547bbabcf705468c4a92e5802b4490cb.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 128

GRS LX 700 Language Acquisition and Linguistic Theory Week 7. Transfer and the “initial state” for L 2 A. And other things.

GRS LX 700 Language Acquisition and Linguistic Theory Week 7. Transfer and the “initial state” for L 2 A. And other things.

“UG in L 2 A” so far n UG principles n n UG parameters of variation n n (Subjacency, Binding Theory) (Subjacency bounding nodes, Binding domains, null subject, V T) Justified in large part on the basis of L 1. n n n the complexity of language the paucity of useful data the uniform success and speed of L 1’ers acquiring language.

“UG in L 2 A” so far n UG principles n n UG parameters of variation n n (Subjacency, Binding Theory) (Subjacency bounding nodes, Binding domains, null subject, V T) Justified in large part on the basis of L 1. n n n the complexity of language the paucity of useful data the uniform success and speed of L 1’ers acquiring language.

“UG in L 2 A” so far n n To what extent is UG still involved in L 2 A? Speaker’s “interlanguage” shows a lot of systematicity, complexity which also seems to be more than the linguistic input could motivate. The question then: Is this systematicity “left over” (transferred) from the existing L 1, where we know the systematicity exists already? Or is L 2 A also building up a new system like L 1 A? We’ve seen that universal principles which operated in L 1 seem to still operate in L 2 (e. g. , ECP and Japanese case markers).

“UG in L 2 A” so far n n To what extent is UG still involved in L 2 A? Speaker’s “interlanguage” shows a lot of systematicity, complexity which also seems to be more than the linguistic input could motivate. The question then: Is this systematicity “left over” (transferred) from the existing L 1, where we know the systematicity exists already? Or is L 2 A also building up a new system like L 1 A? We’ve seen that universal principles which operated in L 1 seem to still operate in L 2 (e. g. , ECP and Japanese case markers).

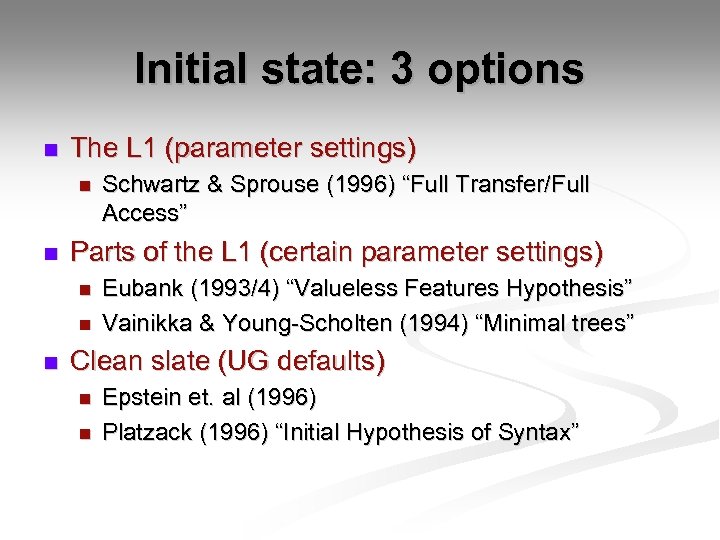

Initial state: 3 options n The L 1 (parameter settings) n n Parts of the L 1 (certain parameter settings) n n n Schwartz & Sprouse (1996) “Full Transfer/Full Access” Eubank (1993/4) “Valueless Features Hypothesis” Vainikka & Young-Scholten (1994) “Minimal trees” Clean slate (UG defaults) n n Epstein et. al (1996) Platzack (1996) “Initial Hypothesis of Syntax”

Initial state: 3 options n The L 1 (parameter settings) n n Parts of the L 1 (certain parameter settings) n n n Schwartz & Sprouse (1996) “Full Transfer/Full Access” Eubank (1993/4) “Valueless Features Hypothesis” Vainikka & Young-Scholten (1994) “Minimal trees” Clean slate (UG defaults) n n Epstein et. al (1996) Platzack (1996) “Initial Hypothesis of Syntax”

Vainikka & Young-Scholten n V&YS propose that phrase structure is built up from just a VP all the way up to a full clause. n Similar to Radford’s L 1 proposal except that there is an order of acquisition even past the VP (i. e. , IP before CP). Also similar to Rizzi’s L 1 “truncation” proposal. And of course, basically the same as Vainikka’s L 1 tree building proposal. n V&YS propose that both L 1 A and L 2 A involve this sort of “tree building. ”

Vainikka & Young-Scholten n V&YS propose that phrase structure is built up from just a VP all the way up to a full clause. n Similar to Radford’s L 1 proposal except that there is an order of acquisition even past the VP (i. e. , IP before CP). Also similar to Rizzi’s L 1 “truncation” proposal. And of course, basically the same as Vainikka’s L 1 tree building proposal. n V&YS propose that both L 1 A and L 2 A involve this sort of “tree building. ”

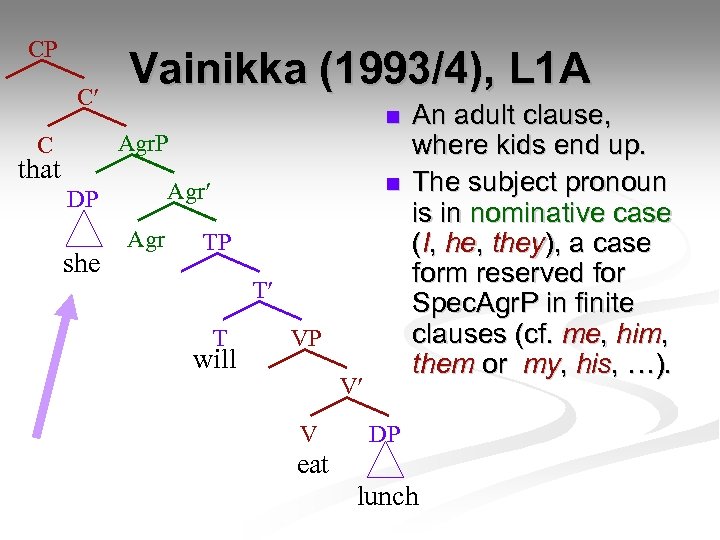

CP C Vainikka (1993/4), L 1 A n Agr. P C that DP she n Agr TP T T will VP V V An adult clause, where kids end up. The subject pronoun is in nominative case (I, he, they), a case form reserved for Spec. Agr. P in finite clauses (cf. me, him, them or my, his, …). DP eat lunch

CP C Vainikka (1993/4), L 1 A n Agr. P C that DP she n Agr TP T T will VP V V An adult clause, where kids end up. The subject pronoun is in nominative case (I, he, they), a case form reserved for Spec. Agr. P in finite clauses (cf. me, him, them or my, his, …). DP eat lunch

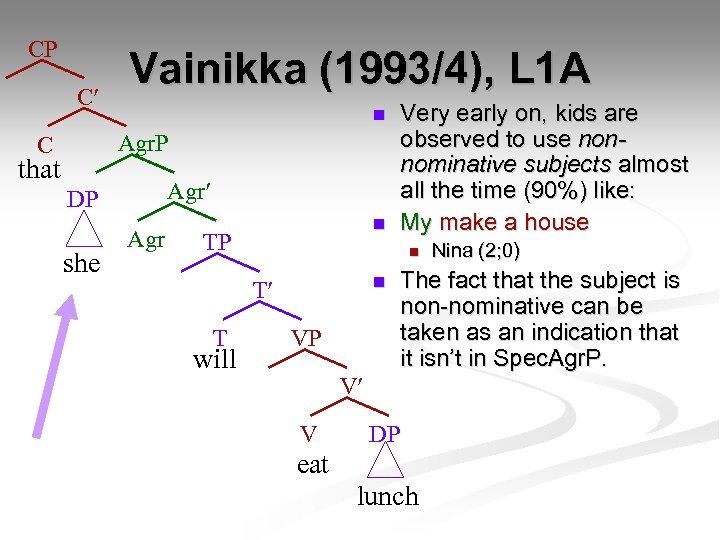

CP C Vainikka (1993/4), L 1 A n Agr. P C that Agr DP she Agr n TP n n T T will Very early on, kids are observed to use nonnominative subjects almost all the time (90%) like: My make a house VP The fact that the subject is non-nominative can be taken as an indication that it isn’t in Spec. Agr. P. V V Nina (2; 0) DP eat lunch

CP C Vainikka (1993/4), L 1 A n Agr. P C that Agr DP she Agr n TP n n T T will Very early on, kids are observed to use nonnominative subjects almost all the time (90%) like: My make a house VP The fact that the subject is non-nominative can be taken as an indication that it isn’t in Spec. Agr. P. V V Nina (2; 0) DP eat lunch

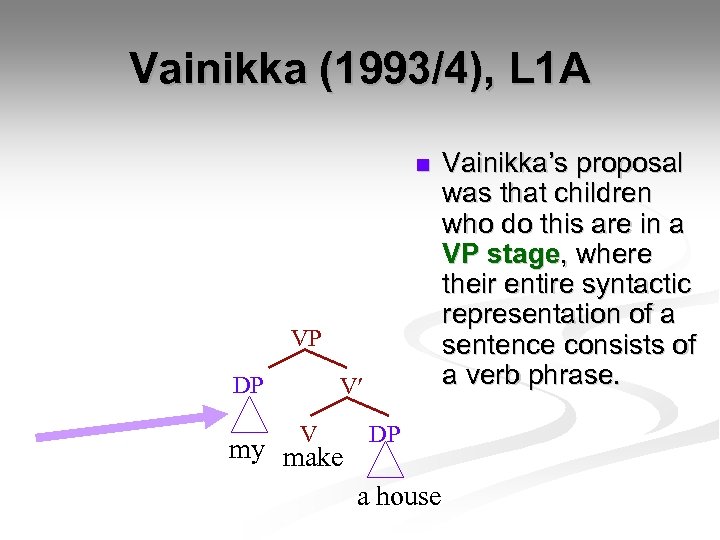

Vainikka (1993/4), L 1 A n VP DP V V my make DP a house Vainikka’s proposal was that children who do this are in a VP stage, where their entire syntactic representation of a sentence consists of a verb phrase.

Vainikka (1993/4), L 1 A n VP DP V V my make DP a house Vainikka’s proposal was that children who do this are in a VP stage, where their entire syntactic representation of a sentence consists of a verb phrase.

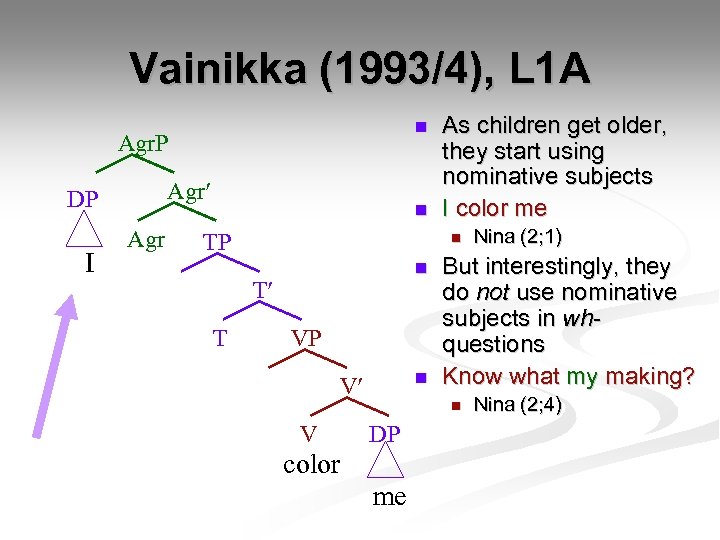

Vainikka (1993/4), L 1 A n Agr. P Agr DP I Agr n TP n n T T As children get older, they start using nominative subjects I color me VP n V V But interestingly, they do not use nominative subjects in whquestions Know what my making? n DP color me Nina (2; 1) Nina (2; 4)

Vainikka (1993/4), L 1 A n Agr. P Agr DP I Agr n TP n n T T As children get older, they start using nominative subjects I color me VP n V V But interestingly, they do not use nominative subjects in whquestions Know what my making? n DP color me Nina (2; 1) Nina (2; 4)

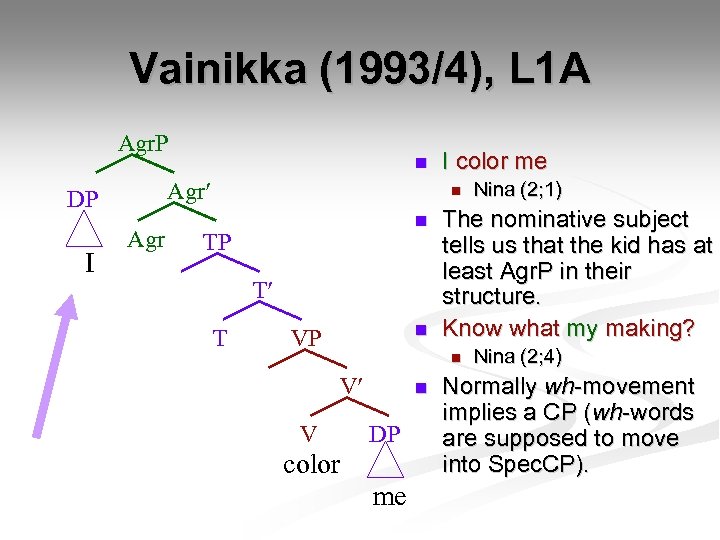

Vainikka (1993/4), L 1 A Agr. P Agr DP I n Agr I color me n n TP T T n VP The nominative subject tells us that the kid has at least Agr. P in their structure. Know what my making? n V V n DP color me Nina (2; 1) Nina (2; 4) Normally wh-movement implies a CP (wh-words are supposed to move into Spec. CP).

Vainikka (1993/4), L 1 A Agr. P Agr DP I n Agr I color me n n TP T T n VP The nominative subject tells us that the kid has at least Agr. P in their structure. Know what my making? n V V n DP color me Nina (2; 1) Nina (2; 4) Normally wh-movement implies a CP (wh-words are supposed to move into Spec. CP).

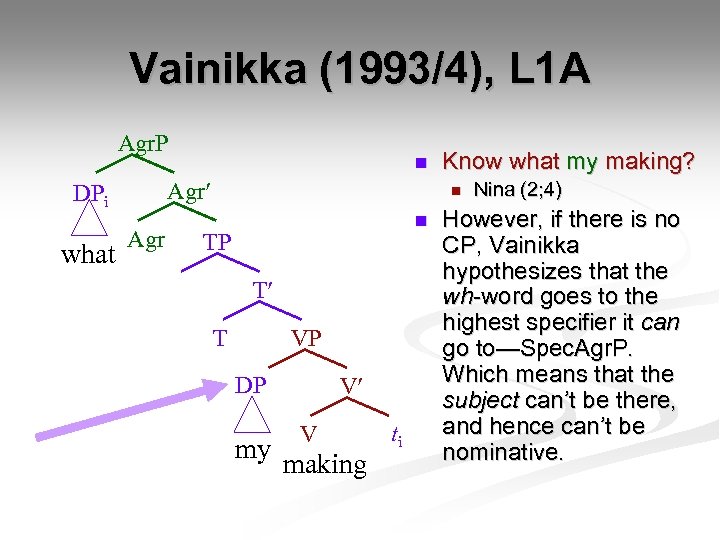

Vainikka (1993/4), L 1 A Agr. P Agr DPi what n Agr Know what my making? n n TP T T VP DP my V V making ti Nina (2; 4) However, if there is no CP, Vainikka hypothesizes that the wh-word goes to the highest specifier it can go to—Spec. Agr. P. Which means that the subject can’t be there, and hence can’t be nominative.

Vainikka (1993/4), L 1 A Agr. P Agr DPi what n Agr Know what my making? n n TP T T VP DP my V V making ti Nina (2; 4) However, if there is no CP, Vainikka hypothesizes that the wh-word goes to the highest specifier it can go to—Spec. Agr. P. Which means that the subject can’t be there, and hence can’t be nominative.

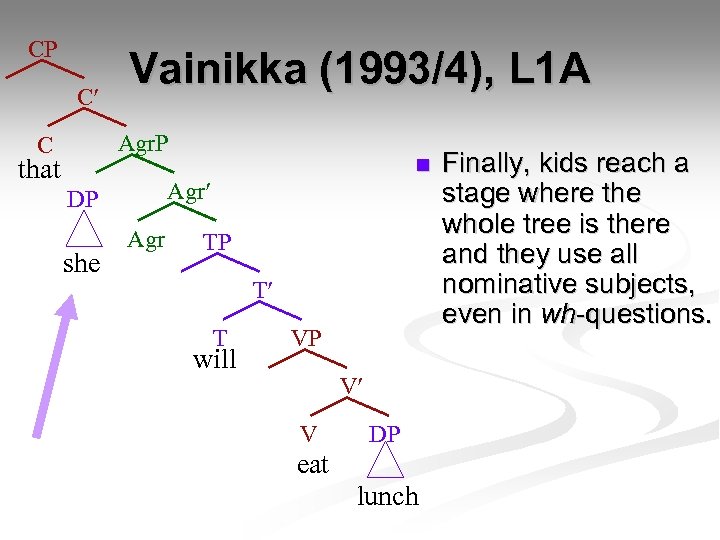

CP C Vainikka (1993/4), L 1 A Agr. P C that Agr DP she n Agr TP T T will VP V V DP eat lunch Finally, kids reach a stage where the whole tree is there and they use all nominative subjects, even in wh-questions.

CP C Vainikka (1993/4), L 1 A Agr. P C that Agr DP she n Agr TP T T will VP V V DP eat lunch Finally, kids reach a stage where the whole tree is there and they use all nominative subjects, even in wh-questions.

Vainikka (1993/4) n So, to summarize the L 1 A proposal: Acquisition goes in (syntactically identifiable stages). Those stages correspond to ever-greater articulation of the tree. n VP stage: n n Agr. P stage: n n No nominative subjects, no wh-questions. Nominative subjects except in wh-questions. CP stage: n Nominative subjects and wh-questions.

Vainikka (1993/4) n So, to summarize the L 1 A proposal: Acquisition goes in (syntactically identifiable stages). Those stages correspond to ever-greater articulation of the tree. n VP stage: n n Agr. P stage: n n No nominative subjects, no wh-questions. Nominative subjects except in wh-questions. CP stage: n Nominative subjects and wh-questions.

Vainikka & Young-Scholten’s primary claims about L 2 A Vainikka & Young-Scholten take this idea and propose that it also characterizes L 2 A… That is… n L 2 A takes place in stages, grammars which successively replace each other (perhaps after a period of competition). n The stages correspond to the “height” of the clausal structure. n

Vainikka & Young-Scholten’s primary claims about L 2 A Vainikka & Young-Scholten take this idea and propose that it also characterizes L 2 A… That is… n L 2 A takes place in stages, grammars which successively replace each other (perhaps after a period of competition). n The stages correspond to the “height” of the clausal structure. n

Vainikka & Young-Scholten n V&YS claim that L 2 phrase structure initially has no functional projections, and so as a consequence the only information that can be transferred from L 1 at the initial state is that information associated with lexical categories (specifically, headedness). No parameters tied to functional projections (e. g. , V->T) are transferred.

Vainikka & Young-Scholten n V&YS claim that L 2 phrase structure initially has no functional projections, and so as a consequence the only information that can be transferred from L 1 at the initial state is that information associated with lexical categories (specifically, headedness). No parameters tied to functional projections (e. g. , V->T) are transferred.

