b623581221967ce1fe886c2661cf8885.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 21

Duke Systems GENI Federation Basics Jeff Chase Duke University

Preface This slide deck has some introductory slides for a longer series on authorization and trust management in GENI. It contains: § A few Big Picture slides from the GPO, which I find useful § Basic GENI concepts: aggregates, slices, projects, clearinghouse § Some basic material defining terms and concepts for trust management based on principals speaking with public keys. There shouldn’t be anything new and controversial here for anybody who has been involved in the GENI process. But it isn’t a good introduction to GENI either. It’s only purpose is to ground some terms and concepts for a larger discussion.

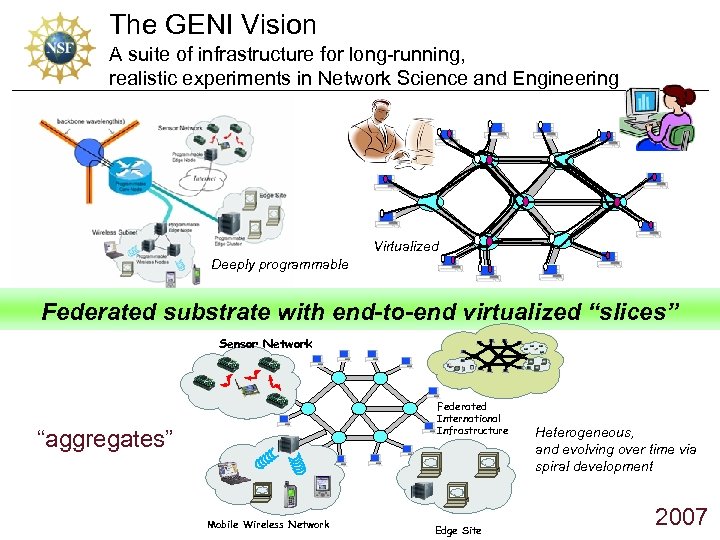

The GENI Vision A suite of infrastructure for long-running, realistic experiments in Network Science and Engineering Virtualized Deeply programmable Federated substrate with end-to-end virtualized “slices” Sensor Network Federated International Infrastructure “aggregates” Mobile Wireless Network Edge Site Heterogeneous, and evolving over time via spiral development 3 2007

“GENI from First Principals” This series is about trust management in GENI. • How to think about principals and trust • Declarative trust policies with automated inference • Federation architecture addressing these goals: 1. Be flexible enough to represent a wide range of trust structures for multi-domain infrastructure services. 2. Implement GENI spiral 4 governance mandate as deployment-time policy with a rigorous specification. 3. Evolve to decentralize GENI-like services over time. 4. Grow richer structures around GENI by allowing others to join the system and contribute on their own terms. 5. Declare new trust structures without changing code.

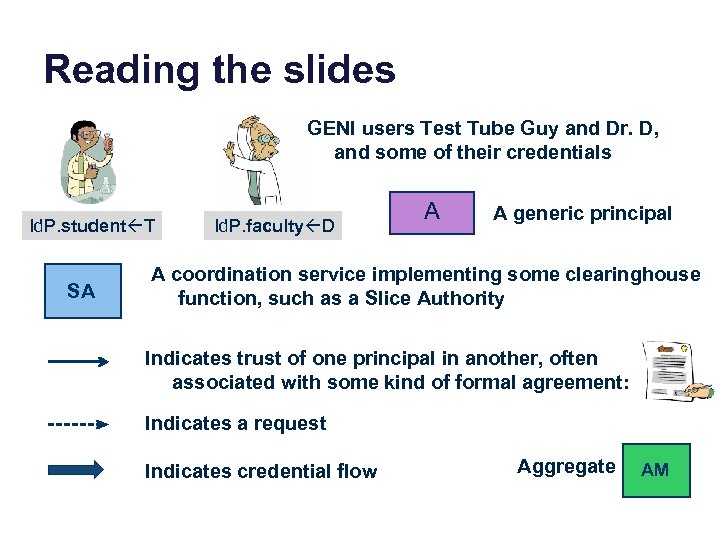

Reading the slides GENI users Test Tube Guy and Dr. D, and some of their credentials Id. P. student T SA Id. P. faculty D A A generic principal A coordination service implementing some clearinghouse function, such as a Slice Authority Indicates trust of one principal in another, often associated with some kind of formal agreement: Indicates a request Indicates credential flow Aggregate AM

