Education in UKDecide which of the words in

education_in_gb.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 21

Education in UK

Education in UK

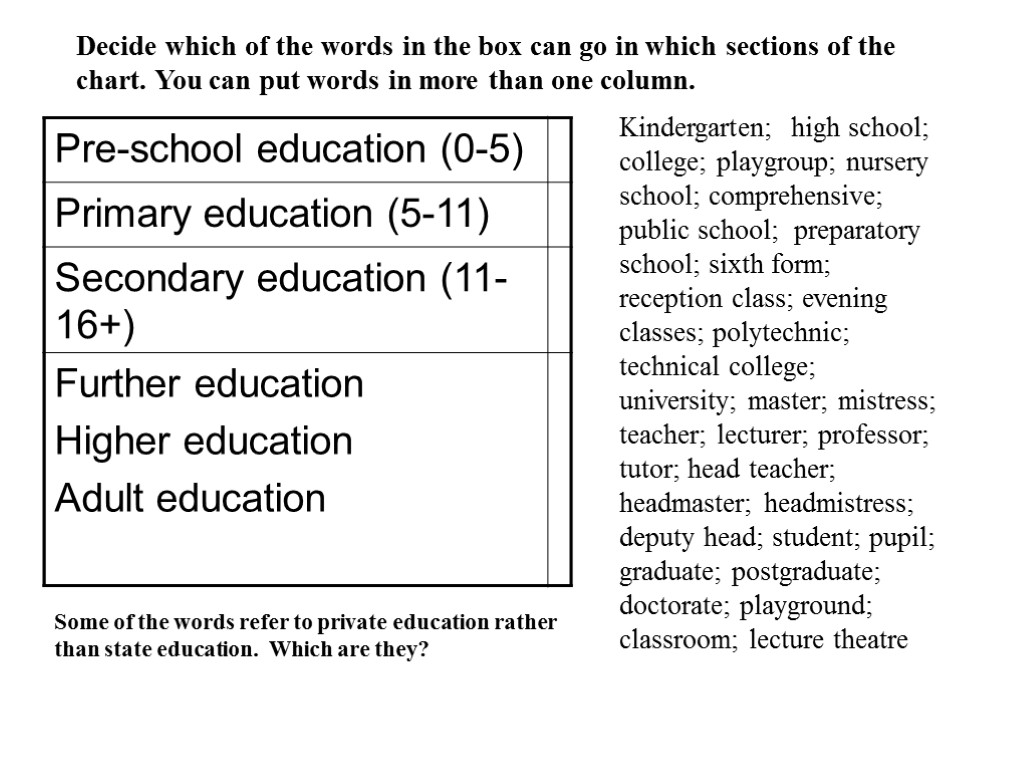

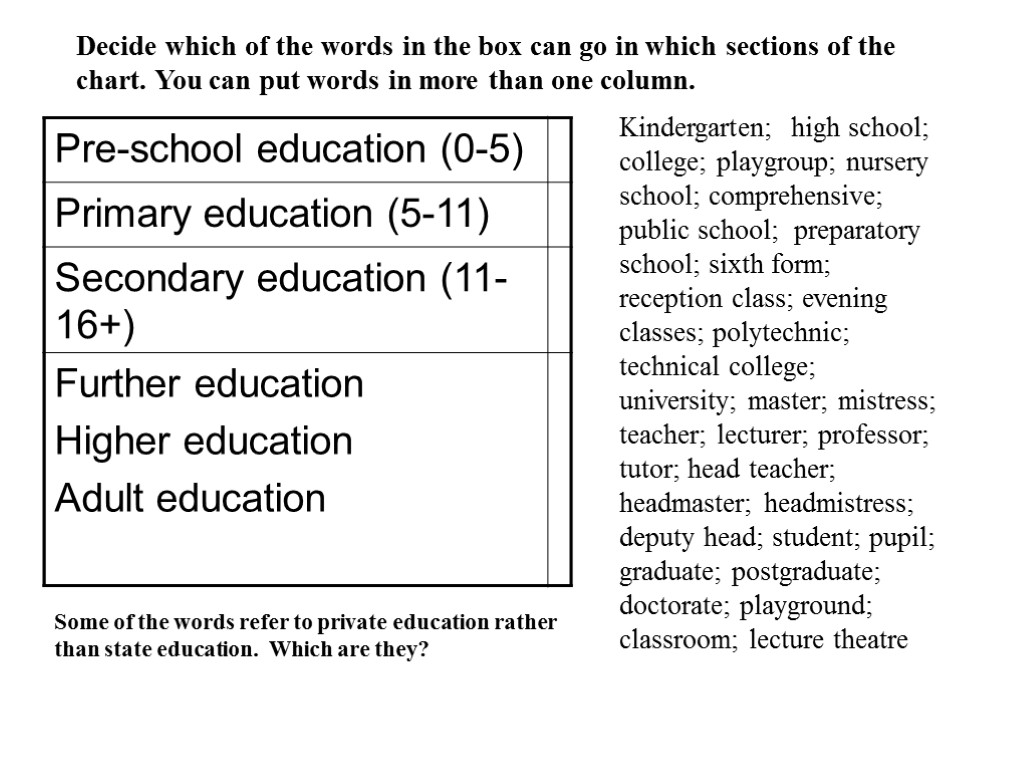

Decide which of the words in the box can go in which sections of the chart. You can put words in more than one column. Kindergarten; high school; college; playgroup; nursery school; comprehensive; public school; preparatory school; sixth form; reception class; evening classes; polytechnic; technical college; university; master; mistress; teacher; lecturer; professor; tutor; head teacher; headmaster; headmistress; deputy head; student; pupil; graduate; postgraduate; doctorate; playground; classroom; lecture theatre Some of the words refer to private education rather than state education. Which are they?

Decide which of the words in the box can go in which sections of the chart. You can put words in more than one column. Kindergarten; high school; college; playgroup; nursery school; comprehensive; public school; preparatory school; sixth form; reception class; evening classes; polytechnic; technical college; university; master; mistress; teacher; lecturer; professor; tutor; head teacher; headmaster; headmistress; deputy head; student; pupil; graduate; postgraduate; doctorate; playground; classroom; lecture theatre Some of the words refer to private education rather than state education. Which are they?

