345a4072c1b04cc61d1ecee581baa83e.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 95

Generative Grammar and Historical Linguistics: what cycles tell us Elly van Gelderen Oslo, 9 August 2013 International Conference on Historical Linguistics XXI

Generative Grammar and Historical Linguistics: what cycles tell us Elly van Gelderen Oslo, 9 August 2013 International Conference on Historical Linguistics XXI

Outline A. Generative (Historical) Linguistics B. The healthy tension between generative grammar and historical linguistics, in both directions C. The Minimalist Program and how it is conducive to looking at gradual, unidirectional change. D. Examples of Linguistic Cycles E. Explanations and some challenges.

Outline A. Generative (Historical) Linguistics B. The healthy tension between generative grammar and historical linguistics, in both directions C. The Minimalist Program and how it is conducive to looking at gradual, unidirectional change. D. Examples of Linguistic Cycles E. Explanations and some challenges.

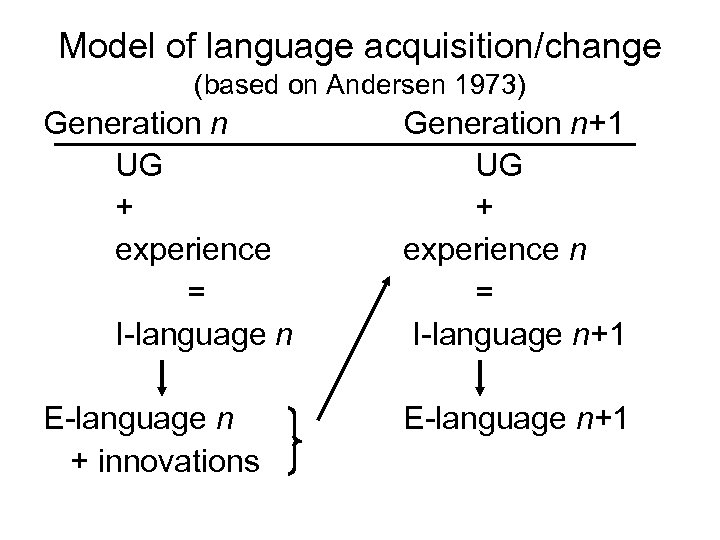

Model of language acquisition/change (based on Andersen 1973) Generation n UG + experience = I-language n E-language n + innovations Generation n+1 UG + experience n = I-language n+1 E-language n+1

Model of language acquisition/change (based on Andersen 1973) Generation n UG + experience = I-language n E-language n + innovations Generation n+1 UG + experience n = I-language n+1 E-language n+1

Internal Grammar

Internal Grammar

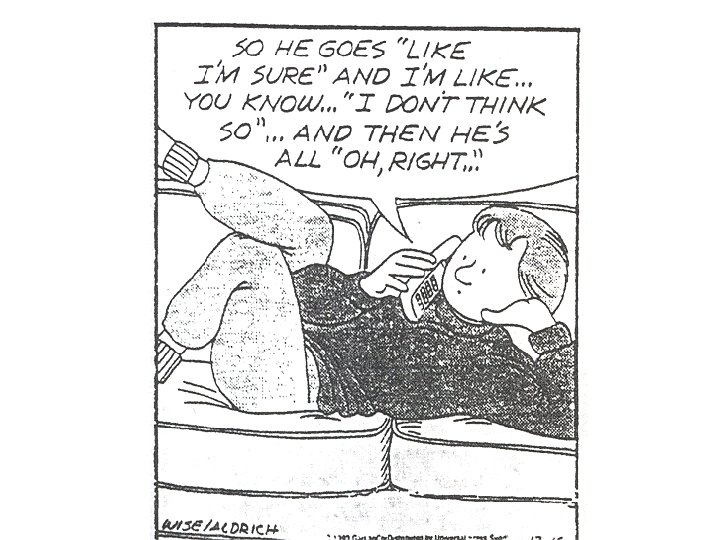

Reanalysis is crucial (1) Paul said, "Starting would be a good thing to do. How would you like to begin? “ (COCA 2010 Fiction) (cartoon is on Handout)

Reanalysis is crucial (1) Paul said, "Starting would be a good thing to do. How would you like to begin? “ (COCA 2010 Fiction) (cartoon is on Handout)

As for the tension: Introspection vs text Generative syntax has typically relied on introspective data. For historical periods, such a method of data gathering is obviously impossible. Generative grammar places much emphasis on the distinction between competence and performance, i. e. on I(nternal)- and E(xternal)-language.

As for the tension: Introspection vs text Generative syntax has typically relied on introspective data. For historical periods, such a method of data gathering is obviously impossible. Generative grammar places much emphasis on the distinction between competence and performance, i. e. on I(nternal)- and E(xternal)-language.

Currently: use of corpora Since the 1990 s, a group of generative linguists has worked on the creation of parsed corpora (see http: //www. ling. upenn. edu/histcorpora/). Result: much better descriptions of changes in the word order (e. g. work by Pintzuk, Haeberli, Taylor, van Kemenade and others), changes in do-support (e. g. Kroch and Ecay), Adverb Placement (Haeberli, van Kemenade, and Los), and pro drop (Walkden). Corpus work has reinvigorated Historical Linguistics.

Currently: use of corpora Since the 1990 s, a group of generative linguists has worked on the creation of parsed corpora (see http: //www. ling. upenn. edu/histcorpora/). Result: much better descriptions of changes in the word order (e. g. work by Pintzuk, Haeberli, Taylor, van Kemenade and others), changes in do-support (e. g. Kroch and Ecay), Adverb Placement (Haeberli, van Kemenade, and Los), and pro drop (Walkden). Corpus work has reinvigorated Historical Linguistics.

And change can be seen as unidirectional and gradual Newmeyer (1998: 237); Roberts & Roussou (2003: 2) and others: “grammaticalization is a regular case of parameter change … [and] epiphenomenal”, i. e. all components also occur independently. Others, e. g. van Gelderen (2004; 2011), argue that the unidirectional patterns that are shown by grammaticalization can be `explained’: the child reanalyzes the input in a certain way. This is where cycles come in!

And change can be seen as unidirectional and gradual Newmeyer (1998: 237); Roberts & Roussou (2003: 2) and others: “grammaticalization is a regular case of parameter change … [and] epiphenomenal”, i. e. all components also occur independently. Others, e. g. van Gelderen (2004; 2011), argue that the unidirectional patterns that are shown by grammaticalization can be `explained’: the child reanalyzes the input in a certain way. This is where cycles come in!

Current internal questions The role of UG: Language-specific or third factor or prelinguistic? The role of features: semantic ones innate?

Current internal questions The role of UG: Language-specific or third factor or prelinguistic? The role of features: semantic ones innate?

Is change gradual or abrupt? Most functionalist explanations assume it is gradual whereas many formal accounts think it is abrupt. Early generative approaches emphasize a catastrophic reanalysis of both the underlying representation and the rules applying to them. Lightfoot, for instance, argues that the category change of modals is an abrupt one from V to AUX, as is the change from impersonal to personal verbs (the verb lician changing in meaning from `please’ to `like’).

Is change gradual or abrupt? Most functionalist explanations assume it is gradual whereas many formal accounts think it is abrupt. Early generative approaches emphasize a catastrophic reanalysis of both the underlying representation and the rules applying to them. Lightfoot, for instance, argues that the category change of modals is an abrupt one from V to AUX, as is the change from impersonal to personal verbs (the verb lician changing in meaning from `please’ to `like’).

How to see the role of UG? In the 1960 s, UG consists of substantive universals, concerning universal categories (V, N, etc) and phonological features, and formal universals relating to the nature of rules. The internalized system is very language-specific. “[S]emantic features. . . , are presumably drawn from a universal ‘alphabet’” (Chomsky 1965: 142), “little is known about this today”.

How to see the role of UG? In the 1960 s, UG consists of substantive universals, concerning universal categories (V, N, etc) and phonological features, and formal universals relating to the nature of rules. The internalized system is very language-specific. “[S]emantic features. . . , are presumably drawn from a universal ‘alphabet’” (Chomsky 1965: 142), “little is known about this today”.

Principles and Parameters of the 1980 s/1990 s Headedness parameter OV to VO Inventory of Functional Categories C-oriented (V 2) to T-oriented Verb-movement Pro-drop

Principles and Parameters of the 1980 s/1990 s Headedness parameter OV to VO Inventory of Functional Categories C-oriented (V 2) to T-oriented Verb-movement Pro-drop

1990 s-2013 Parameters now consist of choices of feature specifications as the child acquires a lexicon (Chomsky 2004; 2007). Baker, while disagreeing with this view of parameters, calls this the Borer-Chomsky. Conjecture (2008: 156): "All parameters of variation are attributable to differences in the features of particular items (e. g. , the functional heads) in the lexicon. "

1990 s-2013 Parameters now consist of choices of feature specifications as the child acquires a lexicon (Chomsky 2004; 2007). Baker, while disagreeing with this view of parameters, calls this the Borer-Chomsky. Conjecture (2008: 156): "All parameters of variation are attributable to differences in the features of particular items (e. g. , the functional heads) in the lexicon. "

Shift With the shift to parametric parameters, it becomes possible to think of gradual change through reanalysis as well (e. g. Roberts 2009 and van Gelderen 2009). Word order change in terms if features e. g. Breitbarth 2012, Biberauer & Roberts (2008). The set of features that are available to the learner is determined by UG.

Shift With the shift to parametric parameters, it becomes possible to think of gradual change through reanalysis as well (e. g. Roberts 2009 and van Gelderen 2009). Word order change in terms if features e. g. Breitbarth 2012, Biberauer & Roberts (2008). The set of features that are available to the learner is determined by UG.

Features and grammaticalization Another minimalist approach using features, not concerned with word order, can be found in van Gelderen (2004; 2010) who argues that grammaticalization can be understood as a change from semantic to formal features. For instance, a verb with semantic features, such as Old English will with [volition, expectation, future], can be reanalyzed as having only the grammatical feature [future].

Features and grammaticalization Another minimalist approach using features, not concerned with word order, can be found in van Gelderen (2004; 2010) who argues that grammaticalization can be understood as a change from semantic to formal features. For instance, a verb with semantic features, such as Old English will with [volition, expectation, future], can be reanalyzed as having only the grammatical feature [future].

Cycles tell us which features matter Subject and Object Agreement (Givón) demonstrative > third ps pronoun > agreement > zero noun > first and second person > agreement > zero noun > noun marker > agreement > zero Copula Cycle (Katz) demonstrative > copula > zero third person > copula > zero verb > aspect > copula Noun Cycle (Greenberg) demonstrative > definite article > ‘Case’ > zero noun > number/gender > zero

Cycles tell us which features matter Subject and Object Agreement (Givón) demonstrative > third ps pronoun > agreement > zero noun > first and second person > agreement > zero noun > noun marker > agreement > zero Copula Cycle (Katz) demonstrative > copula > zero third person > copula > zero verb > aspect > copula Noun Cycle (Greenberg) demonstrative > definite article > ‘Case’ > zero noun > number/gender > zero

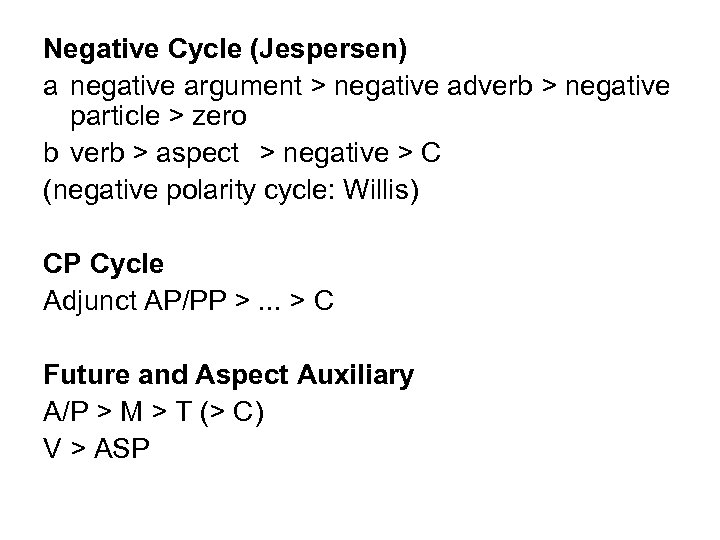

Negative Cycle (Jespersen) a negative argument > negative adverb > negative particle > zero b verb > aspect > negative > C (negative polarity cycle: Willis) CP Cycle Adjunct AP/PP >. . . > C Future and Aspect Auxiliary A/P > M > T (> C) V > ASP

Negative Cycle (Jespersen) a negative argument > negative adverb > negative particle > zero b verb > aspect > negative > C (negative polarity cycle: Willis) CP Cycle Adjunct AP/PP >. . . > C Future and Aspect Auxiliary A/P > M > T (> C) V > ASP

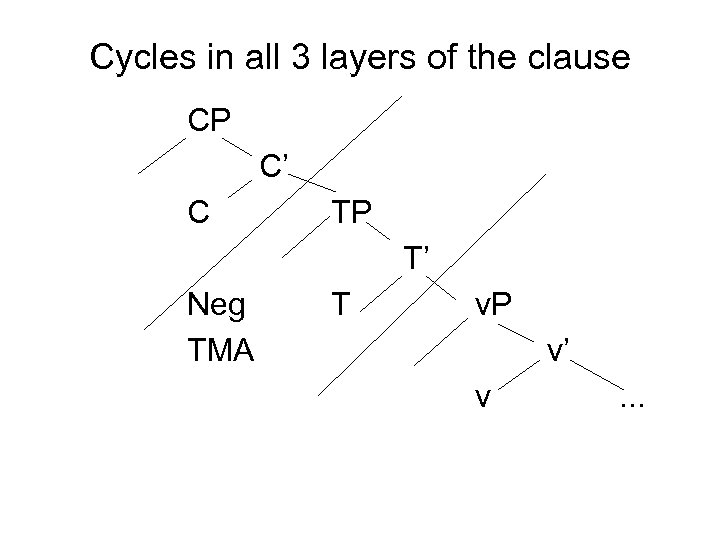

Cycles in all 3 layers of the clause CP C’ C TP T’ Neg TMA T v. P v’ v . . .

Cycles in all 3 layers of the clause CP C’ C TP T’ Neg TMA T v. P v’ v . . .

Stages: VP argument > adverb > higher position

Stages: VP argument > adverb > higher position

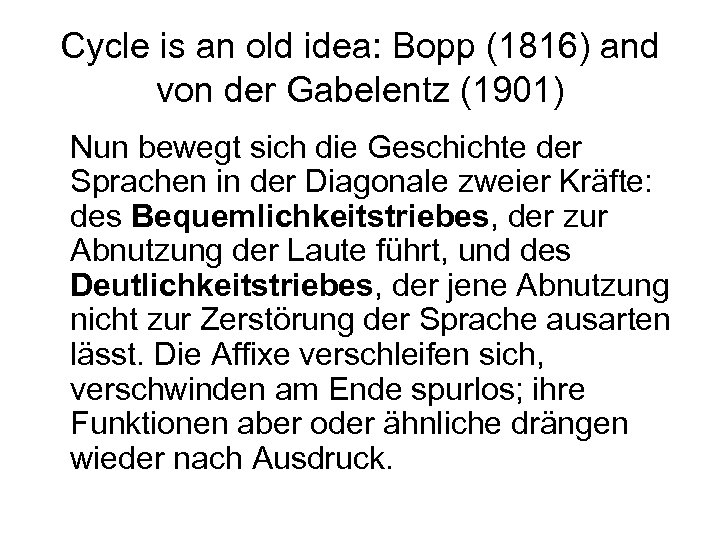

Cycle is an old idea: Bopp (1816) and von der Gabelentz (1901) Nun bewegt sich die Geschichte der Sprachen in der Diagonale zweier Kräfte: des Bequemlichkeitstriebes, der zur Abnutzung der Laute führt, und des Deutlichkeitstriebes, der jene Abnutzung nicht zur Zerstörung der Sprache ausarten lässt. Die Affixe verschleifen sich, verschwinden am Ende spurlos; ihre Funktionen aber oder ähnliche drängen wieder nach Ausdruck.

Cycle is an old idea: Bopp (1816) and von der Gabelentz (1901) Nun bewegt sich die Geschichte der Sprachen in der Diagonale zweier Kräfte: des Bequemlichkeitstriebes, der zur Abnutzung der Laute führt, und des Deutlichkeitstriebes, der jene Abnutzung nicht zur Zerstörung der Sprache ausarten lässt. Die Affixe verschleifen sich, verschwinden am Ende spurlos; ihre Funktionen aber oder ähnliche drängen wieder nach Ausdruck.