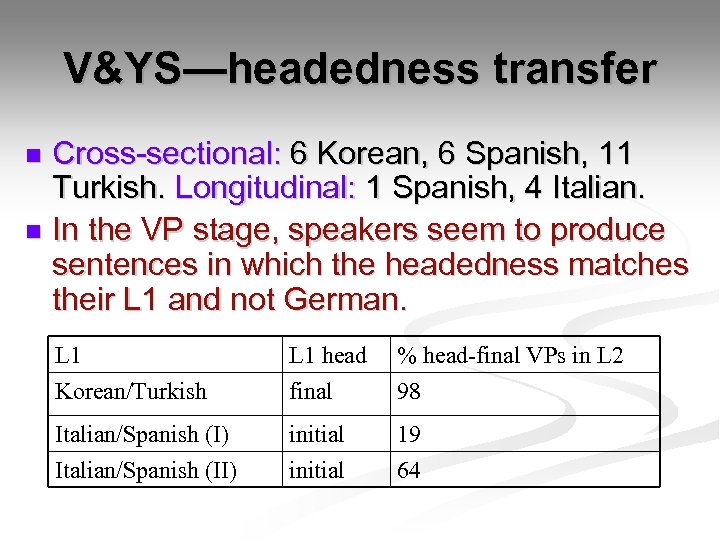

V&YS—headedness transfer Cross-sectional: 6 Korean, 6 Spanish, 11 Turkish. Longitudinal: 1 Spanish, 4 Italian. n In the VP stage, speakers seem to produce sentences in which the headedness matches their L 1 and not German. n L 1 Korean/Turkish L 1 head final % head-final VPs in L 2 98 Italian/Spanish (I) Italian/Spanish (II) initial 19 64

V&YS—headedness transfer Cross-sectional: 6 Korean, 6 Spanish, 11 Turkish. Longitudinal: 1 Spanish, 4 Italian. n In the VP stage, speakers seem to produce sentences in which the headedness matches their L 1 and not German. n L 1 Korean/Turkish L 1 head final % head-final VPs in L 2 98 Italian/Spanish (I) Italian/Spanish (II) initial 19 64

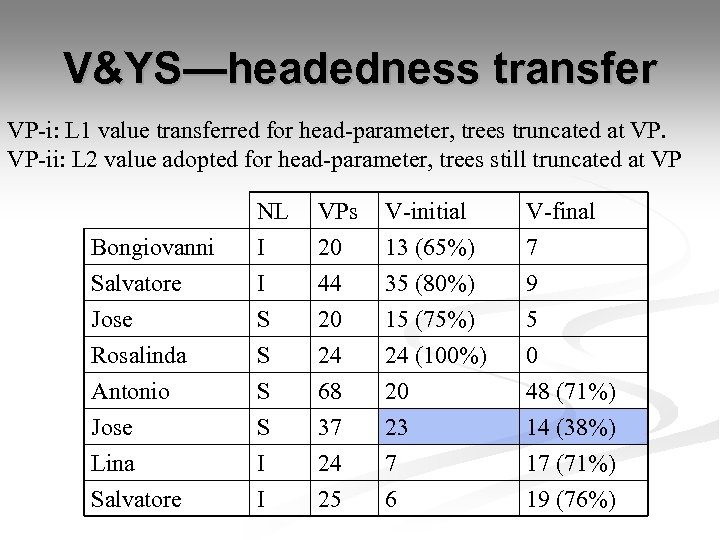

V&YS—headedness transfer VP-i: L 1 value transferred for head-parameter, trees truncated at VP. VP-ii: L 2 value adopted for head-parameter, trees still truncated at VP Bongiovanni Salvatore Jose NL I I S VPs 20 44 20 V-initial 13 (65%) 35 (80%) 15 (75%) V-final 7 9 5 Rosalinda Antonio Jose Lina Salvatore S S S I I 24 68 37 24 25 24 (100%) 20 23 7 6 0 48 (71%) 14 (38%) 17 (71%) 19 (76%)

V&YS—headedness transfer VP-i: L 1 value transferred for head-parameter, trees truncated at VP. VP-ii: L 2 value adopted for head-parameter, trees still truncated at VP Bongiovanni Salvatore Jose NL I I S VPs 20 44 20 V-initial 13 (65%) 35 (80%) 15 (75%) V-final 7 9 5 Rosalinda Antonio Jose Lina Salvatore S S S I I 24 68 37 24 25 24 (100%) 20 23 7 6 0 48 (71%) 14 (38%) 17 (71%) 19 (76%)

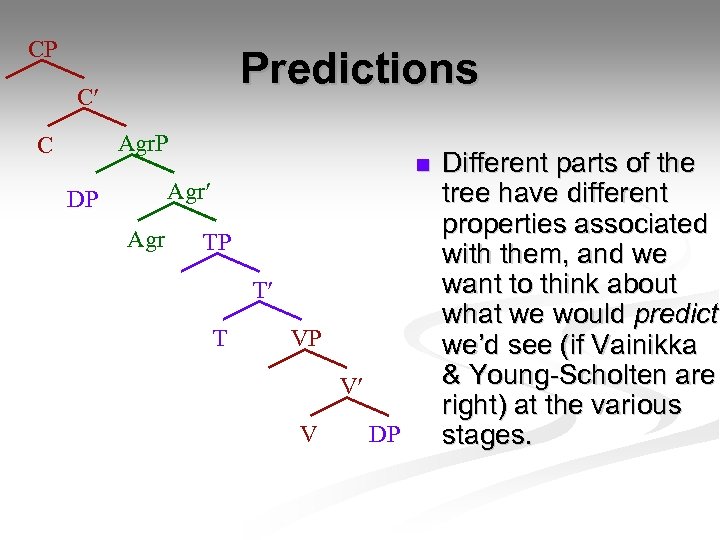

CP Predictions C Agr. P C n Agr DP Agr TP T T VP V V DP Different parts of the tree have different properties associated with them, and we want to think about what we would predict we’d see (if Vainikka & Young-Scholten are right) at the various stages.

CP Predictions C Agr. P C n Agr DP Agr TP T T VP V V DP Different parts of the tree have different properties associated with them, and we want to think about what we would predict we’d see (if Vainikka & Young-Scholten are right) at the various stages.

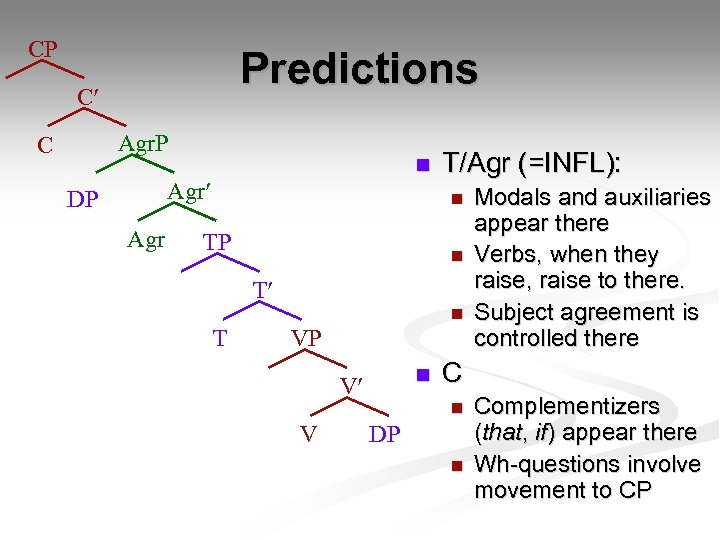

CP Predictions C Agr. P C n Agr DP Agr T/Agr (=INFL): n TP n T VP n V V Modals and auxiliaries appear there Verbs, when they raise, raise to there. Subject agreement is controlled there C n DP n Complementizers (that, if) appear there Wh-questions involve movement to CP

CP Predictions C Agr. P C n Agr DP Agr T/Agr (=INFL): n TP n T VP n V V Modals and auxiliaries appear there Verbs, when they raise, raise to there. Subject agreement is controlled there C n DP n Complementizers (that, if) appear there Wh-questions involve movement to CP

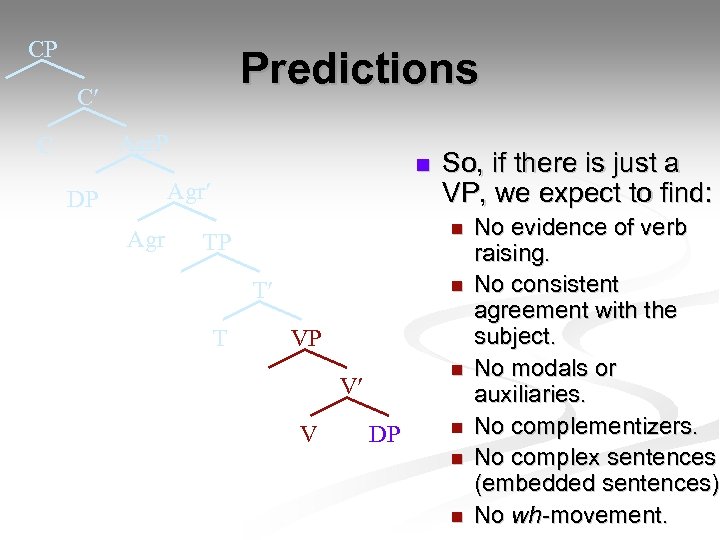

CP Predictions C Agr. P C n Agr DP Agr n TP T T So, if there is just a VP, we expect to find: n VP n V V DP n n n No evidence of verb raising. No consistent agreement with the subject. No modals or auxiliaries. No complementizers. No complex sentences (embedded sentences) No wh-movement.

CP Predictions C Agr. P C n Agr DP Agr n TP T T So, if there is just a VP, we expect to find: n VP n V V DP n n n No evidence of verb raising. No consistent agreement with the subject. No modals or auxiliaries. No complementizers. No complex sentences (embedded sentences) No wh-movement.

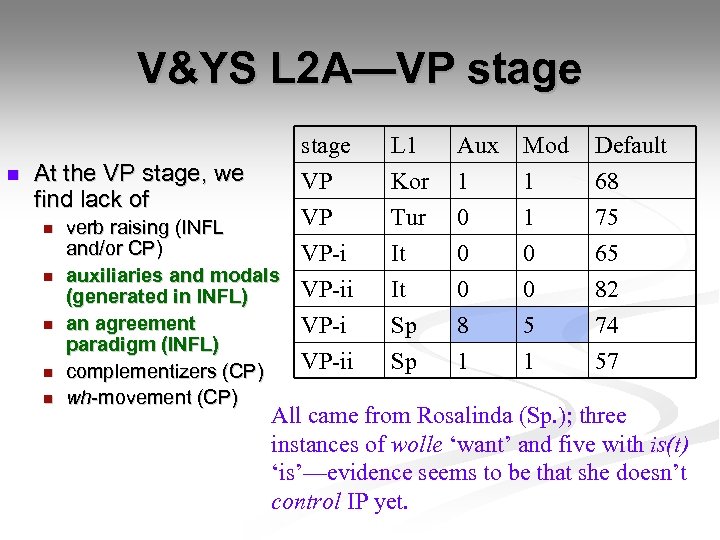

V&YS L 2 A—VP stage n stage At the VP stage, we VP find lack of VP n verb raising (INFL and/or CP) VP-i n auxiliaries and modals VP-ii (generated in INFL) n an agreement VP-i paradigm (INFL) VP-ii n complementizers (CP) n wh-movement (CP) L 1 Kor Tur It It Sp Sp Aux 1 0 0 0 8 1 Mod 1 1 0 0 5 1 Default 68 75 65 82 74 57 All came from Rosalinda (Sp. ); three instances of wolle ‘want’ and five with is(t) ‘is’—evidence seems to be that she doesn’t control IP yet.

V&YS L 2 A—VP stage n stage At the VP stage, we VP find lack of VP n verb raising (INFL and/or CP) VP-i n auxiliaries and modals VP-ii (generated in INFL) n an agreement VP-i paradigm (INFL) VP-ii n complementizers (CP) n wh-movement (CP) L 1 Kor Tur It It Sp Sp Aux 1 0 0 0 8 1 Mod 1 1 0 0 5 1 Default 68 75 65 82 74 57 All came from Rosalinda (Sp. ); three instances of wolle ‘want’ and five with is(t) ‘is’—evidence seems to be that she doesn’t control IP yet.

V&YS L 2 A—VP stage n At the VP stage, we find lack of n n n n verb raising (INFL and/or CP) auxiliaries and modals (generated in INFL) an agreement paradigm (INFL) complementizers (CP) wh-movement (CP) Antonio (Sp): 7 of 9 sentences with temporal adverbs show adverb–verb order (no raising); 9 of 10 with negation showed neg–verb order. Turkish/Korean (visible) verb-raising only 14%.

V&YS L 2 A—VP stage n At the VP stage, we find lack of n n n n verb raising (INFL and/or CP) auxiliaries and modals (generated in INFL) an agreement paradigm (INFL) complementizers (CP) wh-movement (CP) Antonio (Sp): 7 of 9 sentences with temporal adverbs show adverb–verb order (no raising); 9 of 10 with negation showed neg–verb order. Turkish/Korean (visible) verb-raising only 14%.

V&YS L 2 A—VP stage n At the VP stage, we find lack of n n n n verb raising (INFL and/or CP) auxiliaries and modals (generated in INFL) an agreement paradigm (INFL) complementizers (CP) wh-movement (CP) No embedded clauses with complementizers. No wh-questions with a fronted wh-phrase (at least, not that requires a CP analysis). No yes-no questions with a fronted verb.

V&YS L 2 A—VP stage n At the VP stage, we find lack of n n n n verb raising (INFL and/or CP) auxiliaries and modals (generated in INFL) an agreement paradigm (INFL) complementizers (CP) wh-movement (CP) No embedded clauses with complementizers. No wh-questions with a fronted wh-phrase (at least, not that requires a CP analysis). No yes-no questions with a fronted verb.

V&YS L 2 A—TP stage After the VP stage, L 2 learners move to a single functional projection, which appears to be TP. n Modals and auxiliaries can start there. n Verb raising can take place to there. n n n Note: the TL TP is head-final, however. Agreement seems still to be lacking (TP only, and not yet Agr. P is acquired).

V&YS L 2 A—TP stage After the VP stage, L 2 learners move to a single functional projection, which appears to be TP. n Modals and auxiliaries can start there. n Verb raising can take place to there. n n n Note: the TL TP is head-final, however. Agreement seems still to be lacking (TP only, and not yet Agr. P is acquired).

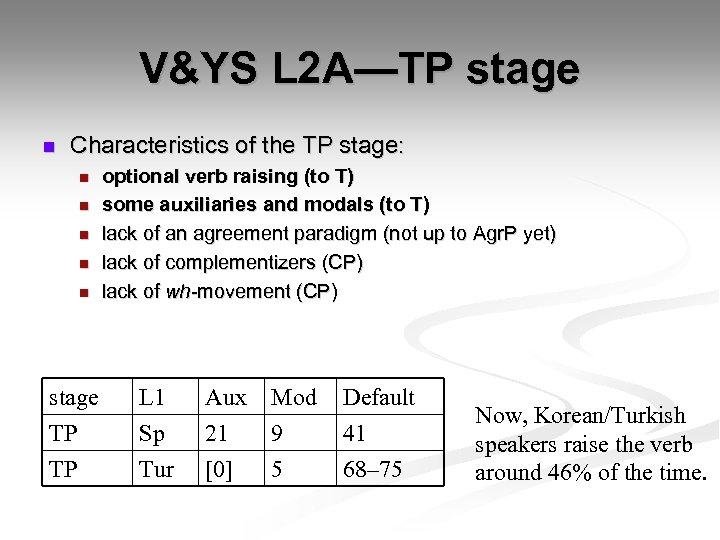

V&YS L 2 A—TP stage n Characteristics of the TP stage: n n n stage TP TP optional verb raising (to T) some auxiliaries and modals (to T) lack of an agreement paradigm (not up to Agr. P yet) lack of complementizers (CP) lack of wh-movement (CP) L 1 Sp Tur Aux 21 [0] Mod 9 5 Default 41 68– 75 Now, Korean/Turkish speakers raise the verb around 46% of the time.

V&YS L 2 A—TP stage n Characteristics of the TP stage: n n n stage TP TP optional verb raising (to T) some auxiliaries and modals (to T) lack of an agreement paradigm (not up to Agr. P yet) lack of complementizers (CP) lack of wh-movement (CP) L 1 Sp Tur Aux 21 [0] Mod 9 5 Default 41 68– 75 Now, Korean/Turkish speakers raise the verb around 46% of the time.

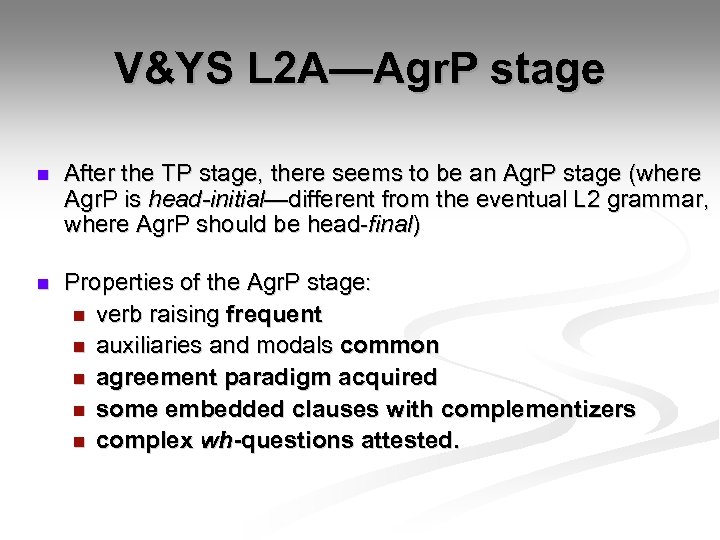

V&YS L 2 A—Agr. P stage n After the TP stage, there seems to be an Agr. P stage (where Agr. P is head-initial—different from the eventual L 2 grammar, where Agr. P should be head-final) n Properties of the Agr. P stage: n verb raising frequent n auxiliaries and modals common n agreement paradigm acquired n some embedded clauses with complementizers n complex wh-questions attested.

V&YS L 2 A—Agr. P stage n After the TP stage, there seems to be an Agr. P stage (where Agr. P is head-initial—different from the eventual L 2 grammar, where Agr. P should be head-final) n Properties of the Agr. P stage: n verb raising frequent n auxiliaries and modals common n agreement paradigm acquired n some embedded clauses with complementizers n complex wh-questions attested.

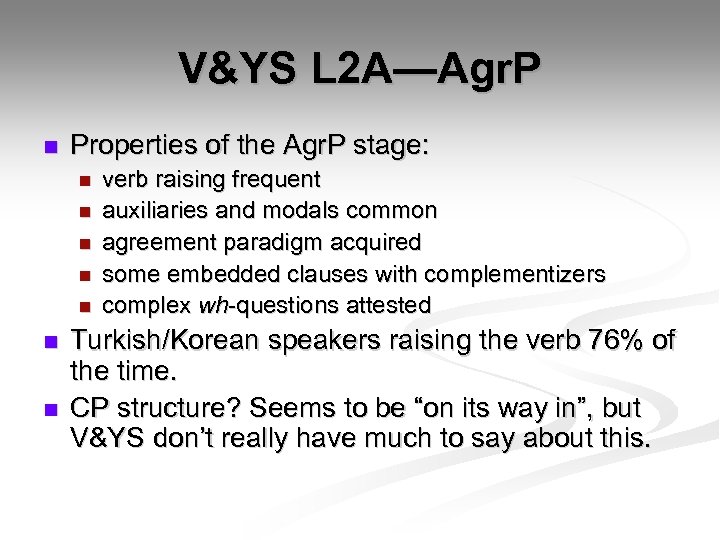

V&YS L 2 A—Agr. P n Properties of the Agr. P stage: n n n n verb raising frequent auxiliaries and modals common agreement paradigm acquired some embedded clauses with complementizers complex wh-questions attested Turkish/Korean speakers raising the verb 76% of the time. CP structure? Seems to be “on its way in”, but V&YS don’t really have much to say about this.

V&YS L 2 A—Agr. P n Properties of the Agr. P stage: n n n n verb raising frequent auxiliaries and modals common agreement paradigm acquired some embedded clauses with complementizers complex wh-questions attested Turkish/Korean speakers raising the verb 76% of the time. CP structure? Seems to be “on its way in”, but V&YS don’t really have much to say about this.

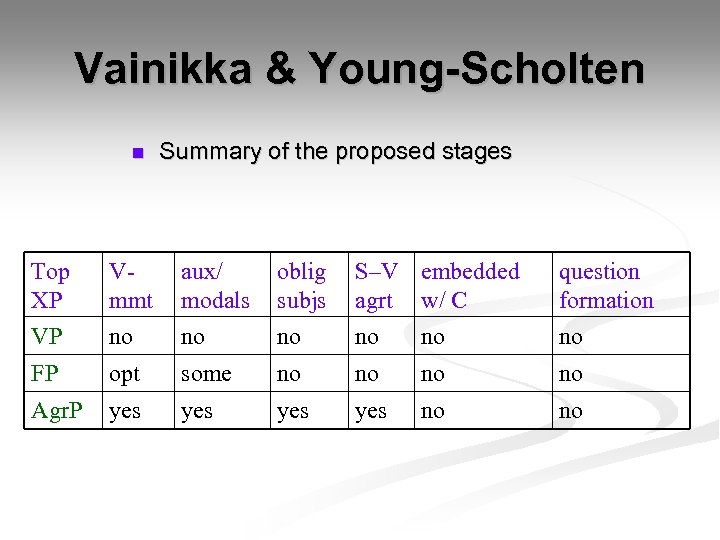

Vainikka & Young-Scholten n Summary of the proposed stages Top XP Vmmt aux/ modals oblig subjs S–V embedded agrt w/ C question formation VP no no no FP opt some no no Agr. P yes yes no no

Vainikka & Young-Scholten n Summary of the proposed stages Top XP Vmmt aux/ modals oblig subjs S–V embedded agrt w/ C question formation VP no no no FP opt some no no Agr. P yes yes no no

Stages n n So, L 2’ers go through VP, TP, Agr. P, (CP) stages… An important point about this is that this does not mean that a L 2 learner at a given point in time is necessarily in exactly one stage, producing exactly one kind of structure. n n n (My response on V&YS’s behalf to an objection raised by Epstein et al. 1996; V&YS’s endorsement should not be inferred. ) The way to think of this is that there is a progression of stages, but that adjacent stages often co-exist for a time— so, “between” the VP and TP stages, some utterances are VPs, some are TPs. This might be perhaps comparable to knowledge of register in one’s L 1, except that there is a definite progression.

