c94925e8fc399787a69ce62c35dc9963.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 37

Environment and Development Master’s Programme Ton Dietz Febr 23 2009 Geographical Diversity and “Competing Landscapes”

John Cole • Geography of the World’s Major Regions (1996): • Friendly environments - tropical: humid and dry forests/woodlands - subtropical and temperate rainforests evergreen sclerophyllous temperate broadleaf forests temperate needle leaf forests tropical grasslands savannas temperate grasslands

Cole’s Harshlands • • Mountain systems Warm deserts Cold-winter deserts Tundra communities and icecaps

Embedding • People’s livelihoods and people’s lives are embedded in space; each person needs direct livelihood space, often in different places, and each person needs indirect livelihood space (which has a ‘footprint’ elsewhere).

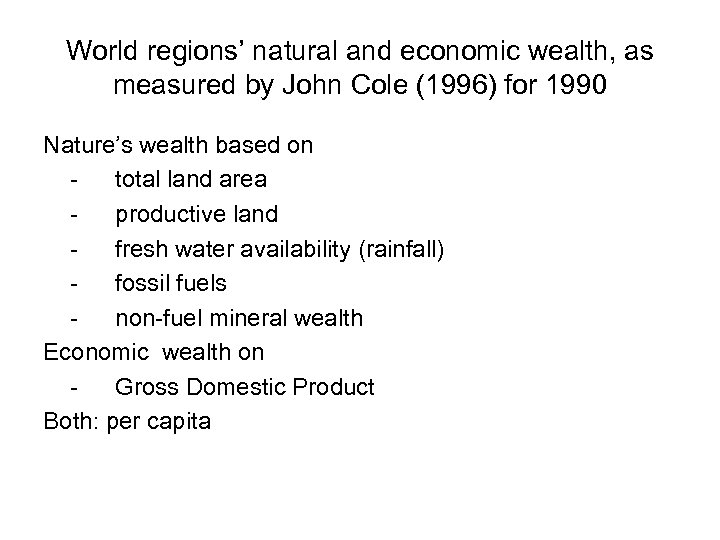

World regions’ natural and economic wealth, as measured by John Cole (1996) for 1990 Nature’s wealth based on total land area productive land fresh water availability (rainfall) fossil fuels non-fuel mineral wealth Economic wealth on Gross Domestic Product Both: per capita

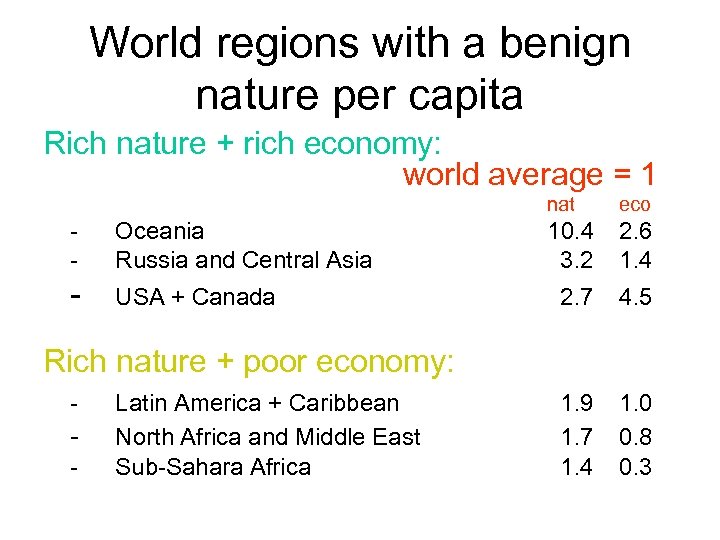

World regions with a benign nature per capita Rich nature + rich economy: world average = 1 nat - Oceania Russia and Central Asia - USA + Canada eco 10. 4 3. 2 2. 6 1. 4 2. 7 4. 5 1. 9 1. 7 1. 4 1. 0 0. 8 0. 3 Rich nature + poor economy: - - Latin America + Caribbean North Africa and Middle East Sub-Sahara Africa