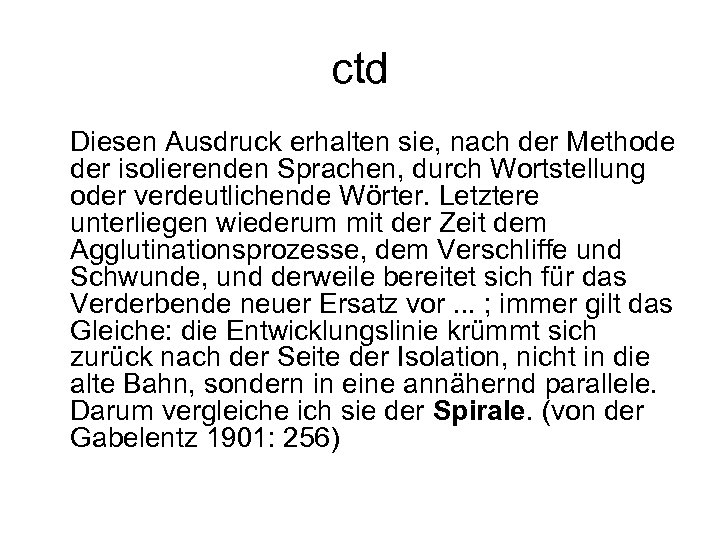

ctd Diesen Ausdruck erhalten sie, nach der Methode der isolierenden Sprachen, durch Wortstellung oder verdeutlichende Wörter. Letztere unterliegen wiederum mit der Zeit dem Agglutinationsprozesse, dem Verschliffe und Schwunde, und derweile bereitet sich für das Verderbende neuer Ersatz vor. . . ; immer gilt das Gleiche: die Entwicklungslinie krümmt sich zurück nach der Seite der Isolation, nicht in die alte Bahn, sondern in eine annähernd parallele. Darum vergleiche ich sie der Spirale. (von der Gabelentz 1901: 256)

ctd Diesen Ausdruck erhalten sie, nach der Methode der isolierenden Sprachen, durch Wortstellung oder verdeutlichende Wörter. Letztere unterliegen wiederum mit der Zeit dem Agglutinationsprozesse, dem Verschliffe und Schwunde, und derweile bereitet sich für das Verderbende neuer Ersatz vor. . . ; immer gilt das Gleiche: die Entwicklungslinie krümmt sich zurück nach der Seite der Isolation, nicht in die alte Bahn, sondern in eine annähernd parallele. Darum vergleiche ich sie der Spirale. (von der Gabelentz 1901: 256)

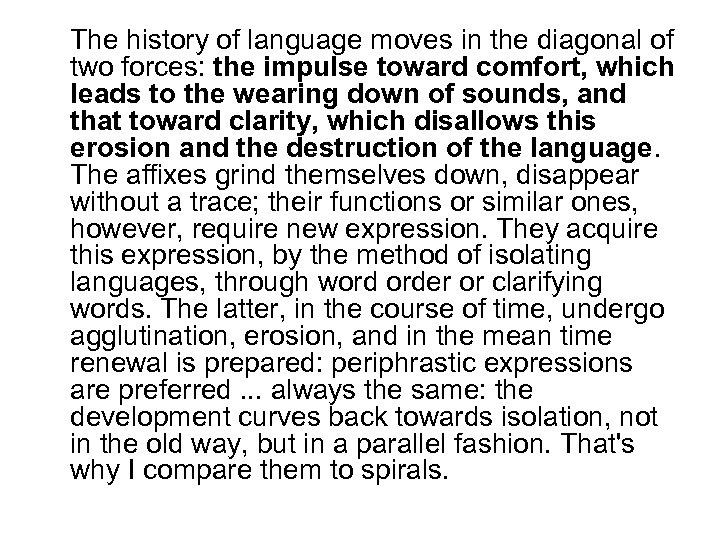

The history of language moves in the diagonal of two forces: the impulse toward comfort, which leads to the wearing down of sounds, and that toward clarity, which disallows this erosion and the destruction of the language. The affixes grind themselves down, disappear without a trace; their functions or similar ones, however, require new expression. They acquire this expression, by the method of isolating languages, through word order or clarifying words. The latter, in the course of time, undergo agglutination, erosion, and in the mean time renewal is prepared: periphrastic expressions are preferred. . . always the same: the development curves back towards isolation, not in the old way, but in a parallel fashion. That's why I compare them to spirals.

The history of language moves in the diagonal of two forces: the impulse toward comfort, which leads to the wearing down of sounds, and that toward clarity, which disallows this erosion and the destruction of the language. The affixes grind themselves down, disappear without a trace; their functions or similar ones, however, require new expression. They acquire this expression, by the method of isolating languages, through word order or clarifying words. The latter, in the course of time, undergo agglutination, erosion, and in the mean time renewal is prepared: periphrastic expressions are preferred. . . always the same: the development curves back towards isolation, not in the old way, but in a parallel fashion. That's why I compare them to spirals.

Comfort + Clarity = Grammaticalization + Renewal Von der Gabelentz’ examples of comfort: the unclear pronunciation of everyday expressions, the use of a few words instead of a full sentence, i. e. ellipsis (p. 182 -184), “syntaktische Nachlässigkeiten aller Art” (`syntactic carelessness of all kinds’, p. 184), and loss of gender.

Comfort + Clarity = Grammaticalization + Renewal Von der Gabelentz’ examples of comfort: the unclear pronunciation of everyday expressions, the use of a few words instead of a full sentence, i. e. ellipsis (p. 182 -184), “syntaktische Nachlässigkeiten aller Art” (`syntactic carelessness of all kinds’, p. 184), and loss of gender.

Von der G’s examples of clarity special exertion of the speech organs (p. 183), “Wiederholung” (`repetition’, p. 239), periphrastic expressions (p. 239), replacing words like sehr `very’ by more powerful and specific words such as riesig `gigantic’ and schrecklich `frightful’ (243), using a rhetorical question instead of a regular proposition, and replacing case with prepositions (p. 183).

Von der G’s examples of clarity special exertion of the speech organs (p. 183), “Wiederholung” (`repetition’, p. 239), periphrastic expressions (p. 239), replacing words like sehr `very’ by more powerful and specific words such as riesig `gigantic’ and schrecklich `frightful’ (243), using a rhetorical question instead of a regular proposition, and replacing case with prepositions (p. 183).

Grammaticalization = one step Hopper & Traugott 2003: content item > grammatical word > clitic > inflectional affix. The loss in phonological content is not a necessary consequence of the loss of semantic content (see Kiparsky 2011; Kiparsky & Condoravdi 2006; Hoeksema 2009). Kiparsky (2011: 19): “in the development of case, bleaching is not necessarily tied to morphological downgrading from postposition to clitic to suffix. ” Instead, unidirectionality is the defining property of grammaticalization and any exceptions to the unidirectionality (e. g. the Spanish inflectional morpheme –nos changing to a pronoun) are instances of analogical changes.

Grammaticalization = one step Hopper & Traugott 2003: content item > grammatical word > clitic > inflectional affix. The loss in phonological content is not a necessary consequence of the loss of semantic content (see Kiparsky 2011; Kiparsky & Condoravdi 2006; Hoeksema 2009). Kiparsky (2011: 19): “in the development of case, bleaching is not necessarily tied to morphological downgrading from postposition to clitic to suffix. ” Instead, unidirectionality is the defining property of grammaticalization and any exceptions to the unidirectionality (e. g. the Spanish inflectional morpheme –nos changing to a pronoun) are instances of analogical changes.

Renewal is the other step In acknowledging weakening of pronunciation (“un affaiblissement de la pronunciation”), Meillet (1912: 139) writes that what provokes the start of the (negative) cycle is the need to speak forcefully (“le besoin de parler avec force”). Kiparsky & Condoravdi (2006) similarly suggest pragmatic and semantic reasons. A simple negative cannot be emphatic; in order for a negative to be emphatic, it needs to be reinforced, e. g. by a minimizer.

Renewal is the other step In acknowledging weakening of pronunciation (“un affaiblissement de la pronunciation”), Meillet (1912: 139) writes that what provokes the start of the (negative) cycle is the need to speak forcefully (“le besoin de parler avec force”). Kiparsky & Condoravdi (2006) similarly suggest pragmatic and semantic reasons. A simple negative cannot be emphatic; in order for a negative to be emphatic, it needs to be reinforced, e. g. by a minimizer.

Four cycles I will mention/look at Negative Cycles negative argument > negative adverb > negative particle > zero negative verb > auxiliary > negative > zero Subject Agreement Cycle demonstrative/emphatic > pronoun > agreement > zero Copula Cycles demonstrative/verb/adposition > copula > zero Nominal Cycles demonstrative > article/copula/tense marker noun > gender/number marker

Four cycles I will mention/look at Negative Cycles negative argument > negative adverb > negative particle > zero negative verb > auxiliary > negative > zero Subject Agreement Cycle demonstrative/emphatic > pronoun > agreement > zero Copula Cycles demonstrative/verb/adposition > copula > zero Nominal Cycles demonstrative > article/copula/tense marker noun > gender/number marker

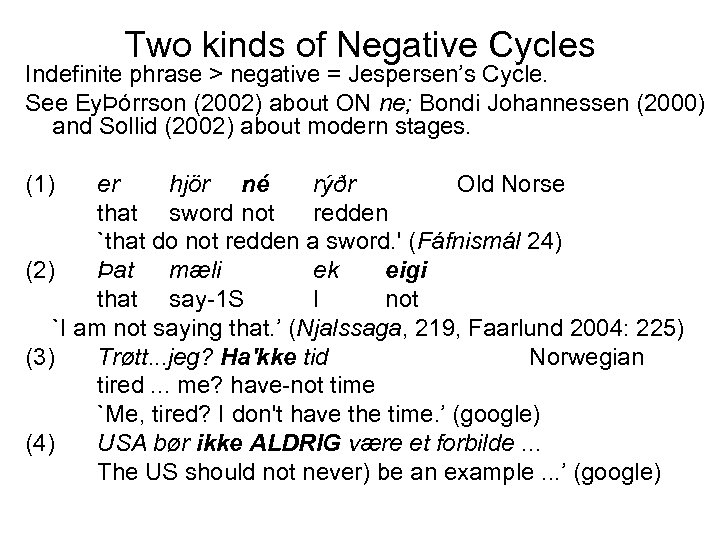

Two kinds of Negative Cycles Indefinite phrase > negative = Jespersen’s Cycle. See EyÞórrson (2002) about ON ne; Bondi Johannessen (2000) and Sollid (2002) about modern stages. (1) er hjör né rýðr Old Norse that sword not redden `that do not redden a sword. ' (Fáfnismál 24) (2) Þat mæli ek eigi that say-1 S I not `I am not saying that. ’ (Njalssaga, 219, Faarlund 2004: 225) (3) Trøtt. . . jeg? Ha'kke tid Norwegian tired. . . me? have-not time `Me, tired? I don't have the time. ’ (google) (4) USA bør ikke ALDRIG være et forbilde. . . The US should not never) be an example. . . ’ (google)

Two kinds of Negative Cycles Indefinite phrase > negative = Jespersen’s Cycle. See EyÞórrson (2002) about ON ne; Bondi Johannessen (2000) and Sollid (2002) about modern stages. (1) er hjör né rýðr Old Norse that sword not redden `that do not redden a sword. ' (Fáfnismál 24) (2) Þat mæli ek eigi that say-1 S I not `I am not saying that. ’ (Njalssaga, 219, Faarlund 2004: 225) (3) Trøtt. . . jeg? Ha'kke tid Norwegian tired. . . me? have-not time `Me, tired? I don't have the time. ’ (google) (4) USA bør ikke ALDRIG være et forbilde. . . The US should not never) be an example. . . ’ (google)

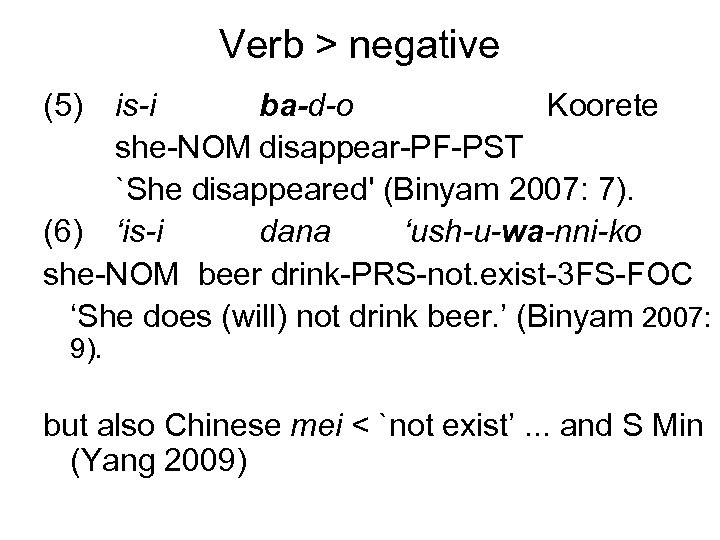

Verb > negative (5) is-i ba-d-o Koorete she-NOM disappear-PF-PST `She disappeared' (Binyam 2007: 7). (6) ‘is-i dana ‘ush-u-wa-nni-ko she-NOM beer drink-PRS-not. exist-3 FS-FOC ‘She does (will) not drink beer. ’ (Binyam 2007: 9). but also Chinese mei < `not exist’. . . and S Min (Yang 2009)

Verb > negative (5) is-i ba-d-o Koorete she-NOM disappear-PF-PST `She disappeared' (Binyam 2007: 7). (6) ‘is-i dana ‘ush-u-wa-nni-ko she-NOM beer drink-PRS-not. exist-3 FS-FOC ‘She does (will) not drink beer. ’ (Binyam 2007: 9). but also Chinese mei < `not exist’. . . and S Min (Yang 2009)

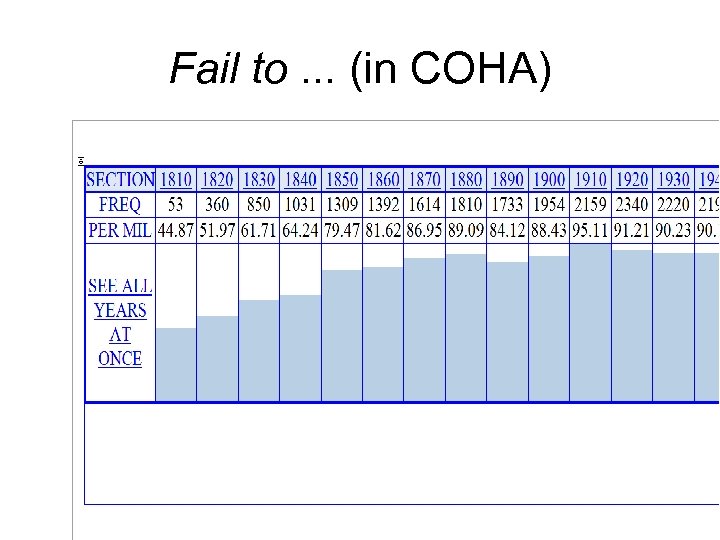

Fail to. . . (in COHA)

Fail to. . . (in COHA)

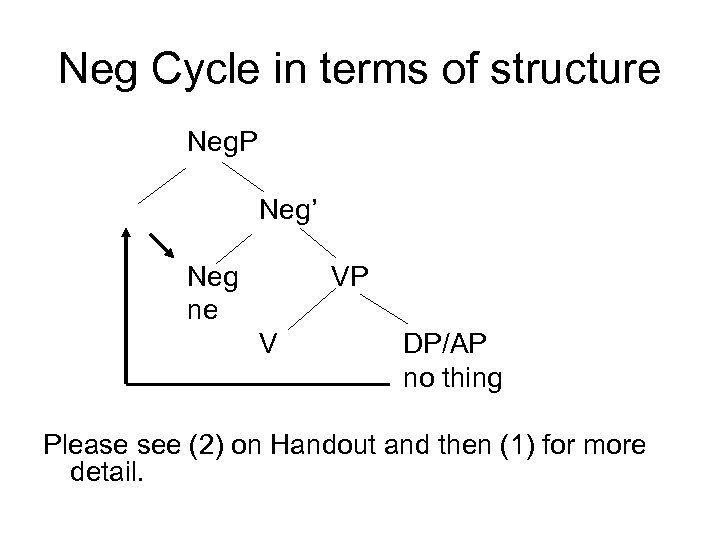

Neg Cycle in terms of structure Neg. P Neg’ Neg ne VP V DP/AP no thing Please see (2) on Handout and then (1) for more detail.

