853b5347a9af528f1c084694aea08fd2.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 42

Evaluation of hydroacoustics for monitoring suspended-sediment transport in rivers Scott Wright (CA WSC) and David Topping (GCMRC) Special acknowledgement to Cory Williams (CO WSC) and Molly Wood (ID WSC) for data and assistance OSW Webinars, 29 -Sep-09, 2 -Oct-09 U. S. Department of the Interior U. S. Geological Survey

Evaluation of hydroacoustics for monitoring suspended-sediment transport in rivers Scott Wright (CA WSC) and David Topping (GCMRC) Special acknowledgement to Cory Williams (CO WSC) and Molly Wood (ID WSC) for data and assistance OSW Webinars, 29 -Sep-09, 2 -Oct-09 U. S. Department of the Interior U. S. Geological Survey

Outline Ø Brief background on the project Ø Basic theory and approach (single frequency) – Colorado River Ø Applications on other rivers - Gunnison, Clearwater Ø Analysis of historical sediment data using acoustics theory Ø Summary, limitations, publications, FAQs, future work

Outline Ø Brief background on the project Ø Basic theory and approach (single frequency) – Colorado River Ø Applications on other rivers - Gunnison, Clearwater Ø Analysis of historical sediment data using acoustics theory Ø Summary, limitations, publications, FAQs, future work

Project background Ø “Exploratory” deployments of side-looking ADCPs along the Colorado River in Grand Canyon in 2002, by Ted Melis and David Topping, yielded some interesting results and “new” methods Nortek EZQ Ø Given the increasing popularity of side-lookers at gaging stations and the potential to monitor sediment flux (i. e. discharge and concentration) with a single instrument, it was desired to evaluate these new methods in a broader context Ø We submitted a proposal to FISP/OSW to do this, and received funding in FYs 2008 and 2009 Ø The main goal of the project is to develop a “manual” for using hydroacoustics to monitor suspended-sediment transport, drawing from our experience on the Colorado, from other available datasets, and from acoustics theory and historical sediment data

Project background Ø “Exploratory” deployments of side-looking ADCPs along the Colorado River in Grand Canyon in 2002, by Ted Melis and David Topping, yielded some interesting results and “new” methods Nortek EZQ Ø Given the increasing popularity of side-lookers at gaging stations and the potential to monitor sediment flux (i. e. discharge and concentration) with a single instrument, it was desired to evaluate these new methods in a broader context Ø We submitted a proposal to FISP/OSW to do this, and received funding in FYs 2008 and 2009 Ø The main goal of the project is to develop a “manual” for using hydroacoustics to monitor suspended-sediment transport, drawing from our experience on the Colorado, from other available datasets, and from acoustics theory and historical sediment data

Basic theory and approach Transducer emits sound waves and records what comes back (i. e. listens to the echo); profilers use “range-gating” to bin the data (e. g. velocity profiles) The amount of sound returned to the transducer (backscatter) depends on: - The concentration, size, shape, and density of the stuff suspended in the beam path (i. e. “targets” or “scatterers”) - The distance from the transducer, because there are “transmission” losses along the beam (beam spreading, absorption) Once corrected for transmission losses, standard theory suggests that: a ~ 0. 1 b is an instrument-specific constant Lots and lots of literature on this approach for uniform, sand-sized particles, developed primarily for coastal applications

Basic theory and approach Transducer emits sound waves and records what comes back (i. e. listens to the echo); profilers use “range-gating” to bin the data (e. g. velocity profiles) The amount of sound returned to the transducer (backscatter) depends on: - The concentration, size, shape, and density of the stuff suspended in the beam path (i. e. “targets” or “scatterers”) - The distance from the transducer, because there are “transmission” losses along the beam (beam spreading, absorption) Once corrected for transmission losses, standard theory suggests that: a ~ 0. 1 b is an instrument-specific constant Lots and lots of literature on this approach for uniform, sand-sized particles, developed primarily for coastal applications

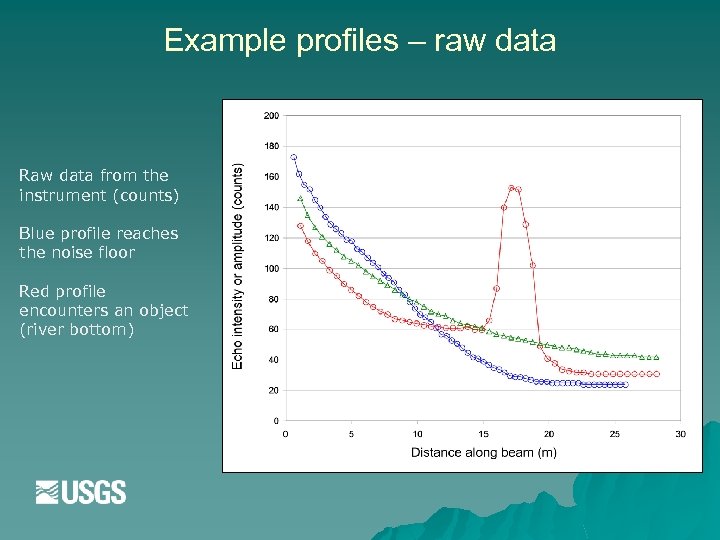

Example profiles – raw data Raw data from the instrument (counts) Blue profile reaches the noise floor Red profile encounters an object (river bottom)

Example profiles – raw data Raw data from the instrument (counts) Blue profile reaches the noise floor Red profile encounters an object (river bottom)

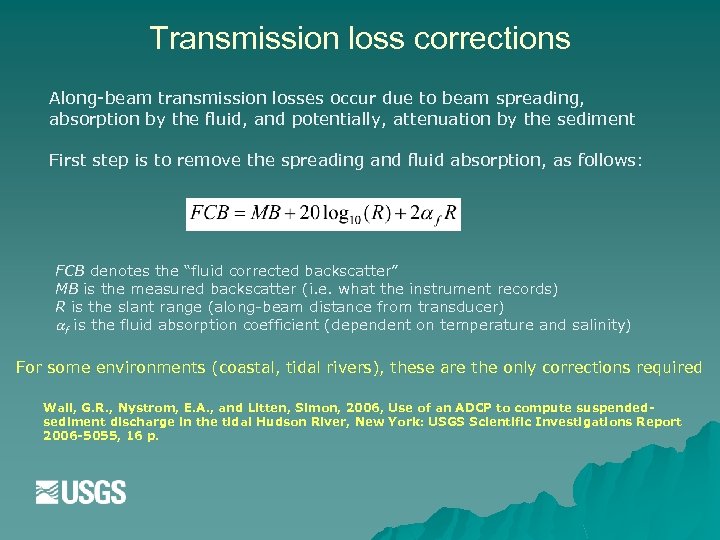

Transmission loss corrections Along-beam transmission losses occur due to beam spreading, absorption by the fluid, and potentially, attenuation by the sediment First step is to remove the spreading and fluid absorption, as follows: FCB denotes the “fluid corrected backscatter” MB is the measured backscatter (i. e. what the instrument records) R is the slant range (along-beam distance from transducer) f is the fluid absorption coefficient (dependent on temperature and salinity) For some environments (coastal, tidal rivers), these are the only corrections required Wall, G. R. , Nystrom, E. A. , and Litten, Simon, 2006, Use of an ADCP to compute suspendedsediment discharge in the tidal Hudson River, New York: USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2006 -5055, 16 p.

Transmission loss corrections Along-beam transmission losses occur due to beam spreading, absorption by the fluid, and potentially, attenuation by the sediment First step is to remove the spreading and fluid absorption, as follows: FCB denotes the “fluid corrected backscatter” MB is the measured backscatter (i. e. what the instrument records) R is the slant range (along-beam distance from transducer) f is the fluid absorption coefficient (dependent on temperature and salinity) For some environments (coastal, tidal rivers), these are the only corrections required Wall, G. R. , Nystrom, E. A. , and Litten, Simon, 2006, Use of an ADCP to compute suspendedsediment discharge in the tidal Hudson River, New York: USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2006 -5055, 16 p.

