b3464c4d549ab5aaf9574b0dfe65d01e.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 75

Ethics in Estate Planning: What Is The Difference Between an Estate Planning Lawyer and a Non-Lawyer Estate Planner, and Why Does it Matter? May 28, 2014 Paul P. Morf pmorf@simmonsperrine. com 319 896 4012 www. simmonsperrine. com 1

Ethics in Estate Planning: What Is The Difference Between an Estate Planning Lawyer and a Non-Lawyer Estate Planner, and Why Does it Matter? May 28, 2014 Paul P. Morf pmorf@simmonsperrine. com 319 896 4012 www. simmonsperrine. com 1

Agenda: 1. 2. How has the Iowa Supreme Court’s Ingram decision expanded professional liability to non-lawyers giving estate planning advice? When, under Ingram, may beneficiaries of a client sue the client’s non-lawyer advisors after the client’s death? To what extent has the Iowa Legislature abrogated the holding in Ingram, at least with respect to individuals who sell insurance and who do not charge separately for any other service, including estate planning advice? 2

Agenda: 1. 2. How has the Iowa Supreme Court’s Ingram decision expanded professional liability to non-lawyers giving estate planning advice? When, under Ingram, may beneficiaries of a client sue the client’s non-lawyer advisors after the client’s death? To what extent has the Iowa Legislature abrogated the holding in Ingram, at least with respect to individuals who sell insurance and who do not charge separately for any other service, including estate planning advice? 2

Agenda: 3. 4. How do estate planning attorneys and affiliated estate planning advisors work together for optimal client results? What liability to attorneys and non-attorney advisors subject themselves to if they divert from the “optimal” team approach to planning? 3

Agenda: 3. 4. How do estate planning attorneys and affiliated estate planning advisors work together for optimal client results? What liability to attorneys and non-attorney advisors subject themselves to if they divert from the “optimal” team approach to planning? 3

What is the Unauthorized Practice of Law? 4

What is the Unauthorized Practice of Law? 4

Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø The Iowa Supreme Court has exclusive authority over admission to the practice of law which includes the power to define what constitutes the practice of law and to prevent the unauthorized practice of law by those who have not been properly licensed in Iowa. Ø In order to understand what constitutes the unauthorized practice of law, we must understand what constitutes the practice of law. 5

Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø The Iowa Supreme Court has exclusive authority over admission to the practice of law which includes the power to define what constitutes the practice of law and to prevent the unauthorized practice of law by those who have not been properly licensed in Iowa. Ø In order to understand what constitutes the unauthorized practice of law, we must understand what constitutes the practice of law. 5

IA R 32: 5. 5 – prohibits an attorney from aiding another in the practice of law in a jurisdiction in violation of the regulation of the legal profession in that jurisdiction. Comment says : The definition of the practice of law is established by law and varies from one jurisdiction to another. Whatever the definition, limiting the practice of law to members of the bar protects the public against rendition of legal services by unqualified persons. ” 6

IA R 32: 5. 5 – prohibits an attorney from aiding another in the practice of law in a jurisdiction in violation of the regulation of the legal profession in that jurisdiction. Comment says : The definition of the practice of law is established by law and varies from one jurisdiction to another. Whatever the definition, limiting the practice of law to members of the bar protects the public against rendition of legal services by unqualified persons. ” 6

Definition of Practice of Law Ø There is no one specific definition of what constitutes the practice of law; Ø Rather courts have provided examples of what constitutes the practice of law which includes, but is not limited to: Ø Representing another before the courts; Ø Giving legal advice and counsel to others relating to their rights and obligations under the law; Ø Preparation or approval of the use of legal instruments by which legal rights of others are either obtained, secured or transferred even if such matters never become the subject of a court proceeding. 7

Definition of Practice of Law Ø There is no one specific definition of what constitutes the practice of law; Ø Rather courts have provided examples of what constitutes the practice of law which includes, but is not limited to: Ø Representing another before the courts; Ø Giving legal advice and counsel to others relating to their rights and obligations under the law; Ø Preparation or approval of the use of legal instruments by which legal rights of others are either obtained, secured or transferred even if such matters never become the subject of a court proceeding. 7

Definition of Practice of Law: Ø Functionally, the practice of law relates to the rendition of services for others that call for professional judgment of a lawyer 8

Definition of Practice of Law: Ø Functionally, the practice of law relates to the rendition of services for others that call for professional judgment of a lawyer 8

Commission on Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø The Commission on the Unauthorized Practice of Law, is charged by the Supreme Court with the investigation and abatement of the unauthorized practice of law in Iowa. Ø Iowa Court Rule 37. 1 establishes the Commission on Unauthorized Practice of Law. 9

Commission on Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø The Commission on the Unauthorized Practice of Law, is charged by the Supreme Court with the investigation and abatement of the unauthorized practice of law in Iowa. Ø Iowa Court Rule 37. 1 establishes the Commission on Unauthorized Practice of Law. 9

Commission on Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø The Commission receives complaints related to unauthorized persons practicing law and investigates such complaints. 10

Commission on Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø The Commission receives complaints related to unauthorized persons practicing law and investigates such complaints. 10

Commission on Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø If the commission has reasonable cause to believe that any person is engaging in the practice of law, the commission may seek an injunction to stop the activities constituting the unauthorized practice of law. (Iowa Court Rule 37. 2) Ø Violation of the injunction would result in a finding of contempt of court. 11

Commission on Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø If the commission has reasonable cause to believe that any person is engaging in the practice of law, the commission may seek an injunction to stop the activities constituting the unauthorized practice of law. (Iowa Court Rule 37. 2) Ø Violation of the injunction would result in a finding of contempt of court. 11

Where is the line? When does a nonattorney cross the line into practicing law? When does an attorney inappropriately assist in the unauthorized practice of law? 12

Where is the line? When does a nonattorney cross the line into practicing law? When does an attorney inappropriately assist in the unauthorized practice of law? 12

Baker Decision (1992): Ø Facts: Ø A CFP (Voegtlin) and a bank trust officer (Miller) held seminars for the public promoting revocable trusts. Ø After each seminar, attendees were invited to a free consultation. Ø At the consultation, Voegtlin and Miller would discuss living trusts and diagram how a living trust would work for the individual client. At the conclusion, there would be a consensus as to the estate plan that worked best for the clients. Ø At the conclusion of the consultation, Voegtlin would tell the client to get their attorney involved and if the client did not have an attorney Voegtlin would provide a list of attorneys and recommend Baker. 13

Baker Decision (1992): Ø Facts: Ø A CFP (Voegtlin) and a bank trust officer (Miller) held seminars for the public promoting revocable trusts. Ø After each seminar, attendees were invited to a free consultation. Ø At the consultation, Voegtlin and Miller would discuss living trusts and diagram how a living trust would work for the individual client. At the conclusion, there would be a consensus as to the estate plan that worked best for the clients. Ø At the conclusion of the consultation, Voegtlin would tell the client to get their attorney involved and if the client did not have an attorney Voegtlin would provide a list of attorneys and recommend Baker. 13

Baker Decision (1992): Ø Facts: Ø Attorney Baker agreed to take referrals from Voegtlin that resulted from such consultations. He would receive the work-up documents from the consultation and call the client to discuss them. Ø At the request of Voegtlin, Baker provided Voegtlin with sample copies of living trusts and other estate plan documents, including a Supplemental Financial Plan Letter that stated that Voegtlin was involved in the estate plan and should be involved in the administration of the estate. These documents were to be used as examples during Voegtlin’s consultations. Ø But Baker did the actual drafting after a referral was made to him. 14

Baker Decision (1992): Ø Facts: Ø Attorney Baker agreed to take referrals from Voegtlin that resulted from such consultations. He would receive the work-up documents from the consultation and call the client to discuss them. Ø At the request of Voegtlin, Baker provided Voegtlin with sample copies of living trusts and other estate plan documents, including a Supplemental Financial Plan Letter that stated that Voegtlin was involved in the estate plan and should be involved in the administration of the estate. These documents were to be used as examples during Voegtlin’s consultations. Ø But Baker did the actual drafting after a referral was made to him. 14

Baker Decision (1992): Ø QUESTION: Did Voegtlin Engage in the Unauthorized Practice of Law? : YES Ø Court expanded definition of the practice of law to include: Ø Giving legal advice, directly or indirectly to individuals or groups concerning the application, preparation, advisability or quality of any legal instrument or document or forms thereof in connection with the disposition of property inter vivos or upon death, including inter vivos trusts and wills. Ø Court found that Voegtlin was engaged in the unauthorized practice of law since he met with clients, advised them about what they needed in the way of estate planning including what documents they needed and how those documents should be tailored. Ø Baker’s role was one of a scrivener of Voegtlin’s determinations. 15 Voegtlin, rather than Baker, was exercising professional judgment.

