Review_Lecture.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 59

English Lexicology: A Review Lecture Assist. Prof. Daria Yu. Kuznyetsova Ph. D (Linguistics) May 13, 2011

English Lexicology: A Review Lecture Assist. Prof. Daria Yu. Kuznyetsova Ph. D (Linguistics) May 13, 2011

Plan n Etymological Survey of the English Language. n Means of Word-formation in Modern English. n Semantic Structure of a Word. Polysemy. n Lexico-semantic Differentiation of the English Vocabulary. Synonymy. Antonymy. n English Phraseology. Approaches to the Classification of Phraseological Units.

Plan n Etymological Survey of the English Language. n Means of Word-formation in Modern English. n Semantic Structure of a Word. Polysemy. n Lexico-semantic Differentiation of the English Vocabulary. Synonymy. Antonymy. n English Phraseology. Approaches to the Classification of Phraseological Units.

Assigned Literature n n n n Антрушина Г. Б. , Афанасьева О. В, Морозова Н. Н. Лексикология английского языка. – M. : Дрофа, 2004. Арнольд И. В. Лексикология современного английского языка: Учеб. для ин-тов и фак. иностр. яз. – 3 -е изд. , перераб. и доп. – М. : Высш. шк. , 1986. Елисеева В. Лексикология английского языка: Учебник. – СПб: СПб. ГУ, 2003. Лексикология английского языка: Учебник для ин-тов и фак. иностр. яз. / Р. 3. Гинзбург, С. С. Хидекель, Г. Ю. Князева и А. А. Санкин. – 2 -е изд. , испр. и доп. – М. : Высш. школа, 1979. Смирницкий А. І. Лексикология английского языка. – М. : Издательство литературы на иностранных языках, 1956. Харитончик З. А. Лексикология английского языка. – Минск, 1992. Crystal D. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. – Cambridge University Press, 1995. Rayevska N. M. English Lexicology. – K. : Vyssha skola, 1971.

Assigned Literature n n n n Антрушина Г. Б. , Афанасьева О. В, Морозова Н. Н. Лексикология английского языка. – M. : Дрофа, 2004. Арнольд И. В. Лексикология современного английского языка: Учеб. для ин-тов и фак. иностр. яз. – 3 -е изд. , перераб. и доп. – М. : Высш. шк. , 1986. Елисеева В. Лексикология английского языка: Учебник. – СПб: СПб. ГУ, 2003. Лексикология английского языка: Учебник для ин-тов и фак. иностр. яз. / Р. 3. Гинзбург, С. С. Хидекель, Г. Ю. Князева и А. А. Санкин. – 2 -е изд. , испр. и доп. – М. : Высш. школа, 1979. Смирницкий А. І. Лексикология английского языка. – М. : Издательство литературы на иностранных языках, 1956. Харитончик З. А. Лексикология английского языка. – Минск, 1992. Crystal D. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. – Cambridge University Press, 1995. Rayevska N. M. English Lexicology. – K. : Vyssha skola, 1971.

English Vocabulary: General Considerations n n the native stock of words (25 -30%) – words known from the earliest available manuscripts of the Old English period; they were brought to the British Isles from the continent in the 5 th century AD by the Germanic tribes of the Angles, the Saxons and the Jutes; the borrowed stock of words (70 -75%) – words taken over from other languages and modified in phonetic shape, spelling, paradigm or / and meaning according to the standards of the English language.

English Vocabulary: General Considerations n n the native stock of words (25 -30%) – words known from the earliest available manuscripts of the Old English period; they were brought to the British Isles from the continent in the 5 th century AD by the Germanic tribes of the Angles, the Saxons and the Jutes; the borrowed stock of words (70 -75%) – words taken over from other languages and modified in phonetic shape, spelling, paradigm or / and meaning according to the standards of the English language.

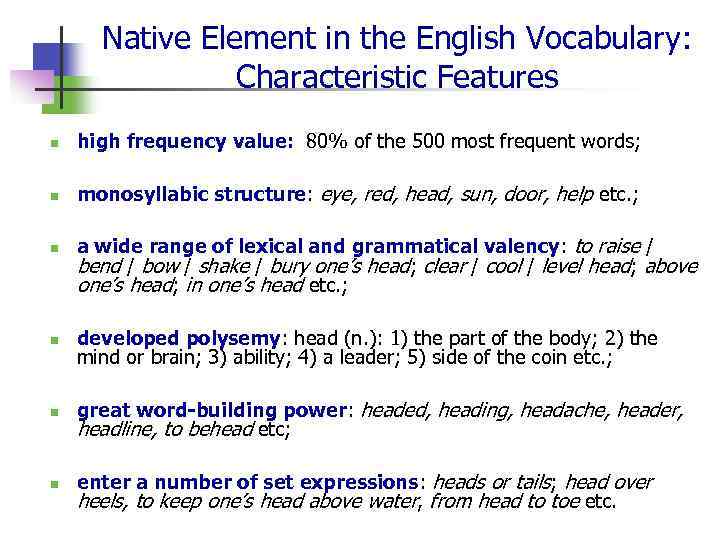

Native Element in the English Vocabulary: Characteristic Features n high frequency value: 80% of the 500 most frequent words; n monosyllabic structure: eye, red, head, sun, door, help etc. ; n a wide range of lexical and grammatical valency: to raise / bend / bow / shake / bury one’s head; clear / cool / level head; above one’s head; in one’s head etc. ; n developed polysemy: head (n. ): 1) the part of the body; 2) the mind or brain; 3) ability; 4) a leader; 5) side of the coin etc. ; n great word-building power: headed, heading, headache, header, headline, to behead etc; n enter a number of set expressions: heads or tails; head over heels, to keep one’s head above water, from head to toe etc.

Native Element in the English Vocabulary: Characteristic Features n high frequency value: 80% of the 500 most frequent words; n monosyllabic structure: eye, red, head, sun, door, help etc. ; n a wide range of lexical and grammatical valency: to raise / bend / bow / shake / bury one’s head; clear / cool / level head; above one’s head; in one’s head etc. ; n developed polysemy: head (n. ): 1) the part of the body; 2) the mind or brain; 3) ability; 4) a leader; 5) side of the coin etc. ; n great word-building power: headed, heading, headache, header, headline, to behead etc; n enter a number of set expressions: heads or tails; head over heels, to keep one’s head above water, from head to toe etc.

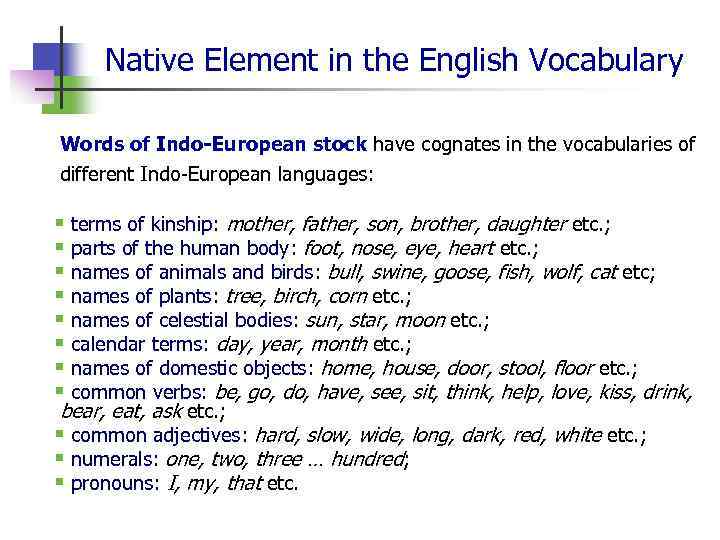

Native Element in the English Vocabulary Words of Indo-European stock have cognates in the vocabularies of different Indo-European languages: § terms of kinship: mother, father, son, brother, daughter etc. ; § parts of the human body: foot, nose, eye, heart etc. ; § names of animals and birds: bull, swine, goose, fish, wolf, cat etc; § names of plants: tree, birch, corn etc. ; § names of celestial bodies: sun, star, moon etc. ; § calendar terms: day, year, month etc. ; § names of domestic objects: home, house, door, stool, floor etc. ; § common verbs: be, go, do, have, see, sit, think, help, love, kiss, drink, bear, eat, ask etc. ; § common adjectives: hard, slow, wide, long, dark, red, white etc. ; § numerals: one, two, three … hundred; § pronouns: I, my, that etc.

Native Element in the English Vocabulary Words of Indo-European stock have cognates in the vocabularies of different Indo-European languages: § terms of kinship: mother, father, son, brother, daughter etc. ; § parts of the human body: foot, nose, eye, heart etc. ; § names of animals and birds: bull, swine, goose, fish, wolf, cat etc; § names of plants: tree, birch, corn etc. ; § names of celestial bodies: sun, star, moon etc. ; § calendar terms: day, year, month etc. ; § names of domestic objects: home, house, door, stool, floor etc. ; § common verbs: be, go, do, have, see, sit, think, help, love, kiss, drink, bear, eat, ask etc. ; § common adjectives: hard, slow, wide, long, dark, red, white etc. ; § numerals: one, two, three … hundred; § pronouns: I, my, that etc.

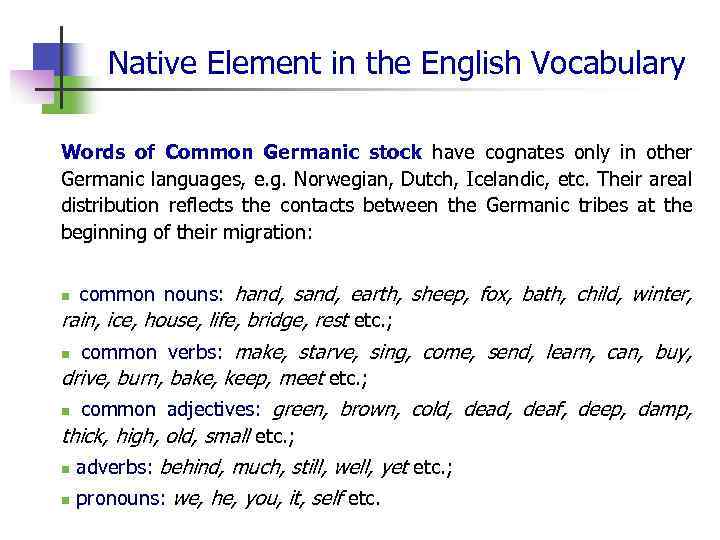

Native Element in the English Vocabulary Words of Common Germanic stock have cognates only in other Germanic languages, e. g. Norwegian, Dutch, Icelandic, etc. Their areal distribution reflects the contacts between the Germanic tribes at the beginning of their migration: common nouns: hand, sand, earth, sheep, fox, bath, child, winter, rain, ice, house, life, bridge, rest etc. ; n common verbs: make, starve, sing, come, send, learn, can, buy, drive, burn, bake, keep, meet etc. ; n common adjectives: green, brown, cold, deaf, deep, damp, thick, high, old, small etc. ; n n adverbs: behind, much, still, well, yet etc. ; n pronouns: we, he, you, it, self etc.

Native Element in the English Vocabulary Words of Common Germanic stock have cognates only in other Germanic languages, e. g. Norwegian, Dutch, Icelandic, etc. Their areal distribution reflects the contacts between the Germanic tribes at the beginning of their migration: common nouns: hand, sand, earth, sheep, fox, bath, child, winter, rain, ice, house, life, bridge, rest etc. ; n common verbs: make, starve, sing, come, send, learn, can, buy, drive, burn, bake, keep, meet etc. ; n common adjectives: green, brown, cold, deaf, deep, damp, thick, high, old, small etc. ; n n adverbs: behind, much, still, well, yet etc. ; n pronouns: we, he, you, it, self etc.

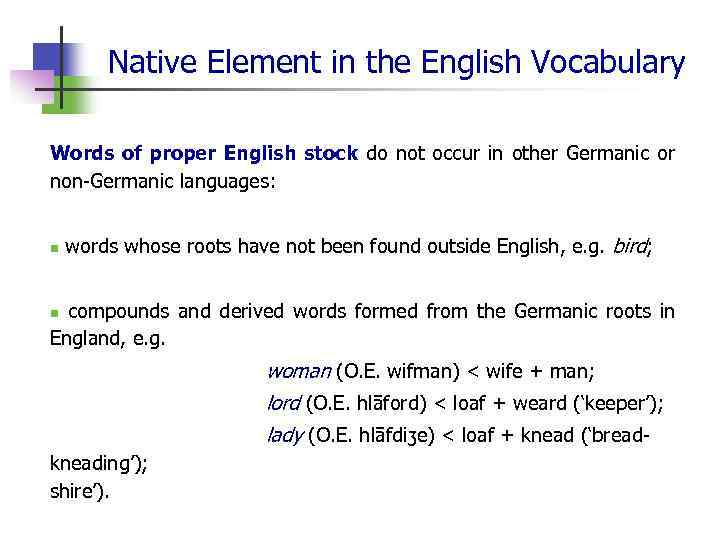

Native Element in the English Vocabulary Words of proper English stock do not occur in other Germanic or non-Germanic languages: n words whose roots have not been found outside English, e. g. bird; compounds and derived words formed from the Germanic roots in England, e. g. n woman (O. E. wifman) < wife + man; lord (O. E. hlāford) < loaf + weard (‘keeper’); lady (O. E. hlāfdiʒe) < loaf + knead (‘breadkneading’); shire’).

Native Element in the English Vocabulary Words of proper English stock do not occur in other Germanic or non-Germanic languages: n words whose roots have not been found outside English, e. g. bird; compounds and derived words formed from the Germanic roots in England, e. g. n woman (O. E. wifman) < wife + man; lord (O. E. hlāford) < loaf + weard (‘keeper’); lady (O. E. hlāfdiʒe) < loaf + knead (‘breadkneading’); shire’).