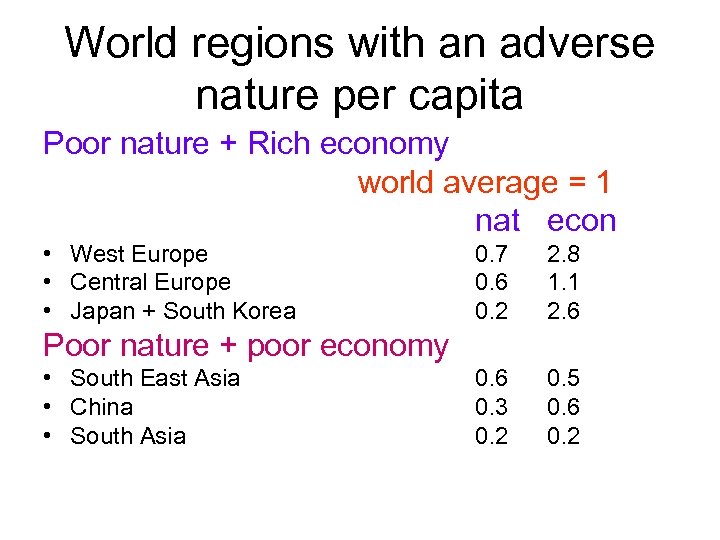

World regions with an adverse nature per capita Poor nature + Rich economy world average = 1 nat econ • West Europe • Central Europe • Japan + South Korea 0. 7 0. 6 0. 2 2. 8 1. 1 2. 6 0. 3 0. 2 0. 5 0. 6 0. 2 Poor nature + poor economy • South East Asia • China • South Asia

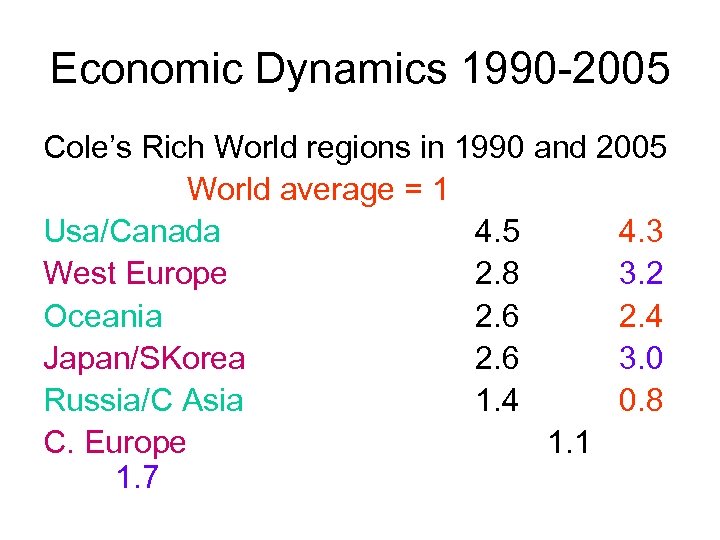

Economic Dynamics 1990 -2005 Cole’s Rich World regions in 1990 and 2005 World average = 1 Usa/Canada 4. 5 4. 3 West Europe 2. 8 3. 2 Oceania 2. 6 2. 4 Japan/SKorea 2. 6 3. 0 Russia/C Asia 1. 4 0. 8 C. Europe 1. 1 1. 7

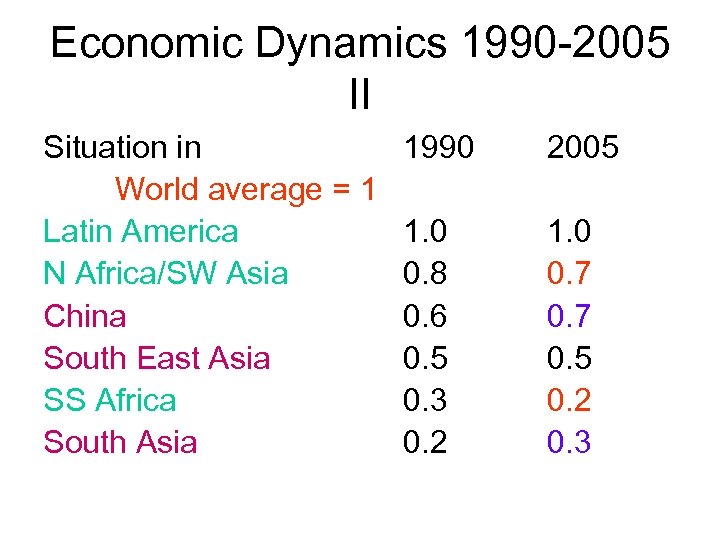

Economic Dynamics 1990 -2005 II Situation in World average = 1 Latin America N Africa/SW Asia China South East Asia SS Africa South Asia 1990 2005 1. 0 0. 8 0. 6 0. 5 0. 3 0. 2 1. 0 0. 7 0. 5 0. 2 0. 3

