9f80322cf4e96ad7944f27e859a6bb32.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 104

Frank Cowell: UB Public Economics June 2005 Deprivation, Complaints and Inequality Public Economics: University of Barcelona Frank Cowell http: //darp. lse. ac. uk/ub

Frank Cowell: Overview. . . Deprivation, complaints, inequality UB Public Economics Experimental approaches Background to further work Deprivation Complaints Claims

Frank Cowell: Agenda UB Public Economics n n n Begin with a look at some empirical work To what extent are ideas in previous lectures supported? Focus on u Risk and inequality aversion u The fundamental axioms u The context of distributional comparisons u Role of personal characteristics

Frank Cowell: Risk and inequality aversion UB Public Economics n n Examine preferences for risk and inequality u Carlsson et al 2005 u Use imagined societies and lotteries. u Willingness to provide for grandchildren? Relative risk aversion is between 2 and 3. Social inequality aversion? Most people also individually inequality averse u Willing to pay for living in a more equal society u Left-wing voters and women are both more risk and inequality averse than others.

Frank Cowell: Background UB Public Economics n Research programme by Amiel and Cowell u u n n Several references summarised in Amiel-Cowell (1999) Recent work in Amiel et al (2005) Examine the extent to which individual axioms are supported. Also the role of personal characteristics u u sex age economics education political views

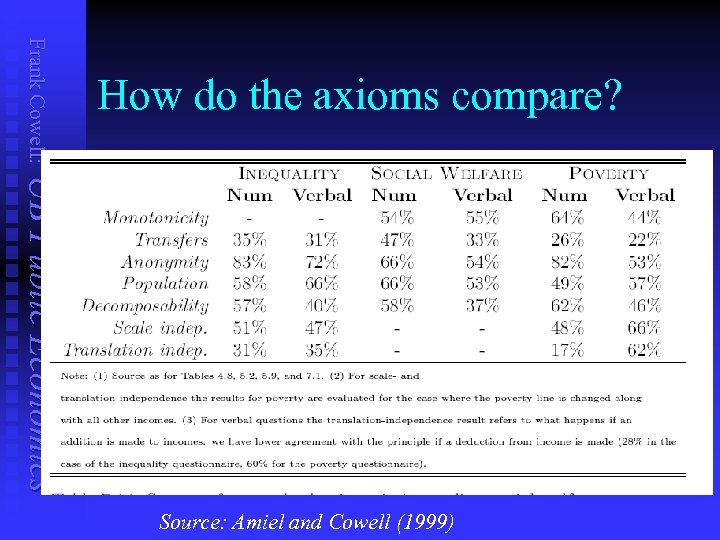

Frank Cowell: How do the axioms compare? UB Public Economics Source: Amiel and Cowell (1999)

Frank Cowell: Recent work UB Public Economics n n Part of a research programme that focuses on the way people perceive issues Lesson 1 from the past: individuals consistently reject some of the core principles u u n Lesson 2 from the past: context may be important u u n Pareto principle Transfer principle Inequality Welfare… Can we pin down the context effect?

Frank Cowell: Beginnings of an approach UB Public Economics n n Set up a joint “questionnaire experiment” Simultaneously use a variety of ethical settings u u n n Same experiment in different flavour Should the “flavouring” matter? Systematic differences across settings? Special personal characteristics predispose a particular set of attitudes? Throw light on the ethical basis for concern with distributional issues? What issues?

Frank Cowell: Distributional issues UB Public Economics n n n Could look at questions of monotonicity / Pareto principle Transfer principle Close relation to mean-preserving spread principle Serious question here at heart of inequality and risk analysis Recall the transfer principle example…

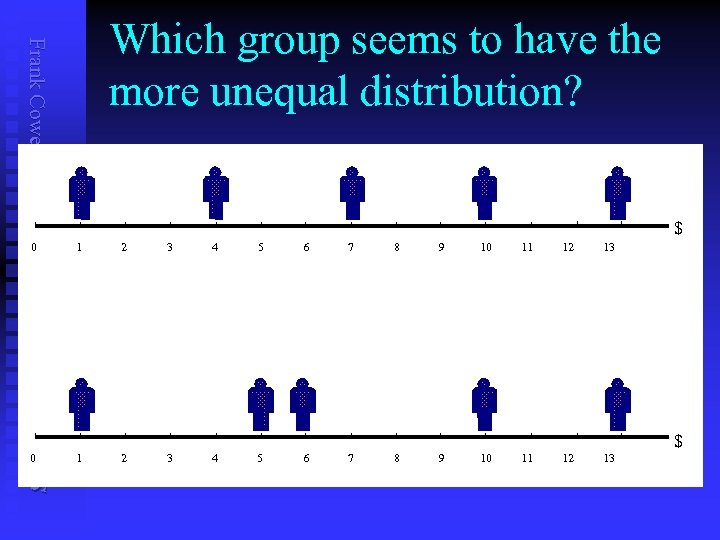

Frank Cowell: Which group seems to have the more unequal distribution? UB Public Economics 0 0 $ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

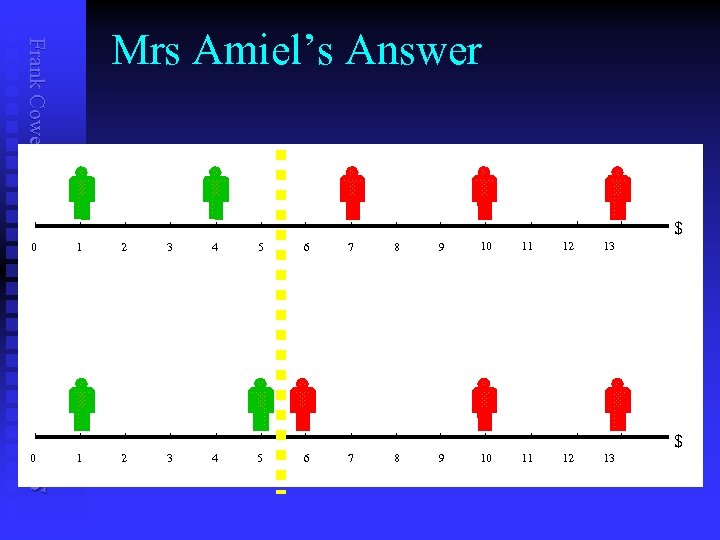

Frank Cowell: 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 $ $ UB Public Economics 1 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 Mrs Amiel’s Answer

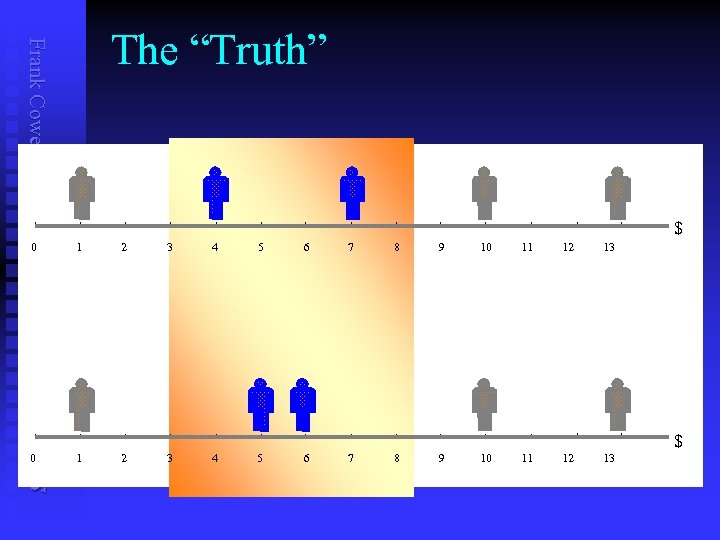

Frank Cowell: 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 $ $ UB Public Economics 1 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 The “Truth”

Frank Cowell: What if we had used a different distributional criterion? n UB Public Economics n n Following Atkinson, inequality rankings should derive from social welfare rankings Likewise risk rankings should derive from preference rankings What would have happened if we changed the context of the question? u u n Should just be a matter of changing the flavour Not the substance Consider the risk-inequality relation

Frank Cowell: Harsanyi: the two models UB Public Economics n n There may be conceptual problems Are the models actually distinct? Nevertheless, an important foundation of modern utilitarianism Should be susceptible of investigation as with the inequality questionnaire experiments

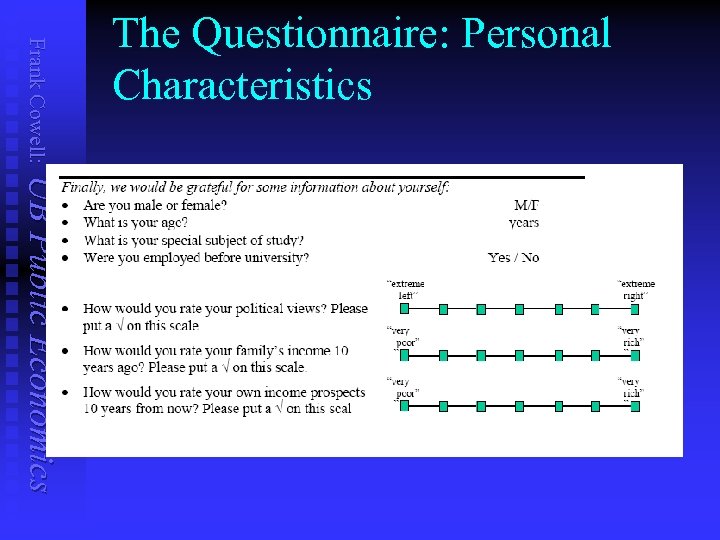

Frank Cowell: Outline of Approach UB Public Economics n Questionnaire responses of international group of over 1000 students n Questionnaire experiments were run during 2003 n Each session run during lecture/class time n Questionnaire consisted of a combination of (related) numerical problems and a verbal question n Experiment was anonymous, but individuals were asked about personal characteristics

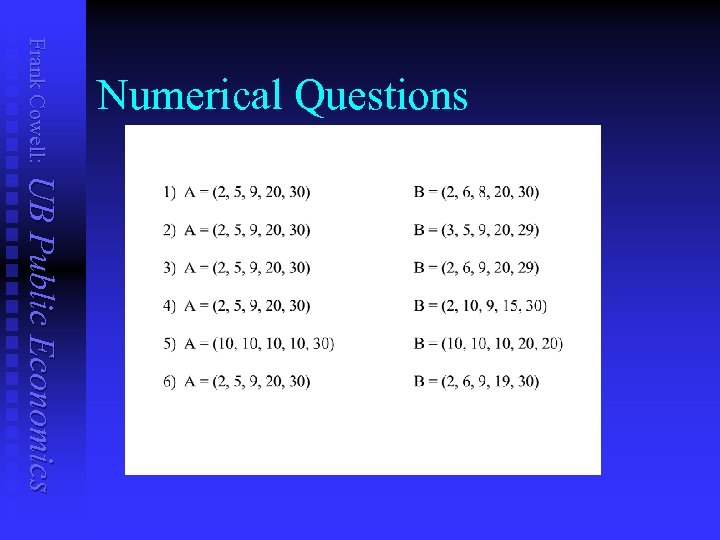

Frank Cowell: The setting n UB Public Economics n An imaginary country: Alfaland Consists of 5 regions u u n One of two policies A, B is to be implemented u n distributional consequences are known What is respondent’s judgment on the outcomes? u u n equality of income within each region income of each region depends on policy chosen. Do this for six scenarios Allow for indifference An example…

Frank Cowell: The Questionnaire UB Public Economics

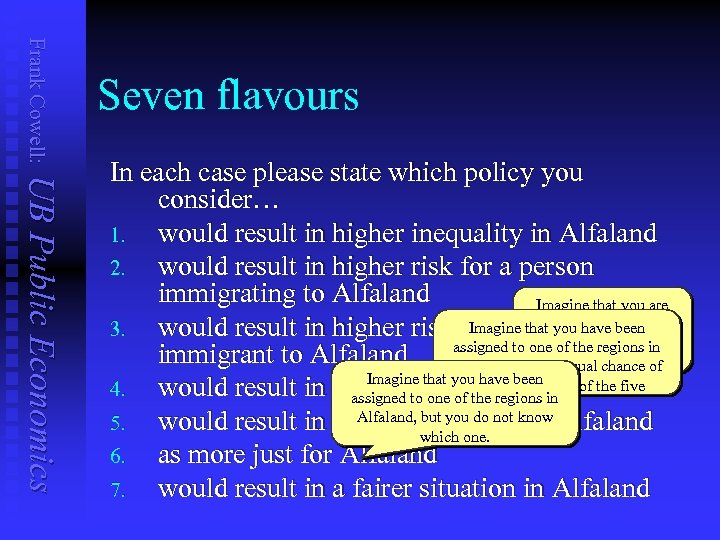

Frank Cowell: Seven flavours UB Public Economics In each case please state which policy you consider… 1. would result in higher inequality in Alfaland 2. would result in higher risk for a person immigrating to Alfaland Imagine that you are invited have Imagine that you an been 3. would result in higher risk for you as to be an outside observer regions in assigned to one of theof Alfaland. immigrant to Alfaland with an equal chance of Imagine that you havein any one of the five better one of being been 4. would result in a assigned to situation inin. Alfaland the regions. Alfaland, but you do not know Alfaland 5. would result in a better situation in which one. 6. as more just for Alfaland would result in a fairer situation in Alfaland 7.

