97d06f6d2bbb6a28caa709a655cb9def.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 59

Emotions Many thinkers disagree on answers to these questions: Is surprise an emotion? (Some people say “always”, others say “only in certain cases”. ) If you love your country, is that an emotion, or an attitude? What if your love for your country is far from your present thoughts? Can you have an emotion without being aware of it? E. g. jealousy, infatuation Does an emotion have to have some externally observable/measurable physiological manifestation? Can a fly feel pain, or have emotions? Is there a stage at which a human foetus becomes able to have emotions? E. g. able to worry about how the birth will go? Could a disembodied mathematician have emotions? E. g. feel disappointment at finding a flaw in a proof? There is no consensus about what emotions are

Emotions Many thinkers disagree on answers to these questions: Is surprise an emotion? (Some people say “always”, others say “only in certain cases”. ) If you love your country, is that an emotion, or an attitude? What if your love for your country is far from your present thoughts? Can you have an emotion without being aware of it? E. g. jealousy, infatuation Does an emotion have to have some externally observable/measurable physiological manifestation? Can a fly feel pain, or have emotions? Is there a stage at which a human foetus becomes able to have emotions? E. g. able to worry about how the birth will go? Could a disembodied mathematician have emotions? E. g. feel disappointment at finding a flaw in a proof? There is no consensus about what emotions are

Prejudices That Confuse the Investigation Some people assume: That minds must be “embodied” and emotions must involve bodies Ignoring the possibility of passionate disembodied mathematicians. That emotions are required for intelligence. That emotions evolved because they are useful Maybe some did. It does not follow that all are useful. Many may be sideeffects of other useful mechanisms. That you can’t have an emotion without being conscious of it. What about the person who is obviously infatuated or jealous but unaware of the fact? That it would be a “bad thing” if robots could have emotions. Could they possibly do worse things than humans do to other humans?

Prejudices That Confuse the Investigation Some people assume: That minds must be “embodied” and emotions must involve bodies Ignoring the possibility of passionate disembodied mathematicians. That emotions are required for intelligence. That emotions evolved because they are useful Maybe some did. It does not follow that all are useful. Many may be sideeffects of other useful mechanisms. That you can’t have an emotion without being conscious of it. What about the person who is obviously infatuated or jealous but unaware of the fact? That it would be a “bad thing” if robots could have emotions. Could they possibly do worse things than humans do to other humans?

A Tip for Doing Conceptual Analysis If someone puts forward a definition of mental state or process X, the question: “Does this also apply to X in flies, rats, chimpanzees, newborn infants? ” often reveals that the definition was not based on sufficient thought.

A Tip for Doing Conceptual Analysis If someone puts forward a definition of mental state or process X, the question: “Does this also apply to X in flies, rats, chimpanzees, newborn infants? ” often reveals that the definition was not based on sufficient thought.

A Control-based Conception of Emotion What is there in common between – a crawling woodlouse that rapidly curls up if suddenly tapped with a pencil, – a fly on the table that rapidly flies off when a swatter approaches, – a fox squealing and struggling to escape from the trap that has clamped its leg, – a child suddenly terrified by a large object rushing towards it, – a person who is startled by a moving shadow when walking in a dark passageway, – a rejected lover unable to put the humiliation out of mind – a mathematician upset on realizing that a proof of a hard theorem is fallacious, – a grieving parent, suddenly remembering the lost child while in the middle of some important task?

A Control-based Conception of Emotion What is there in common between – a crawling woodlouse that rapidly curls up if suddenly tapped with a pencil, – a fly on the table that rapidly flies off when a swatter approaches, – a fox squealing and struggling to escape from the trap that has clamped its leg, – a child suddenly terrified by a large object rushing towards it, – a person who is startled by a moving shadow when walking in a dark passageway, – a rejected lover unable to put the humiliation out of mind – a mathematician upset on realizing that a proof of a hard theorem is fallacious, – a grieving parent, suddenly remembering the lost child while in the middle of some important task?

A Control-based Conception of Emotion Proposed Answer: In all cases there at least two sub-systems at work in the organism, and one of them, a specialized sub-system, somehow interrupts or suppresses or changes the behavior of others, producing some alteration in (relatively) global (internal or external) behavior of the system.

A Control-based Conception of Emotion Proposed Answer: In all cases there at least two sub-systems at work in the organism, and one of them, a specialized sub-system, somehow interrupts or suppresses or changes the behavior of others, producing some alteration in (relatively) global (internal or external) behavior of the system.

A Control-based Conception of Emotion WE CAN MAKE IT MORE PRECISE BY: – spelling out different kinds of information-processing control architectures in which such things (e. g. global interrupts or modulations of processing) can occur – showing how different varieties of states with these general features can arise in different architectures. Different sorts of emotions (and other affective states) arise out of different sorts of: – Interacting sub-systems –Ways one can interrupt or modulate another – Functional roles and side-effects

A Control-based Conception of Emotion WE CAN MAKE IT MORE PRECISE BY: – spelling out different kinds of information-processing control architectures in which such things (e. g. global interrupts or modulations of processing) can occur – showing how different varieties of states with these general features can arise in different architectures. Different sorts of emotions (and other affective states) arise out of different sorts of: – Interacting sub-systems –Ways one can interrupt or modulate another – Functional roles and side-effects

Emotions are a Subclass of “Affective” States Affective states are of many kinds. They include not only what we ordinarily call emotions but also states involving desires, pleasures, pains, goals, values, ideals, attitudes, preferences, and moods. The general notion of “affective state” is very hard to define but very roughly it involves using some kind of information that is compared (explicitly or implicitly) against what is happening, sensed either internally or externally. –When there’s a discrepancy some action is taken, or tends to be taken to remove the discrepancy by acting on the sensed thing: affective states involve a disposition to change reality in some way to reduce a mismatch. – If the information is part of a percept or a belief, then detecting a discrepancy tends to produce a change in the stored “reference” information.

Emotions are a Subclass of “Affective” States Affective states are of many kinds. They include not only what we ordinarily call emotions but also states involving desires, pleasures, pains, goals, values, ideals, attitudes, preferences, and moods. The general notion of “affective state” is very hard to define but very roughly it involves using some kind of information that is compared (explicitly or implicitly) against what is happening, sensed either internally or externally. –When there’s a discrepancy some action is taken, or tends to be taken to remove the discrepancy by acting on the sensed thing: affective states involve a disposition to change reality in some way to reduce a mismatch. – If the information is part of a percept or a belief, then detecting a discrepancy tends to produce a change in the stored “reference” information.

Emotions are a Subclass of “Affective” States There is a more primitive type of control state which does not use any sort of description or representation that can be compared with reality, but merely generates action, or has a disposition to produce action (including resisting change). Many innate behaviors are like that. Are these “affective” states? There’s no right definition of such a vague notion.

