c24092f5c9de6bfcfbb608be2e467c34.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 45

EE 369 POWER SYSTEM ANALYSIS Lecture 14 Power Flow Tom Overbye and Ross Baldick 1

EE 369 POWER SYSTEM ANALYSIS Lecture 14 Power Flow Tom Overbye and Ross Baldick 1

Announcements l Homework 11 is 6. 24, 6. 26, 6. 28, 6. 30, 6. 38, 6. 42, 6. 43, 6. 46, 6. 49, 6. 50; due Tuesday 11/22. Note that HW is due on Tuesday because Thanksgiving is on Thursday. 2

Announcements l Homework 11 is 6. 24, 6. 26, 6. 28, 6. 30, 6. 38, 6. 42, 6. 43, 6. 46, 6. 49, 6. 50; due Tuesday 11/22. Note that HW is due on Tuesday because Thanksgiving is on Thursday. 2

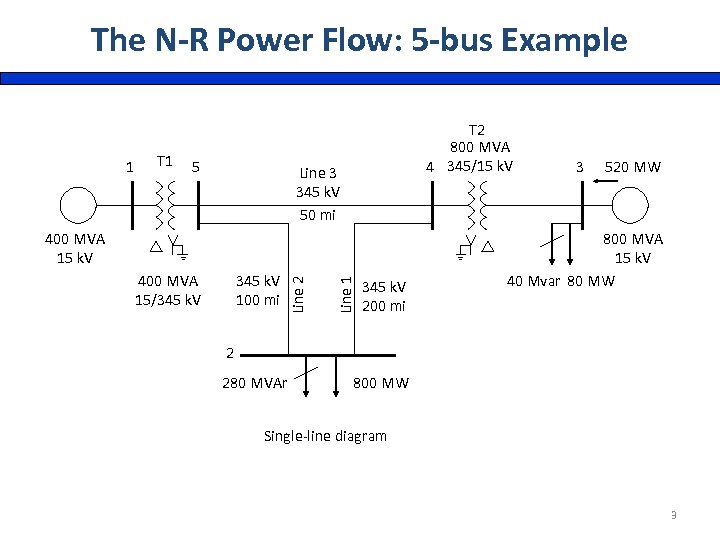

The N-R Power Flow: 5 -bus Example 1 T 1 5 T 2 800 MVA 4 345/15 k. V Line 3 345 k. V 50 mi 345 k. V 100 mi Line 1 400 MVA 15/345 k. V Line 2 400 MVA 15 k. V 345 k. V 200 mi 3 520 MW 800 MVA 15 k. V 40 Mvar 80 MW 2 280 MVAr 800 MW Single-line diagram 3

The N-R Power Flow: 5 -bus Example 1 T 1 5 T 2 800 MVA 4 345/15 k. V Line 3 345 k. V 50 mi 345 k. V 100 mi Line 1 400 MVA 15/345 k. V Line 2 400 MVA 15 k. V 345 k. V 200 mi 3 520 MW 800 MVA 15 k. V 40 Mvar 80 MW 2 280 MVAr 800 MW Single-line diagram 3

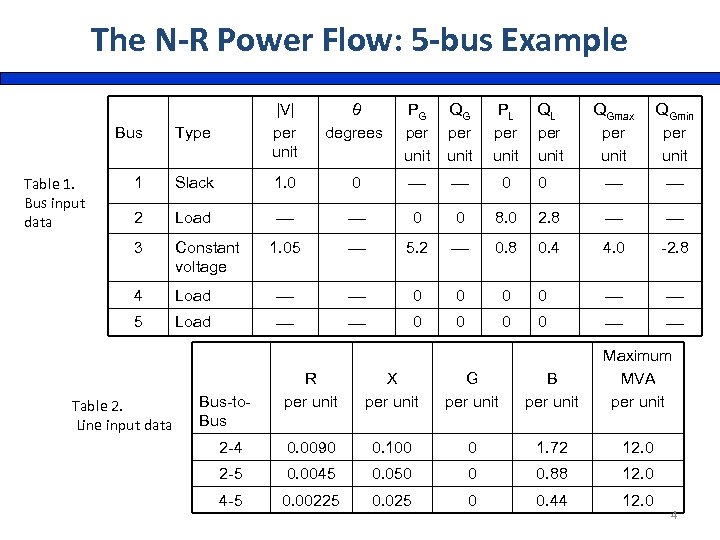

The N-R Power Flow: 5 -bus Example Bus 1 Slack 1. 0 0 0 2 Load 0 0 8. 0 2. 8 3 Constant voltage 1. 05 5. 2 0. 8 0. 4 4. 0 -2. 8 4 Load 0 0 5 Table 1. Bus input data Type |V| per unit Load 0 0 Table 2. Line input data θ degrees PG per unit QG per unit PL per unit QGmax per unit QGmin per unit 0 R per unit X per unit G per unit B per unit Maximum MVA per unit 2 -4 0. 0090 0. 100 0 1. 72 12. 0 2 -5 0. 0045 0. 050 0 0. 88 12. 0 4 -5 0. 00225 0. 025 0 0. 44 12. 0 Bus-to. Bus 4

The N-R Power Flow: 5 -bus Example Bus 1 Slack 1. 0 0 0 2 Load 0 0 8. 0 2. 8 3 Constant voltage 1. 05 5. 2 0. 8 0. 4 4. 0 -2. 8 4 Load 0 0 5 Table 1. Bus input data Type |V| per unit Load 0 0 Table 2. Line input data θ degrees PG per unit QG per unit PL per unit QGmax per unit QGmin per unit 0 R per unit X per unit G per unit B per unit Maximum MVA per unit 2 -4 0. 0090 0. 100 0 1. 72 12. 0 2 -5 0. 0045 0. 050 0 0. 88 12. 0 4 -5 0. 00225 0. 025 0 0. 44 12. 0 Bus-to. Bus 4

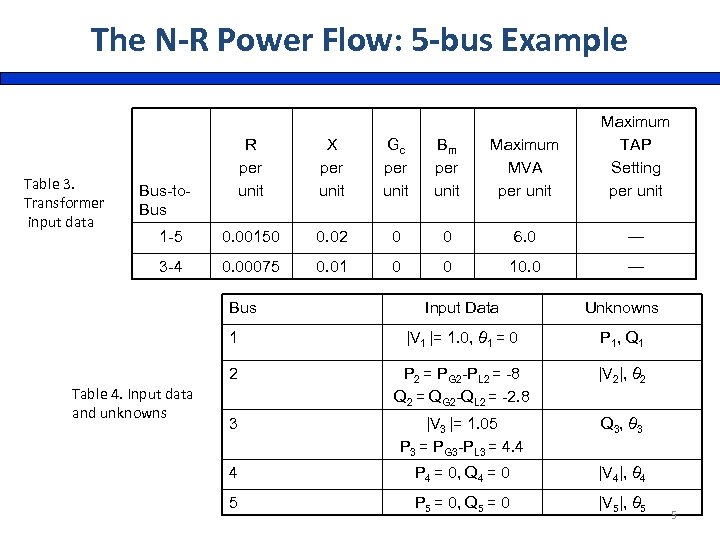

The N-R Power Flow: 5 -bus Example X per unit Gc per unit Bm per unit Maximum MVA per unit 1 -5 0. 00150 0. 02 0 0 6. 0 — 3 -4 Table 3. Transformer input data R per unit Maximum TAP Setting per unit 0. 00075 0. 01 0 0 10. 0 — Bus-to. Bus Unknowns 1 |V 1 |= 1. 0, θ 1 = 0 P 1, Q 1 2 Table 4. Input data and unknowns Input Data P 2 = PG 2 -PL 2 = -8 Q 2 = QG 2 -QL 2 = -2. 8 |V 2|, θ 2 3 |V 3 |= 1. 05 P 3 = PG 3 -PL 3 = 4. 4 Q 3, θ 3 4 P 4 = 0, Q 4 = 0 |V 4|, θ 4 5 P 5 = 0, Q 5 = 0 |V 5|, θ 5 5