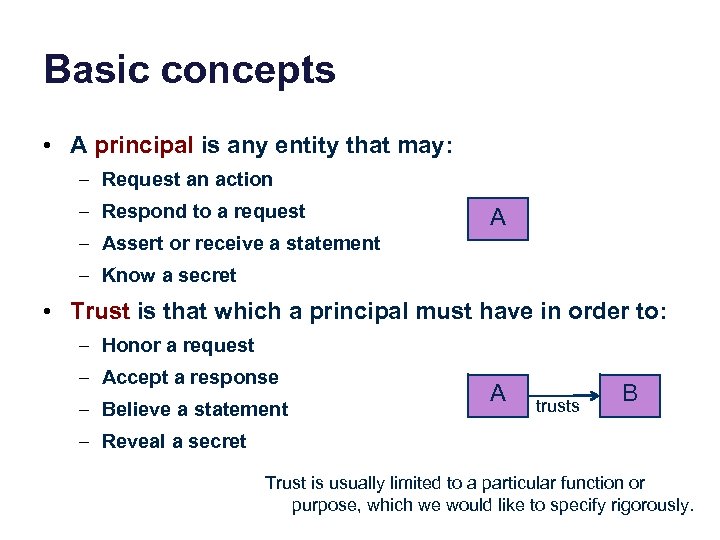

Basic concepts • A principal is any entity that may: – Request an action – Respond to a request A – Assert or receive a statement – Know a secret • Trust is that which a principal must have in order to: – Honor a request – Accept a response – Believe a statement A trusts B – Reveal a secret Trust is usually limited to a particular function or purpose, which we would like to specify rigorously.

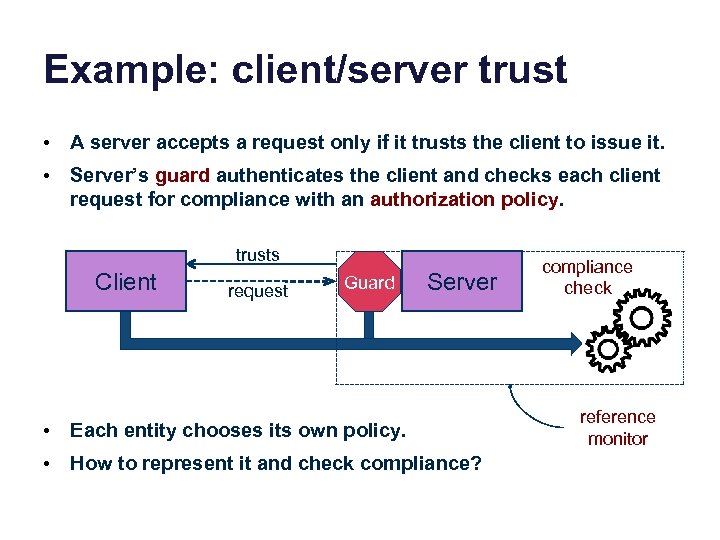

Example: client/server trust • A server accepts a request only if it trusts the client to issue it. • Server’s guard authenticates the client and checks each client request for compliance with an authorization policy. trusts Client request Guard Server • Each entity chooses its own policy. • How to represent it and check compliance? compliance check reference monitor

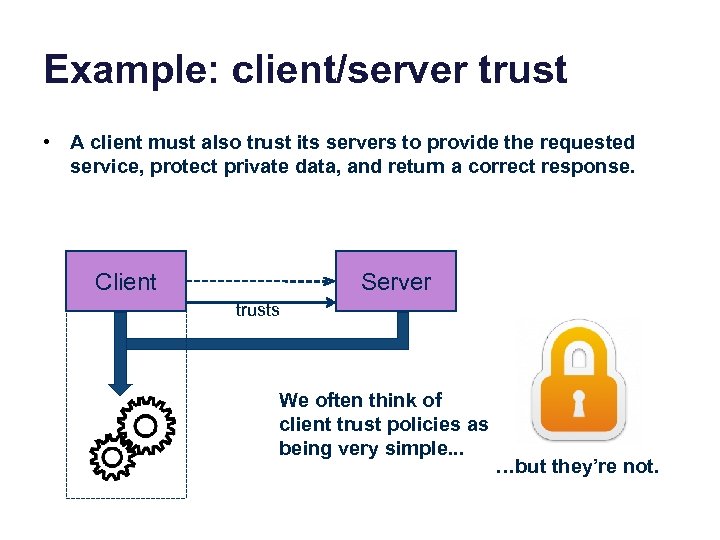

Example: client/server trust • A client must also trust its servers to provide the requested service, protect private data, and return a correct response. Client Server trusts We often think of C client trust policies as being very simple. . . …but they’re not.

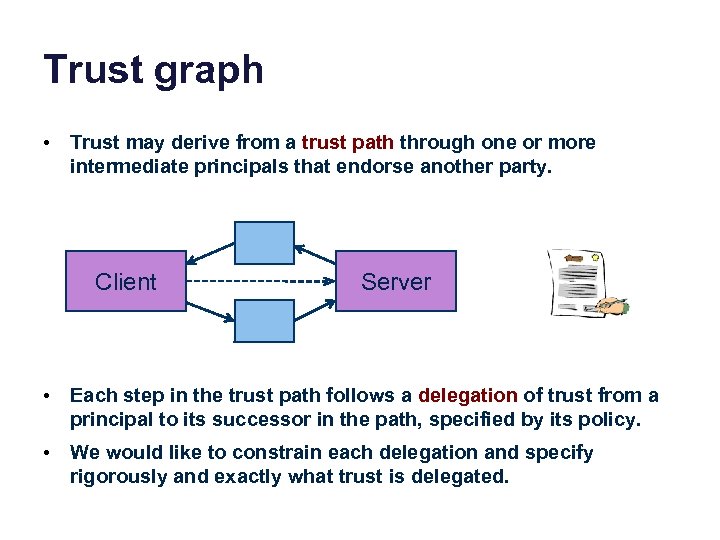

Trust graph • Trust may derive from a trust path through one or more intermediate principals that endorse another party. Client Server • Each step in the trust path follows a delegation of trust from a principal to its successor in the path, specified by its policy. • We would like to constrain each delegation and specify rigorously and exactly what trust is delegated.

