66cfa4eaef0284ac68c4b714adcb2f49.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 46

Globalisation, Education and Development: The Case of East Asia National University of Tainan 18. 5. 07 Andy Green Institute of Education University of London

Research Project ‘Globalisation, Education and Development’ Funded by DFID (Department for International Development) Published by DFID in May 2007: Green, A. , Little, A. , Kamat, S. , Oketch, M. and Vickers, E. Education and Development in a Global Era: Strategies for ‘Successful Globalisation’

Scope of IOE Project A Review and Synthesis of the Literature on Globalisation, Education and Development with respect to: • • • Education, Globalisation and Economic Development Globalisation, Skills, Qualifications and Livelihoods Education and Social Cohesion Based on: • • General International Literature Specific to China, Kenya, India and Sri Lanka

Aims of Research To assess the role of education in promoting ‘successful’ engagement with the Global Economy. By ‘successful’ we mean ways of engaging with globalization which lead to economic growth with: • • • Reduction in Poverty Increasing income equality Social Improvements (including greater social cohesion) Growth with Equity

The Importance of Globalisation – understood as the rapid acceleration of cross-border movements of good, labour capital services, information and ideas – Changes the terms of development

Theories of globalisation and development There are many theories of globalisation: • • • Hyper-globalisation theory (Ohmae et al) Sceptics (Hirst and Thompson) Transformationalists (Held) How you view globalisation will determine how you view the possibilities for development.

Different emphases 1: Convergence or divergence? 1. 2. If you view globalisation as an inevitable, linear, convergent and uncontradictory process of dissemination of free market capitalism then there is only one road for development (Washington consensus model). 2. If you view it as contradictory and uneven then alternative modes of development are conceiveable.

Different emphases 2: Role of the state 1. If you see the role of the national state under globalisation as increasingly marginalised then the state has a limited role in development – best to leave the markets to work without state intervention and just give aid (Sachs) 2. If on the other hand you regard states as important to development (‘failed states’ as hindering/’developmental states as promoting) then you are likely to judge the role of the state as highly important.

The Contradictions of Globalisation is an uneven, contingent and contradictory process, creating greater global wealth but also increasing global inequality in the distribution of wealth. Some Regions (Europe, North America, and East Asia) have clearly benefited more from global engagement than others (such as Latin America and SSA)

‘Successful gobalisation’ Because globalisation is contradictory and uneven and state-dependent there are different possible responses to it. ‘Success’ in engaging with the global market depends on the : Terms of engagement which each country can achieve. Some countries are able to negotiate better terms than others

Globalisation and Development • Changes the nature of world markets and what it takes to be competitive in them • Changes the nature of the national state and the relations between states and other levels of governance • Alters the possible paths of development

Globalisation is changing the dynamics of development In terms of the factors promoting economic development globalisation increases the importance of : • international trade (and thus the need for exportoriented economies) • Knowledge, skills and technology transfer for development in the global ‘knowledge economy. ’ • MNCs and FDI in knowledge and technology transfer • education and skills (as argued in endogenous growth theory)

The Conditions for ‘Late Development’ (Amsden) ‘Late industrialising countries’ countries can develop more rapidly in a global era due to: • the global disaggregation of production and services industries – the global division of labour • Increased possibilities for knowledge and technology transfer from: - increased investment flows - increasing codification of knowledge and skills - advances in ICT

The Role of Education can play major role in promoting successful engagement with the global economy by six key processes: • • • Providing skills which attract inward investment Assisting in knowledge and technology transfer Upgrading the economy Reducing inequality Promoting social cohesion Strengthening state capacity

The East Asian. Case(s) East Asian economies have proved to be exceptional in negotiating favourable terms of engagement with the global economy. Partly because of the role education has played in promoting the six key processes.