Neg Cycle in terms of structure Neg. P Neg’ Neg ne VP V DP/AP no thing Please see (2) on Handout and then (1) for more detail.

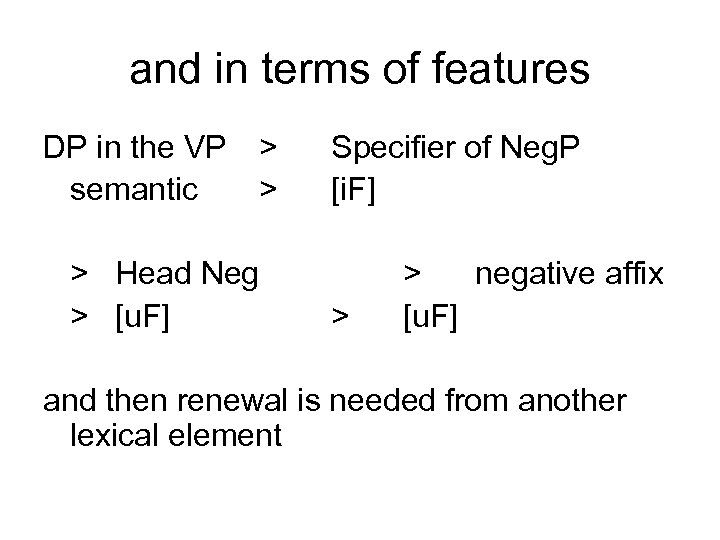

and in terms of features DP in the VP > semantic > > Head Neg > [u. F] Specifier of Neg. P [i. F] > > negative affix [u. F] and then renewal is needed from another lexical element

and in terms of features DP in the VP > semantic > > Head Neg > [u. F] Specifier of Neg. P [i. F] > > negative affix [u. F] and then renewal is needed from another lexical element

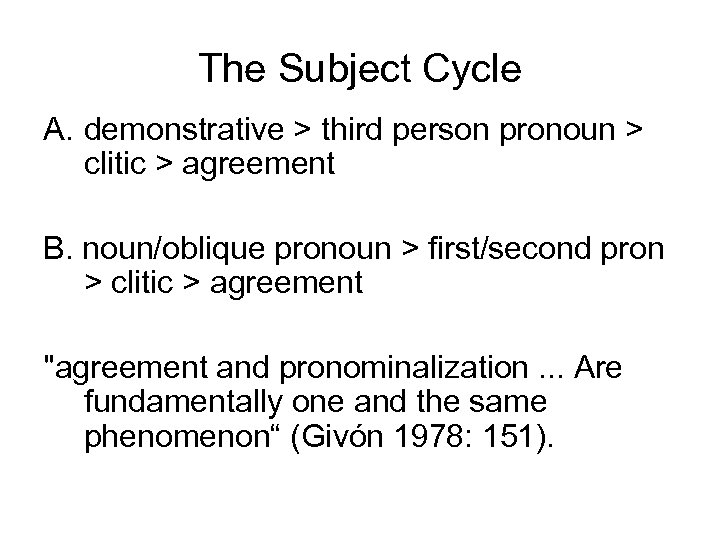

The Subject Cycle A. demonstrative > third person pronoun > clitic > agreement B. noun/oblique pronoun > first/second pron > clitic > agreement "agreement and pronominalization. . . Are fundamentally one and the same phenomenon“ (Givón 1978: 151).

The Subject Cycle A. demonstrative > third person pronoun > clitic > agreement B. noun/oblique pronoun > first/second pron > clitic > agreement "agreement and pronominalization. . . Are fundamentally one and the same phenomenon“ (Givón 1978: 151).

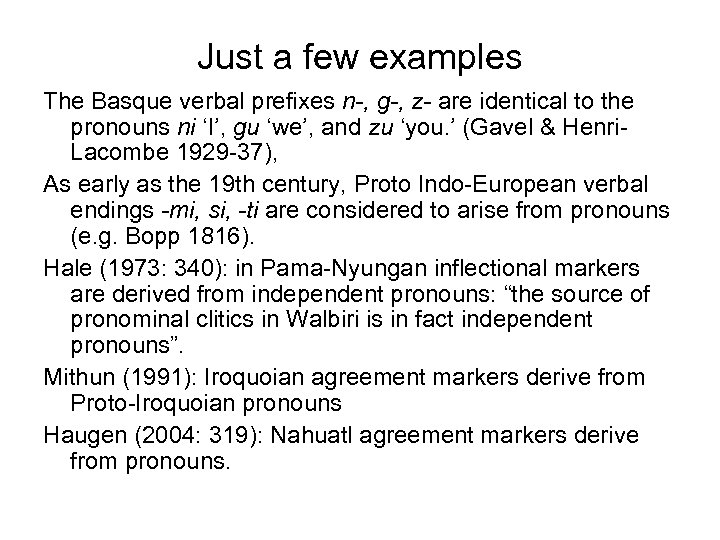

Just a few examples The Basque verbal prefixes n-, g-, z- are identical to the pronouns ni ‘I’, gu ‘we’, and zu ‘you. ’ (Gavel & Henri. Lacombe 1929 -37), As early as the 19 th century, Proto Indo-European verbal endings -mi, si, -ti are considered to arise from pronouns (e. g. Bopp 1816). Hale (1973: 340): in Pama-Nyungan inflectional markers are derived from independent pronouns: “the source of pronominal clitics in Walbiri is in fact independent pronouns”. Mithun (1991): Iroquoian agreement markers derive from Proto-Iroquoian pronouns Haugen (2004: 319): Nahuatl agreement markers derive from pronouns.

Just a few examples The Basque verbal prefixes n-, g-, z- are identical to the pronouns ni ‘I’, gu ‘we’, and zu ‘you. ’ (Gavel & Henri. Lacombe 1929 -37), As early as the 19 th century, Proto Indo-European verbal endings -mi, si, -ti are considered to arise from pronouns (e. g. Bopp 1816). Hale (1973: 340): in Pama-Nyungan inflectional markers are derived from independent pronouns: “the source of pronominal clitics in Walbiri is in fact independent pronouns”. Mithun (1991): Iroquoian agreement markers derive from Proto-Iroquoian pronouns Haugen (2004: 319): Nahuatl agreement markers derive from pronouns.

![Tunica prefixes: Ɂi- [1 S], Ɂu- [3 SM], pronouns: Ɂima, Ɂu'wi, wi-[2 SM], hi-/ Tunica prefixes: Ɂi- [1 S], Ɂu- [3 SM], pronouns: Ɂima, Ɂu'wi, wi-[2 SM], hi-/](https://present5.com/presentation/345a4072c1b04cc61d1ecee581baa83e/image-36.jpg) Tunica prefixes: Ɂi- [1 S], Ɂu- [3 SM], pronouns: Ɂima, Ɂu'wi, wi-[2 SM], hi-/ he-[2 SF], ti- [3 SF] ma', hɛ'ma, ti'hči (Haas 1946: 346 -7) Donohue (2005): Palu’e, a Malayo-Polynesian language of Indonesia: no agreement but the first person aku can be cliticized. (1) ‘úwa > -‘ú Ute demonstrative pronoun article/agreement invis-animate (Givón 2011) (2) Shi diné bizaad yíní-sh-ta' Navajo I Navajo language 3 -1 -study ‘As for me, I am studying Navajo. ’

Tunica prefixes: Ɂi- [1 S], Ɂu- [3 SM], pronouns: Ɂima, Ɂu'wi, wi-[2 SM], hi-/ he-[2 SF], ti- [3 SF] ma', hɛ'ma, ti'hči (Haas 1946: 346 -7) Donohue (2005): Palu’e, a Malayo-Polynesian language of Indonesia: no agreement but the first person aku can be cliticized. (1) ‘úwa > -‘ú Ute demonstrative pronoun article/agreement invis-animate (Givón 2011) (2) Shi diné bizaad yíní-sh-ta' Navajo I Navajo language 3 -1 -study ‘As for me, I am studying Navajo. ’

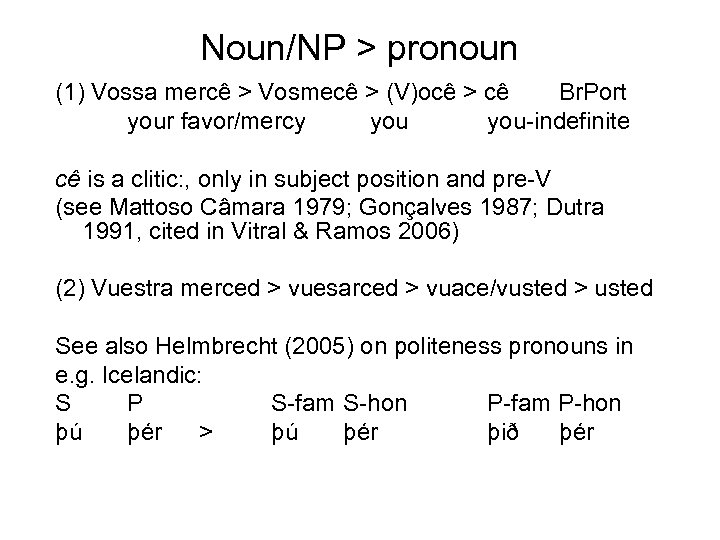

Noun/NP > pronoun (1) Vossa mercê > Vosmecê > (V)ocê > cê Br. Port your favor/mercy you-indefinite cê is a clitic: , only in subject position and pre-V (see Mattoso Câmara 1979; Gonçalves 1987; Dutra 1991, cited in Vitral & Ramos 2006) (2) Vuestra merced > vuesarced > vuace/vusted > usted See also Helmbrecht (2005) on politeness pronouns in e. g. Icelandic: S P S-fam S-hon P-fam P-hon þú þér > þú þér þið þér

Noun/NP > pronoun (1) Vossa mercê > Vosmecê > (V)ocê > cê Br. Port your favor/mercy you-indefinite cê is a clitic: , only in subject position and pre-V (see Mattoso Câmara 1979; Gonçalves 1987; Dutra 1991, cited in Vitral & Ramos 2006) (2) Vuestra merced > vuesarced > vuace/vusted > usted See also Helmbrecht (2005) on politeness pronouns in e. g. Icelandic: S P S-fam S-hon P-fam P-hon þú þér > þú þér þið þér

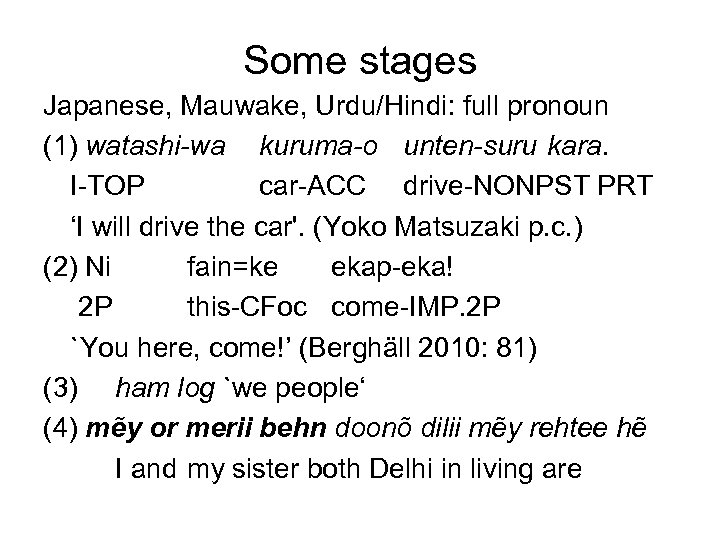

Some stages Japanese, Mauwake, Urdu/Hindi: full pronoun (1) watashi-wa kuruma-o unten-suru kara. I-TOP car-ACC drive-NONPST PRT ‘I will drive the car'. (Yoko Matsuzaki p. c. ) (2) Ni fain=ke ekap-eka! 2 P this-CFoc come-IMP. 2 P `You here, come!’ (Berghäll 2010: 81) (3) ham log `we people‘ (4) mẽy or merii behn doonõ dilii mẽy rehtee hẽ I and my sister both Delhi in living are

Some stages Japanese, Mauwake, Urdu/Hindi: full pronoun (1) watashi-wa kuruma-o unten-suru kara. I-TOP car-ACC drive-NONPST PRT ‘I will drive the car'. (Yoko Matsuzaki p. c. ) (2) Ni fain=ke ekap-eka! 2 P this-CFoc come-IMP. 2 P `You here, come!’ (Berghäll 2010: 81) (3) ham log `we people‘ (4) mẽy or merii behn doonõ dilii mẽy rehtee hẽ I and my sister both Delhi in living are

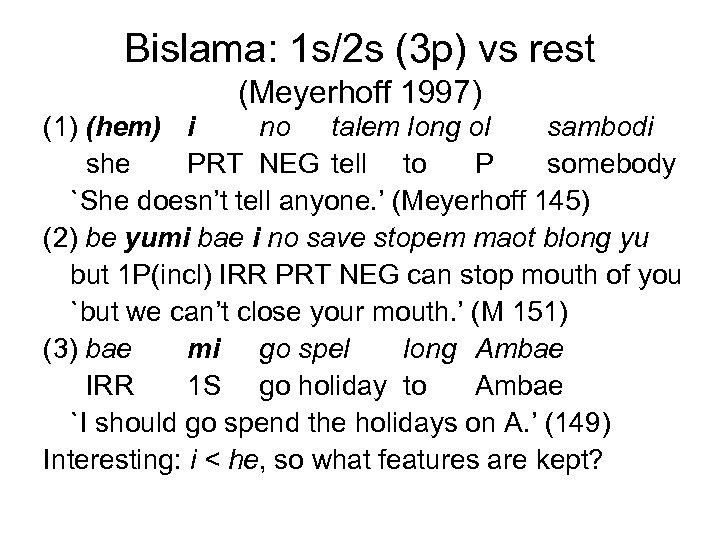

Bislama: 1 s/2 s (3 p) vs rest (Meyerhoff 1997) (1) (hem) i no talem long ol sambodi she PRT NEG tell to P somebody `She doesn’t tell anyone. ’ (Meyerhoff 145) (2) be yumi bae i no save stopem maot blong yu but 1 P(incl) IRR PRT NEG can stop mouth of you `but we can’t close your mouth. ’ (M 151) (3) bae mi go spel long Ambae IRR 1 S go holiday to Ambae `I should go spend the holidays on A. ’ (149) Interesting: i < he, so what features are kept?

Bislama: 1 s/2 s (3 p) vs rest (Meyerhoff 1997) (1) (hem) i no talem long ol sambodi she PRT NEG tell to P somebody `She doesn’t tell anyone. ’ (Meyerhoff 145) (2) be yumi bae i no save stopem maot blong yu but 1 P(incl) IRR PRT NEG can stop mouth of you `but we can’t close your mouth. ’ (M 151) (3) bae mi go spel long Ambae IRR 1 S go holiday to Ambae `I should go spend the holidays on A. ’ (149) Interesting: i < he, so what features are kept?