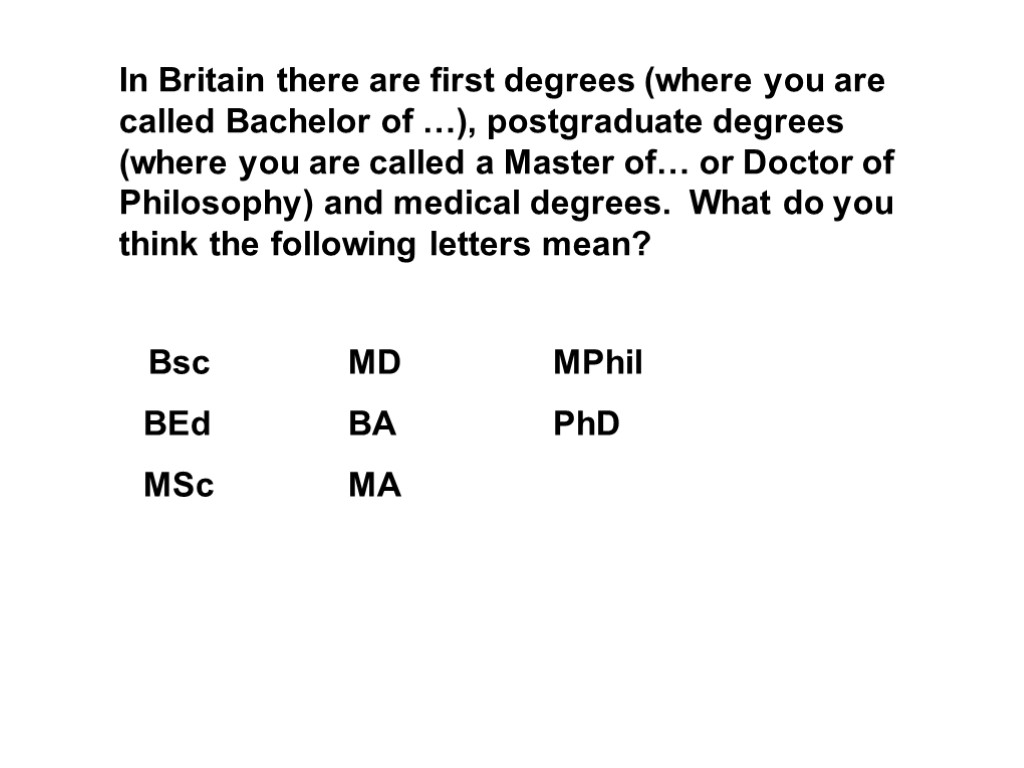

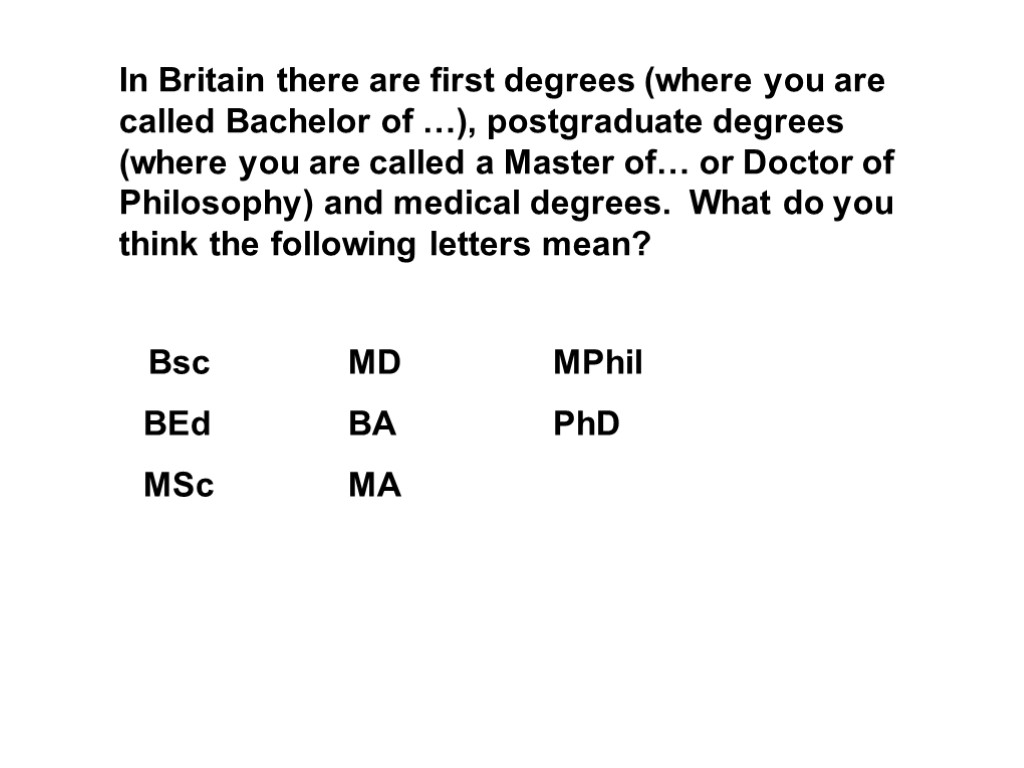

In Britain there are first degrees (where you are called Bachelor of …), postgraduate degrees (where you are called a Master of… or Doctor of Philosophy) and medical degrees. What do you think the following letters mean? Bsc MD MPhil BEd BA PhD MSc MA

In Britain there are first degrees (where you are called Bachelor of …), postgraduate degrees (where you are called a Master of… or Doctor of Philosophy) and medical degrees. What do you think the following letters mean? Bsc MD MPhil BEd BA PhD MSc MA

