29193a91a1e5aeb4e776373b25240485.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 82

ECE 243 The NIOS ISA 1

ECE 243 The NIOS ISA 1

The NIOS II ISA • Memory: – 32 -bit address space • an address is 32 bits – Byte-addressable • each address represents one byte – Hence: 232 addresses = 232 bytes = 4 GB – Note: means NIOS capable of addressing 4 GB • doesn’t mean DE 2 has that much memory in it • INSTRUCTION DATATYPES – – defined by the ISA (in C: unsigned, char, long etc) byte (b) = 8 bits Half-word (h) = 2 bytes = 16 bits word (w) = 4 bytes = 32 bits 2

The NIOS II ISA • Memory: – 32 -bit address space • an address is 32 bits – Byte-addressable • each address represents one byte – Hence: 232 addresses = 232 bytes = 4 GB – Note: means NIOS capable of addressing 4 GB • doesn’t mean DE 2 has that much memory in it • INSTRUCTION DATATYPES – – defined by the ISA (in C: unsigned, char, long etc) byte (b) = 8 bits Half-word (h) = 2 bytes = 16 bits word (w) = 4 bytes = 32 bits 2

ALIGNMENT • Processor expects: – – – half-words and words to be properly aligned Half-word: address evenly divisible by 2 Word: address evenly divisible by 4 Byte: address can be anything Why? Makes processor internals more simple • Ex: Load word at 0 x 27 Load halfword at 0 x 32 Load word at 0 x 6 Load word at 0 x 14 Load byte at 0 x 5 3

ALIGNMENT • Processor expects: – – – half-words and words to be properly aligned Half-word: address evenly divisible by 2 Word: address evenly divisible by 4 Byte: address can be anything Why? Makes processor internals more simple • Ex: Load word at 0 x 27 Load halfword at 0 x 32 Load word at 0 x 6 Load word at 0 x 14 Load byte at 0 x 5 3

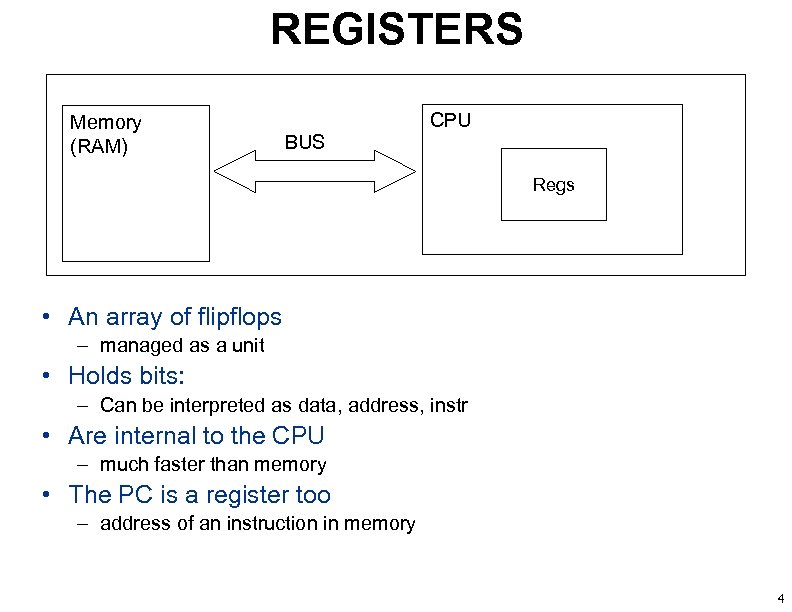

REGISTERS Memory (RAM) BUS CPU Regs • An array of flipflops – managed as a unit • Holds bits: – Can be interpreted as data, address, instr • Are internal to the CPU – much faster than memory • The PC is a register too – address of an instruction in memory 4

REGISTERS Memory (RAM) BUS CPU Regs • An array of flipflops – managed as a unit • Holds bits: – Can be interpreted as data, address, instr • Are internal to the CPU – much faster than memory • The PC is a register too – address of an instruction in memory 4

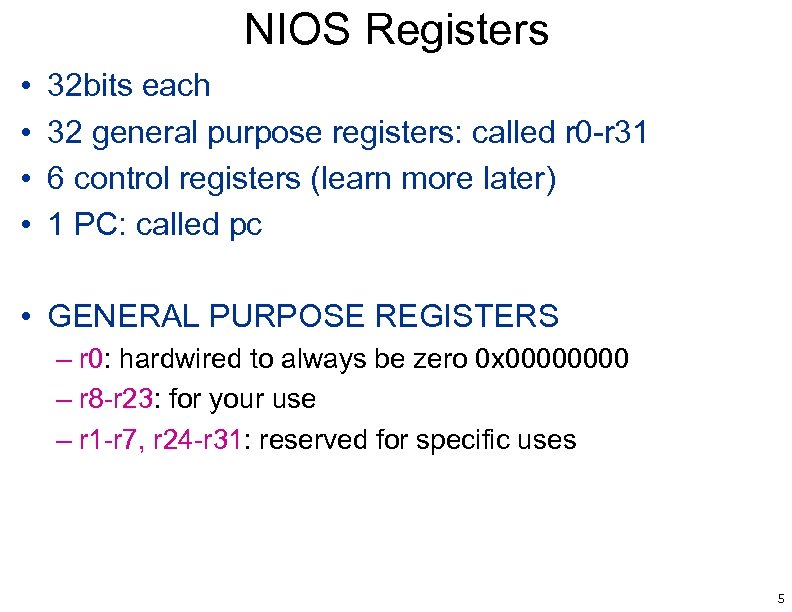

NIOS Registers • • 32 bits each 32 general purpose registers: called r 0 -r 31 6 control registers (learn more later) 1 PC: called pc • GENERAL PURPOSE REGISTERS – r 0: hardwired to always be zero 0 x 0000 – r 8 -r 23: for your use – r 1 -r 7, r 24 -r 31: reserved for specific uses 5

NIOS Registers • • 32 bits each 32 general purpose registers: called r 0 -r 31 6 control registers (learn more later) 1 PC: called pc • GENERAL PURPOSE REGISTERS – r 0: hardwired to always be zero 0 x 0000 – r 8 -r 23: for your use – r 1 -r 7, r 24 -r 31: reserved for specific uses 5

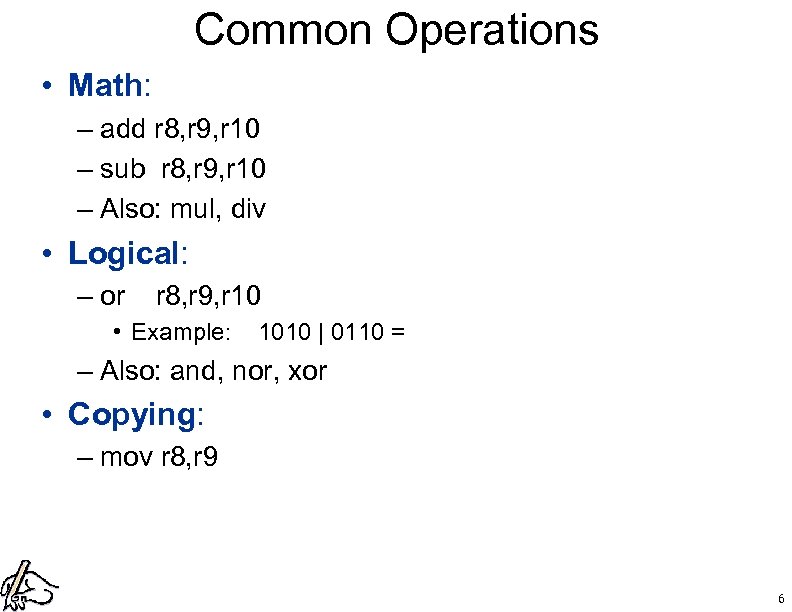

Common Operations • Math: – add r 8, r 9, r 10 – sub r 8, r 9, r 10 – Also: mul, div • Logical: – or r 8, r 9, r 10 • Example: 1010 | 0110 = – Also: and, nor, xor • Copying: – mov r 8, r 9 6

Common Operations • Math: – add r 8, r 9, r 10 – sub r 8, r 9, r 10 – Also: mul, div • Logical: – or r 8, r 9, r 10 • Example: 1010 | 0110 = – Also: and, nor, xor • Copying: – mov r 8, r 9 6

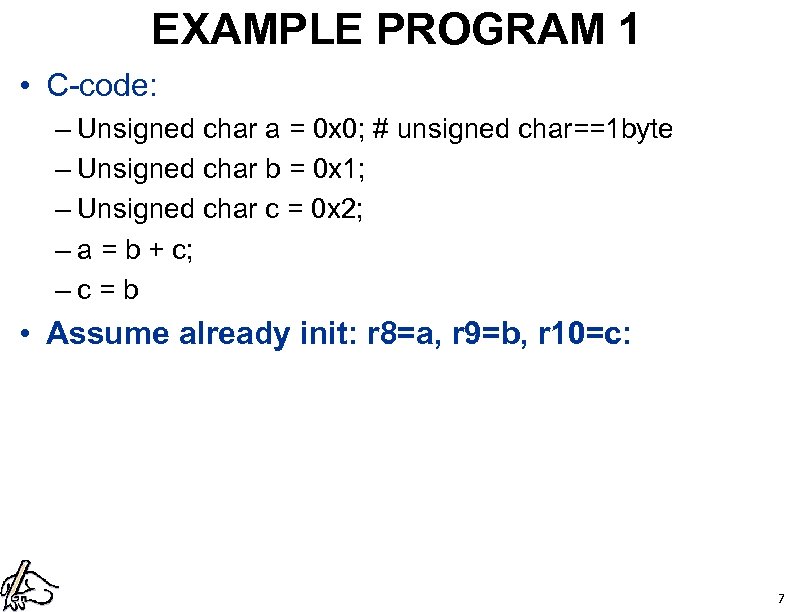

EXAMPLE PROGRAM 1 • C-code: – Unsigned char a = 0 x 0; # unsigned char==1 byte – Unsigned char b = 0 x 1; – Unsigned char c = 0 x 2; – a = b + c; – c = b • Assume already init: r 8=a, r 9=b, r 10=c: 7

EXAMPLE PROGRAM 1 • C-code: – Unsigned char a = 0 x 0; # unsigned char==1 byte – Unsigned char b = 0 x 1; – Unsigned char c = 0 x 2; – a = b + c; – c = b • Assume already init: r 8=a, r 9=b, r 10=c: 7

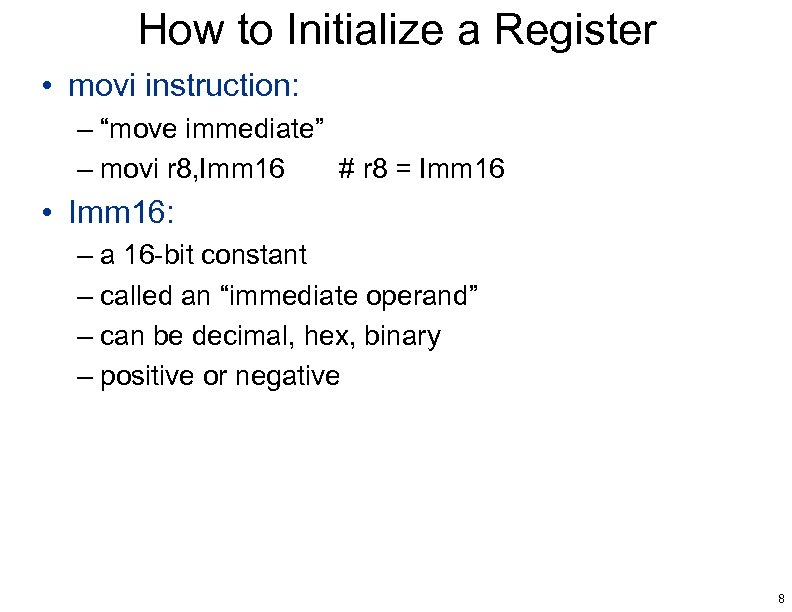

How to Initialize a Register • movi instruction: – “move immediate” – movi r 8, Imm 16 # r 8 = Imm 16 • Imm 16: – a 16 -bit constant – called an “immediate operand” – can be decimal, hex, binary – positive or negative 8

How to Initialize a Register • movi instruction: – “move immediate” – movi r 8, Imm 16 # r 8 = Imm 16 • Imm 16: – a 16 -bit constant – called an “immediate operand” – can be decimal, hex, binary – positive or negative 8

EXAMPLE PROGRAM 1 • C-code: – Unsigned char a = 0 x 0; # unsigned char==1 byte – Unsigned char b = 0 x 1; – Unsigned char c = 0 x 2; – a = b + c; – c = b • With Initialization: 9

EXAMPLE PROGRAM 1 • C-code: – Unsigned char a = 0 x 0; # unsigned char==1 byte – Unsigned char b = 0 x 1; – Unsigned char c = 0 x 2; – a = b + c; – c = b • With Initialization: 9

EXAMPLE PROGRAM 2 • Assume unsigned int == 4 bytes == 1 word – unsigned int a = 0 x 0000; – unsigned int b = 0 x 11223344; – unsigned int c = 0 x 55667788; – a = b + c; • With initialization: 10

EXAMPLE PROGRAM 2 • Assume unsigned int == 4 bytes == 1 word – unsigned int a = 0 x 0000; – unsigned int b = 0 x 11223344; – unsigned int c = 0 x 55667788; – a = b + c; • With initialization: 10

movia Instruction • “move immediate address” – movia r 9, Imm 32 # r 9 = Imm 32 • Imm 32 – a 32 -bit unsigned value (or label, more later) – doesn’t actually have to be an address! 11

movia Instruction • “move immediate address” – movia r 9, Imm 32 # r 9 = Imm 32 • Imm 32 – a 32 -bit unsigned value (or label, more later) – doesn’t actually have to be an address! 11

EXAMPLE PROGRAM 2 • Assume unsigned int == 4 bytes == 1 word – unsigned int a = 0 x 0000; – unsigned int b = 0 x 11223344; – unsigned int c = 0 x 55667788; – a = b + c; • Solution: 12

EXAMPLE PROGRAM 2 • Assume unsigned int == 4 bytes == 1 word – unsigned int a = 0 x 0000; – unsigned int b = 0 x 11223344; – unsigned int c = 0 x 55667788; – a = b + c; • Solution: 12