East Asian Development 1960 -1990: The East Asian Miracle East Asian economic growth between 1960 and 1990 was the fastest on record for any region It took Britain 58 years to double real pc income after 1780 USA: 47 years from 1839 Japan 34 years from 1900 Korea: 11 years from 1966 In 1960 S. Korea’s GDP equalled Sudan’s and Taiwan’s Zaire. (Morris, 1995). These are now

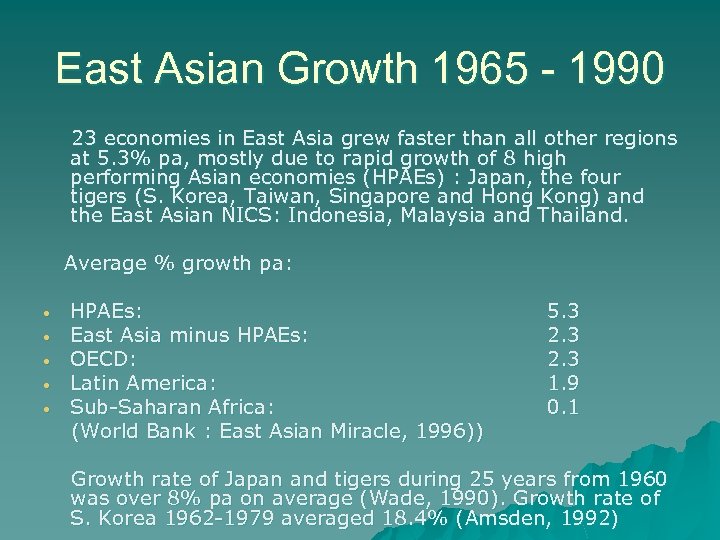

East Asian Growth 1965 - 1990 23 economies in East Asia grew faster than all other regions at 5. 3% pa, mostly due to rapid growth of 8 high performing Asian economies (HPAEs) : Japan, the four tigers (S. Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong) and the East Asian NICS: Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. Average % growth pa: • • • HPAEs: East Asia minus HPAEs: OECD: Latin America: Sub-Saharan Africa: (World Bank : East Asian Miracle, 1996)) 5. 3 2. 3 1. 9 0. 1 Growth rate of Japan and tigers during 25 years from 1960 was over 8% pa on average (Wade, 1990). Growth rate of S. Korea 1962 -1979 averaged 18. 4% (Amsden, 1992)

Growth, Distribution and Well Being • Between 1960 and 1998 real income pc in Japan and tigers increased x 4 • Life Expectancy in HPAEs grew from 56 years in 1960 to 71 in 1990 • Proportions living in absolute poverty declined between 1960 and 1990 from 58% to 17% in Indonesia and from 37% to 5% in Malaysia (compared with 54% to 43% in India) • HPEAs also achieved low and often declining levels of income inequality, particularly in Japan and Taiwan but also, until the 1980 s, in S. Korea and Singapore.

Explanations of Rapid and Equal Development Rapid Development in East Asia is, to some extent, a regional phenomenon. Explanations have focused on: • • Culture Geopolitics Timing Policies (including education)

Culture Cultural explanations of EA development include theories about ‘Confucian’ Capitalism: • • • Strong states and Confucian paternalism Mobilization of national identity Family Basis for Welfare Use of Diasporas and Flying Geese pattern Importance of Education However, theories are generally insufficient to explain dynamics and timing of development • East Asia is highly diverse in ethnicity and religion • Culture cannot explain why now

The Importance of Geography and Geo-Politics • • • Proximity to sea lanes and historic trade routes Advantages of island peninsular states – coastal towns Cold War stimulus to investment US and British investment high in Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan through period of Korean and Vietnam wars. Between 1953 and 1958 US aid to Korea was 15% of GDP and war requisitioning helped to kick start the Chaebols. Singapore benefited from UK and US requisitioning. Up to 50% of finance for Taiwan’s infrastructure in early years came from US aid Geopolitics can only be part of the story. Some states which benefited did not develop (Philippines) and others (Malaysia, Thailand) developed rapidly later, without similar levels of cold war investment.

