86bb10a37149f897aea9430ed357f58f.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 20

EC 307: Economic Policy in the UK Week 14: More Competition

EC 307: Economic Policy in the UK Week 14: More Competition

Entry deterrence, predation • An English reverse auction with n+1 bidders and no reserve price gives a lower expected fee than an English auction with n bidders culminating in an optimal final take-it-or-leave-it offer to the last bidder. This hold for affiliated signals if ME is upward-sloping. • The auction with a final ultimatum is not optimal if signals are affiliated, but is best among mechanisms where – Losers get nothing and – In equilibrium any winner has the lowest signal and – Winner’s fee is weakly increasing in his own signal for any realisation of others’ signals. • Even with affiliation, the expected fee from an English auction with no reservation price is the expected ME of the winning bidder. • Similarly, the expected ME of an English auction with an optimal reserve price is the minimum of the lowest bidder’s ME and C+. • In general, bidders’ costs and MEs are not independent of others’ signals. Thus MEs in a n-bidder auction are different from the same bidders’ MEs in an n+1 bidder auction. Nonetheless, it can be shown that any n+1 bidder auction with no reserve is more profitable than any standard nbidder auction. EPUK Lecture 4 2

Entry deterrence, predation • An English reverse auction with n+1 bidders and no reserve price gives a lower expected fee than an English auction with n bidders culminating in an optimal final take-it-or-leave-it offer to the last bidder. This hold for affiliated signals if ME is upward-sloping. • The auction with a final ultimatum is not optimal if signals are affiliated, but is best among mechanisms where – Losers get nothing and – In equilibrium any winner has the lowest signal and – Winner’s fee is weakly increasing in his own signal for any realisation of others’ signals. • Even with affiliation, the expected fee from an English auction with no reservation price is the expected ME of the winning bidder. • Similarly, the expected ME of an English auction with an optimal reserve price is the minimum of the lowest bidder’s ME and C+. • In general, bidders’ costs and MEs are not independent of others’ signals. Thus MEs in a n-bidder auction are different from the same bidders’ MEs in an n+1 bidder auction. Nonetheless, it can be shown that any n+1 bidder auction with no reserve is more profitable than any standard nbidder auction. EPUK Lecture 4 2

Collusion • Explicit collusion: 2 PSB more favourable than 1 PSB (harder to cheat) • Phases of the Moon scandal – concealing information from the buyer. • How to pick ‘winner’ and divide spoils? Use a pre-auction to: – Establish identity of winner (usually, want efficient result) – Set ‘winning’ bid – depends on whether cartel covers industry. – Need to establish what winner gets – depends on suspicions of buyer: he could look at the distribution of c(1) – c(2) and reject if the gap is ‘too high’ – the cartel would have to trade off seller suspicion against cheaper cheating. – Divide the spoils: gain from collusion measured by gap between c(2) and arranged fee. Can divide equally, but may not reflect bidder asymmetry. • Tacit collusion: can use early rounds to signal intentions then stop bidding, or signal via final digits. EPUK Lecture 4 3

Collusion • Explicit collusion: 2 PSB more favourable than 1 PSB (harder to cheat) • Phases of the Moon scandal – concealing information from the buyer. • How to pick ‘winner’ and divide spoils? Use a pre-auction to: – Establish identity of winner (usually, want efficient result) – Set ‘winning’ bid – depends on whether cartel covers industry. – Need to establish what winner gets – depends on suspicions of buyer: he could look at the distribution of c(1) – c(2) and reject if the gap is ‘too high’ – the cartel would have to trade off seller suspicion against cheaper cheating. – Divide the spoils: gain from collusion measured by gap between c(2) and arranged fee. Can divide equally, but may not reflect bidder asymmetry. • Tacit collusion: can use early rounds to signal intentions then stop bidding, or signal via final digits. EPUK Lecture 4 3

