57a4e943ec532f67d97880d75bbcb37b.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 54

ENFORCEMENT AND CONSERVATION Councillor Information Session 6 th October 2010 18: 00 – 20: 00

ENFORCEMENT AND CONSERVATION Councillor Information Session 6 th October 2010 18: 00 – 20: 00

SERVICE IMPROVEMENT Elisa Dushku Service Improvement Officer T: 01933 231505 E: edushku@wellingborough. gov. uk

SERVICE IMPROVEMENT Elisa Dushku Service Improvement Officer T: 01933 231505 E: edushku@wellingborough. gov. uk

PLANNING ENFORCEMENT Ewen Rennie Planning Enforcement Officer T: 01933 231931 E: erennie@wellingborough. gov. uk

PLANNING ENFORCEMENT Ewen Rennie Planning Enforcement Officer T: 01933 231931 E: erennie@wellingborough. gov. uk

Aim of this Session To explain the basis of planning enforcement and the extent of Council remit. “We prefer to give planning authorities a complete and effective tool kit from which they can…deal with the particular breach. ” Baronness Blatch, House of Lords, January 1991

Aim of this Session To explain the basis of planning enforcement and the extent of Council remit. “We prefer to give planning authorities a complete and effective tool kit from which they can…deal with the particular breach. ” Baronness Blatch, House of Lords, January 1991

History of Planning Enforcement April 1989 – Review by Robert Carnwath QC was published, this provided the foundation for current legislation Parliament has given Local Planning Authorities (LPAs) the primary responsibility for taking enforcement action

History of Planning Enforcement April 1989 – Review by Robert Carnwath QC was published, this provided the foundation for current legislation Parliament has given Local Planning Authorities (LPAs) the primary responsibility for taking enforcement action

When a Complaint Is Received “Where is the harm? Where is the need? Where is the benefit? ” Consider both the alleged transgressor’s point of view, as well as complainant’s, in all cases. Site visit and assessment of situation.

When a Complaint Is Received “Where is the harm? Where is the need? Where is the benefit? ” Consider both the alleged transgressor’s point of view, as well as complainant’s, in all cases. Site visit and assessment of situation.

Breaches • • • Advertising Untidy land Unauthorised development Breach of condition Others Does not include: • High hedges • Neighbour disputes • Highway matters • Party Wall Act

Breaches • • • Advertising Untidy land Unauthorised development Breach of condition Others Does not include: • High hedges • Neighbour disputes • Highway matters • Party Wall Act

Courses of Action • • Request Application to Regularise Planning Contravention Notice Breach of Condition Notice Enforcement Notice Stop Notice/Temporary Stop Notice Injunction Section 215 Notice Direct action – several methods Timescales can vary

Courses of Action • • Request Application to Regularise Planning Contravention Notice Breach of Condition Notice Enforcement Notice Stop Notice/Temporary Stop Notice Injunction Section 215 Notice Direct action – several methods Timescales can vary

Enforcement Conclusion There is always an unhappy bunny at the end of any enforcement action, although we aim for a “win-win” result. There are limits to what the Council can enforce. We must be fair. “Enforcement should always be commensurate with the breach of planning control to which it relates. ” Carnwath QC, January 1989

Enforcement Conclusion There is always an unhappy bunny at the end of any enforcement action, although we aim for a “win-win” result. There are limits to what the Council can enforce. We must be fair. “Enforcement should always be commensurate with the breach of planning control to which it relates. ” Carnwath QC, January 1989

CONSERVATION Alex Stevenson Design and Conservation Officer T: 01933 231925 E: astevenson@wellingborough. gov. uk

CONSERVATION Alex Stevenson Design and Conservation Officer T: 01933 231925 E: astevenson@wellingborough. gov. uk

Aims of this Session To review and explain the content of the new Planning Policy Statement 5: “Planning for the Historic Environment”. To look at case studies local to Wellingborough and explain the conservation rationale.

Aims of this Session To review and explain the content of the new Planning Policy Statement 5: “Planning for the Historic Environment”. To look at case studies local to Wellingborough and explain the conservation rationale.

PPS 5 published in March 2010 • Provides a series of 12 policies: • Considers conservation of “heritage assets” holistically • Places conservation properly in a wider economic, urban design and environmental sustainability context • Introduces the concept of “significance” – development proposals to be assessed on their impact upon the significance of a heritage asset.

PPS 5 published in March 2010 • Provides a series of 12 policies: • Considers conservation of “heritage assets” holistically • Places conservation properly in a wider economic, urban design and environmental sustainability context • Introduces the concept of “significance” – development proposals to be assessed on their impact upon the significance of a heritage asset.

POLICY HE 1 Heritage Assets and Climate Change Heritage protection and mitigation of/adaptation to climate change are not necessarily incompatible. POLICY HE 2 Evidence Base for Plan-making Councils to compile and publish historical information and to maintain a record. POLICY HE 3 Plan-making and Heritage Assets Policies to include issues such as investment in enhancement/repair of neglected assets, local sense of place, economic regeneration and championing of high-quality design.

