52098a53247c3c4dde5b5ae4ad72bea5.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 65

Efficency of Converting Solar Irradiance into Electrical or Chemical Free Energy A. J. Nozik National Renewable Energy Laboratory and Department of Chemistry, Univ. Colorado, Boulder

Efficency of Converting Solar Irradiance into Electrical or Chemical Free Energy A. J. Nozik National Renewable Energy Laboratory and Department of Chemistry, Univ. Colorado, Boulder

The U. S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory www. nrel. gov Golden, Colorado

The U. S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory www. nrel. gov Golden, Colorado

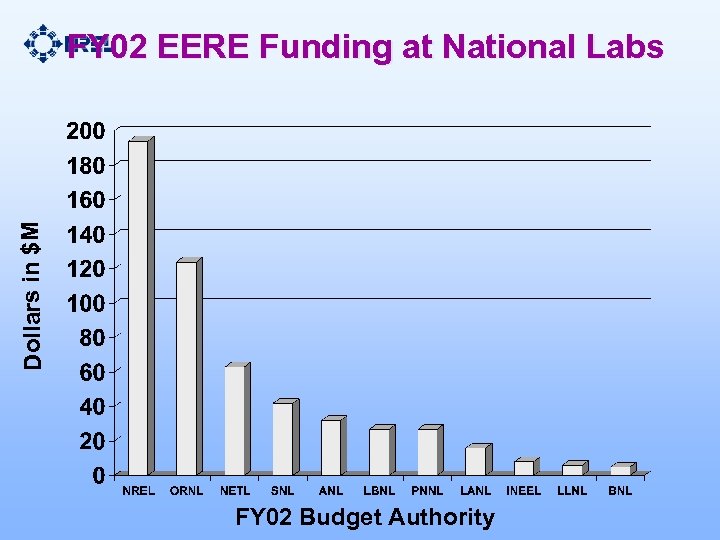

Dollars in $M FY 02 EERE Funding at National Labs FY 02 Budget Authority

Dollars in $M FY 02 EERE Funding at National Labs FY 02 Budget Authority

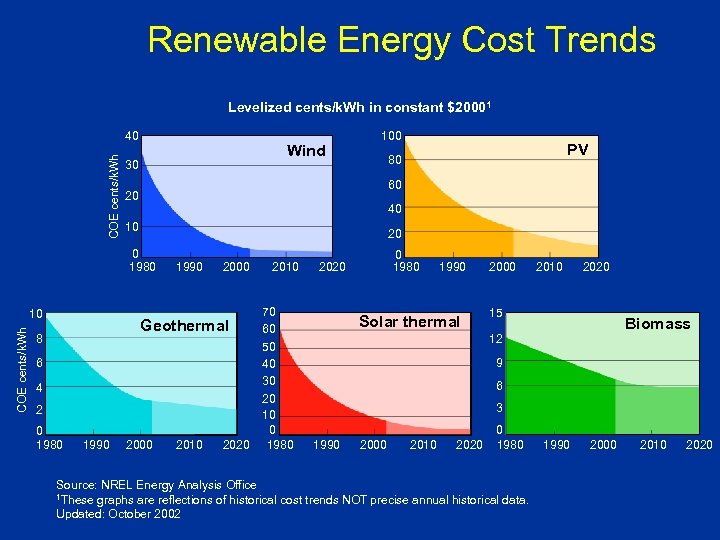

Renewable Energy Cost Trends Levelized cents/k. Wh in constant $20001 COE cents/k. Wh 40 Wind 30 60 40 10 20 COE cents/k. Wh 1990 2000 Geothermal 8 6 4 2 0 1980 1990 PV 80 20 0 1980 10 100 2010 2020 2010 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1980 2020 1990 Solar thermal 2000 2010 2020 15 Biomass 12 9 6 3 1990 2000 2010 2020 0 1980 Source: NREL Energy Analysis Office 1 These graphs are reflections of historical cost trends NOT precise annual historical data. Updated: October 2002 1990 2000 2010 2020

Renewable Energy Cost Trends Levelized cents/k. Wh in constant $20001 COE cents/k. Wh 40 Wind 30 60 40 10 20 COE cents/k. Wh 1990 2000 Geothermal 8 6 4 2 0 1980 1990 PV 80 20 0 1980 10 100 2010 2020 2010 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1980 2020 1990 Solar thermal 2000 2010 2020 15 Biomass 12 9 6 3 1990 2000 2010 2020 0 1980 Source: NREL Energy Analysis Office 1 These graphs are reflections of historical cost trends NOT precise annual historical data. Updated: October 2002 1990 2000 2010 2020

Solar Spectrum and Available Photocurrent

Solar Spectrum and Available Photocurrent

Solar Electricity ● Solar Fuels

Solar Electricity ● Solar Fuels

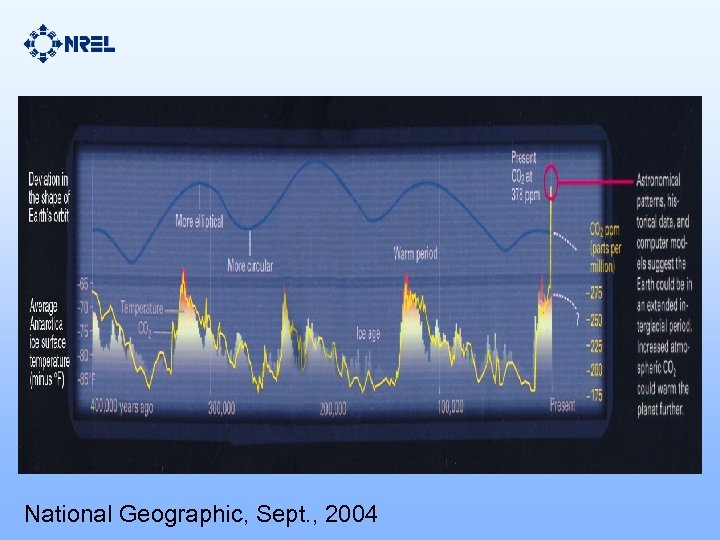

National Geographic, Sept. , 2004

National Geographic, Sept. , 2004

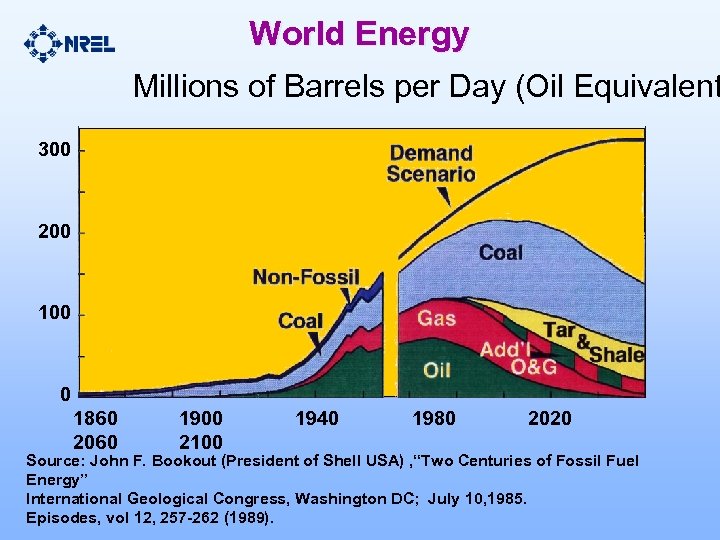

World Energy Millions of Barrels per Day (Oil Equivalent 300 200 100 0 1860 2060 1900 2100 1940 1980 2020 Source: John F. Bookout (President of Shell USA) , “Two Centuries of Fossil Fuel Energy” International Geological Congress, Washington DC; July 10, 1985. Episodes, vol 12, 257 -262 (1989).

World Energy Millions of Barrels per Day (Oil Equivalent 300 200 100 0 1860 2060 1900 2100 1940 1980 2020 Source: John F. Bookout (President of Shell USA) , “Two Centuries of Fossil Fuel Energy” International Geological Congress, Washington DC; July 10, 1985. Episodes, vol 12, 257 -262 (1989).

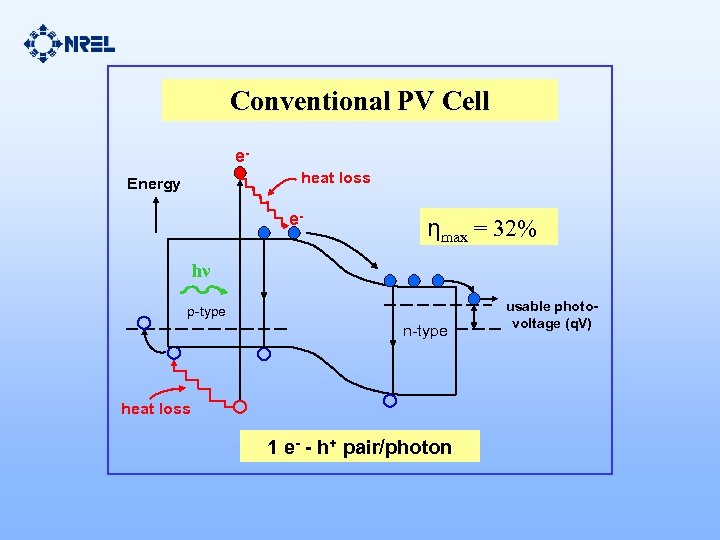

Conventional PV Cell eheat loss Energy e- ηmax = 32% hν p-type n-type heat loss 1 e- - h+ pair/photon usable photovoltage (q. V)

Conventional PV Cell eheat loss Energy e- ηmax = 32% hν p-type n-type heat loss 1 e- - h+ pair/photon usable photovoltage (q. V)

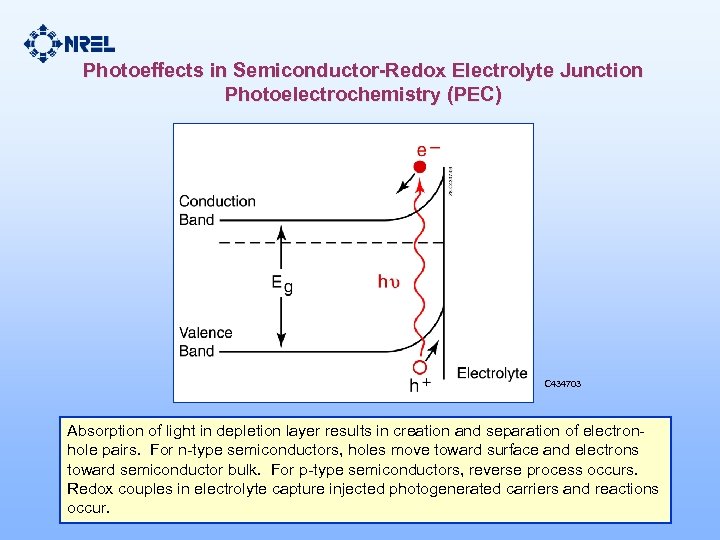

Photoeffects in Semiconductor-Redox Electrolyte Junction Photoelectrochemistry (PEC) C 434703 Absorption of light in depletion layer results in creation and separation of electronhole pairs. For n-type semiconductors, holes move toward surface and electrons toward semiconductor bulk. For p-type semiconductors, reverse process occurs. Redox couples in electrolyte capture injected photogenerated carriers and reactions occur.

Photoeffects in Semiconductor-Redox Electrolyte Junction Photoelectrochemistry (PEC) C 434703 Absorption of light in depletion layer results in creation and separation of electronhole pairs. For n-type semiconductors, holes move toward surface and electrons toward semiconductor bulk. For p-type semiconductors, reverse process occurs. Redox couples in electrolyte capture injected photogenerated carriers and reactions occur.