Baker Decision (1992): Ø QUESTION: Did Voegtlin Engage in the Unauthorized Practice of Law? : YES Ø Court expanded definition of the practice of law to include: Ø Giving legal advice, directly or indirectly to individuals or groups concerning the application, preparation, advisability or quality of any legal instrument or document or forms thereof in connection with the disposition of property inter vivos or upon death, including inter vivos trusts and wills. Ø Court found that Voegtlin was engaged in the unauthorized practice of law since he met with clients, advised them about what they needed in the way of estate planning including what documents they needed and how those documents should be tailored. Ø Baker’s role was one of a scrivener of Voegtlin’s determinations. 15 Voegtlin, rather than Baker, was exercising professional judgment.

Baker Decision (1992): Ø Aiding in the Unauthorized Practice of Law – Did Baker aid in Voegtlin’s Unauthorized Practice of Law? : Ø Court found that Baker violated these rules since Voegtlin controlled the whole process from the initial interview to the final meeting with the client. He recommended the living trust, the necessary documents to effectuate it, and recommended a lawyer who he believed would not counsel against his advice. Ø Baker never discouraged Voegtlin and instead encouraged it by: Ø Allowing Voegtlin to exercise the professional judgment; Ø Allowing Voegtlin to act in a confidential capacity with clients referred to him; Ø Furnishing Voegtlin with forms to be used in his seminar; Ø Accepting over 100 referrals from Voegtlin; 16 Ø Provided Voegtlin advice with regard to marketing materials.

Baker Decision (1992): Ø Aiding in the Unauthorized Practice of Law – Did Baker aid in Voegtlin’s Unauthorized Practice of Law? : Ø Court found that Baker violated these rules since Voegtlin controlled the whole process from the initial interview to the final meeting with the client. He recommended the living trust, the necessary documents to effectuate it, and recommended a lawyer who he believed would not counsel against his advice. Ø Baker never discouraged Voegtlin and instead encouraged it by: Ø Allowing Voegtlin to exercise the professional judgment; Ø Allowing Voegtlin to act in a confidential capacity with clients referred to him; Ø Furnishing Voegtlin with forms to be used in his seminar; Ø Accepting over 100 referrals from Voegtlin; 16 Ø Provided Voegtlin advice with regard to marketing materials.

Baker Decision (1992): Ø Conflict of Interest: Ø Court also found that since Voegtlin was allowed to direct or regulate Baker’s professional judgment in rendering legal services to his referred clients, a conflict of interest existed for Baker since this interfered with his loyalty to his clients. Ø Note: Attorneys are subject to more demanding conflict of interest rules than most other professionals. If we represent multiple generations in a single family, that is a complicated ethical situation. 17

Baker Decision (1992): Ø Conflict of Interest: Ø Court also found that since Voegtlin was allowed to direct or regulate Baker’s professional judgment in rendering legal services to his referred clients, a conflict of interest existed for Baker since this interfered with his loyalty to his clients. Ø Note: Attorneys are subject to more demanding conflict of interest rules than most other professionals. If we represent multiple generations in a single family, that is a complicated ethical situation. 17

Baker Decision (1992): Ø Disciplinary Action: Ø As a result of the Court’s findings, Baker was publicly reprimanded by the court and assessed all costs related to the hearing. 18

Baker Decision (1992): Ø Disciplinary Action: Ø As a result of the Court’s findings, Baker was publicly reprimanded by the court and assessed all costs related to the hearing. 18

Question Ø What is the real distinction between a lawyer and a nonlawyer in the estate planning field? Ø Do all lawyers know more about estate planning than all CFPs, all CLUs, Trust Officers, Planned Giving Officers? [no] Ø Are there some CFPs, CLUs, Trust Officers, and Planned Giving Officers that know more about estate planning than 90% of Iowa attorney? [yes, probably] 19

Question Ø What is the real distinction between a lawyer and a nonlawyer in the estate planning field? Ø Do all lawyers know more about estate planning than all CFPs, all CLUs, Trust Officers, Planned Giving Officers? [no] Ø Are there some CFPs, CLUs, Trust Officers, and Planned Giving Officers that know more about estate planning than 90% of Iowa attorney? [yes, probably] 19

Question Ø What then makes the attorney unique? Ø Ethical rules re Conflicts of Interest and Independent Judgment Ø Scope of the Work and Reasonable Expectations of the Client Ø Ideally, knowledge and training regarding the entire breadth of the law that applies to estate planning documents (but. Ø The Buck Stops With the Lawyer (not the CLU, CFP, Trust Officer, or Planned Giving Officer) Regarding any Documents that are Drafted and Executed. So the attorney needs to exercise independent judgment to make sure they are suitable and fit for the unique needs of the client in question. 20

Question Ø What then makes the attorney unique? Ø Ethical rules re Conflicts of Interest and Independent Judgment Ø Scope of the Work and Reasonable Expectations of the Client Ø Ideally, knowledge and training regarding the entire breadth of the law that applies to estate planning documents (but. Ø The Buck Stops With the Lawyer (not the CLU, CFP, Trust Officer, or Planned Giving Officer) Regarding any Documents that are Drafted and Executed. So the attorney needs to exercise independent judgment to make sure they are suitable and fit for the unique needs of the client in question. 20

Sturgeon Decision (2001): Ø Involved a disbarred attorney, Sturgeon, who assisted clients in completing the paperwork necessary to file for bankruptcy; Ø Sturgeon’s office contained multiple signs stating he is a “non-attorney bankruptcy specialist” and “no legal advice” is given. 21

Sturgeon Decision (2001): Ø Involved a disbarred attorney, Sturgeon, who assisted clients in completing the paperwork necessary to file for bankruptcy; Ø Sturgeon’s office contained multiple signs stating he is a “non-attorney bankruptcy specialist” and “no legal advice” is given. 21

Sturgeon Decision (2001): Ø The Court said that “the line drawn when unauthorized practice of law occurs is at the point at which data entry crosses the line between copying written information provided by the client and oral solicitation of the information necessary to fill out documents selected by the preparer. ” Ø Court Conclusion: Sturgeon participated in the selection, preparation, and filing of the bankruptcy forms, and the advice rendered to his clients crossed the line from merely filling out forms to practicing law. 22

Sturgeon Decision (2001): Ø The Court said that “the line drawn when unauthorized practice of law occurs is at the point at which data entry crosses the line between copying written information provided by the client and oral solicitation of the information necessary to fill out documents selected by the preparer. ” Ø Court Conclusion: Sturgeon participated in the selection, preparation, and filing of the bankruptcy forms, and the advice rendered to his clients crossed the line from merely filling out forms to practicing law. 22

Sturgeon Decision (2001): Ø Court Order: Ø Court upheld the injunction, with one slight change, against Sturgeon permanently enjoining Sturgeon from engaging in those activities which constitute the practice of law including 1) preparation of bankruptcy documents; 2) preparing documents for others in connection with judicial proceedings; 3) preparing or approving the use of legal instruments by which legal rights of others are either obtained, secured, or transferred; 4) giving legal advice to others relating to their legal rights and obligations under the law; or 5) otherwise providing advice or services which constitute the practice of law. 23

Sturgeon Decision (2001): Ø Court Order: Ø Court upheld the injunction, with one slight change, against Sturgeon permanently enjoining Sturgeon from engaging in those activities which constitute the practice of law including 1) preparation of bankruptcy documents; 2) preparing documents for others in connection with judicial proceedings; 3) preparing or approving the use of legal instruments by which legal rights of others are either obtained, secured, or transferred; 4) giving legal advice to others relating to their legal rights and obligations under the law; or 5) otherwise providing advice or services which constitute the practice of law. 23

Consequences of Crossing the Line 24

Consequences of Crossing the Line 24

Consequences to Aiding in the Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø Attorney Sanctions: Ø If an Attorney is found to have aided another in the unauthorized practice of law, the Attorney will be subject to discipline action and investigation from the Commission, the Iowa Disciplinary Board, and the Iowa Supreme Court. Ø Potential disciplinary actions that could be taken against an attorney include: Ø Public reprimand; Ø Sanctions; Ø Suspension of law license; Ø In extreme cases, disbarment. 25

Consequences to Aiding in the Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø Attorney Sanctions: Ø If an Attorney is found to have aided another in the unauthorized practice of law, the Attorney will be subject to discipline action and investigation from the Commission, the Iowa Disciplinary Board, and the Iowa Supreme Court. Ø Potential disciplinary actions that could be taken against an attorney include: Ø Public reprimand; Ø Sanctions; Ø Suspension of law license; Ø In extreme cases, disbarment. 25

Consequences to Engaging in/Aiding in Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø Injunction: Ø Definition - a judicial order that restrains a person from beginning or continuing an action threatening or invading the legal right of another, or that compels a person to carry out a certain act, e. g. , to make restitution to an injured party. Ø In other words, a court may order you to stop what you are doing, including limiting or stopping someone from providing advisory services if the court believes it encroaches the practice of law. Ø Failure to comply with such a court order could result in you being found in contempt of court. 26