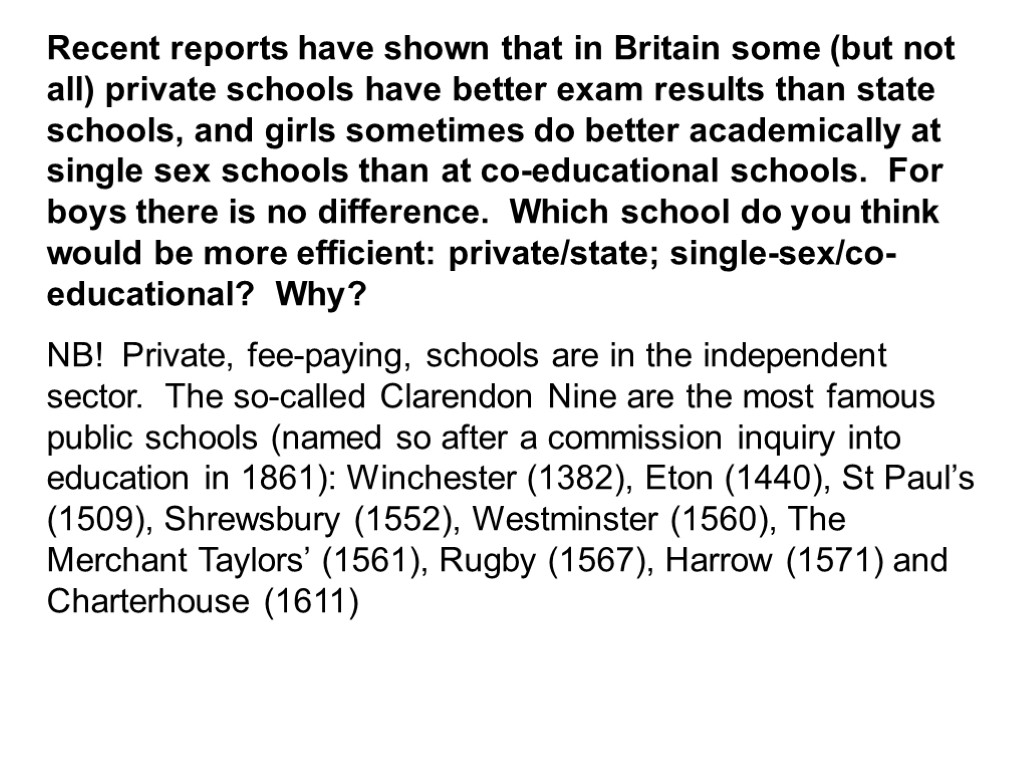

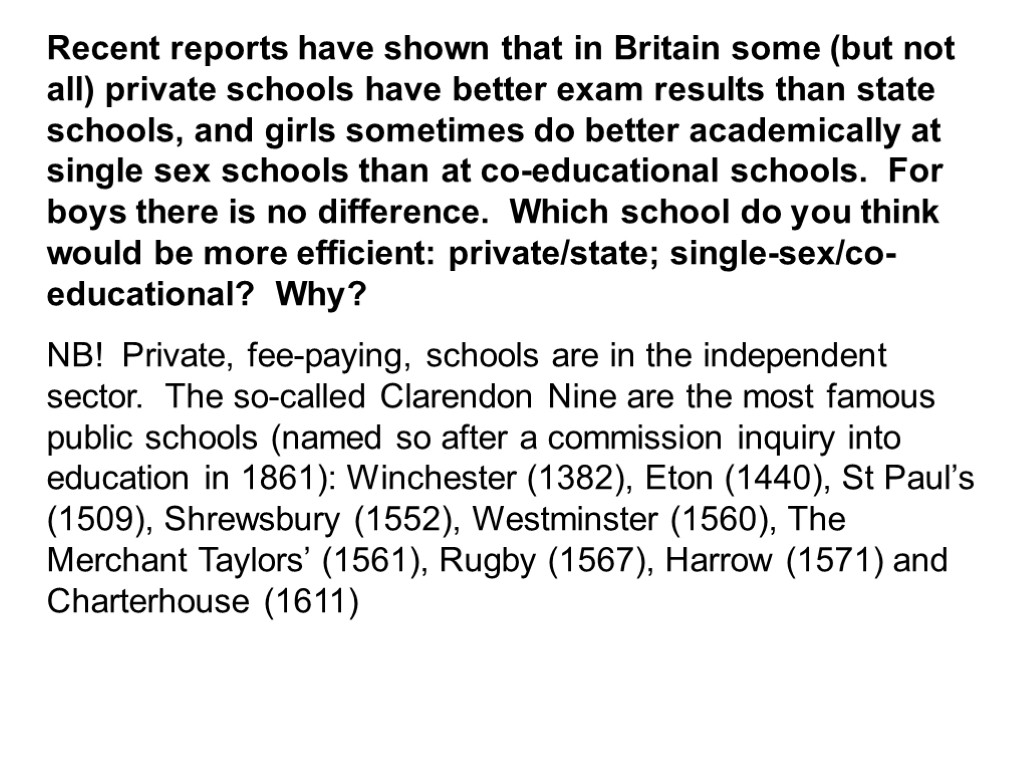

Recent reports have shown that in Britain some (but not all) private schools have better exam results than state schools, and girls sometimes do better academically at single sex schools than at co-educational schools. For boys there is no difference. Which school do you think would be more efficient: private/state; single-sex/co-educational? Why? NB! Private, fee-paying, schools are in the independent sector. The so-called Clarendon Nine are the most famous public schools (named so after a commission inquiry into education in 1861): Winchester (1382), Eton (1440), St Paul’s (1509), Shrewsbury (1552), Westminster (1560), The Merchant Taylors’ (1561), Rugby (1567), Harrow (1571) and Charterhouse (1611)

Recent reports have shown that in Britain some (but not all) private schools have better exam results than state schools, and girls sometimes do better academically at single sex schools than at co-educational schools. For boys there is no difference. Which school do you think would be more efficient: private/state; single-sex/co-educational? Why? NB! Private, fee-paying, schools are in the independent sector. The so-called Clarendon Nine are the most famous public schools (named so after a commission inquiry into education in 1861): Winchester (1382), Eton (1440), St Paul’s (1509), Shrewsbury (1552), Westminster (1560), The Merchant Taylors’ (1561), Rugby (1567), Harrow (1571) and Charterhouse (1611)

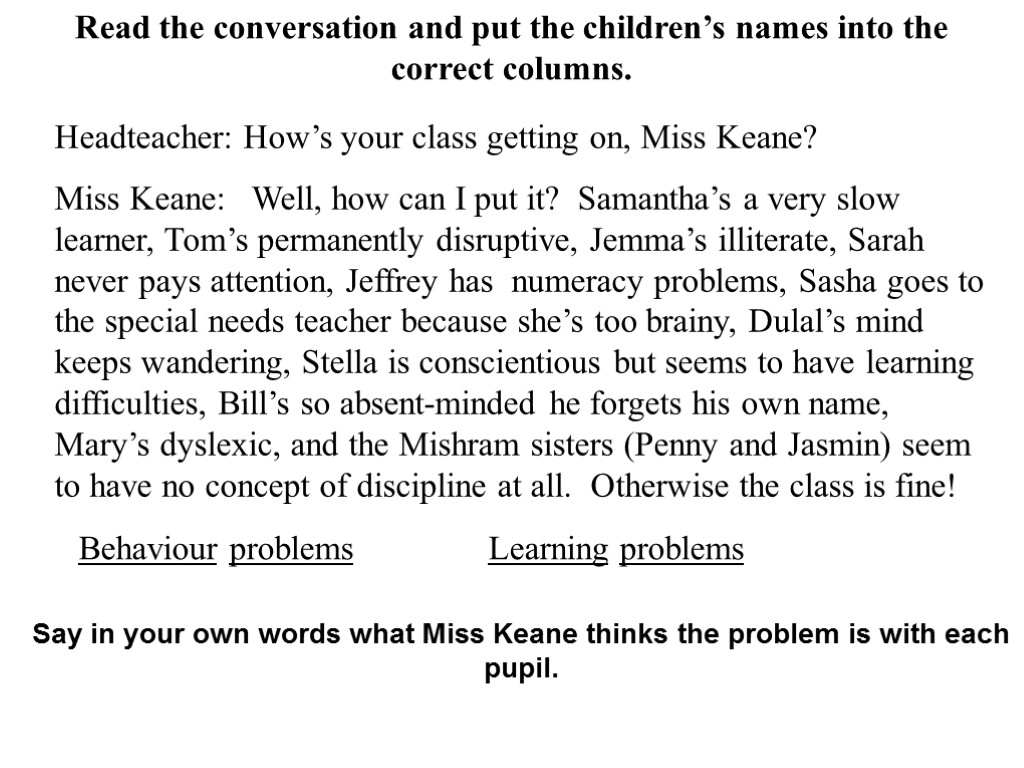

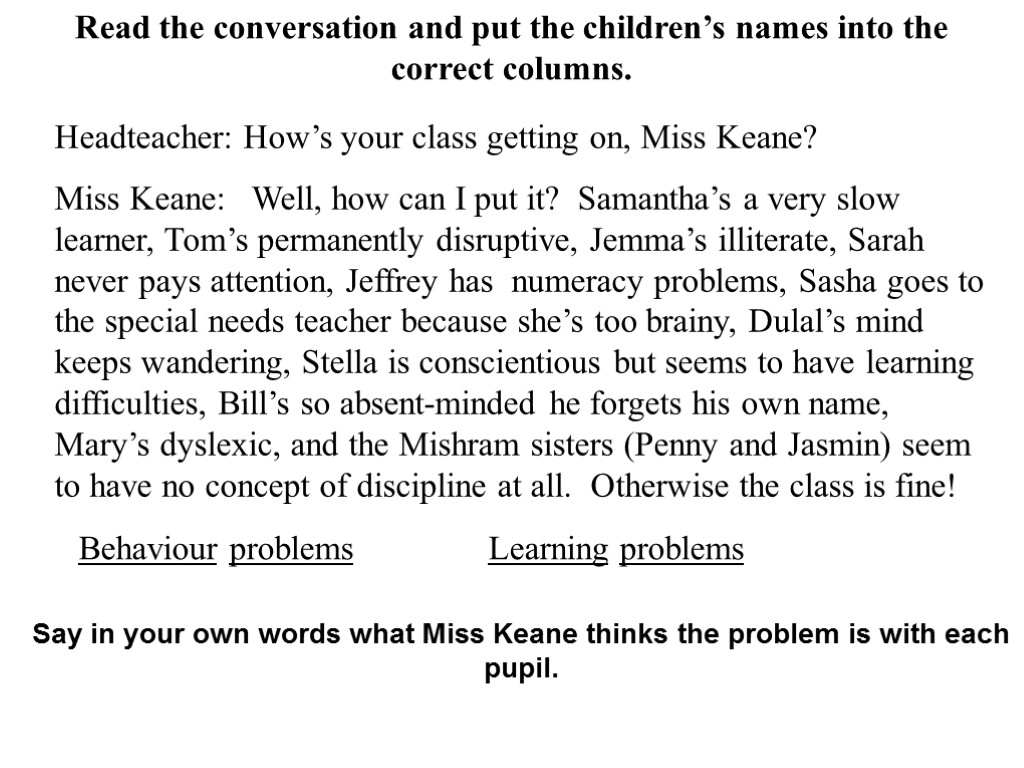

Read the conversation and put the children’s names into the correct columns. Headteacher: How’s your class getting on, Miss Keane? Miss Keane: Well, how can I put it? Samantha’s a very slow learner, Tom’s permanently disruptive, Jemma’s illiterate, Sarah never pays attention, Jeffrey has numeracy problems, Sasha goes to the special needs teacher because she’s too brainy, Dulal’s mind keeps wandering, Stella is conscientious but seems to have learning difficulties, Bill’s so absent-minded he forgets his own name, Mary’s dyslexic, and the Mishram sisters (Penny and Jasmin) seem to have no concept of discipline at all. Otherwise the class is fine! Behaviour problems Learning problems Say in your own words what Miss Keane thinks the problem is with each pupil.

