations Private Providers Private Loans Private Insurance Communities Out-of-Pocket Service Provision Employers Individuals And Households

Financing Reforms Need to Deal with Revenues, Risk Pooling, Management and Payment Revenue Collection Public Taxes Public Charges/ Resource Sales Mandates Grants Pooling Resource Allocation or Purchasing (RAP) Government Agency Social Insurance or Sickness Funds Public Providers Private Insurance or Community-based Organizations Private Providers Private Loans Private Insurance Communities Out-of-Pocket Service Provision Employers Individuals And Households

Public Financing Sources ê Taxes ê Sales of natural resources ê User charges ê ê Mandates Grant assistance ê Borrowing ê Efficiency Gains

Public Financing Sources ê Taxes ê Sales of natural resources ê User charges ê ê Mandates Grant assistance ê Borrowing ê Efficiency Gains

Private Financing Sources i Private insurance i Direct out-of-pocket purchase i Grant assistance i Borrowing i Charitable contributions

Private Financing Sources i Private insurance i Direct out-of-pocket purchase i Grant assistance i Borrowing i Charitable contributions

Issues in Taxation è Economic efficiency è Equity è Administrative simplicity è Revenue generation potential è Flexibility è Transparency

Issues in Taxation è Economic efficiency è Equity è Administrative simplicity è Revenue generation potential è Flexibility è Transparency

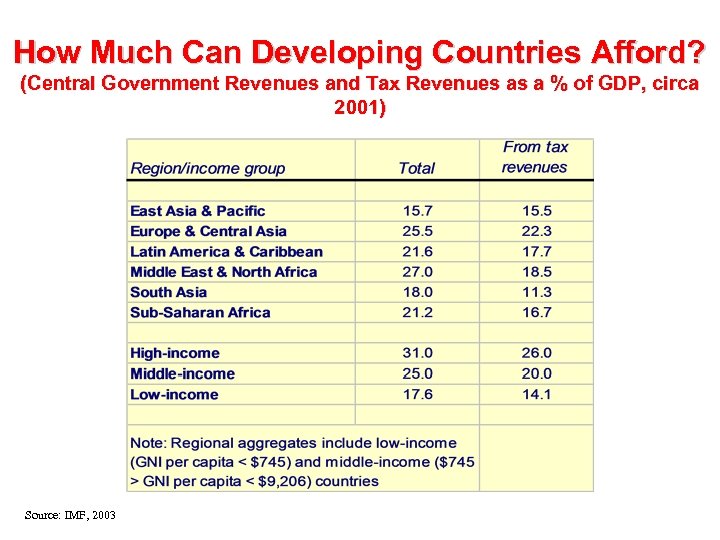

How Much Can Developing Countries Afford? (Central Government Revenues and Tax Revenues as a % of GDP, circa 2001) Source: IMF, 2003

How Much Can Developing Countries Afford? (Central Government Revenues and Tax Revenues as a % of GDP, circa 2001) Source: IMF, 2003

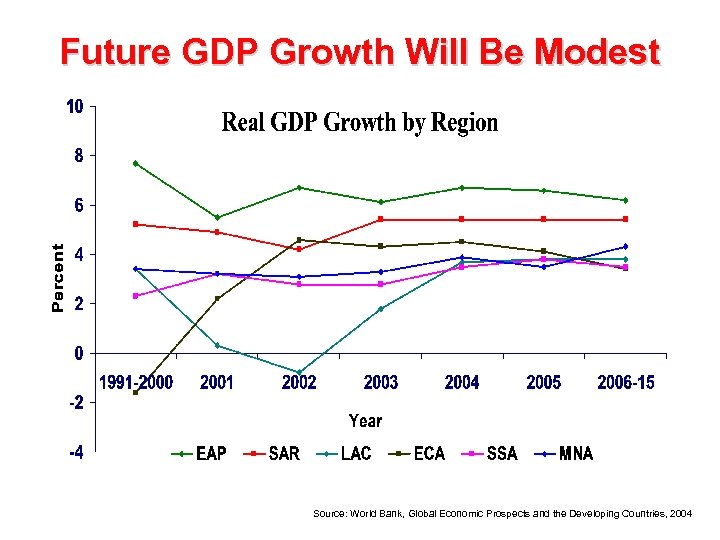

Future GDP Growth Will Be Modest Source: World Bank, Global Economic Prospects and the Developing Countries, 2004

Future GDP Growth Will Be Modest Source: World Bank, Global Economic Prospects and the Developing Countries, 2004

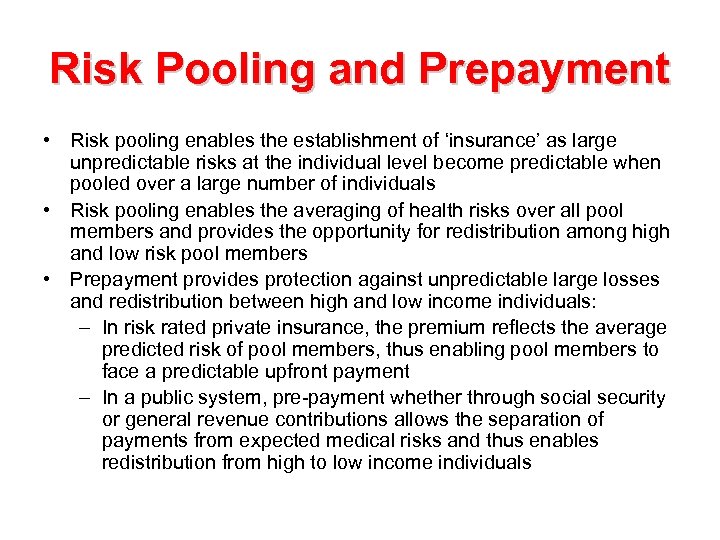

Risk Pooling and Prepayment • Risk pooling enables the establishment of ‘insurance’ as large unpredictable risks at the individual level become predictable when pooled over a large number of individuals • Risk pooling enables the averaging of health risks over all pool members and provides the opportunity for redistribution among high and low risk pool members • Prepayment provides protection against unpredictable large losses and redistribution between high and low income individuals: – In risk rated private insurance, the premium reflects the average predicted risk of pool members, thus enabling pool members to face a predictable upfront payment – In a public system, pre-payment whether through social security or general revenue contributions allows the separation of payments from expected medical risks and thus enables redistribution from high to low income individuals

Risk Pooling and Prepayment • Risk pooling enables the establishment of ‘insurance’ as large unpredictable risks at the individual level become predictable when pooled over a large number of individuals • Risk pooling enables the averaging of health risks over all pool members and provides the opportunity for redistribution among high and low risk pool members • Prepayment provides protection against unpredictable large losses and redistribution between high and low income individuals: – In risk rated private insurance, the premium reflects the average predicted risk of pool members, thus enabling pool members to face a predictable upfront payment – In a public system, pre-payment whether through social security or general revenue contributions allows the separation of payments from expected medical risks and thus enables redistribution from high to low income individuals

