9552246bbe2adae42c9b5aa7bcae6338.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 18

Global Media Analysts Asia Pacific Europe North America South America The Romano Prodi Government – a review of media opinion

The scope of coverage analysed • CARMA included 371 articles within its research • All articles that appeared between 17 th May 2006 and 3 rd December 2006 within the following opinionforming media titles were included in the analysis (providing they included at least two relevant mentions of Romano Prodi): UK Pan Europe US

The Prodi story

CARMA’s conclusion 1: A Challenging Legacy • Romano Prodi returned as Prime Minister of Italy in May of this year. His appointment was not heralded with as much gusto as perhaps meets other new key European leaders, as the somewhat yo-yo nature of Italian politics means that the media do not necessarily see the selection of a new Prime Minister in Italy as something particularly novel or newsworthy. Angela Merkel, for instance, generated around twice as many articles in her first week of office as did Romano Prodi in his. • That Prodi was taking over a country with problems (especially economic) was widely recognised. Under Silvio Berlusconi, Italy had seen its economy worsen, and corruption allegations abounded. • Not surprisingly, the media have been keen to see how the Prodi government may fare against these challenges, and how the nine-party coalition approaches the tasks at hand. The coverage Prodi generates is often, therefore, on stories which can demonstrate his progress or, more frequently, his political woes, to good effect. • The Telecom Italia story – which included discussions on the proposals regarding the sale of its mobile phone arm – has been the single-most covered story to date. It is as if this news provided the media with the perfect exemplification of the challenging and vulnerable position in which Romano Prodi finds himself as the Prime Minister of Italy. It illustrates how Signor Prodi is stuck in the middle of opposing forces: he needs to improve Italy’s economic position and also maintain the ideology of a former president of the EU, but he also does not want to alienate those on the left of his very fragile coalition by going against their protectionist instincts. • The possibility of Telecom Italia being taken over by a foreign investor was therefore an event that was watched with great interest, as it seemed to be viewed as a crucial test of which side Prodi would take. Would he be a moderniser, or would he be shackled to his left-wing (Communist) past? • Negative opinion on this matter grew as the government’s interfering with a private company’s deal signified an old-style Italian political charade.

CARMA’s conclusion 2: An Unconvincing Reformist • Only 6% of articles that have mentioned Prodi since his latest appointment as Prime Minister contain mention of corruption, and a number of these mention the topic only in relation to Silvio Berlusconi. • This represents a significant decrease in the incidence of an Italian Prime Minister being discussed alongside corruption, as during 14% of articles during Berlusconi’s last time in office mentioned corruption in some form. Indeed, corruption allegations continue to dog Signor Berlusconi even now (the David Mills case in particular, in the UK). • Corruption is not represented as being so integral within the Prodi government as it was within the Berlusconi/Forza Italia leadership. There are only two key stories in which Prodi is, in a minor way, aligned to corrupt practices: the amnesty of prisoners (and subsequent fears of greater mafia activity), and the Telecom Italia leak. Furthermore, Prodi was not drawn into discussion regarding Italy’s big corruption scandal of 2006 – the collusion of the country’s big football clubs with match officials in influencing the outcome of matches. • This distancing from the issue of corruption does not appear to be particularly beneficial to Signor Prodi, however, in securing his position as a strong and effective leader for Italy. The lack of solid resolve or action in terms of reforms (particularly economic) has seen confidence in the coalition deteriorate. The press had their suspicions confirmed that Prodi does not have the political power to bring about the changes that are muchneeded by Italy’s economy. • In only a matter of months after his appointment, the media are already speculating about the collapse of his coalition. • As rumours surface about possible desertions of centre-left factions within the government, there is a feeling of inevitability with respect to the cessation of his tenure. Though this is a reflection of what the media view as a weak coalition and leadership, there is also an historical aspect that makes a short-lived government in Italy a seemingly preordained phenomena.