The N-R Power Flow: 5 -bus Example X per unit Gc per unit Bm per unit Maximum MVA per unit 1 -5 0. 00150 0. 02 0 0 6. 0 — 3 -4 Table 3. Transformer input data R per unit Maximum TAP Setting per unit 0. 00075 0. 01 0 0 10. 0 — Bus-to. Bus Unknowns 1 |V 1 |= 1. 0, θ 1 = 0 P 1, Q 1 2 Table 4. Input data and unknowns Input Data P 2 = PG 2 -PL 2 = -8 Q 2 = QG 2 -QL 2 = -2. 8 |V 2|, θ 2 3 |V 3 |= 1. 05 P 3 = PG 3 -PL 3 = 4. 4 Q 3, θ 3 4 P 4 = 0, Q 4 = 0 |V 4|, θ 4 5 P 5 = 0, Q 5 = 0 |V 5|, θ 5 5

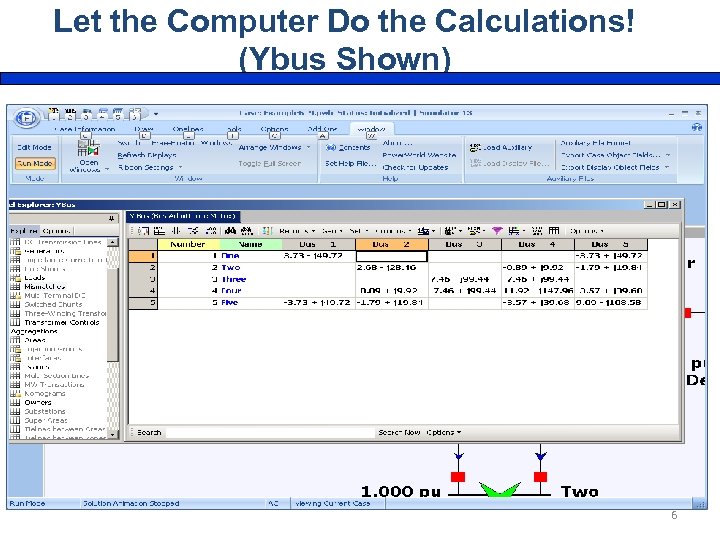

Let the Computer Do the Calculations! (Ybus Shown) 6

Let the Computer Do the Calculations! (Ybus Shown) 6

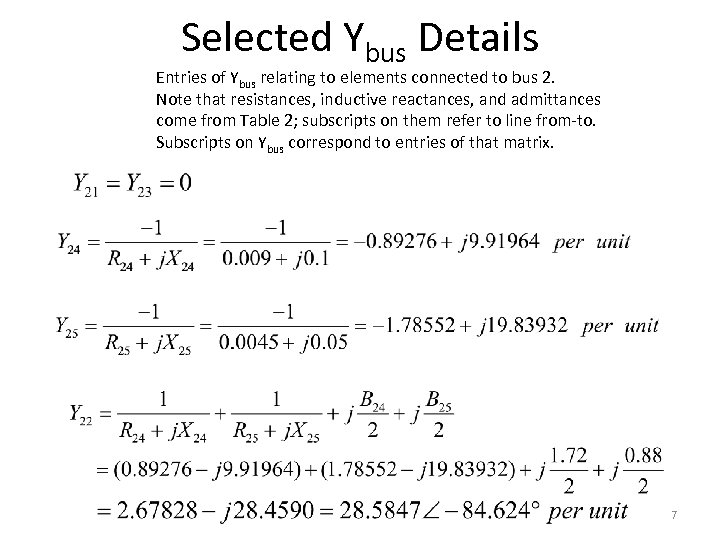

Selected Ybus Details Entries of Ybus relating to elements connected to bus 2. Note that resistances, inductive reactances, and admittances come from Table 2; subscripts on them refer to line from-to. Subscripts on Ybus correspond to entries of that matrix. 7

Selected Ybus Details Entries of Ybus relating to elements connected to bus 2. Note that resistances, inductive reactances, and admittances come from Table 2; subscripts on them refer to line from-to. Subscripts on Ybus correspond to entries of that matrix. 7