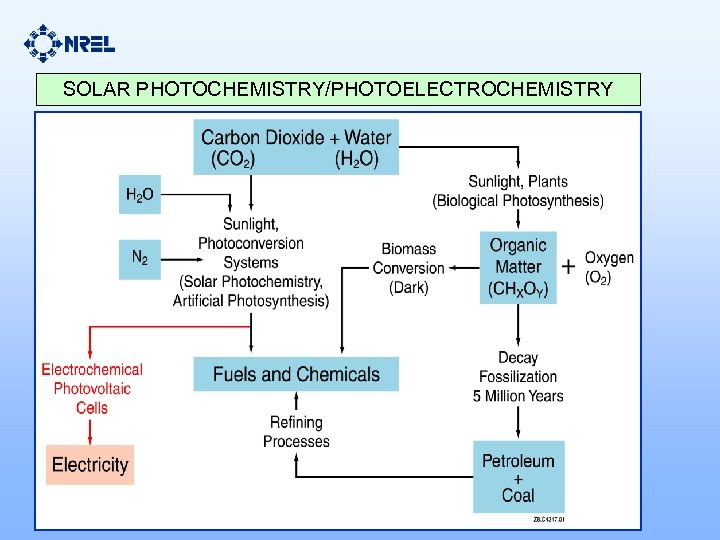

SOLAR PHOTOCHEMISTRY/PHOTOELECTROCHEMISTRY

SOLAR PHOTOCHEMISTRY/PHOTOELECTROCHEMISTRY

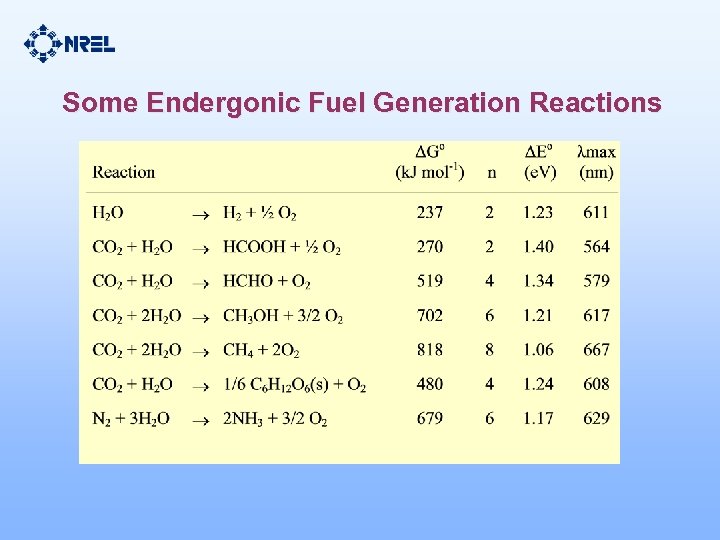

Some Endergonic Fuel Generation Reactions

Some Endergonic Fuel Generation Reactions

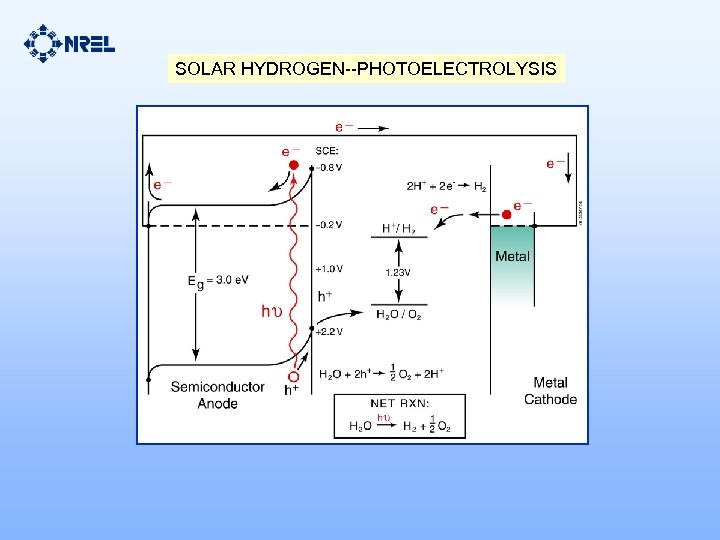

SOLAR HYDROGEN--PHOTOELECTROLYSIS

SOLAR HYDROGEN--PHOTOELECTROLYSIS

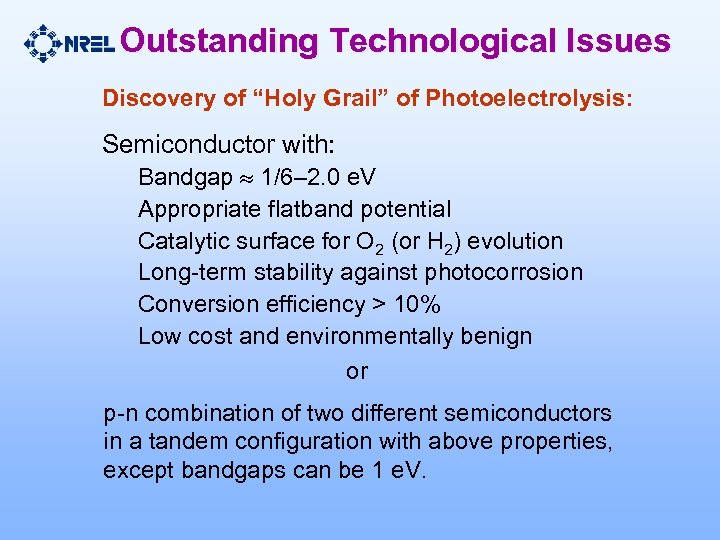

Outstanding Technological Issues Discovery of “Holy Grail” of Photoelectrolysis: Semiconductor with: Bandgap 1/6– 2. 0 e. V Appropriate flatband potential Catalytic surface for O 2 (or H 2) evolution Long-term stability against photocorrosion Conversion efficiency > 10% Low cost and environmentally benign or p-n combination of two different semiconductors in a tandem configuration with above properties, except bandgaps can be 1 e. V.

Outstanding Technological Issues Discovery of “Holy Grail” of Photoelectrolysis: Semiconductor with: Bandgap 1/6– 2. 0 e. V Appropriate flatband potential Catalytic surface for O 2 (or H 2) evolution Long-term stability against photocorrosion Conversion efficiency > 10% Low cost and environmentally benign or p-n combination of two different semiconductors in a tandem configuration with above properties, except bandgaps can be 1 e. V.

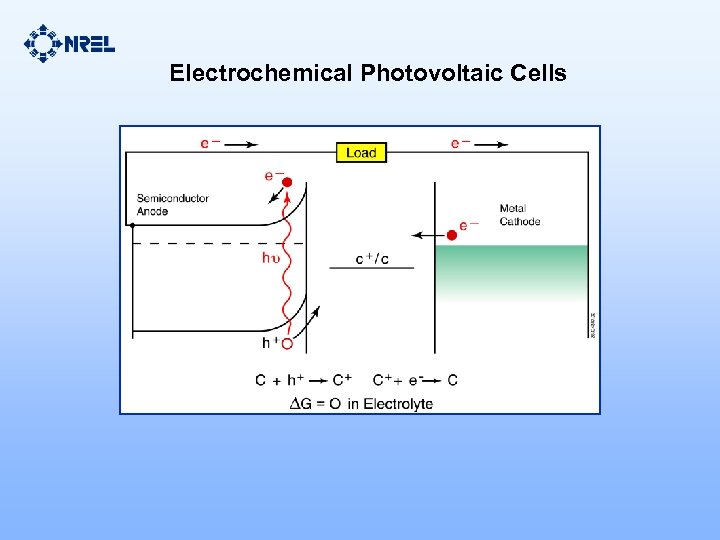

Electrochemical Photovoltaic Cells

Electrochemical Photovoltaic Cells

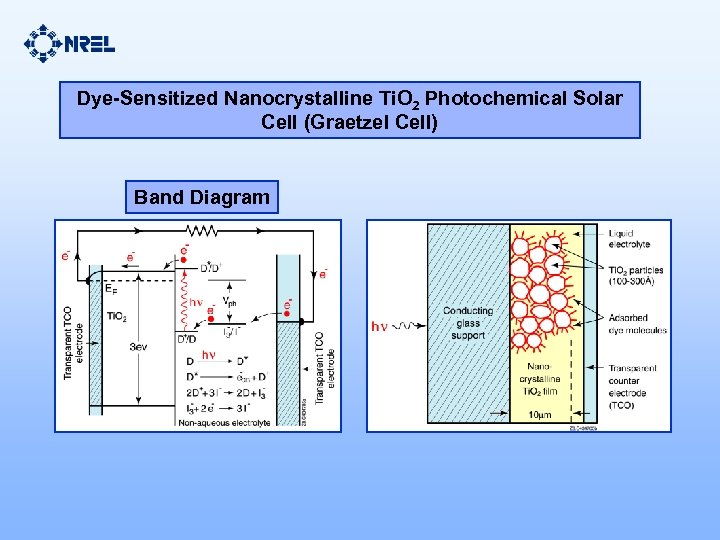

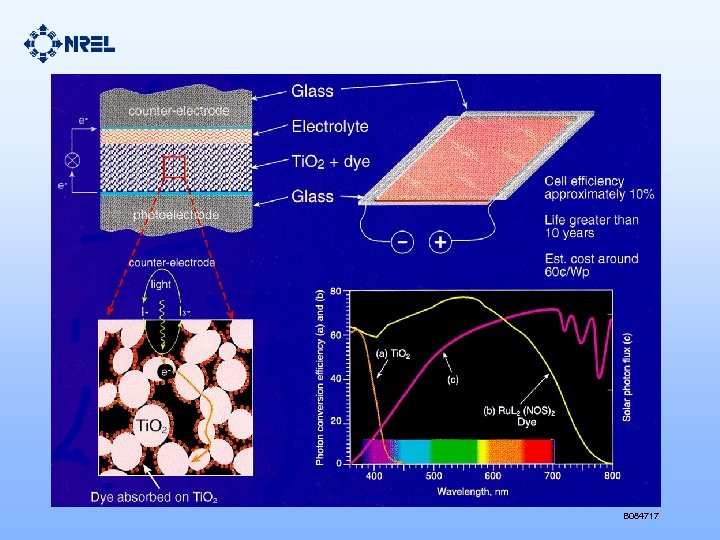

Dye-Sensitized Nanocrystalline Ti. O 2 Photochemical Solar Cell (Graetzel Cell) Band Diagram

Dye-Sensitized Nanocrystalline Ti. O 2 Photochemical Solar Cell (Graetzel Cell) Band Diagram

B 084717

B 084717

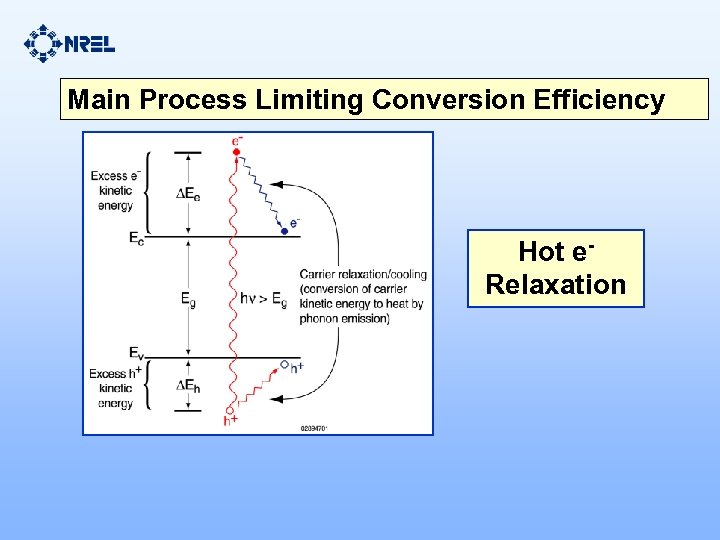

Main Process Limiting Conversion Efficiency Hot e. Relaxation

Main Process Limiting Conversion Efficiency Hot e. Relaxation

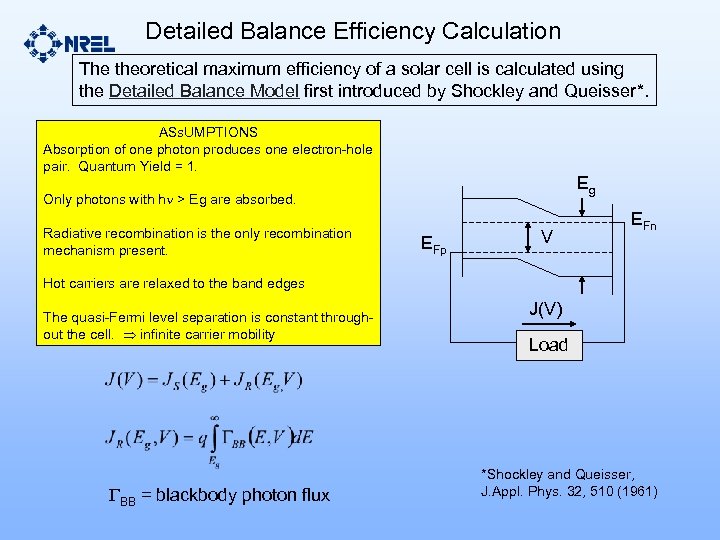

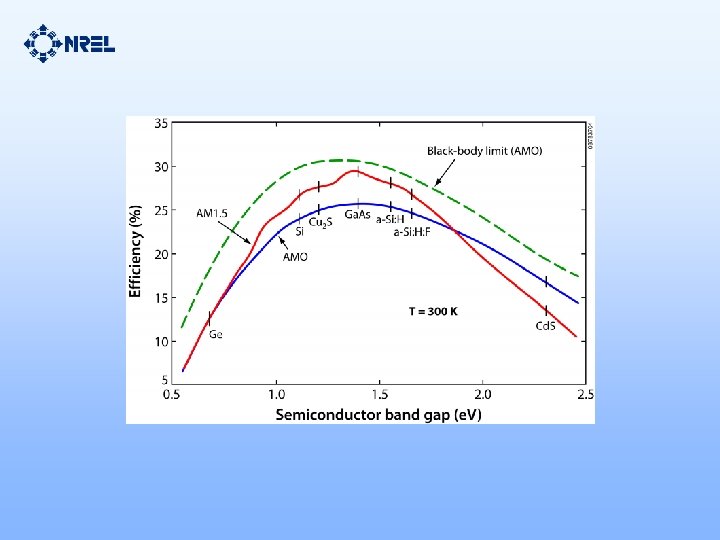

Detailed Balance Efficiency Calculation The theoretical maximum efficiency of a solar cell is calculated using the Detailed Balance Model first introduced by Shockley and Queisser*. ASs. UMPTIONS Absorption of one photon produces one electron-hole pair. Quantum Yield = 1. Eg Only photons with h > Eg are absorbed. Radiative recombination is the only recombination mechanism present. EFp V EFn Hot carriers are relaxed to the band edges The quasi-Fermi level separation is constant throughout the cell. infinite carrier mobility BB = blackbody photon flux J(V) Load *Shockley and Queisser, J. Appl. Phys. 32, 510 (1961)