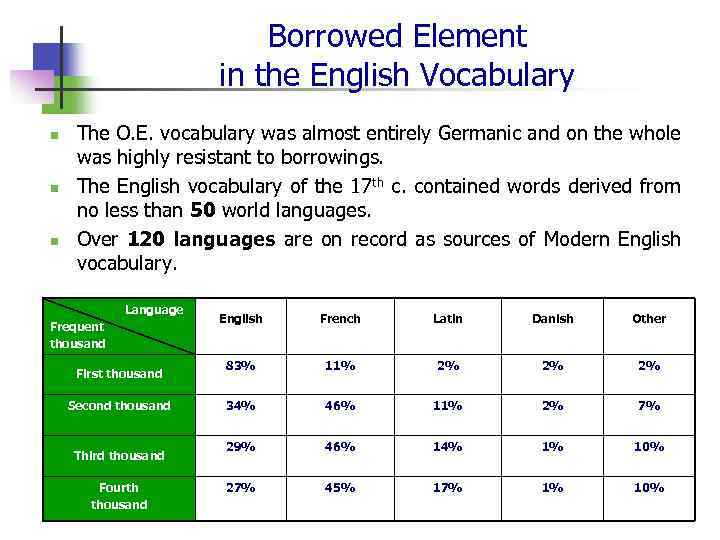

Borrowed Element in the English Vocabulary n n n The O. E. vocabulary was almost entirely Germanic and on the whole was highly resistant to borrowings. The English vocabulary of the 17 th c. contained words derived from no less than 50 world languages. Over 120 languages are on record as sources of Modern English vocabulary. Language Frequent thousand First thousand Second thousand Third thousand Fourth thousand English French Latin Danish Other 83% 11% 2% 2% 2% 34% 46% 11% 2% 7% 29% 46% 14% 1% 10% 27% 45% 17% 1% 10%

Borrowed Element in the English Vocabulary n n n The O. E. vocabulary was almost entirely Germanic and on the whole was highly resistant to borrowings. The English vocabulary of the 17 th c. contained words derived from no less than 50 world languages. Over 120 languages are on record as sources of Modern English vocabulary. Language Frequent thousand First thousand Second thousand Third thousand Fourth thousand English French Latin Danish Other 83% 11% 2% 2% 2% 34% 46% 11% 2% 7% 29% 46% 14% 1% 10% 27% 45% 17% 1% 10%

Borrowed Element in the English Vocabulary Motivation for borrowing a word: n n n to fill a gap in the vocabulary, e. g. butter (Latin), yogurt (Turkish), whisky (Scottish Gaelic), tomato (Nahuatl /’na: watl/ - the Aztec language), sauna ( /’so: nə/ Finnish) etc. ; to represent the same concept in a new aspect, supplying a new shade of meaning or a different emotional colouring, e. g. cordial (Latin), a desire (French), to admire (Latin) etc. ; prestige, e. g. picture, courage, army, treasure, language, female, face, fool, beef (Norman French); in many cases these fashionable words simply displaced their native English equivalents, which dropped out of use.

Borrowed Element in the English Vocabulary Motivation for borrowing a word: n n n to fill a gap in the vocabulary, e. g. butter (Latin), yogurt (Turkish), whisky (Scottish Gaelic), tomato (Nahuatl /’na: watl/ - the Aztec language), sauna ( /’so: nə/ Finnish) etc. ; to represent the same concept in a new aspect, supplying a new shade of meaning or a different emotional colouring, e. g. cordial (Latin), a desire (French), to admire (Latin) etc. ; prestige, e. g. picture, courage, army, treasure, language, female, face, fool, beef (Norman French); in many cases these fashionable words simply displaced their native English equivalents, which dropped out of use.

Assimilation of Borrowings The term assimilation of a loan word is used to denote a partial or total conformation to the phonetical, graphical, and morphological standards of the receiving language and its semantic system. The term type of assimilation refers to the changes an adopted word may undergo: n phonetic assimilation; n graphical assimilation; n grammatical assimilation; n semantic assimilation. The degree of assimilation depends upon the period of time during which the word has been used in the receiving language, its communicative importance and frequency: n completely assimilated loans; n partially assimilated loans; n non-assimilated loans (barbarisms).

Assimilation of Borrowings The term assimilation of a loan word is used to denote a partial or total conformation to the phonetical, graphical, and morphological standards of the receiving language and its semantic system. The term type of assimilation refers to the changes an adopted word may undergo: n phonetic assimilation; n graphical assimilation; n grammatical assimilation; n semantic assimilation. The degree of assimilation depends upon the period of time during which the word has been used in the receiving language, its communicative importance and frequency: n completely assimilated loans; n partially assimilated loans; n non-assimilated loans (barbarisms).

Assimilation of Borrowings Completely assimilated loan-words are found at all the layers of older borrowings: cheese, street, wall, wine; gate, wing, die, take, happy, ill, low, odd, wrong. Partially assimilated loan-words: n not assimilated semantically: sheik, sherbet; n not assimilated grammatically: crisis – crises, formula – formulae ; n not assimilated phonetically: the final syllable is stressed (machine, cartoon, police); /ʒ/ - beige, prestige, regime; /wα: / – memoir; n not assimilated graphically: last consonant is not pronounced (ballet, buffet, debut); a diacritic mark (café, cliché); have specific diagraphs (bouquet, brioche). Barbarisms are words not assimilated in any way and for which there are corresponding English equivalents: It. addio, ciao; Fr. tête-à-tête.

Assimilation of Borrowings Completely assimilated loan-words are found at all the layers of older borrowings: cheese, street, wall, wine; gate, wing, die, take, happy, ill, low, odd, wrong. Partially assimilated loan-words: n not assimilated semantically: sheik, sherbet; n not assimilated grammatically: crisis – crises, formula – formulae ; n not assimilated phonetically: the final syllable is stressed (machine, cartoon, police); /ʒ/ - beige, prestige, regime; /wα: / – memoir; n not assimilated graphically: last consonant is not pronounced (ballet, buffet, debut); a diacritic mark (café, cliché); have specific diagraphs (bouquet, brioche). Barbarisms are words not assimilated in any way and for which there are corresponding English equivalents: It. addio, ciao; Fr. tête-à-tête.

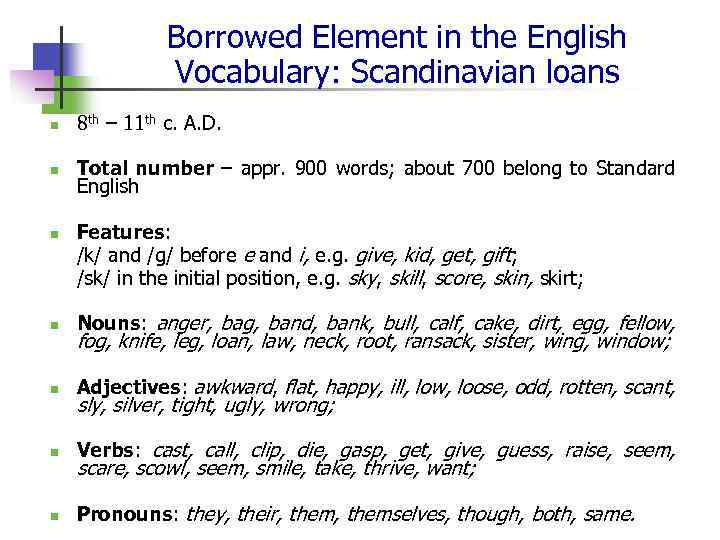

Borrowed Element in the English Vocabulary: Scandinavian loans n 8 th – 11 th c. A. D. n Total number – appr. 900 words; about 700 belong to Standard English n Features: /k/ and /g/ before e and i, e. g. give, kid, get, gift; /sk/ in the initial position, e. g. sky, skill, score, skin, skirt; n Nouns: anger, bag, band, bank, bull, calf, cake, dirt, egg, fellow, n Adjectives: awkward, flat, happy, ill, low, loose, odd, rotten, scant, n Verbs: cast, call, clip, die, gasp, get, give, guess, raise, seem, n Pronouns: they, their, themselves, though, both, same. fog, knife, leg, loan, law, neck, root, ransack, sister, wing, window; sly, silver, tight, ugly, wrong; scare, scowl, seem, smile, take, thrive, want;

Borrowed Element in the English Vocabulary: Scandinavian loans n 8 th – 11 th c. A. D. n Total number – appr. 900 words; about 700 belong to Standard English n Features: /k/ and /g/ before e and i, e. g. give, kid, get, gift; /sk/ in the initial position, e. g. sky, skill, score, skin, skirt; n Nouns: anger, bag, band, bank, bull, calf, cake, dirt, egg, fellow, n Adjectives: awkward, flat, happy, ill, low, loose, odd, rotten, scant, n Verbs: cast, call, clip, die, gasp, get, give, guess, raise, seem, n Pronouns: they, their, themselves, though, both, same. fog, knife, leg, loan, law, neck, root, ransack, sister, wing, window; sly, silver, tight, ugly, wrong; scare, scowl, seem, smile, take, thrive, want;

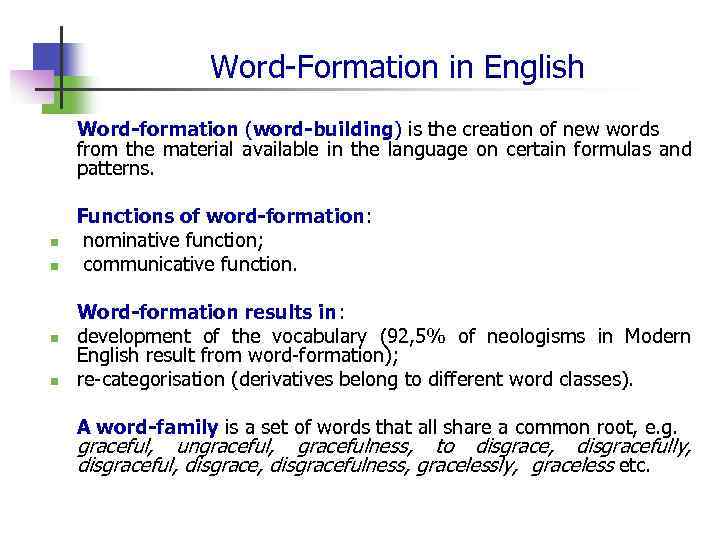

Word-Formation in English Word-formation (word-building) is the creation of new words from the material available in the language on certain formulas and patterns. n n Functions of word-formation: nominative function; communicative function. Word-formation results in: development of the vocabulary (92, 5% of neologisms in Modern English result from word-formation); re-categorisation (derivatives belong to different word classes). A word-family is a set of words that all share a common root, e. g. graceful, ungraceful, gracefulness, to disgrace, disgracefully, disgraceful, disgracefulness, gracelessly, graceless etc.

Word-Formation in English Word-formation (word-building) is the creation of new words from the material available in the language on certain formulas and patterns. n n Functions of word-formation: nominative function; communicative function. Word-formation results in: development of the vocabulary (92, 5% of neologisms in Modern English result from word-formation); re-categorisation (derivatives belong to different word classes). A word-family is a set of words that all share a common root, e. g. graceful, ungraceful, gracefulness, to disgrace, disgracefully, disgraceful, disgracefulness, gracelessly, graceless etc.

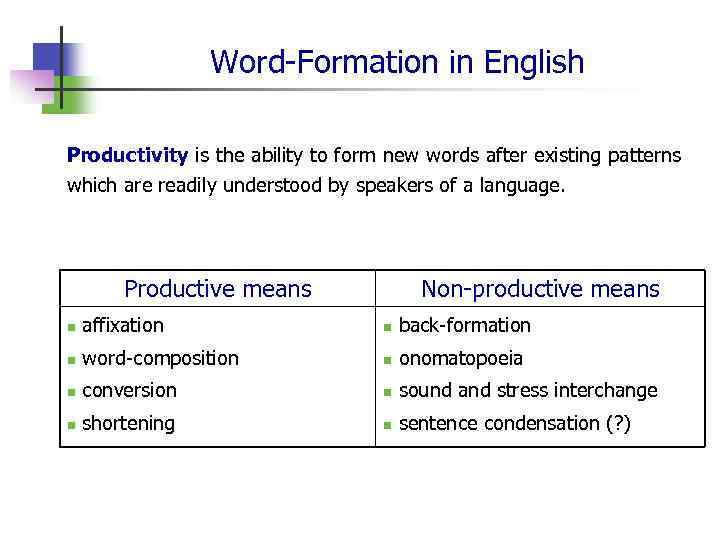

Word-Formation in English Productivity is the ability to form new words after existing patterns which are readily understood by speakers of a language. Productive means Non-productive means n affixation n back-formation n word-composition n onomatopoeia n conversion n sound and stress interchange n shortening n sentence condensation (? )

Word-Formation in English Productivity is the ability to form new words after existing patterns which are readily understood by speakers of a language. Productive means Non-productive means n affixation n back-formation n word-composition n onomatopoeia n conversion n sound and stress interchange n shortening n sentence condensation (? )

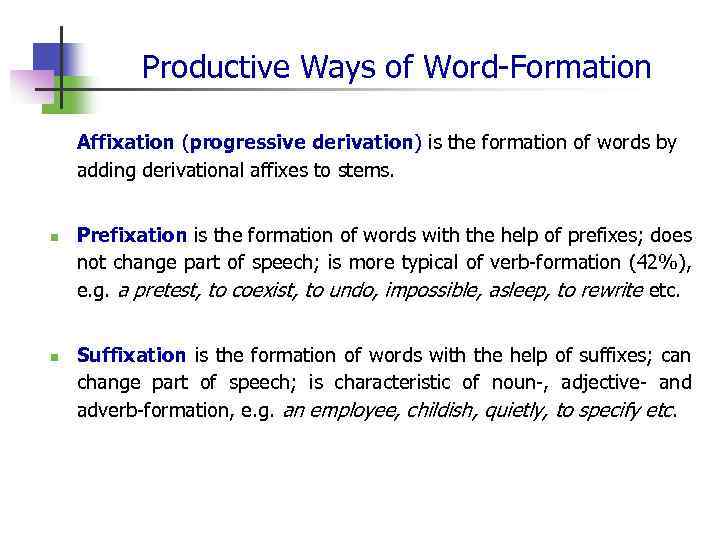

Productive Ways of Word-Formation Affixation (progressive derivation) is the formation of words by adding derivational affixes to stems. n n Prefixation is the formation of words with the help of prefixes; does not change part of speech; is more typical of verb-formation (42%), e. g. a pretest, to coexist, to undo, impossible, asleep, to rewrite etc. Suffixation is the formation of words with the help of suffixes; can change part of speech; is characteristic of noun-, adjective- and adverb-formation, e. g. an employee, childish, quietly, to specify etc.