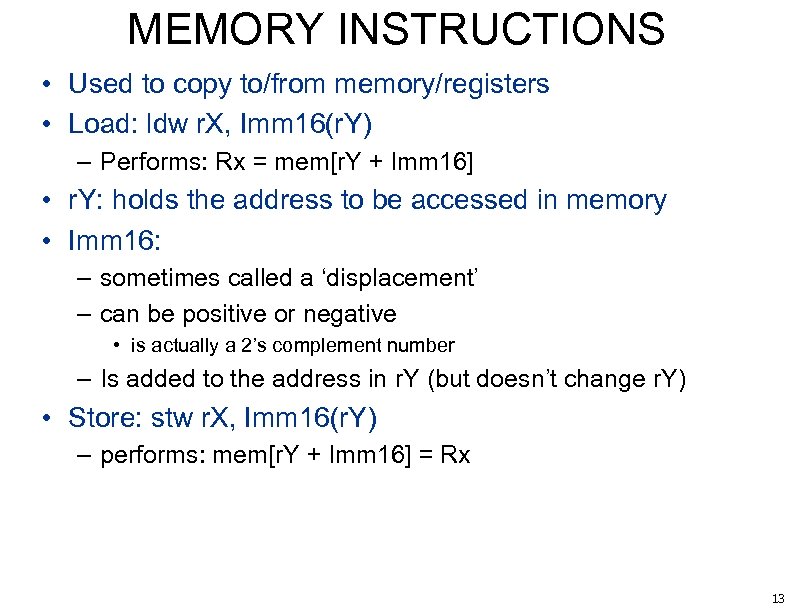

MEMORY INSTRUCTIONS • Used to copy to/from memory/registers • Load: ldw r. X, Imm 16(r. Y) – Performs: Rx = mem[r. Y + Imm 16] • r. Y: holds the address to be accessed in memory • Imm 16: – sometimes called a ‘displacement’ – can be positive or negative • is actually a 2’s complement number – Is added to the address in r. Y (but doesn’t change r. Y) • Store: stw r. X, Imm 16(r. Y) – performs: mem[r. Y + Imm 16] = Rx 13

MEMORY INSTRUCTIONS • Used to copy to/from memory/registers • Load: ldw r. X, Imm 16(r. Y) – Performs: Rx = mem[r. Y + Imm 16] • r. Y: holds the address to be accessed in memory • Imm 16: – sometimes called a ‘displacement’ – can be positive or negative • is actually a 2’s complement number – Is added to the address in r. Y (but doesn’t change r. Y) • Store: stw r. X, Imm 16(r. Y) – performs: mem[r. Y + Imm 16] = Rx 13

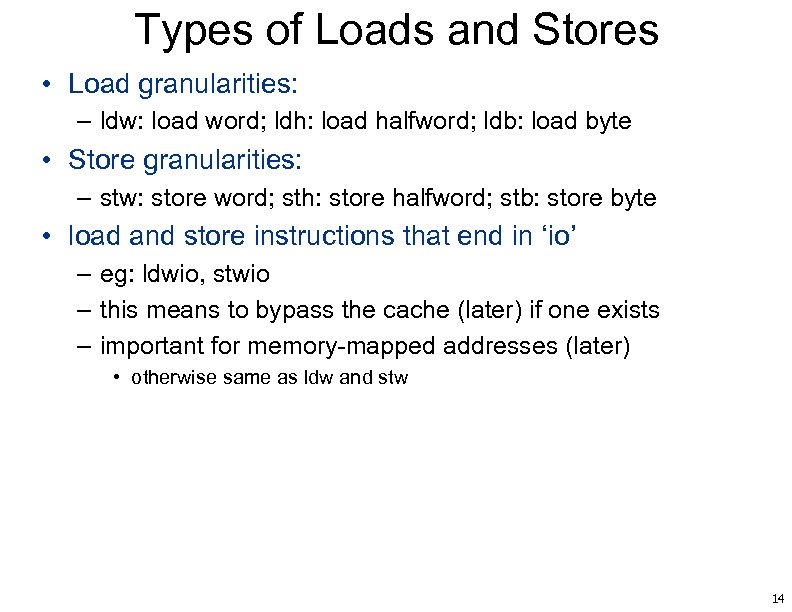

Types of Loads and Stores • Load granularities: – ldw: load word; ldh: load halfword; ldb: load byte • Store granularities: – stw: store word; sth: store halfword; stb: store byte • load and store instructions that end in ‘io’ – eg: ldwio, stwio – this means to bypass the cache (later) if one exists – important for memory-mapped addresses (later) • otherwise same as ldw and stw 14

Types of Loads and Stores • Load granularities: – ldw: load word; ldh: load halfword; ldb: load byte • Store granularities: – stw: store word; sth: store halfword; stb: store byte • load and store instructions that end in ‘io’ – eg: ldwio, stwio – this means to bypass the cache (later) if one exists – important for memory-mapped addresses (later) • otherwise same as ldw and stw 14

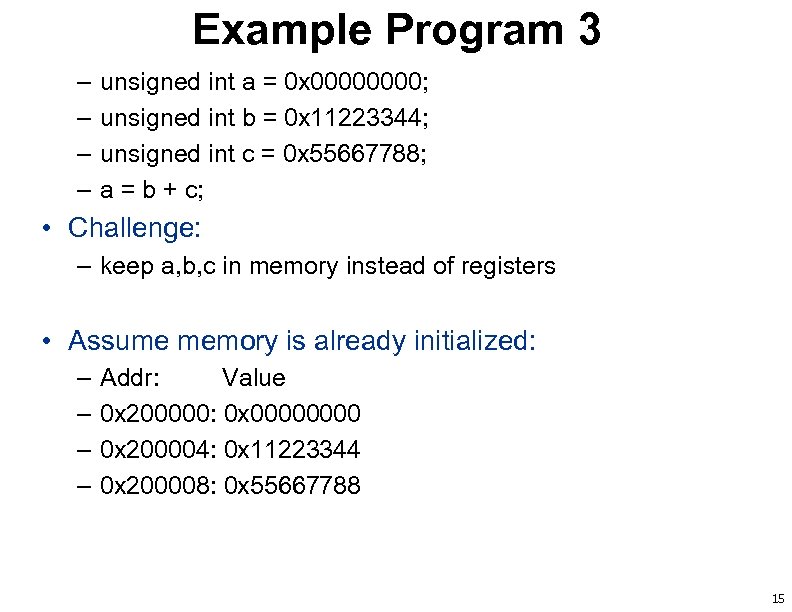

Example Program 3 – – unsigned int a = 0 x 0000; unsigned int b = 0 x 11223344; unsigned int c = 0 x 55667788; a = b + c; • Challenge: – keep a, b, c in memory instead of registers • Assume memory is already initialized: – – Addr: Value 0 x 200000: 0 x 0000 0 x 200004: 0 x 11223344 0 x 200008: 0 x 55667788 15

Example Program 3 – – unsigned int a = 0 x 0000; unsigned int b = 0 x 11223344; unsigned int c = 0 x 55667788; a = b + c; • Challenge: – keep a, b, c in memory instead of registers • Assume memory is already initialized: – – Addr: Value 0 x 200000: 0 x 0000 0 x 200004: 0 x 11223344 0 x 200008: 0 x 55667788 15

Example Program 3 – – unsigned int a = 0 x 0000; unsigned int b = 0 x 11223344; unsigned int c = 0 x 55667788; a = b + c; • Solution: Memory: Addr: Value 0 x 200000: 0 x 0000 0 x 200004: 0 x 11223344 0 x 200008: 0 x 55667788 . 16

Example Program 3 – – unsigned int a = 0 x 0000; unsigned int b = 0 x 11223344; unsigned int c = 0 x 55667788; a = b + c; • Solution: Memory: Addr: Value 0 x 200000: 0 x 0000 0 x 200004: 0 x 11223344 0 x 200008: 0 x 55667788 . 16

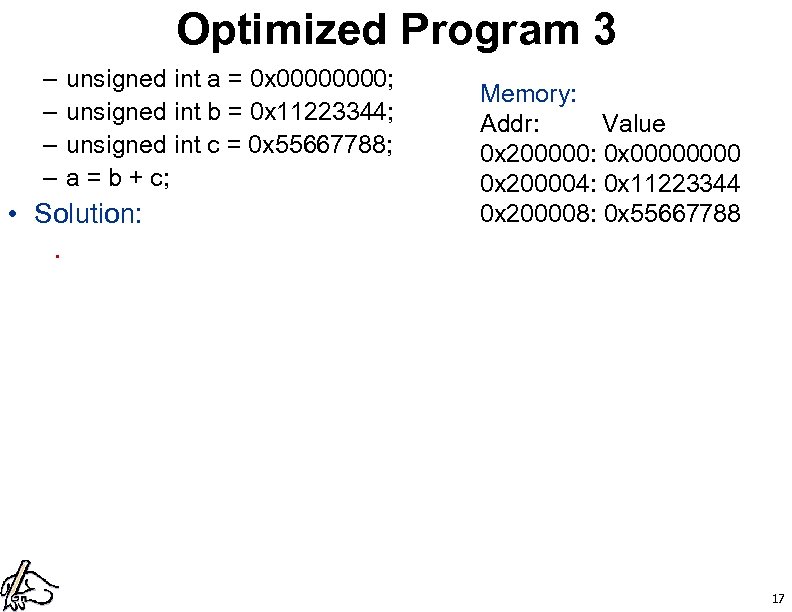

Optimized Program 3 – – unsigned int a = 0 x 0000; unsigned int b = 0 x 11223344; unsigned int c = 0 x 55667788; a = b + c; • Solution: Memory: Addr: Value 0 x 200000: 0 x 0000 0 x 200004: 0 x 11223344 0 x 200008: 0 x 55667788 . 17

Optimized Program 3 – – unsigned int a = 0 x 0000; unsigned int b = 0 x 11223344; unsigned int c = 0 x 55667788; a = b + c; • Solution: Memory: Addr: Value 0 x 200000: 0 x 0000 0 x 200004: 0 x 11223344 0 x 200008: 0 x 55667788 . 17

Addressing Modes • How you can describe operands in instrs • Addressing Modes in NIOS: – register: – immediate: – register indirect with displacement – register indirect: • Note: – other more complex ISAs can have many addressing modes (more later) 18

Addressing Modes • How you can describe operands in instrs • Addressing Modes in NIOS: – register: – immediate: – register indirect with displacement – register indirect: • Note: – other more complex ISAs can have many addressing modes (more later) 18

ECE 243 Assembly Basics 19

ECE 243 Assembly Basics 19

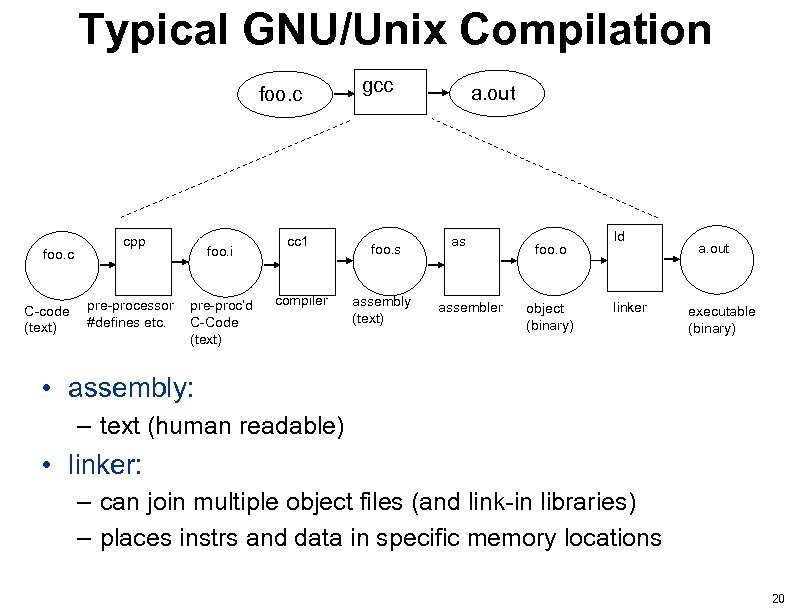

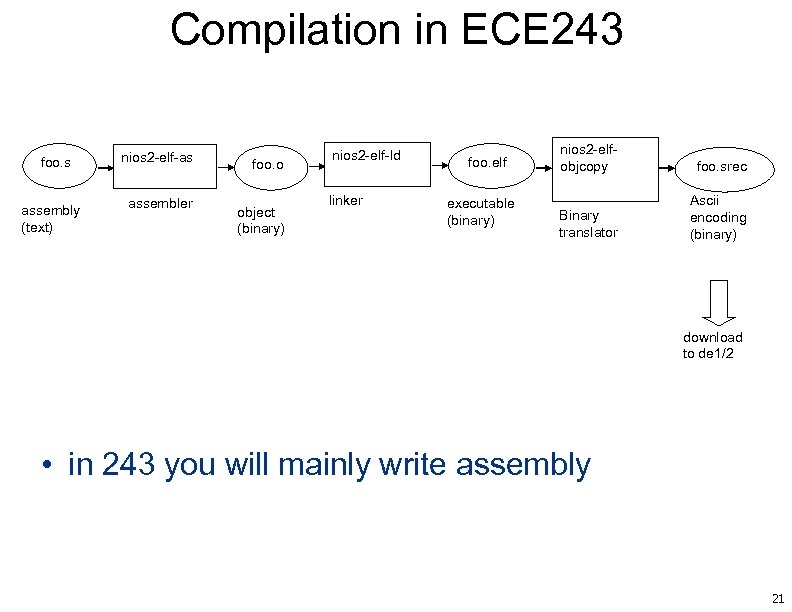

Typical GNU/Unix Compilation foo. c C-code (text) cpp pre-processor #defines etc. foo. i pre-proc’d C-Code (text) cc 1 compiler gcc foo. s assembly (text) a. out as assembler foo. o object (binary) ld linker a. out executable (binary) • assembly: – text (human readable) • linker: – can join multiple object files (and link-in libraries) – places instrs and data in specific memory locations 20

Typical GNU/Unix Compilation foo. c C-code (text) cpp pre-processor #defines etc. foo. i pre-proc’d C-Code (text) cc 1 compiler gcc foo. s assembly (text) a. out as assembler foo. o object (binary) ld linker a. out executable (binary) • assembly: – text (human readable) • linker: – can join multiple object files (and link-in libraries) – places instrs and data in specific memory locations 20