Detailed Balance Efficiency Calculation The theoretical maximum efficiency of a solar cell is calculated using the Detailed Balance Model first introduced by Shockley and Queisser*. ASs. UMPTIONS Absorption of one photon produces one electron-hole pair. Quantum Yield = 1. Eg Only photons with h > Eg are absorbed. Radiative recombination is the only recombination mechanism present. EFp V EFn Hot carriers are relaxed to the band edges The quasi-Fermi level separation is constant throughout the cell. infinite carrier mobility BB = blackbody photon flux J(V) Load *Shockley and Queisser, J. Appl. Phys. 32, 510 (1961)

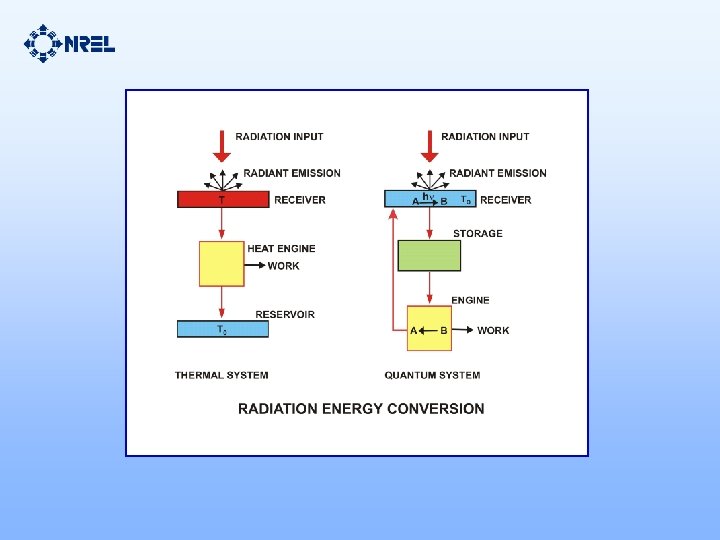

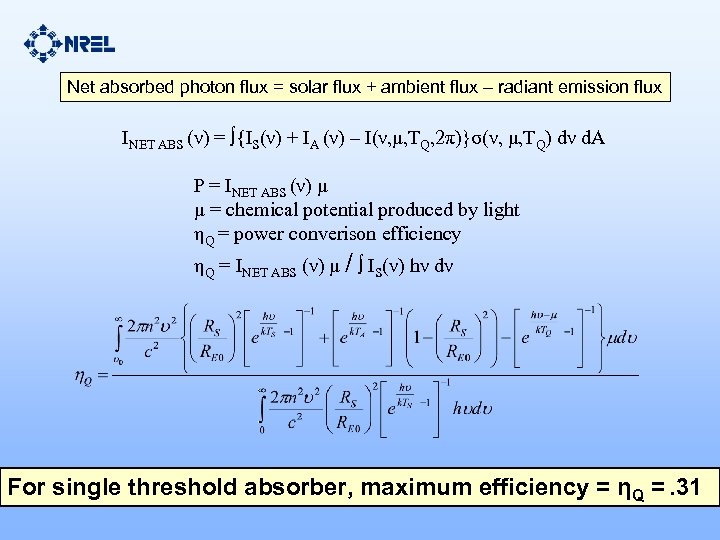

Net absorbed photon flux = solar flux + ambient flux – radiant emission flux INET ABS (ν) = ∫{IS(ν) + IA (ν) – I(ν, μ, TQ, 2π)}σ(ν, μ, TQ) dν d. A P = INET ABS (ν) μ μ = chemical potential produced by light ηQ = power converison efficiency ηQ = INET ABS (ν) μ / ∫ IS(ν) hν dν For single threshold absorber, maximum efficiency = ηQ =. 31

Net absorbed photon flux = solar flux + ambient flux – radiant emission flux INET ABS (ν) = ∫{IS(ν) + IA (ν) – I(ν, μ, TQ, 2π)}σ(ν, μ, TQ) dν d. A P = INET ABS (ν) μ μ = chemical potential produced by light ηQ = power converison efficiency ηQ = INET ABS (ν) μ / ∫ IS(ν) hν dν For single threshold absorber, maximum efficiency = ηQ =. 31

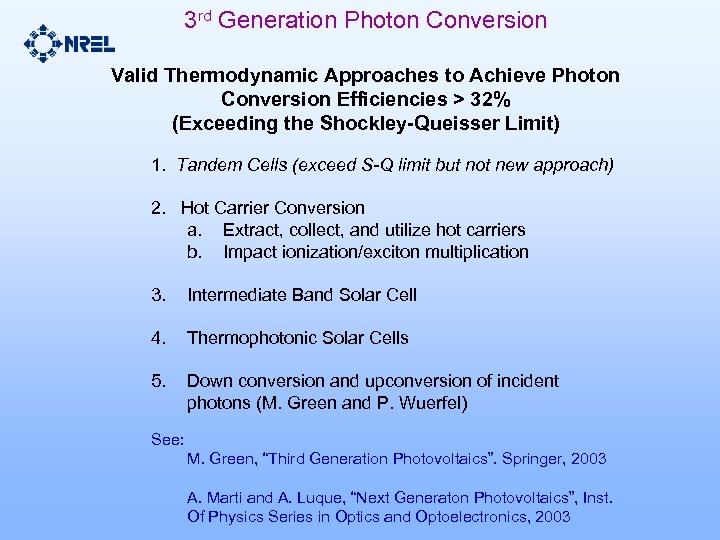

3 rd Generation Photon Conversion Valid Thermodynamic Approaches to Achieve Photon Conversion Efficiencies > 32% (Exceeding the Shockley-Queisser Limit) 1. Tandem Cells (exceed S-Q limit but not new approach) 2. Hot Carrier Conversion a. Extract, collect, and utilize hot carriers b. Impact ionization/exciton multiplication 3. Intermediate Band Solar Cell 4. Thermophotonic Solar Cells 5. Down conversion and upconversion of incident photons (M. Green and P. Wuerfel) See: M. Green, “Third Generation Photovoltaics”. Springer, 2003 A. Marti and A. Luque, “Next Generaton Photovoltaics”, Inst. Of Physics Series in Optics and Optoelectronics, 2003

3 rd Generation Photon Conversion Valid Thermodynamic Approaches to Achieve Photon Conversion Efficiencies > 32% (Exceeding the Shockley-Queisser Limit) 1. Tandem Cells (exceed S-Q limit but not new approach) 2. Hot Carrier Conversion a. Extract, collect, and utilize hot carriers b. Impact ionization/exciton multiplication 3. Intermediate Band Solar Cell 4. Thermophotonic Solar Cells 5. Down conversion and upconversion of incident photons (M. Green and P. Wuerfel) See: M. Green, “Third Generation Photovoltaics”. Springer, 2003 A. Marti and A. Luque, “Next Generaton Photovoltaics”, Inst. Of Physics Series in Optics and Optoelectronics, 2003

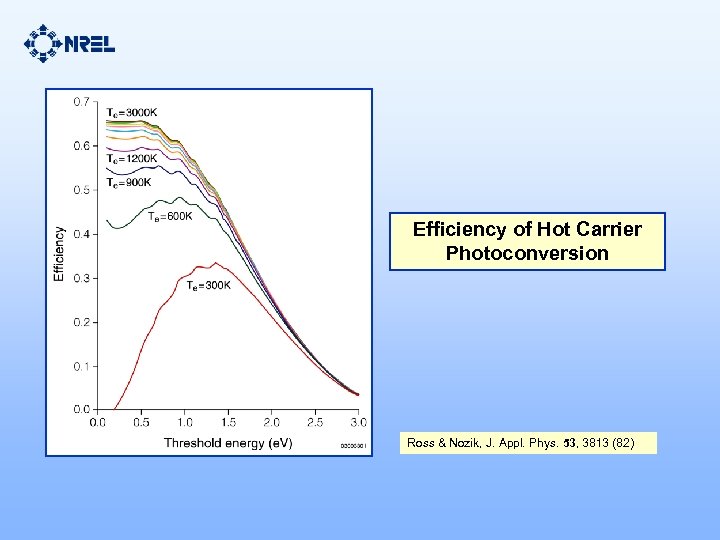

Efficiency of Hot Carrier Photoconversion Ross & Nozik, J. Appl. Phys. 53, 3813 (82)

Efficiency of Hot Carrier Photoconversion Ross & Nozik, J. Appl. Phys. 53, 3813 (82)

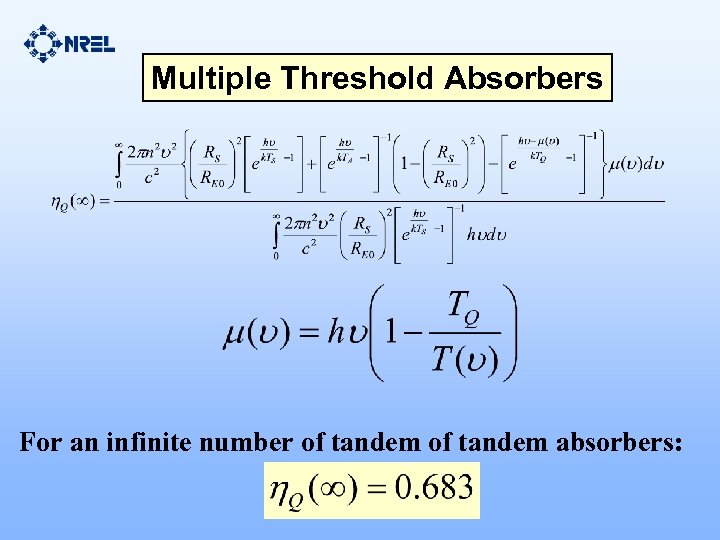

Multiple Threshold Absorbers For an infinite number of tandem absorbers:

Multiple Threshold Absorbers For an infinite number of tandem absorbers:

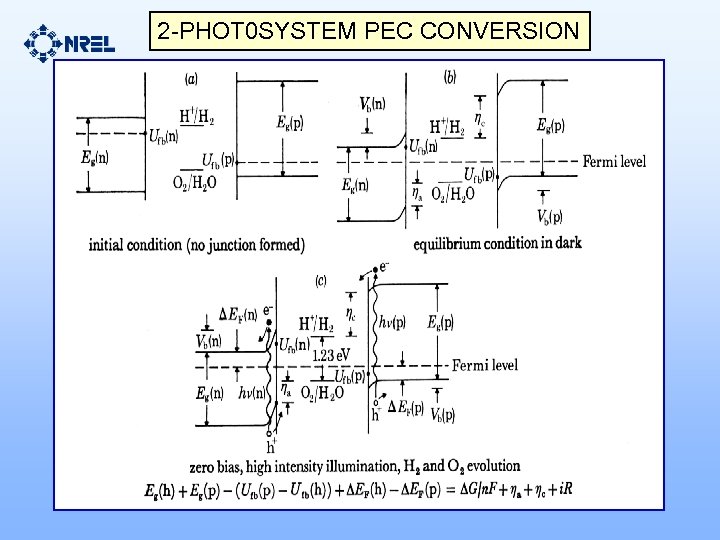

2 -PHOT 0 SYSTEM PEC CONVERSION

2 -PHOT 0 SYSTEM PEC CONVERSION

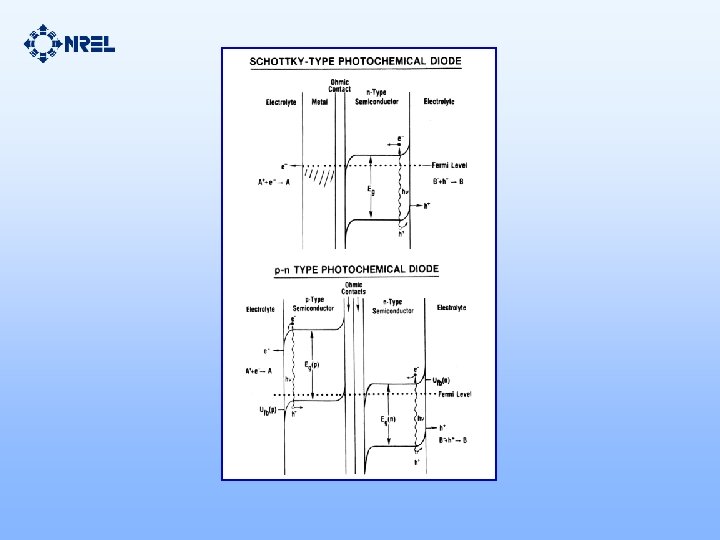

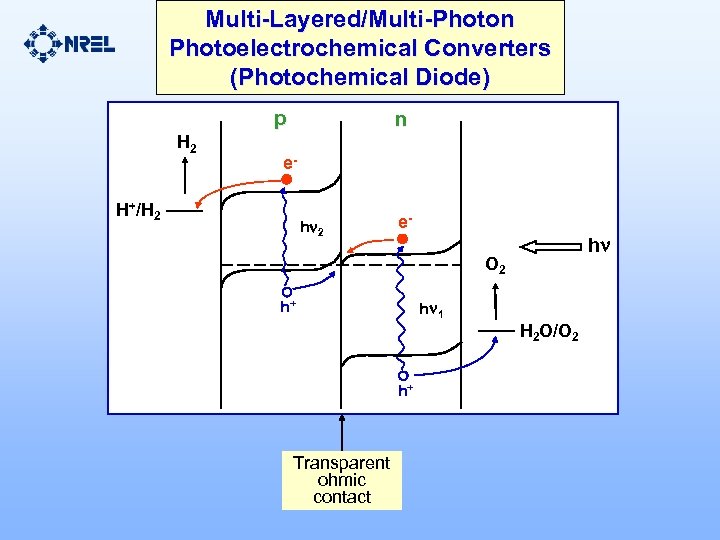

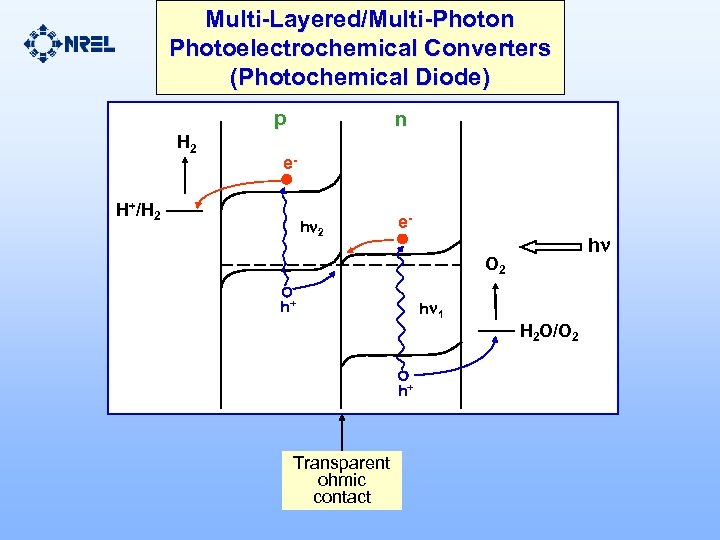

Multi-Layered/Multi-Photon Photoelectrochemical Converters (Photochemical Diode) p H 2 n e- H+/H 2 h 2 e- h O 2 h+ h 1 H 2 O/O 2 h+ Transparent ohmic contact

Multi-Layered/Multi-Photon Photoelectrochemical Converters (Photochemical Diode) p H 2 n e- H+/H 2 h 2 e- h O 2 h+ h 1 H 2 O/O 2 h+ Transparent ohmic contact

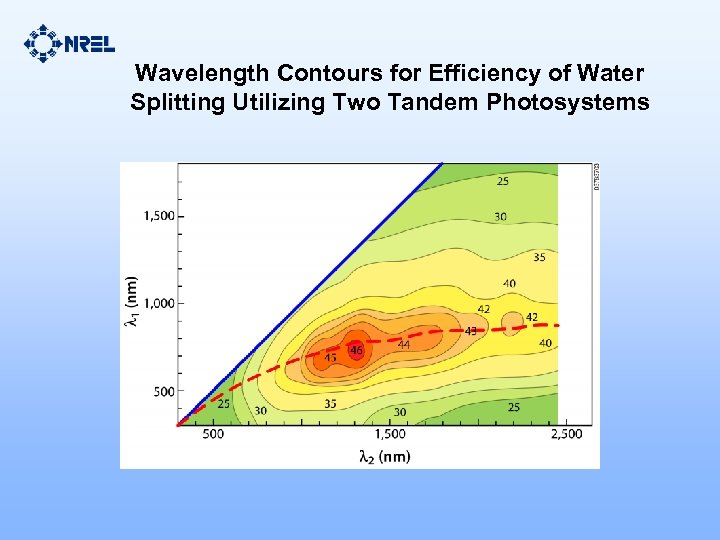

Wavelength Contours for Efficiency of Water Splitting Utilizing Two Tandem Photosystems

Wavelength Contours for Efficiency of Water Splitting Utilizing Two Tandem Photosystems

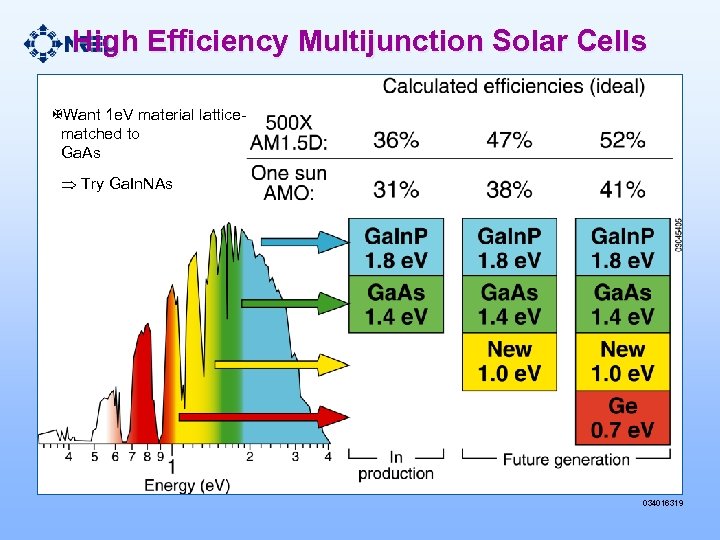

High Efficiency Multijunction Solar Cells XWant 1 e. V material latticematched to Ga. As Try Ga. In. NAs 034016319

High Efficiency Multijunction Solar Cells XWant 1 e. V material latticematched to Ga. As Try Ga. In. NAs 034016319

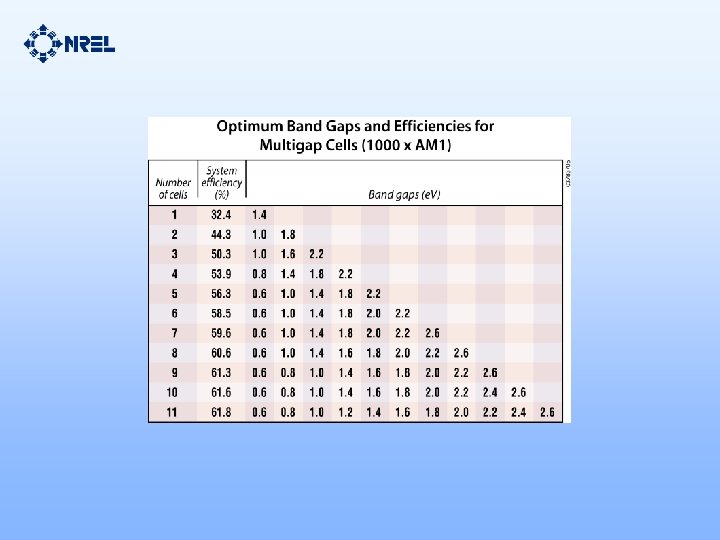

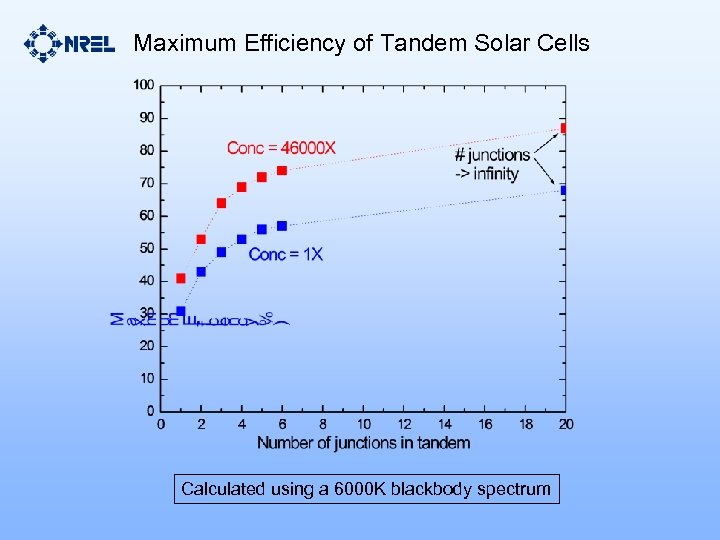

Maximum Efficiency of Tandem Solar Cells Calculated using a 6000 K blackbody spectrum

Maximum Efficiency of Tandem Solar Cells Calculated using a 6000 K blackbody spectrum

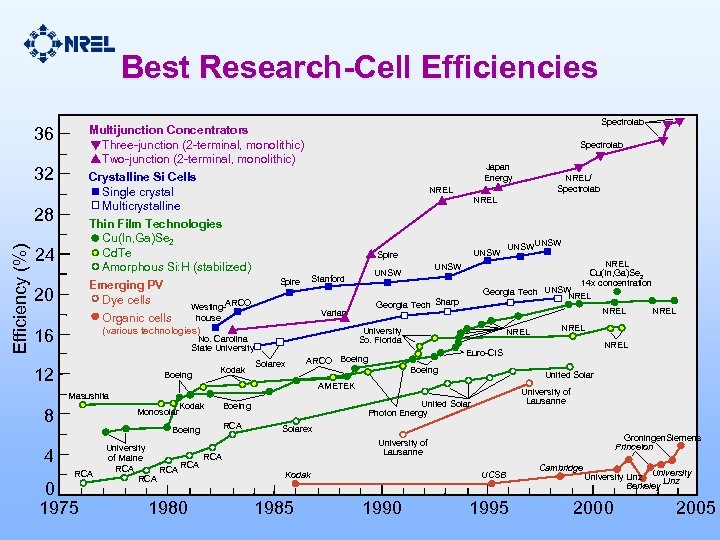

Best Research-Cell Efficiencies 36 32 28 Efficiency (%) Spectrolab Multijunction Concentrators Three-junction (2 -terminal, monolithic) Two-junction (2 -terminal, monolithic) Crystalline Si Cells Single crystal Multicrystalline Thin Film Technologies Cu(In, Ga)Se 2 Cd. Te Amorphous Si: H (stabilized) 24 Japan Energy NREL Stanford Westing-ARCO house Organic cells (various technologies) 16 12 Boeing Monosolar Kodak Boeing 4 RCA 0 1975 Solarex NREL ARCO Boeing University RCA of Maine RCA RCA 1980 RCA NREL United Solar University of Lausanne United Solar Photon Energy Boeing Solarex Groningen. Siemens Princeton University of Lausanne UCSB Kodak 1985 1990 NREL Euro-CIS AMETEK Masushita 8 Kodak NREL University So. Florida No. Carolina State University UNSW NREL Cu(In, Ga)Se 2 14 x concentration Georgia Tech UNSW NREL UNSW Georgia Tech Sharp Varian UNSW NREL/ Spectrolab NREL Spire Emerging PV Dye cells 20 Spectrolab 1995 Cambridge University Linz Berkeley 2000 2005

Best Research-Cell Efficiencies 36 32 28 Efficiency (%) Spectrolab Multijunction Concentrators Three-junction (2 -terminal, monolithic) Two-junction (2 -terminal, monolithic) Crystalline Si Cells Single crystal Multicrystalline Thin Film Technologies Cu(In, Ga)Se 2 Cd. Te Amorphous Si: H (stabilized) 24 Japan Energy NREL Stanford Westing-ARCO house Organic cells (various technologies) 16 12 Boeing Monosolar Kodak Boeing 4 RCA 0 1975 Solarex NREL ARCO Boeing University RCA of Maine RCA RCA 1980 RCA NREL United Solar University of Lausanne United Solar Photon Energy Boeing Solarex Groningen. Siemens Princeton University of Lausanne UCSB Kodak 1985 1990 NREL Euro-CIS AMETEK Masushita 8 Kodak NREL University So. Florida No. Carolina State University UNSW NREL Cu(In, Ga)Se 2 14 x concentration Georgia Tech UNSW NREL UNSW Georgia Tech Sharp Varian UNSW NREL/ Spectrolab NREL Spire Emerging PV Dye cells 20 Spectrolab 1995 Cambridge University Linz Berkeley 2000 2005

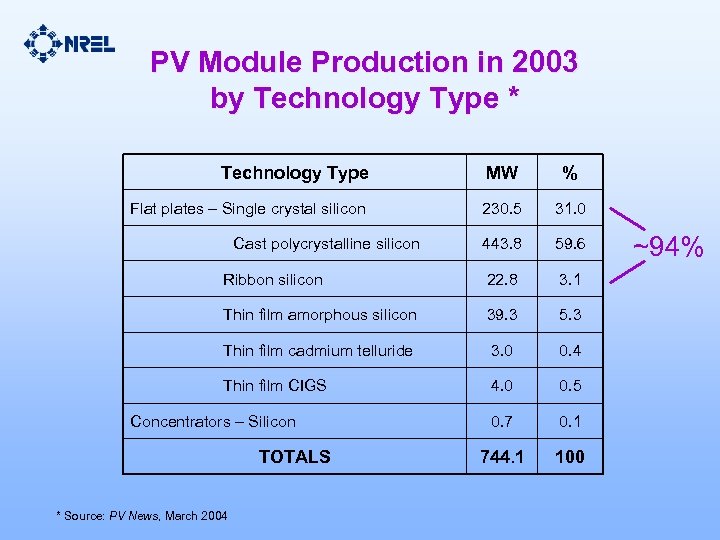

PV Module Production in 2003 by Technology Type * Technology Type MW % Flat plates – Single crystal silicon 230. 5 31. 0 443. 8 59. 6 Ribbon silicon 22. 8 3. 1 Thin film amorphous silicon 39. 3 5. 3 Thin film cadmium telluride 3. 0 0. 4 Thin film CIGS 4. 0 0. 5 0. 7 0. 1 744. 1 100 Cast polycrystalline silicon Concentrators – Silicon TOTALS * Source: PV News, March 2004 ~94%

