47c6aed6f81d6410a2247a42a15b2bc7.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 36

* For Best Viewing: Open in Slide Show Mode Click on icon or From the View menu, select the Slide Show option * To help you as you prepare a talk, we have included the relevant text from ITC in the notes pages of each slide © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

Terms of Use ▪ The In the Clinic® slide sets are owned and copyrighted by the American College of Physicians (ACP). All text, graphics, trademarks, and other intellectual property incorporated into the slide sets remain the sole and exclusive property of ACP. The slide sets may be used only by the person who downloads or purchases them and only for the purpose of presenting them during not-for-profit educational activities. Users may incorporate the entire slide set or selected individual slides into their own teaching presentations but may not alter the content of the slides in any way or remove the ACP copyright notice. Users may make print copies for use as hand-outs for the audience the user is personally addressing but may not otherwise reproduce or distribute the slides by any means or media, including but not limited to sending them as e-mail attachments, posting them on Internet or Intranet sites, publishing them in meeting proceedings, or making them available for sale or distribution in any unauthorized form, without the express written permission of the ACP. Unauthorized use of the In the Clinic slide sets constitutes copyright infringement. © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

in the clinic Deep Venous Thrombosis © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

DVT versus VTE Ø DVT refers to Deep Venous Thrombosis, which is the focus of this material Ø VTE refers to Venous Thrombo. Embolism q. VTE includes DVT plus the embolic consequences of DVT © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

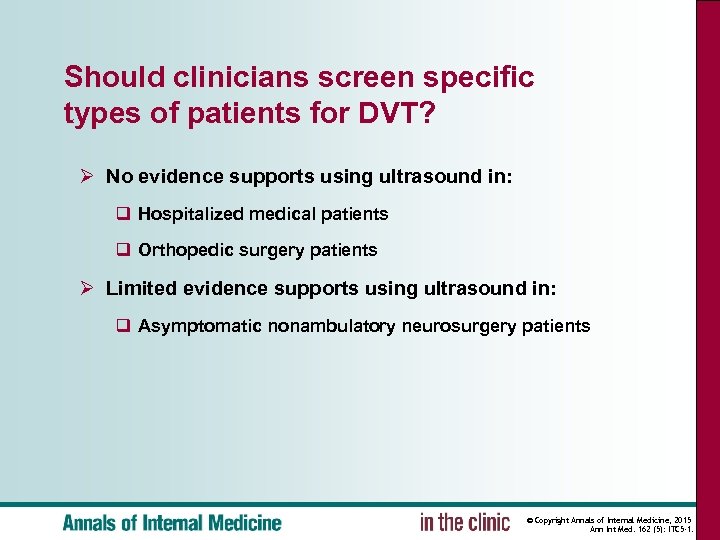

Should clinicians screen specific types of patients for DVT? Ø No evidence supports using ultrasound in: q Hospitalized medical patients q Orthopedic surgery patients Ø Limited evidence supports using ultrasound in: q Asymptomatic nonambulatory neurosurgery patients © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

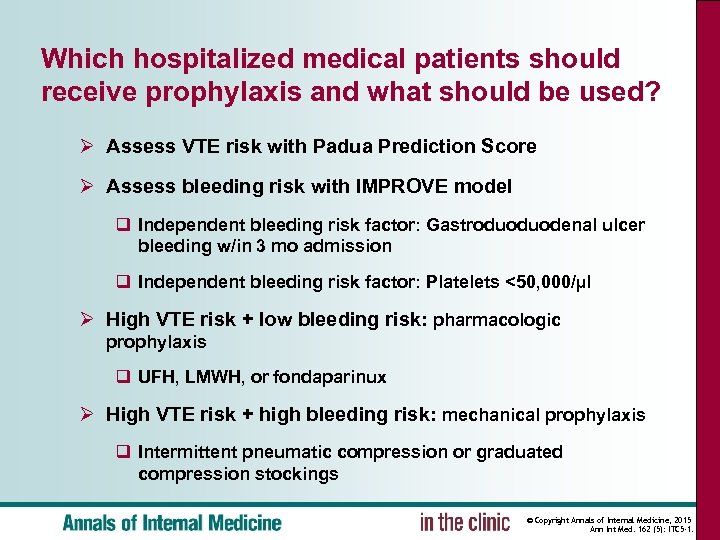

Which hospitalized medical patients should receive prophylaxis and what should be used? Ø Assess VTE risk with Padua Prediction Score Ø Assess bleeding risk with IMPROVE model q Independent bleeding risk factor: Gastroduoduodenal ulcer bleeding w/in 3 mo admission q Independent bleeding risk factor: Platelets <50, 000/µl Ø High VTE risk + low bleeding risk: pharmacologic prophylaxis q UFH, LMWH, or fondaparinux Ø High VTE risk + high bleeding risk: mechanical prophylaxis q Intermittent pneumatic compression or graduated compression stockings © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

