08cb496d8f49919612878458ccb1e96f.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 19

EC 307: Economic Policy in the UK Week 11: Procurement

EC 307: Economic Policy in the UK Week 11: Procurement

General outline, 1 • The procurement problem(s): – The political problem – procurement as a sure-fire source of deeply embarrassing stories – The practical problem – procurement as government business – The policy problem – procurement as an instrument of (environmental, industrial, innovation, trade) policy – The theoretical problem – procurement as an exercise in mechanism design • The simple theory of procurement – – – What is procured Who supplies it and why How is it procured What can go wrong? What can be done about it? • Procurement and competition EPUK Lecture 1 2

General outline, 1 • The procurement problem(s): – The political problem – procurement as a sure-fire source of deeply embarrassing stories – The practical problem – procurement as government business – The policy problem – procurement as an instrument of (environmental, industrial, innovation, trade) policy – The theoretical problem – procurement as an exercise in mechanism design • The simple theory of procurement – – – What is procured Who supplies it and why How is it procured What can go wrong? What can be done about it? • Procurement and competition EPUK Lecture 1 2

General outline, 2 • • • The historical laboratory – defence procurement The Modern challenges – e. Government, outsourcing, etc. The global constraints – the European Directives and the GPA The policy response – the Office of Government Commerce Some initial reading: – Laffont, Tirole: A Theory of Incentives in Procurement and Regulation, MIT Press, Chapters 1 and 2 – other references to be added – De Fraja and Hartley “Defence Procurement: Theory and UK Policy” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 12(4): 70 -88 – OECD Report on Competition and Procurement – on module website – UK National Audit Office: • Rapid support procurement http: //www. nao. org. uk/publications/nao_reports/03041161. pdf • IT procurement http: //www. nao. org. uk/publications/nao_reports/03 -04/0304877. pdf • OGC performance - http: //www. nao. org. uk/publications/nao_reports/03 -04/0304361 -i. pdf • Modernising Procurement - http: //www. nao. org. uk/publications/nao_reports/9899808. pdf – UK MOD - http: //www. mod. uk/issues/sdr/procurement. htm EPUK Lecture 1 3

General outline, 2 • • • The historical laboratory – defence procurement The Modern challenges – e. Government, outsourcing, etc. The global constraints – the European Directives and the GPA The policy response – the Office of Government Commerce Some initial reading: – Laffont, Tirole: A Theory of Incentives in Procurement and Regulation, MIT Press, Chapters 1 and 2 – other references to be added – De Fraja and Hartley “Defence Procurement: Theory and UK Policy” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 12(4): 70 -88 – OECD Report on Competition and Procurement – on module website – UK National Audit Office: • Rapid support procurement http: //www. nao. org. uk/publications/nao_reports/03041161. pdf • IT procurement http: //www. nao. org. uk/publications/nao_reports/03 -04/0304877. pdf • OGC performance - http: //www. nao. org. uk/publications/nao_reports/03 -04/0304361 -i. pdf • Modernising Procurement - http: //www. nao. org. uk/publications/nao_reports/9899808. pdf – UK MOD - http: //www. mod. uk/issues/sdr/procurement. htm EPUK Lecture 1 3

The procurement problems – faster, cheaper, better? • Horror stories: – – Waiting for a submarine, waiting for a plane The £ 100, 000 screwdriver – cost overruns IT procurement in the UK – why is it so hard Corruption and procurement • Procurement as government business: – – – – Who ‘owns’ the procurement function – customer 1 and customer 2 Procurement as part of outsourcing Value for money in procurement Procurement as risk-taking: innovative goods and services Risk transfer Collecting and exploiting market power Private sector examples – reverse auctions EPUK Lecture 1 4

The procurement problems – faster, cheaper, better? • Horror stories: – – Waiting for a submarine, waiting for a plane The £ 100, 000 screwdriver – cost overruns IT procurement in the UK – why is it so hard Corruption and procurement • Procurement as government business: – – – – Who ‘owns’ the procurement function – customer 1 and customer 2 Procurement as part of outsourcing Value for money in procurement Procurement as risk-taking: innovative goods and services Risk transfer Collecting and exploiting market power Private sector examples – reverse auctions EPUK Lecture 1 4

