f518643e1ca0e64b2a42b4d74ee8c499.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 115

Entrepreneurship and Household Behavior Erik Hurst University of Chicago Booth School of Business July 2013 Entrepreneurship Research Boot Camp

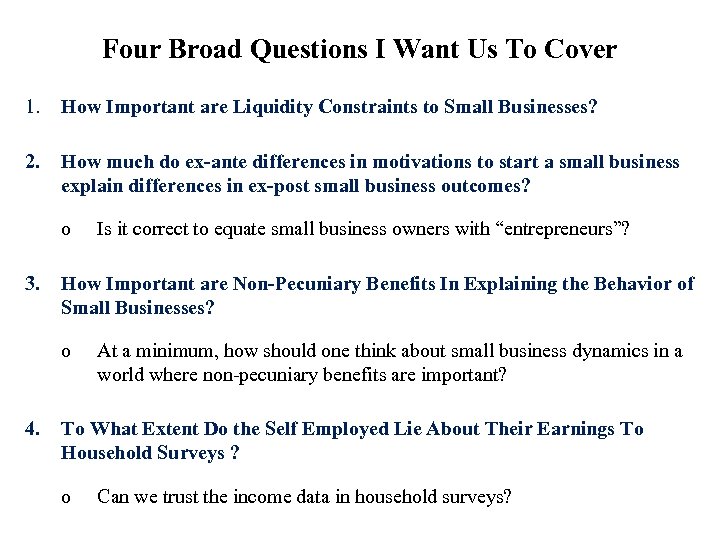

Four Broad Questions I Want Us To Cover 1. How Important are Liquidity Constraints to Small Businesses? 2. How much do ex-ante differences in motivations to start a small business explain differences in ex-post small business outcomes? o 3. How Important are Non-Pecuniary Benefits In Explaining the Behavior of Small Businesses? o 4. Is it correct to equate small business owners with “entrepreneurs”? At a minimum, how should one think about small business dynamics in a world where non-pecuniary benefits are important? To What Extent Do the Self Employed Lie About Their Earnings To Household Surveys ? o Can we trust the income data in household surveys?

Part 1: Liquidity Constraints and Small Business Formation (Some Theory)

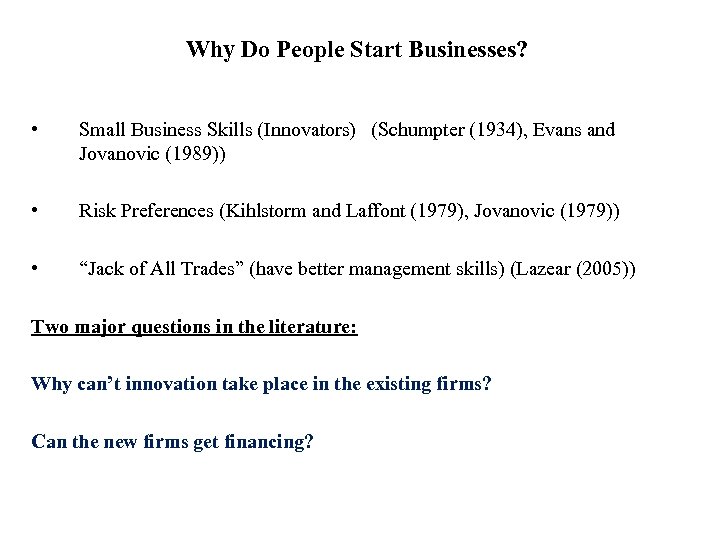

Why Do People Start Businesses? • Small Business Skills (Innovators) (Schumpter (1934), Evans and Jovanovic (1989)) • Risk Preferences (Kihlstorm and Laffont (1979), Jovanovic (1979)) • “Jack of All Trades” (have better management skills) (Lazear (2005)) Two major questions in the literature: Why can’t innovation take place in the existing firms? Can the new firms get financing?

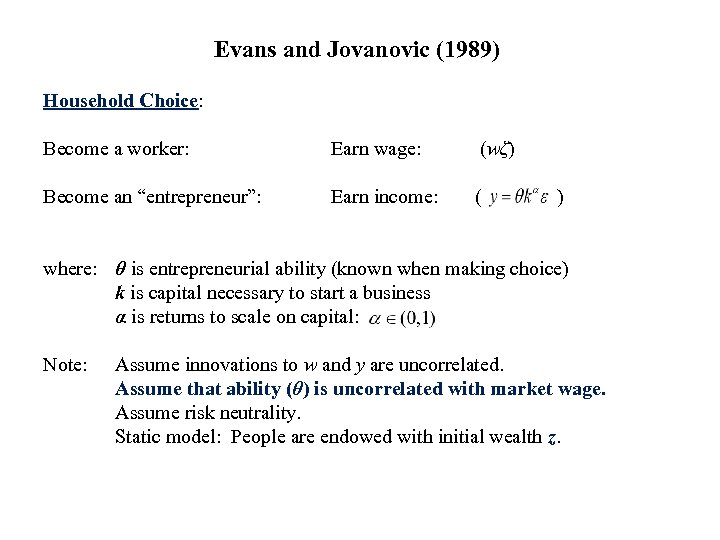

Evans and Jovanovic (1989) Household Choice: Become a worker: Earn wage: (wζ) Become an “entrepreneur”: Earn income: ( ) where: θ is entrepreneurial ability (known when making choice) k is capital necessary to start a business α is returns to scale on capital: Note: Assume innovations to w and y are uncorrelated. Assume that ability (θ) is uncorrelated with market wage. Assume risk neutrality. Static model: People are endowed with initial wealth z.

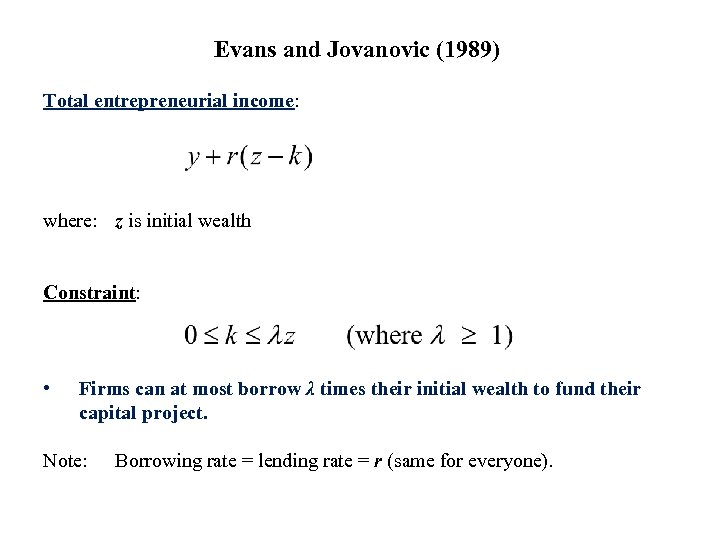

Evans and Jovanovic (1989) Total entrepreneurial income: where: z is initial wealth Constraint: • Firms can at most borrow λ times their initial wealth to fund their capital project. Note: Borrowing rate = lending rate = r (same for everyone).

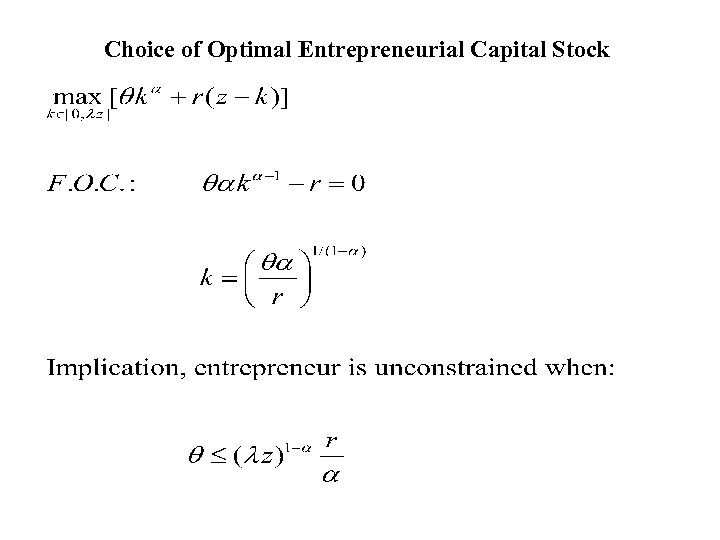

Choice of Optimal Entrepreneurial Capital Stock

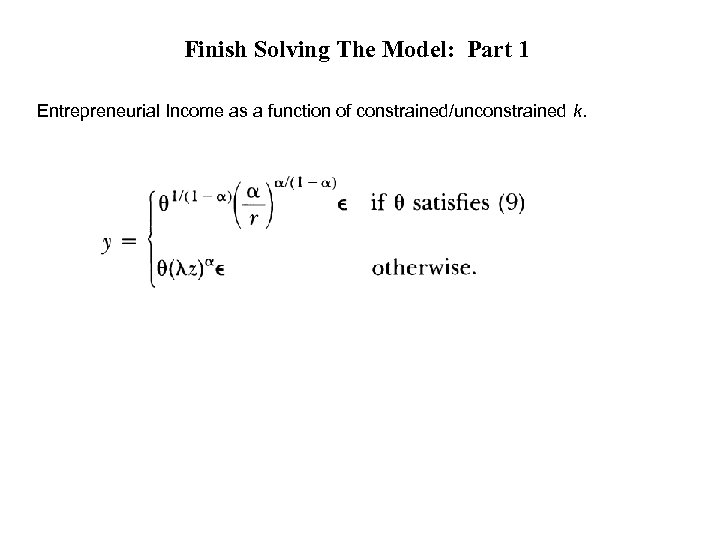

Finish Solving The Model: Part 1 Entrepreneurial Income as a function of constrained/unconstrained k.

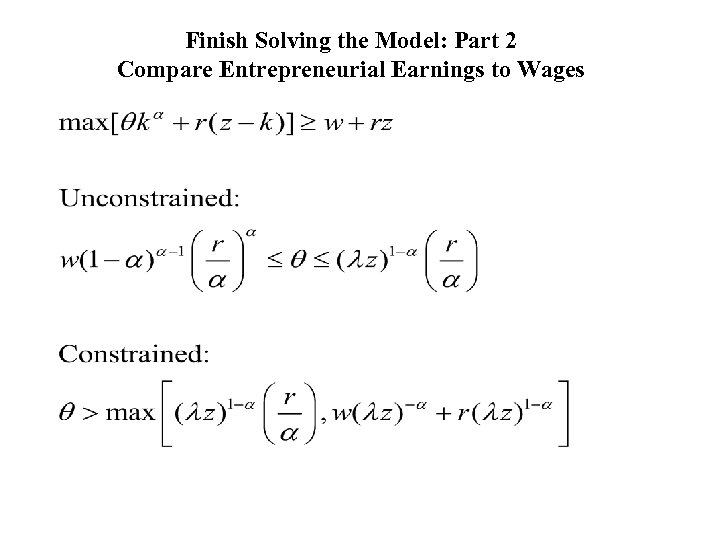

Finish Solving the Model: Part 2 Compare Entrepreneurial Earnings to Wages

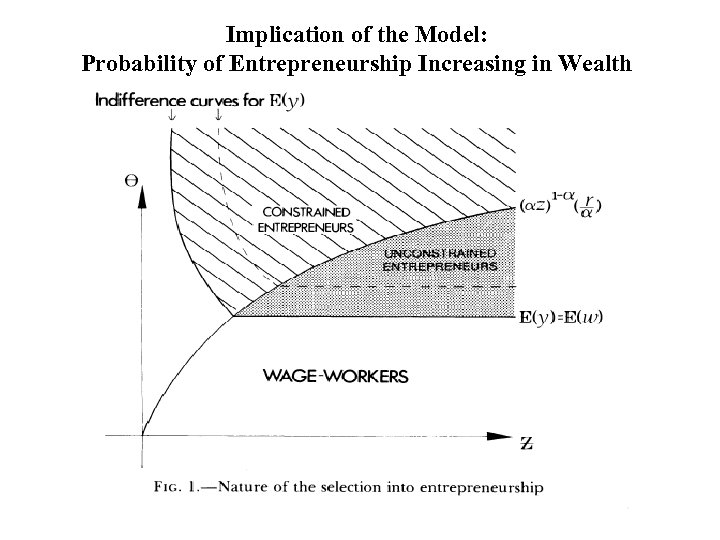

Implication of the Model: Probability of Entrepreneurship Increasing in Wealth

Evans and Jovanovic Conclusions • Richer households are less bound by liquidity constraints and as a result are more likely to enter entrepreneurship. • Should see a positive relationship between initial wealth and entry into small business ownership.

Part 2: Wealth, Tastes and Entrepreneurial Choice (Some More Theory)

In this paper, …. . • Formally show that the existence of non pecuniary benefits can: o Inform expectations about the relationship between initial household wealth and business entry decisions (in a world with no liquidity constraints). o Inform expectations about the distribution of firm size. o Inform expectations about the occupations/industries where one should see a high concentration of employment in small business firms. o Inform expectations about the level of non-pecuniary benefits of small business ownership and the level of aggregate labor productivity. o Inform expectations about the welfare and productivity costs of small business subsidies (including distributional implications).

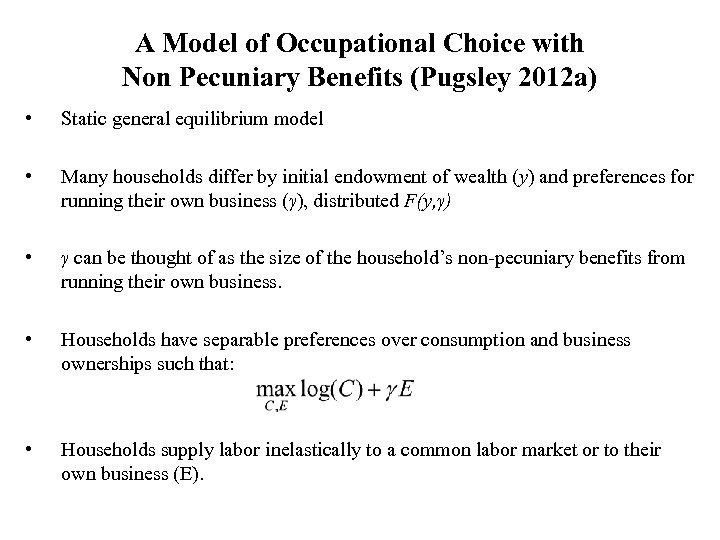

A Model of Occupational Choice with Non Pecuniary Benefits (Pugsley 2012 a) • Static general equilibrium model • Many households differ by initial endowment of wealth (y) and preferences for running their own business (γ), distributed F(y, γ) • γ can be thought of as the size of the household’s non-pecuniary benefits from running their own business. • Households have separable preferences over consumption and business ownerships such that: • Households supply labor inelastically to a common labor market or to their own business (E).