POLICY HE 1 Heritage Assets and Climate Change Heritage protection and mitigation of/adaptation to climate change are not necessarily incompatible. POLICY HE 2 Evidence Base for Plan-making Councils to compile and publish historical information and to maintain a record. POLICY HE 3 Plan-making and Heritage Assets Policies to include issues such as investment in enhancement/repair of neglected assets, local sense of place, economic regeneration and championing of high-quality design.

POLICY HE 4 Permitted Development and Article 4 Directions To be considered by Councils where the exercise of PD rights would undermine the aims for the historic environment. POLICY HE 5 Monitoring Indicators Monitor impact of planning policies and decisions on the historic environment and respond to issues of decay/loss of local heritage assets. POLICY HE 6 Information Requirements for Applications for Consent Affecting Heritage Assets Applicants required to submit a full “Impact Statement”. Authorities empowered to delay registration of schemes submitted without the requisite information.

POLICY HE 4 Permitted Development and Article 4 Directions To be considered by Councils where the exercise of PD rights would undermine the aims for the historic environment. POLICY HE 5 Monitoring Indicators Monitor impact of planning policies and decisions on the historic environment and respond to issues of decay/loss of local heritage assets. POLICY HE 6 Information Requirements for Applications for Consent Affecting Heritage Assets Applicants required to submit a full “Impact Statement”. Authorities empowered to delay registration of schemes submitted without the requisite information.

POLICY HE 7 Determination of “Heritage”-related Applications Take account of: routine conservation considerations; possibilities of enhancing the asset’s significance; issues of urban design/placemaking; issues of sustainability & economic vitality; contribution to the character and local distinctiveness of the historic environment. POLICIES HE 8 & 9 Designated and Undesignated Heritage Assets Presumption in favour of conservation of designated assets. Consent should be refused for work which would harm an asset unless: • Delivery of a wider public benefit can be demonstrated; • There is no economically viable use for the asset; • Conservation through grant funding or charitable/public ownership can be secured.

POLICY HE 7 Determination of “Heritage”-related Applications Take account of: routine conservation considerations; possibilities of enhancing the asset’s significance; issues of urban design/placemaking; issues of sustainability & economic vitality; contribution to the character and local distinctiveness of the historic environment. POLICIES HE 8 & 9 Designated and Undesignated Heritage Assets Presumption in favour of conservation of designated assets. Consent should be refused for work which would harm an asset unless: • Delivery of a wider public benefit can be demonstrated; • There is no economically viable use for the asset; • Conservation through grant funding or charitable/public ownership can be secured.

POLICY HE 10 The Setting of Designated Heritage Assets Schemes near listed buildings or adjacent to conservation areas should be designed to reinforce the significance of the asset. POLICY HE 11 Enabling Development Where otherwise inappropriate development is allowed on the basis of benefits accruing to a heritage asset. POLICY HE 12 Information Recording Loss of whole or parts of heritage assets, where agreed, should be adequately recorded and published by the developer.

POLICY HE 10 The Setting of Designated Heritage Assets Schemes near listed buildings or adjacent to conservation areas should be designed to reinforce the significance of the asset. POLICY HE 11 Enabling Development Where otherwise inappropriate development is allowed on the basis of benefits accruing to a heritage asset. POLICY HE 12 Information Recording Loss of whole or parts of heritage assets, where agreed, should be adequately recorded and published by the developer.

Before Church Way, Grendon After

Before Church Way, Grendon After

Stocks Hill, Finedon

Stocks Hill, Finedon

Church Farm House, Mile Street, Bozeat

Church Farm House, Mile Street, Bozeat

28 Church Street, Wellingborough

28 Church Street, Wellingborough

JOINT PLANNING UNIT Amy Burbidge E: amyburbidge@nnjpu. org. uk Abi Morgan E: abigailmorgan@nnjpu. org. uk

JOINT PLANNING UNIT Amy Burbidge E: amyburbidge@nnjpu. org. uk Abi Morgan E: abigailmorgan@nnjpu. org. uk

The government's approach to localism marks a fundamental shift in the way to approach good design and placemaking. Councils, and councillors, now have real freedom and power to influence the quality of their local area.

The government's approach to localism marks a fundamental shift in the way to approach good design and placemaking. Councils, and councillors, now have real freedom and power to influence the quality of their local area.

Our legacy.

Our legacy.

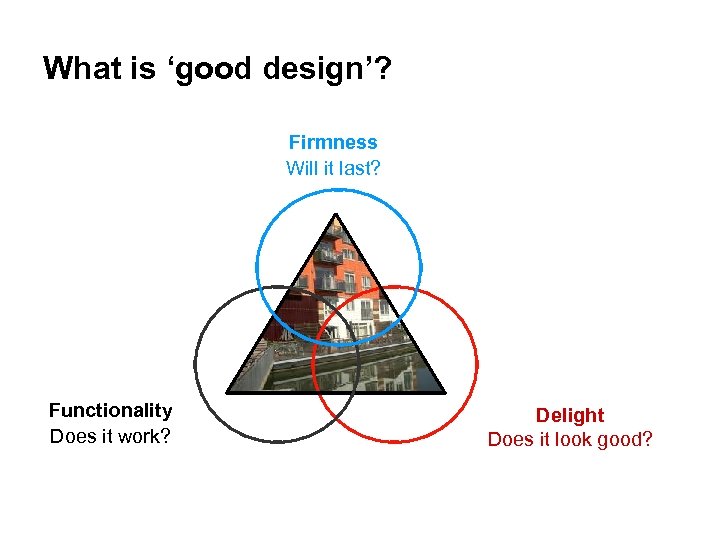

What is ‘good design’? Firmness Will it last? Functionality Does it work? Delight Does it look good?

