c6a59ca8eb0c4b0530546c11fd52786a.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 48

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN PATENT PRACTICE 2013 ©Robert Levy 2013

WHAT’S NEW • Effective March 16, 2013, the first inventor- to-file provisions became effective. • Effective May 3, 2013, the USPTO adopted new rules for Professional Responsibility. • U. S. Supreme Court holds that state courts have jurisdiction over legal malpractice in IP matters. • Inequitable Conduct has become harder to establish. 2

NEW PTO RULES- 37 C. F. R. § 1. 78 Claiming the Benefit of an Earlier Filing Date (a)(6) If a non-provisional application filed on or after March 16, 2013 claims the benefit of a provisional application filed prior to March 16, 2013, the applicant must provide a statement identifying a first claim having an effective filing date after March 16, 2013. The applicant does not have to provide a statement if the applicant reasonably believes that the non-provisional application does not now and never did contain any claim having an effective filing date on or after March 16, 2013. (Applicant can rescind an erroneous statement. ) 3

USPTO Rules of Professional Responsibility • The USPTO has now adopted a version of the ABA Model Rules of Professional Responsibility, (37 C. F. R. § 11. 1 et seq. ) replacing the ABA Model Code of Professional Responsibility. • The ABA Model Rules of Professional Rules of Responsibility have been adopted in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. • The adoption of the new Rules of Professional Responsibility is not intended to impose significantly new standards of conduct on patent practitioners but to conform the USPTO Rules of Professional Responsibility to those adopted by the states. • The adoption of new Rules of Professional Responsibility will benefit practitioners by allowing reference to interpretations by the states. However, such interpretations will not bind the USPTO. 4

37 C. F. R. § 11. 1 - Definitions Fraud or fraudulent means conduct that involves a misrepresentation of material fact made with intent to deceive or a state of mind so reckless respecting consequences as to be the equivalent of intent, where there is justifiable reliance on the misrepresentation by the party deceived, inducing the party to act thereon, and where there is injury to the party deceived resulting from reliance on the misrepresentation. Fraud also may be established by a purposeful omission or failure to state a material fact, which omission or failure to state makes other statements misleading, and where the other elements of justifiable reliance and injury are established. (Different than the ABA Model Rules definition) 5

37 C. F. R. § 11. 106 - Confidentiality of Information (a) A practitioner shall not reveal information relating to the representation of a client unless the client gives informed consent, the disclosure is impliedly authorized in order to carry out the representation, the disclosure is permitted by paragraph (b) of this section, or the disclosure is required by paragraph (c) of this section. (b) A practitioner may reveal information relating to the representation of a client to the extent the practitioner reasonably believes necessary: (1) To prevent reasonably certain death or substantial bodily harm; (2) To prevent the client from engaging in inequitable conduct before the Office or from committing a crime or fraud that is reasonably certain to result in substantial injury to the financial interests or property of another and in furtherance of which the client has used or is using the practitioner’s services; 6

37 C. F. R. § 11. 106 Confidentiality of Information (continued) (3) To prevent, mitigate or rectify substantial injury to the financial interests or property of another that is reasonably certain to result or has resulted from the client’s commission of a crime, fraud, or inequitable conduct before the Office in furtherance of which the client has used the practitioner’s services; (4) To secure legal advice about the practitioner’s compliance with the USPTO Rules of Professional Conduct; (5) To establish a claim or defense on behalf of the practitioner in a controversy between the practitioner and the client, to establish a defense to a criminal charge or civil claim against the practitioner based upon conduct in which the client was involved, or to respond to allegations in any proceeding concerning the practitioner’s representation of the client; or (supersede duty of loyalty? ) (6) To comply with other law or a court order. (c) A practitioner shall disclose to the Office information necessary to comply with applicable duty of disclosure provisions. 7

37 C. F. R. § 11. 303 - Candor Toward The Tribunal (a) A practitioner shall not knowingly: (1) Make a false statement of fact or law to a tribunal or fail to correct a false statement of material fact or law previously made to the tribunal by the practitioner; (2) Fail to disclose to the tribunal legal authority in the controlling jurisdiction known to the practitioner to be directly adverse to the position of the client and not disclosed by opposing counsel in an inter partes proceeding, or fail to disclose such authority in an ex parte proceeding before the Office if such authority is not otherwise disclosed; or (3) Offer evidence that the practitioner knows to be false. If a practitioner, the practitioner’s client, or a witness called by the practitioner, has offered material evidence and the practitioner comes to know of its falsity, the practitioner shall take reasonable remedial measures, including, if necessary, disclosure to the tribunal. A practitioner may refuse to offer evidence that the practitioner reasonably believes is false. 8