Many winners of procurement auctions • If no prior investment (entry, R&D cost) and uncorrelated cost information, only use split awards when costs justify it – Decreasing returns to scale – Cost complementarities – Supply risk diversification • Many auctions are not naturally one-dimensional (price quality, features, assurance, surge capacity, etc. ) – Optimal mechanisms are very complex, hence not wholly credible – Can ask for variants, or offer a menu of contracts to bidders – Give contract to bidder with lowest “compliant” cost estimate or highest “power” incentive contract – This reduces information rent (not to 0), but does not reduce cost • Split awards raise practical and conceptual issues • Quite common in US; less common in UK, EC EPUK Lecture 4 4

Many winners of procurement auctions • If no prior investment (entry, R&D cost) and uncorrelated cost information, only use split awards when costs justify it – Decreasing returns to scale – Cost complementarities – Supply risk diversification • Many auctions are not naturally one-dimensional (price quality, features, assurance, surge capacity, etc. ) – Optimal mechanisms are very complex, hence not wholly credible – Can ask for variants, or offer a menu of contracts to bidders – Give contract to bidder with lowest “compliant” cost estimate or highest “power” incentive contract – This reduces information rent (not to 0), but does not reduce cost • Split awards raise practical and conceptual issues • Quite common in US; less common in UK, EC EPUK Lecture 4 4

Practical issues • If firms have decreasing returns to scale (no externalities) and similar (common) costs, splitting is best; if firms are asymmetric, targeting is better • If firms have increasing returns to scale results are similar (trade off cost (and administrative) advantages of a pooled award against risk of higher cost, hold-up) – probably there is less than optimal splitting, esp. in UK where scales are low. • There may be outside-market firm interactions (impact on competition of giving one firm a big public contract). This can be helped by a ‘menu auction’ – Each firm bids a positive or negative amount for each possible allocation (including allocation to other firms) – Buyer selects allocation with lowest total cost, pays according to second-lowest. • These procedures fix how the market might be split and let the buyer decide whether to split. EPUK Lecture 4 5

Practical issues • If firms have decreasing returns to scale (no externalities) and similar (common) costs, splitting is best; if firms are asymmetric, targeting is better • If firms have increasing returns to scale results are similar (trade off cost (and administrative) advantages of a pooled award against risk of higher cost, hold-up) – probably there is less than optimal splitting, esp. in UK where scales are low. • There may be outside-market firm interactions (impact on competition of giving one firm a big public contract). This can be helped by a ‘menu auction’ – Each firm bids a positive or negative amount for each possible allocation (including allocation to other firms) – Buyer selects allocation with lowest total cost, pays according to second-lowest. • These procedures fix how the market might be split and let the buyer decide whether to split. EPUK Lecture 4 5

Multiple-unit auctions • Discriminatory auction – each unit at price bid (or next higher price) • Uniform price (gas, electricity) auctions like 2 PSB, but more so – rife with collusion – Smart buyer might put in own bid, leaving cartel getting a low price for residual contracts – Smart buyer might use a bit of demand uncertainty – Some non-competitive bidders might inject supply uncertainty – Seller might choose ‘discriminatory’ auction where bidder gets price s/he bids for each unit –still scope for collusion if costs are non-linear in number of units EPUK Lecture 4 6

Multiple-unit auctions • Discriminatory auction – each unit at price bid (or next higher price) • Uniform price (gas, electricity) auctions like 2 PSB, but more so – rife with collusion – Smart buyer might put in own bid, leaving cartel getting a low price for residual contracts – Smart buyer might use a bit of demand uncertainty – Some non-competitive bidders might inject supply uncertainty – Seller might choose ‘discriminatory’ auction where bidder gets price s/he bids for each unit –still scope for collusion if costs are non-linear in number of units EPUK Lecture 4 6