Problems, continued • Procurement as an instrument of policy – The demonstration effect: energy-efficient buildings, PNGV – The launching customer role – biometrics – “Jobs for the boys” and “Buy British” – procurement as: • • Disguised state aid (US aircraft, computers, etc. ) Structural policy (SME preference, national champions) Underwriter of venture capital Maintainer of industrial and research capabilities – Procurement and innovation policy (pull-through) – Procurement and trade policy: why and how much local preference? – Procurement and competition policy – more anon EPUK Lecture 1 5

Problems, continued • Procurement as an instrument of policy – The demonstration effect: energy-efficient buildings, PNGV – The launching customer role – biometrics – “Jobs for the boys” and “Buy British” – procurement as: • • Disguised state aid (US aircraft, computers, etc. ) Structural policy (SME preference, national champions) Underwriter of venture capital Maintainer of industrial and research capabilities – Procurement and innovation policy (pull-through) – Procurement and trade policy: why and how much local preference? – Procurement and competition policy – more anon EPUK Lecture 1 5

Procurement as a sandbox for theory • The contractarian perspective • The mechanism design perspective • Step 1: what are the objectives of procurement? – Value for money (VFM) – traditionally narrow, but raises deep questions about measurement of cost and value – Competition – strong belief in the efficacy of competition to resolve information asymmetry and monitoring problems associated with contract incompleteness – Innovation – to bring in better – or fit-for-purpose – solutions and to facilitate change management – Greening and other facets of ethical government – Maintaining sectors and competitiveness – Laying off risk – the ‘make or buy’ question – Security of supply – Things the market cannot (yet) supply (milspec) EPUK Lecture 1 6

Procurement as a sandbox for theory • The contractarian perspective • The mechanism design perspective • Step 1: what are the objectives of procurement? – Value for money (VFM) – traditionally narrow, but raises deep questions about measurement of cost and value – Competition – strong belief in the efficacy of competition to resolve information asymmetry and monitoring problems associated with contract incompleteness – Innovation – to bring in better – or fit-for-purpose – solutions and to facilitate change management – Greening and other facets of ethical government – Maintaining sectors and competitiveness – Laying off risk – the ‘make or buy’ question – Security of supply – Things the market cannot (yet) supply (milspec) EPUK Lecture 1 6

The procurement life-cycle • Step 2: what is procured? – Goods and services and whole systems – Procurement on the government’s own account or on behalf of others (e. g. NHS) – Procurement of R&D – Ongoing vs. strategic procurement • Step 3: the process – Identifying needs and formulating requirements – Market analysis – Choosing a mechanism (spot purchase, long-term contract, tender procedure(s), auction, competition…) – Specifying an offer – Evaluating the responses – Selection, negotiation and contracting – Monitoring – Acceptance – Subsequent exploitation – Re-tendering and lessons learnt EPUK Lecture 1 7

The procurement life-cycle • Step 2: what is procured? – Goods and services and whole systems – Procurement on the government’s own account or on behalf of others (e. g. NHS) – Procurement of R&D – Ongoing vs. strategic procurement • Step 3: the process – Identifying needs and formulating requirements – Market analysis – Choosing a mechanism (spot purchase, long-term contract, tender procedure(s), auction, competition…) – Specifying an offer – Evaluating the responses – Selection, negotiation and contracting – Monitoring – Acceptance – Subsequent exploitation – Re-tendering and lessons learnt EPUK Lecture 1 7

What’s different about the public sector? • Monopsony position • Non-transferable risk • (for some items) – Development cost >> unit cost – Many parallel ‘offices’ • Buying and selling on ‘mixed’ markets – Constraints on partnering – Difficulties in self-supply – Different opportunity cost of finance, legal position • • Informational and cultural asymmetries High costs of monitoring, negotiation, enforcement Market imperfections (esp. with ‘thin’ supply side) Some markets with special rules – e. g. defence EPUK Lecture 1 8

What’s different about the public sector? • Monopsony position • Non-transferable risk • (for some items) – Development cost >> unit cost – Many parallel ‘offices’ • Buying and selling on ‘mixed’ markets – Constraints on partnering – Difficulties in self-supply – Different opportunity cost of finance, legal position • • Informational and cultural asymmetries High costs of monitoring, negotiation, enforcement Market imperfections (esp. with ‘thin’ supply side) Some markets with special rules – e. g. defence EPUK Lecture 1 8

