0df9a4bdcb197836322d22e78958769a.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 39

ECON 102. 004 – Principles of Microeconomics S&W, Chapter 2 Thinking Like an Economist Instructor: Mehmet S. Tosun, Ph. D. Department of Economics University of Nevada, Reno 1

ECON 102. 004 – Principles of Microeconomics S&W, Chapter 2 Thinking Like an Economist Instructor: Mehmet S. Tosun, Ph. D. Department of Economics University of Nevada, Reno 1

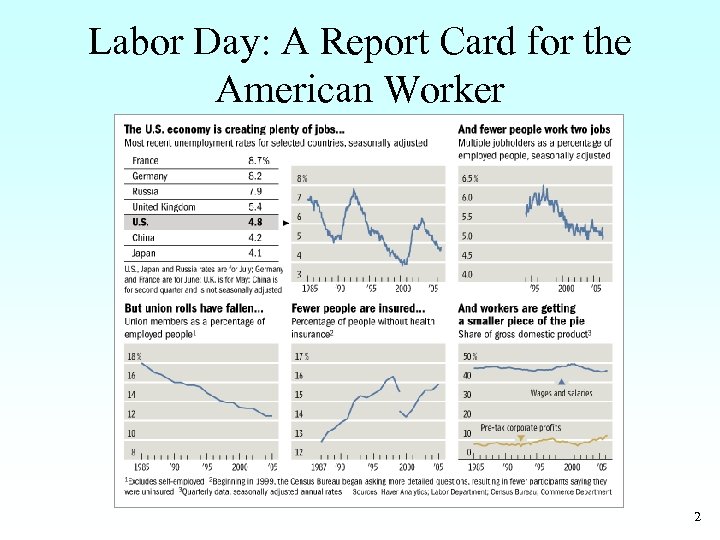

Labor Day: A Report Card for the American Worker 2

Labor Day: A Report Card for the American Worker 2

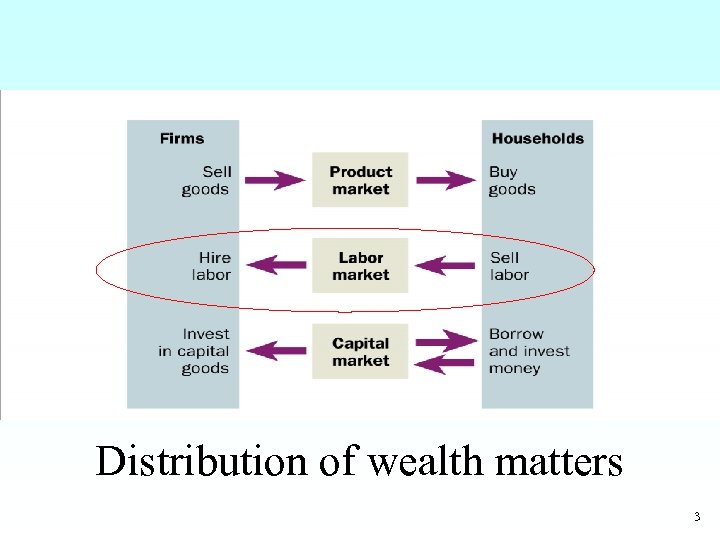

Distribution of wealth matters 3

Distribution of wealth matters 3

American Workers Take Less Vacation • Americans take about four weeks a year for vacation and holidays, according to the OECD • The French take about seven weeks • Italians take around eight weeks 4

American Workers Take Less Vacation • Americans take about four weeks a year for vacation and holidays, according to the OECD • The French take about seven weeks • Italians take around eight weeks 4

Homer’s Attitude Towards Management and Labor Homer's response to an ultimatum to come to work today or don't bother to come in on Monday "Woo hoo! A four day weekend!" 5

Homer’s Attitude Towards Management and Labor Homer's response to an ultimatum to come to work today or don't bother to come in on Monday "Woo hoo! A four day weekend!" 5

Lecture Outline • Thinking like an economist • Basic competitive model • Role of incentives, property rights, prices and profit in market economy • Alternatives to market system • Basic tools of economists 6

Lecture Outline • Thinking like an economist • Basic competitive model • Role of incentives, property rights, prices and profit in market economy • Alternatives to market system • Basic tools of economists 6

Thinking Like an Economist • Economics trains you to. . – Think in terms of alternatives. – Evaluate the cost of individual and social choices. – Examine and understand how certain events and issues are related.

