57fddf5ba175fccca9feb58cc89d0775.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 70

GRS LX 700 Language Acquisition and Linguistic Theory Week 14. Language disorders and course overview

GRS LX 700 Language Acquisition and Linguistic Theory Week 14. Language disorders and course overview

Dissociations n Language is developmentally dissociable from other cognitive functions. n Specific Language Impairment n n Cover term for situation where language lags behind in otherwise normal cognitive development Williams Syndrome n Cognitive impairment, but language developing relatively normally.

Dissociations n Language is developmentally dissociable from other cognitive functions. n Specific Language Impairment n n Cover term for situation where language lags behind in otherwise normal cognitive development Williams Syndrome n Cognitive impairment, but language developing relatively normally.

SLI Language is slower to emerge n Trouble with some—but not all— inflectional morphology n Some genetic component, seems to run in families. n

SLI Language is slower to emerge n Trouble with some—but not all— inflectional morphology n Some genetic component, seems to run in families. n

SLI and OI n n n Optional infinitives in normally developing children has the appearance of a maturational constraint. In principle, it might be delayed in some populations. In a minor way by environmental factors, but perhaps in a more significant way due to genetic factors. Given the association of SLI and apparent problems with agreement morphology, perhaps what is happening in SLI is that the OI stage simply lasts longer. n Rice & Wexler (1996) explore this—in part to see if this can serve as a testable “marker” to allow for diagnosis of SLI.

SLI and OI n n n Optional infinitives in normally developing children has the appearance of a maturational constraint. In principle, it might be delayed in some populations. In a minor way by environmental factors, but perhaps in a more significant way due to genetic factors. Given the association of SLI and apparent problems with agreement morphology, perhaps what is happening in SLI is that the OI stage simply lasts longer. n Rice & Wexler (1996) explore this—in part to see if this can serve as a testable “marker” to allow for diagnosis of SLI.

Rice & Wexler (1996) n n n Subjects: 37 5 yo SLI, 45 5 yo ND, 40 3 yo ND Methods: spontaneous & elicited Success on -s, -ed, be, do: n n Success on -ing, plural -s, in/on n n About half of AM, same or worse than LM As good as AM, LM (which are as good as each other) Conclusion: It’s not just a delay of inflection. It’s related to tense, as we might expect of an extended optional infinitive stage. n Plural -s vs. 3 sg -s differ. Can’t be salience.

Rice & Wexler (1996) n n n Subjects: 37 5 yo SLI, 45 5 yo ND, 40 3 yo ND Methods: spontaneous & elicited Success on -s, -ed, be, do: n n Success on -ing, plural -s, in/on n n About half of AM, same or worse than LM As good as AM, LM (which are as good as each other) Conclusion: It’s not just a delay of inflection. It’s related to tense, as we might expect of an extended optional infinitive stage. n Plural -s vs. 3 sg -s differ. Can’t be salience.

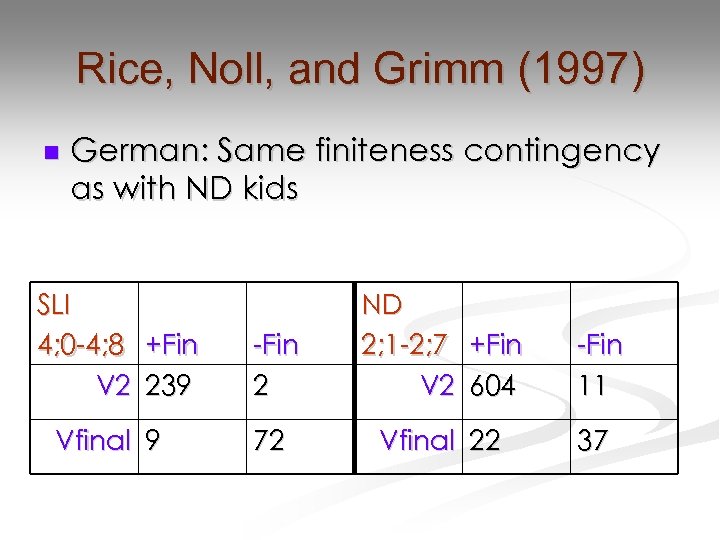

Rice, Noll, and Grimm (1997) n German: Same finiteness contingency as with ND kids SLI 4; 0 -4; 8 +Fin V 2 239 Vfinal 9 -Fin 2 ND 2; 1 -2; 7 +Fin V 2 604 -Fin 11 72 Vfinal 22 37

Rice, Noll, and Grimm (1997) n German: Same finiteness contingency as with ND kids SLI 4; 0 -4; 8 +Fin V 2 239 Vfinal 9 -Fin 2 ND 2; 1 -2; 7 +Fin V 2 604 -Fin 11 72 Vfinal 22 37

Wexler, Schütze, Rice (1998) n Testing subject case (ATOM).

Wexler, Schütze, Rice (1998) n Testing subject case (ATOM).

Rice, Wexler, Redmond (1999) n Judgment task on agreement n n n (“Language good/not so good”). A = measure of discrimination, 1=perfect. BA=bad agreement, DI=dropped ing.

Rice, Wexler, Redmond (1999) n Judgment task on agreement n n n (“Language good/not so good”). A = measure of discrimination, 1=perfect. BA=bad agreement, DI=dropped ing.

Pragmatics v. syntax n If SLI is a very specific deficit in the syntactic/computational model, it also provides an opportunity to test some of the explanations that have relied on independent development of a pragmatics component. n Null subjects: Kids assign “very strong topic” too liberally and drop subjects with finite verbs. n n Schaeffer et al. (2001) Principle B: Kids allow “guises” (coreferential but not coindexed references), resulting in apparent violations of Principle B. n Borgeson (2004)

Pragmatics v. syntax n If SLI is a very specific deficit in the syntactic/computational model, it also provides an opportunity to test some of the explanations that have relied on independent development of a pragmatics component. n Null subjects: Kids assign “very strong topic” too liberally and drop subjects with finite verbs. n n Schaeffer et al. (2001) Principle B: Kids allow “guises” (coreferential but not coindexed references), resulting in apparent violations of Principle B. n Borgeson (2004)

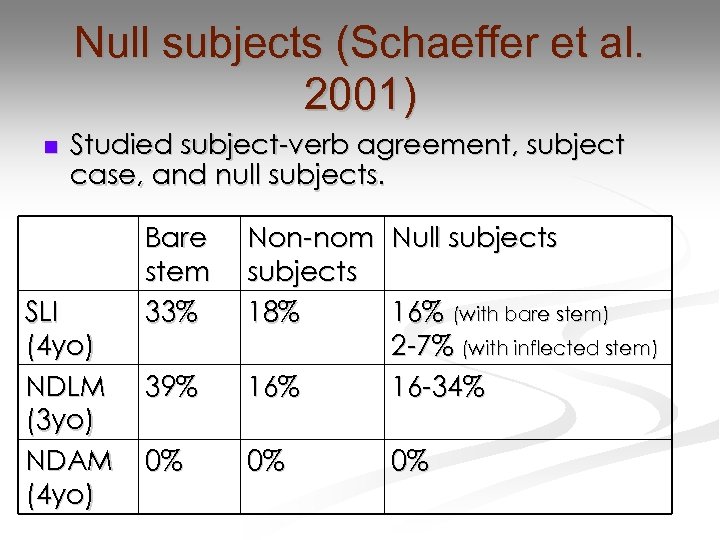

Null subjects (Schaeffer et al. 2001) n Studied subject-verb agreement, subject case, and null subjects. SLI (4 yo) NDLM (3 yo) NDAM (4 yo) Bare stem 33% 39% Non-nom Null subjects 18% 16% (with bare stem) 2 -7% (with inflected stem) 16% 16 -34% 0% 0% 0%

Null subjects (Schaeffer et al. 2001) n Studied subject-verb agreement, subject case, and null subjects. SLI (4 yo) NDLM (3 yo) NDAM (4 yo) Bare stem 33% 39% Non-nom Null subjects 18% 16% (with bare stem) 2 -7% (with inflected stem) 16% 16 -34% 0% 0% 0%

Borgeson (2004) n SLI kids (vocab. Match, 5 -6 yo ND) n Principle P errors (MB points to her): n n ND: 42% Principle B errors (e. b. points to her): n n SLI: 28% SLI: 20% ND: 0% Also explored the effects of bias in the contexts, and found ND kids were driven by the bias all the time for Pr. P errors, but the SLI kids were much less so. Bias played no role for Pr. B. errors. n But cf. van der Lely & Stollwerck (1997). SLI 9 -12 yo. Match/mismatch. Appear to take X-self to be any selfdirected action (chance on B tickles B mismatch for B says M is tickling himself). Chance on (B says) M is tickling him (mismatch: self). Results on e. b. washes him difficult to interpret; SLI kids didn’t do very well. Guasti: problem with quantifiers? As for difference: task?

Borgeson (2004) n SLI kids (vocab. Match, 5 -6 yo ND) n Principle P errors (MB points to her): n n ND: 42% Principle B errors (e. b. points to her): n n SLI: 28% SLI: 20% ND: 0% Also explored the effects of bias in the contexts, and found ND kids were driven by the bias all the time for Pr. P errors, but the SLI kids were much less so. Bias played no role for Pr. B. errors. n But cf. van der Lely & Stollwerck (1997). SLI 9 -12 yo. Match/mismatch. Appear to take X-self to be any selfdirected action (chance on B tickles B mismatch for B says M is tickling himself). Chance on (B says) M is tickling him (mismatch: self). Results on e. b. washes him difficult to interpret; SLI kids didn’t do very well. Guasti: problem with quantifiers? As for difference: task?

SLI as Agreement problem? n Clahsen et al. report German SLI kids quite adept with tense marking, and quite bad at agreement marking. n n Also found in English (Clahsen et al. ), Greek (Tsimpli & Stavrakaki 1999). But not in Italian (Cipriani et al. 1998). Not expected if SLI=EOI. Not really clear to me what the source of difference is between Wexler, Rice, et al. ’s results and Clahsen et al. ’s results. n n RNG suggest difference may arise in data interpretation, both in contingency analysis and what was counted as what (participles, V 2), or even in subject selection. Plus, quite possibly SLI>EOI.