37 C. F. R. § 11. 303 Candor Toward The Tribunal (continued) (b) A practitioner who represents a client in a proceeding before a tribunal and who knows that a person intends to engage, is engaging or has engaged in criminal or fraudulent conduct related to the proceeding shall take reasonable remedial measures, including, if necessary, disclosure to the tribunal. (c) The duties stated in paragraphs (a) and (b) of this section continue to the conclusion of the proceeding, and apply even if compliance requires disclosure of information otherwise protected by § 11. 106. 9

Gunn v. Minton 2013 WL 610193 (U. S. February 20, 2013) Minton procured a patent for a computer-aided technique for securities trading. Gunn, representing Minton, sued NASDAQ for patent infringement. The District Court held Minton’s patent invalid under 35 U. S. C. § 102(b) because Minton had leased his security trading technique more than one year prior to his filing date. Gunn moved for reconsideration, arguing experimental use. The district court denied Gunn’s motion. The Federal Circuit affirmed, holding that Minton had waived his right to argue experimental use. Minton then sued his attorney Gunn for malpractice. The Texas trial court rejected Minton’s malpractice claim. Minton appealed, arguing that the state court’s decision should be vacated because the federal courts have exclusive jurisdiction over patent law matters under 35 U. S. C. § 1338(a). The Texas Supreme Court agreed, holding that Minton’s claim involved a substantial federal issue sufficient to trigger federal jurisdiction under 35 U. S. C. § 1338(a). 10

Gunn v. Minton (continued) In a unanimous decision, the U. S. Supreme Court reversed and remanded the case. Chief Justice Roberts, speaking for the Court, noted that federal jurisdiction would arise if the state law claim raised a substantial federal issue. Minton’s malpractice claim did not raise a substantial federal issue because the issue here did not have importance to the federal system as a whole. The malpractice issue in this case had no particular significance to the federal government and would not impact federal patent litigation. In reaching its decision, the Court balanced the federal interest in the patent system against the traditional role state courts have in regulating lawyers and legal practice. The Court noted that state malpractice claims based on a patent matter, rarely if ever would arise under federal patent law. 11

Therasense, Inc. vs. Becton Dickinson and Company 649 F. 3 d 1276 (Fed. Cir. 2011) Abbott, the successor-in-interest to Therasense, sued Becton Dickinson for infringement of US Patent 5, 820, 551 for a test strip. In the course of prosecuting the ‘ 551 patent, Abbott made inconsistent arguments regarding the teachings of its prior art ‘ 382 patent in the USPTO as compared to those made by Abbott in the EPO regarding its European application corresponding to its ‘ 382 patent. The District Court held the ‘ 551 patent unenforceable because Abbott did not disclose to the USPTO the arguments Abbott made in the EPO. In 2010, a three-judge panel of the CAFC (Linn, Friedman and Dyk), by a 2 -1 vote, affirmed the finding of unenforceability. Abbott then petitioned for an en banc review which was granted. 12

The CAFC En Banc Decision Judge Rader, writing for the majority (Newman, Lourie, Linn, Moore, and Reyna), held the following: The materiality required to establish inequitable conduct is “but for” materiality. When an applicant fails to disclose prior art to the PTO, that prior art is “but for” material if the PTO would not have allowed a claim had it been aware of the undisclosed prior art (using the preponderance of evidence standard). An exception to the “but for” materiality test is affirmative egregious misconduct (e. g. , false affidavits). The CAFC will no longer not adopt the materiality test in 37 C. F. R. § 1. 56. 13

THE CAFC En Banc DECISION (continued) Inequitable conduct requires findings of intent to deceive and materiality, both of which must be proved by clear and convincing evidence (Star Scientific). To prevail on inequitable conduct, the accused infringer must prove that the patentee acted with the specific intent to deceive. The accused must prove that the applicant knew of the reference, that the reference was material, and that the applicant made a deliberate decision to withhold it. The intent to deceive must be only or single most reasonable inference that can be drawn from the evidence. 14

In re ROSUVASTATIN CALCIUM PATENT LITIGATION. 703 F. 3 d 511 (Fed. Cir 2012) Patentee brought suit for infringement of its ‘ 314 reissue patent for the Crestor® cholesterol-reducing drug following defendant’s challenge to the validity of the patent under the Hatch-Waxman Act. The Defendants argued that the ′ 314 reissue patent was unenforceable due to inequitable conduct committed during prosecution of the parent patent because of the failure of patentee’s staff to disclose certain documents to the PTO. The district court found the uncited references material, but that patentee’s employees had acted without specific deceptive intent. On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed. Defendants had not established, by clear and convincing evidence, that patentee’s employees made a deliberate decision to withhold the references from the USPTO. 15