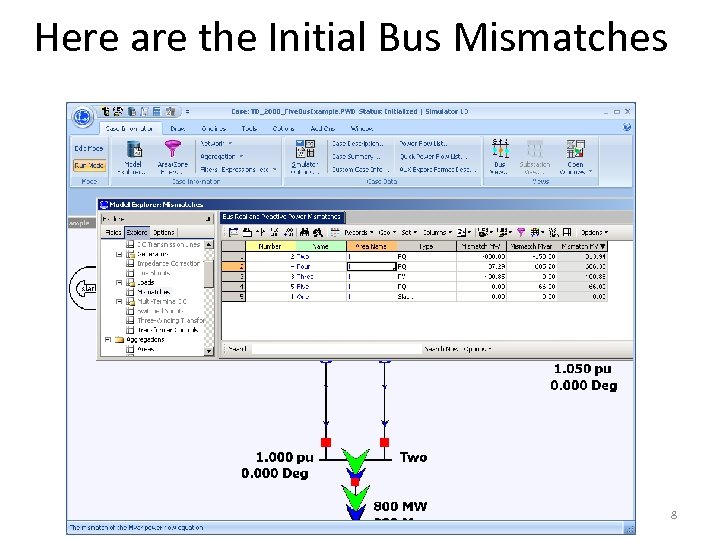

Here are the Initial Bus Mismatches 8

Here are the Initial Bus Mismatches 8

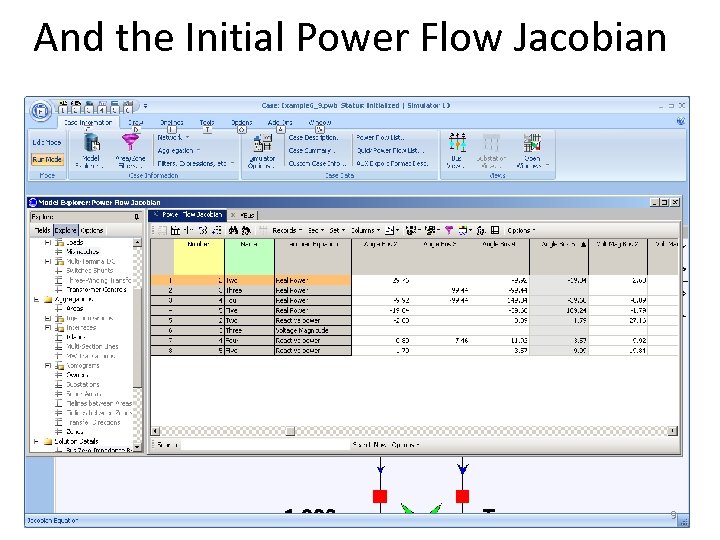

And the Initial Power Flow Jacobian 9

And the Initial Power Flow Jacobian 9

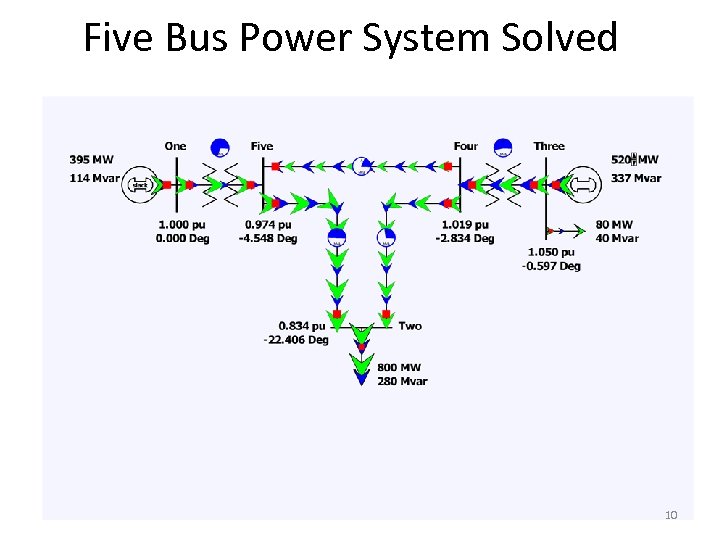

Five Bus Power System Solved 10

Five Bus Power System Solved 10

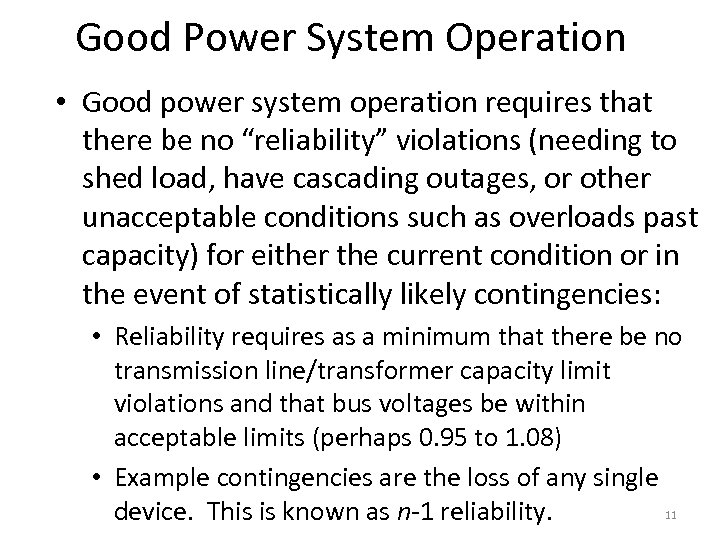

Good Power System Operation • Good power system operation requires that there be no “reliability” violations (needing to shed load, have cascading outages, or other unacceptable conditions such as overloads past capacity) for either the current condition or in the event of statistically likely contingencies: • Reliability requires as a minimum that there be no transmission line/transformer capacity limit violations and that bus voltages be within acceptable limits (perhaps 0. 95 to 1. 08) • Example contingencies are the loss of any single 11 device. This is known as n-1 reliability.

Good Power System Operation • Good power system operation requires that there be no “reliability” violations (needing to shed load, have cascading outages, or other unacceptable conditions such as overloads past capacity) for either the current condition or in the event of statistically likely contingencies: • Reliability requires as a minimum that there be no transmission line/transformer capacity limit violations and that bus voltages be within acceptable limits (perhaps 0. 95 to 1. 08) • Example contingencies are the loss of any single 11 device. This is known as n-1 reliability.

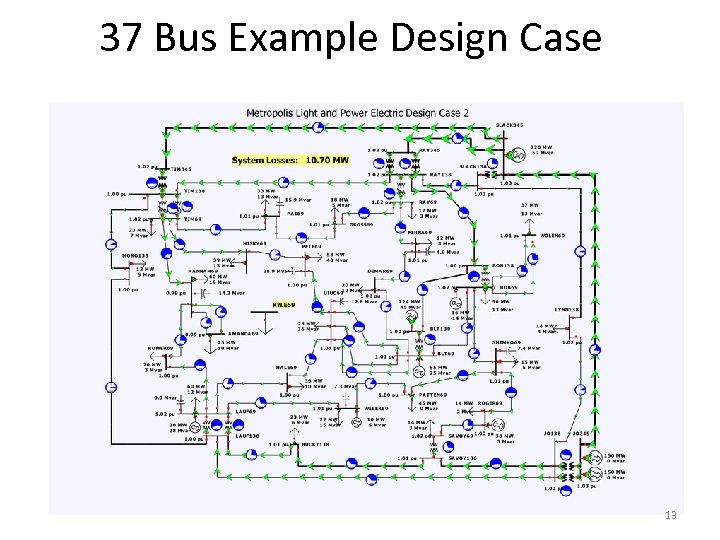

Good Power System Operation • North American Electric Reliability Corporation now has legal authority to enforce reliability standards (and there are now lots of them). • See http: //www. nerc. com for details (click on Standards) • Consider impact of line contingency on 37 bus design example case. 12

Good Power System Operation • North American Electric Reliability Corporation now has legal authority to enforce reliability standards (and there are now lots of them). • See http: //www. nerc. com for details (click on Standards) • Consider impact of line contingency on 37 bus design example case. 12

37 Bus Example Design Case 13

37 Bus Example Design Case 13

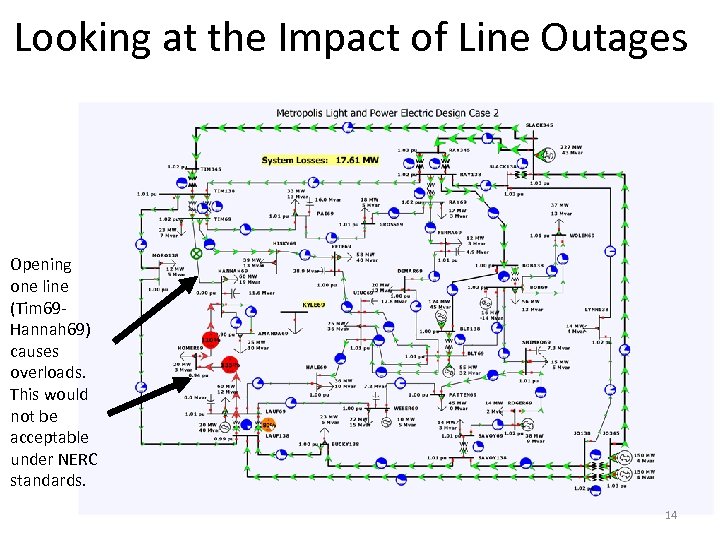

Looking at the Impact of Line Outages Opening one line (Tim 69 Hannah 69) causes overloads. This would not be acceptable under NERC standards. 14

Looking at the Impact of Line Outages Opening one line (Tim 69 Hannah 69) causes overloads. This would not be acceptable under NERC standards. 14

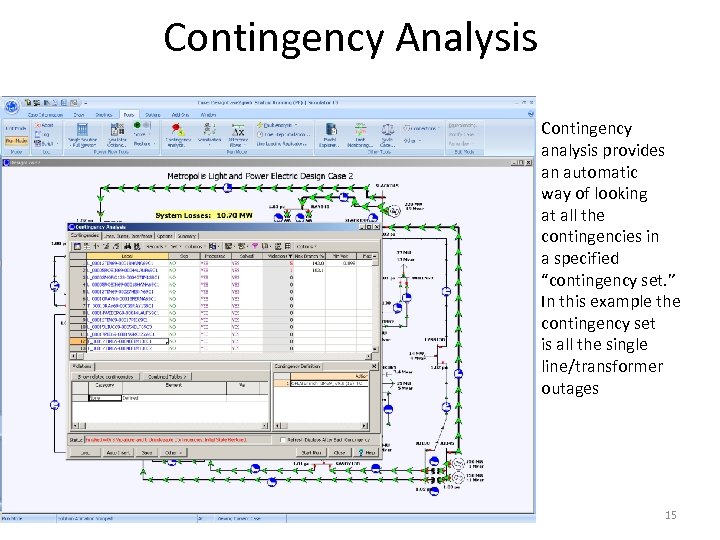

Contingency Analysis Contingency analysis provides an automatic way of looking at all the contingencies in a specified “contingency set. ” In this example the contingency set is all the single line/transformer outages 15