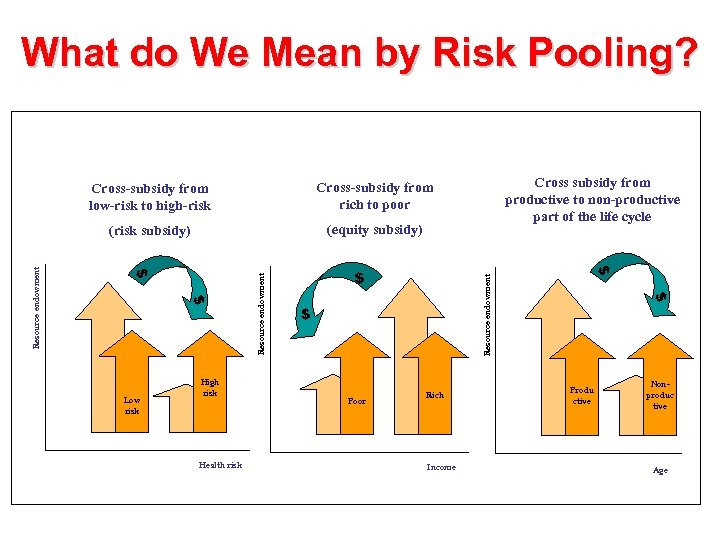

What do We Mean by Risk Pooling? Cross subsidy from productive to non-productive part of the life cycle (equity subsidy) Resource endowment $ Poor Rich Income $ $ Health risk $ $ $ Low risk High risk Resource endowment Cross-subsidy from rich to poor (risk subsidy) Resource endowment Cross-subsidy from low-risk to high-risk Produ ctive Nonproduc tive Age

What do We Mean by Risk Pooling? Cross subsidy from productive to non-productive part of the life cycle (equity subsidy) Resource endowment $ Poor Rich Income $ $ Health risk $ $ $ Low risk High risk Resource endowment Cross-subsidy from rich to poor (risk subsidy) Resource endowment Cross-subsidy from low-risk to high-risk Produ ctive Nonproduc tive Age

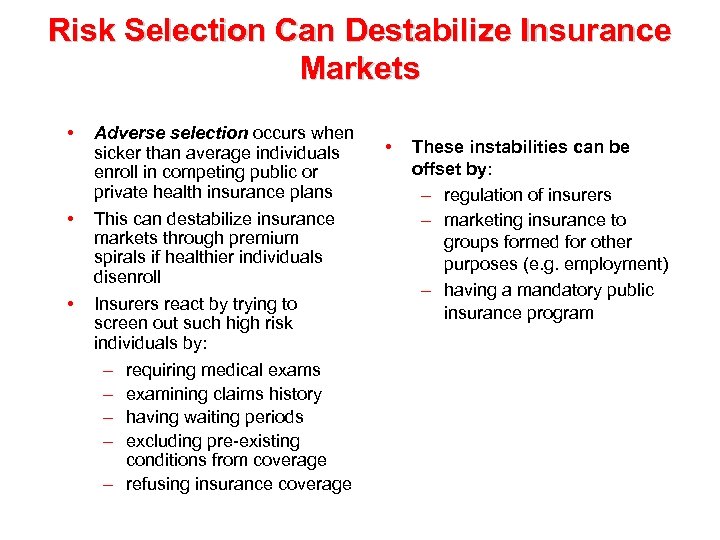

Risk Selection Can Destabilize Insurance Markets • • • Adverse selection occurs when sicker than average individuals enroll in competing public or private health insurance plans This can destabilize insurance markets through premium spirals if healthier individuals disenroll Insurers react by trying to screen out such high risk individuals by: – requiring medical exams – examining claims history – having waiting periods – excluding pre-existing conditions from coverage – refusing insurance coverage • These instabilities can be offset by: – regulation of insurers – marketing insurance to groups formed for other purposes (e. g. employment) – having a mandatory public insurance program

Risk Selection Can Destabilize Insurance Markets • • • Adverse selection occurs when sicker than average individuals enroll in competing public or private health insurance plans This can destabilize insurance markets through premium spirals if healthier individuals disenroll Insurers react by trying to screen out such high risk individuals by: – requiring medical exams – examining claims history – having waiting periods – excluding pre-existing conditions from coverage – refusing insurance coverage • These instabilities can be offset by: – regulation of insurers – marketing insurance to groups formed for other purposes (e. g. employment) – having a mandatory public insurance program

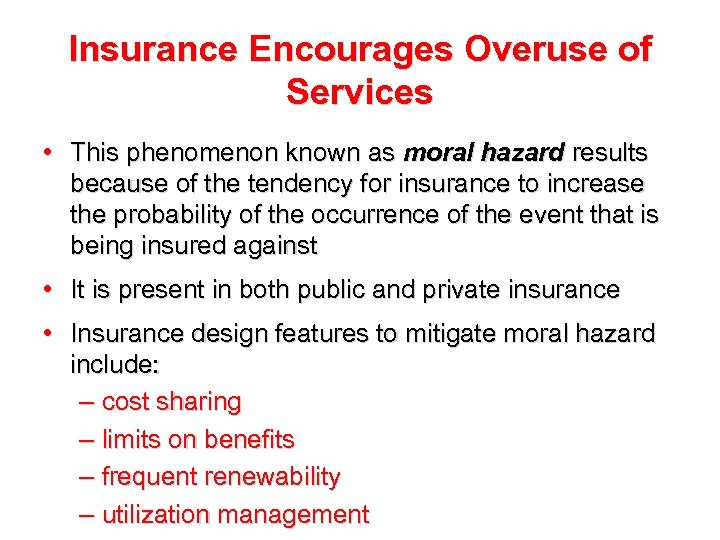

Insurance Encourages Overuse of Services • This phenomenon known as moral hazard results because of the tendency for insurance to increase the probability of the occurrence of the event that is being insured against • It is present in both public and private insurance • Insurance design features to mitigate moral hazard include: – cost sharing – limits on benefits – frequent renewability – utilization management

Insurance Encourages Overuse of Services • This phenomenon known as moral hazard results because of the tendency for insurance to increase the probability of the occurrence of the event that is being insured against • It is present in both public and private insurance • Insurance design features to mitigate moral hazard include: – cost sharing – limits on benefits – frequent renewability – utilization management

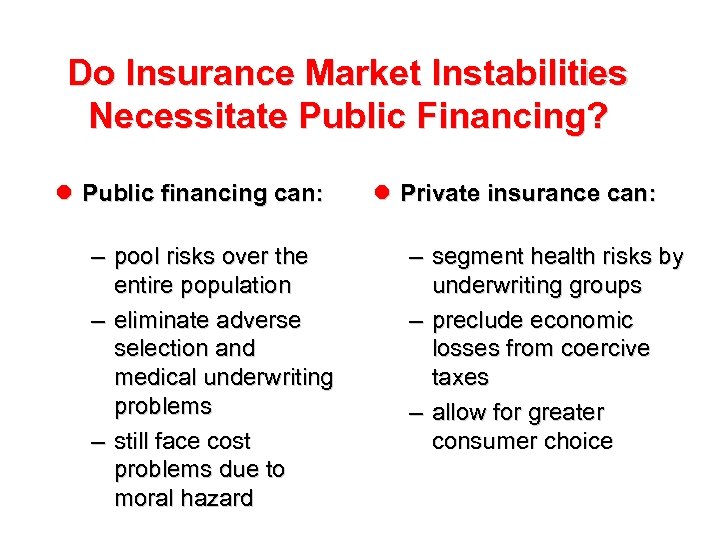

Do Insurance Market Instabilities Necessitate Public Financing? l Public financing can: – pool risks over the entire population – eliminate adverse selection and medical underwriting problems – still face cost problems due to moral hazard l Private insurance can: – segment health risks by underwriting groups – preclude economic losses from coercive taxes – allow for greater consumer choice