Productive Ways of Word-Formation Affixation (progressive derivation) is the formation of words by adding derivational affixes to stems. n n Prefixation is the formation of words with the help of prefixes; does not change part of speech; is more typical of verb-formation (42%), e. g. a pretest, to coexist, to undo, impossible, asleep, to rewrite etc. Suffixation is the formation of words with the help of suffixes; can change part of speech; is characteristic of noun-, adjective- and adverb-formation, e. g. an employee, childish, quietly, to specify etc.

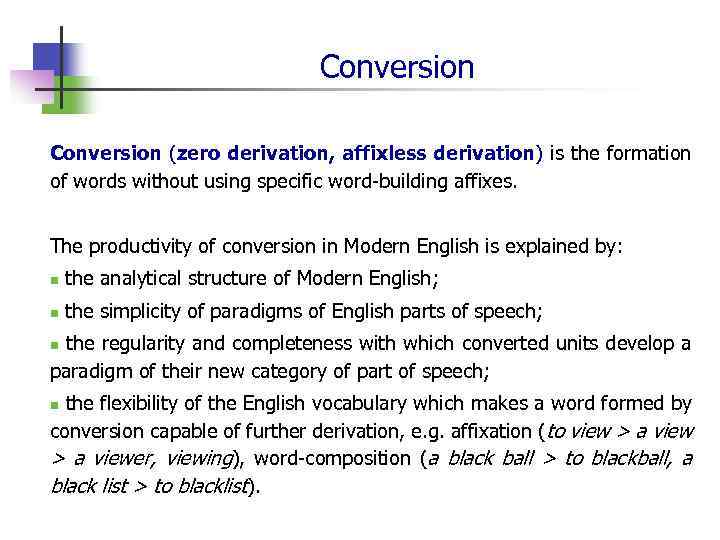

Conversion (zero derivation, affixless derivation) is the formation of words without using specific word-building affixes. The productivity of conversion in Modern English is explained by: n the analytical structure of Modern English; n the simplicity of paradigms of English parts of speech; the regularity and completeness with which converted units develop a paradigm of their new category of part of speech; n the flexibility of the English vocabulary which makes a word formed by conversion capable of further derivation, e. g. affixation (to view > a viewer, viewing), word-composition (a black ball > to blackball, a black list > to blacklist). n

Conversion (zero derivation, affixless derivation) is the formation of words without using specific word-building affixes. The productivity of conversion in Modern English is explained by: n the analytical structure of Modern English; n the simplicity of paradigms of English parts of speech; the regularity and completeness with which converted units develop a paradigm of their new category of part of speech; n the flexibility of the English vocabulary which makes a word formed by conversion capable of further derivation, e. g. affixation (to view > a viewer, viewing), word-composition (a black ball > to blackball, a black list > to blacklist). n

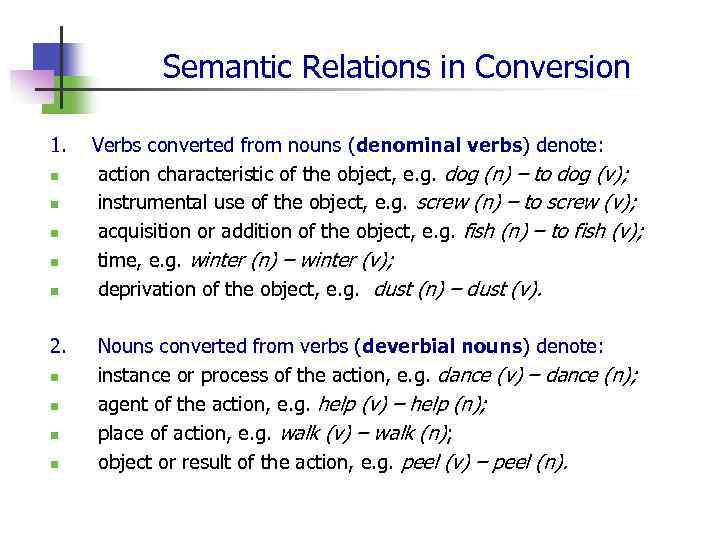

Semantic Relations in Conversion 1. Verbs converted from nouns (denominal verbs) denote: n action characteristic of the object, e. g. dog (n) – to dog (v); n instrumental use of the object, e. g. screw (n) – to screw (v); n acquisition or addition of the object, e. g. fish (n) – to fish (v); n time, e. g. winter (n) – winter (v); n deprivation of the object, e. g. dust (n) – dust (v). 2. Nouns converted from verbs (deverbial nouns) denote: n instance or process of the action, e. g. dance (v) – dance (n); n agent of the action, e. g. help (v) – help (n); n place of action, e. g. walk (v) – walk (n); n object or result of the action, e. g. peel (v) – peel (n).

Semantic Relations in Conversion 1. Verbs converted from nouns (denominal verbs) denote: n action characteristic of the object, e. g. dog (n) – to dog (v); n instrumental use of the object, e. g. screw (n) – to screw (v); n acquisition or addition of the object, e. g. fish (n) – to fish (v); n time, e. g. winter (n) – winter (v); n deprivation of the object, e. g. dust (n) – dust (v). 2. Nouns converted from verbs (deverbial nouns) denote: n instance or process of the action, e. g. dance (v) – dance (n); n agent of the action, e. g. help (v) – help (n); n place of action, e. g. walk (v) – walk (n); n object or result of the action, e. g. peel (v) – peel (n).

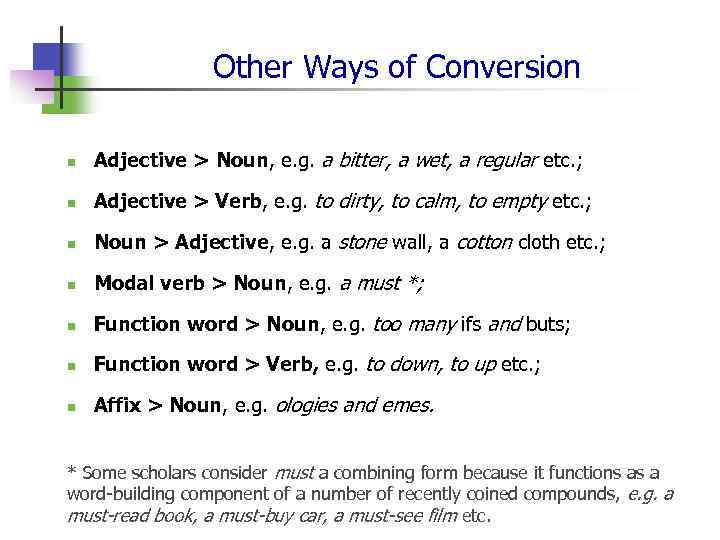

Other Ways of Conversion n Adjective > Noun, e. g. a bitter, a wet, a regular etc. ; n Adjective > Verb, e. g. to dirty, to calm, to empty etc. ; n Noun > Adjective, e. g. a stone wall, a cotton cloth etc. ; n Modal verb > Noun, e. g. a must *; n Function word > Noun, e. g. too many ifs and buts; n Function word > Verb, e. g. to down, to up etc. ; n Affix > Noun, e. g. ologies and emes. * Some scholars consider must a combining form because it functions as a word-building component of a number of recently coined compounds, e. g. a must-read book, a must-buy car, a must-see film etc.

Other Ways of Conversion n Adjective > Noun, e. g. a bitter, a wet, a regular etc. ; n Adjective > Verb, e. g. to dirty, to calm, to empty etc. ; n Noun > Adjective, e. g. a stone wall, a cotton cloth etc. ; n Modal verb > Noun, e. g. a must *; n Function word > Noun, e. g. too many ifs and buts; n Function word > Verb, e. g. to down, to up etc. ; n Affix > Noun, e. g. ologies and emes. * Some scholars consider must a combining form because it functions as a word-building component of a number of recently coined compounds, e. g. a must-read book, a must-buy car, a must-see film etc.

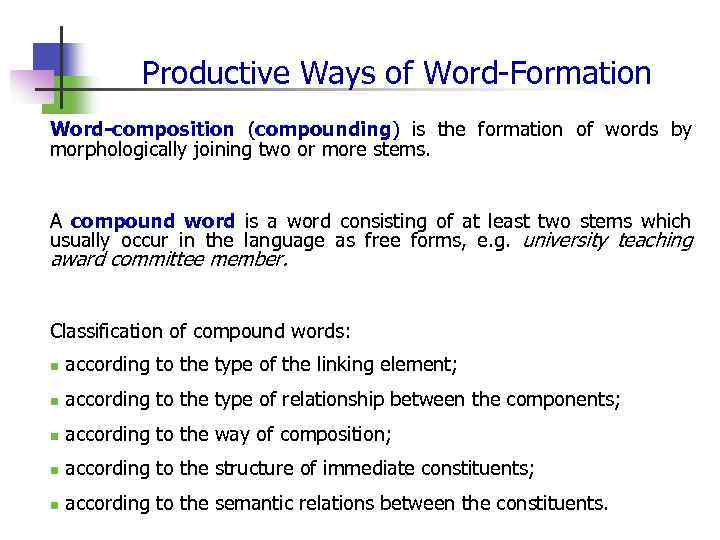

Productive Ways of Word-Formation Word-composition (compounding) is the formation of words by morphologically joining two or more stems. A compound word is a word consisting of at least two stems which usually occur in the language as free forms, e. g. university teaching award committee member. Classification of compound words: n according to the type of the linking element; n according to the type of relationship between the components; n according to the way of composition; n according to the structure of immediate constituents; n according to the semantic relations between the constituents.

Productive Ways of Word-Formation Word-composition (compounding) is the formation of words by morphologically joining two or more stems. A compound word is a word consisting of at least two stems which usually occur in the language as free forms, e. g. university teaching award committee member. Classification of compound words: n according to the type of the linking element; n according to the type of relationship between the components; n according to the way of composition; n according to the structure of immediate constituents; n according to the semantic relations between the constituents.

Classifications of Compounds According to the type of relationship between the components: n in coordinative (copulative) compounds neither of the components dominates the other, e. g. fifty-fifty, whisky-and-soda, driver-conductor; n in subordinative (determinative) compounds the components are neither structurally nor semantically equal in importance but are based on the domination of one component over the other, e. g. coffeepot, Oxford-educated, to headhunt, blue-eyed, red-haired etc. According to the way of composition: n compound proper is a compound formed after a composition pattern, i. e. by joining together the stems of words already available in the language, with or without the help of special linking elements, e. g. seasick, looking-glass, helicopter-rescued, handicraft; n derivational compound is a compound which is formed by two simultaneous processes of composition and derivation; in a derivational compound the structural integrity of two free stems is ensured by a suffix referring to the combination as a whole, e. g. long-legged, many-sided, old-timer, left-hander.

Classifications of Compounds According to the type of relationship between the components: n in coordinative (copulative) compounds neither of the components dominates the other, e. g. fifty-fifty, whisky-and-soda, driver-conductor; n in subordinative (determinative) compounds the components are neither structurally nor semantically equal in importance but are based on the domination of one component over the other, e. g. coffeepot, Oxford-educated, to headhunt, blue-eyed, red-haired etc. According to the way of composition: n compound proper is a compound formed after a composition pattern, i. e. by joining together the stems of words already available in the language, with or without the help of special linking elements, e. g. seasick, looking-glass, helicopter-rescued, handicraft; n derivational compound is a compound which is formed by two simultaneous processes of composition and derivation; in a derivational compound the structural integrity of two free stems is ensured by a suffix referring to the combination as a whole, e. g. long-legged, many-sided, old-timer, left-hander.

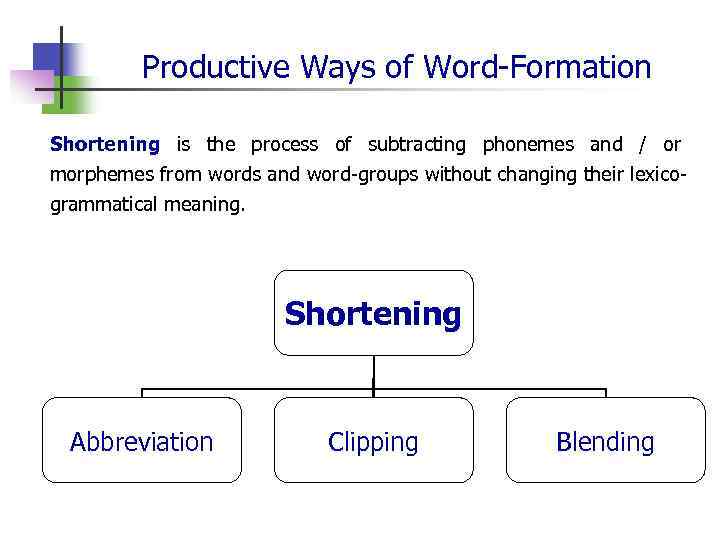

Productive Ways of Word-Formation Shortening is the process of subtracting phonemes and / or morphemes from words and word-groups without changing their lexicogrammatical meaning. Shortening Abbreviation Clipping Blending

Productive Ways of Word-Formation Shortening is the process of subtracting phonemes and / or morphemes from words and word-groups without changing their lexicogrammatical meaning. Shortening Abbreviation Clipping Blending

Types of Shortening Abbreviation is a process of shortening the result of which is a word made up of the initial letters or syllables of the components of a wordgroup or a compound word. Graphical abbreviation is the result of shortening of a word or a wordgroup only in written speech (for the economy of space and effort in writing), while orally the corresponding full form is used: n days of the week and months, e. g. Sun. , Tue. , Feb. , Oct. , Dec. ; n states in the USA, e. g. Alas. , CA, TX; n forms of address, e. g. Mr. , Mrs. , Dr. ; n scientific degrees, e. g. BA, BSc. , MA, MSc. , MBA, Ph. D. ; n military ranks, e. g. Col. ; n units of measurement, e. g. sec. , ft, km. n Latin abbreviations, e. g. p. a. , i. e. , ibid. , a. m. , cp. , viz. n internet abbreviations, e. g. BTW, FYI, TIA, AFAIK, TWIMC, MWA.