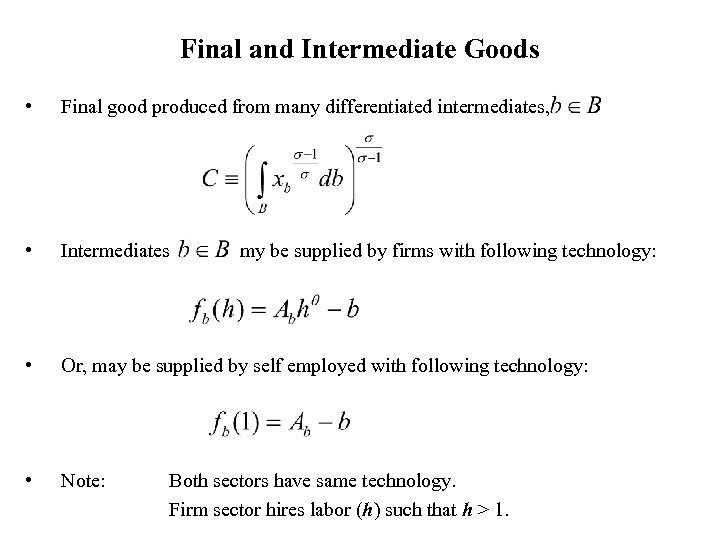

Final and Intermediate Goods • Final good produced from many differentiated intermediates, • Intermediates my be supplied by firms with following technology: • Or, may be supplied by self employed with following technology: • Note: Both sectors have same technology. Firm sector hires labor (h) such that h > 1.

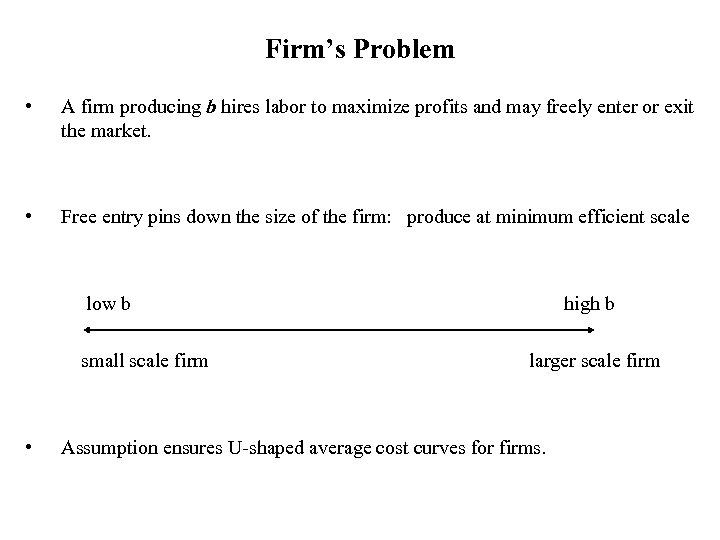

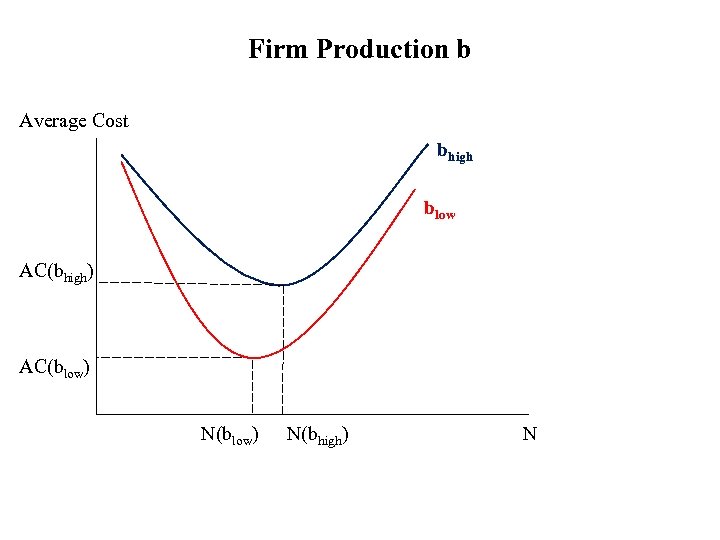

Firm’s Problem • A firm producing b hires labor to maximize profits and may freely enter or exit the market. • Free entry pins down the size of the firm: produce at minimum efficient scale low b high b small scale firm larger scale firm • Assumption ensures U-shaped average cost curves for firms.

Firm Production b Average Cost bhigh blow AC(bhigh) AC(blow) N(blow) N(bhigh) N

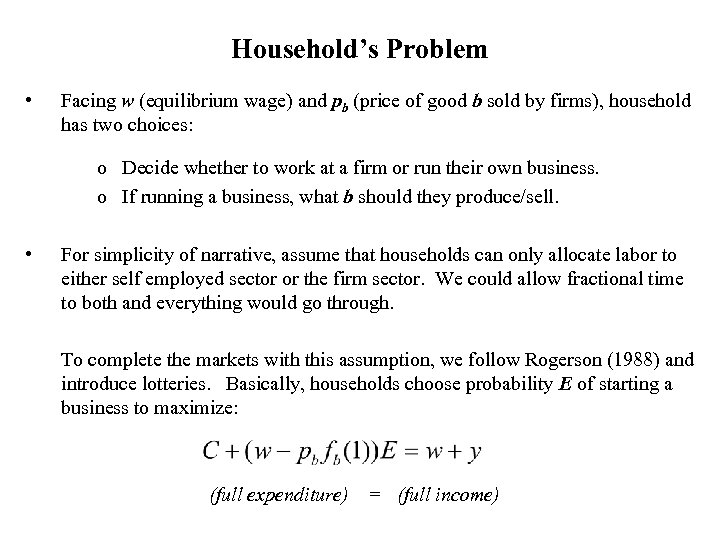

Household’s Problem • Facing w (equilibrium wage) and pb (price of good b sold by firms), household has two choices: o Decide whether to work at a firm or run their own business. o If running a business, what b should they produce/sell. • For simplicity of narrative, assume that households can only allocate labor to either self employed sector or the firm sector. We could allow fractional time to both and everything would go through. To complete the markets with this assumption, we follow Rogerson (1988) and introduce lotteries. Basically, households choose probability E of starting a business to maximize: (full expenditure) = (full income)

Some Comments 1. Non Pecuniary Benefits o o To highlight the mechanism, focus on an extreme notion of small (being self employed with no employees). o Could easily extend this to make the non pecuniary benefits diminish with firm size that one owns. o 2. Benefits come from being in a small firm (not running a firm). Could easily extend this to make non pecuniary benefits for being a worker in a firm diminish with the size of the firm. Heterogeneity in ability o To highlight mechanism, shut down any heterogeneity in ability (both in self employed and firm sector).

Model Trade-Off Benefits of small business ownership o Get utility of running a small business Costs of small business ownership o o o Forgo benefits of agglomeration Implies lower wages associated with production The lower wages reduce utility more for individuals with low wealth.

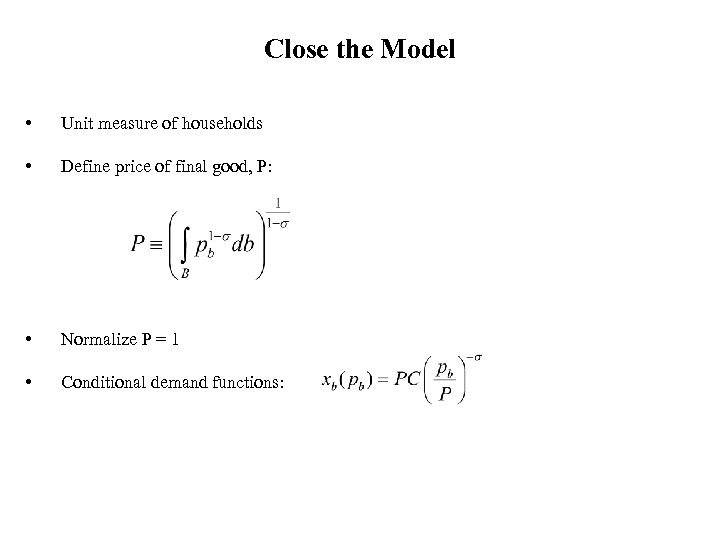

Close the Model • Unit measure of households • Define price of final good, P: • Normalize P = 1 • Conditional demand functions:

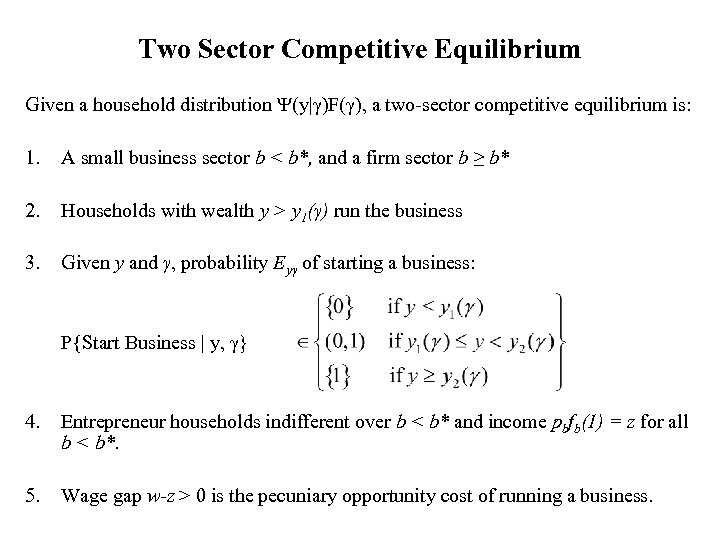

Two Sector Competitive Equilibrium Given a household distribution Ψ(y|γ)F(γ), a two-sector competitive equilibrium is: 1. A small business sector b < b*, and a firm sector b ≥ b* 2. Households with wealth y > y 1(γ) run the business 3. Given y and γ, probability Eyγ of starting a business: P{Start Business | y, γ} 4. Entrepreneur households indifferent over b < b* and income pbfb(1) = z for all b < b*. 5. Wage gap w-z > 0 is the pecuniary opportunity cost of running a business.

Implication 1: Small Business Sector Concentrated in a Few Industries • Explore this implication later in the lecture. We will see that small business activity is concentrated in a few industries. • Those goods that are produced using a low returns to scale technology will be dominated by very small firms. • The more important are non pecuniary benefits in utility, the more industries dominated by small firms.

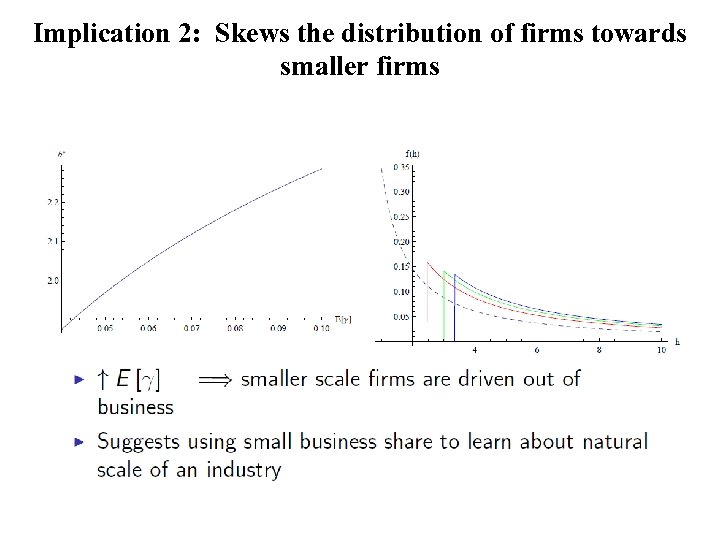

Implication 2: Skews the distribution of firms towards smaller firms

Implication 3: Wages and Firm Size Model predicts: Small business owners will earn less than wage workers, wage workers in the firm. Intuition: Some of the compensation will be taken in the nonpecuniary benefits. Importance: Discussed more in latter part of the lecture. Growing body of evidence suggesting that small business owners earn less than what they would have earned had they stayed as a worker!

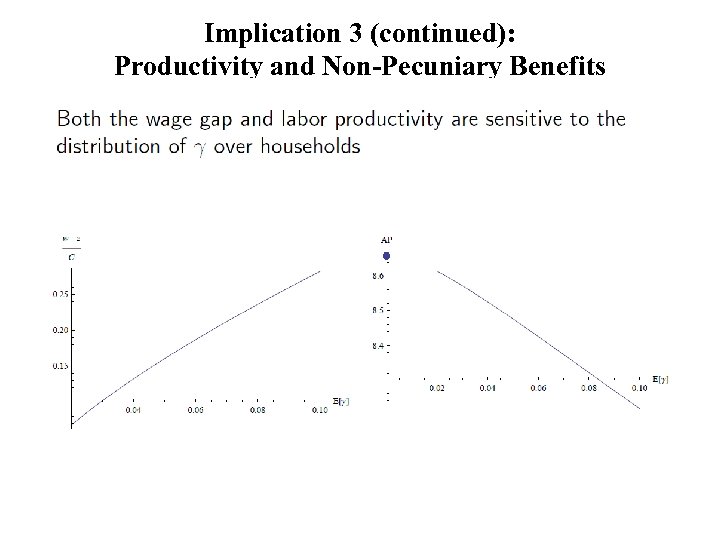

Implication 3 (continued): Productivity and Non-Pecuniary Benefits

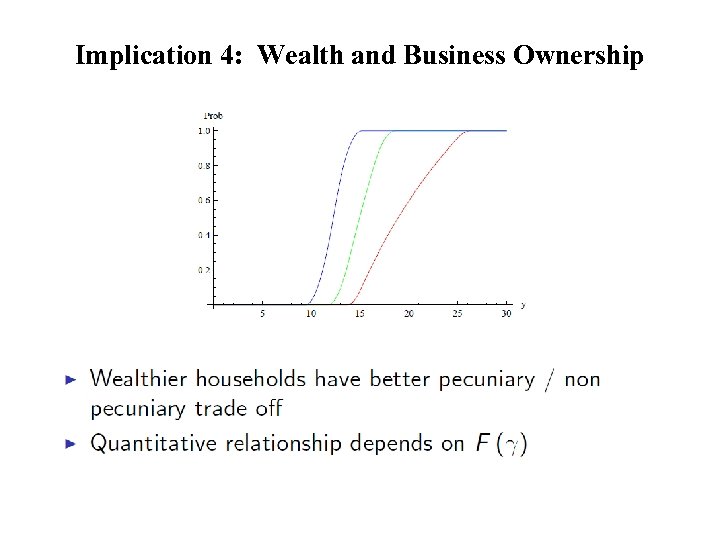

Implication 4: Wealth and Business Ownership

Implication 4: Wealth and Business Ownership Importance: o HUGE literature using the relationship between wealth and entry into business ownership as evidence of liquidity constraints. Cagetti and De. Nardi ; Buera ; Evans and Jovanovic ; Quadrini o The existence of non pecuniary benefits can undermine this type of empirical strategy to test for the importance of liquidity constraints as a deterrent to small business formation. o Can use additional moments from data (i. e. , wage gaps between wage and salary workers) to help tease out non-pecuniary benefits from liquidity constraints (Pugsley 2012 b)

One More Implication: A Policy Experiment • In order to assess the total and distribution impacts of small business subsidies, need to add a government sector to the model. • Suppose, governments provide subsidy s to small business “output”. • Fund the subsidy with lump sum taxes, T (to start). • Amend the budget constraint of households and add a balanced government budget constraint.