Do Insurance Market Instabilities Necessitate Public Financing? l Public financing can: – pool risks over the entire population – eliminate adverse selection and medical underwriting problems – still face cost problems due to moral hazard l Private insurance can: – segment health risks by underwriting groups – preclude economic losses from coercive taxes – allow for greater consumer choice

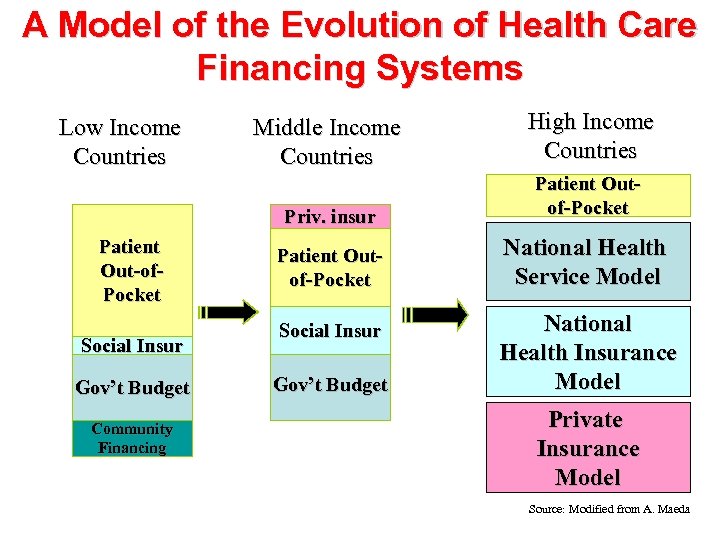

A Model of the Evolution of Health Care Financing Systems Patient Out-of. Pocket Social Insur Gov’t Budget Community Financing Middle Income Countries High Income Countries Priv. insur Low Income Countries Patient Outof-Pocket National Health Service Model Social Insur Gov’t Budget National Health Insurance Model Private Insurance Model Source: Modified from A. Maeda

A Model of the Evolution of Health Care Financing Systems Patient Out-of. Pocket Social Insur Gov’t Budget Community Financing Middle Income Countries High Income Countries Priv. insur Low Income Countries Patient Outof-Pocket National Health Service Model Social Insur Gov’t Budget National Health Insurance Model Private Insurance Model Source: Modified from A. Maeda

Some Experience • There is no one ‘right’ model • Need to tailor model used to individual country circumstances • Need minimal numbers of individuals for effective risk pooling • The larger the number of separate funds, the higher the administrative costs and potential for fragmentation • Unless all funds employ the same provider payment rules, both access for certain groups and efficiency will be compromised • Government can collect the revenues and set the rules, but contract to private fiscal agents/insurers (known as Third Party Administrators – TPAs) to administer the program

Some Experience • There is no one ‘right’ model • Need to tailor model used to individual country circumstances • Need minimal numbers of individuals for effective risk pooling • The larger the number of separate funds, the higher the administrative costs and potential for fragmentation • Unless all funds employ the same provider payment rules, both access for certain groups and efficiency will be compromised • Government can collect the revenues and set the rules, but contract to private fiscal agents/insurers (known as Third Party Administrators – TPAs) to administer the program

The Financing Challenge • System financing must be sustainable --meaning that future economic growth generates sufficient levels of income for decent living standards and external debt solvency • LICs are largely concerned with financing essential services, while MICs are more focused on also assuring financial protection and universal coverage • For low income countries receiving large amounts of external assistance, there are serious questions of absorptive capacity as well as their ability to finance from domestic resources both future recurrent costs directly financed by time-limited grants as well as current and future recurrent costs generated by externally funded investments • Meeting virtually unlimited population demands will be impossible for most countries. Services will be rationed • Achieving MDG/MDG+ goals, improving equity, and targeting the poor will require focused policies • Evidence-based policy-making, effective management, and monitoring and evaluation are necessary conditions for success

The Financing Challenge • System financing must be sustainable --meaning that future economic growth generates sufficient levels of income for decent living standards and external debt solvency • LICs are largely concerned with financing essential services, while MICs are more focused on also assuring financial protection and universal coverage • For low income countries receiving large amounts of external assistance, there are serious questions of absorptive capacity as well as their ability to finance from domestic resources both future recurrent costs directly financed by time-limited grants as well as current and future recurrent costs generated by externally funded investments • Meeting virtually unlimited population demands will be impossible for most countries. Services will be rationed • Achieving MDG/MDG+ goals, improving equity, and targeting the poor will require focused policies • Evidence-based policy-making, effective management, and monitoring and evaluation are necessary conditions for success

Provider Payment

Provider Payment

Fundamental Issues • • • What care will be produced? How will care be produced? How much care will be produced? What level of ‘quality’ will be produced? To whom will care be offered? What kinds of care and how much will consumers ‘demand’/access? • By what method, how much, and by whom will providers be paid and/or consumers reimbursed? Source: Modified from Rena Eichler, WB, 2003

Fundamental Issues • • • What care will be produced? How will care be produced? How much care will be produced? What level of ‘quality’ will be produced? To whom will care be offered? What kinds of care and how much will consumers ‘demand’/access? • By what method, how much, and by whom will providers be paid and/or consumers reimbursed? Source: Modified from Rena Eichler, WB, 2003

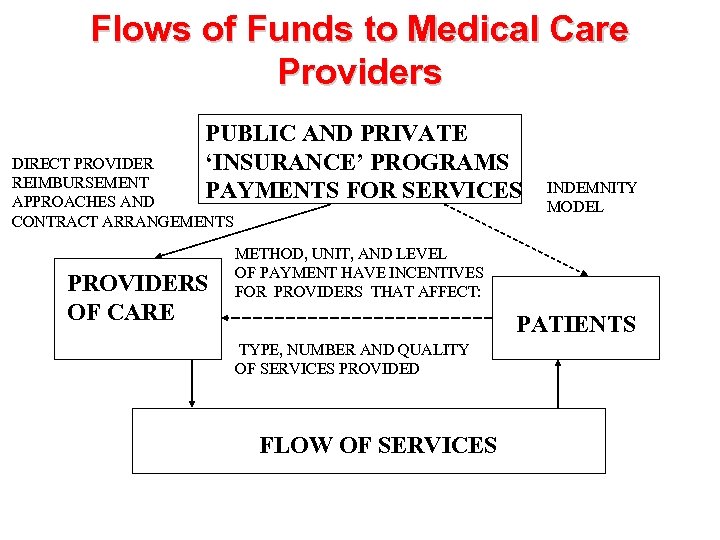

Flows of Funds to Medical Care Providers PUBLIC AND PRIVATE ‘INSURANCE’ PROGRAMS PAYMENTS FOR SERVICES DIRECT PROVIDER REIMBURSEMENT APPROACHES AND CONTRACT ARRANGEMENTS PROVIDERS OF CARE INDEMNITY MODEL METHOD, UNIT, AND LEVEL OF PAYMENT HAVE INCENTIVES FOR PROVIDERS THAT AFFECT: PATIENTS TYPE, NUMBER AND QUALITY OF SERVICES PROVIDED FLOW OF SERVICES