SLI as Agreement problem? n Clahsen et al. report German SLI kids quite adept with tense marking, and quite bad at agreement marking. n n Also found in English (Clahsen et al. ), Greek (Tsimpli & Stavrakaki 1999). But not in Italian (Cipriani et al. 1998). Not expected if SLI=EOI. Not really clear to me what the source of difference is between Wexler, Rice, et al. ’s results and Clahsen et al. ’s results. n n RNG suggest difference may arise in data interpretation, both in contingency analysis and what was counted as what (participles, V 2), or even in subject selection. Plus, quite possibly SLI>EOI.

![Wexler, Schaeffer, Bol (2004) n n n Agr: /t/ = [-1, +sg/-past], /Ø/ = Wexler, Schaeffer, Bol (2004) n n n Agr: /t/ = [-1, +sg/-past], /Ø/ =](https://present5.com/presentation/57fddf5ba175fccca9feb58cc89d0775/image-13.jpg) Wexler, Schaeffer, Bol (2004) n n n Agr: /t/ = [-1, +sg/-past], /Ø/ = [+sg], /n/= [] T: /Ø/ = [ ], /te/=[+past] Schwa is inserted following phonological rules present ik werk jij werk-t hij/zij/het werk-t 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg wij werk-en 1 pl jullie werk-en 2 pl zij werk-en 3 pl past ik werk-te jij werk-te hij/zij/het werk-te 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg wij werk-te-n 1 pl jullie werk-te-n 2 pl zij werk-te-n 3 pl

Wexler, Schaeffer, Bol (2004) n n n Agr: /t/ = [-1, +sg/-past], /Ø/ = [+sg], /n/= [] T: /Ø/ = [ ], /te/=[+past] Schwa is inserted following phonological rules present ik werk jij werk-t hij/zij/het werk-t 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg wij werk-en 1 pl jullie werk-en 2 pl zij werk-en 3 pl past ik werk-te jij werk-te hij/zij/het werk-te 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg wij werk-te-n 1 pl jullie werk-te-n 2 pl zij werk-te-n 3 pl

![Wexler, Schaeffer, Bol (2004) n n n Agr: /t/ = [-1, +sg/-past], /Ø/ = Wexler, Schaeffer, Bol (2004) n n n Agr: /t/ = [-1, +sg/-past], /Ø/ =](https://present5.com/presentation/57fddf5ba175fccca9feb58cc89d0775/image-14.jpg) Wexler, Schaeffer, Bol (2004) n n n Agr: /t/ = [-1, +sg/-past], /Ø/ = [+sg], /n/= [] T: /Ø/ = [ ], /te/=[+past] Root infinitives are expected whenever Agr is missing and T is not past: werk-Ø-n. n n (Predicts more RIs in English than in Dutch) Theoretical question about morphology: does [-past] mean “+present” or “not +past”? Makes different predictions about what kinds of “errors” kids will make during OI stage. Suppose subject is 3 sg, and T is missing. T is spelled out as Ø. Agr is spelled out either as Ø (if -past=+present) or t (if past=not +past). Latter will look like present tense—if past tense was intended, it will look like a tense error. n So: we can decide this theoretical question on the basis of whether kids in Dutch make bare-stem errors with 3 sg subjects.

Wexler, Schaeffer, Bol (2004) n n n Agr: /t/ = [-1, +sg/-past], /Ø/ = [+sg], /n/= [] T: /Ø/ = [ ], /te/=[+past] Root infinitives are expected whenever Agr is missing and T is not past: werk-Ø-n. n n (Predicts more RIs in English than in Dutch) Theoretical question about morphology: does [-past] mean “+present” or “not +past”? Makes different predictions about what kinds of “errors” kids will make during OI stage. Suppose subject is 3 sg, and T is missing. T is spelled out as Ø. Agr is spelled out either as Ø (if -past=+present) or t (if past=not +past). Latter will look like present tense—if past tense was intended, it will look like a tense error. n So: we can decide this theoretical question on the basis of whether kids in Dutch make bare-stem errors with 3 sg subjects.

![Wexler, Schaeffer, Bol (2004) n n n Agr: /t/ = [-1, +sg/-past], /Ø/ = Wexler, Schaeffer, Bol (2004) n n n Agr: /t/ = [-1, +sg/-past], /Ø/ =](https://present5.com/presentation/57fddf5ba175fccca9feb58cc89d0775/image-15.jpg) Wexler, Schaeffer, Bol (2004) n n n Agr: /t/ = [-1, +sg/-past], /Ø/ = [+sg], /n/= [] T: /Ø/ = [ ], /te/=[+past] Dutch is V 2. We expect that it’s going to turn out like German, finite verbs in second position, nonfinite verbs in final position. Except: Sometimes a form might still look finite, even if T or Agr is missing. So: The predictions are much more complicated. We can also use this to test whether it is T or Agr (or perhaps both) that is crucial in making the verb raise to C in V 2 languages.

Wexler, Schaeffer, Bol (2004) n n n Agr: /t/ = [-1, +sg/-past], /Ø/ = [+sg], /n/= [] T: /Ø/ = [ ], /te/=[+past] Dutch is V 2. We expect that it’s going to turn out like German, finite verbs in second position, nonfinite verbs in final position. Except: Sometimes a form might still look finite, even if T or Agr is missing. So: The predictions are much more complicated. We can also use this to test whether it is T or Agr (or perhaps both) that is crucial in making the verb raise to C in V 2 languages.

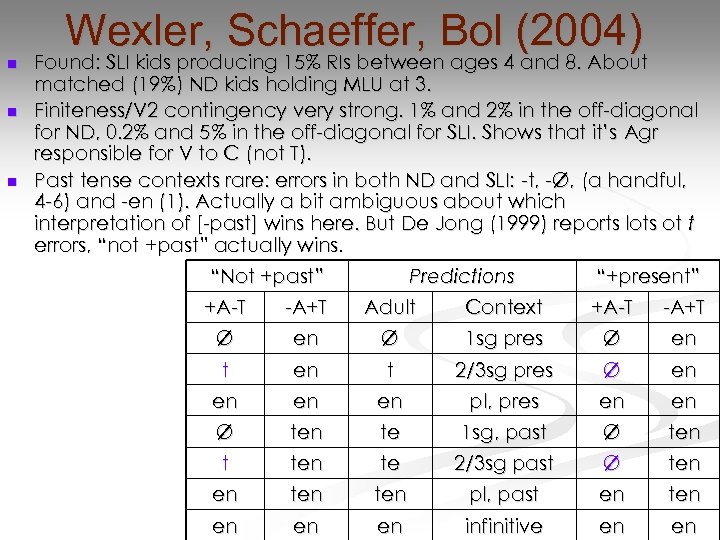

Wexler, Schaeffer, Bol (2004) n n n Found: SLI kids producing 15% RIs between ages 4 and 8. About matched (19%) ND kids holding MLU at 3. Finiteness/V 2 contingency very strong. 1% and 2% in the off-diagonal for ND, 0. 2% and 5% in the off-diagonal for SLI. Shows that it’s Agr responsible for V to C (not T). Past tense contexts rare: errors in both ND and SLI: -t, -Ø, (a handful, 4 -6) and -en (1). Actually a bit ambiguous about which interpretation of [-past] wins here. But De Jong (1999) reports lots ot t errors, “not +past” actually wins. “Not +past” Predictions “+present” +A-T -A+T Adult Context +A-T -A+T Ø en Ø 1 sg pres Ø en t 2/3 sg pres Ø en en pl, pres en en Ø ten te 1 sg, past Ø ten te 2/3 sg past Ø ten en ten pl, past en ten en infinitive en en

Wexler, Schaeffer, Bol (2004) n n n Found: SLI kids producing 15% RIs between ages 4 and 8. About matched (19%) ND kids holding MLU at 3. Finiteness/V 2 contingency very strong. 1% and 2% in the off-diagonal for ND, 0. 2% and 5% in the off-diagonal for SLI. Shows that it’s Agr responsible for V to C (not T). Past tense contexts rare: errors in both ND and SLI: -t, -Ø, (a handful, 4 -6) and -en (1). Actually a bit ambiguous about which interpretation of [-past] wins here. But De Jong (1999) reports lots ot t errors, “not +past” actually wins. “Not +past” Predictions “+present” +A-T -A+T Adult Context +A-T -A+T Ø en Ø 1 sg pres Ø en t 2/3 sg pres Ø en en pl, pres en en Ø ten te 1 sg, past Ø ten te 2/3 sg past Ø ten en ten pl, past en ten en infinitive en en

Williams Syndrome The other side of the dissociation. n Severe cognitive deficit, probably traceable to problems with visuospatial processing. n But language function is comparatively very good. n Inflection n Binding theory n Passives n

Williams Syndrome The other side of the dissociation. n Severe cognitive deficit, probably traceable to problems with visuospatial processing. n But language function is comparatively very good. n Inflection n Binding theory n Passives n

Zukowski (2001) n Looked in detail at several structures in WS, and found much that matched ND kids.

Zukowski (2001) n Looked in detail at several structures in WS, and found much that matched ND kids.