Contingency Analysis Contingency analysis provides an automatic way of looking at all the contingencies in a specified “contingency set. ” In this example the contingency set is all the single line/transformer outages 15

Power Flow And Design • One common usage of the power flow is to determine how the system should be modified to remove contingencies problems or serve new load • In an operational context this requires working with the existing electric grid, typically involving redispatch of generation. • In a planning context additions to the grid can be considered as well as re-dispatch. • In the next example we look at how to add a new line in order to remove the existing contingency violations while serving new load. 16

Power Flow And Design • One common usage of the power flow is to determine how the system should be modified to remove contingencies problems or serve new load • In an operational context this requires working with the existing electric grid, typically involving redispatch of generation. • In a planning context additions to the grid can be considered as well as re-dispatch. • In the next example we look at how to add a new line in order to remove the existing contingency violations while serving new load. 16

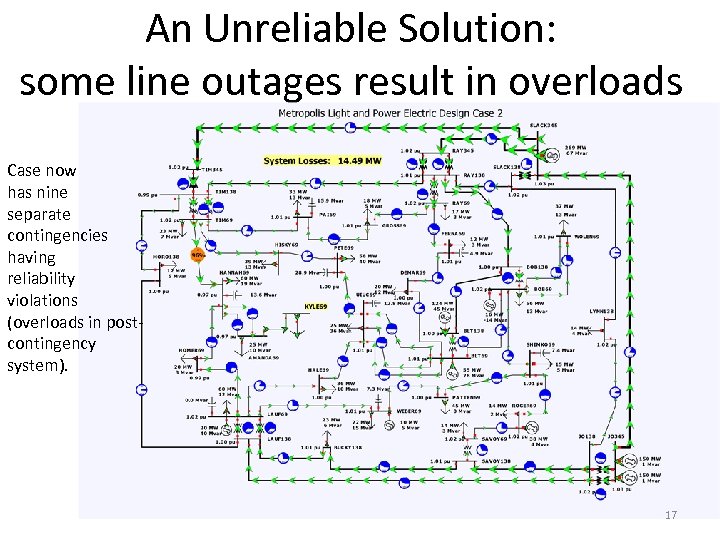

An Unreliable Solution: some line outages result in overloads Case now has nine separate contingencies having reliability violations (overloads in postcontingency system). 17

An Unreliable Solution: some line outages result in overloads Case now has nine separate contingencies having reliability violations (overloads in postcontingency system). 17

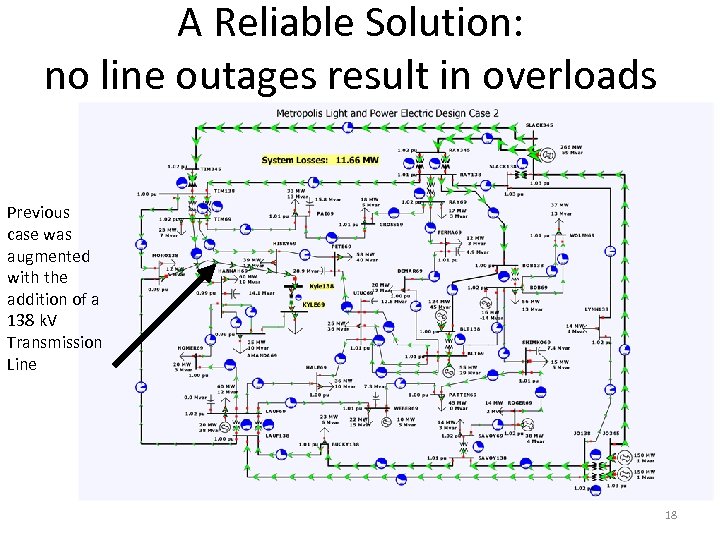

A Reliable Solution: no line outages result in overloads Previous case was augmented with the addition of a 138 k. V Transmission Line 18

A Reliable Solution: no line outages result in overloads Previous case was augmented with the addition of a 138 k. V Transmission Line 18

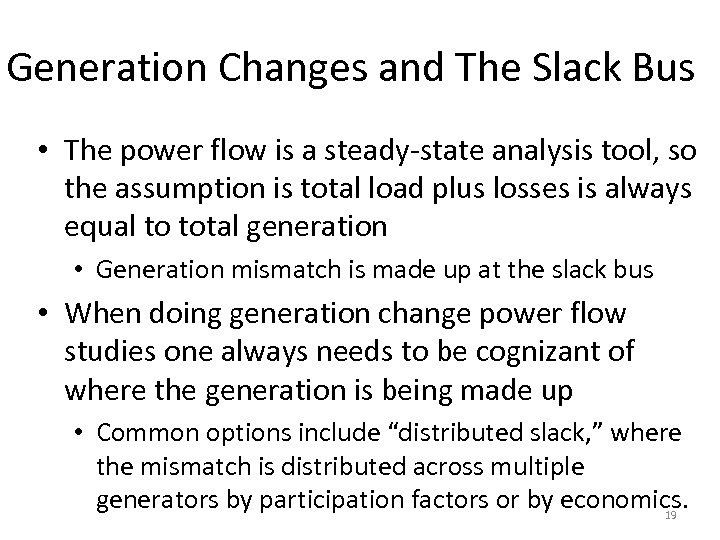

Generation Changes and The Slack Bus • The power flow is a steady-state analysis tool, so the assumption is total load plus losses is always equal to total generation • Generation mismatch is made up at the slack bus • When doing generation change power flow studies one always needs to be cognizant of where the generation is being made up • Common options include “distributed slack, ” where the mismatch is distributed across multiple generators by participation factors or by economics. 19

Generation Changes and The Slack Bus • The power flow is a steady-state analysis tool, so the assumption is total load plus losses is always equal to total generation • Generation mismatch is made up at the slack bus • When doing generation change power flow studies one always needs to be cognizant of where the generation is being made up • Common options include “distributed slack, ” where the mismatch is distributed across multiple generators by participation factors or by economics. 19

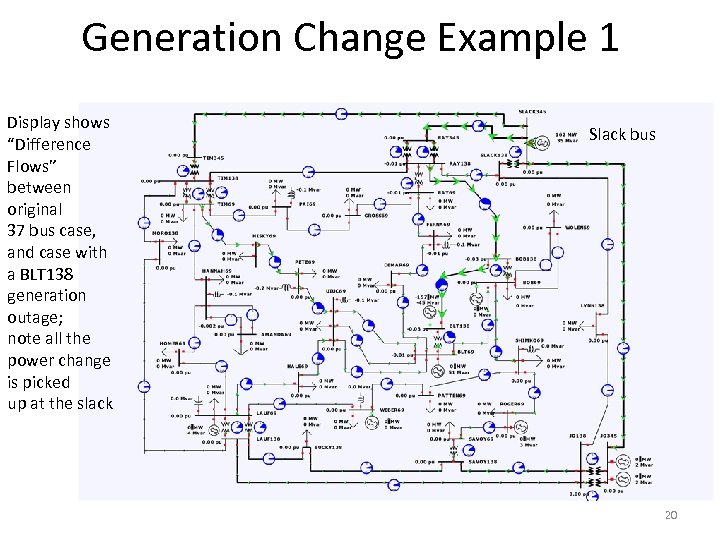

Generation Change Example 1 Display shows “Difference Flows” between original 37 bus case, and case with a BLT 138 generation outage; note all the power change is picked up at the slack Slack bus 20