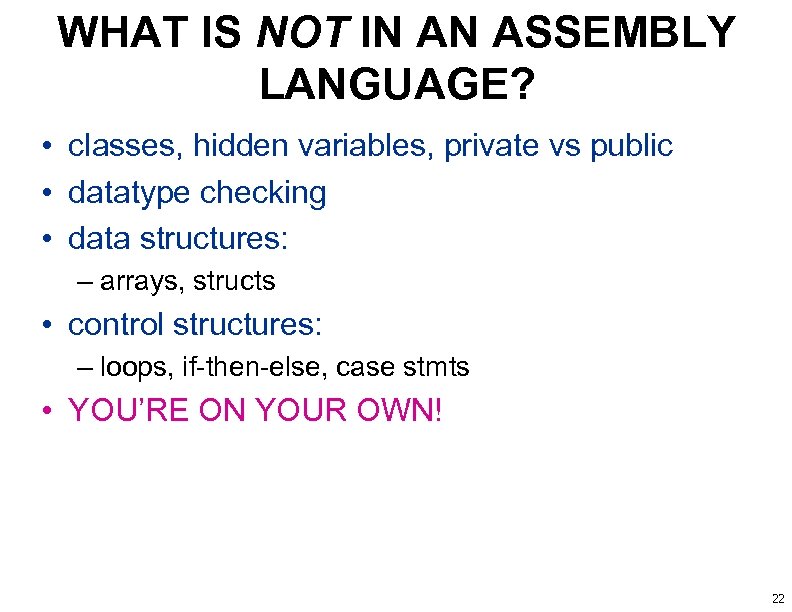

Compilation in ECE 243 foo. s assembly (text) nios 2 -elf-as assembler foo. o object (binary) nios 2 -elf-ld linker foo. elf executable (binary) nios 2 -elfobjcopy foo. srec Binary translator Ascii encoding (binary) download to de 1/2 • in 243 you will mainly write assembly 21

Compilation in ECE 243 foo. s assembly (text) nios 2 -elf-as assembler foo. o object (binary) nios 2 -elf-ld linker foo. elf executable (binary) nios 2 -elfobjcopy foo. srec Binary translator Ascii encoding (binary) download to de 1/2 • in 243 you will mainly write assembly 21

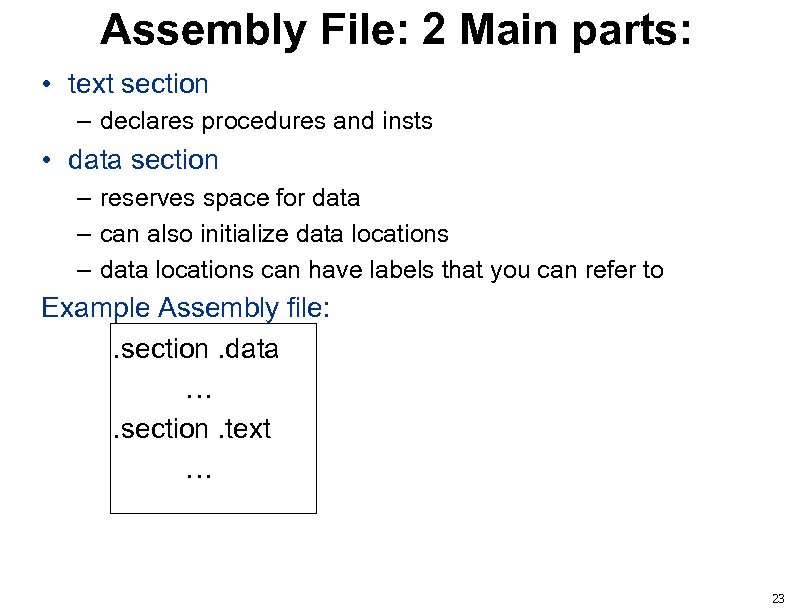

WHAT IS NOT IN AN ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE? • classes, hidden variables, private vs public • datatype checking • data structures: – arrays, structs • control structures: – loops, if-then-else, case stmts • YOU’RE ON YOUR OWN! 22

WHAT IS NOT IN AN ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE? • classes, hidden variables, private vs public • datatype checking • data structures: – arrays, structs • control structures: – loops, if-then-else, case stmts • YOU’RE ON YOUR OWN! 22

Assembly File: 2 Main parts: • text section – declares procedures and insts • data section – reserves space for data – can also initialize data locations – data locations can have labels that you can refer to Example Assembly file: . section. data …. section. text … 23

Assembly File: 2 Main parts: • text section – declares procedures and insts • data section – reserves space for data – can also initialize data locations – data locations can have labels that you can refer to Example Assembly file: . section. data …. section. text … 23

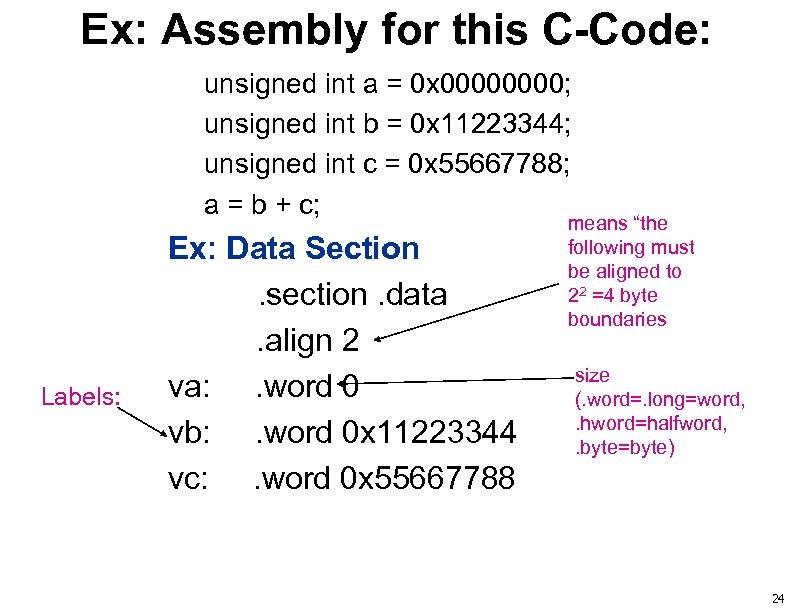

Ex: Assembly for this C-Code: unsigned int a = 0 x 0000; unsigned int b = 0 x 11223344; unsigned int c = 0 x 55667788; a = b + c; Labels: Ex: Data Section . section. data . align 2 va: . word 0 vb: . word 0 x 11223344 vc: . word 0 x 55667788 means “the following must be aligned to 22 =4 byte boundaries size (. word=. long=word, . hword=halfword, . byte=byte) 24

Ex: Assembly for this C-Code: unsigned int a = 0 x 0000; unsigned int b = 0 x 11223344; unsigned int c = 0 x 55667788; a = b + c; Labels: Ex: Data Section . section. data . align 2 va: . word 0 vb: . word 0 x 11223344 vc: . word 0 x 55667788 means “the following must be aligned to 22 =4 byte boundaries size (. word=. long=word, . hword=halfword, . byte=byte) 24

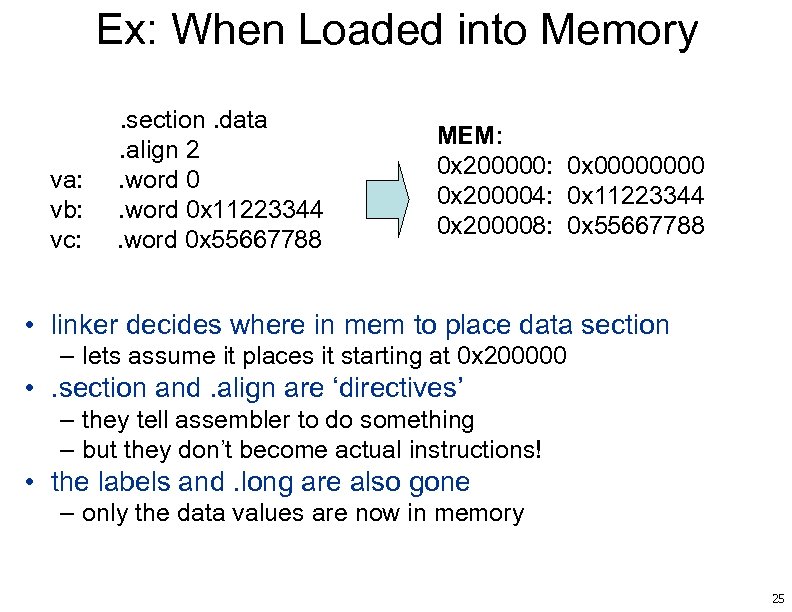

Ex: When Loaded into Memory . section. data . align 2 va: . word 0 vb: . word 0 x 11223344 vc: . word 0 x 55667788 MEM: 0 x 200000: 0 x 0000 0 x 200004: 0 x 11223344 0 x 200008: 0 x 55667788 • linker decides where in mem to place data section – lets assume it places it starting at 0 x 200000 • . section and. align are ‘directives’ – they tell assembler to do something – but they don’t become actual instructions! • the labels and. long are also gone – only the data values are now in memory 25

Ex: When Loaded into Memory . section. data . align 2 va: . word 0 vb: . word 0 x 11223344 vc: . word 0 x 55667788 MEM: 0 x 200000: 0 x 0000 0 x 200004: 0 x 11223344 0 x 200008: 0 x 55667788 • linker decides where in mem to place data section – lets assume it places it starting at 0 x 200000 • . section and. align are ‘directives’ – they tell assembler to do something – but they don’t become actual instructions! • the labels and. long are also gone – only the data values are now in memory 25

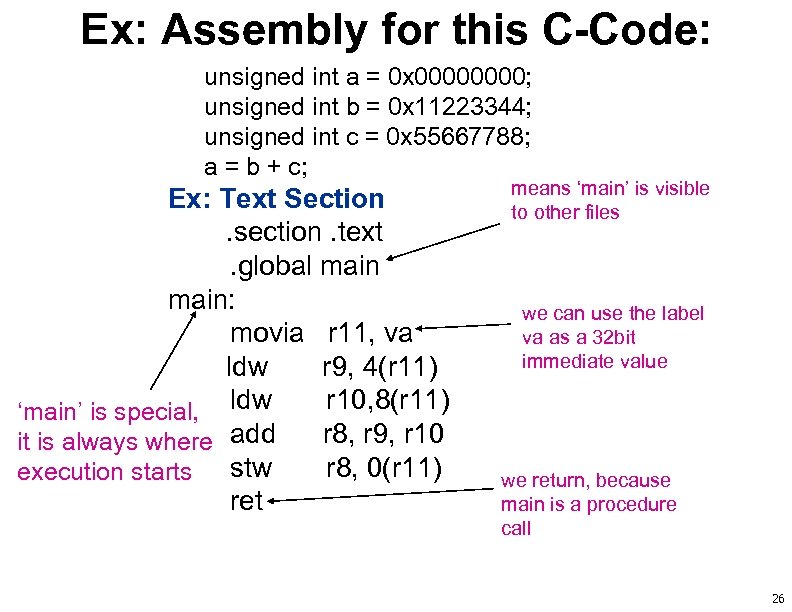

Ex: Assembly for this C-Code: unsigned int a = 0 x 0000; unsigned int b = 0 x 11223344; unsigned int c = 0 x 55667788; a = b + c; Ex: Text Section . section. text . global main: movia r 11, va ldw r 9, 4(r 11) ldw r 10, 8(r 11) ‘main’ is special, add r 8, r 9, r 10 it is always where stw r 8, 0(r 11) execution starts ret means ‘main’ is visible to other files we can use the label va as a 32 bit immediate value we return, because main is a procedure call 26

Ex: Assembly for this C-Code: unsigned int a = 0 x 0000; unsigned int b = 0 x 11223344; unsigned int c = 0 x 55667788; a = b + c; Ex: Text Section . section. text . global main: movia r 11, va ldw r 9, 4(r 11) ldw r 10, 8(r 11) ‘main’ is special, add r 8, r 9, r 10 it is always where stw r 8, 0(r 11) execution starts ret means ‘main’ is visible to other files we can use the label va as a 32 bit immediate value we return, because main is a procedure call 26

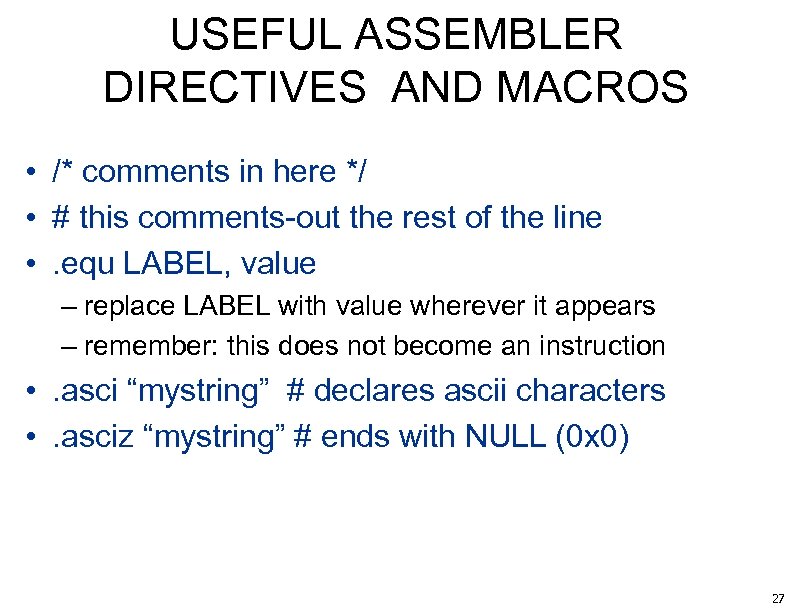

USEFUL ASSEMBLER DIRECTIVES AND MACROS • /* comments in here */ • # this comments-out the rest of the line • . equ LABEL, value – replace LABEL with value wherever it appears – remember: this does not become an instruction • . asci “mystring” # declares ascii characters • . asciz “mystring” # ends with NULL (0 x 0) 27

USEFUL ASSEMBLER DIRECTIVES AND MACROS • /* comments in here */ • # this comments-out the rest of the line • . equ LABEL, value – replace LABEL with value wherever it appears – remember: this does not become an instruction • . asci “mystring” # declares ascii characters • . asciz “mystring” # ends with NULL (0 x 0) 27