Zukowski (2001) n A few things did differentiate WS kids

Zukowski (2001) n A few things did differentiate WS kids

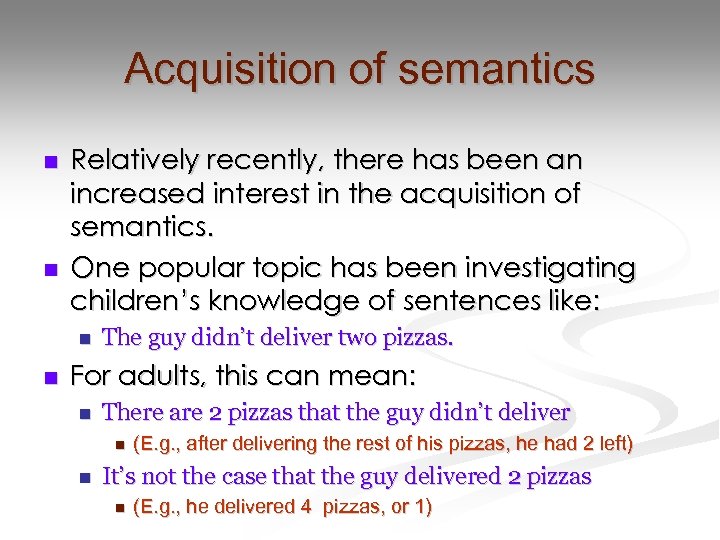

Acquisition of semantics n n Relatively recently, there has been an increased interest in the acquisition of semantics. One popular topic has been investigating children’s knowledge of sentences like: n n The guy didn’t deliver two pizzas. For adults, this can mean: n There are 2 pizzas that the guy didn’t deliver n n (E. g. , after delivering the rest of his pizzas, he had 2 left) It’s not the case that the guy delivered 2 pizzas n (E. g. , he delivered 4 pizzas, or 1)

Acquisition of semantics n n Relatively recently, there has been an increased interest in the acquisition of semantics. One popular topic has been investigating children’s knowledge of sentences like: n n The guy didn’t deliver two pizzas. For adults, this can mean: n There are 2 pizzas that the guy didn’t deliver n n (E. g. , after delivering the rest of his pizzas, he had 2 left) It’s not the case that the guy delivered 2 pizzas n (E. g. , he delivered 4 pizzas, or 1)

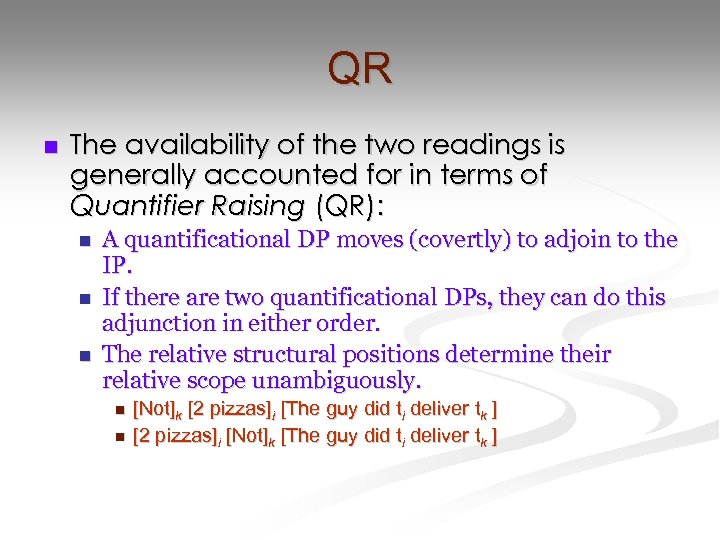

QR n The availability of the two readings is generally accounted for in terms of Quantifier Raising (QR): n n n A quantificational DP moves (covertly) to adjoin to the IP. If there are two quantificational DPs, they can do this adjunction in either order. The relative structural positions determine their relative scope unambiguously. n n [Not]k [2 pizzas]i [The guy did ti deliver tk ] [2 pizzas]i [Not]k [The guy did ti deliver tk ]

QR n The availability of the two readings is generally accounted for in terms of Quantifier Raising (QR): n n n A quantificational DP moves (covertly) to adjoin to the IP. If there are two quantificational DPs, they can do this adjunction in either order. The relative structural positions determine their relative scope unambiguously. n n [Not]k [2 pizzas]i [The guy did ti deliver tk ] [2 pizzas]i [Not]k [The guy did ti deliver tk ]

Musolino’s (2000) OOI n Musolino (2000) found that kids seem not to reverse scope relations found in the surface form (the Observation of Isomorphism). Every horse didn’t jump over the fence. n The detective didn’t find some guys n The smurf didn’t buy every orange. n

Musolino’s (2000) OOI n Musolino (2000) found that kids seem not to reverse scope relations found in the surface form (the Observation of Isomorphism). Every horse didn’t jump over the fence. n The detective didn’t find some guys n The smurf didn’t buy every orange. n

Musolino & Lidz (2002) n n TVJT: Dramatic preference on the part of kids (4 yo) for the surface scope. Linear order? Or structure (c-command? ) n n The detective didn’t find 2 guys. Tested kids on the same thing in Kannada (where negation is at the end). Same result: It’s c-command that matters. For a while, this was thought to be an aspect of children’s competence. Their grammar, e. g. , lacked QR.

Musolino & Lidz (2002) n n TVJT: Dramatic preference on the part of kids (4 yo) for the surface scope. Linear order? Or structure (c-command? ) n n The detective didn’t find 2 guys. Tested kids on the same thing in Kannada (where negation is at the end). Same result: It’s c-command that matters. For a while, this was thought to be an aspect of children’s competence. Their grammar, e. g. , lacked QR.

Gualmini (2003) n By manipulating the context, however, Gualmini (2003) showed that kids could access the “inverse scope” interpretation. It just has to do what would be a sensible/felicitous thing to say. n Grover orders 4 pizzas from the Troll, who supposed to deliver them all to Grover. But the Troll drives too fast and loses 2. n n n The Troll didn’t deliver some pizzas. The Troll didn’t lose some pizzas. 90% accept 50% accept One points out a discrepancy between the expectations and what actually happened, one doesn’t.

Gualmini (2003) n By manipulating the context, however, Gualmini (2003) showed that kids could access the “inverse scope” interpretation. It just has to do what would be a sensible/felicitous thing to say. n Grover orders 4 pizzas from the Troll, who supposed to deliver them all to Grover. But the Troll drives too fast and loses 2. n n n The Troll didn’t deliver some pizzas. The Troll didn’t lose some pizzas. 90% accept 50% accept One points out a discrepancy between the expectations and what actually happened, one doesn’t.

Hulsey, Hacquard, Fox, & Gualmini (2004) n The Question-Answer Requirement on TVJ tasks: The test sentence must be understood as an answer to the “question under discussion. ” n n n Will the Troll deliver all of the pizzas? Yes (the Troll will deliver them all) No (the Troll will not deliver them all) #There are some pizzas delivered by the Troll. “Isomorphism” isn’t even really a default. n Tested passives (when compared to actives, teases apart isomorphism and QAR): n n Some pizzas were not delivered. Some pizza were not lost. 94% (adult 100%) 43% (adult 93%)

Hulsey, Hacquard, Fox, & Gualmini (2004) n The Question-Answer Requirement on TVJ tasks: The test sentence must be understood as an answer to the “question under discussion. ” n n n Will the Troll deliver all of the pizzas? Yes (the Troll will deliver them all) No (the Troll will not deliver them all) #There are some pizzas delivered by the Troll. “Isomorphism” isn’t even really a default. n Tested passives (when compared to actives, teases apart isomorphism and QAR): n n Some pizzas were not delivered. Some pizza were not lost. 94% (adult 100%) 43% (adult 93%)

Kids and QR, Lidz et al. (2003) n (BUCLD 28) More direct test of whether kids have QR by looking at constructions where QR is necessary in order to get the right interpretation. n Quantifier-variable binding n Kermit n kissed every dancer before she went on stage Antecedent-Contained Deletion (ACD) n Miss Red jumped over every frog that Miss Black did.

Kids and QR, Lidz et al. (2003) n (BUCLD 28) More direct test of whether kids have QR by looking at constructions where QR is necessary in order to get the right interpretation. n Quantifier-variable binding n Kermit n kissed every dancer before she went on stage Antecedent-Contained Deletion (ACD) n Miss Red jumped over every frog that Miss Black did.

Quantifier-variable binding n Subject QNP (QR not necessary) n n Object QNP (QR required) n n Every dancer kissed Kermit before she went on stage. Kermit kissed every dancer before she went on stage. Kids about 4; 6. Acted like adults, yes where yes was required, no where no was required.

Quantifier-variable binding n Subject QNP (QR not necessary) n n Object QNP (QR required) n n Every dancer kissed Kermit before she went on stage. Kermit kissed every dancer before she went on stage. Kids about 4; 6. Acted like adults, yes where yes was required, no where no was required.

ACD n VP ellipsis involves interpreting an “empty VP” as a copy of the “audible VP” (or leaving an identical VP unpronounced). n n John bought a tape and Mary did too. ACD: the elided VP is inside the audible one. n MR jumped over every frog that MB did. n n n Audible: jumped over every frog that MB did [VP] Elided: jumped over … what? Infinite regress: MR jumped over every frog that MB jumped over every from that… QR solves the problem, though: [Every frog that MB [jumped over t]]i MR [jumped over ti].

ACD n VP ellipsis involves interpreting an “empty VP” as a copy of the “audible VP” (or leaving an identical VP unpronounced). n n John bought a tape and Mary did too. ACD: the elided VP is inside the audible one. n MR jumped over every frog that MB did. n n n Audible: jumped over every frog that MB did [VP] Elided: jumped over … what? Infinite regress: MR jumped over every frog that MB jumped over every from that… QR solves the problem, though: [Every frog that MB [jumped over t]]i MR [jumped over ti].

ACD n MB jumped over every frog that MR did QR: relative clause reading n No QR: coordinated reading? n n MB jumped over every frog and MB did too. Kids about 4; 5 act basically like adults. n So, they must have QR. Whatever OOI is about, it isn’t about kids lacking QR from their grammar. n

ACD n MB jumped over every frog that MR did QR: relative clause reading n No QR: coordinated reading? n n MB jumped over every frog and MB did too. Kids about 4; 5 act basically like adults. n So, they must have QR. Whatever OOI is about, it isn’t about kids lacking QR from their grammar. n

Musolino & Lidz (2003) n Adults can be made to act like kids with respect to isomorphism too, in fact. n n Try a context where both interpretations are true… n n Cookie Monster didn’t eat two slices of pizza. E. g. : CM gets 3, but eats 1. …justifications given seemed to be isomorphic (75% vs. 7. 5% reverse, the rest unclear).

Musolino & Lidz (2003) n Adults can be made to act like kids with respect to isomorphism too, in fact. n n Try a context where both interpretations are true… n n Cookie Monster didn’t eat two slices of pizza. E. g. : CM gets 3, but eats 1. …justifications given seemed to be isomorphic (75% vs. 7. 5% reverse, the rest unclear).

Entailments n E. g. , Minai, Meroni, & Crain (2004): n n n n Can be used as an argument for an innateness hypothesis vs. constructional analogy. Kids (mean 4; 10), 95% on #2. 90% on #4. 89% on #5. n n John has a black dog > John has a dog Every boy has a black dog > Every boy has a dog Nobody has a black dog < Nobody has a dog Every black dog caught a cicada < Every dog caught a cicada Nobody caught every black dog > Nobody caught every dog Nobody could feed every (big) koala bear Notice that this is a bit early—weren’t Chien & Wexler (1990) relying on kids’ inability to do quantifiers?