What is ‘good design’? Firmness Will it last? Functionality Does it work? Delight Does it look good?

CABE – Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment Local involvement: • Help fund Design Action programme • Rural Masterplanning fund – Kettering and Rushden • Funding towards East Midlands and MKSM Architecture Centres and Design Review • Provide enabling advice to key projects like CSS review Produced revised guidance – “The Councillors Guide to Good Design” www. cabe. org. uk/councillors

CABE – Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment Local involvement: • Help fund Design Action programme • Rural Masterplanning fund – Kettering and Rushden • Funding towards East Midlands and MKSM Architecture Centres and Design Review • Provide enabling advice to key projects like CSS review Produced revised guidance – “The Councillors Guide to Good Design” www. cabe. org. uk/councillors

Seven principles of good design – to help you decide whether proposals are any good. • Character A place with its own identity • Continuity and enclosure - Where public and private spaces are clearly distinguished • Quality of the public realm - A place with attractive and well-used outdoor areas • Ease of Movement A place that is easy to get to and move through • Legibility A place that is easy to navigate • Adaptability A place that can change easily • Diversity A place with variety and choice

Seven principles of good design – to help you decide whether proposals are any good. • Character A place with its own identity • Continuity and enclosure - Where public and private spaces are clearly distinguished • Quality of the public realm - A place with attractive and well-used outdoor areas • Ease of Movement A place that is easy to get to and move through • Legibility A place that is easy to navigate • Adaptability A place that can change easily • Diversity A place with variety and choice

Character – A place with its own identity Sense of place

Character – A place with its own identity Sense of place

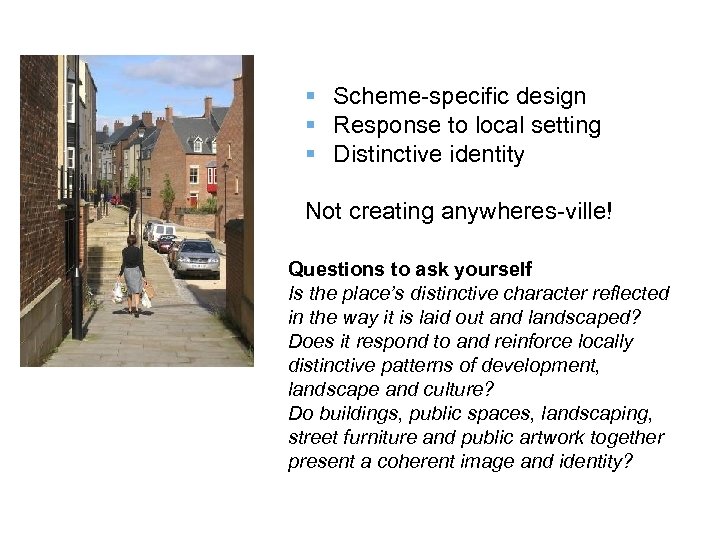

§ Scheme-specific design § Response to local setting § Distinctive identity Not creating anywheres-ville! Questions to ask yourself Is the place’s distinctive character reflected in the way it is laid out and landscaped? Does it respond to and reinforce locally distinctive patterns of development, landscape and culture? Do buildings, public spaces, landscaping, street furniture and public artwork together present a coherent image and identity?

§ Scheme-specific design § Response to local setting § Distinctive identity Not creating anywheres-ville! Questions to ask yourself Is the place’s distinctive character reflected in the way it is laid out and landscaped? Does it respond to and reinforce locally distinctive patterns of development, landscape and culture? Do buildings, public spaces, landscaping, street furniture and public artwork together present a coherent image and identity?

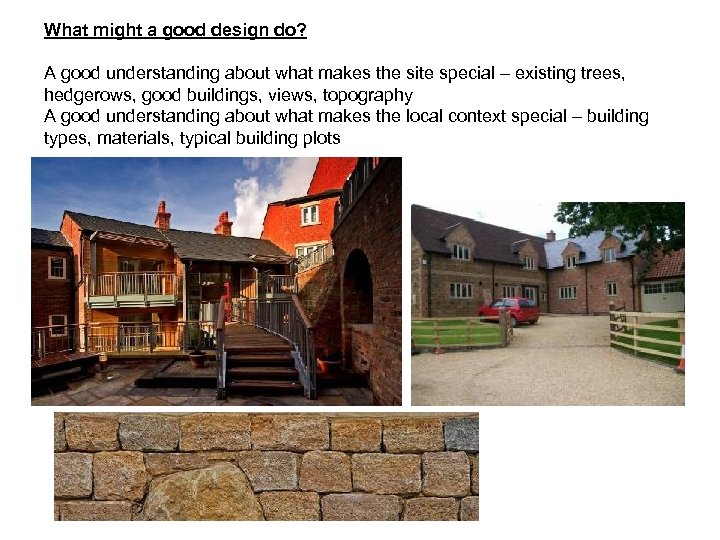

What might a good design do? A good understanding about what makes the site special – existing trees, hedgerows, good buildings, views, topography A good understanding about what makes the local context special – building types, materials, typical building plots

