f08440e0a4aff44ac969c61985d25fef.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 35

Forensic Evidence Case Law Developments Canines in Court From Civil Forfeiture to Criminal Human Scent Identification Cases Dr. Ken Furton Ken. Furton@fiu. edu 1

Forensic Evidence Case Law Developments Canines in Court From Civil Forfeiture to Criminal Human Scent Identification Cases Dr. Ken Furton Ken. Furton@fiu. edu 1

Several issues are regularly debated in the courts related to the deployment of canines in different situations: 1. Does a dog sniff outside of residential home constitute a search under the Fourth Amendment? 2. Does a dog to sniff at a routine traffic stop violated privacy clauses and how long can the motorist be detained while waiting for a canine unit to arrive? 3. If a narcotics detection canine alerts to a large sum of currency can that currency be confiscated as “drug money”? 4. If a human scent identification canine matches a suspect to a crime scent object can that evidence be presented in court and what weight should be given? 5. Should the results of a dog sniff be excluded because the technique is not sufficiently reliable. 2

Several issues are regularly debated in the courts related to the deployment of canines in different situations: 1. Does a dog sniff outside of residential home constitute a search under the Fourth Amendment? 2. Does a dog to sniff at a routine traffic stop violated privacy clauses and how long can the motorist be detained while waiting for a canine unit to arrive? 3. If a narcotics detection canine alerts to a large sum of currency can that currency be confiscated as “drug money”? 4. If a human scent identification canine matches a suspect to a crime scent object can that evidence be presented in court and what weight should be given? 5. Should the results of a dog sniff be excluded because the technique is not sufficiently reliable. 2

Does a dog sniff outside of residential home constitute a search under the Fourth Amendment? State v. Rabb; 920 So. 2 d 1175 (Fla. App. Dist. 2006) • Using the holding and analysis of the United States Supreme Court in Kyllo v. United States, the court held that the use of drug sniffing dogs to detect substances located within the house amounted to an illegal search. • The court reasoned the use of the trained dogs to enhance the sensory ability of the officers was the same as the use of thermal technology to detect heat variances in Kyllo. • It allowed law enforcement to gain information that would not have been discernable absent an outside sensory source. Special thanks to The National Clearinghouse for Science, Technology and the Law at Stetson for selected case summaries 3

Does a dog sniff outside of residential home constitute a search under the Fourth Amendment? State v. Rabb; 920 So. 2 d 1175 (Fla. App. Dist. 2006) • Using the holding and analysis of the United States Supreme Court in Kyllo v. United States, the court held that the use of drug sniffing dogs to detect substances located within the house amounted to an illegal search. • The court reasoned the use of the trained dogs to enhance the sensory ability of the officers was the same as the use of thermal technology to detect heat variances in Kyllo. • It allowed law enforcement to gain information that would not have been discernable absent an outside sensory source. Special thanks to The National Clearinghouse for Science, Technology and the Law at Stetson for selected case summaries 3

Does a dog sniff outside of residential home constitute a search under the Fourth Amendment? State v. Davis; 711 N. W. 2 d 841 (Minn. App. 2006) • The issue was whether a dog sniff in the first floor hallway of an apartment building to detect illegal drugs constitutes a search under the 4 th Amendment or the privacy clause of the Minnesota Constitution. • The court determined that there was not a privacy expectation in a public hallway of an apartment building because it was in common usage by other residents, guests, and building personnel. • The court found that under the state constitution privacy clause the dog sniff did constitute a search and required "a reasonable, articulable suspicion" of drug activity to legally use canine sensory detection. • The detection of the illegal drug activity occurred in the hallway, not the defendant's apartment. Thus, there was not an intrusion that would warrant a finding of probable cause to search the premises. 4

Does a dog sniff outside of residential home constitute a search under the Fourth Amendment? State v. Davis; 711 N. W. 2 d 841 (Minn. App. 2006) • The issue was whether a dog sniff in the first floor hallway of an apartment building to detect illegal drugs constitutes a search under the 4 th Amendment or the privacy clause of the Minnesota Constitution. • The court determined that there was not a privacy expectation in a public hallway of an apartment building because it was in common usage by other residents, guests, and building personnel. • The court found that under the state constitution privacy clause the dog sniff did constitute a search and required "a reasonable, articulable suspicion" of drug activity to legally use canine sensory detection. • The detection of the illegal drug activity occurred in the hallway, not the defendant's apartment. Thus, there was not an intrusion that would warrant a finding of probable cause to search the premises. 4

Does a dog sniff at a routine traffic stop violated privacy clauses and how long can motorist be detained waiting for K 9 unit? People v. Cabelles; 221 Ill. 2 d 282 (Ill. 2006) - The court found under previous Illinois cases addressing protected privacy interests the use of canine would not breach reasonable expectations of privacy or impermissibly intrude. The court briefly rejects Defendant's argument against the reliability of the dog sniff by finding that claims of false positives and widespread abuse of this technique to conduct searches was speculative and unsupported by the evidence. State v. Almazan; No. 05 CA 0098 -M (Ohio App. Dist. 2006) - The court notes that once a law enforcement officer determines there are "specific and articulable facts" showing criminal activity, an investigative stop is allowable and a drug sniffing dog may be used even absent suspicion of drug activity. Additionally, in reference to the particular assignment of error, the court found that the officer's testimony in the trial court as to the training and certification of the dog and his explanation as to why she could incorrectly detect an odor of drugs was sufficient to establish her reliability and training as a source of evidence. 5

Does a dog sniff at a routine traffic stop violated privacy clauses and how long can motorist be detained waiting for K 9 unit? People v. Cabelles; 221 Ill. 2 d 282 (Ill. 2006) - The court found under previous Illinois cases addressing protected privacy interests the use of canine would not breach reasonable expectations of privacy or impermissibly intrude. The court briefly rejects Defendant's argument against the reliability of the dog sniff by finding that claims of false positives and widespread abuse of this technique to conduct searches was speculative and unsupported by the evidence. State v. Almazan; No. 05 CA 0098 -M (Ohio App. Dist. 2006) - The court notes that once a law enforcement officer determines there are "specific and articulable facts" showing criminal activity, an investigative stop is allowable and a drug sniffing dog may be used even absent suspicion of drug activity. Additionally, in reference to the particular assignment of error, the court found that the officer's testimony in the trial court as to the training and certification of the dog and his explanation as to why she could incorrectly detect an odor of drugs was sufficient to establish her reliability and training as a source of evidence. 5