Thinking Like an Economist • Economics trains you to. . – Think in terms of alternatives. – Evaluate the cost of individual and social choices. – Examine and understand how certain events and issues are related.

Thinking Like an Economist • Every field of study has its own terminology – Mathematics • integrals axioms vector spaces – Psychology • ego id cognitive dissonance – Law • promissory torts venues – Economics • supply opportunity cost elasticity consumer surplus demand comparative advantage deadweight loss 8

Thinking Like an Economist • Every field of study has its own terminology – Mathematics • integrals axioms vector spaces – Psychology • ego id cognitive dissonance – Law • promissory torts venues – Economics • supply opportunity cost elasticity consumer surplus demand comparative advantage deadweight loss 8

The Scientific Method: Observation, Theory, and More Observation • Uses abstract models to help explain how a complex, real world operates. • Develops theories, collects, and analyzes data to evaluate theories.

The Scientific Method: Observation, Theory, and More Observation • Uses abstract models to help explain how a complex, real world operates. • Develops theories, collects, and analyzes data to evaluate theories.

The Role of Assumptions • Economists make assumptions in order to make the world easier to understand. • The art in scientific thinking is deciding which assumptions to make. • Economists use different assumptions to answer different questions. 10

The Role of Assumptions • Economists make assumptions in order to make the world easier to understand. • The art in scientific thinking is deciding which assumptions to make. • Economists use different assumptions to answer different questions. 10

THE ECONOMIST AS POLICY ADVISOR • When economists are trying to explain the world, they are scientists. • When economists are trying to change the world, they are policy advisors.

THE ECONOMIST AS POLICY ADVISOR • When economists are trying to explain the world, they are scientists. • When economists are trying to change the world, they are policy advisors.

Economists in Washington • . . . serve as advisers in the policymaking process of the three branches of government: – Legislative – Executive – Judicial

Economists in Washington • . . . serve as advisers in the policymaking process of the three branches of government: – Legislative – Executive – Judicial

The Basic Competitive Model • • Rational consumers Profit‑maximizing firms Competitive markets Government is ignored for now 13

The Basic Competitive Model • • Rational consumers Profit‑maximizing firms Competitive markets Government is ignored for now 13

Rational Consumers • Scarcity forces us to make choices. • Economists assume individuals and firms make choices rationally: – Pursue what they see as their own self‑interest – Weigh costs and benefits as they see them – If benefits > costs, take the action – However, different people have different interests • Economists do not judge people's preferences. 14

Rational Consumers • Scarcity forces us to make choices. • Economists assume individuals and firms make choices rationally: – Pursue what they see as their own self‑interest – Weigh costs and benefits as they see them – If benefits > costs, take the action – However, different people have different interests • Economists do not judge people's preferences. 14

Profit‑Maximizing Firms • For firms; rationality means maximizing profits. • Profit = revenue costs • Revenue = p. Q, where p = price and Q = quantity • Profit = p. Q costs 15

Profit‑Maximizing Firms • For firms; rationality means maximizing profits. • Profit = revenue costs • Revenue = p. Q, where p = price and Q = quantity • Profit = p. Q costs 15

Information Costs • Individuals and firms often make decisions with little or no information. – Is the car a lemon? – Will the worker be productive? – Will the investment be profitable? • Rationality applies to acquiring information to answer these questions. • If the benefit of more information > the cost of acquiring the information, the information is acquired. 16

Information Costs • Individuals and firms often make decisions with little or no information. – Is the car a lemon? – Will the worker be productive? – Will the investment be profitable? • Rationality applies to acquiring information to answer these questions. • If the benefit of more information > the cost of acquiring the information, the information is acquired. 16

Competitive Markets • Many firms sell identical products to many consumers. • Firms and consumers are price takers in competitive markets. • Firms provide as much output as consumers will buy. • Each firm can sell as much as it wants: the size of the firm is small compared to the size of the market. • If firms charge a price higher than the market price, they lose all their customers. • All firms in the industry charge the same price. 17