What might a good design do? A good understanding about what makes the site special – existing trees, hedgerows, good buildings, views, topography A good understanding about what makes the local context special – building types, materials, typical building plots

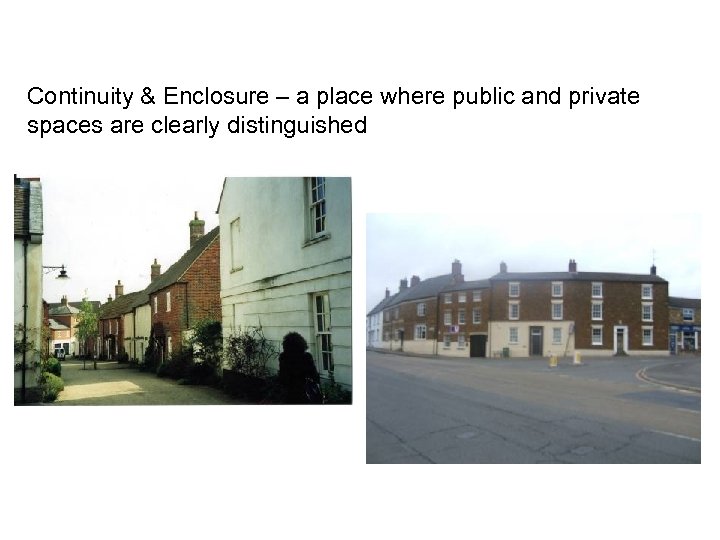

Continuity & Enclosure – a place where public and private spaces are clearly distinguished

Continuity & Enclosure – a place where public and private spaces are clearly distinguished

Design is clear and land is allocated Private areas are secure Front doors at the front! Eyes on the street No SLOAP – Space left over after planning Questions to ask yourself Is the street lively? Do people come and go from buildings and are they drawn to the activities inside buildings (retail, for example)? Are streets made up of continuous frontages of buildings and open spaces, or are there unintentional gaps that leave the street lifeless or uninteresting? Do buildings enclose space and separate private and public areas? Do buildings overlook public spaces to improve surveillance and security? In residential developments, are back garden fences accessible to intruders or are they closed off by other homes?

Design is clear and land is allocated Private areas are secure Front doors at the front! Eyes on the street No SLOAP – Space left over after planning Questions to ask yourself Is the street lively? Do people come and go from buildings and are they drawn to the activities inside buildings (retail, for example)? Are streets made up of continuous frontages of buildings and open spaces, or are there unintentional gaps that leave the street lifeless or uninteresting? Do buildings enclose space and separate private and public areas? Do buildings overlook public spaces to improve surveillance and security? In residential developments, are back garden fences accessible to intruders or are they closed off by other homes?

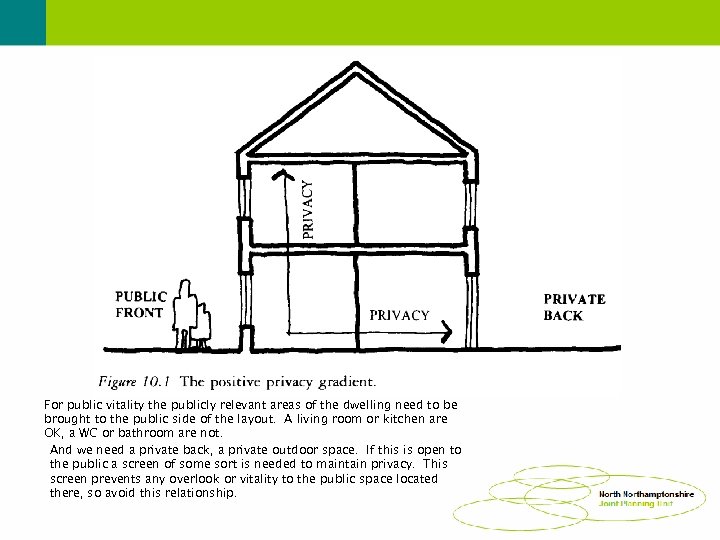

For public vitality the publicly relevant areas of the dwelling need to be brought to the public side of the layout. A living room or kitchen are OK, a WC or bathroom are not. And we need a private back, a private outdoor space. If this is open to the public a screen of some sort is needed to maintain privacy. This screen prevents any overlook or vitality to the public space located there, so avoid this relationship.

For public vitality the publicly relevant areas of the dwelling need to be brought to the public side of the layout. A living room or kitchen are OK, a WC or bathroom are not. And we need a private back, a private outdoor space. If this is open to the public a screen of some sort is needed to maintain privacy. This screen prevents any overlook or vitality to the public space located there, so avoid this relationship.