Timing The timing for the first wave of East Asian growth (second phase for Japan) was highly propitious. • • Buoyant global economy in 1960 s Flexible trade regimes US cuts in Japanese imports helped tigers Conditions for rapid growth now less good Slower world economic growth More NIC competitors WTO limitations to trade policies which arguably helped tigers Globalisation restricts use of capital controls which may also have helped tigers

Factors favouring egalitarian development • Weakening of old landed and Zaibatsu elites in Japan as result of WW 2 and subsequent land reform • Land reform in 1950 s in Taiwan and S. Korea (prompted by US!) redistributed landed wealth and removed antimodernising elites • Agricultural improvements in EA states with agricultural economies reduced disparities or rural and urban incomes • Rapid improvement in access to education reduced growth inequalities (countering the usual Kuznets effect) • Developmental states overcame entrenched class interests? • Redistributional policies of governments ie Malaysia pro Malay business policy, Singapore and Hong Kong Housing programmes etc

Policy Explanations of Growth • Neo-classical economics • Market friendly neo-classical economics (WB East Asian Miracle) • Developmental state theory (Amsden, Wade, Johnson etc)

Neo-Classical theory Neo-classical economic explanations argue that East Asian states got the basics right and left the rest to the market: • Private domestic investment and rapidly increasing human capital were principal engines of growth • High domestic savings sustained high investment (typically savings at over 30% of income) • Increased agricultural productivity • Effective public administration • Good macro-economic management (low inflation and borrowing; stable exchange rates etc • Openness to trade • Export led growth

Developmental State theorists DST does not disagree with view that human capital and investment were important and that export led growth was central. However, they argue that the conventional account ignores the degree of state intervention in growth and the use of ‘neo-mercantilist’ policies which deviated very substantially from ‘free trade. ’ With the exception of Hong Kong, Japan and the tigers all had highly state-led development programmes. They developed at a much faster rate than the Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand

The Crucial Role of the State Britain, America, Germany, France all used a strong state for development through national economies in early stages of growth. Free Trade Policies only favour the strong and even then have only been applied selectively. Alexander Gerschenkron noted the key role of the state in ‘late development. ’ Under globalisation there has generally been huge capital flows from the South to the North except in East Asia ‘where the state is powerful enough to to control capital flight and direct the economy efficiently. ’ Naom Chomsky

Developmental Paths Each country followed similar development path: • • import substitution and agricultural improvement (late fifties) export of cheap manufactured goods (early sixties) (textiles; toys; shoes etc) based on low cost labour development of capital intensive goods (late sixties /early seventies) (variously Steel, Shipbuilding; Petro chemicals etc) and electronic consumer goods shift to higher value added manufacturing (1980 s) Singapore and Hong Kong relied heavily on FDI since they had small domestic markets and little domestic capital Japan, Korea and Taiwan initially prefered foreign loans and technology transfer through licensing but gradually moved towards allowing joint ventures and since 1997 foreign MNCs. Korea copied Japan - large private conglomerates working closely with state bureaucracy as engines of growth. Taiwan maintained larger SME sector but created many state owned large companies.

Developmental Policies in Japan and Tigers A range of policies used to stimulate economic growth: To protect home industries: • Tariffs and import quotas to protect infant industries • Tariffs, protectionist standards regulations and high taxes on luxury and other goods to discourage unnecessary consumption, encourage saving and to allow exporting manufacturers to reclaim losses on marked down foreign sales through high domestic prices. To encourage exports: • Export subsidies; export targets; preferential loans for exporters; tariff reduction on imported inputs for exporters; low exchange rates (which helped exporter); export processing Zones

Developmental Policies in Japan and Tigers 2 Industrial Policy – building up priority sectors through: • • Preferential loans for companies to develop in certain sectors Directing credit through Gov’t banks or regulation on private banks Encouraging sector rationalisation through forcing market exit or forced mergers of failing companies. Tax subsidies and infrastructural development for R and D in favoured sectors. To Encourage FDI • Setting up one-stop-shop of Economic Development Boards in Singapore and Korea To encourage savings • • Post Office Saving Accounts (Japan and S. Korea) Mandatory providential fund savings (CPF in Singapore)