Does a dog sniff at a routine traffic stop violated privacy clauses and how long can motorist be detained waiting for K 9 unit? • State v. Meza; No. 04 -800 (Mont. 2006) - The court noted that under the Montana Constitution a dog sniff does constitute a search but only requires a particularized suspicion of drug-related activity to be allowable. • People v. Driggers; 221 Ill. 2 d 65 (Ill. 2006) - This court found that the officer legitimately detained Defendant in a traffic stop that lasted only five minutes and the dog only identified the presence of items he was not legally permitted to possess. • State v. Ofori; No. 0267 (Md. App. 2006) - The court held that a time period of approximately 20 minutes to allow the canine unit to arrive was reasonable once the police officer had a reasonable basis to suspect illegal contraband. As an aside, the court also notes that the probable cause created by a positive dog sniff is sufficient to both search and arrest drivers and/or passengers in a vehicle without additional information. 6

Does a dog sniff at a routine traffic stop violated privacy clauses and how long can motorist be detained waiting for K 9 unit? • State v. Meza; No. 04 -800 (Mont. 2006) - The court noted that under the Montana Constitution a dog sniff does constitute a search but only requires a particularized suspicion of drug-related activity to be allowable. • People v. Driggers; 221 Ill. 2 d 65 (Ill. 2006) - This court found that the officer legitimately detained Defendant in a traffic stop that lasted only five minutes and the dog only identified the presence of items he was not legally permitted to possess. • State v. Ofori; No. 0267 (Md. App. 2006) - The court held that a time period of approximately 20 minutes to allow the canine unit to arrive was reasonable once the police officer had a reasonable basis to suspect illegal contraband. As an aside, the court also notes that the probable cause created by a positive dog sniff is sufficient to both search and arrest drivers and/or passengers in a vehicle without additional information. 6

Does a dog sniff at a routine traffic stop violated privacy clauses and how long can motorist be detained waiting for K 9 unit? Wilson v. State; 847 N. E. 2 d 1064 (Ind. App. 2006) • Two factors are used to assess whether a traffic stop was unnecessarily prolonged. • First, the courts look to see if the purpose of the initial traffic stop was concluded, and • Second, whether a reasonable suspicion was present to justify a further detention of the vehicle. • In the present case, a request for drug sniffing dog was not made until after the purpose of the stop was completed and the defendant refused a request to search his car. • Additionally, the facts did not provide enough to raise a reasonable suspicion of illegal activity merely based on nervousness, watching patrol cars, and carrying $4000. 00 in cash. • Thus, the officers violated Defendant's Fourth Amendment rights by holding him after he refused a request to search his vehicle. 7

Does a dog sniff at a routine traffic stop violated privacy clauses and how long can motorist be detained waiting for K 9 unit? Wilson v. State; 847 N. E. 2 d 1064 (Ind. App. 2006) • Two factors are used to assess whether a traffic stop was unnecessarily prolonged. • First, the courts look to see if the purpose of the initial traffic stop was concluded, and • Second, whether a reasonable suspicion was present to justify a further detention of the vehicle. • In the present case, a request for drug sniffing dog was not made until after the purpose of the stop was completed and the defendant refused a request to search his car. • Additionally, the facts did not provide enough to raise a reasonable suspicion of illegal activity merely based on nervousness, watching patrol cars, and carrying $4000. 00 in cash. • Thus, the officers violated Defendant's Fourth Amendment rights by holding him after he refused a request to search his vehicle. 7

“Crime and Chemical Analysis”, 24 March 1989, Science, Vol. 243, Research News P. 1555. According to Lee Hearn, chief toxicologist for the Dade County Medical Examiner Department in Miami, tests show suggest that most of the currency in circulation in the United States has at least minute traces of cocaine. The bottom line is that any large amount of cash in the United States is likely to show traces of cocaine, Hearn said, which makes drug money confiscation programs problematical. “The police could go into any bank in the country and seize all their money”, he said. No drugs other than cocaine have been reported to be significantly contaminating paper currency. Trace amounts of heroin, phencyclidine, methamphetamine, methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and Δ 9 -tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) have been reported but in fewer than 10% of cases and in extremely trace amounts or not quantified. A recent study of 125 bills demonstrated THC contamination in 1. 6% of bills at an average amount of 100 ng (billionth of a gram). 8

“Crime and Chemical Analysis”, 24 March 1989, Science, Vol. 243, Research News P. 1555. According to Lee Hearn, chief toxicologist for the Dade County Medical Examiner Department in Miami, tests show suggest that most of the currency in circulation in the United States has at least minute traces of cocaine. The bottom line is that any large amount of cash in the United States is likely to show traces of cocaine, Hearn said, which makes drug money confiscation programs problematical. “The police could go into any bank in the country and seize all their money”, he said. No drugs other than cocaine have been reported to be significantly contaminating paper currency. Trace amounts of heroin, phencyclidine, methamphetamine, methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and Δ 9 -tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) have been reported but in fewer than 10% of cases and in extremely trace amounts or not quantified. A recent study of 125 bills demonstrated THC contamination in 1. 6% of bills at an average amount of 100 ng (billionth of a gram). 8

n 9 th U. S. Circuit Court of Appeals (U. S. v. $30, 060. 00, 1994 WL 613703 (Cal. ) upheld the dismissal of a forfeiture case stating that "… evidence that greater than 75% of all circulated money… is contaminated with drug residue, distinguish this case from our previous cases. We therefore hold that the narcotics detection dog's positive alert to Alexander's money, the packaging [30 rubber band bound stacks of $5, $10, $20, $50 and $100 bills in a plastic bag] and the amount [$30, 060] of Alexander's money, and his false accounts of the money's source and his own employment record is insufficient evidence to establish probable cause that the money was connected to drugs as required to warrant forfeiture. Citations in this decision include testimony that 90% of all U. S. cash contains sufficient quantities of cocaine to alert a narcotics detection dog. n n 9

n 9 th U. S. Circuit Court of Appeals (U. S. v. $30, 060. 00, 1994 WL 613703 (Cal. ) upheld the dismissal of a forfeiture case stating that "… evidence that greater than 75% of all circulated money… is contaminated with drug residue, distinguish this case from our previous cases. We therefore hold that the narcotics detection dog's positive alert to Alexander's money, the packaging [30 rubber band bound stacks of $5, $10, $20, $50 and $100 bills in a plastic bag] and the amount [$30, 060] of Alexander's money, and his false accounts of the money's source and his own employment record is insufficient evidence to establish probable cause that the money was connected to drugs as required to warrant forfeiture. Citations in this decision include testimony that 90% of all U. S. cash contains sufficient quantities of cocaine to alert a narcotics detection dog. n n 9