PV Module Production in 2003 by Technology Type * Technology Type MW % Flat plates – Single crystal silicon 230. 5 31. 0 443. 8 59. 6 Ribbon silicon 22. 8 3. 1 Thin film amorphous silicon 39. 3 5. 3 Thin film cadmium telluride 3. 0 0. 4 Thin film CIGS 4. 0 0. 5 0. 7 0. 1 744. 1 100 Cast polycrystalline silicon Concentrators – Silicon TOTALS * Source: PV News, March 2004 ~94%

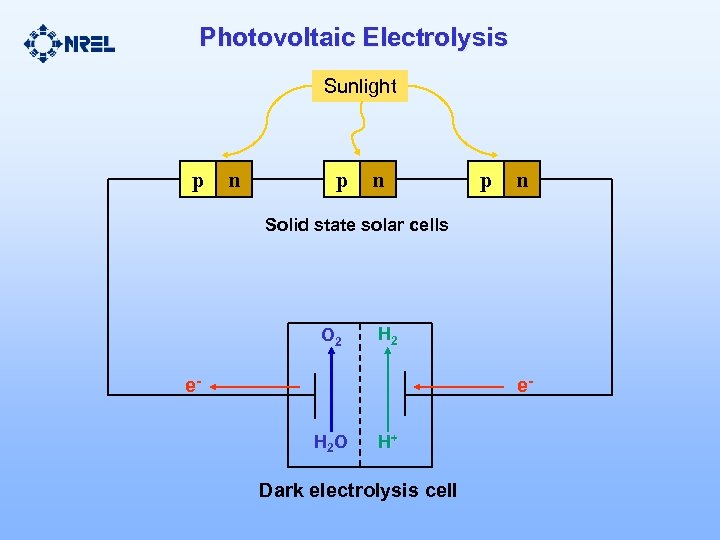

Photovoltaic Electrolysis Sunlight p n p n Solid state solar cells O 2 H 2 e- e. H 2 O H+ Dark electrolysis cell

Photovoltaic Electrolysis Sunlight p n p n Solid state solar cells O 2 H 2 e- e. H 2 O H+ Dark electrolysis cell

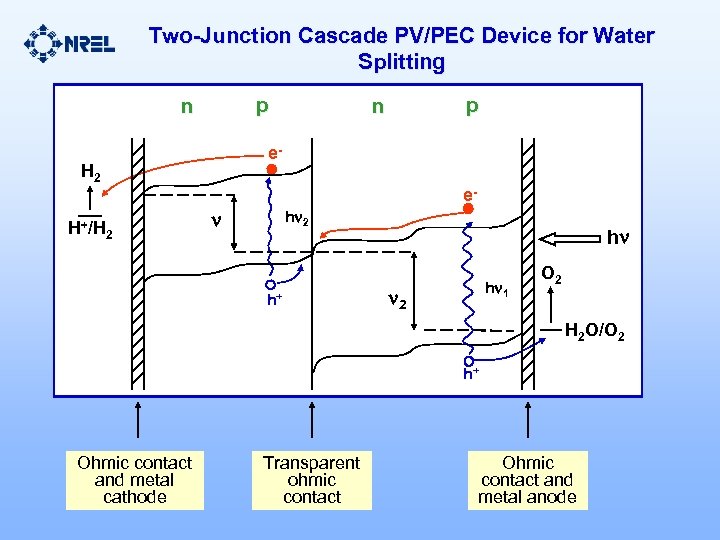

Two-Junction Cascade PV/PEC Device for Water Splitting p n e- H 2 e. H+/H 2 h+ h h 1 2 O 2 H 2 O/O 2 h+ Ohmic contact and metal cathode Transparent ohmic contact Ohmic contact and metal anode

Two-Junction Cascade PV/PEC Device for Water Splitting p n e- H 2 e. H+/H 2 h+ h h 1 2 O 2 H 2 O/O 2 h+ Ohmic contact and metal cathode Transparent ohmic contact Ohmic contact and metal anode

Multi-Layered/Multi-Photon Photoelectrochemical Converters (Photochemical Diode) p H 2 n e- H+/H 2 h 2 e- h O 2 h+ h 1 H 2 O/O 2 h+ Transparent ohmic contact

Multi-Layered/Multi-Photon Photoelectrochemical Converters (Photochemical Diode) p H 2 n e- H+/H 2 h 2 e- h O 2 h+ h 1 H 2 O/O 2 h+ Transparent ohmic contact

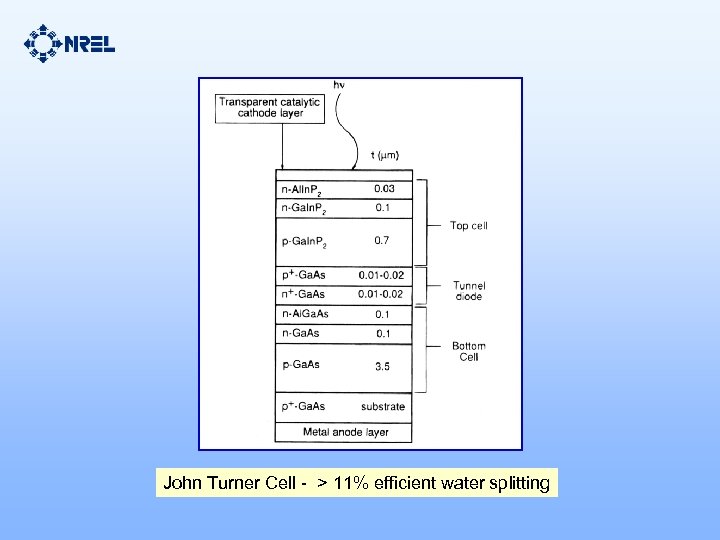

John Turner Cell - > 11% efficient water splitting

John Turner Cell - > 11% efficient water splitting

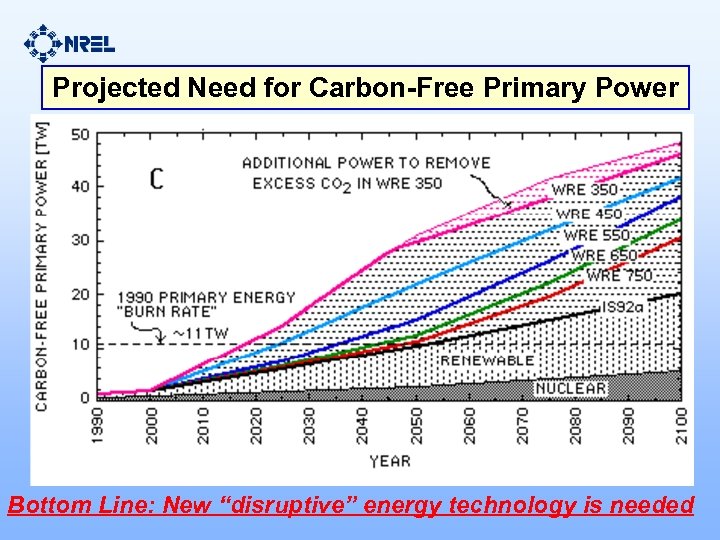

Projected Need for Carbon-Free Primary Power Bottom Line: New “disruptive” energy technology is needed

Projected Need for Carbon-Free Primary Power Bottom Line: New “disruptive” energy technology is needed

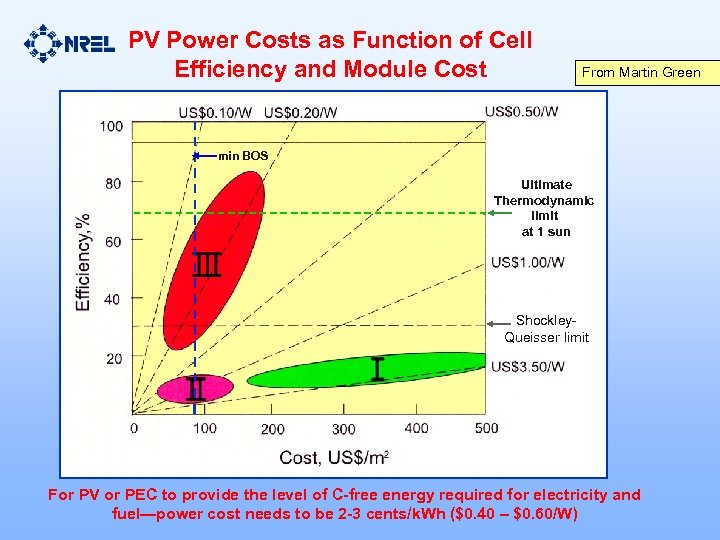

PV Power Costs as Function of Cell Efficiency and Module Cost From Martin Green min BOS Ultimate Thermodynamic limit at 1 sun Shockley. Queisser limit For PV or PEC to provide the level of C-free energy required for electricity and fuel—power cost needs to be 2 -3 cents/k. Wh ($0. 40 – $0. 60/W)

PV Power Costs as Function of Cell Efficiency and Module Cost From Martin Green min BOS Ultimate Thermodynamic limit at 1 sun Shockley. Queisser limit For PV or PEC to provide the level of C-free energy required for electricity and fuel—power cost needs to be 2 -3 cents/k. Wh ($0. 40 – $0. 60/W)

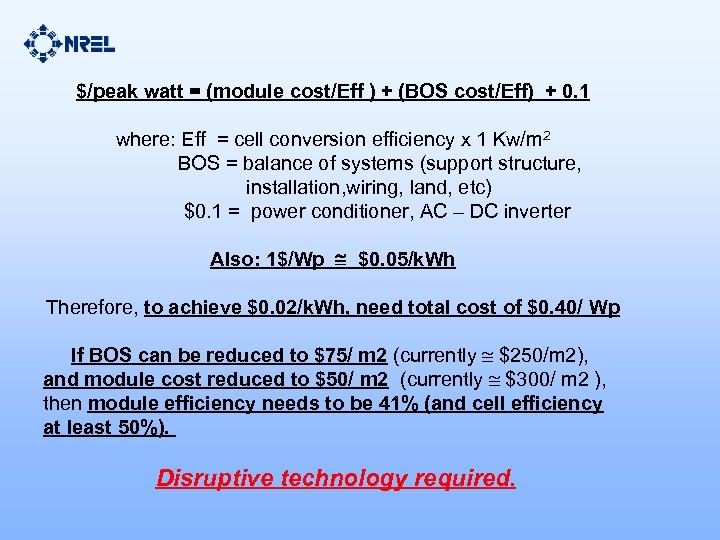

$/peak watt = (module cost/Eff ) + (BOS cost/Eff) + 0. 1 where: Eff = cell conversion efficiency x 1 Kw/m 2 BOS = balance of systems (support structure, installation, wiring, land, etc) $0. 1 = power conditioner, AC – DC inverter Also: 1$/Wp $0. 05/k. Wh Therefore, to achieve $0. 02/k. Wh, need total cost of $0. 40/ Wp If BOS can be reduced to $75/ m 2 (currently $250/m 2), and module cost reduced to $50/ m 2 (currently $300/ m 2 ), then module efficiency needs to be 41% (and cell efficiency at least 50%). Disruptive technology required.

$/peak watt = (module cost/Eff ) + (BOS cost/Eff) + 0. 1 where: Eff = cell conversion efficiency x 1 Kw/m 2 BOS = balance of systems (support structure, installation, wiring, land, etc) $0. 1 = power conditioner, AC – DC inverter Also: 1$/Wp $0. 05/k. Wh Therefore, to achieve $0. 02/k. Wh, need total cost of $0. 40/ Wp If BOS can be reduced to $75/ m 2 (currently $250/m 2), and module cost reduced to $50/ m 2 (currently $300/ m 2 ), then module efficiency needs to be 41% (and cell efficiency at least 50%). Disruptive technology required.