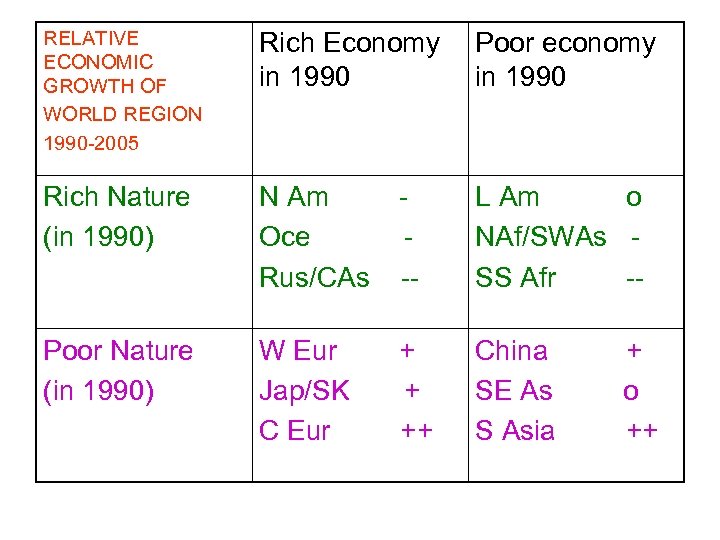

RELATIVE ECONOMIC GROWTH OF WORLD REGION 1990 -2005 Rich Economy in 1990 Poor economy in 1990 Rich Nature (in 1990) N Am Oce Rus/CAs -- L Am o NAf/SWAs SS Afr -- Poor Nature (in 1990) W Eur Jap/SK C Eur + + ++ China SE As S Asia + o ++

What does this suggest? During the last fifteen years the world economy was growing faster in world regions which are less endowed with natural resources per capita than in world regions which are better endowed by nature. Paul Collier: proves that regions with more natural resources have had a higher chance during the past few decades to be engaged in war and violence (often with bad effects for economic growth). Other way around: regions without many natural resources had to find peaceful ways to get access to those + had to become clever in using them effectively

But don’t become a-historical! This is true for the last fifty years! During the period 1870 -1945 world regions with a growing economy but not many own natural resources tried to get those by violent conquest (Britain and France first, Germany, Italy and Japan later). This proved to be disastrous, particularly for the newcomers. The world economy was then taken over by the powers which were well endowed with natural resources: USA and Russia Until that imploded (Russia 1990; USA 2008) And what is next? ? ?

Back to Cole: Productive potential for crops, livestock and forest products • Rainfall/area as a basis for calculation of sweet water availability (for agriculture, drinking water and other use) • Existing land use as a basis for quality assessment of land: – Crop land x 1 – Pasture land x 0. 1 – Forest land x 0. 2

However: • Land evaluation for productive use: – Also assessment of soil quality, including micro nutrients – Assessment of crop and seed quality in terms of (potential) productivity – Assessment of animal quality and management in terms of (potential) productivity – Assessment of water management: irrigation, water harvesting – Assessment of soil erosion and land degradation – The potential of fisheries and productive use of water bodies is missed

Land evaluation for agriculture • For a particular (type of) land surface: • Assessment of the percentage of the land that can be used (potentially) for crop cultivation, for pasture, and for productive forest use (including NTFP) • Assessment of the most likely/recommended use pattern (crops/livestock/forest product) and its productive capability • Assessment of the population supporting capacity

Example • One square kilometre in the tropical dryland zone with savannah vegetation = 100 hectare • 10% bare rock; 10% severely degraded; 10% used for habitat/infrastructure purposes • 70% can be used for productive purposes = 70 hectare • However: without external fertilisation it may need 2 years of rest for every 1 year of production (Fallow or Ruthenberg factor = 0. 33)