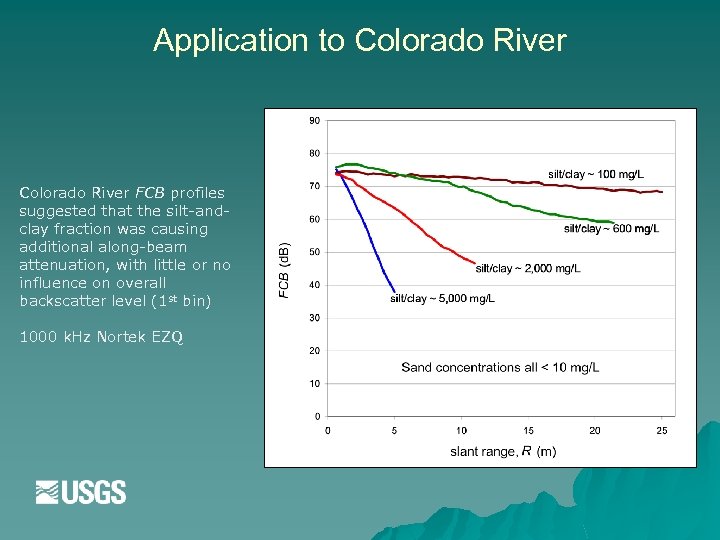

Application to Colorado River FCB profiles suggested that the silt-andclay fraction was causing additional along-beam attenuation, with little or no influence on overall backscatter level (1 st bin) 1000 k. Hz Nortek EZQ

Application to Colorado River FCB profiles suggested that the silt-andclay fraction was causing additional along-beam attenuation, with little or no influence on overall backscatter level (1 st bin) 1000 k. Hz Nortek EZQ

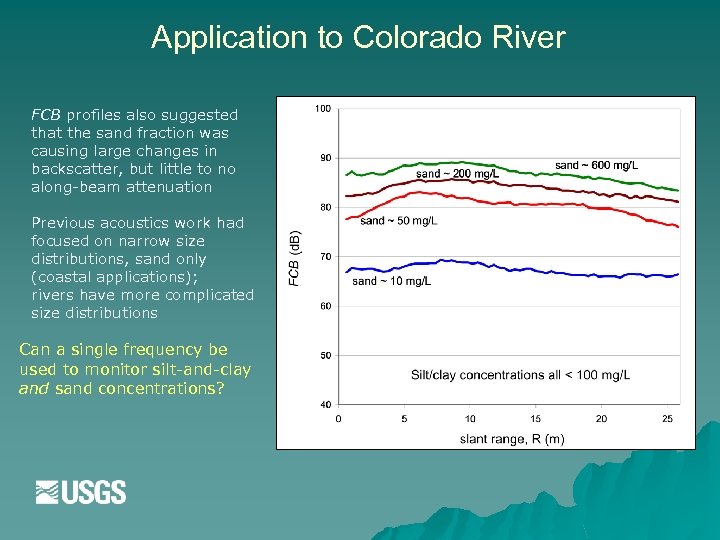

Application to Colorado River FCB profiles also suggested that the sand fraction was causing large changes in backscatter, but little to no along-beam attenuation Previous acoustics work had focused on narrow size distributions, sand only (coastal applications); rivers have more complicated size distributions Can a single frequency be used to monitor silt-and-clay and sand concentrations?

Application to Colorado River FCB profiles also suggested that the sand fraction was causing large changes in backscatter, but little to no along-beam attenuation Previous acoustics work had focused on narrow size distributions, sand only (coastal applications); rivers have more complicated size distributions Can a single frequency be used to monitor silt-and-clay and sand concentrations?

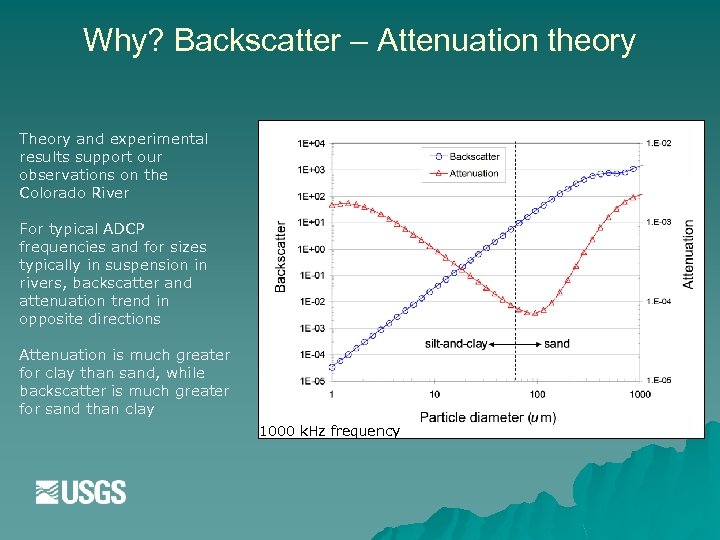

Why? Backscatter – Attenuation theory Theory and experimental results support our observations on the Colorado River For typical ADCP frequencies and for sizes typically in suspension in rivers, backscatter and attenuation trend in opposite directions Attenuation is much greater for clay than sand, while backscatter is much greater for sand than clay 1000 k. Hz frequency

Why? Backscatter – Attenuation theory Theory and experimental results support our observations on the Colorado River For typical ADCP frequencies and for sizes typically in suspension in rivers, backscatter and attenuation trend in opposite directions Attenuation is much greater for clay than sand, while backscatter is much greater for sand than clay 1000 k. Hz frequency

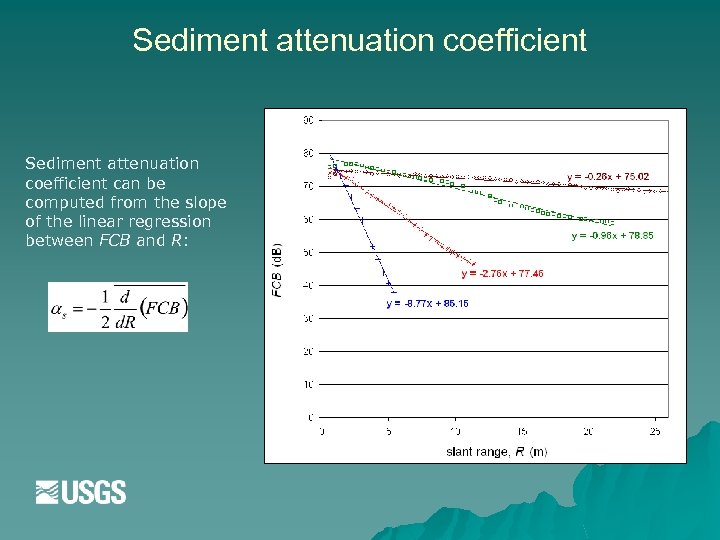

Sediment attenuation coefficient can be computed from the slope of the linear regression between FCB and R:

Sediment attenuation coefficient can be computed from the slope of the linear regression between FCB and R:

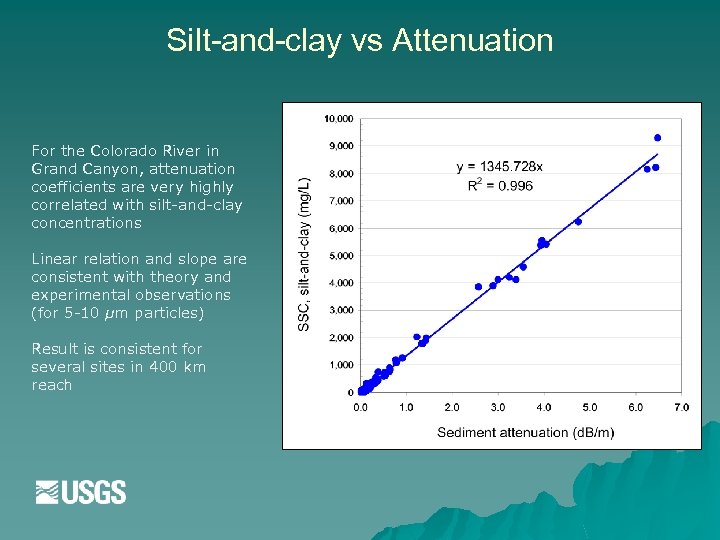

Silt-and-clay vs Attenuation For the Colorado River in Grand Canyon, attenuation coefficients are very highly correlated with silt-and-clay concentrations Linear relation and slope are consistent with theory and experimental observations (for 5 -10 µm particles) Result is consistent for several sites in 400 km reach

Silt-and-clay vs Attenuation For the Colorado River in Grand Canyon, attenuation coefficients are very highly correlated with silt-and-clay concentrations Linear relation and slope are consistent with theory and experimental observations (for 5 -10 µm particles) Result is consistent for several sites in 400 km reach