Entailments n E. g. , Minai, Meroni, & Crain (2004): n n n n Can be used as an argument for an innateness hypothesis vs. constructional analogy. Kids (mean 4; 10), 95% on #2. 90% on #4. 89% on #5. n n John has a black dog > John has a dog Every boy has a black dog > Every boy has a dog Nobody has a black dog < Nobody has a dog Every black dog caught a cicada < Every dog caught a cicada Nobody caught every black dog > Nobody caught every dog Nobody could feed every (big) koala bear Notice that this is a bit early—weren’t Chien & Wexler (1990) relying on kids’ inability to do quantifiers?

Language attrition n It is a very common phenomenon that, having learned an L 2 and having become quite proficient, one will still “forget” how to use it after a period of non-use. n While very common, it’s not very surprising—it’s like calculus. If L 2 is a skill like calculus, we’d expect this.

Language attrition n It is a very common phenomenon that, having learned an L 2 and having become quite proficient, one will still “forget” how to use it after a period of non-use. n While very common, it’s not very surprising—it’s like calculus. If L 2 is a skill like calculus, we’d expect this.

L 1 attrition n Much more surprising is the fact that sometimes under the influence of a dominant L 2, skill in the L 1 seems to go. n Consider the UG/parameter model; a kid’s LAD faced with PLD, automatically sets the parameters in his/her head to match those exhibited by the linguistic input. L 1 is effortless, fast, uniformly successful… biologically driven, not learning in the normal sense of learning a skill. So how could it suffer attrition? What are you left with? n

L 1 attrition n Much more surprising is the fact that sometimes under the influence of a dominant L 2, skill in the L 1 seems to go. n Consider the UG/parameter model; a kid’s LAD faced with PLD, automatically sets the parameters in his/her head to match those exhibited by the linguistic input. L 1 is effortless, fast, uniformly successful… biologically driven, not learning in the normal sense of learning a skill. So how could it suffer attrition? What are you left with? n

UG in L 2 A n n We’ve looked at the questions concerning whether when learning a second language, one can adapt the “parameter settings” in the new knowledge to the target settings (where they differ from the L 1 settings), but this is even more dramatic—it would seem to actually be altering the L 1 settings. It behooves us to look carefullier at this; do attrited speakers seem to have changed parameter settings?

UG in L 2 A n n We’ve looked at the questions concerning whether when learning a second language, one can adapt the “parameter settings” in the new knowledge to the target settings (where they differ from the L 1 settings), but this is even more dramatic—it would seem to actually be altering the L 1 settings. It behooves us to look carefullier at this; do attrited speakers seem to have changed parameter settings?

Italian English n Italian is a “null subject” language that allows the subject to be dropped in most cases where in English we’d use a pronoun n n (Possible to use a pronoun in Italian, but it conveys something pragmatic: contrastive focus or change in topic) English is a “non-null-subject” language that does not allow the subject to be dropped out, pronouns are required (even sometimes “meaningless” like it or there). Not required that a pronoun signal a change in topic.

Italian English n Italian is a “null subject” language that allows the subject to be dropped in most cases where in English we’d use a pronoun n n (Possible to use a pronoun in Italian, but it conveys something pragmatic: contrastive focus or change in topic) English is a “non-null-subject” language that does not allow the subject to be dropped out, pronouns are required (even sometimes “meaningless” like it or there). Not required that a pronoun signal a change in topic.

Italian, null subjects n n Q: Perchè Maria è uscite? ‘Why did M leave? ’ A 1: Lei ha deciso di fare una passeggiata. A 2: Ha deciso di fare une passenggiata. ‘She decided to take a walk. ’ Monolingual Italian speaker would say A 2, but English-immersed native Italian speaker will optionally produce (and accept) A 1. (Sorace 2000)

Italian, null subjects n n Q: Perchè Maria è uscite? ‘Why did M leave? ’ A 1: Lei ha deciso di fare una passeggiata. A 2: Ha deciso di fare une passenggiata. ‘She decided to take a walk. ’ Monolingual Italian speaker would say A 2, but English-immersed native Italian speaker will optionally produce (and accept) A 1. (Sorace 2000)

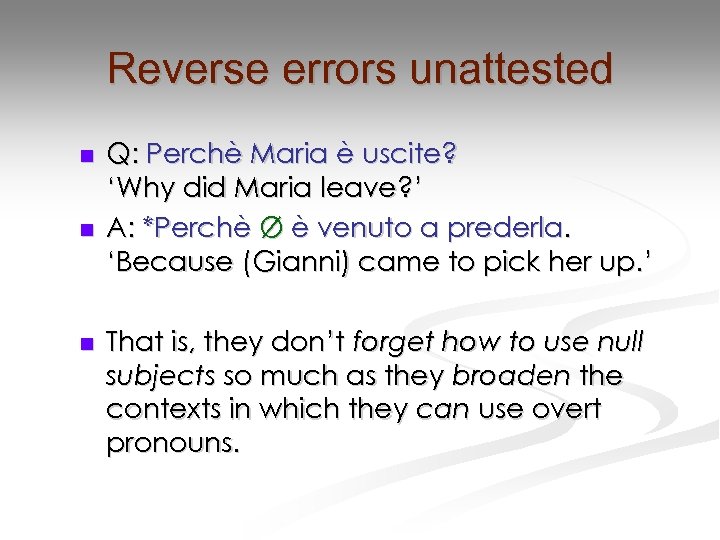

Reverse errors unattested n n n Q: Perchè Maria è uscite? ‘Why did Maria leave? ’ A: *Perchè Ø è venuto a prederla. ‘Because (Gianni) came to pick her up. ’ That is, they don’t forget how to use null subjects so much as they broaden the contexts in which they can use overt pronouns.

Reverse errors unattested n n n Q: Perchè Maria è uscite? ‘Why did Maria leave? ’ A: *Perchè Ø è venuto a prederla. ‘Because (Gianni) came to pick her up. ’ That is, they don’t forget how to use null subjects so much as they broaden the contexts in which they can use overt pronouns.

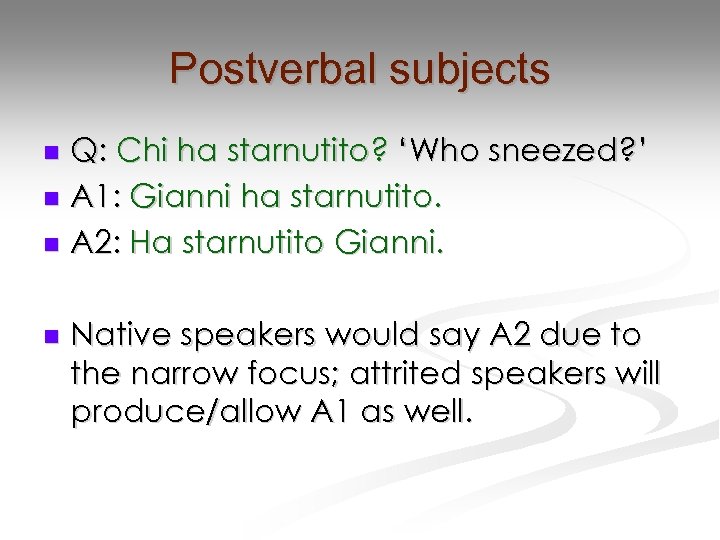

Postverbal subjects Q: Chi ha starnutito? ‘Who sneezed? ’ n A 1: Gianni ha starnutito. n A 2: Ha starnutito Gianni. n n Native speakers would say A 2 due to the narrow focus; attrited speakers will produce/allow A 1 as well.

Postverbal subjects Q: Chi ha starnutito? ‘Who sneezed? ’ n A 1: Gianni ha starnutito. n A 2: Ha starnutito Gianni. n n Native speakers would say A 2 due to the narrow focus; attrited speakers will produce/allow A 1 as well.

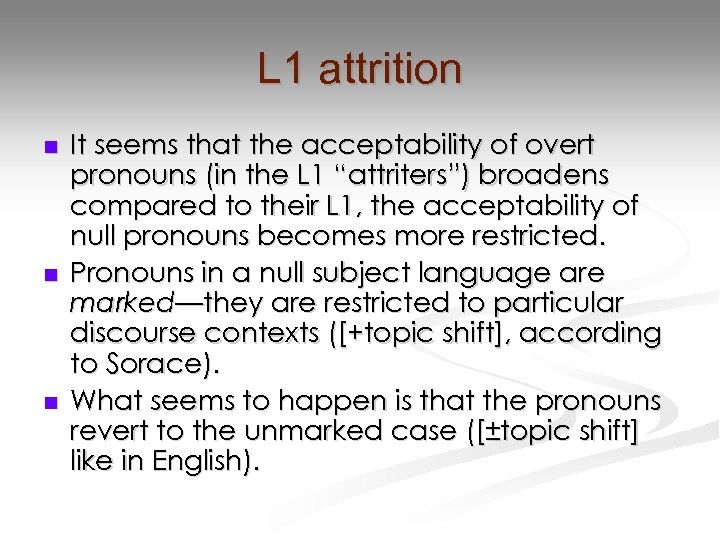

L 1 attrition n It seems that the acceptability of overt pronouns (in the L 1 “attriters”) broadens compared to their L 1, the acceptability of null pronouns becomes more restricted. Pronouns in a null subject language are marked—they are restricted to particular discourse contexts ([+topic shift], according to Sorace). What seems to happen is that the pronouns revert to the unmarked case ([±topic shift] like in English).

L 1 attrition n It seems that the acceptability of overt pronouns (in the L 1 “attriters”) broadens compared to their L 1, the acceptability of null pronouns becomes more restricted. Pronouns in a null subject language are marked—they are restricted to particular discourse contexts ([+topic shift], according to Sorace). What seems to happen is that the pronouns revert to the unmarked case ([±topic shift] like in English).