Consequences to Engaging in/Aiding in Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø Injunction: Ø Definition - a judicial order that restrains a person from beginning or continuing an action threatening or invading the legal right of another, or that compels a person to carry out a certain act, e. g. , to make restitution to an injured party. Ø In other words, a court may order you to stop what you are doing, including limiting or stopping someone from providing advisory services if the court believes it encroaches the practice of law. Ø Failure to comply with such a court order could result in you being found in contempt of court. 26

Consequences to Engaging in/Aiding in Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø Legal Liability: Ø Clients (or other interested persons under an estate plan) could sue for damages (at least if your business is not limited to selling life insurance). Ø Beyond the risk of court ordered damages, there is the time and costs associated with litigating the matter. 27

Consequences to Engaging in/Aiding in Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø Legal Liability: Ø Clients (or other interested persons under an estate plan) could sue for damages (at least if your business is not limited to selling life insurance). Ø Beyond the risk of court ordered damages, there is the time and costs associated with litigating the matter. 27

Consequences to Engaging in/Aiding in Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø Other Negative Consequences: Ø Reputational harm to you and your business; Ø Potential implications on professional licenses or membership in professional associations. 28

Consequences to Engaging in/Aiding in Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø Other Negative Consequences: Ø Reputational harm to you and your business; Ø Potential implications on professional licenses or membership in professional associations. 28

Consequences to Engaging in/Aiding in Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø Legal Liability: Ø Significant New Iowa Supreme Court Decision: Ø St. Malachy Roman Catholic Congregation of Geneseo v. Ingram, 841 N. W. 2 d 338, 340 (Iowa 2013), reh'g denied (Feb. 11, 2014). 29

Consequences to Engaging in/Aiding in Unauthorized Practice of Law: Ø Legal Liability: Ø Significant New Iowa Supreme Court Decision: Ø St. Malachy Roman Catholic Congregation of Geneseo v. Ingram, 841 N. W. 2 d 338, 340 (Iowa 2013), reh'g denied (Feb. 11, 2014). 29

Ingram Case: Disclaimer • The Author Makes No Statement or Evaluation Regarding the Relative Merits of the Parties to this Case. • All statements regarding the Facts of the Ingram case are taken from the Iowa Supreme Court’s Published Decision. The author has not personally verified any of these facts, and makes no comment as to their accuracy. • The purpose of this discussion is not to evaluate the rightness or wrongness of the actions of any party to the Ingram case, but rather general educational purposes regarding developments in the law which may inform best practices and risk management decisions going forward. 30

Ingram Case: Disclaimer • The Author Makes No Statement or Evaluation Regarding the Relative Merits of the Parties to this Case. • All statements regarding the Facts of the Ingram case are taken from the Iowa Supreme Court’s Published Decision. The author has not personally verified any of these facts, and makes no comment as to their accuracy. • The purpose of this discussion is not to evaluate the rightness or wrongness of the actions of any party to the Ingram case, but rather general educational purposes regarding developments in the law which may inform best practices and risk management decisions going forward. 30

Ingram Case: Question Presented • Question: Can a financial advisor of a deceased client be sued by identified beneficiaries of the deceased client's signed written estate plan when, due to the advisor's allegedly negligent performance of his duties, those beneficiaries do not receive what they were supposed to get under the plan? – Note: The answer is already “yes” for attorneys. Schreiner v. Scoville, 410 N. W. 2 d 679, 682 (Iowa 1987). 31

Ingram Case: Question Presented • Question: Can a financial advisor of a deceased client be sued by identified beneficiaries of the deceased client's signed written estate plan when, due to the advisor's allegedly negligent performance of his duties, those beneficiaries do not receive what they were supposed to get under the plan? – Note: The answer is already “yes” for attorneys. Schreiner v. Scoville, 410 N. W. 2 d 679, 682 (Iowa 1987). 31

Ingram Case: Holding • “We conclude the rationale of Schreiner v. Scoville, 410 N. W. 2 d 679, 682 (Iowa 1987), which held that attorneys could be sued in these circumstances, extends to nonattorneys acting within the scope of their agency. ” 32

Ingram Case: Holding • “We conclude the rationale of Schreiner v. Scoville, 410 N. W. 2 d 679, 682 (Iowa 1987), which held that attorneys could be sued in these circumstances, extends to nonattorneys acting within the scope of their agency. ” 32

Ingram Case Facts: Alvin Engels Died February 2006, 80 Yrs Old No Children In About 1993, Engels retained James “Jay” Ingram of Piper Jaffray as a securities registered representative. Ø Engels and Ingram consulted re estate planning Ø Ø Ø 33

Ingram Case Facts: Alvin Engels Died February 2006, 80 Yrs Old No Children In About 1993, Engels retained James “Jay” Ingram of Piper Jaffray as a securities registered representative. Ø Engels and Ingram consulted re estate planning Ø Ø Ø 33

Ingram Case : Facts Ø On September 24, 1999, Engels executed a revocable trust agreement that appointed Engels and Loretta Wongstrom as co-trustees of the Alvin F. Engels Revocable Trust. Ø Engels also created the Engels Charitable Foundation, a not-for-profit corporation, of which Engels, Ingram, and Wongstrom were appointed directors. Ø The Revocable Trust and Charitable Foundation paperwork was drafted by attorney Jerry Pepping Ø Ingram handled the transfer of Engels's assets—including his home, checking accounts, Piper account, series H and HH bonds, a promissory note, and a variable annuity—to the Revocable Trust 34

Ingram Case : Facts Ø On September 24, 1999, Engels executed a revocable trust agreement that appointed Engels and Loretta Wongstrom as co-trustees of the Alvin F. Engels Revocable Trust. Ø Engels also created the Engels Charitable Foundation, a not-for-profit corporation, of which Engels, Ingram, and Wongstrom were appointed directors. Ø The Revocable Trust and Charitable Foundation paperwork was drafted by attorney Jerry Pepping Ø Ingram handled the transfer of Engels's assets—including his home, checking accounts, Piper account, series H and HH bonds, a promissory note, and a variable annuity—to the Revocable Trust 34

Ingram Case : Facts • The Revocable Trust agreement provided for a “zero estate tax plan, ” passing the tax-free amount to Trust B for individuals, and the rest to Trust A for non-profits. – Trust A would be funded only to the extent necessary to minimize federal estate taxes. The contents of Trust A were to be distributed to the Charitable Foundation, except for $15, 000, which would go to St. Malachy Roman Catholic Congregation (St. Malachy's). – Trust B would receive the remaining assets, which would be used for the benefit of some neighbors and nieces and nephews (Katherine, Andrea, and Andrew Bristol and Jerri Mc. Lane, Lynn Mc. Lane, and James Kleinau) 35

Ingram Case : Facts • The Revocable Trust agreement provided for a “zero estate tax plan, ” passing the tax-free amount to Trust B for individuals, and the rest to Trust A for non-profits. – Trust A would be funded only to the extent necessary to minimize federal estate taxes. The contents of Trust A were to be distributed to the Charitable Foundation, except for $15, 000, which would go to St. Malachy Roman Catholic Congregation (St. Malachy's). – Trust B would receive the remaining assets, which would be used for the benefit of some neighbors and nieces and nephews (Katherine, Andrea, and Andrew Bristol and Jerri Mc. Lane, Lynn Mc. Lane, and James Kleinau) 35

Ingram Case : Facts • “It is clear that Ingram was involved, to some degree, in the planning for Engels's estate during this time, including the Revocable Trust. ” – Pepping sent drafts of the Revocable Trust agreement and a draft of Engels's last will and testament to Engels, Ingram, and Wongstrom. – Ingram was also named as executor of Engels's will in an October 1, 2001 codicil and, on the same day, was named as the successor trustee of the Revocable Trust. – Less than a year later, Ingram was appointed Engels's attorney-infact for healthcare decisions. 36

Ingram Case : Facts • “It is clear that Ingram was involved, to some degree, in the planning for Engels's estate during this time, including the Revocable Trust. ” – Pepping sent drafts of the Revocable Trust agreement and a draft of Engels's last will and testament to Engels, Ingram, and Wongstrom. – Ingram was also named as executor of Engels's will in an October 1, 2001 codicil and, on the same day, was named as the successor trustee of the Revocable Trust. – Less than a year later, Ingram was appointed Engels's attorney-infact for healthcare decisions. 36

Ingram Case : Facts • In approximately November 1999, Ingram left Piper Jaffray for Robert W. Baird & Co. He took the Engels account with him. 37

Ingram Case : Facts • In approximately November 1999, Ingram left Piper Jaffray for Robert W. Baird & Co. He took the Engels account with him. 37