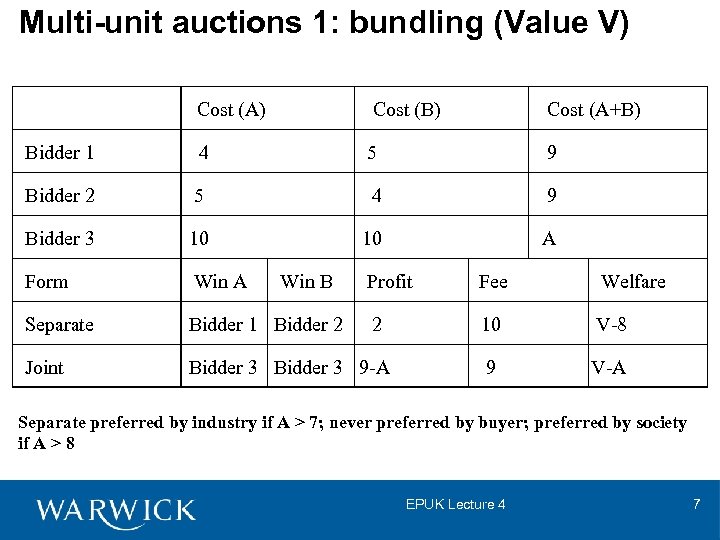

Multi-unit auctions 1: bundling (Value V) Cost (A) Cost (B) Cost (A+B) Bidder 1 4 5 9 Bidder 2 5 4 9 Bidder 3 10 10 A Form Win A Separate Bidder 1 Bidder 2 Joint Bidder 3 9 -A Win B Profit Fee Welfare 2 10 V-8 9 V-A Separate preferred by industry if A > 7; never preferred by buyer; preferred by society if A > 8 EPUK Lecture 4 7

Multi-unit auctions 1: bundling (Value V) Cost (A) Cost (B) Cost (A+B) Bidder 1 4 5 9 Bidder 2 5 4 9 Bidder 3 10 10 A Form Win A Separate Bidder 1 Bidder 2 Joint Bidder 3 9 -A Win B Profit Fee Welfare 2 10 V-8 9 V-A Separate preferred by industry if A > 7; never preferred by buyer; preferred by society if A > 8 EPUK Lecture 4 7

Multi-unit auctions 2: complementarity • Sellers with unknown costs bid for contracts to produce complementary or substitute objects • Standard package bidding solution (Vickery): – Sellers bid for all possible contracts – Buyer picks best way of dividing work-load – Buy each part from lowest bidder at highest price they could have bid while still winning that part • This ensures that truthful bidding is dominant • Works well if objects are substitutes EPUK Lecture 4 8

Multi-unit auctions 2: complementarity • Sellers with unknown costs bid for contracts to produce complementary or substitute objects • Standard package bidding solution (Vickery): – Sellers bid for all possible contracts – Buyer picks best way of dividing work-load – Buy each part from lowest bidder at highest price they could have bid while still winning that part • This ensures that truthful bidding is dominant • Works well if objects are substitutes EPUK Lecture 4 8

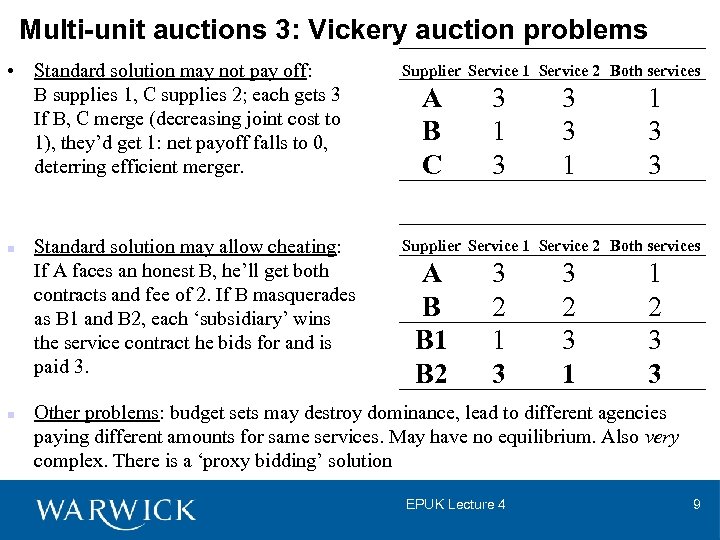

Multi-unit auctions 3: Vickery auction problems • Standard solution may not pay off: B supplies 1, C supplies 2; each gets 3 If B, C merge (decreasing joint cost to 1), they’d get 1: net payoff falls to 0, deterring efficient merger. n n Standard solution may allow cheating: If A faces an honest B, he’ll get both contracts and fee of 2. If B masquerades as B 1 and B 2, each ‘subsidiary’ wins the service contract he bids for and is paid 3. Supplier Service 1 Service 2 Both services A B C 3 1 3 3 3 1 1 3 3 Supplier Service 1 Service 2 Both services A B B 1 B 2 3 2 1 3 3 2 3 1 1 2 3 3 Other problems: budget sets may destroy dominance, lead to different agencies paying different amounts for same services. May have no equilibrium. Also very complex. There is a ‘proxy bidding’ solution EPUK Lecture 4 9