Suppose: • All 70 ha used for grain crop = sorghum, with one harvest per year, and R=0. 33 • Farmers on average produce 1000 kg per hectare of grains (stalks used for fertilisation) • This means: 0. 33 x 70 x 1000 kg = 23, 000 kg in a year • 1 kg = 3500 Cal of food value • = 80 million Cal • 1 human being needs 2260 Cal/day = 825, 000 Cal/year • This area may feed 100 people

However: • Strong fluctuations in rainfall and crop yields between years: in this area total crop failure once every ten years; bumper crops once every ten years: between 0 and 2000 kg/ha • Hence: this area can feed between 0 and 200 people in a year • And also: people need to cook the food: they need energy to do so: unused and fallow land may provide that (but you take it away from nature, and then nature needs longer fallow periods) • And ‘room for nature’? On the 25% ‘unused land’? On fallow land? In the rivers and water bodies?

How to deal with risks? • Save bumper harvest crop for lean years (storage!) • Spread drought and flood risk by micromanagement: high spots: flood avoidance + low spots/ ‘wetlands in drylands’: water harvesting • Spread drought risks by combining crops and varieties (sorghum-millet-maize; early maturing-late maturing, etc. )

How to improve? • Develop irrigation (canal/river; by gravity or pumps; groundwater; manual; animal or pumps): avoid droughts + add harvests – up to three in a year possible (Risk: siltation; aquifer depletion; breakdown of equipment; social conflicts about water and land rights) • Add manure/fertilisers or combine with crops which fix nitrogen, e. g. Pulses. Restricts fallow needs and improves harvest yields. (Risk: availability; price fluctuations; overfertilisation: pests; water pollution)

Suppose: • All 70 hectares used continuously and with irrigation, giving three sorghum harvests of 3, 000 kg/ha per year: • Potential production: • 70 x 1. 0 x 3000 = 630, 000 kg = 2. 268 million Cal. • If all would be used locally: 2750 people can be fed.

And what could you do more? • Change crop: to rice, with a maximum of three harvests of 10, 000 kg/ha • Develop the soil where it can’t be used: from 70 to 95% of the land. • So 12. 440 people can be fed locally • However: if these would all live there: they need habitat space. If they would live on the remaining 5 hectare they each have 4 square meter person. . • And they can no longer gather their firewood needs locally.

And what about the market? • Suppose rice is 2 x price of sorghum: if you sell all your rice and buy sorghum: you can feed twice the number of people. • You can select high-value crops, like tomatoes or cotton: depends on the net terms of trade how much you would gain. • Risks?

What if you would be a pastoralist in the same area? • Suppose you have cattle: this savannah dryland area on average has a feed carrying capacity of 100 cattle, and enough water sources for year-long watering and some salt(y grass). • How many people can be fed with 100 cattle? What do you need to know?

Cattle productivity • Milk, meat (and blood) (and non-food products) • Composition of the herd: old/young; female/male • Suppose: out of 100 there are 70 calves, 5 steers/bulls and 25 cows • Suppose: all 25 cows produce milk; for calves and for human consumption • For humans: suppose 3. 3 litres per day for 300 days/year = 1000 litres per cow/yr • Total production of milk: 25 x 1000 = 25, 000 litres • 1 liter of milk = 700 Cal • So: 25, 000 x 700 = 17. 5 million Cal • This can feed 21 people for a year if they would only drink milk

And what about the meat? • Suppose: cows and bulls are slaughtered when they are 15 years old and steers when they are on average 3 years old: • In a herd of 100 cattle with 30 adults and 70 calves (50% male of which 1/3 slaughtered each year when they become adults): – – – Two adults slaughtered each year Twelve steers slaughtered each year = 14 x 100 kg of meat = 14, 000 kg of meat 1 kg of meat = 2000 Cal So meat food value = 28 million Cal/year Potentially feeding 34 people, if they only eat meat

So: • Potential food value of cattle pastoralism in this area of 100 ha: • Milk: 21 people • Meat: 34 people • Together: 55 people per sq km. • But: major fluctuations from year to year: droughts>animal deaths and low milk gifts; animal diseases>animal deaths; abortions (cows without calves); wildlife threats>animal deaths; conflict threats>not all land available for grazing (‘no go areas’).