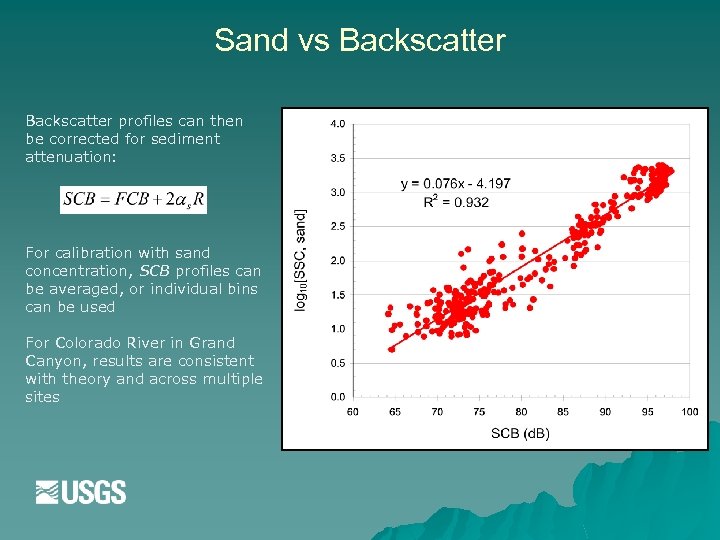

Sand vs Backscatter profiles can then be corrected for sediment attenuation: For calibration with sand concentration, SCB profiles can be averaged, or individual bins can be used For Colorado River in Grand Canyon, results are consistent with theory and across multiple sites

Sand vs Backscatter profiles can then be corrected for sediment attenuation: For calibration with sand concentration, SCB profiles can be averaged, or individual bins can be used For Colorado River in Grand Canyon, results are consistent with theory and across multiple sites

Methods summary 1. Correct measured backscatter profiles for beam spreading and fluid absorption (FCB); remove data below noise floor 2. Apply linear regression to FCB profiles to compute sediment attenuation coefficients (is sediment attenuation important for your site? ) 3. Calibrate sediment attenuation coefficients to silt-and-clay concentrations – should be roughly linear 4. Further correct backscatter profiles for sediment attenuation (SCB) 5. Calibrate backscatter level (average over the range or use individual bins) to sand concentration – roughly log-linear with slope ~0. 1 Methods were developed using data from the Colorado River in Grand Canyon. How general are they?

Methods summary 1. Correct measured backscatter profiles for beam spreading and fluid absorption (FCB); remove data below noise floor 2. Apply linear regression to FCB profiles to compute sediment attenuation coefficients (is sediment attenuation important for your site? ) 3. Calibrate sediment attenuation coefficients to silt-and-clay concentrations – should be roughly linear 4. Further correct backscatter profiles for sediment attenuation (SCB) 5. Calibrate backscatter level (average over the range or use individual bins) to sand concentration – roughly log-linear with slope ~0. 1 Methods were developed using data from the Colorado River in Grand Canyon. How general are they?

Outline Ø Brief background on the project Ø Basic theory and approach (single frequency) – Colorado River Ø Applications on other rivers - Gunnison, Clearwater Ø Analysis of historical sediment data using acoustics theory Ø Summary, limitations, publications, FAQs, future work

Outline Ø Brief background on the project Ø Basic theory and approach (single frequency) – Colorado River Ø Applications on other rivers - Gunnison, Clearwater Ø Analysis of historical sediment data using acoustics theory Ø Summary, limitations, publications, FAQs, future work

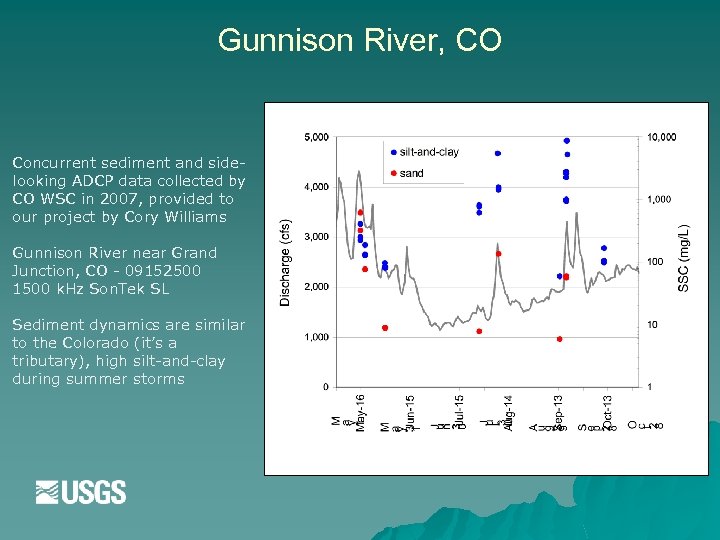

Gunnison River, CO Concurrent sediment and sidelooking ADCP data collected by CO WSC in 2007, provided to our project by Cory Williams Gunnison River near Grand Junction, CO - 09152500 1500 k. Hz Son. Tek SL Sediment dynamics are similar to the Colorado (it’s a tributary), high silt-and-clay during summer storms

Gunnison River, CO Concurrent sediment and sidelooking ADCP data collected by CO WSC in 2007, provided to our project by Cory Williams Gunnison River near Grand Junction, CO - 09152500 1500 k. Hz Son. Tek SL Sediment dynamics are similar to the Colorado (it’s a tributary), high silt-and-clay during summer storms

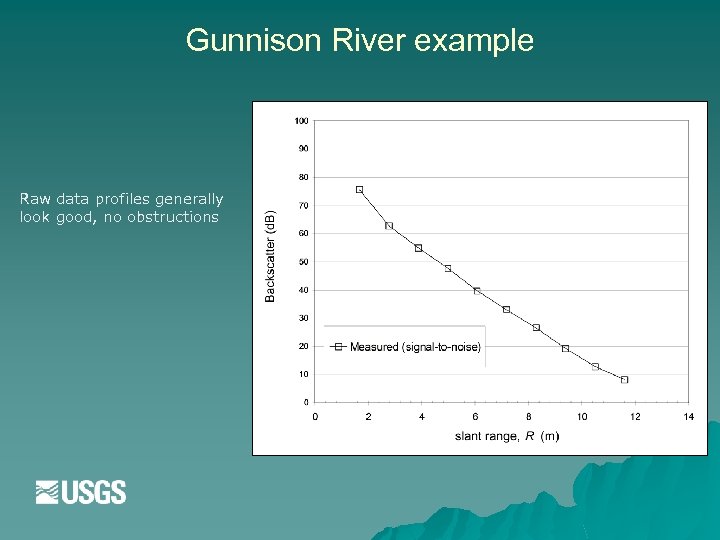

Gunnison River example Raw data profiles generally look good, no obstructions

Gunnison River example Raw data profiles generally look good, no obstructions

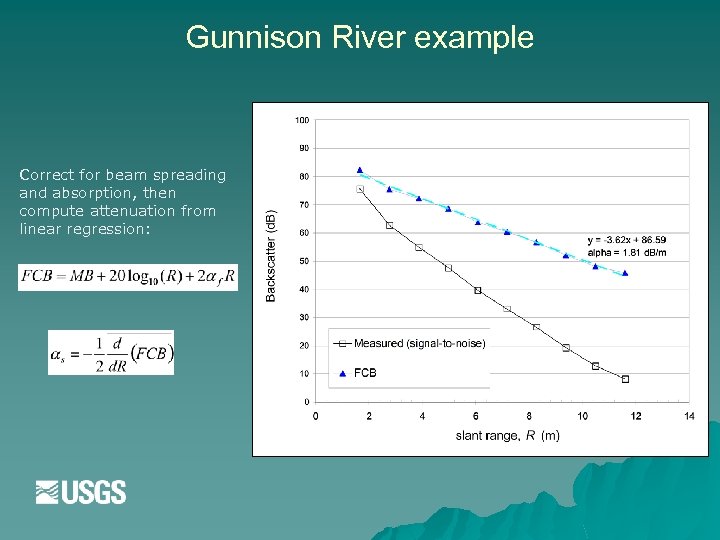

Gunnison River example Correct for beam spreading and absorption, then compute attenuation from linear regression:

Gunnison River example Correct for beam spreading and absorption, then compute attenuation from linear regression:

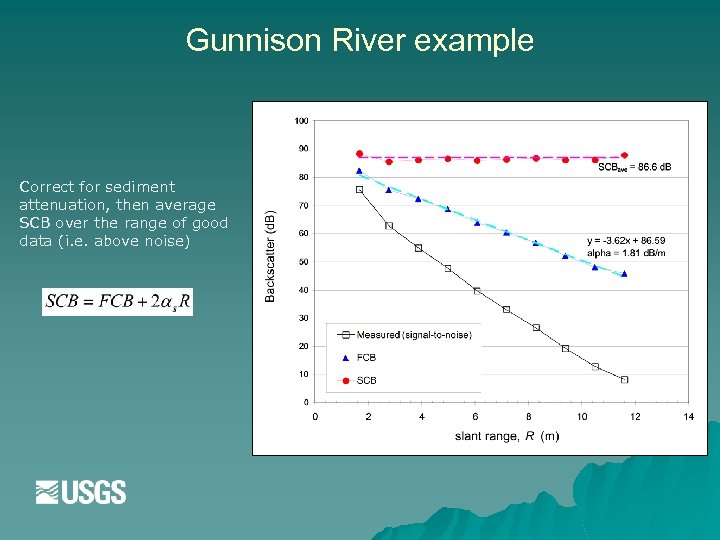

Gunnison River example Correct for sediment attenuation, then average SCB over the range of good data (i. e. above noise)