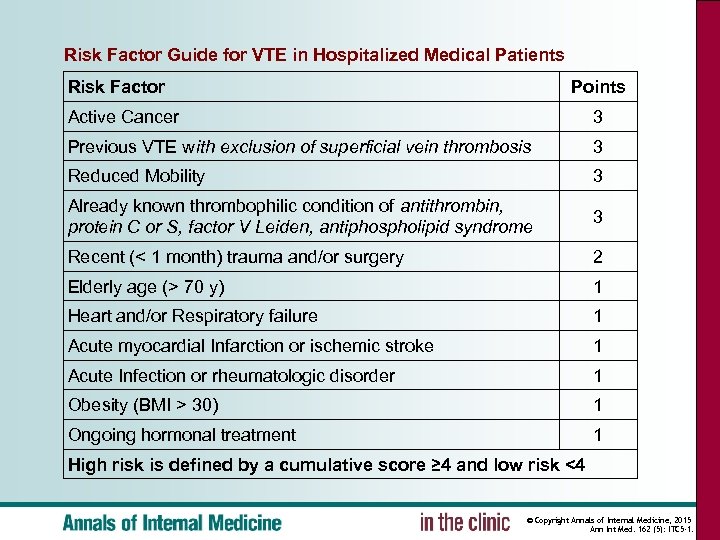

Risk Factor Guide for VTE in Hospitalized Medical Patients Risk Factor Points Active Cancer 3 Previous VTE with exclusion of superficial vein thrombosis 3 Reduced Mobility 3 Already known thrombophilic condition of antithrombin, protein C or S, factor V Leiden, antiphospholipid syndrome 3 Recent (< 1 month) trauma and/or surgery 2 Elderly age (> 70 y) 1 Heart and/or Respiratory failure 1 Acute myocardial Infarction or ischemic stroke 1 Acute Infection or rheumatologic disorder 1 Obesity (BMI > 30) 1 Ongoing hormonal treatment 1 High risk is defined by a cumulative score ≥ 4 and low risk <4 © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

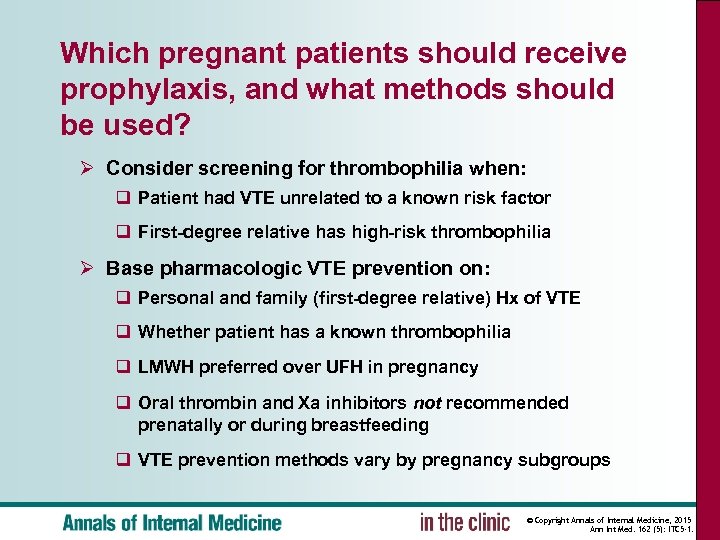

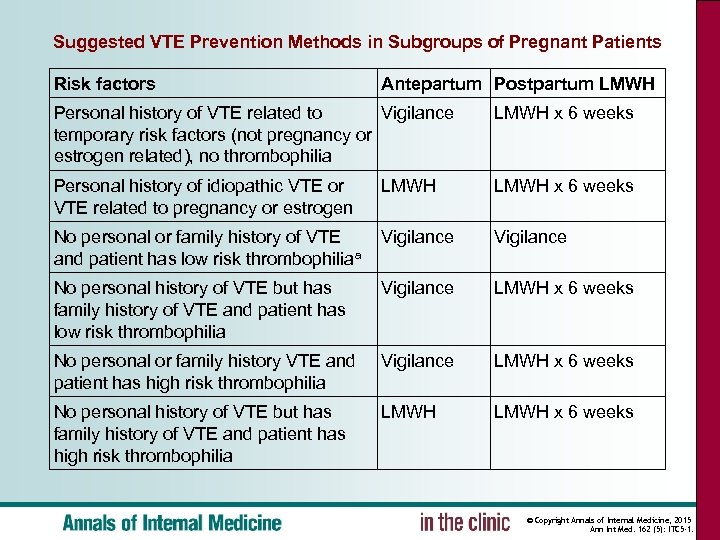

Which pregnant patients should receive prophylaxis, and what methods should be used? Ø Consider screening for thrombophilia when: q Patient had VTE unrelated to a known risk factor q First-degree relative has high-risk thrombophilia Ø Base pharmacologic VTE prevention on: q Personal and family (first-degree relative) Hx of VTE q Whether patient has a known thrombophilia q LMWH preferred over UFH in pregnancy q Oral thrombin and Xa inhibitors not recommended prenatally or during breastfeeding q VTE prevention methods vary by pregnancy subgroups © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

Suggested VTE Prevention Methods in Subgroups of Pregnant Patients Risk factors Antepartum Postpartum LMWH Personal history of VTE related to Vigilance temporary risk factors (not pregnancy or estrogen related), no thrombophilia LMWH x 6 weeks Personal history of idiopathic VTE or VTE related to pregnancy or estrogen LMWH x 6 weeks No personal or family history of VTE and patient has low risk thrombophiliaa Vigilance No personal history of VTE but has family history of VTE and patient has low risk thrombophilia Vigilance LMWH x 6 weeks No personal or family history VTE and patient has high risk thrombophilia Vigilance LMWH x 6 weeks No personal history of VTE but has family history of VTE and patient has high risk thrombophilia LMWH x 6 weeks © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

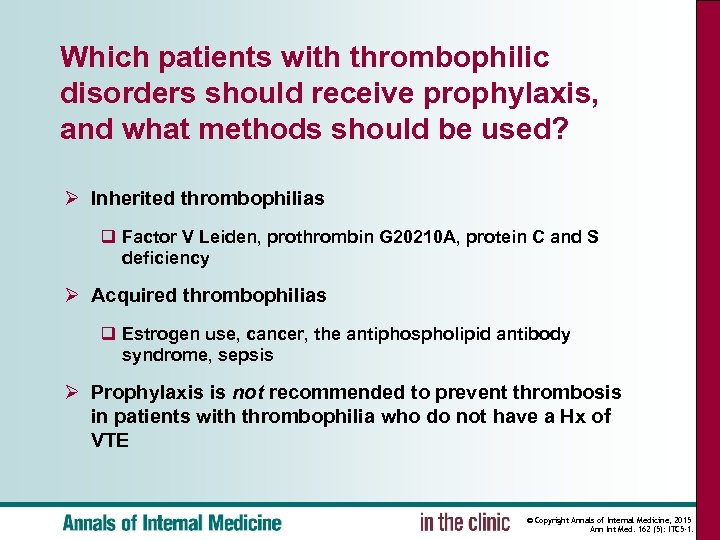

Which patients with thrombophilic disorders should receive prophylaxis, and what methods should be used? Ø Inherited thrombophilias q Factor V Leiden, prothrombin G 20210 A, protein C and S deficiency Ø Acquired thrombophilias q Estrogen use, cancer, the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, sepsis Ø Prophylaxis is not recommended to prevent thrombosis in patients with thrombophilia who do not have a Hx of VTE © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