Emotions are a Subclass of “Affective” States There is a more primitive type of control state which does not use any sort of description or representation that can be compared with reality, but merely generates action, or has a disposition to produce action (including resisting change). Many innate behaviors are like that. Are these “affective” states? There’s no right definition of such a vague notion.

Affect and Architecture As with emotions, which affective states are possible in an organism or machine will depend on the informationprocessing architecture of the whole system. We’ll consider three architectural layers: reactive deliberative meta-management and the different sorts of emotions that can be associated with them.

Affect and Architecture As with emotions, which affective states are possible in an organism or machine will depend on the informationprocessing architecture of the whole system. We’ll consider three architectural layers: reactive deliberative meta-management and the different sorts of emotions that can be associated with them.

States and Processes There at least three different classes of mental phenomena commonly referred to as “emotions”. Primary emotions Evolutionarily oldest – depend only on reactive mechanisms Secondary emotions Deliberative mechanisms generating these evolved later Tertiary emotions Newest and rarest: involve disruption of meta-management, e. g. loss of control of attention. These are usually not distinguished from secondary emotions These rather vaguely defined categories must be re-defined in terms of the information-processing architectures (virtual machine architectures) that make them possible. E. g. , an animal without deliberative mechanisms cannot have secondary emotions.

States and Processes There at least three different classes of mental phenomena commonly referred to as “emotions”. Primary emotions Evolutionarily oldest – depend only on reactive mechanisms Secondary emotions Deliberative mechanisms generating these evolved later Tertiary emotions Newest and rarest: involve disruption of meta-management, e. g. loss of control of attention. These are usually not distinguished from secondary emotions These rather vaguely defined categories must be re-defined in terms of the information-processing architectures (virtual machine architectures) that make them possible. E. g. , an animal without deliberative mechanisms cannot have secondary emotions.

Primary Emotions Examples of primary emotions familiar in humans Being startled by a loud noise Being frozen in terror as boulder crashes towards you, Being nauseated by a horrible smell In primary emotions, sensor states and/or internal reactive states trigger a fast but stupid reactive “alarm” mechanism that produces global changes in motors and internal reactive states. – Simple versions occur even in insects: when flee, fight, feed, freeze, or mate responses override other processes. (The five Fs!) – In humans these primary emotions often have sophisticated accompaniments that cannot occur in most other animals capable of having primary emotions. E. g. when we are aware of having them we are using meta-management mechanisms that are not needed for primary emotions. Often the primary emotion will immediately trigger some other kind, e. g. apprehension, a secondary or tertiary emotion.

Primary Emotions Examples of primary emotions familiar in humans Being startled by a loud noise Being frozen in terror as boulder crashes towards you, Being nauseated by a horrible smell In primary emotions, sensor states and/or internal reactive states trigger a fast but stupid reactive “alarm” mechanism that produces global changes in motors and internal reactive states. – Simple versions occur even in insects: when flee, fight, feed, freeze, or mate responses override other processes. (The five Fs!) – In humans these primary emotions often have sophisticated accompaniments that cannot occur in most other animals capable of having primary emotions. E. g. when we are aware of having them we are using meta-management mechanisms that are not needed for primary emotions. Often the primary emotion will immediately trigger some other kind, e. g. apprehension, a secondary or tertiary emotion.

Secondary Emotions Examples — You are: Afraid the bridge you are crossing may give way Relieved that you got to the far side safely Afraid the bridge your child is crossing may give way Worried about what to say during your interview Undecided whether to cancel your holiday in. . . Enjoying the prospect of success in your endeavor Secondary emotions are triggered by events in a deliberative sub-system. Some of these are triggered by thinking about what might happen, what might have happened, what did not happen, etc. , unlike primary emotions which are triggered only by actual occurrences. So secondary emotions require deliberative capabilities with ‘what if’, i. e. counterfactual, representational and reasoning capabilities. These are very subtle and complex requirements.

Secondary Emotions Examples — You are: Afraid the bridge you are crossing may give way Relieved that you got to the far side safely Afraid the bridge your child is crossing may give way Worried about what to say during your interview Undecided whether to cancel your holiday in. . . Enjoying the prospect of success in your endeavor Secondary emotions are triggered by events in a deliberative sub-system. Some of these are triggered by thinking about what might happen, what might have happened, what did not happen, etc. , unlike primary emotions which are triggered only by actual occurrences. So secondary emotions require deliberative capabilities with ‘what if’, i. e. counterfactual, representational and reasoning capabilities. These are very subtle and complex requirements.

Tertiary Emotions Examples — You are: Infatuated with someone you met recently Overwhelmed with grief Riddled with guilt about betraying a friend Full of excited anticipation of a loved one’s return Full of longing for your mother Basking in a warm glow of pride after winning an election Obsessed with jealousy about a colleague’s success These involve disruption of high level self monitoring and control mechanisms. I. e. , there is loss of control of thought processes. Thus they cannot occur in animals and machines that are incapable of having such control. An architecture including meta-management capabilities is required for tertiary emotions.

Tertiary Emotions Examples — You are: Infatuated with someone you met recently Overwhelmed with grief Riddled with guilt about betraying a friend Full of excited anticipation of a loved one’s return Full of longing for your mother Basking in a warm glow of pride after winning an election Obsessed with jealousy about a colleague’s success These involve disruption of high level self monitoring and control mechanisms. I. e. , there is loss of control of thought processes. Thus they cannot occur in animals and machines that are incapable of having such control. An architecture including meta-management capabilities is required for tertiary emotions.

Emotions and Architectures In all of the categories (primary, secondary, tertiary emotions) there is a subsystem that produces some relatively global changes in the rest of the system, or in much of it. They differ in – What kind of subsystem does the disrupting – Where the information comes from that triggers the disrupting (e. g. does it come from a deliberative layer, or only sensors and internal states of a reactive layer? ) – Which parts of the system are disrupted, e. g. is there externally visible behaviour or only internal disruption? Which internal parts? – Also there are differences in kind of semantic content, time scale, what can and cannot suppress the disruption, whether learning is involved, etc.

Emotions and Architectures In all of the categories (primary, secondary, tertiary emotions) there is a subsystem that produces some relatively global changes in the rest of the system, or in much of it. They differ in – What kind of subsystem does the disrupting – Where the information comes from that triggers the disrupting (e. g. does it come from a deliberative layer, or only sensors and internal states of a reactive layer? ) – Which parts of the system are disrupted, e. g. is there externally visible behaviour or only internal disruption? Which internal parts? – Also there are differences in kind of semantic content, time scale, what can and cannot suppress the disruption, whether learning is involved, etc.