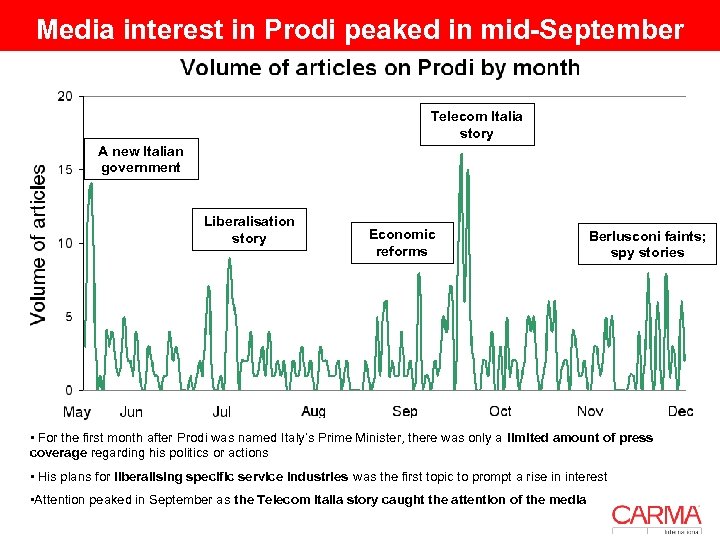

Media interest in Prodi peaked in mid-September Telecom Italia story A new Italian government Liberalisation story Economic reforms Berlusconi faints; spy stories • For the first month after Prodi was named Italy’s Prime Minister, there was only a limited amount of press coverage regarding his politics or actions • His plans for liberalising specific service industries was the first topic to prompt a rise in interest • Attention peaked in September as the Telecom Italia story caught the attention of the media

A new leadership and a huge challenge ahead • The challenge faced by Romano Prodi upon his appointment as Prime Minister was generally regarded as a mighty task, with Italy’s political landscape seemingly always been beset with problems: “[There are] several characteristics of post-war Italy: revolving-door governments over several decades, chronic inefficiency, self-doubt linked to the enduring economic gulf between north and south, and the corruption inherent in governance long based on a system of patronage” (International Herald Tribune, 30 August) • Silvio Berlusconi’s legacy was often viewed with limited respect, with recognition that in 2005, the debt to GDP ratio increased for the first time in a decade, to 106 per cent. • During his term, Berlusconi and corruption were often talked about in the same breath, and there was no sign that the media considered the new government to be above such activities, as in The Economist’s reaction to the appointment of Clemente Mastella as justice minister: “He is utterly unsuitable. More than once, he has chided prosecutors for their impertinent curiosity about political corruption. Only three months ago he was questioned at the headquarters of the national anti-Mafia directorate about his friendship with a man who admitted to helping the Sicilian Cosa Nostra's former ‘boss of bosses’, Bernardo Provenzano” (20 May) • Of perhaps greatest concern to the media, though, was the nature of Prodi’s coalition – a paper-thin majority and an amalgam of many different parties with differing ideologies. “More than five weeks after the tense Italian elections that his ill-assorted coalition won only by a whisker-fine margin, Romano Prodi has wrenched and wrestled a Cabinet into position. Whether it is capable of governing Italy is an open question” (The Times, 19 May) Mr. Prodi will have to proceed with extreme caution in order to not upset the fragile balance within his governing coalition, which ranges from centrist Catholics to hard-core communists. ” (Wall Street Journal Europe, 17 May) “Back in power but with a fractious coalition” (The Times, 18 May)