Ingram Case : Facts • In 2003, Engels apparently decided to alter his estate plan. • On October 1, 2003, Engels executed five documents: – (1) a durable power of attorney appointing Jerri Mc. Lane as attorney-in-fact for healthcare decisions, – (2) a living will, – (3) a durable financial power of attorney appointing Ingram attorney-in-fact for Engels's financial affairs, – (4) a new last will and testament, and – (5) a charitable trust agreement creating the Alvin F. Engels Charitable Trust. – – NOTE: NO REVOCATION OF REVOCABLE TRUST: THIS WILL REPLACED THE POUR-OVER WILL, BUT THE REVOCABLE TRUST HAD ALREADY BEEN FUNDED, SO CHANGING THE WILL DID NOT CHANGE THE DISPOSITION OF THE REVOCABLE TRUST ASSETS. 38

Ingram Case : Facts • In 2003, Engels apparently decided to alter his estate plan. • On October 1, 2003, Engels executed five documents: – (1) a durable power of attorney appointing Jerri Mc. Lane as attorney-in-fact for healthcare decisions, – (2) a living will, – (3) a durable financial power of attorney appointing Ingram attorney-in-fact for Engels's financial affairs, – (4) a new last will and testament, and – (5) a charitable trust agreement creating the Alvin F. Engels Charitable Trust. – – NOTE: NO REVOCATION OF REVOCABLE TRUST: THIS WILL REPLACED THE POUR-OVER WILL, BUT THE REVOCABLE TRUST HAD ALREADY BEEN FUNDED, SO CHANGING THE WILL DID NOT CHANGE THE DISPOSITION OF THE REVOCABLE TRUST ASSETS. 38

Ingram Case : Facts • These documents were drafted by a different attorney (attorney Marie Tarbox of the law firm Gosma, Tarbox & Associates). – Ingram signed the Charitable Trust agreement. – Ingram's wife witnessed three of the documents, and each document, with the exception of the living will, was also notarized by Ingram's assistant, Mardee Trapkus 39

Ingram Case : Facts • These documents were drafted by a different attorney (attorney Marie Tarbox of the law firm Gosma, Tarbox & Associates). – Ingram signed the Charitable Trust agreement. – Ingram's wife witnessed three of the documents, and each document, with the exception of the living will, was also notarized by Ingram's assistant, Mardee Trapkus 39

Ingram Case : Facts • The Will provided that Steve Bristol would receive Engels's residence located in Geneseo, Illinois. • In addition, the Will made specific bequests of $75, 000 to Jerri Mc. Lane, $25, 000 to Lynn Mc. Lane, and $25, 000 to James Kleinau. • However, the entire residue of the estate after these bequests was to be paid to the Charitable Trust. The Will named Jerri Mc. Lane as executor and Ingram as successor executor in the event Mc. Lane could not serve. • In article 5, Ingram and Jerri Mc. Lane were designated to serve as cotrustees of the Charitable Trust upon Engels's death. 40

Ingram Case : Facts • The Will provided that Steve Bristol would receive Engels's residence located in Geneseo, Illinois. • In addition, the Will made specific bequests of $75, 000 to Jerri Mc. Lane, $25, 000 to Lynn Mc. Lane, and $25, 000 to James Kleinau. • However, the entire residue of the estate after these bequests was to be paid to the Charitable Trust. The Will named Jerri Mc. Lane as executor and Ingram as successor executor in the event Mc. Lane could not serve. • In article 5, Ingram and Jerri Mc. Lane were designated to serve as cotrustees of the Charitable Trust upon Engels's death. 40

Ingram Case : Facts • The Charitable Trust provided in article 3 as follows: “On the death of the Grantor [Engels], the Trustee shall distribute the net income and so much of the Trust principal as the Trustee may determine among St. Malachy's Catholic Church, Geneseo, Illinois, and the United Way and the American Red Cross, with direction that distributions to the latter two organization[s] shall be used for the benefit of residents of Henry County, Illinois, and to such other 501(c)(3) organizations benefitting Henry County, Illinois as may apply for distributions and which the Trustee, in its sole discretion, determines appropriate in any given year. The Grantor recognizes that he is placing a good deal of discretionary power in the Trustee, and is confident that the Trustee will exercise its discretionary power in a manner that will best meet[ ] the needs of the charitable organizations named herein, Geneseo, Illinois and Henry 41 County, Illinois over the years. ”

Ingram Case : Facts • The Charitable Trust provided in article 3 as follows: “On the death of the Grantor [Engels], the Trustee shall distribute the net income and so much of the Trust principal as the Trustee may determine among St. Malachy's Catholic Church, Geneseo, Illinois, and the United Way and the American Red Cross, with direction that distributions to the latter two organization[s] shall be used for the benefit of residents of Henry County, Illinois, and to such other 501(c)(3) organizations benefitting Henry County, Illinois as may apply for distributions and which the Trustee, in its sole discretion, determines appropriate in any given year. The Grantor recognizes that he is placing a good deal of discretionary power in the Trustee, and is confident that the Trustee will exercise its discretionary power in a manner that will best meet[ ] the needs of the charitable organizations named herein, Geneseo, Illinois and Henry 41 County, Illinois over the years. ”

Ingram Case: • As with the 1999 estate planning documents, the record reflects that Ingram was heavily involved in the development of the 2003 Will and Charitable Trust. • • • Tarbox testified she had a referral relationship with Ingram and received four-to-six referrals from him annually between 1998 and 2002. In each referral, Tarbox testified Ingram typically provided her with background information about the client in the sense of what their asset value was, if there was a trust in existence, information about the family, information about things that may be of particular concern to that client, and if there had been [specific] things that he had discussed with the client․ Engels was one of these referrals. Tarbox said she had three or four conversations with Ingram in which he outlined Engels's estate plan before she ever met with Engels. According to Tarbox, during her meeting with Engels, Mardee Trapkus—Ingram's assistant—was also present. Tarbox stated Ingram had told her in advance which charities Engels wanted to benefit. 42

Ingram Case: • As with the 1999 estate planning documents, the record reflects that Ingram was heavily involved in the development of the 2003 Will and Charitable Trust. • • • Tarbox testified she had a referral relationship with Ingram and received four-to-six referrals from him annually between 1998 and 2002. In each referral, Tarbox testified Ingram typically provided her with background information about the client in the sense of what their asset value was, if there was a trust in existence, information about the family, information about things that may be of particular concern to that client, and if there had been [specific] things that he had discussed with the client․ Engels was one of these referrals. Tarbox said she had three or four conversations with Ingram in which he outlined Engels's estate plan before she ever met with Engels. According to Tarbox, during her meeting with Engels, Mardee Trapkus—Ingram's assistant—was also present. Tarbox stated Ingram had told her in advance which charities Engels wanted to benefit. 42

Ingram Case : Facts • “Despite Ingram's history of disclosing a client's existing trusts, Ingram made no mention of the existence of Engels's Revocable Trust. Tarbox indicated she did not become aware of the existence of the Revocable Trust or the Charitable Foundation until after Engels's death. ” 43

Ingram Case : Facts • “Despite Ingram's history of disclosing a client's existing trusts, Ingram made no mention of the existence of Engels's Revocable Trust. Tarbox indicated she did not become aware of the existence of the Revocable Trust or the Charitable Foundation until after Engels's death. ” 43

![Ingram Case : Facts • With [a] letter, she enclosed draft documents, including versions Ingram Case : Facts • With [a] letter, she enclosed draft documents, including versions](https://present5.com/presentation/b3464c4d549ab5aaf9574b0dfe65d01e/image-44.jpg) Ingram Case : Facts • With [a] letter, she enclosed draft documents, including versions of the Will and Charitable Trust agreement. • She later testified it was her intention that Engels would review the documents and return to her office to execute them if they were acceptable. According to Tarbox, rather than returning to Tarbox's office, Engels executed the documents and merely had copies delivered to Tarbox. • Tarbox was angry that Engels had executed the documents outside of her office. • Apparently, Tarbox and Engels patched things up because Tarbox continued to do work for Engels. 44

Ingram Case : Facts • With [a] letter, she enclosed draft documents, including versions of the Will and Charitable Trust agreement. • She later testified it was her intention that Engels would review the documents and return to her office to execute them if they were acceptable. According to Tarbox, rather than returning to Tarbox's office, Engels executed the documents and merely had copies delivered to Tarbox. • Tarbox was angry that Engels had executed the documents outside of her office. • Apparently, Tarbox and Engels patched things up because Tarbox continued to do work for Engels. 44

Ingram Case : Facts • Meanwhile, the record indicates that Ingram made several efforts to get Engels to transfer his assets into his Charitable Trust during his lifetime. – On January 23, 2004, Ingram's assistant Trapkus sent Engels a letter that stated, “I have enclosed a form that needs to be signed so that Marie Tarbox can change the ownership of your house into the [Charitable] Trust that you have created. Please sign by the red arrow and return to me in the envelope I have enclosed. I will notarize your signature for you. ” – Nineteen days later, on February 11, 2004, Tarbox's office sent a quitclaim deed to the recorder's office. The quitclaim deed stated “Alvin F. Engels” was conveying the home in Geneseo to the “Alvin F. Engels Charitable Trust Agreement. ” The deed was recorded on February 23, 2004. – However, apparently unbeknownst to Tarbox, at the time the home was titled in the name of the Revocable Trust, not in Engels's name, so the deed was ineffective. 45