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. The steps needed to determine if there is enough cocaine on circulated currency to alert dogs: Determine exactly how much cocaine there is on circulated paper currency. Are there other drugs? Determine how little cocaine can be detected by properly trained detector dogs. Determine what volatile(s) dogs are detecting. Determine threshold of detection by detector dogs. Determine levels of these volatile(s) in street and purified cocaine. Determine where the volatile(s) are coming from. Determine how quickly the cocaine odor chemical(s) dissipate. Determine what non controlled substances contain these odor chemical(s) and in what amounts. 10

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. The steps needed to determine if there is enough cocaine on circulated currency to alert dogs: Determine exactly how much cocaine there is on circulated paper currency. Are there other drugs? Determine how little cocaine can be detected by properly trained detector dogs. Determine what volatile(s) dogs are detecting. Determine threshold of detection by detector dogs. Determine levels of these volatile(s) in street and purified cocaine. Determine where the volatile(s) are coming from. Determine how quickly the cocaine odor chemical(s) dissipate. Determine what non controlled substances contain these odor chemical(s) and in what amounts. 10

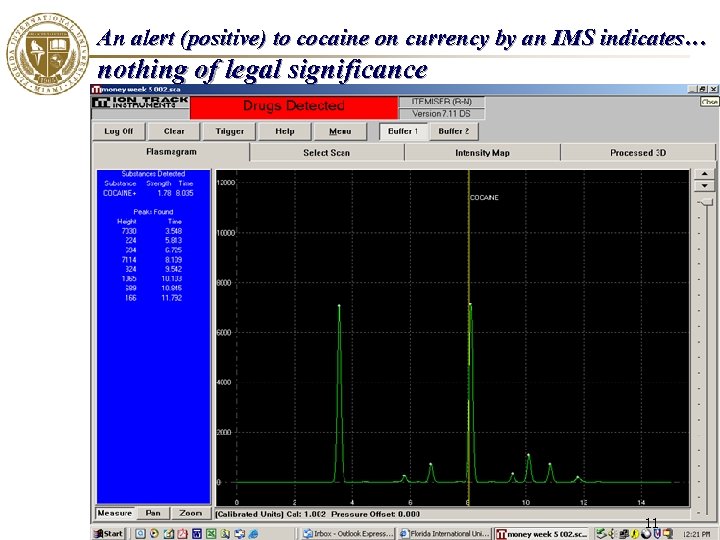

An alert (positive) to cocaine on currency by an IMS indicates… nothing of legal significance 11

An alert (positive) to cocaine on currency by an IMS indicates… nothing of legal significance 11

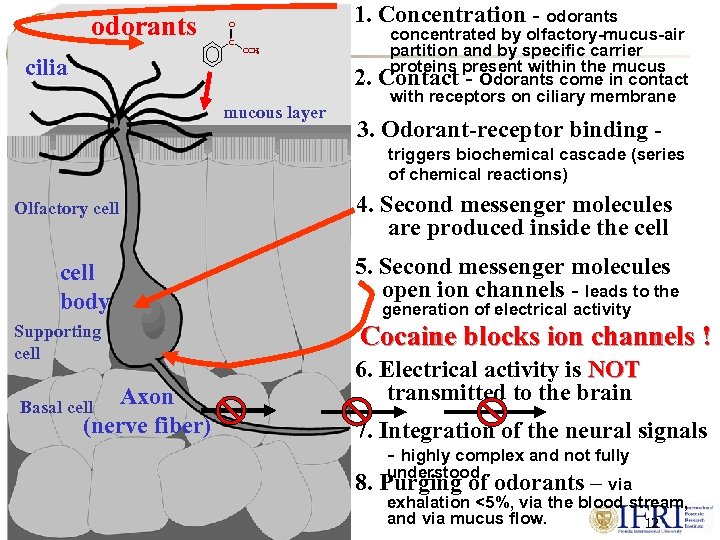

odorants cilia 1. Concentration - odorants O C OCH 3 2. mucous layer concentrated by olfactory-mucus-air partition and by specific carrier proteins present within the mucus Contact - Odorants come in contact with receptors on ciliary membrane 3. Odorant-receptor binding triggers biochemical cascade (series of chemical reactions) Olfactory cell body Supporting cell Axon (nerve fiber) Basal cell 4. Second messenger molecules are produced inside the cell 5. Second messenger molecules open ion channels - leads to the generation of electrical activity Cocaine blocks ion channels ! 6. Electrical activity is NOT transmitted to the brain 7. Integration of the neural signals - highly complex and not fully understood 8. Purging of odorants – via exhalation <5%, via the blood stream, and via mucus flow. 12

odorants cilia 1. Concentration - odorants O C OCH 3 2. mucous layer concentrated by olfactory-mucus-air partition and by specific carrier proteins present within the mucus Contact - Odorants come in contact with receptors on ciliary membrane 3. Odorant-receptor binding triggers biochemical cascade (series of chemical reactions) Olfactory cell body Supporting cell Axon (nerve fiber) Basal cell 4. Second messenger molecules are produced inside the cell 5. Second messenger molecules open ion channels - leads to the generation of electrical activity Cocaine blocks ion channels ! 6. Electrical activity is NOT transmitted to the brain 7. Integration of the neural signals - highly complex and not fully understood 8. Purging of odorants – via exhalation <5%, via the blood stream, and via mucus flow. 12

![Some Decomposition Pathways of Illicit Cocaine - 3 -(benzoyloxy)-8 -methyl-8 azabicyclo-[3. 2. 1]octane-2 -carboxylic Some Decomposition Pathways of Illicit Cocaine - 3 -(benzoyloxy)-8 -methyl-8 azabicyclo-[3. 2. 1]octane-2 -carboxylic](https://present5.com/presentation/f08440e0a4aff44ac969c61985d25fef/image-13.jpg) Some Decomposition Pathways of Illicit Cocaine - 3 -(benzoyloxy)-8 -methyl-8 azabicyclo-[3. 2. 1]octane-2 -carboxylic acid methyl ester Cocaine in methanol is 4% methyl benzoate in 1 week Me lati thy gent ng a Solid cocaine remains 0. 0007% methyl benzoate 13

Some Decomposition Pathways of Illicit Cocaine - 3 -(benzoyloxy)-8 -methyl-8 azabicyclo-[3. 2. 1]octane-2 -carboxylic acid methyl ester Cocaine in methanol is 4% methyl benzoate in 1 week Me lati thy gent ng a Solid cocaine remains 0. 0007% methyl benzoate 13