Generation Change Example 1 Display shows “Difference Flows” between original 37 bus case, and case with a BLT 138 generation outage; note all the power change is picked up at the slack Slack bus 20

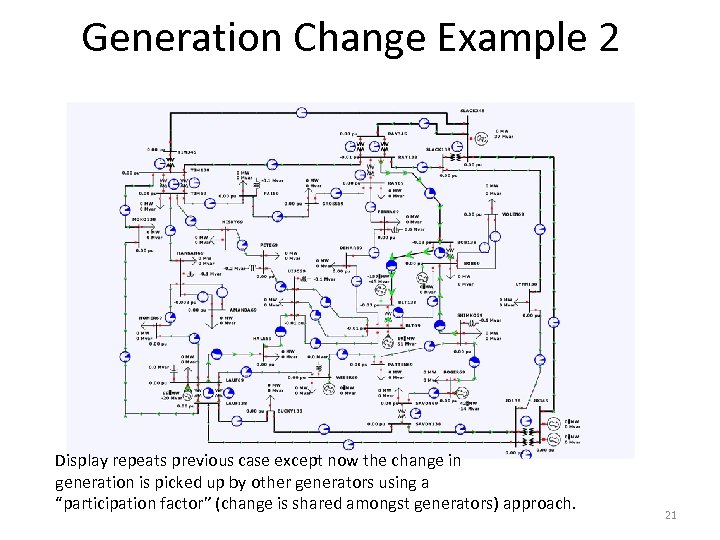

Generation Change Example 2 Display repeats previous case except now the change in generation is picked up by other generators using a “participation factor” (change is shared amongst generators) approach. 21

Generation Change Example 2 Display repeats previous case except now the change in generation is picked up by other generators using a “participation factor” (change is shared amongst generators) approach. 21

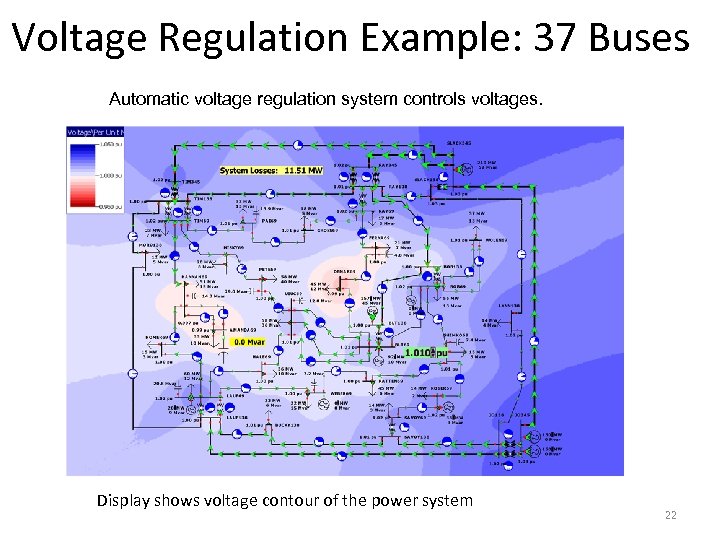

Voltage Regulation Example: 37 Buses Automatic voltage regulation system controls voltages. Display shows voltage contour of the power system 22

Voltage Regulation Example: 37 Buses Automatic voltage regulation system controls voltages. Display shows voltage contour of the power system 22

Real-sized Power Flow Cases • Real power flow studies are usually done with cases with many thousands of buses • Outside of ERCOT, buses are usually grouped into various balancing authority areas, with each area doing its own interchange control. • Cases also model a variety of different automatic control devices, such as generator reactive power limits, load tap changing transformers, phase shifting transformers, switched capacitors, HVDC transmission lines, and (potentially) FACTS devices. 23

Real-sized Power Flow Cases • Real power flow studies are usually done with cases with many thousands of buses • Outside of ERCOT, buses are usually grouped into various balancing authority areas, with each area doing its own interchange control. • Cases also model a variety of different automatic control devices, such as generator reactive power limits, load tap changing transformers, phase shifting transformers, switched capacitors, HVDC transmission lines, and (potentially) FACTS devices. 23

Sparse Matrices and Large Systems • Since for realistic power systems the model sizes are quite large, this means the Ybus and Jacobian matrices are also large. • However, most elements in these matrices are zero, therefore special techniques, sparse matrix/vector methods, are used to store the values and solve the power flow: • Without these techniques large systems would be essentially unsolvable. 24

Sparse Matrices and Large Systems • Since for realistic power systems the model sizes are quite large, this means the Ybus and Jacobian matrices are also large. • However, most elements in these matrices are zero, therefore special techniques, sparse matrix/vector methods, are used to store the values and solve the power flow: • Without these techniques large systems would be essentially unsolvable. 24

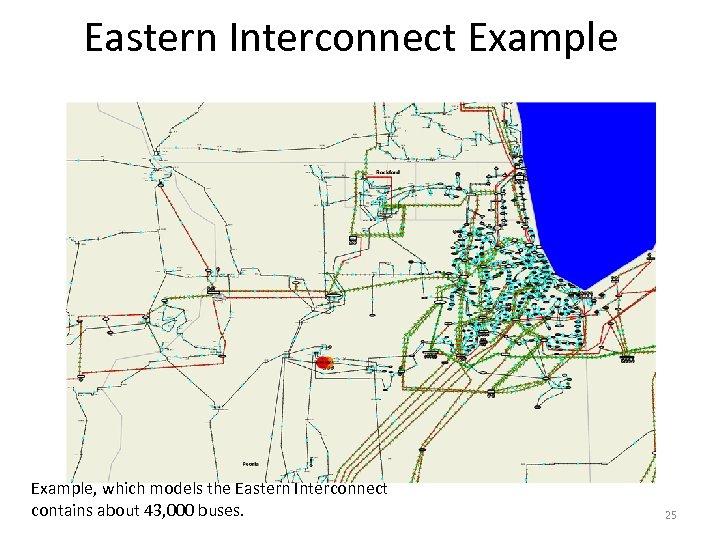

Eastern Interconnect Example, which models the Eastern Interconnect contains about 43, 000 buses. 25

Eastern Interconnect Example, which models the Eastern Interconnect contains about 43, 000 buses. 25

Solution Log for 1200 MW Outage In this example the losss of a 1200 MW generator in Northern Illinois was simulated. This caused a generation imbalance in the associated balancing authority area, which was corrected by a redispatch of local generation. 26

Solution Log for 1200 MW Outage In this example the losss of a 1200 MW generator in Northern Illinois was simulated. This caused a generation imbalance in the associated balancing authority area, which was corrected by a redispatch of local generation. 26

Interconnected Operation l Power systems are interconnected across large distances. l For example most of North America east of the Rockies is one system, most of North America west of the Rockies is another. l Most of Texas and Quebec are each interconnected systems. 27

Interconnected Operation l Power systems are interconnected across large distances. l For example most of North America east of the Rockies is one system, most of North America west of the Rockies is another. l Most of Texas and Quebec are each interconnected systems. 27

Balancing Authority Areas l A “balancing authority area” (previously called a “control area”) has traditionally represented the portion of the interconnected electric grid operated by a single utility or transmission entity. l Transmission lines that join two areas are known as tie-lines. l The net power out of an area is the sum of the flow on its tie-lines. l The flow out of an area is equal to total gen - total load - total losses = tie-line flow 28