Competitive Markets • Many firms sell identical products to many consumers. • Firms and consumers are price takers in competitive markets. • Firms provide as much output as consumers will buy. • Each firm can sell as much as it wants: the size of the firm is small compared to the size of the market. • If firms charge a price higher than the market price, they lose all their customers. • All firms in the industry charge the same price. 17

The Basic Competitive Model as a Benchmark • Combines self‑interested consumers, profit‑maximizing firms, and competition • The model is tested by comparing its predictions with actual markets. • Economists believe this model can provide answers to the four basic questions: – – What is produced, and in what quantities? How are goods produced? For whom are those goods produced? Who decides the answers to the first three questions, and how? • Government is not needed to answer these questions in the basic competitive model. 18

The Basic Competitive Model as a Benchmark • Combines self‑interested consumers, profit‑maximizing firms, and competition • The model is tested by comparing its predictions with actual markets. • Economists believe this model can provide answers to the four basic questions: – – What is produced, and in what quantities? How are goods produced? For whom are those goods produced? Who decides the answers to the first three questions, and how? • Government is not needed to answer these questions in the basic competitive model. 18

Efficiency in the Basic Competitive Model • The basic competitive model is efficient. – That means scarce resources are not wasted. – It is not possible to produce more of one good without producing less of another good. – It is not possible to make one person better off without making someone else worse off. – Known as Pareto efficiency 19

Efficiency in the Basic Competitive Model • The basic competitive model is efficient. – That means scarce resources are not wasted. – It is not possible to produce more of one good without producing less of another good. – It is not possible to make one person better off without making someone else worse off. – Known as Pareto efficiency 19

Income • Income is an incentive for consumers, workers, investors, and firms. • Consumer or household income is personal income. • Firm income is revenue divided between costs and profit. 20

Income • Income is an incentive for consumers, workers, investors, and firms. • Consumer or household income is personal income. • Firm income is revenue divided between costs and profit. 20

Property Rights • The right of the owner to use and sell his or her property. • With well‑defined property rights, access is excludable, rivalrous, and transferable. • A combination of freedom and responsibility is crucial to markets. – Freedom: Individuals and firms must be free to be creative and try new techniques. – Responsibility: Individuals must reap the reward if successful or suffer the losses if not. 21

Property Rights • The right of the owner to use and sell his or her property. • With well‑defined property rights, access is excludable, rivalrous, and transferable. • A combination of freedom and responsibility is crucial to markets. – Freedom: Individuals and firms must be free to be creative and try new techniques. – Responsibility: Individuals must reap the reward if successful or suffer the losses if not. 21

Incentives versus Equality • Well‑defined property rights permit incentives to provide rewards and costs. • If rewards are tied to performance, then a problem arises when many people help to produce a good or service. – Who contributed what? – Who are the most productive employees; is the hot salesperson good or just lucky? 22

Incentives versus Equality • Well‑defined property rights permit incentives to provide rewards and costs. • If rewards are tied to performance, then a problem arises when many people help to produce a good or service. – Who contributed what? – Who are the most productive employees; is the hot salesperson good or just lucky? 22

Performance‑Based Compensation • Even if pay can be tied to performance, how does one measure performance? • If compensation is tied to performance, this leads to inequality since different people perform differently. – However, if this inequality is from luck, would another criterion of compensation do "better"? – Some economists hold equality as a value in its own right. 23

Performance‑Based Compensation • Even if pay can be tied to performance, how does one measure performance? • If compensation is tied to performance, this leads to inequality since different people perform differently. – However, if this inequality is from luck, would another criterion of compensation do "better"? – Some economists hold equality as a value in its own right. 23

When Property Rights Fail • In many cases property rights are not clearly defined. • This causes problems with the efficient allocation of resources. – Example: • In the early days of radio broadcasting, many broadcasters used the same frequency and jammed each other's broadcasts. – Property rights were ill defined; anyone could infringe on others' uses of the airwaves. – The government established a licensing system, which created well‑defined property rights. • Broadcasters became the sole owners of frequencies. • They could sue to protect their property. 24

When Property Rights Fail • In many cases property rights are not clearly defined. • This causes problems with the efficient allocation of resources. – Example: • In the early days of radio broadcasting, many broadcasters used the same frequency and jammed each other's broadcasts. – Property rights were ill defined; anyone could infringe on others' uses of the airwaves. – The government established a licensing system, which created well‑defined property rights. • Broadcasters became the sole owners of frequencies. • They could sue to protect their property. 24