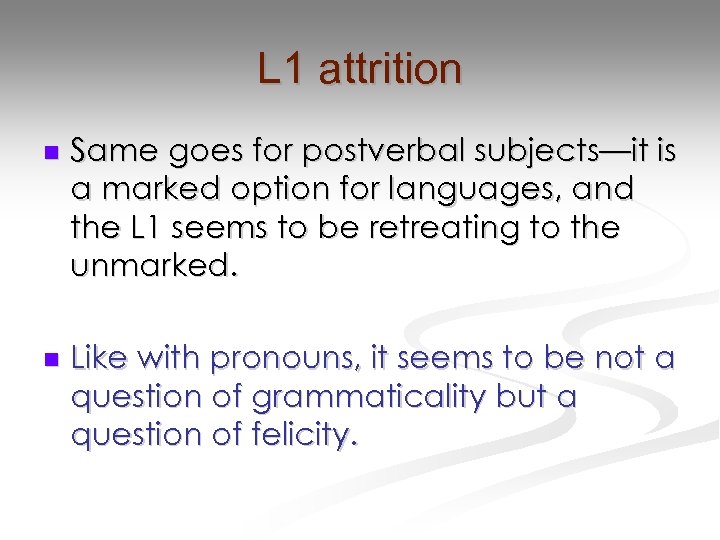

L 1 attrition n Same goes for postverbal subjects—it is a marked option for languages, and the L 1 seems to be retreating to the unmarked. n Like with pronouns, it seems to be not a question of grammaticality but a question of felicity.

L 1 attrition n Same goes for postverbal subjects—it is a marked option for languages, and the L 1 seems to be retreating to the unmarked. n Like with pronouns, it seems to be not a question of grammaticality but a question of felicity.

L 1 attrition n Certain areas of the L 1 grammar are more susceptible to this kind of attrition then others. n Sorace notes that the observed cases of attrition of this sort seem to be the ones involved with discourse and pragmatics, not with fundamental grammatical settings. (The attrited Italian is still a null-subject language, for example—null subjects are still possible and used only in places where null subjects should be allowed).

L 1 attrition n Certain areas of the L 1 grammar are more susceptible to this kind of attrition then others. n Sorace notes that the observed cases of attrition of this sort seem to be the ones involved with discourse and pragmatics, not with fundamental grammatical settings. (The attrited Italian is still a null-subject language, for example—null subjects are still possible and used only in places where null subjects should be allowed).

L 1 attrition So, we’re left with a not-entirelyinconsistent view of the world. n Parameter settings in L 1 appear to be safe, but the discourse-pragmatic constraints seem to be somehow susceptible to high exposure to conflicting constraints in other languages. n

L 1 attrition So, we’re left with a not-entirelyinconsistent view of the world. n Parameter settings in L 1 appear to be safe, but the discourse-pragmatic constraints seem to be somehow susceptible to high exposure to conflicting constraints in other languages. n

Language mixing (Spanish-English) n No, yo sí brincaba en el trampoline when I was a senior. ‘No, I did jump on the trampoline when I was a senior. ’ n La consulta era eight dollars. ‘The office visit was eight dollars. ’ n Well, I keep starting some. Como por un mes todos los días escribo y ya dejo. ‘Well, I keep starting some. For about a month I write everything and then I stop. ’

Language mixing (Spanish-English) n No, yo sí brincaba en el trampoline when I was a senior. ‘No, I did jump on the trampoline when I was a senior. ’ n La consulta era eight dollars. ‘The office visit was eight dollars. ’ n Well, I keep starting some. Como por un mes todos los días escribo y ya dejo. ‘Well, I keep starting some. For about a month I write everything and then I stop. ’

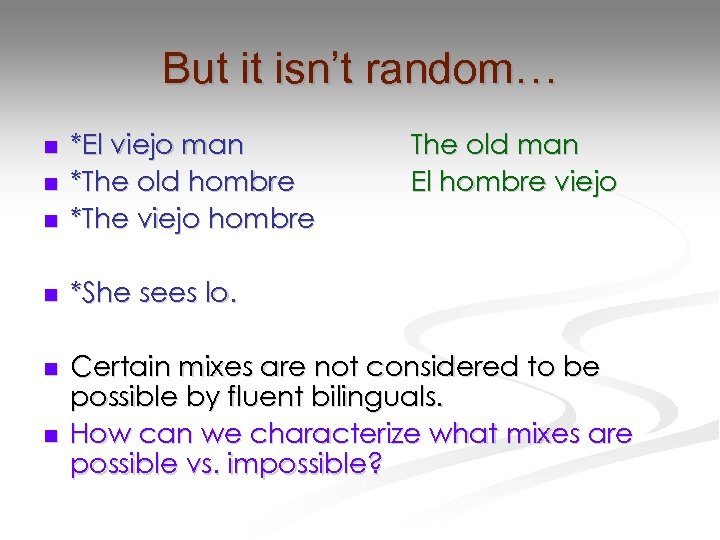

But it isn’t random… n *El viejo man *The old hombre *The viejo hombre n *She sees lo. n Certain mixes are not considered to be possible by fluent bilinguals. How can we characterize what mixes are possible vs. impossible? n n n The old man El hombre viejo

But it isn’t random… n *El viejo man *The old hombre *The viejo hombre n *She sees lo. n Certain mixes are not considered to be possible by fluent bilinguals. How can we characterize what mixes are possible vs. impossible? n n n The old man El hombre viejo

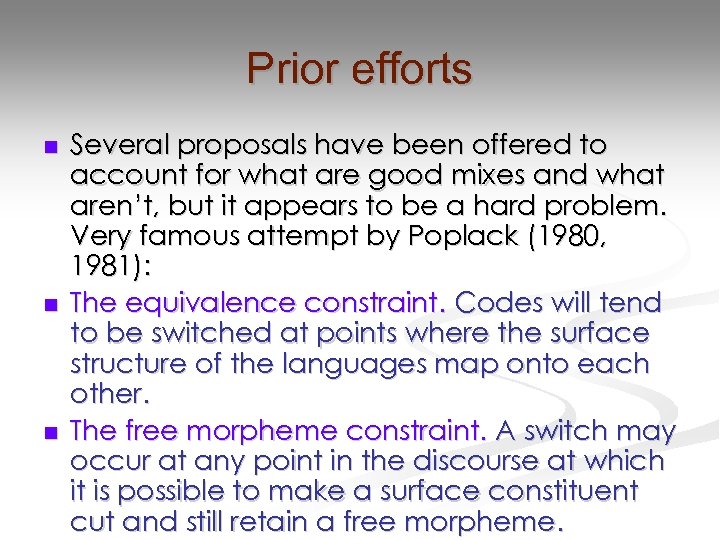

Prior efforts n n n Several proposals have been offered to account for what are good mixes and what aren’t, but it appears to be a hard problem. Very famous attempt by Poplack (1980, 1981): The equivalence constraint. Codes will tend to be switched at points where the surface structure of the languages map onto each other. The free morpheme constraint. A switch may occur at any point in the discourse at which it is possible to make a surface constituent cut and still retain a free morpheme.

Prior efforts n n n Several proposals have been offered to account for what are good mixes and what aren’t, but it appears to be a hard problem. Very famous attempt by Poplack (1980, 1981): The equivalence constraint. Codes will tend to be switched at points where the surface structure of the languages map onto each other. The free morpheme constraint. A switch may occur at any point in the discourse at which it is possible to make a surface constituent cut and still retain a free morpheme.

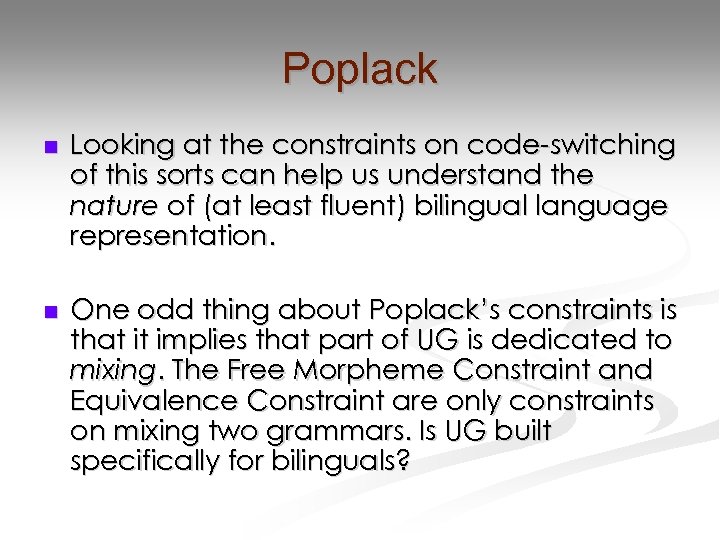

Poplack n Looking at the constraints on code-switching of this sorts can help us understand the nature of (at least fluent) bilingual language representation. n One odd thing about Poplack’s constraints is that it implies that part of UG is dedicated to mixing. The Free Morpheme Constraint and Equivalence Constraint are only constraints on mixing two grammars. Is UG built specifically for bilinguals?

Poplack n Looking at the constraints on code-switching of this sorts can help us understand the nature of (at least fluent) bilingual language representation. n One odd thing about Poplack’s constraints is that it implies that part of UG is dedicated to mixing. The Free Morpheme Constraint and Equivalence Constraint are only constraints on mixing two grammars. Is UG built specifically for bilinguals?

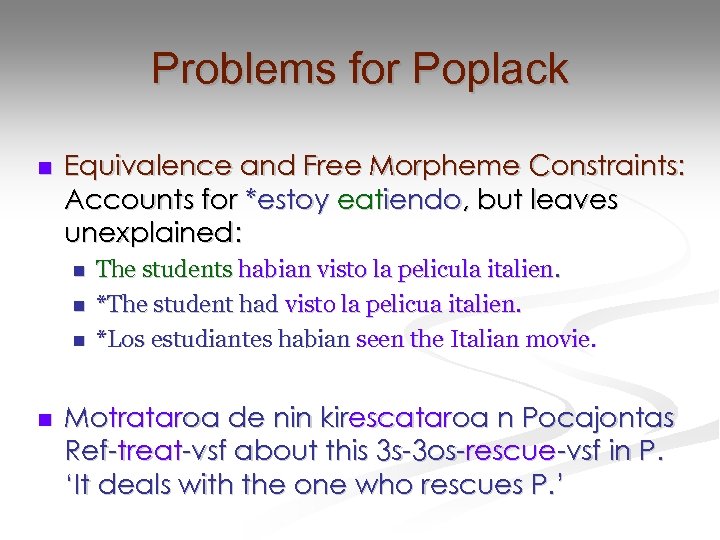

Problems for Poplack n Equivalence and Free Morpheme Constraints: Accounts for *estoy eatiendo, but leaves unexplained: n n The students habian visto la pelicula italien. *The student had visto la pelicua italien. *Los estudiantes habian seen the Italian movie. Motrataroa de nin kirescataroa n Pocajontas Ref-treat-vsf about this 3 s-3 os-rescue-vsf in P. ‘It deals with the one who rescues P. ’