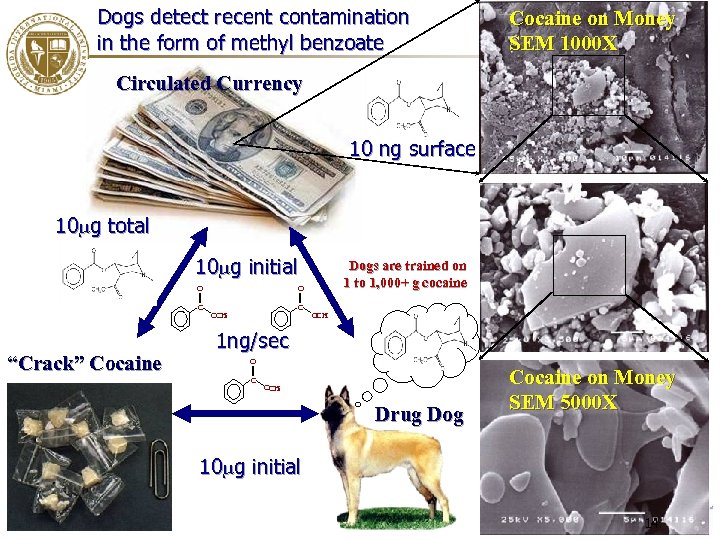

Dogs detect recent contamination in the form of methyl benzoate Cocaine on Money SEM 1000 X Circulated Currency 10 ng surface 10 g total 10 g initial O O C “Crack” Cocaine Dogs are trained on 1 to 1, 000+ g cocaine C OCH 3 1 ng/sec O C OCH 3 Drug Dog Cocaine on Money SEM 5000 X 10 g initial 14

Dogs detect recent contamination in the form of methyl benzoate Cocaine on Money SEM 1000 X Circulated Currency 10 ng surface 10 g total 10 g initial O O C “Crack” Cocaine Dogs are trained on 1 to 1, 000+ g cocaine C OCH 3 1 ng/sec O C OCH 3 Drug Dog Cocaine on Money SEM 5000 X 10 g initial 14

US v. $22, 474. 00 IN U. S. CURRENCY, No 99 -16611 (9 th Cir. April 18, 2001) n n n “Here, the government presented evidence that the dog would not alert to cocaine residue found on currency in general circulation. Rather, the dog was trained to, and would only, alert to the odor of a chemical by-product of cocaine called methyl benzoate. Moreover, the government provided evidence that unless the currency Mahone was carrying had recently been in the proximity of cocaine, the detection dog would not have alerted to it. That Evidence was not disputed. In addition to the undisputed evidence of the sophisticated dog sniff, there are numerous other undisputed facts which, in the aggregate, establish probable cause to believe that the money seized from Mahone was to be (or had been) used in drug related activity. ” 15

US v. $22, 474. 00 IN U. S. CURRENCY, No 99 -16611 (9 th Cir. April 18, 2001) n n n “Here, the government presented evidence that the dog would not alert to cocaine residue found on currency in general circulation. Rather, the dog was trained to, and would only, alert to the odor of a chemical by-product of cocaine called methyl benzoate. Moreover, the government provided evidence that unless the currency Mahone was carrying had recently been in the proximity of cocaine, the detection dog would not have alerted to it. That Evidence was not disputed. In addition to the undisputed evidence of the sophisticated dog sniff, there are numerous other undisputed facts which, in the aggregate, establish probable cause to believe that the money seized from Mahone was to be (or had been) used in drug related activity. ” 15

HUMAN SCENT EVIDENCE • Hodge v. State, 98 Ala. 10 (Ala. 1893). The state Supreme Court acknowledged that dogs may be trained to follow the tracks of a human being with considerable certainty and accuracy. It held that testimony regarding the tracking by the dog was competent to go to the jury for consideration, in connection with the other evidence, as a circumstance connecting the defendant with the crime. • State v. Hall, 4 Ohio Dec. 147, 148 (Ohio Misc. 1896) Court stated that in cases where bloodhound evidence is used, full opportunity should be given to inquire into the breeding, training and testing of the dog, and to all the circumstances attending the trailing in the case on trial, and to the manner in which the dog then acted and was handled by the person having it in charge. The court held that there was no error in admitting the evidence offered by the state. • Brott v. State, 70 Neb. 395 (Neb. 1903). Bloodhounds trailed the burglar to defendant's house. The court pointed out that dogs are frequently right and are frequently wrong in their conclusions and, as a result, is unsafe evidence. 16

HUMAN SCENT EVIDENCE • Hodge v. State, 98 Ala. 10 (Ala. 1893). The state Supreme Court acknowledged that dogs may be trained to follow the tracks of a human being with considerable certainty and accuracy. It held that testimony regarding the tracking by the dog was competent to go to the jury for consideration, in connection with the other evidence, as a circumstance connecting the defendant with the crime. • State v. Hall, 4 Ohio Dec. 147, 148 (Ohio Misc. 1896) Court stated that in cases where bloodhound evidence is used, full opportunity should be given to inquire into the breeding, training and testing of the dog, and to all the circumstances attending the trailing in the case on trial, and to the manner in which the dog then acted and was handled by the person having it in charge. The court held that there was no error in admitting the evidence offered by the state. • Brott v. State, 70 Neb. 395 (Neb. 1903). Bloodhounds trailed the burglar to defendant's house. The court pointed out that dogs are frequently right and are frequently wrong in their conclusions and, as a result, is unsafe evidence. 16

Jump ahead about 100 years… • United States v. Hornbeck, 63 Fed. Appx. 340 (9 th Cir. 2003). The defendant asserted that the evidence was inherently unreliable, and therefore could not meet the methodology and reliability requirements of Daubert. • The court found that the evidence made it more likely that defendant was the bank robber by connecting the car with the evidence from the robbery to the defendant. • The court noted that when the district court conducted a pretrial hearing on defendant’s motion in limine to exclude the dog scent evidence, it assessed the reliability of the evidence and determined that a proper foundation had been established for the admission of the scent tracking evidence. The district court noted that the K-9 Trainer had successfully alerted police to defendants for eight years and the bloodhound had been used in 22 criminal investigations. • The court concluded that in light of the other evidence connecting defendant to the robbery, any alleged error would have been harmless and as a result, the district court did not abuse its discretion when it determined that the canine tracking evidence was relevant and not unfairly prejudicial. • The judgment was affirmed on this and other grounds. 17

Jump ahead about 100 years… • United States v. Hornbeck, 63 Fed. Appx. 340 (9 th Cir. 2003). The defendant asserted that the evidence was inherently unreliable, and therefore could not meet the methodology and reliability requirements of Daubert. • The court found that the evidence made it more likely that defendant was the bank robber by connecting the car with the evidence from the robbery to the defendant. • The court noted that when the district court conducted a pretrial hearing on defendant’s motion in limine to exclude the dog scent evidence, it assessed the reliability of the evidence and determined that a proper foundation had been established for the admission of the scent tracking evidence. The district court noted that the K-9 Trainer had successfully alerted police to defendants for eight years and the bloodhound had been used in 22 criminal investigations. • The court concluded that in light of the other evidence connecting defendant to the robbery, any alleged error would have been harmless and as a result, the district court did not abuse its discretion when it determined that the canine tracking evidence was relevant and not unfairly prejudicial. • The judgment was affirmed on this and other grounds. 17