Types of Shortening Abbreviation is a process of shortening the result of which is a word made up of the initial letters or syllables of the components of a wordgroup or a compound word. Graphical abbreviation is the result of shortening of a word or a wordgroup only in written speech (for the economy of space and effort in writing), while orally the corresponding full form is used: n days of the week and months, e. g. Sun. , Tue. , Feb. , Oct. , Dec. ; n states in the USA, e. g. Alas. , CA, TX; n forms of address, e. g. Mr. , Mrs. , Dr. ; n scientific degrees, e. g. BA, BSc. , MA, MSc. , MBA, Ph. D. ; n military ranks, e. g. Col. ; n units of measurement, e. g. sec. , ft, km. n Latin abbreviations, e. g. p. a. , i. e. , ibid. , a. m. , cp. , viz. n internet abbreviations, e. g. BTW, FYI, TIA, AFAIK, TWIMC, MWA.

Types of Shortening Lexical abbreviation is the result of shortening of a word or a wordgroup both in written and oral speech. alphabetical abbreviation (initialism) is a shortening which is read as a succession of the alphabetical readings of the constituent letters, e. g. BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation), MTV (Music Television), EU (European Union), MP (Member of Parliament), WHO (World Health Organisation), AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome), GMO (Genetically Modified Organisms) etc. ; n acronymic abbreviation (acronym) is a shortening which is read as a succession of the sounds denoted by the constituent letters, i. e. as if they were an ordinary word, e. g. UNESCO (United Nations Scientific, and Cultural Organisation), NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation), UNICEF (United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund) etc. ; n

Types of Shortening Lexical abbreviation is the result of shortening of a word or a wordgroup both in written and oral speech. alphabetical abbreviation (initialism) is a shortening which is read as a succession of the alphabetical readings of the constituent letters, e. g. BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation), MTV (Music Television), EU (European Union), MP (Member of Parliament), WHO (World Health Organisation), AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome), GMO (Genetically Modified Organisms) etc. ; n acronymic abbreviation (acronym) is a shortening which is read as a succession of the sounds denoted by the constituent letters, i. e. as if they were an ordinary word, e. g. UNESCO (United Nations Scientific, and Cultural Organisation), NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation), UNICEF (United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund) etc. ; n

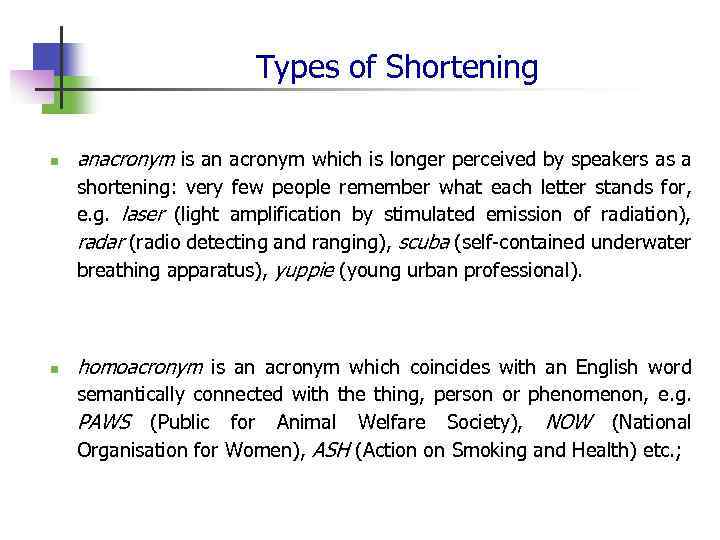

Types of Shortening n anacronym is an acronym which is longer perceived by speakers as a shortening: very few people remember what each letter stands for, e. g. laser (light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation), radar (radio detecting and ranging), scuba (self-contained underwater breathing apparatus), yuppie (young urban professional). n homoacronym is an acronym which coincides with an English word semantically connected with the thing, person or phenomenon, e. g. PAWS (Public for Animal Welfare Society), NOW (National Organisation for Women), ASH (Action on Smoking and Health) etc. ;

Types of Shortening n anacronym is an acronym which is longer perceived by speakers as a shortening: very few people remember what each letter stands for, e. g. laser (light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation), radar (radio detecting and ranging), scuba (self-contained underwater breathing apparatus), yuppie (young urban professional). n homoacronym is an acronym which coincides with an English word semantically connected with the thing, person or phenomenon, e. g. PAWS (Public for Animal Welfare Society), NOW (National Organisation for Women), ASH (Action on Smoking and Health) etc. ;

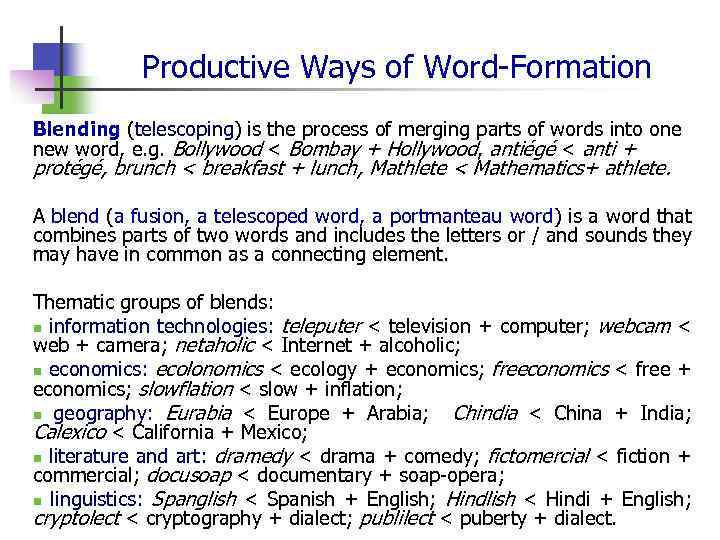

Productive Ways of Word-Formation Blending (telescoping) is the process of merging parts of words into one new word, e. g. Bollywood < Bombay + Hollywood, antiégé < anti + protégé, brunch < breakfast + lunch, Mathlete < Mathematics+ athlete. A blend (a fusion, a telescoped word, a portmanteau word) is a word that combines parts of two words and includes the letters or / and sounds they may have in common as a connecting element. Thematic groups of blends: n information technologies: teleputer < television + computer; webcam < web + camera; netaholic < Internet + alcoholic; n economics: ecolonomics < ecology + economics; freeconomics < free + economics; slowflation < slow + inflation; n geography: Eurabia < Europe + Arabia; Chindia < China + India; Calexico < California + Mexico; n literature and art: dramedy < drama + comedy; fictomercial < fiction + commercial; docusoap < documentary + soap-opera; n linguistics: Spanglish < Spanish + English; Hindlish < Hindi + English; cryptolect < cryptography + dialect; publilect < puberty + dialect.

Productive Ways of Word-Formation Blending (telescoping) is the process of merging parts of words into one new word, e. g. Bollywood < Bombay + Hollywood, antiégé < anti + protégé, brunch < breakfast + lunch, Mathlete < Mathematics+ athlete. A blend (a fusion, a telescoped word, a portmanteau word) is a word that combines parts of two words and includes the letters or / and sounds they may have in common as a connecting element. Thematic groups of blends: n information technologies: teleputer < television + computer; webcam < web + camera; netaholic < Internet + alcoholic; n economics: ecolonomics < ecology + economics; freeconomics < free + economics; slowflation < slow + inflation; n geography: Eurabia < Europe + Arabia; Chindia < China + India; Calexico < California + Mexico; n literature and art: dramedy < drama + comedy; fictomercial < fiction + commercial; docusoap < documentary + soap-opera; n linguistics: Spanglish < Spanish + English; Hindlish < Hindi + English; cryptolect < cryptography + dialect; publilect < puberty + dialect.

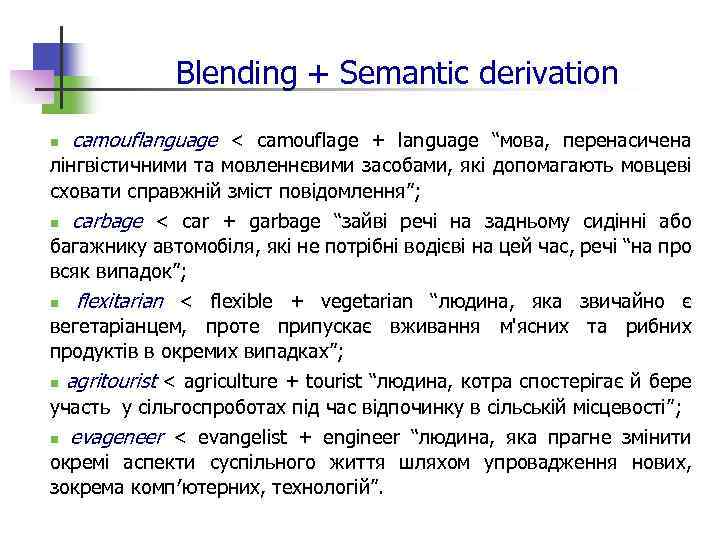

Blending + Semantic derivation n camouflanguage < camouflage + language “мова, перенасичена лінгвістичними та мовленнєвими засобами, які допомагають мовцеві сховати справжній зміст повідомлення”; n carbage < car + garbage “зайві речі на задньому сидінні або багажнику автомобіля, які не потрібні водієві на цей час, речі “на про всяк випадок”; n flexitarian < flexible + vegetarian “людина, яка звичайно є вегетаріанцем, проте припускає вживання м'ясних та рибних продуктів в окремих випадках”; n agritourist < agriculture + tourist “людина, котра спостерігає й бере участь у сільгоспроботах під час відпочинку в сільській місцевості”; n evageneer < evangelist + engineer “людина, яка прагне змінити окремі аспекти суспільного життя шляхом упровадження нових, зокрема комп′ютерних, технологій”.

Blending + Semantic derivation n camouflanguage < camouflage + language “мова, перенасичена лінгвістичними та мовленнєвими засобами, які допомагають мовцеві сховати справжній зміст повідомлення”; n carbage < car + garbage “зайві речі на задньому сидінні або багажнику автомобіля, які не потрібні водієві на цей час, речі “на про всяк випадок”; n flexitarian < flexible + vegetarian “людина, яка звичайно є вегетаріанцем, проте припускає вживання м'ясних та рибних продуктів в окремих випадках”; n agritourist < agriculture + tourist “людина, котра спостерігає й бере участь у сільгоспроботах під час відпочинку в сільській місцевості”; n evageneer < evangelist + engineer “людина, яка прагне змінити окремі аспекти суспільного життя шляхом упровадження нових, зокрема комп′ютерних, технологій”.

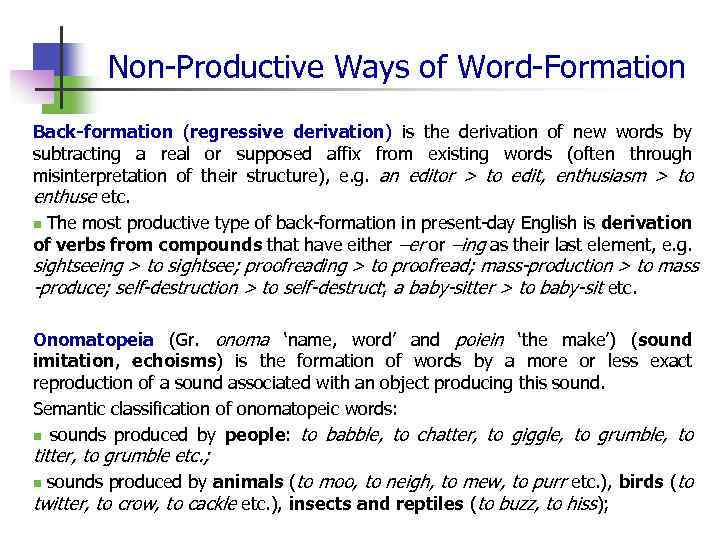

Non-Productive Ways of Word-Formation Back-formation (regressive derivation) is the derivation of new words by subtracting a real or supposed affix from existing words (often through misinterpretation of their structure), e. g. an editor > to edit, enthusiasm > to enthuse etc. n The most productive type of back-formation in present-day English is derivation of verbs from compounds that have either –er or –ing as their last element, e. g. sightseeing > to sightsee; proofreading > to proofread; mass-production > to mass -produce; self-destruction > to self-destruct; a baby-sitter > to baby-sit etc. Onomatopeia (Gr. onoma ‘name, word’ and poiein ‘the make’) (sound imitation, echoisms) is the formation of words by a more or less exact reproduction of a sound associated with an object producing this sound. Semantic classification of onomatopeic words: n sounds produced by people: to babble, to chatter, to giggle, to grumble, to titter, to grumble etc. ; sounds produced by animals (to moo, to neigh, to mew, to purr etc. ), birds (to twitter, to crow, to cackle etc. ), insects and reptiles (to buzz, to hiss); n

Non-Productive Ways of Word-Formation Back-formation (regressive derivation) is the derivation of new words by subtracting a real or supposed affix from existing words (often through misinterpretation of their structure), e. g. an editor > to edit, enthusiasm > to enthuse etc. n The most productive type of back-formation in present-day English is derivation of verbs from compounds that have either –er or –ing as their last element, e. g. sightseeing > to sightsee; proofreading > to proofread; mass-production > to mass -produce; self-destruction > to self-destruct; a baby-sitter > to baby-sit etc. Onomatopeia (Gr. onoma ‘name, word’ and poiein ‘the make’) (sound imitation, echoisms) is the formation of words by a more or less exact reproduction of a sound associated with an object producing this sound. Semantic classification of onomatopeic words: n sounds produced by people: to babble, to chatter, to giggle, to grumble, to titter, to grumble etc. ; sounds produced by animals (to moo, to neigh, to mew, to purr etc. ), birds (to twitter, to crow, to cackle etc. ), insects and reptiles (to buzz, to hiss); n

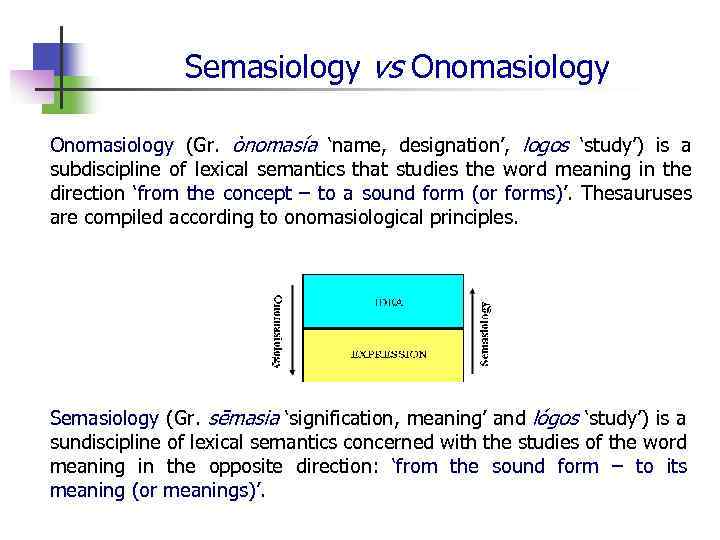

Semasiology vs Onomasiology (Gr. ònomasía ‘name, designation’, logos ‘study’) is a subdiscipline of lexical semantics that studies the word meaning in the direction ‘from the concept – to a sound form (or forms)’. Thesauruses are compiled according to onomasiological principles. Semasiology (Gr. sēmasia ‘signification, meaning’ and lógos ‘study’) is a sundiscipline of lexical semantics concerned with the studies of the word meaning in the opposite direction: ‘from the sound form – to its meaning (or meanings)’.