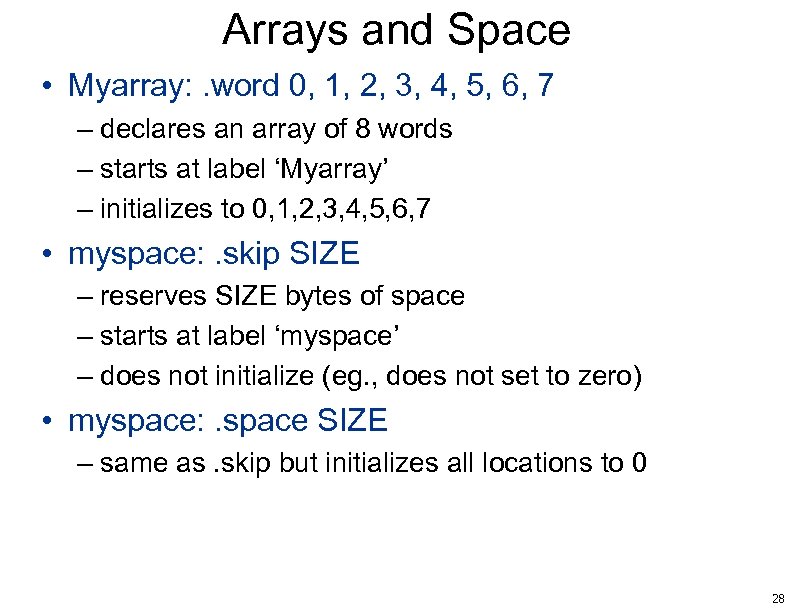

Arrays and Space • Myarray: . word 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 – declares an array of 8 words – starts at label ‘Myarray’ – initializes to 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 • myspace: . skip SIZE – reserves SIZE bytes of space – starts at label ‘myspace’ – does not initialize (eg. , does not set to zero) • myspace: . space SIZE – same as. skip but initializes all locations to 0 28

Arrays and Space • Myarray: . word 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 – declares an array of 8 words – starts at label ‘Myarray’ – initializes to 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 • myspace: . skip SIZE – reserves SIZE bytes of space – starts at label ‘myspace’ – does not initialize (eg. , does not set to zero) • myspace: . space SIZE – same as. skip but initializes all locations to 0 28

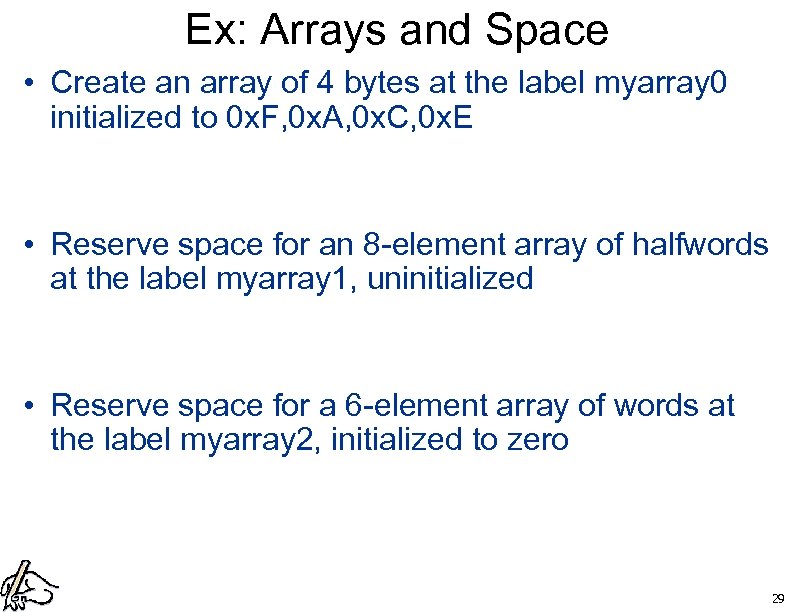

Ex: Arrays and Space • Create an array of 4 bytes at the label myarray 0 initialized to 0 x. F, 0 x. A, 0 x. C, 0 x. E • Reserve space for an 8 -element array of halfwords at the label myarray 1, uninitialized • Reserve space for a 6 -element array of words at the label myarray 2, initialized to zero 29

Ex: Arrays and Space • Create an array of 4 bytes at the label myarray 0 initialized to 0 x. F, 0 x. A, 0 x. C, 0 x. E • Reserve space for an 8 -element array of halfwords at the label myarray 1, uninitialized • Reserve space for a 6 -element array of words at the label myarray 2, initialized to zero 29

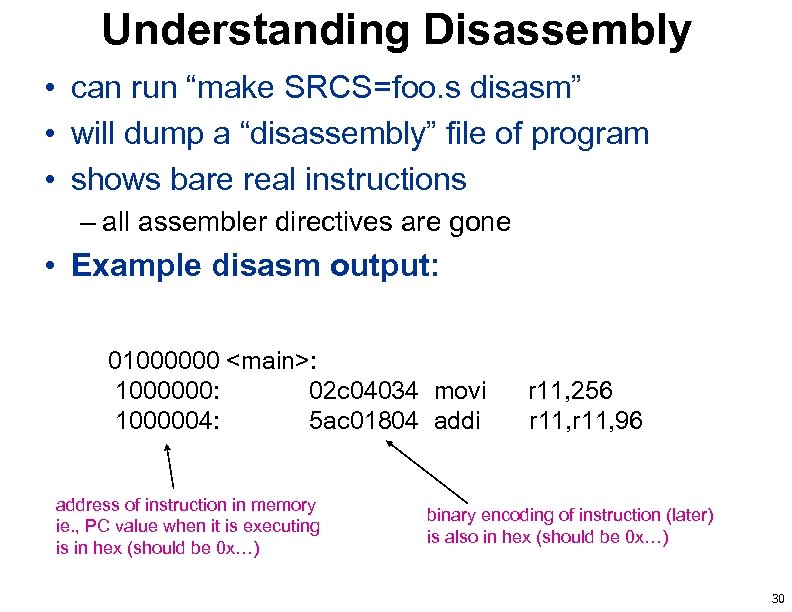

Understanding Disassembly • can run “make SRCS=foo. s disasm” • will dump a “disassembly” file of program • shows bare real instructions – all assembler directives are gone • Example disasm output: 01000000

Understanding Disassembly • can run “make SRCS=foo. s disasm” • will dump a “disassembly” file of program • shows bare real instructions – all assembler directives are gone • Example disasm output: 01000000

ECE 243 Control Flow 31

ECE 243 Control Flow 31

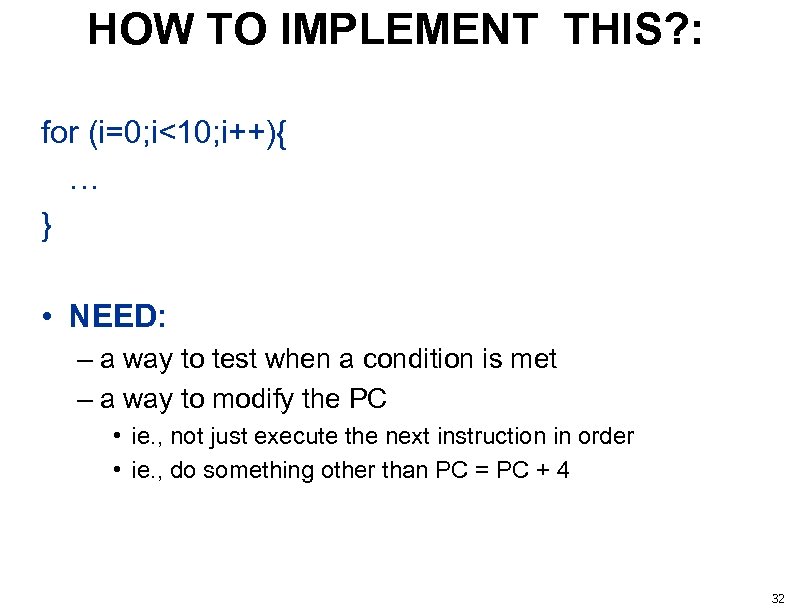

HOW TO IMPLEMENT THIS? : for (i=0; i<10; i++){ … } • NEED: – a way to test when a condition is met – a way to modify the PC • ie. , not just execute the next instruction in order • ie. , do something other than PC = PC + 4 32

HOW TO IMPLEMENT THIS? : for (i=0; i<10; i++){ … } • NEED: – a way to test when a condition is met – a way to modify the PC • ie. , not just execute the next instruction in order • ie. , do something other than PC = PC + 4 32

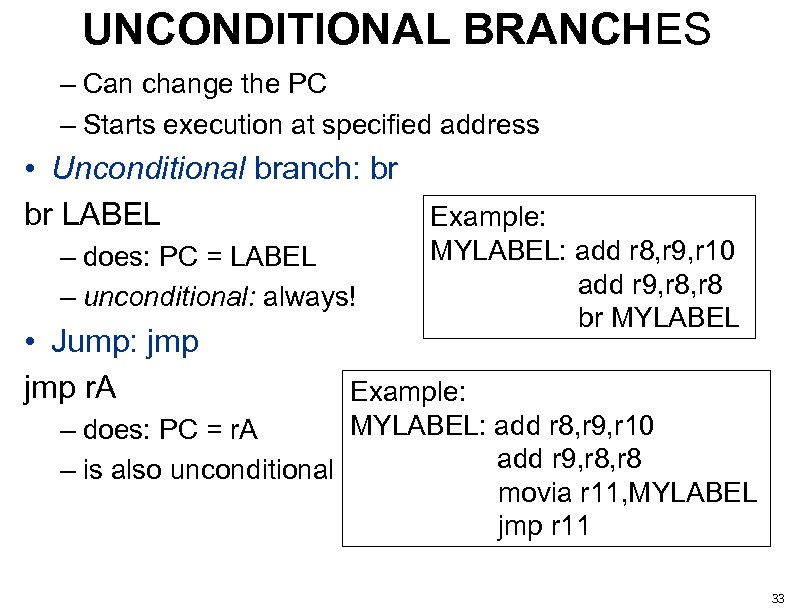

UNCONDITIONAL BRANCHES – Can change the PC – Starts execution at specified address • Unconditional branch: br br LABEL Example: – does: PC = LABEL – unconditional: always! • Jump: jmp r. A MYLABEL: add r 8, r 9, r 10 add r 9, r 8 br MYLABEL Example: MYLABEL: add r 8, r 9, r 10 – does: PC = r. A – is also unconditional add r 9, r 8 movia r 11, MYLABEL jmp r 11 33

UNCONDITIONAL BRANCHES – Can change the PC – Starts execution at specified address • Unconditional branch: br br LABEL Example: – does: PC = LABEL – unconditional: always! • Jump: jmp r. A MYLABEL: add r 8, r 9, r 10 add r 9, r 8 br MYLABEL Example: MYLABEL: add r 8, r 9, r 10 – does: PC = r. A – is also unconditional add r 9, r 8 movia r 11, MYLABEL jmp r 11 33

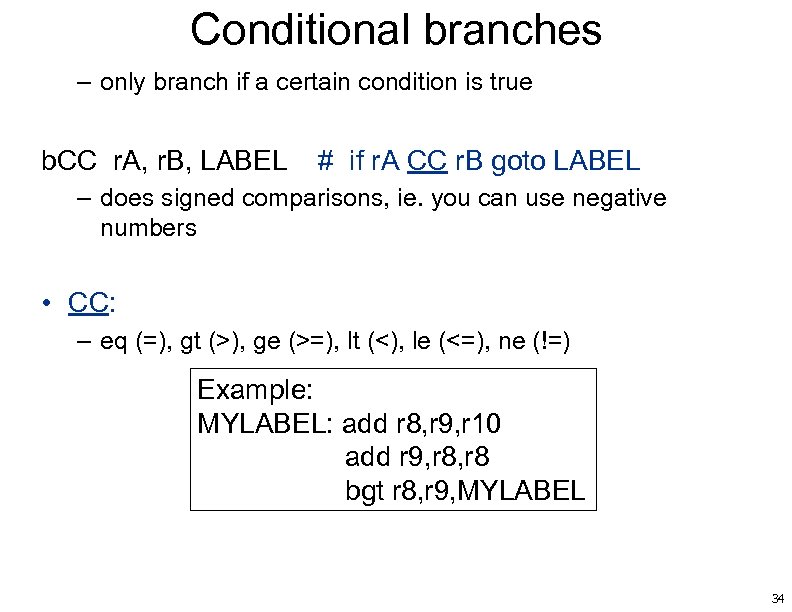

Conditional branches – only branch if a certain condition is true b. CC r. A, r. B, LABEL # if r. A CC r. B goto LABEL – does signed comparisons, ie. you can use negative numbers • CC: – eq (=), gt (>), ge (>=), lt (<), le (<=), ne (!=) Example: MYLABEL: add r 8, r 9, r 10 add r 9, r 8 bgt r 8, r 9, MYLABEL 34

Conditional branches – only branch if a certain condition is true b. CC r. A, r. B, LABEL # if r. A CC r. B goto LABEL – does signed comparisons, ie. you can use negative numbers • CC: – eq (=), gt (>), ge (>=), lt (<), le (<=), ne (!=) Example: MYLABEL: add r 8, r 9, r 10 add r 9, r 8 bgt r 8, r 9, MYLABEL 34

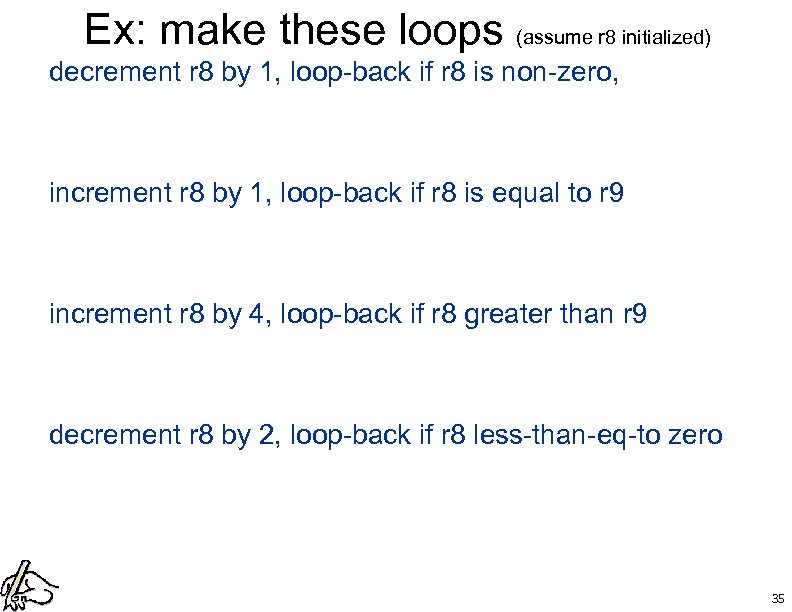

Ex: make these loops (assume r 8 initialized) decrement r 8 by 1, loop-back if r 8 is non-zero, increment r 8 by 1, loop-back if r 8 is equal to r 9 increment r 8 by 4, loop-back if r 8 greater than r 9 decrement r 8 by 2, loop-back if r 8 less-than-eq-to zero 35