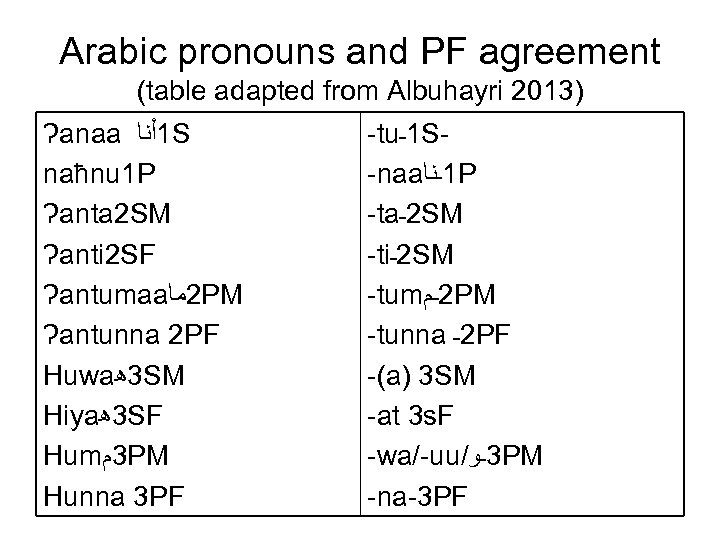

Arabic pronouns and PF agreement (table adapted from Albuhayri 2013) Ɂanaa 1ﺃﻨﺎ S naħnu 1 P Ɂanta 2 SM Ɂanti 2 SF Ɂantumaa 2ﻣﺎ PM Ɂantunna 2 PF Huwa 3ﻫ SM Hiya 3ﻫ SF Hum 3ﻡ PM Hunna 3 PF -tu 1ـ S-naa 1ـﻨﺎ P -ta 2ـ SM -ti 2ـ SM -tum 2ـﻡ PM -tunna 2ـ PF -(a) 3 SM -at 3 s. F -wa/-uu/ 3ـﻮ PM -na-3 PF

Arabic pronouns and PF agreement (table adapted from Albuhayri 2013) Ɂanaa 1ﺃﻨﺎ S naħnu 1 P Ɂanta 2 SM Ɂanti 2 SF Ɂantumaa 2ﻣﺎ PM Ɂantunna 2 PF Huwa 3ﻫ SM Hiya 3ﻫ SF Hum 3ﻡ PM Hunna 3 PF -tu 1ـ S-naa 1ـﻨﺎ P -ta 2ـ SM -ti 2ـ SM -tum 2ـﻡ PM -tunna 2ـ PF -(a) 3 SM -at 3 s. F -wa/-uu/ 3ـﻮ PM -na-3 PF

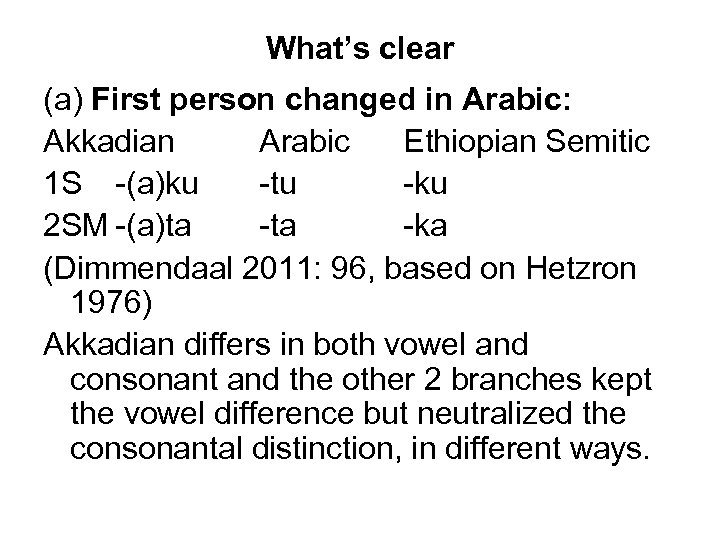

What’s clear (a) First person changed in Arabic: Akkadian Arabic Ethiopian Semitic 1 S -(a)ku -tu -ku 2 SM -(a)ta -ka (Dimmendaal 2011: 96, based on Hetzron 1976) Akkadian differs in both vowel and consonant and the other 2 branches kept the vowel difference but neutralized the consonantal distinction, in different ways.

What’s clear (a) First person changed in Arabic: Akkadian Arabic Ethiopian Semitic 1 S -(a)ku -tu -ku 2 SM -(a)ta -ka (Dimmendaal 2011: 96, based on Hetzron 1976) Akkadian differs in both vowel and consonant and the other 2 branches kept the vowel difference but neutralized the consonantal distinction, in different ways.

(b) Third person has a different development; only gender/number is marked (Huehnergard & Pat-El 2012); probably derives from nominal inflection (Pat-El p. c). Russell (1984: 119): first and second person of the suffix conjugation are “clearly related to the pronominal forms”; third person has its origin in “the system of nominal inflection and modification. ”

(b) Third person has a different development; only gender/number is marked (Huehnergard & Pat-El 2012); probably derives from nominal inflection (Pat-El p. c). Russell (1984: 119): first and second person of the suffix conjugation are “clearly related to the pronominal forms”; third person has its origin in “the system of nominal inflection and modification. ”

What were the pronouns that became the affixes? Semitic free pronouns have a demonstrative base: in- (Egyptian) and an- (Arabic) so not clear that the affixes arose from them. Perfective verbs could have been nominals. Givón (1976: 183 -4): personal endings in Arabic first develop on the participial (nominal) and the suffixes develop from the inflected copulas.

What were the pronouns that became the affixes? Semitic free pronouns have a demonstrative base: in- (Egyptian) and an- (Arabic) so not clear that the affixes arose from them. Perfective verbs could have been nominals. Givón (1976: 183 -4): personal endings in Arabic first develop on the participial (nominal) and the suffixes develop from the inflected copulas.

Other challenges: Noun class/gender markers Where do they come from? nouns First/second and third person split, e. g. Temne Renewal on the nouns, e. g. in Zulu, bmo of preprefix (1) a-ba-ntu ba-khona PR-CL 2 -people CL 2 -present `The people are present. ’ (Cope 1984: 16; Buell 2005: 8) How do they end up as agreement and how come they are so stable? Possibly loss on nouns in Chichewa.

Other challenges: Noun class/gender markers Where do they come from? nouns First/second and third person split, e. g. Temne Renewal on the nouns, e. g. in Zulu, bmo of preprefix (1) a-ba-ntu ba-khona PR-CL 2 -people CL 2 -present `The people are present. ’ (Cope 1984: 16; Buell 2005: 8) How do they end up as agreement and how come they are so stable? Possibly loss on nouns in Chichewa.

Temne In Temne (Hutchinson 1969), a West Atlantic member of the Niger-Congo family spoken in Sierra Leone, the class marker on the noun is also used on the verb as agreement. (The class marker is specified on the noun for definite, indefinite, singular, and plural but for only singular or plural on the verb). (1) ɔ-tik ɔ-fumpɔ 1 def. S-stranger 1 S-fell `The stranger fell. ’ First, second, and third person are not `doubly’ marked: (2) i/ɔ fumpɔ 1 S/3 S fell `I/he fell. ’ (Hutchison 1969: 8; 11)

Temne In Temne (Hutchinson 1969), a West Atlantic member of the Niger-Congo family spoken in Sierra Leone, the class marker on the noun is also used on the verb as agreement. (The class marker is specified on the noun for definite, indefinite, singular, and plural but for only singular or plural on the verb). (1) ɔ-tik ɔ-fumpɔ 1 def. S-stranger 1 S-fell `The stranger fell. ’ First, second, and third person are not `doubly’ marked: (2) i/ɔ fumpɔ 1 S/3 S fell `I/he fell. ’ (Hutchison 1969: 8; 11)

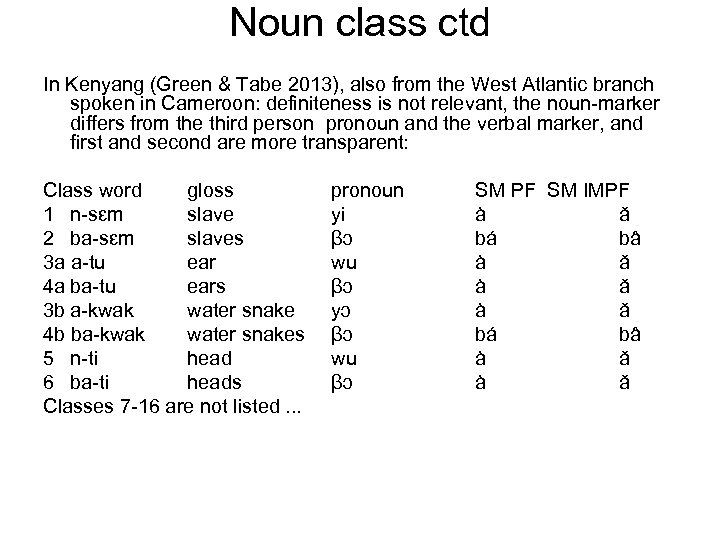

Noun class ctd In Kenyang (Green & Tabe 2013), also from the West Atlantic branch spoken in Cameroon: definiteness is not relevant, the noun-marker differs from the third person pronoun and the verbal marker, and first and second are more transparent: Class word gloss 1 n-sɛm slave 2 ba-sɛm slaves 3 a a-tu ear 4 a ba-tu ears 3 b a-kwak water snake 4 b ba-kwak water snakes 5 n-ti head 6 ba-ti heads Classes 7 -16 are not listed. . . pronoun yi βɔ wu βɔ yɔ βɔ wu βɔ SM PF SM IMPF à ǎ bá bâ à ǎ à ǎ

Noun class ctd In Kenyang (Green & Tabe 2013), also from the West Atlantic branch spoken in Cameroon: definiteness is not relevant, the noun-marker differs from the third person pronoun and the verbal marker, and first and second are more transparent: Class word gloss 1 n-sɛm slave 2 ba-sɛm slaves 3 a a-tu ear 4 a ba-tu ears 3 b a-kwak water snake 4 b ba-kwak water snakes 5 n-ti head 6 ba-ti heads Classes 7 -16 are not listed. . . pronoun yi βɔ wu βɔ yɔ βɔ wu βɔ SM PF SM IMPF à ǎ bá bâ à ǎ à ǎ

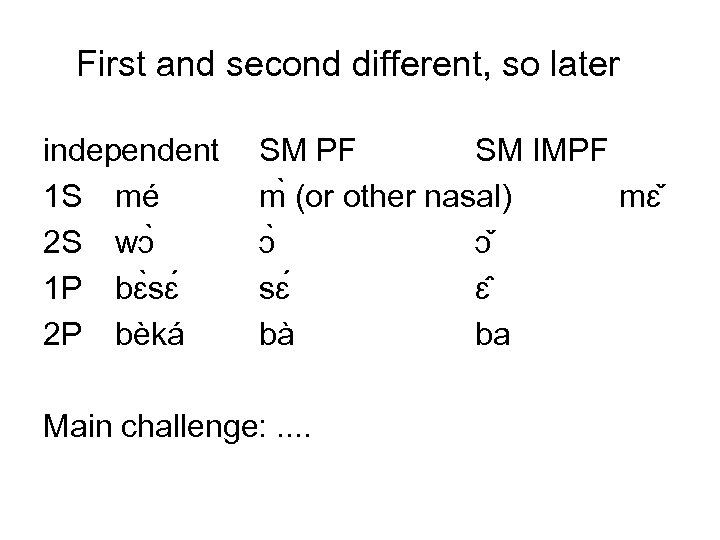

First and second different, so later independent 1 S mé 2 S wɔ 1 P bɛ sɛ 2 P bèká SM PF SM IMPF m (or other nasal) mɛ ɔ ɔ sɛ ɛ bà ba Main challenge: . .

First and second different, so later independent 1 S mé 2 S wɔ 1 P bɛ sɛ 2 P bèká SM PF SM IMPF m (or other nasal) mɛ ɔ ɔ sɛ ɛ bà ba Main challenge: . .

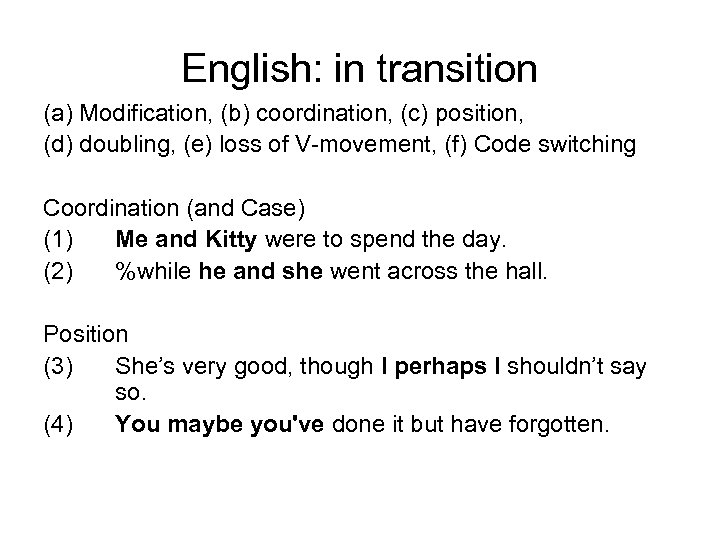

English: in transition (a) Modification, (b) coordination, (c) position, (d) doubling, (e) loss of V-movement, (f) Code switching Coordination (and Case) (1) Me and Kitty were to spend the day. (2) %while he and she went across the hall. Position (3) She’s very good, though I perhaps I shouldn’t say so. (4) You maybe you've done it but have forgotten.

English: in transition (a) Modification, (b) coordination, (c) position, (d) doubling, (e) loss of V-movement, (f) Code switching Coordination (and Case) (1) Me and Kitty were to spend the day. (2) %while he and she went across the hall. Position (3) She’s very good, though I perhaps I shouldn’t say so. (4) You maybe you've done it but have forgotten.

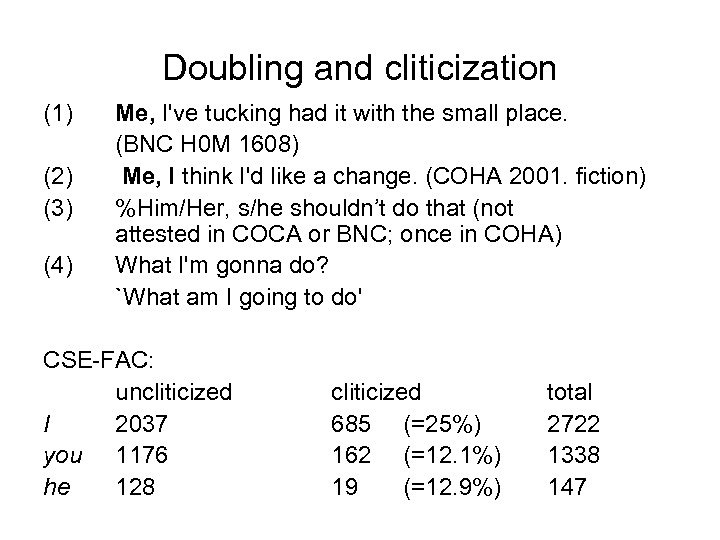

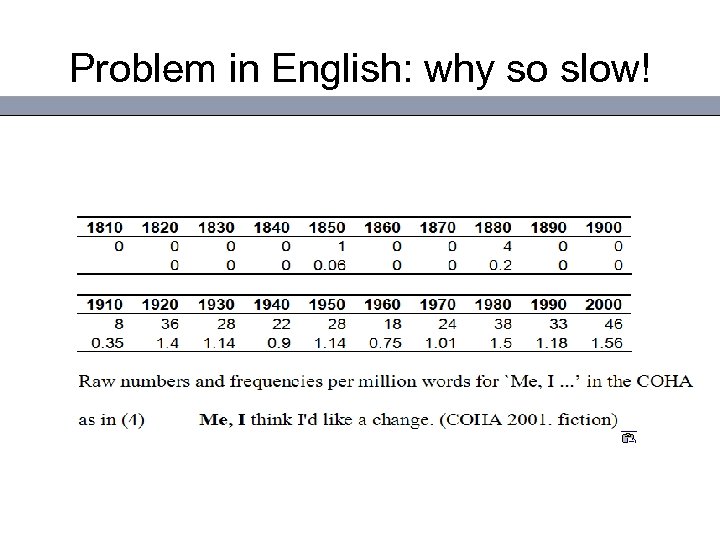

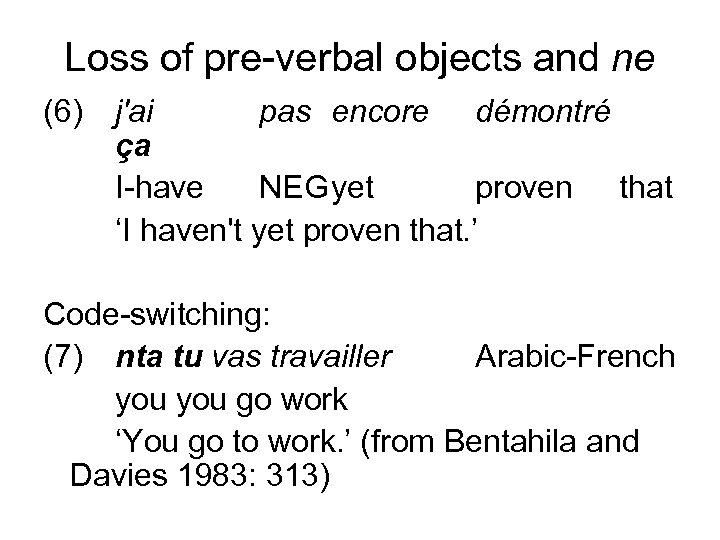

Doubling and cliticization (1) (2) (3) (4) Me, I've tucking had it with the small place. (BNC H 0 M 1608) Me, I think I'd like a change. (COHA 2001. fiction) %Him/Her, s/he shouldn’t do that (not attested in COCA or BNC; once in COHA) What I'm gonna do? `What am I going to do' CSE-FAC: uncliticized I 2037 you 1176 he 128 cliticized 685 (=25%) 162 (=12. 1%) 19 (=12. 9%) total 2722 1338 147

Doubling and cliticization (1) (2) (3) (4) Me, I've tucking had it with the small place. (BNC H 0 M 1608) Me, I think I'd like a change. (COHA 2001. fiction) %Him/Her, s/he shouldn’t do that (not attested in COCA or BNC; once in COHA) What I'm gonna do? `What am I going to do' CSE-FAC: uncliticized I 2037 you 1176 he 128 cliticized 685 (=25%) 162 (=12. 1%) 19 (=12. 9%) total 2722 1338 147

Problem in English: why so slow!