Semasiology vs Onomasiology (Gr. ònomasía ‘name, designation’, logos ‘study’) is a subdiscipline of lexical semantics that studies the word meaning in the direction ‘from the concept – to a sound form (or forms)’. Thesauruses are compiled according to onomasiological principles. Semasiology (Gr. sēmasia ‘signification, meaning’ and lógos ‘study’) is a sundiscipline of lexical semantics concerned with the studies of the word meaning in the opposite direction: ‘from the sound form – to its meaning (or meanings)’.

Types of Word Meaning Word-meaning is not homogeneous but is made up of various components the combination and the interrelation of which determine to a great extent the inner facet of the word. Grammatical meaning is the meaning which unites words into big groups such as parts of speech or lexico-grammatical classes. It is recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of different words, e. g. stones, apples, kids, thoughts have the grammatical meaning of plurality. Lexical meaning is the meaning proper to the word as a linguistic unit; it is recurrent in all the forms of this word and in all the possible distributions of these forms, e. g. the word-forms write, writes, wrote, writing, written have different grammatical meanings of tense, person, aspect, but the same lexical meaning ‘to make letters or other symbols on a surface, especially with a pen or pencil’.

Types of Word Meaning Word-meaning is not homogeneous but is made up of various components the combination and the interrelation of which determine to a great extent the inner facet of the word. Grammatical meaning is the meaning which unites words into big groups such as parts of speech or lexico-grammatical classes. It is recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of different words, e. g. stones, apples, kids, thoughts have the grammatical meaning of plurality. Lexical meaning is the meaning proper to the word as a linguistic unit; it is recurrent in all the forms of this word and in all the possible distributions of these forms, e. g. the word-forms write, writes, wrote, writing, written have different grammatical meanings of tense, person, aspect, but the same lexical meaning ‘to make letters or other symbols on a surface, especially with a pen or pencil’.

Components of Lexical Meaning Lexical meaning is not homogenous either and may be analysed as including denotative and connotative components. Denotative (denotational) (Lat. denotatum ‘signified’) component is the conceptual content of the word fulfilling its significative and communicative functions; our experience is conceptualised and classified in it. Connotative (connotational) (Lat. connoto ‘additional meaning’) component conveys the speaker’s attitude to the social circumstances and the appropriate functional style, one’s approval or disapproval of the object spoken of, the speaker’s emotions, the degree of intensity; unlike denotations or significations, connotations are optional.

Components of Lexical Meaning Lexical meaning is not homogenous either and may be analysed as including denotative and connotative components. Denotative (denotational) (Lat. denotatum ‘signified’) component is the conceptual content of the word fulfilling its significative and communicative functions; our experience is conceptualised and classified in it. Connotative (connotational) (Lat. connoto ‘additional meaning’) component conveys the speaker’s attitude to the social circumstances and the appropriate functional style, one’s approval or disapproval of the object spoken of, the speaker’s emotions, the degree of intensity; unlike denotations or significations, connotations are optional.

Types of Connotations Stylistic connotation is concerned with the situation in which the word is uttered, the social circumstances (formal, familiar), the social relationships between the communicants (polite, rough etc. ), the type and purpose of communication, e. g. father (stylistically neutr. ), dad (colloquial), parent (bookish). Emotional connotation is acquired by the word as a result of its frequent use in contexts corresponding to emotional situations or because the referent conceptualised in the denotative meaning is associated with certain emotions, e. g. mother (emotionally neutr. ), mummy (emotionally charged); bright (emotionally neutr. ), garish (implies negative emotions). Evaluative connotation expresses approval or disapproval, e. g. modern is often used appreciatively, newfangled expresses disapproval. Intensifying connotation expresses degree of intensity, e. g. the words magnificent, gorgeous, splendid, superb are used colloquially as terms of exaggeration.

Types of Connotations Stylistic connotation is concerned with the situation in which the word is uttered, the social circumstances (formal, familiar), the social relationships between the communicants (polite, rough etc. ), the type and purpose of communication, e. g. father (stylistically neutr. ), dad (colloquial), parent (bookish). Emotional connotation is acquired by the word as a result of its frequent use in contexts corresponding to emotional situations or because the referent conceptualised in the denotative meaning is associated with certain emotions, e. g. mother (emotionally neutr. ), mummy (emotionally charged); bright (emotionally neutr. ), garish (implies negative emotions). Evaluative connotation expresses approval or disapproval, e. g. modern is often used appreciatively, newfangled expresses disapproval. Intensifying connotation expresses degree of intensity, e. g. the words magnificent, gorgeous, splendid, superb are used colloquially as terms of exaggeration.

Polysemy (Gr. πολυσημεία ‘multiple meaning’) is the ability of words to have more than one meaning. Polysemy is typical of the English vocabulary due to: n its monosyllabic character; n the predominance of root words. A monosemantic word is a word having only one meaning; these are mostly terms, e. g. : hydrogen, molecule. A polysemantic word is a word having more than one meaning; highly polysemous words can include dozens of meanings, e. g. to go – appr. 40 meanings), to get, to put, to take – appr. 30 meanings). The semantic structure of a word is an organised system comprising all meanings and shades of meanings that a particular sound complex can assume in different contexts together with emotional, stylistic and other connotations.

Polysemy (Gr. πολυσημεία ‘multiple meaning’) is the ability of words to have more than one meaning. Polysemy is typical of the English vocabulary due to: n its monosyllabic character; n the predominance of root words. A monosemantic word is a word having only one meaning; these are mostly terms, e. g. : hydrogen, molecule. A polysemantic word is a word having more than one meaning; highly polysemous words can include dozens of meanings, e. g. to go – appr. 40 meanings), to get, to put, to take – appr. 30 meanings). The semantic structure of a word is an organised system comprising all meanings and shades of meanings that a particular sound complex can assume in different contexts together with emotional, stylistic and other connotations.

Typology of Meaning n n n Direct meaning (primary meaning) is the meaning which characterises the referent without the help of a context, in isolation. Indirect meaning (figurative / secondary / derived meaning) is the meaning formed from the direct meaning according to the models of semantic derivation; it is realised only in definite contexts. Main meaning possesses the highest frequency at the present stage of vocabulary development. Etymological meaning is the earliest known meaning, e. g. urchin, n. ‘a mischievous or naughty child, esp. a boy’ < ‘a hedgehog’. Archaic meaning is the meaning superseded at present by a newer one, but still remaining in certain collocations, e. g. brave ‘fine, excellent, admirable’ as in a brave new world ‘a new era resulting from revolutionary changes, reforms etc. in society’. Obsolete meaning is the meaning which went out of use, e. g. to taste ‘to examine by touch, to feel; to test or try’.

Typology of Meaning n n n Direct meaning (primary meaning) is the meaning which characterises the referent without the help of a context, in isolation. Indirect meaning (figurative / secondary / derived meaning) is the meaning formed from the direct meaning according to the models of semantic derivation; it is realised only in definite contexts. Main meaning possesses the highest frequency at the present stage of vocabulary development. Etymological meaning is the earliest known meaning, e. g. urchin, n. ‘a mischievous or naughty child, esp. a boy’ < ‘a hedgehog’. Archaic meaning is the meaning superseded at present by a newer one, but still remaining in certain collocations, e. g. brave ‘fine, excellent, admirable’ as in a brave new world ‘a new era resulting from revolutionary changes, reforms etc. in society’. Obsolete meaning is the meaning which went out of use, e. g. to taste ‘to examine by touch, to feel; to test or try’.

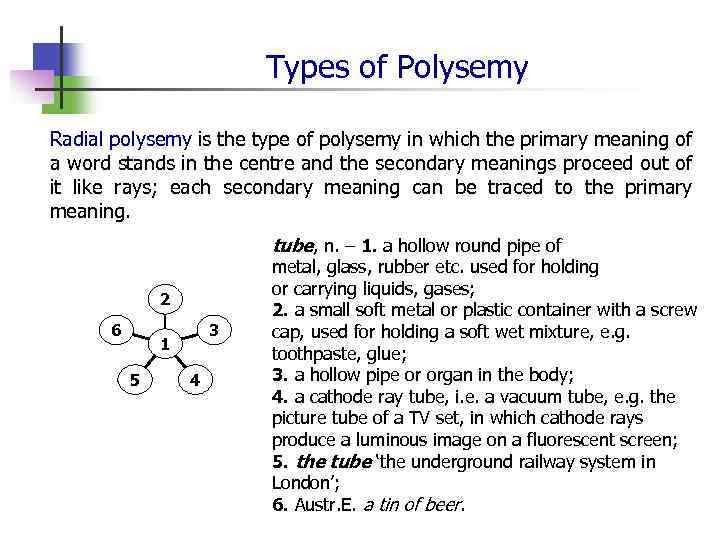

Types of Polysemy Radial polysemy is the type of polysemy in which the primary meaning of a word stands in the centre and the secondary meanings proceed out of it like rays; each secondary meaning can be traced to the primary meaning. tube, n. – 1. a hollow round pipe of 2 6 3 1 5 4 metal, glass, rubber etc. used for holding or carrying liquids, gases; 2. a small soft metal or plastic container with a screw cap, used for holding a soft wet mixture, e. g. toothpaste, glue; 3. a hollow pipe or organ in the body; 4. a cathode ray tube, i. e. a vacuum tube, e. g. the picture tube of a TV set, in which cathode rays produce a luminous image on a fluorescent screen; 5. the tube ‘the underground railway system in London’; 6. Austr. E. a tin of beer.

Types of Polysemy Radial polysemy is the type of polysemy in which the primary meaning of a word stands in the centre and the secondary meanings proceed out of it like rays; each secondary meaning can be traced to the primary meaning. tube, n. – 1. a hollow round pipe of 2 6 3 1 5 4 metal, glass, rubber etc. used for holding or carrying liquids, gases; 2. a small soft metal or plastic container with a screw cap, used for holding a soft wet mixture, e. g. toothpaste, glue; 3. a hollow pipe or organ in the body; 4. a cathode ray tube, i. e. a vacuum tube, e. g. the picture tube of a TV set, in which cathode rays produce a luminous image on a fluorescent screen; 5. the tube ‘the underground railway system in London’; 6. Austr. E. a tin of beer.

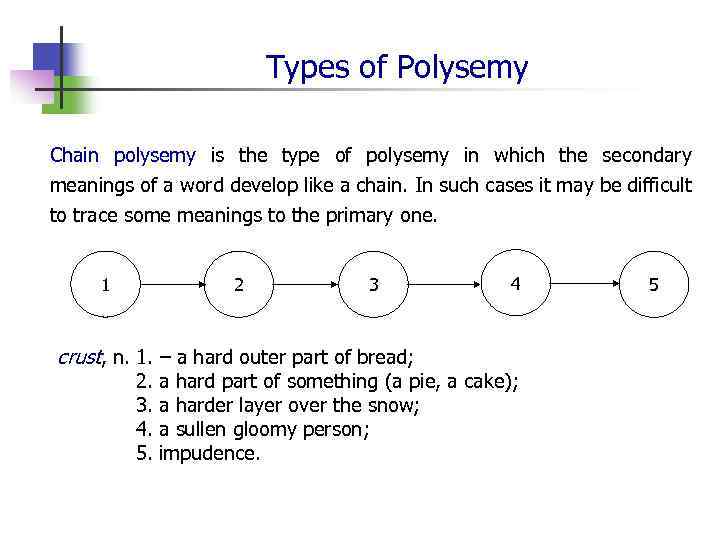

Types of Polysemy Chain polysemy is the type of polysemy in which the secondary meanings of a word develop like a chain. In such cases it may be difficult to trace some meanings to the primary one. 1 2 3 crust, n. 1. – a hard outer part of bread; 4 2. a hard part of something (a pie, a cake); 3. a harder layer over the snow; 4. a sullen gloomy person; 5. impudence. 5

Types of Polysemy Chain polysemy is the type of polysemy in which the secondary meanings of a word develop like a chain. In such cases it may be difficult to trace some meanings to the primary one. 1 2 3 crust, n. 1. – a hard outer part of bread; 4 2. a hard part of something (a pie, a cake); 3. a harder layer over the snow; 4. a sullen gloomy person; 5. impudence. 5

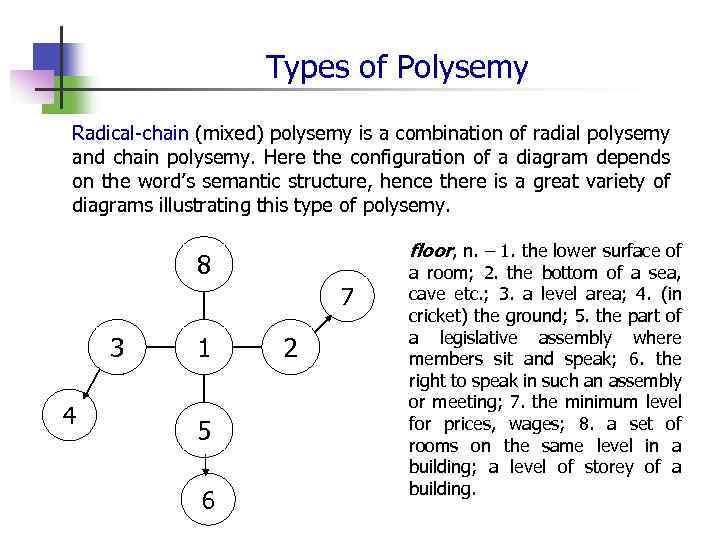

Types of Polysemy Radical-chain (mixed) polysemy is a combination of radial polysemy and chain polysemy. Here the configuration of a diagram depends on the word’s semantic structure, hence there is a great variety of diagrams illustrating this type of polysemy. floor, n. – 1. the lower surface of 8 7 3 4 1 5 6 2 a room; 2. the bottom of a sea, cave etc. ; 3. a level area; 4. (in cricket) the ground; 5. the part of a legislative assembly where members sit and speak; 6. the right to speak in such an assembly or meeting; 7. the minimum level for prices, wages; 8. a set of rooms on the same level in a building; a level of storey of a building.