Ex: make these loops (assume r 8 initialized) decrement r 8 by 1, loop-back if r 8 is non-zero, increment r 8 by 1, loop-back if r 8 is equal to r 9 increment r 8 by 4, loop-back if r 8 greater than r 9 decrement r 8 by 2, loop-back if r 8 less-than-eq-to zero 35

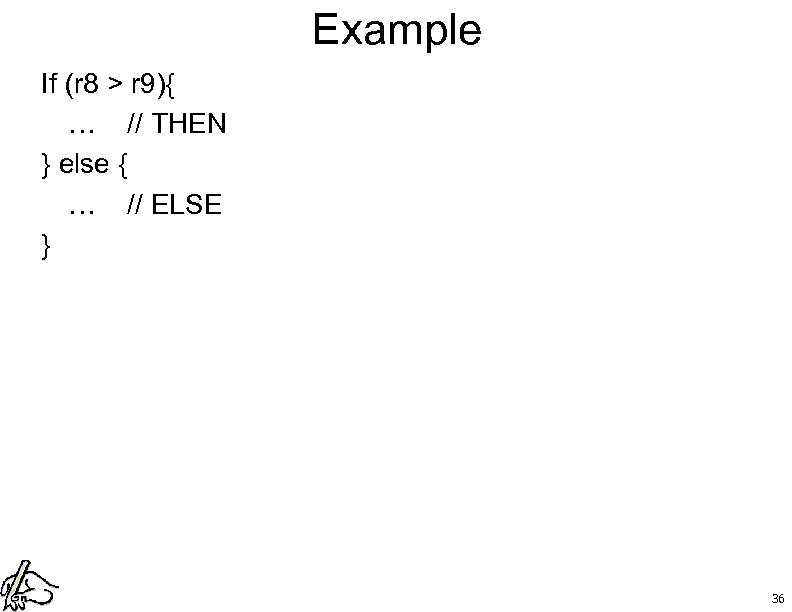

Example If (r 8 > r 9){ … // THEN } else { … // ELSE } 36

Example If (r 8 > r 9){ … // THEN } else { … // ELSE } 36

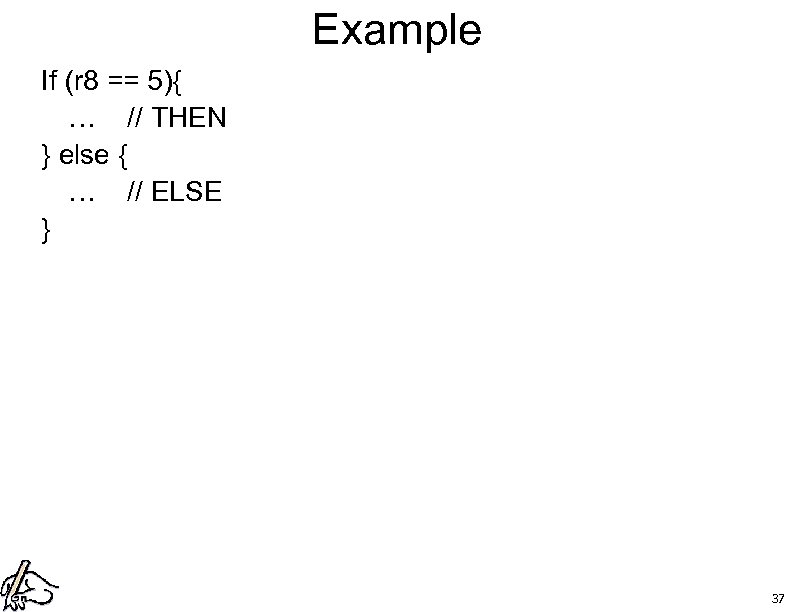

Example If (r 8 == 5){ … // THEN } else { … // ELSE } 37

Example If (r 8 == 5){ … // THEN } else { … // ELSE } 37

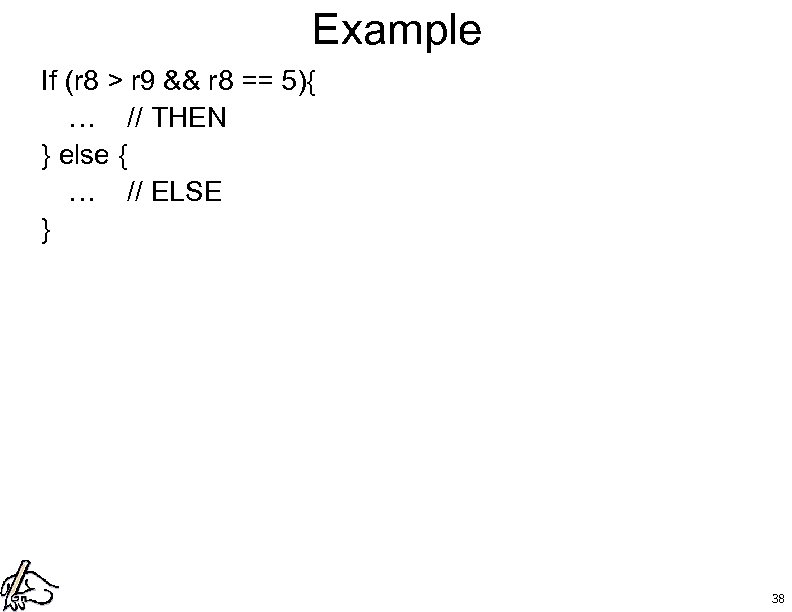

Example If (r 8 > r 9 && r 8 == 5){ … // THEN } else { … // ELSE } 38

Example If (r 8 > r 9 && r 8 == 5){ … // THEN } else { … // ELSE } 38

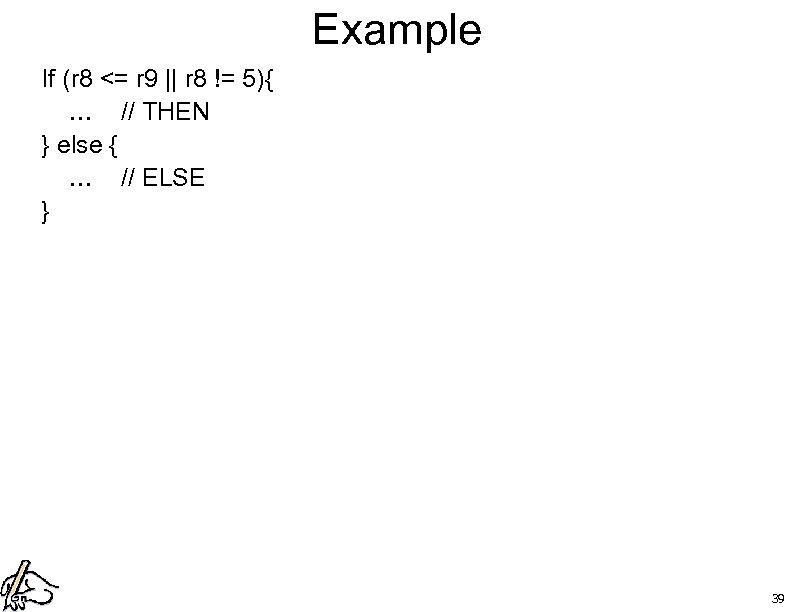

Example If (r 8 <= r 9 || r 8 != 5){ … // THEN } else { … // ELSE } 39

Example If (r 8 <= r 9 || r 8 != 5){ … // THEN } else { … // ELSE } 39

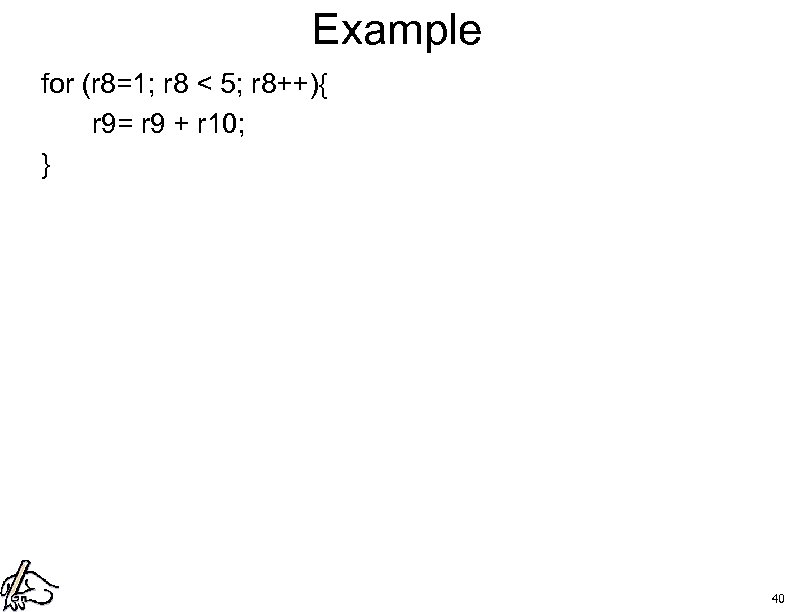

Example for (r 8=1; r 8 < 5; r 8++){ r 9= r 9 + r 10; } 40

Example for (r 8=1; r 8 < 5; r 8++){ r 9= r 9 + r 10; } 40

Example while (r 8 > 8){ r 9= r 9 + r 10; r 8 --; } 41

Example while (r 8 > 8){ r 9= r 9 + r 10; r 8 --; } 41

ECE 243 Stacks 42

ECE 243 Stacks 42

STACKS • LIFO data structure (last in first out) • Push: put new element on ‘top’ • Pop: take element off the ‘top’ • Example: push(5); push(8); pop(); 43

STACKS • LIFO data structure (last in first out) • Push: put new element on ‘top’ • Pop: take element off the ‘top’ • Example: push(5); push(8); pop(); 43

A STACK IN MEMORY • pick an address for the “bottom” of stack – stacks usually grow “upwards” – i. e. , towards lower-numbered address locations • programs usually have a “program stack” – for use by user program to store things • NIOS: – register r 27 is usually the “stack pointer” aka ‘sp’ – you can use ‘sp’ in your assembly programs • to refer to r 27 – the system initializes sp to be 0 x 17 fff 80 44

A STACK IN MEMORY • pick an address for the “bottom” of stack – stacks usually grow “upwards” – i. e. , towards lower-numbered address locations • programs usually have a “program stack” – for use by user program to store things • NIOS: – register r 27 is usually the “stack pointer” aka ‘sp’ – you can use ‘sp’ in your assembly programs • to refer to r 27 – the system initializes sp to be 0 x 17 fff 80 44

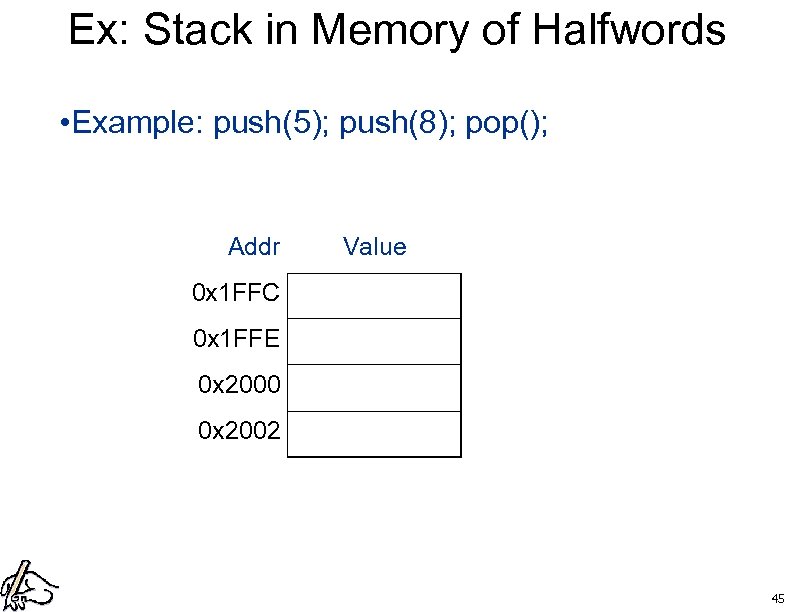

Ex: Stack in Memory of Halfwords • Example: push(5); push(8); pop(); Addr Value 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 1 FFE 0 x 2000 0 x 2002 45

Ex: Stack in Memory of Halfwords • Example: push(5); push(8); pop(); Addr Value 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 1 FFE 0 x 2000 0 x 2002 45

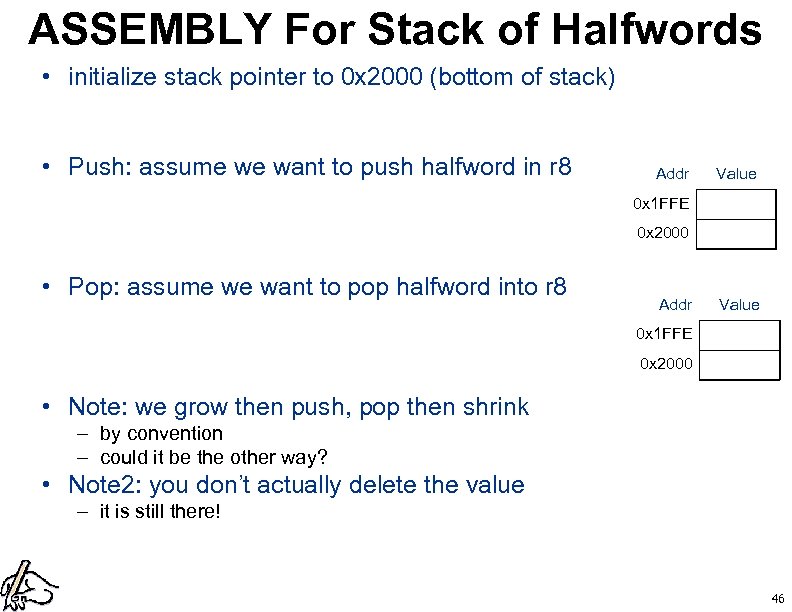

ASSEMBLY For Stack of Halfwords • initialize stack pointer to 0 x 2000 (bottom of stack) • Push: assume we want to push halfword in r 8 Addr Value 0 x 1 FFE 0 x 2000 • Pop: assume we want to pop halfword into r 8 Addr Value 0 x 1 FFE 0 x 2000 • Note: we grow then push, pop then shrink – by convention – could it be the other way? • Note 2: you don’t actually delete the value – it is still there! 46