Ingram Case : Facts • Meanwhile, the record indicates that Ingram made several efforts to get Engels to transfer his assets into his Charitable Trust during his lifetime. – On January 23, 2004, Ingram's assistant Trapkus sent Engels a letter that stated, “I have enclosed a form that needs to be signed so that Marie Tarbox can change the ownership of your house into the [Charitable] Trust that you have created. Please sign by the red arrow and return to me in the envelope I have enclosed. I will notarize your signature for you. ” – Nineteen days later, on February 11, 2004, Tarbox's office sent a quitclaim deed to the recorder's office. The quitclaim deed stated “Alvin F. Engels” was conveying the home in Geneseo to the “Alvin F. Engels Charitable Trust Agreement. ” The deed was recorded on February 23, 2004. – However, apparently unbeknownst to Tarbox, at the time the home was titled in the name of the Revocable Trust, not in Engels's name, so the deed was ineffective. 45

Ingram Case : Facts • Approximately one year later, in February 2005, Ingram sent another letter to Engels regarding the Charitable Trust. – In it he stated: “Mardee [Trapkus] indicated that you have some issues with Marie [Tarbox]. It's important to make choices according to what you want. (It's your money and you can control where it goes. ) I've enclosed transfer forms that are necessary to move your assets into the [C]haritable [T]rust. Enclosed are forms necessary to transfer your assets into the [C]haritable [T]rust. ” – Tarbox testified she was unaware of Ingram's attempts to transfer Engels's property into the Charitable Trust. Had she been asked about the transfers, she claims she would have told Ingram or Engels the transfers were “inappropriate” because Engels would lose the benefit of those assets during his life. Yet, it is not disputed that Tarbox's office sent the quitclaim deed for Engels's home to the recorder's office in February 2004. 46

Ingram Case : Facts • Approximately one year later, in February 2005, Ingram sent another letter to Engels regarding the Charitable Trust. – In it he stated: “Mardee [Trapkus] indicated that you have some issues with Marie [Tarbox]. It's important to make choices according to what you want. (It's your money and you can control where it goes. ) I've enclosed transfer forms that are necessary to move your assets into the [C]haritable [T]rust. Enclosed are forms necessary to transfer your assets into the [C]haritable [T]rust. ” – Tarbox testified she was unaware of Ingram's attempts to transfer Engels's property into the Charitable Trust. Had she been asked about the transfers, she claims she would have told Ingram or Engels the transfers were “inappropriate” because Engels would lose the benefit of those assets during his life. Yet, it is not disputed that Tarbox's office sent the quitclaim deed for Engels's home to the recorder's office in February 2004. 46

Ingram Case : Facts • Several months later, in August 2005, Ingram again wrote Engels urging him to fund the Charitable Trust by transferring his brokerage account assets into it. Ingram noted the annual income on Engels's account amounted to $20, 000 and “[t]he annual gifting of $20, 000+ to worthwhile charities, organizations and scholarships will make a substantial impact on the lives of many people in the future. ” Ingram added, “We really need to get the [C]haritable [T]rust funded, so please return the enclosed forms to your attorney when you make your changes. ” 47

Ingram Case : Facts • Several months later, in August 2005, Ingram again wrote Engels urging him to fund the Charitable Trust by transferring his brokerage account assets into it. Ingram noted the annual income on Engels's account amounted to $20, 000 and “[t]he annual gifting of $20, 000+ to worthwhile charities, organizations and scholarships will make a substantial impact on the lives of many people in the future. ” Ingram added, “We really need to get the [C]haritable [T]rust funded, so please return the enclosed forms to your attorney when you make your changes. ” 47

Ingram Case : Facts • On January 6, 2006, Ingram's office called Tarbox to let her know that Engels wanted to change the designated individual on his healthcare power of attorney. Tarbox drafted the necessary forms and sent them to the new designee. • At this time, Engels's health was deteriorating. Ingram sent a letter to Central Trust and Savings Bank indicating Tarbox had “requested that [Ingram] assist [Engels] in compliance with his Durable Financial Power of Attorney dated October 1, 2003. ” He asked the bank to “honor [Ingram's] signature on [Engels]'s personal checks until further notice. ” Engels died on February 12, 2006 - 48

Ingram Case : Facts • On January 6, 2006, Ingram's office called Tarbox to let her know that Engels wanted to change the designated individual on his healthcare power of attorney. Tarbox drafted the necessary forms and sent them to the new designee. • At this time, Engels's health was deteriorating. Ingram sent a letter to Central Trust and Savings Bank indicating Tarbox had “requested that [Ingram] assist [Engels] in compliance with his Durable Financial Power of Attorney dated October 1, 2003. ” He asked the bank to “honor [Ingram's] signature on [Engels]'s personal checks until further notice. ” Engels died on February 12, 2006 - 48

Ingram Case : Facts • On February 15, 2006, Tarbox sent a letter to Ingram offering “a short review of Mr. Engels'[s] estate plan documents. ” In it, she went over the terms of the Will and the Charitable Trust. Tarbox testified she first became aware of the Revocable Trust after Engels's estate was opened and Ingram provided the Revocable Trust documents to her. 49

Ingram Case : Facts • On February 15, 2006, Tarbox sent a letter to Ingram offering “a short review of Mr. Engels'[s] estate plan documents. ” In it, she went over the terms of the Will and the Charitable Trust. Tarbox testified she first became aware of the Revocable Trust after Engels's estate was opened and Ingram provided the Revocable Trust documents to her. 49

Ingram Case : Facts • In a handwritten, one-page document that Ingram created after Engels's death entitled “Alvin Engels Estate, ” Ingram listed the monetary bequests to the nieces and nephew under the Will and additionally noted the house was to “deed out quickly to Bristol. ” 50

Ingram Case : Facts • In a handwritten, one-page document that Ingram created after Engels's death entitled “Alvin Engels Estate, ” Ingram listed the monetary bequests to the nieces and nephew under the Will and additionally noted the house was to “deed out quickly to Bristol. ” 50

Ingram Case : Facts • It is not clear when Ingram became aware that Engels's assets would pass according to the Revocable Trust rather than the Will. • Regardless, he clearly knew this by August 15, 2006, when he sent the following letter to the priest of St. Malachy's: – “Hi Father—Please accept this as a donation to help cover the cost of the funeral luncheon for [Engels]'s intentions were to remember St. Malachy's in a significant manner, but his last will was declared invalid and his entire estate will be given to his relatives. It's unfortunate. ” 51

Ingram Case : Facts • It is not clear when Ingram became aware that Engels's assets would pass according to the Revocable Trust rather than the Will. • Regardless, he clearly knew this by August 15, 2006, when he sent the following letter to the priest of St. Malachy's: – “Hi Father—Please accept this as a donation to help cover the cost of the funeral luncheon for [Engels]'s intentions were to remember St. Malachy's in a significant manner, but his last will was declared invalid and his entire estate will be given to his relatives. It's unfortunate. ” 51

Ingram Case : Facts • On January 27, 2011, St. Malachy's, Steve Bristol, and his wife Conni Bristol filed a petition naming Tarbox, Tarbox's law firm, Ingram, and Ingram's employer Baird as defendants. The plaintiffs alleged negligence by Tarbox and Ingram and their respective firms. On March 7, 2011, shortly after the petition was filed, Ingram died. His wife, Donna Ingram, as executor of Ingram's estate, was substituted as a defendant on April 5, 2011. 52

Ingram Case : Facts • On January 27, 2011, St. Malachy's, Steve Bristol, and his wife Conni Bristol filed a petition naming Tarbox, Tarbox's law firm, Ingram, and Ingram's employer Baird as defendants. The plaintiffs alleged negligence by Tarbox and Ingram and their respective firms. On March 7, 2011, shortly after the petition was filed, Ingram died. His wife, Donna Ingram, as executor of Ingram's estate, was substituted as a defendant on April 5, 2011. 52

Ingram Case: Facts • Ingram and Baird initially moved to have the claims against them dismissed for failure to state a claim. They maintained they owed no duties to the beneficiaries of the Charitable Trust or the Will and that the plaintiffs' claims were barred by the economic loss doctrine. The district court denied the motion. • Baird then moved for summary judgment on July 20, 2012. Baird argued no duty to the plaintiffs existed, any duty owed was discharged by Ingram's act of supplying the necessary documents to transfer Engels's assets to the Charitable Trust, the claims were barred by the economic loss doctrine, St. Malachy's and the United Way lacked standing to bring claims, and the damages allegedly sustained were too speculative. Ingram joined Baird's motion for summary judgment. 53