• Grant v. City of Long Beach, 2003 U. S. App. LEXIS 13038 (9 th Cir. 2003). From a scent pad created at the crime scene, a police bloodhound attempted to track a rape assailant. The dog eventually led the officers to a twenty unit apartment building almost two miles away from the crime scene. • The officers did not provide any evidence regarding the dog’s accuracy rate to bolster her reliability. • The court stated that while it recognized the importance of dogs in police investigations, it also adhered to the requirement of reliability as a safeguard against faulty canine identifications. • It concluded that the facts of this case provided no reason to depart from a showing of the dog's reliability and the jury had good reason to question the reliability of the dog's "identification. " • Appellee sued the City of Long Beach, the Long Beach Police Department, and the two police officers that spearheaded the investigation under 42 U. S. C. § 1983 for false arrest and false imprisonment. • There was a jury award of $ 1. 75 million in compensatory and punitive damages in favor of appellee. 18

• Grant v. City of Long Beach, 2003 U. S. App. LEXIS 13038 (9 th Cir. 2003). From a scent pad created at the crime scene, a police bloodhound attempted to track a rape assailant. The dog eventually led the officers to a twenty unit apartment building almost two miles away from the crime scene. • The officers did not provide any evidence regarding the dog’s accuracy rate to bolster her reliability. • The court stated that while it recognized the importance of dogs in police investigations, it also adhered to the requirement of reliability as a safeguard against faulty canine identifications. • It concluded that the facts of this case provided no reason to depart from a showing of the dog's reliability and the jury had good reason to question the reliability of the dog's "identification. " • Appellee sued the City of Long Beach, the Long Beach Police Department, and the two police officers that spearheaded the investigation under 42 U. S. C. § 1983 for false arrest and false imprisonment. • There was a jury award of $ 1. 75 million in compensatory and punitive damages in favor of appellee. 18

• In Winston v. State (Tex. App. 2002), an appellate court noted that 37 states and the District of Columbia admit scent trailing evidence to prove the identity of the accused. “For purposes of judging the reliability of evidence based on a dog’s ability to distinguish between scents, ” the court wrote, “we believe there is little distinction between a scent lineup and a situation where a dog is required to track an individual’s scent over an area traversed by multiple persons. ” • A California appellate court criticized this approach as too simplistic in People v. Mitchell (2003) 110 Cal. App. 4 th 772 and stated its concern about “the absence of any evidence that every person has a scent so unique that it provides an accurate basis for a scent identification lineup. ” • Al-Amin v. State, 278 Ga. 74 (Ga. 2004). The defendant asserted that the trial court erred in admitting evidence that he was tracked by dogs when he was arrested in Alabama because there was no scientific evidence shown of the reliability of the evidence. The Georgia Supreme Court found that the dogs were used to flush the defendant out of a wooded area and a showing of the qualifications of the dogs as tracking dogs was not necessary. 19

• In Winston v. State (Tex. App. 2002), an appellate court noted that 37 states and the District of Columbia admit scent trailing evidence to prove the identity of the accused. “For purposes of judging the reliability of evidence based on a dog’s ability to distinguish between scents, ” the court wrote, “we believe there is little distinction between a scent lineup and a situation where a dog is required to track an individual’s scent over an area traversed by multiple persons. ” • A California appellate court criticized this approach as too simplistic in People v. Mitchell (2003) 110 Cal. App. 4 th 772 and stated its concern about “the absence of any evidence that every person has a scent so unique that it provides an accurate basis for a scent identification lineup. ” • Al-Amin v. State, 278 Ga. 74 (Ga. 2004). The defendant asserted that the trial court erred in admitting evidence that he was tracked by dogs when he was arrested in Alabama because there was no scientific evidence shown of the reliability of the evidence. The Georgia Supreme Court found that the dogs were used to flush the defendant out of a wooded area and a showing of the qualifications of the dogs as tracking dogs was not necessary. 19

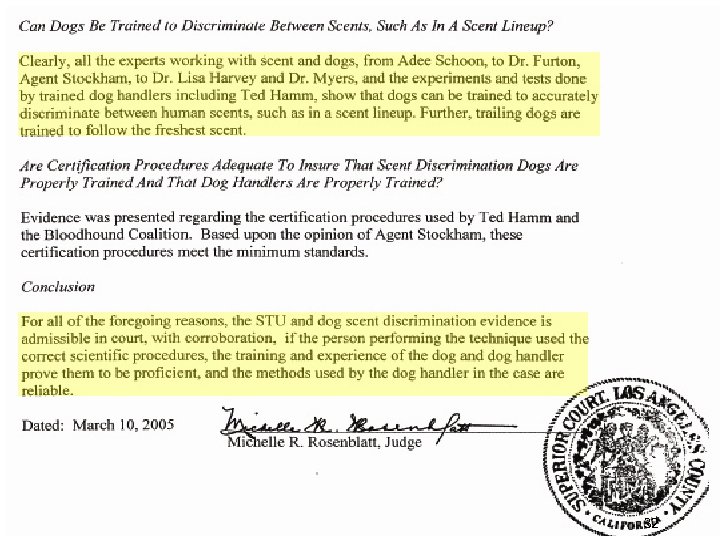

People v. Willis, 115 Cal. App. 4 th 379 (Cal. Ct. App. 2004). • The court held that the STU was a novel device used in the furtherance of a new technique and, therefore, was subject to Kelly analysis. • The dog handler testified about the STU and the dog scent identification, but he was not a scientist or engineer and, therefore, was not qualified to testify about the characteristics of the STU or its general acceptance in the scientific community. • There was also a foundational weakness in the dog identification evidence, because there was no evidence on how long a scent remained on an object or at a location, whether every person's scent was unique, and the adequacy of the certification procedures for scent identification. However, the court held that there was no prejudice from the admission of such evidence in light of the overwhelming other evidence of defendant's guilt. 20

People v. Willis, 115 Cal. App. 4 th 379 (Cal. Ct. App. 2004). • The court held that the STU was a novel device used in the furtherance of a new technique and, therefore, was subject to Kelly analysis. • The dog handler testified about the STU and the dog scent identification, but he was not a scientist or engineer and, therefore, was not qualified to testify about the characteristics of the STU or its general acceptance in the scientific community. • There was also a foundational weakness in the dog identification evidence, because there was no evidence on how long a scent remained on an object or at a location, whether every person's scent was unique, and the adequacy of the certification procedures for scent identification. However, the court held that there was no prejudice from the admission of such evidence in light of the overwhelming other evidence of defendant's guilt. 20