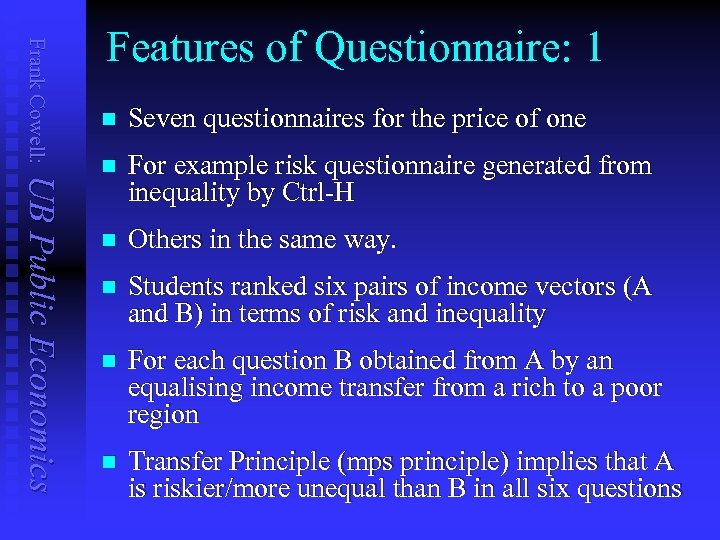

Frank Cowell: Features of Questionnaire: 1 UB Public Economics n Seven questionnaires for the price of one n For example risk questionnaire generated from inequality by Ctrl-H n Others in the same way. n Students ranked six pairs of income vectors (A and B) in terms of risk and inequality n For each question B obtained from A by an equalising income transfer from a rich to a poor region n Transfer Principle (mps principle) implies that A is riskier/more unequal than B in all six questions

Frank Cowell: Numerical Questions UB Public Economics

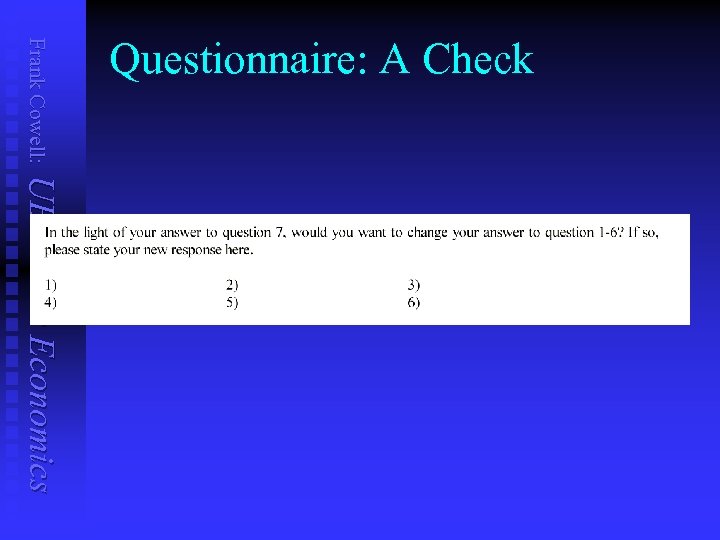

Frank Cowell: Features of Questionnaire 2 UB Public Economics n Check the numerical responses with a verbal question n Using the same story we present the issue of the principle of transfers n Then see if they want to change their minds on the numerical problems

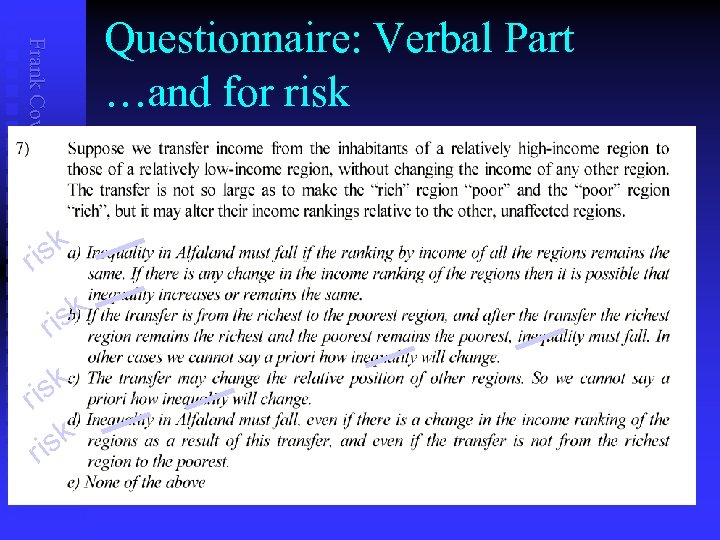

Frank Cowell: sk ri UB Public Economics sk ri Questionnaire: Verbal Part …and for risk

Frank Cowell: Questionnaire: A Check UB Public Economics

Frank Cowell: The Questionnaire: Personal Characteristics UB Public Economics

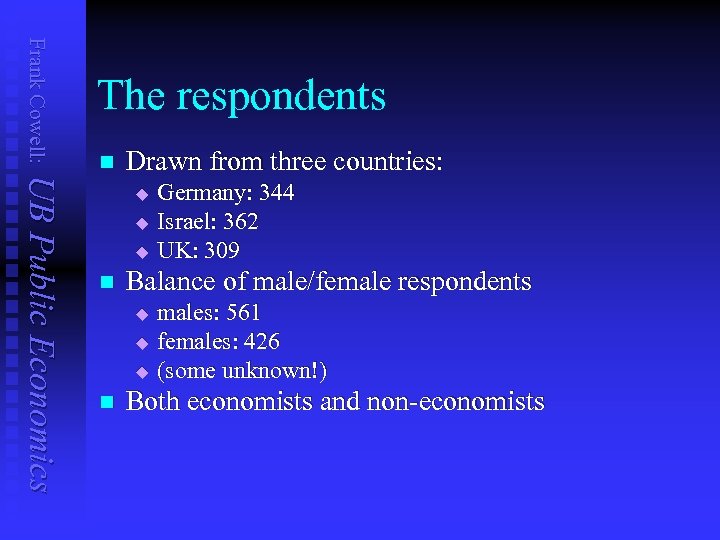

Frank Cowell: The respondents n UB Public Economics Drawn from three countries: u u u n Balance of male/female respondents u u u n Germany: 344 Israel: 362 UK: 309 males: 561 females: 426 (some unknown!) Both economists and non-economists

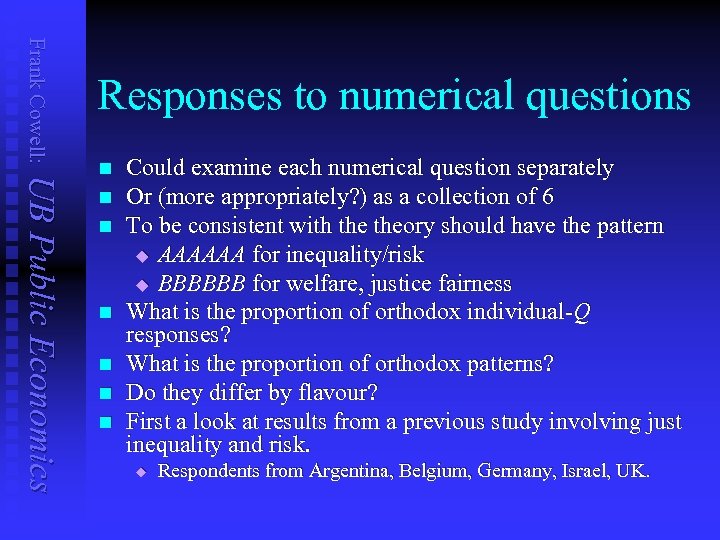

Frank Cowell: Responses to numerical questions UB Public Economics n n n n Could examine each numerical question separately Or (more appropriately? ) as a collection of 6 To be consistent with theory should have the pattern u AAAAAA for inequality/risk u BBBBBB for welfare, justice fairness What is the proportion of orthodox individual-Q responses? What is the proportion of orthodox patterns? Do they differ by flavour? First a look at results from a previous study involving just inequality and risk. u Respondents from Argentina, Belgium, Germany, Israel, UK.

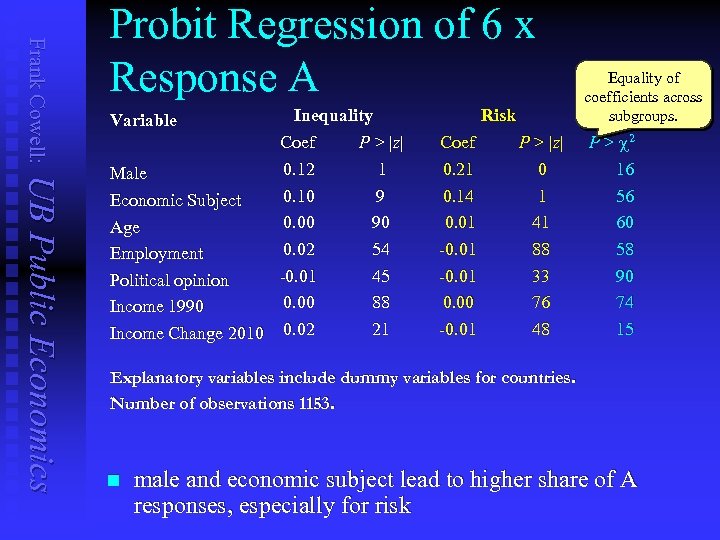

Frank Cowell: Probit Regression of 6 x Response A Variable Inequality Coef P > | z| UB Public Economics 0. 12 Male 0. 10 Economic Subject 0. 00 Age 0. 02 Employment -0. 01 Political opinion 0. 00 Income 1990 Income Change 2010 0. 02 1 9 90 54 45 88 21 Risk Coef 0. 21 0. 14 0. 01 -0. 01 0. 00 -0. 01 P > | z| 0 1 41 88 33 76 48 Equality of coefficients across subgroups. P > c 2 16 56 60 58 90 74 15 Explanatory variables include dummy variables for countries. Number of observations 1153. n male and economic subject lead to higher share of A responses, especially for risk

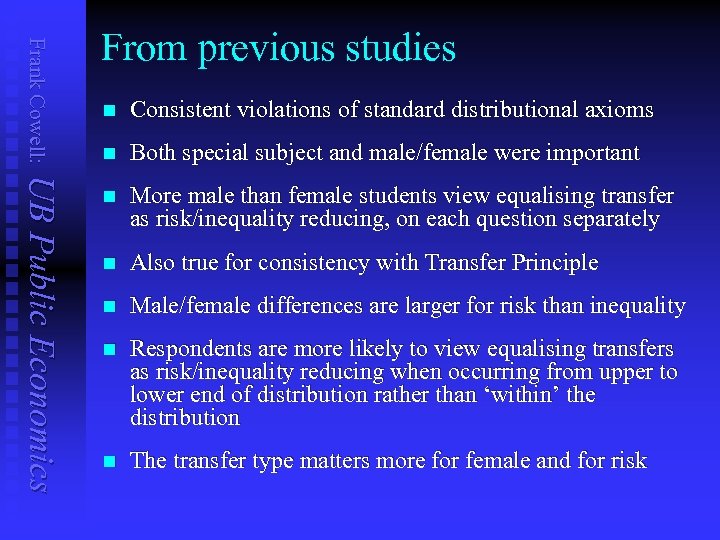

Frank Cowell: From previous studies UB Public Economics n Consistent violations of standard distributional axioms n Both special subject and male/female were important n More male than female students view equalising transfer as risk/inequality reducing, on each question separately n Also true for consistency with Transfer Principle n Male/female differences are larger for risk than inequality n Respondents are more likely to view equalising transfers as risk/inequality reducing when occurring from upper to lower end of distribution rather than ‘within’ the distribution n The transfer type matters more for female and for risk

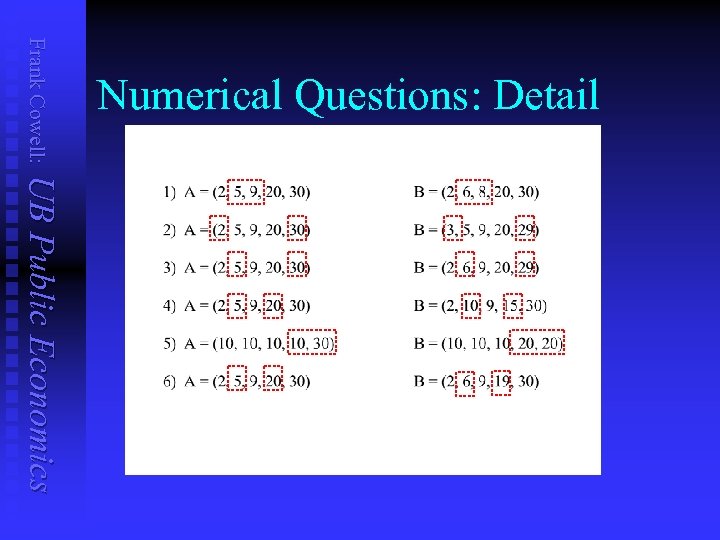

Frank Cowell: Numerical Questions: Detail UB Public Economics

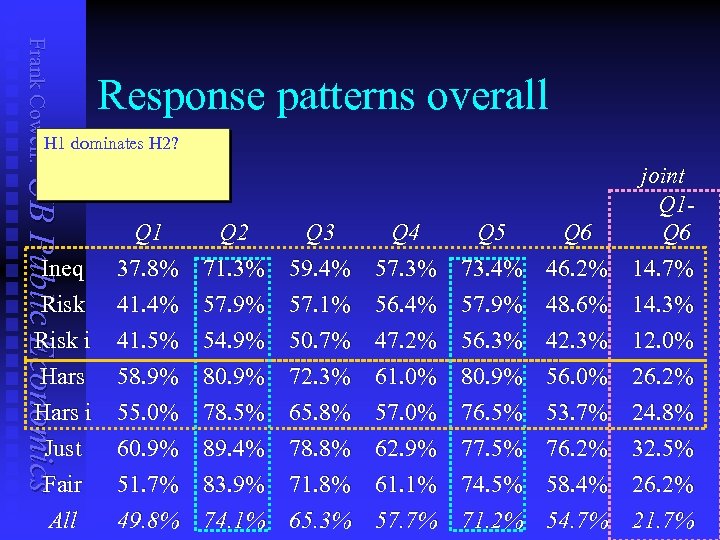

Frank Cowell: Response patterns overall UB Public Economics H 1 dominates H 2? Cases involving “Negative” questions Strict adherence to extremes orthodox get fewer get low axiom is verymore support answers Ineq Risk i Hars i Just Fair All Q 1 37. 8% 41. 4% 41. 5% 58. 9% 55. 0% 60. 9% 51. 7% 49. 8% Q 2 71. 3% 57. 9% 54. 9% 80. 9% 78. 5% 89. 4% 83. 9% 74. 1% Q 3 59. 4% 57. 1% 50. 7% 72. 3% 65. 8% 78. 8% 71. 8% 65. 3% Q 4 57. 3% 56. 4% 47. 2% 61. 0% 57. 0% 62. 9% 61. 1% 57. 7% Q 5 73. 4% 57. 9% 56. 3% 80. 9% 76. 5% 77. 5% 74. 5% 71. 2% Q 6 46. 2% 48. 6% 42. 3% 56. 0% 53. 7% 76. 2% 58. 4% 54. 7% joint Q 1 Q 6 14. 7% 14. 3% 12. 0% 26. 2% 24. 8% 32. 5% 26. 2% 21. 7%

Frank Cowell: Overall results UB Public Economics n n n Responses violate transfer (mps) principle Question pattern similar to previous studies Extremes produce orthodox responses Positive flavours exhibit higher proportion of orthodox responses Involvement?