Flows of Funds to Medical Care Providers PUBLIC AND PRIVATE ‘INSURANCE’ PROGRAMS PAYMENTS FOR SERVICES DIRECT PROVIDER REIMBURSEMENT APPROACHES AND CONTRACT ARRANGEMENTS PROVIDERS OF CARE INDEMNITY MODEL METHOD, UNIT, AND LEVEL OF PAYMENT HAVE INCENTIVES FOR PROVIDERS THAT AFFECT: PATIENTS TYPE, NUMBER AND QUALITY OF SERVICES PROVIDED FLOW OF SERVICES

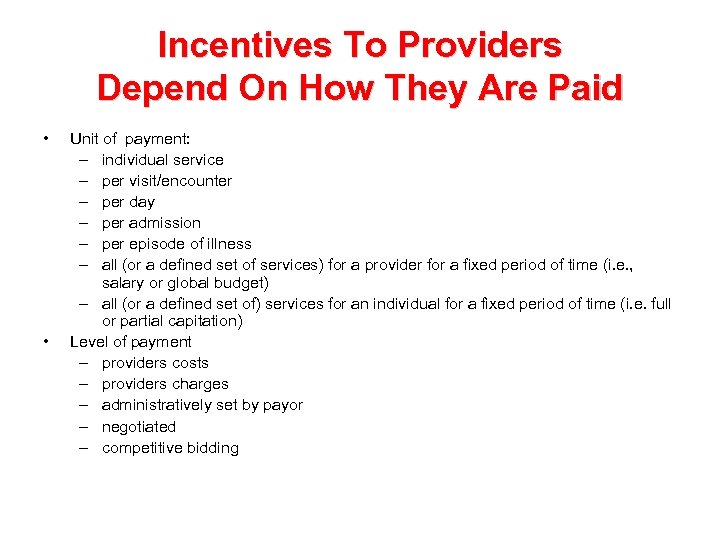

Incentives To Providers Depend On How They Are Paid • • Unit of payment: – individual service – per visit/encounter – per day – per admission – per episode of illness – all (or a defined set of services) for a provider for a fixed period of time (i. e. , salary or global budget) – all (or a defined set of) services for an individual for a fixed period of time (i. e. full or partial capitation) Level of payment – providers costs – providers charges – administratively set by payor – negotiated – competitive bidding

Incentives To Providers Depend On How They Are Paid • • Unit of payment: – individual service – per visit/encounter – per day – per admission – per episode of illness – all (or a defined set of services) for a provider for a fixed period of time (i. e. , salary or global budget) – all (or a defined set of) services for an individual for a fixed period of time (i. e. full or partial capitation) Level of payment – providers costs – providers charges – administratively set by payor – negotiated – competitive bidding

Need To Monitor • Costs • Quality • Access • Impacts across different provider types • Impacts across all public and private payors including those paying out of pocket

Need To Monitor • Costs • Quality • Access • Impacts across different provider types • Impacts across all public and private payors including those paying out of pocket

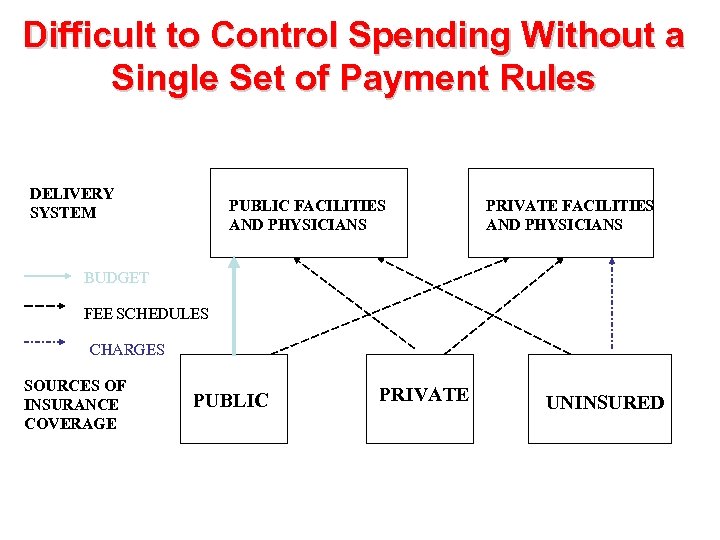

Difficult to Control Spending Without a Single Set of Payment Rules DELIVERY SYSTEM PUBLIC FACILITIES AND PHYSICIANS PRIVATE FACILITIES AND PHYSICIANS BUDGET FEE SCHEDULES CHARGES SOURCES OF INSURANCE COVERAGE PUBLIC PRIVATE UNINSURED

Difficult to Control Spending Without a Single Set of Payment Rules DELIVERY SYSTEM PUBLIC FACILITIES AND PHYSICIANS PRIVATE FACILITIES AND PHYSICIANS BUDGET FEE SCHEDULES CHARGES SOURCES OF INSURANCE COVERAGE PUBLIC PRIVATE UNINSURED

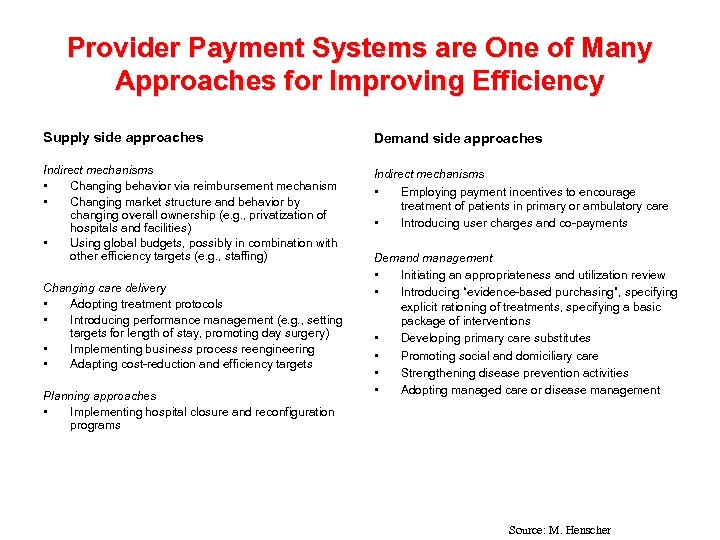

Provider Payment Systems are One of Many Approaches for Improving Efficiency Supply side approaches Demand side approaches Indirect mechanisms • Changing behavior via reimbursement mechanism • Changing market structure and behavior by changing overall ownership (e. g. , privatization of hospitals and facilities) • Using global budgets, possibly in combination with other efficiency targets (e. g. , staffing) Indirect mechanisms • Employing payment incentives to encourage treatment of patients in primary or ambulatory care • Introducing user charges and co-payments Changing care delivery • Adopting treatment protocols • Introducing performance management (e. g. , setting targets for length of stay, promoting day surgery) • Implementing business process reengineering • Adapting cost-reduction and efficiency targets Planning approaches • Implementing hospital closure and reconfiguration programs Demand management • Initiating an appropriateness and utilization review • Introducing “evidence-based purchasing”, specifying explicit rationing of treatments, specifying a basic package of interventions • Developing primary care substitutes • Promoting social and domiciliary care • Strengthening disease prevention activities • Adopting managed care or disease management Source: M. Henscher