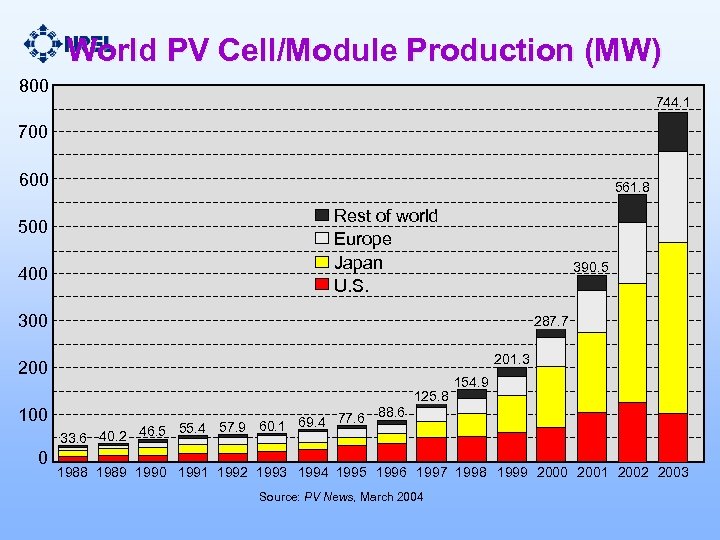

World PV Cell/Module Production (MW) 800 744. 1 700 600 500 400 561. 8 Rest of world Europe Japan U. S. 390. 5 300 287. 7 201. 3 200 125. 8 100 0 154. 9 77. 6 88. 6 57. 9 60. 1 69. 4 55. 4 33. 6 40. 2 46. 5 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Source: PV News, March 2004

World PV Cell/Module Production (MW) 800 744. 1 700 600 500 400 561. 8 Rest of world Europe Japan U. S. 390. 5 300 287. 7 201. 3 200 125. 8 100 0 154. 9 77. 6 88. 6 57. 9 60. 1 69. 4 55. 4 33. 6 40. 2 46. 5 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Source: PV News, March 2004

Two Ways to Utilize Photogenerated Hot e- for Useful Work and Increase Efficiency 1. Higher photovoltage via hot etransport, transfer, and conversion 2. Higher photocurrent via carrier multiplication through impact ionization (inverse Auger process)

Two Ways to Utilize Photogenerated Hot e- for Useful Work and Increase Efficiency 1. Higher photovoltage via hot etransport, transfer, and conversion 2. Higher photocurrent via carrier multiplication through impact ionization (inverse Auger process)

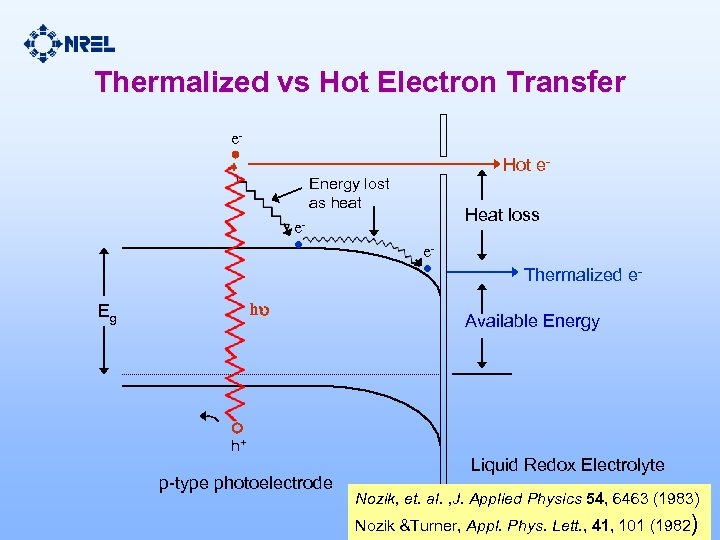

Thermalized vs Hot Electron Transfer e Hot e- Energy lost as heat Heat loss e e h Eg Thermalized e. Available Energy h+ p-type photoelectrode Liquid Redox Electrolyte Nozik, et. al. , J. Applied Physics 54, 6463 (1983) Nozik &Turner, Appl. Phys. Lett. , 41, 101 (1982)

Thermalized vs Hot Electron Transfer e Hot e- Energy lost as heat Heat loss e e h Eg Thermalized e. Available Energy h+ p-type photoelectrode Liquid Redox Electrolyte Nozik, et. al. , J. Applied Physics 54, 6463 (1983) Nozik &Turner, Appl. Phys. Lett. , 41, 101 (1982)

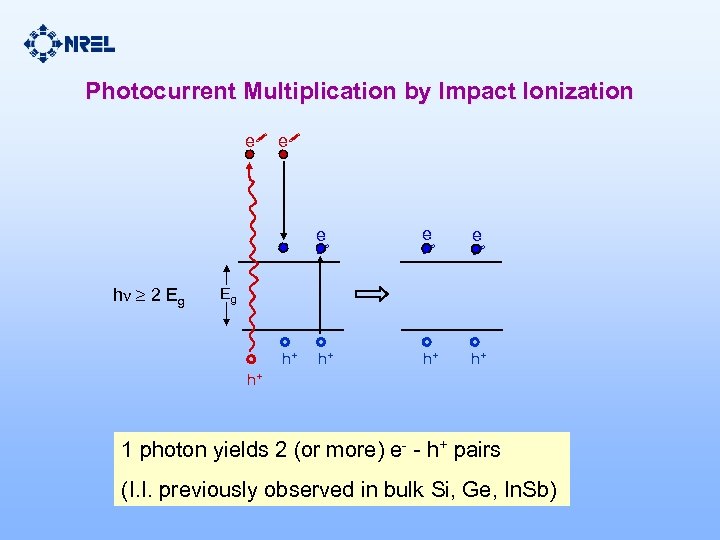

Photocurrent Multiplication by Impact Ionization e e e h+ h+ h+ hν 2 Eg h+ h+ 1 photon yields 2 (or more) e- - h+ pairs (I. I. previously observed in bulk Si, Ge, In. Sb)

Photocurrent Multiplication by Impact Ionization e e e h+ h+ h+ hν 2 Eg h+ h+ 1 photon yields 2 (or more) e- - h+ pairs (I. I. previously observed in bulk Si, Ge, In. Sb)

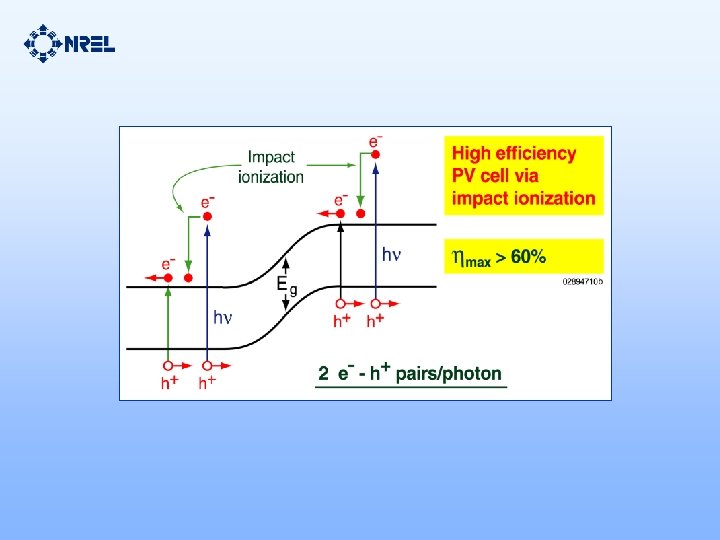

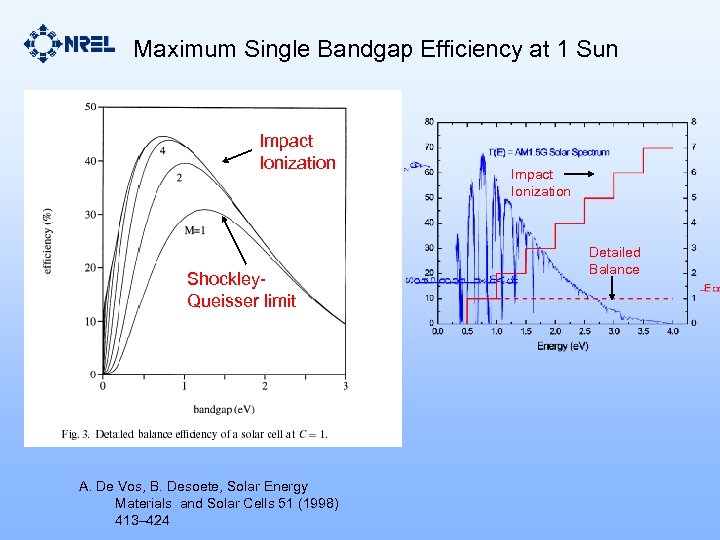

Maximum Single Bandgap Efficiency at 1 Sun Impact Ionization Shockley. Queisser limit A. De Vos, B. Desoete, Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 51 (1998) 413– 424 Impact Ionization Detailed Balance

Maximum Single Bandgap Efficiency at 1 Sun Impact Ionization Shockley. Queisser limit A. De Vos, B. Desoete, Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 51 (1998) 413– 424 Impact Ionization Detailed Balance

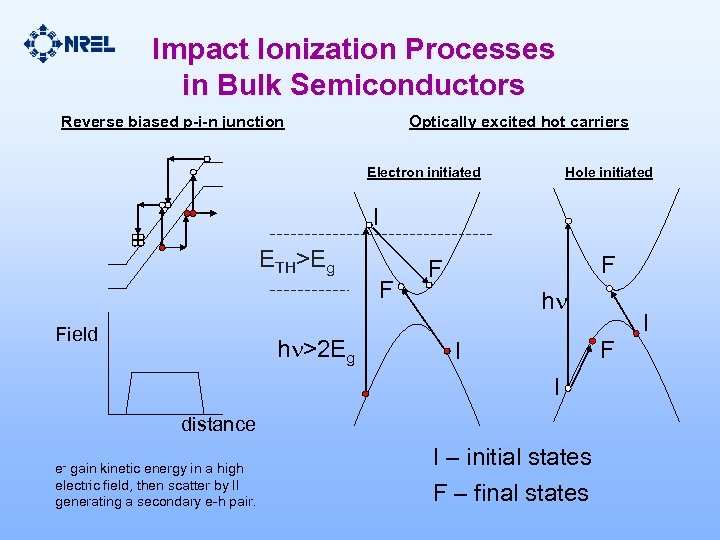

Impact Ionization Processes in Bulk Semiconductors Reverse biased p-i-n junction Optically excited hot carriers Electron initiated Hole initiated I ETH>Eg F Field h >2 Eg F F h F I I distance e- gain kinetic energy in a high electric field, then scatter by II generating a secondary e-h pair. I – initial states F – final states I

Impact Ionization Processes in Bulk Semiconductors Reverse biased p-i-n junction Optically excited hot carriers Electron initiated Hole initiated I ETH>Eg F Field h >2 Eg F F h F I I distance e- gain kinetic energy in a high electric field, then scatter by II generating a secondary e-h pair. I – initial states F – final states I

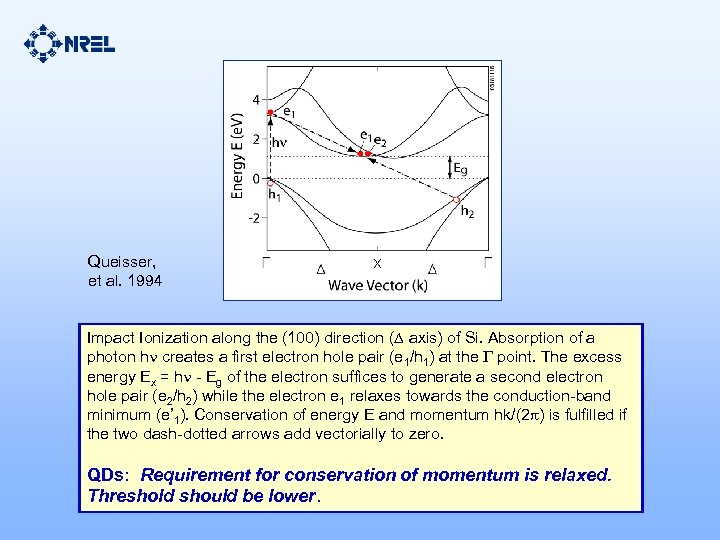

Queisser, et al. 1994 Impact Ionization along the (100) direction ( axis) of Si. Absorption of a photon h creates a first electron hole pair (e 1/h 1) at the point. The excess energy Ex = h - Eg of the electron suffices to generate a second electron hole pair (e 2/h 2) while the electron e 1 relaxes towards the conduction-band minimum (e’ 1). Conservation of energy E and momentum hk/(2 ) is fulfilled if the two dash-dotted arrows add vectorially to zero. QDs: Requirement for conservation of momentum is relaxed. Threshold should be lower.

Queisser, et al. 1994 Impact Ionization along the (100) direction ( axis) of Si. Absorption of a photon h creates a first electron hole pair (e 1/h 1) at the point. The excess energy Ex = h - Eg of the electron suffices to generate a second electron hole pair (e 2/h 2) while the electron e 1 relaxes towards the conduction-band minimum (e’ 1). Conservation of energy E and momentum hk/(2 ) is fulfilled if the two dash-dotted arrows add vectorially to zero. QDs: Requirement for conservation of momentum is relaxed. Threshold should be lower.