Stages n n So, L 2’ers go through VP, TP, Agr. P, (CP) stages… An important point about this is that this does not mean that a L 2 learner at a given point in time is necessarily in exactly one stage, producing exactly one kind of structure. n n n (My response on V&YS’s behalf to an objection raised by Epstein et al. 1996; V&YS’s endorsement should not be inferred. ) The way to think of this is that there is a progression of stages, but that adjacent stages often co-exist for a time— so, “between” the VP and TP stages, some utterances are VPs, some are TPs. This might be perhaps comparable to knowledge of register in one’s L 1, except that there is a definite progression.

V&YS summary n n n So, Vainikka & Young-Scholten propose that L 2 A is acquired by “building up” the syntactic tree—that beginner L 2’ers have syntactic representations of their utterances which are lacking the functional projections which appear in the adult L 1’s representations, but that they gradually acquire the full structure. V&YS also propose that the information about the VP is borrowed wholesale from the L 1, that there is no stage prior to having just a VP. Lastly, V&YS consider this L 2 A to be just like L 1 A in course of acquisition (though they leave open the question of speed/success/etc. )

V&YS summary n n n So, Vainikka & Young-Scholten propose that L 2 A is acquired by “building up” the syntactic tree—that beginner L 2’ers have syntactic representations of their utterances which are lacking the functional projections which appear in the adult L 1’s representations, but that they gradually acquire the full structure. V&YS also propose that the information about the VP is borrowed wholesale from the L 1, that there is no stage prior to having just a VP. Lastly, V&YS consider this L 2 A to be just like L 1 A in course of acquisition (though they leave open the question of speed/success/etc. )

Problems with Minimal Trees n n White (2003) reviews a number of difficulties that the Minimal Trees account has. Data seems to be not very consistent. n n Evidence for DP and Neg. P from V&YS’s own data. E->F kids manage to get V left of pas (Grondin & White 1996) n n n but cf. Hawkins et al. next week. Also, these are kids who might have benefited from earlier exposure to French. V&YS also propose at one point that V->T is the default value. Some examples of early embedded clauses and SAI (evidence of CP) but V&YS’s criteria would also lead to the conclusion of no IP at the same point. (Gavruseva & Lardiere 1996).

Problems with Minimal Trees n n White (2003) reviews a number of difficulties that the Minimal Trees account has. Data seems to be not very consistent. n n Evidence for DP and Neg. P from V&YS’s own data. E->F kids manage to get V left of pas (Grondin & White 1996) n n n but cf. Hawkins et al. next week. Also, these are kids who might have benefited from earlier exposure to French. V&YS also propose at one point that V->T is the default value. Some examples of early embedded clauses and SAI (evidence of CP) but V&YS’s criteria would also lead to the conclusion of no IP at the same point. (Gavruseva & Lardiere 1996).

Problems with Minimal Trees n Criteria for stages are rather arbitrary. n n Is morphology really the best indicator of knowledge? n n V&YS count something as acquired if it appears more than 60% of the time. Why 60%? For kids, the arbitrary cutoff is often set at 90%. Prévost & White, discussed a couple of weeks hence, say “no”— better is to look at the properties like word order that the functional categories are supposed to be responsible for. To account for apparent V 2 without CP, V&YS need a weird German story in which TP/Agr. P starts out headinitial but is later returned to its proper head-final status.

Problems with Minimal Trees n Criteria for stages are rather arbitrary. n n Is morphology really the best indicator of knowledge? n n V&YS count something as acquired if it appears more than 60% of the time. Why 60%? For kids, the arbitrary cutoff is often set at 90%. Prévost & White, discussed a couple of weeks hence, say “no”— better is to look at the properties like word order that the functional categories are supposed to be responsible for. To account for apparent V 2 without CP, V&YS need a weird German story in which TP/Agr. P starts out headinitial but is later returned to its proper head-final status.

Paradis et al. (1998) n n n Paradis et al. (1998) looked at 15 English-speaking children in Québec, learning French (since kindergarten, interviewed at the end of grade one), and sought to look for evidence for (or against) this kind of “tree building” in their syntax. They looked at morphology to determine when the children “controlled” it (vs. producing a default) and whethere was a difference between the onset of tense and the onset of agreement. On one interpretation of V&YS, they predict that tense should be controlled before agreement, since TP is lower in the tree that Agr. P.

Paradis et al. (1998) n n n Paradis et al. (1998) looked at 15 English-speaking children in Québec, learning French (since kindergarten, interviewed at the end of grade one), and sought to look for evidence for (or against) this kind of “tree building” in their syntax. They looked at morphology to determine when the children “controlled” it (vs. producing a default) and whethere was a difference between the onset of tense and the onset of agreement. On one interpretation of V&YS, they predict that tense should be controlled before agreement, since TP is lower in the tree that Agr. P.

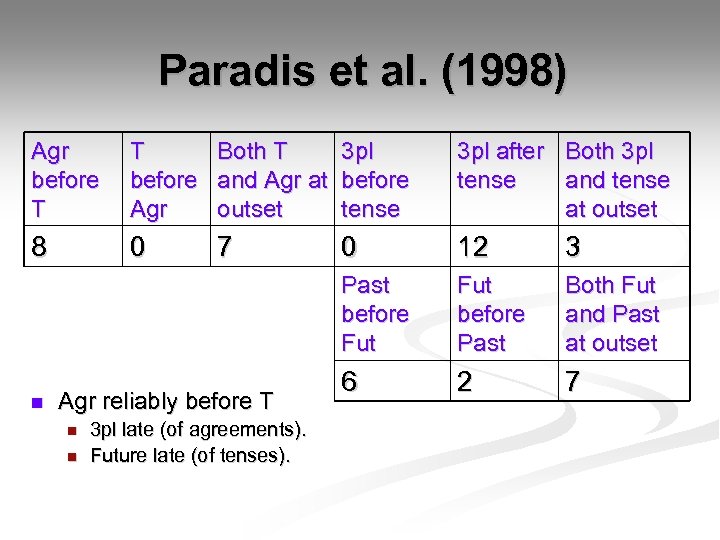

Paradis et al. (1998) Agr before T T before Agr Both T and Agr at outset 3 pl before tense 3 pl after Both 3 pl tense and tense at outset 8 0 7 0 12 3 Past before Fut before Past Both Fut and Past at outset 6 2 7 n Agr reliably before T n n 3 pl late (of agreements). Future late (of tenses).

Paradis et al. (1998) Agr before T T before Agr Both T and Agr at outset 3 pl before tense 3 pl after Both 3 pl tense and tense at outset 8 0 7 0 12 3 Past before Fut before Past Both Fut and Past at outset 6 2 7 n Agr reliably before T n n 3 pl late (of agreements). Future late (of tenses).

Paradis et al. (1998) n So, the interpretation of this information might be that: n (Child) L 2 A does seem to progress in stages. n This isn’t strictly compatible with the tree building approach, however, if TP is lower than Agr. P. It would require slight revisions to make this work out (not necessarily drastic revisions).

Paradis et al. (1998) n So, the interpretation of this information might be that: n (Child) L 2 A does seem to progress in stages. n This isn’t strictly compatible with the tree building approach, however, if TP is lower than Agr. P. It would require slight revisions to make this work out (not necessarily drastic revisions).

Eubank: Valueless Features Hypothesis n n n Another contender for the title of Theory of the Initial State is the “Valueless Features Hypothesis” of Eubank (1993/4). Like Minimal Trees, the VFH posits essentially that functional parameters are not initially set (not transferred from the L 1). Unlike Minimal Trees, the VFH does assume that the entire functional structure is there. But, e. g. , for V->T, the parameter/feature value that determines whether V moves to T is “undefined”.

Eubank: Valueless Features Hypothesis n n n Another contender for the title of Theory of the Initial State is the “Valueless Features Hypothesis” of Eubank (1993/4). Like Minimal Trees, the VFH posits essentially that functional parameters are not initially set (not transferred from the L 1). Unlike Minimal Trees, the VFH does assume that the entire functional structure is there. But, e. g. , for V->T, the parameter/feature value that determines whether V moves to T is “undefined”.

VFH n The interpretation of a “valueless” feature is the crucial point here. It’s not clear really what this should mean, but Eubank takes it to mean something like “not consistently on or off”. Hence, again using V->T as an example, the verb is predicted to sometimes raise (V->T on) and sometimes not (V->T off). E. g. , either is fine in L 2 English of: n n Pat eats often apples. Pat often eats apples.

VFH n The interpretation of a “valueless” feature is the crucial point here. It’s not clear really what this should mean, but Eubank takes it to mean something like “not consistently on or off”. Hence, again using V->T as an example, the verb is predicted to sometimes raise (V->T on) and sometimes not (V->T off). E. g. , either is fine in L 2 English of: n n Pat eats often apples. Pat often eats apples.

VFH and V->T n In fact (as we’ll discuss more carefully in a couple of weeks), White did a well-known series of experiments on F>L 2 E learners that did show that the learners accepted both. n n n Pat eats often apples. Pat often eats apples. Eubank takes this as evidence for VFH, but White (1992, 2003) notes that it’s unexpected for the VFH that they don’t also allow verb raising past negation. n n *Pat eats not apples. Pat does not eat apples.

VFH and V->T n In fact (as we’ll discuss more carefully in a couple of weeks), White did a well-known series of experiments on F>L 2 E learners that did show that the learners accepted both. n n n Pat eats often apples. Pat often eats apples. Eubank takes this as evidence for VFH, but White (1992, 2003) notes that it’s unexpected for the VFH that they don’t also allow verb raising past negation. n n *Pat eats not apples. Pat does not eat apples.

Yuan (2001) and {F, E}>L 2 C n Yuan (2001) looked at E>L 2 C and F>L 2 C learners’ responses to alternative verb-adverb orders in Chinese. L 1 Chinese allows only Adv-V order (no raising). n n Zhangsan chang kan dianshi. *Zhangsan kan chang dianshi. But neither group (and notably not even F>L 2 C) ever produced/accepted the V-Adv order. *VFH, but also possibly *FTFA (to be discussed soon). One further note: Yuan’s subjects were adults, White’s were children. This might have mattered.

Yuan (2001) and {F, E}>L 2 C n Yuan (2001) looked at E>L 2 C and F>L 2 C learners’ responses to alternative verb-adverb orders in Chinese. L 1 Chinese allows only Adv-V order (no raising). n n Zhangsan chang kan dianshi. *Zhangsan kan chang dianshi. But neither group (and notably not even F>L 2 C) ever produced/accepted the V-Adv order. *VFH, but also possibly *FTFA (to be discussed soon). One further note: Yuan’s subjects were adults, White’s were children. This might have mattered.

Eubank’s own experiments n Eubank & Grace (1998) tried an interesting methodology in an experiment to test for grammaticality of raised-verb structures in IL grammars. Something like a “lexical decision task” but with sentences (“are these the same or different? ”), recording the reaction time, and based on the finding that native speakers are slower to react to ungrammatical sentences.

Eubank’s own experiments n Eubank & Grace (1998) tried an interesting methodology in an experiment to test for grammaticality of raised-verb structures in IL grammars. Something like a “lexical decision task” but with sentences (“are these the same or different? ”), recording the reaction time, and based on the finding that native speakers are slower to react to ungrammatical sentences.

Eubank & Grace (1998) n n n E&G tested C>L 2 E speakers, divided them into two groups based on a pretest of their production of subject-verb agreement (idea: “no-agreement” subjects would have not valued their features yet, “agreement” subjects have at least valued some of them). Finding: No-agreement subjects acted like native speakers, agreement subjects didn’t differentiate between grammatical and ungrammatical verbadverb orders. Hmm.

Eubank & Grace (1998) n n n E&G tested C>L 2 E speakers, divided them into two groups based on a pretest of their production of subject-verb agreement (idea: “no-agreement” subjects would have not valued their features yet, “agreement” subjects have at least valued some of them). Finding: No-agreement subjects acted like native speakers, agreement subjects didn’t differentiate between grammatical and ungrammatical verbadverb orders. Hmm.

Eubank et al. (1997) n Same basic premises, different tasks: n n n Tom draws slowly jumping monkeys. For a V-raiser, this should be ambiguous (is the jumping slow or is the drawing slow? ). Eubank et al. (1997) used a kind of TVJ task to test this. Even prior to looking at the results, one problem here is that this is fine in L 1 English if slowly is taken as a parenthetical (“Tom draws— slowly— jumping monkeys”). But that’s the crucial interpretation that is supposed to show verb raising is grammatical. What could we conclude, no matter what the results are?

Eubank et al. (1997) n Same basic premises, different tasks: n n n Tom draws slowly jumping monkeys. For a V-raiser, this should be ambiguous (is the jumping slow or is the drawing slow? ). Eubank et al. (1997) used a kind of TVJ task to test this. Even prior to looking at the results, one problem here is that this is fine in L 1 English if slowly is taken as a parenthetical (“Tom draws— slowly— jumping monkeys”). But that’s the crucial interpretation that is supposed to show verb raising is grammatical. What could we conclude, no matter what the results are?

Eubank et al. (1997) n n The actual results didn’t go along very well with the predictions either. Pretty low acceptance rate of raised-V interpretations if they’re really supposed to be grammatical in the IL. And the agreement group wasn’t acting native-speaker-like either, even though they should have valued the feature. Eubank et al. actually go further with the VFH, hypothesizing that this is not only the initial state, but also the inescapable final state—L 2 features cannot be valued (hence the lack of serious improvement among the agreement group—”Local Impairment”, for next week).

Eubank et al. (1997) n n The actual results didn’t go along very well with the predictions either. Pretty low acceptance rate of raised-V interpretations if they’re really supposed to be grammatical in the IL. And the agreement group wasn’t acting native-speaker-like either, even though they should have valued the feature. Eubank et al. actually go further with the VFH, hypothesizing that this is not only the initial state, but also the inescapable final state—L 2 features cannot be valued (hence the lack of serious improvement among the agreement group—”Local Impairment”, for next week).

Schwartz 1998 n Promotes the idea that L 2 patterns come about from full transfer and full access. The entire L 1 grammar (not just short trees) is the starting point. n Nothing stops parameters from being reset in the IL. n

Schwartz 1998 n Promotes the idea that L 2 patterns come about from full transfer and full access. The entire L 1 grammar (not just short trees) is the starting point. n Nothing stops parameters from being reset in the IL. n

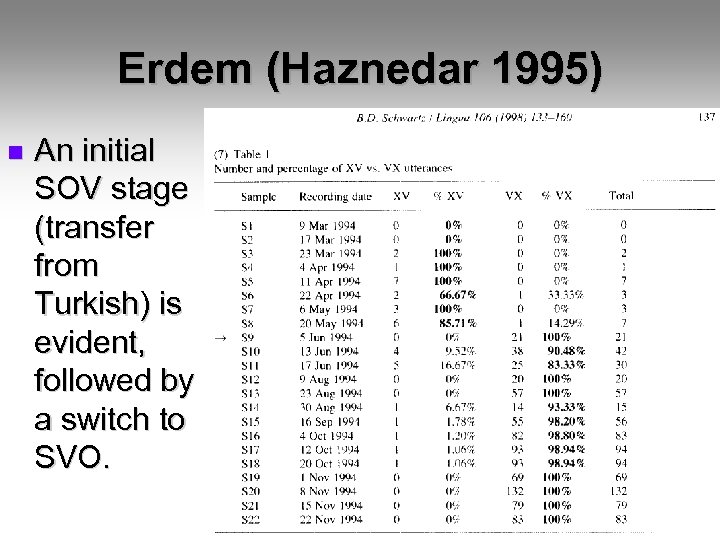

Erdem (Haznedar 1995) n An initial SOV stage (transfer from Turkish) is evident, followed by a switch to SVO.

Erdem (Haznedar 1995) n An initial SOV stage (transfer from Turkish) is evident, followed by a switch to SVO.

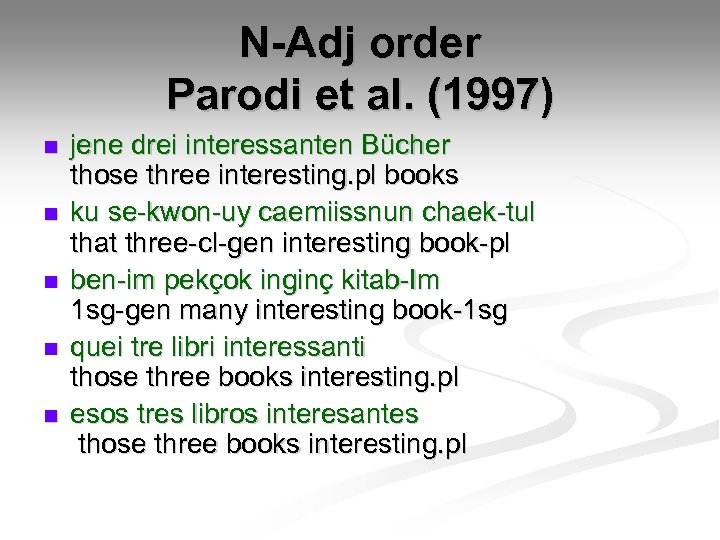

N-Adj order Parodi et al. (1997) n n n jene drei interessanten Bücher those three interesting. pl books ku se-kwon-uy caemiissnun chaek-tul that three-cl-gen interesting book-pl ben-im pekçok inginç kitab-Im 1 sg-gen many interesting book-1 sg quei tre libri interessanti those three books interesting. pl esos tres libros interesantes those three books interesting. pl

N-Adj order Parodi et al. (1997) n n n jene drei interessanten Bücher those three interesting. pl books ku se-kwon-uy caemiissnun chaek-tul that three-cl-gen interesting book-pl ben-im pekçok inginç kitab-Im 1 sg-gen many interesting book-1 sg quei tre libri interessanti those three books interesting. pl esos tres libros interesantes those three books interesting. pl

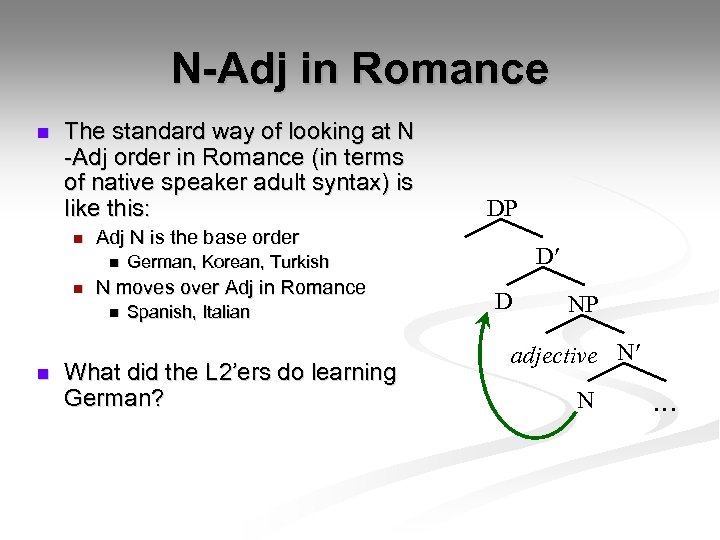

N-Adj in Romance n The standard way of looking at N -Adj order in Romance (in terms of native speaker adult syntax) is like this: n Adj N is the base order n n D German, Korean, Turkish N moves over Adj in Romance n n DP Spanish, Italian What did the L 2’ers do learning German? D NP adjective N N …

N-Adj in Romance n The standard way of looking at N -Adj order in Romance (in terms of native speaker adult syntax) is like this: n Adj N is the base order n n D German, Korean, Turkish N moves over Adj in Romance n n DP Spanish, Italian What did the L 2’ers do learning German? D NP adjective N N …

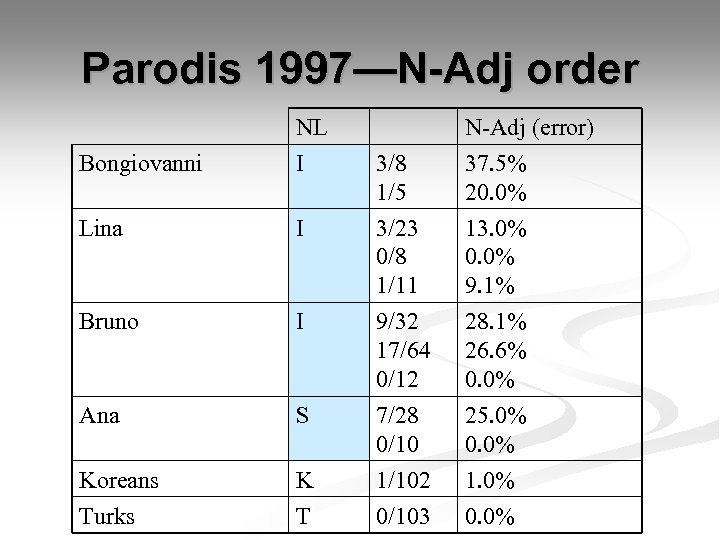

Parodis 1997—N-Adj order Bongiovanni NL I 3/8 1/5 N-Adj (error) 37. 5% 20. 0% Lina I 3/23 0/8 1/11 13. 0% 0. 0% 9. 1% Bruno I Ana S 9/32 17/64 0/12 7/28 0/10 28. 1% 26. 6% 0. 0% 25. 0% 0. 0% Koreans Turks K T 1/102 0/103 1. 0% 0. 0%

Parodis 1997—N-Adj order Bongiovanni NL I 3/8 1/5 N-Adj (error) 37. 5% 20. 0% Lina I 3/23 0/8 1/11 13. 0% 0. 0% 9. 1% Bruno I Ana S 9/32 17/64 0/12 7/28 0/10 28. 1% 26. 6% 0. 0% 25. 0% 0. 0% Koreans Turks K T 1/102 0/103 1. 0% 0. 0%

So… n n So, movement seems to be initially transferred, and has to be unlearned. The evidence for the tree building approach doesn’t seem all that strong anymore. n n n No nice Case results like in L 1. Higher parameters seem to transfer (*VFH, *Minimal Trees) Morphology and finiteness somewhat separate (to be discussed in two weeks).