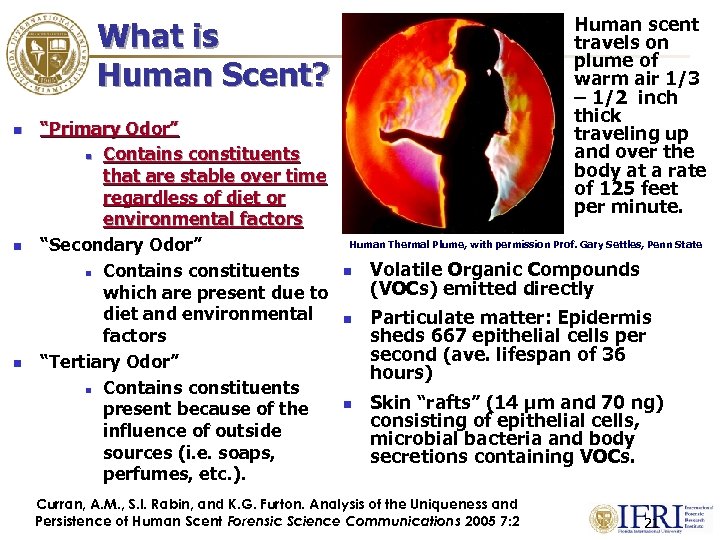

Human scent travels on plume of warm air 1/3 – 1/2 inch thick traveling up and over the body at a rate of 125 feet per minute. What is Human Scent? n n n “Primary Odor” n Contains constituents that are stable over time regardless of diet or environmental factors “Secondary Odor” n Contains constituents which are present due to diet and environmental factors “Tertiary Odor” n Contains constituents present because of the influence of outside sources (i. e. soaps, perfumes, etc. ). Human Thermal Plume, with permission Prof. Gary Settles, Penn State n n n Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) emitted directly Particulate matter: Epidermis sheds 667 epithelial cells per second (ave. lifespan of 36 hours) Skin “rafts” (14 μm and 70 ng) consisting of epithelial cells, microbial bacteria and body secretions containing VOCs. Curran, A. M. , S. I. Rabin, and K. G. Furton. Analysis of the Uniqueness and Persistence of Human Scent Forensic Science Communications 2005 7: 2 21

Human scent travels on plume of warm air 1/3 – 1/2 inch thick traveling up and over the body at a rate of 125 feet per minute. What is Human Scent? n n n “Primary Odor” n Contains constituents that are stable over time regardless of diet or environmental factors “Secondary Odor” n Contains constituents which are present due to diet and environmental factors “Tertiary Odor” n Contains constituents present because of the influence of outside sources (i. e. soaps, perfumes, etc. ). Human Thermal Plume, with permission Prof. Gary Settles, Penn State n n n Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) emitted directly Particulate matter: Epidermis sheds 667 epithelial cells per second (ave. lifespan of 36 hours) Skin “rafts” (14 μm and 70 ng) consisting of epithelial cells, microbial bacteria and body secretions containing VOCs. Curran, A. M. , S. I. Rabin, and K. G. Furton. Analysis of the Uniqueness and Persistence of Human Scent Forensic Science Communications 2005 7: 2 21

What countries use dogs for scent ID line-ups? l l l l l Poland: > 110 dogs Hungary: > 50 dogs Netherlands: 15 dogs Germany: 8 dogs Denmark: 6 dogs Belgium: 2 dogs Finland: 4 dogs Also: Russia, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Lithuania, France, Japan U. S. : 2 dogs? Specific protocol l Different number of dogs are used for a specific comparison: 3 dogs in Germany and Denmark 2 dogs in Poland 22 1 dog in Hungary, Netherlands and Belgium

What countries use dogs for scent ID line-ups? l l l l l Poland: > 110 dogs Hungary: > 50 dogs Netherlands: 15 dogs Germany: 8 dogs Denmark: 6 dogs Belgium: 2 dogs Finland: 4 dogs Also: Russia, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Lithuania, France, Japan U. S. : 2 dogs? Specific protocol l Different number of dogs are used for a specific comparison: 3 dogs in Germany and Denmark 2 dogs in Poland 22 1 dog in Hungary, Netherlands and Belgium

Law Enforcement Uses of Collected Human Scent • Trailing • Specialized Bloodhounds • Human Scent Lineup Identifications 23

Law Enforcement Uses of Collected Human Scent • Trailing • Specialized Bloodhounds • Human Scent Lineup Identifications 23

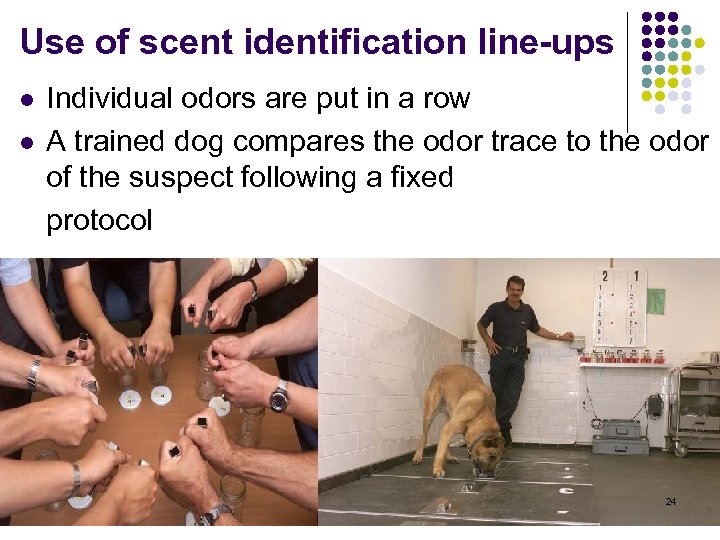

Use of scent identification line-ups l l Individual odors are put in a row A trained dog compares the odor trace to the odor of the suspect following a fixed protocol 24

Use of scent identification line-ups l l Individual odors are put in a row A trained dog compares the odor trace to the odor of the suspect following a fixed protocol 24