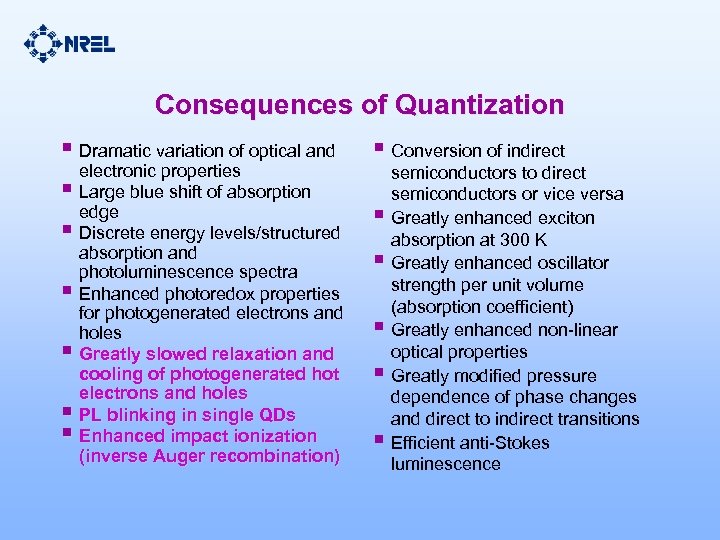

Consequences of Quantization § Dramatic variation of optical and § Conversion of indirect electronic properties semiconductors to direct § Large blue shift of absorption semiconductors or vice versa edge § Greatly enhanced exciton § Discrete energy levels/structured absorption at 300 K absorption and § Greatly enhanced oscillator photoluminescence spectra strength per unit volume § Enhanced photoredox properties (absorption coefficient) for photogenerated electrons and § Greatly enhanced non-linear holes optical properties § Greatly slowed relaxation and cooling of photogenerated hot § Greatly modified pressure electrons and holes dependence of phase changes § PL blinking in single QDs and direct to indirect transitions § Enhanced impact ionization § Efficient anti-Stokes (inverse Auger recombination) luminescence

Consequences of Quantization § Dramatic variation of optical and § Conversion of indirect electronic properties semiconductors to direct § Large blue shift of absorption semiconductors or vice versa edge § Greatly enhanced exciton § Discrete energy levels/structured absorption at 300 K absorption and § Greatly enhanced oscillator photoluminescence spectra strength per unit volume § Enhanced photoredox properties (absorption coefficient) for photogenerated electrons and § Greatly enhanced non-linear holes optical properties § Greatly slowed relaxation and cooling of photogenerated hot § Greatly modified pressure electrons and holes dependence of phase changes § PL blinking in single QDs and direct to indirect transitions § Enhanced impact ionization § Efficient anti-Stokes (inverse Auger recombination) luminescence

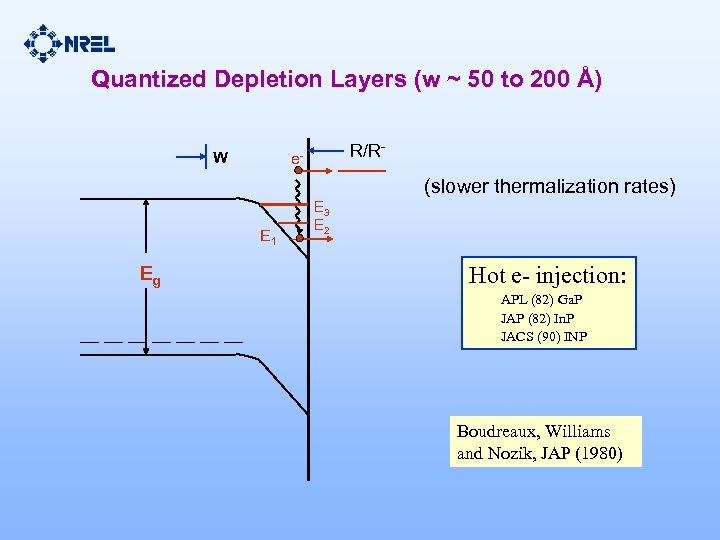

Quantized Depletion Layers (w ~ 50 to 200 Å) W R/R- e- (slower thermalization rates) E 1 Eg E 3 E 2 Hot e- injection: APL (82) Ga. P JAP (82) In. P JACS (90) INP Boudreaux, Williams and Nozik, JAP (1980)

Quantized Depletion Layers (w ~ 50 to 200 Å) W R/R- e- (slower thermalization rates) E 1 Eg E 3 E 2 Hot e- injection: APL (82) Ga. P JAP (82) In. P JACS (90) INP Boudreaux, Williams and Nozik, JAP (1980)

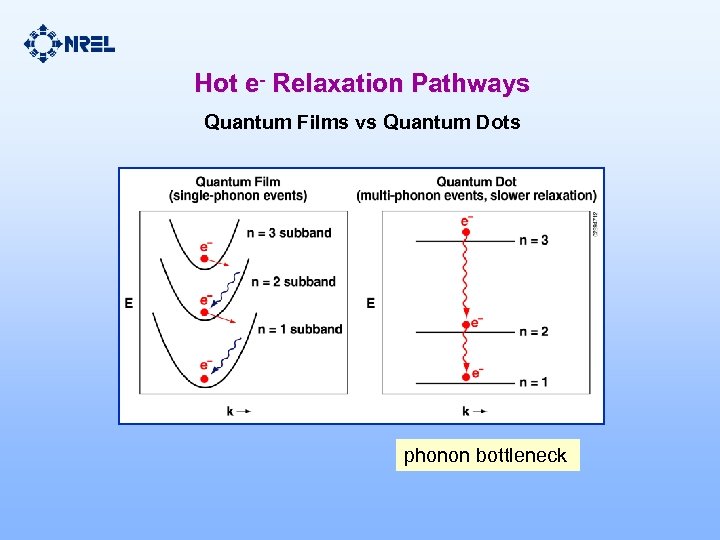

Hot e- Relaxation Pathways Quantum Films vs Quantum Dots phonon bottleneck

Hot e- Relaxation Pathways Quantum Films vs Quantum Dots phonon bottleneck

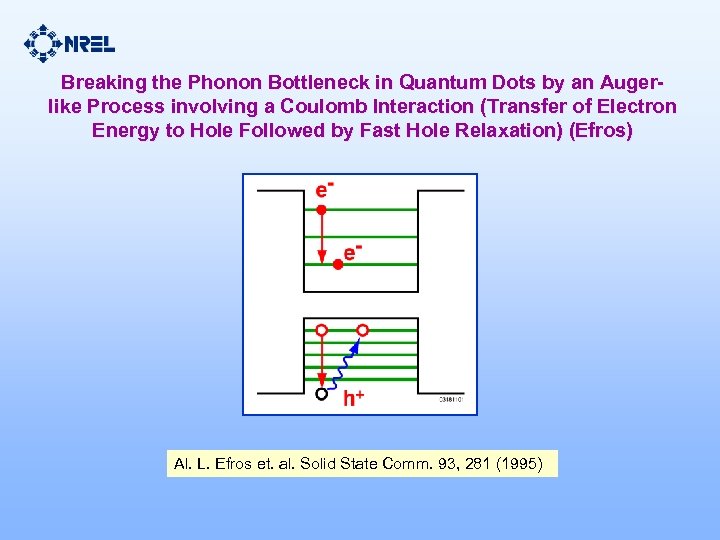

Breaking the Phonon Bottleneck in Quantum Dots by an Augerlike Process involving a Coulomb Interaction (Transfer of Electron Energy to Hole Followed by Fast Hole Relaxation) (Efros) Al. L. Efros et. al. Solid State Comm. 93, 281 (1995)

Breaking the Phonon Bottleneck in Quantum Dots by an Augerlike Process involving a Coulomb Interaction (Transfer of Electron Energy to Hole Followed by Fast Hole Relaxation) (Efros) Al. L. Efros et. al. Solid State Comm. 93, 281 (1995)

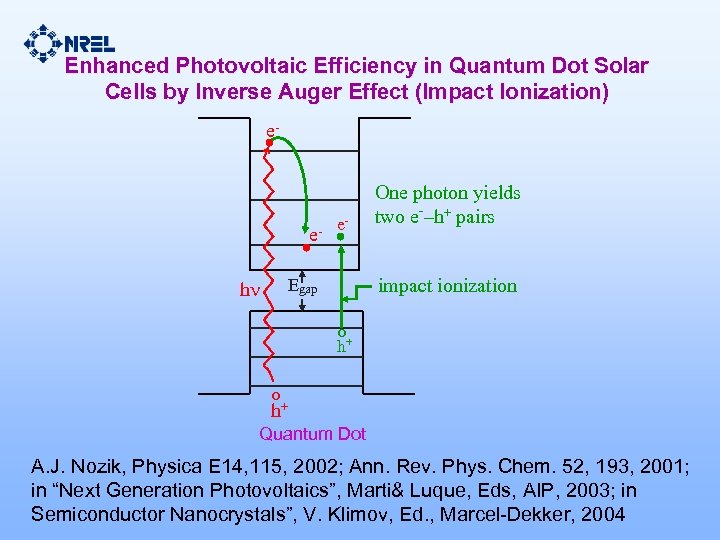

Enhanced Photovoltaic Efficiency in Quantum Dot Solar Cells by Inverse Auger Effect (Impact Ionization) e e- e impact ionization Egap h One photon yields two e-–h+ pairs O h+ Quantum Dot A. J. Nozik, Physica E 14, 115, 2002; Ann. Rev. Phys. Chem. 52, 193, 2001; in “Next Generation Photovoltaics”, Marti& Luque, Eds, AIP, 2003; in Semiconductor Nanocrystals”, V. Klimov, Ed. , Marcel-Dekker, 2004

Enhanced Photovoltaic Efficiency in Quantum Dot Solar Cells by Inverse Auger Effect (Impact Ionization) e e- e impact ionization Egap h One photon yields two e-–h+ pairs O h+ Quantum Dot A. J. Nozik, Physica E 14, 115, 2002; Ann. Rev. Phys. Chem. 52, 193, 2001; in “Next Generation Photovoltaics”, Marti& Luque, Eds, AIP, 2003; in Semiconductor Nanocrystals”, V. Klimov, Ed. , Marcel-Dekker, 2004

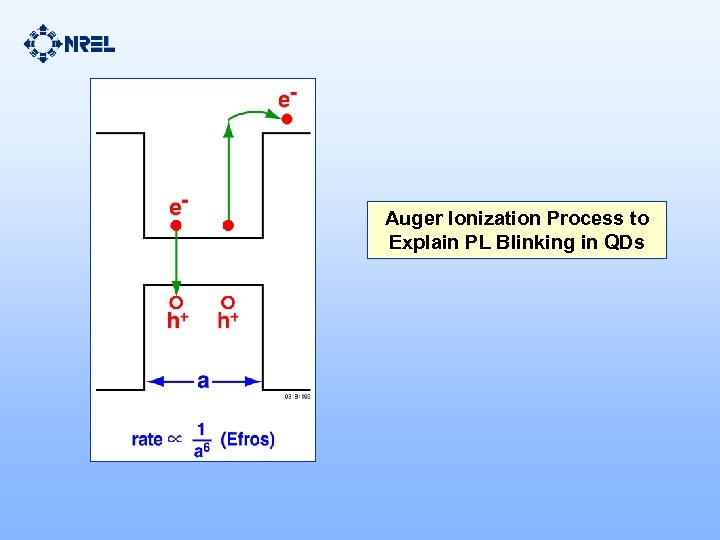

Auger Ionization Process to Explain PL Blinking in QDs

Auger Ionization Process to Explain PL Blinking in QDs

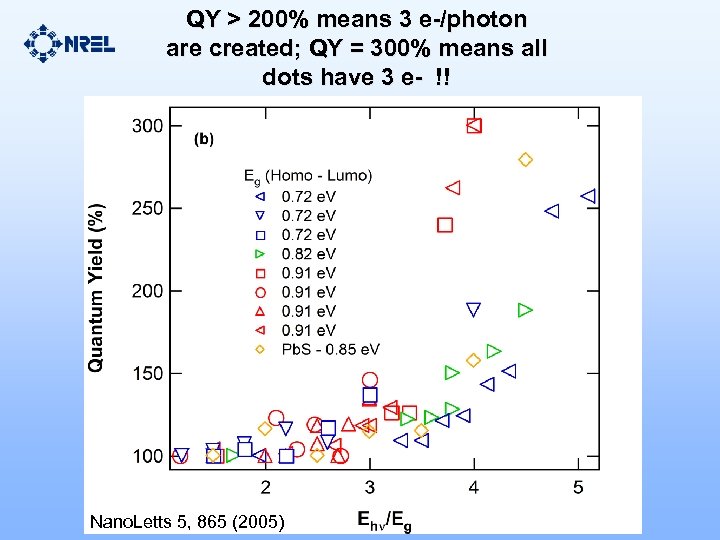

Experimental Verification of Greatly Enhanced Impact Ionization in Quantum Dots ● R. D. Schaller and V. I. Klimov, Phys. Rev. Letts, 92, 186601 (May), 2004 (Pb. Se QDs) ● R. J. Ellingson, M. Beard, P. Yu, A. J. Nozik, Nano. Letters 5, 865, 2005 (Pb. Se and Pb. S QDs; 300% QY in Pb. Se QDs at 4 times Eg)

Experimental Verification of Greatly Enhanced Impact Ionization in Quantum Dots ● R. D. Schaller and V. I. Klimov, Phys. Rev. Letts, 92, 186601 (May), 2004 (Pb. Se QDs) ● R. J. Ellingson, M. Beard, P. Yu, A. J. Nozik, Nano. Letters 5, 865, 2005 (Pb. Se and Pb. S QDs; 300% QY in Pb. Se QDs at 4 times Eg)