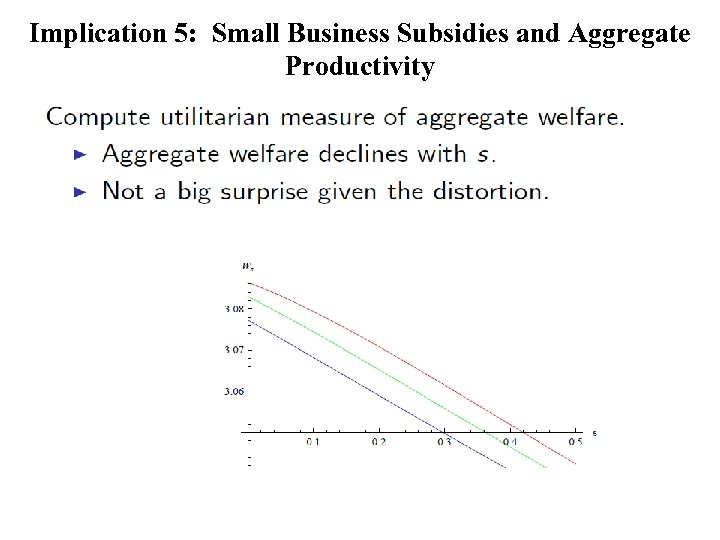

Implication 5: Small Business Subsidies and Aggregate Productivity

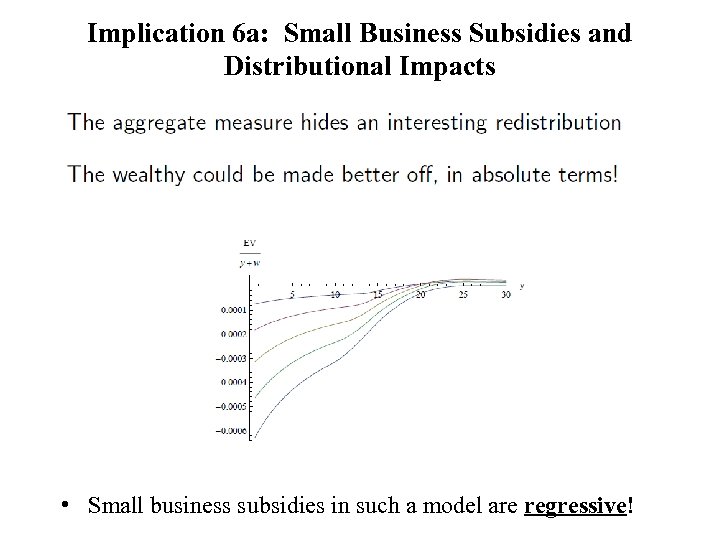

Implication 6 a: Small Business Subsidies and Distributional Impacts • Small business subsidies in such a model are regressive!

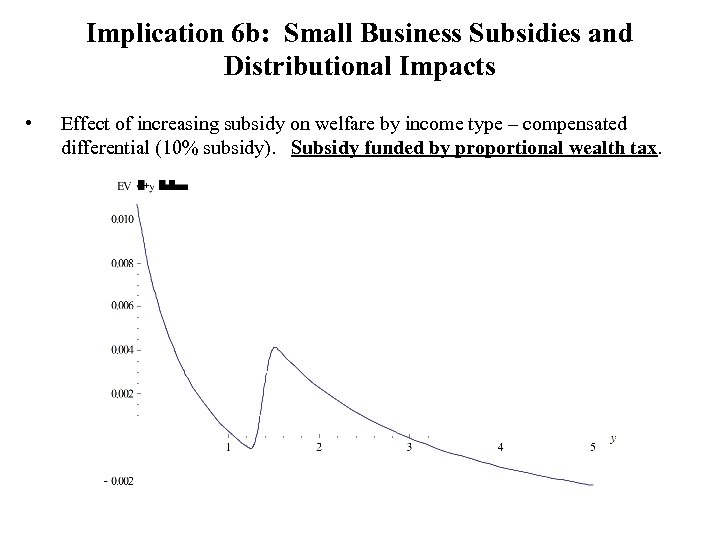

Implication 6 b: Small Business Subsidies and Distributional Impacts • Effect of increasing subsidy on welfare by income type – compensated differential (10% subsidy). Subsidy funded by proportional wealth tax.

Some Conclusions So Far • A positive relationship between business ownership and wealth could: o o be a symptom that liquidity constraints are binding be the result of the existence of non-pecuniary benefits in small business ownership. • Where is the literature with respect to these questions? • Is there conclusive evidence that liquidity constraints are a binding deterrent to small business activity? • Is there conclusive evidence that non-pecuniary benefits are an important part of small business start up motivations? • We will turn to these questions now…. .

Part 3: “Testing” for the Importance of Liquidity Constraints

Old School Tests of Liquidity Constraints for Entrepreneurs Basically, the majority of empirical papers regress business ownership (the propensity to become a business owner, the propensity to survive as a business owner) on household wealth. Prob (Start Business (t, t+1)) = α 0 + α 1 ln(Wealth(t)) + γ X + ε Early research concluded that if wealth is significant in predicting business entry, liquidity constraints are binding. (i. e. , α 1 > 0) Approach taken: Evans and Jovanovic (1989, JPE) Evans and Leighton (1989, AER) Fairlie (1999, Journal of Labor Economics) Quadrini (1999, Review of Income and Wealth)

Limitations of “Old School” Approach • The level of wealth is an endogenous variable. Are the factors that cause wealth accumulation orthogonal to entrepreneurial entry? o High ability earn more (accumulate more for retirement) and may be better at innovating. o Risk preferences can cause high wealth and taste for entrepreneurship o People planning for self employment accumulate assets for their retirement (do not have pensions). • Next Generation of Studies: o Try to find an “instrument” for changes in household wealth. • Note: These studies still do not attempt to distinguish between nonpecuniary benefits and liquidity constraints.

Next Generation: “Inheritances” as an Instrument • Instrument for wealth - look at liquidity windfalls which are uncorrelated with the decision to become an entrepreneur. o Many use inheritances as instrument. o Find inheritances are strongly correlated with entrepreneurial entry. o Receiving an inheritance in year t predicts entrepreneurial entry between t and t+k. • Holz-Eakin, Joulfaian, and Rosen (JPE, 1994) • Blanchflower and Oswald (1998, Journal of Labor Economics). 37

Up Though 2003: Conventional Wisdom • Liquidity constraints are an important deterrent to small business formation. • Liquidity constraints to small business formation is an important explanation of the dispersion in wealth (rich people keep accumulating wealth to relax their liquidity constraint for their small business). o Cagetti and De. Nardi (2006, JPE). • Welfare costs of liquidity constraints to entrepreneurship is large o Buera (2009, Annals of Finance) Note: Both papers use as the basis of their models, the relationship between wealth and starting a business using household micro data. 38

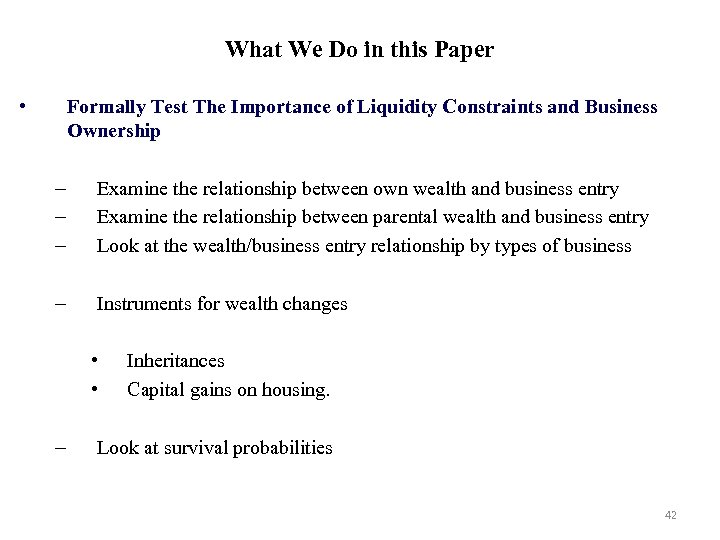

Hurst and Lusardi (2003) “Liquidity Constraints, Wealth, and Entrepreneurship” Goal of Paper o Are people interpreting the data correctly? o Do the relationships in the data point to evidence of liquidity constraints? Conclusion o The existence of binding liquidity constraints as a deterrent to small business activity is still very much an open question. o This research (and some other stuff I will show later) suggest that it will be hard to find evidence of binding liquidity constraints in household datasets. 39

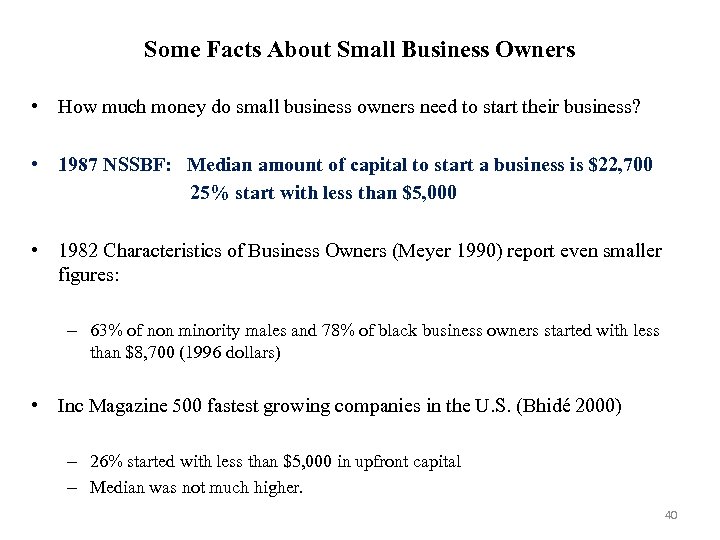

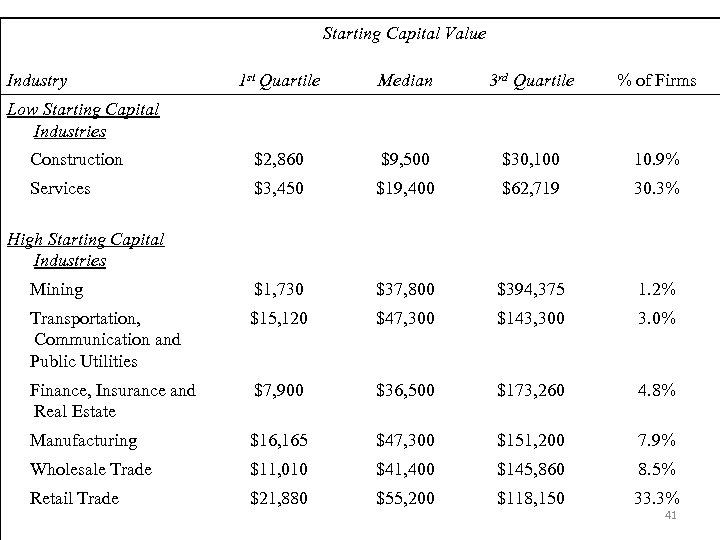

Some Facts About Small Business Owners • How much money do small business owners need to start their business? • 1987 NSSBF: Median amount of capital to start a business is $22, 700 25% start with less than $5, 000 • 1982 Characteristics of Business Owners (Meyer 1990) report even smaller figures: – 63% of non minority males and 78% of black business owners started with less than $8, 700 (1996 dollars) • Inc Magazine 500 fastest growing companies in the U. S. (Bhidé 2000) – 26% started with less than $5, 000 in upfront capital – Median was not much higher. 40

Starting Capital Value Industry 1 st Quartile Median 3 rd Quartile % of Firms Construction $2, 860 $9, 500 $30, 100 10. 9% Services $3, 450 $19, 400 $62, 719 30. 3% Mining $1, 730 $37, 800 $394, 375 1. 2% Transportation, Communication and Public Utilities $15, 120 $47, 300 $143, 300 3. 0% Finance, Insurance and Real Estate $7, 900 $36, 500 $173, 260 4. 8% Manufacturing $16, 165 $47, 300 $151, 200 7. 9% Wholesale Trade $11, 010 $41, 400 $145, 860 8. 5% Retail Trade $21, 880 $55, 200 $118, 150 33. 3% Low Starting Capital Industries High Starting Capital Industries 41

What We Do in this Paper • Formally Test The Importance of Liquidity Constraints and Business Ownership – – – Examine the relationship between own wealth and business entry Examine the relationship between parental wealth and business entry Look at the wealth/business entry relationship by types of business – Instruments for wealth changes • • – Inheritances Capital gains on housing. Look at survival probabilities 42

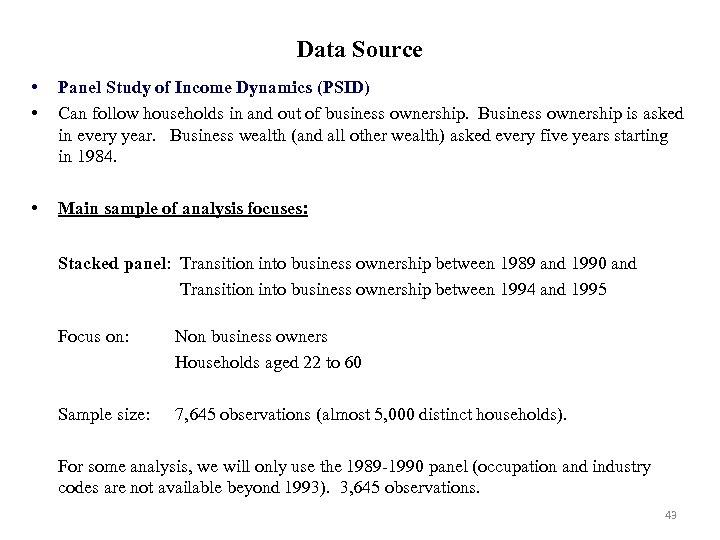

Data Source • • Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) Can follow households in and out of business ownership. Business ownership is asked in every year. Business wealth (and all other wealth) asked every five years starting in 1984. • Main sample of analysis focuses: Stacked panel: Transition into business ownership between 1989 and 1990 and Transition into business ownership between 1994 and 1995 Focus on: Non business owners Households aged 22 to 60 Sample size: 7, 645 observations (almost 5, 000 distinct households). For some analysis, we will only use the 1989 -1990 panel (occupation and industry codes are not available beyond 1993). 3, 645 observations. 43