Balancing Authority Areas l A “balancing authority area” (previously called a “control area”) has traditionally represented the portion of the interconnected electric grid operated by a single utility or transmission entity. l Transmission lines that join two areas are known as tie-lines. l The net power out of an area is the sum of the flow on its tie-lines. l The flow out of an area is equal to total gen - total load - total losses = tie-line flow 28

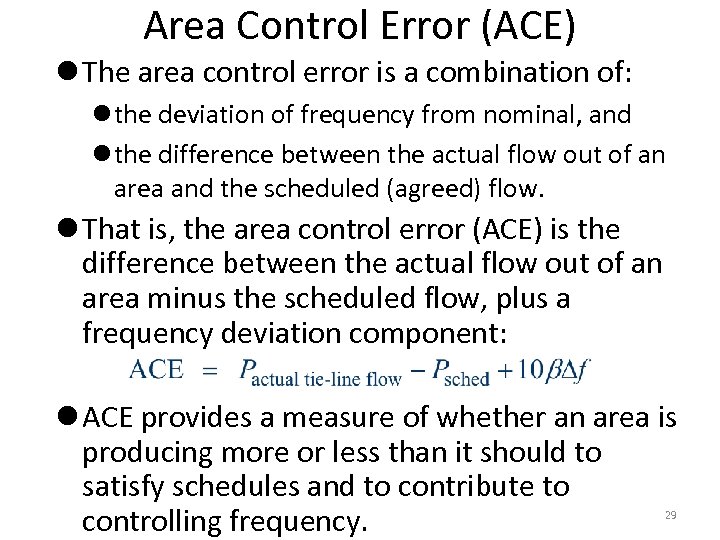

Area Control Error (ACE) l The area control error is a combination of: l the deviation of frequency from nominal, and l the difference between the actual flow out of an area and the scheduled (agreed) flow. l That is, the area control error (ACE) is the difference between the actual flow out of an area minus the scheduled flow, plus a frequency deviation component: l ACE provides a measure of whether an area is producing more or less than it should to satisfy schedules and to contribute to controlling frequency. 29

Area Control Error (ACE) l The area control error is a combination of: l the deviation of frequency from nominal, and l the difference between the actual flow out of an area and the scheduled (agreed) flow. l That is, the area control error (ACE) is the difference between the actual flow out of an area minus the scheduled flow, plus a frequency deviation component: l ACE provides a measure of whether an area is producing more or less than it should to satisfy schedules and to contribute to controlling frequency. 29

Area Control Error (ACE) l The ideal is for ACE to be zero. l Because the load is constantly changing, each area must constantly change its generation to drive the ACE towards zero. l For ERCOT, the historical ten control areas were amalgamated into one in 2001, so the actual and scheduled interchange are essentially the same (both small compared to total demand in ERCOT). l In ERCOT, ACE is predominantly due to frequency deviations from nominal since there is very little scheduled flow to or from other areas outside of ERCOT. 30

Area Control Error (ACE) l The ideal is for ACE to be zero. l Because the load is constantly changing, each area must constantly change its generation to drive the ACE towards zero. l For ERCOT, the historical ten control areas were amalgamated into one in 2001, so the actual and scheduled interchange are essentially the same (both small compared to total demand in ERCOT). l In ERCOT, ACE is predominantly due to frequency deviations from nominal since there is very little scheduled flow to or from other areas outside of ERCOT. 30

Automatic Generation Control l Most systems use automatic generation control (AGC) to automatically change generation to keep their ACE close to zero. l Usually the control center (either ISO or utility) calculates ACE based upon tie-line flows and frequency; then the AGC module sends control signals out to the generators every four seconds or so. 31

Automatic Generation Control l Most systems use automatic generation control (AGC) to automatically change generation to keep their ACE close to zero. l Usually the control center (either ISO or utility) calculates ACE based upon tie-line flows and frequency; then the AGC module sends control signals out to the generators every four seconds or so. 31

Power Transactions l Power transactions are contracts between generators and (representatives of) loads. l Contracts can be for any amount of time at any price for any amount of power. l Scheduled power transactions between balancing areas are called “interchange” and implemented by setting the value of Psched used in the ACE calculation: l ACE = Pactual tie-line flow – Psched + 10β Δf l …and then controlling the generation to bring 32 ACE towards zero.

Power Transactions l Power transactions are contracts between generators and (representatives of) loads. l Contracts can be for any amount of time at any price for any amount of power. l Scheduled power transactions between balancing areas are called “interchange” and implemented by setting the value of Psched used in the ACE calculation: l ACE = Pactual tie-line flow – Psched + 10β Δf l …and then controlling the generation to bring 32 ACE towards zero.

“Physical” power Transactions • For ERCOT, interchange is only relevant over asynchronous connections between ERCOT and Eastern Interconnection or Mexico. • In Eastern and Western Interconnection, interchange occurs between areas connected by AC lines. 33

“Physical” power Transactions • For ERCOT, interchange is only relevant over asynchronous connections between ERCOT and Eastern Interconnection or Mexico. • In Eastern and Western Interconnection, interchange occurs between areas connected by AC lines. 33

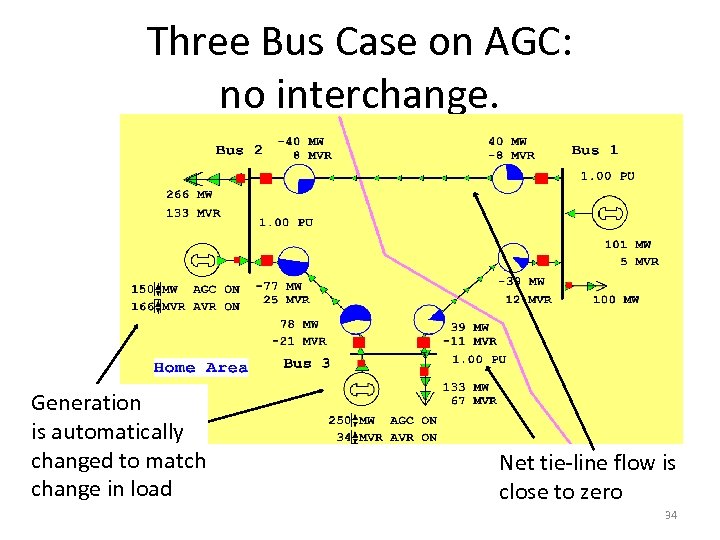

Three Bus Case on AGC: no interchange. Generation is automatically changed to match change in load Net tie-line flow is close to zero 34

Three Bus Case on AGC: no interchange. Generation is automatically changed to match change in load Net tie-line flow is close to zero 34

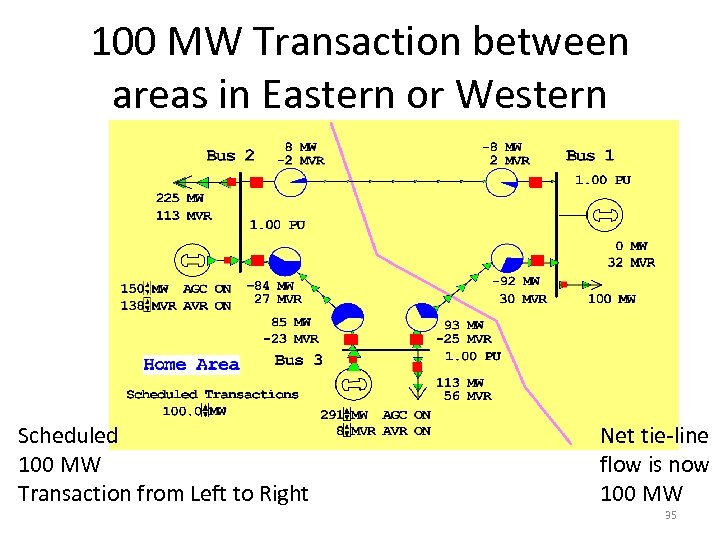

100 MW Transaction between areas in Eastern or Western Scheduled 100 MW Transaction from Left to Right Net tie-line flow is now 100 MW 35