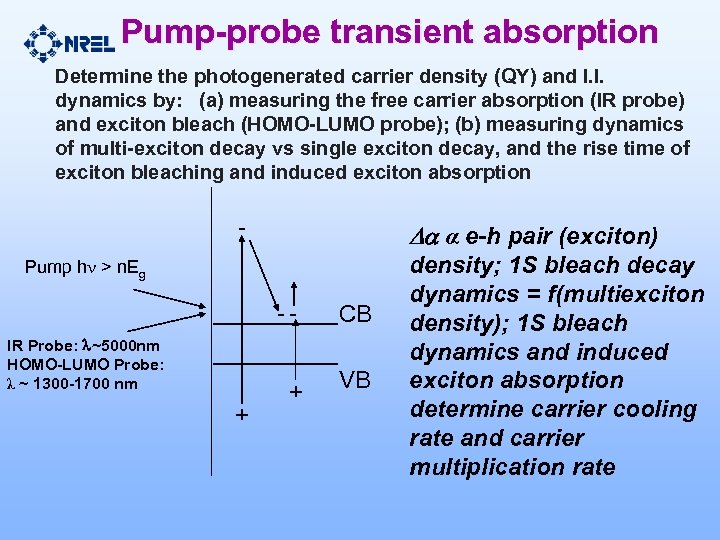

Pump-probe transient absorption Determine the photogenerated carrier density (QY) and I. I. dynamics by: (a) measuring the free carrier absorption (IR probe) and exciton bleach (HOMO-LUMO probe); (b) measuring dynamics of multi-exciton decay vs single exciton decay, and the rise time of exciton bleaching and induced exciton absorption - Da α e-h pair (exciton) Pump h > n. Eg -IR Probe: l~5000 nm HOMO-LUMO Probe: λ ~ 1300 -1700 nm + CB + VB density; 1 S bleach decay dynamics = f(multiexciton density); 1 S bleach dynamics and induced exciton absorption determine carrier cooling rate and carrier multiplication rate

Pump-probe transient absorption Determine the photogenerated carrier density (QY) and I. I. dynamics by: (a) measuring the free carrier absorption (IR probe) and exciton bleach (HOMO-LUMO probe); (b) measuring dynamics of multi-exciton decay vs single exciton decay, and the rise time of exciton bleaching and induced exciton absorption - Da α e-h pair (exciton) Pump h > n. Eg -IR Probe: l~5000 nm HOMO-LUMO Probe: λ ~ 1300 -1700 nm + CB + VB density; 1 S bleach decay dynamics = f(multiexciton density); 1 S bleach dynamics and induced exciton absorption determine carrier cooling rate and carrier multiplication rate

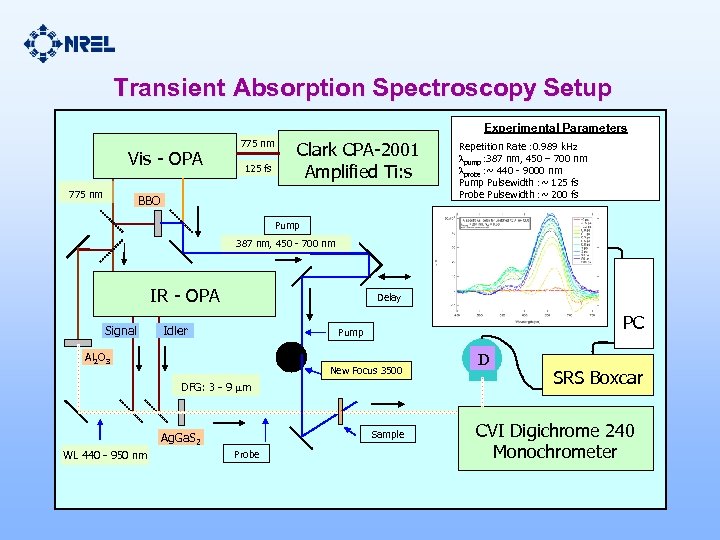

Transient Absorption Spectroscopy Setup Experimental Parameters Vis - OPA 775 nm 125 fs Clark CPA-2001 Amplified Ti: s BBO Repetition Rate : 0. 989 k. Hz pump : 387 nm, 450 – 700 nm probe : ~ 440 - 9000 nm Pump Pulsewidth : ~ 125 fs Probe Pulsewidth : ~ 200 fs Pump 387 nm, 450 - 700 nm IR - OPA Signal Delay Idler PC Pump Al 2 O 3 New Focus 3500 DFG: 3 - 9 m Sample Ag. Ga. S 2 WL 440 - 950 nm Probe D SRS Boxcar CVI Digichrome 240 Monochrometer

Transient Absorption Spectroscopy Setup Experimental Parameters Vis - OPA 775 nm 125 fs Clark CPA-2001 Amplified Ti: s BBO Repetition Rate : 0. 989 k. Hz pump : 387 nm, 450 – 700 nm probe : ~ 440 - 9000 nm Pump Pulsewidth : ~ 125 fs Probe Pulsewidth : ~ 200 fs Pump 387 nm, 450 - 700 nm IR - OPA Signal Delay Idler PC Pump Al 2 O 3 New Focus 3500 DFG: 3 - 9 m Sample Ag. Ga. S 2 WL 440 - 950 nm Probe D SRS Boxcar CVI Digichrome 240 Monochrometer

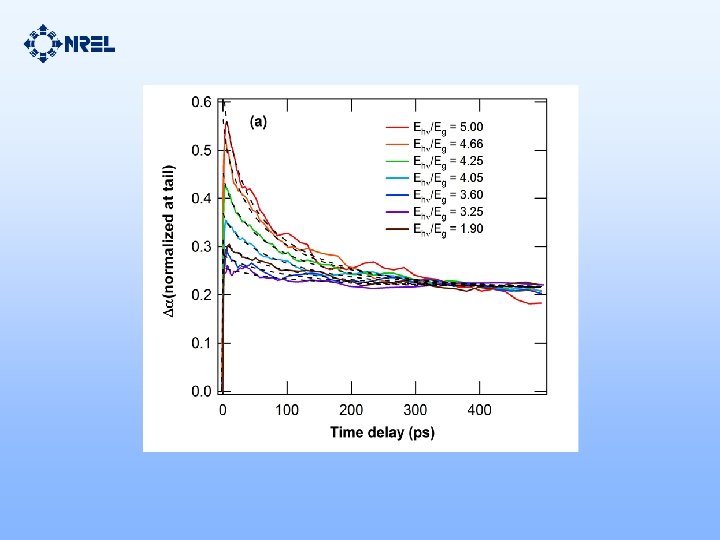

QY > 200% means 3 e-/photon are created; QY = 300% means all dots have 3 e- !! Nano. Letts 5, 865 (2005)

QY > 200% means 3 e-/photon are created; QY = 300% means all dots have 3 e- !! Nano. Letts 5, 865 (2005)

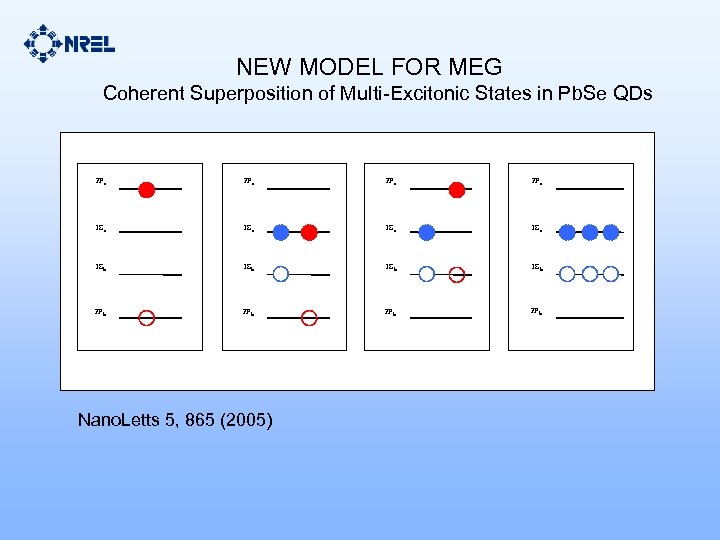

NEW MODEL FOR MEG Coherent Superposition of Multi-Excitonic States in Pb. Se QDs 2 Pe 2 Pe 1 Se 1 Se 1 Sh 1 Sh 2 Ph 2 Ph Nano. Letts 5, 865 (2005)

NEW MODEL FOR MEG Coherent Superposition of Multi-Excitonic States in Pb. Se QDs 2 Pe 2 Pe 1 Se 1 Se 1 Sh 1 Sh 2 Ph 2 Ph Nano. Letts 5, 865 (2005)

SUMMARY/CONCLUSIONS ● The ultimate thermodynamic efficiency for converting solar irradiance into chemical or electrical free energy is 32% for a single thereshold absorber, and 68% for a system that does not permit thermal degradation of the solar photons. With full solar concentration (46, 000 X) the latter efficiency is 86%. ● Ultra-high conversion efficiency (>50%) together with very low system cost (< $150/m 2) is required to produce solar power (fuels or electricity) at costs comparable to current fossil fuels cost (few cents/k. Wh), to avoid great economic and environmental disruption in the future. “Disruptive technology” is probably required.

SUMMARY/CONCLUSIONS ● The ultimate thermodynamic efficiency for converting solar irradiance into chemical or electrical free energy is 32% for a single thereshold absorber, and 68% for a system that does not permit thermal degradation of the solar photons. With full solar concentration (46, 000 X) the latter efficiency is 86%. ● Ultra-high conversion efficiency (>50%) together with very low system cost (< $150/m 2) is required to produce solar power (fuels or electricity) at costs comparable to current fossil fuels cost (few cents/k. Wh), to avoid great economic and environmental disruption in the future. “Disruptive technology” is probably required.

Summary/Conclusions ● Size quantization in semiconductors may greatly affect the relaxation dynamics of photoinduced carriers. These include: - slowed hot electron relaxation (partial phonon bottleneck) - enhanced impact ionization (inverse Auger process) ● The theoretical and measured energy threshold for impact ionization in bulk semiconductors (e. g. Si, In. As, Ga. As) is 4 -5 times the band gap. Much lower thresholds are predicted for QDs because of the relaxation of the need to conserve momentum. The rate of impact ionization is also expected to be much faster in QDs (Auger processes α 1/d 6 ) ● Very efficient exciton multiplication has been experimentally observed in Pb. Se and Pb. S QDs; the threshold photon energy is 2 Eg. Up to 3 electrons per photon (300% QY) have been observed at sufficiently high photon energies ( 4 Eg ). A new model based on coherent superposition of multiexcitonic states is introduced to explain these results. ● For QDs with m*e << m*h (In. P) slowed electron cooling (by about 1 order of magnitude) may be achieved by either fast hole trapping at the surface or by electron injection in the dark, which blocks hot electron cooling via the Auger process(results consistent with earlier results on Cd. Se QDs by Guyot-Sionnest and Klimov). If m*e ~ m*h (Pb. Se and Pb. S) phonon bottleneck and slowed cooling is apparent.

Summary/Conclusions ● Size quantization in semiconductors may greatly affect the relaxation dynamics of photoinduced carriers. These include: - slowed hot electron relaxation (partial phonon bottleneck) - enhanced impact ionization (inverse Auger process) ● The theoretical and measured energy threshold for impact ionization in bulk semiconductors (e. g. Si, In. As, Ga. As) is 4 -5 times the band gap. Much lower thresholds are predicted for QDs because of the relaxation of the need to conserve momentum. The rate of impact ionization is also expected to be much faster in QDs (Auger processes α 1/d 6 ) ● Very efficient exciton multiplication has been experimentally observed in Pb. Se and Pb. S QDs; the threshold photon energy is 2 Eg. Up to 3 electrons per photon (300% QY) have been observed at sufficiently high photon energies ( 4 Eg ). A new model based on coherent superposition of multiexcitonic states is introduced to explain these results. ● For QDs with m*e << m*h (In. P) slowed electron cooling (by about 1 order of magnitude) may be achieved by either fast hole trapping at the surface or by electron injection in the dark, which blocks hot electron cooling via the Auger process(results consistent with earlier results on Cd. Se QDs by Guyot-Sionnest and Klimov). If m*e ~ m*h (Pb. Se and Pb. S) phonon bottleneck and slowed cooling is apparent.

Summary/Conclusions - Continued Three configurations of Quantum Dot Solar Cells are suggested: 1. Nanocrystalline Ti. O 2 sensitized with QDs 2. QD arrays exhibiting 3 -D miniband formation 3. QDs embedded in a polymeric blend of electron- and hole-conducting polymers. These configurations may be expected to produce enhanced photovoltages via hot carrier transport and transfer or enhanced photocurrents via multiple exciton generation. ● THE DYNAMICS OF HOT ELECTRON COOLING, FORWARD AND INVERSE AUGER RECOMBINATION (MEG), AND ELECTRON TRANSFER CAN BE MODIFIED IN QD SYSTEMS TO POTENTIALLY ALLOW VERY EFFICIENT SOLAR PHOTON CONVERSION VIA EFFICIENT MULTIPLE EXCITON GENERATION

Summary/Conclusions - Continued Three configurations of Quantum Dot Solar Cells are suggested: 1. Nanocrystalline Ti. O 2 sensitized with QDs 2. QD arrays exhibiting 3 -D miniband formation 3. QDs embedded in a polymeric blend of electron- and hole-conducting polymers. These configurations may be expected to produce enhanced photovoltages via hot carrier transport and transfer or enhanced photocurrents via multiple exciton generation. ● THE DYNAMICS OF HOT ELECTRON COOLING, FORWARD AND INVERSE AUGER RECOMBINATION (MEG), AND ELECTRON TRANSFER CAN BE MODIFIED IN QD SYSTEMS TO POTENTIALLY ALLOW VERY EFFICIENT SOLAR PHOTON CONVERSION VIA EFFICIENT MULTIPLE EXCITON GENERATION