Problem in English: why so slow!

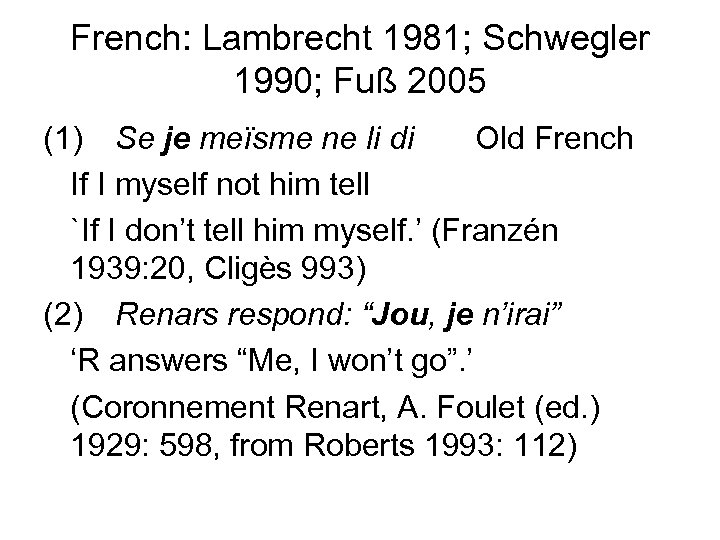

French: Lambrecht 1981; Schwegler 1990; Fuß 2005 (1) Se je meïsme ne li di Old French If I myself not him tell `If I don’t tell him myself. ’ (Franzén 1939: 20, Cligès 993) (2) Renars respond: “Jou, je n’irai” ‘R answers “Me, I won’t go”. ’ (Coronnement Renart, A. Foulet (ed. ) 1929: 598, from Roberts 1993: 112)

French: Lambrecht 1981; Schwegler 1990; Fuß 2005 (1) Se je meïsme ne li di Old French If I myself not him tell `If I don’t tell him myself. ’ (Franzén 1939: 20, Cligès 993) (2) Renars respond: “Jou, je n’irai” ‘R answers “Me, I won’t go”. ’ (Coronnement Renart, A. Foulet (ed. ) 1929: 598, from Roberts 1993: 112)

Foulet (1961: 330): all personal pronouns can be separated from the verb in Old French. Compare Modern French: (3)a. *Je heureusement ai vu ça I probably have seen that `I’ve probably seen that. ’ b. Kurt, heureusement, a fait beaucoup d'autres choses. Kurt fortunately has done many other things `Fortunately, Kurt did many other things’ (google search of French websites) (4) Où vas-tu Standard French where go-2 S (5) tu vas où Colloquial French 2 S go where ‘Where are you going? '

Foulet (1961: 330): all personal pronouns can be separated from the verb in Old French. Compare Modern French: (3)a. *Je heureusement ai vu ça I probably have seen that `I’ve probably seen that. ’ b. Kurt, heureusement, a fait beaucoup d'autres choses. Kurt fortunately has done many other things `Fortunately, Kurt did many other things’ (google search of French websites) (4) Où vas-tu Standard French where go-2 S (5) tu vas où Colloquial French 2 S go where ‘Where are you going? '

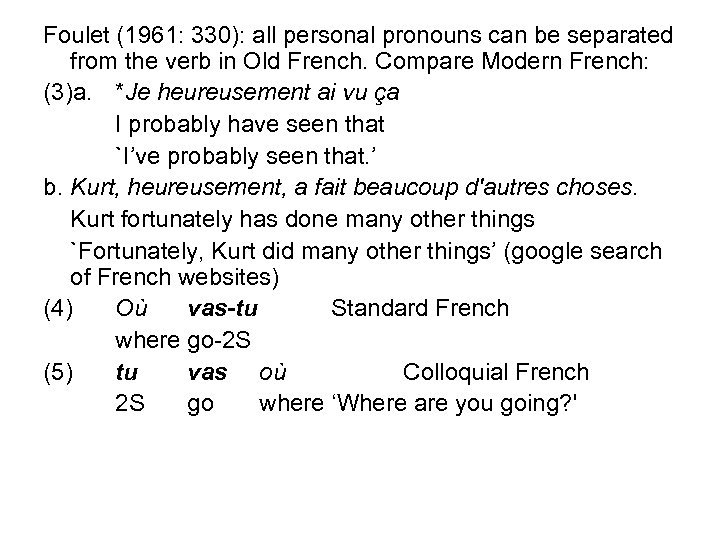

Loss of pre-verbal objects and ne (6) j'ai pas encore démontré ça I-have NEGyet proven that ‘I haven't yet proven that. ’ Code-switching: (7) nta tu vas travailler Arabic-French you go work ‘You go to work. ’ (from Bentahila and Davies 1983: 313)

Loss of pre-verbal objects and ne (6) j'ai pas encore démontré ça I-have NEGyet proven that ‘I haven't yet proven that. ’ Code-switching: (7) nta tu vas travailler Arabic-French you go work ‘You go to work. ’ (from Bentahila and Davies 1983: 313)

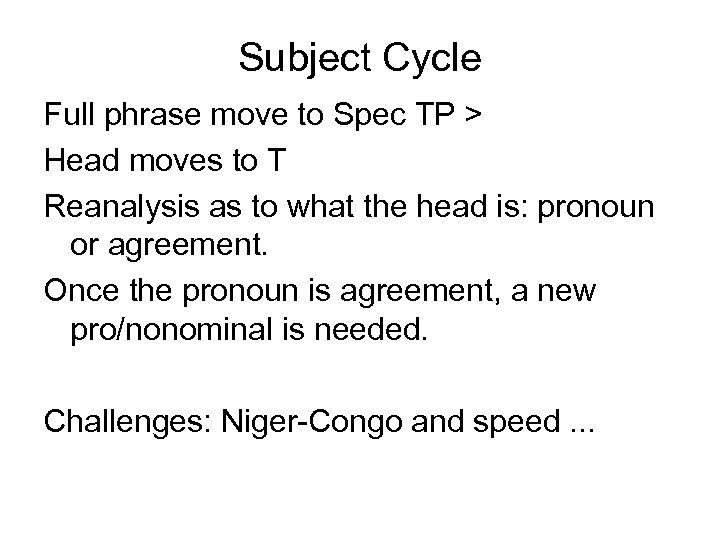

Subject Cycle Full phrase move to Spec TP > Head moves to T Reanalysis as to what the head is: pronoun or agreement. Once the pronoun is agreement, a new pro/nonominal is needed. Challenges: Niger-Congo and speed. . .

Subject Cycle Full phrase move to Spec TP > Head moves to T Reanalysis as to what the head is: pronoun or agreement. Once the pronoun is agreement, a new pro/nonominal is needed. Challenges: Niger-Congo and speed. . .

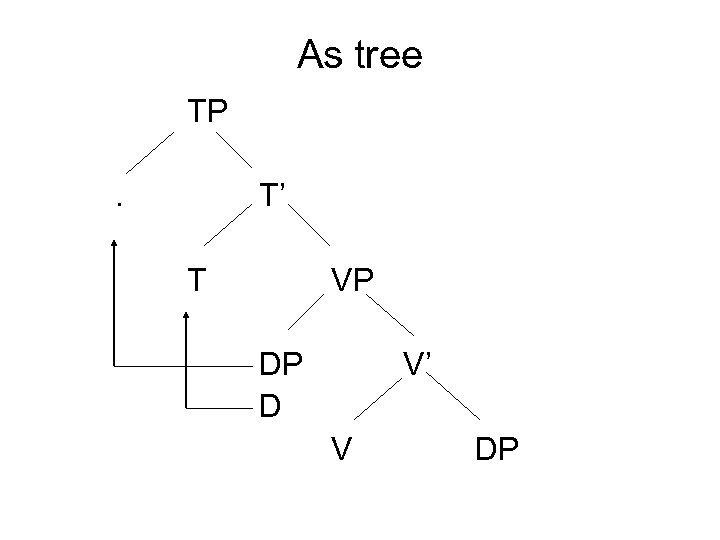

As tree TP. T’ T VP DP D V’ V DP

As tree TP. T’ T VP DP D V’ V DP

![with features Adjunct/Argument > emphatic/noun [semantic] > > Specifier > full pronoun [i-phi] Head with features Adjunct/Argument > emphatic/noun [semantic] > > Specifier > full pronoun [i-phi] Head](https://present5.com/presentation/345a4072c1b04cc61d1ecee581baa83e/image-56.jpg) with features Adjunct/Argument > emphatic/noun [semantic] > > Specifier > full pronoun [i-phi] Head weak/clitic [u-1/2] [i-3] affix agreement [u-phi] [u-#] See (3) and (4) on handout for more detail.

with features Adjunct/Argument > emphatic/noun [semantic] > > Specifier > full pronoun [i-phi] Head weak/clitic [u-1/2] [i-3] affix agreement [u-phi] [u-#] See (3) and (4) on handout for more detail.

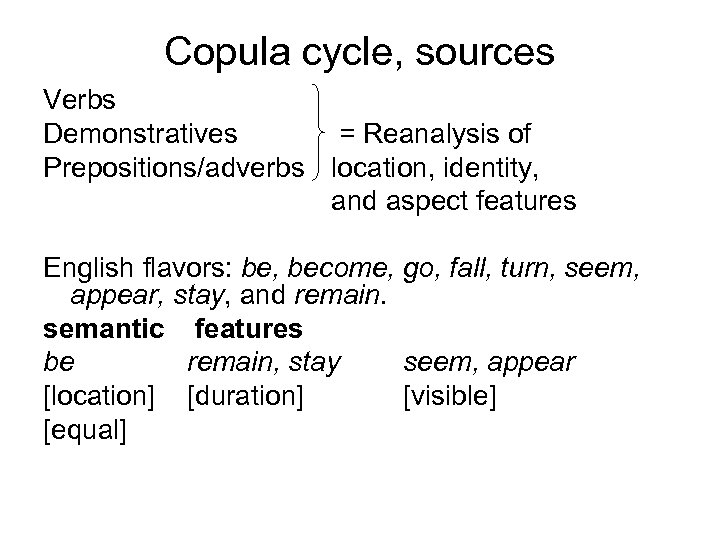

Copula cycle, sources Verbs Demonstratives = Reanalysis of Prepositions/adverbs location, identity, and aspect features English flavors: be, become, go, fall, turn, seem, appear, stay, and remain. semantic features be remain, stay seem, appear [location] [duration] [visible] [equal]

Copula cycle, sources Verbs Demonstratives = Reanalysis of Prepositions/adverbs location, identity, and aspect features English flavors: be, become, go, fall, turn, seem, appear, stay, and remain. semantic features be remain, stay seem, appear [location] [duration] [visible] [equal]

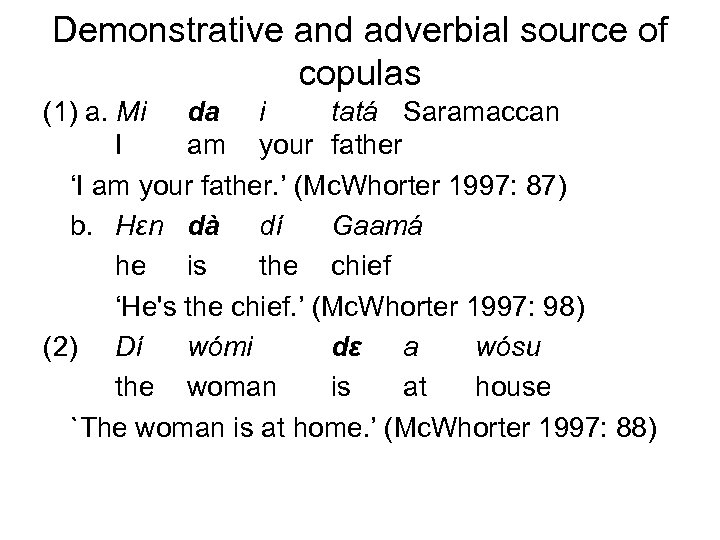

Demonstrative and adverbial source of copulas (1) a. Mi da i tatá Saramaccan I am your father ‘I am your father. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 87) b. Hεn dà dí Gaamá he is the chief ‘He's the chief. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 98) (2) Dí wómi dε a wósu the woman is at house `The woman is at home. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 88)

Demonstrative and adverbial source of copulas (1) a. Mi da i tatá Saramaccan I am your father ‘I am your father. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 87) b. Hεn dà dí Gaamá he is the chief ‘He's the chief. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 98) (2) Dí wómi dε a wósu the woman is at house `The woman is at home. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 88)

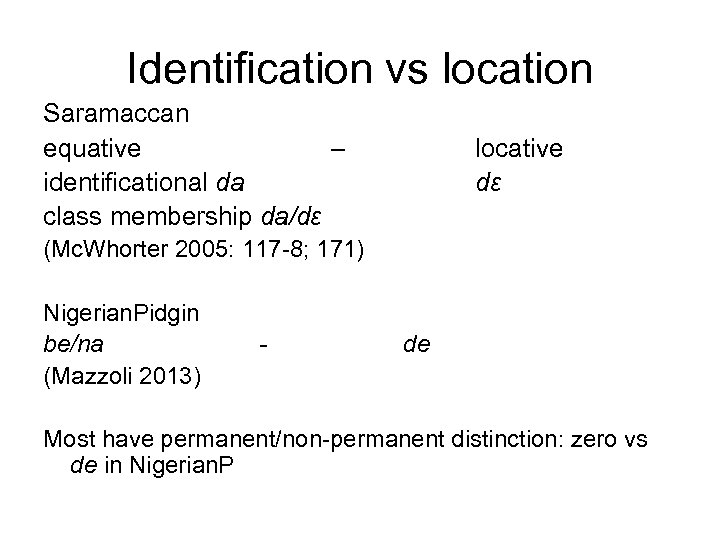

Identification vs location Saramaccan equative – identificational da class membership da/dɛ locative dɛ (Mc. Whorter 2005: 117 -8; 171) Nigerian. Pidgin be/na (Mazzoli 2013) - de Most have permanent/non-permanent distinction: zero vs de in Nigerian. P

Identification vs location Saramaccan equative – identificational da class membership da/dɛ locative dɛ (Mc. Whorter 2005: 117 -8; 171) Nigerian. Pidgin be/na (Mazzoli 2013) - de Most have permanent/non-permanent distinction: zero vs de in Nigerian. P

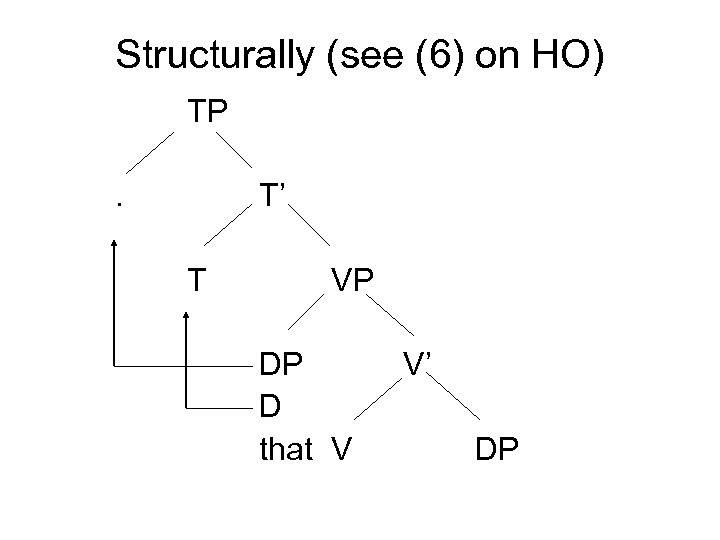

Structurally (see (6) on HO) TP. T’ T VP DP D that V V’ DP

Structurally (see (6) on HO) TP. T’ T VP DP D that V V’ DP

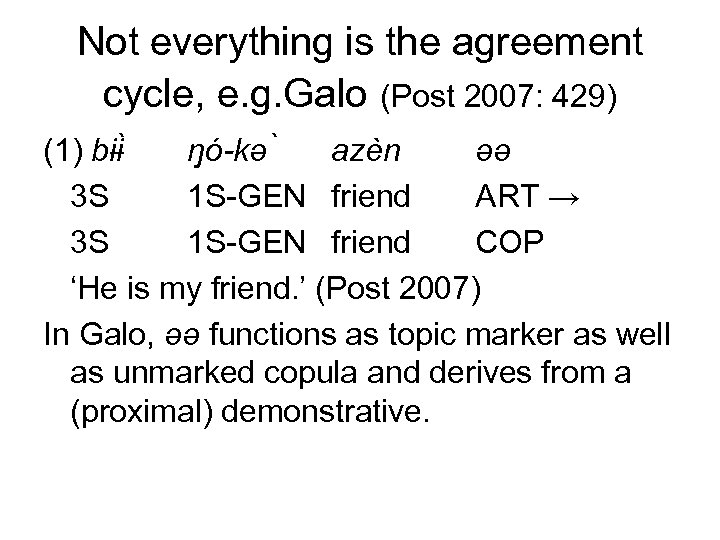

Not everything is the agreement cycle, e. g. Galo (Post 2007: 429) (1) bɨɨ ŋó-kə azèn əə 3 S 1 S-GEN friend ART → 3 S 1 S-GEN friend COP ‘He is my friend. ’ (Post 2007) In Galo, əə functions as topic marker as well as unmarked copula and derives from a (proximal) demonstrative.