Frank Cowell: Involvement UB Public Economics n n n Same issues for risk and for welfare? Is there a male/female effect? Yes if we are looking from Olympian detachment…

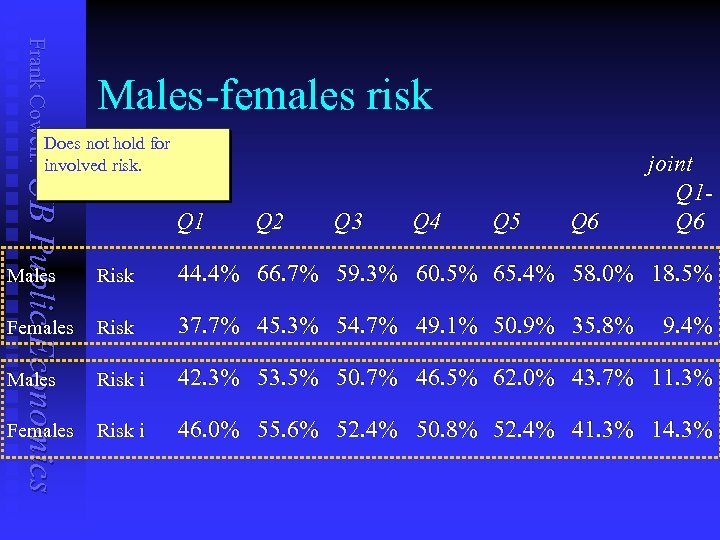

Frank Cowell: Males-females risk Does not hold for Non-involved risk. Males more orthodox UB Public Economics Q 1 Q 2 Q 3 Q 4 Q 5 Q 6 joint Q 1 Q 6 Males Risk 44. 4% 66. 7% 59. 3% 60. 5% 65. 4% 58. 0% 18. 5% Females Risk 37. 7% 45. 3% 54. 7% 49. 1% 50. 9% 35. 8% Males Risk i 42. 3% 53. 5% 50. 7% 46. 5% 62. 0% 43. 7% 11. 3% Females Risk i 46. 0% 55. 6% 52. 4% 50. 8% 52. 4% 41. 3% 14. 3% 9. 4%

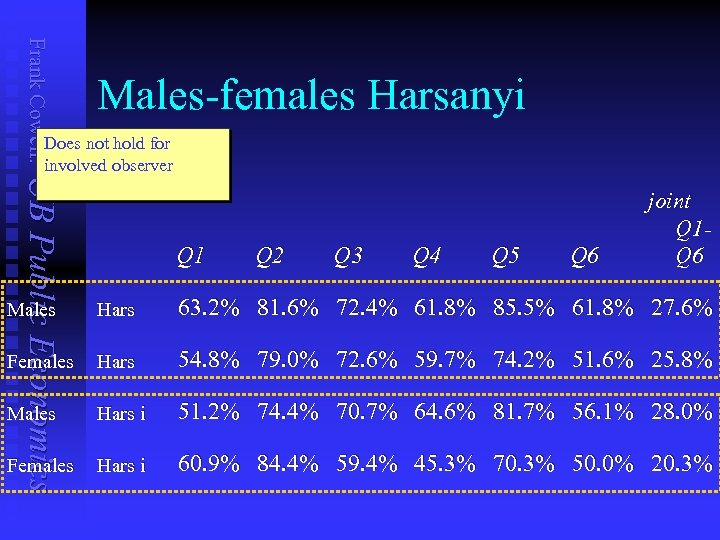

Frank Cowell: Males-females Harsanyi Does not hold for Outside observer. Males involved observer more orthodox? UB Public Economics Q 1 Q 2 Q 3 Q 4 Q 5 Q 6 joint Q 1 Q 6 Males Hars 63. 2% 81. 6% 72. 4% 61. 8% 85. 5% 61. 8% 27. 6% Females Hars 54. 8% 79. 0% 72. 6% 59. 7% 74. 2% 51. 6% 25. 8% Males Hars i 51. 2% 74. 4% 70. 7% 64. 6% 81. 7% 56. 1% 28. 0% Females Hars i 60. 9% 84. 4% 59. 4% 45. 3% 70. 3% 50. 0% 20. 3%

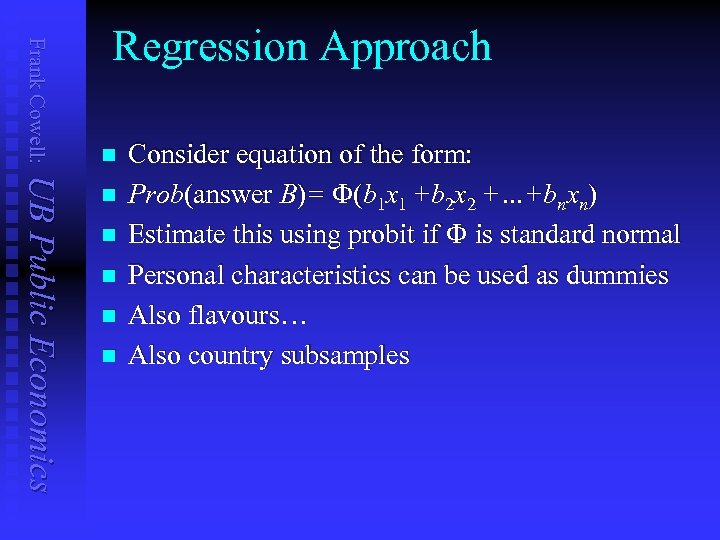

Frank Cowell: Regression Approach n UB Public Economics n n n Consider equation of the form: Prob(answer B)= F(b 1 x 1 +b 2 x 2 +…+bnxn) Estimate this using probit if F is standard normal Personal characteristics can be used as dummies Also flavours… Also country subsamples

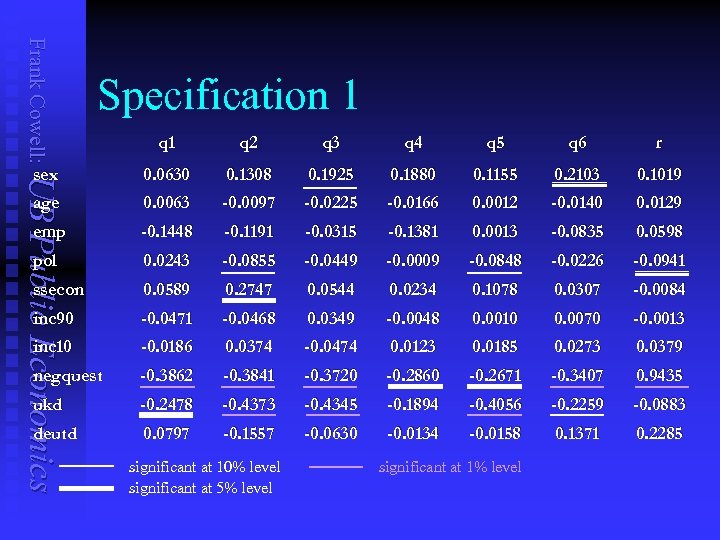

Frank Cowell: Specification 1 q 2 q 3 q 4 q 5 q 6 r sex 0. 0630 0. 1308 0. 1925 0. 1880 0. 1155 0. 2103 0. 1019 age 0. 0063 -0. 0097 -0. 0225 -0. 0166 0. 0012 -0. 0140 0. 0129 emp -0. 1448 -0. 1191 -0. 0315 -0. 1381 0. 0013 -0. 0835 0. 0598 pol 0. 0243 -0. 0855 -0. 0449 -0. 0009 -0. 0848 -0. 0226 -0. 0941 ssecon 0. 0589 0. 2747 0. 0544 0. 0234 0. 1078 0. 0307 -0. 0084 inc 90 -0. 0471 -0. 0468 0. 0349 -0. 0048 0. 0010 0. 0070 -0. 0013 inc 10 -0. 0186 0. 0374 -0. 0474 0. 0123 0. 0185 0. 0273 0. 0379 negquest -0. 3862 -0. 3841 -0. 3720 -0. 2860 -0. 2671 -0. 3407 0. 9435 ukd -0. 2478 -0. 4373 -0. 4345 -0. 1894 -0. 4056 -0. 2259 -0. 0883 deutd 0. 0797 -0. 1557 -0. 0630 -0. 0134 -0. 0158 0. 1371 0. 2285 UB Public Economics q 1 significant at 10% level significant at 5% level significant at 1% level

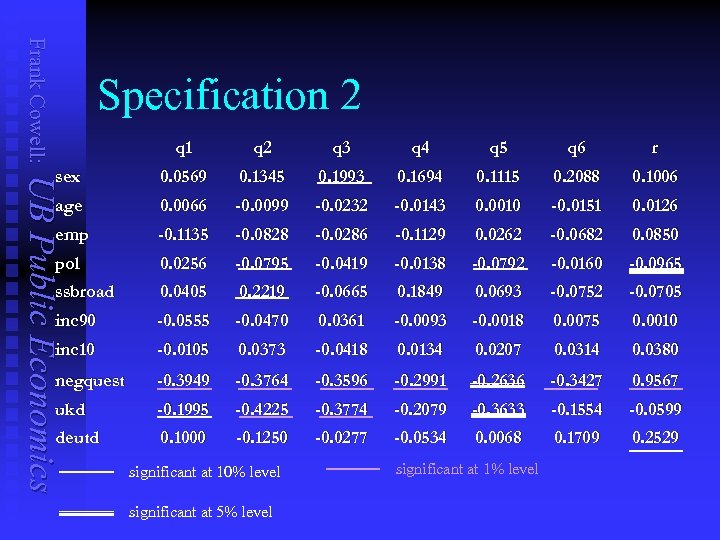

Frank Cowell: Specification 2 q 3 q 4 q 5 q 6 r sex 0. 0569 0. 1345 0. 1993 0. 1694 0. 1115 0. 2088 0. 1006 age 0. 0066 -0. 0099 -0. 0232 -0. 0143 0. 0010 -0. 0151 0. 0126 emp -0. 1135 -0. 0828 -0. 0286 -0. 1129 0. 0262 -0. 0682 0. 0850 pol 0. 0256 -0. 0795 -0. 0419 -0. 0138 -0. 0792 -0. 0160 -0. 0965 ssbroad 0. 0405 0. 2219 -0. 0665 0. 1849 0. 0693 -0. 0752 -0. 0705 inc 90 -0. 0555 -0. 0470 0. 0361 -0. 0093 -0. 0018 0. 0075 0. 0010 inc 10 -0. 0105 0. 0373 -0. 0418 0. 0134 0. 0207 0. 0314 0. 0380 negquest -0. 3949 -0. 3764 -0. 3596 -0. 2991 -0. 2636 -0. 3427 0. 9567 ukd -0. 1995 -0. 4225 -0. 3774 -0. 2079 -0. 3633 -0. 1554 -0. 0599 deutd 0. 1000 -0. 1250 -0. 0277 -0. 0534 0. 0068 0. 1709 0. 2529 UB Public Economics q 1 significant at 10% level significant at 5% level significant at 1% level

Frank Cowell: Regression results UB Public Economics n n For regressions on the whole set of flavours… Get different picture of personal characteristics: u Sex and economics not significant u Perhaps political views are significant But two things come through clearly u Importance of flavour (neg/pos) u Role of country dummies Look more closely at subsamples

