ab28d5ec737ad76f5999314292a7efdc.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 25

Guillain-Barré Syndrome Treatment related to Motor Speech Disorders Heather Hetler CD 502 Motor Speech Disorders Spring, 2011

Speech Therapy Flaccid Dysarthria may occur, due to the demylenation of the cranial nerves related to speech. Fatigue is a major factor in Guillain-Barré Syndrome rehabilitation. • Manage fatigue with energy conservation strategies in all motor activities. • Be aware of fatigue level during treatment sessions. Most will fully recover from GBS though the most severely impacted may require several months to years of rehabilitation. 2

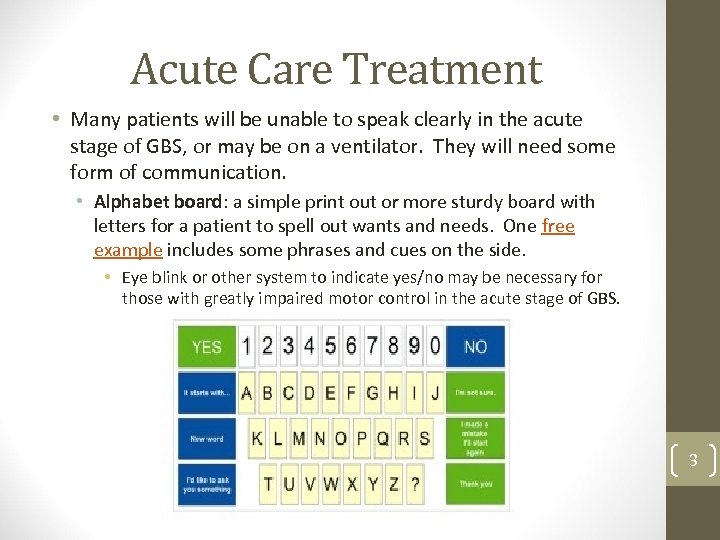

Acute Care Treatment • Many patients will be unable to speak clearly in the acute stage of GBS, or may be on a ventilator. They will need some form of communication. • Alphabet board: a simple print out or more sturdy board with letters for a patient to spell out wants and needs. One free example includes some phrases and cues on the side. • Eye blink or other system to indicate yes/no may be necessary for those with greatly impaired motor control in the acute stage of GBS. 3

Acute Care Treatment • Basic apps may be useful in acute care, such as the Yes/No App from Smarty. Ears. • The i. Pod touch or i. Phone is easy to press, allowing for easy use by patients with limited control. 4

Acute Care Treatment • Communication cards, such as those available from GBS/CIDP Foundation International, are simple index cards pre-printed with frequently needed communication needs. • These can be easily made and personalized for a particular patient, and, as pictured, can also include a small alphabet board. 5

Acute Care Treatment • Those who require a tracheostomy may also be able to learn methods for oral speech. • Cuff deflated, if possible, may allow for speech • A valve that attaches to the tracheostomy tube may help allow air to enter via the tube but leave by way of the mouth and nose, and allow for speech. Passy-Muir Tracheostomy and Ventilator Speaking Valve 6

Rehabilitation • Many patients will use simple communication systems for a limited time, as recovery will be complete. • Those more severely impacted will require more intense rehabilitation therapy as they recover. • Flaccid dysarthria most often leads to hypernasality, imprecise consonants, breathiness, and monopitch, though the specific characteristics will vary depending on the specific cranial nerves impacted. • Those who required a tracheostomy may need therapy after the tracheostomy tube is removed. • Therapy may address overall communication (AAC devices); respiration; phonation; resonance; articulation; and/or rate and prosody 7

Respiration • Goal is to maximize respiratory function • Postural adjustments: may be very effective, especially during recovery when a patient’s overall muscle function is still weak. • Generally involves asking patient to sit up straigh. • Can lean against lap tray in a wheelchair • Some studies indicate a supine or reclined position can aid effectiveness of therapy. • Sustained phonation: exhale and phonate at a steady rate, with a goal of at least 5 seconds, moving toward more speech-like tasks, such as repeating syllables. • Speak on exhalation: practice beginning phonation immediately upon exhalation. 8

Phonation • Effortful closure techniques • Pushing and pulling during phonation may aid in vocal fold adduction (push up on arms of chair, pull against a table) • Phonation can be prolongation of vowels, syllables, or words. • Hard glottal attack • Hold a deep breath, then bear down while phonating. • Not a long-term strategy due to negative effects on voice if done consistently. • Head turn • May be helpful if unilateral weakess or paralysis • Turn head toward affected side during phonation to bring weakened fold closer to opposite side. 9