Effects of Interventions Most economists agree that market-governing measures were widely used in Japan and three tigers in first stage of development although countries later liberalised. The argument is about what effect the interventions they had. Neo-classical economists say growth would have happened anyway without these policies. Developmentalists say they were generally beneficial to growth and key to success. All agree that pre-conditions for market governing intervention working was that: • • • Firms were forced to remain competitive Interventions were carefully monitored so that subsidies removed from firms not achieving Measures required competent and honest bureaucracy.

Role of Education General view : education played major role in East Asian Miracle WB from growth accounting estimates: ‘far and away the major difference in predicted growth rates between HPAEs and sub. Saharan Africa derives from variations in primary school enrolment rates. (EAM p. 54)

Different Theories of Education’s Role Writers on East Asia differ on how they understand the role of education in rapid growth. Three theories: • • • Human capital theory (WB) Developmental Skill Formation (Ashton and Green) Education and State Formation (High skills Project)

Human Capital Account Skills contributed significantly to productivity growth and technology transfer. Educational development was successful because it largely followed the market and was informed ‘sound’ policies: • HPAEs had high initial levels of literacy (although so did Sri Lanka and Philippines in 1960 s) • Investment focused initially on universalising primary education which had highest rate of return • Secondary and higher education were developed sequentially when growth and higher rates of return to higher levels encouraged private investment • Growth, private investment and declining birth rates (earlier and sharper than in other developing countries) allowed increased in per capita spending and higher enrols in education without excessive public cost.

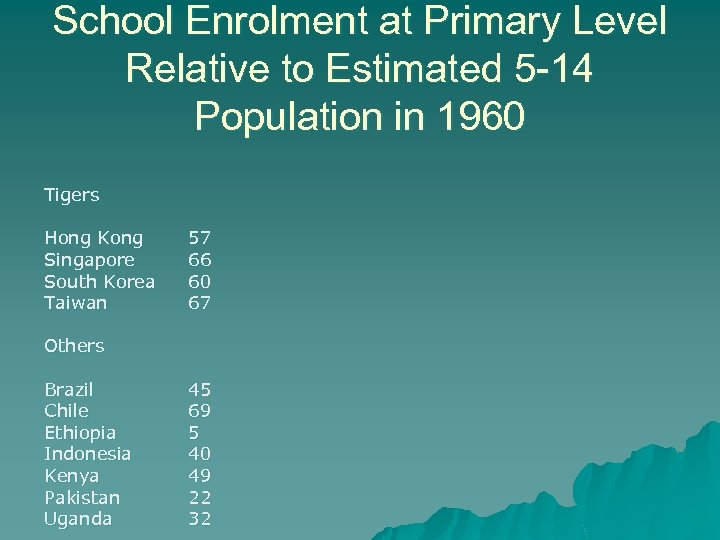

School Enrolment at Primary Level Relative to Estimated 5 -14 Population in 1960 Tigers Hong Kong Singapore South Korea Taiwan 57 66 60 67 Others Brazil Chile Ethiopia Indonesia Kenya Pakistan Uganda 45 69 5 40 49 22 32