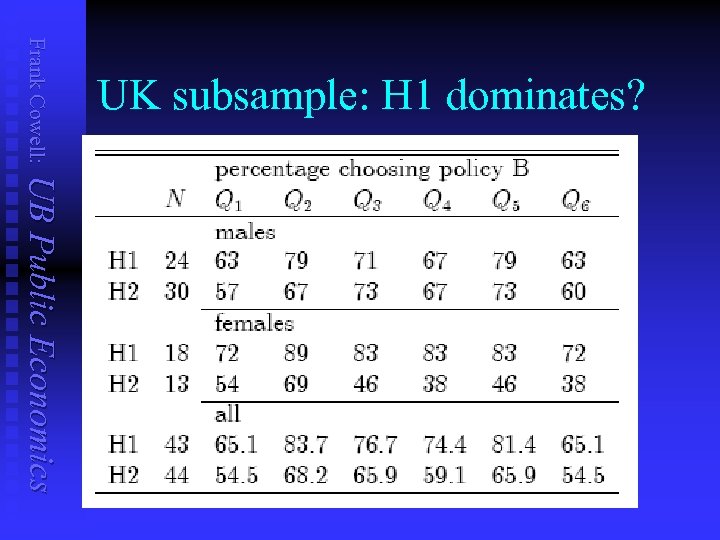

Frank Cowell: UK subsample: H 1 dominates? UB Public Economics

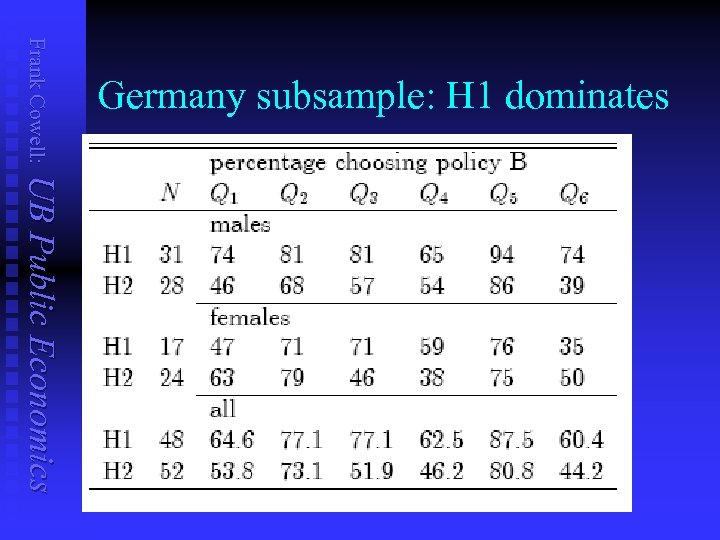

Frank Cowell: Germany subsample: H 1 dominates UB Public Economics

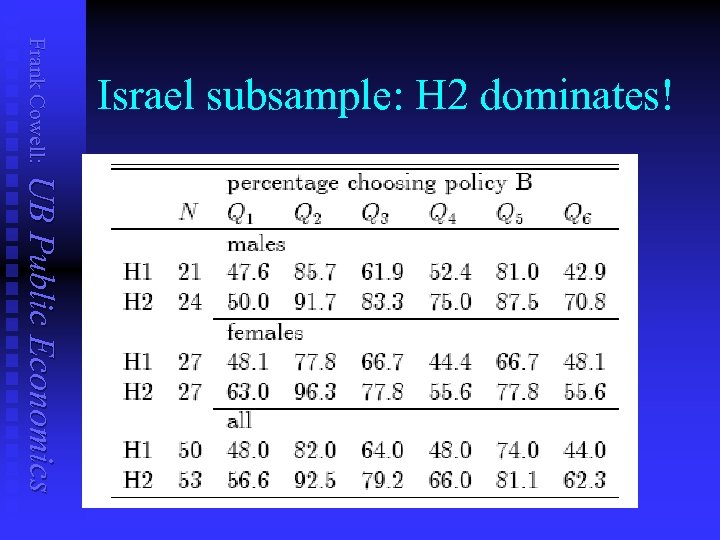

Frank Cowell: Israel subsample: H 2 dominates! UB Public Economics

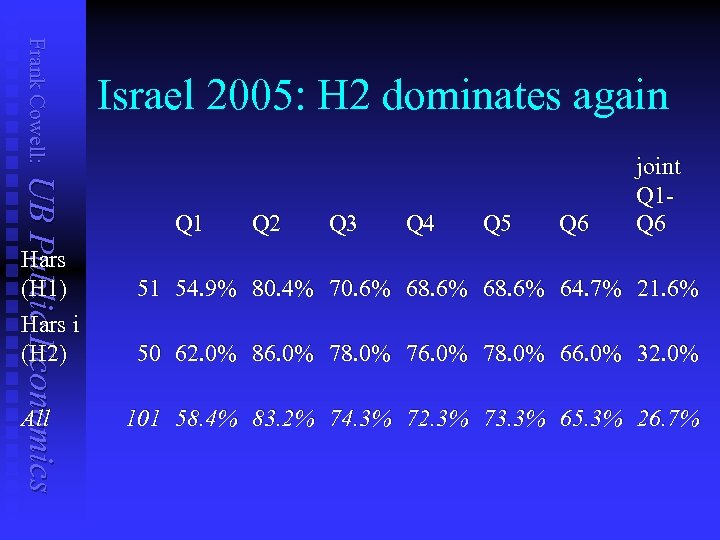

Frank Cowell: A second go UB Public Economics n n n Results from Israel were truly remarkable Were they a fluke from the specific sample? Try a second sample 18 months later Just focus on the Harsanyi flavours u 51 H 1 flavour (outside observer) u 50 H 2 flavour (involved observer) Again look at breakdown by questions

Frank Cowell: UB Public Economics Hars (H 1) Hars i (H 2) All Israel 2005: H 2 dominates again Q 1 Q 2 Q 3 Q 4 Q 5 Q 6 joint Q 1 Q 6 51 54. 9% 80. 4% 70. 6% 68. 6% 64. 7% 21. 6% 50 62. 0% 86. 0% 78. 0% 76. 0% 78. 0% 66. 0% 32. 0% 101 58. 4% 83. 2% 74. 3% 72. 3% 73. 3% 65. 3% 26. 7%

Frank Cowell: Conclusions UB Public Economics n n Move beyond simple question of transfer/mps principle Importance of cultural background? H 1 and H 2 not the same In some ways reflect response patterns on risk

Frank Cowell: Overview. . . Deprivation, complaints, inequality UB Public Economics Experimental approaches An economic interpretation of a sociological concept Deprivation Complaints Claims

Frank Cowell: A way forward UB Public Economics n n We will look at recent theoretical developments in distributional analysis Focus on alternative approaches to inequality Use ideas from sociology and philosophy Adopt the same axiomatic approach as was used for Poverty

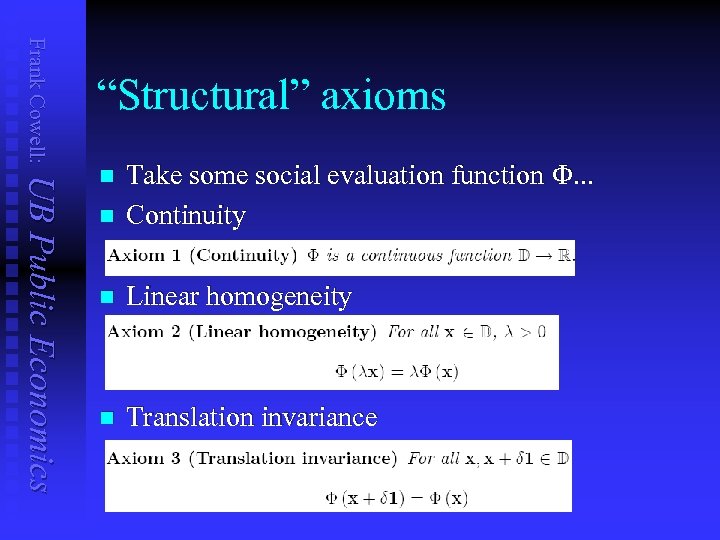

Frank Cowell: “Structural” axioms UB Public Economics n Take some social evaluation function F. . . Continuity n Linear homogeneity n Translation invariance n

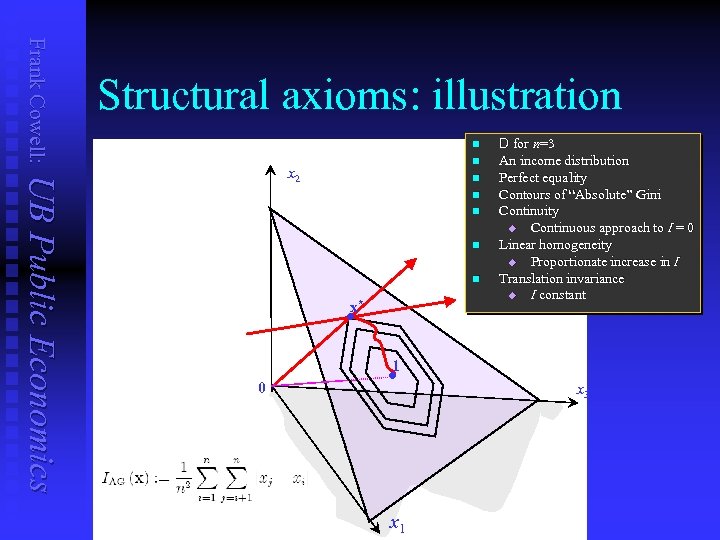

Frank Cowell: Structural axioms: illustration n n UB Public Economics x 2 n n n x* D for n=3 An income distribution Perfect equality Contours of “Absolute” Gini Continuity Continuous approach to I = 0 u Linear homogeneity u Proportionate increase in I Translation invariance u I constant • 1 0 • x 1 x 3

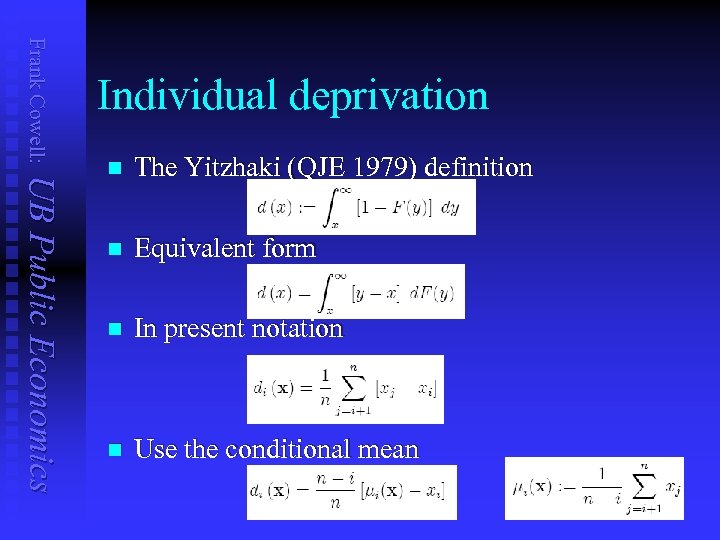

Frank Cowell: Individual deprivation UB Public Economics n The Yitzhaki (QJE 1979) definition n Equivalent form n In present notation n Use the conditional mean

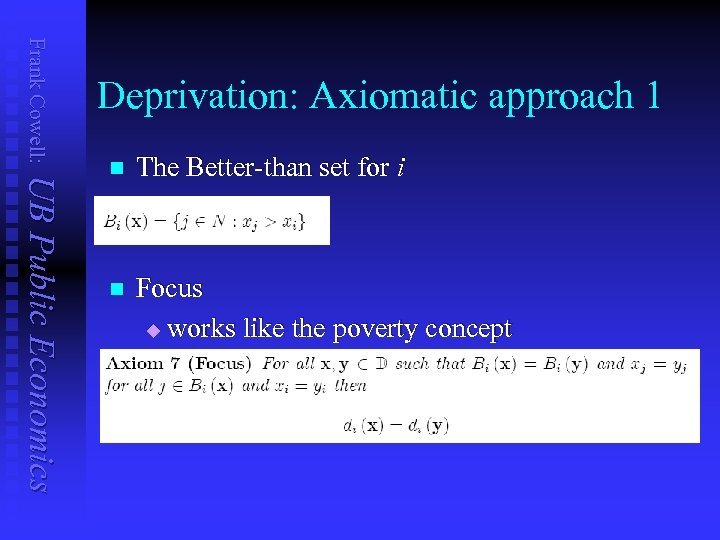

Frank Cowell: Deprivation: Axiomatic approach 1 UB Public Economics n The Better-than set for i n Focus u works like the poverty concept

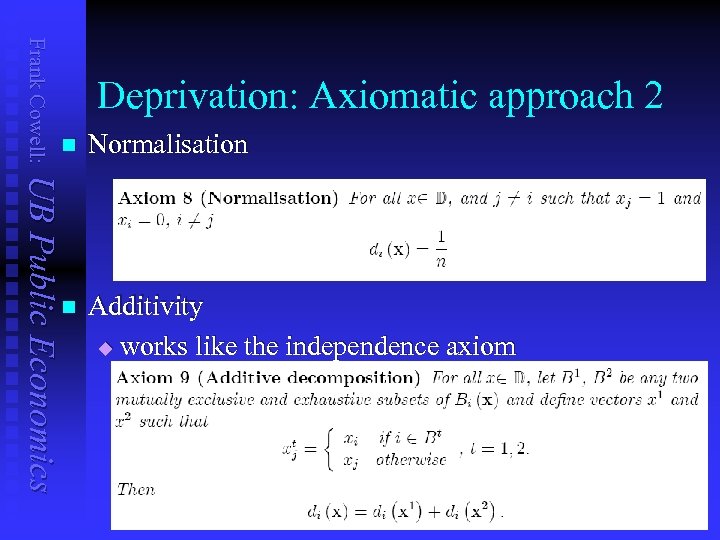

Frank Cowell: Deprivation: Axiomatic approach 2 n UB Public Economics n Normalisation Additivity u works like the independence axiom

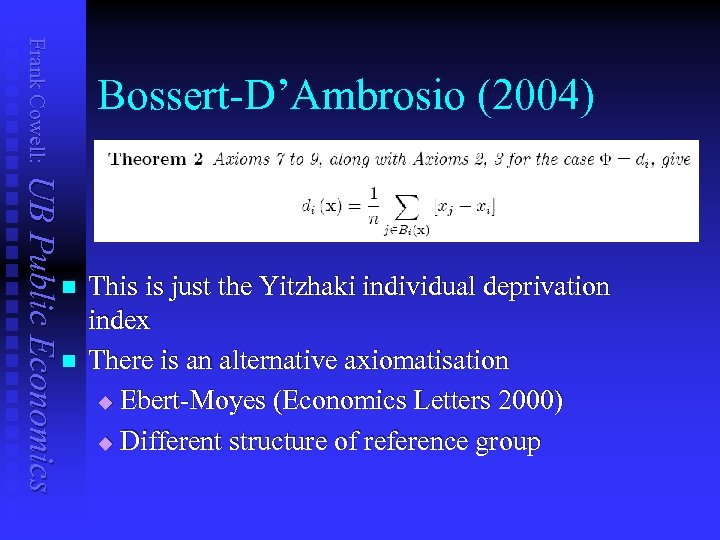

Frank Cowell: Bossert-D’Ambrosio (2004) UB Public Economics n n This is just the Yitzhaki individual deprivation index There is an alternative axiomatisation u Ebert-Moyes (Economics Letters 2000) u Different structure of reference group

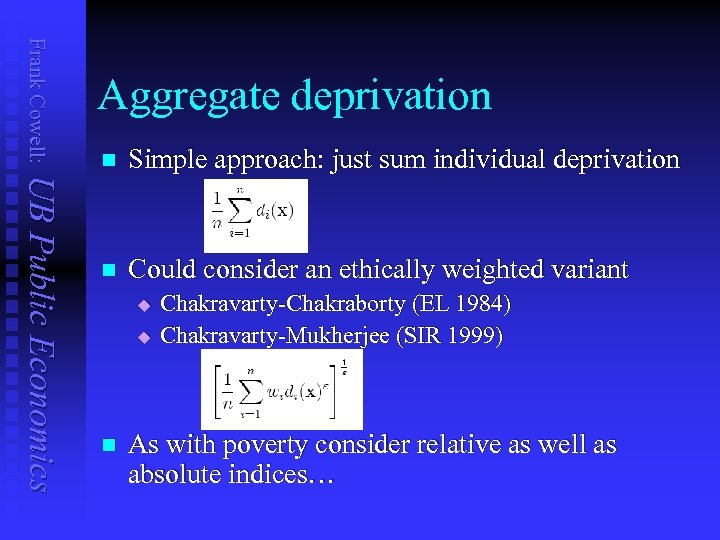

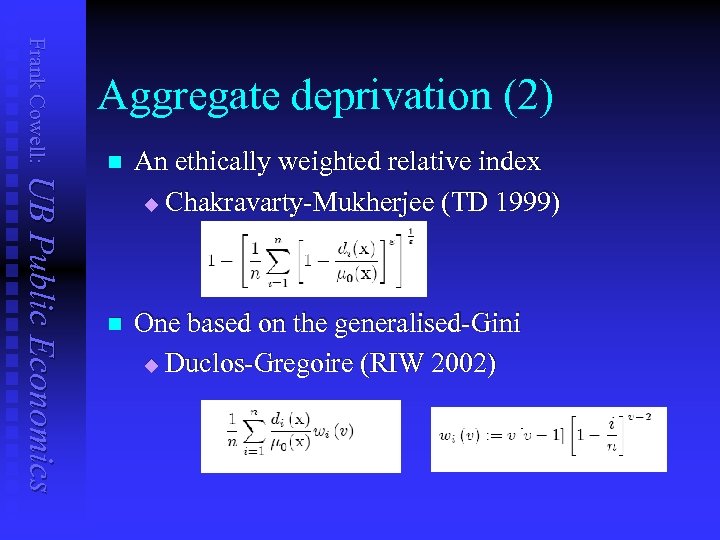

Frank Cowell: Aggregate deprivation UB Public Economics n Simple approach: just sum individual deprivation n Could consider an ethically weighted variant u u n Chakravarty-Chakraborty (EL 1984) Chakravarty-Mukherjee (SIR 1999) As with poverty consider relative as well as absolute indices…