Provider Payment Systems are One of Many Approaches for Improving Efficiency Supply side approaches Demand side approaches Indirect mechanisms • Changing behavior via reimbursement mechanism • Changing market structure and behavior by changing overall ownership (e. g. , privatization of hospitals and facilities) • Using global budgets, possibly in combination with other efficiency targets (e. g. , staffing) Indirect mechanisms • Employing payment incentives to encourage treatment of patients in primary or ambulatory care • Introducing user charges and co-payments Changing care delivery • Adopting treatment protocols • Introducing performance management (e. g. , setting targets for length of stay, promoting day surgery) • Implementing business process reengineering • Adapting cost-reduction and efficiency targets Planning approaches • Implementing hospital closure and reconfiguration programs Demand management • Initiating an appropriateness and utilization review • Introducing “evidence-based purchasing”, specifying explicit rationing of treatments, specifying a basic package of interventions • Developing primary care substitutes • Promoting social and domiciliary care • Strengthening disease prevention activities • Adopting managed care or disease management Source: M. Henscher

Health Reform Issues

Health Reform Issues

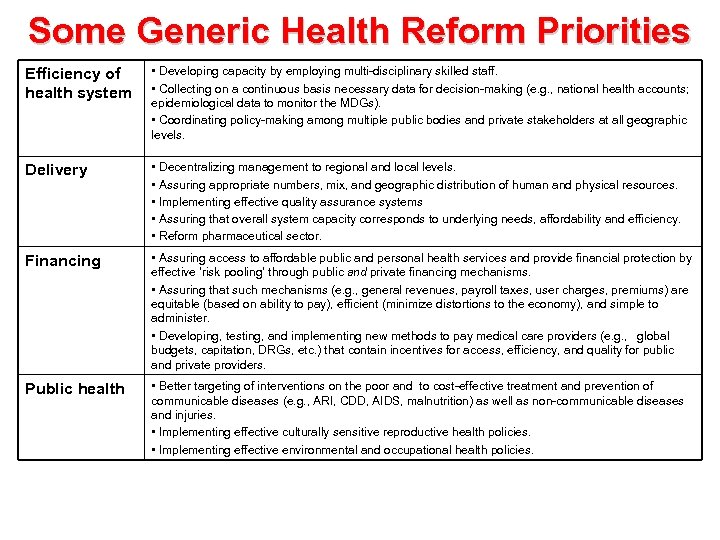

Some Generic Health Reform Priorities Efficiency of health system • Developing capacity by employing multi-disciplinary skilled staff. • Collecting on a continuous basis necessary data for decision-making (e. g. , national health accounts; epidemiological data to monitor the MDGs). • Coordinating policy-making among multiple public bodies and private stakeholders at all geographic levels. Delivery • Decentralizing management to regional and local levels. • Assuring appropriate numbers, mix, and geographic distribution of human and physical resources. • Implementing effective quality assurance systems • Assuring that overall system capacity corresponds to underlying needs, affordability and efficiency. • Reform pharmaceutical sector. Financing • Assuring access to affordable public and personal health services and provide financial protection by effective ‘risk pooling’ through public and private financing mechanisms. • Assuring that such mechanisms (e. g. , general revenues, payroll taxes, user charges, premiums) are equitable (based on ability to pay), efficient (minimize distortions to the economy), and simple to administer. • Developing, testing, and implementing new methods to pay medical care providers (e. g. , global budgets, capitation, DRGs, etc. ) that contain incentives for access, efficiency, and quality for public and private providers. Public health • Better targeting of interventions on the poor and to cost-effective treatment and prevention of communicable diseases (e. g. , ARI, CDD, AIDS, malnutrition) as well as non-communicable diseases and injuries. • Implementing effective culturally sensitive reproductive health policies. • Implementing effective environmental and occupational health policies.

Some Generic Health Reform Priorities Efficiency of health system • Developing capacity by employing multi-disciplinary skilled staff. • Collecting on a continuous basis necessary data for decision-making (e. g. , national health accounts; epidemiological data to monitor the MDGs). • Coordinating policy-making among multiple public bodies and private stakeholders at all geographic levels. Delivery • Decentralizing management to regional and local levels. • Assuring appropriate numbers, mix, and geographic distribution of human and physical resources. • Implementing effective quality assurance systems • Assuring that overall system capacity corresponds to underlying needs, affordability and efficiency. • Reform pharmaceutical sector. Financing • Assuring access to affordable public and personal health services and provide financial protection by effective ‘risk pooling’ through public and private financing mechanisms. • Assuring that such mechanisms (e. g. , general revenues, payroll taxes, user charges, premiums) are equitable (based on ability to pay), efficient (minimize distortions to the economy), and simple to administer. • Developing, testing, and implementing new methods to pay medical care providers (e. g. , global budgets, capitation, DRGs, etc. ) that contain incentives for access, efficiency, and quality for public and private providers. Public health • Better targeting of interventions on the poor and to cost-effective treatment and prevention of communicable diseases (e. g. , ARI, CDD, AIDS, malnutrition) as well as non-communicable diseases and injuries. • Implementing effective culturally sensitive reproductive health policies. • Implementing effective environmental and occupational health policies.

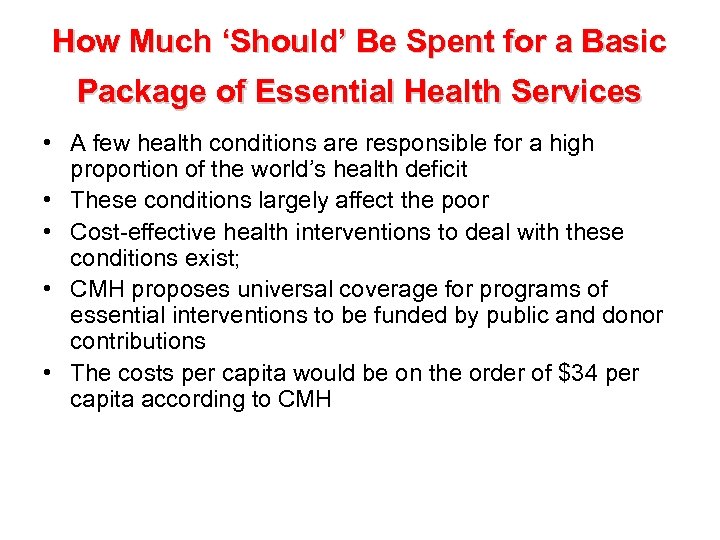

How Much ‘Should’ Be Spent for a Basic Package of Essential Health Services • A few health conditions are responsible for a high proportion of the world’s health deficit • These conditions largely affect the poor • Cost-effective health interventions to deal with these conditions exist; • CMH proposes universal coverage for programs of essential interventions to be funded by public and donor contributions • The costs per capita would be on the order of $34 per capita according to CMH