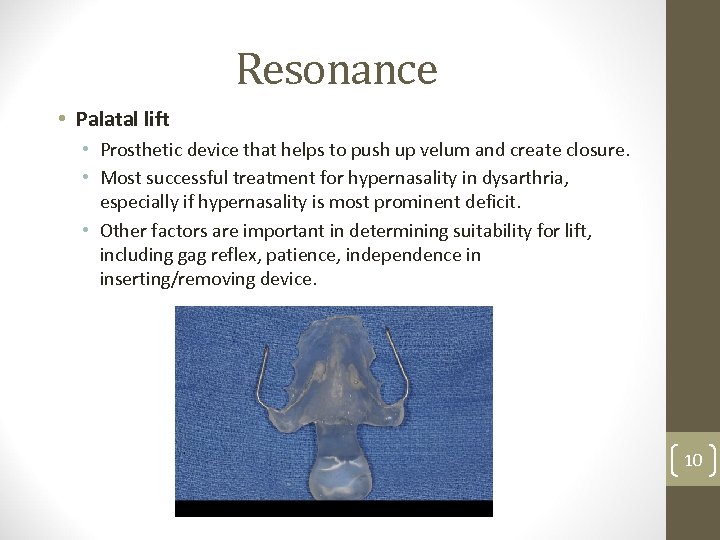

Resonance • Palatal lift • Prosthetic device that helps to push up velum and create closure. • Most successful treatment for hypernasality in dysarthria, especially if hypernasality is most prominent deficit. • Other factors are important in determining suitability for lift, including gag reflex, patience, independence in inserting/removing device. 10

Resonance • Speech modification • Minimize perception of hypernasality by increasing volume, reducing rate of speech, and an open-position of mouth during speech. • Might aid in the short-term for those whose recovery is not yet complete. • Surgery • Unlikely to be utilized in Guillain-Barré Syndrome, since most will recover. • May be considered for those with most severe GBS with continued long-term problems, if the use of a palatal lift is not helping or not a good option. 11

Articulation • Treatment method may vary depending on the affected cranial nerve. • Damage to Facial Cranial Nerve • Work on lip closure • Some advocate for non-speech oral motor exercises to strengthen lips, but more recent studies indicate there is no benefit to NSOMEs. • May help for those with severe impairment, where strengthening exercises can add enough muscular strength to improve intelligibility, or for those with mild impairment where a small change may be all that is needed. 12

Articulation • Damage to Hypoglossal Cranial Nerve • Little evidence for efficacy in strengthening exercises. • Traditional Articulation Treatment • Identify sounds in error and address production in drills • Work on phonetic placement of particular sounds by learning correct placement, using mirrors and tactile cues if necessary. • Over-articulation of consonants • Exaggerate production, leading to increased intelligibility even with weakness. • Focus on medial and final consonants 13

Articulation • May teach compensatory placement for difficult consonants. • Patient can be instructed to modify placement to one that leads to a more intelligible approximation. • Use of alphabet board to help with connected speech. • Patient can use alphabet board to indicate first letter during speech, or to help spell difficult words. 14

Rate and Prosody Pacing strategies • Slow rate of speech • Slowing rate of speech has been shown to be very effective in addressing many intelligibility problems in dysarthria. • Chunk utterances • Divide utterances by normal pauses • Contrastive stress drills • The patient varies word stress in an phrase or utterance in order to convey intended meaning. • Stretching • Prolonging vowels 15

Augmentative and Alternative Communication • Adults with an acquired communication loss are often good candidates for AAC. • SLP is involved in assessment and implementation of the use of an AAC device or method. • In severe cases of GBS, a patient may need to use AAC, for either a short or long-term solution. 16

AAC Devices and Methods • Those previously described in Acute Care may be used on for a longer time period: • Alphabet board • Communication cards • Basic yes/no apps • However, if a patient is severely impacted by GBS, other options may be considered for rehabilitation. • Head-mount laser • Full communication system • i. Pad communication system 17

AAC devices and methods • Safe-laser access system • Utilizes a head-mount laser controlled by slight head movement for a severely impacted patient, including those with “locked-in syndrome” in severe cases of GBS. 18

AAC devices and methods • Communication System • For those with severe impairments who may be using AAC for a longer time period, a text-to-speech device may be useful. • Text-to-Speech device useful for those with enough motor control 19