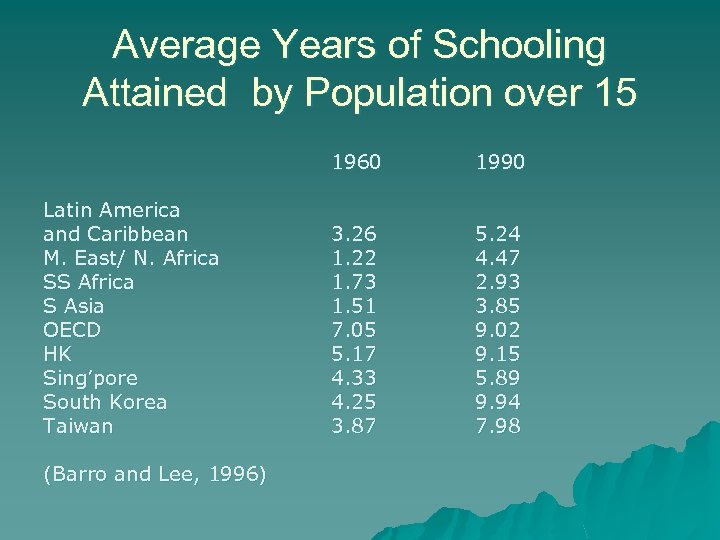

Average Years of Schooling Attained by Population over 15 1960 Latin America and Caribbean M. East/ N. Africa SS Africa S Asia OECD HK Sing’pore South Korea Taiwan (Barro and Lee, 1996) 1990 3. 26 1. 22 1. 73 1. 51 7. 05 5. 17 4. 33 4. 25 3. 87 5. 24 4. 47 2. 93 3. 85 9. 02 9. 15 5. 89 9. 94 7. 98

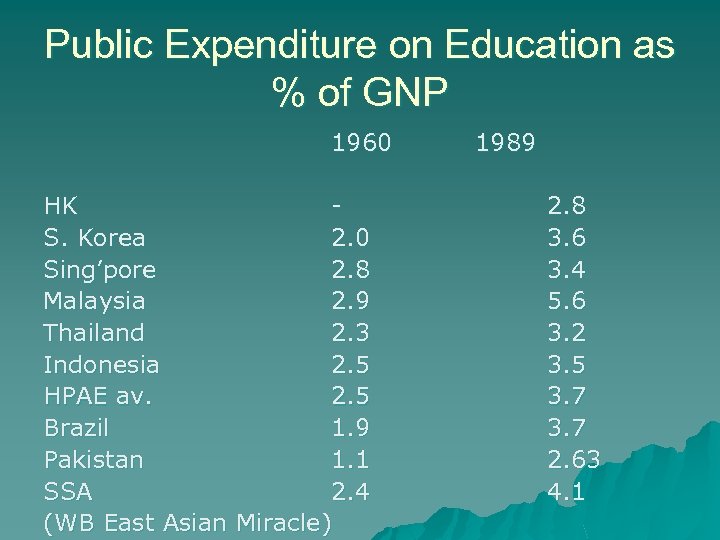

Public Expenditure on Education as % of GNP 1960 HK S. Korea 2. 0 Sing’pore 2. 8 Malaysia 2. 9 Thailand 2. 3 Indonesia 2. 5 HPAE av. 2. 5 Brazil 1. 9 Pakistan 1. 1 SSA 2. 4 (WB East Asian Miracle) 1989 2. 8 3. 6 3. 4 5. 6 3. 2 3. 5 3. 7 2. 63 4. 1

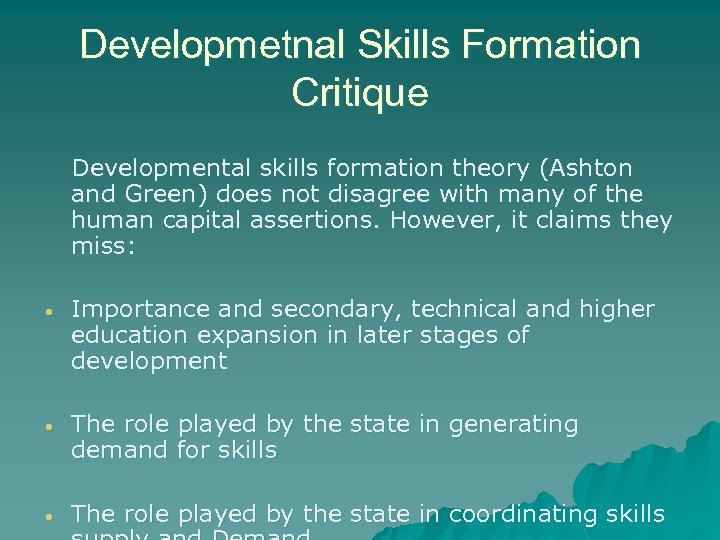

Developmetnal Skills Formation Critique Developmental skills formation theory (Ashton and Green) does not disagree with many of the human capital assertions. However, it claims they miss: • Importance and secondary, technical and higher education expansion in later stages of development • The role played by the state in generating demand for skills • The role played by the state in coordinating skills