Multi-unit auctions 3: Vickery auction problems • Standard solution may not pay off: B supplies 1, C supplies 2; each gets 3 If B, C merge (decreasing joint cost to 1), they’d get 1: net payoff falls to 0, deterring efficient merger. n n Standard solution may allow cheating: If A faces an honest B, he’ll get both contracts and fee of 2. If B masquerades as B 1 and B 2, each ‘subsidiary’ wins the service contract he bids for and is paid 3. Supplier Service 1 Service 2 Both services A B C 3 1 3 3 3 1 1 3 3 Supplier Service 1 Service 2 Both services A B B 1 B 2 3 2 1 3 3 2 3 1 1 2 3 3 Other problems: budget sets may destroy dominance, lead to different agencies paying different amounts for same services. May have no equilibrium. Also very complex. There is a ‘proxy bidding’ solution EPUK Lecture 4 9

Beyond the tender: supply relationships • Often have to procure complex systems, including complements (in demand) • These need not come from the same supplier – if not, relationships (e. g. supply chain management, interoperability, whole-system reliability) become important. • Strategic problems: – A boycotts or nobbles a competitor B (cost-imposing strategies, lobbying) – A does not cooperate fully with ‘partner’ B (esp. in sharing information or R&D results). This may be particularly important when they operate on wider markets – A and B may use the supply relationship to facilitate collusion – There are theoretical incentive schemes that can prevent excess returns • Client-supplier cooperation: may need to share experience with supplier and avoid later hold-up – Government-owned, contractor-operated facilities – PFI (contractor-owned, government-operated), etc. EPUK Lecture 4 10

Beyond the tender: supply relationships • Often have to procure complex systems, including complements (in demand) • These need not come from the same supplier – if not, relationships (e. g. supply chain management, interoperability, whole-system reliability) become important. • Strategic problems: – A boycotts or nobbles a competitor B (cost-imposing strategies, lobbying) – A does not cooperate fully with ‘partner’ B (esp. in sharing information or R&D results). This may be particularly important when they operate on wider markets – A and B may use the supply relationship to facilitate collusion – There are theoretical incentive schemes that can prevent excess returns • Client-supplier cooperation: may need to share experience with supplier and avoid later hold-up – Government-owned, contractor-operated facilities – PFI (contractor-owned, government-operated), etc. EPUK Lecture 4 10

Supply of competing goods • Reducing information disadvantages – In selection (affiliated-costs example, linkage principle) – In contract operation (benchmarking, yardstick competition) – Contracting as a form of observation • A flexible solution: balancing competition within the contract with competition for the contract: multiple-sourcing – Use ‘design competition’ to select 2 (say) suppliers with (slightly) differentiated competencies – Split award along component lines in (say) 70%: 30% chunks) – Require information-sharing and common specifications – At the end of each ‘period’ give 70% share to contractor who did best on that component • End of contract: – Incumbent advantage – Intellectual (and other intangible) property created as a by-product of the contract EPUK Lecture 4 11

Supply of competing goods • Reducing information disadvantages – In selection (affiliated-costs example, linkage principle) – In contract operation (benchmarking, yardstick competition) – Contracting as a form of observation • A flexible solution: balancing competition within the contract with competition for the contract: multiple-sourcing – Use ‘design competition’ to select 2 (say) suppliers with (slightly) differentiated competencies – Split award along component lines in (say) 70%: 30% chunks) – Require information-sharing and common specifications – At the end of each ‘period’ give 70% share to contractor who did best on that component • End of contract: – Incumbent advantage – Intellectual (and other intangible) property created as a by-product of the contract EPUK Lecture 4 11