Frank Cowell: Aggregate deprivation (2) UB Public Economics n An ethically weighted relative index u Chakravarty-Mukherjee (TD 1999) n One based on the generalised-Gini u Duclos-Gregoire (RIW 2002)

Frank Cowell: Overview. . . Deprivation, complaints, inequality UB Public Economics Experimental approaches Reference groups and distributional judgments Deprivation Complaints Claims • Model • Inequality results • Rankings and welfare

Frank Cowell: The Temkin approach UB Public Economics n n n Larry Temkin (1986, 1993) approach to inequality u Unconventional u Not based on utilitarian welfare economics u But not a complete “outlier” Common ground with other distributional analysis u Poverty u deprivation Contains the following elements: u Concept of a complaint u The idea of a reference group u A method of aggregation

Frank Cowell: What is a “complaint? ” UB Public Economics n n Individual’s relationship with the income distribution The complaint exists independently u u n does not depend on how people feel does not invoke “utility” or (dis)satisfaction Requires a reference group u u effectively a reference income a variety of specifications

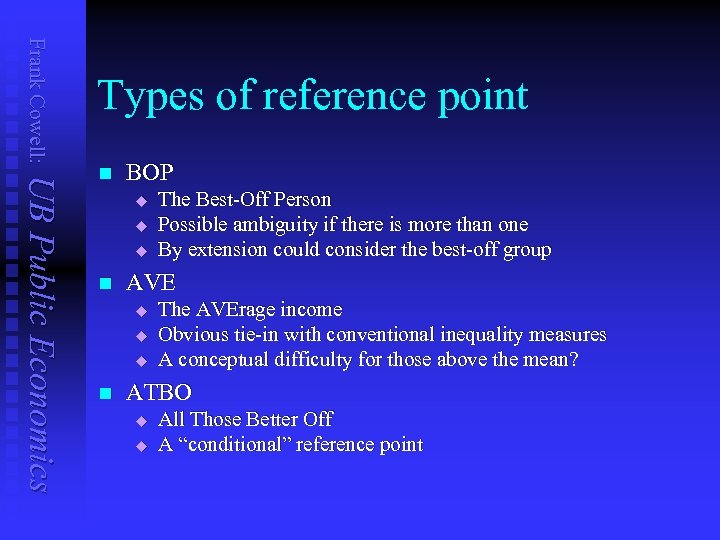

Frank Cowell: Types of reference point UB Public Economics n BOP u u u n AVE u u u n The Best-Off Person Possible ambiguity if there is more than one By extension could consider the best-off group The AVErage income Obvious tie-in with conventional inequality measures A conceptual difficulty for those above the mean? ATBO u u All Those Better Off A “conditional” reference point

Frank Cowell: Aggregation UB Public Economics n n n The complaint is an individual phenomenon. How to make the transition from this to society as a whole? Temkin makes two suggestions: Simple sum u Just add up the complaints Weighted sum u Introduce distributional weights u Then sum the weighted complaints

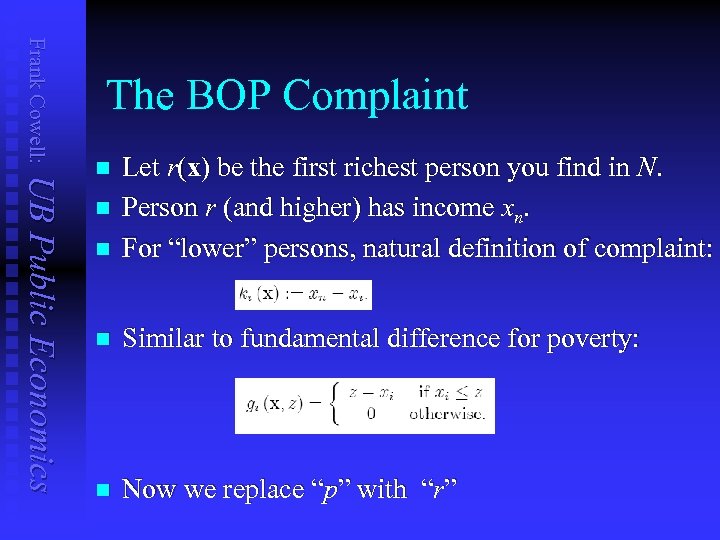

Frank Cowell: The BOP Complaint UB Public Economics n Let r(x) be the first richest person you find in N. Person r (and higher) has income xn. For “lower” persons, natural definition of complaint: n Similar to fundamental difference for poverty: n Now we replace “p” with “r” n n

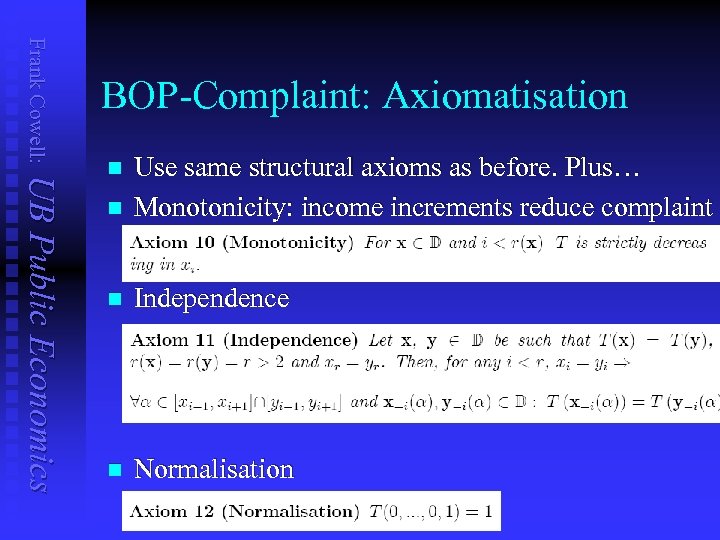

Frank Cowell: BOP-Complaint: Axiomatisation UB Public Economics n Use same structural axioms as before. Plus… Monotonicity: income increments reduce complaint n Independence n Normalisation n

Frank Cowell: Overview. . . Deprivation, complaints, inequality UB Public Economics Experimental approaches A new approach to inequality Deprivation Complaints Claims • Model • Inequality results • Rankings and welfare

Frank Cowell: Implications for inequality UB Public Economics n n Broadly two types of axioms with different roles. Axioms on structure: v n use these to determine the “shape” of the measures. Transfer principles and properties of measures: v use these to characterise ethical nature of measures

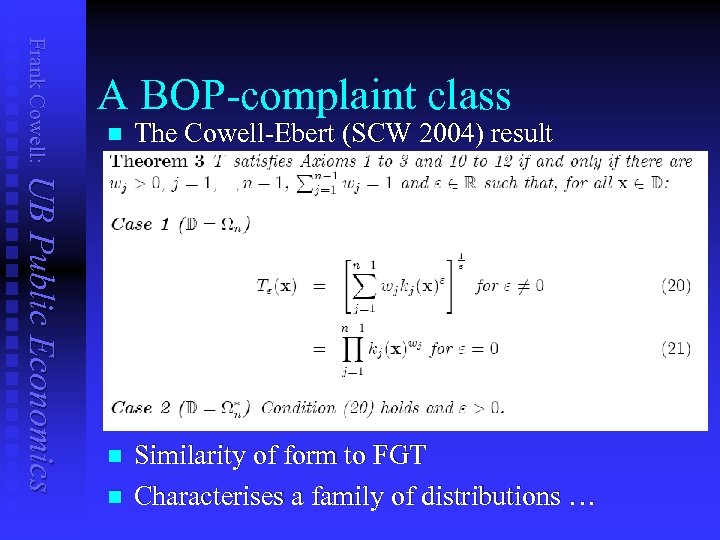

Frank Cowell: A BOP-complaint class UB Public Economics n The Cowell-Ebert (SCW 2004) result n Similarity of form to FGT Characterises a family of distributions … n

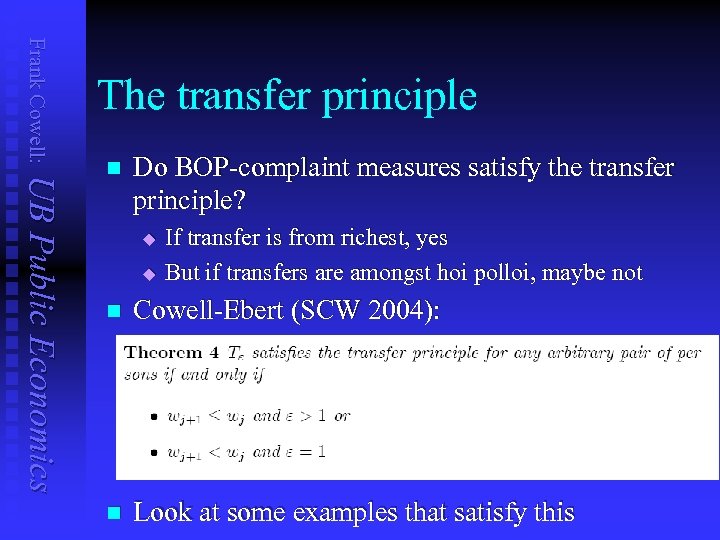

Frank Cowell: The transfer principle UB Public Economics n Do BOP-complaint measures satisfy the transfer principle? u u If transfer is from richest, yes But if transfers are amongst hoi polloi, maybe not n Cowell-Ebert (SCW 2004): n Look at some examples that satisfy this