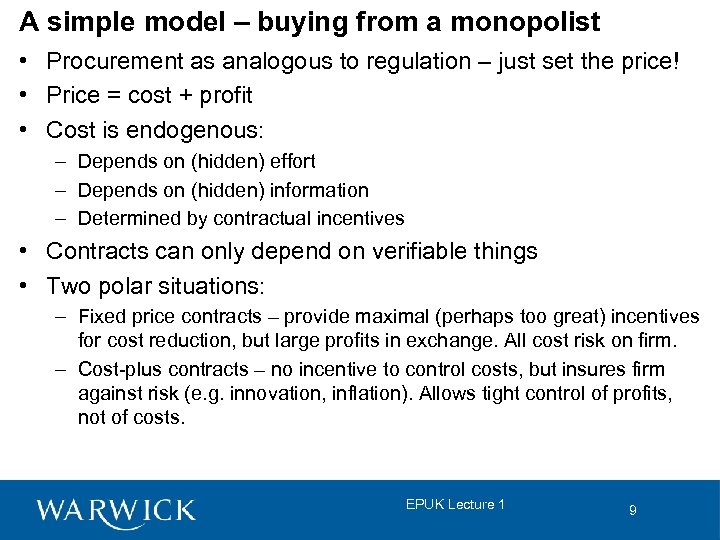

A simple model – buying from a monopolist • Procurement as analogous to regulation – just set the price! • Price = cost + profit • Cost is endogenous: – Depends on (hidden) effort – Depends on (hidden) information – Determined by contractual incentives • Contracts can only depend on verifiable things • Two polar situations: – Fixed price contracts – provide maximal (perhaps too great) incentives for cost reduction, but large profits in exchange. All cost risk on firm. – Cost-plus contracts – no incentive to control costs, but insures firm against risk (e. g. innovation, inflation). Allows tight control of profits, not of costs. EPUK Lecture 1 9

A simple model – buying from a monopolist • Procurement as analogous to regulation – just set the price! • Price = cost + profit • Cost is endogenous: – Depends on (hidden) effort – Depends on (hidden) information – Determined by contractual incentives • Contracts can only depend on verifiable things • Two polar situations: – Fixed price contracts – provide maximal (perhaps too great) incentives for cost reduction, but large profits in exchange. All cost risk on firm. – Cost-plus contracts – no incentive to control costs, but insures firm against risk (e. g. innovation, inflation). Allows tight control of profits, not of costs. EPUK Lecture 1 9

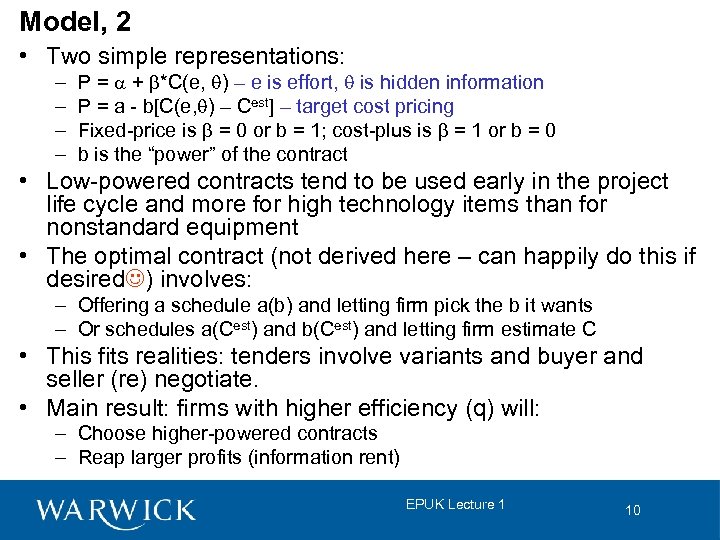

Model, 2 • Two simple representations: – – P = a + b*C(e, q) – e is effort, q is hidden information P = a - b[C(e, q) – Cest] – target cost pricing Fixed-price is b = 0 or b = 1; cost-plus is b = 1 or b = 0 b is the “power” of the contract • Low-powered contracts tend to be used early in the project life cycle and more for high technology items than for nonstandard equipment • The optimal contract (not derived here – can happily do this if desired ) involves: – Offering a schedule a(b) and letting firm pick the b it wants – Or schedules a(Cest) and b(Cest) and letting firm estimate C • This fits realities: tenders involve variants and buyer and seller (re) negotiate. • Main result: firms with higher efficiency (q) will: – Choose higher-powered contracts – Reap larger profits (information rent) EPUK Lecture 1 10