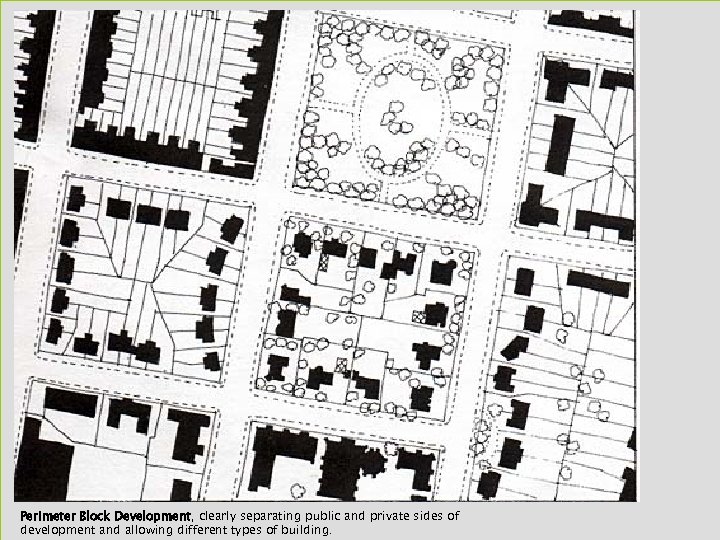

Perimeter Block Development, clearly separating public and private sides of development and allowing different types of building.

Perimeter Block Development, clearly separating public and private sides of development and allowing different types of building.

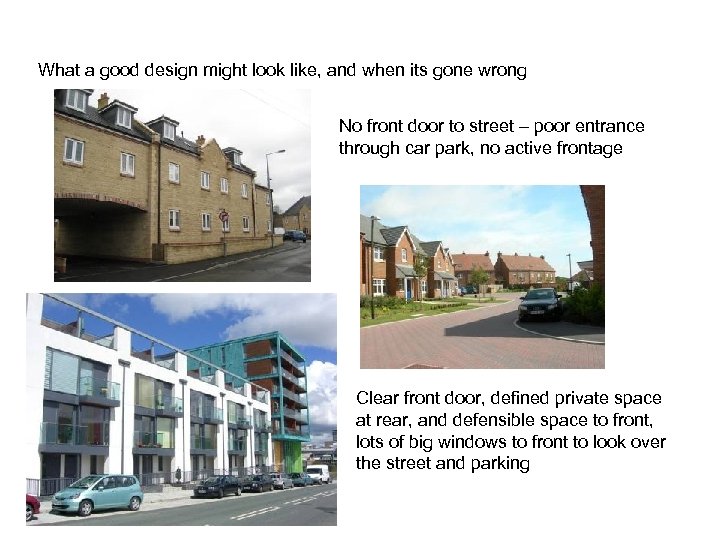

What a good design might look like, and when its gone wrong No front door to street – poor entrance through car park, no active frontage Clear front door, defined private space at rear, and defensible space to front, lots of big windows to front to look over the street and parking

What a good design might look like, and when its gone wrong No front door to street – poor entrance through car park, no active frontage Clear front door, defined private space at rear, and defensible space to front, lots of big windows to front to look over the street and parking