ASSEMBLY For Stack of Halfwords • initialize stack pointer to 0 x 2000 (bottom of stack) • Push: assume we want to push halfword in r 8 Addr Value 0 x 1 FFE 0 x 2000 • Pop: assume we want to pop halfword into r 8 Addr Value 0 x 1 FFE 0 x 2000 • Note: we grow then push, pop then shrink – by convention – could it be the other way? • Note 2: you don’t actually delete the value – it is still there! 46

ECE 243 Subroutines 47

ECE 243 Subroutines 47

SUBROUTINES void bar(){ return; } void foo(){ bar(); } • foo calls bar, bar returns to foo 48

SUBROUTINES void bar(){ return; } void foo(){ bar(); } • foo calls bar, bar returns to foo 48

SUBR CALLS VS BRANCHES • a branch replaces the value of the PC – with the new location to start executing – so does a subroutine call • a subr call “remembers where it came from” – how? 49

SUBR CALLS VS BRANCHES • a branch replaces the value of the PC – with the new location to start executing – so does a subroutine call • a subr call “remembers where it came from” – how? 49

RETURN ADDRESS REGISTER • r 31 is the return address register (aka ra) – by NIOS convention – you can use ‘ra’ in assembly • NIOS convention for managing return addr: – push the previous return address (ra) on the stack – save the most recent return address in ra 50

RETURN ADDRESS REGISTER • r 31 is the return address register (aka ra) – by NIOS convention – you can use ‘ra’ in assembly • NIOS convention for managing return addr: – push the previous return address (ra) on the stack – save the most recent return address in ra 50

Make A Subr Call “by hand” Have main call bar and bar return to main 51

Make A Subr Call “by hand” Have main call bar and bar return to main 51

call and ret instructions • call LABEL – does two steps in one instruction: ra = pc+4 # ra points to instruction after the call pc = LABEL # branch to the call target location • ret – does the same thing as jmp ra: pc = ra 52

call and ret instructions • call LABEL – does two steps in one instruction: ra = pc+4 # ra points to instruction after the call pc = LABEL # branch to the call target location • ret – does the same thing as jmp ra: pc = ra 52

Subroutine Call with call/ret Have main call bar and bar return to main 53

Subroutine Call with call/ret Have main call bar and bar return to main 53

More SUBROUTINES void car(){ return; } void bar(){ car(); } void foo(){ bar(); } • foo saves return address in ra, calls bar • bar saves return address in…. oh oh! 54

More SUBROUTINES void car(){ return; } void bar(){ car(); } void foo(){ bar(); } • foo saves return address in ra, calls bar • bar saves return address in…. oh oh! 54

Handling Multiple Nested Calls • Before you call anybody: – Push the return address on the stack • When you are done calling: – Pop the return address off the stack 55

Handling Multiple Nested Calls • Before you call anybody: – Push the return address on the stack • When you are done calling: – Pop the return address off the stack 55

Call/ret saving ra on stack: 56

Call/ret saving ra on stack: 56

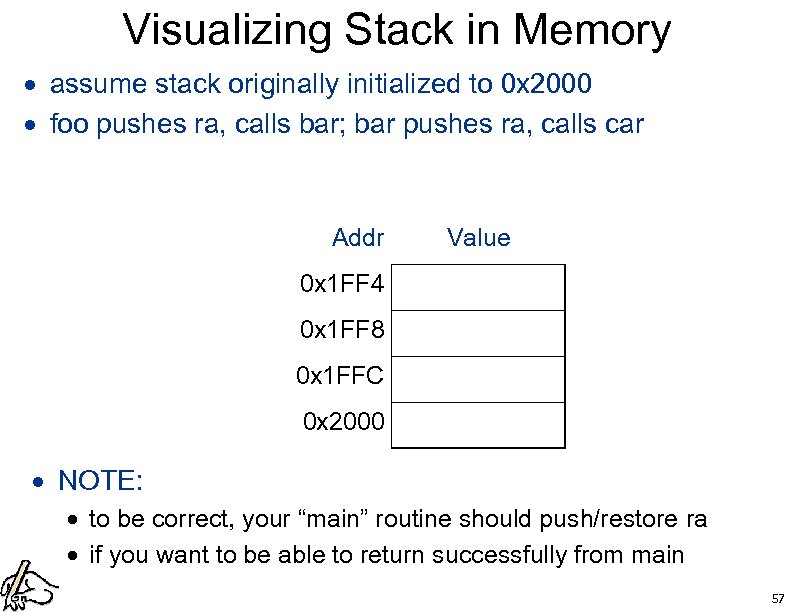

Visualizing Stack in Memory assume stack originally initialized to 0 x 2000 foo pushes ra, calls bar; bar pushes ra, calls car Addr Value 0 x 1 FF 4 0 x 1 FF 8 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 2000 NOTE: to be correct, your “main” routine should push/restore ra if you want to be able to return successfully from main 57

Visualizing Stack in Memory assume stack originally initialized to 0 x 2000 foo pushes ra, calls bar; bar pushes ra, calls car Addr Value 0 x 1 FF 4 0 x 1 FF 8 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 2000 NOTE: to be correct, your “main” routine should push/restore ra if you want to be able to return successfully from main 57

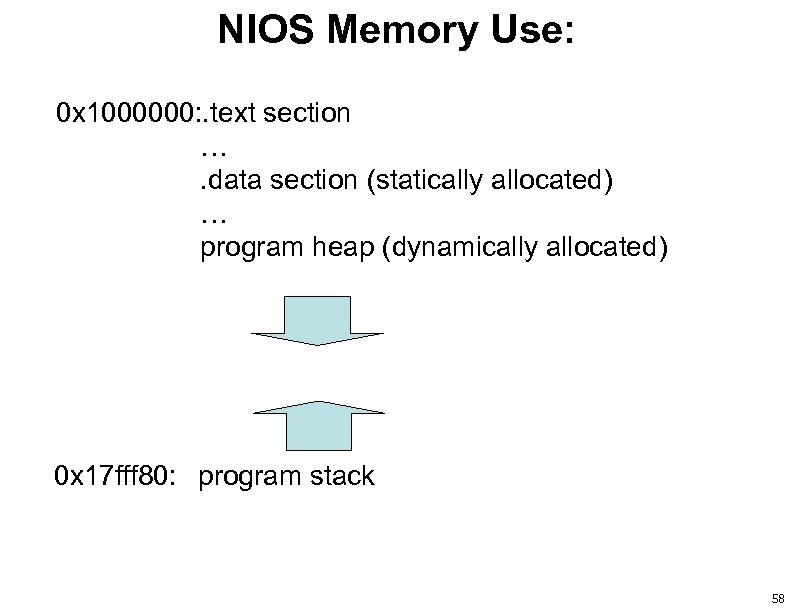

NIOS Memory Use: 0 x 1000000: . text section …. data section (statically allocated) … program heap (dynamically allocated) 0 x 17 fff 80: program stack 58

NIOS Memory Use: 0 x 1000000: . text section …. data section (statically allocated) … program heap (dynamically allocated) 0 x 17 fff 80: program stack 58

CALLER AND CALLEE void car(){ return; } void bar(){ car(); } void foo(){ bar(); } 59

CALLER AND CALLEE void car(){ return; } void bar(){ car(); } void foo(){ bar(); } 59

INDEPENDENCE OF SUBROUTINES • a big program may have many subroutines • subroutines all need registers – there are only 32 registers (fewer free for use) – how do we arrange for subrs to all share regs? • solution 1: each subr can use certain regs – hard to manage, what if things change – will run out of registers with a big program • solution 2: subrs share the same regs – must save and restore register values – two schemes for deciding who saves/restores 60

INDEPENDENCE OF SUBROUTINES • a big program may have many subroutines • subroutines all need registers – there are only 32 registers (fewer free for use) – how do we arrange for subrs to all share regs? • solution 1: each subr can use certain regs – hard to manage, what if things change – will run out of registers with a big program • solution 2: subrs share the same regs – must save and restore register values – two schemes for deciding who saves/restores 60

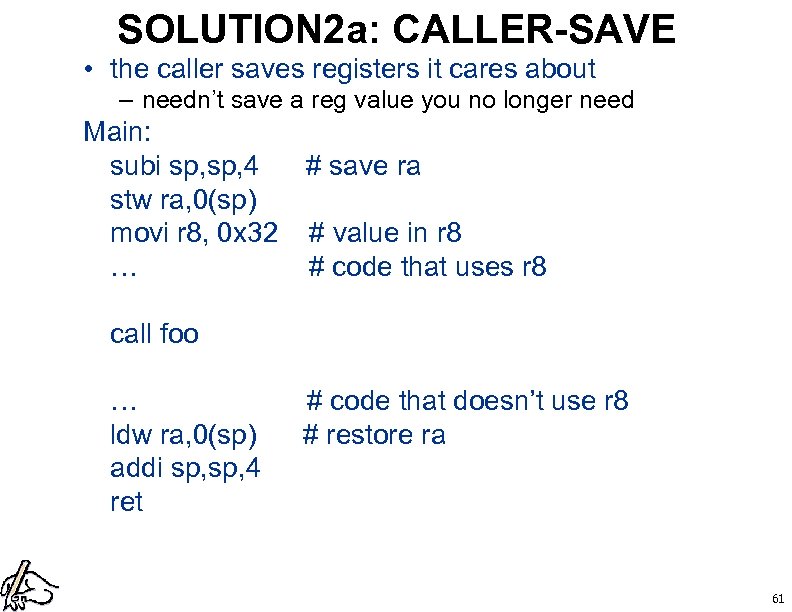

SOLUTION 2 a: CALLER-SAVE • the caller saves registers it cares about – needn’t save a reg value you no longer need Main: subi sp, 4 # save ra stw ra, 0(sp) movi r 8, 0 x 32 # value in r 8 … # code that uses r 8 call foo … # code that doesn’t use r 8 ldw ra, 0(sp) # restore ra addi sp, 4 ret 61

SOLUTION 2 a: CALLER-SAVE • the caller saves registers it cares about – needn’t save a reg value you no longer need Main: subi sp, 4 # save ra stw ra, 0(sp) movi r 8, 0 x 32 # value in r 8 … # code that uses r 8 call foo … # code that doesn’t use r 8 ldw ra, 0(sp) # restore ra addi sp, 4 ret 61

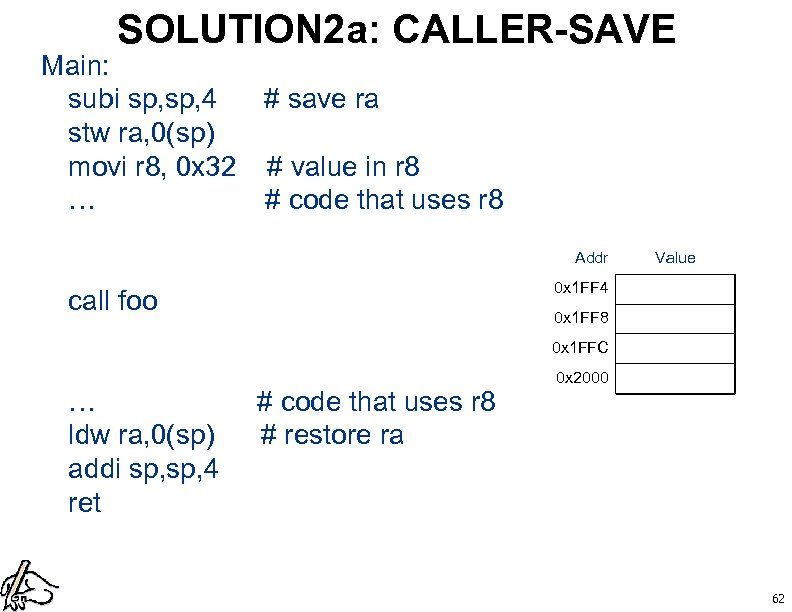

SOLUTION 2 a: CALLER-SAVE Main: subi sp, 4 # save ra stw ra, 0(sp) movi r 8, 0 x 32 # value in r 8 … # code that uses r 8 Addr call foo … # code that uses r 8 ldw ra, 0(sp) # restore ra addi sp, 4 ret Value 0 x 1 FF 4 0 x 1 FF 8 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 2000 62

SOLUTION 2 a: CALLER-SAVE Main: subi sp, 4 # save ra stw ra, 0(sp) movi r 8, 0 x 32 # value in r 8 … # code that uses r 8 Addr call foo … # code that uses r 8 ldw ra, 0(sp) # restore ra addi sp, 4 ret Value 0 x 1 FF 4 0 x 1 FF 8 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 2000 62

Nios Convention • registers r 8 -r 15 are caller saved • if you want r 8 -r 15 to live across a call site – you must save/restore it before/after any call – because the callee might change it! • You should do this for all code you write! – Even if only one callee – Even if you know it won’t modify r 8 -r 15 – You might add more callees later – Your TA might deduct marks for bad style 63

Nios Convention • registers r 8 -r 15 are caller saved • if you want r 8 -r 15 to live across a call site – you must save/restore it before/after any call – because the callee might change it! • You should do this for all code you write! – Even if only one callee – Even if you know it won’t modify r 8 -r 15 – You might add more callees later – Your TA might deduct marks for bad style 63

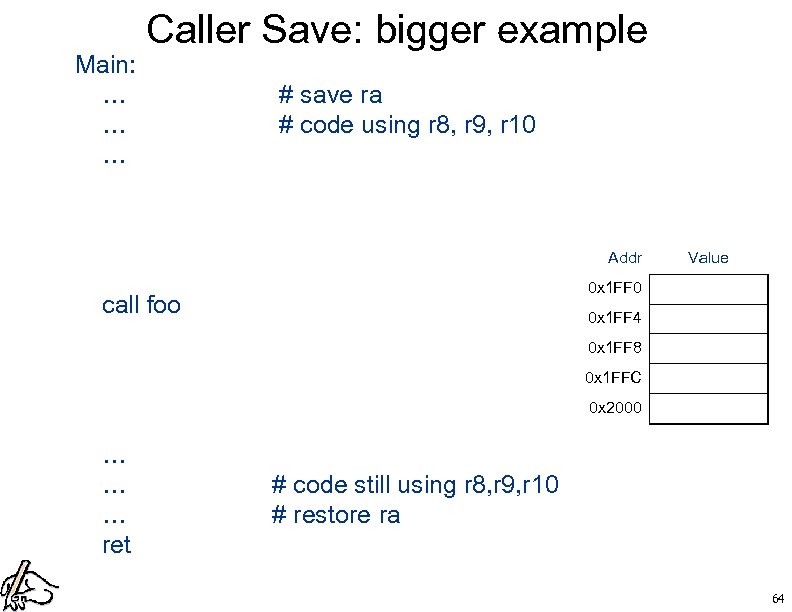

Caller Save: bigger example Main: … # save ra … # code using r 8, r 9, r 10 … Addr call foo Value 0 x 1 FF 0 0 x 1 FF 4 0 x 1 FF 8 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 2000 … … # code still using r 8, r 9, r 10 … # restore ra ret 64