Types of Polysemy Radical-chain (mixed) polysemy is a combination of radial polysemy and chain polysemy. Here the configuration of a diagram depends on the word’s semantic structure, hence there is a great variety of diagrams illustrating this type of polysemy. floor, n. – 1. the lower surface of 8 7 3 4 1 5 6 2 a room; 2. the bottom of a sea, cave etc. ; 3. a level area; 4. (in cricket) the ground; 5. the part of a legislative assembly where members sit and speak; 6. the right to speak in such an assembly or meeting; 7. the minimum level for prices, wages; 8. a set of rooms on the same level in a building; a level of storey of a building.

Synonymy Synonyms (Gr. syn ‘with’, ónyma ‘name’) are two or more words belonging to the same part of speech and possessing a common denotative semantic component, interchangeable at least in some contexts without any considerable alteration in sense, but differing in morphemic composition, phonemic shape, shades of meaning, connotations, style, valency and idiomatic use. The synonymic dominant is the general term of its kind potentially containing the specific features rendered by all the other members of the group. It is characterised by: high frequency value; broad combinability; broad general meaning; lack of connotations; stylistic neutrality; it may substitute for other synonyms at least in some contexts; it is often used to define other synonyms in dictionary definitions.

Synonymy Synonyms (Gr. syn ‘with’, ónyma ‘name’) are two or more words belonging to the same part of speech and possessing a common denotative semantic component, interchangeable at least in some contexts without any considerable alteration in sense, but differing in morphemic composition, phonemic shape, shades of meaning, connotations, style, valency and idiomatic use. The synonymic dominant is the general term of its kind potentially containing the specific features rendered by all the other members of the group. It is characterised by: high frequency value; broad combinability; broad general meaning; lack of connotations; stylistic neutrality; it may substitute for other synonyms at least in some contexts; it is often used to define other synonyms in dictionary definitions.

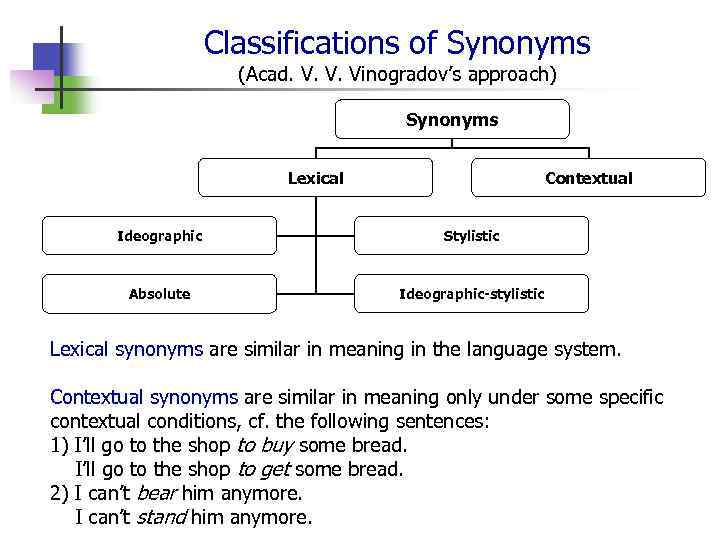

Classifications of Synonyms (Acad. V. V. Vinogradov’s approach) Synonyms Lexical Contextual Ideographic Stylistic Absolute Ideographic-stylistic Lexical synonyms are similar in meaning in the language system. Contextual synonyms are similar in meaning only under some specific contextual conditions, cf. the following sentences: 1) I’ll go to the shop to buy some bread. I’ll go to the shop to get some bread. 2) I can’t bear him anymore. I can’t stand him anymore.

Classifications of Synonyms (Acad. V. V. Vinogradov’s approach) Synonyms Lexical Contextual Ideographic Stylistic Absolute Ideographic-stylistic Lexical synonyms are similar in meaning in the language system. Contextual synonyms are similar in meaning only under some specific contextual conditions, cf. the following sentences: 1) I’ll go to the shop to buy some bread. I’ll go to the shop to get some bread. 2) I can’t bear him anymore. I can’t stand him anymore.

Lexical Synonyms Absolute synonyms coincide in all their shades of meaning and in all their stylistic characteristics, e. g. word-building – word-formation; Ideographic synonyms convey the same concept but differ in shades of meaning, i. e. in their denotative component, e. g. : n interesting – (exciting), (makes you want to know more sth); n fascinating – (exciting), (makes you want to know more sth), [extremely]; n intriguing – (exciting), (makes you want to know more sth), [there is sth you find difficult to understand or explain]; n absorbing – (exciting), (makes you want to know more sth), [holds your attention for a long time]; Stylistic synonyms differ in their stylistic characteristics, i. e. in their connotative component, e. g. head (neutral) – attic (stylistic). Ideographic-stylistic synonyms differ in shades of meaning and belong to different styles, e. g. to see ‘to have or use the powers of sight and understanding’ – to behold (elevated, archaic) ‘to look at that which is seen’.

Lexical Synonyms Absolute synonyms coincide in all their shades of meaning and in all their stylistic characteristics, e. g. word-building – word-formation; Ideographic synonyms convey the same concept but differ in shades of meaning, i. e. in their denotative component, e. g. : n interesting – (exciting), (makes you want to know more sth); n fascinating – (exciting), (makes you want to know more sth), [extremely]; n intriguing – (exciting), (makes you want to know more sth), [there is sth you find difficult to understand or explain]; n absorbing – (exciting), (makes you want to know more sth), [holds your attention for a long time]; Stylistic synonyms differ in their stylistic characteristics, i. e. in their connotative component, e. g. head (neutral) – attic (stylistic). Ideographic-stylistic synonyms differ in shades of meaning and belong to different styles, e. g. to see ‘to have or use the powers of sight and understanding’ – to behold (elevated, archaic) ‘to look at that which is seen’.

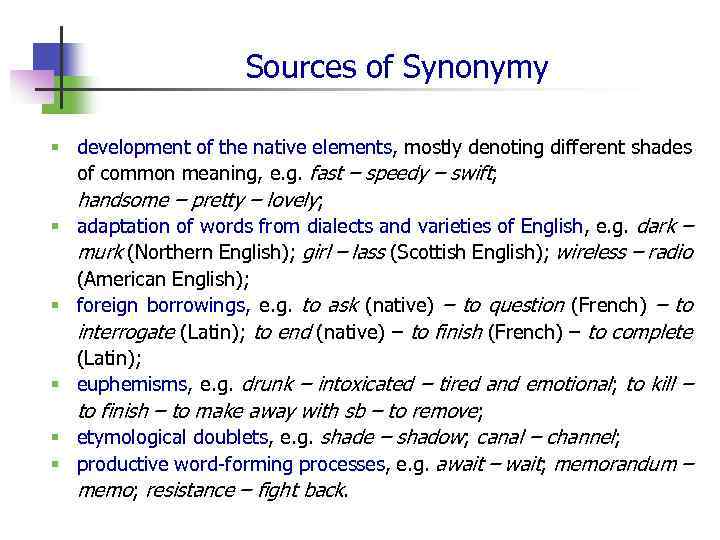

Sources of Synonymy § development of the native elements, mostly denoting different shades of common meaning, e. g. fast – speedy – swift; handsome – pretty – lovely; § adaptation of words from dialects and varieties of English, e. g. dark – murk (Northern English); girl – lass (Scottish English); wireless – radio (American English); § foreign borrowings, e. g. to ask (native) – to question (French) – to interrogate (Latin); to end (native) – to finish (French) – to complete (Latin); § euphemisms, e. g. drunk – intoxicated – tired and emotional; to kill – to finish – to make away with sb – to remove; § etymological doublets, e. g. shade – shadow; canal – channel; § productive word-forming processes, e. g. await – wait; memorandum – memo; resistance – fight back.

Sources of Synonymy § development of the native elements, mostly denoting different shades of common meaning, e. g. fast – speedy – swift; handsome – pretty – lovely; § adaptation of words from dialects and varieties of English, e. g. dark – murk (Northern English); girl – lass (Scottish English); wireless – radio (American English); § foreign borrowings, e. g. to ask (native) – to question (French) – to interrogate (Latin); to end (native) – to finish (French) – to complete (Latin); § euphemisms, e. g. drunk – intoxicated – tired and emotional; to kill – to finish – to make away with sb – to remove; § etymological doublets, e. g. shade – shadow; canal – channel; § productive word-forming processes, e. g. await – wait; memorandum – memo; resistance – fight back.

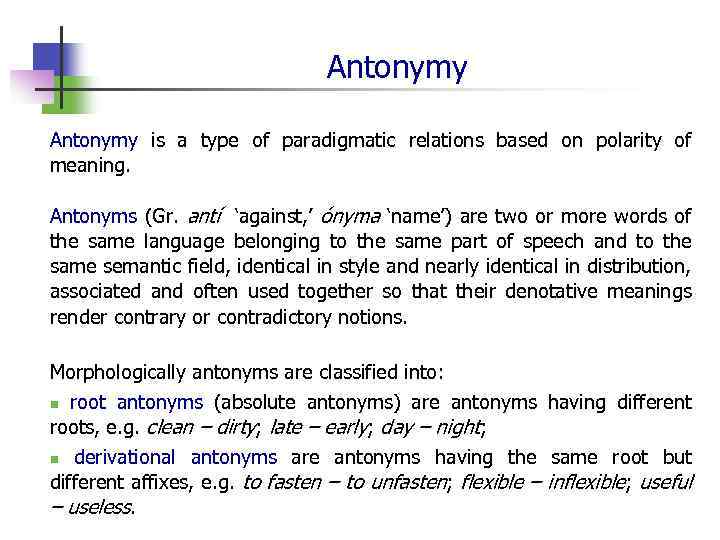

Antonymy is a type of paradigmatic relations based on polarity of meaning. Antonyms (Gr. antí ‘against, ’ ónyma ‘name’) are two or more words of the same language belonging to the same part of speech and to the same semantic field, identical in style and nearly identical in distribution, associated and often used together so that their denotative meanings render contrary or contradictory notions. Morphologically antonyms are classified into: root antonyms (absolute antonyms) are antonyms having different roots, e. g. clean – dirty; late – early; day – night; n derivational antonyms are antonyms having the same root but different affixes, e. g. to fasten – to unfasten; flexible – inflexible; useful – useless. n

Antonymy is a type of paradigmatic relations based on polarity of meaning. Antonyms (Gr. antí ‘against, ’ ónyma ‘name’) are two or more words of the same language belonging to the same part of speech and to the same semantic field, identical in style and nearly identical in distribution, associated and often used together so that their denotative meanings render contrary or contradictory notions. Morphologically antonyms are classified into: root antonyms (absolute antonyms) are antonyms having different roots, e. g. clean – dirty; late – early; day – night; n derivational antonyms are antonyms having the same root but different affixes, e. g. to fasten – to unfasten; flexible – inflexible; useful – useless. n

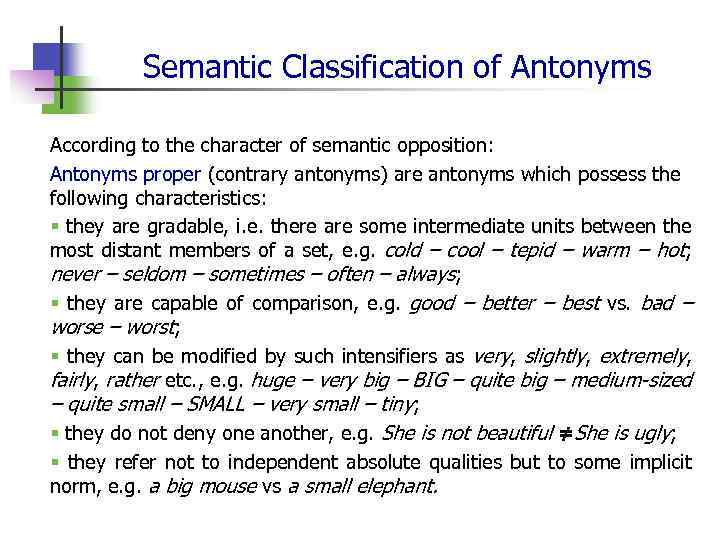

Semantic Classification of Antonyms According to the character of semantic opposition: Antonyms proper (contrary antonyms) are antonyms which possess the following characteristics: § they are gradable, i. e. there are some intermediate units between the most distant members of a set, e. g. cold – cool – tepid – warm – hot; never – seldom – sometimes – often – always; § they are capable of comparison, e. g. good – better – best vs. bad – worse – worst; § they can be modified by such intensifiers as very, slightly, extremely, fairly, rather etc. , e. g. huge – very big – BIG – quite big – medium-sized – quite small – SMALL – very small – tiny; § they do not deny one another, e. g. She is not beautiful ≠She is ugly; § they refer not to independent absolute qualities but to some implicit norm, e. g. a big mouse vs a small elephant.

Semantic Classification of Antonyms According to the character of semantic opposition: Antonyms proper (contrary antonyms) are antonyms which possess the following characteristics: § they are gradable, i. e. there are some intermediate units between the most distant members of a set, e. g. cold – cool – tepid – warm – hot; never – seldom – sometimes – often – always; § they are capable of comparison, e. g. good – better – best vs. bad – worse – worst; § they can be modified by such intensifiers as very, slightly, extremely, fairly, rather etc. , e. g. huge – very big – BIG – quite big – medium-sized – quite small – SMALL – very small – tiny; § they do not deny one another, e. g. She is not beautiful ≠She is ugly; § they refer not to independent absolute qualities but to some implicit norm, e. g. a big mouse vs a small elephant.