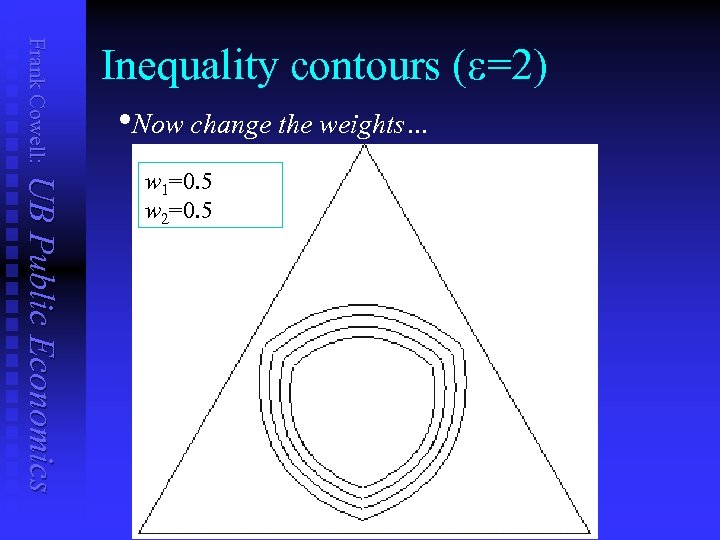

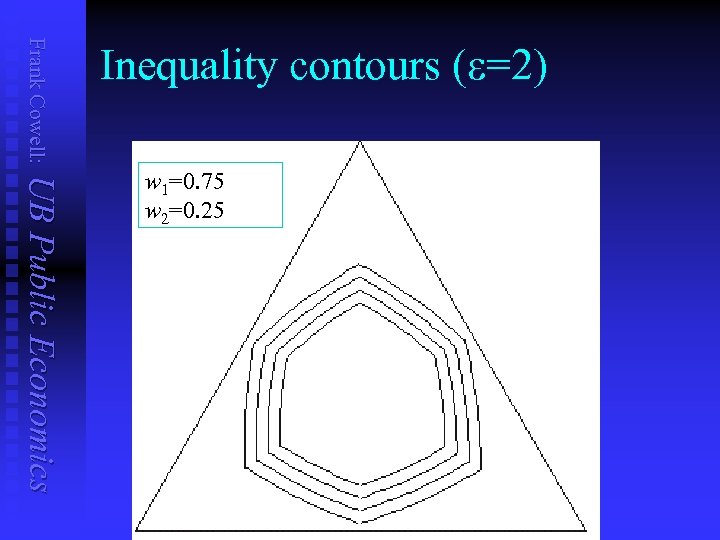

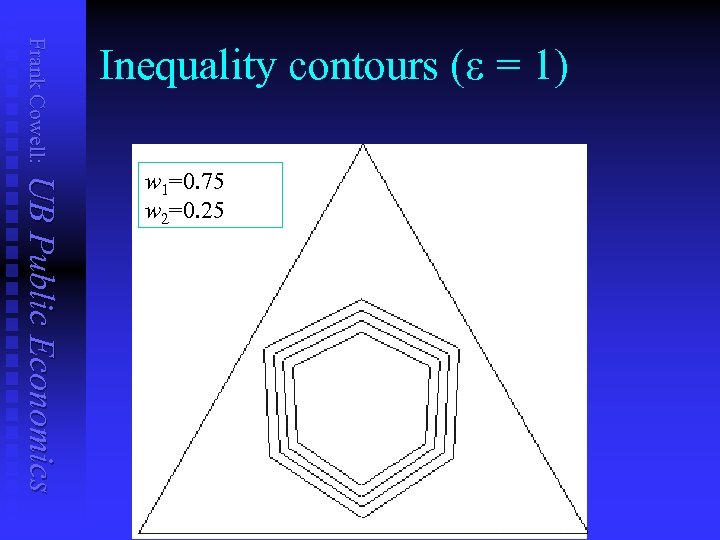

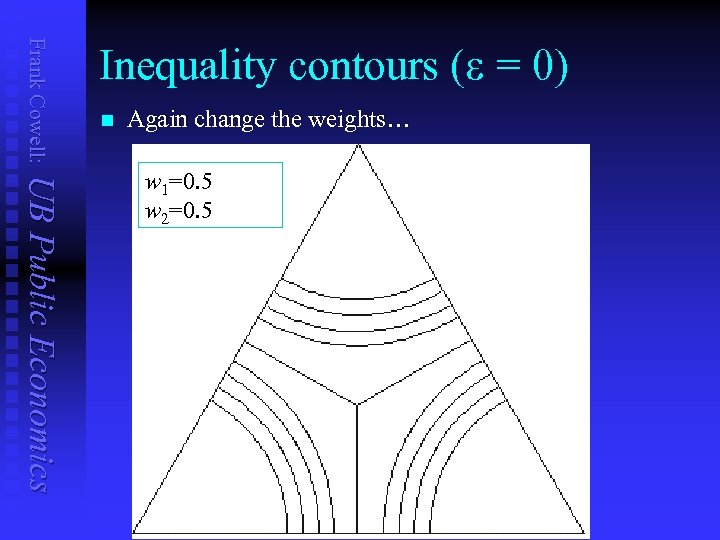

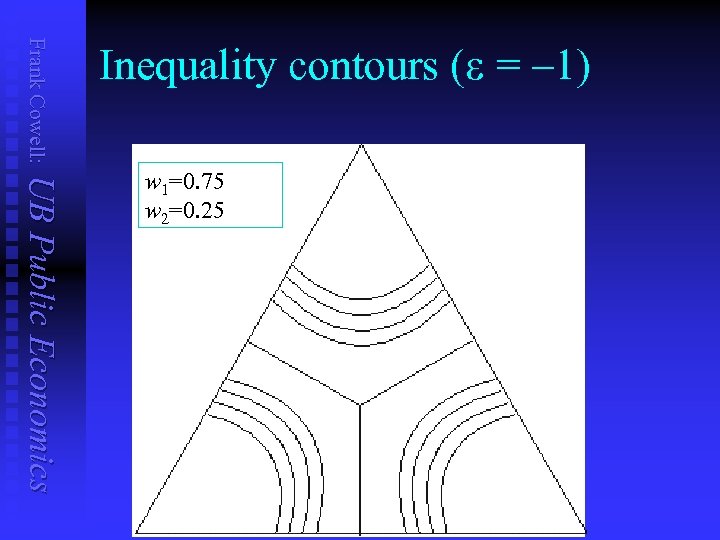

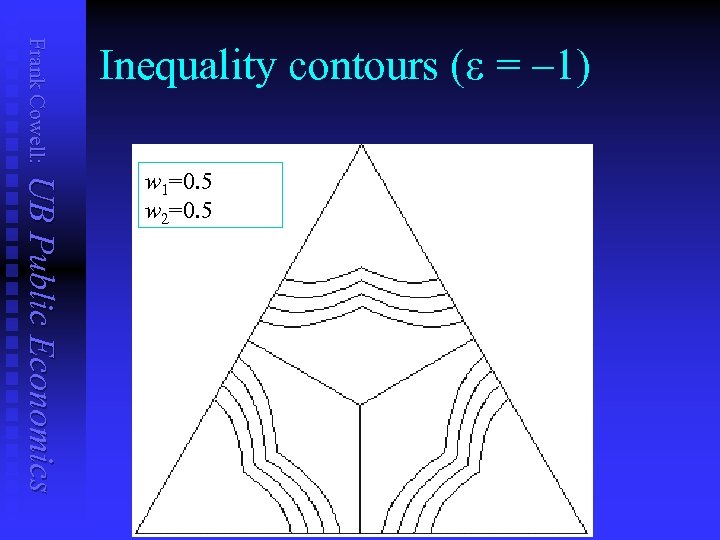

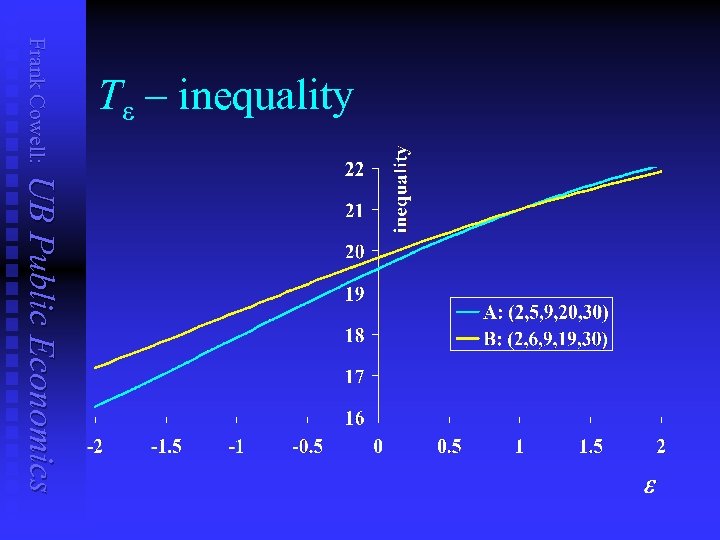

Frank Cowell: Inequality contours UB Public Economics n n To examine the properties of the derived indices… …take the case n = 3 Draw contours of T –inequality Note that both the sensitivity parameter and the weights w are of interest…

Frank Cowell: Inequality contours ( =2) • Now change the weights… UB Public Economics w 1=0. 5 w 2=0. 5

Frank Cowell: Inequality contours ( =2) UB Public Economics w 1=0. 75 w 2=0. 25

Frank Cowell: Inequality contours ( = 1) UB Public Economics w 1=0. 75 w 2=0. 25

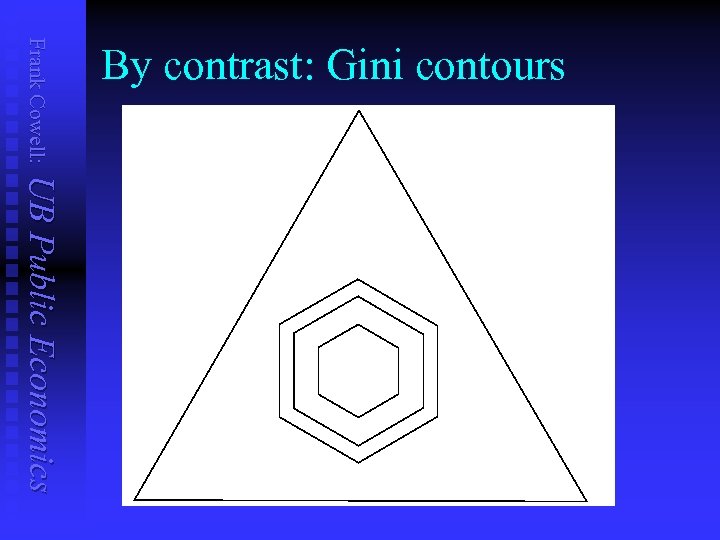

Frank Cowell: By contrast: Gini contours UB Public Economics

Frank Cowell: Inequality contours ( = 0) n Again change the weights… UB Public Economics w 1=0. 5 w 2=0. 5

Frank Cowell: Inequality contours ( = – 1) UB Public Economics w 1=0. 75 w 2=0. 25

Frank Cowell: Inequality contours ( = – 1) UB Public Economics w 1=0. 5 w 2=0. 5

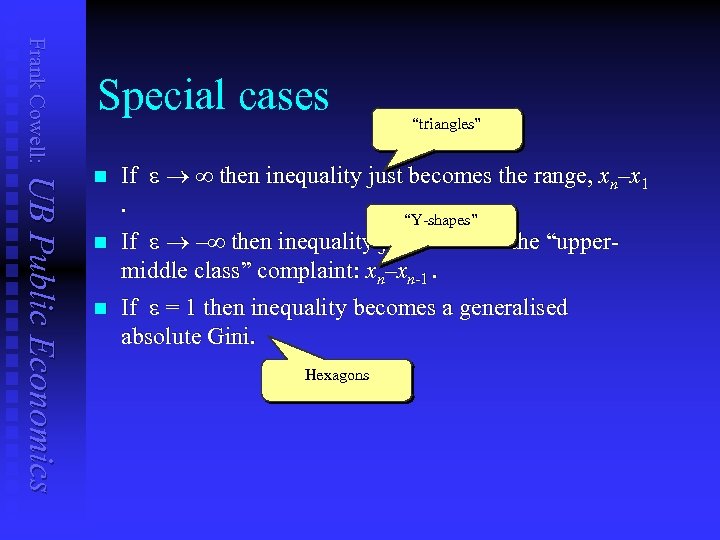

Frank Cowell: Special cases UB Public Economics n “triangles” If then inequality just becomes the range, xn–x 1. “Y-shapes” n If – then inequality just becomes the “uppermiddle class” complaint: xn–xn-1. n If = 1 then inequality becomes a generalised absolute Gini. Hexagons

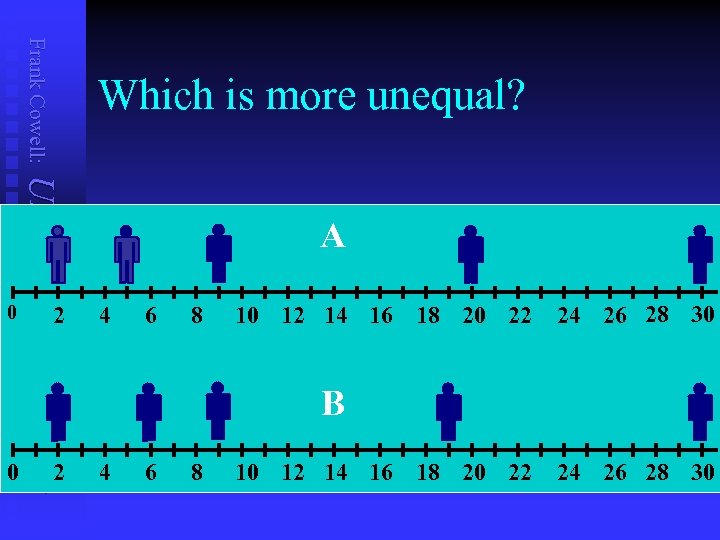

Frank Cowell: 0 UB Public Economics 0 Which is more unequal? 2 2 A 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 B 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30

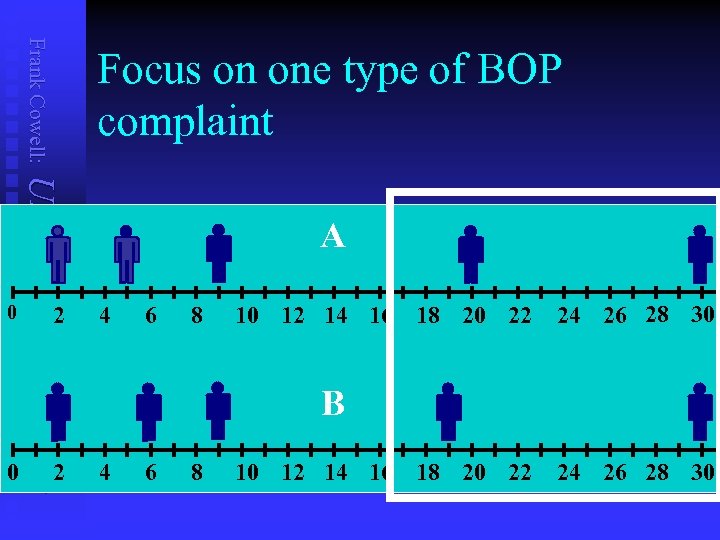

Frank Cowell: 0 UB Public Economics 0 Focus on one type of BOP complaint 2 2 A 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 B 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30

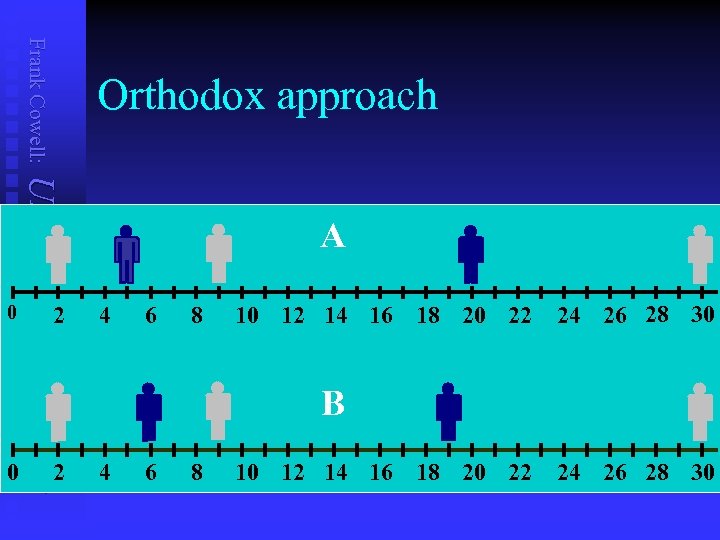

Frank Cowell: 0 UB Public Economics 0 Orthodox approach 2 2 A 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 B 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30

Frank Cowell: T – inequality UB Public Economics

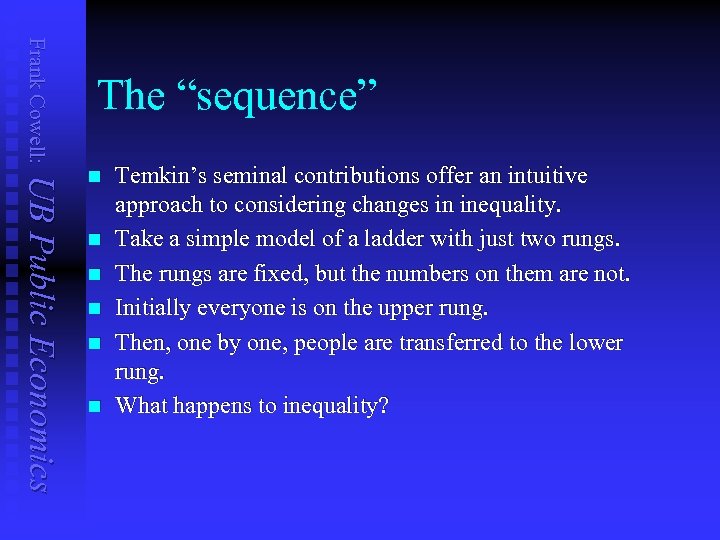

Frank Cowell: The “sequence” UB Public Economics n n n Temkin’s seminal contributions offer an intuitive approach to considering changes in inequality. Take a simple model of a ladder with just two rungs. The rungs are fixed, but the numbers on them are not. Initially everyone is on the upper rung. Then, one by one, people are transferred to the lower rung. What happens to inequality?