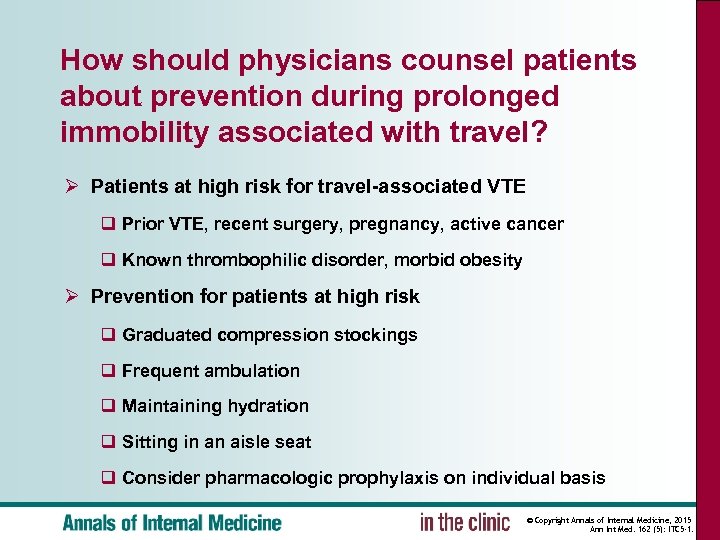

How should physicians counsel patients about prevention during prolonged immobility associated with travel? Ø Patients at high risk for travel-associated VTE q Prior VTE, recent surgery, pregnancy, active cancer q Known thrombophilic disorder, morbid obesity Ø Prevention for patients at high risk q Graduated compression stockings q Frequent ambulation q Maintaining hydration q Sitting in an aisle seat q Consider pharmacologic prophylaxis on individual basis © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

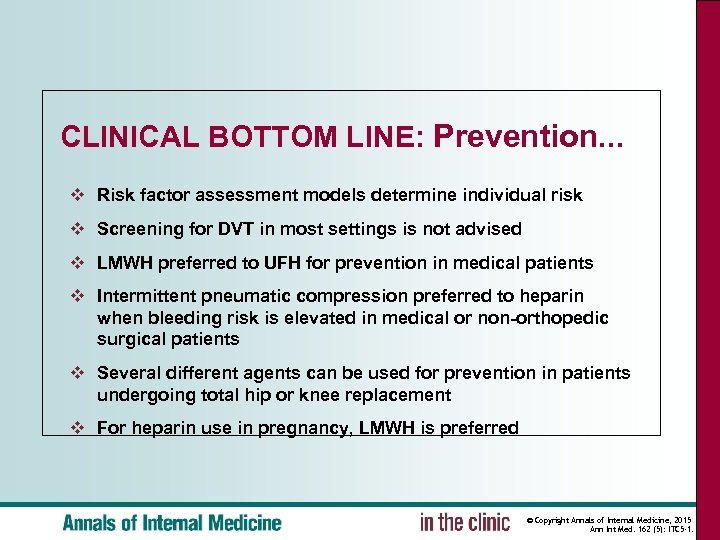

CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE: Prevention. . . ❖ Risk factor assessment models determine individual risk ❖ Screening for DVT in most settings is not advised ❖ LMWH preferred to UFH for prevention in medical patients ❖ Intermittent pneumatic compression preferred to heparin when bleeding risk is elevated in medical or non-orthopedic surgical patients ❖ Several different agents can be used for prevention in patients undergoing total hip or knee replacement ❖ For heparin use in pregnancy, LMWH is preferred © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

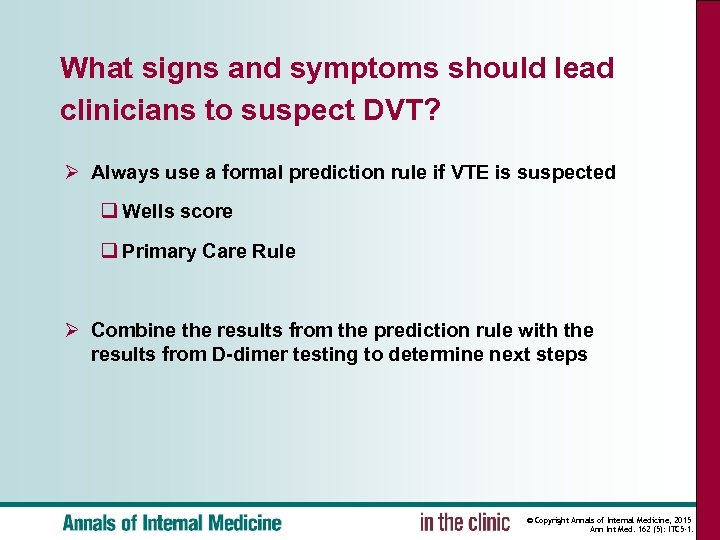

What signs and symptoms should lead clinicians to suspect DVT? Ø Always use a formal prediction rule if VTE is suspected q Wells score q Primary Care Rule Ø Combine the results from the prediction rule with the results from D-dimer testing to determine next steps © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