How Much ‘Should’ Be Spent for a Basic Package of Essential Health Services • A few health conditions are responsible for a high proportion of the world’s health deficit • These conditions largely affect the poor • Cost-effective health interventions to deal with these conditions exist; • CMH proposes universal coverage for programs of essential interventions to be funded by public and donor contributions • The costs per capita would be on the order of $34 per capita according to CMH

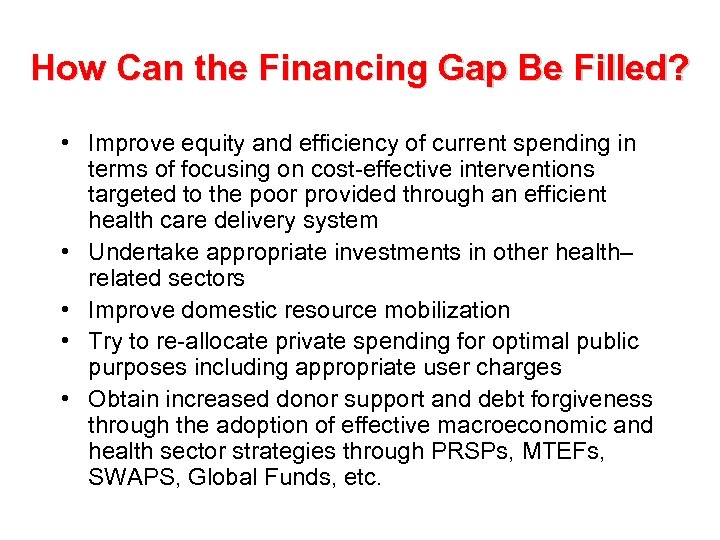

How Can the Financing Gap Be Filled? • Improve equity and efficiency of current spending in terms of focusing on cost-effective interventions targeted to the poor provided through an efficient health care delivery system • Undertake appropriate investments in other health– related sectors • Improve domestic resource mobilization • Try to re-allocate private spending for optimal public purposes including appropriate user charges • Obtain increased donor support and debt forgiveness through the adoption of effective macroeconomic and health sector strategies through PRSPs, MTEFs, SWAPS, Global Funds, etc.

How Can the Financing Gap Be Filled? • Improve equity and efficiency of current spending in terms of focusing on cost-effective interventions targeted to the poor provided through an efficient health care delivery system • Undertake appropriate investments in other health– related sectors • Improve domestic resource mobilization • Try to re-allocate private spending for optimal public purposes including appropriate user charges • Obtain increased donor support and debt forgiveness through the adoption of effective macroeconomic and health sector strategies through PRSPs, MTEFs, SWAPS, Global Funds, etc.

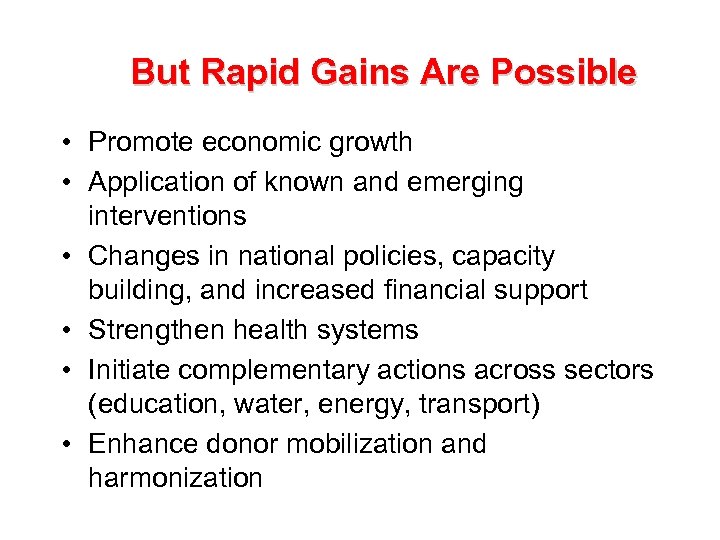

But Rapid Gains Are Possible • Promote economic growth • Application of known and emerging interventions • Changes in national policies, capacity building, and increased financial support • Strengthen health systems • Initiate complementary actions across sectors (education, water, energy, transport) • Enhance donor mobilization and harmonization

But Rapid Gains Are Possible • Promote economic growth • Application of known and emerging interventions • Changes in national policies, capacity building, and increased financial support • Strengthen health systems • Initiate complementary actions across sectors (education, water, energy, transport) • Enhance donor mobilization and harmonization

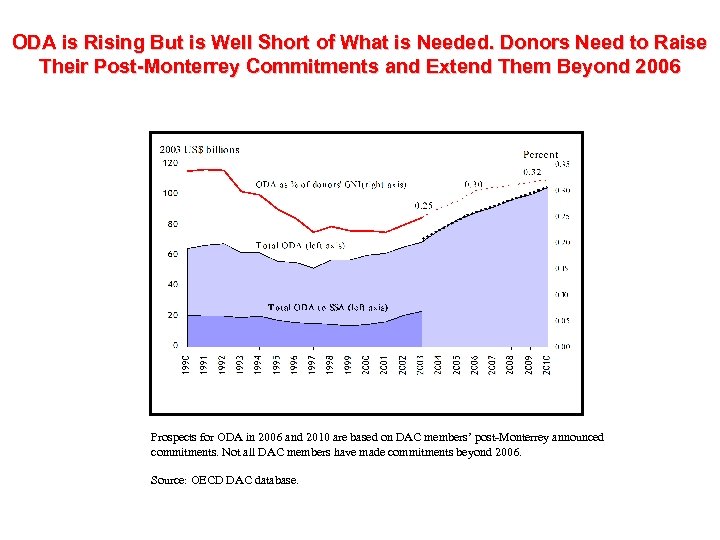

ODA is Rising But is Well Short of What is Needed. Donors Need to Raise Their Post-Monterrey Commitments and Extend Them Beyond 2006 Prospects for ODA in 2006 and 2010 are based on DAC members’ post-Monterrey announced commitments. Not all DAC members have made commitments beyond 2006. Source: OECD DAC database.

ODA is Rising But is Well Short of What is Needed. Donors Need to Raise Their Post-Monterrey Commitments and Extend Them Beyond 2006 Prospects for ODA in 2006 and 2010 are based on DAC members’ post-Monterrey announced commitments. Not all DAC members have made commitments beyond 2006. Source: OECD DAC database.