Not everything is the agreement cycle, e. g. Galo (Post 2007: 429) (1) bɨɨ ŋó-kə azèn əə 3 S 1 S-GEN friend ART → 3 S 1 S-GEN friend COP ‘He is my friend. ’ (Post 2007) In Galo, əə functions as topic marker as well as unmarked copula and derives from a (proximal) demonstrative.

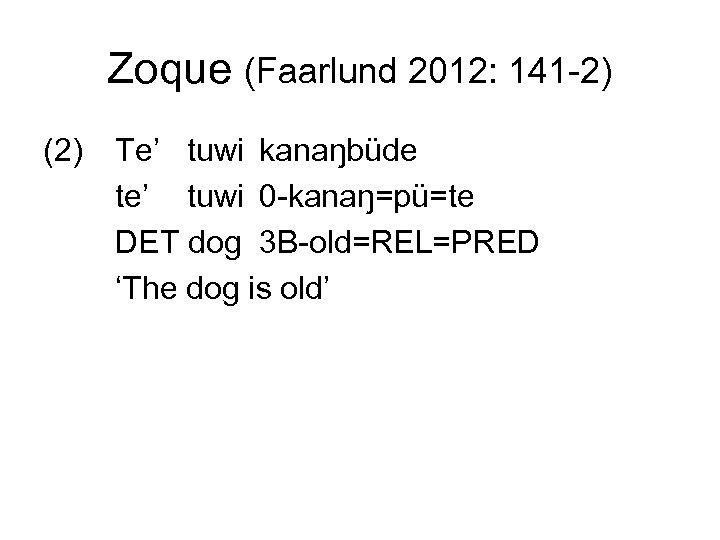

Zoque (Faarlund 2012: 141 -2) (2) Te’ tuwi kanaŋbüde te’ tuwi 0 -kanaŋ=pü=te DET dog 3 B-old=REL=PRED ‘The dog is old’

Zoque (Faarlund 2012: 141 -2) (2) Te’ tuwi kanaŋbüde te’ tuwi 0 -kanaŋ=pü=te DET dog 3 B-old=REL=PRED ‘The dog is old’

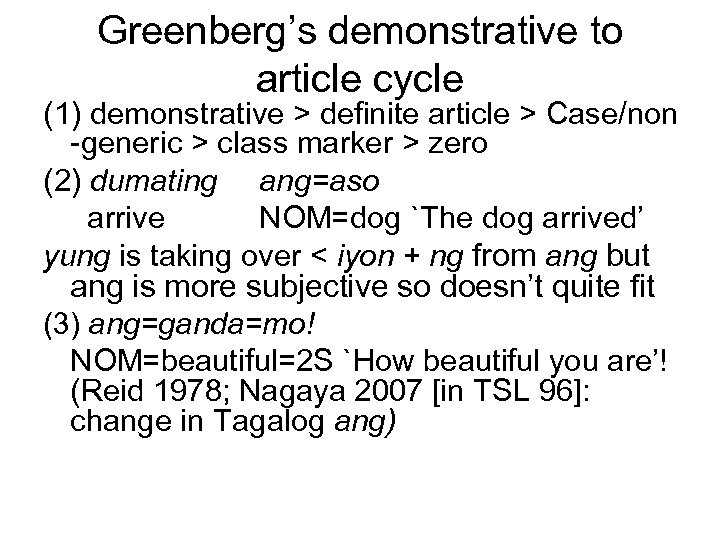

Greenberg’s demonstrative to article cycle (1) demonstrative > definite article > Case/non -generic > class marker > zero (2) dumating ang=aso arrive NOM=dog `The dog arrived’ yung is taking over < iyon + ng from ang but ang is more subjective so doesn’t quite fit (3) ang=ganda=mo! NOM=beautiful=2 S `How beautiful you are’! (Reid 1978; Nagaya 2007 [in TSL 96]: change in Tagalog ang)

Greenberg’s demonstrative to article cycle (1) demonstrative > definite article > Case/non -generic > class marker > zero (2) dumating ang=aso arrive NOM=dog `The dog arrived’ yung is taking over < iyon + ng from ang but ang is more subjective so doesn’t quite fit (3) ang=ganda=mo! NOM=beautiful=2 S `How beautiful you are’! (Reid 1978; Nagaya 2007 [in TSL 96]: change in Tagalog ang)

![Demonstrative [i-phi]/ [loc] article [u-phi] Dem C copula [i-phi] [u/i-T] [u-phi] [loc] Also: degree Demonstrative [i-phi]/ [loc] article [u-phi] Dem C copula [i-phi] [u/i-T] [u-phi] [loc] Also: degree](https://present5.com/presentation/345a4072c1b04cc61d1ecee581baa83e/image-64.jpg) Demonstrative [i-phi]/ [loc] article [u-phi] Dem C copula [i-phi] [u/i-T] [u-phi] [loc] Also: degree adverb and tense marker (Tibeto. Burman) and noun class marker.

Demonstrative [i-phi]/ [loc] article [u-phi] Dem C copula [i-phi] [u/i-T] [u-phi] [loc] Also: degree adverb and tense marker (Tibeto. Burman) and noun class marker.

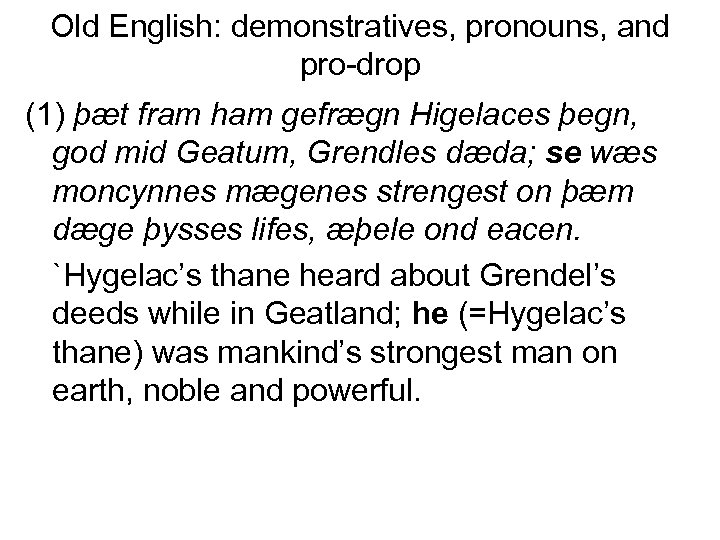

Old English: demonstratives, pronouns, and pro-drop (1) þæt fram ham gefrægn Higelaces þegn, god mid Geatum, Grendles dæda; se wæs moncynnes mægenes strengest on þæm dæge þysses lifes, æþele ond eacen. `Hygelac’s thane heard about Grendel’s deeds while in Geatland; he (=Hygelac’s thane) was mankind’s strongest man on earth, noble and powerful.

Old English: demonstratives, pronouns, and pro-drop (1) þæt fram ham gefrægn Higelaces þegn, god mid Geatum, Grendles dæda; se wæs moncynnes mægenes strengest on þæm dæge þysses lifes, æþele ond eacen. `Hygelac’s thane heard about Grendel’s deeds while in Geatland; he (=Hygelac’s thane) was mankind’s strongest man on earth, noble and powerful.

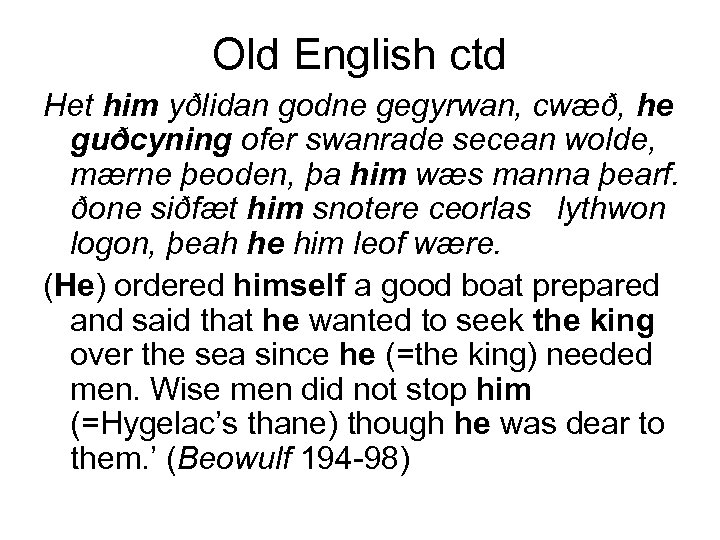

Old English ctd Het him yðlidan godne gegyrwan, cwæð, he guðcyning ofer swanrade secean wolde, mærne þeoden, þa him wæs manna þearf. ðone siðfæt him snotere ceorlas lythwon logon, þeah he him leof wære. (He) ordered himself a good boat prepared and said that he wanted to seek the king over the sea since he (=the king) needed men. Wise men did not stop him (=Hygelac’s thane) though he was dear to them. ’ (Beowulf 194 -98)

Old English ctd Het him yðlidan godne gegyrwan, cwæð, he guðcyning ofer swanrade secean wolde, mærne þeoden, þa him wæs manna þearf. ðone siðfæt him snotere ceorlas lythwon logon, þeah he him leof wære. (He) ordered himself a good boat prepared and said that he wanted to seek the king over the sea since he (=the king) needed men. Wise men did not stop him (=Hygelac’s thane) though he was dear to them. ’ (Beowulf 194 -98)

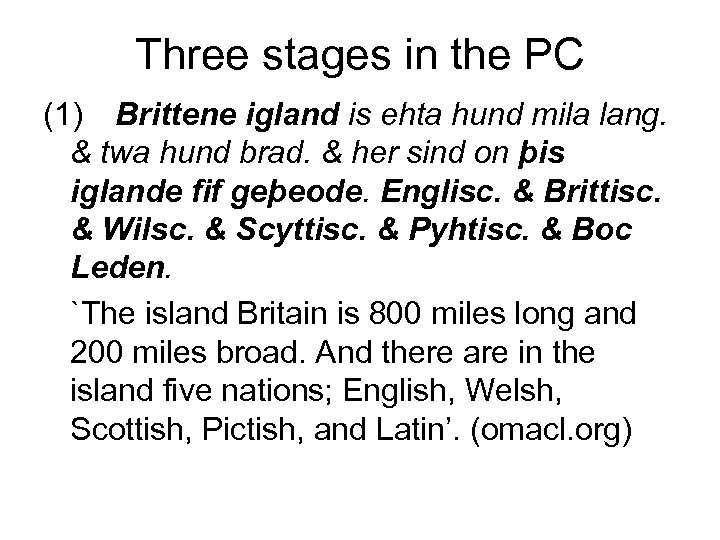

Three stages in the PC (1) Brittene igland is ehta hund mila lang. & twa hund brad. & her sind on þis iglande fif geþeode. Englisc. & Brittisc. & Wilsc. & Scyttisc. & Pyhtisc. & Boc Leden. `The island Britain is 800 miles long and 200 miles broad. And there are in the island five nations; English, Welsh, Scottish, Pictish, and Latin’. (omacl. org)

Three stages in the PC (1) Brittene igland is ehta hund mila lang. & twa hund brad. & her sind on þis iglande fif geþeode. Englisc. & Brittisc. & Wilsc. & Scyttisc. & Pyhtisc. & Boc Leden. `The island Britain is 800 miles long and 200 miles broad. And there are in the island five nations; English, Welsh, Scottish, Pictish, and Latin’. (omacl. org)

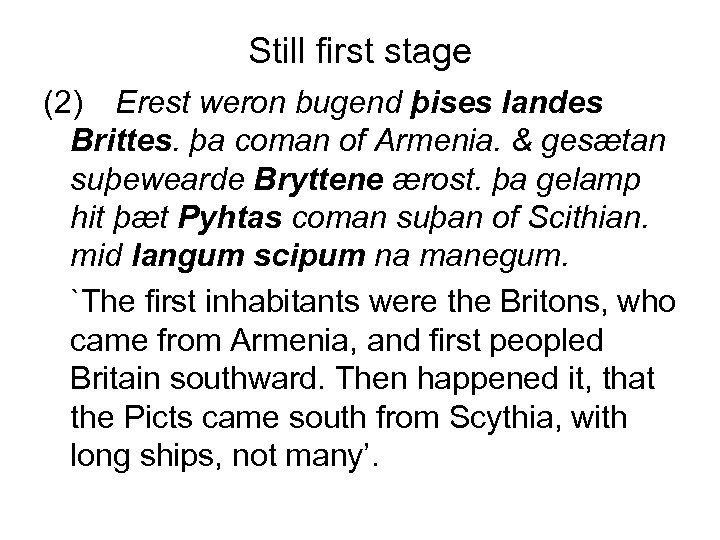

Still first stage (2) Erest weron bugend þises landes Brittes. þa coman of Armenia. & gesætan suþewearde Bryttene ærost. þa gelamp hit þæt Pyhtas coman suþan of Scithian. mid langum scipum na manegum. `The first inhabitants were the Britons, who came from Armenia, and first peopled Britain southward. Then happened it, that the Picts came south from Scythia, with long ships, not many’.

Still first stage (2) Erest weron bugend þises landes Brittes. þa coman of Armenia. & gesætan suþewearde Bryttene ærost. þa gelamp hit þæt Pyhtas coman suþan of Scithian. mid langum scipum na manegum. `The first inhabitants were the Britons, who came from Armenia, and first peopled Britain southward. Then happened it, that the Picts came south from Scythia, with long ships, not many’.