Classes Not Mutually Exclusive All three kinds of emotional processes can coexist in complex situations. As a result of this, the emotions labeled in ordinary language, e. g. “fear”, “anger”, “relief”, “distress”, cannot simply be classified as primary, secondary or tertiary. Often they are a mixture. People involved in long and tiring adventure trips often describe multiple emotions at the end. E. g. they may be simultaneously: Glad to have succeeded in their aims Regretful at not having done better Sad that the trip is over Relieved that some threat did not materialize (e. g. running out of fuel) Glad to see their families again Hoping to be selected for their national team Desperately longing for a good meal Worried about an injury incurred on the trip

Classes Not Mutually Exclusive All three kinds of emotional processes can coexist in complex situations. As a result of this, the emotions labeled in ordinary language, e. g. “fear”, “anger”, “relief”, “distress”, cannot simply be classified as primary, secondary or tertiary. Often they are a mixture. People involved in long and tiring adventure trips often describe multiple emotions at the end. E. g. they may be simultaneously: Glad to have succeeded in their aims Regretful at not having done better Sad that the trip is over Relieved that some threat did not materialize (e. g. running out of fuel) Glad to see their families again Hoping to be selected for their national team Desperately longing for a good meal Worried about an injury incurred on the trip

Architectural Underpinnings Different architectural underpinnings are required for different categories of emotions. Primary emotions: Require sensors linked to fast reactive mechanisms that can sometimes trigger rapid global signal patterns sent to motors and other sub-systems. Secondary emotions (central and peripheral): Require signals from deliberative mechanisms to fast reactive mechanisms that can, under certain conditions, trigger rapid global reactions. Tertiary emotions (with and without peripheral effects): Presuppose self-monitoring self-controlling meta-management systems that can be disrupted or modulated by other sub-processes.

Architectural Underpinnings Different architectural underpinnings are required for different categories of emotions. Primary emotions: Require sensors linked to fast reactive mechanisms that can sometimes trigger rapid global signal patterns sent to motors and other sub-systems. Secondary emotions (central and peripheral): Require signals from deliberative mechanisms to fast reactive mechanisms that can, under certain conditions, trigger rapid global reactions. Tertiary emotions (with and without peripheral effects): Presuppose self-monitoring self-controlling meta-management systems that can be disrupted or modulated by other sub-processes.

Further Refinements Finer emotional distinctions can be made when we understand the underlying architecture better. E. g. – “Purely central” vs “partly peripheral” secondary emotions. – Second-order emotions (being ashamed of feeling jealous). – Deliberately induced emotions (teacher who – reluctantly – allows himself to get angry to achieve control of a difficult class) – Emotions that involve constant activity (plotting, fretting, fuming, ranting). – Emotions that vary in intensity over time. – Long term, mostly dormant, emotions, e. g. jealousy, grief. (Often ignored. )

Further Refinements Finer emotional distinctions can be made when we understand the underlying architecture better. E. g. – “Purely central” vs “partly peripheral” secondary emotions. – Second-order emotions (being ashamed of feeling jealous). – Deliberately induced emotions (teacher who – reluctantly – allows himself to get angry to achieve control of a difficult class) – Emotions that involve constant activity (plotting, fretting, fuming, ranting). – Emotions that vary in intensity over time. – Long term, mostly dormant, emotions, e. g. jealousy, grief. (Often ignored. )

Important Human Emotions Socially important human emotions involve rich concepts and knowledge and high level control mechanisms (architectures). Example: longing for someone or something: Semantics: To long for something you need to know of its existence, its remoteness, and the possibility of being together again. Control: One who has deep longing for X does not merely occasionally think it would be wonderful to be with X. In deep longing, thoughts are often uncontrollably drawn to X. Moreover, such longing may impact on various kinds of high level decision making as well as the focus of attention. Physiological processes (outside the brain) may or may not be involved.

Important Human Emotions Socially important human emotions involve rich concepts and knowledge and high level control mechanisms (architectures). Example: longing for someone or something: Semantics: To long for something you need to know of its existence, its remoteness, and the possibility of being together again. Control: One who has deep longing for X does not merely occasionally think it would be wonderful to be with X. In deep longing, thoughts are often uncontrollably drawn to X. Moreover, such longing may impact on various kinds of high level decision making as well as the focus of attention. Physiological processes (outside the brain) may or may not be involved.

Summary So Far 1. We can reduce conceptual muddles regarding emotion by trying to use architecture-based concepts. 2. Different architectures are relevant in different contexts (e. g. infants, adults, other animals). So we need to explore different families of concepts (e. g. for describing infants, chimps, cats, people with brain damage). 3. Finding out which architectures are relevant is a hard research problem. One suggestion is that humans have three architectural layers that manifest themselves not only centrally but also in perception and action sub-systems. Most other animals have only a subset. 4. At least three (and several more if we look closely) classes of affective states and processes can be distinguished, related to different architectural layers. 5. Many other concepts (e. g. “learning”, “belief”, “motivation”, “intentional action”) can be refined on the basis of hypothesised architectures.

Summary So Far 1. We can reduce conceptual muddles regarding emotion by trying to use architecture-based concepts. 2. Different architectures are relevant in different contexts (e. g. infants, adults, other animals). So we need to explore different families of concepts (e. g. for describing infants, chimps, cats, people with brain damage). 3. Finding out which architectures are relevant is a hard research problem. One suggestion is that humans have three architectural layers that manifest themselves not only centrally but also in perception and action sub-systems. Most other animals have only a subset. 4. At least three (and several more if we look closely) classes of affective states and processes can be distinguished, related to different architectural layers. 5. Many other concepts (e. g. “learning”, “belief”, “motivation”, “intentional action”) can be refined on the basis of hypothesised architectures.

What Use are Emotions • In 1994 Antonio Damasio, a well known neuroscientist, published his book Descartes’ Error. He argued that emotions are needed for intelligence, and accused Descartes and many others of not grasping that. • In 1996 Daniel Goleman published Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ, quoting Damasio with approval. • Likewise Rosalind Picard a year later in her book Affective Computing. • Since then there has been a flood of publications and projects echoing Damasio’s claim, and many researchers in Artificial Intelligence have become convinced that emotions are essential for intelligence, so they are now producing many computer models containing a module called ‘Emotion’. • Before that, serious researchers had begun to argue that the study of emotions and affect had not had its rightful place in psychology, and cognitive science, but the claims were moderate. E. g. a journal called Cognition and Emotion was started in 1987.

What Use are Emotions • In 1994 Antonio Damasio, a well known neuroscientist, published his book Descartes’ Error. He argued that emotions are needed for intelligence, and accused Descartes and many others of not grasping that. • In 1996 Daniel Goleman published Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ, quoting Damasio with approval. • Likewise Rosalind Picard a year later in her book Affective Computing. • Since then there has been a flood of publications and projects echoing Damasio’s claim, and many researchers in Artificial Intelligence have become convinced that emotions are essential for intelligence, so they are now producing many computer models containing a module called ‘Emotion’. • Before that, serious researchers had begun to argue that the study of emotions and affect had not had its rightful place in psychology, and cognitive science, but the claims were moderate. E. g. a journal called Cognition and Emotion was started in 1987.