In re ROSUVASTATIN CALCIUM PATENT LITIGATION (cont. ) 703 F. 3 d 511 (Fed. Cir 2012) “Inequitable conduct requires that the accused infringer must prove that the patentee acted with the specific intent to deceive the PTO. ” “Recognizing the complexity of patent prosecution, negligence—even gross negligence—is insufficient to establish deceptive intent. ” See Kingsdown, 863 F. 2 d at 876 (“a finding that particular conduct amounts to ‘gross negligence’ does not of itself justify an inference of intent to deceive”); Lazare Kaplan Int’l, Inc. v. Photoscribe Techs. , Inc. , 628 F. 3 d 1359, 1379 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (“mistake or exercise of poor judgment. . . does not support an inference of intent to deceive”) (703 F. 3 d 511 at 526). 16

NOVO NORDISK A/S v. CARACO PHARMACEUTICAL LABORATORIES, LTD . 2013 WL 2991060 (Fed. Cir. June 18, 2013) Plaintiff sued defendant for infringing plaintiff’s patent for a method for treating non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (“NIDDM” or “Type II diabetes”) following defendant’s challenge to the validity of the patent under the Hatch-Waxman Act. Defendant alleged plaintiff committed inequitable conduct by (a) omitting certain opinions of Dr. Sturgis as well as his failure to tell the PTO that some of his reported results were not part of his original test protocol; and (b) Dr. Bork’s assertion that Dr. Sturgis’s data provided “clear evidence of synergy, ” and his failure to disclose certain e-mails that allegedly refuted this statement. The district court found Dr. Sturgis’s omissions constituted inequitable conduct. The Federal circuit reversed the inequitable conduct finding. First, Dr. Sturgis’s omissions were not “but for” material. Likewise, the statements and omissions by Dr. Bork, while troubling, are also not “but for” material. 17

MEYER INTELLECTUAL PROPERTIES LIMITED v. BODUM, INC. 690 F. 3 d 1354 (Fed. Cir. 2012) Patent owner sued Bodum alleging infringement of patents for a method for frothing liquids such as milk. Defendant counterclaimed alleging patentee committed inequitable conduct. The district court granted plaintiff’s motion in limine to preclude Bodum from arguing that the inventor engaged in inequitable conduct in obtaining the patents-in-suit. Specifically, the district court found that Bodum’s inequitable conduct charge failed to meet the demanding requirements of materiality and intent. The Federal Circuit reversed, holding that the district court erred in addressing the sufficiency of Bodum’s inequitable conduct defense on an evidentiary motion. In doing so, the district court did not allow for full development of the evidence and deprived Bodum of an opportunity to present all pertinent material to defend against the dismissal of its inequitable conduct defense. 18

SANTARUS, INC. v. PAR PHARMACEUTICAL, INC. 694 F. 3 d 1344 (Fed. Cir. 2012) Plaintiff sued defendant for infringing plaintiff’s patent for benzimidazole proton pump inhibitors (PPI) (Zegerid®) following defendant’s challenge to the validity of the patent under the Hatch. Waxman Act. Defendant argued that the inventor, Dr. Phillips, should have informed the PTO regarding the uncoated PPI formulation administered to some hospital patients during the prosecution of the parent application. Further, defendant argued Dr. Phillips submitted a misleading declaration regarding an experiment he had conducted. The district court determined that the inventor had not committed inequitable conduct and the Federal Circuit affirmed. Defendant had failed to show by clear and convincing evidence that the inventor had the specific intent to deceive necessary to establish inequitable conduct. 19

PARKERVISION, INC. , v. QUALCOMM INCORPORATED 2013 WL 230179 (M. D. Fla. , Jan. 2013) ‘ Parkervision sued Qualcomm for infringing Parkervision’s patents related to wireless communication. Qualcomm counterclaimed that Parkervision’s patents were unenforceable because of inequitable conduct. In support of its inequitable conduct counterclaim, Qualcomm argued that Parkervision (1) “buried” the Patent and Trademark Office with references; (2) belatedly disclosed a material reference to the PTO; and (3) materially misrepresented four references to the PTO. Qualcomm’s claim of inequitable conduct for burying references failed because Qualcomm did not show that the intent to deceive was the only or single most reasonable inference to be drawn from the disclosure of voluminous references to the PTO. Qualcomm also failed to show that the belatedly disclosed reference was “but for” material. Qualcomm could proceed with its misrepresentation claim, but only under strict court scrutiny. 20