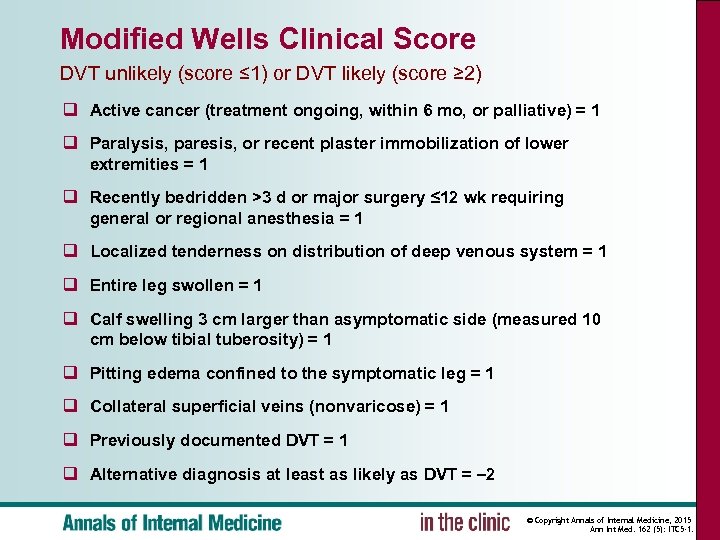

Modified Wells Clinical Score DVT unlikely (score ≤ 1) or DVT likely (score ≥ 2) q Active cancer (treatment ongoing, within 6 mo, or palliative) = 1 q Paralysis, paresis, or recent plaster immobilization of lower extremities = 1 q Recently bedridden >3 d or major surgery ≤ 12 wk requiring general or regional anesthesia = 1 q Localized tenderness on distribution of deep venous system = 1 q Entire leg swollen = 1 q Calf swelling 3 cm larger than asymptomatic side (measured 10 cm below tibial tuberosity) = 1 q Pitting edema confined to the symptomatic leg = 1 q Collateral superficial veins (nonvaricose) = 1 q Previously documented DVT = 1 q Alternative diagnosis at least as likely as DVT = – 2 © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

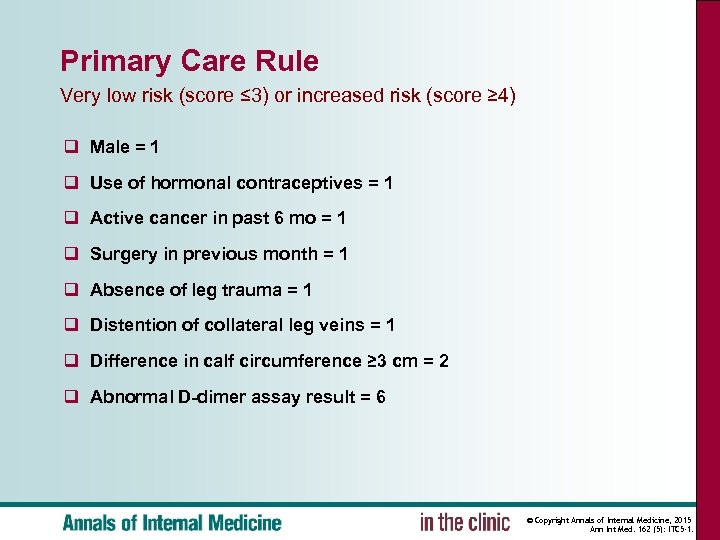

Primary Care Rule Very low risk (score ≤ 3) or increased risk (score ≥ 4) q Male = 1 q Use of hormonal contraceptives = 1 q Active cancer in past 6 mo = 1 q Surgery in previous month = 1 q Absence of leg trauma = 1 q Distention of collateral leg veins = 1 q Difference in calf circumference ≥ 3 cm = 2 q Abnormal D-dimer assay result = 6 © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

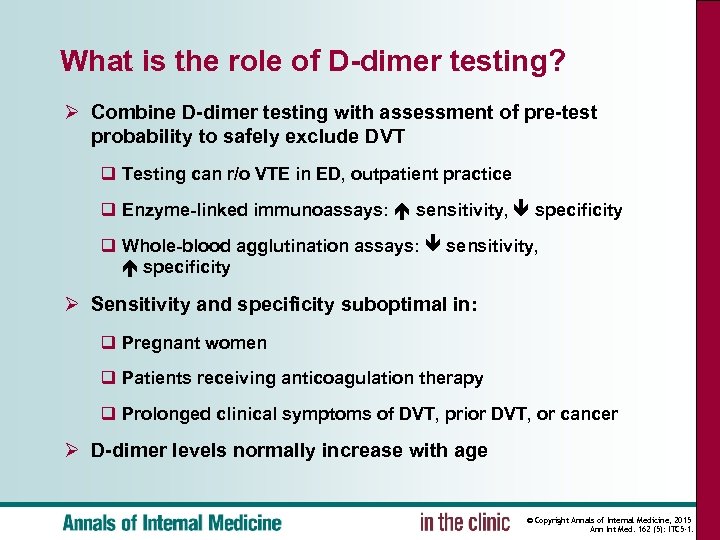

What is the role of D-dimer testing? Ø Combine D-dimer testing with assessment of pre-test probability to safely exclude DVT q Testing can r/o VTE in ED, outpatient practice q Enzyme-linked immunoassays: sensitivity, specificity q Whole-blood agglutination assays: sensitivity, specificity Ø Sensitivity and specificity suboptimal in: q Pregnant women q Patients receiving anticoagulation therapy q Prolonged clinical symptoms of DVT, prior DVT, or cancer Ø D-dimer levels normally increase with age © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

What is the role of venous ultrasonography? Ø Proximal ultrasonography q Examines only the common and popliteal veins Ø Whole-leg ultrasonography q Examines entire deep vein system, including calf veins q Avoids repeated testing q But may identify more patients with isolated, calf vein DVT Ø Both methods associated with acceptable 3 -month incidence of VTE after negative results © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