So… n n So, movement seems to be initially transferred, and has to be unlearned. The evidence for the tree building approach doesn’t seem all that strong anymore. n n n No nice Case results like in L 1. Higher parameters seem to transfer (*VFH, *Minimal Trees) Morphology and finiteness somewhat separate (to be discussed in two weeks).

No transfer/Full access n Epstein, Flynn, and Martohardjono (1996) wrote a well-known BBS article endorsing the view that L 2 A is not only UG-constrained, but that it basically “starts over” with UG like L 1 A does. n Editorial comment: It’s worth reading, but the responses are at least as important as the article.

No transfer/Full access n Epstein, Flynn, and Martohardjono (1996) wrote a well-known BBS article endorsing the view that L 2 A is not only UG-constrained, but that it basically “starts over” with UG like L 1 A does. n Editorial comment: It’s worth reading, but the responses are at least as important as the article.

New parameter settings n n Japanese vs. English = SOV vs. SVO. EFM make a mysterious statement: n “Left-headed C° correlates with right-branching adjunction and rightheaded C° with left-branching adjunction” n …followed by an example of how English allows both left and right adjunction. n What EFM must mean is that SVO language-speakers prefer postposed adverbial clauses. n n The worker called the owner [when the engineer finished the plans]. [When the actor finished the book] the woman called the professor.

New parameter settings n n Japanese vs. English = SOV vs. SVO. EFM make a mysterious statement: n “Left-headed C° correlates with right-branching adjunction and rightheaded C° with left-branching adjunction” n …followed by an example of how English allows both left and right adjunction. n What EFM must mean is that SVO language-speakers prefer postposed adverbial clauses. n n The worker called the owner [when the engineer finished the plans]. [When the actor finished the book] the woman called the professor.

New parameter settings n And then EFM proceed to report that Japanese speakers (J>L 2 E) don’t significantly prefer preverbal adverbial clauses (purported SOV preference), and eventually prefer postverbal adverbial clauses (purported SVO preference). n But preferences are not parameter settings in any obvious way. Nothing is ruled out in any event—this is not a very useful result (see also Schwartz’s response).

New parameter settings n And then EFM proceed to report that Japanese speakers (J>L 2 E) don’t significantly prefer preverbal adverbial clauses (purported SOV preference), and eventually prefer postverbal adverbial clauses (purported SVO preference). n But preferences are not parameter settings in any obvious way. Nothing is ruled out in any event—this is not a very useful result (see also Schwartz’s response).

Martohardjono 1993 Interesting test of relative judgments. n It is generally agreed that ECP violations… n n n are worse than Subjacency violations n n Which waiter did the man leave the table after spilled the soup? Which patient did Max explain how the poison killed? Do L 2’ers get these kinds of judgments?

Martohardjono 1993 Interesting test of relative judgments. n It is generally agreed that ECP violations… n n n are worse than Subjacency violations n n Which waiter did the man leave the table after spilled the soup? Which patient did Max explain how the poison killed? Do L 2’ers get these kinds of judgments?

Martohardjono 1993 n n Turns out, yeah, they seem to. But it turns out that speakers of languages without overt wh-movement had lower accuracy on judging the violations overall. So: L 1 has some effect (although EFM don’t really talk about this much, something which occupies much of the peer reviewers’ time). EFM suggest that these judgments cannot be coming from the L 1 alone, but of course this also relies on the view that L 1 is significantly impoverished by “instantiation” (not the common view, not even in 1996).

Martohardjono 1993 n n Turns out, yeah, they seem to. But it turns out that speakers of languages without overt wh-movement had lower accuracy on judging the violations overall. So: L 1 has some effect (although EFM don’t really talk about this much, something which occupies much of the peer reviewers’ time). EFM suggest that these judgments cannot be coming from the L 1 alone, but of course this also relies on the view that L 1 is significantly impoverished by “instantiation” (not the common view, not even in 1996).

EFM’s experiment n Elicited imitation, Japanese speakers learning English (33 kids, 18 adults). n Trying to elicit sentences with things associated with functional categories (tense marking, modals, do-support for IP; topicalization, relative clauses, wh-questions for CP). The point was actually more to refute the idea that adults have UG “turned off” after a “critical period” than anything else (a discussion we’ll return to) n

EFM’s experiment n Elicited imitation, Japanese speakers learning English (33 kids, 18 adults). n Trying to elicit sentences with things associated with functional categories (tense marking, modals, do-support for IP; topicalization, relative clauses, wh-questions for CP). The point was actually more to refute the idea that adults have UG “turned off” after a “critical period” than anything else (a discussion we’ll return to) n

EFM’s experiment n n n Kids did equally well in this repetition task as adults. Kids seemed to get around 70% success on IP-related things, around 50% success on CP-related things. The deeper topicalizations are harder than shallower topicalizations. EFM would have you believe: n n Based on their data collapsing over all kids and over all adults, there are no stages. CP is there just as much as IP is there, despite the higher success with IP, just because CP-related structures are intrinsically harder/more complex. It could be true, but it’s certainly not a knock-down argument against V&YS or any of the other alternatives. Also, as White (2003) notes, none of these sentences were ungrammatical (which we might have expected to be “repaired” under repetition)… if this is even a reliable task to begin with.

EFM’s experiment n n n Kids did equally well in this repetition task as adults. Kids seemed to get around 70% success on IP-related things, around 50% success on CP-related things. The deeper topicalizations are harder than shallower topicalizations. EFM would have you believe: n n Based on their data collapsing over all kids and over all adults, there are no stages. CP is there just as much as IP is there, despite the higher success with IP, just because CP-related structures are intrinsically harder/more complex. It could be true, but it’s certainly not a knock-down argument against V&YS or any of the other alternatives. Also, as White (2003) notes, none of these sentences were ungrammatical (which we might have expected to be “repaired” under repetition)… if this is even a reliable task to begin with.

L 2 A and UG n n We can ask many of the same questions we asked about syntax, but of phonology. Learners have an interlanguage grammar of phonology as well. n n Is this grammar primarily a product of transfer? Can parameters be set for the target language values? Do interlanguage phonologies act like real languages (constrained by UG)? Here, it it rather obvious just from our anecdotal experience with the world that transfer plays a big role and parameters are hard to set (to a value different from the L 1’s value).

L 2 A and UG n n We can ask many of the same questions we asked about syntax, but of phonology. Learners have an interlanguage grammar of phonology as well. n n Is this grammar primarily a product of transfer? Can parameters be set for the target language values? Do interlanguage phonologies act like real languages (constrained by UG)? Here, it it rather obvious just from our anecdotal experience with the world that transfer plays a big role and parameters are hard to set (to a value different from the L 1’s value).

Phonological interference If L 1’ers lose the ability to hear a contrast not in the L 1, there is a strong possibility that the L 1 phonology filters the L 2 input. n L 2’ers may not be getting the same data as L 1’ers. Even if the LAD were still working, it would be getting different data. n n If you don’t perceive the contrast, you won’t acquire the contrast.

Phonological interference If L 1’ers lose the ability to hear a contrast not in the L 1, there is a strong possibility that the L 1 phonology filters the L 2 input. n L 2’ers may not be getting the same data as L 1’ers. Even if the LAD were still working, it would be getting different data. n n If you don’t perceive the contrast, you won’t acquire the contrast.

Phonological features n Phonologists over the years have come up with a system of (universal) features that differentiate between sounds. n n /p/ vs. /b/ differ in [+voice]. /p/ vs. /f/ differ in [+continuant]. … What L 1’ers seem to be doing is determining which features contrast in the language. If the language doesn’t distinguish voiced from voiceless consonants, L 1’ers come to ignore [±voice].

Phonological features n Phonologists over the years have come up with a system of (universal) features that differentiate between sounds. n n /p/ vs. /b/ differ in [+voice]. /p/ vs. /f/ differ in [+continuant]. … What L 1’ers seem to be doing is determining which features contrast in the language. If the language doesn’t distinguish voiced from voiceless consonants, L 1’ers come to ignore [±voice].

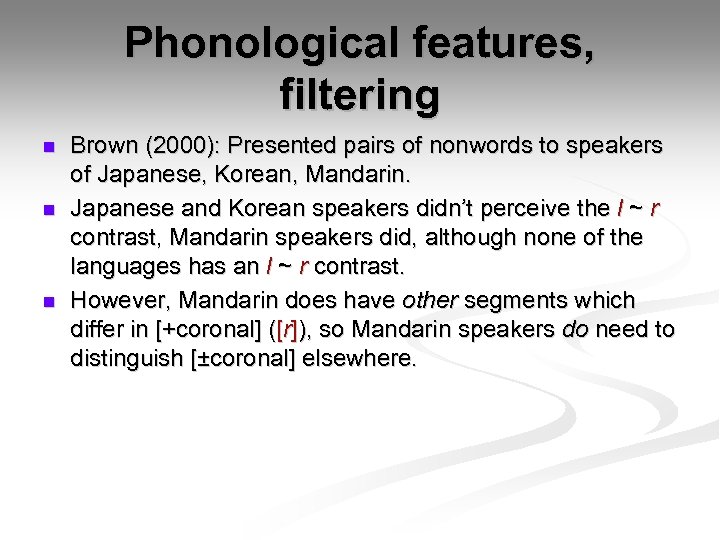

Phonological features, filtering n n n Brown (2000): Presented pairs of nonwords to speakers of Japanese, Korean, Mandarin. Japanese and Korean speakers didn’t perceive the l ~ r contrast, Mandarin speakers did, although none of the languages has an l ~ r contrast. However, Mandarin does have other segments which differ in [+coronal] ([r]), so Mandarin speakers do need to distinguish [±coronal] elsewhere.

Phonological features, filtering n n n Brown (2000): Presented pairs of nonwords to speakers of Japanese, Korean, Mandarin. Japanese and Korean speakers didn’t perceive the l ~ r contrast, Mandarin speakers did, although none of the languages has an l ~ r contrast. However, Mandarin does have other segments which differ in [+coronal] ([r]), so Mandarin speakers do need to distinguish [±coronal] elsewhere.

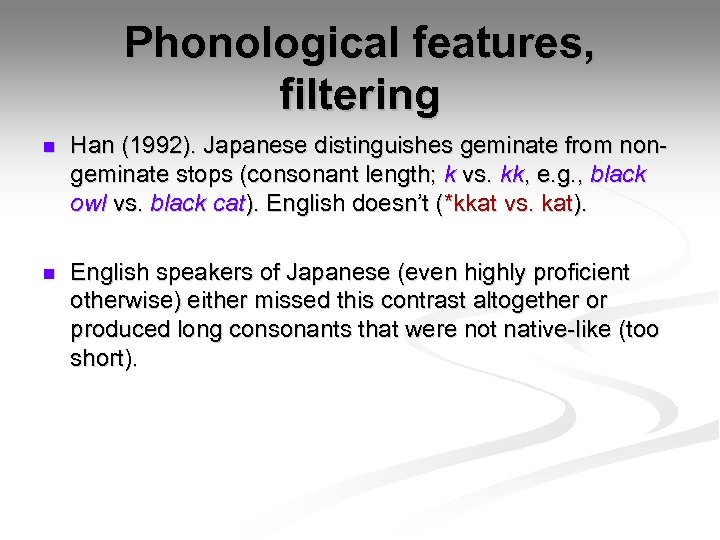

Phonological features, filtering n Han (1992). Japanese distinguishes geminate from nongeminate stops (consonant length; k vs. kk, e. g. , black owl vs. black cat). English doesn’t (*kkat vs. kat). n English speakers of Japanese (even highly proficient otherwise) either missed this contrast altogether or produced long consonants that were not native-like (too short).

Phonological features, filtering n Han (1992). Japanese distinguishes geminate from nongeminate stops (consonant length; k vs. kk, e. g. , black owl vs. black cat). English doesn’t (*kkat vs. kat). n English speakers of Japanese (even highly proficient otherwise) either missed this contrast altogether or produced long consonants that were not native-like (too short).

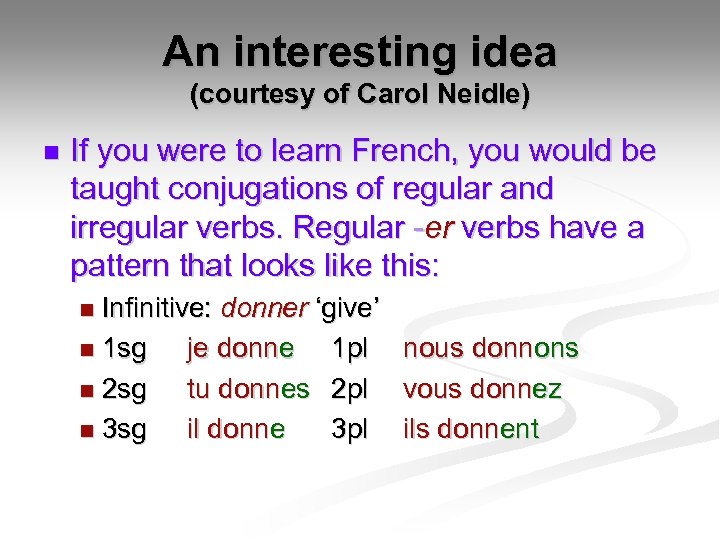

An interesting idea (courtesy of Carol Neidle) n If you were to learn French, you would be taught conjugations of regular and irregular verbs. Regular -er verbs have a pattern that looks like this: Infinitive: donner ‘give’ n 1 sg je donne 1 pl nous donnons n 2 sg tu donnes 2 pl vous donnez n 3 sg il donne 3 pl ils donnent n

An interesting idea (courtesy of Carol Neidle) n If you were to learn French, you would be taught conjugations of regular and irregular verbs. Regular -er verbs have a pattern that looks like this: Infinitive: donner ‘give’ n 1 sg je donne 1 pl nous donnons n 2 sg tu donnes 2 pl vous donnez n 3 sg il donne 3 pl ils donnent n

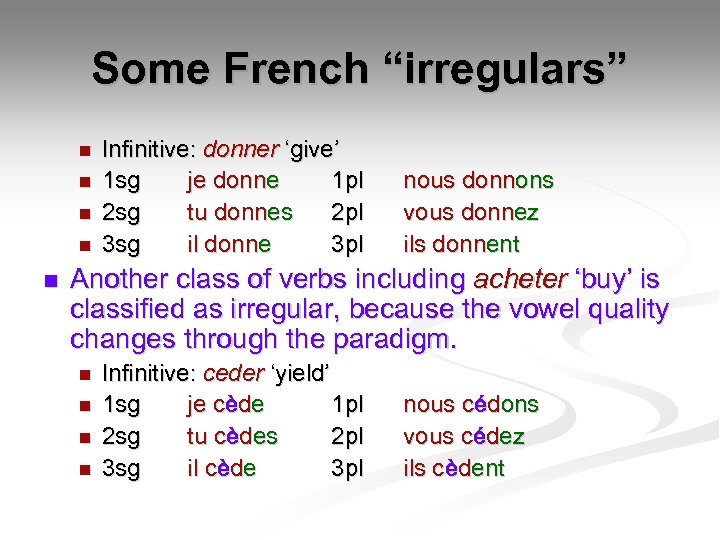

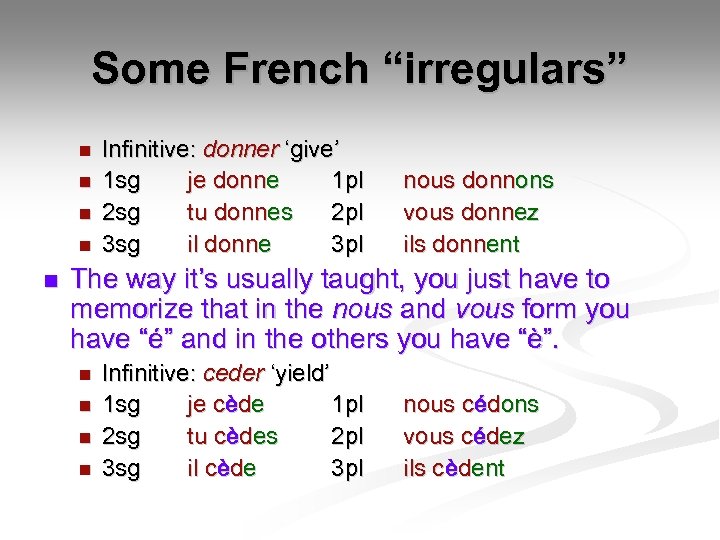

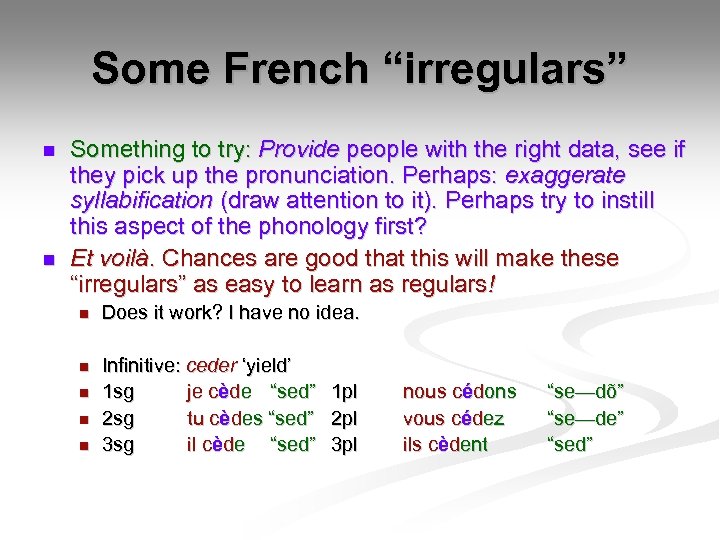

Some French “irregulars” n n n Infinitive: donner ‘give’ 1 sg je donne 1 pl 2 sg tu donnes 2 pl 3 sg il donne 3 pl nous donnons vous donnez ils donnent Another class of verbs including acheter ‘buy’ is classified as irregular, because the vowel quality changes through the paradigm. n n Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’ 1 sg je cède 1 pl 2 sg tu cèdes 2 pl 3 sg il cède 3 pl nous cédons vous cédez ils cèdent

Some French “irregulars” n n n Infinitive: donner ‘give’ 1 sg je donne 1 pl 2 sg tu donnes 2 pl 3 sg il donne 3 pl nous donnons vous donnez ils donnent Another class of verbs including acheter ‘buy’ is classified as irregular, because the vowel quality changes through the paradigm. n n Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’ 1 sg je cède 1 pl 2 sg tu cèdes 2 pl 3 sg il cède 3 pl nous cédons vous cédez ils cèdent