What Use are Emotions Damasio’s argument rested heavily on two examples: • Phineas Gage: In 1848, an accidental explosion of a charge he had set blew his tamping iron through his head – destroying the left frontal part of his brain. “He lived, but having previously been a capable and efficient foreman, one with a well-balanced mind, and who was looked on as a shrewd smart business man, he was now fitful, irreverent, and grossly profane, showing little deference for his fellows. He was also impatient and obstinate, yet capricious and vacillating, unable to settle on any of the plans he devised for future action. His friends said he was No longer Gage. ” http: //www. deakin. edu. au/hbs/GAGEPAGE/Pgstory. htm

What Use are Emotions Damasio’s argument rested heavily on two examples: • Phineas Gage: In 1848, an accidental explosion of a charge he had set blew his tamping iron through his head – destroying the left frontal part of his brain. “He lived, but having previously been a capable and efficient foreman, one with a well-balanced mind, and who was looked on as a shrewd smart business man, he was now fitful, irreverent, and grossly profane, showing little deference for his fellows. He was also impatient and obstinate, yet capricious and vacillating, unable to settle on any of the plans he devised for future action. His friends said he was No longer Gage. ” http: //www. deakin. edu. au/hbs/GAGEPAGE/Pgstory. htm

What Use are Emotions • Elliot, Damasio’s patient (‘Elliot’ was not his real name. ) Following a brain tumor and subsequent operation, Elliot suffered damage in the same general brain area as Gage (left frontal lobe). Like Gage, he experienced a great change in personality. Elliot had been a successful family man, and successful in business. After his operation he became impulsive and lacking in self-discipline. He could not decide between options where making the decision was important but both options were equally good. He perseverated on unimportant tasks while failing to recognize priorities. He had lost all his business acumen and ended up impoverished, even losing his wife and family. He could no longer hold a steady job. Yet he did well on standard IQ tests. http: //serendip. brynmawr. edu/bb/damasio/

What Use are Emotions • Elliot, Damasio’s patient (‘Elliot’ was not his real name. ) Following a brain tumor and subsequent operation, Elliot suffered damage in the same general brain area as Gage (left frontal lobe). Like Gage, he experienced a great change in personality. Elliot had been a successful family man, and successful in business. After his operation he became impulsive and lacking in self-discipline. He could not decide between options where making the decision was important but both options were equally good. He perseverated on unimportant tasks while failing to recognize priorities. He had lost all his business acumen and ended up impoverished, even losing his wife and family. He could no longer hold a steady job. Yet he did well on standard IQ tests. http: //serendip. brynmawr. edu/bb/damasio/

What Follows? Both patients appeared to retain high intelligence as measured by standard tests, but not as measured by their ability to behave sensibly. Both had also lost certain kinds of emotional reactions.

What Follows? Both patients appeared to retain high intelligence as measured by standard tests, but not as measured by their ability to behave sensibly. Both had also lost certain kinds of emotional reactions.

Damasio’s Argument In a nutshell, here is the argument Damasio produced which many people in many academic disciplines enthusiastically accepted as valid: There are two factual premises from which a conclusion is drawn. P 1 Damage to frontal lobes impairs emotional capabilities P 2 Damage to frontal lobes impairs intelligence C Emotions are required for intelligence Is this a valid argument? One can argue that the conclusion does not follow from the premises. Whether the conclusion is true is a separate matter.

Damasio’s Argument In a nutshell, here is the argument Damasio produced which many people in many academic disciplines enthusiastically accepted as valid: There are two factual premises from which a conclusion is drawn. P 1 Damage to frontal lobes impairs emotional capabilities P 2 Damage to frontal lobes impairs intelligence C Emotions are required for intelligence Is this a valid argument? One can argue that the conclusion does not follow from the premises. Whether the conclusion is true is a separate matter.

Compare This Argument We ‘prove’ that cars need functioning horns in order to start, using two premises on which to base the conclusion: P 1 Damaging the battery stops the horn working in a car P 2 Damage to the battery prevents the car starting C A functioning horn is required for the car to start Does C follow from P 1 and P 2?

Compare This Argument We ‘prove’ that cars need functioning horns in order to start, using two premises on which to base the conclusion: P 1 Damaging the battery stops the horn working in a car P 2 Damage to the battery prevents the car starting C A functioning horn is required for the car to start Does C follow from P 1 and P 2?

A Critical Observation The following should occur to the thoughtful listener: • two capabilities A and B could presuppose some common mechanism M, so that • damaging M would damage both A and B • without either of A or B being required for the other. For instance, even if P 1 and P 2 are both true, you can damage the starter motor and leave the horn working, or damage the horn and leave the starter motor working!

A Critical Observation The following should occur to the thoughtful listener: • two capabilities A and B could presuppose some common mechanism M, so that • damaging M would damage both A and B • without either of A or B being required for the other. For instance, even if P 1 and P 2 are both true, you can damage the starter motor and leave the horn working, or damage the horn and leave the starter motor working!

Why Buy Damasio’s Argument A possible explanation for the surprising fact that so many intelligent people so easily accept what appears to be an invalid argument is sociological: they are part of a culture in which people want the conclusion to be true. There seems to be a wide-spread (though not universal) feeling, even among many scientists and philosophers, that intelligence, rationality, critical analysis, problem-solving powers, are over-valued, and that they have defects that can be overcome by emotional mechanisms. This leads people to like Damasio’s conclusion. They want it to be true. And this somehow causes them to accept as valid an argument for that conclusion, even though they would notice the flaw in a structurally similar argument for a different conclusion (e. g. the car horn example).

Why Buy Damasio’s Argument A possible explanation for the surprising fact that so many intelligent people so easily accept what appears to be an invalid argument is sociological: they are part of a culture in which people want the conclusion to be true. There seems to be a wide-spread (though not universal) feeling, even among many scientists and philosophers, that intelligence, rationality, critical analysis, problem-solving powers, are over-valued, and that they have defects that can be overcome by emotional mechanisms. This leads people to like Damasio’s conclusion. They want it to be true. And this somehow causes them to accept as valid an argument for that conclusion, even though they would notice the flaw in a structurally similar argument for a different conclusion (e. g. the car horn example).

On the Other Side. . . In fact Damasio produced additional theoretical explanations of what is going on, so, in principle, even though the quoted argument is invalid, the conclusion might turn out to be true and explained by his theories.