Breach and renegotiation • Any contract has conditions under which it has not been fulfilled • Sometimes this is efficient (as when the original aim is unfeasible • Contracts may specify penalty clauses – liquidated damages (money) – specific performance – Surety agencies • Courts must enforce and interpret. • Long-term contracts are particularly subject to ‘changes’ • Can renegotiation serve a strategic role? EPUK Lecture 4 12

Breach and renegotiation • Any contract has conditions under which it has not been fulfilled • Sometimes this is efficient (as when the original aim is unfeasible • Contracts may specify penalty clauses – liquidated damages (money) – specific performance – Surety agencies • Courts must enforce and interpret. • Long-term contracts are particularly subject to ‘changes’ • Can renegotiation serve a strategic role? EPUK Lecture 4 12

Renegotiation, 2 • Often, more than one party has to make relation-specific investment between signature and fulfilment (e. g. R&D, hiring workers, training, …) • This can lead to underinvestment • An enforceable contract cannot specify efficient levels of investment, since it binds the parties separately – not jointly • If one party cuts back on investment needed for the contract as a whole – They get the entire cost savings (as a benefit to shirking) – They share the reduced ‘gains from trade’ • This can be fixed by precommitment to specific types of renegotiation • By analogy with the above section on multiple-unit auctions, problems associated with direct externalities may be harder – Suppose better system design can reduce training costs or vice versa – Then optimal results only available under ‘flat’ objectives – Particularly relevant to PFI/PPP and product innovation EPUK Lecture 4 13

Renegotiation, 2 • Often, more than one party has to make relation-specific investment between signature and fulfilment (e. g. R&D, hiring workers, training, …) • This can lead to underinvestment • An enforceable contract cannot specify efficient levels of investment, since it binds the parties separately – not jointly • If one party cuts back on investment needed for the contract as a whole – They get the entire cost savings (as a benefit to shirking) – They share the reduced ‘gains from trade’ • This can be fixed by precommitment to specific types of renegotiation • By analogy with the above section on multiple-unit auctions, problems associated with direct externalities may be harder – Suppose better system design can reduce training costs or vice versa – Then optimal results only available under ‘flat’ objectives – Particularly relevant to PFI/PPP and product innovation EPUK Lecture 4 13

Now back to reality… • Public procurement is big business: – For the OECD, total procurement as a proportion of GDP is estimated at 19. 96% ($4, 733 billion – 1988 data) – For non-OECD countries, the figures are 14. 48% or $816 billion) – For the EU, 2004 -5 data show € 1500 billion contract volume (16% GDP including public services/utilities); more than 6 M contracts let by 400 K contracting agencies – Of this, a smaller fraction is potentially contestable by international trade: 7. 57% ($1, 795 billion) for OECD, 5. 10% ($287 billion) for non. OECD – Different ‘level’ (1997 data) • Central government: 29% (incl. non-competitive defence procurement) – ranging from a low of 28% of sub-central expenditure (De) to 3 times as much in the UK • Public utilities: 24% • Sub-central government: 47% (mostly contestable) – different degrees of control, aggregation possibilities, emphasis on ‘embedding’ benefits and mix of goods and services. EPUK Lecture 4 14

Now back to reality… • Public procurement is big business: – For the OECD, total procurement as a proportion of GDP is estimated at 19. 96% ($4, 733 billion – 1988 data) – For non-OECD countries, the figures are 14. 48% or $816 billion) – For the EU, 2004 -5 data show € 1500 billion contract volume (16% GDP including public services/utilities); more than 6 M contracts let by 400 K contracting agencies – Of this, a smaller fraction is potentially contestable by international trade: 7. 57% ($1, 795 billion) for OECD, 5. 10% ($287 billion) for non. OECD – Different ‘level’ (1997 data) • Central government: 29% (incl. non-competitive defence procurement) – ranging from a low of 28% of sub-central expenditure (De) to 3 times as much in the UK • Public utilities: 24% • Sub-central government: 47% (mostly contestable) – different degrees of control, aggregation possibilities, emphasis on ‘embedding’ benefits and mix of goods and services. EPUK Lecture 4 14