State intervention to increase the demand for skills • Through industrial policy to increase investment in high value added industries • Through forcing MNCs to bring in more capital and skills intensive operations The classic example was the Singapore strategy for skills upgrading in 1980 s

Second Industrial Revolution in Singapore Gary Rodan describes Singapore efforts in early 1980 s to shift to a high skill economy when it could no longer compete with NICs on low cost manufacture. • Substantial increase in minimum wages • Tax subsidies to MNCs for hi-tech investment • Introduction of Skills Development Fund financed from a levy on employers of 2% of wage costs for all workers S$750 or less pm • Encouraging MNCs not wanting to upgrade to exit Strategy quite successful in increasing high value-added production in Singapore but had to be aborted in mid 1980 s when labour costs rose to uncompetitive level.

Coordinating Supply and Demand • Using manpower planning through high level interministerial strategy committees (CPTE in S’pore) • Setting quotas for enrolments in Secondary and HE (S. Korea, Taiwan and S Korea till 1980) according to forward industrial planning • Revising these when needed • Brokering deals with MNCs (Singapore through EDB) to provide skills and for MNCs to provide training abroad and set up joint training centres in Singapore. French, Japanese and German technical institutes set up jointly with government. • Upgrading technical education rapidly in line with planned economic strategy (setting up of ITE in early 1970 s in Singapore)

Broader Contribution of Education to Development Education in Japan and the Tigers has contributed to development in various ways: • • • Through provision of skills Through inculcation of work discipline (one days leave a month in Korean factories in 1960 s!) Through socialisation into ‘survival’ national ideologies which have helped maintain political stability Through popularising meritocratic ideology that encouraged endeavour Through other educational policies designed to enhance equality and social cohesion

Commonalities of East Asian Schooling East Asian education and training systems differ in some significant ways: • Japan, Taiwan and Korea are highly egalitarian (Non-selective neighbourhood comprehensive schools; mixed ability classes; equal resource distribution between school) – Singapore and Hong Kong are comparatively elitist • Japan and Korea have extensive company based training in large firms. Singapore relies much more heavily on Gov’t funded workforce development • However, they have a number of features in common (Cumings)

Commonalities of East Asian Schooling • • Highly centralised administration (although this is beginning to change now) Major stress on dissemination of basic skills Bias towards Maths and Engineering (20% get maths A level in Sing’pore and 40% of graduates are engineers) Major stress on Moral and Civic education (made possible by centralised control)

Benefits and Costs of Education Bias to Maths and Engineering • Has served growing manufacturing economy well • Has also produced competent civil servants (In Singapore they say engineers make best civil servants) However, lack of creative education has not necessarily been good for producing creative and entrepreneurial talents. Singapore compensates for this by importing foreign talent, but all Japan and tigers all now complain of lack of creative skills in leading edge science and business innovation.

Importance of Socialisation Arguably the most important contribution of education to economic development in Japan and Tigers has been through effective youth socialisation • Encouraging disciplined attitudes to hard work • Generating ‘national spirit’ of struggle and sacrifice in early generation (to encourage saving and effort and acceptance of overpriced consumer goods etc). Koreans went en mass to pubic collection centres to hand over their silverware during the economic crisis! Japanese have put up with over -priced Japanese rice for years because they have been convinced it is patriotic! • Creating ability to work in teams (more notable in Japan and Korea than Singapore perhaps)

66cfa4eaef0284ac68c4b714adcb2f49.ppt