Read the conversation and put the children’s names into the correct columns. Headteacher: How’s your class getting on, Miss Keane? Miss Keane: Well, how can I put it? Samantha’s a very slow learner, Tom’s permanently disruptive, Jemma’s illiterate, Sarah never pays attention, Jeffrey has numeracy problems, Sasha goes to the special needs teacher because she’s too brainy, Dulal’s mind keeps wandering, Stella is conscientious but seems to have learning difficulties, Bill’s so absent-minded he forgets his own name, Mary’s dyslexic, and the Mishram sisters (Penny and Jasmin) seem to have no concept of discipline at all. Otherwise the class is fine! Behaviour problems Learning problems Say in your own words what Miss Keane thinks the problem is with each pupil.

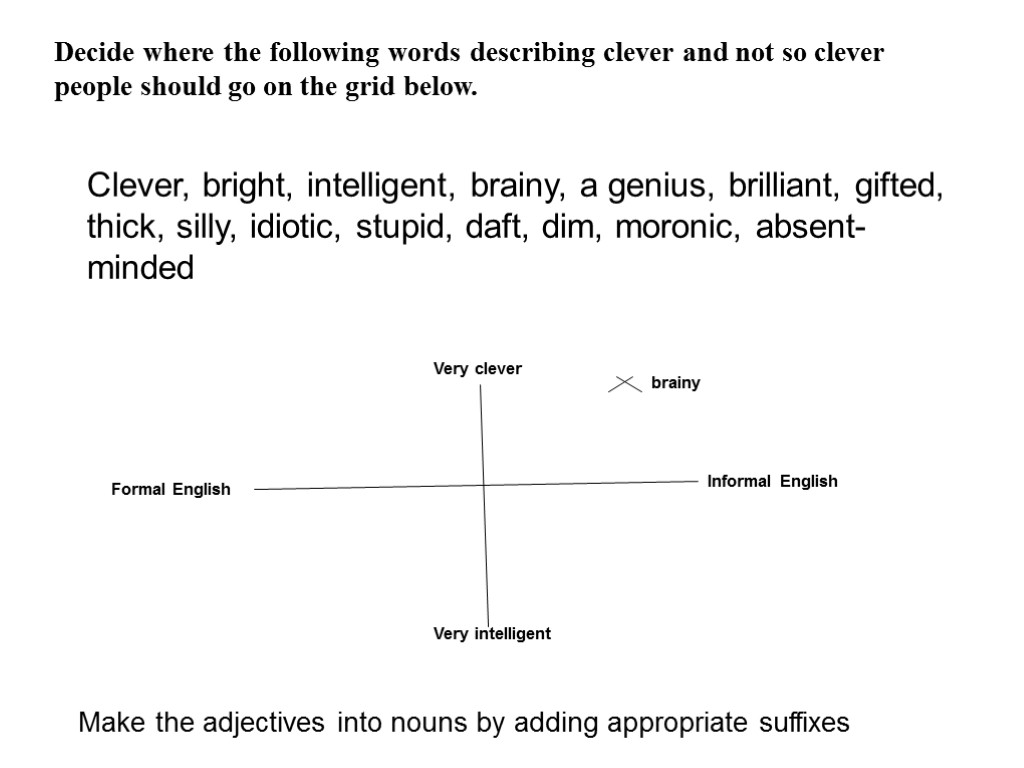

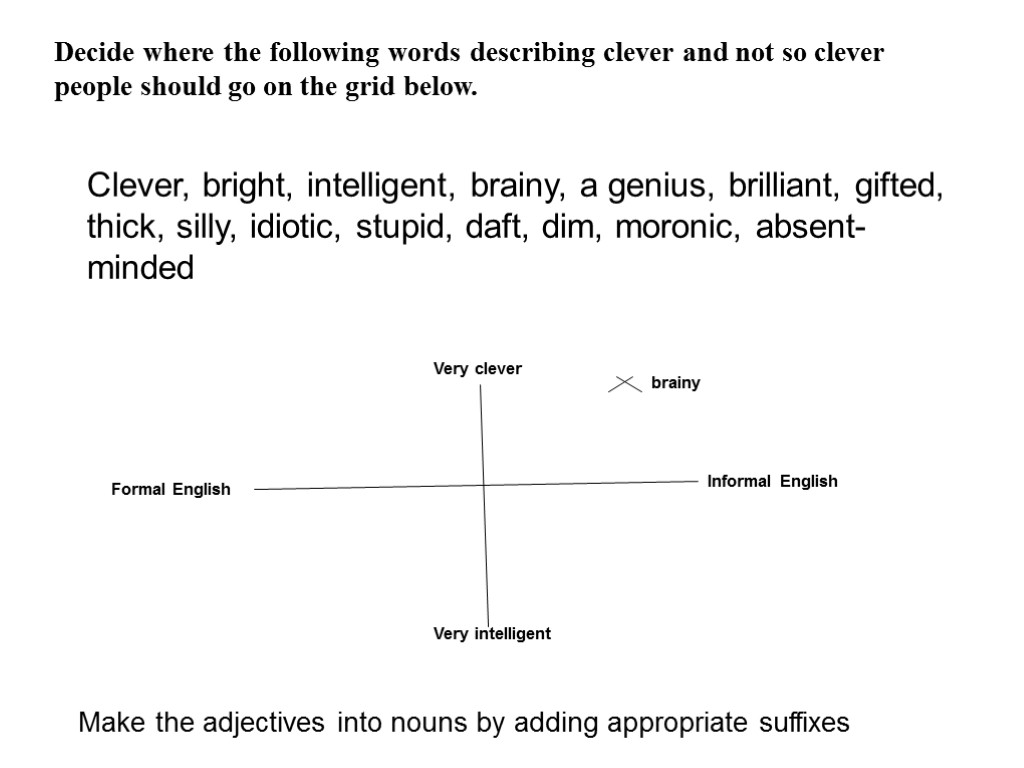

Decide where the following words describing clever and not so clever people should go on the grid below. Clever, bright, intelligent, brainy, a genius, brilliant, gifted, thick, silly, idiotic, stupid, daft, dim, moronic, absent-minded Very clever Very intelligent Formal English Informal English brainy Make the adjectives into nouns by adding appropriate suffixes

Decide where the following words describing clever and not so clever people should go on the grid below. Clever, bright, intelligent, brainy, a genius, brilliant, gifted, thick, silly, idiotic, stupid, daft, dim, moronic, absent-minded Very clever Very intelligent Formal English Informal English brainy Make the adjectives into nouns by adding appropriate suffixes