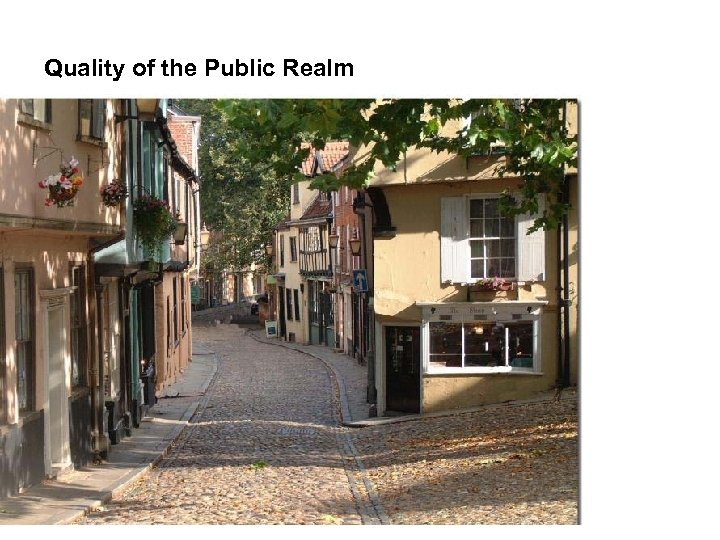

Quality of the Public Realm

Quality of the Public Realm

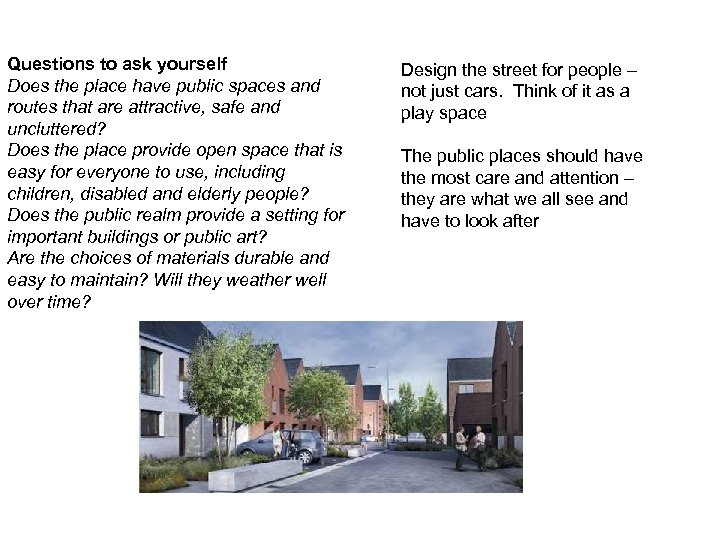

Questions to ask yourself Does the place have public spaces and routes that are attractive, safe and uncluttered? Does the place provide open space that is easy for everyone to use, including children, disabled and elderly people? Does the public realm provide a setting for important buildings or public art? Are the choices of materials durable and easy to maintain? Will they weather well over time? Design the street for people – not just cars. Think of it as a play space The public places should have the most care and attention – they are what we all see and have to look after

Questions to ask yourself Does the place have public spaces and routes that are attractive, safe and uncluttered? Does the place provide open space that is easy for everyone to use, including children, disabled and elderly people? Does the public realm provide a setting for important buildings or public art? Are the choices of materials durable and easy to maintain? Will they weather well over time? Design the street for people – not just cars. Think of it as a play space The public places should have the most care and attention – they are what we all see and have to look after

Good and bad examples

Good and bad examples

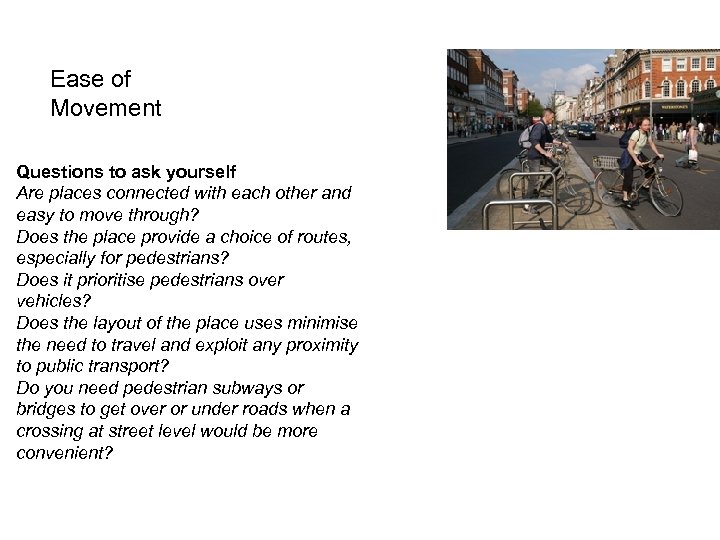

Ease of Movement Questions to ask yourself Are places connected with each other and easy to move through? Does the place provide a choice of routes, especially for pedestrians? Does it prioritise pedestrians over vehicles? Does the layout of the place uses minimise the need to travel and exploit any proximity to public transport? Do you need pedestrian subways or bridges to get over or under roads when a crossing at street level would be more convenient?

Ease of Movement Questions to ask yourself Are places connected with each other and easy to move through? Does the place provide a choice of routes, especially for pedestrians? Does it prioritise pedestrians over vehicles? Does the layout of the place uses minimise the need to travel and exploit any proximity to public transport? Do you need pedestrian subways or bridges to get over or under roads when a crossing at street level would be more convenient?