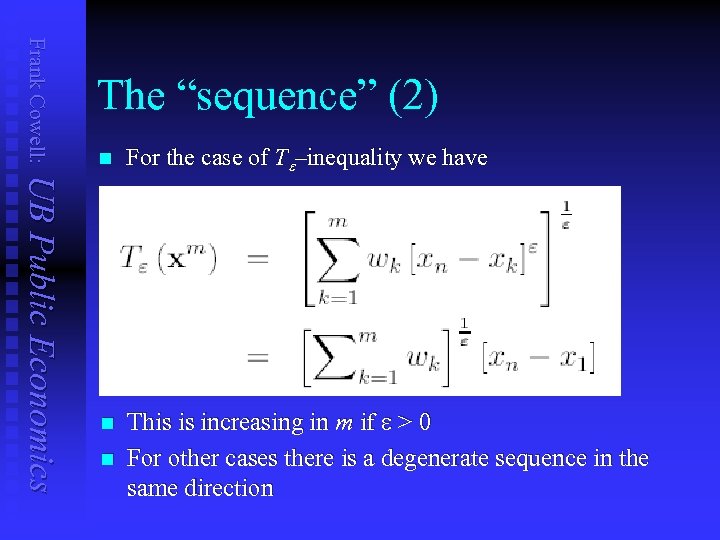

Frank Cowell: The “sequence” (2) UB Public Economics n For the case of T –inequality we have n This is increasing in m if > 0 For other cases there is a degenerate sequence in the same direction n

Frank Cowell: Overview. . . Deprivation, complaints, inequality UB Public Economics Experimental approaches A replacement for the Lorenz order? Deprivation Complaints Claims • Model • Inequality results • Rankings and welfare

Frank Cowell: Rankings UB Public Economics n n Move beyond simple inequality measures The notion of complaint can also be used to generate a ranking principle that can be applied quite generally. This is rather like the use of Lorenz curves to specify a Lorenz ordering that characterises inequality comparisons. Also similar to poverty rankings with arbitrary poverty lines.

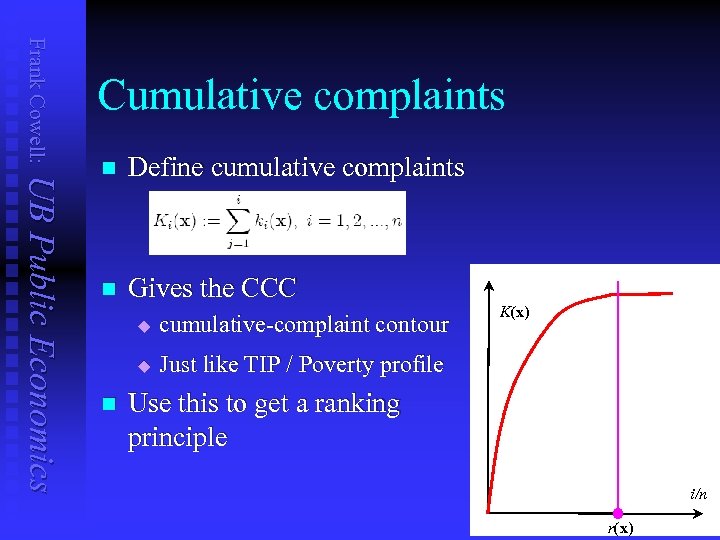

Frank Cowell: Cumulative complaints UB Public Economics n Define cumulative complaints n Gives the CCC u u n cumulative-complaint contour K(x) Just like TIP / Poverty profile Use this to get a ranking principle i/n r(x)

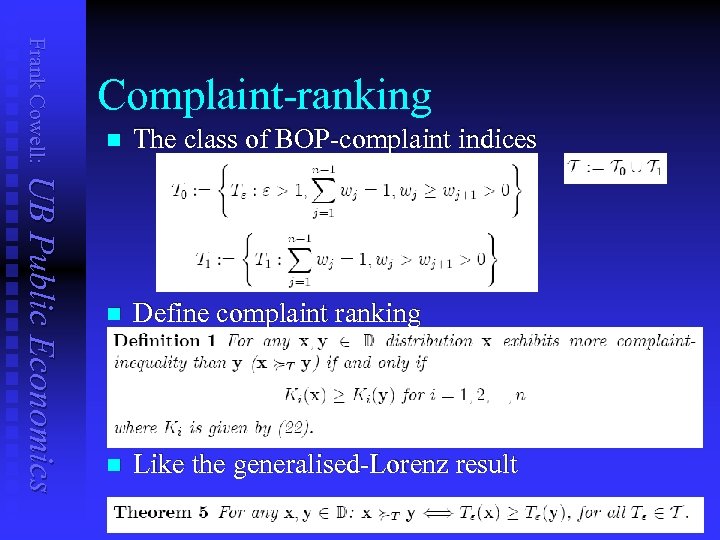

Frank Cowell: Complaint-ranking UB Public Economics n The class of BOP-complaint indices n Define complaint ranking n Like the generalised-Lorenz result

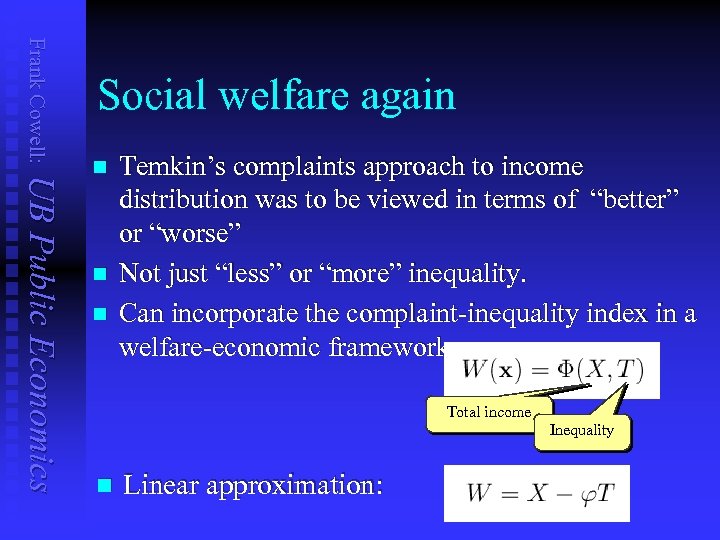

Frank Cowell: Social welfare again UB Public Economics n n n Temkin’s complaints approach to income distribution was to be viewed in terms of “better” or “worse” Not just “less” or “more” inequality. Can incorporate the complaint-inequality index in a welfare-economic framework: Total income Inequality n Linear approximation:

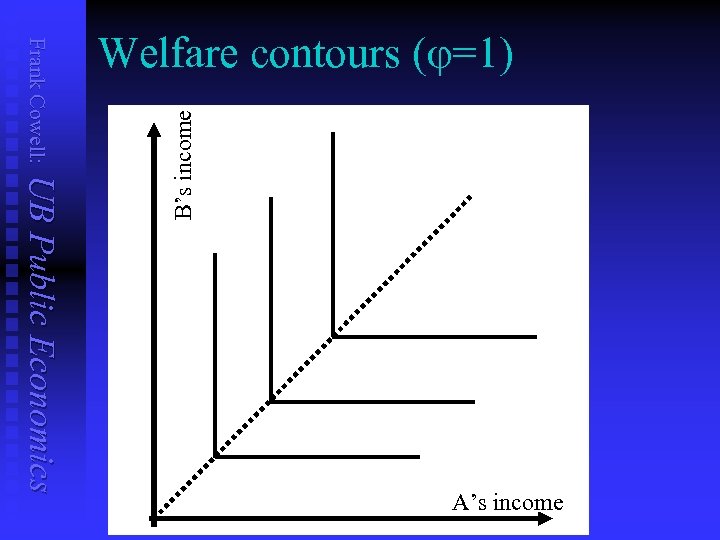

A’s income UB Public Economics B’s income Frank Cowell: Welfare contours (φ=1)

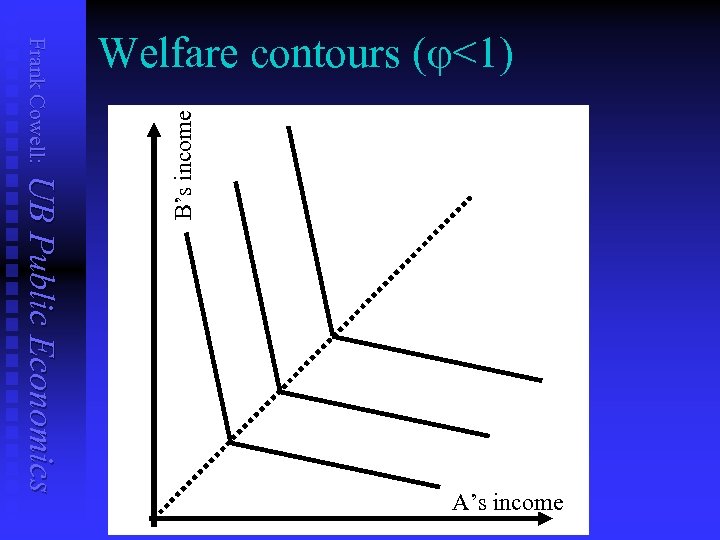

A’s income UB Public Economics B’s income Frank Cowell: Welfare contours (φ<1)

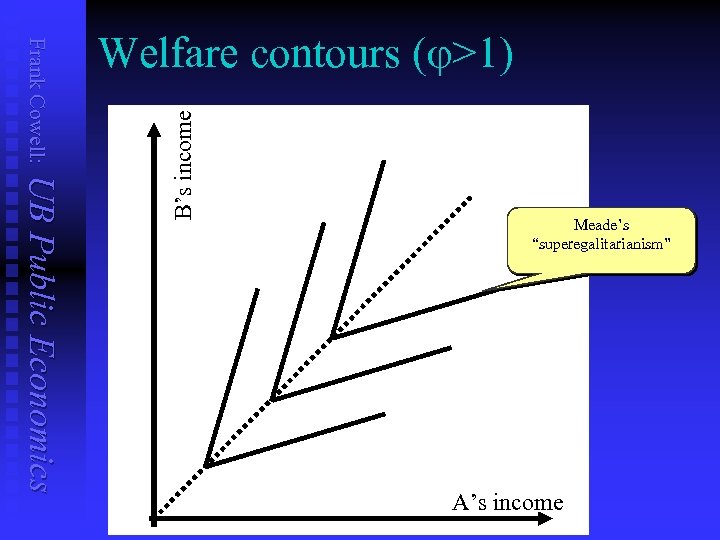

Meade’s “superegalitarianism” A’s income UB Public Economics B’s income Frank Cowell: Welfare contours (φ>1)

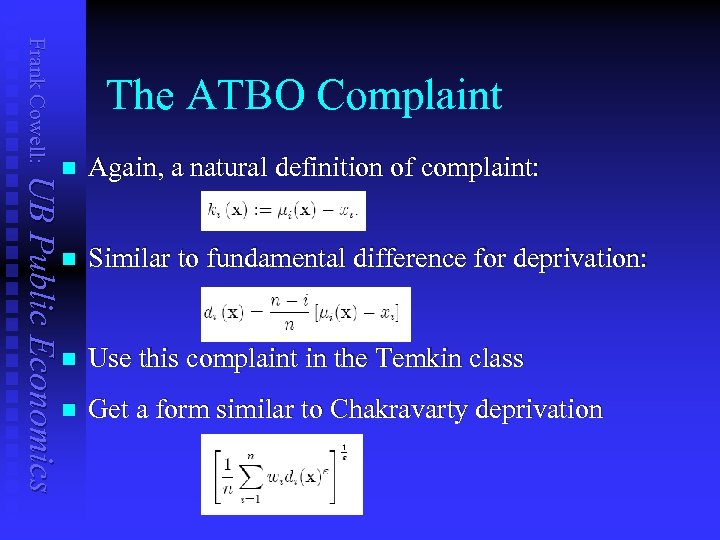

Frank Cowell: The ATBO Complaint Again, a natural definition of complaint: n Similar to fundamental difference for deprivation: n Use this complaint in the Temkin class n Get a form similar to Chakravarty deprivation UB Public Economics n

Frank Cowell: Summary: complaints n UB Public Economics n n n “Complaints” provide a useful basis for inequality analysis. Intuitive links with poverty and deprivation as well as conventional inequality. BOP extension provides an implementable inequality measure. CCCs provide an implementable ranking principle

Frank Cowell: Overview. . . Deprivation, complaints, inequality UB Public Economics Experimental approaches New insight on old rules Deprivation Complaints Claims

Frank Cowell: The approach UB Public Economics n n Settling “claims” by concerned parties Long historical precedent u u n Applies to a variety of civil disputes u n n Discussed in the Talmud The disputed garment story All have a similar structure Recently extended to Public Economics “Claims” as the basis for social justice

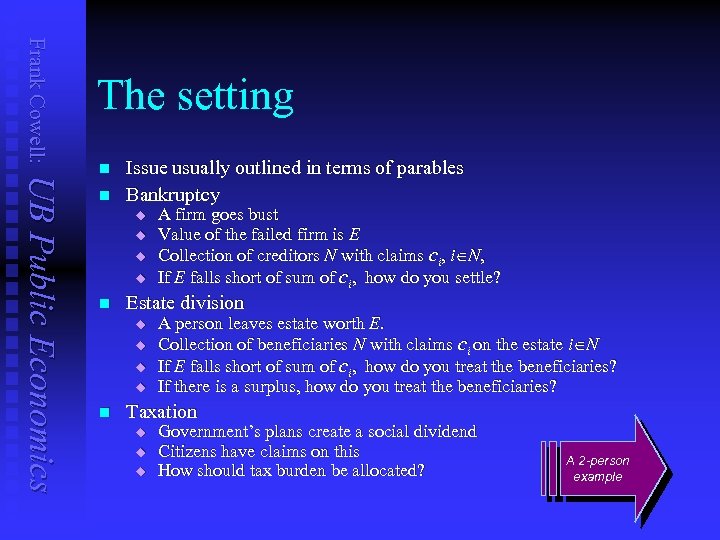

Frank Cowell: The setting UB Public Economics n n Issue usually outlined in terms of parables Bankruptcy u u n Estate division u u n A firm goes bust Value of the failed firm is E Collection of creditors N with claims ci, i N, If E falls short of sum of ci, how do you settle? A person leaves estate worth E. Collection of beneficiaries N with claims ci on the estate i N If E falls short of sum of ci, how do you treat the beneficiaries? If there is a surplus, how do you treat the beneficiaries? Taxation u u u Government’s plans create a social dividend Citizens have claims on this How should tax burden be allocated? A 2 -person example