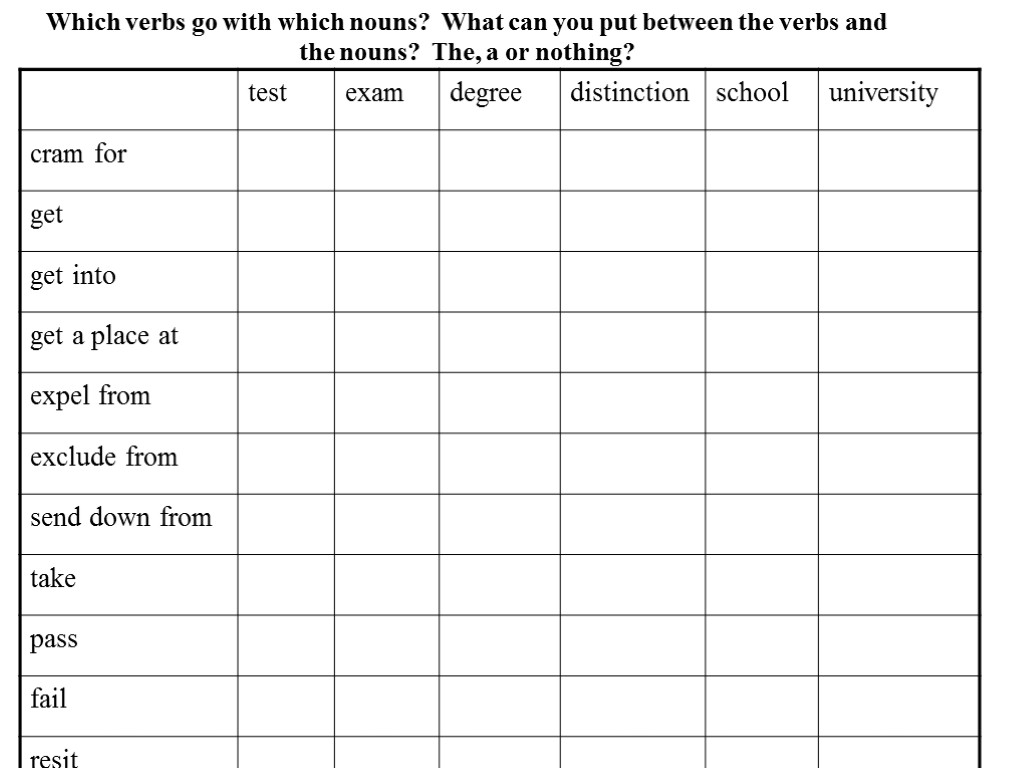

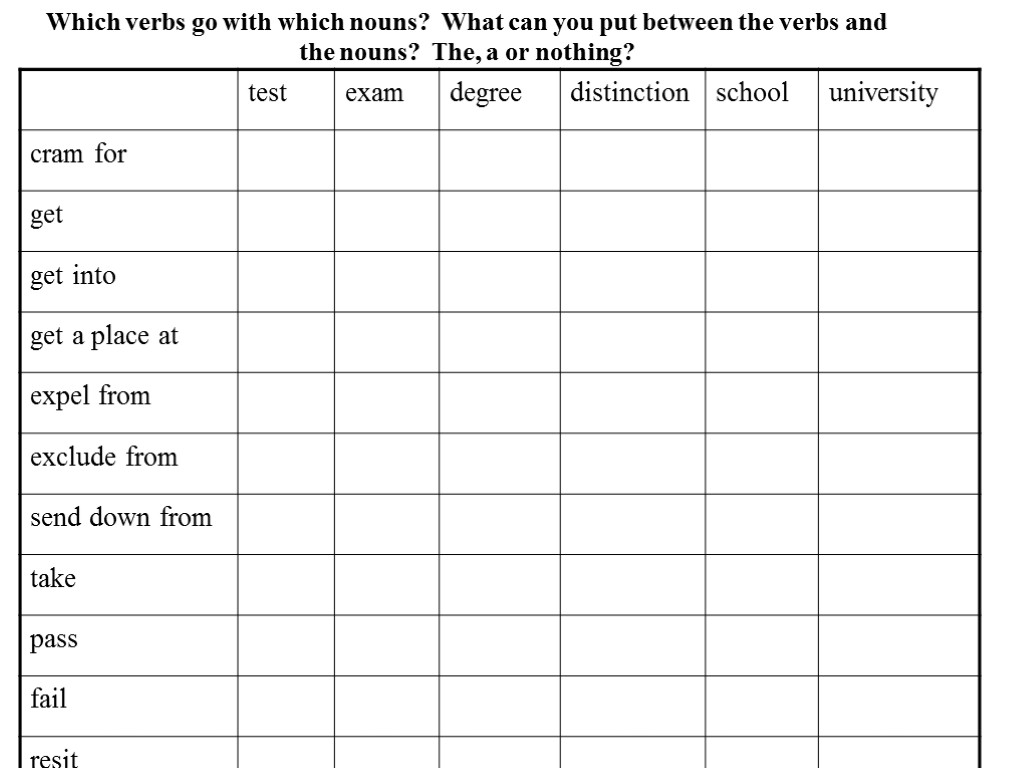

Which verbs go with which nouns? What can you put between the verbs and the nouns? The, a or nothing?

Which verbs go with which nouns? What can you put between the verbs and the nouns? The, a or nothing?