Model, 2 • Two simple representations: – – P = a + b*C(e, q) – e is effort, q is hidden information P = a - b[C(e, q) – Cest] – target cost pricing Fixed-price is b = 0 or b = 1; cost-plus is b = 1 or b = 0 b is the “power” of the contract • Low-powered contracts tend to be used early in the project life cycle and more for high technology items than for nonstandard equipment • The optimal contract (not derived here – can happily do this if desired ) involves: – Offering a schedule a(b) and letting firm pick the b it wants – Or schedules a(Cest) and b(Cest) and letting firm estimate C • This fits realities: tenders involve variants and buyer and seller (re) negotiate. • Main result: firms with higher efficiency (q) will: – Choose higher-powered contracts – Reap larger profits (information rent) EPUK Lecture 1 10

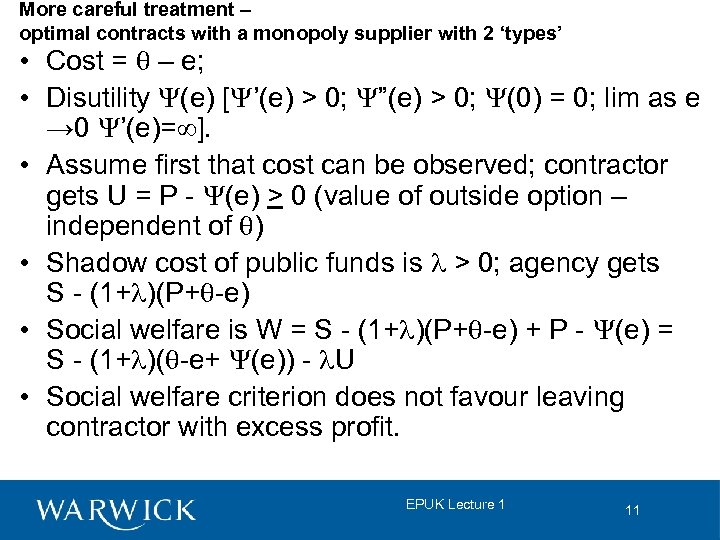

More careful treatment – optimal contracts with a monopoly supplier with 2 ‘types’ • Cost = q – e; • Disutility Y(e) [Y’(e) > 0; Y”(e) > 0; Y(0) = 0; lim as e → 0 Y’(e)= ]. • Assume first that cost can be observed; contractor gets U = P - Y(e) > 0 (value of outside option – independent of q) • Shadow cost of public funds is l > 0; agency gets S - (1+l)(P+q-e) • Social welfare is W = S - (1+l)(P+q-e) + P - Y(e) = S - (1+l)(q-e+ Y(e)) - l. U • Social welfare criterion does not favour leaving contractor with excess profit. EPUK Lecture 1 11

More careful treatment – optimal contracts with a monopoly supplier with 2 ‘types’ • Cost = q – e; • Disutility Y(e) [Y’(e) > 0; Y”(e) > 0; Y(0) = 0; lim as e → 0 Y’(e)= ]. • Assume first that cost can be observed; contractor gets U = P - Y(e) > 0 (value of outside option – independent of q) • Shadow cost of public funds is l > 0; agency gets S - (1+l)(P+q-e) • Social welfare is W = S - (1+l)(P+q-e) + P - Y(e) = S - (1+l)(q-e+ Y(e)) - l. U • Social welfare criterion does not favour leaving contractor with excess profit. EPUK Lecture 1 11