A precarious beginning, but couldn’t be worse than Berlusconi • The precariousness of Signor Prodi’s position has continued to be a feature of reporting throughout his leadership. The virtues of a nine-party coalition is viewed with suspicion. Of key concern is that commercial ventures may suffer owing to the myriad viewpoints within the coalition, particularly those coming from the Communist element : “Already burdened by a tiny majority in the Senate, rising opposition from Italy's powerful labour unions and a bickering coalition government, Mr Prodi needs all the support he can get” (Wall Street Journal Europe, 31 July) “He indicates that this time coalition weakness may be a strength. ‘I think you deal better with nine parties [than two]’ he says. ‘You can more easily have the role of mediation, of setting the path, the direction’…Machiavelli, updated for 2006” (Wall Street Journal Europe, 20 November 2006) “Business is worried about the new government's tiny majority in the upper house of parliament, its internal divisions and the strong influence of Communists and former Communists” (The Economist, 8 July) • Despite the lack of confidence in such a divergent coalition, there was some positive opinion regarding the governing team, with finance minister, Tommaso Padao-Schioppa, particularly highlighted as a key member: “The damage done to the economy under Mr Berlusconi is striking…so could this government turn out to be more business-friendly than Berlusconi’s lot? Businessmen are doubtful though they are impressed by the Prodi team’s credentials” (The Economist, 8 July) “Mr Prodi's choice of finance minister is impossible to fault. In preaching orthodox fiscal discipline to keep Italy in the euro, he will also have allies in Mario Draghi, the Bank of Italy governor” (Financial Times, 18 May)

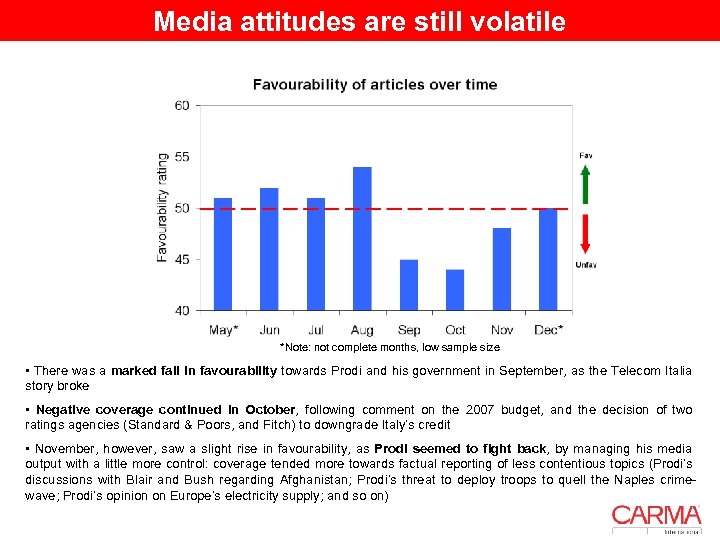

Media attitudes are still volatile *Note: not complete months, low sample size • There was a marked fall in favourability towards Prodi and his government in September, as the Telecom Italia story broke • Negative coverage continued in October, following comment on the 2007 budget, and the decision of two ratings agencies (Standard & Poors, and Fitch) to downgrade Italy’s credit • November, however, saw a slight rise in favourability, as Prodi seemed to fight back, by managing his media output with a little more control: coverage tended more towards factual reporting of less contentious topics (Prodi’s discussions with Blair and Bush regarding Afghanistan; Prodi’s threat to deploy troops to quell the Naples crimewave; Prodi’s opinion on Europe’s electricity supply; and so on)