Problems for Poplack n Equivalence and Free Morpheme Constraints: Accounts for *estoy eatiendo, but leaves unexplained: n n The students habian visto la pelicula italien. *The student had visto la pelicua italien. *Los estudiantes habian seen the Italian movie. Motrataroa de nin kirescataroa n Pocajontas Ref-treat-vsf about this 3 s-3 os-rescue-vsf in P. ‘It deals with the one who rescues P. ’

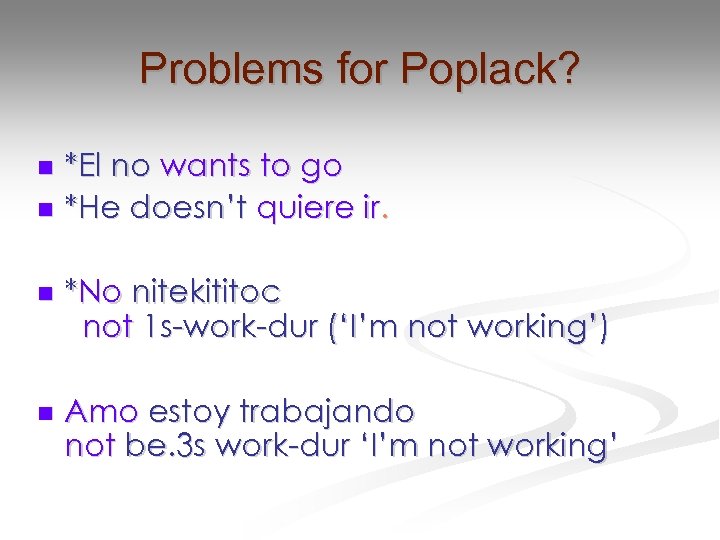

Problems for Poplack? *El no wants to go n *He doesn’t quiere ir. n n *No nitekititoc not 1 s-work-dur (‘I’m not working’) n Amo estoy trabajando not be. 3 s work-dur ‘I’m not working’

Problems for Poplack? *El no wants to go n *He doesn’t quiere ir. n n *No nitekititoc not 1 s-work-dur (‘I’m not working’) n Amo estoy trabajando not be. 3 s work-dur ‘I’m not working’

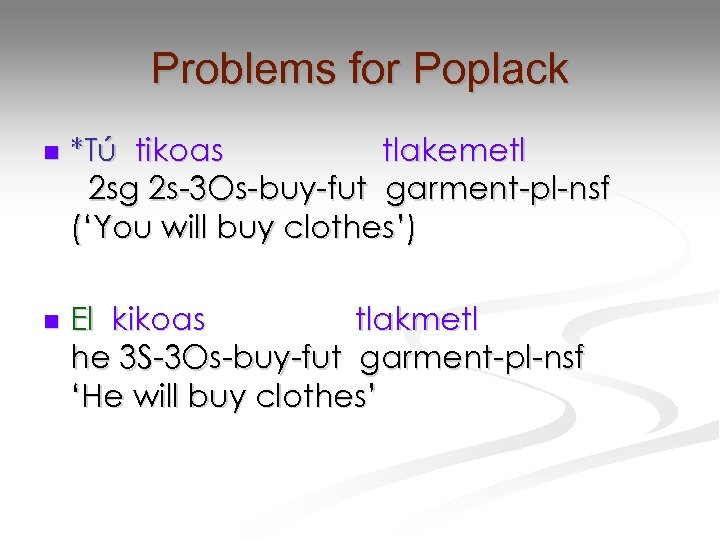

Problems for Poplack n *Tú tikoas tlakemetl 2 sg 2 s-3 Os-buy-fut garment-pl-nsf (‘You will buy clothes’) n El kikoas tlakmetl he 3 S-3 Os-buy-fut garment-pl-nsf ‘He will buy clothes’

Problems for Poplack n *Tú tikoas tlakemetl 2 sg 2 s-3 Os-buy-fut garment-pl-nsf (‘You will buy clothes’) n El kikoas tlakmetl he 3 S-3 Os-buy-fut garment-pl-nsf ‘He will buy clothes’

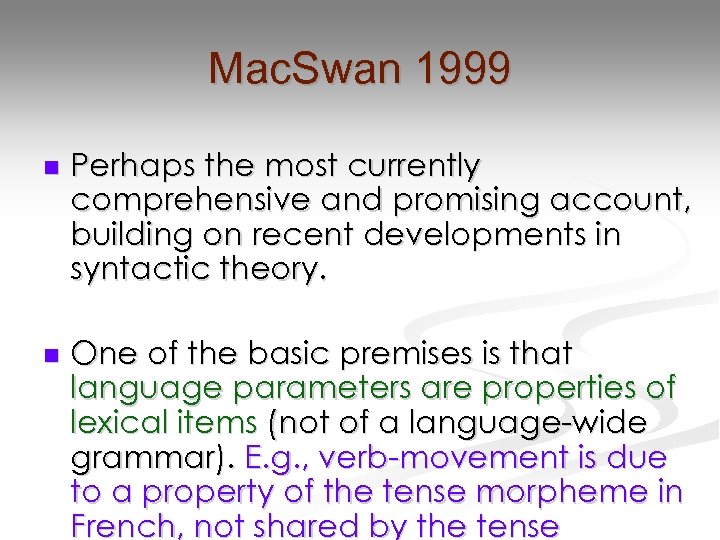

Mac. Swan 1999 n Perhaps the most currently comprehensive and promising account, building on recent developments in syntactic theory. n One of the basic premises is that language parameters are properties of lexical items (not of a language-wide grammar). E. g. , verb-movement is due to a property of the tense morpheme in French, not shared by the tense

Mac. Swan 1999 n Perhaps the most currently comprehensive and promising account, building on recent developments in syntactic theory. n One of the basic premises is that language parameters are properties of lexical items (not of a language-wide grammar). E. g. , verb-movement is due to a property of the tense morpheme in French, not shared by the tense

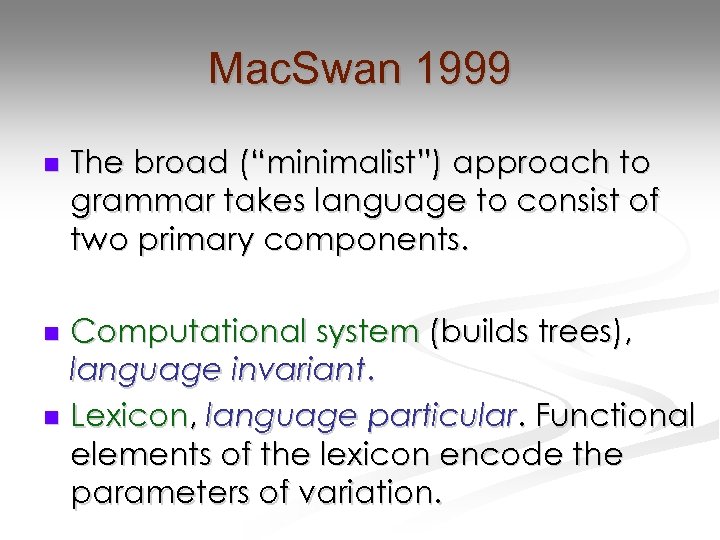

Mac. Swan 1999 n The broad (“minimalist”) approach to grammar takes language to consist of two primary components. Computational system (builds trees), language invariant. n Lexicon, language particular. Functional elements of the lexicon encode the parameters of variation. n

Mac. Swan 1999 n The broad (“minimalist”) approach to grammar takes language to consist of two primary components. Computational system (builds trees), language invariant. n Lexicon, language particular. Functional elements of the lexicon encode the parameters of variation. n

Mac. Swan 1999 n Mac. Swan’s proposal is that there are no constraints on code mixing over and above constraints found on monolingual sentences. n n (His only constraint which obliquely refers to code mixing is the one we turn to next, roughly that within a word, the language must be coherent. ) We can determine what are possible mixes by looking at the properties of the (functional elements) of the lexicons of the two mixed languages.

Mac. Swan 1999 n Mac. Swan’s proposal is that there are no constraints on code mixing over and above constraints found on monolingual sentences. n n (His only constraint which obliquely refers to code mixing is the one we turn to next, roughly that within a word, the language must be coherent. ) We can determine what are possible mixes by looking at the properties of the (functional elements) of the lexicons of the two mixed languages.

Mac. Swan 1999 n The model of code mixing is then just like monolingual speech—the only difference being that the words and functional elements are not always drawn from the lexicon belonging to a single language. n Where requirements conflict between languages is where mixing will be prohibited.

Mac. Swan 1999 n The model of code mixing is then just like monolingual speech—the only difference being that the words and functional elements are not always drawn from the lexicon belonging to a single language. n Where requirements conflict between languages is where mixing will be prohibited.

Clitics, bound morphemes Some lexical items in some languages are clitics, they depend (usually phonologically) on neighboring words. Similar to the concept of bound morpheme. n John’s book. n I shouldn’t go. n n Clitics essentially fuse with their host.

Clitics, bound morphemes Some lexical items in some languages are clitics, they depend (usually phonologically) on neighboring words. Similar to the concept of bound morpheme. n John’s book. n I shouldn’t go. n n Clitics essentially fuse with their host.