On the Other Side. . . In fact Damasio produced additional theoretical explanations of what is going on, so, in principle, even though the quoted argument is invalid, the conclusion might turn out to be true and explained by his theories.

Emotions and Interfaces Expressive Interfaces User Frustration Anthropomorphism in Interaction Synthetic Characters (Agents)

Emotions and Interfaces Expressive Interfaces User Frustration Anthropomorphism in Interaction Synthetic Characters (Agents)

Motivation functionality and performance aspects are not always sufficient to make users comfortable expressive interfaces can convey additional information to the user affective computing has to be used with care, it gets annoying very easily

Motivation functionality and performance aspects are not always sufficient to make users comfortable expressive interfaces can convey additional information to the user affective computing has to be used with care, it gets annoying very easily

Objectives be aware of the effects that the use of expressive computing methods can have in user interaction identify appropriate techniques that enhance the user’s comfort level with the system balance the quality, quantity, and expressiveness of feedback from the system to the user identify and avoid common mistakes that can lead to user frustration

Objectives be aware of the effects that the use of expressive computing methods can have in user interaction identify appropriate techniques that enhance the user’s comfort level with the system balance the quality, quantity, and expressiveness of feedback from the system to the user identify and avoid common mistakes that can lead to user frustration

How Interfaces Affect Users Expressive interfaces how the ‘appearance’ of an interface can elicit positive responses Negative aspects how computers frustrate users Anthropomorphism and interface agents The pros and cons Designing synthetic characters

How Interfaces Affect Users Expressive interfaces how the ‘appearance’ of an interface can elicit positive responses Negative aspects how computers frustrate users Anthropomorphism and interface agents The pros and cons Designing synthetic characters

Affective Aspects HCI has generally been about designing efficient and effective systems Recently, move towards considering how to design interactive systems to make people respond in certain ways e. g. to be happy, to be trusting, to learn, to be motivated

Affective Aspects HCI has generally been about designing efficient and effective systems Recently, move towards considering how to design interactive systems to make people respond in certain ways e. g. to be happy, to be trusting, to learn, to be motivated

Expressive Interfaces Colour, icons, sounds, graphical elements and animations are used to make the ‘look and feel’ of an interface appealing Conveys an emotional state In turn this can affect the usability of an interface People are prepared to put up with certain aspects of an interface (e. g. slow download rate) if the end result is very appealing and aesthetic

Expressive Interfaces Colour, icons, sounds, graphical elements and animations are used to make the ‘look and feel’ of an interface appealing Conveys an emotional state In turn this can affect the usability of an interface People are prepared to put up with certain aspects of an interface (e. g. slow download rate) if the end result is very appealing and aesthetic

Friendly Interfaces Microsoft pioneered friendly interfaces for technophobes - ‘At home with Bob’ software 3 D metaphors based on familiar places (e. g. living rooms) Agents in the guise of pets (e. g. bunny, dog) were included to talk to the user Make users feel more at ease and comfortable

Friendly Interfaces Microsoft pioneered friendly interfaces for technophobes - ‘At home with Bob’ software 3 D metaphors based on familiar places (e. g. living rooms) Agents in the guise of pets (e. g. bunny, dog) were included to talk to the user Make users feel more at ease and comfortable

User-created Expressiveness Users have created emoticons - compensate for lack of expressiveness in text communication: Happy : ) Sad : < Sick : X Mad >: Very angry >: -( Also use of icons and shorthand in text and instant messaging has emotional connotations, e. g. I 12 CU 2 NITE

User-created Expressiveness Users have created emoticons - compensate for lack of expressiveness in text communication: Happy : ) Sad : < Sick : X Mad >: Very angry >: -( Also use of icons and shorthand in text and instant messaging has emotional connotations, e. g. I 12 CU 2 NITE

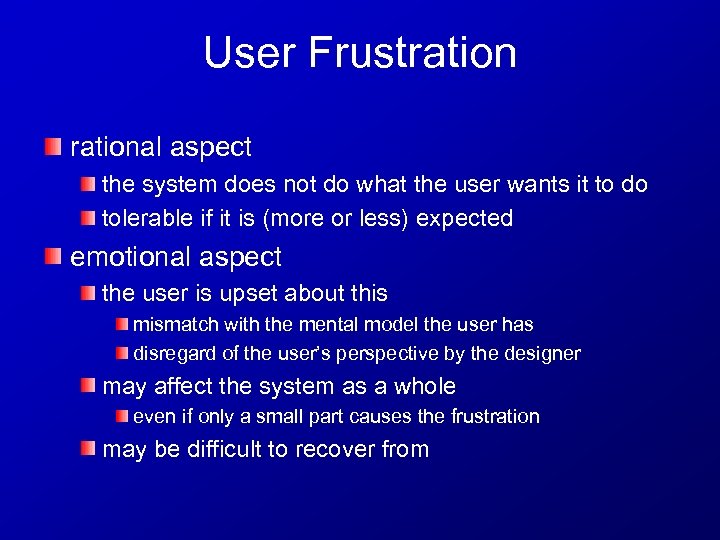

User Frustrational aspect the system does not do what the user wants it to do tolerable if it is (more or less) expected emotional aspect the user is upset about this mismatch with the mental model the user has disregard of the user’s perspective by the designer may affect the system as a whole even if only a small part causes the frustration may be difficult to recover from

User Frustrational aspect the system does not do what the user wants it to do tolerable if it is (more or less) expected emotional aspect the user is upset about this mismatch with the mental model the user has disregard of the user’s perspective by the designer may affect the system as a whole even if only a small part causes the frustration may be difficult to recover from

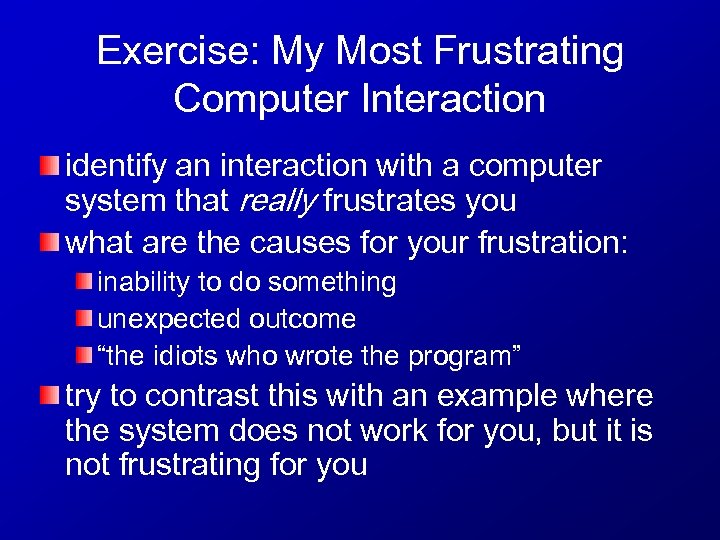

Exercise: My Most Frustrating Computer Interaction identify an interaction with a computer system that really frustrates you what are the causes for your frustration: inability to do something unexpected outcome “the idiots who wrote the program” try to contrast this with an example where the system does not work for you, but it is not frustrating for you