Ingram Case: Facts • Ingram and Baird initially moved to have the claims against them dismissed for failure to state a claim. They maintained they owed no duties to the beneficiaries of the Charitable Trust or the Will and that the plaintiffs' claims were barred by the economic loss doctrine. The district court denied the motion. • Baird then moved for summary judgment on July 20, 2012. Baird argued no duty to the plaintiffs existed, any duty owed was discharged by Ingram's act of supplying the necessary documents to transfer Engels's assets to the Charitable Trust, the claims were barred by the economic loss doctrine, St. Malachy's and the United Way lacked standing to bring claims, and the damages allegedly sustained were too speculative. Ingram joined Baird's motion for summary judgment. 53

Ingram Case: District Court Decision • The district court issued its ruling on the motion for summary judgment on September 10, 2012. In it, the court addressed only Baird and Ingram's arguments related to duty. – The court determined neither Ingram nor Baird owed any duty to the beneficiaries of the Will or the Charitable Trust to advise Tarbox or Engels that Engels's assets were held in a Revocable Trust and needed to be moved out of that trust. – The court explained, “The Court agrees with Baird's assertion that judicial creation of a duty to beneficiaries of a client's estate or trust would lead to divided loyalties of securities registered representatives. ” – It added, “The Court simply cannot and should not create a duty for a securities registered representative that would, in any manner, require or encourage that individual to practice law without a license. ” 54

Ingram Case: District Court Decision • The district court issued its ruling on the motion for summary judgment on September 10, 2012. In it, the court addressed only Baird and Ingram's arguments related to duty. – The court determined neither Ingram nor Baird owed any duty to the beneficiaries of the Will or the Charitable Trust to advise Tarbox or Engels that Engels's assets were held in a Revocable Trust and needed to be moved out of that trust. – The court explained, “The Court agrees with Baird's assertion that judicial creation of a duty to beneficiaries of a client's estate or trust would lead to divided loyalties of securities registered representatives. ” – It added, “The Court simply cannot and should not create a duty for a securities registered representative that would, in any manner, require or encourage that individual to practice law without a license. ” 54

Ingram Case: Ia S Ct. Legal Analysis • When negligence is alleged, three factors determine whether a duty exists: “(1) the relationship between the parties, (2) reasonable foreseeability of harm to the person who is injured, and (3) public policy considerations. ” Thompson v. Kaczinski, 774 N. W. 2 d 829, 834 (Iowa 2009). • The Thompson duty analysis is not dispositive in cases that are “based on agency principles and involve[ ] economic loss. – See Langwith v. Am. Nat'l Gen. Ins. Co. , 793 N. W. 2 d 215, 221 n. 3 (Iowa 2010), superseded by statute, 2011 Iowa Acts ch. 70, § 45 (codified at Iowa Code § 522 B. 11(7) (Supp. 2011)); see also Pitts, 818 N. W. 2 d at 99 (“Since this is a case based on agency principles and involving economic harm, we will not rely on the concept of duty embodied in Thompson. ”). 55

Ingram Case: Ia S Ct. Legal Analysis • When negligence is alleged, three factors determine whether a duty exists: “(1) the relationship between the parties, (2) reasonable foreseeability of harm to the person who is injured, and (3) public policy considerations. ” Thompson v. Kaczinski, 774 N. W. 2 d 829, 834 (Iowa 2009). • The Thompson duty analysis is not dispositive in cases that are “based on agency principles and involve[ ] economic loss. – See Langwith v. Am. Nat'l Gen. Ins. Co. , 793 N. W. 2 d 215, 221 n. 3 (Iowa 2010), superseded by statute, 2011 Iowa Acts ch. 70, § 45 (codified at Iowa Code § 522 B. 11(7) (Supp. 2011)); see also Pitts, 818 N. W. 2 d at 99 (“Since this is a case based on agency principles and involving economic harm, we will not rely on the concept of duty embodied in Thompson. ”). 55

Ingram Case: Ia S Ct Legal Analysis • “While the existence of some agency relationship is not contested by the parties, the scope of that relationship is. Ingram and Baird argue Ingram was merely a securities registered representative—only able to “give incidental advice to retail investors who buy and sell securities. ” They claim Ingram never acted in the role of an estate planner or financial planner for Engels. ” 56

Ingram Case: Ia S Ct Legal Analysis • “While the existence of some agency relationship is not contested by the parties, the scope of that relationship is. Ingram and Baird argue Ingram was merely a securities registered representative—only able to “give incidental advice to retail investors who buy and sell securities. ” They claim Ingram never acted in the role of an estate planner or financial planner for Engels. ” 56

Ingram Case: Application of Law to Facts • “We believe the summary judgment record supports a conclusion that Ingram did far more than just recommend financial investments. Ingram worked with Engels's previous attorney when the Revocable Trust and the Charitable Foundation were established. ” – – – – He became a director of the Charitable Foundation. He was Engels's designated successor as the trustee of the Revocable Trust. He was the executor of Engels's original will. Ingram and Engels discussed the terms of Engels's new will and Charitable Trust before they were drafted. According to Tarbox, Ingram spoke with Tarbox three or four times and “outlin[ed] a plan” for Engels's estate before Engels had his first and only meeting with Tarbox. Ingram communicated to Tarbox the parties whom Engels wished to benefit under the Will and Charitable Trust. Ingram was to be the executor of the Will if Jerri Mc. Lane could not serve. Ingram was named cotrustee of the Charitable Trust. Ingram repeatedly wrote Engels providing forms for him to transfer the ownership of his assets to the Charitable Trust. As Ingram said to Engels, “We really need to get the [C]haritable [T]rust funded. ” 57

Ingram Case: Application of Law to Facts • “We believe the summary judgment record supports a conclusion that Ingram did far more than just recommend financial investments. Ingram worked with Engels's previous attorney when the Revocable Trust and the Charitable Foundation were established. ” – – – – He became a director of the Charitable Foundation. He was Engels's designated successor as the trustee of the Revocable Trust. He was the executor of Engels's original will. Ingram and Engels discussed the terms of Engels's new will and Charitable Trust before they were drafted. According to Tarbox, Ingram spoke with Tarbox three or four times and “outlin[ed] a plan” for Engels's estate before Engels had his first and only meeting with Tarbox. Ingram communicated to Tarbox the parties whom Engels wished to benefit under the Will and Charitable Trust. Ingram was to be the executor of the Will if Jerri Mc. Lane could not serve. Ingram was named cotrustee of the Charitable Trust. Ingram repeatedly wrote Engels providing forms for him to transfer the ownership of his assets to the Charitable Trust. As Ingram said to Engels, “We really need to get the [C]haritable [T]rust funded. ” 57

Ingram Case: Legal Conclusion • “Even though Ingram was not licensed to provide legal services, he had a general legal duty to exercise care in whatever services he did provide as Engels's agent. ” • “If an agent undertakes to perform services as a practitioner of a trade or profession, the agent “is required to exercise the skill and knowledge normally possessed by members of that profession or trade in good standing in similar communities” unless the agent represents that the agent possesses greater or lesser skill. ” 58

Ingram Case: Legal Conclusion • “Even though Ingram was not licensed to provide legal services, he had a general legal duty to exercise care in whatever services he did provide as Engels's agent. ” • “If an agent undertakes to perform services as a practitioner of a trade or profession, the agent “is required to exercise the skill and knowledge normally possessed by members of that profession or trade in good standing in similar communities” unless the agent represents that the agent possesses greater or lesser skill. ” 58

Ingram Case: Legal Conclusion • “A reasonable fact finder could conclude that Ingram was acting on Engels's behalf in developing and implementing an estate plan. Even if Ingram fell short of actually performing legal services, a fact finder could certainly determine that Ingram was serving as Engels's gobetween or intermediary with Tarbox. If Ingram failed to perform these services with due care, he could potentially be liable to Engels or his estate” 59

Ingram Case: Legal Conclusion • “A reasonable fact finder could conclude that Ingram was acting on Engels's behalf in developing and implementing an estate plan. Even if Ingram fell short of actually performing legal services, a fact finder could certainly determine that Ingram was serving as Engels's gobetween or intermediary with Tarbox. If Ingram failed to perform these services with due care, he could potentially be liable to Engels or his estate” 59

Ingram Case: NO PRIVITY REQUIRED! • “But, of course, neither Engels nor his estate is bringing this action. The plaintiffs, rather, are putative beneficiaries of the Will and the Charitable Trust. Yet, we have previously recognized that “a lawyer owes a duty of care to the direct, intended, and specifically identifiable beneficiaries of the testator as expressed in the testator's testamentary instruments. ” Schreiner, 410 N. W. 2 d at 682. ” 60

Ingram Case: NO PRIVITY REQUIRED! • “But, of course, neither Engels nor his estate is bringing this action. The plaintiffs, rather, are putative beneficiaries of the Will and the Charitable Trust. Yet, we have previously recognized that “a lawyer owes a duty of care to the direct, intended, and specifically identifiable beneficiaries of the testator as expressed in the testator's testamentary instruments. ” Schreiner, 410 N. W. 2 d at 682. ” 60

Ingram Case: • Under the facts of the Schreiner case, we determined the lawyer was “actively involved in [the will, codicil, and sale of the property] and [was] fully aware of [the client's] intent to leave Schreiner an interest in the property. ” However, the lawyer never explained to the client “what effect the sale would have on her testamentary intent or redrafted her codicil to insure Schreiner would receive a portion of the proceeds from the partition sale, ” and as a result, nothing passed to Schreiner under the will. • While we stated that “in most cases, the post-will disposition of property will give rise to no cause of action” because “[n]o lawyer reasonably can be expected to keep track of the provisions in the wills of his or her clients, nor the effect on those instruments caused by changes in the clients' affairs, ” we determined Schreiner had alleged 61 sufficient facts to avoid dismissal.