Caller Save: bigger example Main: … # save ra … # code using r 8, r 9, r 10 … Addr call foo Value 0 x 1 FF 0 0 x 1 FF 4 0 x 1 FF 8 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 2000 … … # code still using r 8, r 9, r 10 … # restore ra ret 64

Solution 2 b: Callee Save Foo: #typically save/restore all callee-saved regs at #the beginning/end … # print something to the screen movi r 8, 0 x 393 # messes up r 8 movi r 16, 0 x 555 # messes up r 16 … # other code Addr Value 0 x 1 FF 4 0 x 1 FF 8 ret 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 2000 65

Solution 2 b: Callee Save Foo: #typically save/restore all callee-saved regs at #the beginning/end … # print something to the screen movi r 8, 0 x 393 # messes up r 8 movi r 16, 0 x 555 # messes up r 16 … # other code Addr Value 0 x 1 FF 4 0 x 1 FF 8 ret 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 2000 65

Nios Convention • registers r 16 -r 23 are callee saved • if you want to modify r 16 -r 23 – then you must save/restore them at the beginning/end of your procedure • You should do this for all code you write! – Even if only one caller – Even if you know it doesn’t care about r 16 -r 23 – You might add more callers later – Your TA might deduct marks for bad style 66

Nios Convention • registers r 16 -r 23 are callee saved • if you want to modify r 16 -r 23 – then you must save/restore them at the beginning/end of your procedure • You should do this for all code you write! – Even if only one caller – Even if you know it doesn’t care about r 16 -r 23 – You might add more callers later – Your TA might deduct marks for bad style 66

Summary • r 8 -r 15: callee-saved – save these before you use them! – restore them when you are done – recommend: save them at the top, restore at bottom • r 16 -r 23: caller-saved – save these before you make a call – restore them right after the call • Both: – only have to save/restore the regs that you modify 67

Summary • r 8 -r 15: callee-saved – save these before you use them! – restore them when you are done – recommend: save them at the top, restore at bottom • r 16 -r 23: caller-saved – save these before you make a call – restore them right after the call • Both: – only have to save/restore the regs that you modify 67

Strategy for Managing Registers • for temporaries or subr’s that don’t call anybody – use only r 8 -15 (caller-save) – don’t have to save/restore them in this case! • otherwise: – use r 16 -r 23 (callee-save) – save/restore them at the top/bottom 68

Strategy for Managing Registers • for temporaries or subr’s that don’t call anybody – use only r 8 -15 (caller-save) – don’t have to save/restore them in this case! • otherwise: – use r 16 -r 23 (callee-save) – save/restore them at the top/bottom 68

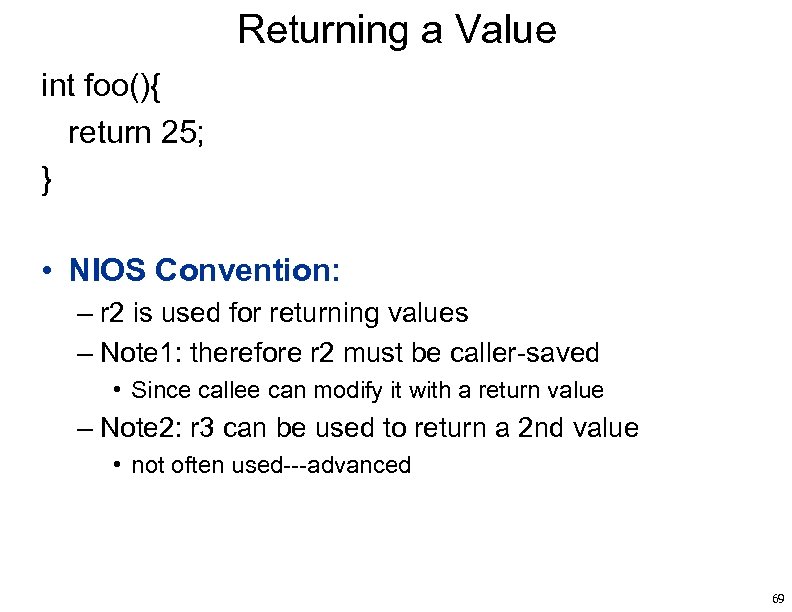

Returning a Value int foo(){ return 25; } • NIOS Convention: – r 2 is used for returning values – Note 1: therefore r 2 must be caller-saved • Since callee can modify it with a return value – Note 2: r 3 can be used to return a 2 nd value • not often used---advanced 69

Returning a Value int foo(){ return 25; } • NIOS Convention: – r 2 is used for returning values – Note 1: therefore r 2 must be caller-saved • Since callee can modify it with a return value – Note 2: r 3 can be used to return a 2 nd value • not often used---advanced 69

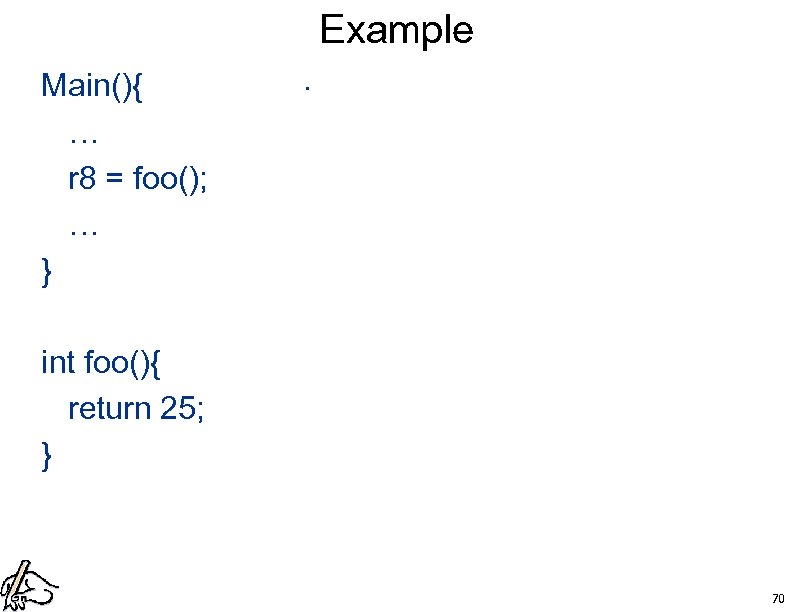

Example Main(){ … r 8 = foo(); … } int foo(){ return 25; } . 70

Example Main(){ … r 8 = foo(); … } int foo(){ return 25; } . 70

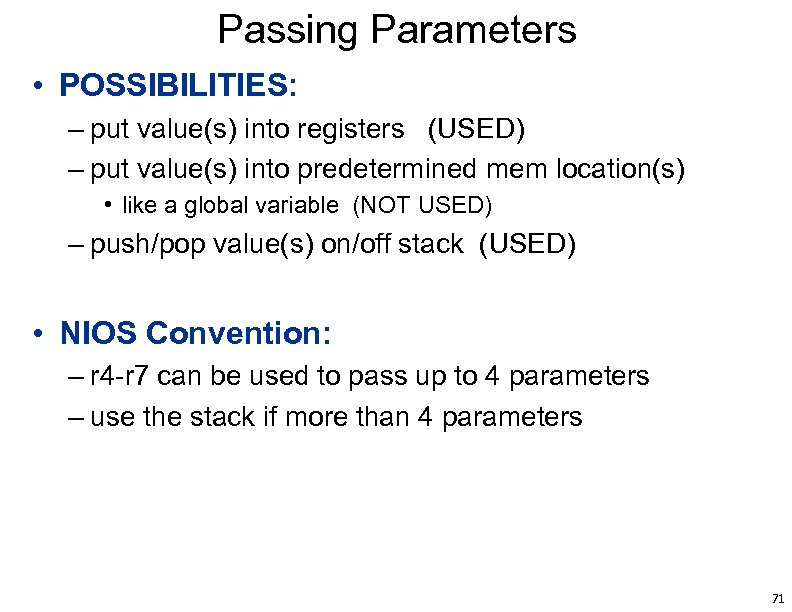

Passing Parameters • POSSIBILITIES: – put value(s) into registers (USED) – put value(s) into predetermined mem location(s) • like a global variable (NOT USED) – push/pop value(s) on/off stack (USED) • NIOS Convention: – r 4 -r 7 can be used to pass up to 4 parameters – use the stack if more than 4 parameters 71

Passing Parameters • POSSIBILITIES: – put value(s) into registers (USED) – put value(s) into predetermined mem location(s) • like a global variable (NOT USED) – push/pop value(s) on/off stack (USED) • NIOS Convention: – r 4 -r 7 can be used to pass up to 4 parameters – use the stack if more than 4 parameters 71

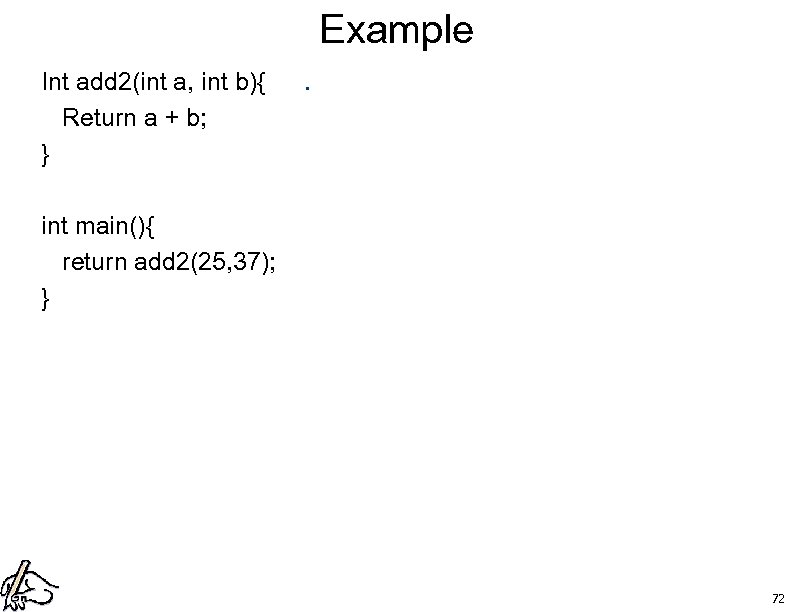

Example Int add 2(int a, int b){ Return a + b; } int main(){ return add 2(25, 37); } . 72

Example Int add 2(int a, int b){ Return a + b; } int main(){ return add 2(25, 37); } . 72

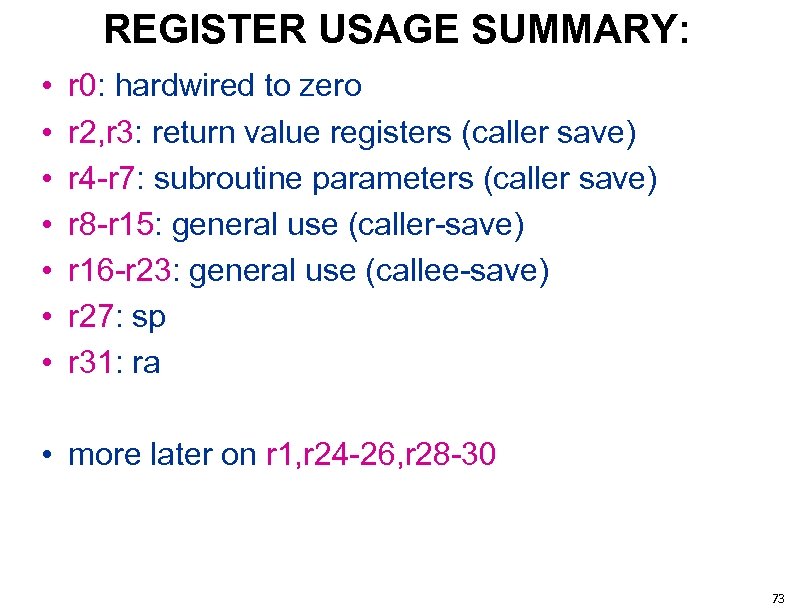

REGISTER USAGE SUMMARY: • • r 0: hardwired to zero r 2, r 3: return value registers (caller save) r 4 -r 7: subroutine parameters (caller save) r 8 -r 15: general use (caller-save) r 16 -r 23: general use (callee-save) r 27: sp r 31: ra • more later on r 1, r 24 -26, r 28 -30 73

REGISTER USAGE SUMMARY: • • r 0: hardwired to zero r 2, r 3: return value registers (caller save) r 4 -r 7: subroutine parameters (caller save) r 8 -r 15: general use (caller-save) r 16 -r 23: general use (callee-save) r 27: sp r 31: ra • more later on r 1, r 24 -26, r 28 -30 73

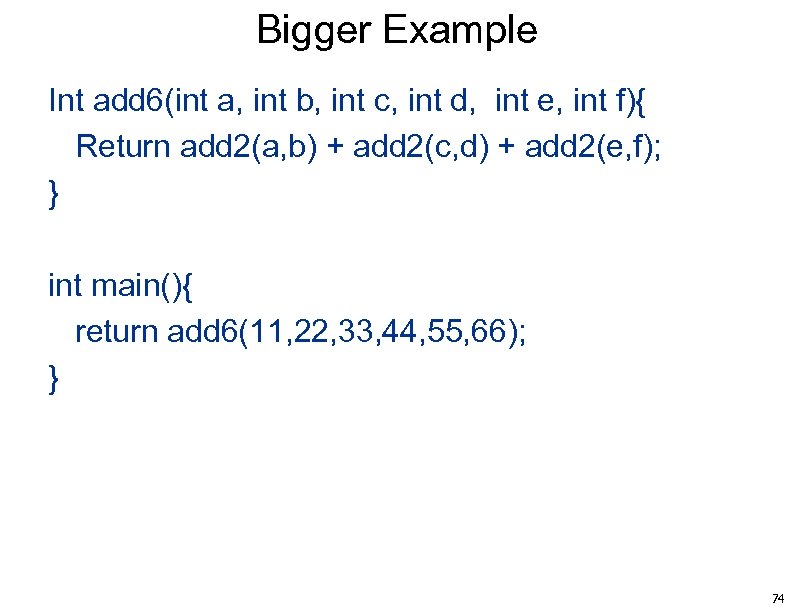

Bigger Example Int add 6(int a, int b, int c, int d, int e, int f){ Return add 2(a, b) + add 2(c, d) + add 2(e, f); } int main(){ return add 6(11, 22, 33, 44, 55, 66); } 74