Exercise: My Most Frustrating Computer Interaction identify an interaction with a computer system that really frustrates you what are the causes for your frustration: inability to do something unexpected outcome “the idiots who wrote the program” try to contrast this with an example where the system does not work for you, but it is not frustrating for you

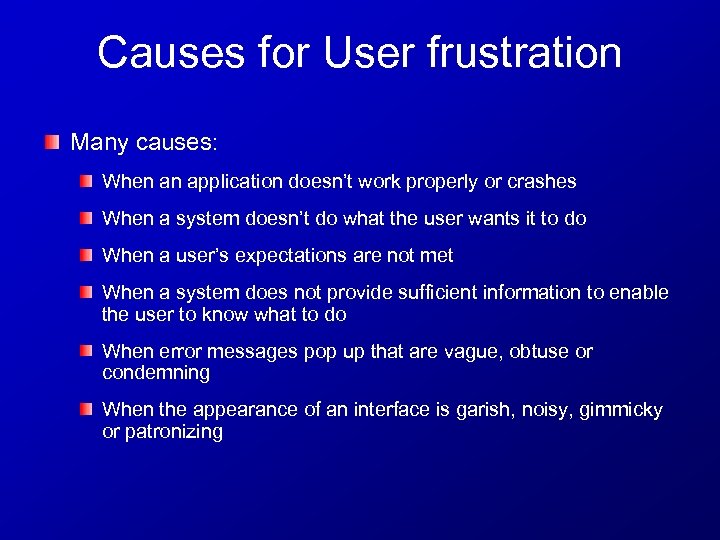

Causes for User frustration Many causes: When an application doesn’t work properly or crashes When a system doesn’t do what the user wants it to do When a user’s expectations are not met When a system does not provide sufficient information to enable the user to know what to do When error messages pop up that are vague, obtuse or condemning When the appearance of an interface is garish, noisy, gimmicky or patronizing

Causes for User frustration Many causes: When an application doesn’t work properly or crashes When a system doesn’t do what the user wants it to do When a user’s expectations are not met When a system does not provide sufficient information to enable the user to know what to do When error messages pop up that are vague, obtuse or condemning When the appearance of an interface is garish, noisy, gimmicky or patronizing

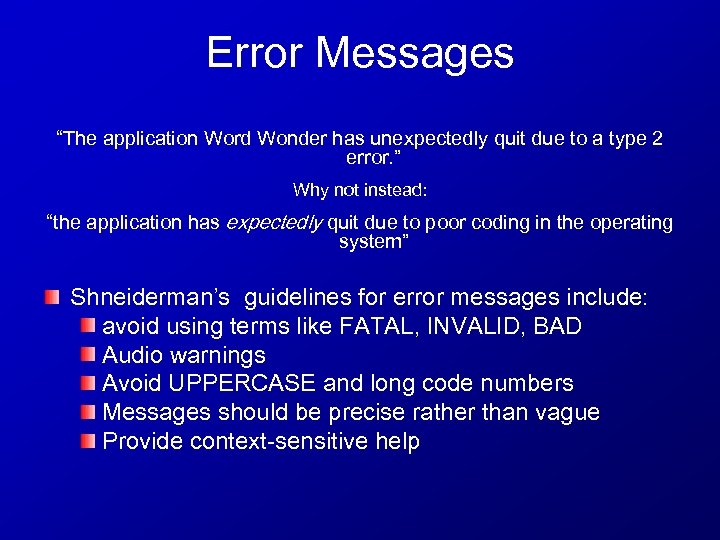

Error Messages “The application Word Wonder has unexpectedly quit due to a type 2 error. ” Why not instead: “the application has expectedly quit due to poor coding in the operating system” Shneiderman’s guidelines for error messages include: avoid using terms like FATAL, INVALID, BAD Audio warnings Avoid UPPERCASE and long code numbers Messages should be precise rather than vague Provide context-sensitive help

Error Messages “The application Word Wonder has unexpectedly quit due to a type 2 error. ” Why not instead: “the application has expectedly quit due to poor coding in the operating system” Shneiderman’s guidelines for error messages include: avoid using terms like FATAL, INVALID, BAD Audio warnings Avoid UPPERCASE and long code numbers Messages should be precise rather than vague Provide context-sensitive help

Website Error Message

Website Error Message

More Helpful Error Message “The requested page /helpme is not available on the web server. If you followed a link or bookmark to get to this page, please let us know, so that we can fix the problem. Please include the URL of the referring page as well as the URL of the missing page. Otherwise check that you have typed the address of the web page correctly. The Web site you seek Cannot be located, but Countless more exist. ”

More Helpful Error Message “The requested page /helpme is not available on the web server. If you followed a link or bookmark to get to this page, please let us know, so that we can fix the problem. Please include the URL of the referring page as well as the URL of the missing page. Otherwise check that you have typed the address of the web page correctly. The Web site you seek Cannot be located, but Countless more exist. ”

Should Computers Say They’re Sorry? Reeves and Naas (1996) argue that computers should be made to apologize Should emulate human etiquette Would users be as forgiving of computers saying sorry as people are of each other when saying sorry? How sincere would they think the computer was being? For example, after a system crash: “I’m really sorry I crashed. I’ll try not to do it again” How else should computers communicate with users?

Should Computers Say They’re Sorry? Reeves and Naas (1996) argue that computers should be made to apologize Should emulate human etiquette Would users be as forgiving of computers saying sorry as people are of each other when saying sorry? How sincere would they think the computer was being? For example, after a system crash: “I’m really sorry I crashed. I’ll try not to do it again” How else should computers communicate with users?

Anthropomorphism Attributing human-like qualities to inanimate objects (e. g. cars, computers) Well known phenomenon in advertising Dancing butter, drinks, breakfast cereals Much exploited in human-computer interaction Make user experience more enjoyable, more motivating, make people feel at ease, reduce anxiety

Anthropomorphism Attributing human-like qualities to inanimate objects (e. g. cars, computers) Well known phenomenon in advertising Dancing butter, drinks, breakfast cereals Much exploited in human-computer interaction Make user experience more enjoyable, more motivating, make people feel at ease, reduce anxiety

Which Do You Prefer? 1. As a welcome message “Hello Chris! Nice to see you again. Welcome back. Now what were we doing last time? Oh yes, exercise 5. Let’s start again. ” “User 24, commence exercise 5. ”

Which Do You Prefer? 1. As a welcome message “Hello Chris! Nice to see you again. Welcome back. Now what were we doing last time? Oh yes, exercise 5. Let’s start again. ” “User 24, commence exercise 5. ”

Which Do You Prefer? 2. Feedback when get something wrong 1. “Now Chris, that’s not right. You can do better than that. Try again. ” 2. “Incorrect. Try again. ” Is there a difference as to what you prefer depending on type of message? Why?