Some French “irregulars” n n n Infinitive: donner ‘give’ 1 sg je donne 1 pl 2 sg tu donnes 2 pl 3 sg il donne 3 pl nous donnons vous donnez ils donnent The way it’s usually taught, you just have to memorize that in the nous and vous form you have “é” and in the others you have “è”. n n Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’ 1 sg je cède 1 pl 2 sg tu cèdes 2 pl 3 sg il cède 3 pl nous cédons vous cédez ils cèdent

Some French “irregulars” n n n Infinitive: donner ‘give’ 1 sg je donne 1 pl 2 sg tu donnes 2 pl 3 sg il donne 3 pl nous donnons vous donnez ils donnent The way it’s usually taught, you just have to memorize that in the nous and vous form you have “é” and in the others you have “è”. n n Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’ 1 sg je cède 1 pl 2 sg tu cèdes 2 pl 3 sg il cède 3 pl nous cédons vous cédez ils cèdent

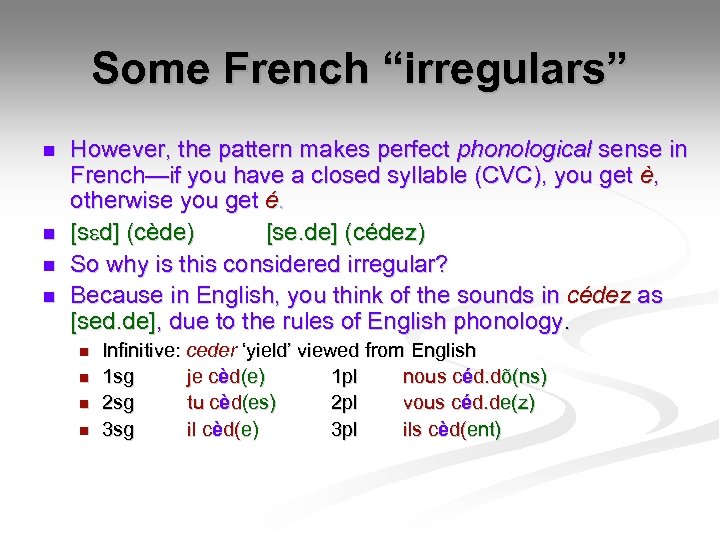

Some French “irregulars” n n However, the pattern makes perfect phonological sense in French—if you have a closed syllable (CVC), you get è, otherwise you get é. [s d] (cède) [se. de] (cédez) So why is this considered irregular? Because in English, you think of the sounds in cédez as [sed. de], due to the rules of English phonology. n n Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’ viewed from English 1 sg je cèd(e) 1 pl nous céd. dõ(ns) 2 sg tu cèd(es) 2 pl vous céd. de(z) 3 sg il cèd(e) 3 pl ils cèd(ent)

Some French “irregulars” n n However, the pattern makes perfect phonological sense in French—if you have a closed syllable (CVC), you get è, otherwise you get é. [s d] (cède) [se. de] (cédez) So why is this considered irregular? Because in English, you think of the sounds in cédez as [sed. de], due to the rules of English phonology. n n Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’ viewed from English 1 sg je cèd(e) 1 pl nous céd. dõ(ns) 2 sg tu cèd(es) 2 pl vous céd. de(z) 3 sg il cèd(e) 3 pl ils cèd(ent)

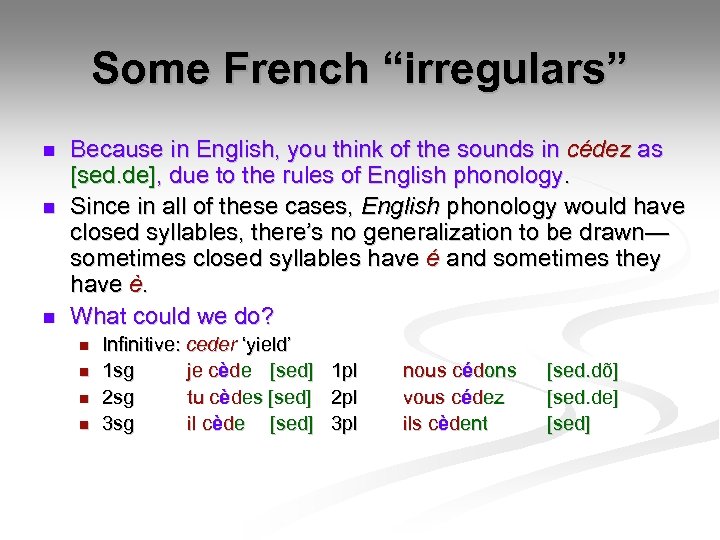

Some French “irregulars” n n n Because in English, you think of the sounds in cédez as [sed. de], due to the rules of English phonology. Since in all of these cases, English phonology would have closed syllables, there’s no generalization to be drawn— sometimes closed syllables have é and sometimes they have è. What could we do? n n Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’ 1 sg je cède [sed] 2 sg tu cèdes [sed] 3 sg il cède [sed] 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl nous cédons vous cédez ils cèdent [sed. dõ] [sed. de] [sed]

Some French “irregulars” n n n Because in English, you think of the sounds in cédez as [sed. de], due to the rules of English phonology. Since in all of these cases, English phonology would have closed syllables, there’s no generalization to be drawn— sometimes closed syllables have é and sometimes they have è. What could we do? n n Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’ 1 sg je cède [sed] 2 sg tu cèdes [sed] 3 sg il cède [sed] 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl nous cédons vous cédez ils cèdent [sed. dõ] [sed. de] [sed]

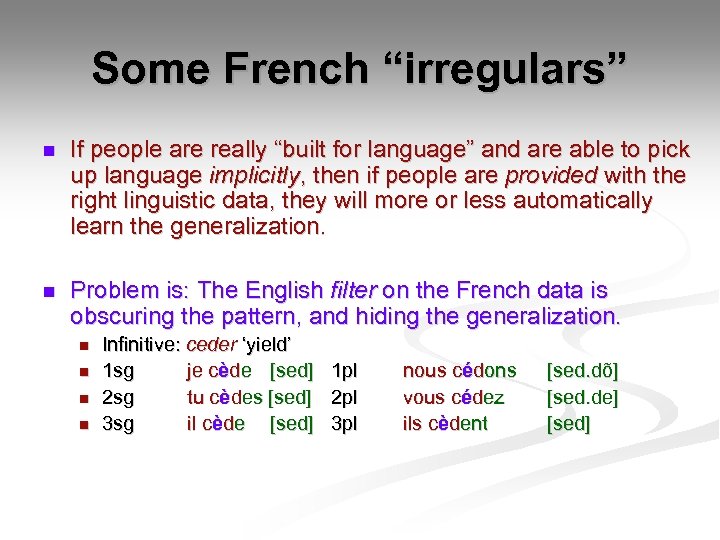

Some French “irregulars” n If people are really “built for language” and are able to pick up language implicitly, then if people are provided with the right linguistic data, they will more or less automatically learn the generalization. n Problem is: The English filter on the French data is obscuring the pattern, and hiding the generalization. n n Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’ 1 sg je cède [sed] 2 sg tu cèdes [sed] 3 sg il cède [sed] 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl nous cédons vous cédez ils cèdent [sed. dõ] [sed. de] [sed]

Some French “irregulars” n If people are really “built for language” and are able to pick up language implicitly, then if people are provided with the right linguistic data, they will more or less automatically learn the generalization. n Problem is: The English filter on the French data is obscuring the pattern, and hiding the generalization. n n Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’ 1 sg je cède [sed] 2 sg tu cèdes [sed] 3 sg il cède [sed] 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl nous cédons vous cédez ils cèdent [sed. dõ] [sed. de] [sed]

Some French “irregulars” n n Something to try: Provide people with the right data, see if they pick up the pronunciation. Perhaps: exaggerate syllabification (draw attention to it). Perhaps try to instill this aspect of the phonology first? Et voilà. Chances are good that this will make these “irregulars” as easy to learn as regulars! n Does it work? I have no idea. n Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’ 1 sg je cède “sed” 1 pl 2 sg tu cèdes “sed” 2 pl 3 sg il cède “sed” 3 pl n nous cédons vous cédez ils cèdent “se—dõ” “se—de” “sed”

Some French “irregulars” n n Something to try: Provide people with the right data, see if they pick up the pronunciation. Perhaps: exaggerate syllabification (draw attention to it). Perhaps try to instill this aspect of the phonology first? Et voilà. Chances are good that this will make these “irregulars” as easy to learn as regulars! n Does it work? I have no idea. n Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’ 1 sg je cède “sed” 1 pl 2 sg tu cèdes “sed” 2 pl 3 sg il cède “sed” 3 pl n nous cédons vous cédez ils cèdent “se—dõ” “se—de” “sed”

Where we are n We’re concerned with discovering to what extent linguistic theory (=theories of UG) bears on questions of L 2 A, with an eye toward the question: To what extent is knowledge of an L 2 like knowledge of an L 1? n Do they conform to universal principles? (ECP, Subjacency) n n No? UG is not constraining L 2. Yes? Consistent with UG constraining L 2, but not evidence for it. Do they have a parameter setting different from the L 1 (and all of the consequences following therefrom)? n Yes? UG is constraining L 2. No? Inconclusive for the general case.

Where we are n We’re concerned with discovering to what extent linguistic theory (=theories of UG) bears on questions of L 2 A, with an eye toward the question: To what extent is knowledge of an L 2 like knowledge of an L 1? n Do they conform to universal principles? (ECP, Subjacency) n n No? UG is not constraining L 2. Yes? Consistent with UG constraining L 2, but not evidence for it. Do they have a parameter setting different from the L 1 (and all of the consequences following therefrom)? n Yes? UG is constraining L 2. No? Inconclusive for the general case.

Stepping back a bit n Let’s take some time to look at a few results coming out of an earlier tradition, not strictly Principles & Parameters (and not covered by White) but still suggesting that to a certain extent L 2 learners may know something (perhaps unconsciously) about “what Language is like” (which is a certain way we might characterize the content of UG).

Stepping back a bit n Let’s take some time to look at a few results coming out of an earlier tradition, not strictly Principles & Parameters (and not covered by White) but still suggesting that to a certain extent L 2 learners may know something (perhaps unconsciously) about “what Language is like” (which is a certain way we might characterize the content of UG).

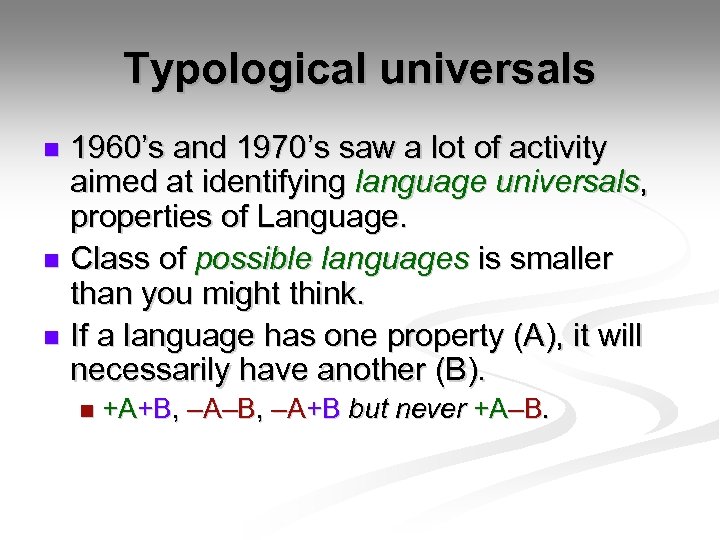

Typological universals 1960’s and 1970’s saw a lot of activity aimed at identifying language universals, properties of Language. n Class of possible languages is smaller than you might think. n If a language has one property (A), it will necessarily have another (B). n n +A+B, –A–B, –A+B but never +A–B.

Typological universals 1960’s and 1970’s saw a lot of activity aimed at identifying language universals, properties of Language. n Class of possible languages is smaller than you might think. n If a language has one property (A), it will necessarily have another (B). n n +A+B, –A–B, –A+B but never +A–B.

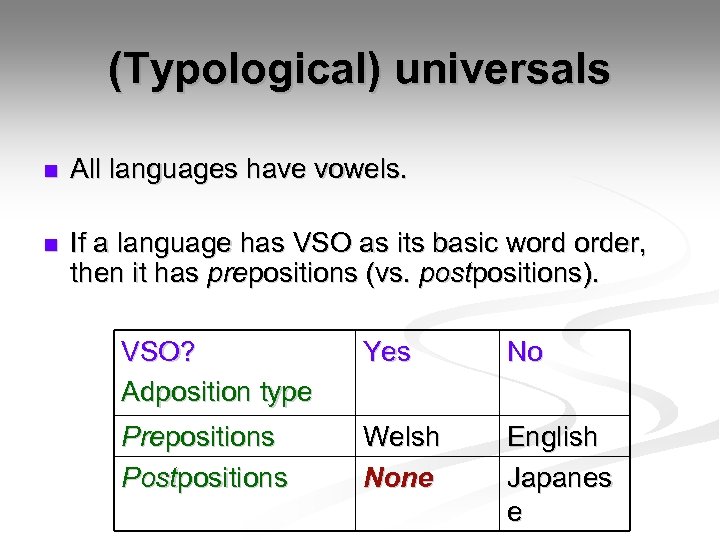

(Typological) universals n All languages have vowels. n If a language has VSO as its basic word order, then it has prepositions (vs. postpositions). VSO? Adposition type Yes No Prepositions Postpositions Welsh None English Japanes e

(Typological) universals n All languages have vowels. n If a language has VSO as its basic word order, then it has prepositions (vs. postpositions). VSO? Adposition type Yes No Prepositions Postpositions Welsh None English Japanes e

Markedness n n Having duals implies having plurals Having plurals says nothing about having duals. Having duals is marked—infrequent, more complex. Having plurals is (relative to having duals) unmarked. Generally markedness is in terms of comparable dimensions, but you could also say that being VSO is marked relative to having prepositions.

Markedness n n Having duals implies having plurals Having plurals says nothing about having duals. Having duals is marked—infrequent, more complex. Having plurals is (relative to having duals) unmarked. Generally markedness is in terms of comparable dimensions, but you could also say that being VSO is marked relative to having prepositions.

Markedness “Markedness” actually has been used in a couple of different ways, although they share a common core. n Marked: More unlikely, in some sense. n Unmarked: More likely, in some sense. n n You have to “mark” something marked; unmarked is what you get if you don’t say anything extra.

Markedness “Markedness” actually has been used in a couple of different ways, although they share a common core. n Marked: More unlikely, in some sense. n Unmarked: More likely, in some sense. n n You have to “mark” something marked; unmarked is what you get if you don’t say anything extra.

![“Unlikeliness” n Typological / crosslinguistic infrequency. n n More complex constructions. n n [ts] “Unlikeliness” n Typological / crosslinguistic infrequency. n n More complex constructions. n n [ts]](https://present5.com/presentation/547bbabcf705468c4a92e5802b4490cb/image-76.jpg) “Unlikeliness” n Typological / crosslinguistic infrequency. n n More complex constructions. n n [ts] is more marked than [t]. The non-default setting of a parameter. n n VOS word order is marked. Non-null subjects? Language-specific/idiosyncratic features. n Vs. UG/universal features…?

“Unlikeliness” n Typological / crosslinguistic infrequency. n n More complex constructions. n n [ts] is more marked than [t]. The non-default setting of a parameter. n n VOS word order is marked. Non-null subjects? Language-specific/idiosyncratic features. n Vs. UG/universal features…?

Berlin & Kay 1969: Color terms (On the boundaries of psychophysics, linguistics, anthropology, and with issues about its interpretation, but still…) n Basic color terms across languages. n It turns out that languages differ in how many color terms count as basic. (blueish, salmon-colored, crimson, blond, … are not basic). n

Berlin & Kay 1969: Color terms (On the boundaries of psychophysics, linguistics, anthropology, and with issues about its interpretation, but still…) n Basic color terms across languages. n It turns out that languages differ in how many color terms count as basic. (blueish, salmon-colored, crimson, blond, … are not basic). n

Berlin & Kay 1969: Color terms n The segmentation of experience by speech symbols is essentially arbitrary. The different sets of words for color in various languages are perhaps the best ready evidence for such essential arbitrariness. For example, in a high percentage of African languages, there are only three “color words, ” corresponding to our white, black, red, which nevertheless divide up the entire spectrum. In the Tarahumara language of Mexico, there are five basic color words, and here “blue” and “green” are subsumed under a single term. n Eugene Nida (1959)

Berlin & Kay 1969: Color terms n The segmentation of experience by speech symbols is essentially arbitrary. The different sets of words for color in various languages are perhaps the best ready evidence for such essential arbitrariness. For example, in a high percentage of African languages, there are only three “color words, ” corresponding to our white, black, red, which nevertheless divide up the entire spectrum. In the Tarahumara language of Mexico, there are five basic color words, and here “blue” and “green” are subsumed under a single term. n Eugene Nida (1959)

Berlin & Kay 1969: Color terms n n n n n Arabic (Lebanon) Bulgarian (Bulgaria) Catalan (Spain) Cantonese (China) Mandarin (China) English (US) Hebrew (Israel) Hungarian (Hungary) Ibibo (Nigeria) Indonesian (Indonesia) n n n n n Japanese (Japan) Korean (Korea) Pomo (California) Spanish (Mexico) Swahili (East Africa) Tagalog (Philippines) Thai (Thailand) Tzeltal (Southern Mexico) Urdu (India) Vietnamese (Vietnam)

Berlin & Kay 1969: Color terms n n n n n Arabic (Lebanon) Bulgarian (Bulgaria) Catalan (Spain) Cantonese (China) Mandarin (China) English (US) Hebrew (Israel) Hungarian (Hungary) Ibibo (Nigeria) Indonesian (Indonesia) n n n n n Japanese (Japan) Korean (Korea) Pomo (California) Spanish (Mexico) Swahili (East Africa) Tagalog (Philippines) Thai (Thailand) Tzeltal (Southern Mexico) Urdu (India) Vietnamese (Vietnam)

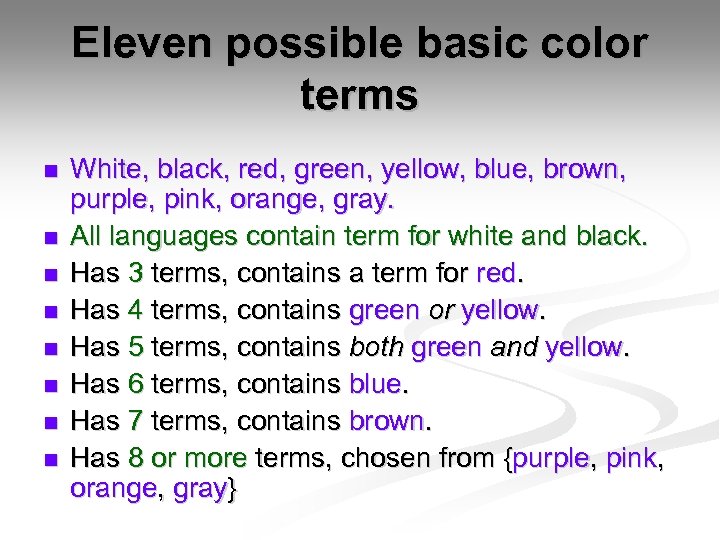

Eleven possible basic color terms n n n n White, black, red, green, yellow, blue, brown, purple, pink, orange, gray. All languages contain term for white and black. Has 3 terms, contains a term for red. Has 4 terms, contains green or yellow. Has 5 terms, contains both green and yellow. Has 6 terms, contains blue. Has 7 terms, contains brown. Has 8 or more terms, chosen from {purple, pink, orange, gray}

Eleven possible basic color terms n n n n White, black, red, green, yellow, blue, brown, purple, pink, orange, gray. All languages contain term for white and black. Has 3 terms, contains a term for red. Has 4 terms, contains green or yellow. Has 5 terms, contains both green and yellow. Has 6 terms, contains blue. Has 7 terms, contains brown. Has 8 or more terms, chosen from {purple, pink, orange, gray}

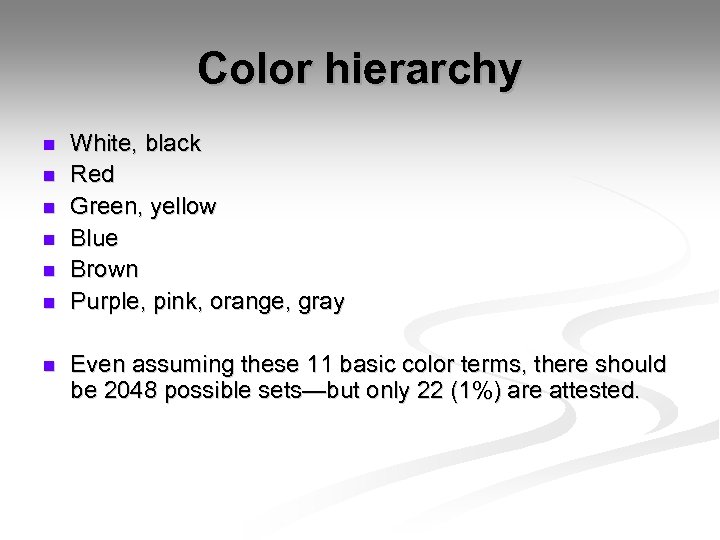

Color hierarchy n n n n White, black Red Green, yellow Blue Brown Purple, pink, orange, gray Even assuming these 11 basic color terms, there should be 2048 possible sets—but only 22 (1%) are attested.