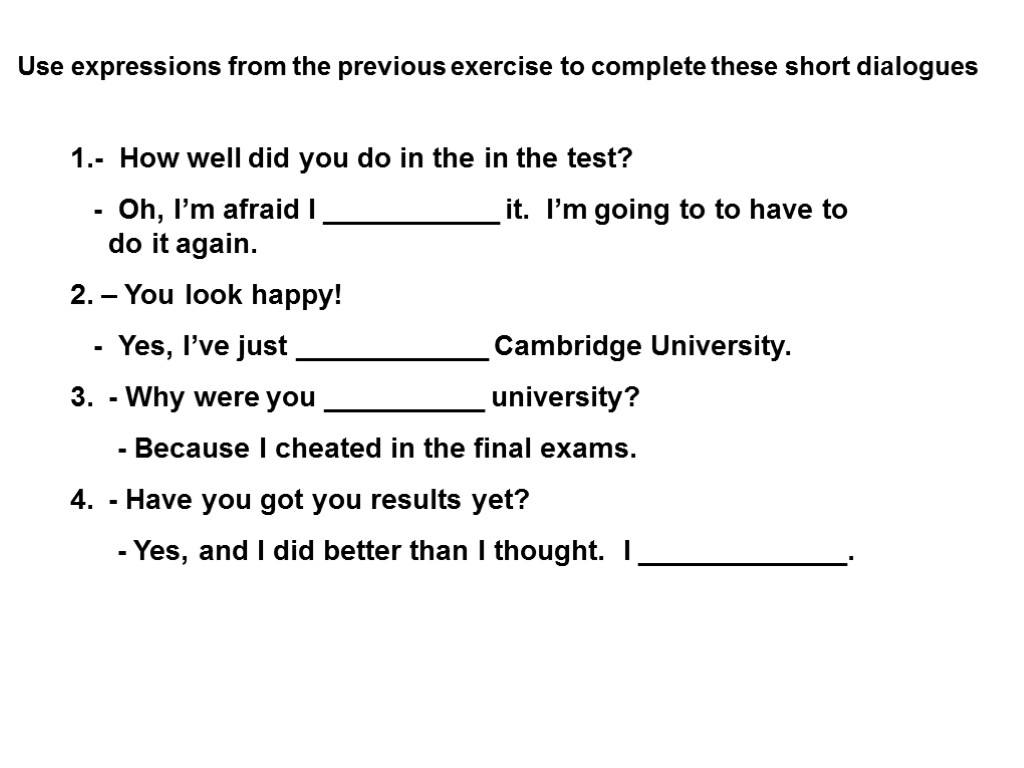

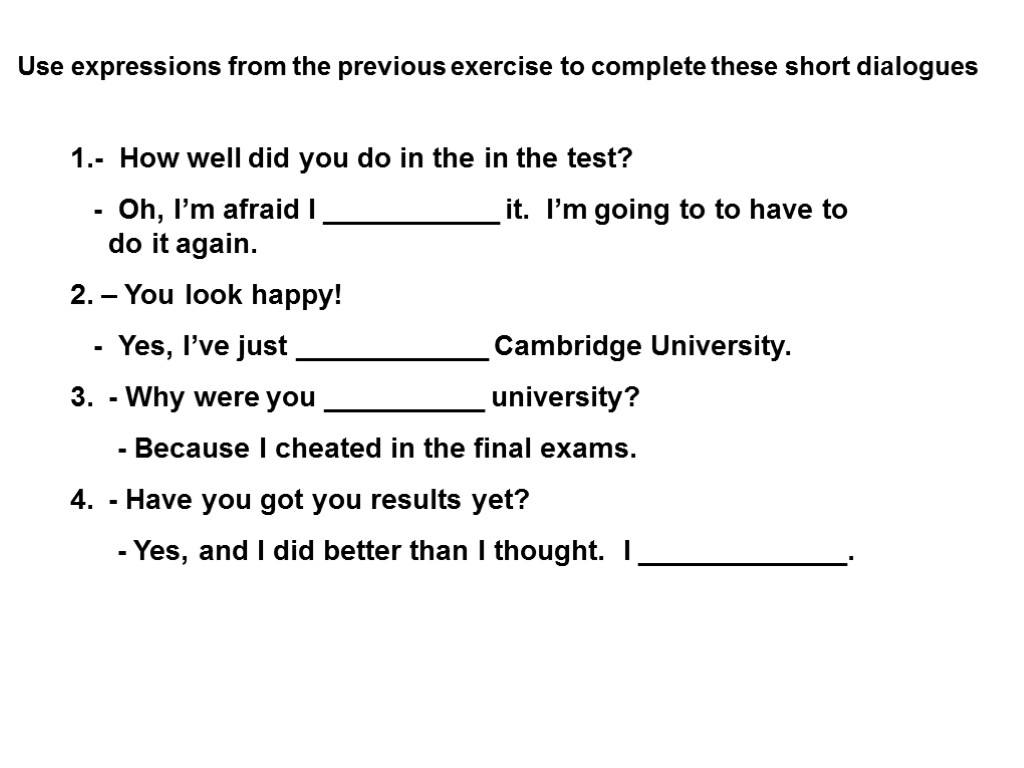

Use expressions from the previous exercise to complete these short dialogues 1.- How well did you do in the in the test? - Oh, I’m afraid I ___________ it. I’m going to to have to do it again. 2. – You look happy! - Yes, I’ve just ____________ Cambridge University. - Why were you __________ university? - Because I cheated in the final exams. - Have you got you results yet? - Yes, and I did better than I thought. I _____________.

Use expressions from the previous exercise to complete these short dialogues 1.- How well did you do in the in the test? - Oh, I’m afraid I ___________ it. I’m going to to have to do it again. 2. – You look happy! - Yes, I’ve just ____________ Cambridge University. - Why were you __________ university? - Because I cheated in the final exams. - Have you got you results yet? - Yes, and I did better than I thought. I _____________.

Primary and secondary education Schooling is compulsory for 12 years, for all children aged five to 16. There are two voluntary years of schooling thereafter. Children may attend either state-funded or fee-paying independent schools. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland the primary circle lasts from five to 11. generally speaking, children enter infant school, moving on to junior school (often in the same building) at the age of seven , and then on to secondary school at the age of 11. Roughly 90% of children receive their secondary education at comprehensive schools.

Primary and secondary education Schooling is compulsory for 12 years, for all children aged five to 16. There are two voluntary years of schooling thereafter. Children may attend either state-funded or fee-paying independent schools. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland the primary circle lasts from five to 11. generally speaking, children enter infant school, moving on to junior school (often in the same building) at the age of seven , and then on to secondary school at the age of 11. Roughly 90% of children receive their secondary education at comprehensive schools.

Those who want to stay on, can attend the two final years of secondary education, sometimes known in GB (for historical reasons) as’ the sixth form’. In many parts of the country, these two years are spent at a tertiary(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tertiary_education) or sixth-form college (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sixth_form_college) , which provides academic and vocational courses (FE). Two public academic examinations are set, one on completion of the compulsory cycle of education at the age of 16, and one on completion of the two voluntary years. At 16 pupils take the GCSE. During the two voluntary years of schooling, pupils specialize in two or three subjects and take the General Certificate of Education (GCE) Advanced Level, or ‘A level’ examination. Advanced Supplementary (AS) levels were introduced in 1989, to provide a wider range of subjects to study, a recognition that English education has traditionally been overly narrow.

Those who want to stay on, can attend the two final years of secondary education, sometimes known in GB (for historical reasons) as’ the sixth form’. In many parts of the country, these two years are spent at a tertiary(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tertiary_education) or sixth-form college (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sixth_form_college) , which provides academic and vocational courses (FE). Two public academic examinations are set, one on completion of the compulsory cycle of education at the age of 16, and one on completion of the two voluntary years. At 16 pupils take the GCSE. During the two voluntary years of schooling, pupils specialize in two or three subjects and take the General Certificate of Education (GCE) Advanced Level, or ‘A level’ examination. Advanced Supplementary (AS) levels were introduced in 1989, to provide a wider range of subjects to study, a recognition that English education has traditionally been overly narrow.

A new qualification was introduced in1992 for pupils who are skills, rather than academically oriented, the General National Vocational Qualification, known as GNVQ. This exam is taken at three distinct levels: the Foundation which has equivalent standing to low-grade passes in four subjects of GCSE; the Intermediate GNVQ which is equivalent to high-grade passes in four subjects of GCSE; and the Advanced GNVQ, equivalent to two passes at A level and acceptable for university entrance. The academic year usually begins in September, and is divided into three terms, with holidays for Christmas, Easter and for the month in August, although the exact days vary slightly from area to area. In addition each term there is a mid-term one-week holiday, known as ‘half-term’. Scotland, with a separate education tradition, has a slightly different system. Children stay in the primary cycle until the age of 12. they take the Scottish Certificate of Education at the age of 16 and, instead of A levels, they take the Scottish Higher Certificate examination which covers a wider area of study than the highly specialized A levels.

A new qualification was introduced in1992 for pupils who are skills, rather than academically oriented, the General National Vocational Qualification, known as GNVQ. This exam is taken at three distinct levels: the Foundation which has equivalent standing to low-grade passes in four subjects of GCSE; the Intermediate GNVQ which is equivalent to high-grade passes in four subjects of GCSE; and the Advanced GNVQ, equivalent to two passes at A level and acceptable for university entrance. The academic year usually begins in September, and is divided into three terms, with holidays for Christmas, Easter and for the month in August, although the exact days vary slightly from area to area. In addition each term there is a mid-term one-week holiday, known as ‘half-term’. Scotland, with a separate education tradition, has a slightly different system. Children stay in the primary cycle until the age of 12. they take the Scottish Certificate of Education at the age of 16 and, instead of A levels, they take the Scottish Higher Certificate examination which covers a wider area of study than the highly specialized A levels.

The story of British schools For largely historical reasons, the schools system is complicated, inconsistent and highly varied. Most of the oldest schools, of which the most famous are Eton, Harrow, Winchester and Westminster, are today independent, fee-paying, public schools for boys. Most of these were established to create a body of literate men to fulfill the administrative, political, legal and religious requirements of the late Middle Ages. From the 16th century onwards, many ‘grammar’ schools were established, often with large grants of money from wealthy men, in order to provide a local educational facility. From the 1870s local authorities were required to establish elementary schools, paid for by the local community, and to compel attendance by all boys and girls up to the age of 13. by 1900 almost total attendance was achieved. Each authority, with its locally elected councilors, was responsible for the curriculum. Although a general consensus developed concerning the major part of the school curriculum, a strong feeling of local control continued and interference by central government was resented.