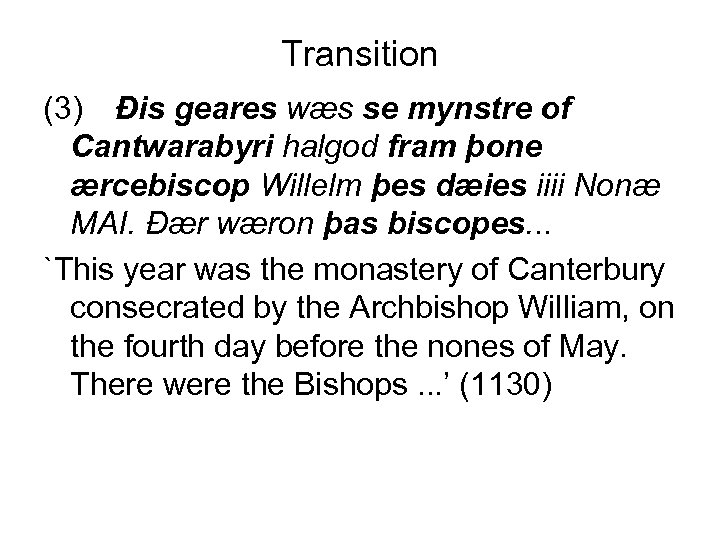

Transition (3) Đis geares wæs se mynstre of Cantwarabyri halgod fram þone ærcebiscop Willelm þes dæies iiii Nonæ MAI. Đær wæron þas biscopes. . . `This year was the monastery of Canterbury consecrated by the Archbishop William, on the fourth day before the nones of May. There were the Bishops. . . ’ (1130)

Transition (3) Đis geares wæs se mynstre of Cantwarabyri halgod fram þone ærcebiscop Willelm þes dæies iiii Nonæ MAI. Đær wæron þas biscopes. . . `This year was the monastery of Canterbury consecrated by the Archbishop William, on the fourth day before the nones of May. There were the Bishops. . . ’ (1130)

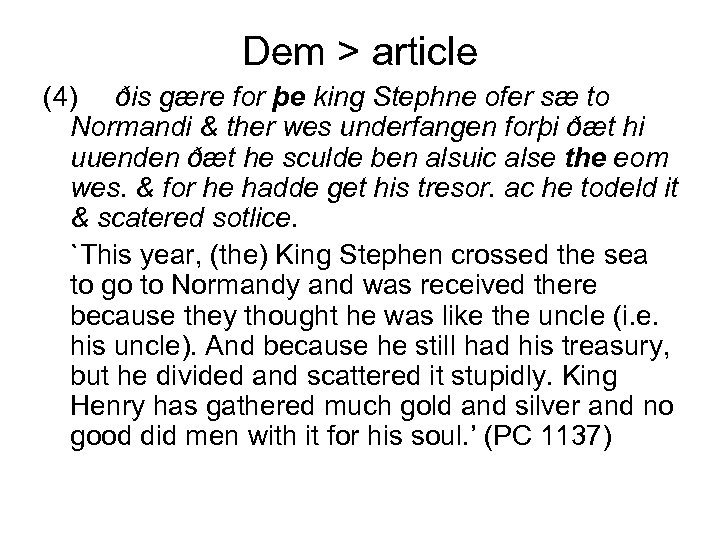

Dem > article (4) ðis gære for þe king Stephne ofer sæ to Normandi & ther wes underfangen forþi ðæt hi uuenden ðæt he sculde ben alsuic alse the eom wes. & for he hadde get his tresor. ac he todeld it & scatered sotlice. `This year, (the) King Stephen crossed the sea to go to Normandy and was received there because they thought he was like the uncle (i. e. his uncle). And because he still had his treasury, but he divided and scattered it stupidly. King Henry has gathered much gold and silver and no good did men with it for his soul. ’ (PC 1137)

Dem > article (4) ðis gære for þe king Stephne ofer sæ to Normandi & ther wes underfangen forþi ðæt hi uuenden ðæt he sculde ben alsuic alse the eom wes. & for he hadde get his tresor. ac he todeld it & scatered sotlice. `This year, (the) King Stephen crossed the sea to go to Normandy and was received there because they thought he was like the uncle (i. e. his uncle). And because he still had his treasury, but he divided and scattered it stupidly. King Henry has gathered much gold and silver and no good did men with it for his soul. ’ (PC 1137)

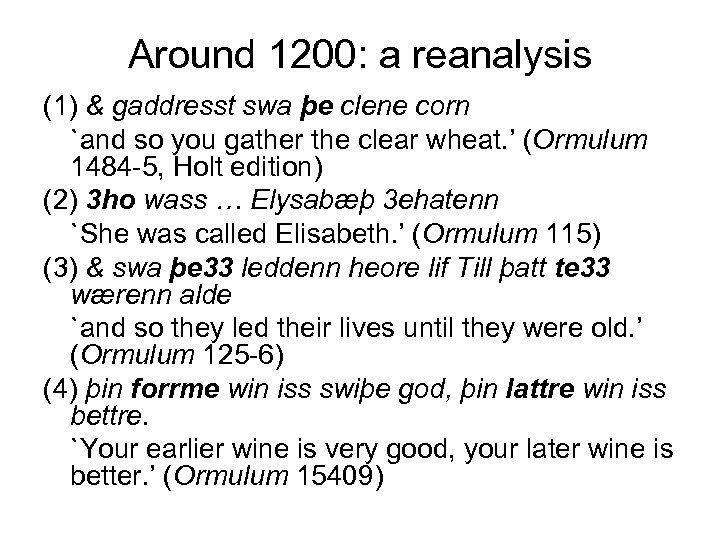

Around 1200: a reanalysis (1) & gaddresst swa þe clene corn `and so you gather the clear wheat. ’ (Ormulum 1484 -5, Holt edition) (2) 3 ho wass … Elysabæþ 3 ehatenn `She was called Elisabeth. ’ (Ormulum 115) (3) & swa þe 33 leddenn heore lif Till þatt te 33 wærenn alde `and so they led their lives until they were old. ’ (Ormulum 125 -6) (4) þin forrme win iss swiþe god, þin lattre win iss bettre. `Your earlier wine is very good, your later wine is better. ’ (Ormulum 15409)

Around 1200: a reanalysis (1) & gaddresst swa þe clene corn `and so you gather the clear wheat. ’ (Ormulum 1484 -5, Holt edition) (2) 3 ho wass … Elysabæþ 3 ehatenn `She was called Elisabeth. ’ (Ormulum 115) (3) & swa þe 33 leddenn heore lif Till þatt te 33 wærenn alde `and so they led their lives until they were old. ’ (Ormulum 125 -6) (4) þin forrme win iss swiþe god, þin lattre win iss bettre. `Your earlier wine is very good, your later wine is better. ’ (Ormulum 15409)

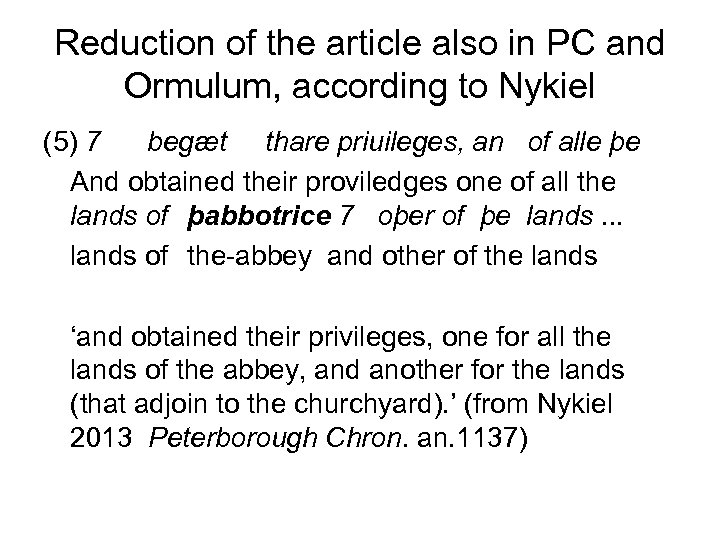

Reduction of the article also in PC and Ormulum, according to Nykiel (5) 7 begæt thare priuileges, an of alle þe And obtained their proviledges one of all the lands of þabbotrice 7 oþer of þe lands. . . lands of the-abbey and other of the lands ‘and obtained their privileges, one for all the lands of the abbey, and another for the lands (that adjoin to the churchyard). ’ (from Nykiel 2013 Peterborough Chron. an. 1137)

Reduction of the article also in PC and Ormulum, according to Nykiel (5) 7 begæt thare priuileges, an of alle þe And obtained their proviledges one of all the lands of þabbotrice 7 oþer of þe lands. . . lands of the-abbey and other of the lands ‘and obtained their privileges, one for all the lands of the abbey, and another for the lands (that adjoin to the churchyard). ’ (from Nykiel 2013 Peterborough Chron. an. 1137)

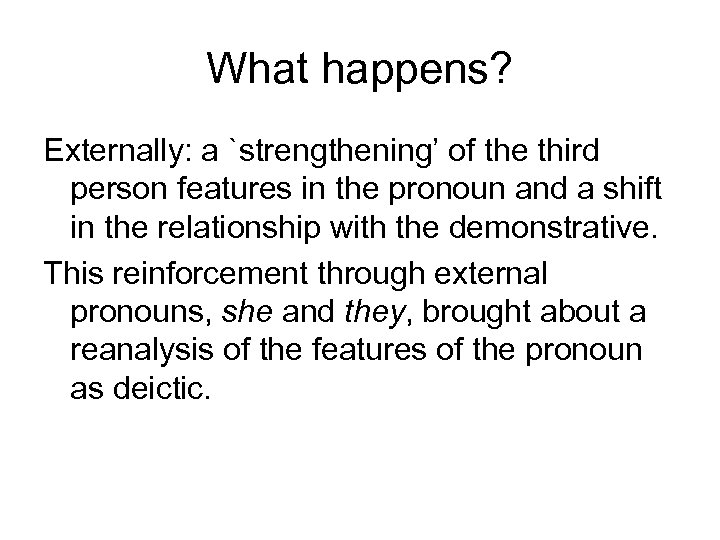

What happens? Externally: a `strengthening’ of the third person features in the pronoun and a shift in the relationship with the demonstrative. This reinforcement through external pronouns, she and they, brought about a reanalysis of the features of the pronoun as deictic.

What happens? Externally: a `strengthening’ of the third person features in the pronoun and a shift in the relationship with the demonstrative. This reinforcement through external pronouns, she and they, brought about a reanalysis of the features of the pronoun as deictic.

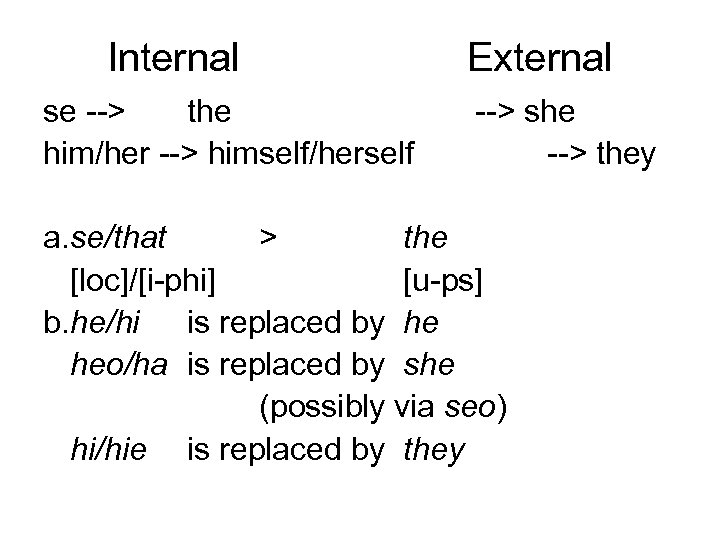

Internal se --> the him/her --> himself/herself External --> she --> they a. se/that > the [loc]/[i-phi] [u-ps] b. he/hi is replaced by he heo/ha is replaced by she (possibly via seo) hi/hie is replaced by they

Internal se --> the him/her --> himself/herself External --> she --> they a. se/that > the [loc]/[i-phi] [u-ps] b. he/hi is replaced by he heo/ha is replaced by she (possibly via seo) hi/hie is replaced by they

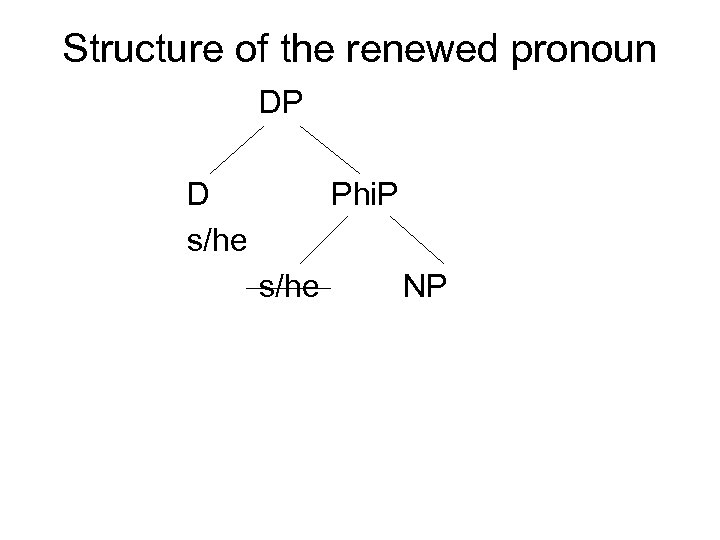

Structure of the renewed pronoun DP D s/he Phi. P s/he NP

Structure of the renewed pronoun DP D s/he Phi. P s/he NP

![Typical DP Cycle DP that [loc] [i-ps] D > D’ DP D the NP Typical DP Cycle DP that [loc] [i-ps] D > D’ DP D the NP](https://present5.com/presentation/345a4072c1b04cc61d1ecee581baa83e/image-76.jpg) Typical DP Cycle DP that [loc] [i-ps] D > D’ DP D the NP [u-phi] 3 S NP 3 S

Typical DP Cycle DP that [loc] [i-ps] D > D’ DP D the NP [u-phi] 3 S NP 3 S

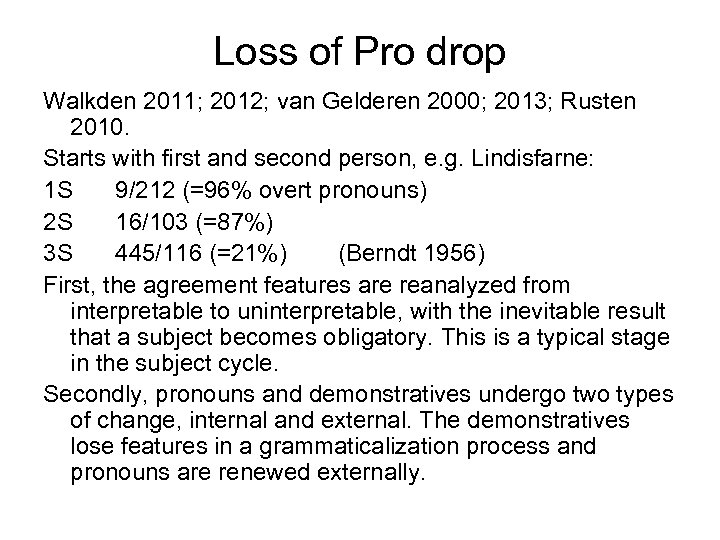

Loss of Pro drop Walkden 2011; 2012; van Gelderen 2000; 2013; Rusten 2010. Starts with first and second person, e. g. Lindisfarne: 1 S 9/212 (=96% overt pronouns) 2 S 16/103 (=87%) 3 S 445/116 (=21%) (Berndt 1956) First, the agreement features are reanalyzed from interpretable to uninterpretable, with the inevitable result that a subject becomes obligatory. This is a typical stage in the subject cycle. Secondly, pronouns and demonstratives undergo two types of change, internal and external. The demonstratives lose features in a grammaticalization process and pronouns are renewed externally.

Loss of Pro drop Walkden 2011; 2012; van Gelderen 2000; 2013; Rusten 2010. Starts with first and second person, e. g. Lindisfarne: 1 S 9/212 (=96% overt pronouns) 2 S 16/103 (=87%) 3 S 445/116 (=21%) (Berndt 1956) First, the agreement features are reanalyzed from interpretable to uninterpretable, with the inevitable result that a subject becomes obligatory. This is a typical stage in the subject cycle. Secondly, pronouns and demonstratives undergo two types of change, internal and external. The demonstratives lose features in a grammaticalization process and pronouns are renewed externally.

Noun > # Lehmann (2002: 50 -54, quoting Heine & Reh 1984: 273): 3 sources of nominal number marking: (a) from a noun, as with Chinese men meaning `class’, (b) from a pronoun, numeral, or quantifier (c) from a numeral classifier: the classifier ge is the main classifier now in spoken Mandarin and is becoming used as singular, instead of yi-ge `one -CL’ (Lehmann 2002: 54; see also Serzisko 1982: 24).

Noun > # Lehmann (2002: 50 -54, quoting Heine & Reh 1984: 273): 3 sources of nominal number marking: (a) from a noun, as with Chinese men meaning `class’, (b) from a pronoun, numeral, or quantifier (c) from a numeral classifier: the classifier ge is the main classifier now in spoken Mandarin and is becoming used as singular, instead of yi-ge `one -CL’ (Lehmann 2002: 54; see also Serzisko 1982: 24).