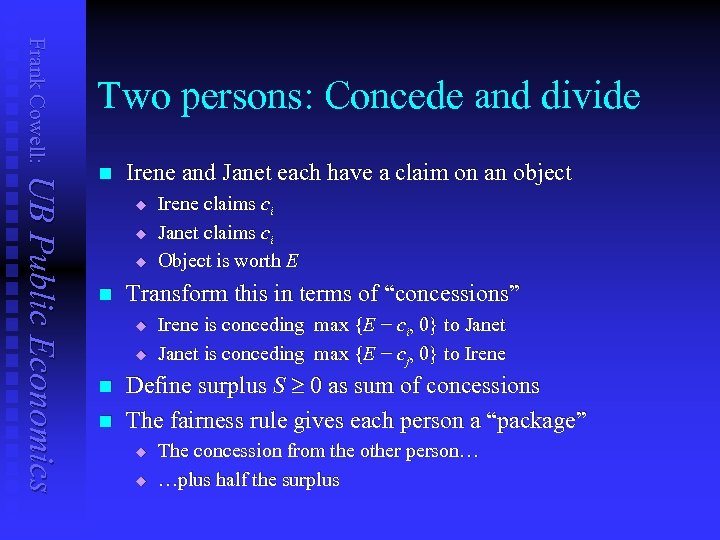

Frank Cowell: Two persons: Concede and divide UB Public Economics n Irene and Janet each have a claim on an object u u u n Transform this in terms of “concessions” u u n n Irene claims ci Janet claims ci Object is worth E Irene is conceding max {E − ci, 0} to Janet is conceding max {E − cj, 0} to Irene Define surplus S 0 as sum of concessions The fairness rule gives each person a “package” u u The concession from the other person… …plus half the surplus

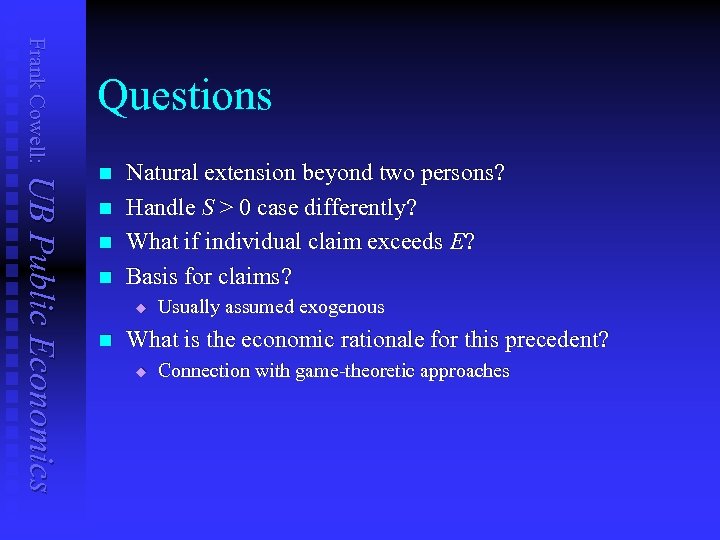

Frank Cowell: Questions UB Public Economics n n Natural extension beyond two persons? Handle S > 0 case differently? What if individual claim exceeds E? Basis for claims? u n Usually assumed exogenous What is the economic rationale for this precedent? u Connection with game-theoretic approaches

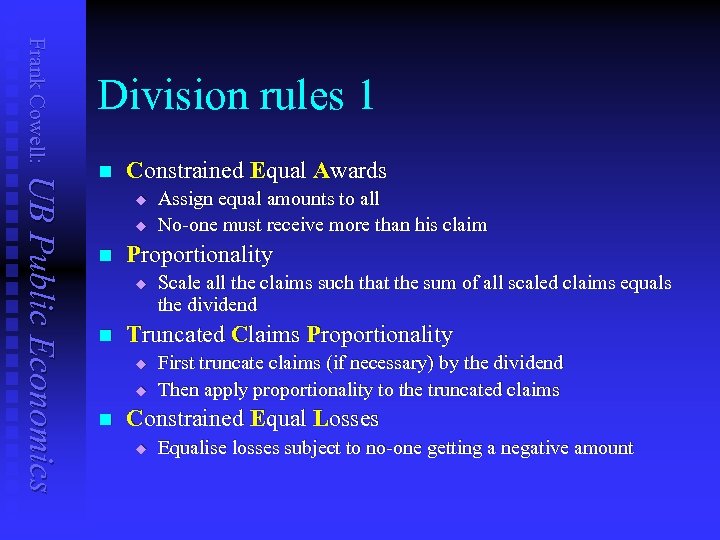

Frank Cowell: Division rules 1 UB Public Economics n Constrained Equal Awards u u n Proportionality u n Scale all the claims such that the sum of all scaled claims equals the dividend Truncated Claims Proportionality u u n Assign equal amounts to all No-one must receive more than his claim First truncate claims (if necessary) by the dividend Then apply proportionality to the truncated claims Constrained Equal Losses u Equalise losses subject to no-one getting a negative amount

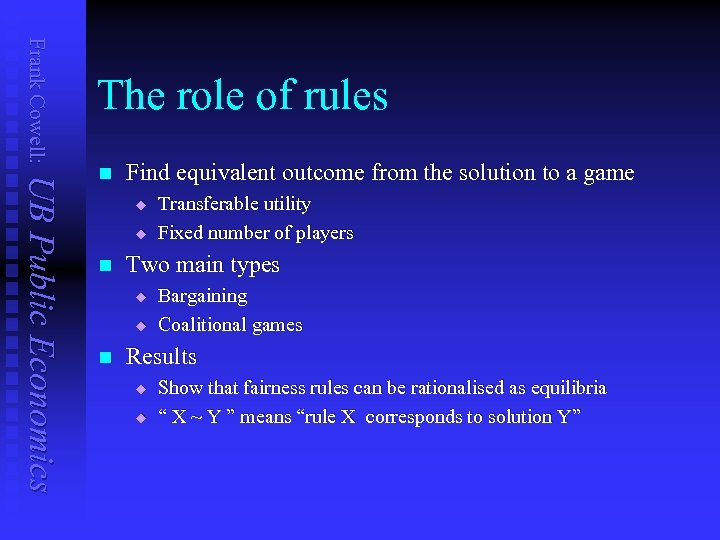

Frank Cowell: The role of rules UB Public Economics n Find equivalent outcome from the solution to a game u u n Two main types u u n Transferable utility Fixed number of players Bargaining Coalitional games Results u u Show that fairness rules can be rationalised as equilibria “ X ~ Y ” means “rule X corresponds to solution Y”

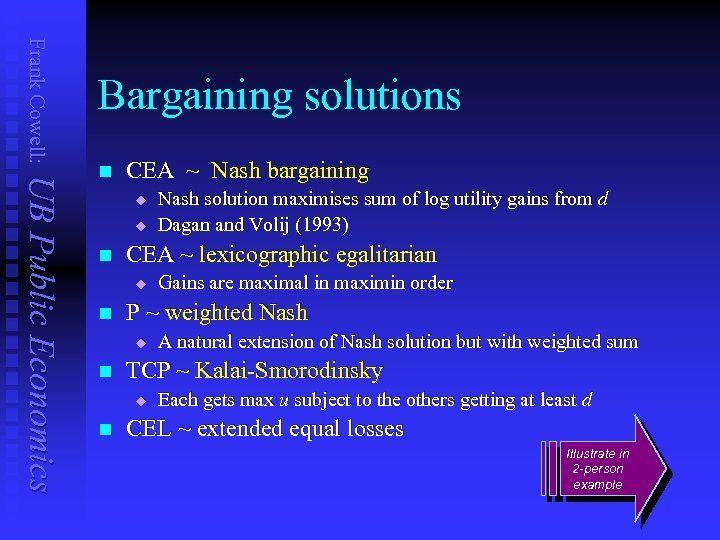

Frank Cowell: Bargaining solutions UB Public Economics n CEA ~ Nash bargaining u u n CEA ~ lexicographic egalitarian u n A natural extension of Nash solution but with weighted sum TCP ~ Kalai-Smorodinsky u n Gains are maximal in maximin order P ~ weighted Nash u n Nash solution maximises sum of log utility gains from d Dagan and Volij (1993) Each gets max u subject to the others getting at least d CEL ~ extended equal losses Illustrate in 2 -person example

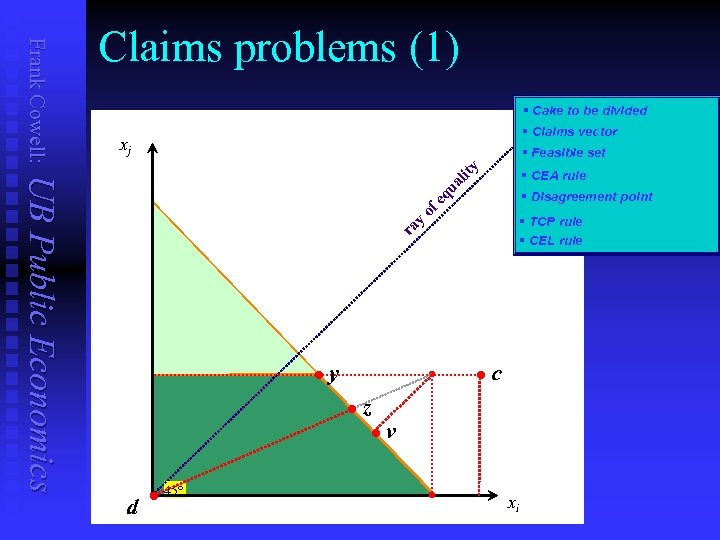

§ Cake to be divided § Claims vector xj § Feasible set y Frank Cowell: Claims problems (1) lit ua of eq § Disagreement point y § TCP rule § CEL rule ra UB Public Economics § CEA rule l y l l z l d 0 l 45° c v xi

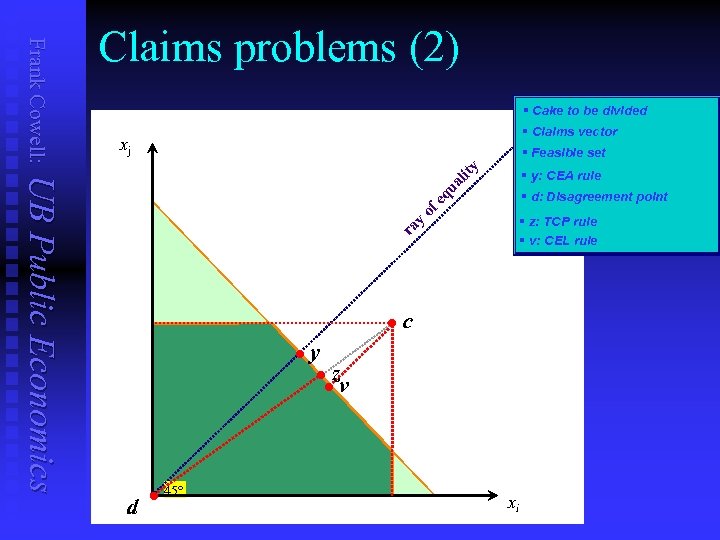

§ Cake to be divided § Claims vector xj § Feasible set y Frank Cowell: Claims problems (2) lit ua § d: Disagreement point eq of y ra UB Public Economics § y: CEA rule l l y § z: TCP rule § v: CEL rule c z v l l d 0 l 45° xi

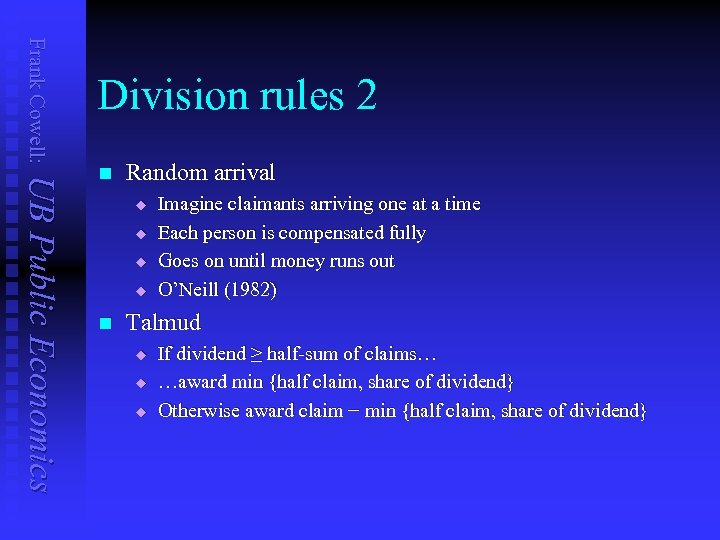

Frank Cowell: Division rules 2 UB Public Economics n Random arrival u u n Imagine claimants arriving one at a time Each person is compensated fully Goes on until money runs out O’Neill (1982) Talmud u u u If dividend ≥ half-sum of claims… …award min {half claim, share of dividend} Otherwise award claim − min {half claim, share of dividend}

Frank Cowell: Coalitional games UB Public Economics n Random arrival ~ Shapley value u u n Talmud ~ prenucleolus u u n Dissatisfaction : = difference between worth and sun of payouts Then minimise dissatisfaction for most dissatisfied Then for next most. . . Aumann and Maschler (1985) CEA ~ Dutta-Ray solution u u n Expected amount that arrival of new member changes worth of coalition O’Neill (1982) Core-vector that is Lorenz-maximal Dutta and Ray (1989) Adjusted proportional ~ t-value u u u Calculate maximum and minimum for each player Choose efficient vector that lies on line joining (max, min) Curiel et al (1987)

Frank Cowell: Empirical investigation (1) UB Public Economics n n Ponti et al (2002) Focus on three rules u u u n CEA Proportional CEL Subjects play four games u u For games k = 1, 2, 3. . . equilibrium outcome of game k coincides with rule k. Coordination game 4. . . strategy profiles where agree on the same rule are a NE.

Frank Cowell: Empirical investigation (2) UB Public Economics n n n Ponti et al (2002) results Games 1. . . 3: u Play converges to the unique equilibrium rule u Confirms that claims rules are rational? Game 4: u proportional rule prevails as a coordination device.

9f80322cf4e96ad7944f27e859a6bb32.ppt