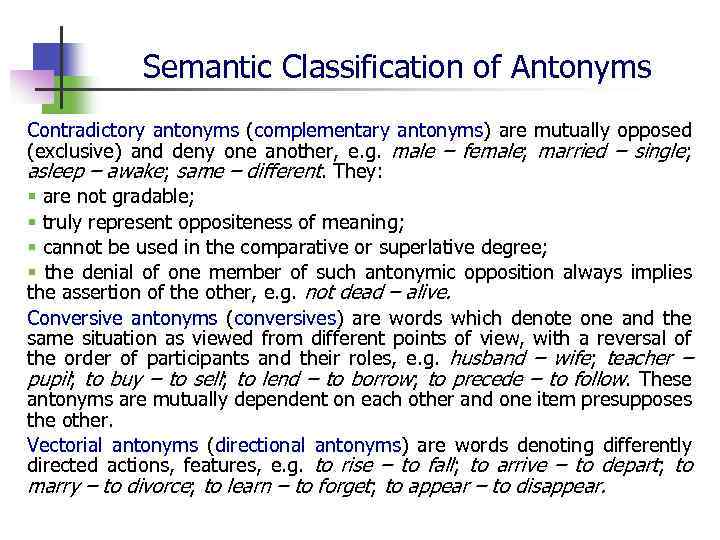

Semantic Classification of Antonyms Contradictory antonyms (complementary antonyms) are mutually opposed (exclusive) and deny one another, e. g. male – female; married – single; asleep – awake; same – different. They: § are not gradable; § truly represent oppositeness of meaning; § cannot be used in the comparative or superlative degree; § the denial of one member of such antonymic opposition always implies the assertion of the other, e. g. not dead – alive. Conversive antonyms (conversives) are words which denote one and the same situation as viewed from different points of view, with a reversal of the order of participants and their roles, e. g. husband – wife; teacher – pupil; to buy – to sell; to lend – to borrow; to precede – to follow. These antonyms are mutually dependent on each other and one item presupposes the other. Vectorial antonyms (directional antonyms) are words denoting differently directed actions, features, e. g. to rise – to fall; to arrive – to depart; to marry – to divorce; to learn – to forget; to appear – to disappear.

Semantic Classification of Antonyms Contradictory antonyms (complementary antonyms) are mutually opposed (exclusive) and deny one another, e. g. male – female; married – single; asleep – awake; same – different. They: § are not gradable; § truly represent oppositeness of meaning; § cannot be used in the comparative or superlative degree; § the denial of one member of such antonymic opposition always implies the assertion of the other, e. g. not dead – alive. Conversive antonyms (conversives) are words which denote one and the same situation as viewed from different points of view, with a reversal of the order of participants and their roles, e. g. husband – wife; teacher – pupil; to buy – to sell; to lend – to borrow; to precede – to follow. These antonyms are mutually dependent on each other and one item presupposes the other. Vectorial antonyms (directional antonyms) are words denoting differently directed actions, features, e. g. to rise – to fall; to arrive – to depart; to marry – to divorce; to learn – to forget; to appear – to disappear.

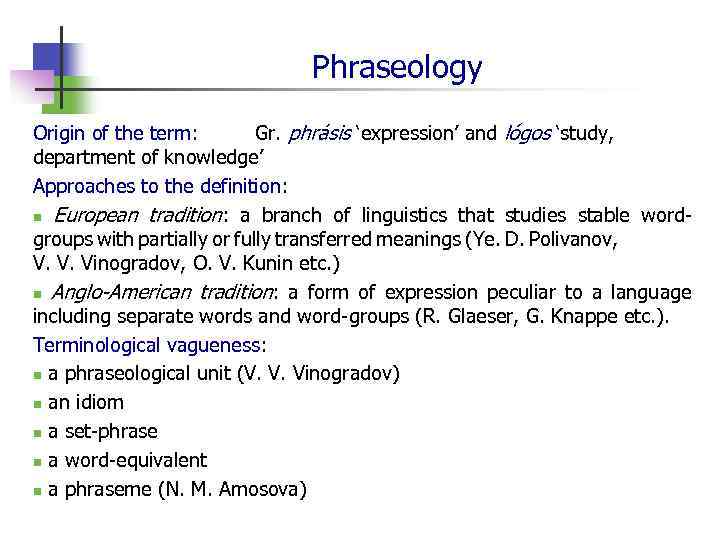

Phraseology Origin of the term: Gr. phrásis ‘expression’ and lógos ‘study, department of knowledge’ Approaches to the definition: n European tradition: a branch of linguistics that studies stable wordgroups with partially or fully transferred meanings (Ye. D. Polivanov, V. V. Vinogradov, O. V. Kunin etc. ) n Anglo-American tradition: a form of expression peculiar to a language including separate words and word-groups (R. Glaeser, G. Knappe etc. ). Terminological vagueness: n a phraseological unit (V. V. Vinogradov) n an idiom n a set-phrase n a word-equivalent n a phraseme (N. M. Amosova)

Phraseology Origin of the term: Gr. phrásis ‘expression’ and lógos ‘study, department of knowledge’ Approaches to the definition: n European tradition: a branch of linguistics that studies stable wordgroups with partially or fully transferred meanings (Ye. D. Polivanov, V. V. Vinogradov, O. V. Kunin etc. ) n Anglo-American tradition: a form of expression peculiar to a language including separate words and word-groups (R. Glaeser, G. Knappe etc. ). Terminological vagueness: n a phraseological unit (V. V. Vinogradov) n an idiom n a set-phrase n a word-equivalent n a phraseme (N. M. Amosova)

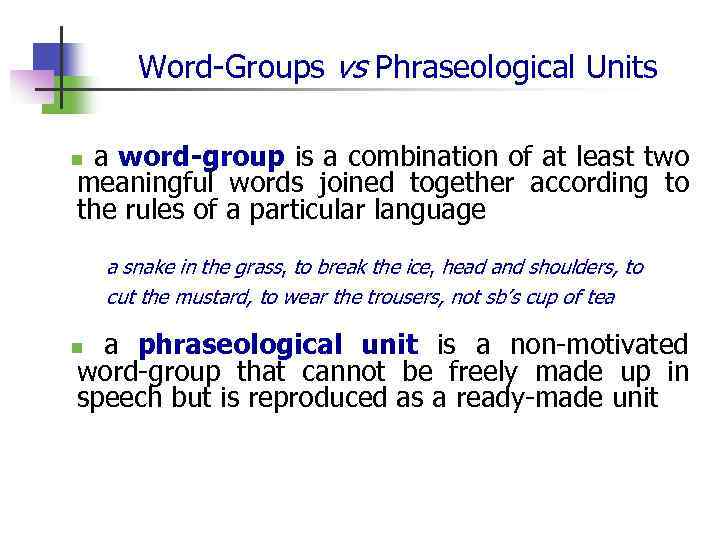

Word-Groups vs Phraseological Units a word-group is a combination of at least two meaningful words joined together according to the rules of a particular language n a snake in the grass, to break the ice, head and shoulders, to cut the mustard, to wear the trousers, not sb’s cup of tea a phraseological unit is a non-motivated word-group that cannot be freely made up in speech but is reproduced as a ready-made unit n

Word-Groups vs Phraseological Units a word-group is a combination of at least two meaningful words joined together according to the rules of a particular language n a snake in the grass, to break the ice, head and shoulders, to cut the mustard, to wear the trousers, not sb’s cup of tea a phraseological unit is a non-motivated word-group that cannot be freely made up in speech but is reproduced as a ready-made unit n

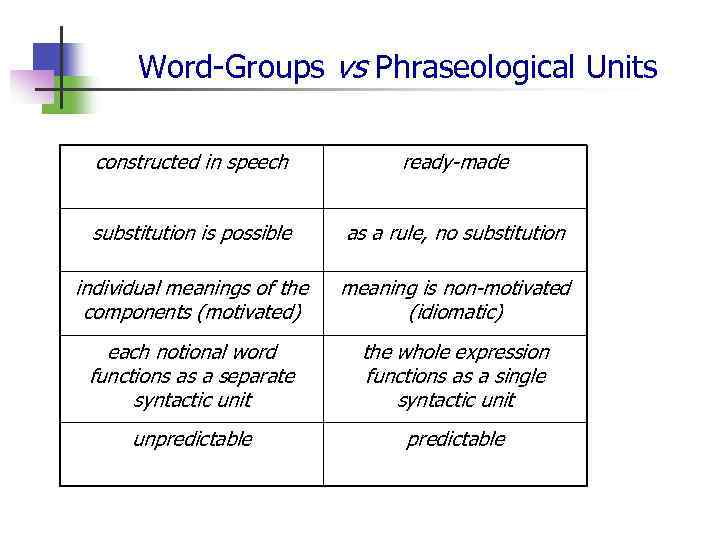

Word-Groups vs Phraseological Units constructed in speech ready-made substitution is possible as a rule, no substitution individual meanings of the components (motivated) meaning is non-motivated (idiomatic) each notional word functions as a separate syntactic unit the whole expression functions as a single syntactic unit unpredictable

Word-Groups vs Phraseological Units constructed in speech ready-made substitution is possible as a rule, no substitution individual meanings of the components (motivated) meaning is non-motivated (idiomatic) each notional word functions as a separate syntactic unit the whole expression functions as a single syntactic unit unpredictable

Main Features of Phraseological Units n n idiomaticity reproducibility n stability n predictability n inseparability

Main Features of Phraseological Units n n idiomaticity reproducibility n stability n predictability n inseparability

Thematic Classification Smith, Logan Pearsall (1865 -1946), an American-born essayist and critic, and a notable writer on historical semantics; English Idioms (1923), Words and Idioms (1925) Phraseological units are classified according to their source of origin, i. e. source referring to the particular sphere of human activity, natural phenomena, domestic and wild animals, etc. ; through time most of them develop metaphorical meaning; n Idioms related to the sea and the life of seamen: to be all at sea; to be in deep waters; to be in the same boat with sb; to sail through sth; to show one’s colours; to weather the storm; three sheets in the wind (sl) etc. n

Thematic Classification Smith, Logan Pearsall (1865 -1946), an American-born essayist and critic, and a notable writer on historical semantics; English Idioms (1923), Words and Idioms (1925) Phraseological units are classified according to their source of origin, i. e. source referring to the particular sphere of human activity, natural phenomena, domestic and wild animals, etc. ; through time most of them develop metaphorical meaning; n Idioms related to the sea and the life of seamen: to be all at sea; to be in deep waters; to be in the same boat with sb; to sail through sth; to show one’s colours; to weather the storm; three sheets in the wind (sl) etc. n

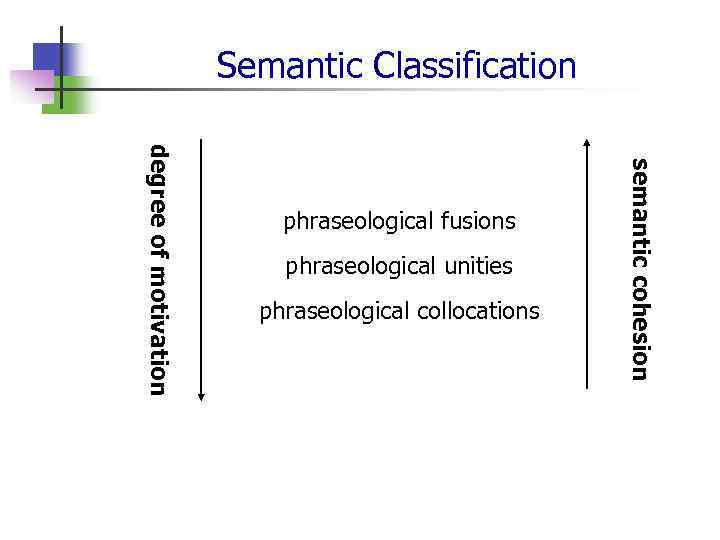

Semantic Classification n n The idea of the semantic classification of phraseological units was first advanced by the Swiss linguist Charles Bally. This research work was carried out by Acad. V. V. Vinogradov in the field of Russian phraseology. The underlying principle of the semantic classification is the degree of motivation (idiomaticity), i. e. the relationship existing between the meaning of the whole phraseological unit and the meaning of its components. The degree of motivation correlates with the semantic unity (cohesion) of the phraseological unit, i. e. the possibility of changing the form or order of the components and substituting the whole by a single word.

Semantic Classification n n The idea of the semantic classification of phraseological units was first advanced by the Swiss linguist Charles Bally. This research work was carried out by Acad. V. V. Vinogradov in the field of Russian phraseology. The underlying principle of the semantic classification is the degree of motivation (idiomaticity), i. e. the relationship existing between the meaning of the whole phraseological unit and the meaning of its components. The degree of motivation correlates with the semantic unity (cohesion) of the phraseological unit, i. e. the possibility of changing the form or order of the components and substituting the whole by a single word.

Semantic Classification phraseological unities phraseological collocations semantic cohesion degree of motivation phraseological fusions

Semantic Classification phraseological unities phraseological collocations semantic cohesion degree of motivation phraseological fusions

Semantic Classification n Phraseological combinations (collocations): clearly motivated; made up of words possessing specific lexical valency which accounts for a certain degree of stability in such word-groups; variability of member-words is strictly limited, e. g. to meet the demand, to make a mistake, to bear a grudge, to pay a compliment, to give a speech etc. n Phraseological unities: partially non-motivated, i. e. their meaning can usually be perceived through the metaphoric meaning of the whole unit, e. g. to lose one’s n head, a fish out of water, to show one’s teeth, to wash one’s dirty linen in public, to sit on the fence etc. n n Phraseological fusions: completely non-motivated, i. e. the meaning of the components has no connection, at least synchronically, with the meaning of the whole group; characterised by complete stability of the lexical components and the grammatical structure of the whole unit, e. g. once in a blue moon, to be on the carpet, under the rose etc.

Semantic Classification n Phraseological combinations (collocations): clearly motivated; made up of words possessing specific lexical valency which accounts for a certain degree of stability in such word-groups; variability of member-words is strictly limited, e. g. to meet the demand, to make a mistake, to bear a grudge, to pay a compliment, to give a speech etc. n Phraseological unities: partially non-motivated, i. e. their meaning can usually be perceived through the metaphoric meaning of the whole unit, e. g. to lose one’s n head, a fish out of water, to show one’s teeth, to wash one’s dirty linen in public, to sit on the fence etc. n n Phraseological fusions: completely non-motivated, i. e. the meaning of the components has no connection, at least synchronically, with the meaning of the whole group; characterised by complete stability of the lexical components and the grammatical structure of the whole unit, e. g. once in a blue moon, to be on the carpet, under the rose etc.