Ingram Case: • Under the facts of the Schreiner case, we determined the lawyer was “actively involved in [the will, codicil, and sale of the property] and [was] fully aware of [the client's] intent to leave Schreiner an interest in the property. ” However, the lawyer never explained to the client “what effect the sale would have on her testamentary intent or redrafted her codicil to insure Schreiner would receive a portion of the proceeds from the partition sale, ” and as a result, nothing passed to Schreiner under the will. • While we stated that “in most cases, the post-will disposition of property will give rise to no cause of action” because “[n]o lawyer reasonably can be expected to keep track of the provisions in the wills of his or her clients, nor the effect on those instruments caused by changes in the clients' affairs, ” we determined Schreiner had alleged 61 sufficient facts to avoid dismissal.

Ingram Case: • The duty we imposed in Schreiner was extended in Holsapple v. Mc. Grath to include the specifically identifiable beneficiaries of nontestamentary instruments. 521 N. W. 2 d 711, 713– 14 (Iowa 1994) (beneficiaries who didn’t receive real estate because quitclaim deed was defective because notarized could sue the attorney who drafted the defective deed, even though he wasn’t their attorney, because the donee who sued was “specifically identified, by the donor, as an object of the grantor's intent” and “the expectancy was lost or diminished as a result of professional negligence. ” • The plaintiff had to show that the client “attempted to put the donative wishes into effect and failed to do so only because of the intervening negligence of a lawyer. ” 62

Ingram Case: • The duty we imposed in Schreiner was extended in Holsapple v. Mc. Grath to include the specifically identifiable beneficiaries of nontestamentary instruments. 521 N. W. 2 d 711, 713– 14 (Iowa 1994) (beneficiaries who didn’t receive real estate because quitclaim deed was defective because notarized could sue the attorney who drafted the defective deed, even though he wasn’t their attorney, because the donee who sued was “specifically identified, by the donor, as an object of the grantor's intent” and “the expectancy was lost or diminished as a result of professional negligence. ” • The plaintiff had to show that the client “attempted to put the donative wishes into effect and failed to do so only because of the intervening negligence of a lawyer. ” 62

Ingram Case: • Intended beneficiaries of life insurance policies can sue life insurance agents under the same theory, if a beneficiary designation fails because it is negligently drawn up by the agent. In Pitts, the Supreme Court extended Schreiner to insurance agents, holding that an insurer owes a duty to the beneficiary if the beneficiary can “show that he or she was the ‘direct, intended, and specifically identifiable beneficiar[y]’ of the policy as well as the other elements of negligence. ” The Court stated, however, that the beneficiary must “point to evidence in the written instrument itself that identifies her as the intended beneficiary of the entire policy. ” (Pitts has been abrogated in part by statute). 63

Ingram Case: • Intended beneficiaries of life insurance policies can sue life insurance agents under the same theory, if a beneficiary designation fails because it is negligently drawn up by the agent. In Pitts, the Supreme Court extended Schreiner to insurance agents, holding that an insurer owes a duty to the beneficiary if the beneficiary can “show that he or she was the ‘direct, intended, and specifically identifiable beneficiar[y]’ of the policy as well as the other elements of negligence. ” The Court stated, however, that the beneficiary must “point to evidence in the written instrument itself that identifies her as the intended beneficiary of the entire policy. ” (Pitts has been abrogated in part by statute). 63

Ingram Case: • “The present question is whether a financial planner should be treated similarly to an attorney or an insurance agent. That is, if a written instrument executed by the deceased principal specifically identifies the plaintiff as an intended beneficiary, but due to the agent's negligence the decedent's plan as set forth in the instrument is defeated, can the beneficiary sue? We see no reason to treat one kind of agent differently from another, so long as the plaintiffs are direct, intended, and specifically identifiable beneficiaries. ” 64

Ingram Case: • “The present question is whether a financial planner should be treated similarly to an attorney or an insurance agent. That is, if a written instrument executed by the deceased principal specifically identifies the plaintiff as an intended beneficiary, but due to the agent's negligence the decedent's plan as set forth in the instrument is defeated, can the beneficiary sue? We see no reason to treat one kind of agent differently from another, so long as the plaintiffs are direct, intended, and specifically identifiable beneficiaries. ” 64

Ingram Case: • “Logic and fairness support this result. Both Tarbox and Ingram were involved with Engels's estate plan, but their respective roles are disputed. As we have discussed above, within the scope of their respective agencies, both Tarbox and Ingram generally owed duties of due care. ” • “Baird acknowledged at oral argument that this would be a different case if Ingram had been licensed as an attorney or a certified public accountant. To some extent, this concession undermines Ingram and Baird's position, because the lack of a professional license is not generally viewed as a stop sign for legal liability. ” 65

Ingram Case: • “Logic and fairness support this result. Both Tarbox and Ingram were involved with Engels's estate plan, but their respective roles are disputed. As we have discussed above, within the scope of their respective agencies, both Tarbox and Ingram generally owed duties of due care. ” • “Baird acknowledged at oral argument that this would be a different case if Ingram had been licensed as an attorney or a certified public accountant. To some extent, this concession undermines Ingram and Baird's position, because the lack of a professional license is not generally viewed as a stop sign for legal liability. ” 65

Ingram Case: Holding • “For the foregoing reasons, we hold that when an agent negligently performs his or her duties to a principal, and as a result of that negligence a direct, intended, and specifically identifiable beneficiary of a written instrument executed by the principal does not receive the benefits set forth in the written instrument, the beneficiary is owed a duty by the agent and may have a cause of action against him or her. ” • “We conclude, therefore, that the district court should not have entered summary judgment against Bristol based on the absence of a legal duty. For reasons that we discuss below, however, it is unnecessary for us to decide whether St. Malachy's or the United Way were also direct, intended, and specifically identifiable beneficiaries that were owed a similar duty by Ingram and Baird. ” 66

Ingram Case: Holding • “For the foregoing reasons, we hold that when an agent negligently performs his or her duties to a principal, and as a result of that negligence a direct, intended, and specifically identifiable beneficiary of a written instrument executed by the principal does not receive the benefits set forth in the written instrument, the beneficiary is owed a duty by the agent and may have a cause of action against him or her. ” • “We conclude, therefore, that the district court should not have entered summary judgment against Bristol based on the absence of a legal duty. For reasons that we discuss below, however, it is unnecessary for us to decide whether St. Malachy's or the United Way were also direct, intended, and specifically identifiable beneficiaries that were owed a similar duty by Ingram and Baird. ” 66

Sidenote: Charities Damages Too Speculative • Bristol had standing to sue, because he would have received the house had no error been made • St. Malachy and the United Way, however, could not sue, because their damages were too speculative (the trustees of the charitable trust were not required to distribute anything to them, and could choose among numerous charities in making distributions). – Keep in mind that the trustees of the charitable trust who wielded this “vast unbridled discretion” to choose charitable beneficiaries of the trust potentially included Ingram, the subject of the suit. The Court did not mention that fact. – Is it ethical to name oneself as a trustee of a charitable trust, with such broad authority that nobody can challenge one’s actions? – Would the Trustees in this case have a duty to bring suit? Ingram? – Is it ethical to require in the document that an advisor named as a trustee of a charitable trust be paid for trustee services in such a context? 67

Sidenote: Charities Damages Too Speculative • Bristol had standing to sue, because he would have received the house had no error been made • St. Malachy and the United Way, however, could not sue, because their damages were too speculative (the trustees of the charitable trust were not required to distribute anything to them, and could choose among numerous charities in making distributions). – Keep in mind that the trustees of the charitable trust who wielded this “vast unbridled discretion” to choose charitable beneficiaries of the trust potentially included Ingram, the subject of the suit. The Court did not mention that fact. – Is it ethical to name oneself as a trustee of a charitable trust, with such broad authority that nobody can challenge one’s actions? – Would the Trustees in this case have a duty to bring suit? Ingram? – Is it ethical to require in the document that an advisor named as a trustee of a charitable trust be paid for trustee services in such a context? 67