Color hierarchy n n n n White, black Red Green, yellow Blue Brown Purple, pink, orange, gray Even assuming these 11 basic color terms, there should be 2048 possible sets—but only 22 (1%) are attested.

Color terms n n n n BW BWR Jalé (New Guinea) ‘brilliant’ vs. ‘dull’ Tiv (Nigeria), Australian aboriginals in Seven Rivers District, Queensland. BWRG Ibibo (Nigeria), Hanunóo (Philippines) BWRY Ibo (Nigeria), Fitzroy River people (Queensland) BWRYG Tzeltal (Mexico), Daza (eastern Nigeria) BWRYGU Plains Tamil (South India), Nupe (Nigeria), Mandarin? BWRYGUO Nez Perce (Washington), Malayalam (southern India)

Color terms n n n n BW BWR Jalé (New Guinea) ‘brilliant’ vs. ‘dull’ Tiv (Nigeria), Australian aboriginals in Seven Rivers District, Queensland. BWRG Ibibo (Nigeria), Hanunóo (Philippines) BWRY Ibo (Nigeria), Fitzroy River people (Queensland) BWRYG Tzeltal (Mexico), Daza (eastern Nigeria) BWRYGU Plains Tamil (South India), Nupe (Nigeria), Mandarin? BWRYGUO Nez Perce (Washington), Malayalam (southern India)

Color terms Interesting questions abound, including why this order, why these eleven—and there are potential reasons for it that can be drawn from the perception of color spaces which we will not attempt here. n The point is: This is a fact about Language: If you have a basic color term for blue, you also have basic color terms for black, white, red, green, and yellow. n

Color terms Interesting questions abound, including why this order, why these eleven—and there are potential reasons for it that can be drawn from the perception of color spaces which we will not attempt here. n The point is: This is a fact about Language: If you have a basic color term for blue, you also have basic color terms for black, white, red, green, and yellow. n

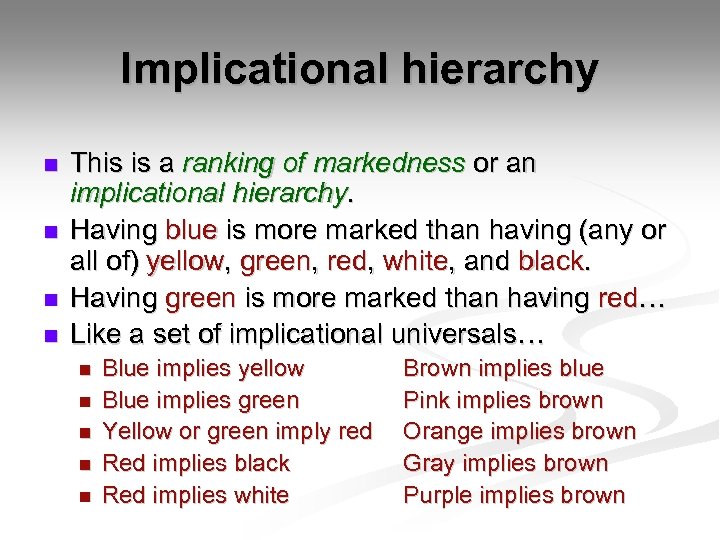

Implicational hierarchy n n This is a ranking of markedness or an implicational hierarchy. Having blue is more marked than having (any or all of) yellow, green, red, white, and black. Having green is more marked than having red… Like a set of implicational universals… n n n Blue implies yellow Blue implies green Yellow or green imply red Red implies black Red implies white Brown implies blue Pink implies brown Orange implies brown Gray implies brown Purple implies brown

Implicational hierarchy n n This is a ranking of markedness or an implicational hierarchy. Having blue is more marked than having (any or all of) yellow, green, red, white, and black. Having green is more marked than having red… Like a set of implicational universals… n n n Blue implies yellow Blue implies green Yellow or green imply red Red implies black Red implies white Brown implies blue Pink implies brown Orange implies brown Gray implies brown Purple implies brown

L 2 A? Our overarching theme: How much is L 2/IL like a L 1? n Do L 2/IL languages obey the language universals that hold of native languages? n This question is slightly less theory-laden than the questions we were asking about principles and parameters, although it’s similar… n To my knowledge nobody has studied L 2 acquisitions of color terms… n

L 2 A? Our overarching theme: How much is L 2/IL like a L 1? n Do L 2/IL languages obey the language universals that hold of native languages? n This question is slightly less theory-laden than the questions we were asking about principles and parameters, although it’s similar… n To my knowledge nobody has studied L 2 acquisitions of color terms… n

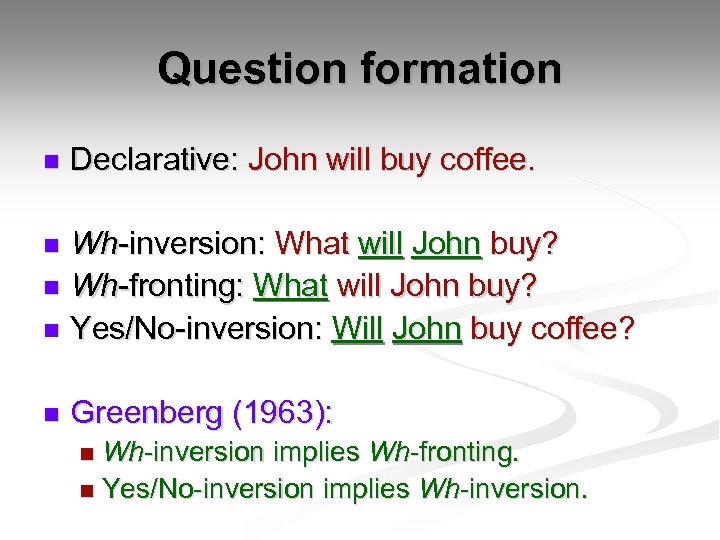

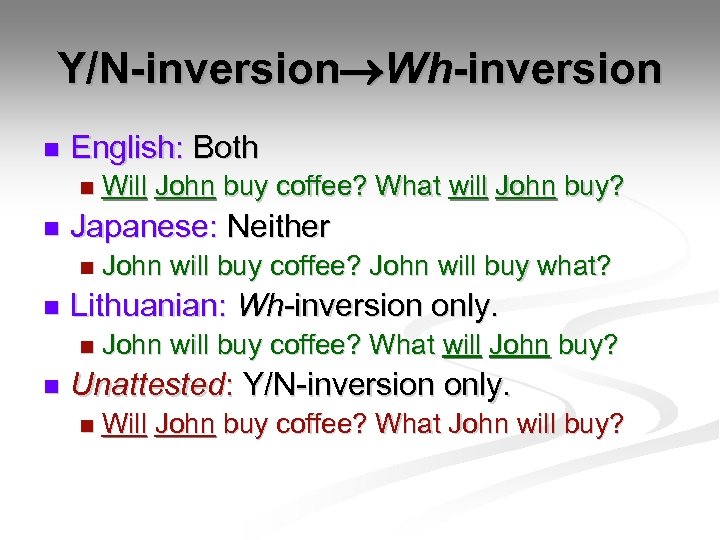

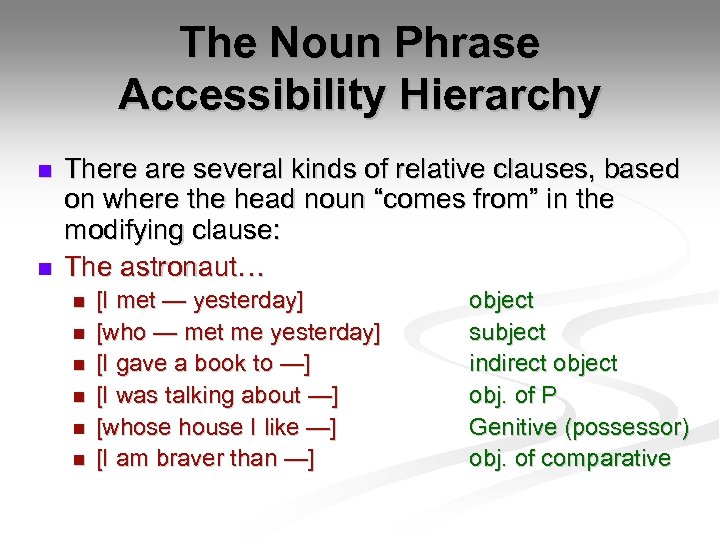

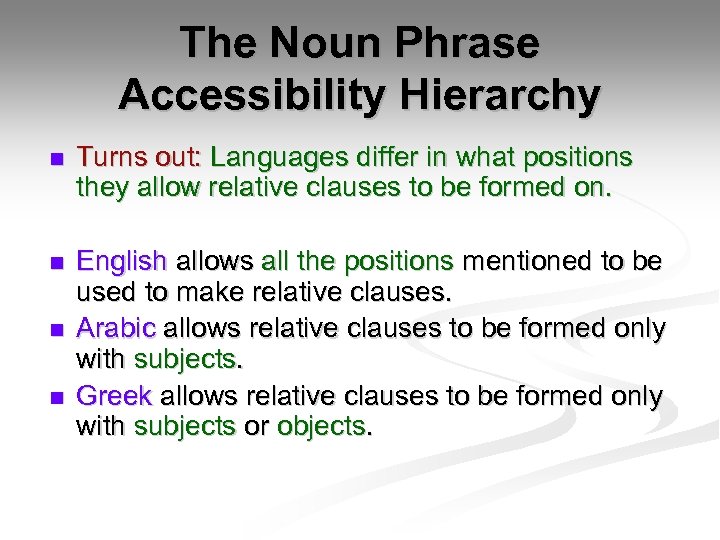

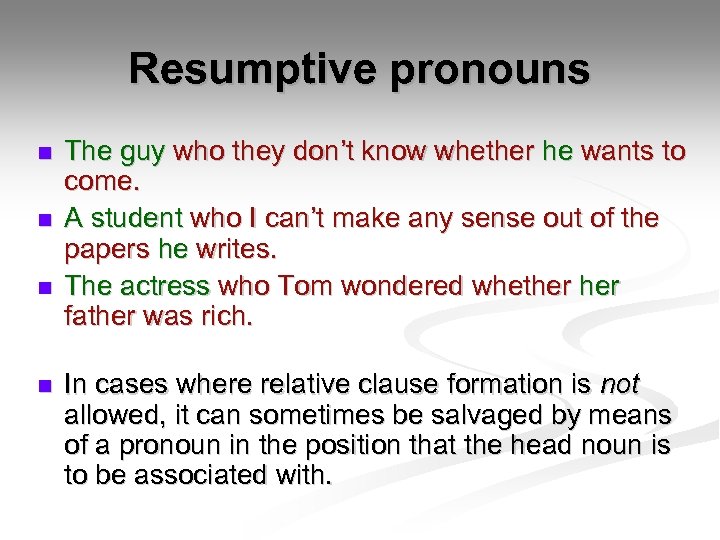

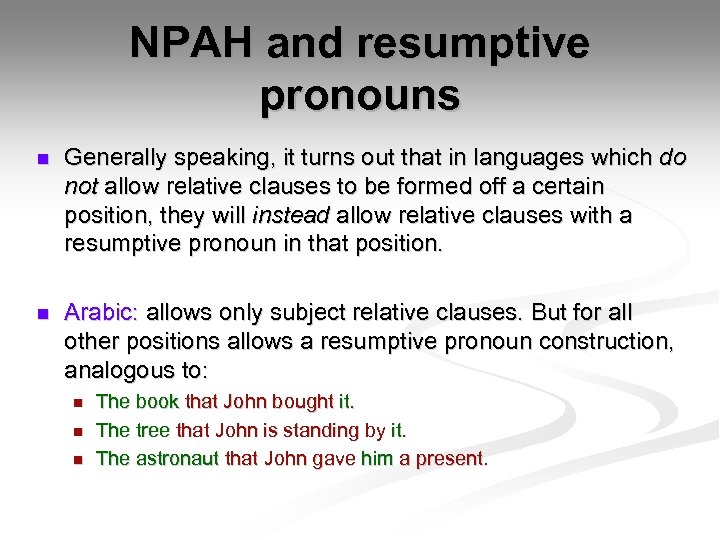

Question formation n Declarative: John will buy coffee. Wh-inversion: What will John buy? n Wh-fronting: What will John buy? n Yes/No-inversion: Will John buy coffee? n n Greenberg (1963): Wh-inversion implies Wh-fronting. n Yes/No-inversion implies Wh-inversion. n

Question formation n Declarative: John will buy coffee. Wh-inversion: What will John buy? n Wh-fronting: What will John buy? n Yes/No-inversion: Will John buy coffee? n n Greenberg (1963): Wh-inversion implies Wh-fronting. n Yes/No-inversion implies Wh-inversion. n

Wh-inversion Wh-fronting n English, German: Both. n n Japanese Korean: neither. n n John will buy what? Finnish: Wh-fronting only. n n What will John buy? What John will buy? Unattested: Wh-inversion only. n *Will John buy what?

Wh-inversion Wh-fronting n English, German: Both. n n Japanese Korean: neither. n n John will buy what? Finnish: Wh-fronting only. n n What will John buy? What John will buy? Unattested: Wh-inversion only. n *Will John buy what?

Y/N-inversion Wh-inversion n English: Both n n Japanese: Neither n n John will buy coffee? John will buy what? Lithuanian: Wh-inversion only. n n Will John buy coffee? What will John buy? John will buy coffee? What will John buy? Unattested: Y/N-inversion only. n Will John buy coffee? What John will buy?

Y/N-inversion Wh-inversion n English: Both n n Japanese: Neither n n John will buy coffee? John will buy what? Lithuanian: Wh-inversion only. n n Will John buy coffee? What will John buy? John will buy coffee? What will John buy? Unattested: Y/N-inversion only. n Will John buy coffee? What John will buy?

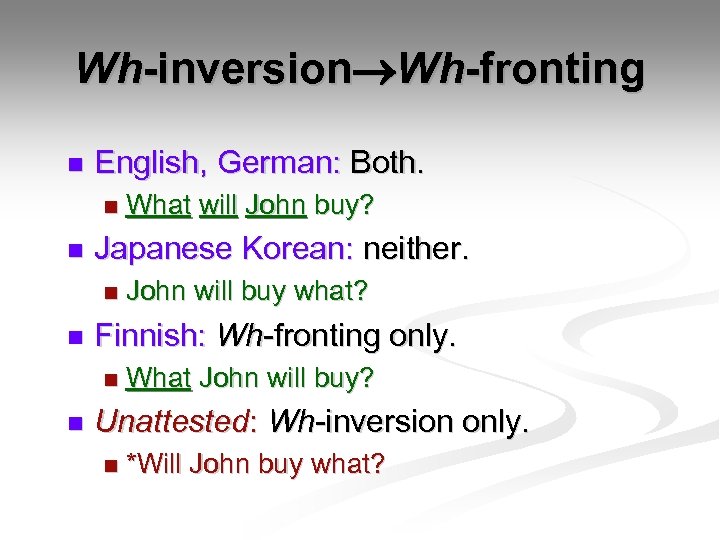

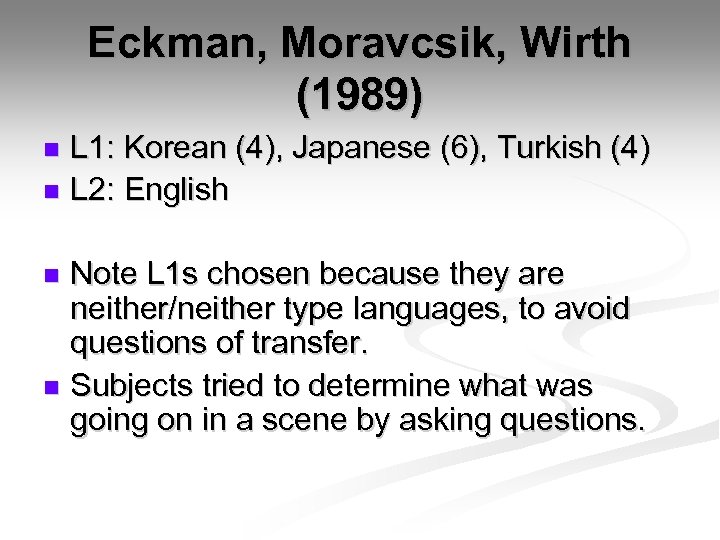

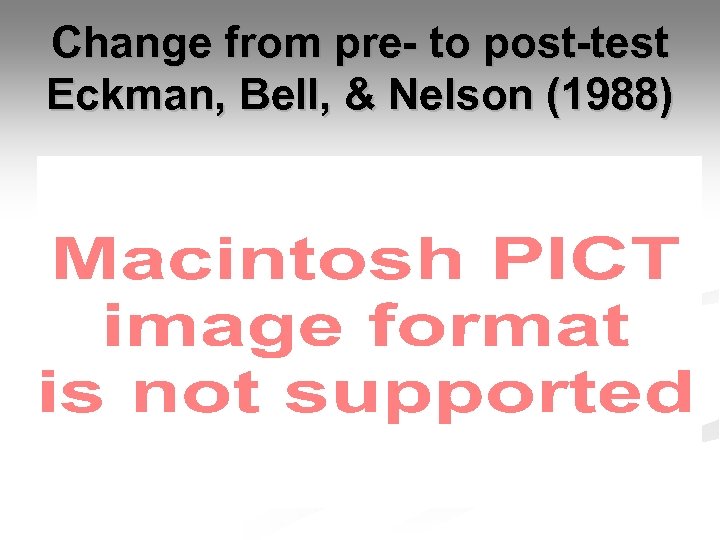

Eckman, Moravcsik, Wirth (1989) L 1: Korean (4), Japanese (6), Turkish (4) n L 2: English n Note L 1 s chosen because they are neither/neither type languages, to avoid questions of transfer. n Subjects tried to determine what was going on in a scene by asking questions. n

Eckman, Moravcsik, Wirth (1989) L 1: Korean (4), Japanese (6), Turkish (4) n L 2: English n Note L 1 s chosen because they are neither/neither type languages, to avoid questions of transfer. n Subjects tried to determine what was going on in a scene by asking questions. n

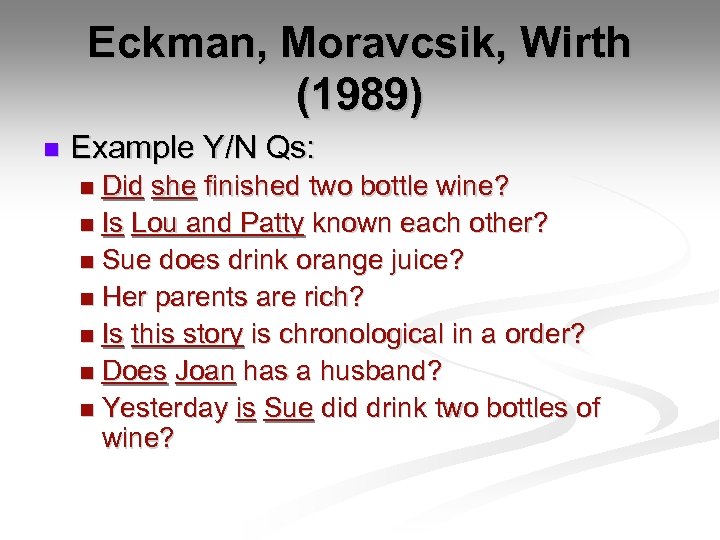

Eckman, Moravcsik, Wirth (1989) n Example Y/N Qs: Did she finished two bottle wine? n Is Lou and Patty known each other? n Sue does drink orange juice? n Her parents are rich? n Is this story is chronological in a order? n Does Joan has a husband? n Yesterday is Sue did drink two bottles of wine? n

Eckman, Moravcsik, Wirth (1989) n Example Y/N Qs: Did she finished two bottle wine? n Is Lou and Patty known each other? n Sue does drink orange juice? n Her parents are rich? n Is this story is chronological in a order? n Does Joan has a husband? n Yesterday is Sue did drink two bottles of wine? n