The story of British schools For largely historical reasons, the schools system is complicated, inconsistent and highly varied. Most of the oldest schools, of which the most famous are Eton, Harrow, Winchester and Westminster, are today independent, fee-paying, public schools for boys. Most of these were established to create a body of literate men to fulfill the administrative, political, legal and religious requirements of the late Middle Ages. From the 16th century onwards, many ‘grammar’ schools were established, often with large grants of money from wealthy men, in order to provide a local educational facility. From the 1870s local authorities were required to establish elementary schools, paid for by the local community, and to compel attendance by all boys and girls up to the age of 13. by 1900 almost total attendance was achieved. Each authority, with its locally elected councilors, was responsible for the curriculum. Although a general consensus developed concerning the major part of the school curriculum, a strong feeling of local control continued and interference by central government was resented.

The 1944 Education Act introduced free compulsory secondary education. Almost all children attended one of two kinds of secondary school. The decision was made on the results obtained in the ’11 plus’ examination, taken in the last year of primary school. 80% of pupils went to ‘secondary modern’ schools where they were expected to obtain sufficient education for manual, skilled and clerical employment, but where academic expectations were modest. The remaining 20% went to grammar schools. Some of these were old foundations which now received a direct grant from central government, but the majority were funded through the local authority. Grammar school pupils were expected to go on to university or some other form of higher education. A large number of the grammar or ‘high’ schools were single sex. In addition there were and still continue to be schools under the management of the Church of England or the Roman Catholic Church, which usually own the school buildings. By the 1960s there was increasing criticism of this streaming of ability, particularly by the political Left. It was recognized that those pupils who failed the 11 plus exam were denied the chance to do better later.

The 1944 Education Act introduced free compulsory secondary education. Almost all children attended one of two kinds of secondary school. The decision was made on the results obtained in the ’11 plus’ examination, taken in the last year of primary school. 80% of pupils went to ‘secondary modern’ schools where they were expected to obtain sufficient education for manual, skilled and clerical employment, but where academic expectations were modest. The remaining 20% went to grammar schools. Some of these were old foundations which now received a direct grant from central government, but the majority were funded through the local authority. Grammar school pupils were expected to go on to university or some other form of higher education. A large number of the grammar or ‘high’ schools were single sex. In addition there were and still continue to be schools under the management of the Church of England or the Roman Catholic Church, which usually own the school buildings. By the 1960s there was increasing criticism of this streaming of ability, particularly by the political Left. It was recognized that those pupils who failed the 11 plus exam were denied the chance to do better later.

Early selection also reinforced the divisions of social class, and was wasteful of human potential. A government report in 1968 produced evidence that an expectation of failure became increasingly fulfilled, with secondary modern pupils aged 14 doing significantly worse than they had at the age of eight. Labour’s solution was to introduce a new type of school, the comprehensive, a combination of grammar and secondary modern under one roof, so that all the children could be continually assessed and given appropriate teaching. The measure caused much argument for two principal reasons. Many local authorities, particularly Conservative-controlled ones, did not wish to lose the excellence of their grammar schools, and many resented Labour’s interference in education, which was still considered a local responsibility. In practice the result of the reform was very mixed: the best comprehensives aimed at grammar school academic standards, while the worst sank to secondary modern ones.

Early selection also reinforced the divisions of social class, and was wasteful of human potential. A government report in 1968 produced evidence that an expectation of failure became increasingly fulfilled, with secondary modern pupils aged 14 doing significantly worse than they had at the age of eight. Labour’s solution was to introduce a new type of school, the comprehensive, a combination of grammar and secondary modern under one roof, so that all the children could be continually assessed and given appropriate teaching. The measure caused much argument for two principal reasons. Many local authorities, particularly Conservative-controlled ones, did not wish to lose the excellence of their grammar schools, and many resented Labour’s interference in education, which was still considered a local responsibility. In practice the result of the reform was very mixed: the best comprehensives aimed at grammar school academic standards, while the worst sank to secondary modern ones.

One unforeseen but damaging result was the refusal of many grammar schools to join the comprehensive experiment. Of the 174 direct-grant grammar schools, 119 decided to leave the state system rather than become comprehensive, and duly became independent fee-paying establishments. This had two effects. Grammar schools had provided an opportunity for children from all social backgrounds to excel academically at the same level as those attending fee-paying independent public schools. The loss of these schools had a demoralizing effect on the comprehensive experiment and damaged its chances of success, but led to a revival of independent schools at a time when they seemed to be slowly shrinking. The introduction of comprehensive schools thus unintentionally reinforced an educational elite which only the children of wealthier parents could hope to join. Comprehensive schools became the standard form of secondary education (other than in one or two isolated areas, where grammar schools and secondary moderns survived). However, except among the best comprehensives they lost for a while the excellence of the old garammar schools.

One unforeseen but damaging result was the refusal of many grammar schools to join the comprehensive experiment. Of the 174 direct-grant grammar schools, 119 decided to leave the state system rather than become comprehensive, and duly became independent fee-paying establishments. This had two effects. Grammar schools had provided an opportunity for children from all social backgrounds to excel academically at the same level as those attending fee-paying independent public schools. The loss of these schools had a demoralizing effect on the comprehensive experiment and damaged its chances of success, but led to a revival of independent schools at a time when they seemed to be slowly shrinking. The introduction of comprehensive schools thus unintentionally reinforced an educational elite which only the children of wealthier parents could hope to join. Comprehensive schools became the standard form of secondary education (other than in one or two isolated areas, where grammar schools and secondary moderns survived). However, except among the best comprehensives they lost for a while the excellence of the old garammar schools.

Alongside the introduction of comprehensives there was a move away from traditional teaching and discipline towards what was called ‘progressive’ education. This entailed a change from more formal teaching and factual learning to greater pupil participation and discussion, with greater emphasis on comprehension and less on the acquisition of knowledge. Not everyone approved, particularly on the political Right. There was increasing criticism of the lack of formal learning, and a demand to return to old-fashioned methods. From the 1960s there was also greater emphasis on education and training than ever before, with many colleges of further education established to provide technical or vocational training. However, British education remained too academic for the less able, and technical studies stayed weak, with the result that a large number of less academically able pupils left school without any skills or qualifications at all. The expansion of education led to increased expenditure, but it was substantially lower than that in other industrialized countries.

Alongside the introduction of comprehensives there was a move away from traditional teaching and discipline towards what was called ‘progressive’ education. This entailed a change from more formal teaching and factual learning to greater pupil participation and discussion, with greater emphasis on comprehension and less on the acquisition of knowledge. Not everyone approved, particularly on the political Right. There was increasing criticism of the lack of formal learning, and a demand to return to old-fashioned methods. From the 1960s there was also greater emphasis on education and training than ever before, with many colleges of further education established to provide technical or vocational training. However, British education remained too academic for the less able, and technical studies stayed weak, with the result that a large number of less academically able pupils left school without any skills or qualifications at all. The expansion of education led to increased expenditure, but it was substantially lower than that in other industrialized countries.

Perhaps the most serious failures were the continued high drop-out rate at the age of 16 and the low level of achievement in math and science among school-leavers. By the mid-1980s, while over 80% of pupils in the US and over 90% in Japan stayed on till the age of 18, barely one-third of British pupils did so. The Educational Reforms of the 1980s The Conservatives accused Labour of using education as a tool of social engineering at the expense of academic standards. The dominant right wing of the party argued that market forces should apply, and that the ‘consumers’, parents and employers, would have a better idea of what was needed than politicians or professional educationalists who lived in a rarefied and theoretical world. Through the Education Act (1986) and the Education Reform Act (1988) the Conservatives introduced the greatest reforms in schooling since 1944. Most educational experts saw good and bad features in these reforms. A theme running through most of them was the replacement of local authority control with greater central government power combined with greater parental choice, based on the philosophy of freedom of choice for the ‘consumer’.