What is the role of other types of testing? Ø CT venography and MRI q Uncertain role in diagnosis q Not recommended as first-line diagnostic tests q Except in cases when ultrasonography cannot be performed (lower-extremity casting; severe edema) © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

How should a pregnant patient be evaluated for suspected DVT? Ø Compression ultrasound should be the initial test q Follow-up ultrasonography is recommended for patients with a normal result on initial testing Ø Thrombosis in the iliac veins q Suggestive symptoms include whole-leg edema or discomfort in the flank, back, or buttock q Evaluate pelvic vessels with ultrasonography and/or MRI Ø D-dimer assays have decreased specificity during pregnancy, but results become reliable by 3 rd trimester in most women © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

What other diagnoses should clinicians consider? Ø Venous insufficiency (venous reflux) Ø Superficial thrombophlebitis Ø Muscle strain, tear or trauma Ø Leg swelling in a paralyzed limb Ø Baker’s cyst Ø Cellulitis Ø Lymphedema © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

When should clinicians consider consulting a specialist? Ø Imaging is nondiagnostic Ø Recurrent DVT is suspected q Post-thrombotic syndrome occurs in 20%-50% of patients with symptomatic DVT, and differentiating post-thrombotic syndrome from recurrent DVT can be challenging q Criteria for diagnosing recurrent DVT are lacking, especially in venous segments with residual abnormalities q Suspicion for DVT should be high despite negative testing © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

What other underlying conditions and clinical manifestations should clinicians look for? Ø Cancer q 3. 5%-10% diagnosed with cancer within 12 months of VTE q Benefit of an extensive screening protocol has not been established q Tailor cancer screening to age, symptoms, risk factors Ø Recurrent VTE q There is no consensus on which, if any, patients should be tested for thrombophilia © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE: Diagnosis. . . ❖ To stratify a patient’s risk for thrombosis § Use a clinical prediction rule § Combine the results with a sensitive D-dimer assay § Whole-leg ultrasound may limit the need for repeat testing but will identify more patients with isolated calf vein thrombi ❖ In patients diagnosed with DVT § Extensive cancer screening strategy and thrombophilia testing is controversial ❖ Consult a specialist when § Recurrent VTE is possible § Imaging studies are nondiagnostic or negative, particularly if the suspicion for thrombosis is high © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

How should clinicians decide whether to treat patients on an oupatient or inpatient basis? Ø Most people with VTE can be safely treated as outpatients q With LMWH treatment q Outcome is better at home than in hospital Ø Consider admitting patients who have difficulty managing outpatient treatment © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

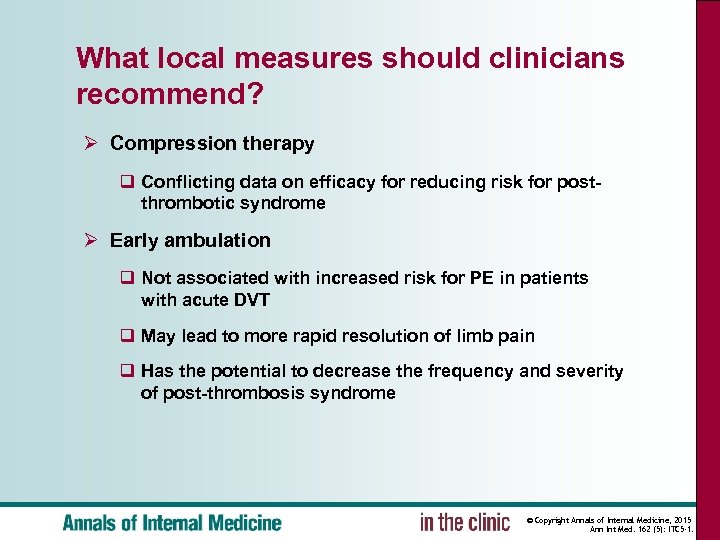

What local measures should clinicians recommend? Ø Compression therapy q Conflicting data on efficacy for reducing risk for postthrombotic syndrome Ø Early ambulation q Not associated with increased risk for PE in patients with acute DVT q May lead to more rapid resolution of limb pain q Has the potential to decrease the frequency and severity of post-thrombosis syndrome © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

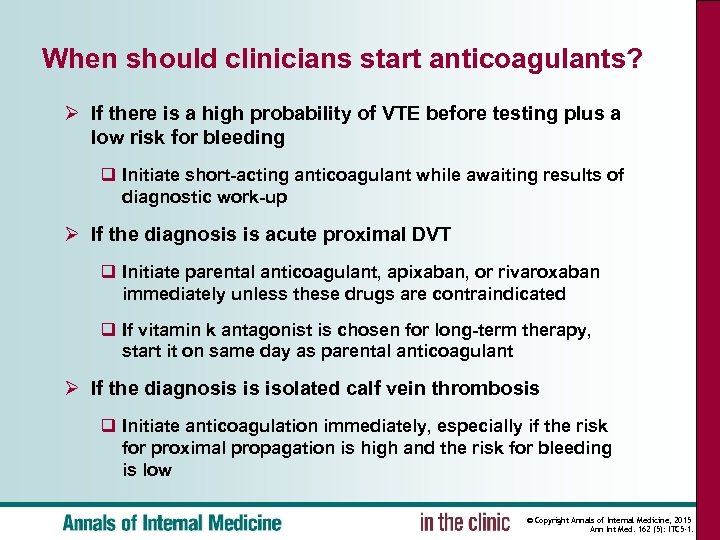

When should clinicians start anticoagulants? Ø If there is a high probability of VTE before testing plus a low risk for bleeding q Initiate short-acting anticoagulant while awaiting results of diagnostic work-up Ø If the diagnosis is acute proximal DVT q Initiate parental anticoagulant, apixaban, or rivaroxaban immediately unless these drugs are contraindicated q If vitamin k antagonist is chosen for long-term therapy, start it on same day as parental anticoagulant Ø If the diagnosis is isolated calf vein thrombosis q Initiate anticoagulation immediately, especially if the risk for proximal propagation is high and the risk for bleeding is low © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