Gunnison River example Correct for sediment attenuation, then average SCB over the range of good data (i. e. above noise)

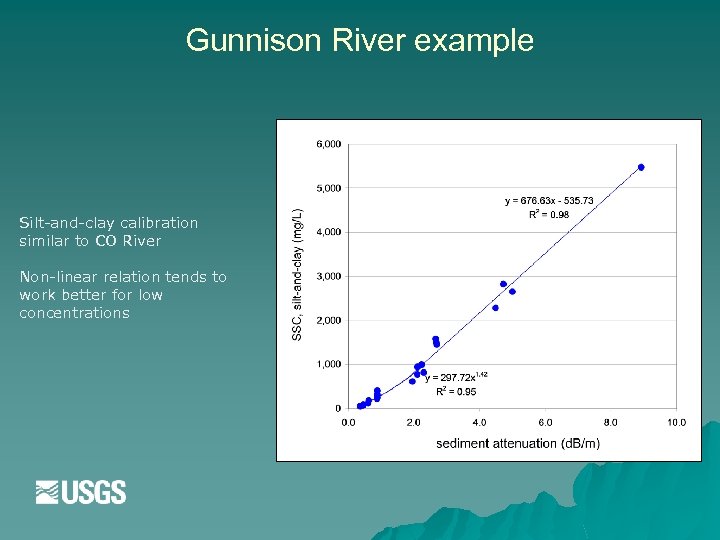

Gunnison River example Silt-and-clay calibration similar to CO River Non-linear relation tends to work better for low concentrations

Gunnison River example Silt-and-clay calibration similar to CO River Non-linear relation tends to work better for low concentrations

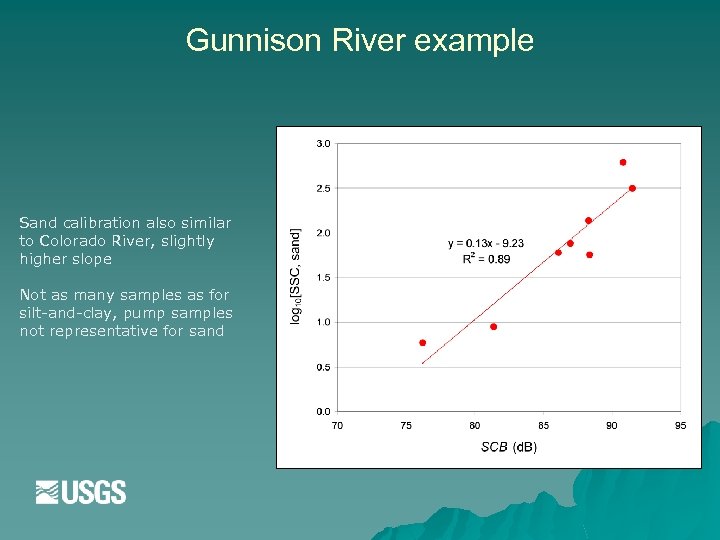

Gunnison River example Sand calibration also similar to Colorado River, slightly higher slope Not as many samples as for silt-and-clay, pump samples not representative for sand

Gunnison River example Sand calibration also similar to Colorado River, slightly higher slope Not as many samples as for silt-and-clay, pump samples not representative for sand

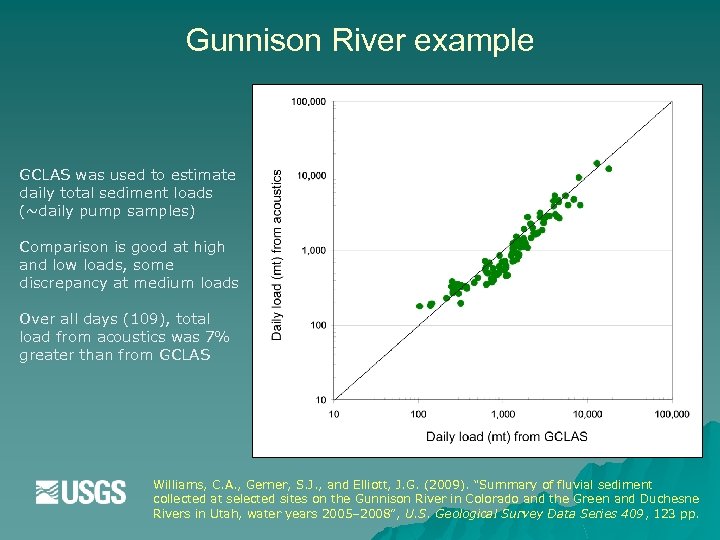

Gunnison River example GCLAS was used to estimate daily total sediment loads (~daily pump samples) Comparison is good at high and low loads, some discrepancy at medium loads Over all days (109), total load from acoustics was 7% greater than from GCLAS Williams, C. A. , Gerner, S. J. , and Elliott, J. G. (2009). “Summary of fluvial sediment collected at selected sites on the Gunnison River in Colorado and the Green and Duchesne Rivers in Utah, water years 2005– 2008”, U. S. Geological Survey Data Series 409, 123 pp.

Gunnison River example GCLAS was used to estimate daily total sediment loads (~daily pump samples) Comparison is good at high and low loads, some discrepancy at medium loads Over all days (109), total load from acoustics was 7% greater than from GCLAS Williams, C. A. , Gerner, S. J. , and Elliott, J. G. (2009). “Summary of fluvial sediment collected at selected sites on the Gunnison River in Colorado and the Green and Duchesne Rivers in Utah, water years 2005– 2008”, U. S. Geological Survey Data Series 409, 123 pp.

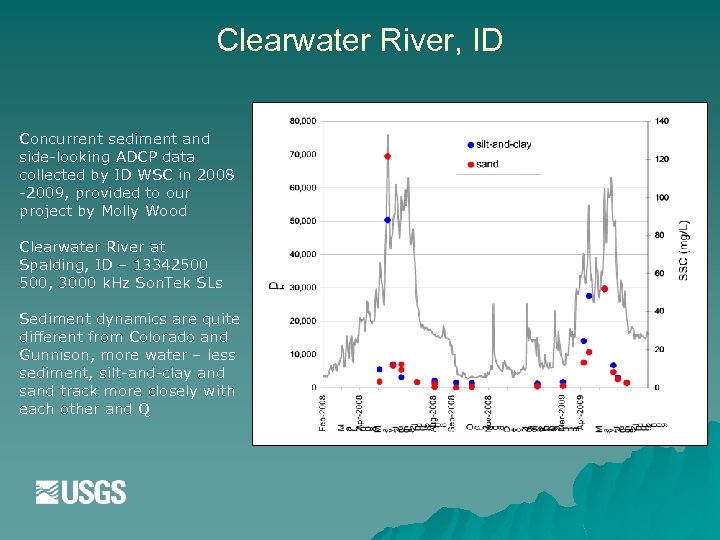

Clearwater River, ID Concurrent sediment and side-looking ADCP data collected by ID WSC in 2008 -2009, provided to our project by Molly Wood Clearwater River at Spalding, ID – 13342500 500, 3000 k. Hz Son. Tek SLs Sediment dynamics are quite different from Colorado and Gunnison, more water – less sediment, silt-and-clay and sand track more closely with each other and Q

Clearwater River, ID Concurrent sediment and side-looking ADCP data collected by ID WSC in 2008 -2009, provided to our project by Molly Wood Clearwater River at Spalding, ID – 13342500 500, 3000 k. Hz Son. Tek SLs Sediment dynamics are quite different from Colorado and Gunnison, more water – less sediment, silt-and-clay and sand track more closely with each other and Q