Afterward: Ingram abrogated at least in part with respect to some Insurance Agents • • Iowa Supreme Court decides Ingram, December 27, 2013 Iowa Supreme Court denies request for rehearing of Ingram: February 11, 2014 HF 398 Introduce March 4, 2014 HF 398 Passed House March 11, 2014 HF 398 Passed Senate May 1, 2014 HF 398 Signed into law by Governor May 23, 2014 Amends, inter alia, Iowa Code Subsection 522 B. 11(7). 68

Afterward: Ingram abrogated at least in part with respect to some Insurance Agents • • Iowa Supreme Court decides Ingram, December 27, 2013 Iowa Supreme Court denies request for rehearing of Ingram: February 11, 2014 HF 398 Introduce March 4, 2014 HF 398 Passed House March 11, 2014 HF 398 Passed Senate May 1, 2014 HF 398 Signed into law by Governor May 23, 2014 Amends, inter alia, Iowa Code Subsection 522 B. 11(7). 68

What Subsection 522 B. 11(7) already provided: 7. a. Unless an insurance producer holds oneself out as an insurance specialist, consultant, or counselor and receives compensation for consultation and advice apart from commissions paid by an insurer, the duties and responsibilities of an insurance producer are limited to those duties and responsibilities set forth in Sandbulte v. Farm Bureau Mut. Ins. Co. , 343 N. W. 2 d 457 (Iowa 1984). b. The general assembly declares that the holding of Langwith v. Am. Nat’l Gen. Ins. Co. , (No. 08 -0778) (Iowa 2010) is abrogated to the extent that it overrules Sandbulte and imposes higher or greater duties and responsibilities on insurance producers than those set forth in Sandbulte. 69

What Subsection 522 B. 11(7) already provided: 7. a. Unless an insurance producer holds oneself out as an insurance specialist, consultant, or counselor and receives compensation for consultation and advice apart from commissions paid by an insurer, the duties and responsibilities of an insurance producer are limited to those duties and responsibilities set forth in Sandbulte v. Farm Bureau Mut. Ins. Co. , 343 N. W. 2 d 457 (Iowa 1984). b. The general assembly declares that the holding of Langwith v. Am. Nat’l Gen. Ins. Co. , (No. 08 -0778) (Iowa 2010) is abrogated to the extent that it overrules Sandbulte and imposes higher or greater duties and responsibilities on insurance producers than those set forth in Sandbulte. 69

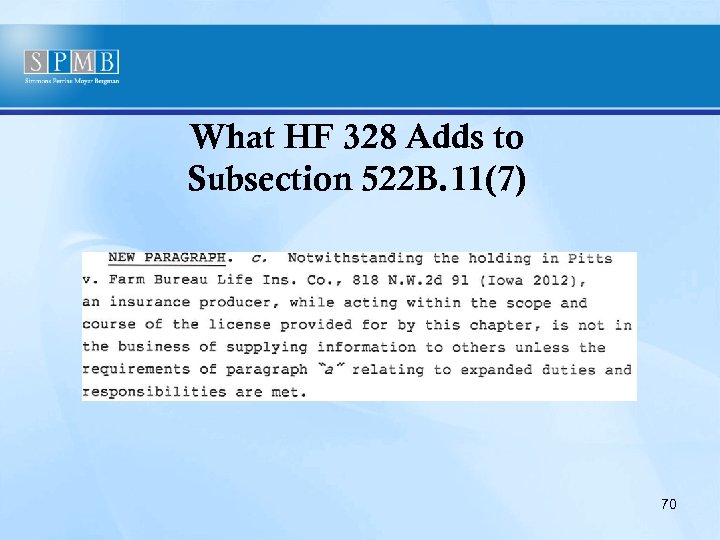

What HF 328 Adds to Subsection 522 B. 11(7) 70

What HF 328 Adds to Subsection 522 B. 11(7) 70

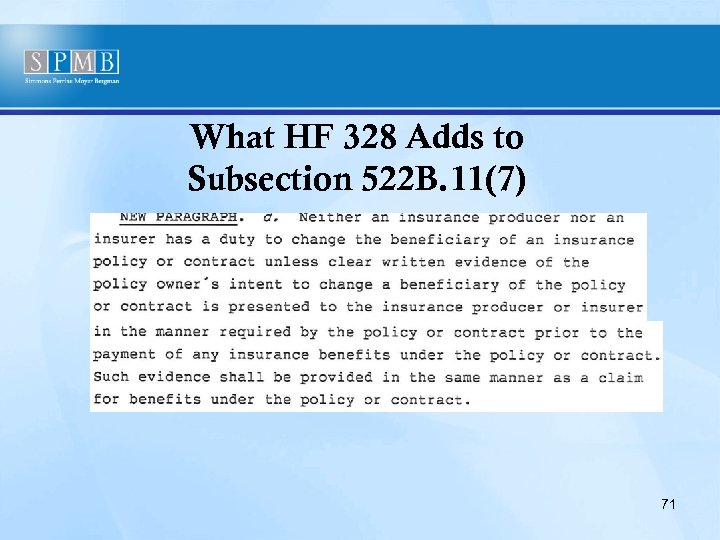

What HF 328 Adds to Subsection 522 B. 11(7) 71

What HF 328 Adds to Subsection 522 B. 11(7) 71

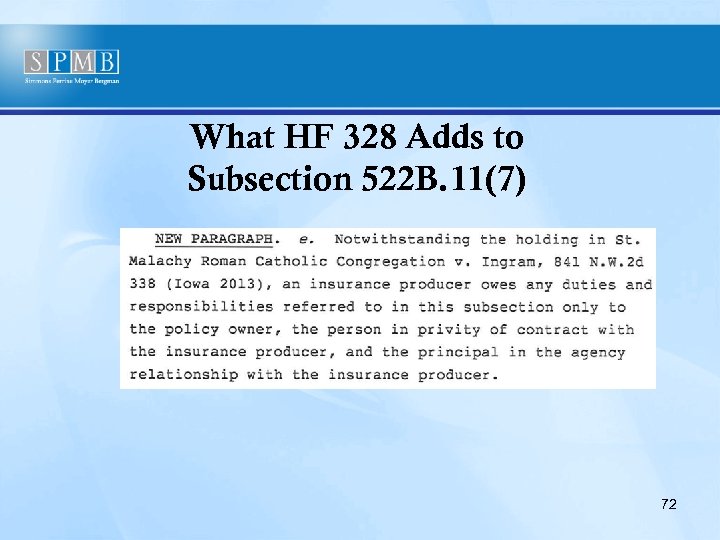

What HF 328 Adds to Subsection 522 B. 11(7) 72

What HF 328 Adds to Subsection 522 B. 11(7) 72

Questions? • What if an insurance agent also sells securities or gives fee-based investment advice? • What if an insurance agent teams with others in his or her company who provide non-insurance services including estate planning advice? • How does HF 328 intersect with the prohibition against the unauthorized practice of law, and what happens if an insurance agent strays over that line? 73

Questions? • What if an insurance agent also sells securities or gives fee-based investment advice? • What if an insurance agent teams with others in his or her company who provide non-insurance services including estate planning advice? • How does HF 328 intersect with the prohibition against the unauthorized practice of law, and what happens if an insurance agent strays over that line? 73

Sources: Ø Primary Resources: Ø Statute: Iowa Code Section 522 B. 11(7) Ø Cases: Ø Iowa Supreme Court Comm'n on Unauthorized Practice of Law v. Sturgeon, 635 N. W. 2 d 679, 680 (Iowa 2001); Ø St. Malachy Roman Catholic Congregation of Geneseo v. Ingram, 841 N. W. 2 d 338, 340 (Iowa 2013), reh'g denied (Feb. 11, 2014); Ø Comm. on Prof'l Ethics & Conduct of the Iowa State Bar Ass'n v. Baker, 492 N. W. 2 d 695, 696 (Iowa 1992). Ø Formal Opinions: Ø Committee on Professional Ethics and Conduct of the Iowa State Bar Association, Formal Opinion 90 -32. 74

Sources: Ø Primary Resources: Ø Statute: Iowa Code Section 522 B. 11(7) Ø Cases: Ø Iowa Supreme Court Comm'n on Unauthorized Practice of Law v. Sturgeon, 635 N. W. 2 d 679, 680 (Iowa 2001); Ø St. Malachy Roman Catholic Congregation of Geneseo v. Ingram, 841 N. W. 2 d 338, 340 (Iowa 2013), reh'g denied (Feb. 11, 2014); Ø Comm. on Prof'l Ethics & Conduct of the Iowa State Bar Ass'n v. Baker, 492 N. W. 2 d 695, 696 (Iowa 1992). Ø Formal Opinions: Ø Committee on Professional Ethics and Conduct of the Iowa State Bar Association, Formal Opinion 90 -32. 74

Thank You Paul Morf (319)366 -7641 pmorf@simmonsperrine. com http: //www. simmonsperrine. com/our-attorneys/paul-p-morf 75

Thank You Paul Morf (319)366 -7641 pmorf@simmonsperrine. com http: //www. simmonsperrine. com/our-attorneys/paul-p-morf 75