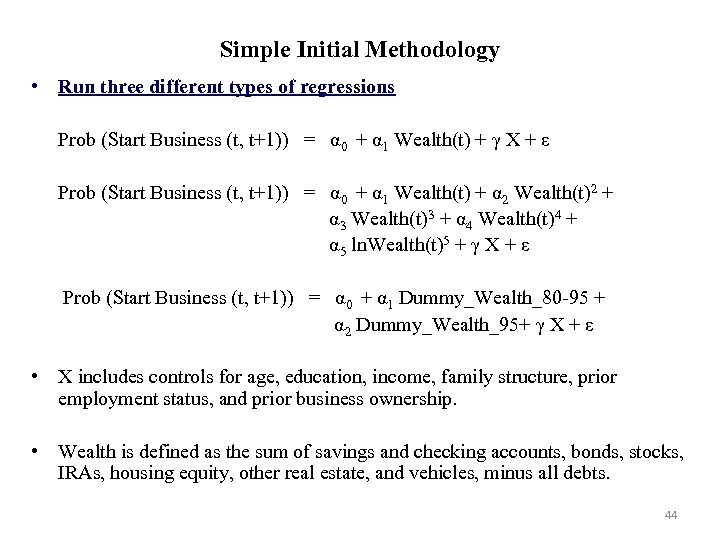

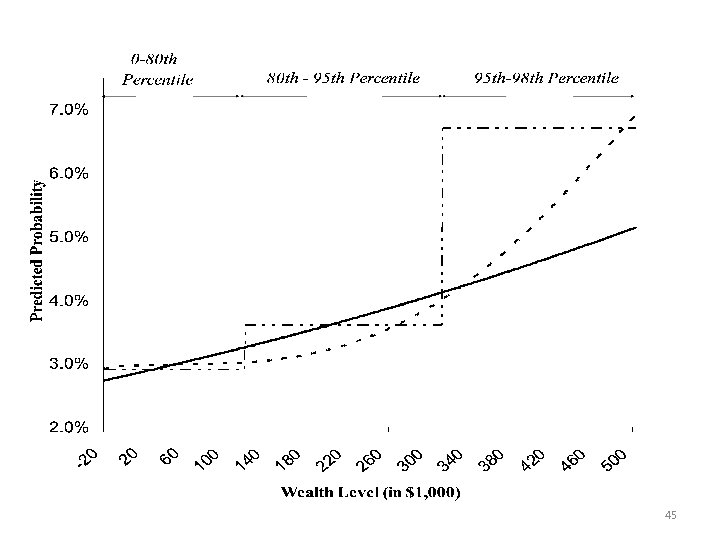

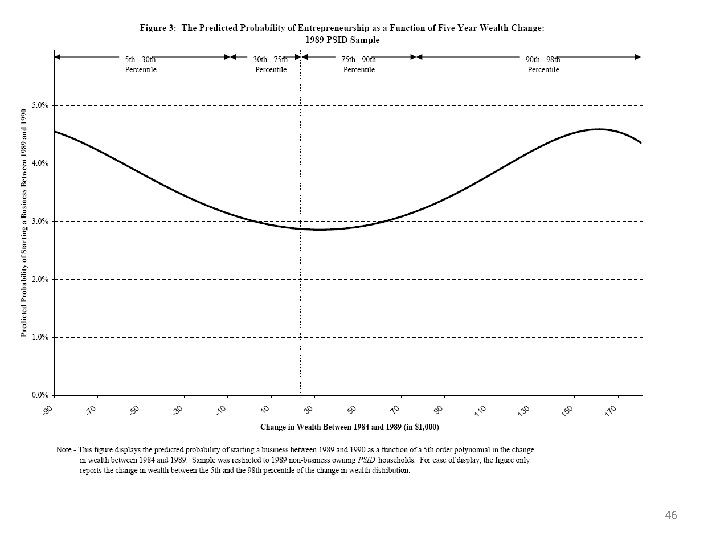

Simple Initial Methodology • Run three different types of regressions Prob (Start Business (t, t+1)) = α 0 + α 1 Wealth(t) + γ X + ε Prob (Start Business (t, t+1)) = α 0 + α 1 Wealth(t) + α 2 Wealth(t)2 + α 3 Wealth(t)3 + α 4 Wealth(t)4 + α 5 ln. Wealth(t)5 + γ X + ε Prob (Start Business (t, t+1)) = α 0 + α 1 Dummy_Wealth_80 -95 + α 2 Dummy_Wealth_95+ γ X + ε • X includes controls for age, education, income, family structure, prior employment status, and prior business ownership. • Wealth is defined as the sum of savings and checking accounts, bonds, stocks, IRAs, housing equity, other real estate, and vehicles, minus all debts. 44

45

46

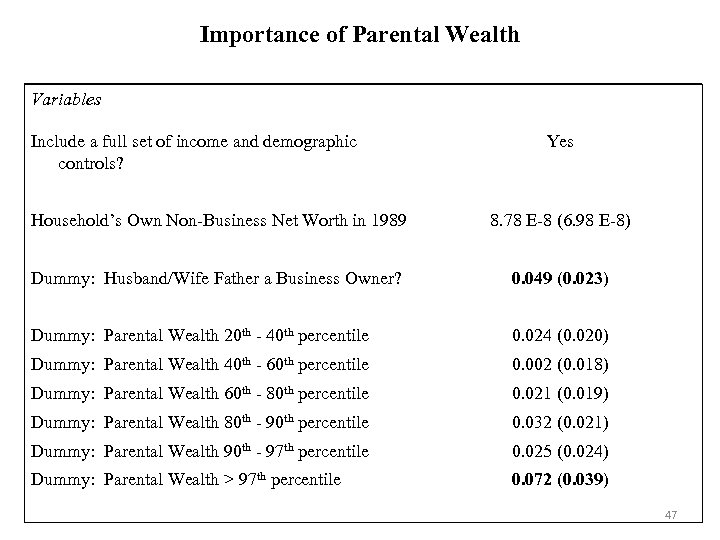

Importance of Parental Wealth Variables Include a full set of income and demographic controls? Yes Household’s Own Non-Business Net Worth in 1989 8. 78 E-8 (6. 98 E-8) Dummy: Husband/Wife Father a Business Owner? 0. 049 (0. 023) Dummy: Parental Wealth 20 th - 40 th percentile 0. 024 (0. 020) Dummy: Parental Wealth 40 th - 60 th percentile 0. 002 (0. 018) Dummy: Parental Wealth 60 th - 80 th percentile 0. 021 (0. 019) Dummy: Parental Wealth 80 th - 90 th percentile 0. 032 (0. 021) Dummy: Parental Wealth 90 th - 97 th percentile 0. 025 (0. 024) Dummy: Parental Wealth > 97 th percentile 0. 072 (0. 039) 47

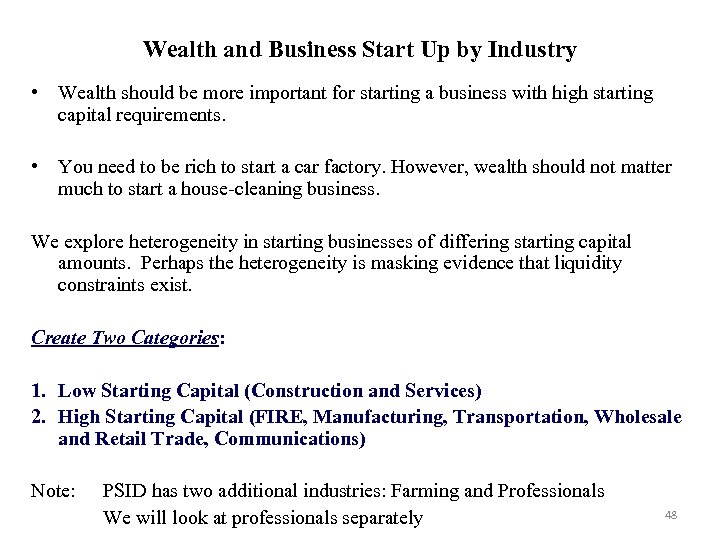

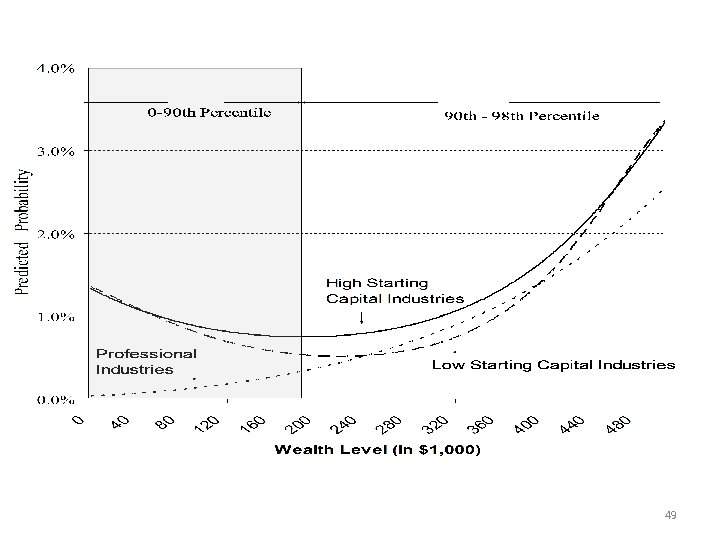

Wealth and Business Start Up by Industry • Wealth should be more important for starting a business with high starting capital requirements. • You need to be rich to start a car factory. However, wealth should not matter much to start a house-cleaning business. We explore heterogeneity in starting businesses of differing starting capital amounts. Perhaps the heterogeneity is masking evidence that liquidity constraints exist. Create Two Categories: 1. Low Starting Capital (Construction and Services) 2. High Starting Capital (FIRE, Manufacturing, Transportation, Wholesale and Retail Trade, Communications) Note: PSID has two additional industries: Farming and Professionals We will look at professionals separately 48

49

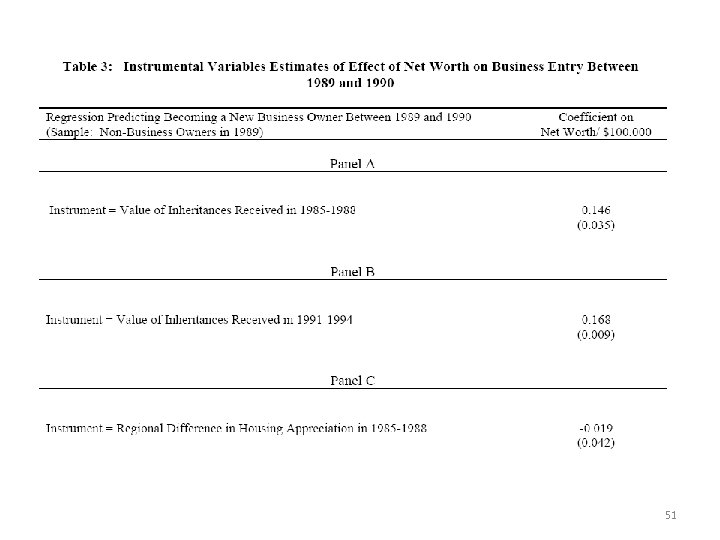

What about Inheritances as an Instrument? • Fact is replicated in our data set. Is the case closed? No…… Why? 1. Many business are transferred at the time of death (5% of NSSBF sample) 2. More importantly, inheritances are not randomly distributed in the population. Those who get inheritances are just different (on average) from those who do not. A counterfactual…… Test of the latter proposition Do future inheritances (received after the business is started) predict current business entry? 50

51

A New Instrument We use an alternative measure of liquidity: Regional variation in housing prices. Much evidence that households do borrow against home equity to sustain consumption or finance investment projects. – Brady, Canner and Maki (2000) – 20% of those who removed equity during the late 1990 s when refinancing used it to fund business investment. – Hurst and Stafford (2002) – find household who lost their jobs in the early 1990 s used home equity to prop up consumption. We predict that households who receive increases in home equity – all else equal – should have access to more liquidity. Are they more likely to start a business? We find NO effect of housing capital gains on business entry! 52

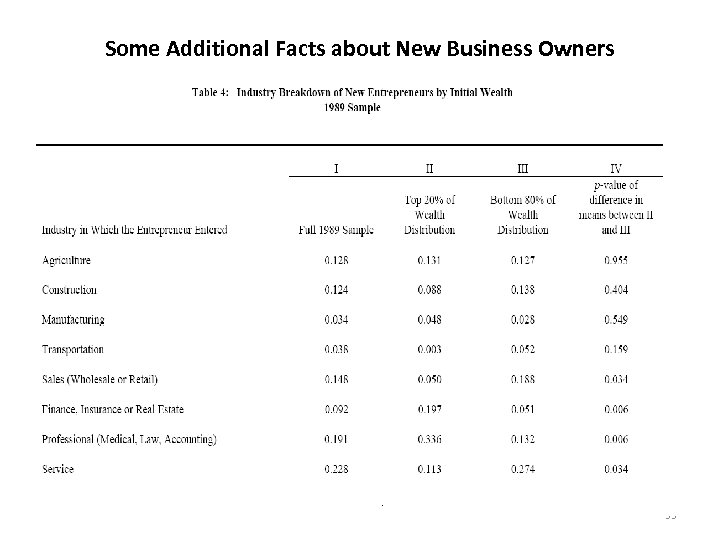

Some Additional Facts about New Business Owners 53

Some More Conclusions • Our findings do NOT promote cutting funding to the Small Business Administration (SBA). Part of the reason why liquidity constraints may not be binding is because of SBA policies. • Existing evidence on the existence of liquidity constraints for small businesses not very conclusive. The case for binding liquidity constraints deterring small business activity is still an open question! • Why is it the effect is so large for the really rich? Non-pecuniary benefits? Outstanding Questions: • Are the business owners in typical household or business survey important for economic growth? • Are there existing households who would start a profitable business if they had wealth that just are not showing up in the data? • What drives business ownership decisions for median household? 54

Part 4: A Detour: “What Do Small Businesses Do? ” (Erik Hurst and Ben Pugsley)

Some Background • There is a disconnect among researchers and policy makers between theoretical/conceptual models of “entrepreneurs” and the “universe of small business owners” on which we test theory/implement policy. o “Bill Gates” types (conjecture: they are rare) Match theoretical concept Innovate, efficiently share risk, has new idea/product, wants to grow, innovation has social spillovers, etc. o “Joe the Plumber” types (conjecture: they are not rare) My brother Does not want to grow, does not want to innovate, very content staying small, does not innovate ex-post, etc. .

Some Outstanding Questions • Question: What drives the decision to become a small business owner for the “Joe the Plumber” types? • Question: How do these other small businesses respond to the incentives we provide to stimulate entrepreneurial activity for the “Bill Gate” types? • Question: Do individuals really want to innovate and/grow when they start their business?

Data Sources To answer these questions, we are going to use a variety of data sources from: • Statistics of U. S. Businesses (SUSB) – maintained by Census using data from U. S. Business Register. o • Focuses on employer firms (excludes non-employers) National Survey of Small Business Finances o Focuses on firms with between 1 and 500 employees • Kauffman Firm Survey – Survey of new businesses; has panel dimension • Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics – Survey of new businesses; has panel dimension.