Clitics, bound morphemes n Clitics generally cannot be stressed. *John’S book n *I could. N’T go. n n Clitics generally form an inseparable unit with their host. Shouldn’t I go? n Should I not go? n *Should I n’t go? n

Clitics, bound morphemes n Clitics generally cannot be stressed. *John’S book n *I could. N’T go. n n Clitics generally form an inseparable unit with their host. Shouldn’t I go? n Should I not go? n *Should I n’t go? n

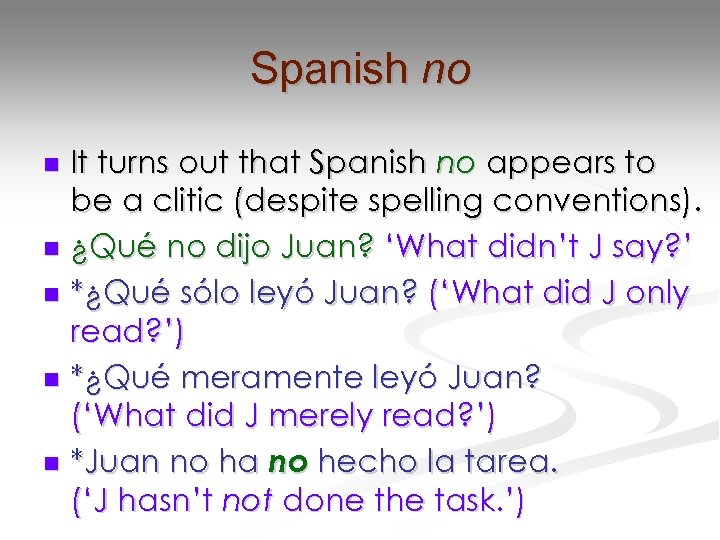

Spanish no It turns out that Spanish no appears to be a clitic (despite spelling conventions). n ¿Qué no dijo Juan? ‘What didn’t J say? ’ n *¿Qué sólo leyó Juan? (‘What did J only read? ’) n *¿Qué meramente leyó Juan? (‘What did J merely read? ’) n *Juan no ha no hecho la tarea. (‘J hasn’t not done the task. ’) n

Spanish no It turns out that Spanish no appears to be a clitic (despite spelling conventions). n ¿Qué no dijo Juan? ‘What didn’t J say? ’ n *¿Qué sólo leyó Juan? (‘What did J only read? ’) n *¿Qué meramente leyó Juan? (‘What did J merely read? ’) n *Juan no ha no hecho la tarea. (‘J hasn’t not done the task. ’) n

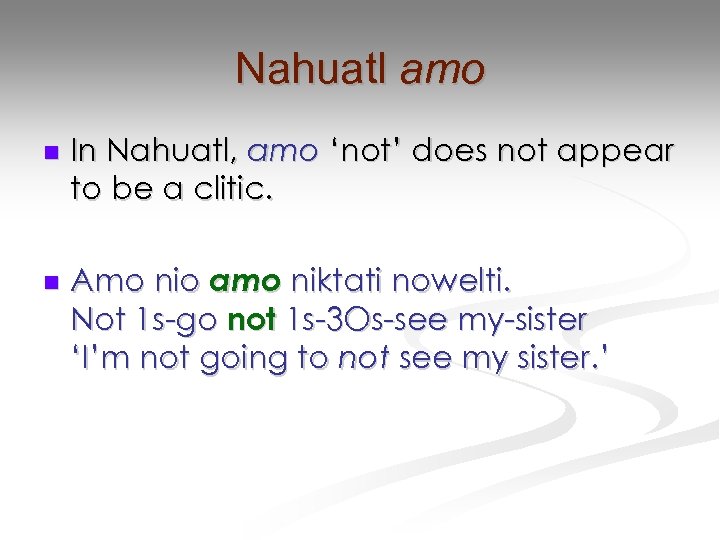

Nahuatl amo n n In Nahuatl, amo ‘not’ does not appear to be a clitic. Amo nio amo niktati nowelti. Not 1 s-go not 1 s-3 Os-see my-sister ‘I’m not going to not see my sister. ’

Nahuatl amo n n In Nahuatl, amo ‘not’ does not appear to be a clitic. Amo nio amo niktati nowelti. Not 1 s-go not 1 s-3 Os-see my-sister ‘I’m not going to not see my sister. ’

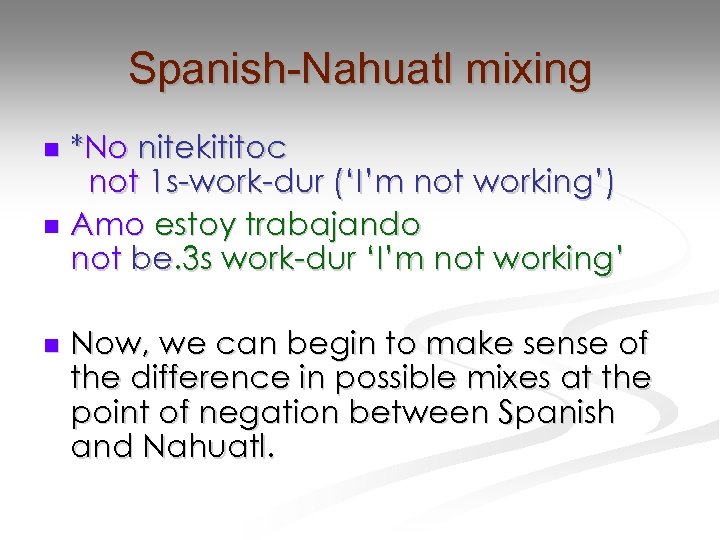

Spanish-Nahuatl mixing *No nitekititoc not 1 s-work-dur (‘I’m not working’) n Amo estoy trabajando not be. 3 s work-dur ‘I’m not working’ n n Now, we can begin to make sense of the difference in possible mixes at the point of negation between Spanish and Nahuatl.

Spanish-Nahuatl mixing *No nitekititoc not 1 s-work-dur (‘I’m not working’) n Amo estoy trabajando not be. 3 s work-dur ‘I’m not working’ n n Now, we can begin to make sense of the difference in possible mixes at the point of negation between Spanish and Nahuatl.

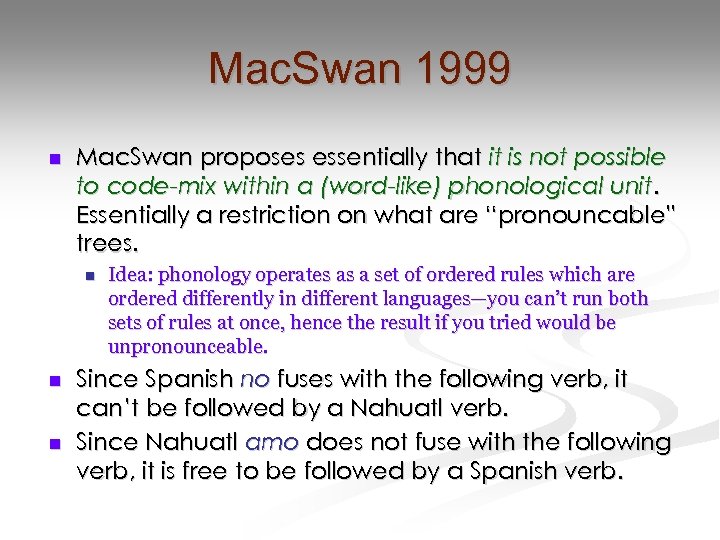

Mac. Swan 1999 n Mac. Swan proposes essentially that it is not possible to code-mix within a (word-like) phonological unit. Essentially a restriction on what are “pronouncable” trees. n n n Idea: phonology operates as a set of ordered rules which are ordered differently in different languages—you can’t run both sets of rules at once, hence the result if you tried would be unpronounceable. Since Spanish no fuses with the following verb, it can’t be followed by a Nahuatl verb. Since Nahuatl amo does not fuse with the following verb, it is free to be followed by a Spanish verb.

Mac. Swan 1999 n Mac. Swan proposes essentially that it is not possible to code-mix within a (word-like) phonological unit. Essentially a restriction on what are “pronouncable” trees. n n n Idea: phonology operates as a set of ordered rules which are ordered differently in different languages—you can’t run both sets of rules at once, hence the result if you tried would be unpronounceable. Since Spanish no fuses with the following verb, it can’t be followed by a Nahuatl verb. Since Nahuatl amo does not fuse with the following verb, it is free to be followed by a Spanish verb.

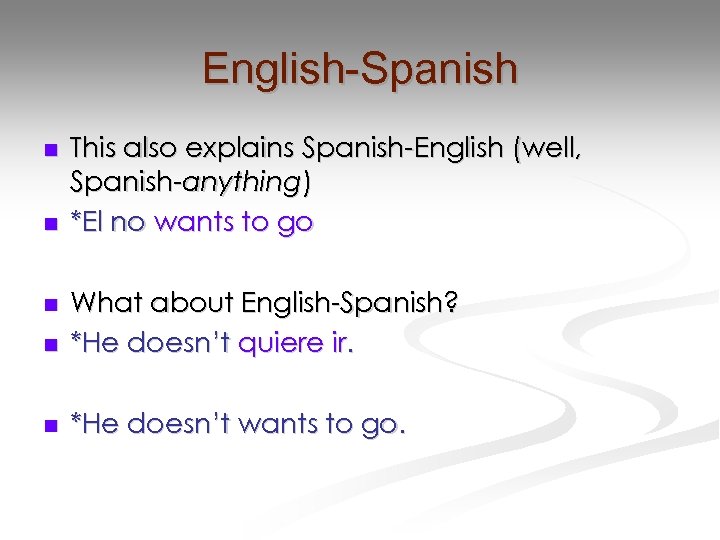

English-Spanish n n This also explains Spanish-English (well, Spanish-anything) *El no wants to go n What about English-Spanish? *He doesn’t quiere ir. n *He doesn’t wants to go. n

English-Spanish n n This also explains Spanish-English (well, Spanish-anything) *El no wants to go n What about English-Spanish? *He doesn’t quiere ir. n *He doesn’t wants to go. n

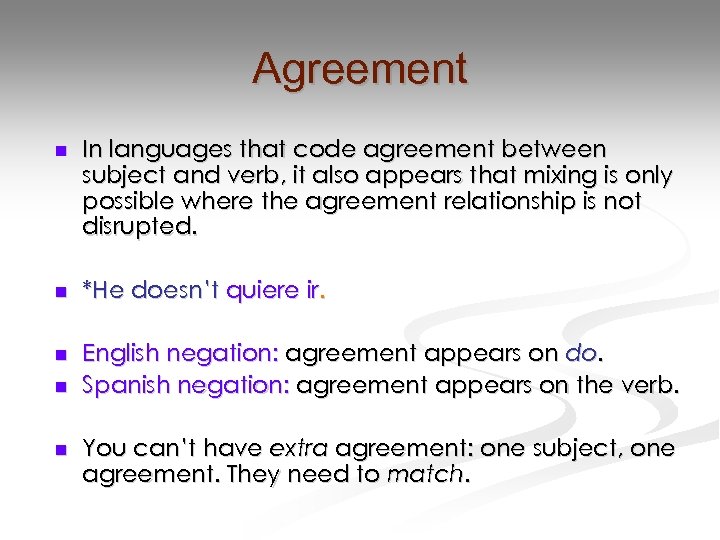

Agreement n In languages that code agreement between subject and verb, it also appears that mixing is only possible where the agreement relationship is not disrupted. n *He doesn’t quiere ir. n English negation: agreement appears on do. Spanish negation: agreement appears on the verb. n n You can’t have extra agreement: one subject, one agreement. They need to match.