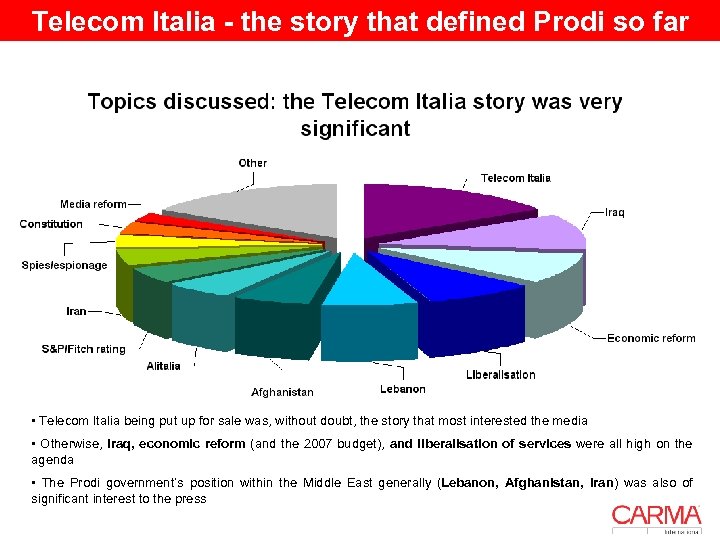

Telecom Italia - the story that defined Prodi so far • Telecom Italia being put up for sale was, without doubt, the story that most interested the media • Otherwise, Iraq, economic reform (and the 2007 budget), and liberalisation of services were all high on the agenda • The Prodi government’s position within the Middle East generally (Lebanon, Afghanistan, Iran) was also of significant interest to the press

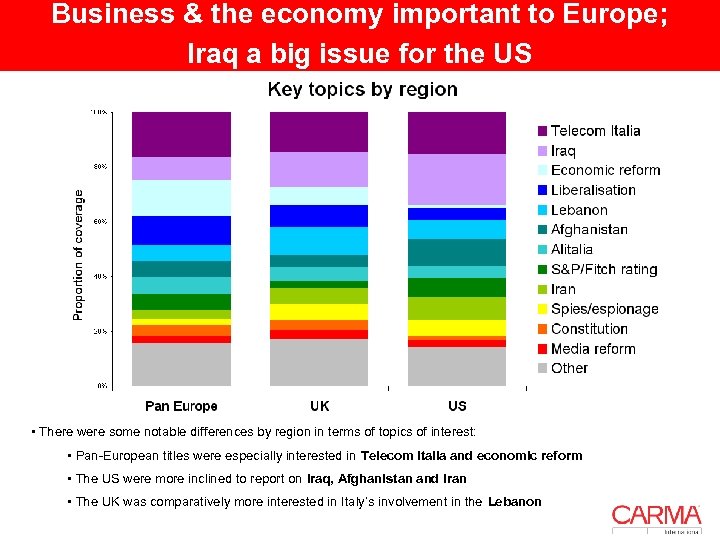

Business & the economy important to Europe; Iraq a big issue for the US • There were some notable differences by region in terms of topics of interest: • Pan-European titles were especially interested in Telecom Italia and economic reform • The US were more inclined to report on Iraq, Afghanistan and Iran • The UK was comparatively more interested in Italy’s involvement in the Lebanon

The economy - a news liability for Prodi • The above chart illustrates the favourability of Prodi when the media talks about him in relation to a number of different topics – outside the line of neutrality is a positive rating, within it is a negative one • He received his most favourable coverage on his policies on or involvement with Iraq and the Lebanon • Among his least favourable press were stories on his economic reforms, Telecom Italia and the drop in S&P/Fitch ratings

And economic reform his most pressing challenge • The need for Italy to make significant and effective economic reforms is universally acknowledged within the media. On this topic, Mr Prodi’s plans and his 2007 budget receive several unfavourable articles. That said, discussion of this topic was largely found within pan-European titles such as the Financial Times, and it is the implementation that often comes under fire, rather than the nature of the reforms themselves. In addition, the vulnerability and fractious nature of the coalition is again a key consideration, as this is seen to be a potential barrier to progression: I “While the proposals have won support from financial markets as a long-overdue effort to clean up Italy’s public finances and introduce structural reforms, the method used to convert them into law has stirred discontent even in Mr Prodi’s coalition” (Financial Times, 3 August) “Mr Prodi had to resort to a confidence vote to pass the measures, highlighting the struggle the new prime minister faces in keeping his fragile center-left coalition united” (Wall Street Journal, 3 August) “’Padoa-Schioppa is a good economist, but he has no political power and so he can't convince the other ministers to accept what he proposes, ’ said Gianfranco Pasquino, a political science professor at the University of Bologna" (International Herald Tribune, 15 November) • Furthermore, there is a sense of sympathy for Mr Prodi, with the Italian economic infrastructure and corruption hard challenges to beat: “[Tax evasion] is a national sport practised no less enthusiastically than football or romance… the centre-right government of Silvio Berlusconi…was well-known for offering amnesties to people engaged in illegal construction work in return for payment of fines” (Financial Times, 26 August) • But this is not necessarily enough to bolster favourable opinion and faith in the coalition to come good on its economic development: “Prodi and his coalition have been pilloried in recent weeks during negotiations for the passage of a budget for 2007 and, as a result, their support has plummeted” ( International Herald Tribune, 27 November)