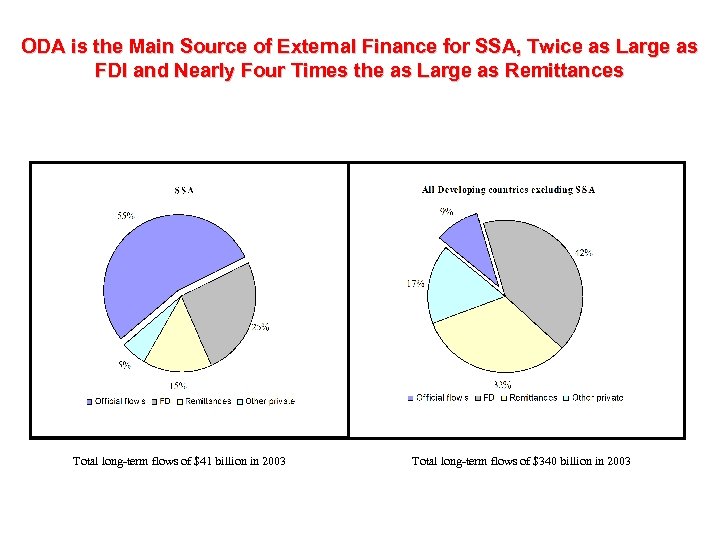

ODA is the Main Source of External Finance for SSA, Twice as Large as FDI and Nearly Four Times the as Large as Remittances Total long-term flows of $41 billion in 2003 Total long-term flows of $340 billion in 2003

ODA is the Main Source of External Finance for SSA, Twice as Large as FDI and Nearly Four Times the as Large as Remittances Total long-term flows of $41 billion in 2003 Total long-term flows of $340 billion in 2003

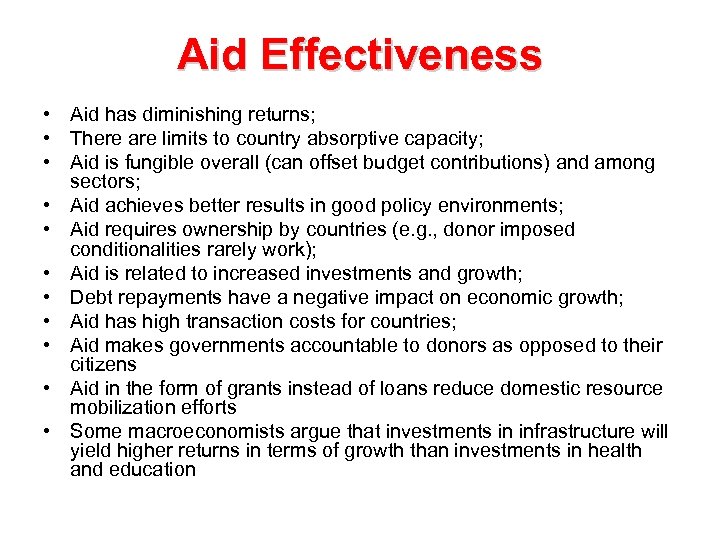

Aid Effectiveness • Aid has diminishing returns; • There are limits to country absorptive capacity; • Aid is fungible overall (can offset budget contributions) and among sectors; • Aid achieves better results in good policy environments; • Aid requires ownership by countries (e. g. , donor imposed conditionalities rarely work); • Aid is related to increased investments and growth; • Debt repayments have a negative impact on economic growth; • Aid has high transaction costs for countries; • Aid makes governments accountable to donors as opposed to their citizens • Aid in the form of grants instead of loans reduce domestic resource mobilization efforts • Some macroeconomists argue that investments in infrastructure will yield higher returns in terms of growth than investments in health and education

Aid Effectiveness • Aid has diminishing returns; • There are limits to country absorptive capacity; • Aid is fungible overall (can offset budget contributions) and among sectors; • Aid achieves better results in good policy environments; • Aid requires ownership by countries (e. g. , donor imposed conditionalities rarely work); • Aid is related to increased investments and growth; • Debt repayments have a negative impact on economic growth; • Aid has high transaction costs for countries; • Aid makes governments accountable to donors as opposed to their citizens • Aid in the form of grants instead of loans reduce domestic resource mobilization efforts • Some macroeconomists argue that investments in infrastructure will yield higher returns in terms of growth than investments in health and education