AAC devices and methods • The i. Pad and i. Phone provide a socially acceptable device with a variety of different ways to implement AAC. • Research is still needed in this new device to determine best practice, but some already-known principles can be applied generally to the i. Pad/i. Phone • Can use for text-to-speech, alphabet board, mixed symbol and word, and all symbol. • Some level of motor control is needed: the letters or pictures are easy to select, but for some users can be difficult to not activate additional keys when attempting to use desired. 20

Some i. Pad and i. Phone Applications • i. Mean word prediction • My. Voice Communication Aid Support 21

i. Pad and i. Phone Applications • Assistive Chat • Predict. Able 22

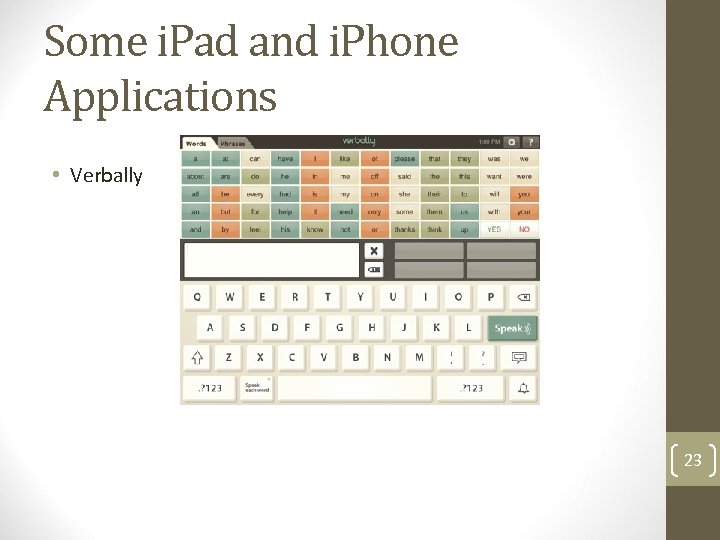

Some i. Pad and i. Phone Applications • Verbally 23

Resources • ASHA (n. d. ). Speech for People With Tracheostomies or Ventilators. American Speech. Language-Hearing Association. Retrieved April 20, 2011, from http: //www. asha. org/public/speech/disorders/tracheostomies. htm • Ahern, K. (2007, May 29). More Commercial Low-Tech AAC Boards. Teaching Learners with Multiple Special Needs. Retrieved April 20, 2011, from http: //teachinglearnerswithmultipleneeds. blogspot. com/2007/05/more-commercial-lowtech-aac-boards. html • Balbata, Barnes, Bird, Byers, Joffe, Kerr, Stevens & La Trobe University (2006). Dysarthria. Best Practice Makes Perfect. Retrieved April 20, 2011, from http: //www. latrobe. edu. au/hcs/projects/preschoolspeechlanguage/dysarthria. html • Donald, F. (2000). Motor Speech Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar Cengage Learning. • GBS/CIDP Foundation International. Retrieved April 20, 2011, from http: //www. gbscidp. org/index. html • i. Phone/i. Pad Apps for AAC (2011). Spectronics: Inclusive Learning Technologies. Retrieved April 20, 2011, from http: //www. spectronicsinoz. com/article/iphoneipad-apps-for-aac 24

Resources • Mc. Caffrey, Ph. D. , P. (n. d. ). Chapter 14. Dysarthria: Characteristics, Prognosis, Remediation. The Neuroscience on the Web Series: CMSD 642 Neuropathologies of Swallowing and Speech. Retrieved from http: //www. csuchico. edu/~pmccaffrey//syllabi/SPPA 342/342 unit 14. html • Mc. Henry, M. A. (2003). The Effect of Pacing Strategies on the Variability of Speech Movement Sequences in Dysarthria. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 46, 702 -710. Retrieved April 20, 2011, from http: //jslhr. asha. org/cgi/reprint/46/3/702 • Mc. Neil, M. R. (Ed). Clinical Management of Sensorimotor Speech Disorders. 2 nd Edition. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers. 2009. • Parry, G. J. (2007). Guillain-Barre Syndrome: From Diagnosis to Recovery. New York, N. Y. : Demos Medical Publishing. • Patel, R. (2002). Prosodic Control in Severe Dysarthria: Preserved Ability to Mark the Question-Statement Contras. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 45, 858870. Retrieved April 20, 2011. • Scott, J. (1998). Low-Tech Methods of Augmentative Communication in Practice: An Introduction. Retrieved April 20, 2011, from http: //www. acipscotland. org. uk/Scott. pdf 25

ab28d5ec737ad76f5999314292a7efdc.ppt