EVONIK DEGUSSA GMBH, v. MATERIA INC. 2012 WL 4503771 (D. Del. , October, 2012) Evonik Degussa sued Materia Inc. for willfull infringement of U. S. Patents 7, 378, 528 and 7, 652, 145. University of New Orleans Foundation (UNOF), a third party plaintiff, claimed infringement of its ‘ 590 patent by Evonik who counterclaimed inequitable conduct. Evonik argued that UNOF withheld information from the PTO regarding co-inventor Nolan’s derivation of work from Nolan’s time spent with Professor Robert Grubbs at the University of California. In response to UNOF’s motion to dismiss Evonik’s inequitable conduct defense, the court held that Evonik had satisfied the requirement to plead inequitable conduct with particularity. Evonik plead that the PTO would not have allowed the patent to be issued had it known of Materia’s prior challenges to Nolan’s inventorship, thus alleging “but for” materiality. (Materia had initially challenged the ‘ 590 patent but later obtained a license from UNOF. ) 21

SENJU PHARMACEUTICAL CO. , LTD. , v. APOTEX, INC. 2013 WL 444928 (D. Del. , Feb, 6, 2013) Defendant filed an abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) for Zymaxid® ophthalmic solution. Senju, owner of the patent, responded by charging the defendant with infringement. Defendant alleged patentee committed inequitable conduct by failing to recite material references. Plaintiff moved to strike defendant’s affirmative defense of inequitable conduct because defendant had not identified specific individual(s) who both knew of the invalidating information and had a specific intent to deceive the PTO. The court granted the plaintiff’s motion to strike. 22 “[T]o plead the circumstances of inequitable conduct with the requisite particularity under Rule 9(b), the pleading must identify the specific who, what, when, where, and how of the material misrepresentation or omission committed before the PTO. Exergen, 575 F. 3 d at 1328; see also Evonik Degussa, 2012 WL 4503771, at *6”

Co. Star Realty Information, Inc. v. CIVIX-DDI, LLC. 2013 WL 2151548 (N. D. Ill. , May 2013) Patentee Civix-DDI sued Co. Star for infringement of patents claiming methods to locate points of interest in a particular geographical region by accessing a database from a remote location. Co. Star responded by arguing that patentee had committed inequitable conduct by failing to disclose material prior art during prosecution and by failing to disclose prior litigation. The district court granted patentee’s motion to strike the majority of defendant’s inequitable conduct defenses. Defendant’s pleadings provided no detail about which claims were allegedly invalidated, why such claims would have been invalidated by the prior art, and how the PTO would have used the information to assess the patentability of the patents in suit. 23

GENERAL ELECTRIC COMPANY, v. MITSUBISHI HEAVY INDUSTRIES LTD. 2013 WL 2338345 (N. D. Texas, May 28, 2013) GE sued Mitsubishi for infringement of US Patent 7, 629, 705 related to voltage control in wind turbines. Mitsubishi alleged that GE committed inequitable conduct by failing to disclose a large number of prior art patents and publications as well as past public use by GE. The district court found that Mitsubishi had satisfied its burden of proof showing that the art withheld was material and that various individuals at GE, who had a duty to disclose such art, had not done so. However, the court held that Mitsubishi had not shown that GE had made a deliberate decision to withhold the information. “There is insufficient evidence that GE fully appreciated the materiality and made a deliberate effort to withhold it from the PTO. ” 24

SHIELDMARK, INC. , CREATIVE SAFETY SUPPLY, LLC, et al. , 2012 WL 6824003 (N. D. Ohio, Oct. 9, 2012) Shield. Mark sued CSS for patent infringement, trademark and service mark infringement, unfair competition, and deceptive trade practices. CSS counterclaimed, alleging inequitable conduct because Shield. Mark fraudulently relied on information not originally submitted with the original application to obtain approval of the patent. CSS also brought an action against Shieldmark’s patent counsel asserting inequitable conduct. The court denied the claims of CSS against Shieldmark’s patent counsel for inequitable conduct. 25 “By its nature, this remedy—barring enforcement of the patent—lies against only the patent holder, as enforcement of a particular patent is the right of the patent holder, or patentee. ” See 35 U. S. C. § 281 (“A patentee shall have remedy by civil action for infringement of his patent. There is no remedy against other parties. ”

CUTSFORTH, INC. , v. LEMM LIQUIDATING COMPANY, LLC 2013 WL 2455979 (D. Minnesota, June 6, 2013) Cutsforth sued Lemm Liquidating alleging infringement of U. S. Patents 7, 141, 906 (the “′ 906 Patent”) and 7, 122, 935 (the “′ 935 Patent”), as well as the ′ 354, ′ 018, and ′ 014 Patents. Lemm Liquidating counterclaimed that 354, ′ 018, and ′ 014 patents were unenforceable for inequitable conduct because of Cutsforth’s failure to disclose to the PTO prior litigation with Lemm Liquidating regarding the ‘ 906 and ‘ 935 patents, as well as invalidity claim charts regarding those patents. Plaintiff Cutsforth moved to dismiss the inequitable conduct counterclaims. The court denied Cutsforth’s motion to dismiss. The court determined that Defendants had plausibly alleged that the invalidity claim charts were material and that Cutsforth did not disclose the 2007 Litigation or the claim charts in an effort to deceive the USPTO. 26