Nontransferable Property Rights • Sometimes the ability to dispose of property is restricted by law; some property rights are not transferable. • Water rights cannot, in general, be sold. – If water rights were sellable, ranchers could sell water to thirsty cities. – Both benefit: • Ranchers earn extra income. • Cities pay less for water. 25

Nontransferable Property Rights • Sometimes the ability to dispose of property is restricted by law; some property rights are not transferable. • Water rights cannot, in general, be sold. – If water rights were sellable, ranchers could sell water to thirsty cities. – Both benefit: • Ranchers earn extra income. • Cities pay less for water. 25

Consensus among Economists on Incentives • Providing appropriate incentives is a fundamental economic problem. • Profits provide incentives for firms to produce the goods individuals want. • Wages provide incentives for individuals to work. • Property rights provide people with important incentives, to invest, save, and to put their assets to the best possible use. 26

Consensus among Economists on Incentives • Providing appropriate incentives is a fundamental economic problem. • Profits provide incentives for firms to produce the goods individuals want. • Wages provide incentives for individuals to work. • Property rights provide people with important incentives, to invest, save, and to put their assets to the best possible use. 26

Alternative to the Price System • In a market, those individuals who are willing to pay the most receive the good. • The allocation of goods is based on a price system. • Rationing is an alternative to price allocations. 27

Alternative to the Price System • In a market, those individuals who are willing to pay the most receive the good. • The allocation of goods is based on a price system. • Rationing is an alternative to price allocations. 27

Types of Rationing • Queues: If the price of a good or service is set below market price, customers may have to wait in line to buy it. – The wasted time is a waste of resources. – There are long lines for food in countries with price controls. • Lottery: Customers are picked at random. • Coupons: One must pay both the market price and a coupon to buy a good. – Coupon rationing is favored during wartime. – Often goods and coupons may be traded in a black market. 28

Types of Rationing • Queues: If the price of a good or service is set below market price, customers may have to wait in line to buy it. – The wasted time is a waste of resources. – There are long lines for food in countries with price controls. • Lottery: Customers are picked at random. • Coupons: One must pay both the market price and a coupon to buy a good. – Coupon rationing is favored during wartime. – Often goods and coupons may be traded in a black market. 28

The Inefficiency of Rationing • Those who are most willing to pay for the rationed good or service do not necessarily get the good or service. 29

The Inefficiency of Rationing • Those who are most willing to pay for the rationed good or service do not necessarily get the good or service. 29

Opportunity Sets • Opportunity sets are combinations of goods. • Due to the scarcity of money or time, not all combinations of goods are attainable. 30

Opportunity Sets • Opportunity sets are combinations of goods. • Due to the scarcity of money or time, not all combinations of goods are attainable. 30

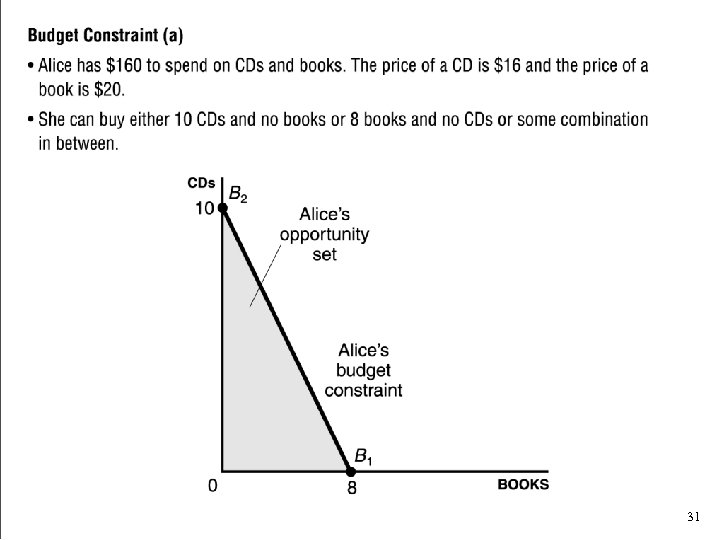

Budget Constraint (a) • Alice has $160 to spend on CDs and books. The price of a CD is $16 and the price of a book is $20. • She can buy either 10 CDs and no books or 8 books and no CDs or some combination in between. 31