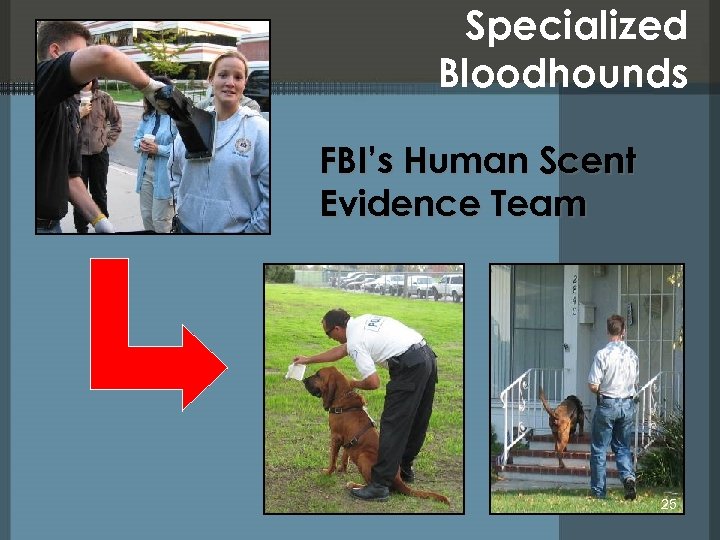

Specialized Bloodhounds FBI’s Human Scent Evidence Team 25

Specialized Bloodhounds FBI’s Human Scent Evidence Team 25

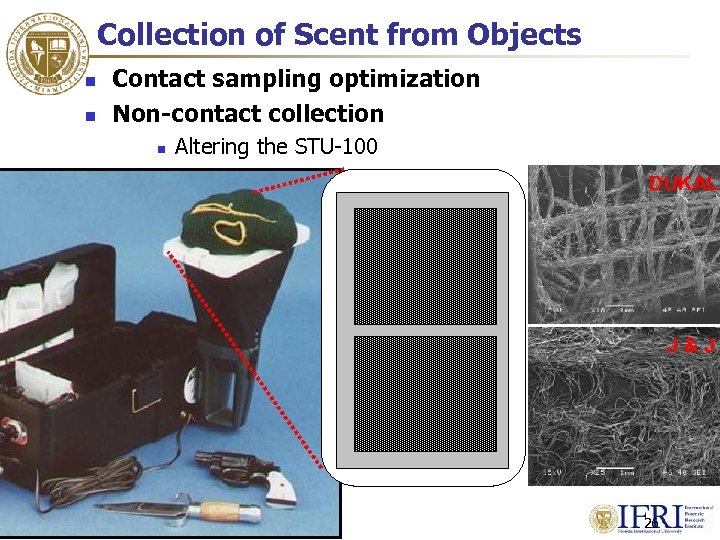

Collection of Scent from Objects n n Contact sampling optimization Non-contact collection n Altering the STU-100 DUKAL J&J 26

Collection of Scent from Objects n n Contact sampling optimization Non-contact collection n Altering the STU-100 DUKAL J&J 26

Evaluation of Storage Materials • There is currently no standardized material used to store collected human scent. • These materials have yet to be optimized. 27

Evaluation of Storage Materials • There is currently no standardized material used to store collected human scent. • These materials have yet to be optimized. 27

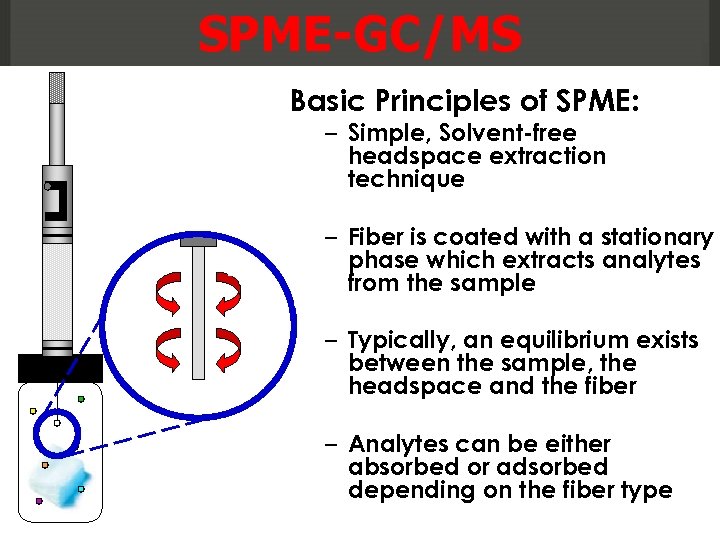

SPME-GC/MS Basic Principles of SPME: SPME Fiber GC/MS Instrument – Simple, Solvent-free headspace extraction technique – Fiber is coated with a stationary phase which extracts analytes from the sample – Typically, an equilibrium exists between the sample, the headspace and the fiber Data – Analytes Processor can be either absorbed or adsorbed depending on the fiber type 28

SPME-GC/MS Basic Principles of SPME: SPME Fiber GC/MS Instrument – Simple, Solvent-free headspace extraction technique – Fiber is coated with a stationary phase which extracts analytes from the sample – Typically, an equilibrium exists between the sample, the headspace and the fiber Data – Analytes Processor can be either absorbed or adsorbed depending on the fiber type 28