More background to rules and practice… • Government procurement traditionally tends to favour local suppliers, with effects similar to other protectionist measures (limited choice, increased prices, reduced efficiency) • Attempts were made to bring government procurement under multilateral trade rules since World War II. • First real progress: 1981 Tokyo Round Agreement on Government Procurement • Next step: 1996 Government Procurement Agreement (WTO) • Regional counterparts for NAFTA and EC • Basic rules: transparency and non-discrimination EPUK Lecture 4 15

More background to rules and practice… • Government procurement traditionally tends to favour local suppliers, with effects similar to other protectionist measures (limited choice, increased prices, reduced efficiency) • Attempts were made to bring government procurement under multilateral trade rules since World War II. • First real progress: 1981 Tokyo Round Agreement on Government Procurement • Next step: 1996 Government Procurement Agreement (WTO) • Regional counterparts for NAFTA and EC • Basic rules: transparency and non-discrimination EPUK Lecture 4 15

Discrimination • Three main forms – “Overt exclusion”- foreign bidders are excluded from tendering (esp. defence contracts) – “Preferential price margin” - purchasing entities accept domestic bids unless price difference exceeds a specific margin – “domestic content requirement” - government only purchases from foreign sources if they agree to buy some components from domestic firms • A fourth, “hidden” form is non-transparent tendering procedures that favour ‘insiders’ • Early work (Baldwin and others 1970 -1984) found no adverse impact: increase in domestic government demand offset by increase in private demand foreign goods • Work in late 1970’s compared public and private purchases and found substantial (up to 6 X) potential welfare gains from procurement reform • Francois (1996) analysis for US found a small impact overall, but large in key sectors e. g. construction, maintenance and repair services • General consensus: benefits from shifting profits to domestic firms offset by increasing procurement costs • All these empirical studies struggle with complex bidding behaviour, imperfect competition and informational asymmetries EPUK Lecture 4 16

Discrimination • Three main forms – “Overt exclusion”- foreign bidders are excluded from tendering (esp. defence contracts) – “Preferential price margin” - purchasing entities accept domestic bids unless price difference exceeds a specific margin – “domestic content requirement” - government only purchases from foreign sources if they agree to buy some components from domestic firms • A fourth, “hidden” form is non-transparent tendering procedures that favour ‘insiders’ • Early work (Baldwin and others 1970 -1984) found no adverse impact: increase in domestic government demand offset by increase in private demand foreign goods • Work in late 1970’s compared public and private purchases and found substantial (up to 6 X) potential welfare gains from procurement reform • Francois (1996) analysis for US found a small impact overall, but large in key sectors e. g. construction, maintenance and repair services • General consensus: benefits from shifting profits to domestic firms offset by increasing procurement costs • All these empirical studies struggle with complex bidding behaviour, imperfect competition and informational asymmetries EPUK Lecture 4 16

EU legislation • First directive on public procurement adopted in 1971 • 1990 s: Need to review public procurement Directives – 3 different directives (goods, services and utilities). • Two new directives adopted on 31 March 2004 after four years of intensive work (co-decision procedure) – 2004/17/EC for Utilities – 2004/18/EC for “Classic” (Public) Sector • Modernisation (new purchasing methods) • Simplification (fewer directives, articles, simplified “roadmap”) • Intent is to enhance flexibility and lower compliance costs while ensuring basic principles of equal treatment and transparency and enhancing competition – e-procurement – competitive dialogue – performance specifications, etc. EPUK Lecture 4 17

EU legislation • First directive on public procurement adopted in 1971 • 1990 s: Need to review public procurement Directives – 3 different directives (goods, services and utilities). • Two new directives adopted on 31 March 2004 after four years of intensive work (co-decision procedure) – 2004/17/EC for Utilities – 2004/18/EC for “Classic” (Public) Sector • Modernisation (new purchasing methods) • Simplification (fewer directives, articles, simplified “roadmap”) • Intent is to enhance flexibility and lower compliance costs while ensuring basic principles of equal treatment and transparency and enhancing competition – e-procurement – competitive dialogue – performance specifications, etc. EPUK Lecture 4 17