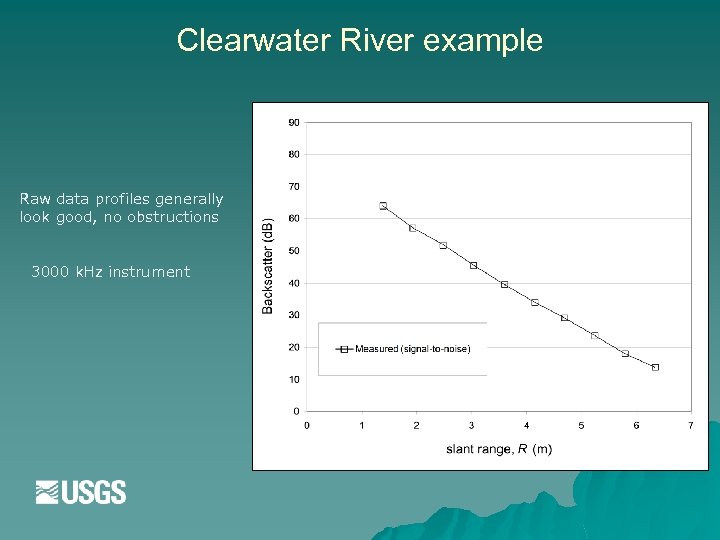

Clearwater River example Raw data profiles generally look good, no obstructions 3000 k. Hz instrument

Clearwater River example Raw data profiles generally look good, no obstructions 3000 k. Hz instrument

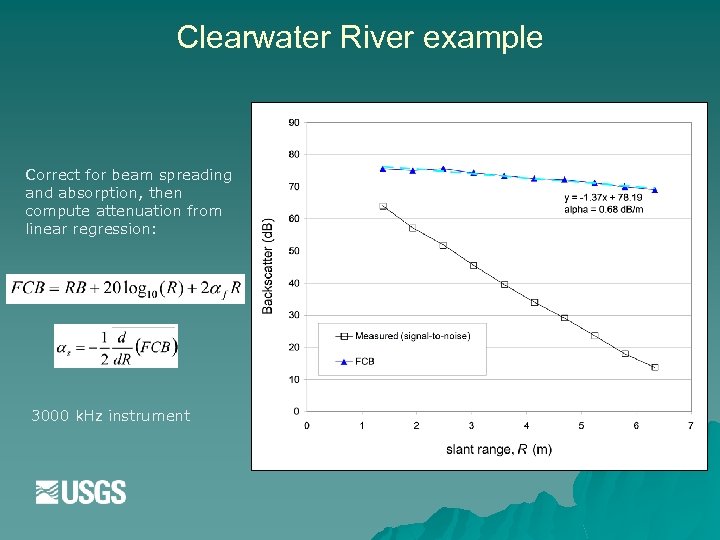

Clearwater River example Correct for beam spreading and absorption, then compute attenuation from linear regression: 3000 k. Hz instrument

Clearwater River example Correct for beam spreading and absorption, then compute attenuation from linear regression: 3000 k. Hz instrument

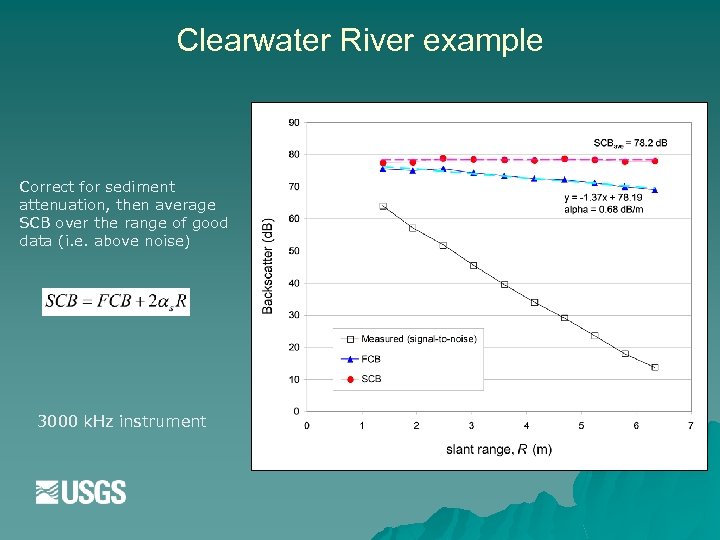

Clearwater River example Correct for sediment attenuation, then average SCB over the range of good data (i. e. above noise) 3000 k. Hz instrument

Clearwater River example Correct for sediment attenuation, then average SCB over the range of good data (i. e. above noise) 3000 k. Hz instrument

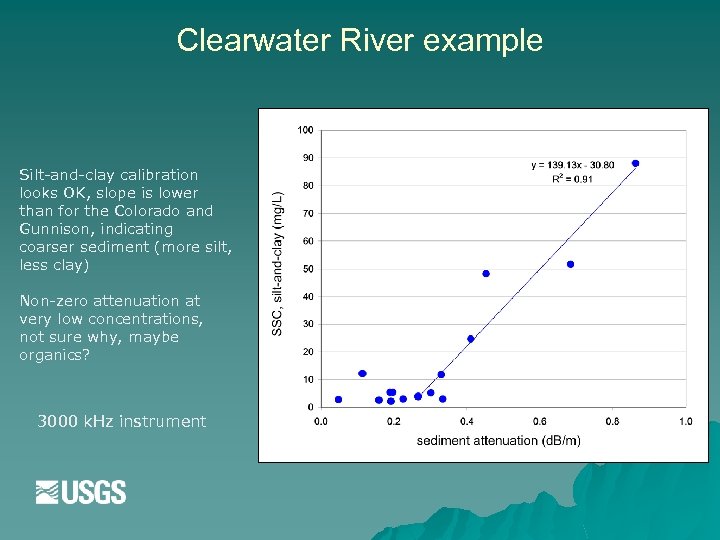

Clearwater River example Silt-and-clay calibration looks OK, slope is lower than for the Colorado and Gunnison, indicating coarser sediment (more silt, less clay) Non-zero attenuation at very low concentrations, not sure why, maybe organics? 3000 k. Hz instrument

Clearwater River example Silt-and-clay calibration looks OK, slope is lower than for the Colorado and Gunnison, indicating coarser sediment (more silt, less clay) Non-zero attenuation at very low concentrations, not sure why, maybe organics? 3000 k. Hz instrument

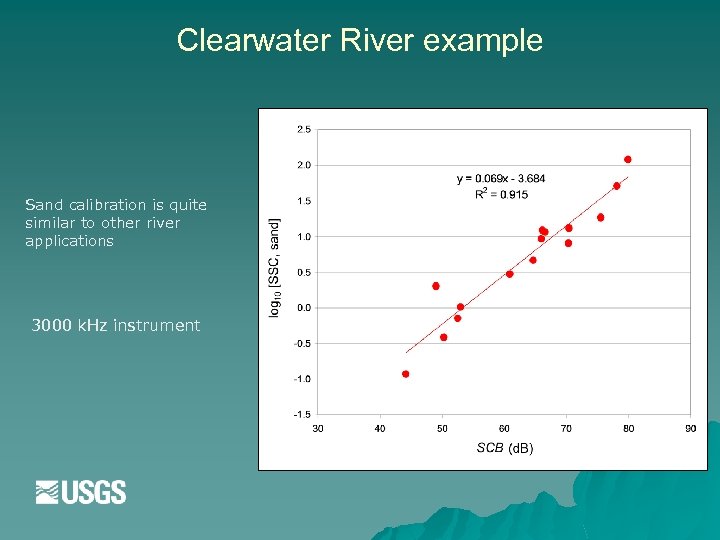

Clearwater River example Sand calibration is quite similar to other river applications 3000 k. Hz instrument

Clearwater River example Sand calibration is quite similar to other river applications 3000 k. Hz instrument

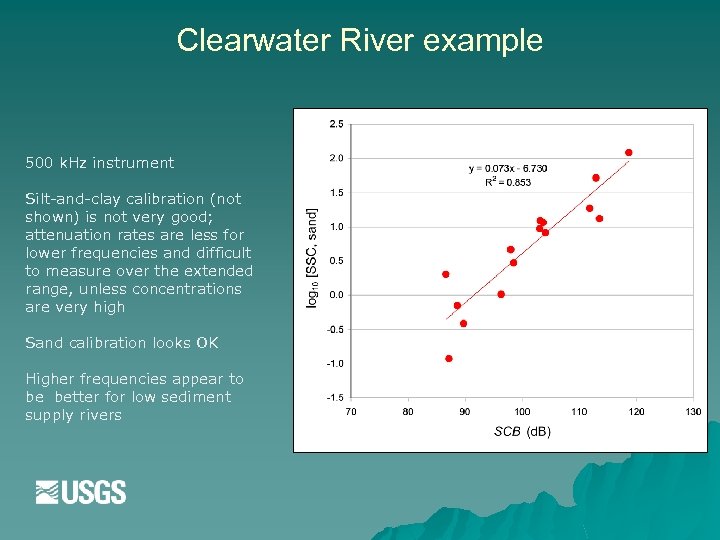

Clearwater River example 500 k. Hz instrument Silt-and-clay calibration (not shown) is not very good; attenuation rates are less for lower frequencies and difficult to measure over the extended range, unless concentrations are very high Sand calibration looks OK Higher frequencies appear to be better for low sediment supply rivers