100 MW Transaction between areas in Eastern or Western Scheduled 100 MW Transaction from Left to Right Net tie-line flow is now 100 MW 35

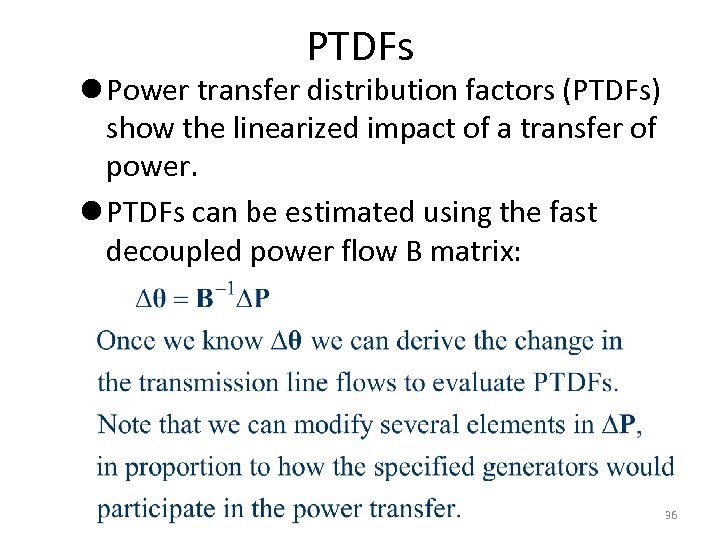

PTDFs l Power transfer distribution factors (PTDFs) show the linearized impact of a transfer of power. l PTDFs can be estimated using the fast decoupled power flow B matrix: 36

PTDFs l Power transfer distribution factors (PTDFs) show the linearized impact of a transfer of power. l PTDFs can be estimated using the fast decoupled power flow B matrix: 36

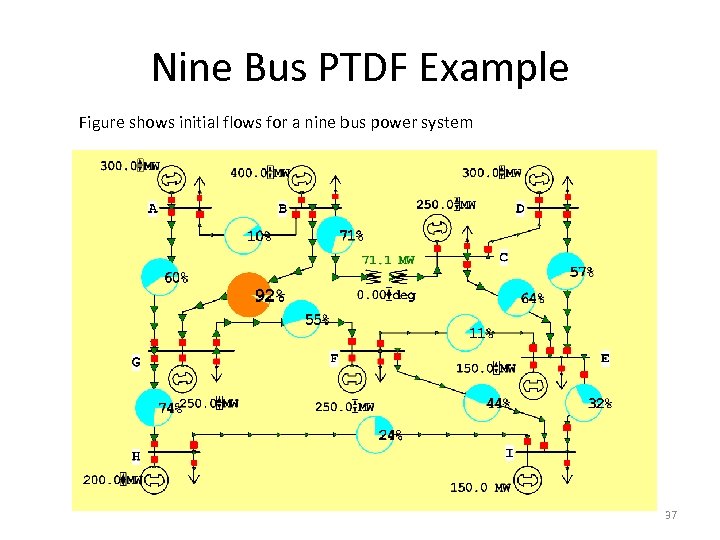

Nine Bus PTDF Example Figure shows initial flows for a nine bus power system 37

Nine Bus PTDF Example Figure shows initial flows for a nine bus power system 37

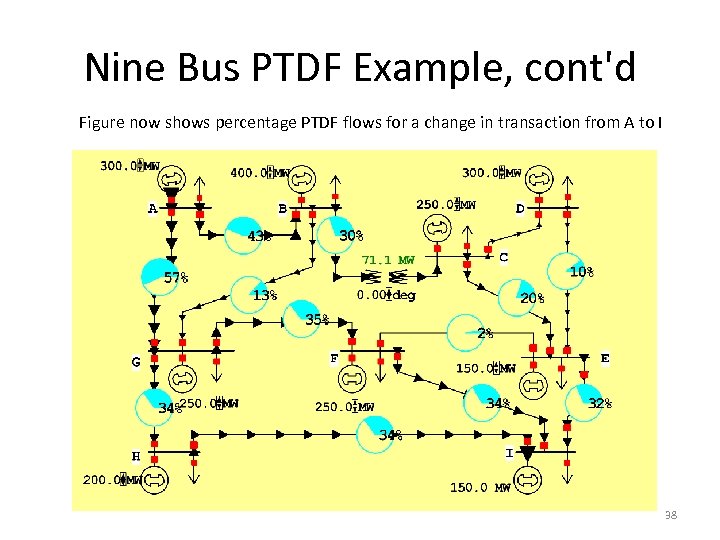

Nine Bus PTDF Example, cont'd Figure now shows percentage PTDF flows for a change in transaction from A to I 38

Nine Bus PTDF Example, cont'd Figure now shows percentage PTDF flows for a change in transaction from A to I 38

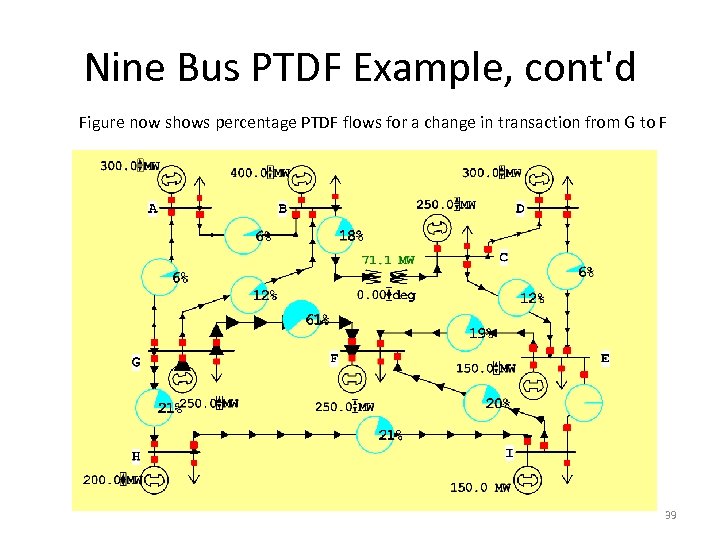

Nine Bus PTDF Example, cont'd Figure now shows percentage PTDF flows for a change in transaction from G to F 39

Nine Bus PTDF Example, cont'd Figure now shows percentage PTDF flows for a change in transaction from G to F 39