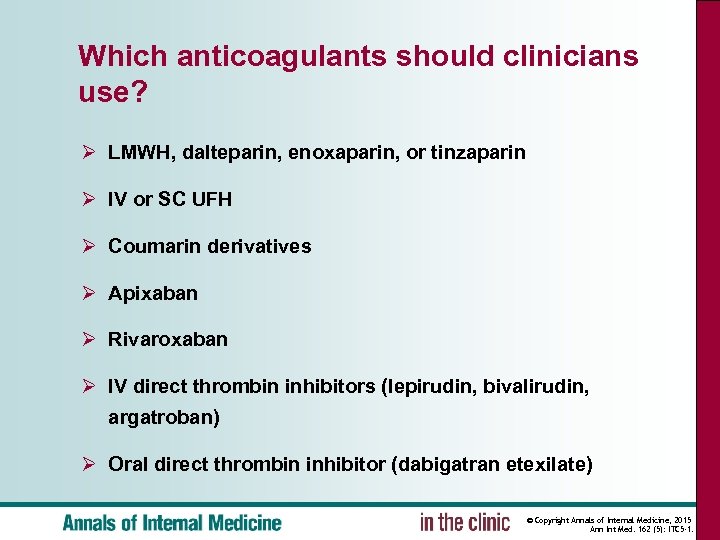

Which anticoagulants should clinicians use? Ø LMWH, dalteparin, enoxaparin, or tinzaparin Ø IV or SC UFH Ø Coumarin derivatives Ø Apixaban Ø Rivaroxaban Ø IV direct thrombin inhibitors (lepirudin, bivalirudin, argatroban) Ø Oral direct thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran etexilate) © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

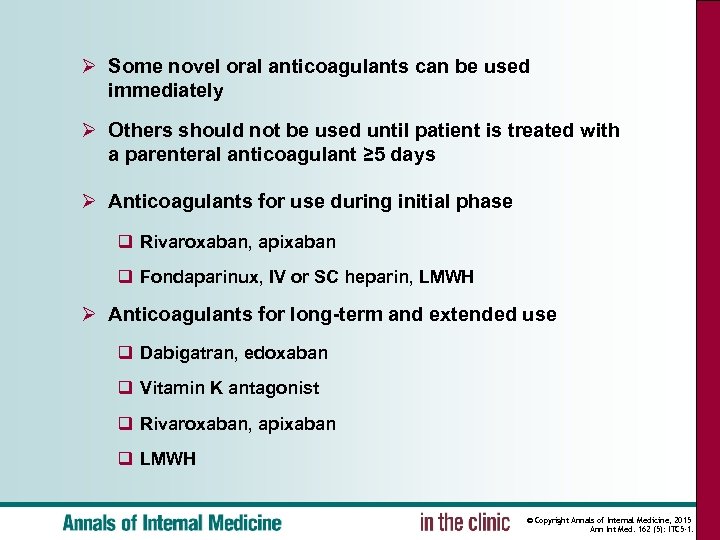

Ø Some novel oral anticoagulants can be used immediately Ø Others should not be used until patient is treated with a parenteral anticoagulant ≥ 5 days Ø Anticoagulants for use during initial phase q Rivaroxaban, apixaban q Fondaparinux, IV or SC heparin, LMWH Ø Anticoagulants for long-term and extended use q Dabigatran, edoxaban q Vitamin K antagonist q Rivaroxaban, apixaban q LMWH © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

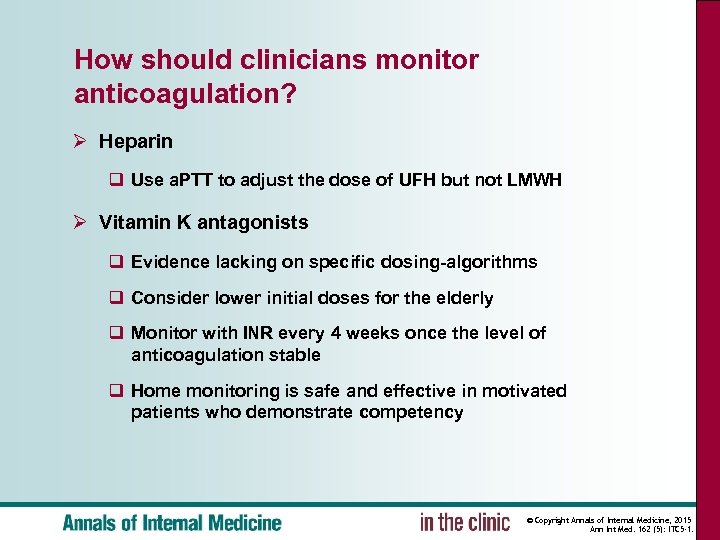

How should clinicians monitor anticoagulation? Ø Heparin q Use a. PTT to adjust the dose of UFH but not LMWH Ø Vitamin K antagonists q Evidence lacking on specific dosing-algorithms q Consider lower initial doses for the elderly q Monitor with INR every 4 weeks once the level of anticoagulation stable q Home monitoring is safe and effective in motivated patients who demonstrate competency © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