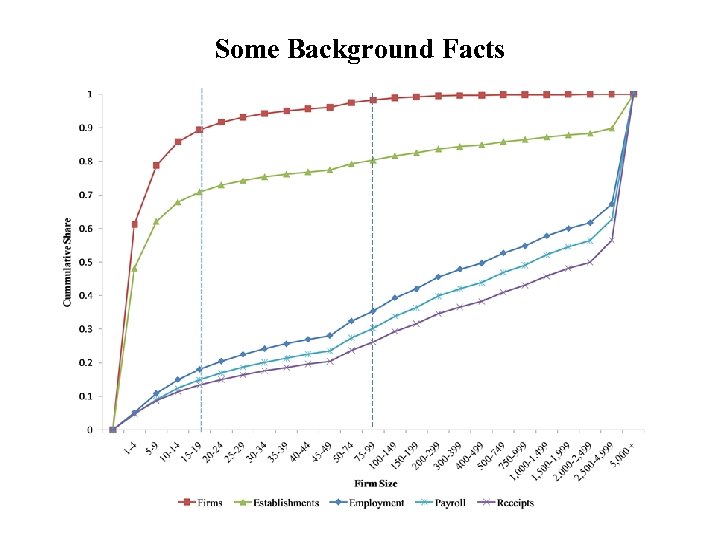

Some Background Facts • ~ 6 million employer firms in the U. S. in 2007 • Aside: • About 90% of employer firms have less than 20 employees. • About 20 percent of employment in is firms with less than 20 employees. ~ 22 million non-employers (which comprise about 4% of payrolls)

Some Background Facts

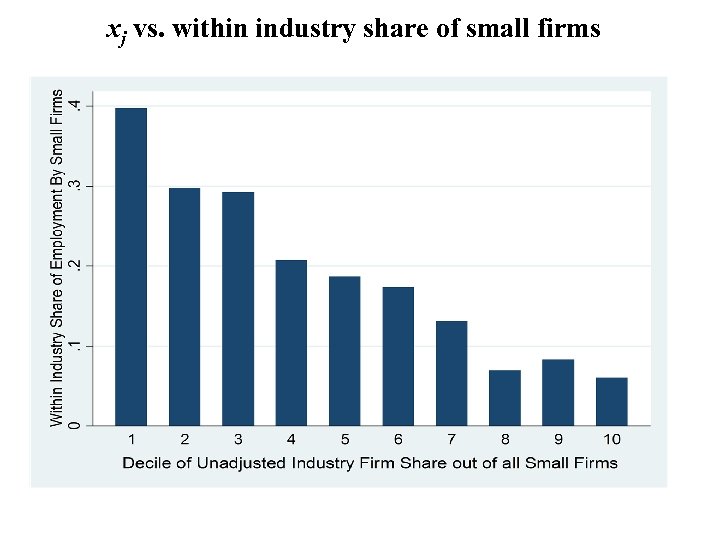

Who Are The Small Business Owners? • Define small business owners as those with less than 20 employees (or 100 employees). • Use data from the 2003 -2007 Statistics of U. S. Businesses (SUSB) – compiled by the U. S. Census. • Group all small businesses (across all industries) into 4 -digit NAICS industries (there about 300 4 -digit NAICS codes). • Define: • xj is share of small business in industry j out of all small businesses.

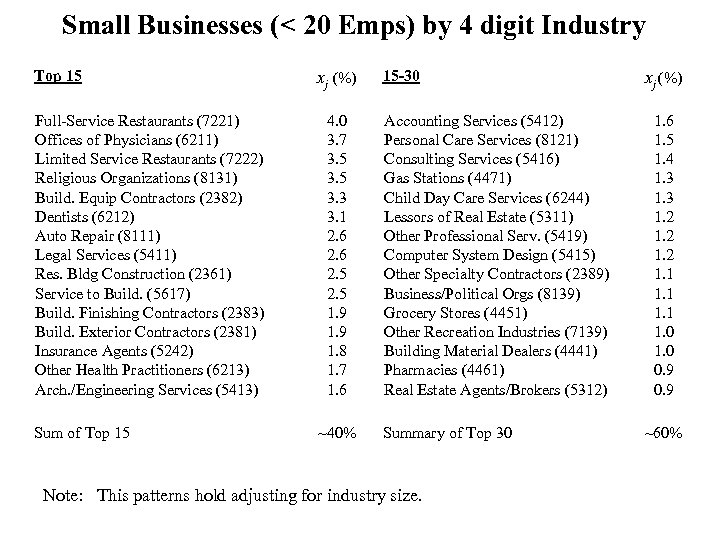

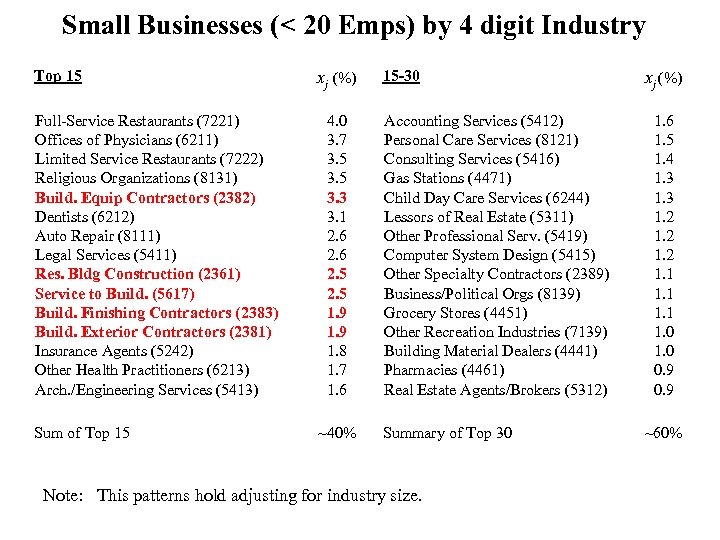

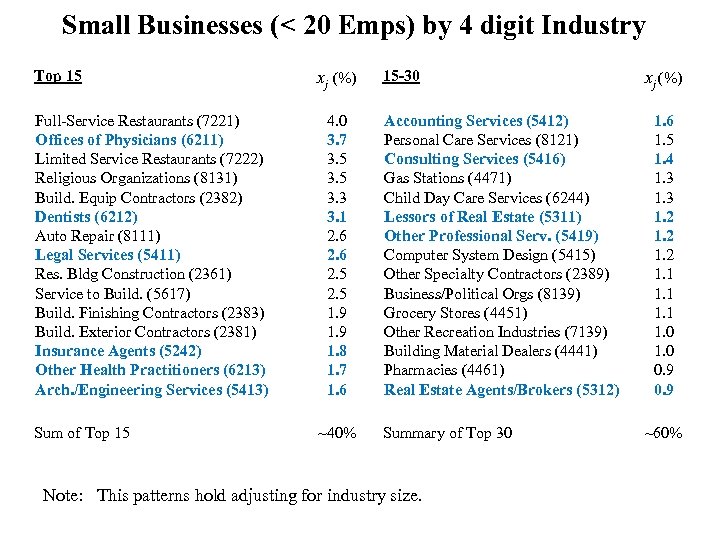

Small Businesses (< 20 Emps) by 4 digit Industry Top 15 Full-Service Restaurants (7221) Offices of Physicians (6211) Limited Service Restaurants (7222) Religious Organizations (8131) Build. Equip Contractors (2382) Dentists (6212) Auto Repair (8111) Legal Services (5411) Res. Bldg Construction (2361) Service to Build. (5617) Build. Finishing Contractors (2383) Build. Exterior Contractors (2381) Insurance Agents (5242) Other Health Practitioners (6213) Arch. /Engineering Services (5413) Sum of Top 15 xj (%) 4. 0 3. 7 3. 5 3. 3 3. 1 2. 6 2. 5 1. 9 1. 8 1. 7 1. 6 ~40% 15 -30 Accounting Services (5412) Personal Care Services (8121) Consulting Services (5416) Gas Stations (4471) Child Day Care Services (6244) Lessors of Real Estate (5311) Other Professional Serv. (5419) Computer System Design (5415) Other Specialty Contractors (2389) Business/Political Orgs (8139) Grocery Stores (4451) Other Recreation Industries (7139) Building Material Dealers (4441) Pharmacies (4461) Real Estate Agents/Brokers (5312) Summary of Top 30 Note: This patterns hold adjusting for industry size. xj (%) 1. 6 1. 5 1. 4 1. 3 1. 2 1. 1 1. 0 0. 9 ~60%

Small Businesses (< 20 Emps) by 4 digit Industry Top 15 Full-Service Restaurants (7221) Offices of Physicians (6211) Limited Service Restaurants (7222) Religious Organizations (8131) Build. Equip Contractors (2382) Dentists (6212) Auto Repair (8111) Legal Services (5411) Res. Bldg Construction (2361) Service to Build. (5617) Build. Finishing Contractors (2383) Build. Exterior Contractors (2381) Insurance Agents (5242) Other Health Practitioners (6213) Arch. /Engineering Services (5413) Sum of Top 15 xj (%) 4. 0 3. 7 3. 5 3. 3 3. 1 2. 6 2. 5 1. 9 1. 8 1. 7 1. 6 ~40% 15 -30 Accounting Services (5412) Personal Care Services (8121) Consulting Services (5416) Gas Stations (4471) Child Day Care Services (6244) Lessors of Real Estate (5311) Other Professional Serv. (5419) Computer System Design (5415) Other Specialty Contractors (2389) Business/Political Orgs (8139) Grocery Stores (4451) Other Recreation Industries (7139) Building Material Dealers (4441) Pharmacies (4461) Real Estate Agents/Brokers (5312) Summary of Top 30 Note: This patterns hold adjusting for industry size. xj (%) 1. 6 1. 5 1. 4 1. 3 1. 2 1. 1 1. 0 0. 9 ~60%

Small Businesses (< 20 Emps) by 4 digit Industry Top 15 Full-Service Restaurants (7221) Offices of Physicians (6211) Limited Service Restaurants (7222) Religious Organizations (8131) Build. Equip Contractors (2382) Dentists (6212) Auto Repair (8111) Legal Services (5411) Res. Bldg Construction (2361) Service to Build. (5617) Build. Finishing Contractors (2383) Build. Exterior Contractors (2381) Insurance Agents (5242) Other Health Practitioners (6213) Arch. /Engineering Services (5413) Sum of Top 15 xj (%) 4. 0 3. 7 3. 5 3. 3 3. 1 2. 6 2. 5 1. 9 1. 8 1. 7 1. 6 ~40% 15 -30 Accounting Services (5412) Personal Care Services (8121) Consulting Services (5416) Gas Stations (4471) Child Day Care Services (6244) Lessors of Real Estate (5311) Other Professional Serv. (5419) Computer System Design (5415) Other Specialty Contractors (2389) Business/Political Orgs (8139) Grocery Stores (4451) Other Recreation Industries (7139) Building Material Dealers (4441) Pharmacies (4461) Real Estate Agents/Brokers (5312) Summary of Top 30 Note: This patterns hold adjusting for industry size. xj (%) 1. 6 1. 5 1. 4 1. 3 1. 2 1. 1 1. 0 0. 9 ~60%

xj vs. within industry share of small firms

Heterogeneity in Ex-Post Small Business Outcomes • Most small businesses do not grow • Most small businesses do not innovate Traditional Explanations - Differences in Luck - Differences in Ability - Differences in Constraints (ability to borrow/self finance)

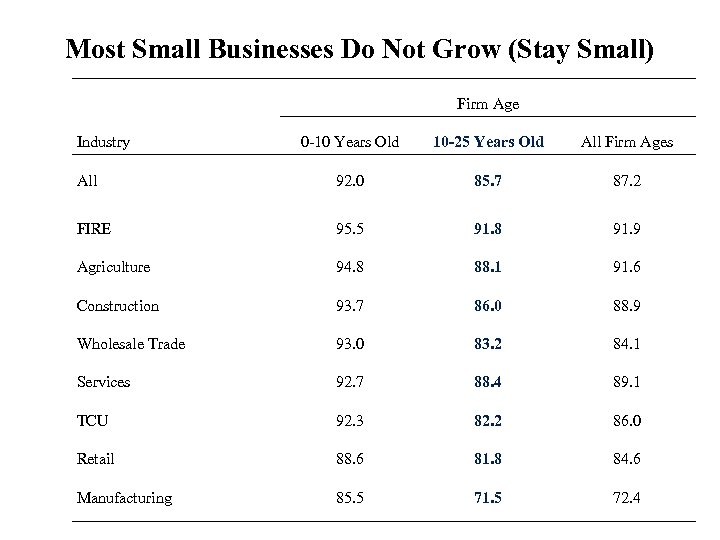

Most Small Businesses Do Not Grow (Stay Small) Firm Age Industry 0 -10 Years Old 10 -25 Years Old All Firm Ages All 92. 0 85. 7 87. 2 FIRE 95. 5 91. 8 91. 9 Agriculture 94. 8 88. 1 91. 6 Construction 93. 7 86. 0 88. 9 Wholesale Trade 93. 0 83. 2 84. 1 Services 92. 7 88. 4 89. 1 TCU 92. 3 82. 2 86. 0 Retail 88. 6 81. 8 84. 6 Manufacturing 85. 5 71. 5 72. 4

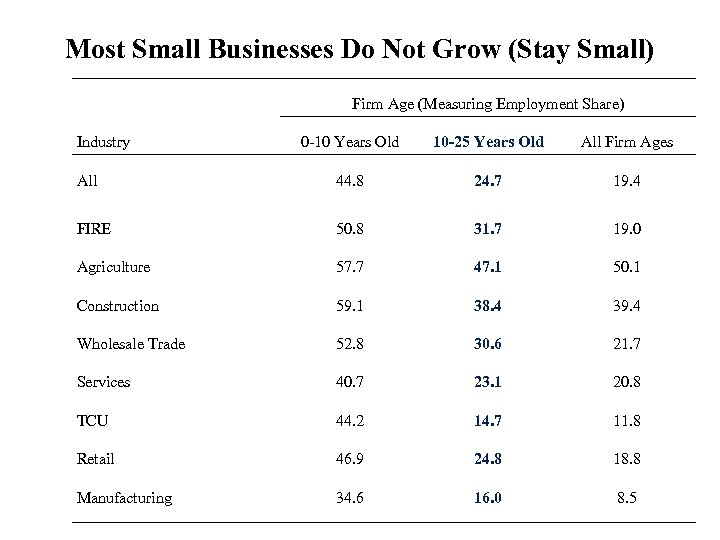

Most Small Businesses Do Not Grow (Stay Small) Firm Age (Measuring Employment Share) Industry 0 -10 Years Old 10 -25 Years Old All Firm Ages All 44. 8 24. 7 19. 4 FIRE 50. 8 31. 7 19. 0 Agriculture 57. 7 47. 1 50. 1 Construction 59. 1 38. 4 39. 4 Wholesale Trade 52. 8 30. 6 21. 7 Services 40. 7 23. 1 20. 8 TCU 44. 2 14. 7 11. 8 Retail 46. 9 24. 8 18. 8 Manufacturing 34. 6 16. 0 8. 5