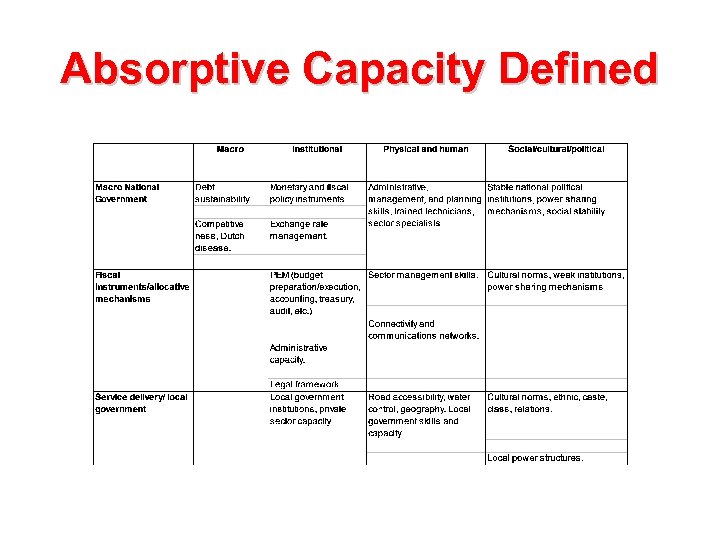

Absorptive Capacity Defined

Absorptive Capacity Defined

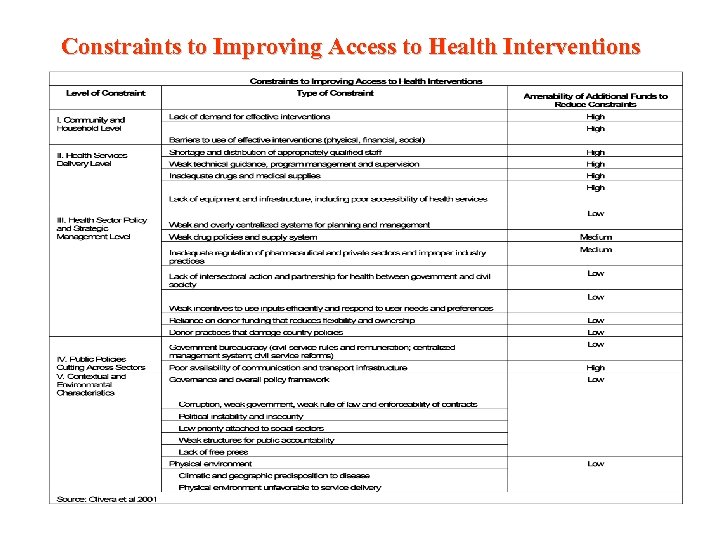

Constraints to Improving Access to Health Interventions

Constraints to Improving Access to Health Interventions

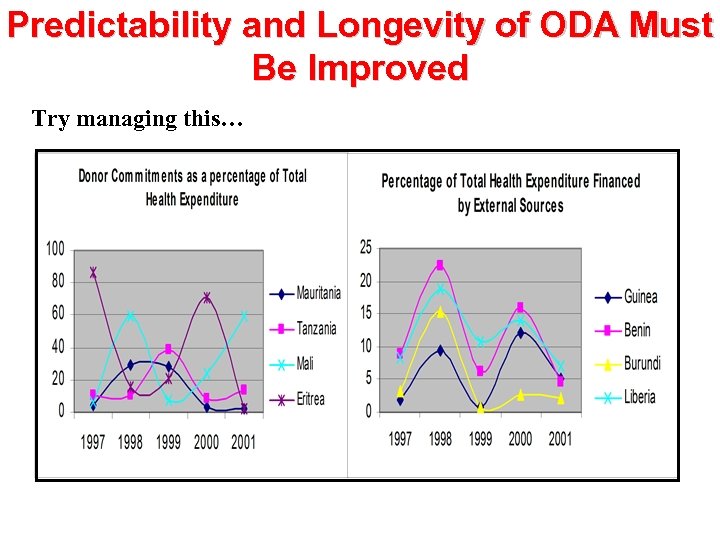

Predictability and Longevity of ODA Must Be Improved Try managing this…

Predictability and Longevity of ODA Must Be Improved Try managing this…

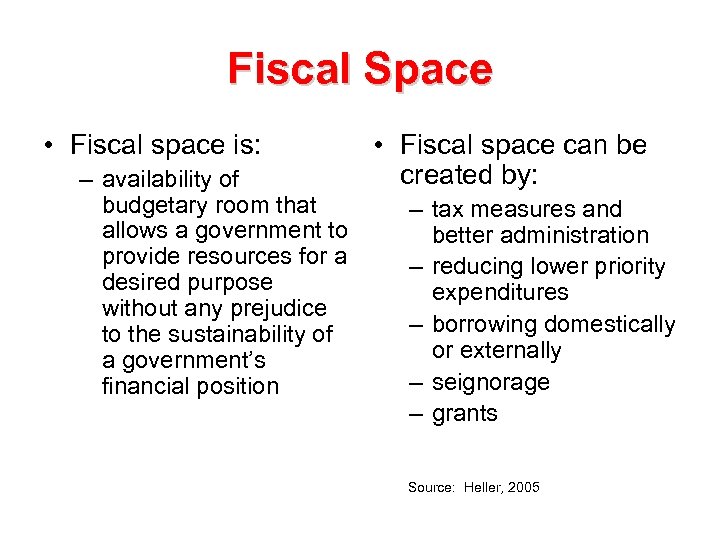

Fiscal Space • Fiscal space is: – availability of budgetary room that allows a government to provide resources for a desired purpose without any prejudice to the sustainability of a government’s financial position • Fiscal space can be created by: – tax measures and better administration – reducing lower priority expenditures – borrowing domestically or externally – seignorage – grants Source: Heller, 2005

Fiscal Space • Fiscal space is: – availability of budgetary room that allows a government to provide resources for a desired purpose without any prejudice to the sustainability of a government’s financial position • Fiscal space can be created by: – tax measures and better administration – reducing lower priority expenditures – borrowing domestically or externally – seignorage – grants Source: Heller, 2005

Fiscal Sustainability Definitions • Generally defined in terms of self-sufficiency -- over a specific time period, the responsible managing entity will generate sufficient resources to fund the full costs of a particular program, sector, or economy including the incremental service costs associated with new investments and the servicing and repayment of external debt. • The capacity of the health system to replace withdrawn donor funds with funds from other, usually domestic, sources • The sustainability of an individual program is defined as “capacity of the grantee to mobilize the resources to fund the recurrent costs of a project once the investment phase has ended” • A softer definition is that the managing entity commits a stable and fixed share of program costs

Fiscal Sustainability Definitions • Generally defined in terms of self-sufficiency -- over a specific time period, the responsible managing entity will generate sufficient resources to fund the full costs of a particular program, sector, or economy including the incremental service costs associated with new investments and the servicing and repayment of external debt. • The capacity of the health system to replace withdrawn donor funds with funds from other, usually domestic, sources • The sustainability of an individual program is defined as “capacity of the grantee to mobilize the resources to fund the recurrent costs of a project once the investment phase has ended” • A softer definition is that the managing entity commits a stable and fixed share of program costs

What Will Donors Have to Do? • Harmonize procedures (procurement, financial mgt, monitoring & reporting) in order to improve impacts and reduce donor and country transactions costs • Provide increased and predictable long term financing • Finance recurrent costs • Offer consistent policy advice • Submit to common assessment of their own performance

What Will Donors Have to Do? • Harmonize procedures (procurement, financial mgt, monitoring & reporting) in order to improve impacts and reduce donor and country transactions costs • Provide increased and predictable long term financing • Finance recurrent costs • Offer consistent policy advice • Submit to common assessment of their own performance

What Does This Mean for Countries? • • Develop credible strategies and plans to foster economic growth, deal with implementation bottlenecks, and reach MDGs as part of PRSPs, SWAPs, MTEFs, and public expenditure programs Improve governance including giving voice to communities, consumers and openness to NGOs and private sector Enhance absorptive capacity through decentralization, efficient targeting mechanisms, and institutional reforms including having a clear fiduciary architecture and open reporting of results Improve equity and efficiency of resource mobilization and commit resources Middle income countries need to make the commitment to develop and implement effective health reform strategies relying on evidence-based policy, best international practice, and MDG+ goals and indicators Develop financing, management, and regulatory mechanisms for equitable and effective pooling of insurable health risks as a necessary concomitant to MDG and CMH intervention choices. Integrating vertical programs into a well functioning health system to maximize health-specific and cross-sectoral outcomes and reduce transactions costs Monitor and evaluate results

What Does This Mean for Countries? • • Develop credible strategies and plans to foster economic growth, deal with implementation bottlenecks, and reach MDGs as part of PRSPs, SWAPs, MTEFs, and public expenditure programs Improve governance including giving voice to communities, consumers and openness to NGOs and private sector Enhance absorptive capacity through decentralization, efficient targeting mechanisms, and institutional reforms including having a clear fiduciary architecture and open reporting of results Improve equity and efficiency of resource mobilization and commit resources Middle income countries need to make the commitment to develop and implement effective health reform strategies relying on evidence-based policy, best international practice, and MDG+ goals and indicators Develop financing, management, and regulatory mechanisms for equitable and effective pooling of insurable health risks as a necessary concomitant to MDG and CMH intervention choices. Integrating vertical programs into a well functioning health system to maximize health-specific and cross-sectoral outcomes and reduce transactions costs Monitor and evaluate results

A Shared Global Approach • Build on existing funding modalities • Use and further improve existing plans and mechanisms at the country level • Address inequities within countries • Scale up cost-effective interventions • Tackle critical implementation constraints • Apply a multi-sectoral approach • Focus on results • Country orientation, but global action is also needed

A Shared Global Approach • Build on existing funding modalities • Use and further improve existing plans and mechanisms at the country level • Address inequities within countries • Scale up cost-effective interventions • Tackle critical implementation constraints • Apply a multi-sectoral approach • Focus on results • Country orientation, but global action is also needed