Appropriate street design

Appropriate street design

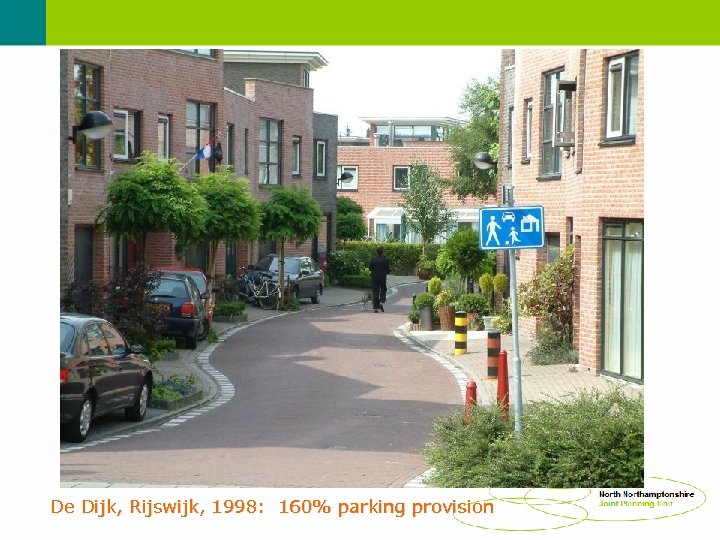

De Dijk, Rijswijk, 1998: 160% parking provision

De Dijk, Rijswijk, 1998: 160% parking provision

Legibility – A place that is easy to navigate

Legibility – A place that is easy to navigate

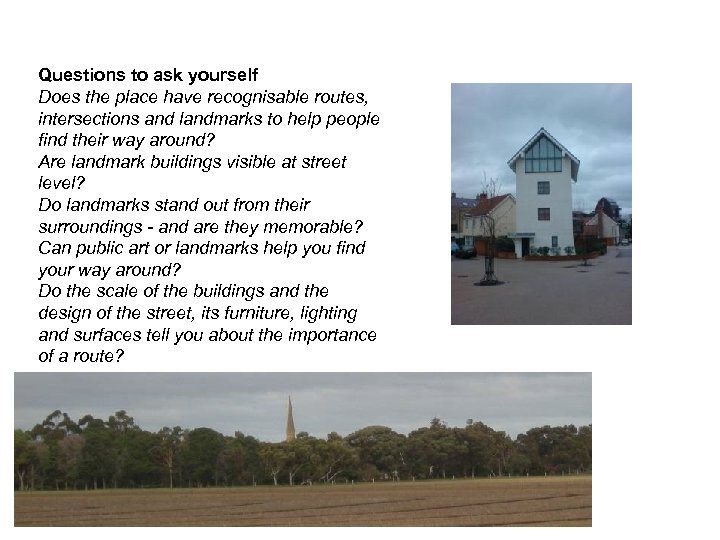

Questions to ask yourself Does the place have recognisable routes, intersections and landmarks to help people find their way around? Are landmark buildings visible at street level? Do landmarks stand out from their surroundings - and are they memorable? Can public art or landmarks help you find your way around? Do the scale of the buildings and the design of the street, its furniture, lighting and surfaces tell you about the importance of a route?

Questions to ask yourself Does the place have recognisable routes, intersections and landmarks to help people find their way around? Are landmark buildings visible at street level? Do landmarks stand out from their surroundings - and are they memorable? Can public art or landmarks help you find your way around? Do the scale of the buildings and the design of the street, its furniture, lighting and surfaces tell you about the importance of a route?

Adaptability – A place that can change over time Questions to ask yourself Can buildings be adapted to meet changing social, technological and economic conditions? Can existing buildings be adapted to new uses rather than replaced with new buildings? Can the design of the place be modified over time to cope with a changing climate? Does the design of major developments allow for incremental change instead of wholesale demolition? Can homes adapt to changing family needs including the needs of people with disabilities?

Adaptability – A place that can change over time Questions to ask yourself Can buildings be adapted to meet changing social, technological and economic conditions? Can existing buildings be adapted to new uses rather than replaced with new buildings? Can the design of the place be modified over time to cope with a changing climate? Does the design of major developments allow for incremental change instead of wholesale demolition? Can homes adapt to changing family needs including the needs of people with disabilities?

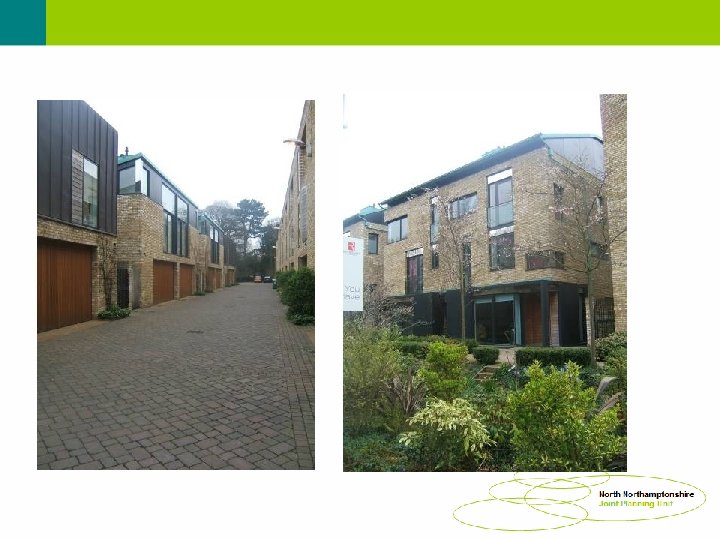

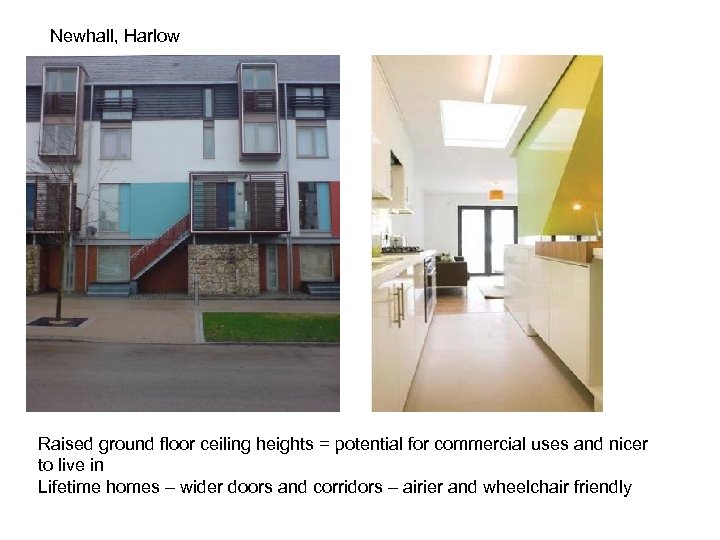

Newhall, Harlow Raised ground floor ceiling heights = potential for commercial uses and nicer to live in Lifetime homes – wider doors and corridors – airier and wheelchair friendly