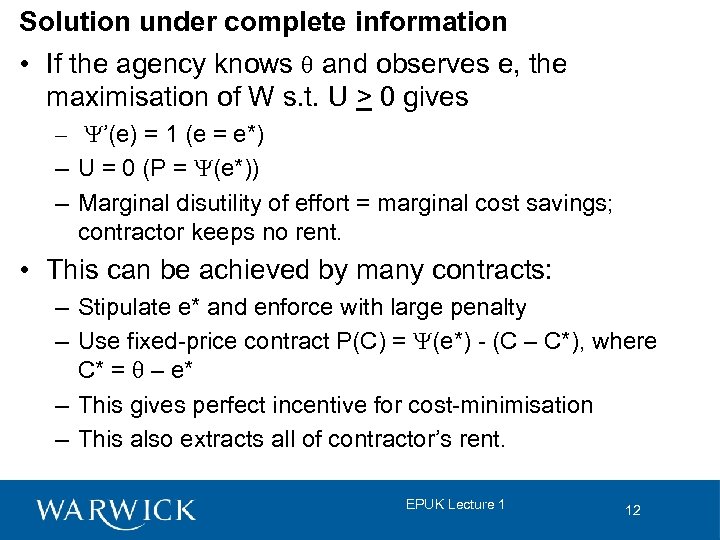

Solution under complete information • If the agency knows q and observes e, the maximisation of W s. t. U > 0 gives – Y’(e) = 1 (e = e*) – U = 0 (P = Y(e*)) – Marginal disutility of effort = marginal cost savings; contractor keeps no rent. • This can be achieved by many contracts: – Stipulate e* and enforce with large penalty – Use fixed-price contract P(C) = Y(e*) - (C – C*), where C* = q – e* – This gives perfect incentive for cost-minimisation – This also extracts all of contractor’s rent. EPUK Lecture 1 12

Solution under complete information • If the agency knows q and observes e, the maximisation of W s. t. U > 0 gives – Y’(e) = 1 (e = e*) – U = 0 (P = Y(e*)) – Marginal disutility of effort = marginal cost savings; contractor keeps no rent. • This can be achieved by many contracts: – Stipulate e* and enforce with large penalty – Use fixed-price contract P(C) = Y(e*) - (C – C*), where C* = q – e* – This gives perfect incentive for cost-minimisation – This also extracts all of contractor’s rent. EPUK Lecture 1 12

Incomplete information • • • If the agency knows that q is either high (q+) or low (q-) and observes cost. Contract is based on two observed variables P and C only In principle, both ‘depend’ on the contractor’s type: P(q), C(q) Let U(q) = P(q) - Y(q – C(q)) be the contactor’s ‘truthful’ utility Incentive compatibility (IC): each type of firm prefers to be truthful: – – P(q+) - Y(q+ – C(q+)) > P(q-) - Y(q+ – C(q-)) P(q-) - Y(q- – C(q-)) > P(q+) - Y(q- – C(q+)) Or Y(q- – C+) + Y(q+ – C-) - Y(q+ – C+) - Y(q- – C-) > 0 …which shows (by integration) that C+ > C- - the optimal cost is nondecreasing in type. • We also need individual rationality (IR) – each type gets at least 0 • In the event, we only need individual rationality for the low type and incentive compatibility for the high type • The social welfare function when the contractor has type q is now: W(q) = S – (1+l)[P(q) + Y(q-C(q))] – l. U(q) • Suppose the agency thinks that the contractor is inefficient (low q) with probability p and tries to maximise W subject to IC and IR. EPUK Lecture 1 13

Incomplete information • • • If the agency knows that q is either high (q+) or low (q-) and observes cost. Contract is based on two observed variables P and C only In principle, both ‘depend’ on the contractor’s type: P(q), C(q) Let U(q) = P(q) - Y(q – C(q)) be the contactor’s ‘truthful’ utility Incentive compatibility (IC): each type of firm prefers to be truthful: – – P(q+) - Y(q+ – C(q+)) > P(q-) - Y(q+ – C(q-)) P(q-) - Y(q- – C(q-)) > P(q+) - Y(q- – C(q+)) Or Y(q- – C+) + Y(q+ – C-) - Y(q+ – C+) - Y(q- – C-) > 0 …which shows (by integration) that C+ > C- - the optimal cost is nondecreasing in type. • We also need individual rationality (IR) – each type gets at least 0 • In the event, we only need individual rationality for the low type and incentive compatibility for the high type • The social welfare function when the contractor has type q is now: W(q) = S – (1+l)[P(q) + Y(q-C(q))] – l. U(q) • Suppose the agency thinks that the contractor is inefficient (low q) with probability p and tries to maximise W subject to IC and IR. EPUK Lecture 1 13