What can pastoralists do? • Risk management: spread animals over large area (Pokot: tilia); be mobile; have more types of animals (more and less drought and disease resistant); share indigenous insurance arrangements; avoid conflicts and no-go areas; improve veterinary care; improve availability of water and extra feed; change to zero grazing/stall feeding • Improvements: improve animals: more weight, more milk production; change composition of the herd/flock • Sell milk and meat and make use of ‘caloric terms of trade’ (often 10 x compared to grains) by eating grains instead of animal produce.

And besides ecology-dependent livelihoods? • Different possibilities to supplement (or replace) ecology-dependent livelihoods with local resources other than crops, livestock and forest products: – Mining – Tourism – Payment for nature’s services (CO 2 storage; water buffer function; biodiversity function – Secondary production based on local primary resources (industry, handicrafts)

Besides: Added incomes • External support from government and non -governmental agencies as wages/salaries; gifts/aid; insurance payments/pensions (partly depends on area’s ‘public appeal’) • External support from remittances (labour migration): translocal/transnational linkages

From nature as provider to nature as theatre • Competition between different resource uses: – Crops (for local and for extra-local use; local food security versus market-dependent food security) – Livestock (idem) – Energy (firewood, charcoal, other; idem) – Mining (idem) – Habitat (for locals; for visitors) – Nature (for tourists; for biodiversity conservation; for other natural and esthetic functions) = Competition between different stakeholders with different frames of access/use rights

Entitlements to resources • Ownership rights (private individual, private company, communal, state, ‘open’) • Use rights: exclusive, sharing, seasonal, often group specific (nationality, ethnic, gender, age) • Right of access/right of way (de jure/de facto; free or through payments, fees and fines) • Obligations of maintenance: institutions of sustainable use, e. g. Water points; irrigation canals; forest reserves) • Institutions of conflict mitigation and avoidance (local courts; legal pluralism; religious leaders; community leaders; external powers through district heads, police, military • Institutions of (economic) power brokerage and frames of acceptable (‘normalised’) behaviour to mediate between livelihood needs and spatial access. • With generally very unequal distribution of positions of power and impacts on wealth and livelihood space.

Zoning as spatial governance • Areas are divided in rights-zones, with different (legal) power-holders • Layered claims-arrangements: – – – Between individuals Between ‘households’ and ‘families Between ‘clans’ and ethnic groups Between villages and other meso-spatial units Between ‘nations’/ state territories Ever more supra-national; global claim-making agencies (private companies, NGOs, UN agencies, foreign military personnel)

For instance • Our 1 square kilometre area might have: – A nature reserve, partly forbidden for everyone and harsh rules (‘shoot on sight’), partly tolerated access for gathering – A tourist hotel in foreign hands – An unclear wasteland that local people avoid (‘bewitched’) – A forest reserve with partial access and seasonal restrictions (and fines by a local court) – Water bodies with rules of access and exclusion – Village lands, under elected village leadership – Mosque lands and sacred groves under local priests – State property (e. g. Government schools and a police post) – Individual crop fields, but with free access to some tree products during some months – Individual houses and gardens, some enclosed and guarded

Political ecology • This is the domain of political ecology or political environmental geography • Careful mapping of zones of entitlements • Connecting that with stakeholder analysis, and power positions • And with local-global connectivity analysis • And connecting ‘livelihoods’ with ‘space’ and ‘governance’ • And looking for dynamics: changes in stakeholder positions and hence in outcomes of ‘competing landscapes’: shifts in land use; shifts in zoning

But don’t forget culture • Discourses of ‘useful’ and ‘useless’ landscapes, of ‘beautiful’ and ‘ugly’ landscapes, of ‘acceptable’ and ‘disgraceful’ landscape behaviour are cultural constructs • These are created by often generation-old learning patterns, but also by manipulation and PR management. • And opinions about ‘nature’ (and nature conservation) have competing frames of reference: urban vs rural; rich vs poor; men vs women; local vs global; farmers vs pastoralists.

Batterbury? • Main argument? • Specifics about locality? • Same approach or different?

c94925e8fc399787a69ce62c35dc9963.ppt