Everlight Electronics Co. , Ltd. v. Nichia Corp. 907 F. Supp. 2 d 866 (E. D. Mich. 2012) Everlight Electronics Co. sought declaratory judgment of noninfringement, invalidity, and unenforceability of Nichia’s US Patents 5, 998, 925 (the “ ′ 925 Patent”) and 7, 531, 960 (the “ ′ 960 Patent”). Everlight alleged that Nichia never made the phosphor light emitting diodes described and claimed in their ‘ 925 patent because their process was incapable of doing so. As part of their pleading, Everlight identified the two named inventors and other persons (not named) working with the inventors as the individuals who committed inequitable conduct. Since the inventors had signed declarations as to the truthfulness of their statements in the application, Everlight argued that the production and testing of the LEDs using fictitious phosphors constituted affirmative deception. The court granted Nichia’s motion to dismiss Everlight’s claims for declaratory judgment of unenforceability of Nichia’s Patents. 27

Everlight Electronics Co. , Ltd. v. Nichia Corp. (cont. ) “The Court is not persuaded that Everlight has identified the “who” of the material misrepresentations because they have not identified “the specific individual associated with the filing or prosecution of [Nichia’s patents-in-suit] who both knew of the material information and deliberately withheld or misrepresented it. ” Exergen, 575 F. 3 d at 1329. “Everlight’s reliance on the inventors’ declaration does not provide sufficient facts for this Court to infer that a specific inventor had the requisite knowledge of the alleged falsity set forth in examples 8 and 12 of the ′ 925 Patent. The inventors do not declare that they have knowledge of all the information set forth in the ′ 925 Patent specification, rather they attest “that all statements made herein of my own knowledge are true and that all statements made on information and belief are believed to be true. . ” 28

Kimberly-Clark Worldwide, Inc. v. First Quality Baby LLC. 2012 WL 5931790 (E. D. Wisc. , November 27, 2012) Kimberly–Clark Worldwide sued First Quality Baby Products for infringement of various K–C patents related to disposable training pants. First Quality argued that plaintiff’s failure to timely produce documents related to the machinery which inventors modified to yield the patented invention constituted “unclean hands” which should render the patents in suit unenforceable. The district court dismissed defendant’s defense of unclean hands, noting 29 “Belated disclosure of documents prior to the close of discovery can hardly be described as a systematic suppression of evidence amounting to particularly egregious misconduct that warrants a dismissal of the entire suit. Therefore, First Quality’s assertion of unclean hands necessarily fails on the merits. ”

Formax Inc. v. Alkar-Rapidpak-MP Equipment Inc. 2013 WL 2368824 (E. D. Wisc. , May 29, 2013) Formax Inc. asserted that several food patty molding machines and related products sold by Alkar–Rapidpak–MP Equipment, Inc. and Tomahawk Manufacturing, Inc. infringed Formax’s U. S. Patents 4, 996, 743, 7, 318, 723, and 7, 591, 644. Defendants sought leave to amend their answer to add an affirmative defense and counterclaim of inequitable conduct against Formax for withholding material information about Formax’s own prior art machines from the USPTO during the prosecution of the ′ 723 patent. The court granted defendant’s motion. “Therefore, even though amendment to add an inequitable conduct claim at this late stage in the proceedings is discouraged, Defendants have met their burden here. Because the proposed amendment does not appear futile, and because Defendants have made a sufficient showing to satisfy the court there is good cause to insert an inequitable conduct claim into the litigation, the motion to amend will be granted. ” 30

Smith & Nephew, Inc. v. Interlace Medical, Inc. 2013 WL 3289085 (D. Mass, June 27, 2013) Patentee brought an action against the defendant alleging infringement of patents relating to surgical instruments. Defendants moved for judgment based on inequitable conduct. Defendants alleged that the patentee misrepresented the scope of the invention by contending that the invention included an outlet channel when outlet channels existed in prior-art endoscopes. (probably to avoid the need to prove “but-for” materiality. ) The court found that while the patentee’s description was somewhat misleading, patentee’s ambiguous misrepresentations did not present an extraordinary circumstance of affirmative egregious misconduct. As such, the defendants’ claims of inequitable conduct failed. 31