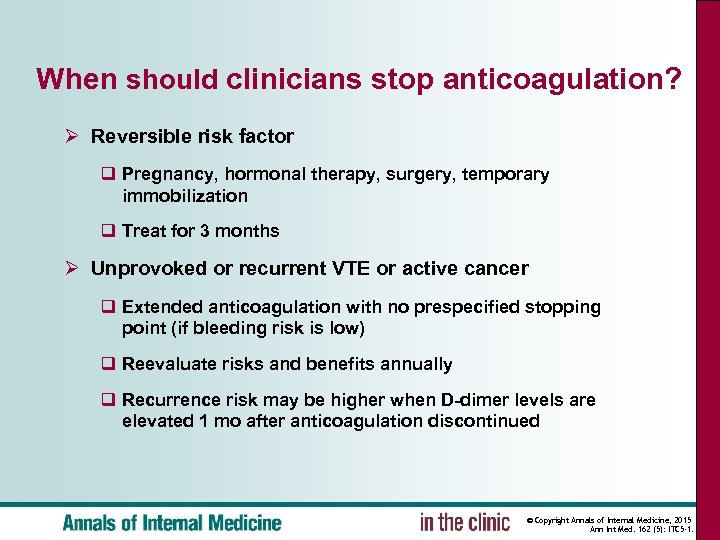

When should clinicians stop anticoagulation? Ø Reversible risk factor q Pregnancy, hormonal therapy, surgery, temporary immobilization q Treat for 3 months Ø Unprovoked or recurrent VTE or active cancer q Extended anticoagulation with no prespecified stopping point (if bleeding risk is low) q Reevaluate risks and benefits annually q Recurrence risk may be higher when D-dimer levels are elevated 1 mo after anticoagulation discontinued © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

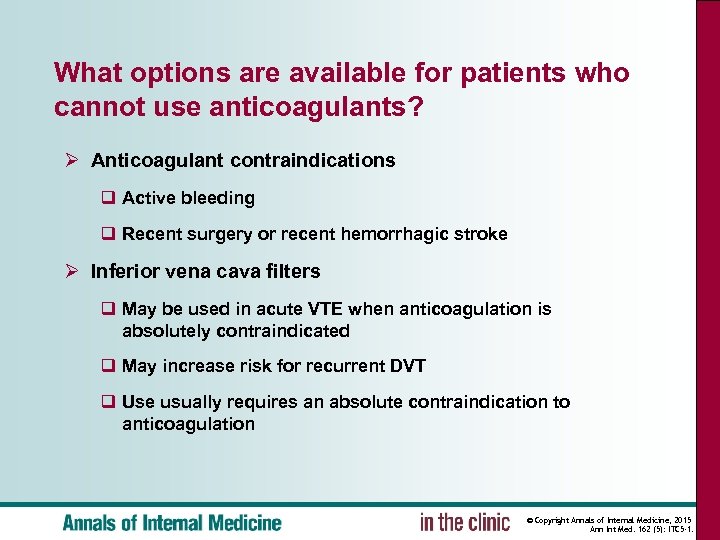

What options are available for patients who cannot use anticoagulants? Ø Anticoagulant contraindications q Active bleeding q Recent surgery or recent hemorrhagic stroke Ø Inferior vena cava filters q May be used in acute VTE when anticoagulation is absolutely contraindicated q May increase risk for recurrent DVT q Use usually requires an absolute contraindication to anticoagulation © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

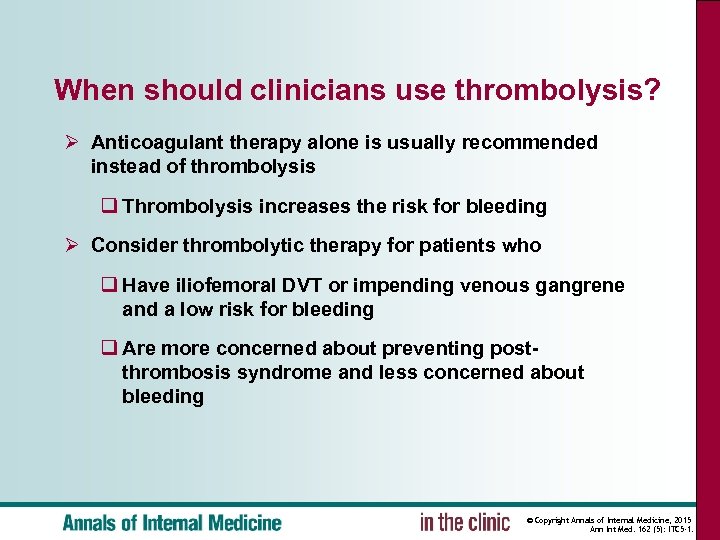

When should clinicians use thrombolysis? Ø Anticoagulant therapy alone is usually recommended instead of thrombolysis q Thrombolysis increases the risk for bleeding Ø Consider thrombolytic therapy for patients who q Have iliofemoral DVT or impending venous gangrene and a low risk for bleeding q Are more concerned about preventing postthrombosis syndrome and less concerned about bleeding © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

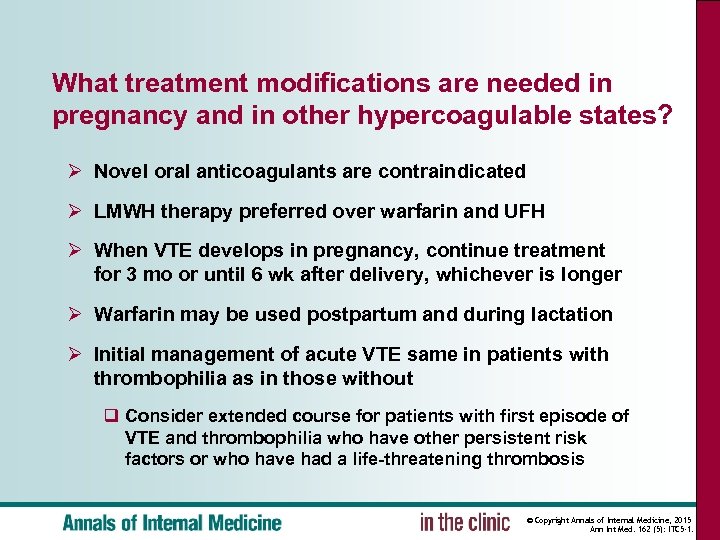

What treatment modifications are needed in pregnancy and in other hypercoagulable states? Ø Novel oral anticoagulants are contraindicated Ø LMWH therapy preferred over warfarin and UFH Ø When VTE develops in pregnancy, continue treatment for 3 mo or until 6 wk after delivery, whichever is longer Ø Warfarin may be used postpartum and during lactation Ø Initial management of acute VTE same in patients with thrombophilia as in those without q Consider extended course for patients with first episode of VTE and thrombophilia who have other persistent risk factors or who have had a life-threatening thrombosis © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