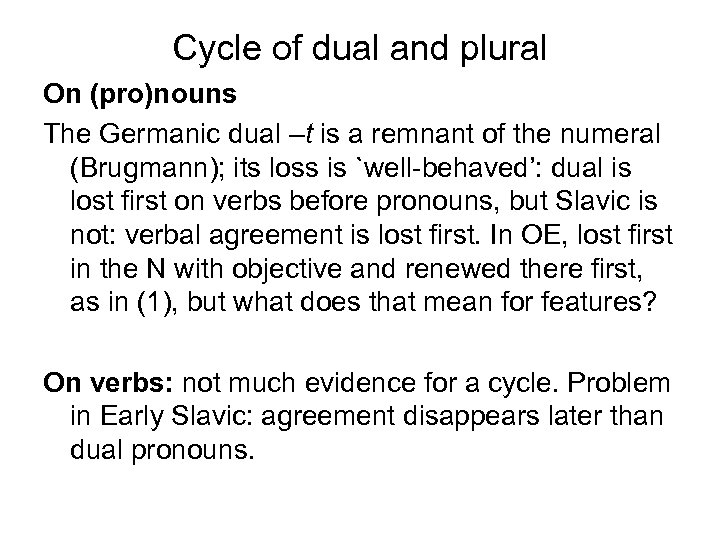

Cycle of dual and plural On (pro)nouns The Germanic dual –t is a remnant of the numeral (Brugmann); its loss is `well-behaved’: dual is lost first on verbs before pronouns, but Slavic is not: verbal agreement is lost first. In OE, lost first in the N with objective and renewed there first, as in (1), but what does that mean for features? On verbs: not much evidence for a cycle. Problem in Early Slavic: agreement disappears later than dual pronouns.

Cycle of dual and plural On (pro)nouns The Germanic dual –t is a remnant of the numeral (Brugmann); its loss is `well-behaved’: dual is lost first on verbs before pronouns, but Slavic is not: verbal agreement is lost first. In OE, lost first in the N with objective and renewed there first, as in (1), but what does that mean for features? On verbs: not much evidence for a cycle. Problem in Early Slavic: agreement disappears later than dual pronouns.

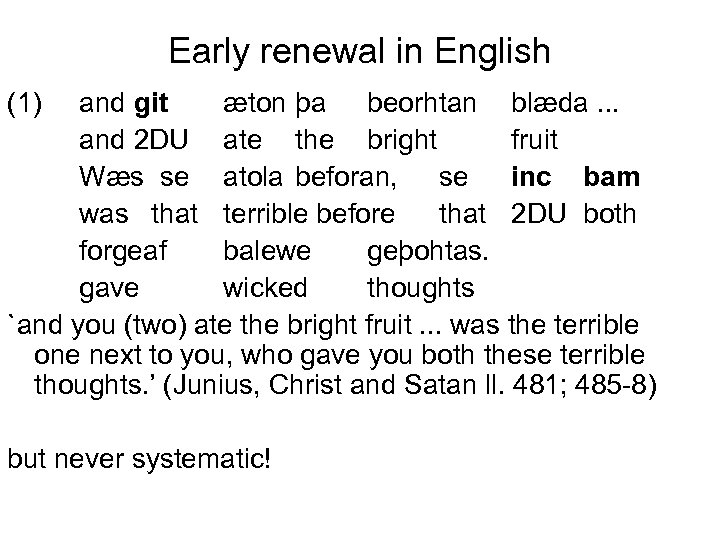

Early renewal in English (1) and git æton þa beorhtan blæda. . . and 2 DU ate the bright fruit Wæs se atola beforan, se inc bam was that terrible before that 2 DU both forgeaf balewe geþohtas. gave wicked thoughts `and you (two) ate the bright fruit. . . was the terrible one next to you, who gave you both these terrible thoughts. ’ (Junius, Christ and Satan ll. 481; 485 -8) but never systematic!

Early renewal in English (1) and git æton þa beorhtan blæda. . . and 2 DU ate the bright fruit Wæs se atola beforan, se inc bam was that terrible before that 2 DU both forgeaf balewe geþohtas. gave wicked thoughts `and you (two) ate the bright fruit. . . was the terrible one next to you, who gave you both these terrible thoughts. ’ (Junius, Christ and Satan ll. 481; 485 -8) but never systematic!

Noun > gender > diminuative -heit in German/-hood in English problem of derivational > inflectional (1) An god. . on þreom hadan. one god. . . in three persons (c 1175 Lamb. Hom. 99) (2) Hæleþa leofost on gesiðes had. . state Beowulf 1297 Croft Aikhenvald

Noun > gender > diminuative -heit in German/-hood in English problem of derivational > inflectional (1) An god. . on þreom hadan. one god. . . in three persons (c 1175 Lamb. Hom. 99) (2) Hæleþa leofost on gesiðes had. . state Beowulf 1297 Croft Aikhenvald

Types of minimalist features The semantic features of lexical items (which have to be cognitively based) The interpretable ones relevant at the Conceptual-Intentional interface. Uninterpretable features act as `glue’ so to speak to help out merge. For instance, person and number features (=phifeatures) are interpretable on nouns but not on verbs.

Types of minimalist features The semantic features of lexical items (which have to be cognitively based) The interpretable ones relevant at the Conceptual-Intentional interface. Uninterpretable features act as `glue’ so to speak to help out merge. For instance, person and number features (=phifeatures) are interpretable on nouns but not on verbs.

The importance of features Chomsky (1965: 87 -88): lexicon contains information for the phonological, semantic, and syntactic component. Sincerity +N, -Count, +Abstract. . . ) Chomsky (1995: 230 ff; 236; 277 ff): semantic (e. g. abstract object), phonological (e. g. the sounds), and formal features: intrinsic or optional.

The importance of features Chomsky (1965: 87 -88): lexicon contains information for the phonological, semantic, and syntactic component. Sincerity +N, -Count, +Abstract. . . ) Chomsky (1995: 230 ff; 236; 277 ff): semantic (e. g. abstract object), phonological (e. g. the sounds), and formal features: intrinsic or optional.

![Formal features are: interpretable and uninterpretable (1995: 277): airplane Interpr. [nominal] [3 person] [non-human] Formal features are: interpretable and uninterpretable (1995: 277): airplane Interpr. [nominal] [3 person] [non-human]](https://present5.com/presentation/345a4072c1b04cc61d1ecee581baa83e/image-84.jpg) Formal features are: interpretable and uninterpretable (1995: 277): airplane Interpr. [nominal] [3 person] [non-human] Uninterpr [Case] build [verbal] [assign accusative] [phi]

Formal features are: interpretable and uninterpretable (1995: 277): airplane Interpr. [nominal] [3 person] [non-human] Uninterpr [Case] build [verbal] [assign accusative] [phi]

![Simplifying checking He before checking after checking reads books [i-3 S] [u-phi] [i-3 P] Simplifying checking He before checking after checking reads books [i-3 S] [u-phi] [i-3 P]](https://present5.com/presentation/345a4072c1b04cc61d1ecee581baa83e/image-85.jpg) Simplifying checking He before checking after checking reads books [i-3 S] [u-phi] [i-3 P] That’s why `me sees him’ is ok!

Simplifying checking He before checking after checking reads books [i-3 S] [u-phi] [i-3 P] That’s why `me sees him’ is ok!

Semantic and formal overlap: Chomsky (1995: 230; 381) suggests: "formal features have semantic correlates and reflect semantic properties (accusative Case and transitivity, for example). " I interpret this: If a language has nouns with semantic phi-features, the learner will be able to hypothesize uninterpretable features on another F (and will be able to bundle them there).

Semantic and formal overlap: Chomsky (1995: 230; 381) suggests: "formal features have semantic correlates and reflect semantic properties (accusative Case and transitivity, for example). " I interpret this: If a language has nouns with semantic phi-features, the learner will be able to hypothesize uninterpretable features on another F (and will be able to bundle them there).

Feature Economy (a) Utilize semantic features: use them as for functional categories, i. e. as formal features. (b) If a specific feature appears more than once, one of these is interpretable and the others are uninterpretable

Feature Economy (a) Utilize semantic features: use them as for functional categories, i. e. as formal features. (b) If a specific feature appears more than once, one of these is interpretable and the others are uninterpretable

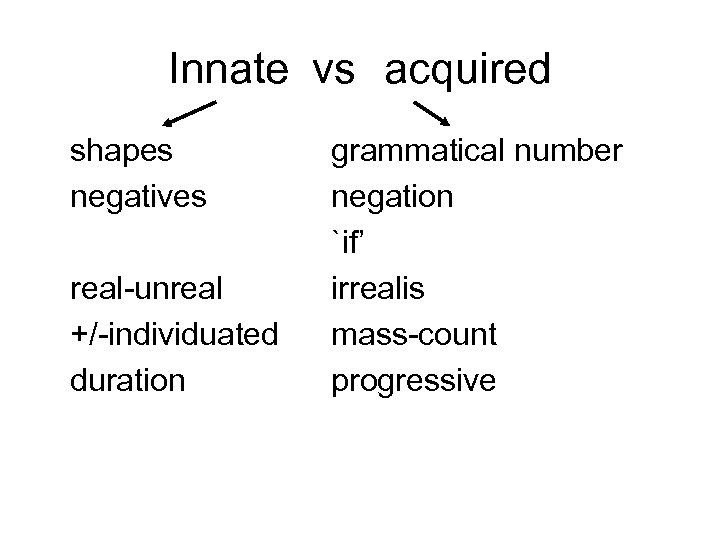

Innate vs acquired shapes negatives real-unreal +/-individuated duration grammatical number negation `if’ irrealis mass-count progressive

Innate vs acquired shapes negatives real-unreal +/-individuated duration grammatical number negation `if’ irrealis mass-count progressive

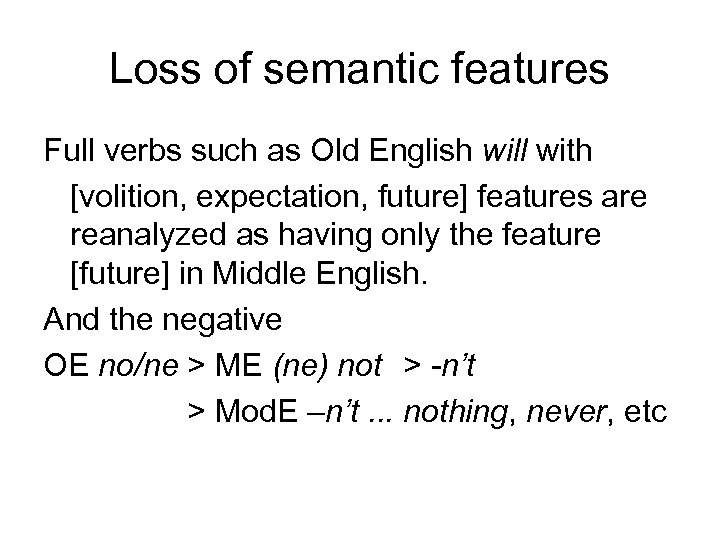

Loss of semantic features Full verbs such as Old English will with [volition, expectation, future] features are reanalyzed as having only the feature [future] in Middle English. And the negative OE no/ne > ME (ne) not > -n’t > Mod. E –n’t. . . nothing, never, etc

Loss of semantic features Full verbs such as Old English will with [volition, expectation, future] features are reanalyzed as having only the feature [future] in Middle English. And the negative OE no/ne > ME (ne) not > -n’t > Mod. E –n’t. . . nothing, never, etc

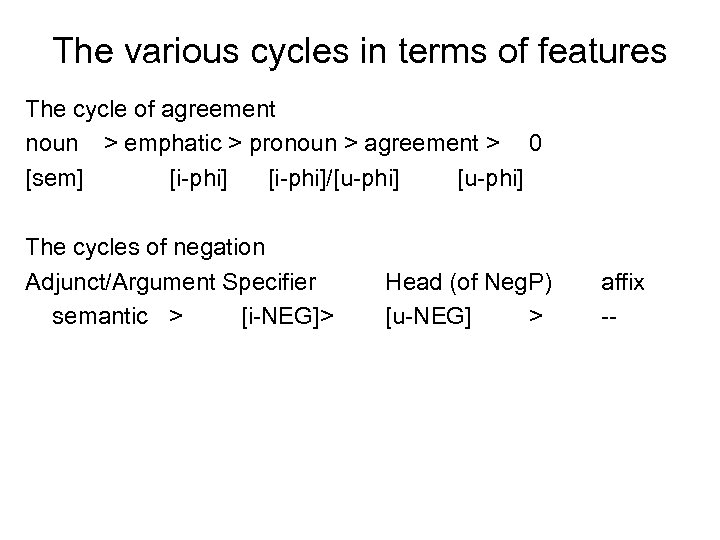

The various cycles in terms of features The cycle of agreement noun > emphatic > pronoun > agreement > 0 [sem] [i-phi]/[u-phi] The cycles of negation Adjunct/Argument Specifier semantic > [i-NEG]> Head (of Neg. P) [u-NEG] > affix --

The various cycles in terms of features The cycle of agreement noun > emphatic > pronoun > agreement > 0 [sem] [i-phi]/[u-phi] The cycles of negation Adjunct/Argument Specifier semantic > [i-NEG]> Head (of Neg. P) [u-NEG] > affix --

![Demonstrative [i-phi] [i-loc] article [u-phi] pronoun C [i-phi] [u-T] copula [i-loc] Demonstrative [i-phi] [i-loc] article [u-phi] pronoun C [i-phi] [u-T] copula [i-loc]](https://present5.com/presentation/345a4072c1b04cc61d1ecee581baa83e/image-91.jpg) Demonstrative [i-phi] [i-loc] article [u-phi] pronoun C [i-phi] [u-T] copula [i-loc]

Demonstrative [i-phi] [i-loc] article [u-phi] pronoun C [i-phi] [u-T] copula [i-loc]

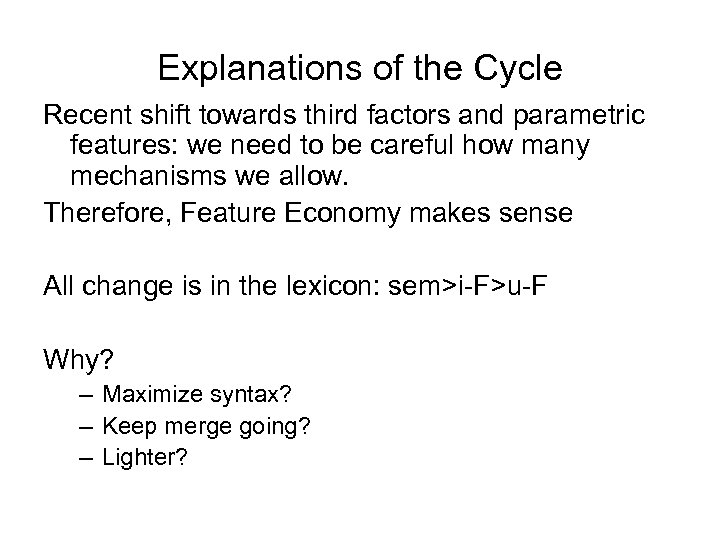

Explanations of the Cycle Recent shift towards third factors and parametric features: we need to be careful how many mechanisms we allow. Therefore, Feature Economy makes sense All change is in the lexicon: sem>i-F>u-F Why? – Maximize syntax? – Keep merge going? – Lighter?

Explanations of the Cycle Recent shift towards third factors and parametric features: we need to be careful how many mechanisms we allow. Therefore, Feature Economy makes sense All change is in the lexicon: sem>i-F>u-F Why? – Maximize syntax? – Keep merge going? – Lighter?

Acquisition, Sign Language, . . . Unidirectional change in sign language e. g. Aronoff et al; Fisher & Gough; Pfau & Steinbach: V>ASP, N > AGR, and L 1 Acquisition e. g. Brown (1973); Josefsson & Håkansson (2000) Interlanguage: debate as to features Lardiere (2007), Hawkins (2005), Tsimpli et al (2004) Pre-human features: place, duration, negation. . .

Acquisition, Sign Language, . . . Unidirectional change in sign language e. g. Aronoff et al; Fisher & Gough; Pfau & Steinbach: V>ASP, N > AGR, and L 1 Acquisition e. g. Brown (1973); Josefsson & Håkansson (2000) Interlanguage: debate as to features Lardiere (2007), Hawkins (2005), Tsimpli et al (2004) Pre-human features: place, duration, negation. . .

Conclusions Generative Grammar and Historical Linguistics provide insights to each other Introspection and corpora/texts Gradual, unidirectional change provides a window on the language faculty Role of UG determines what changes: PS rules > parameters > features We looked at four cycles and some challenges

Conclusions Generative Grammar and Historical Linguistics provide insights to each other Introspection and corpora/texts Gradual, unidirectional change provides a window on the language faculty Role of UG determines what changes: PS rules > parameters > features We looked at four cycles and some challenges

New directions with cycles 25 -26 April 2014: Linguistic Cycle Workshop II at ASU; deadline for abstracts is 31 October 2013; http: //linguistlist. org/callconf/browse-confaction. cfm? Conf. ID=163258

New directions with cycles 25 -26 April 2014: Linguistic Cycle Workshop II at ASU; deadline for abstracts is 31 October 2013; http: //linguistlist. org/callconf/browse-confaction. cfm? Conf. ID=163258