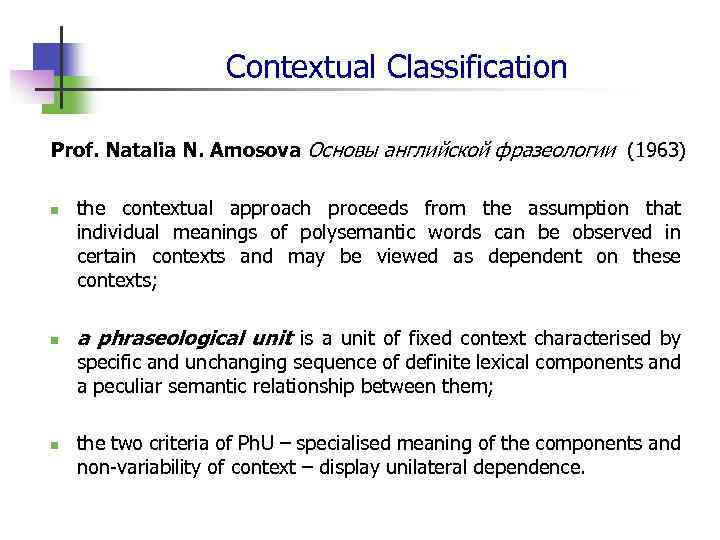

Contextual Classification Prof. Natalia N. Amosova Основы английской фразеологии (1963) n n the contextual approach proceeds from the assumption that individual meanings of polysemantic words can be observed in certain contexts and may be viewed as dependent on these contexts; a phraseological unit is a unit of fixed context characterised by specific and unchanging sequence of definite lexical components and a peculiar semantic relationship between them; n the two criteria of Ph. U – specialised meaning of the components and non-variability of context – display unilateral dependence.

Contextual Classification Prof. Natalia N. Amosova Основы английской фразеологии (1963) n n the contextual approach proceeds from the assumption that individual meanings of polysemantic words can be observed in certain contexts and may be viewed as dependent on these contexts; a phraseological unit is a unit of fixed context characterised by specific and unchanging sequence of definite lexical components and a peculiar semantic relationship between them; n the two criteria of Ph. U – specialised meaning of the components and non-variability of context – display unilateral dependence.

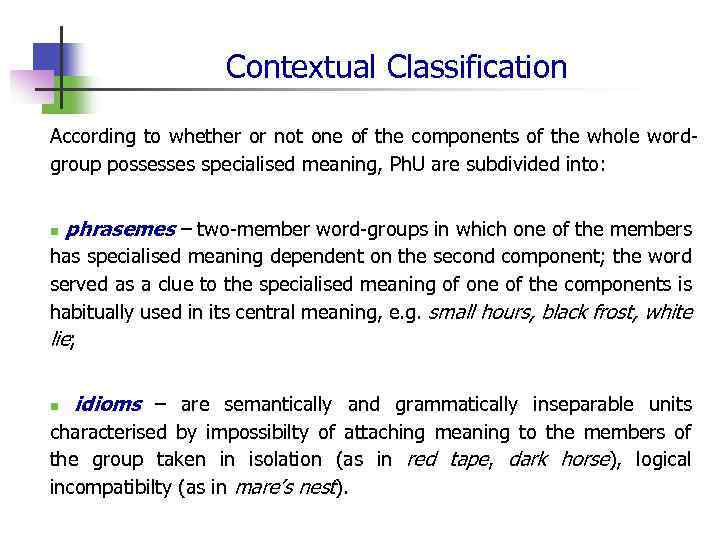

Contextual Classification According to whether or not one of the components of the whole wordgroup possesses specialised meaning, Ph. U are subdivided into: phrasemes – two-member word-groups in which one of the members has specialised meaning dependent on the second component; the word served as a clue to the specialised meaning of one of the components is habitually used in its central meaning, e. g. small hours, black frost, white lie; n idioms – are semantically and grammatically inseparable units characterised by impossibilty of attaching meaning to the members of the group taken in isolation (as in red tape, dark horse), logical incompatibilty (as in mare’s nest). n

Contextual Classification According to whether or not one of the components of the whole wordgroup possesses specialised meaning, Ph. U are subdivided into: phrasemes – two-member word-groups in which one of the members has specialised meaning dependent on the second component; the word served as a clue to the specialised meaning of one of the components is habitually used in its central meaning, e. g. small hours, black frost, white lie; n idioms – are semantically and grammatically inseparable units characterised by impossibilty of attaching meaning to the members of the group taken in isolation (as in red tape, dark horse), logical incompatibilty (as in mare’s nest). n

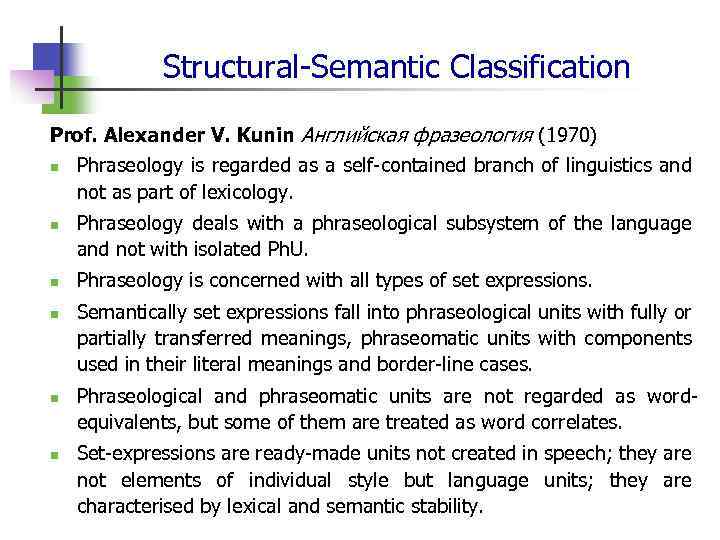

Structural-Semantic Classification Prof. Alexander V. Kunin Английская фразеология (1970) n Phraseology is regarded as a self-contained branch of linguistics and not as part of lexicology. n n n Phraseology deals with a phraseological subsystem of the language and not with isolated Ph. U. Phraseology is concerned with all types of set expressions. Semantically set expressions fall into phraseological units with fully or partially transferred meanings, phraseomatic units with components used in their literal meanings and border-line cases. Phraseological and phraseomatic units are not regarded as wordequivalents, but some of them are treated as word correlates. Set-expressions are ready-made units not created in speech; they are not elements of individual style but language units; they are characterised by lexical and semantic stability.

Structural-Semantic Classification Prof. Alexander V. Kunin Английская фразеология (1970) n Phraseology is regarded as a self-contained branch of linguistics and not as part of lexicology. n n n Phraseology deals with a phraseological subsystem of the language and not with isolated Ph. U. Phraseology is concerned with all types of set expressions. Semantically set expressions fall into phraseological units with fully or partially transferred meanings, phraseomatic units with components used in their literal meanings and border-line cases. Phraseological and phraseomatic units are not regarded as wordequivalents, but some of them are treated as word correlates. Set-expressions are ready-made units not created in speech; they are not elements of individual style but language units; they are characterised by lexical and semantic stability.

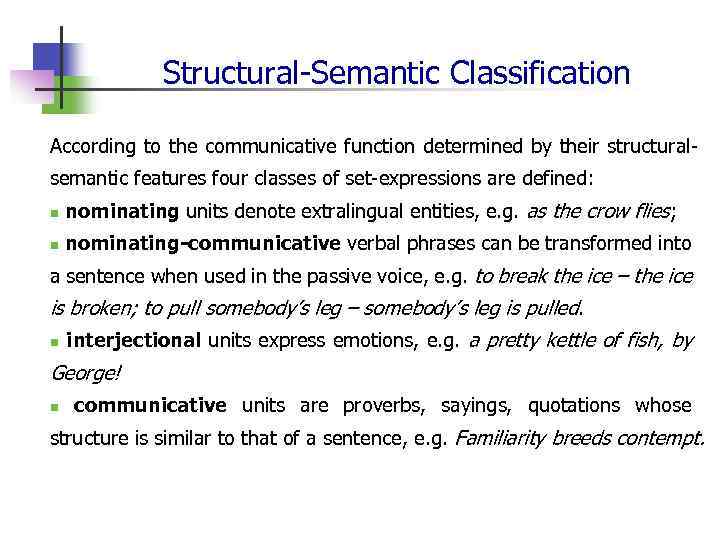

Structural-Semantic Classification According to the communicative function determined by their structuralsemantic features four classes of set-expressions are defined: n nominating units denote extralingual entities, e. g. as the crow flies; n nominating-communicative verbal phrases can be transformed into a sentence when used in the passive voice, e. g. to break the ice – the ice is broken; to pull somebody’s leg – somebody’s leg is pulled. n interjectional units express emotions, e. g. a pretty kettle of fish, by George! n communicative units are proverbs, sayings, quotations whose structure is similar to that of a sentence, e. g. Familiarity breeds contempt.

Structural-Semantic Classification According to the communicative function determined by their structuralsemantic features four classes of set-expressions are defined: n nominating units denote extralingual entities, e. g. as the crow flies; n nominating-communicative verbal phrases can be transformed into a sentence when used in the passive voice, e. g. to break the ice – the ice is broken; to pull somebody’s leg – somebody’s leg is pulled. n interjectional units express emotions, e. g. a pretty kettle of fish, by George! n communicative units are proverbs, sayings, quotations whose structure is similar to that of a sentence, e. g. Familiarity breeds contempt.

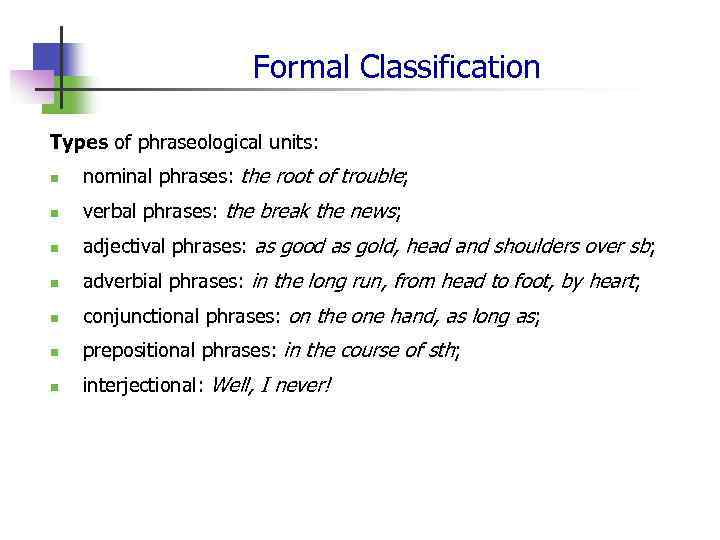

Formal Classification Types of phraseological units: n nominal phrases: the root of trouble; n verbal phrases: the break the news; n adjectival phrases: as good as gold, head and shoulders over sb; n adverbial phrases: in the long run, from head to foot, by heart; n conjunctional phrases: on the one hand, as long as; n prepositional phrases: in the course of sth; n interjectional: Well, I never!

Formal Classification Types of phraseological units: n nominal phrases: the root of trouble; n verbal phrases: the break the news; n adjectival phrases: as good as gold, head and shoulders over sb; n adverbial phrases: in the long run, from head to foot, by heart; n conjunctional phrases: on the one hand, as long as; n prepositional phrases: in the course of sth; n interjectional: Well, I never!

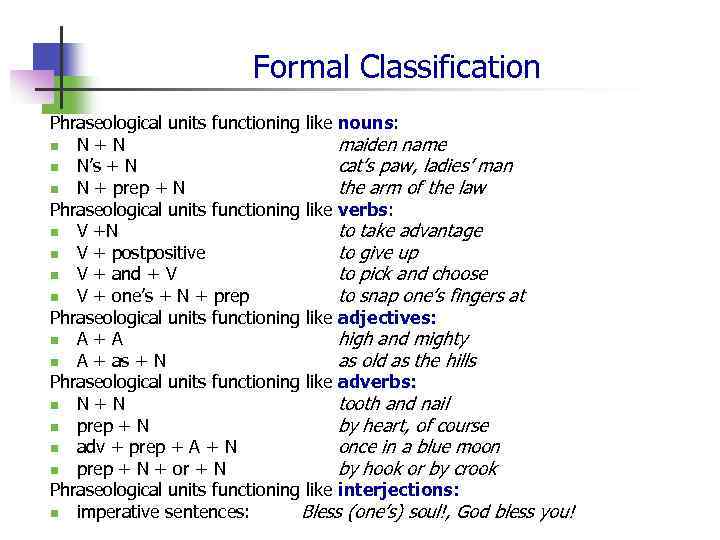

Formal Classification Phraseological units functioning like nouns: n N + N maiden name n N’s + N cat’s paw, ladies’ man n N + prep + N the arm of the law Phraseological units functioning like verbs: n V +N to take advantage n V + postpositive to give up n V + and + V to pick and choose n V + one’s + N + prep to snap one’s fingers at Phraseological units functioning like adjectives: n A + A high and mighty n A + as + N as old as the hills Phraseological units functioning like adverbs: n N + N tooth and nail n prep + N by heart, of course n adv + prep + A + N once in a blue moon n prep + N + or + N by hook or by crook Phraseological units functioning like interjections: n imperative sentences: Bless (one’s) soul!, God bless you!

Formal Classification Phraseological units functioning like nouns: n N + N maiden name n N’s + N cat’s paw, ladies’ man n N + prep + N the arm of the law Phraseological units functioning like verbs: n V +N to take advantage n V + postpositive to give up n V + and + V to pick and choose n V + one’s + N + prep to snap one’s fingers at Phraseological units functioning like adjectives: n A + A high and mighty n A + as + N as old as the hills Phraseological units functioning like adverbs: n N + N tooth and nail n prep + N by heart, of course n adv + prep + A + N once in a blue moon n prep + N + or + N by hook or by crook Phraseological units functioning like interjections: n imperative sentences: Bless (one’s) soul!, God bless you!

For more information visit: www. dariakuznyetsova. com

For more information visit: www. dariakuznyetsova. com