Carpenter Technology Corp. v. Allegheny Technologies, Inc. 2013 WL 2250121 (E. D. Pennsylvania, May 22, 2013) Plaintiff Carpenter sought declaratory judgment that ATI patents for producing nickel-based super alloys were invalid. Plaintiff later filed an amended complaint to allege that ATI’s patents were unenforceable for inequitable conduct. Plaintiff Carpenter alleged two acts of inequitable conduct: 1) Inventors’ failure to disclose certain art; 2) Inventor’s purported misrepresentations in the patent application regarding prior production and commercial sales of the claimed invention. The district court denied plaintiff’s inequitable conduct claim. The court held that the plaintiffs contention that the inventors acted with the specific intent to deceive was not the single most reasonable inference able to be drawn from the evidence. 32

Caron v. Lifestyle Crafts, LLC. 2013 WL 791287 (D. Arizona, March 4, 2013) Plaintiff's claim against the defendant for infringement of US Patent 7, 469, 634 was dismissed because plaintiff had committed inequitable conduct during prosecution. In particular, the district court found that: 1. Plaintiffs had misrepresented Michael Dywan’s status as a joint inventor to the PTO; 2. Plaintiffs submitted to the PTO declarations without disclosing three of the declarants had financial relationships with the plaintiff and misled the PTO regarding the qualifications of two other declarants; and 3. Plaintiff misrepresented his knowledge of chemical etching and misrepresented his knowledge of the teachings of an earlier patent. The court found this case was exceptional and awarded attorneys’ fees. “But for Plaintiffs’ inequitable conduct before the PTO and filing of this lawsuit, Lifestyle Crafts would not have incurred defense fees. Thus, the Court finds an award of attorney fees under § 285 is necessary to prevent a gross injustice and is justified. ” (A determination of inequitable conduct justifies the court finding a case exceptional for awarding attorney’s fees. ) 33

Protective Industries, Inc. v. Ratermann Mfg. , Inc. 2013 WL 393466 (M. D. Tenn. Jan. 31, 2013) Plaintiff sued defendant for infringement of US patent 7, 681, 587 for a protective sleeve for a gas cylinder. Defendant counter-claimed that the patent was unenforceable for inequitable conduct. Defendant argued that the plaintiff had: (1) submitted a “misleading and materially incomplete English language abstract” of French patent 2 878 678, and (2) failed to submit a WIPO Written Opinion in a related international application. The district court granted plaintiff’s motion for summary judgment on inequitable conduct. Plaintiff’s expert Stephan Kunin testified that plaintiff did not need to provide more than an English-language abstract and did not need to provide the WIPO written opinion. Defendants did not produce any evidence which supports a finding of either materiality or intent as to failure to provide the Written Opinion or French patent application. Therefore, defendant had not established inequitable conduct. 34

Micron Technology, Inc. v. Rambus Inc. 2013 WL 227630 (D. Del. January 2, 2013) Micron sought declaratory judgment of patent unenforceability against Rambus for spoliation of evidence. Micron proved that the document destruction program undertaken by Rambus was executed selectively only for patent litigation purposes. “Rambus’ spoliation precluded Micron from possibly obtaining evidence of affirmative acts of egregious conduct, such as perjury, the manufacture of false arguments, or deliberate fraud during prosecution, Rambus has not satisfied its heavy burden of showing that its destruction of internal documents would not prejudice Micron’s defense of inequitable conduct. Again, the fact that no record was made of what documents were destroyed can be of no avail to Rambus, the bad faith actor. As a result, the court finds clear and convincing evidence that Rambus’ spoliation may have prejudiced Micron’s inequitable conduct claim. ” “Rambus’ spoliation was done in bad faith, that the spoliation prejudiced Micron, and that the appropriate sanction is to declare the patents-in-suit unenforceable against Micron. ” 35

Kim Laube & Co. v. Wahl Clipper Corp. LA CV 09 -00914 JAK (C. D. CA, July 18, 2013) Plaintiff Kim Laube & Co. sued defendant Wahl Clipper Corp. for infringement of US Patent No. 6, 473, 973 related to a disposable cutting head for a hair clippers. Defendant counter claimed that the ‘ 973 patent was unenforceable for inequitable conduct. At trial, the defendant produced evidence proving that plaintiff was aware of certain prior art related to its own snap-on combs which plaintiff did not disclose to the USPTO during the course of the prosecution of the ‘ 973 patent. Further, defendant proved that the prior art not disclosed by the plaintiff was “but for” material because it showed the features claimed in the ‘ 973 patent. The district court held the ‘ 973 patent unenforceable. Not only was the withheld reference material but that Laube had deliberately withheld the reference, satisfying the specific deceptive intent requirement. (Finding of specific deceptive intent stemmed from Laube’s experience with patents coupled with his evasive testimony on why he did not cite the prior art. ) 36