Clearwater River example 500 k. Hz instrument Silt-and-clay calibration (not shown) is not very good; attenuation rates are less for lower frequencies and difficult to measure over the extended range, unless concentrations are very high Sand calibration looks OK Higher frequencies appear to be better for low sediment supply rivers

Outline Ø Brief background on the project Ø Basic theory and approach (single frequency) – Colorado River Ø Applications on other rivers - Gunnison, Clearwater Ø Analysis of historical sediment data using acoustics theory Ø Summary, limitations, publications, FAQs, future work

Outline Ø Brief background on the project Ø Basic theory and approach (single frequency) – Colorado River Ø Applications on other rivers - Gunnison, Clearwater Ø Analysis of historical sediment data using acoustics theory Ø Summary, limitations, publications, FAQs, future work

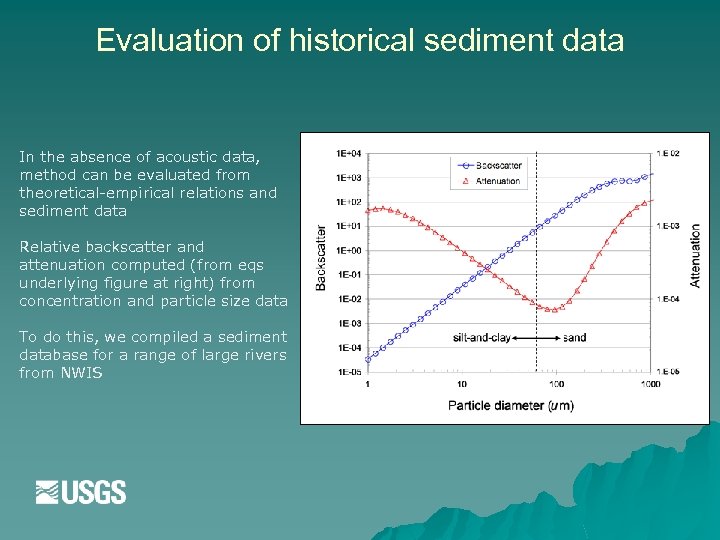

Evaluation of historical sediment data In the absence of acoustic data, method can be evaluated from theoretical-empirical relations and sediment data Relative backscatter and attenuation computed (from eqs underlying figure at right) from concentration and particle size data To do this, we compiled a sediment database for a range of large rivers from NWIS

Evaluation of historical sediment data In the absence of acoustic data, method can be evaluated from theoretical-empirical relations and sediment data Relative backscatter and attenuation computed (from eqs underlying figure at right) from concentration and particle size data To do this, we compiled a sediment database for a range of large rivers from NWIS

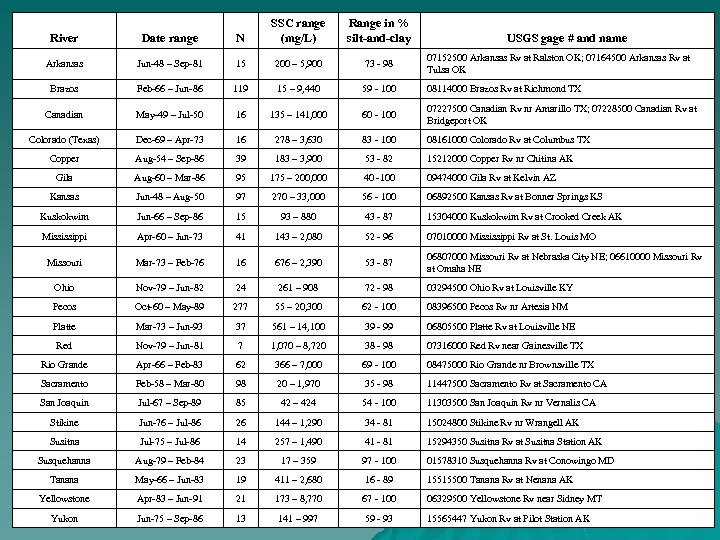

River Date range N SSC range (mg/L) Range in % silt-and-clay Arkansas Jun-48 – Sep-81 15 200 – 5, 900 73 - 98 07152500 Arkansas Rv at Ralston OK; 07164500 Arkansas Rv at Tulsa OK Brazos Feb-66 – Jun-86 119 15 – 9, 440 59 - 100 08114000 Brazos Rv at Richmond TX Canadian May-49 – Jul-50 16 135 – 141, 000 60 - 100 07227500 Canadian Rv nr Amarillo TX; 07228500 Canadian Rv at Bridgeport OK Colorado (Texas) Dec-69 – Apr-73 16 278 – 3, 630 83 - 100 08161000 Colorado Rv at Columbus TX Copper Aug-54 – Sep-86 39 183 – 3, 900 53 - 82 15212000 Copper Rv nr Chitina AK Gila Aug-60 – Mar-86 95 175 – 200, 000 40 -100 09474000 Gila Rv at Kelvin AZ Kansas Jun-48 – Aug-50 97 270 – 33, 000 56 - 100 06892500 Kansas Rv at Bonner Springs KS Kuskokwim Jun-66 – Sep-86 15 93 – 880 43 - 87 15304000 Kuskokwim Rv at Crooked Creek AK Mississippi Apr-60 – Jun-73 41 143 – 2, 080 52 - 96 07010000 Mississippi Rv at St. Louis MO Missouri Mar-73 – Feb-76 16 676 – 2, 390 53 - 87 06807000 Missouri Rv at Nebraska City NE; 06610000 Missouri Rv at Omaha NE Ohio Nov-79 – Jun-82 24 261 – 908 72 - 98 03294500 Ohio Rv at Louisville KY Pecos Oct-60 – May-89 277 55 – 20, 300 62 - 100 08396500 Pecos Rv nr Artesia NM Platte Mar-73 – Jun-93 37 561 – 14, 100 39 - 99 06805500 Platte Rv at Louisville NE Red Nov-79 – Jun-81 7 1, 070 – 8, 720 38 - 98 07316000 Red Rv near Gainesville TX Rio Grande Apr-66 – Feb-83 62 366 – 7, 000 69 - 100 08475000 Rio Grande nr Brownsville TX Sacramento Feb-58 – Mar-80 98 20 – 1, 970 35 - 98 11447500 Sacramento Rv at Sacramento CA San Joaquin Jul-67 – Sep-89 85 42 – 424 54 - 100 11303500 San Joaquin Rv nr Vernalis CA Stikine Jun-76 – Jul-86 26 144 – 1, 290 34 - 81 15024800 Stikine Rv nr Wrangell AK Susitna Jul-75 – Jul-86 14 257 – 1, 490 41 - 81 15294350 Susitna Rv at Susitna Station AK Susquehanna Aug-79 – Feb-84 23 17 – 359 97 - 100 01578310 Susquehanna Rv at Conowingo MD Tanana May-66 – Jun-83 19 411 – 2, 680 16 - 89 15515500 Tanana Rv at Nenana AK Yellowstone Apr-83 – Jun-91 21 173 – 8, 770 67 - 100 06329500 Yellowstone Rv near Sidney MT Yukon Jun-75 – Sep-86 13 141 – 997 59 - 93 15565447 Yukon Rv at Pilot Station AK USGS gage # and name