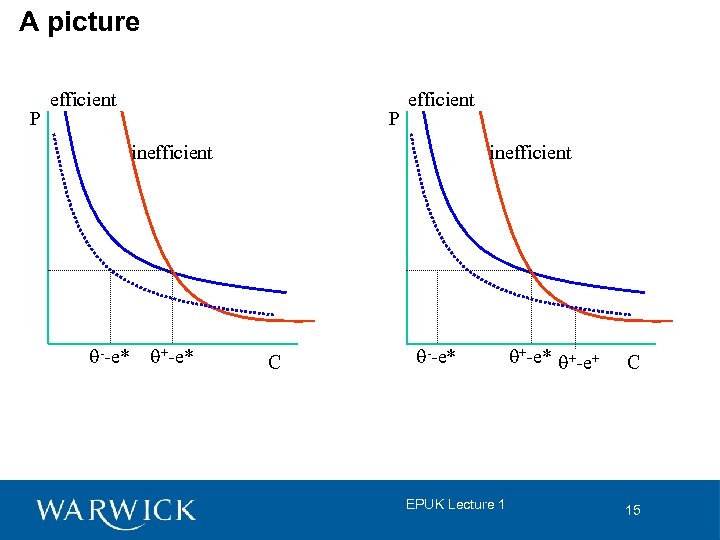

Solving the problem • Rewrite IC for high type as: U- > U+ + F(e+), where F(e) = Y(e) - Y((e – q+ + q-) – this function is increasing and convex, so the objective is concave • The function F determines the rent enjoyed by the efficient type relative to the inefficient type via the ‘slack’ – reduced disutility of effort. The fact that is is increasing means that the efficient firms gets more rent, the higher is the power of the scheme. • The agency must now choose the cost and utility levels for both contractor types to maximise welfare s. t. the relevant constraints. This gives: – Y’(q- – C-) = 1 (e- = e*) – Y’(q+ – C+) = 1 – (l/(1+l))(p/(1 -p))F’(q+ - C+), so e+ < e* • The efficient type devotes efficient effort and gets positive rent • The inefficient type exerts less effort and gets no rent. • The rent is there because the efficient type can (more cheaply) imitate the inefficient type EPUK Lecture 1 14

Solving the problem • Rewrite IC for high type as: U- > U+ + F(e+), where F(e) = Y(e) - Y((e – q+ + q-) – this function is increasing and convex, so the objective is concave • The function F determines the rent enjoyed by the efficient type relative to the inefficient type via the ‘slack’ – reduced disutility of effort. The fact that is is increasing means that the efficient firms gets more rent, the higher is the power of the scheme. • The agency must now choose the cost and utility levels for both contractor types to maximise welfare s. t. the relevant constraints. This gives: – Y’(q- – C-) = 1 (e- = e*) – Y’(q+ – C+) = 1 – (l/(1+l))(p/(1 -p))F’(q+ - C+), so e+ < e* • The efficient type devotes efficient effort and gets positive rent • The inefficient type exerts less effort and gets no rent. • The rent is there because the efficient type can (more cheaply) imitate the inefficient type EPUK Lecture 1 14

A picture P efficient inefficient q--e* q+-e* inefficient C q--e* EPUK Lecture 1 q+-e* q+-e+ C 15

A picture P efficient inefficient q--e* q+-e* inefficient C q--e* EPUK Lecture 1 q+-e* q+-e+ C 15

Some methodology observations • The equilibrium is separating – different types choose different contracts and thus reveal their types. • The agency would want to renegotiate – reducing the price on offer – this is ruled out by assumption (legal or reputation reasons) • The direct mechanism is to offer a supply contract P(C) – an alternative is to offer the contract based on q: {P(q), C(q)} – the firm accepts by announcing qo, producing at cost C(qo) and getting the agreed price. The parties could renegotiate between the announcement and the production. If the firm announces q- there is no scope for this, but if the firm has revealed q+ both parties could benefit from renegotiation. Because the agency and the firm would prefer to have the firm exert more effort in exchange for more money – but this would destroy incentive compatibility. • This happens in real contracts where there is initial R&D. EPUK Lecture 1 16