Newhall, Harlow Raised ground floor ceiling heights = potential for commercial uses and nicer to live in Lifetime homes – wider doors and corridors – airier and wheelchair friendly

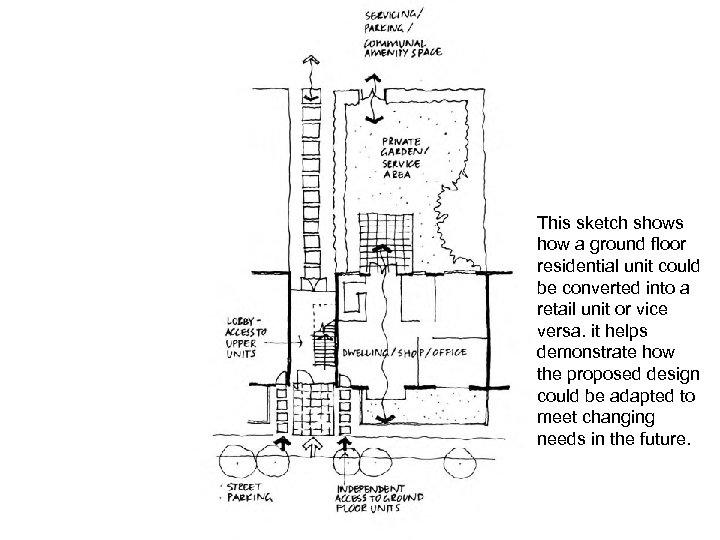

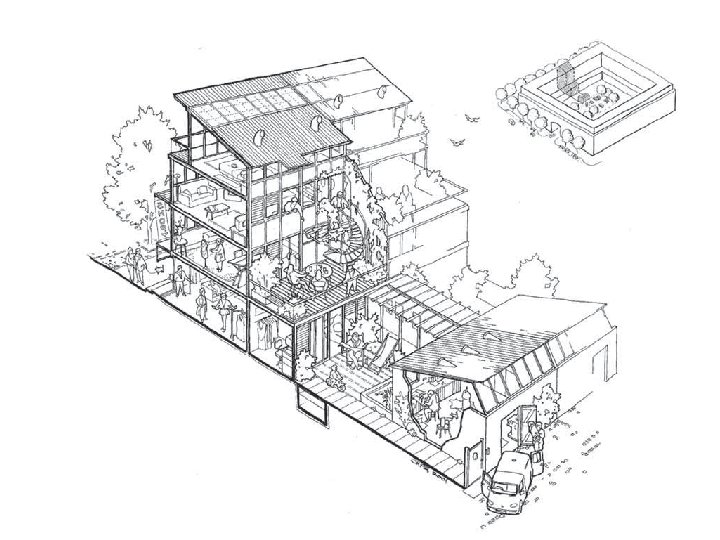

This sketch shows how a ground floor residential unit could be converted into a retail unit or vice versa. it helps demonstrate how the proposed design could be adapted to meet changing needs in the future.

This sketch shows how a ground floor residential unit could be converted into a retail unit or vice versa. it helps demonstrate how the proposed design could be adapted to meet changing needs in the future.

Designing in renewable energy generation

Designing in renewable energy generation

Diversity – a place with variety & choice Questions to ask yourself Can the mix of uses work together to create viable places that respond to local needs? Will the ranges of activities and uses of the area contribute to the vitality of the place at different times of the day and week? Is there a variety of building forms and architectural expression? Can everyone use the place, regardless of their physical ability? Does it promote biodiversity and a variety of habitats for wildlife? Does it provide people with a choice of housing, shopping, employment and entertainment? Does the place reflect the diversity of the local community and its culture? Can the development provide new local employment opportunities, for instance with live-work units?

Diversity – a place with variety & choice Questions to ask yourself Can the mix of uses work together to create viable places that respond to local needs? Will the ranges of activities and uses of the area contribute to the vitality of the place at different times of the day and week? Is there a variety of building forms and architectural expression? Can everyone use the place, regardless of their physical ability? Does it promote biodiversity and a variety of habitats for wildlife? Does it provide people with a choice of housing, shopping, employment and entertainment? Does the place reflect the diversity of the local community and its culture? Can the development provide new local employment opportunities, for instance with live-work units?

Variety

Variety

How to get more help. . . CABE has worked with almost every council in the country, helping in three key areas: • Expert advice on the design of new developments • Community engagement and partnership working • Strategic advice on planning and placemaking How to get this support from CABE? Ask!

How to get more help. . . CABE has worked with almost every council in the country, helping in three key areas: • Expert advice on the design of new developments • Community engagement and partnership working • Strategic advice on planning and placemaking How to get this support from CABE? Ask!

THANK YOU We do hope you have found this session helpful. The presentations will be sent by email for your future reference, but if you have any further questions please contact one of our officers who will be happy to help.

THANK YOU We do hope you have found this session helpful. The presentations will be sent by email for your future reference, but if you have any further questions please contact one of our officers who will be happy to help.