River Date range N SSC range (mg/L) Range in % silt-and-clay Arkansas Jun-48 – Sep-81 15 200 – 5, 900 73 - 98 07152500 Arkansas Rv at Ralston OK; 07164500 Arkansas Rv at Tulsa OK Brazos Feb-66 – Jun-86 119 15 – 9, 440 59 - 100 08114000 Brazos Rv at Richmond TX Canadian May-49 – Jul-50 16 135 – 141, 000 60 - 100 07227500 Canadian Rv nr Amarillo TX; 07228500 Canadian Rv at Bridgeport OK Colorado (Texas) Dec-69 – Apr-73 16 278 – 3, 630 83 - 100 08161000 Colorado Rv at Columbus TX Copper Aug-54 – Sep-86 39 183 – 3, 900 53 - 82 15212000 Copper Rv nr Chitina AK Gila Aug-60 – Mar-86 95 175 – 200, 000 40 -100 09474000 Gila Rv at Kelvin AZ Kansas Jun-48 – Aug-50 97 270 – 33, 000 56 - 100 06892500 Kansas Rv at Bonner Springs KS Kuskokwim Jun-66 – Sep-86 15 93 – 880 43 - 87 15304000 Kuskokwim Rv at Crooked Creek AK Mississippi Apr-60 – Jun-73 41 143 – 2, 080 52 - 96 07010000 Mississippi Rv at St. Louis MO Missouri Mar-73 – Feb-76 16 676 – 2, 390 53 - 87 06807000 Missouri Rv at Nebraska City NE; 06610000 Missouri Rv at Omaha NE Ohio Nov-79 – Jun-82 24 261 – 908 72 - 98 03294500 Ohio Rv at Louisville KY Pecos Oct-60 – May-89 277 55 – 20, 300 62 - 100 08396500 Pecos Rv nr Artesia NM Platte Mar-73 – Jun-93 37 561 – 14, 100 39 - 99 06805500 Platte Rv at Louisville NE Red Nov-79 – Jun-81 7 1, 070 – 8, 720 38 - 98 07316000 Red Rv near Gainesville TX Rio Grande Apr-66 – Feb-83 62 366 – 7, 000 69 - 100 08475000 Rio Grande nr Brownsville TX Sacramento Feb-58 – Mar-80 98 20 – 1, 970 35 - 98 11447500 Sacramento Rv at Sacramento CA San Joaquin Jul-67 – Sep-89 85 42 – 424 54 - 100 11303500 San Joaquin Rv nr Vernalis CA Stikine Jun-76 – Jul-86 26 144 – 1, 290 34 - 81 15024800 Stikine Rv nr Wrangell AK Susitna Jul-75 – Jul-86 14 257 – 1, 490 41 - 81 15294350 Susitna Rv at Susitna Station AK Susquehanna Aug-79 – Feb-84 23 17 – 359 97 - 100 01578310 Susquehanna Rv at Conowingo MD Tanana May-66 – Jun-83 19 411 – 2, 680 16 - 89 15515500 Tanana Rv at Nenana AK Yellowstone Apr-83 – Jun-91 21 173 – 8, 770 67 - 100 06329500 Yellowstone Rv near Sidney MT Yukon Jun-75 – Sep-86 13 141 – 997 59 - 93 15565447 Yukon Rv at Pilot Station AK USGS gage # and name

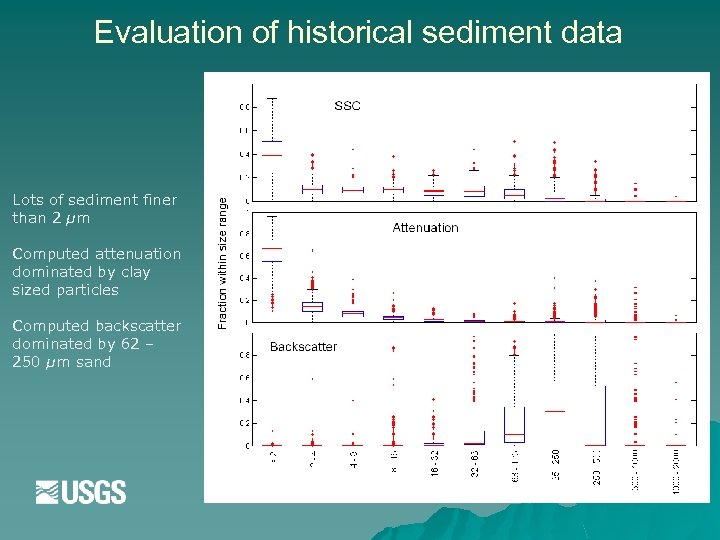

Evaluation of historical sediment data Lots of sediment finer than 2 µm Computed attenuation dominated by clay sized particles Computed backscatter dominated by 62 – 250 µm sand

Evaluation of historical sediment data Lots of sediment finer than 2 µm Computed attenuation dominated by clay sized particles Computed backscatter dominated by 62 – 250 µm sand

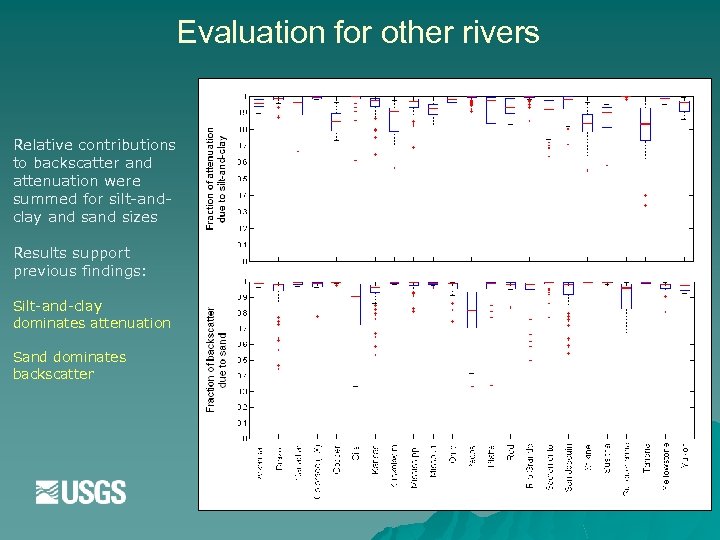

Evaluation for other rivers Relative contributions to backscatter and attenuation were summed for silt-andclay and sizes Results support previous findings: Silt-and-clay dominates attenuation Sand dominates backscatter

Evaluation for other rivers Relative contributions to backscatter and attenuation were summed for silt-andclay and sizes Results support previous findings: Silt-and-clay dominates attenuation Sand dominates backscatter

Outline Ø Brief background on the project Ø Basic theory and approach (single frequency) – Colorado River Ø Applications on other rivers - Gunnison, Clearwater Ø Analysis of historical sediment data using acoustics theory Ø Summary, limitations, publications, FAQs, future work

Outline Ø Brief background on the project Ø Basic theory and approach (single frequency) – Colorado River Ø Applications on other rivers - Gunnison, Clearwater Ø Analysis of historical sediment data using acoustics theory Ø Summary, limitations, publications, FAQs, future work

Summary – single frequency Ø Side-looking acoustic profilers can simultaneously measure two quantities related to suspended sediment: 1) attenuation and 2) backscatter Ø For size distributions typical of rivers, and for typical ADCP frequencies, theory suggests that attenuation should be dominated by the silt-and-clay fraction while backscatter should be dominated by the sand fraction Ø Concurrent ADCP and sediment data from the Colorado, Gunnison, and Clearwater Rivers support theory – need more sites for a more comprehensive assessment Ø Historical sediment data from a large database, analyzed in the context of acoustics theory, also support theory and field-based findings, and suggest that the approach should be generally applicable Ø There are limitations…

Summary – single frequency Ø Side-looking acoustic profilers can simultaneously measure two quantities related to suspended sediment: 1) attenuation and 2) backscatter Ø For size distributions typical of rivers, and for typical ADCP frequencies, theory suggests that attenuation should be dominated by the silt-and-clay fraction while backscatter should be dominated by the sand fraction Ø Concurrent ADCP and sediment data from the Colorado, Gunnison, and Clearwater Rivers support theory – need more sites for a more comprehensive assessment Ø Historical sediment data from a large database, analyzed in the context of acoustics theory, also support theory and field-based findings, and suggest that the approach should be generally applicable Ø There are limitations…

Limitations Ø The silt-and-clay: attenuation and sand: backscatter dependencies can break down under certain conditions, for example when one fraction is present in much, much greater quantities than the other (i. e. if silt-andclay concentrations are high and there is no sand, then silt-and-clay contributes to backscatter); corrections can be developed, but data are needed to do so Ø Changes in particle size distributions can affect calibrations because backscatter and attenuation depend on particle size; multiple frequency applications can help, but increases complexity Ø The technique is more complicated than other “surrogates” (e. g. turbidity, laser-diffraction), it requires processing and editing of large datasets, and an understanding of theory is helpful to interpret “strange” results; we can provide basic guidelines, but each site will be different

Limitations Ø The silt-and-clay: attenuation and sand: backscatter dependencies can break down under certain conditions, for example when one fraction is present in much, much greater quantities than the other (i. e. if silt-andclay concentrations are high and there is no sand, then silt-and-clay contributes to backscatter); corrections can be developed, but data are needed to do so Ø Changes in particle size distributions can affect calibrations because backscatter and attenuation depend on particle size; multiple frequency applications can help, but increases complexity Ø The technique is more complicated than other “surrogates” (e. g. turbidity, laser-diffraction), it requires processing and editing of large datasets, and an understanding of theory is helpful to interpret “strange” results; we can provide basic guidelines, but each site will be different

Multi-frequency Because the backscatter-attenuation-concentrationsize relations depend on frequency, adding frequencies adds new information on the suspension Two different approaches have been used: 1) ratio of backscatter at two frequencies is used to get mean size (coastal applications); 2) assigning different frequencies to different sand size ranges (CO River) These applications are still in the experimental phase, and depend on the specifics of your application Does the need justify the additional cost and complexity involved?