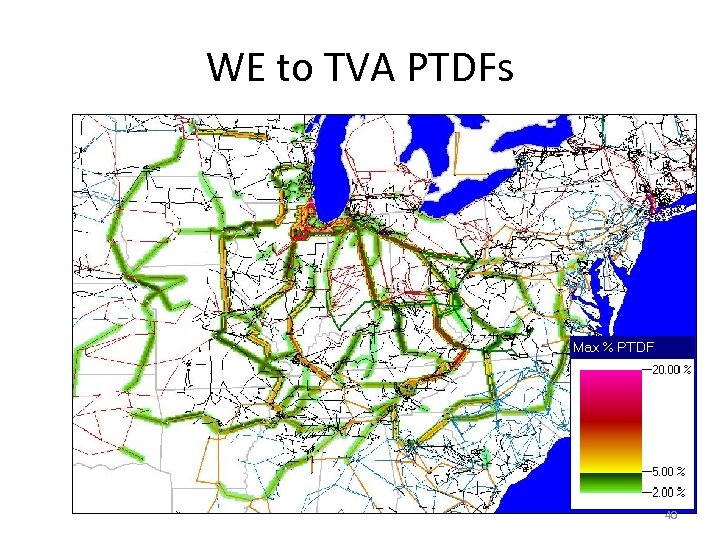

WE to TVA PTDFs 40

WE to TVA PTDFs 40

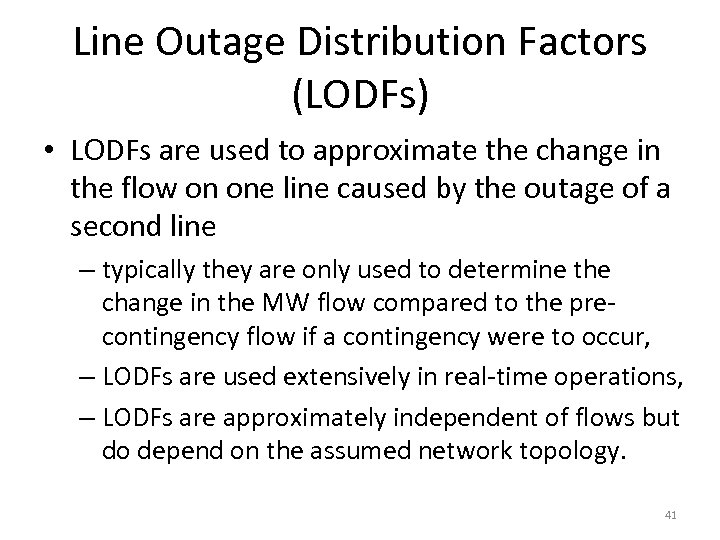

Line Outage Distribution Factors (LODFs) • LODFs are used to approximate the change in the flow on one line caused by the outage of a second line – typically they are only used to determine the change in the MW flow compared to the precontingency flow if a contingency were to occur, – LODFs are used extensively in real-time operations, – LODFs are approximately independent of flows but do depend on the assumed network topology. 41

Line Outage Distribution Factors (LODFs) • LODFs are used to approximate the change in the flow on one line caused by the outage of a second line – typically they are only used to determine the change in the MW flow compared to the precontingency flow if a contingency were to occur, – LODFs are used extensively in real-time operations, – LODFs are approximately independent of flows but do depend on the assumed network topology. 41

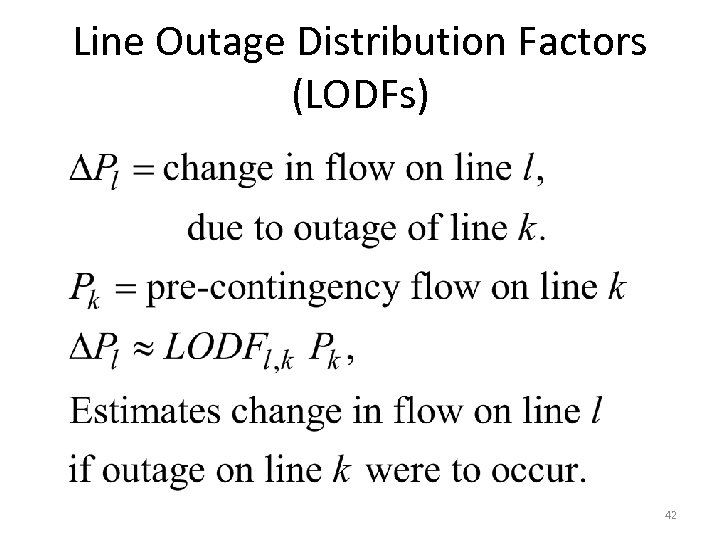

Line Outage Distribution Factors (LODFs) 42

Line Outage Distribution Factors (LODFs) 42

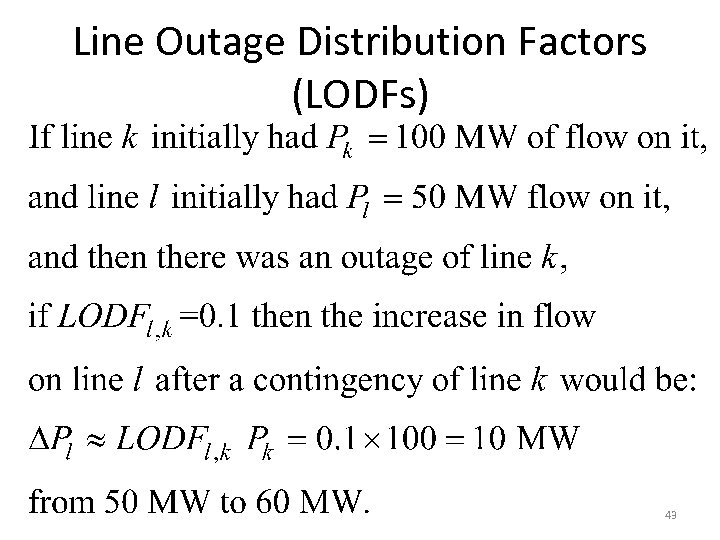

Line Outage Distribution Factors (LODFs) 43

Line Outage Distribution Factors (LODFs) 43

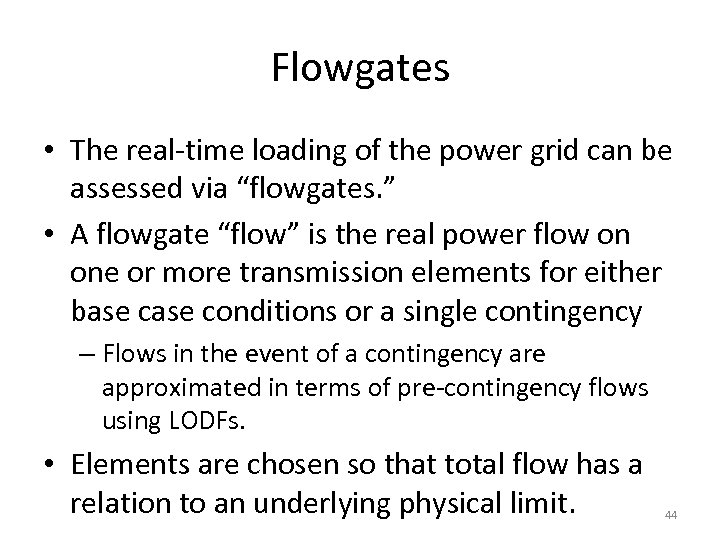

Flowgates • The real-time loading of the power grid can be assessed via “flowgates. ” • A flowgate “flow” is the real power flow on one or more transmission elements for either base conditions or a single contingency – Flows in the event of a contingency are approximated in terms of pre-contingency flows using LODFs. • Elements are chosen so that total flow has a relation to an underlying physical limit. 44

Flowgates • The real-time loading of the power grid can be assessed via “flowgates. ” • A flowgate “flow” is the real power flow on one or more transmission elements for either base conditions or a single contingency – Flows in the event of a contingency are approximated in terms of pre-contingency flows using LODFs. • Elements are chosen so that total flow has a relation to an underlying physical limit. 44

Flowgates • Limits due to voltage or stability limits are often represented by effective flowgate limits, which are acting as “proxies” for these other types of limits. • Flowgate limits are also often used to represent thermal constraints on corridors of multiple lines between zones or areas. • The inter-zonal constraints that were used in ERCOT until December 2010 are flowgates that represent inter-zonal corridors of lines. 45

Flowgates • Limits due to voltage or stability limits are often represented by effective flowgate limits, which are acting as “proxies” for these other types of limits. • Flowgate limits are also often used to represent thermal constraints on corridors of multiple lines between zones or areas. • The inter-zonal constraints that were used in ERCOT until December 2010 are flowgates that represent inter-zonal corridors of lines. 45