Telecom Italia: A major Achilles heal • As it was proposed that the mobile arm of Telecom Italia (TIM) might be put up for sale to a foreign investor, there was a significant amount of speculation in the press in terms of how the Prodi government would react. I • The story provided the media with a perfect embodiment of what it is that makes Romano Prodi’s position so fragile. • He has an extremely slim majority and is head of a many-pronged coalition that is varied in its viewpoints. He has also inherited from Silvio Berlusconi a country that has considerable economic challenges that it must face. These problems are seen to culminate in the Telecom Italia story as it provides Signor Prodi with a profound dilemma: should he block foreign investment in order to appease his coalition members and not jeopardise his political position, or should refrain from interfering with outside parties entering the TIM deal, thereby demonstrating that he is open to economic reform, and distancing himself from his traditional far-left roots. • As it happened, Signor Prodi did become involved, and stood accused of meddling in the restructuring plan of the private company, which prompted criticism from several quarters, as well as doubts about the viability of Italy as safe investment. “Evidence suggesting the government had an influential role in the affairs of a quoted company has …raised old doubts about Italy as a destination foreign capital” (The Guardian, 19 September) “Not since he took office in May has Prodi’s government been so vulnerable, and his political foes are seeking a knockout punch” (International Herald Tribune, 29 September) • A further sensation arose as Signor Prodi leaked details of his private conversations with TI CEO, Marco Tronchetti, which revealed confidential information about negotiations with Rupert Murdoch. This was generally regarded negatively by the press, often being judged a wily move that works against Italy’s political development: “To many, this incident stopped reform momentum cold and revealed Mr Prodi to be an heir to Italy's tradition of Catholic Communism” (Wall Street Journal Europe, 20 November)

Liberalisation: a step in the right direction • Coverage on the topic of how the Prodi government plans to open up various industries (such as taxi drivers, pharmacies, law firms and banks) to competition is mostly, at least initially, neutral or positive. Amongst many there is a sense that Signor Prodi is to be admired for tackling the issues (and resistance within his own coalition), and therefore more laudable than his predecessor, Signor Berlusconi: I “He has chosen liberalising reforms that have made many centre-right supporters squirm with regret that the Berlusconi government did not have the guts to take similar action” (Financial Times, 5 July) “Italy’s professional associations are more coddled than in any other EU country, and the previous centreright government left them alone. Mr Prodi, to his credit, if not willing to do so” (Wall Street Journal Europe, 6 July) • Nevertheless, several articles mention the negative reaction of those affected by the reforms. And more recently, there has also been a little consternation that Prodi’s plans haven’t been fully realised: “Taxi drivers were the first to rebel, staging wildcat strikes that brought six days of traffic chaos to cities” (Sunday Times, 9 July) “Almost entirely missing from the mix are the liberalising reforms that Italy urgently needs…He has made some effort to open up competition within Italy’s cossetted professions…the rest – public sector reforms…he says must wait” (The Times, 27 October) “Mr Prodi…started to shake up a sleepy services sector and showed that left-wing rulers can…force through competition in a country where oligopoly is the natural state. But Mr Prodi dropped the ball with that most despised of guilds, the taxi drivers, who struck against his plans to free up their sector and got most of their way” (Wall Street Journal, 18 November)