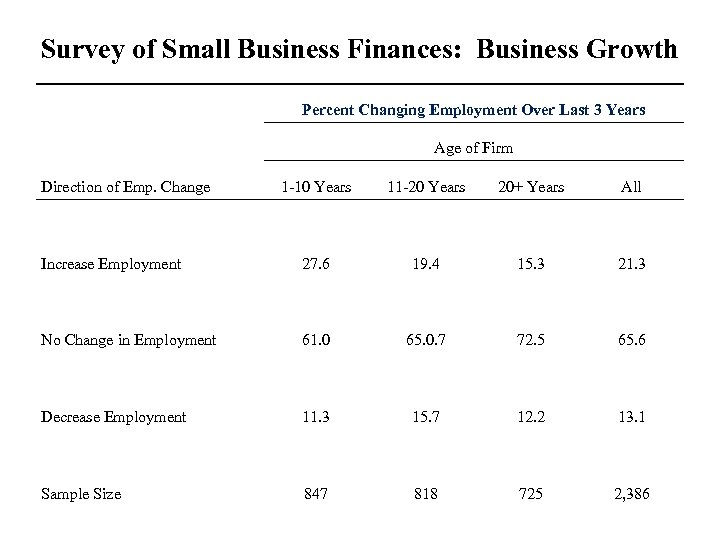

Survey of Small Business Finances: Business Growth Percent Changing Employment Over Last 3 Years Age of Firm Direction of Emp. Change 1 -10 Years 11 -20 Years 20+ Years All Increase Employment 27. 6 19. 4 15. 3 21. 3 No Change in Employment 61. 0 65. 0. 7 72. 5 65. 6 Decrease Employment 11. 3 15. 7 12. 2 13. 1 Sample Size 847 818 725 2, 386

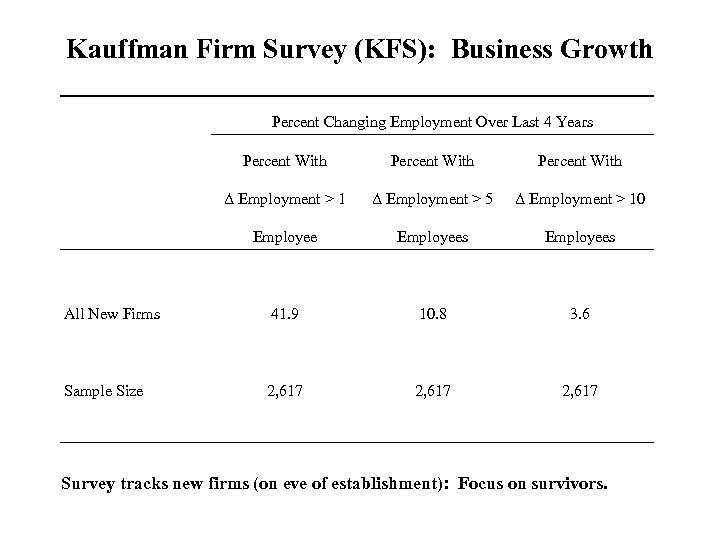

Kauffman Firm Survey (KFS): Business Growth Percent Changing Employment Over Last 4 Years Percent With Δ Employment > 1 Δ Employment > 5 Δ Employment > 10 Employees All New Firms 41. 9 10. 8 3. 6 Sample Size 2, 617 Survey tracks new firms (on eve of establishment): Focus on survivors.

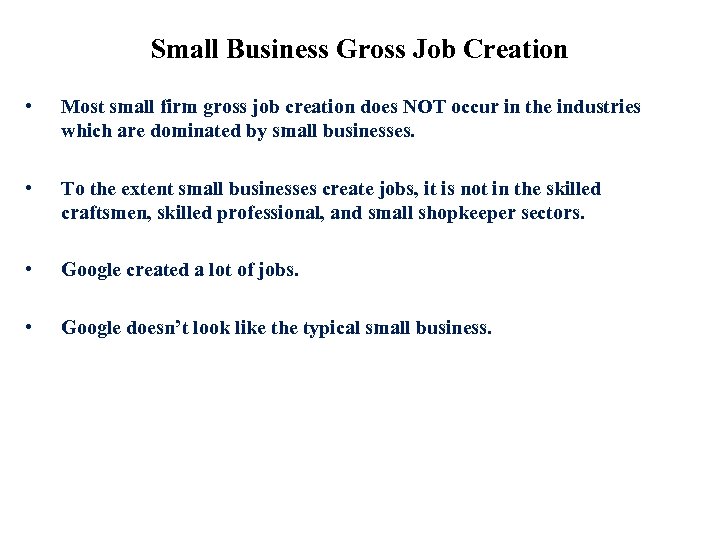

Small Business Gross Job Creation • Most small firm gross job creation does NOT occur in the industries which are dominated by small businesses. • To the extent small businesses create jobs, it is not in the skilled craftsmen, skilled professional, and small shopkeeper sectors. • Google created a lot of jobs. • Google doesn’t look like the typical small business.

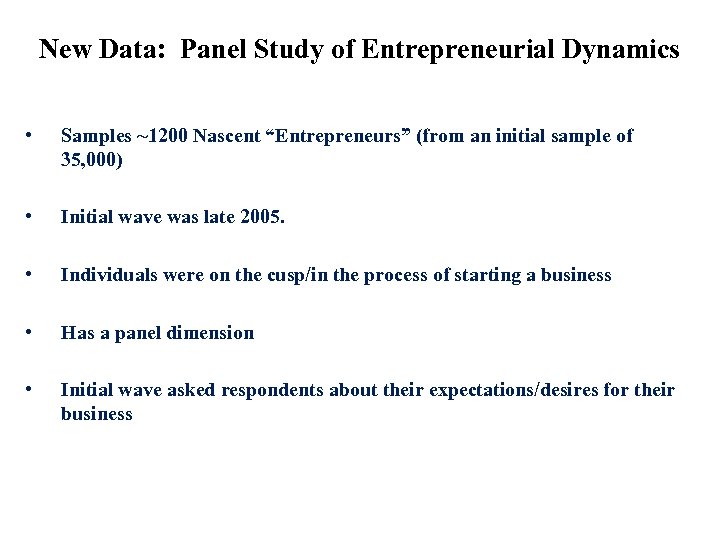

New Data: Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics • Samples ~1200 Nascent “Entrepreneurs” (from an initial sample of 35, 000) • Initial wave was late 2005. • Individuals were on the cusp/in the process of starting a business • Has a panel dimension • Initial wave asked respondents about their expectations/desires for their business

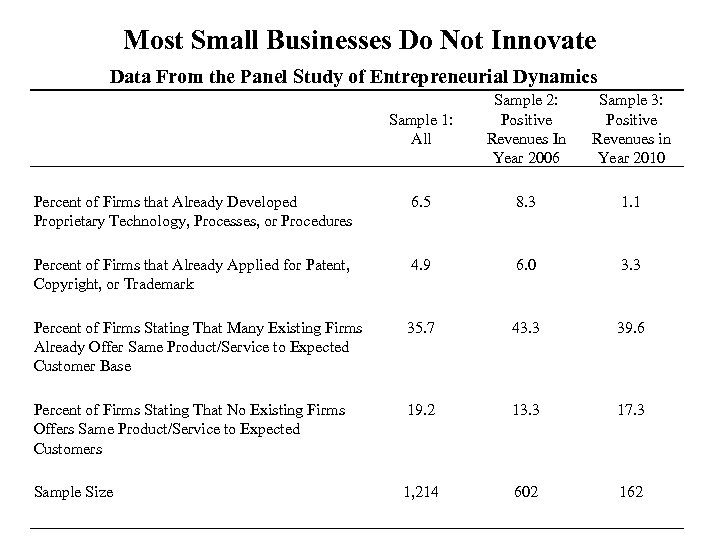

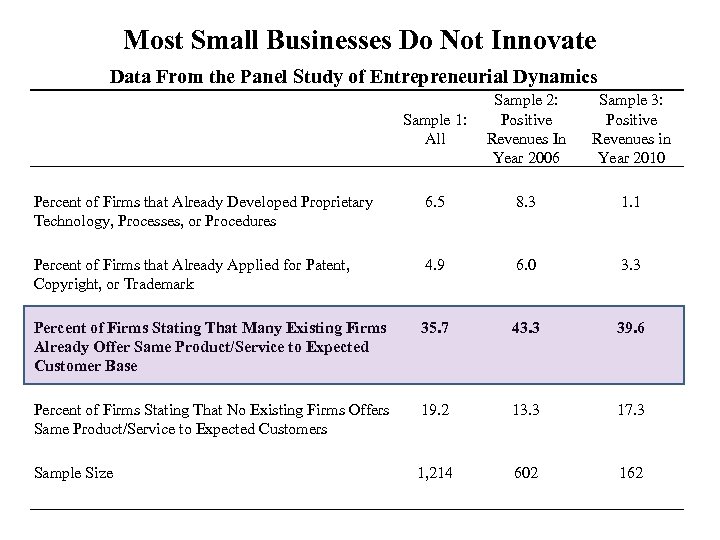

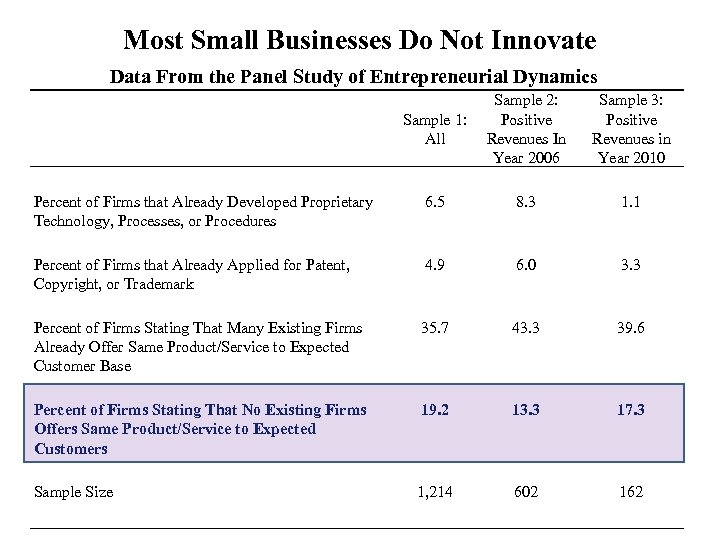

Most Small Businesses Do Not Innovate Data From the Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics Sample 1: All Sample 2: Positive Revenues In Year 2006 Sample 3: Positive Revenues in Year 2010 Percent of Firms that Already Developed Proprietary Technology, Processes, or Procedures 6. 5 8. 3 1. 1 Percent of Firms that Already Applied for Patent, Copyright, or Trademark 4. 9 6. 0 3. 3 Percent of Firms Stating That Many Existing Firms Already Offer Same Product/Service to Expected Customer Base 35. 7 43. 3 39. 6 Percent of Firms Stating That No Existing Firms Offers Same Product/Service to Expected Customers 19. 2 13. 3 17. 3 Sample Size 1, 214 602 162

Most Small Businesses Do Not Innovate Data From the Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics Sample 1: All Sample 2: Positive Revenues In Year 2006 Sample 3: Positive Revenues in Year 2010 Percent of Firms that Already Developed Proprietary Technology, Processes, or Procedures 6. 5 8. 3 1. 1 Percent of Firms that Already Applied for Patent, Copyright, or Trademark 4. 9 6. 0 3. 3 Percent of Firms Stating That Many Existing Firms Already Offer Same Product/Service to Expected Customer Base 35. 7 43. 3 39. 6 Percent of Firms Stating That No Existing Firms Offers Same Product/Service to Expected Customers 19. 2 13. 3 17. 3 Sample Size 1, 214 602 162

Most Small Businesses Do Not Innovate Data From the Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics Sample 1: All Sample 2: Positive Revenues In Year 2006 Sample 3: Positive Revenues in Year 2010 Percent of Firms that Already Developed Proprietary Technology, Processes, or Procedures 6. 5 8. 3 1. 1 Percent of Firms that Already Applied for Patent, Copyright, or Trademark 4. 9 6. 0 3. 3 Percent of Firms Stating That Many Existing Firms Already Offer Same Product/Service to Expected Customer Base 35. 7 43. 3 39. 6 Percent of Firms Stating That No Existing Firms Offers Same Product/Service to Expected Customers 19. 2 13. 3 17. 3 Sample Size 1, 214 602 162

Ex-Ante Heterogeneity in Desires • Most small businesses want to stay small • Most small businesses do not want to innovate

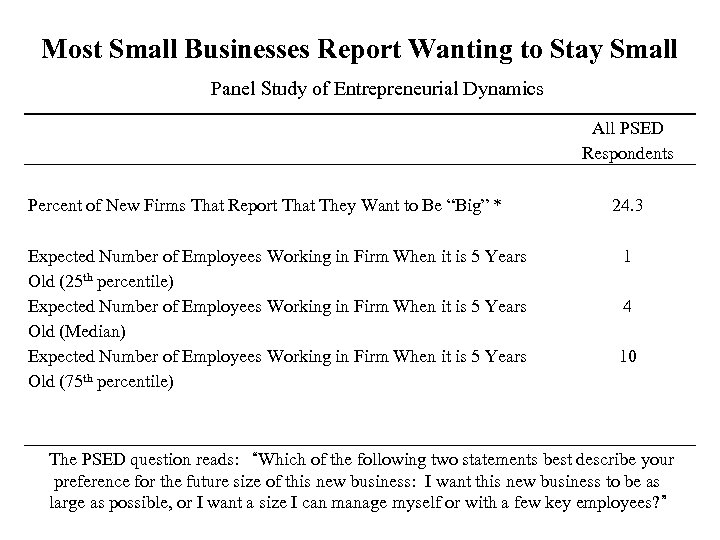

Most Small Businesses Report Wanting to Stay Small Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics All PSED Respondents Percent of New Firms That Report That They Want to Be “Big” * Expected Number of Employees Working in Firm When it is 5 Years Old (25 th percentile) Expected Number of Employees Working in Firm When it is 5 Years Old (Median) Expected Number of Employees Working in Firm When it is 5 Years Old (75 th percentile) 24. 3 1 4 10 The PSED question reads: “Which of the following two statements best describe your preference for the future size of this new business: I want this new business to be as large as possible, or I want a size I can manage myself or with a few key employees? ”