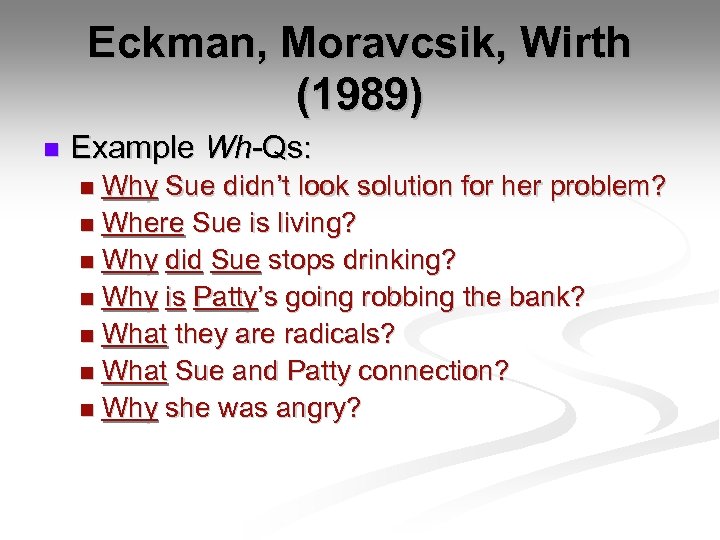

Eckman, Moravcsik, Wirth (1989) n Example Wh-Qs: Why Sue didn’t look solution for her problem? n Where Sue is living? n Why did Sue stops drinking? n Why is Patty’s going robbing the bank? n What they are radicals? n What Sue and Patty connection? n Why she was angry? n

Eckman, Moravcsik, Wirth (1989) n Example Wh-Qs: Why Sue didn’t look solution for her problem? n Where Sue is living? n Why did Sue stops drinking? n Why is Patty’s going robbing the bank? n What they are radicals? n What Sue and Patty connection? n Why she was angry? n

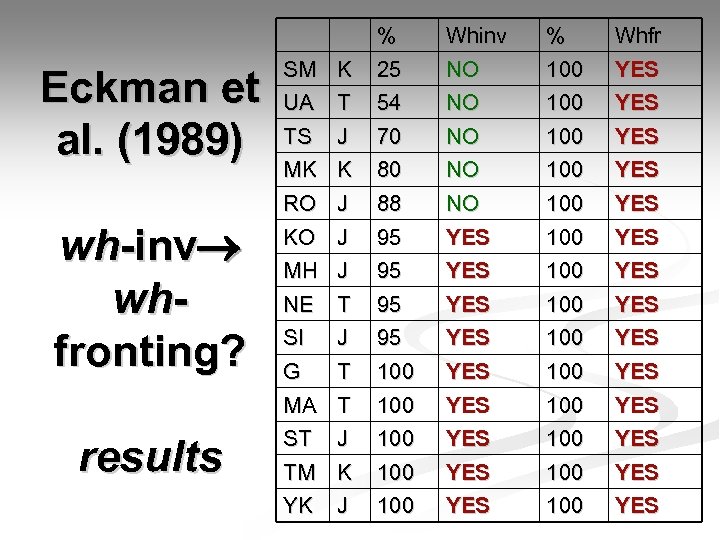

Eckman et al. (1989) wh-inv whfronting? results SM K UA T TS J MK K RO J KO J MH J NE T SI J G T MA T ST J TM K YK J % 25 Whinv NO % 100 Whfr YES 54 70 NO NO 100 YES 80 88 NO NO 100 100 YES YES 95 95 YES YES 100 100 YES YES 100 YES

Eckman et al. (1989) wh-inv whfronting? results SM K UA T TS J MK K RO J KO J MH J NE T SI J G T MA T ST J TM K YK J % 25 Whinv NO % 100 Whfr YES 54 70 NO NO 100 YES 80 88 NO NO 100 100 YES YES 95 95 YES YES 100 100 YES YES 100 YES

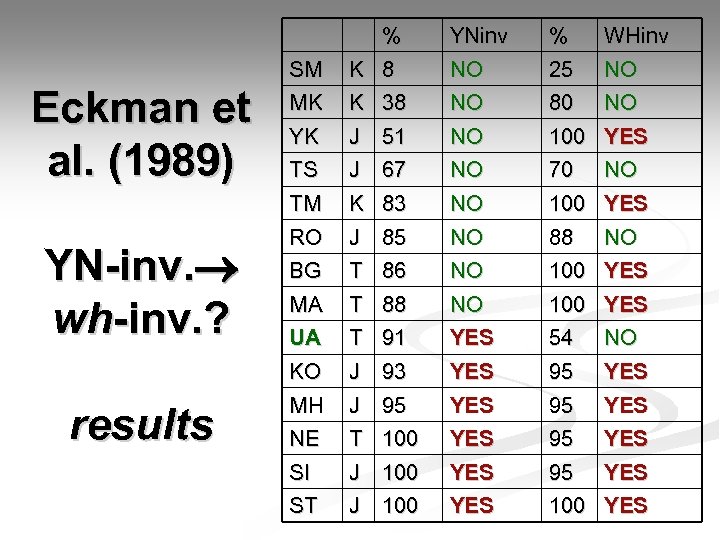

Eckman et al. (1989) YN-inv. wh-inv. ? results SM MK YK TS TM RO BG MA UA KO MH NE SI ST % K 8 K 38 J 51 J 67 K 83 J 85 T 86 T 88 T 91 J 93 J 95 T 100 J 100 YNinv NO % 25 NO NO 80 NO 100 YES 70 NO NO NO YES YES YES WHinv NO 100 YES 88 NO 100 YES 54 NO 95 YES 95 YES 100 YES

Eckman et al. (1989) YN-inv. wh-inv. ? results SM MK YK TS TM RO BG MA UA KO MH NE SI ST % K 8 K 38 J 51 J 67 K 83 J 85 T 86 T 88 T 91 J 93 J 95 T 100 J 100 YNinv NO % 25 NO NO 80 NO 100 YES 70 NO NO NO YES YES YES WHinv NO 100 YES 88 NO 100 YES 54 NO 95 YES 95 YES 100 YES

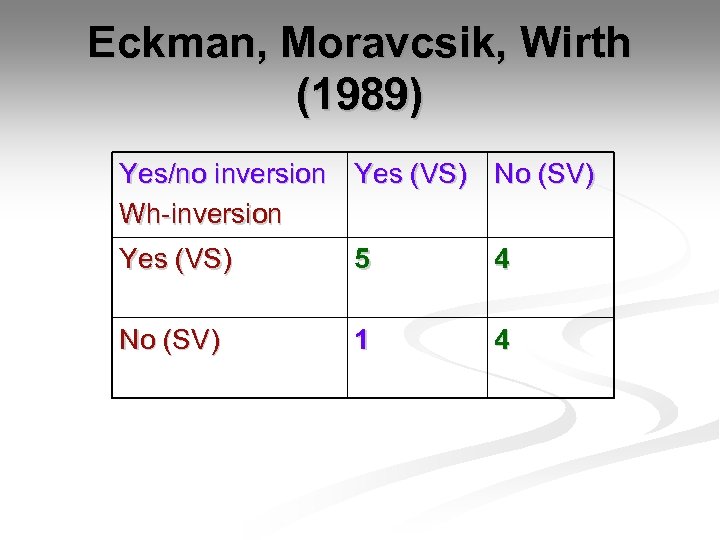

Eckman, Moravcsik, Wirth (1989) Yes/no inversion Yes (VS) No (SV) Wh-inversion Yes (VS) 5 4 No (SV) 1 4

Eckman, Moravcsik, Wirth (1989) Yes/no inversion Yes (VS) No (SV) Wh-inversion Yes (VS) 5 4 No (SV) 1 4

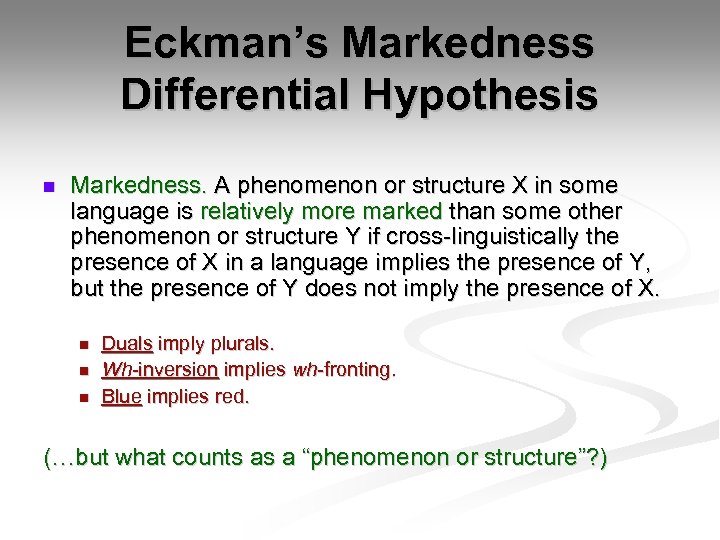

Eckman’s Markedness Differential Hypothesis n Markedness. A phenomenon or structure X in some language is relatively more marked than some other phenomenon or structure Y if cross-linguistically the presence of X in a language implies the presence of Y, but the presence of Y does not imply the presence of X. n n n Duals imply plurals. Wh-inversion implies wh-fronting. Blue implies red. (…but what counts as a “phenomenon or structure”? )

Eckman’s Markedness Differential Hypothesis n Markedness. A phenomenon or structure X in some language is relatively more marked than some other phenomenon or structure Y if cross-linguistically the presence of X in a language implies the presence of Y, but the presence of Y does not imply the presence of X. n n n Duals imply plurals. Wh-inversion implies wh-fronting. Blue implies red. (…but what counts as a “phenomenon or structure”? )

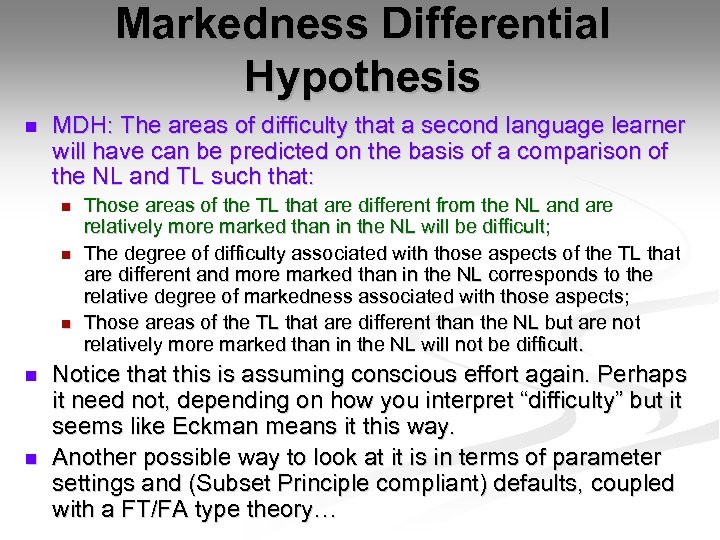

Markedness Differential Hypothesis n MDH: The areas of difficulty that a second language learner will have can be predicted on the basis of a comparison of the NL and TL such that: n n n Those areas of the TL that are different from the NL and are relatively more marked than in the NL will be difficult; The degree of difficulty associated with those aspects of the TL that are different and more marked than in the NL corresponds to the relative degree of markedness associated with those aspects; Those areas of the TL that are different than the NL but are not relatively more marked than in the NL will not be difficult. Notice that this is assuming conscious effort again. Perhaps it need not, depending on how you interpret “difficulty” but it seems like Eckman means it this way. Another possible way to look at it is in terms of parameter settings and (Subset Principle compliant) defaults, coupled with a FT/FA type theory…

Markedness Differential Hypothesis n MDH: The areas of difficulty that a second language learner will have can be predicted on the basis of a comparison of the NL and TL such that: n n n Those areas of the TL that are different from the NL and are relatively more marked than in the NL will be difficult; The degree of difficulty associated with those aspects of the TL that are different and more marked than in the NL corresponds to the relative degree of markedness associated with those aspects; Those areas of the TL that are different than the NL but are not relatively more marked than in the NL will not be difficult. Notice that this is assuming conscious effort again. Perhaps it need not, depending on how you interpret “difficulty” but it seems like Eckman means it this way. Another possible way to look at it is in terms of parameter settings and (Subset Principle compliant) defaults, coupled with a FT/FA type theory…

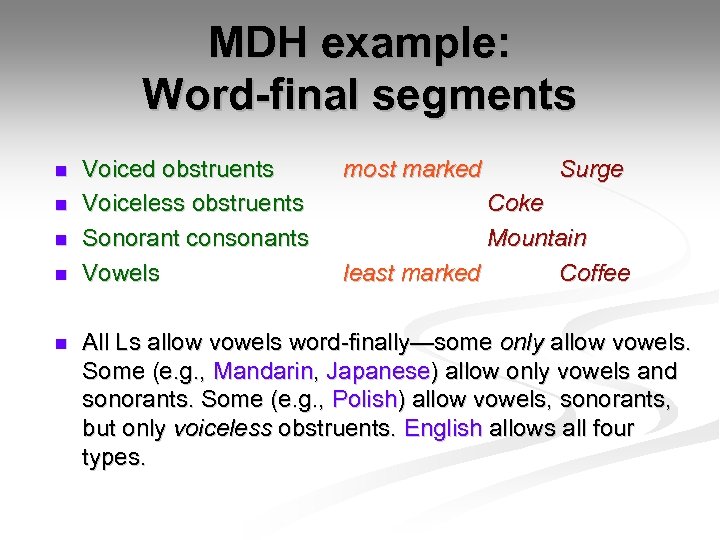

MDH example: Word-final segments n n n Voiced obstruents Voiceless obstruents Sonorant consonants Vowels most marked Surge Coke Mountain least marked Coffee All Ls allow vowels word-finally—some only allow vowels. Some (e. g. , Mandarin, Japanese) allow only vowels and sonorants. Some (e. g. , Polish) allow vowels, sonorants, but only voiceless obstruents. English allows all four types.

MDH example: Word-final segments n n n Voiced obstruents Voiceless obstruents Sonorant consonants Vowels most marked Surge Coke Mountain least marked Coffee All Ls allow vowels word-finally—some only allow vowels. Some (e. g. , Mandarin, Japanese) allow only vowels and sonorants. Some (e. g. , Polish) allow vowels, sonorants, but only voiceless obstruents. English allows all four types.

![Eckman (1981) e e IL form [b p] [b bi] [r t] [w t] Eckman (1981) e e IL form [b p] [b bi] [r t] [w t]](https://present5.com/presentation/547bbabcf705468c4a92e5802b4490cb/image-98.jpg) Eckman (1981) e e IL form [b p] [b bi] [r t] [w t] [s. Ik] Mandarin L 1 Gloss IL form Tag [tæg ] And [ænd ] Wet [w t] Deck [d k] Letter [l t r] Bleeding [blid. In] e e c c e Spanish L 1 Gloss Bobby Red Wet Sick

Eckman (1981) e e IL form [b p] [b bi] [r t] [w t] [s. Ik] Mandarin L 1 Gloss IL form Tag [tæg ] And [ænd ] Wet [w t] Deck [d k] Letter [l t r] Bleeding [blid. In] e e c c e Spanish L 1 Gloss Bobby Red Wet Sick

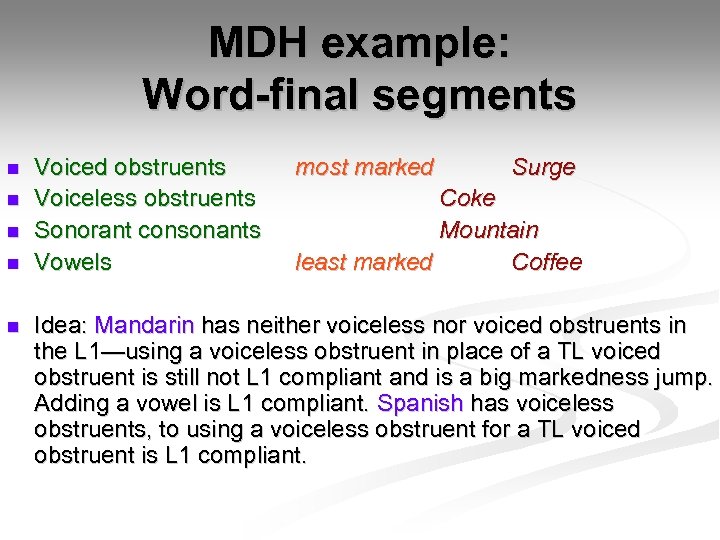

MDH example: Word-final segments n n n Voiced obstruents Voiceless obstruents Sonorant consonants Vowels most marked Surge Coke Mountain least marked Coffee Idea: Mandarin has neither voiceless nor voiced obstruents in the L 1—using a voiceless obstruent in place of a TL voiced obstruent is still not L 1 compliant and is a big markedness jump. Adding a vowel is L 1 compliant. Spanish has voiceless obstruents, to using a voiceless obstruent for a TL voiced obstruent is L 1 compliant.

MDH example: Word-final segments n n n Voiced obstruents Voiceless obstruents Sonorant consonants Vowels most marked Surge Coke Mountain least marked Coffee Idea: Mandarin has neither voiceless nor voiced obstruents in the L 1—using a voiceless obstruent in place of a TL voiced obstruent is still not L 1 compliant and is a big markedness jump. Adding a vowel is L 1 compliant. Spanish has voiceless obstruents, to using a voiceless obstruent for a TL voiced obstruent is L 1 compliant.

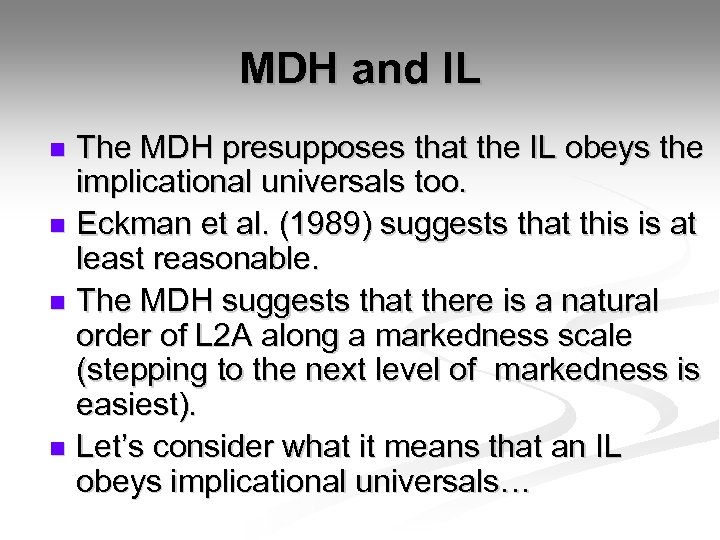

MDH and IL The MDH presupposes that the IL obeys the implicational universals too. n Eckman et al. (1989) suggests that this is at least reasonable. n The MDH suggests that there is a natural order of L 2 A along a markedness scale (stepping to the next level of markedness is easiest). n Let’s consider what it means that an IL obeys implicational universals… n

MDH and IL The MDH presupposes that the IL obeys the implicational universals too. n Eckman et al. (1989) suggests that this is at least reasonable. n The MDH suggests that there is a natural order of L 2 A along a markedness scale (stepping to the next level of markedness is easiest). n Let’s consider what it means that an IL obeys implicational universals… n

MDH and IL n n IL obeys implicational universals. That is, we know that IL is a language. So, we know that languages are such that having word-final voiceless obstruents implies that you also have word-final sonorant consonants, among other things. What would happen if we taught Japanese L 2 learners of English only—and at the outset—voiced obstruents?

MDH and IL n n IL obeys implicational universals. That is, we know that IL is a language. So, we know that languages are such that having word-final voiceless obstruents implies that you also have word-final sonorant consonants, among other things. What would happen if we taught Japanese L 2 learners of English only—and at the outset—voiced obstruents?