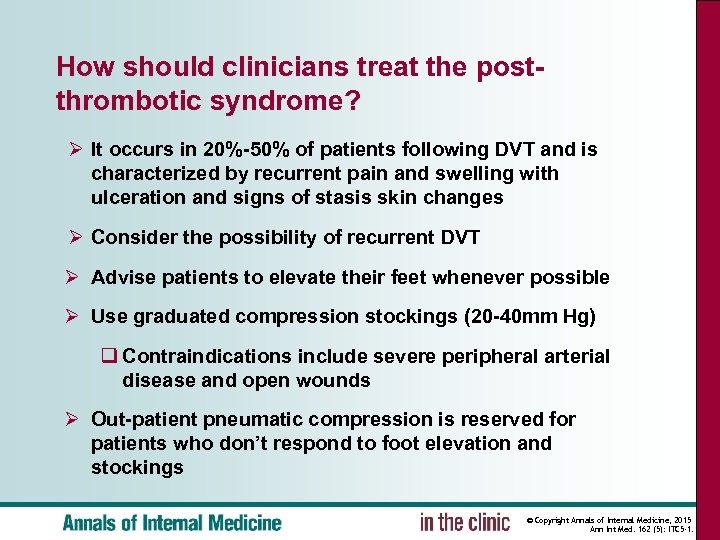

How should clinicians treat the postthrombotic syndrome? Ø It occurs in 20%-50% of patients following DVT and is characterized by recurrent pain and swelling with ulceration and signs of stasis skin changes Ø Consider the possibility of recurrent DVT Ø Advise patients to elevate their feet whenever possible Ø Use graduated compression stockings (20 -40 mm Hg) q Contraindications include severe peripheral arterial disease and open wounds Ø Out-patient pneumatic compression is reserved for patients who don’t respond to foot elevation and stockings © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

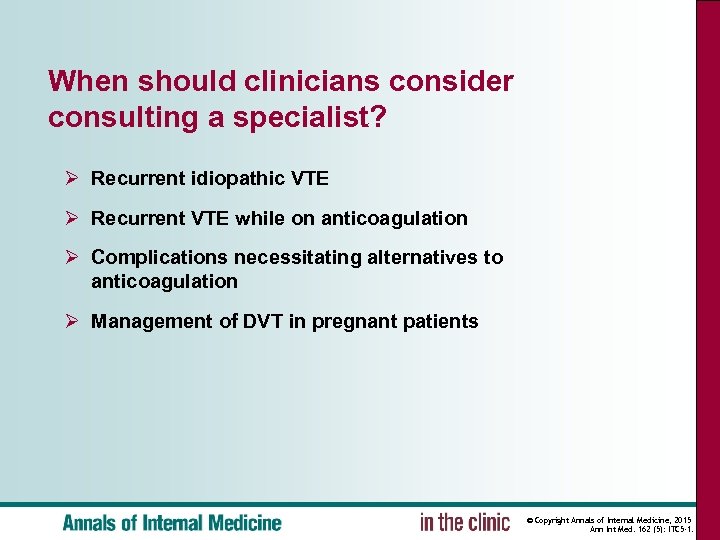

When should clinicians consider consulting a specialist? Ø Recurrent idiopathic VTE Ø Recurrent VTE while on anticoagulation Ø Complications necessitating alternatives to anticoagulation Ø Management of DVT in pregnant patients © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

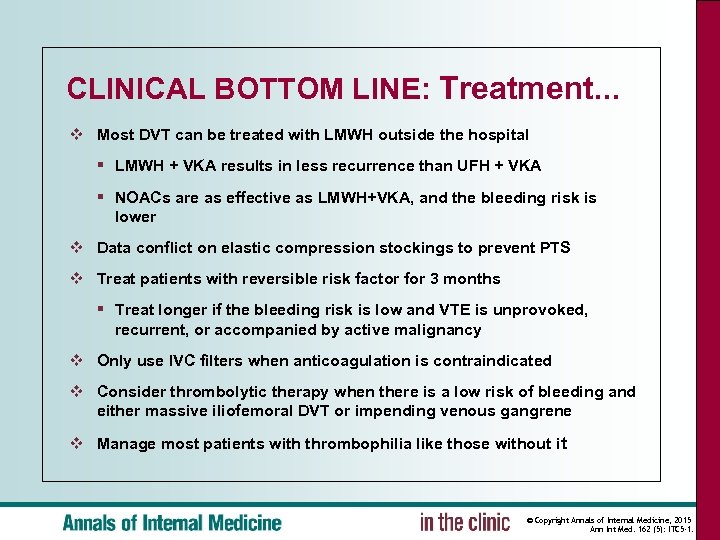

CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE: Treatment. . . ❖ Most DVT can be treated with LMWH outside the hospital § LMWH + VKA results in less recurrence than UFH + VKA § NOACs are as effective as LMWH+VKA, and the bleeding risk is lower ❖ Data conflict on elastic compression stockings to prevent PTS ❖ Treat patients with reversible risk factor for 3 months § Treat longer if the bleeding risk is low and VTE is unprovoked, recurrent, or accompanied by active malignancy ❖ Only use IVC filters when anticoagulation is contraindicated ❖ Consider thrombolytic therapy when there is a low risk of bleeding and either massive iliofemoral DVT or impending venous gangrene ❖ Manage most patients with thrombophilia like those without it © Copyright Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015 Ann Int Med. 162 (5): ITC 5 -1.

47c6aed6f81d6410a2247a42a15b2bc7.ppt