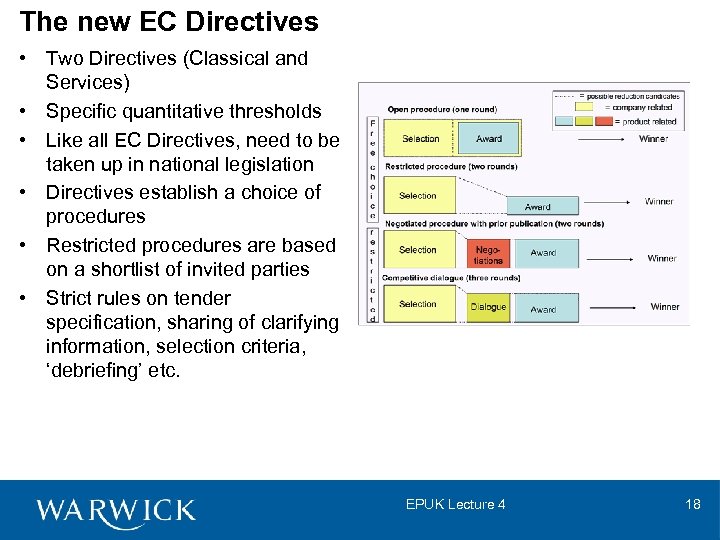

The new EC Directives • Two Directives (Classical and Services) • Specific quantitative thresholds • Like all EC Directives, need to be taken up in national legislation • Directives establish a choice of procedures • Restricted procedures are based on a shortlist of invited parties • Strict rules on tender specification, sharing of clarifying information, selection criteria, ‘debriefing’ etc. EPUK Lecture 4 18

The new EC Directives • Two Directives (Classical and Services) • Specific quantitative thresholds • Like all EC Directives, need to be taken up in national legislation • Directives establish a choice of procedures • Restricted procedures are based on a shortlist of invited parties • Strict rules on tender specification, sharing of clarifying information, selection criteria, ‘debriefing’ etc. EPUK Lecture 4 18

MEAT: most economically advantageous tender • Not clear that it is always best to choose the lowestprice bid. – – – Hidden tradeoffs (features, quality, time, certainty, etc. ) Non-monotone marginal expenditure curves Pressure of ‘customer 2’ (user) Securing ‘genuine’ competition and encouraging entry Externalities (e. g. interoperability) • What defines ‘economic advantage’? – Value for money – Different implications at specification and selection stages EPUK Lecture 4 19

MEAT: most economically advantageous tender • Not clear that it is always best to choose the lowestprice bid. – – – Hidden tradeoffs (features, quality, time, certainty, etc. ) Non-monotone marginal expenditure curves Pressure of ‘customer 2’ (user) Securing ‘genuine’ competition and encouraging entry Externalities (e. g. interoperability) • What defines ‘economic advantage’? – Value for money – Different implications at specification and selection stages EPUK Lecture 4 19

More meat… • • • Public contract award governed by Article 53 of Directive 2004/18/EC, which outlines two criteria: – Lowest price only; OR – Most Economically Advantageous Tender (MEAT) Procurement best practice indicates best value not usually achieved by lowest cost award. Article 53 does not define MEAT - it gives example criteria – Price – Quality – Technical merit – Aesthetic and functional characteristics – Environmental characteristics – Running costs – Cost-effectiveness – After-sales service – Technical assistance – Delivery date – Delivery period – Period of completion Often, other criteria (working/partner relationship, innovation, risk management, etc. ) added UK defines value-for-money as “the optimum combination of whole life costs and quality to meet the user requirement” EPUK Lecture 4 20

More meat… • • • Public contract award governed by Article 53 of Directive 2004/18/EC, which outlines two criteria: – Lowest price only; OR – Most Economically Advantageous Tender (MEAT) Procurement best practice indicates best value not usually achieved by lowest cost award. Article 53 does not define MEAT - it gives example criteria – Price – Quality – Technical merit – Aesthetic and functional characteristics – Environmental characteristics – Running costs – Cost-effectiveness – After-sales service – Technical assistance – Delivery date – Delivery period – Period of completion Often, other criteria (working/partner relationship, innovation, risk management, etc. ) added UK defines value-for-money as “the optimum combination of whole life costs and quality to meet the user requirement” EPUK Lecture 4 20