Shukh v. Seagate Technology, LLC. 2013 WL 1197403 (D. Minnesota, March 25, 2013) Shukh, a former employee of Seagate brought suit against Seagate for correction of inventorship and fraud, alleging that Seagate had wrongfully omitted Shukh as a co-inventor. Seagate moved for summary judgment, contending that Shukh had failed to state a claim upon which he could seek relief. The court granted Seagate’s motion to dismiss. The court held that Shukh had no economic interest in the patents and would suffer no financial harm as a result of not being named a co-inventor. Further, Shukh failed to present evidence of reputational damage sufficient to raise a genuine issue of material fact with respect to his standing to pursue correction of inventorship claims for the disputed patents. With regard to the fraud claim, the court held that Shukh failed to show the necessary detrimental reliance because he offered no evidence that he changed his course of conduct or otherwise relied on the misrepresentations made by Seagate. (Correction of inventorship in an application is permitted by amendment under 35 U. S. C. 116, which is implemented by 37 C. F. R. § 1. 48. ) 37

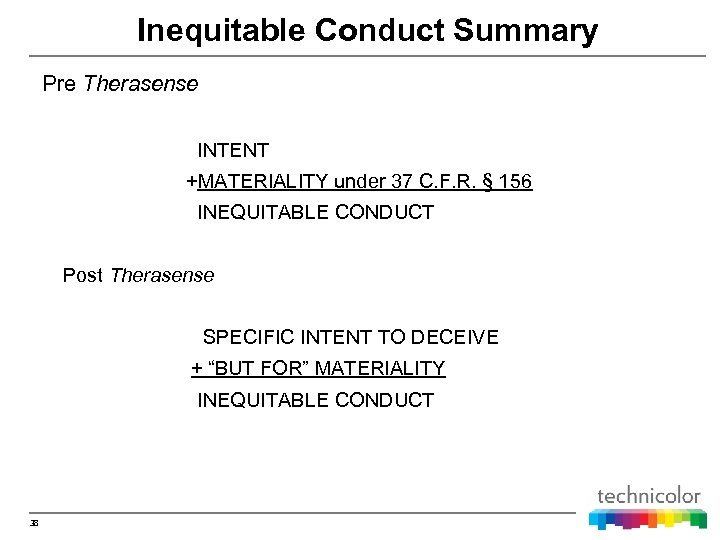

Inequitable Conduct Summary Pre Therasense INTENT +MATERIALITY under 37 C. F. R. § 156 INEQUITABLE CONDUCT Post Therasense SPECIFIC INTENT TO DECEIVE + “BUT FOR” MATERIALITY INEQUITABLE CONDUCT 38

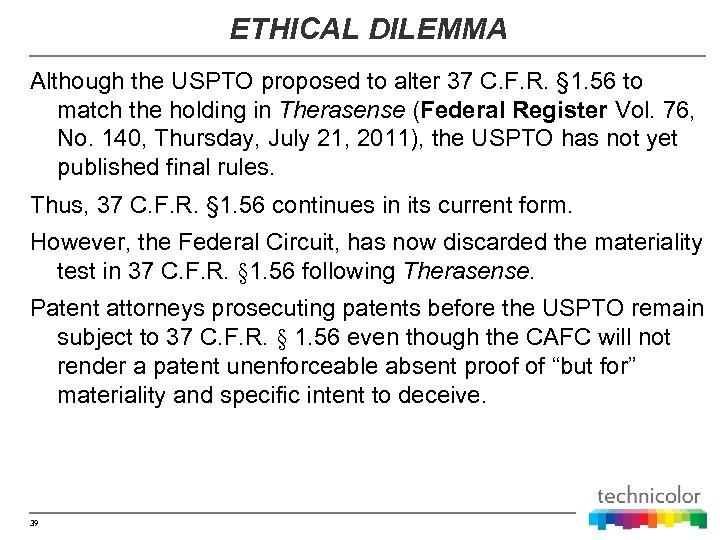

ETHICAL DILEMMA Although the USPTO proposed to alter 37 C. F. R. § 1. 56 to match the holding in Therasense (Federal Register Vol. 76, No. 140, Thursday, July 21, 2011), the USPTO has not yet published final rules. Thus, 37 C. F. R. § 1. 56 continues in its current form. However, the Federal Circuit, has now discarded the materiality test in 37 C. F. R. § 1. 56 following Therasense. Patent attorneys prosecuting patents before the USPTO remain subject to 37 C. F. R. § 1. 56 even though the CAFC will not render a patent unenforceable absent proof of “but for” materiality and specific intent to deceive. 39