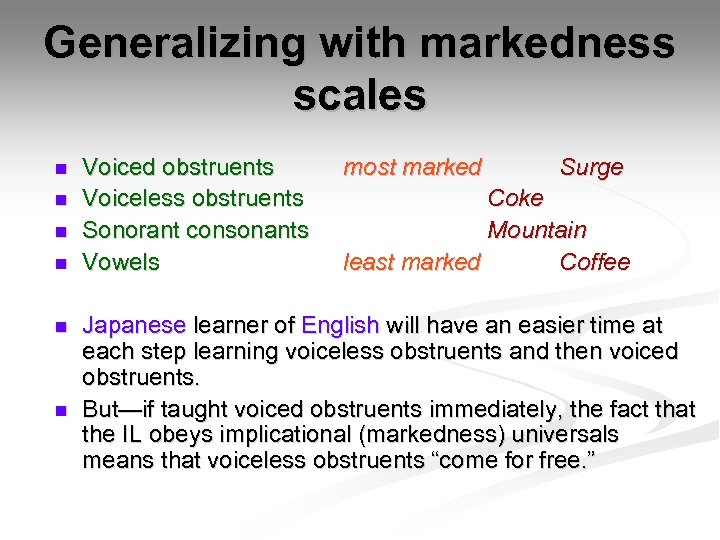

Generalizing with markedness scales n n n Voiced obstruents Voiceless obstruents Sonorant consonants Vowels most marked Surge Coke Mountain least marked Coffee Japanese learner of English will have an easier time at each step learning voiceless obstruents and then voiced obstruents. But—if taught voiced obstruents immediately, the fact that the IL obeys implicational (markedness) universals means that voiceless obstruents “come for free. ”

Generalizing with markedness scales n n n Voiced obstruents Voiceless obstruents Sonorant consonants Vowels most marked Surge Coke Mountain least marked Coffee Japanese learner of English will have an easier time at each step learning voiceless obstruents and then voiced obstruents. But—if taught voiced obstruents immediately, the fact that the IL obeys implicational (markedness) universals means that voiceless obstruents “come for free. ”

Nifty! Does it work? Does it help? n Answers seem to be: n Yes, it seems to at least sort of work. n Maybe it helps. n n Learning a marked structure is harder. So, if you learn a marked structure, you can automatically generalize to the less marked structures, but was it faster than learning the easier steps in succession would have been?

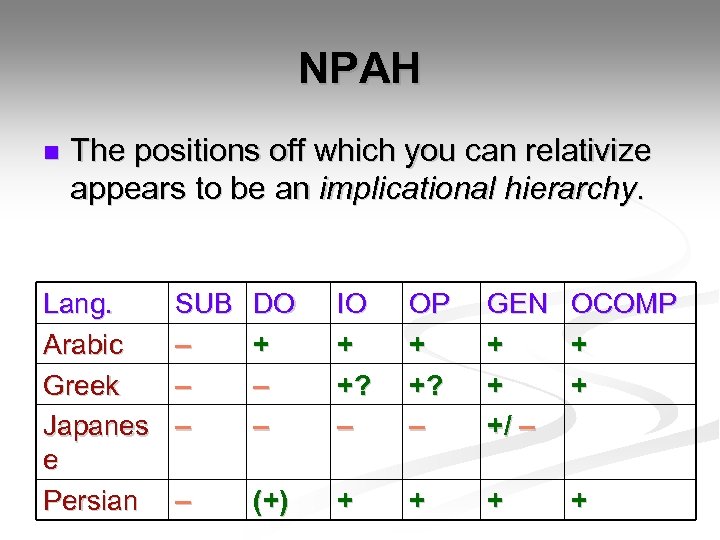

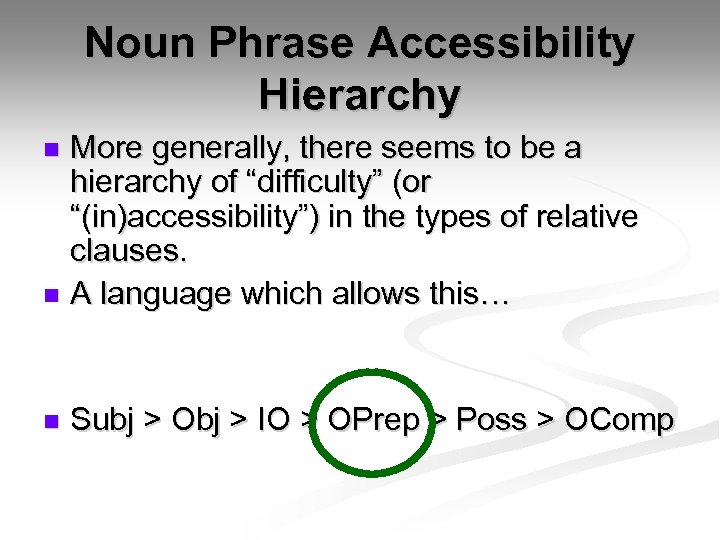

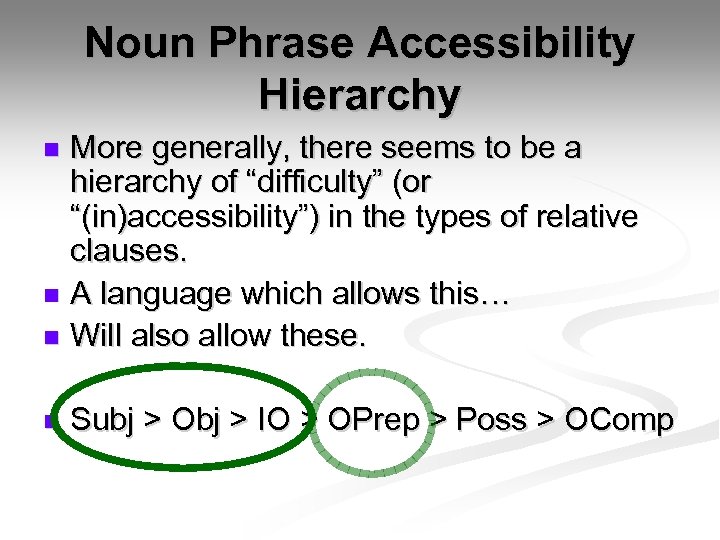

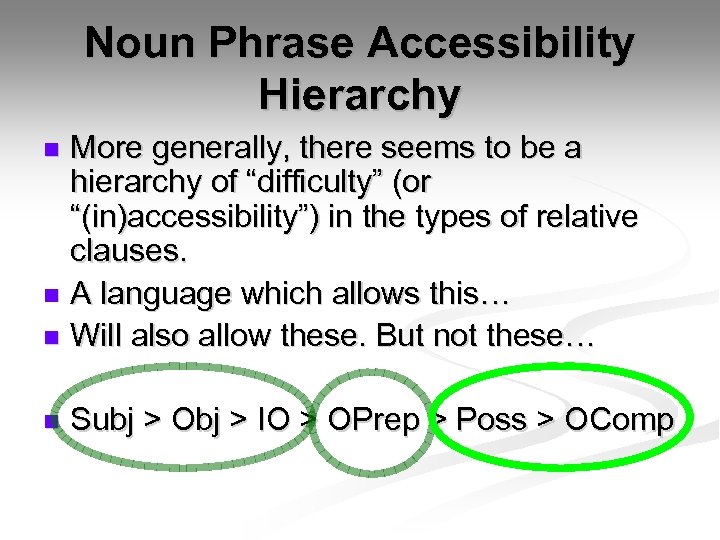

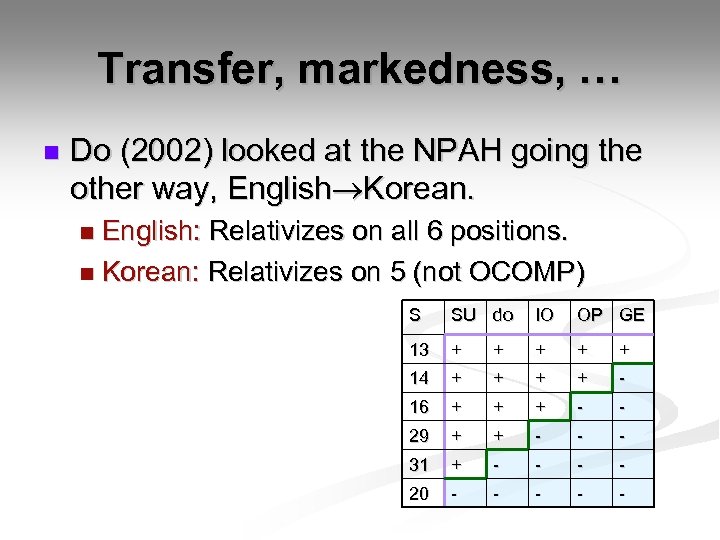

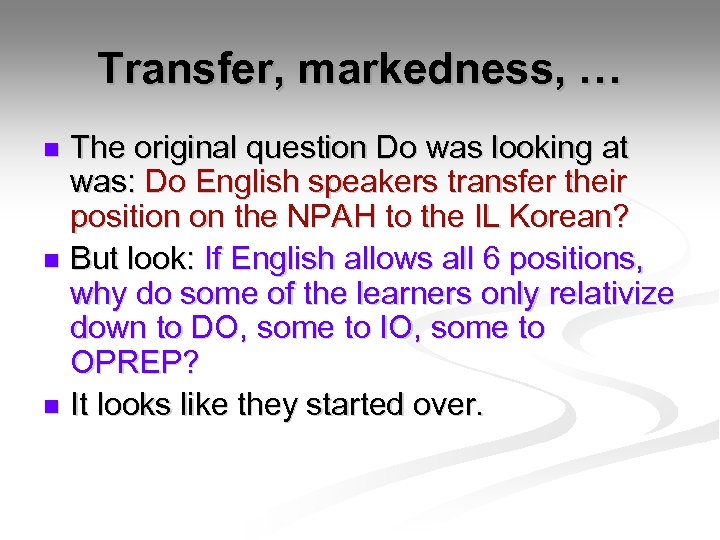

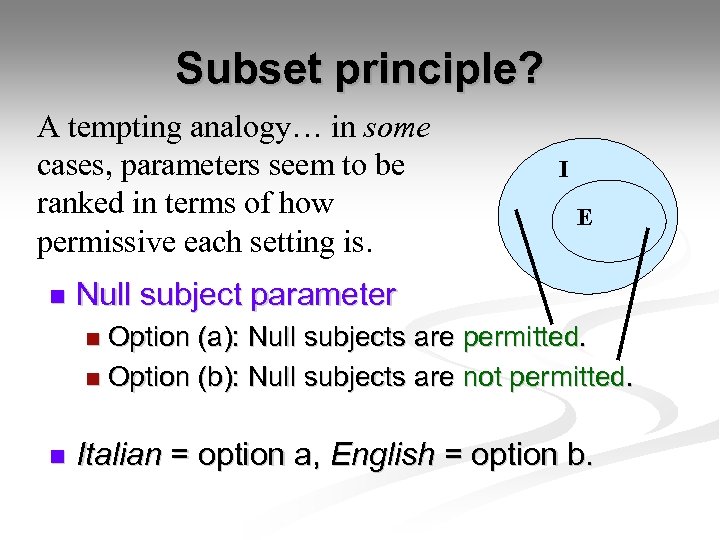

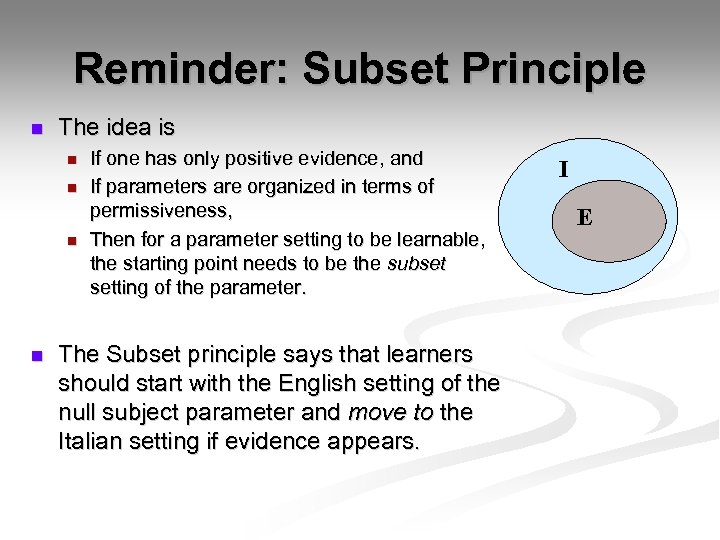

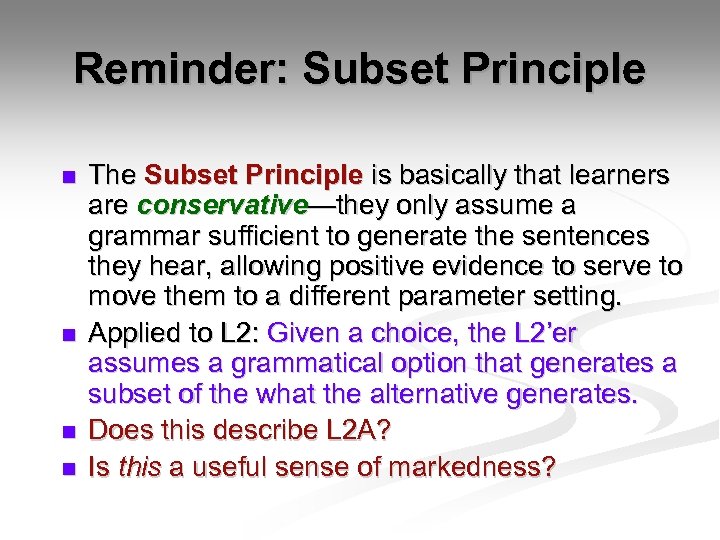

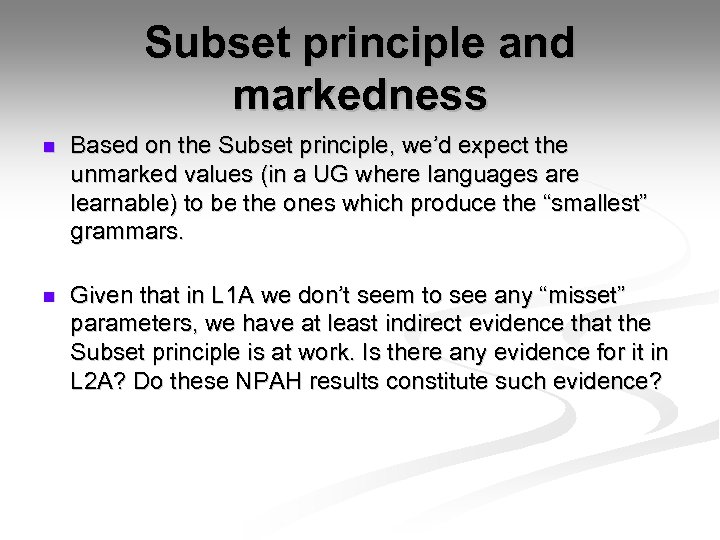

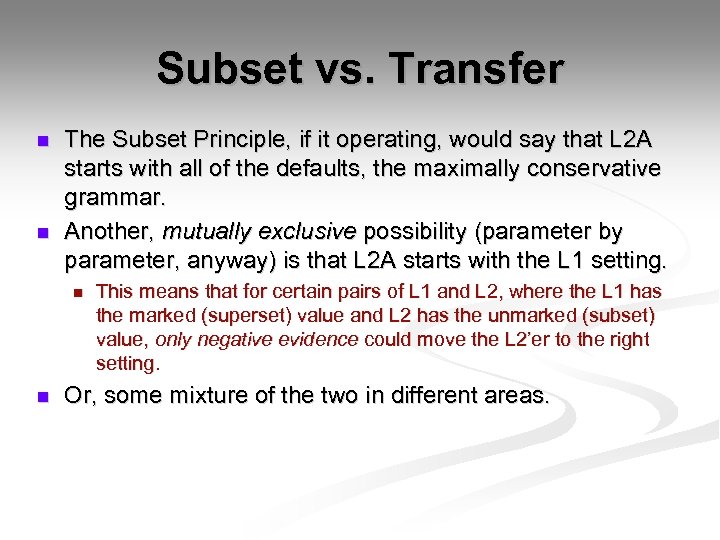

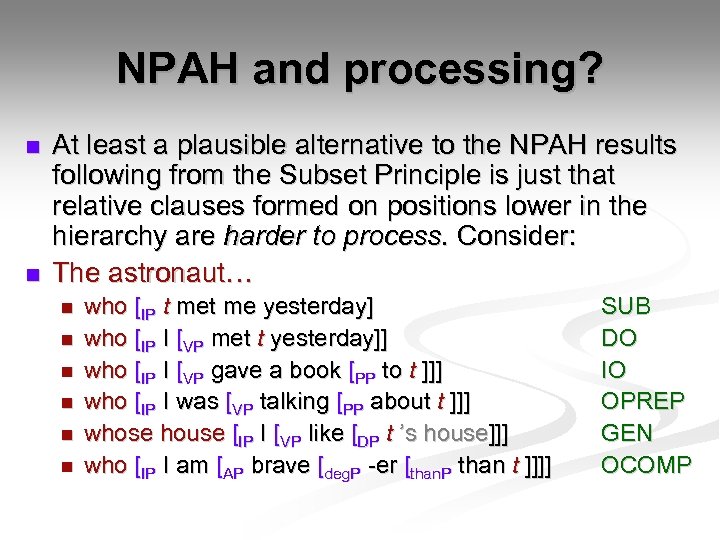

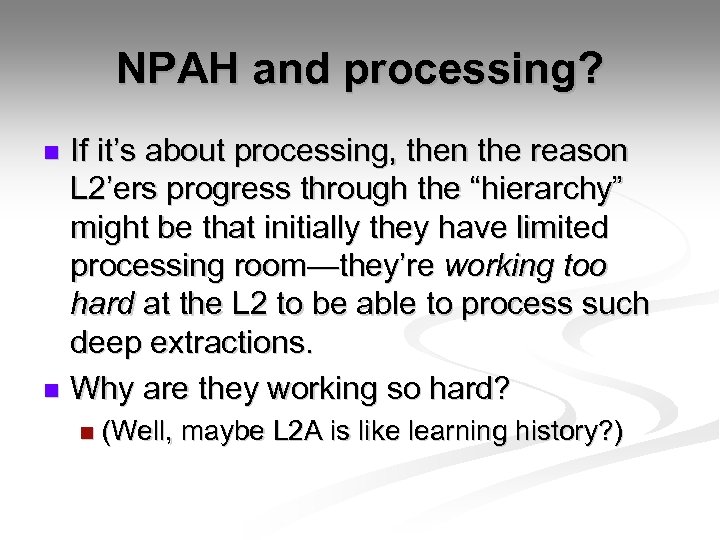

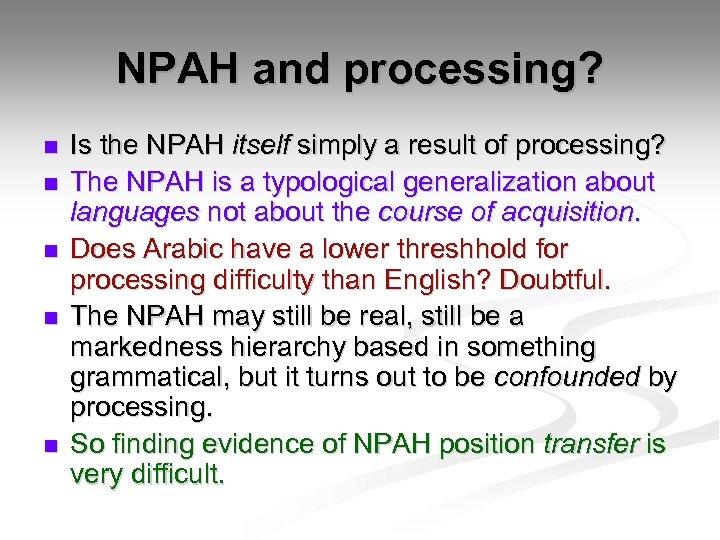

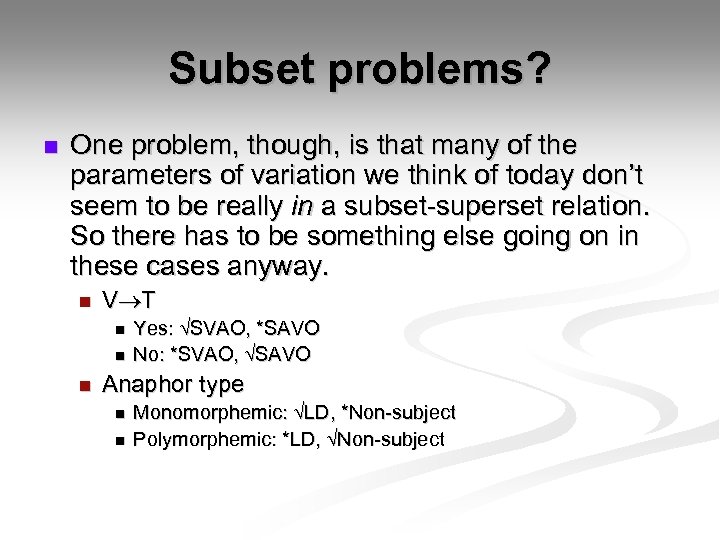

Nifty! Does it work? Does it help? n Answers seem to be: n Yes, it seems to at least sort of work. n Maybe it helps. n n Learning a marked structure is harder. So, if you learn a marked structure, you can automatically generalize to the less marked structures, but was it faster than learning the easier steps in succession would have been?