Multi-frequency Because the backscatter-attenuation-concentrationsize relations depend on frequency, adding frequencies adds new information on the suspension Two different approaches have been used: 1) ratio of backscatter at two frequencies is used to get mean size (coastal applications); 2) assigning different frequencies to different sand size ranges (CO River) These applications are still in the experimental phase, and depend on the specifics of your application Does the need justify the additional cost and complexity involved?

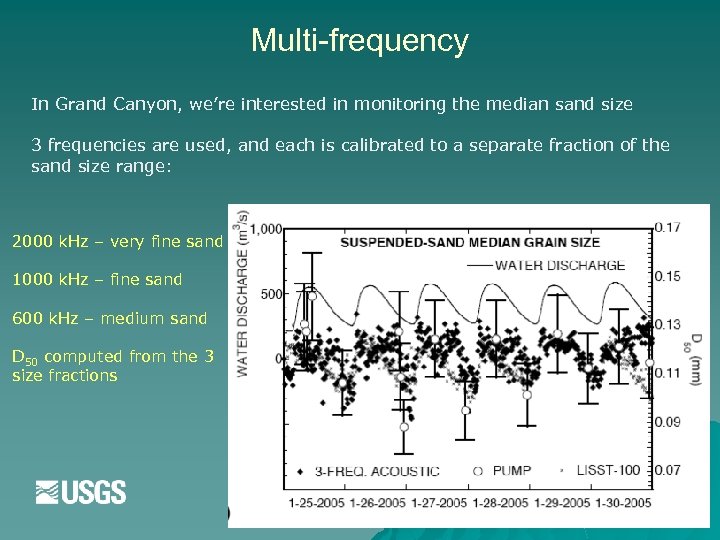

Multi-frequency In Grand Canyon, we’re interested in monitoring the median sand size 3 frequencies are used, and each is calibrated to a separate fraction of the sand size range: 2000 k. Hz – very fine sand 1000 k. Hz – fine sand 600 k. Hz – medium sand D 50 computed from the 3 size fractions

Multi-frequency In Grand Canyon, we’re interested in monitoring the median sand size 3 frequencies are used, and each is calibrated to a separate fraction of the sand size range: 2000 k. Hz – very fine sand 1000 k. Hz – fine sand 600 k. Hz – medium sand D 50 computed from the 3 size fractions

Publications Ø Series of conference papers on Colorado River work, most recent is: Topping, D. J. , Wright, S. A. , Melis, T. S. , and Rubin, D. M. (2007). “High-resolution measurements of suspended-sediment concentration and grain size in the Colorado River in Grand Canyon using a multi-frequency acoustic system”, in Proceedings of the 10 th International Symposium on River Sedimentation. Aug 1– 4, Moscow, Russia. Volume III. Ø Article in review at Journal of Hydraulic Engineering: Wright, S. A. , and Topping, D. J. , in review. “Evaluation of acoustic profilers for discriminating silt-and-clay from suspended-sand in rivers” J. Hyd. Eng. Ø Comprehensive USGS Techniques and Methods report on the Colorado River applications (and maybe others), first-authored by Topping, due by the end of this calendar year Ø Some sort of technical memorandum with basic guidelines for people who want to apply the technology, with answers to FAQs such as:

Publications Ø Series of conference papers on Colorado River work, most recent is: Topping, D. J. , Wright, S. A. , Melis, T. S. , and Rubin, D. M. (2007). “High-resolution measurements of suspended-sediment concentration and grain size in the Colorado River in Grand Canyon using a multi-frequency acoustic system”, in Proceedings of the 10 th International Symposium on River Sedimentation. Aug 1– 4, Moscow, Russia. Volume III. Ø Article in review at Journal of Hydraulic Engineering: Wright, S. A. , and Topping, D. J. , in review. “Evaluation of acoustic profilers for discriminating silt-and-clay from suspended-sand in rivers” J. Hyd. Eng. Ø Comprehensive USGS Techniques and Methods report on the Colorado River applications (and maybe others), first-authored by Topping, due by the end of this calendar year Ø Some sort of technical memorandum with basic guidelines for people who want to apply the technology, with answers to FAQs such as:

Future work Ø Finish writing for this project Ø More data! The most important next step is to expand the number of sites collecting concurrent ADCP and sediment data – we can’t do much more without more data from a range of sites Ø Software development – For the methods to become “general use”, a software package for editing and developing the calibrations would be helpful Ø Coordination and support – Until the methods are more fully tested, it would be helpful to have an ongoing national USGS project tasked with expanding the data network, coordinating the effort, and providing support to WSCs for deployments and data analysis

Future work Ø Finish writing for this project Ø More data! The most important next step is to expand the number of sites collecting concurrent ADCP and sediment data – we can’t do much more without more data from a range of sites Ø Software development – For the methods to become “general use”, a software package for editing and developing the calibrations would be helpful Ø Coordination and support – Until the methods are more fully tested, it would be helpful to have an ongoing national USGS project tasked with expanding the data network, coordinating the effort, and providing support to WSCs for deployments and data analysis

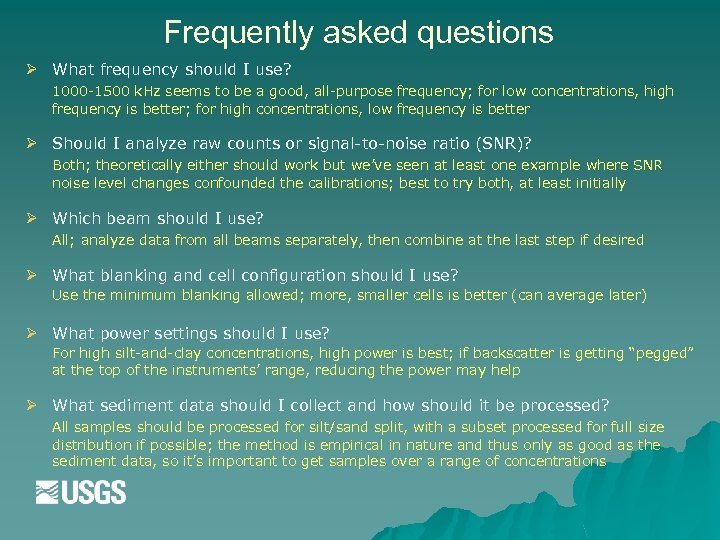

Frequently asked questions Ø What frequency should I use? 1000 -1500 k. Hz seems to be a good, all-purpose frequency; for low concentrations, high frequency is better; for high concentrations, low frequency is better Ø Should I analyze raw counts or signal-to-noise ratio (SNR)? Both; theoretically either should work but we’ve seen at least one example where SNR noise level changes confounded the calibrations; best to try both, at least initially Ø Which beam should I use? All; analyze data from all beams separately, then combine at the last step if desired Ø What blanking and cell configuration should I use? Use the minimum blanking allowed; more, smaller cells is better (can average later) Ø What power settings should I use? For high silt-and-clay concentrations, high power is best; if backscatter is getting “pegged” at the top of the instruments’ range, reducing the power may help Ø What sediment data should I collect and how should it be processed? All samples should be processed for silt/sand split, with a subset processed for full size distribution if possible; the method is empirical in nature and thus only as good as the sediment data, so it’s important to get samples over a range of concentrations

Frequently asked questions Ø What frequency should I use? 1000 -1500 k. Hz seems to be a good, all-purpose frequency; for low concentrations, high frequency is better; for high concentrations, low frequency is better Ø Should I analyze raw counts or signal-to-noise ratio (SNR)? Both; theoretically either should work but we’ve seen at least one example where SNR noise level changes confounded the calibrations; best to try both, at least initially Ø Which beam should I use? All; analyze data from all beams separately, then combine at the last step if desired Ø What blanking and cell configuration should I use? Use the minimum blanking allowed; more, smaller cells is better (can average later) Ø What power settings should I use? For high silt-and-clay concentrations, high power is best; if backscatter is getting “pegged” at the top of the instruments’ range, reducing the power may help Ø What sediment data should I collect and how should it be processed? All samples should be processed for silt/sand split, with a subset processed for full size distribution if possible; the method is empirical in nature and thus only as good as the sediment data, so it’s important to get samples over a range of concentrations

Questions? Scott Wright, sawright@usgs. gov, 916 -278 -3024

Questions? Scott Wright, sawright@usgs. gov, 916 -278 -3024