Which Do You Prefer? 2. Feedback when get something wrong 1. “Now Chris, that’s not right. You can do better than that. Try again. ” 2. “Incorrect. Try again. ” Is there a difference as to what you prefer depending on type of message? Why?

Evidence to Support Anthropomorphism Reeves and Naas (1996) found that computers that flatter and praise users in education software programs -> positive impact on them “Your question makes an important and useful distinction. Great job!” Students were more willing to continue with exercises with this kind of feedback

Evidence to Support Anthropomorphism Reeves and Naas (1996) found that computers that flatter and praise users in education software programs -> positive impact on them “Your question makes an important and useful distinction. Great job!” Students were more willing to continue with exercises with this kind of feedback

Criticism of Anthropomorphism Deceptive, make people feel anxious, inferior or stupid People tend not to like screen characters that wave their fingers at the user & say: Now Chris, that’s not right. You can do better than that. Try again. ” Many prefer the more impersonal: “Incorrect. Try again. ” Studies have shown that personalized feedback is considered to be less honest and makes users feel less responsible for their actions (e. g. Quintanar, 1982)

Criticism of Anthropomorphism Deceptive, make people feel anxious, inferior or stupid People tend not to like screen characters that wave their fingers at the user & say: Now Chris, that’s not right. You can do better than that. Try again. ” Many prefer the more impersonal: “Incorrect. Try again. ” Studies have shown that personalized feedback is considered to be less honest and makes users feel less responsible for their actions (e. g. Quintanar, 1982)

Virtual Characters Increasingly appearing on our screens Web, characters in videogames, learning companions, wizards, newsreaders, popstars Provides a persona that is welcoming, has personality and makes user feel involved with them

Virtual Characters Increasingly appearing on our screens Web, characters in videogames, learning companions, wizards, newsreaders, popstars Provides a persona that is welcoming, has personality and makes user feel involved with them

Virtual Characters in Video Games interaction: if you know that an entity in the game is virtual, do you interact with it differently? emotion: do virtual characters sometimes generate strong emotions?

Virtual Characters in Video Games interaction: if you know that an entity in the game is virtual, do you interact with it differently? emotion: do virtual characters sometimes generate strong emotions?

Disadvantages Lead people into false sense of belief, enticing them to confide personal secrets with chatterbots (e. g. Alice) Annoying and frustrating E. g. Clippy Not trustworthy virtual e-commerce assistants?

Disadvantages Lead people into false sense of belief, enticing them to confide personal secrets with chatterbots (e. g. Alice) Annoying and frustrating E. g. Clippy Not trustworthy virtual e-commerce assistants?

Virtual Characters: Agents Can be classified in terms of the degree of anthropomorphism they exhibit: • • Synthetic characters animated agents emotional agents embodied conversational agents

Virtual Characters: Agents Can be classified in terms of the degree of anthropomorphism they exhibit: • • Synthetic characters animated agents emotional agents embodied conversational agents

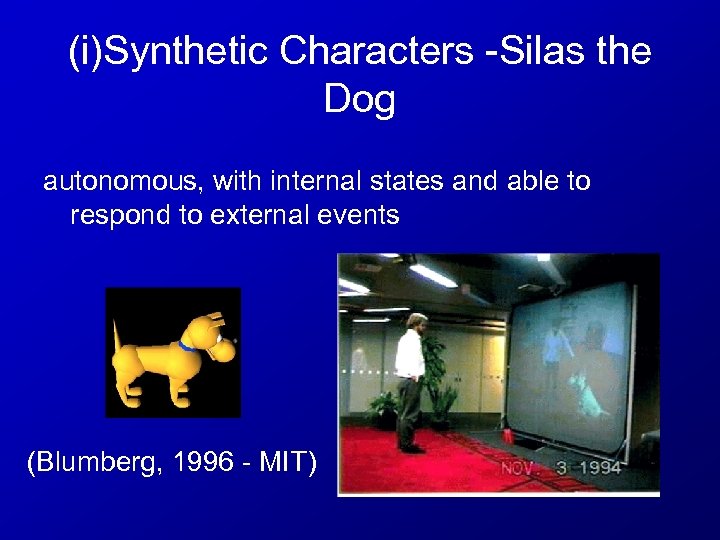

(i)Synthetic Characters -Silas the Dog autonomous, with internal states and able to respond to external events (Blumberg, 1996 - MIT)

(i)Synthetic Characters -Silas the Dog autonomous, with internal states and able to respond to external events (Blumberg, 1996 - MIT)

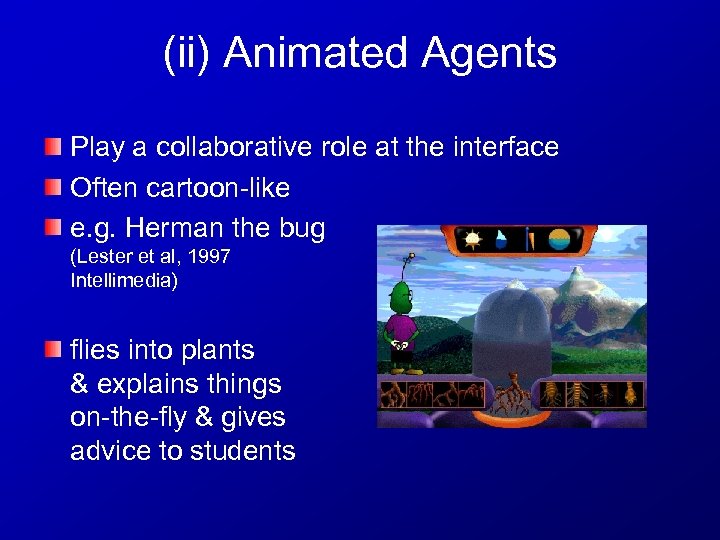

(ii) Animated Agents Play a collaborative role at the interface Often cartoon-like e. g. Herman the bug (Lester et al, 1997 Intellimedia) flies into plants & explains things on-the-fly & gives advice to students

(ii) Animated Agents Play a collaborative role at the interface Often cartoon-like e. g. Herman the bug (Lester et al, 1997 Intellimedia) flies into plants & explains things on-the-fly & gives advice to students