Attorney-Client Privilege / Opinion of Counsel § In re Echostar Communications, 448 F. 3 d 1294, 78 U. S. P. Q. 1676 (Fed. Cir. 2006) § By relying on in-house counsel for its opinion, defendant waived its attorney-client privilege on the same subject matter from outside counsel. § When a party relies upon advice of counsel, it waives its right to all communications between client and attorney including documentary communications. § Work product waiver extends to the infringer’s state of mind, but work product not communicated is not discoverable. 40

Attorney-Client Privilege / Opinion of Counsel (continued) In Re Seagate Technology, LLC. 497 F. 3 d 1360, 83 U. S. P. Q. 2 d 1865 (Fed. Cir. 2007) As a general proposition, the assertion of the advice of counsel defense and the disclosure of opinion(s) of counsel does not waive the attorney-client privilege for communications with trial counsel. Absent exceptional circumstances, the waiver does not extend to trial counsel’s work product. 41

Attorney-Client Privilege Split of opinion on whether attorney-client privilege extends to patent agents. Attorney Client-Privilege extends to disclosures directed to a corporate law department seeking legal review. In re Spaulding Sports Worldwide, Inc. 203 F. 3 d 800 (Fed. Cir. , 2000) 42

Ethical Dilemma 35 U. S. C. § 112 (a) The specification shall contain a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains, or with which it is most nearly connected, to make and use the same, and shall set forth the best mode contemplated by the inventor or joint inventor of carrying out the invention. 35 U. S. C. § 282(b)(3) Invalidity of the patent or any claim in suit for failure to comply with— (A) any requirement of section 112, except that the failure to disclose the best mode shall not be a basis on which any claim of a patent may be canceled or held invalid or otherwise unenforceable. (See http: //www. patentlyo. com/hricik/2012/07/the-best-moderequirement-and-the-conflict-of-interest-it-creates. html) 43

The “America Invents Act” § 298. Advice of counsel The failure of an infringer to obtain the advice of counsel with respect to any allegedly infringed patent, or the failure of the infringer to present such advice to the court or jury, may not be used to prove that the accused infringer willfully infringed the patent or that the infringer intended to induce infringement of the patent. (codifies Knorr-Bremse Systeme Fuer Nutzfahrzeuge v. Dana Corporation et al. 383 F. 3 d 1337 (Fed. Cir. 2004) (en banc)) 44

The “America Invents Act” § 257 - Supplemental examinations (c) (1) IN GENERAL. —A patent shall not be held unenforceable on the basis of conduct relating to information that had not been considered, was inadequately considered, or was incorrect in a prior examination of the patent if the information was considered, reconsidered, or corrected during a supplemental examination of the patent. The making of a request under subsection (a), or the absence thereof, shall not be relevant to enforceability of the patent under section 282. . 45

The “America Invents Act” (continued) § 257 - Supplemental examinations (e) Fraud- If the Director becomes aware, during the course of a supplemental examination or reexamination proceeding ordered under this section, that a material fraud on the Office may have been committed in connection with the patent that is the subject of the supplemental examination, then in addition to any other actions the Director is authorized to take, including the cancellation of any claims found to be invalid under section 307 as a result of a reexamination ordered under this section, the Director shall also refer the matter to the Attorney General for such further action as the Attorney General may deem appropriate. Any such referral shall be treated as confidential, shall not be included in the file of the patent, and shall not be disclosed to the public unless the United States charges a person with a criminal offense in connection with such referral. 46

Ethical Dilemma Can a patent practitioner who prosecuted the patent ethically represent the patentee in a supplemental proceedings under 35 U. S. C. § 257 ? Probably not 47

New USPTO MODEL RULES § 11. 201 Advisor. In representing a client, a practitioner shall exercise independent professional judgment and render candid advice. In rendering advice, a practitioner may refer not only to law but to other considerations such as moral, economic, social and political factors that may be relevant to the client’s situation. § 11. 307 Practitioner as witness. (a) A practitioner shall not act as advocate at a proceeding before a tribunal in which the practitioner is likely to be a necessary witness unless: (1) The testimony relates to an uncontested issue; (2) The testimony relates to the nature and value of legal services rendered in the case; or (3) Disqualification of the practitioner would work substantial hardship on the client. (b) A practitioner may act as advocate in a proceeding before a tribunal in which another practitioner in the practitioner’s firm is likely to be called as a witness unless precluded from doing so by §§ 11. 107 or 11. 109. 48

c6a59ca8eb0c4b0530546c11fd52786a.ppt