Bigger Example Int add 6(int a, int b, int c, int d, int e, int f){ Return add 2(a, b) + add 2(c, d) + add 2(e, f); } int main(){ return add 6(11, 22, 33, 44, 55, 66); } 74

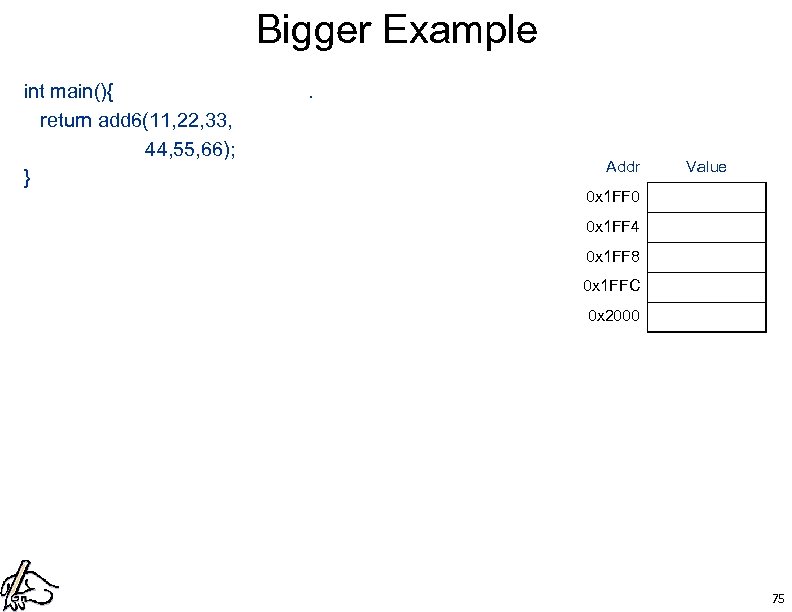

Bigger Example int main(){ return add 6(11, 22, 33, 44, 55, 66); } . Addr Value 0 x 1 FF 0 0 x 1 FF 4 0 x 1 FF 8 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 2000 75

Bigger Example int main(){ return add 6(11, 22, 33, 44, 55, 66); } . Addr Value 0 x 1 FF 0 0 x 1 FF 4 0 x 1 FF 8 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 2000 75

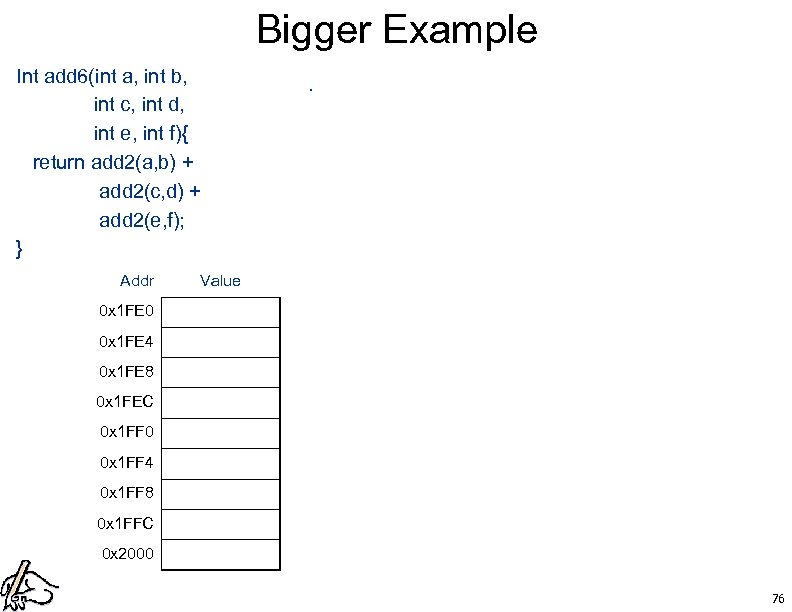

Bigger Example Int add 6(int a, int b, int c, int d, int e, int f){ return add 2(a, b) + add 2(c, d) + add 2(e, f); } Addr Value . 0 x 1 FE 0 0 x 1 FE 4 0 x 1 FE 8 0 x 1 FEC 0 x 1 FF 0 0 x 1 FF 4 0 x 1 FF 8 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 2000 76

Bigger Example Int add 6(int a, int b, int c, int d, int e, int f){ return add 2(a, b) + add 2(c, d) + add 2(e, f); } Addr Value . 0 x 1 FE 0 0 x 1 FE 4 0 x 1 FE 8 0 x 1 FEC 0 x 1 FF 0 0 x 1 FF 4 0 x 1 FF 8 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 2000 76

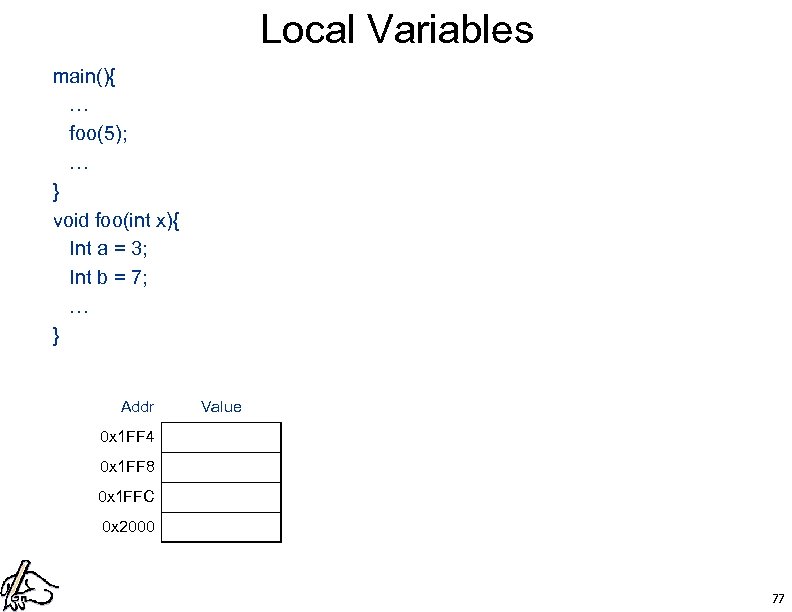

Local Variables main(){ … foo(5); … } void foo(int x){ Int a = 3; Int b = 7; … } Addr Value 0 x 1 FF 4 0 x 1 FF 8 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 2000 77

Local Variables main(){ … foo(5); … } void foo(int x){ Int a = 3; Int b = 7; … } Addr Value 0 x 1 FF 4 0 x 1 FF 8 0 x 1 FFC 0 x 2000 77

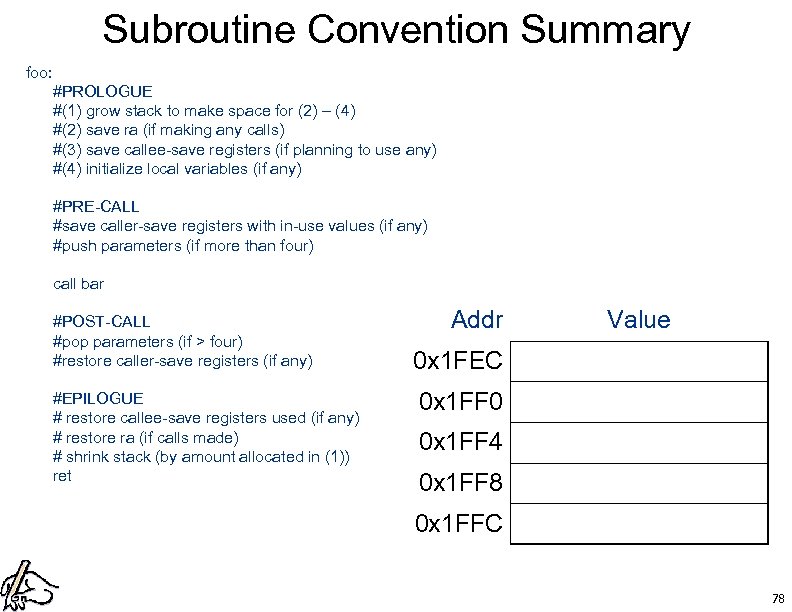

Subroutine Convention Summary foo: #PROLOGUE #(1) grow stack to make space for (2) – (4) #(2) save ra (if making any calls) #(3) save callee-save registers (if planning to use any) #(4) initialize local variables (if any) #PRE-CALL #save caller-save registers with in-use values (if any) #push parameters (if more than four) call bar #POST-CALL Addr #pop parameters (if > four) #restore caller-save registers (if any) 0 x 1 FEC #EPILOGUE 0 x 1 FF 0 # restore callee-save registers used (if any) # restore ra (if calls made) 0 x 1 FF 4 # shrink stack (by amount allocated in (1)) ret Value 0 x 1 FF 8 0 x 1 FFC 78

Subroutine Convention Summary foo: #PROLOGUE #(1) grow stack to make space for (2) – (4) #(2) save ra (if making any calls) #(3) save callee-save registers (if planning to use any) #(4) initialize local variables (if any) #PRE-CALL #save caller-save registers with in-use values (if any) #push parameters (if more than four) call bar #POST-CALL Addr #pop parameters (if > four) #restore caller-save registers (if any) 0 x 1 FEC #EPILOGUE 0 x 1 FF 0 # restore callee-save registers used (if any) # restore ra (if calls made) 0 x 1 FF 4 # shrink stack (by amount allocated in (1)) ret Value 0 x 1 FF 8 0 x 1 FFC 78

ECE 243 Is ra Caller or Callee Saved? 79

ECE 243 Is ra Caller or Callee Saved? 79

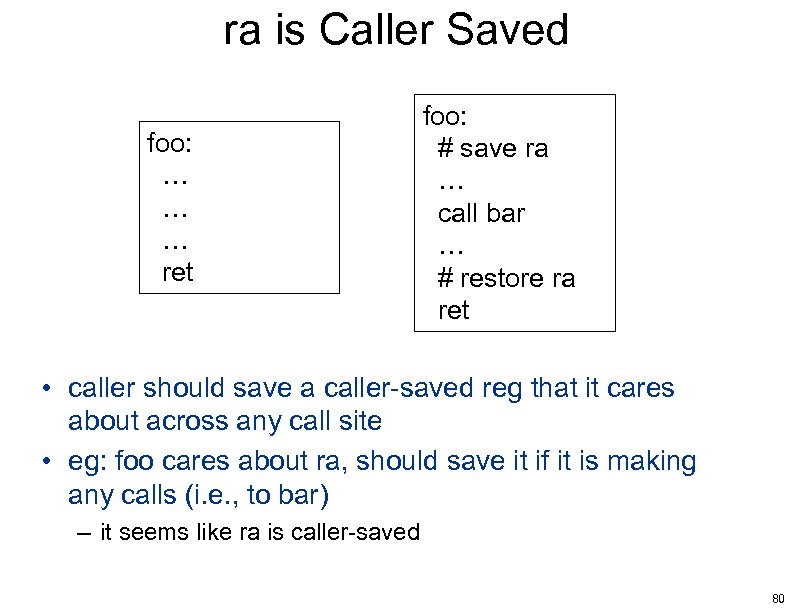

ra is Caller Saved foo: … … … ret foo: # save ra … call bar … # restore ra ret • caller should save a caller-saved reg that it cares about across any call site • eg: foo cares about ra, should save it if it is making any calls (i. e. , to bar) – it seems like ra is caller-saved 80

ra is Caller Saved foo: … … … ret foo: # save ra … call bar … # restore ra ret • caller should save a caller-saved reg that it cares about across any call site • eg: foo cares about ra, should save it if it is making any calls (i. e. , to bar) – it seems like ra is caller-saved 80

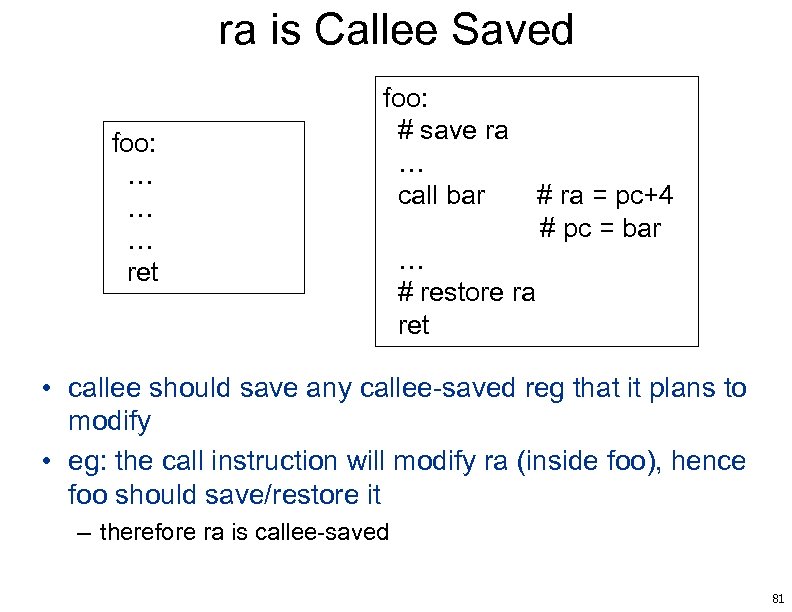

ra is Callee Saved foo: … … … ret foo: # save ra … call bar # ra = pc+4 # pc = bar … # restore ra ret • callee should save any callee-saved reg that it plans to modify • eg: the call instruction will modify ra (inside foo), hence foo should save/restore it – therefore ra is callee-saved 81

ra is Callee Saved foo: … … … ret foo: # save ra … call bar # ra = pc+4 # pc = bar … # restore ra ret • callee should save any callee-saved reg that it plans to modify • eg: the call instruction will modify ra (inside foo), hence foo should save/restore it – therefore ra is callee-saved 81

Conclusion • There arguments for both: – ra is caller-saved – ra is callee-saved • callee-saved has the stronger argument – ra is treated most like a callee-saved register 82

Conclusion • There arguments for both: – ra is caller-saved – ra is callee-saved • callee-saved has the stronger argument – ra is treated most like a callee-saved register 82