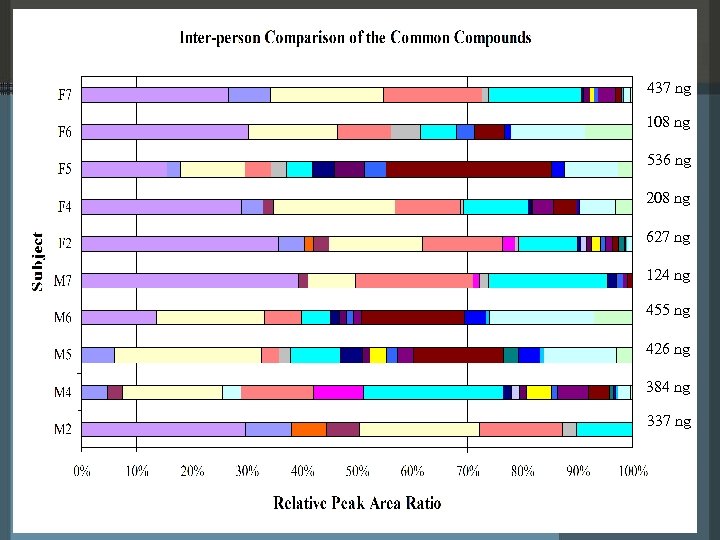

437 ng 108 ng 536 ng 208 ng 627 ng 124 ng 455 ng 426 ng 384 ng 337 ng 29

437 ng 108 ng 536 ng 208 ng 627 ng 124 ng 455 ng 426 ng 384 ng 337 ng 29

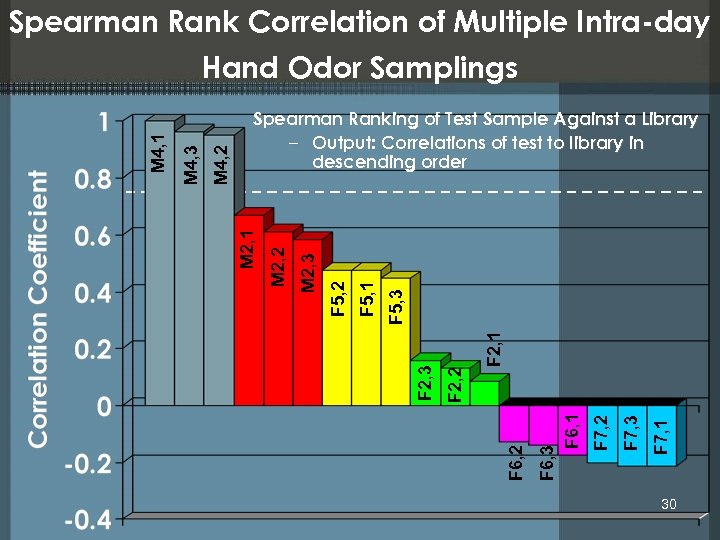

Spearman Rank Correlation of Multiple Intra-day F 2, 1 F 7, 3 F 7, 2 F 6, 3 F 6, 1 F 6, 2 F 2, 3 F 5, 1 F 5, 2 M 2, 3 M 2, 2 Spearman Ranking of Test Sample Against a Library – Output: Correlations of test to library in descending order M 2, 1 M 4, 2 M 4, 3 M 4, 1 Hand Odor Samplings 30

Spearman Rank Correlation of Multiple Intra-day F 2, 1 F 7, 3 F 7, 2 F 6, 3 F 6, 1 F 6, 2 F 2, 3 F 5, 1 F 5, 2 M 2, 3 M 2, 2 Spearman Ranking of Test Sample Against a Library – Output: Correlations of test to library in descending order M 2, 1 M 4, 2 M 4, 3 M 4, 1 Hand Odor Samplings 30

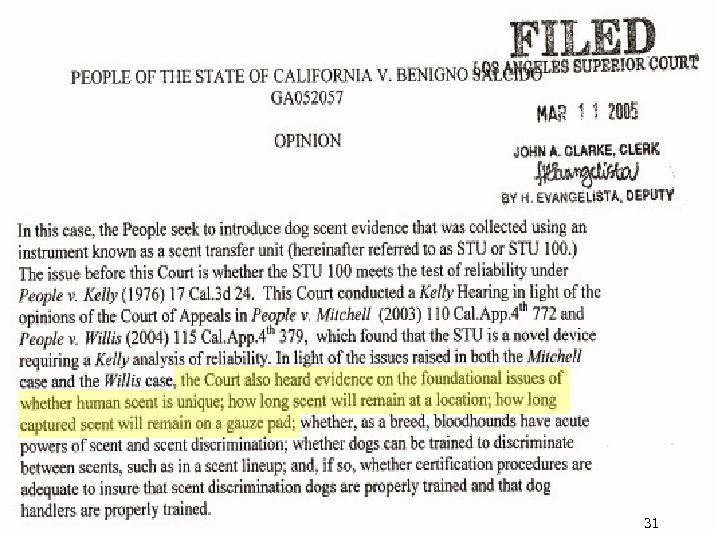

31

31

32

32

www. swgdog. org Scientific The need for global Working cooperation and Group on understanding Dog & Orthogonal detector Guidelines 33

www. swgdog. org Scientific The need for global Working cooperation and Group on understanding Dog & Orthogonal detector Guidelines 33

Standardization events leading up to establishing SWGDOG • • • FIU/IFRI houses research programs in instrumental and K 9 detection since 1994 and, working with the NFSTC, piloted a canine trainer and detection team certification program in 1998 with independent scientific validation. From 1999 -2003 the Interpol European Working Group on the Use of Police Dogs in Crime Investigation (IEWGPR) completed recommendations aimed at improving the efficiency of the use of police dogs. At the 2 nd, 3 rd and 4 th National Detector Dog Conferences in 2001, 2003 and 2005, co-hosted by IFRI and Auburn University, general best practices for detector dog teams were drafted and refined. A SWGDOG organizational meeting was held on 1/15/04 and bylaws ratified for SWGDOG on 9/1/04 by the Executive Board, which included the chair of the IEWGPR. In 2005, funding was secured and 55 SWGDOG members were selected and meetings begun September 2005. An essential aspect of SWGDOG is local, state, national and international representation. 34

Standardization events leading up to establishing SWGDOG • • • FIU/IFRI houses research programs in instrumental and K 9 detection since 1994 and, working with the NFSTC, piloted a canine trainer and detection team certification program in 1998 with independent scientific validation. From 1999 -2003 the Interpol European Working Group on the Use of Police Dogs in Crime Investigation (IEWGPR) completed recommendations aimed at improving the efficiency of the use of police dogs. At the 2 nd, 3 rd and 4 th National Detector Dog Conferences in 2001, 2003 and 2005, co-hosted by IFRI and Auburn University, general best practices for detector dog teams were drafted and refined. A SWGDOG organizational meeting was held on 1/15/04 and bylaws ratified for SWGDOG on 9/1/04 by the Executive Board, which included the chair of the IEWGPR. In 2005, funding was secured and 55 SWGDOG members were selected and meetings begun September 2005. An essential aspect of SWGDOG is local, state, national and international representation. 34

SWGDOG is managed by FIU and funded by FBI, NIJ and DHS SWGDOG Subcommittees and target timetable for posting of each best practice guideline 1. Unification of terminology (4/2006) 2. General guidelines for training, certification, and maintenance 4/ 2006) 3. Selection of serviceable dogs and replacement systems (9/2006) 4. Kenneling, keeping, and health care (9/2006) 5. Selection and training of handlers and instructors (9/2006) 6. Procedures on presenting evidence in court (September 2006) 7. Research and technology (3/2007) 8. Substance detector dogs: Agriculture; Arson; Chem. /Bio. ; Drugs; Explosives; Human remains; Other/Misc. (3/2007) 9. Scent dogs: Scent identification; Search and Rescue; Trailing dogs; Tracking dogs (3/2007) 35

SWGDOG is managed by FIU and funded by FBI, NIJ and DHS SWGDOG Subcommittees and target timetable for posting of each best practice guideline 1. Unification of terminology (4/2006) 2. General guidelines for training, certification, and maintenance 4/ 2006) 3. Selection of serviceable dogs and replacement systems (9/2006) 4. Kenneling, keeping, and health care (9/2006) 5. Selection and training of handlers and instructors (9/2006) 6. Procedures on presenting evidence in court (September 2006) 7. Research and technology (3/2007) 8. Substance detector dogs: Agriculture; Arson; Chem. /Bio. ; Drugs; Explosives; Human remains; Other/Misc. (3/2007) 9. Scent dogs: Scent identification; Search and Rescue; Trailing dogs; Tracking dogs (3/2007) 35