Some methodology observations • The equilibrium is separating – different types choose different contracts and thus reveal their types. • The agency would want to renegotiate – reducing the price on offer – this is ruled out by assumption (legal or reputation reasons) • The direct mechanism is to offer a supply contract P(C) – an alternative is to offer the contract based on q: {P(q), C(q)} – the firm accepts by announcing qo, producing at cost C(qo) and getting the agreed price. The parties could renegotiate between the announcement and the production. If the firm announces q- there is no scope for this, but if the firm has revealed q+ both parties could benefit from renegotiation. Because the agency and the firm would prefer to have the firm exert more effort in exchange for more money – but this would destroy incentive compatibility. • This happens in real contracts where there is initial R&D. EPUK Lecture 1 16

Interpretation • This is a strength, not a weakness of fixed-price contracts: it amounts to gain sharing between firm and customer – profit and power are both correlated with (unobservable) efficiency (q). • This is only optimal if the firm’s profits do not damage the customer’s objective function - a function of the ‘shadow price of public funds’ – Side remark – this should be the internal rate of return on the best unfunded public project – The gain sharing holds if b < 1, but there is ‘no distortion at the top’ (b = 1 or q = qmax) • If there is no shadow distortion, fixed price contracts are always optimal – Maximal incentive for production efficiency – Firm’s rent is “just a transfer” – … but there is always at least a political shadow price EPUK Lecture 1 17

Interpretation • This is a strength, not a weakness of fixed-price contracts: it amounts to gain sharing between firm and customer – profit and power are both correlated with (unobservable) efficiency (q). • This is only optimal if the firm’s profits do not damage the customer’s objective function - a function of the ‘shadow price of public funds’ – Side remark – this should be the internal rate of return on the best unfunded public project – The gain sharing holds if b < 1, but there is ‘no distortion at the top’ (b = 1 or q = qmax) • If there is no shadow distortion, fixed price contracts are always optimal – Maximal incentive for production efficiency – Firm’s rent is “just a transfer” – … but there is always at least a political shadow price EPUK Lecture 1 17

Other remarks and some problems that arise • Contracting agencies do not maximise societal welfare • There is a possibility of deadweight loss • There are possible dynamic distortions as well – if we take the regulatory analogy seriously, we could see an Averch. Johnson effect • The capture problem: the agency’s objective functions grows to resemble the supplier’s: – – Corruption, bribes, political power Revolving door Personal relationships Mutual understanding (trade-off between contractual rigour and partnership) – Information distortion EPUK Lecture 1 18

Other remarks and some problems that arise • Contracting agencies do not maximise societal welfare • There is a possibility of deadweight loss • There are possible dynamic distortions as well – if we take the regulatory analogy seriously, we could see an Averch. Johnson effect • The capture problem: the agency’s objective functions grows to resemble the supplier’s: – – Corruption, bribes, political power Revolving door Personal relationships Mutual understanding (trade-off between contractual rigour and partnership) – Information distortion EPUK Lecture 1 18

More generic problems • Static problems – Hold-up – Foreclosure – Lock in • Dynamic problems – Inappropriate (too weak or too strong) incentives to minimise cost – Mismatch of marginal cost and marginal willingness to pay (monopoly pricing, reversal of agency, allocational inefficiency) – Loss of effort/innovation incentives near the end of the contract – or too-strong incumbent advantage – Amount, nature and ownership of intellectual property rights and other rights to intangible property created during the contract EPUK Lecture 1 19

More generic problems • Static problems – Hold-up – Foreclosure – Lock in • Dynamic problems – Inappropriate (too weak or too strong) incentives to minimise cost – Mismatch of marginal cost and marginal willingness to pay (monopoly pricing, reversal of agency, allocational inefficiency) – Loss of effort/innovation incentives near the end of the contract – or too-strong incumbent advantage – Amount, nature and ownership of intellectual property rights and other rights to intangible property created during the contract EPUK Lecture 1 19