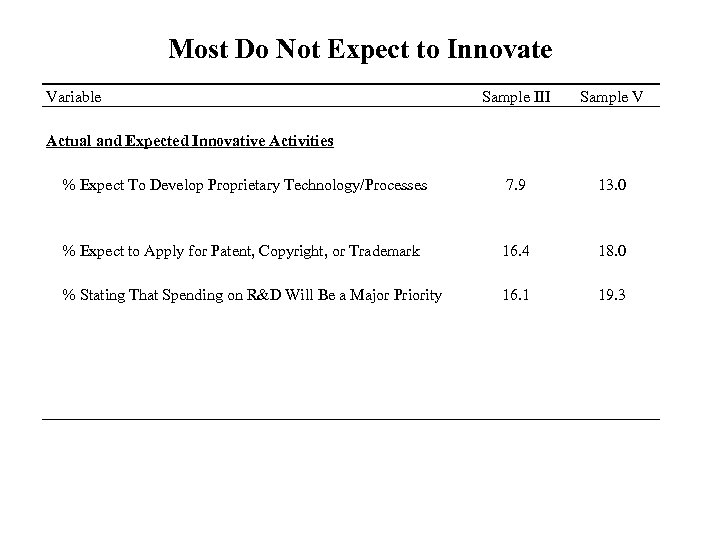

Most Do Not Expect to Innovate Variable Sample III Sample V % Expect To Develop Proprietary Technology/Processes 7. 9 13. 0 % Expect to Apply for Patent, Copyright, or Trademark 16. 4 18. 0 % Stating That Spending on R&D Will Be a Major Priority 16. 1 19. 3 Actual and Expected Innovative Activities

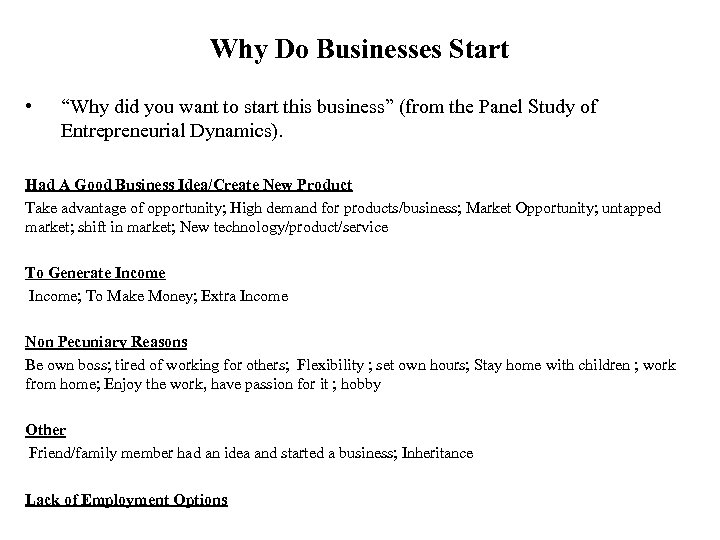

Why Do Businesses Start • “Why did you want to start this business” (from the Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics). Had A Good Business Idea/Create New Product Take advantage of opportunity; High demand for products/business; Market Opportunity; untapped market; shift in market; New technology/product/service To Generate Income; To Make Money; Extra Income Non Pecuniary Reasons Be own boss; tired of working for others; Flexibility ; set own hours; Stay home with children ; work from home; Enjoy the work, have passion for it ; hobby Other Friend/family member had an idea and started a business; Inheritance Lack of Employment Options

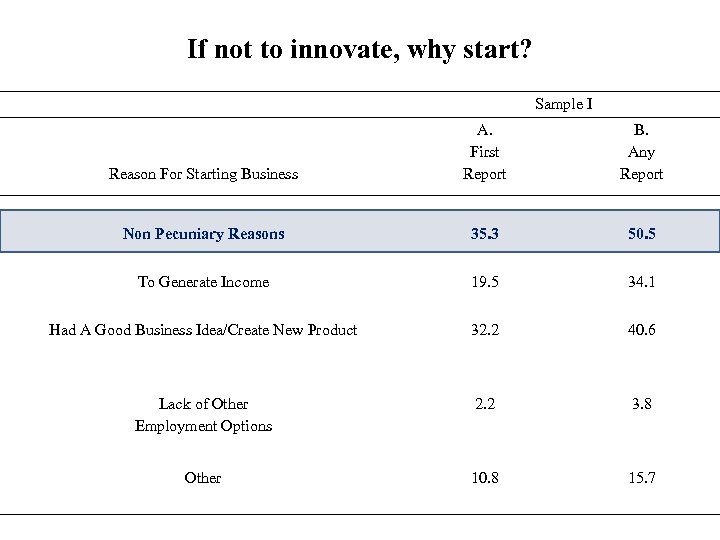

If not to innovate, why start? Sample I Reason For Starting Business A. First Report B. Any Report Non Pecuniary Reasons 35. 3 50. 5 To Generate Income 19. 5 34. 1 Had A Good Business Idea/Create New Product 32. 2 40. 6 Lack of Other Employment Options 2. 2 3. 8 Other 10. 8 15. 7

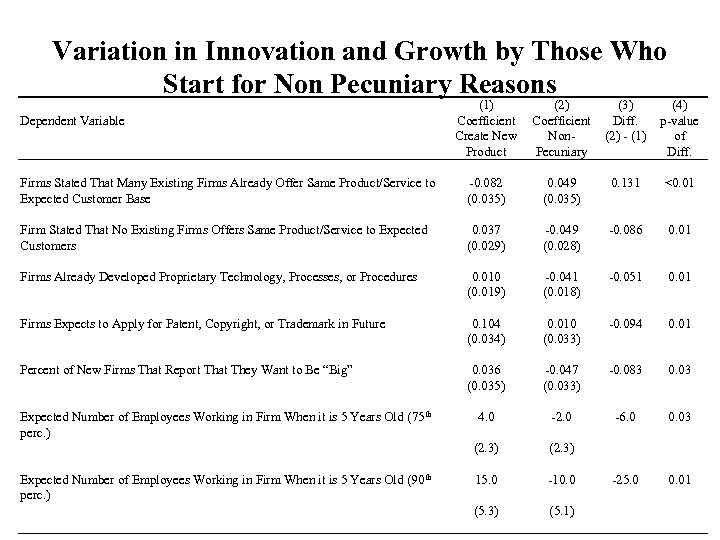

Variation in Innovation and Growth by Those Who Start for Non Pecuniary Reasons Dependent Variable (1) (2) Coefficient Create New Non. Product Pecuniary (3) Diff. (2) - (1) (4) p-value of Diff. Firms Stated That Many Existing Firms Already Offer Same Product/Service to Expected Customer Base -0. 082 (0. 035) 0. 049 (0. 035) 0. 131 <0. 01 Firm Stated That No Existing Firms Offers Same Product/Service to Expected Customers 0. 037 (0. 029) -0. 049 (0. 028) -0. 086 0. 01 Firms Already Developed Proprietary Technology, Processes, or Procedures 0. 010 (0. 019) -0. 041 (0. 018) -0. 051 0. 01 Firms Expects to Apply for Patent, Copyright, or Trademark in Future 0. 104 (0. 034) 0. 010 (0. 033) -0. 094 0. 01 Percent of New Firms That Report That They Want to Be “Big” 0. 036 (0. 035) -0. 047 (0. 033) -0. 083 0. 03 4. 0 -2. 0 -6. 0 0. 03 (2. 3) 15. 0 -10. 0 -25. 0 0. 01 (5. 3) (5. 1) Expected Number of Employees Working in Firm When it is 5 Years Old (75 th perc. ) Expected Number of Employees Working in Firm When it is 5 Years Old (90 th perc. )

Why Do We Care: Part 1 (Academics) • We often write down models trying to explain the distribution of firm size within the U. S. • Most models appeal to: o o Heterogeneity in ability which is revealed after the start up decision. o • Liquidity constraints (some firms do not get access to credit – those that do are the ones that grow). Luck Our work shows that other forces are at play: o o o Most firms have no expectations/desire to grow or innovate. Non pecuniary benefits? Differential scale factors by industry?

Why Do We Care: Part 2 (Policy Makers) • Small businesses are heavily subsidized o o Through tax code Through regulation exemptions Through loan programs Through preferential treatment of government contracts • Justification of policies are usually “growth” and “innovation” • Are there any costs of subsidizing small businesses when “growth” and “innovation” are not the goal of small businesses? • There good be: Pulls resources from “large” business sector. Could result in loss of agglomeration benefits Could be regressive if non-pecuniary benefits are important.

Are non-pecuniary benefits important? • Cannot just rely on survey data. • Explore other metrics. • Are people willing to take a pay cut to be self employed? • Hamilton (2000) • Moskowitz and Vissing-Jorgensen (2002) • Can we believe the income data reported by small business owners in household surveys?

Part 5: Earnings of Self Employed Relative to Earnings as a Worker (From Pugsley 2012 b, “Selection and the Role of Small Business Owners in Firm Dynamics”)

Data on Business and Employee Earnings

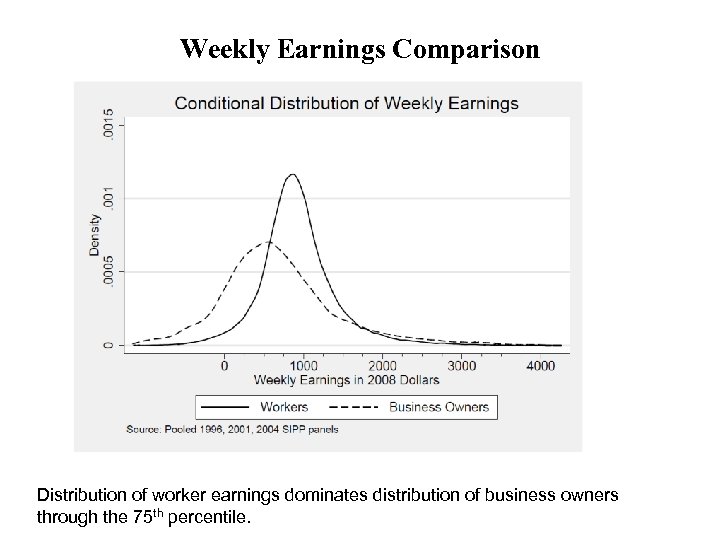

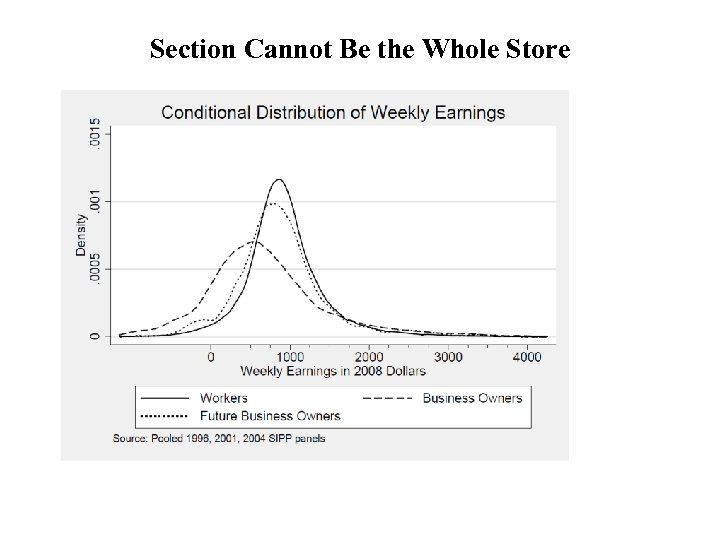

Weekly Earnings Comparison Distribution of worker earnings dominates distribution of business owners through the 75 th percentile.

Data on Business and Employee Earnings

Potential Explanations

Section Cannot Be the Whole Store

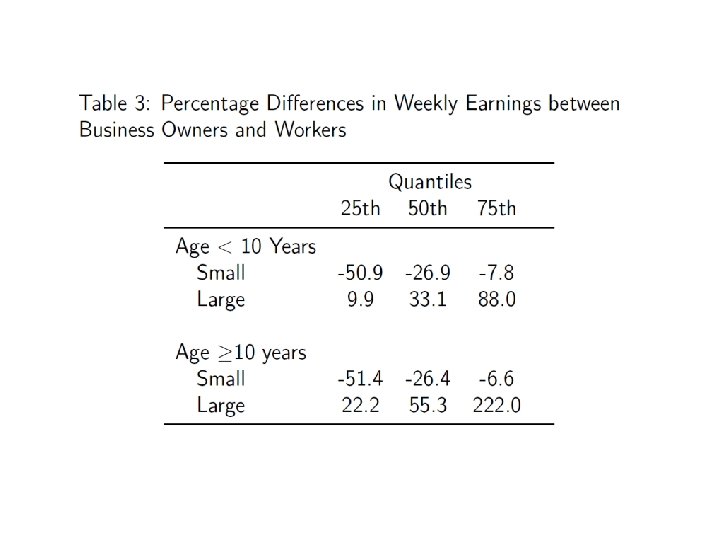

More Conclusions • Business owners earn persistently less than what would have been predicted had they remained a wage worker. o o For the median, this gap is big. At upper deciles, small business owners earn much more. • Median wage gap is another moment that should be calibrated to in structural models of small business dynamics. • Hard to generate without some notion of non-pecuniary benefits. o • Consistent with the survey evidence. Pugsley (2012 b) shows that such preferences are quantitatively important for explaining the mass of small businesses observed in the data (as opposed to either liquidity constraints or productivity draws)

Part 6: “Are Household Surveys Like Tax Forms: Evidence From the Self Employed” (Erik Hurst, Geng Li and Ben Pugsley)

Assumptions We Make • Most researchers, however, assume that individuals or groups of individuals do not systematically misreport information to household surveys. o o We know there is measurement error in household surveys (recall bias). We know there is noise in household surveys (assume it is classical). • Yet, we assume the problems that plague tax data, economic experiments, and administrative data do not plague household survey data. • On the one hand: o • On the other hand: o o Why would people lie to household surveys? Benefits are small Why would people not lie to household surveys? Cost of misreporting is zero Costs may be positive of not misreporting

What This Paper Addresses • Are household surveys akin to tax forms? o o • Do the same problems that plague tax, administrative and experimental data, plague household surveys in that people will misreport information when it is in their incentive to do so? (Yes) If so, by how much? (20%-25%, depending on specification) Focus on the income reporting of the self employed o Why? Large evidence that self employed misreport their income to the tax authorities. o Self employed are a large group. Their misreporting may lead to biases in a wide range of empirical studies. (It is important in variety of settings)

Data 1. PSID (1980 – 1997, excluding years where food data was omitted) o o 2. Food expenditure Detailed income measure CEX (1980 – 2003) o o Detailed expenditure measures Some income measures. Main income measures: Head and Spouse, Wage/Salary + Business Earnings Total family money (After Tax) Self employed measures: Self reported Sample: Male heads, aged 25 -55, working full time (at least 30 hours a week; worked 40 weeks during previous year).

Testing for Underreporting of Income: A Model 1. Assume a log linear Engel Curve between expenditures and permanent income • k indexes wage and salary workers (W) and self employed (S) • Reported income (y*) is a function of permanent income and either transitory variation or classical measurement error. • Estimating (3) with OLS will yield an attenuated estimate of β. 2. Assume education dummies is a good instrument for permanent income in (3). Use pooled data from PSID to average out meas. error.