Perhaps the most serious failures were the continued high drop-out rate at the age of 16 and the low level of achievement in math and science among school-leavers. By the mid-1980s, while over 80% of pupils in the US and over 90% in Japan stayed on till the age of 18, barely one-third of British pupils did so. The Educational Reforms of the 1980s The Conservatives accused Labour of using education as a tool of social engineering at the expense of academic standards. The dominant right wing of the party argued that market forces should apply, and that the ‘consumers’, parents and employers, would have a better idea of what was needed than politicians or professional educationalists who lived in a rarefied and theoretical world. Through the Education Act (1986) and the Education Reform Act (1988) the Conservatives introduced the greatest reforms in schooling since 1944. Most educational experts saw good and bad features in these reforms. A theme running through most of them was the replacement of local authority control with greater central government power combined with greater parental choice, based on the philosophy of freedom of choice for the ‘consumer’.

The main reform included the introduction of a National Curriculum making certain subjects, most notably science and one modern language, compulsory up to the age of 16. These had previously often been given up at the age of 13. But there was also unease that the compulsory curriculum, taking up over 70% of school time, would squeeeze out important wider areas of learning. Periodic formal assessments of progress, at the ages of seven, 11, 14 and 16 were also introduced. Independent fee-paying schools (see below), to witch most Conservative government ministers sent their children, were exempted from teaching according to the National Curriculum. Critics questioned why these schools did not have to follow the same national objectives. In keeping with its philosophy of consumer choice, the government gave parents the right to enroll their children – given appropriate age and aptitude – at any state school of their choice, within the limits of capacity. Parents already sent their children to the local school of their choice. The decision to publish schools’ examination results, however, gave parents a stark, but not necessarily well-informed, basis on which to choose the most appropriate school for their child. Increasingly parents sought access to the most successful nearby school in terms of examination results.

The main reform included the introduction of a National Curriculum making certain subjects, most notably science and one modern language, compulsory up to the age of 16. These had previously often been given up at the age of 13. But there was also unease that the compulsory curriculum, taking up over 70% of school time, would squeeeze out important wider areas of learning. Periodic formal assessments of progress, at the ages of seven, 11, 14 and 16 were also introduced. Independent fee-paying schools (see below), to witch most Conservative government ministers sent their children, were exempted from teaching according to the National Curriculum. Critics questioned why these schools did not have to follow the same national objectives. In keeping with its philosophy of consumer choice, the government gave parents the right to enroll their children – given appropriate age and aptitude – at any state school of their choice, within the limits of capacity. Parents already sent their children to the local school of their choice. The decision to publish schools’ examination results, however, gave parents a stark, but not necessarily well-informed, basis on which to choose the most appropriate school for their child. Increasingly parents sought access to the most successful nearby school in terms of examination results.

Far from being able to exercise their choice, large numbers of parents were now frustrated in their choice. Overall, in 1996 20% of parents failed to obtain their first choice of school. In London the level was 40% undermining the whole policy of ‘parental choice’ and encouraging only the crudest view of educational standards. Schools found themselves competing rather than cooperating and some schools, for example in deprived urban areas, faced a downward spiral of declining enrolment followed by reduced budgets. Thus the market offered winners and losers: an improved system for the brighter or more fortunate pupils, but a worse one for the ‘bottom’ 40%. Schools in deprived parts of cities acquired reputations as ‘sink’ schools. As one education journalist wrote in 1997, ‘There is a clear hierarchy of schools: private, grammar, comprehensives with plenty of nice middle-class children, comprehensives with fewer nice middle-class children and so on.’ In 1988 schools were given the power to opt out of local authority control, if a majority of parents wanted this. But most schools valued the guidance and support of the local education authority, and by 1997 only 18% of English secondary schools had chosen this new ‘grant-maintained status.

Far from being able to exercise their choice, large numbers of parents were now frustrated in their choice. Overall, in 1996 20% of parents failed to obtain their first choice of school. In London the level was 40% undermining the whole policy of ‘parental choice’ and encouraging only the crudest view of educational standards. Schools found themselves competing rather than cooperating and some schools, for example in deprived urban areas, faced a downward spiral of declining enrolment followed by reduced budgets. Thus the market offered winners and losers: an improved system for the brighter or more fortunate pupils, but a worse one for the ‘bottom’ 40%. Schools in deprived parts of cities acquired reputations as ‘sink’ schools. As one education journalist wrote in 1997, ‘There is a clear hierarchy of schools: private, grammar, comprehensives with plenty of nice middle-class children, comprehensives with fewer nice middle-class children and so on.’ In 1988 schools were given the power to opt out of local authority control, if a majority of parents wanted this. But most schools valued the guidance and support of the local education authority, and by 1997 only 18% of English secondary schools had chosen this new ‘grant-maintained status.

Secondary schools and larger primary schools were also given responsibility for managing their own budgets. Each school board of governors, composed of parents and local authority appointees, was given greatly increased responsibility, including the ‘hiring and firing’ of staff. Once again, schools with support from highly educated parents did better than those in deprived areas. The additional work added greatly to the load carried by the schools principals, while still denying them full executive powers over their staff. By 1996 head teachers were resigning in record numbers as a result of stress. Inner London schools, for example, were notorious for discipline problems. In 1995 40% of inner London headships were readvertised. These reforms were insufficient to change the face of British education. Too many children left school with inadequate basic skills in literacy, numeracy, science and technology. Although A level science pupils are among the best internationally, they are a small group. Internationally Britain’s standard of science remains an embarrassment.

Secondary schools and larger primary schools were also given responsibility for managing their own budgets. Each school board of governors, composed of parents and local authority appointees, was given greatly increased responsibility, including the ‘hiring and firing’ of staff. Once again, schools with support from highly educated parents did better than those in deprived areas. The additional work added greatly to the load carried by the schools principals, while still denying them full executive powers over their staff. By 1996 head teachers were resigning in record numbers as a result of stress. Inner London schools, for example, were notorious for discipline problems. In 1995 40% of inner London headships were readvertised. These reforms were insufficient to change the face of British education. Too many children left school with inadequate basic skills in literacy, numeracy, science and technology. Although A level science pupils are among the best internationally, they are a small group. Internationally Britain’s standard of science remains an embarrassment.

One reason is that British children spend a lot of time watching TV or playing computer games, and there is an established negative association between these habits and high achievement in science and math. The teaching cadre suffered from low morale, discipline problems, poor pay, inadequate training and the increased workload resulting from the reforms. Many teachers took early retirement or sought alternative employment. By 1989 there were as many trained teachers not teaching as teaching. Education under Labour Education was the central theme of the new Labour government. It promised a huge range of improvements: high-quality education for all four-year-olds whose parents wanted it and lower pupil-teacher ratios, in particular that children up to the age of eight children would never be in classes of over 30 pupils. It also declared that all children at primary school would spend one hour each day on reading and writing, and another hour each day on numeracy, the basic skills for all employment.

One reason is that British children spend a lot of time watching TV or playing computer games, and there is an established negative association between these habits and high achievement in science and math. The teaching cadre suffered from low morale, discipline problems, poor pay, inadequate training and the increased workload resulting from the reforms. Many teachers took early retirement or sought alternative employment. By 1989 there were as many trained teachers not teaching as teaching. Education under Labour Education was the central theme of the new Labour government. It promised a huge range of improvements: high-quality education for all four-year-olds whose parents wanted it and lower pupil-teacher ratios, in particular that children up to the age of eight children would never be in classes of over 30 pupils. It also declared that all children at primary school would spend one hour each day on reading and writing, and another hour each day on numeracy, the basic skills for all employment.