Budget Constraint (a) • Alice has $160 to spend on CDs and books. The price of a CD is $16 and the price of a book is $20. • She can buy either 10 CDs and no books or 8 books and no CDs or some combination in between. 31

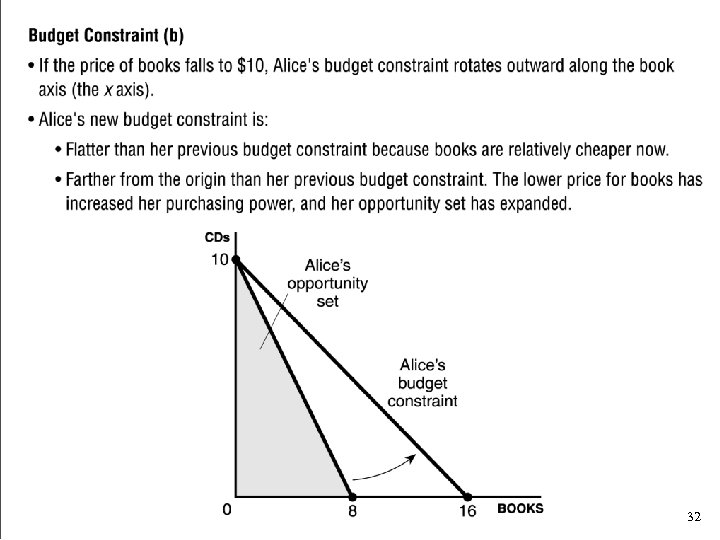

Budget Constraint (b) • If the price of books falls to $10, Alice's budget constraint rotates outward along the book axis (the x axis). • Alice's new budget constraint is: – Flatter than her previous budget constraint because books are relatively cheaper now. – Farther from the origin than her previous budget constraint. The lower price for books has increased her purchasing power, and her opportunity set has 32

Budget Constraint (b) • If the price of books falls to $10, Alice's budget constraint rotates outward along the book axis (the x axis). • Alice's new budget constraint is: – Flatter than her previous budget constraint because books are relatively cheaper now. – Farther from the origin than her previous budget constraint. The lower price for books has increased her purchasing power, and her opportunity set has 32

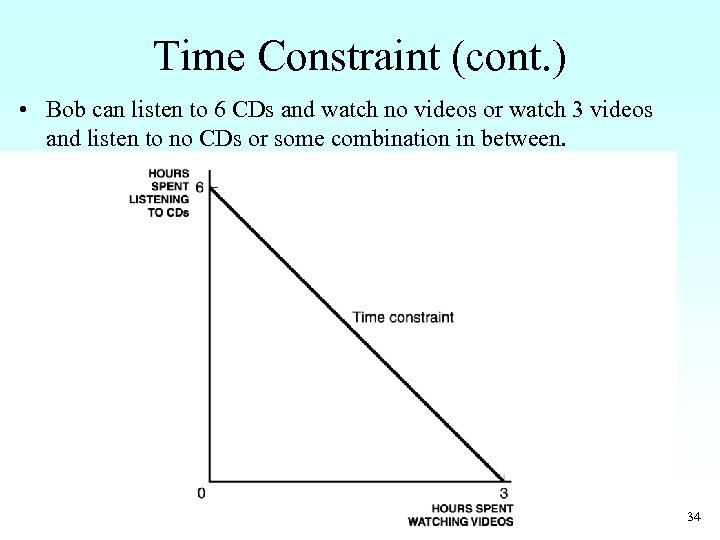

Time Constraint • Bob has 6 hours of free time every day after we subtract time spent: – Working – Getting ready for work – Commuting – Sleeping • It takes Bob 1 hour to listen to a CD and 2 hours to watch a video. 33

Time Constraint • Bob has 6 hours of free time every day after we subtract time spent: – Working – Getting ready for work – Commuting – Sleeping • It takes Bob 1 hour to listen to a CD and 2 hours to watch a video. 33

Time Constraint (cont. ) • Bob can listen to 6 CDs and watch no videos or watch 3 videos and listen to no CDs or some combination in between. 34