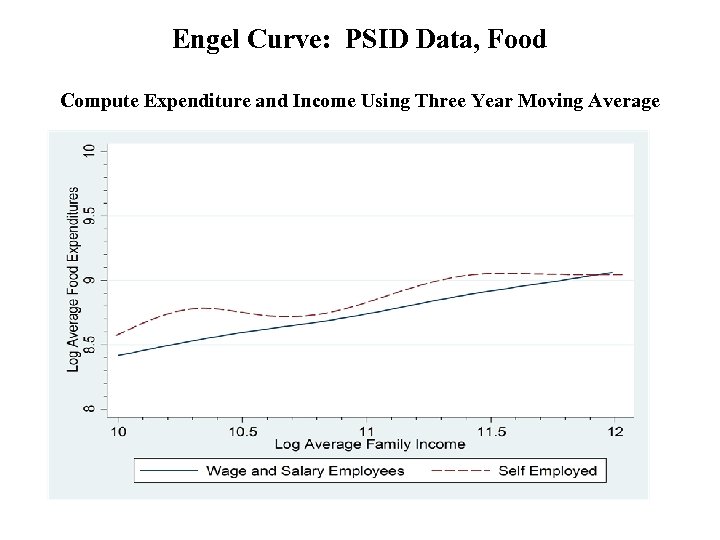

Engel Curve: PSID Data, Food Compute Expenditure and Income Using Three Year Moving Average

Testing For Underreporting 3. Assume self employed misreport their income by κ percent relative to wage and salary workers

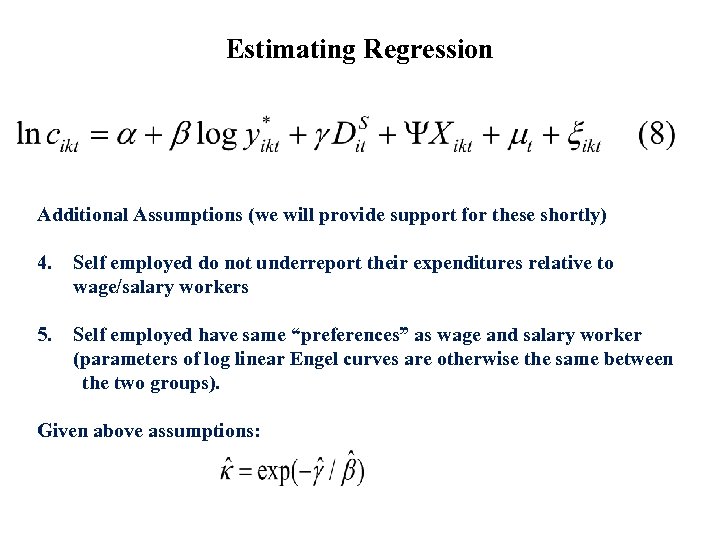

Estimating Regression Additional Assumptions (we will provide support for these shortly) 4. Self employed do not underreport their expenditures relative to wage/salary workers 5. Self employed have same “preferences” as wage and salary worker (parameters of log linear Engel curves are otherwise the same between the two groups). Given above assumptions:

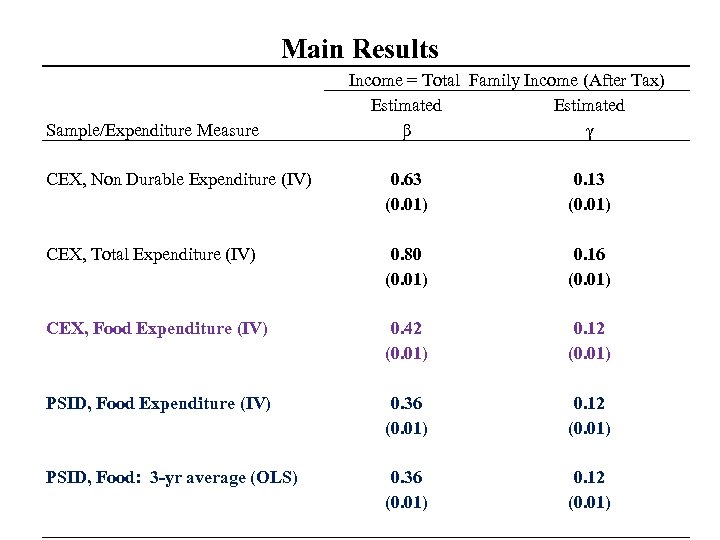

Main Results Sample/Expenditure Measure Income = Total Family Income (After Tax) Estimated β γ CEX, Non Durable Expenditure (IV) 0. 63 (0. 01) 0. 13 (0. 01) CEX, Total Expenditure (IV) 0. 80 (0. 01) 0. 16 (0. 01) CEX, Food Expenditure (IV) 0. 42 (0. 01) 0. 12 (0. 01) PSID, Food Expenditure (IV) 0. 36 (0. 01) 0. 12 (0. 01) PSID, Food: 3 -yr average (OLS) 0. 36 (0. 01) 0. 12 (0. 01)

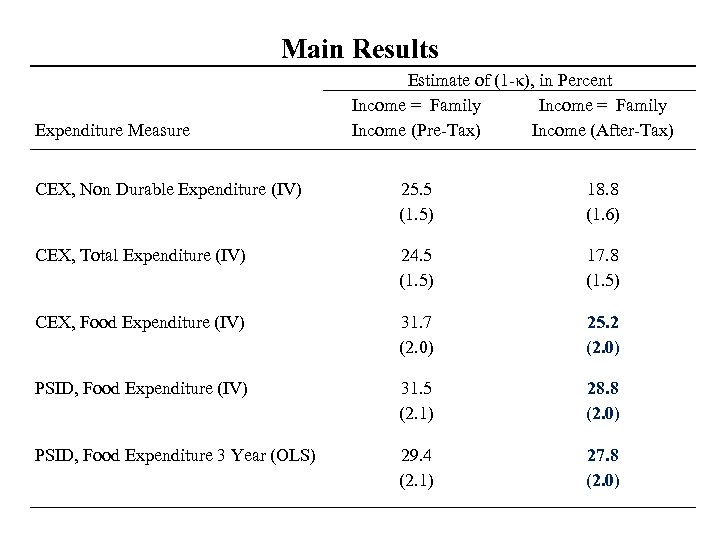

Main Results Expenditure Measure Estimate of (1 -κ), in Percent Income = Family Income (Pre-Tax) Income (After-Tax) CEX, Non Durable Expenditure (IV) 25. 5 (1. 5) 18. 8 (1. 6) CEX, Total Expenditure (IV) 24. 5 (1. 5) 17. 8 (1. 5) CEX, Food Expenditure (IV) 31. 7 (2. 0) 25. 2 (2. 0) PSID, Food Expenditure (IV) 31. 5 (2. 1) 28. 8 (2. 0) PSID, Food Expenditure 3 Year (OLS) 29. 4 (2. 1) 27. 8 (2. 0)

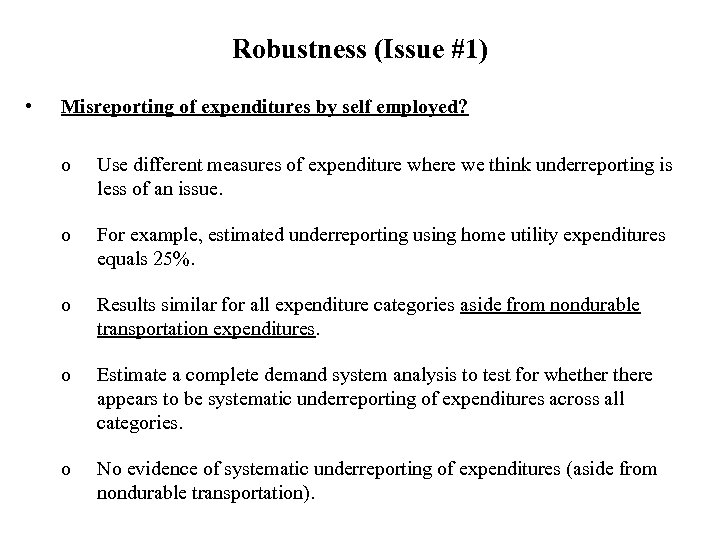

Robustness (Issue #1) • Misreporting of expenditures by self employed? o Use different measures of expenditure where we think underreporting is less of an issue. o For example, estimated underreporting using home utility expenditures equals 25%. o Results similar for all expenditure categories aside from nondurable transportation expenditures. o Estimate a complete demand system analysis to test for whethere appears to be systematic underreporting of expenditures across all categories. o No evidence of systematic underreporting of expenditures (aside from nondurable transportation).

Robustness (Issue #2) • Different Income Concepts of Self Employed o What if the income concepts differ between the self employed and wage/salary workers. o Retained earnings may not be counted as income but they are conceptually equivalent to savings. o Can we rule out that unmeasured retained earnings are driving our results? o Yes – (for the most part). - A large fraction of self employed report no business wealth at all. - Estimate the specifications for those with zero business wealth and more than $10, 000 of business wealth. - No major differences across the groups.

Robustness (Issue #3) • Differences in preferences/expecations/liquidity constraints? o Hard to systematically address. o Some good news: slopes of the Engle curves are roughly the same. o What to see if anything else cause self employed to save more or less for a given level of income. - Binding liquidity constraints (more saving) More uncertainty (more precautionary saving) Difference in risk preferences (less precautionary saving) Higher expected income path (less saving) Difference in home production (more expenditures)

Robustness (Issue #3) • Solutions? o Look at different age ranges. - Budget constraints still must hold – if save more now, should spend more later. - If save for precautionary reasons, should spend as risk diminishes. o Control for work hours (different taste for leisure, differences in home productions). o Test for differences by wealth quartile. - Find no difference in estimated underreporting within each wealth quartile.

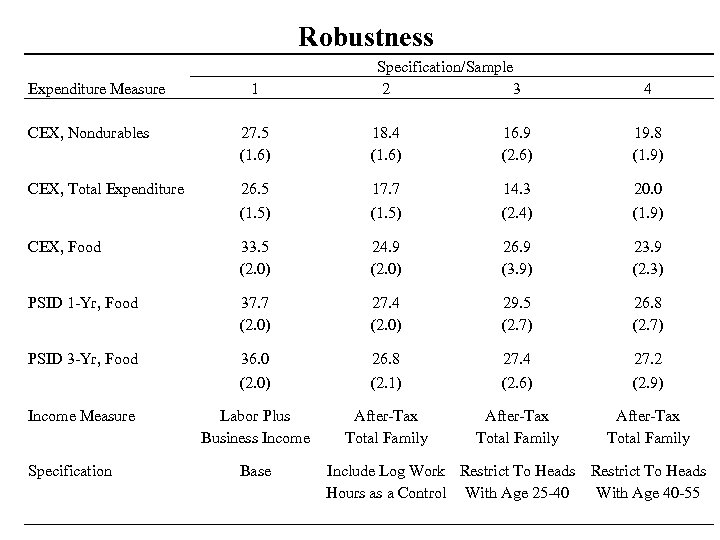

Robustness Expenditure Measure 1 Specification/Sample 2 3 4 CEX, Nondurables 27. 5 (1. 6) 18. 4 (1. 6) 16. 9 (2. 6) 19. 8 (1. 9) CEX, Total Expenditure 26. 5 (1. 5) 17. 7 (1. 5) 14. 3 (2. 4) 20. 0 (1. 9) CEX, Food 33. 5 (2. 0) 24. 9 (2. 0) 26. 9 (3. 9) 23. 9 (2. 3) PSID 1 -Yr, Food 37. 7 (2. 0) 27. 4 (2. 0) 29. 5 (2. 7) 26. 8 (2. 7) PSID 3 -Yr, Food 36. 0 (2. 0) 26. 8 (2. 1) 27. 4 (2. 6) 27. 2 (2. 9) Income Measure Labor Plus Business Income After-Tax Total Family Specification Base Include Log Work Restrict To Heads Hours as a Control With Age 25 -40 With Age 40 -55

Why Does This Matter? 5 Examples 1. Earnings differentials between self employed and wage/salary workers. Hamilton (JPE, 2000): Self employed earn 35% less than wage/salary workers o Does not account for underreporting of income by self employed. o Our results nearly undoes all of Hamilton’s results. o Note: Risk adjusted and accounting for fringe differences, wage/salary workers still earn more.

Why Does This Matter? 5 Examples 2. Wealth Differences Between Self Employed And Wage/Salary Workers • Lots of work on this. Used to provide evidence that liquidity constraints are binding for self employed (business owners, enterpreneurs). o o • Wealth of self employed, conditional on observables including income, is much higher than wealth of wage/salary workers. Underreporting of income by self employed will lower these differentials. How much does this matter? o Use PSID sample: o Account for underreporting: Conditional log wealth differentials ~ 0. 6. Conditional log wealth differentials ~ 0. 9.

Why Does This Matter? 5 Examples 3. Importance of Precautionary Savings o Carroll and Samwick (1997, 1998) show that roughly 50% of the wealth holdings of individuals under the age of 45 is due to precautionary motives. o Regress wealth on measures of risk, average measures of income, and demographics. o Self employed have higher risk and higher wealth. o However, they also underreport their average income. o Scaling up their income accordingly reduces Carroll/Samwick estimates by 13% (from 47. 5% to 41. 1%).

Why Does This Matter? 5 Examples 4. Lifecycle Earnings o Self employment rate changes over the lifecycle (by roughly 15 percentage points between age 25 and 65, 10 percentage points between 45 and 65). o As a result, systematic measurement error differs across the lifecycle. o How much of the decline in income after middle age is due to increased underreporting of income? o About 9% of the decline in earnings between 45 and 65 is due to misreporting of income by self employed. ( 3 percentage points out of the 35 percentage points decline). - Comparable numbers: ~5% in PSID and ~13% in CPS.

Why Does This Matter? 5 Examples 5. Spatial Differences in Earnings o Self employment propensities differ across space (Glaeser 2009). (Mean self employment rate across U. S. MSAs in 2000 census = 0. 125 (standard error = 0. 029)). o To the extent that self employed underreport their income, spatial differences in income could be biased. o Some examples (using 2000 census) - Using reported income, Nassau County (NYC) had 8. 9% higher earnings than Detroit. However, after our adjustment, the difference was 10. 6%. - Likewise, unadjusted San Fran had 23. 9% higher income than Buffalo. With the adjustment, that difference was 25. 5%.

More Conclusions • Survey data faces the same potential problems with respect to systematic measurement error as other types of data (tax data, other administrative data, experimental data, etc. ). • We focus on the self employed. • Self employed underreport their income by ~25% in household surveys. • Some evidence of variation with tax regimes and education levels (although, it is weak). • Not accounting for the underreporting biases many types of empirical works. The extent of the quantitative importance depends on the application. • It is naive to assume that individuals will automatically provide accurate information to household surveys when they are simultaneously providing distorted information to other sources.

Overall Conclusions • Most small businesses are plumbers, small shop keepers, dentists, real estate agents, etc. Should inform the models we bring to this data. • Most small businesses do not want to grow/innovate when starting their business (just provide a similar service to what others are currently providing to the market). • Evidence that non-pecuniary benefits are important to small business formation (survey results and wage gaps). • Evidence that liquidity constraints are an important deterrent to small business formation is hard to find. • Robust evidence that small business owners underreport their income to household surveys. 115

f518643e1ca0e64b2a42b4d74ee8c499.ppt