Agreement n In languages that code agreement between subject and verb, it also appears that mixing is only possible where the agreement relationship is not disrupted. n *He doesn’t quiere ir. n English negation: agreement appears on do. Spanish negation: agreement appears on the verb. n n You can’t have extra agreement: one subject, one agreement. They need to match.

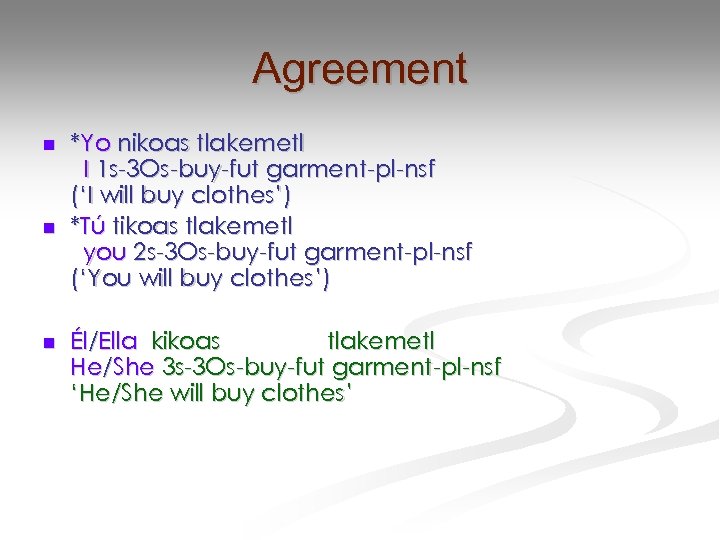

Agreement n n n *Yo nikoas tlakemetl I 1 s-3 Os-buy-fut garment-pl-nsf (‘I will buy clothes’) *Tú tikoas tlakemetl you 2 s-3 Os-buy-fut garment-pl-nsf (‘You will buy clothes’) Él/Ella kikoas tlakemetl He/She 3 s-3 Os-buy-fut garment-pl-nsf ‘He/She will buy clothes’

Agreement n n n *Yo nikoas tlakemetl I 1 s-3 Os-buy-fut garment-pl-nsf (‘I will buy clothes’) *Tú tikoas tlakemetl you 2 s-3 Os-buy-fut garment-pl-nsf (‘You will buy clothes’) Él/Ella kikoas tlakemetl He/She 3 s-3 Os-buy-fut garment-pl-nsf ‘He/She will buy clothes’

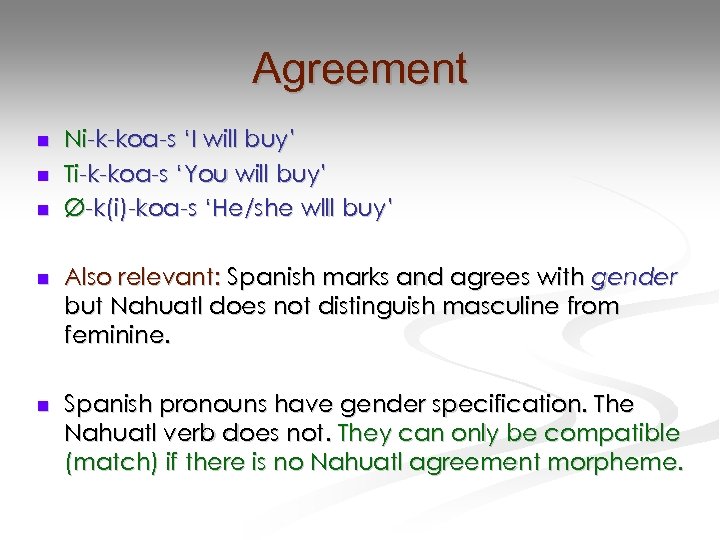

Agreement n n n Ni-k-koa-s ‘I will buy’ Ti-k-koa-s ‘You will buy’ Ø-k(i)-koa-s ‘He/she wlll buy’ n Also relevant: Spanish marks and agrees with gender but Nahuatl does not distinguish masculine from feminine. n Spanish pronouns have gender specification. The Nahuatl verb does not. They can only be compatible (match) if there is no Nahuatl agreement morpheme.

Agreement n n n Ni-k-koa-s ‘I will buy’ Ti-k-koa-s ‘You will buy’ Ø-k(i)-koa-s ‘He/she wlll buy’ n Also relevant: Spanish marks and agrees with gender but Nahuatl does not distinguish masculine from feminine. n Spanish pronouns have gender specification. The Nahuatl verb does not. They can only be compatible (match) if there is no Nahuatl agreement morpheme.

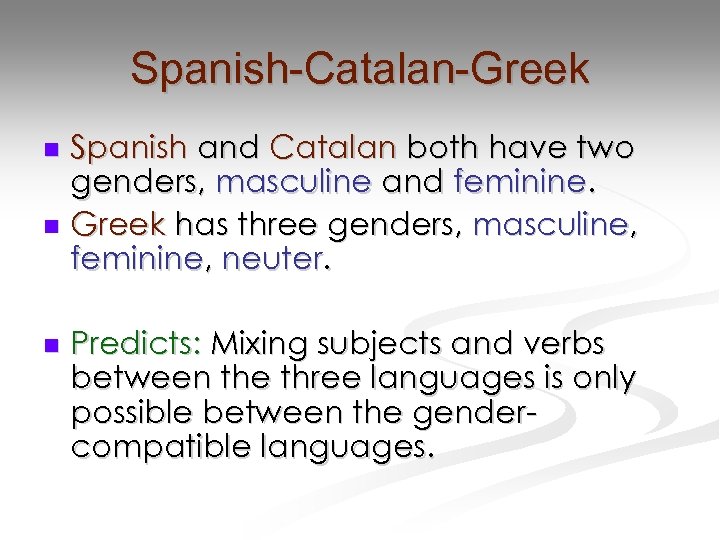

Spanish-Catalan-Greek Spanish and Catalan both have two genders, masculine and feminine. n Greek has three genders, masculine, feminine, neuter. n n Predicts: Mixing subjects and verbs between the three languages is only possible between the gendercompatible languages.

Spanish-Catalan-Greek Spanish and Catalan both have two genders, masculine and feminine. n Greek has three genders, masculine, feminine, neuter. n n Predicts: Mixing subjects and verbs between the three languages is only possible between the gendercompatible languages.

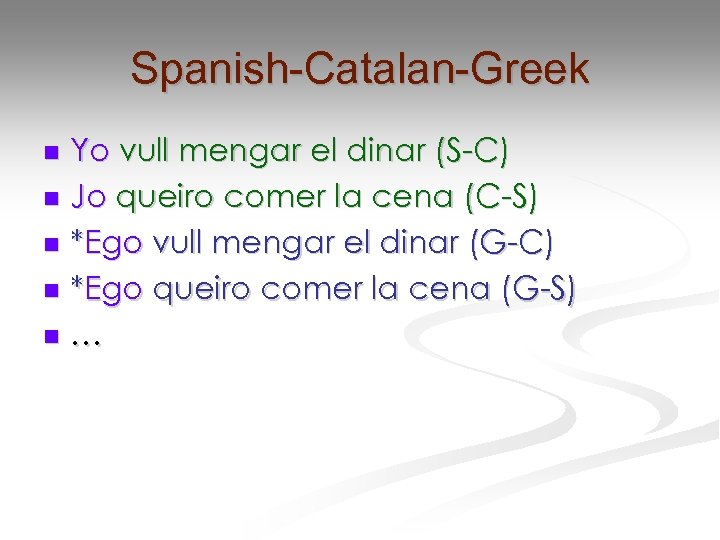

Spanish-Catalan-Greek Yo vull mengar el dinar (S-C) n Jo queiro comer la cena (C-S) n *Ego vull mengar el dinar (G-C) n *Ego queiro comer la cena (G-S) n … n

Spanish-Catalan-Greek Yo vull mengar el dinar (S-C) n Jo queiro comer la cena (C-S) n *Ego vull mengar el dinar (G-C) n *Ego queiro comer la cena (G-S) n … n

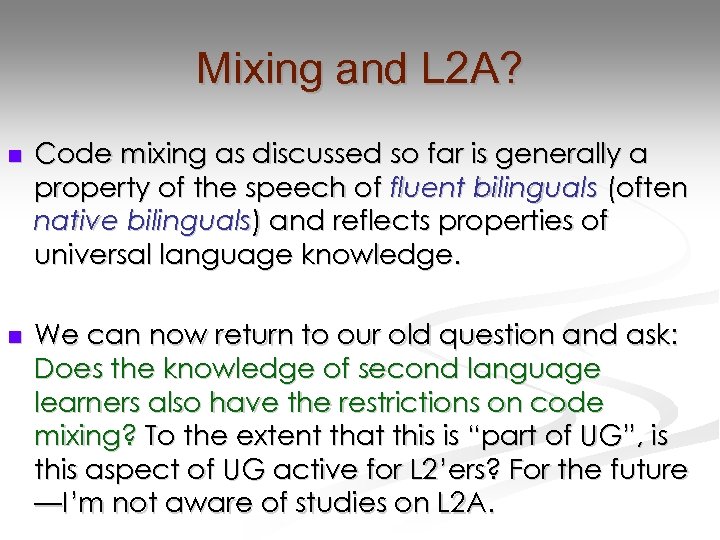

Mixing and L 2 A? n Code mixing as discussed so far is generally a property of the speech of fluent bilinguals (often native bilinguals) and reflects properties of universal language knowledge. n We can now return to our old question and ask: Does the knowledge of second language learners also have the restrictions on code mixing? To the extent that this is “part of UG”, is this aspect of UG active for L 2’ers? For the future —I’m not aware of studies on L 2 A.

Mixing and L 2 A? n Code mixing as discussed so far is generally a property of the speech of fluent bilinguals (often native bilinguals) and reflects properties of universal language knowledge. n We can now return to our old question and ask: Does the knowledge of second language learners also have the restrictions on code mixing? To the extent that this is “part of UG”, is this aspect of UG active for L 2’ers? For the future —I’m not aware of studies on L 2 A.