Time Constraint (cont. ) • Bob can listen to 6 CDs and watch no videos or watch 3 videos and listen to no CDs or some combination in between. 34

The Production Possibilities Curve (PPC) • The PPC is a producer's constraint. • With a given quantity of inputs, a firm can only produce certain quantities of goods. • Guns versus butter • The boundary of what can be produced is the production possibilities curve. 35

The Production Possibilities Curve (PPC) • The PPC is a producer's constraint. • With a given quantity of inputs, a firm can only produce certain quantities of goods. • Guns versus butter • The boundary of what can be produced is the production possibilities curve. 35

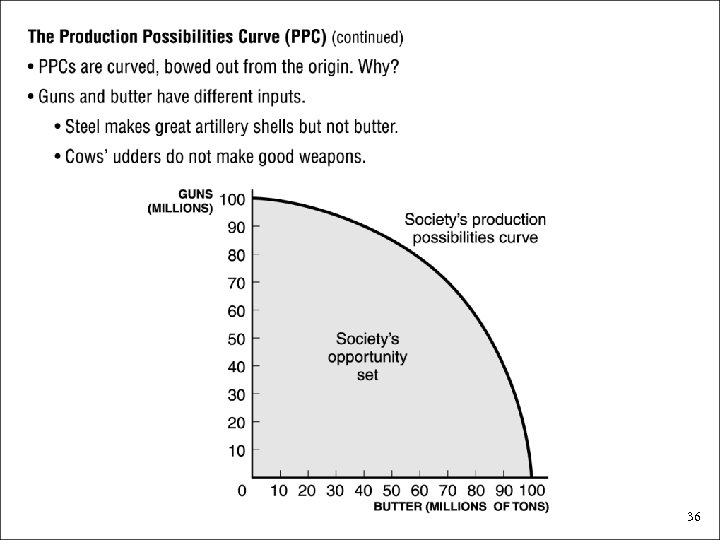

The Production Possibilities Curve (PPC) (continued) • PPCs are curved, bowed out from the origin. Why? • Guns and butter have different inputs. – Steel makes great artillery shells but not butter. – Cows' udders do not make good weapons. 36

The Production Possibilities Curve (PPC) (continued) • PPCs are curved, bowed out from the origin. Why? • Guns and butter have different inputs. – Steel makes great artillery shells but not butter. – Cows' udders do not make good weapons. 36

Optimal Production on the PPC • Inside the PPC, a firm can produce more of both goods by moving out to the curve. – So points interior to the curve are not efficient. – Economists want to know the source of these inefficiencies, what resources are unemployed. • The optimal production mix is always on the curve. 37

Optimal Production on the PPC • Inside the PPC, a firm can produce more of both goods by moving out to the curve. – So points interior to the curve are not efficient. – Economists want to know the source of these inefficiencies, what resources are unemployed. • The optimal production mix is always on the curve. 37

Costs • The opportunity cost is the value of the next best alternative when one makes a choice. – Time and budget constraints and production possibilities curves illustrate the cost of one option in terms of the other: opportunity cost. – The cost of an education is: • • • Tuition Room and board Books Travel expenses Opportunity cost: lost earnings from not working for four years • The opportunity cost is often used by the government when it considers the costs and benefits of a program. 38

Costs • The opportunity cost is the value of the next best alternative when one makes a choice. – Time and budget constraints and production possibilities curves illustrate the cost of one option in terms of the other: opportunity cost. – The cost of an education is: • • • Tuition Room and board Books Travel expenses Opportunity cost: lost earnings from not working for four years • The opportunity cost is often used by the government when it considers the costs and benefits of a program. 38

Sunk and Marginal Costs • Sunk costs are non-recoverable expenditures. – Sunk costs play no role in deciding whether to continue an activity. • Marginal costs are the extra costs of small changes in production or consumption. – Marginal costs are the additional costs of producing or consuming one additional unit. – Monthly electric bills are marginal costs. 39

Sunk and Marginal Costs • Sunk costs are non-recoverable expenditures. – Sunk costs play no role in deciding whether to continue an activity. • Marginal costs are the extra costs of small changes in production or consumption. – Marginal costs are the additional costs of producing or consuming one additional unit. – Monthly electric bills are marginal costs. 39