A not-so-bright future for Romano Prodi? • Though there was no great fanfare when Prodi came into power in May, there were murmurs that his experience as EU president and his talk of reform could bring hope to a troubled Italy. However, the fragility of his majority and the nature of his coalition have been recurrent concerns throughout his leadership. • The limited scope of economic reforms and the unimpressed response to the 2007 budget, as well as the Telecom Italia story, have been damaging to Prodi in terms of the level of support he has received from the pan-European, UK and US press. These have provided apparent confirmation that the Prime Minister’s power to reform is compromised by the current political system, and the nature of the coalition that he heads. • Though his rather shaky position within the coalition is appreciated, his lack of action is largely seen as a weakness – and a weakness which will, in the not-too-distant future, probably lead to his unseating: “By failing to stand up to the enemies of modernisation, Signor Prodi gives the impression that political survival is his only solid goal; and that he is content…to be ‘in office but not in power’” (The Times, 27 October) “The burning question is whether Roman Prodi…has already squandered this opportunity for change…The growing signs of disarray in Mr Prodi’s coalition may mean his days in power are numbered” (Financial Times, 30 October) “Italy…will continue to suffer from a decline in export competitiveness and a further fall in investment and business confidence if the Prodi Government collapses, as it almost surely will” (The Times, 20 November) “The battle over the budget…has exposed conflicts within a coalition that includes free-market liberals, centrist Catholics and two Communist parties. Some analysts predict that the internal divisions will lead to an early collapse of the coalition, leading Italy back to the polls in 2007” (International Herald Tribune, 15 November)

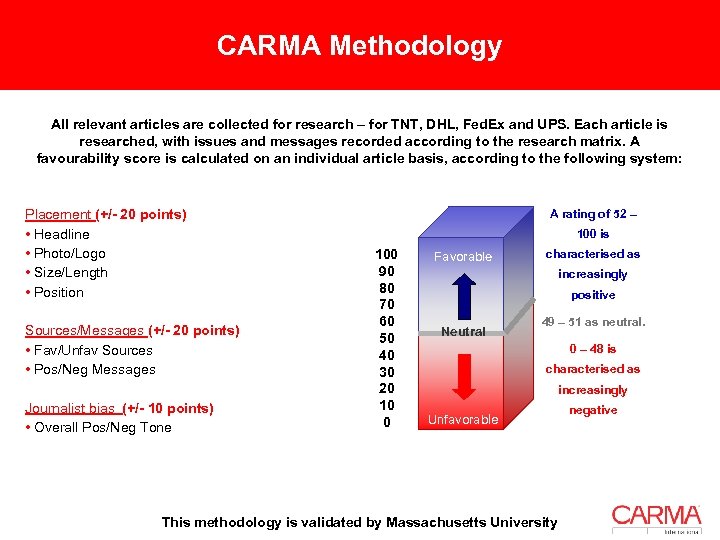

CARMA Methodology All relevant articles are collected for research – for TNT, DHL, Fed. Ex and UPS. Each article is researched, with issues and messages recorded according to the research matrix. A favourability score is calculated on an individual article basis, according to the following system: Placement (+/- 20 points) • Headline • Photo/Logo • Size/Length • Position Sources/Messages (+/- 20 points) • Fav/Unfav Sources • Pos/Neg Messages Journalist bias (+/- 10 points) • Overall Pos/Neg Tone A rating of 52 – 100 is 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Favorable characterised as increasingly positive Neutral 49 – 51 as neutral. 0 – 48 is characterised as increasingly Unfavorable This methodology is validated by Massachusetts University negative

Global Media Analysts Thank you for your time

9552246bbe2adae42c9b5aa7bcae6338.ppt