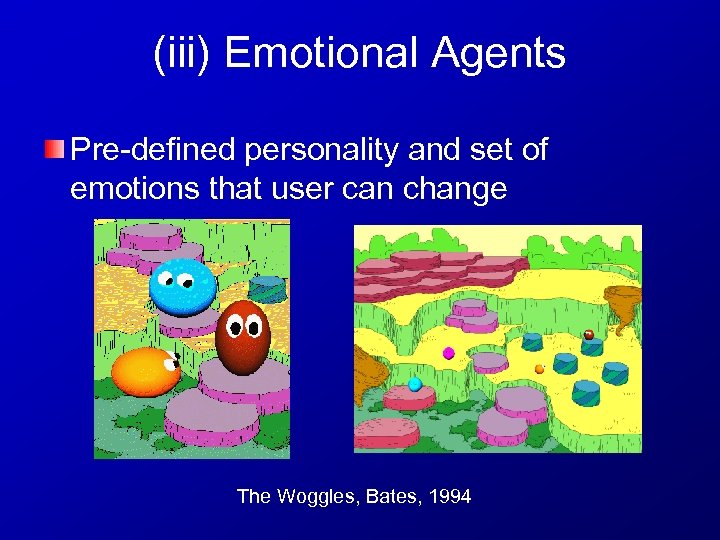

(iii) Emotional Agents Pre-defined personality and set of emotions that user can change The Woggles, Bates, 1994

(iii) Emotional Agents Pre-defined personality and set of emotions that user can change The Woggles, Bates, 1994

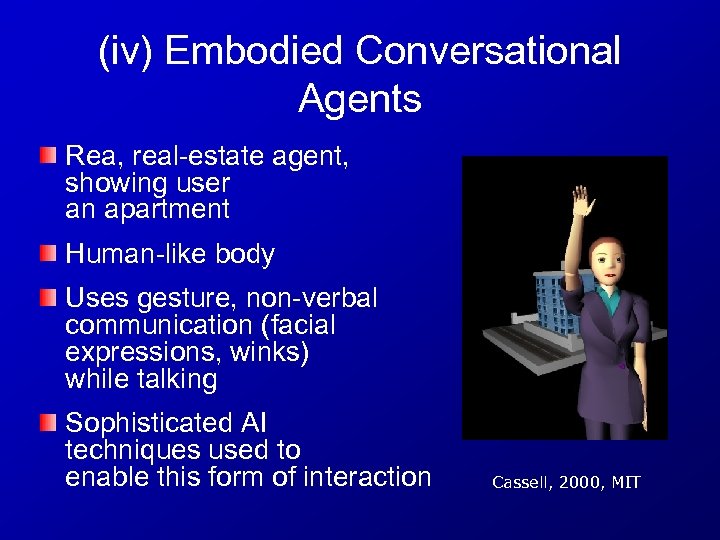

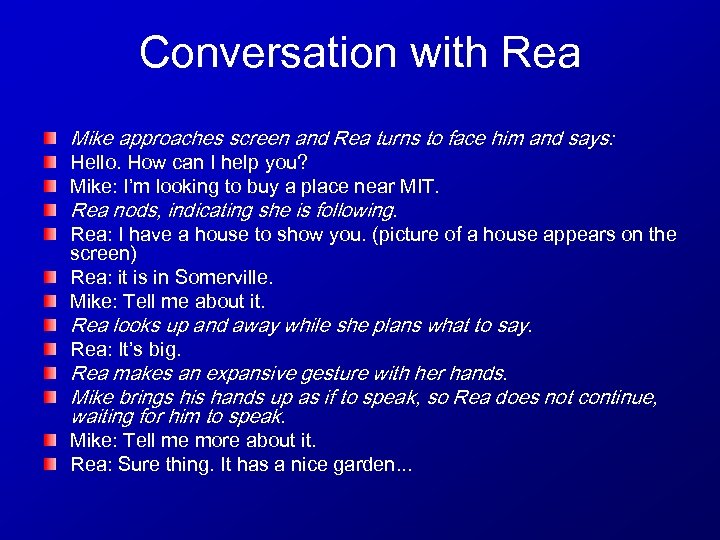

(iv) Embodied Conversational Agents Rea, real-estate agent, showing user an apartment Human-like body Uses gesture, non-verbal communication (facial expressions, winks) while talking Sophisticated AI techniques used to enable this form of interaction Cassell, 2000, MIT

(iv) Embodied Conversational Agents Rea, real-estate agent, showing user an apartment Human-like body Uses gesture, non-verbal communication (facial expressions, winks) while talking Sophisticated AI techniques used to enable this form of interaction Cassell, 2000, MIT

Conversation with Rea Mike approaches screen and Rea turns to face him and says: Hello. How can I help you? Mike: I’m looking to buy a place near MIT. Rea nods, indicating she is following. Rea: I have a house to show you. (picture of a house appears on the screen) Rea: it is in Somerville. Mike: Tell me about it. Rea looks up and away while she plans what to say. Rea: It’s big. Rea makes an expansive gesture with her hands. Mike brings his hands up as if to speak, so Rea does not continue, waiting for him to speak. Mike: Tell me more about it. Rea: Sure thing. It has a nice garden. . .

Conversation with Rea Mike approaches screen and Rea turns to face him and says: Hello. How can I help you? Mike: I’m looking to buy a place near MIT. Rea nods, indicating she is following. Rea: I have a house to show you. (picture of a house appears on the screen) Rea: it is in Somerville. Mike: Tell me about it. Rea looks up and away while she plans what to say. Rea: It’s big. Rea makes an expansive gesture with her hands. Mike brings his hands up as if to speak, so Rea does not continue, waiting for him to speak. Mike: Tell me more about it. Rea: Sure thing. It has a nice garden. . .

Believable Agents Believability refers to the extent to which users come to believe an agent’s intentions and personality Appearance is very important Are simple cartoon-like characters or more realistic characters, resembling the human form more believable? Behaviour is very important How an agent moves, gestures and refers to objects on the screen Exaggeration of facial expressions and gestures to show underlying emotions (cf animation industry)

Believable Agents Believability refers to the extent to which users come to believe an agent’s intentions and personality Appearance is very important Are simple cartoon-like characters or more realistic characters, resembling the human form more believable? Behaviour is very important How an agent moves, gestures and refers to objects on the screen Exaggeration of facial expressions and gestures to show underlying emotions (cf animation industry)

Key Points Affective aspects are concerned with how interactive systems make people respond in emotional ways Well-designed interfaces can elicit good feelings in users Expressive interfaces can provide reassuring feedback Badly designed interfaces make people angry and frustrated Anthropomorphism is increasingly used at the interface, in the guise of agents and virtual screen characters

Key Points Affective aspects are concerned with how interactive systems make people respond in emotional ways Well-designed interfaces can elicit good feelings in users Expressive interfaces can provide reassuring feedback Badly designed interfaces make people angry and frustrated Anthropomorphism is increasingly used at the interface, in the guise of agents and virtual screen characters