GENI on the back of a napkin Chip Elliott @ GEC 4 Sponsored by the National Science Foundation Standard issue BBN napkin 10

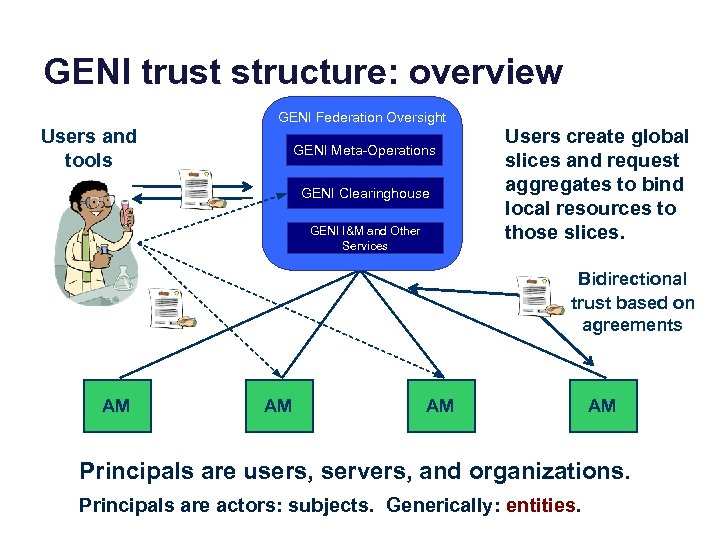

GENI trust structure: overview Users and tools GENI Federation Oversight GENI Meta-Operations GENI Clearinghouse GENI I&M and Other Services Users create global slices and request aggregates to bind local resources to those slices. Bidirectional trust based on agreements AM AM Principals are users, servers, and organizations. Principals are actors: subjects. Generically: entities.

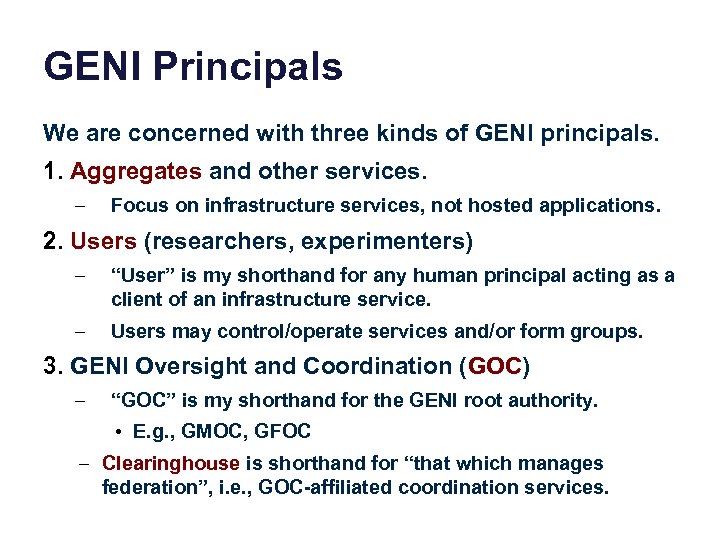

GENI Principals We are concerned with three kinds of GENI principals. 1. Aggregates and other services. – Focus on infrastructure services, not hosted applications. 2. Users (researchers, experimenters) – “User” is my shorthand for any human principal acting as a client of an infrastructure service. – Users may control/operate services and/or form groups. 3. GENI Oversight and Coordination (GOC) – “GOC” is my shorthand for the GENI root authority. • E. g. , GMOC, GFOC – Clearinghouse is shorthand for “that which manages federation”, i. e. , GOC-affiliated coordination services.

Slices • Resources are allocated to slices. – Each slice is created by a user, who owns it. – The slice owner may delegate permissions to operate on the slice. • A slice can host an application or service. – In principle, slices (or hosted services) can be subjects in the authorization framework. – Out of scope for now… • A slice is a global object that is a target of local operations at each aggregate.

Slices as principals • Can user software running within a slice invoke GENI interfaces? • Can slices offer infrastructure services? • In principle, slices can be subjects in the authorization framework. – This will be useful. – The question of how to build trust in slices (e. g. , through attestation) is an important and interesting research topic. – But this topic is out of scope for now. • The problem with slices as principals is that we have little basis to say anything about any public keys they speak with, or what trust to place in those keys.

Projects • All GENI activity is organized into projects. – Clearinghouse service registers/endorses projects – Every user action is taken within the scope of a project. • Each project has a designated leader (e. g. , PI). – The leader is accountable for activity in the project. – The leader may set policies for the project. – The leader may delegate management rights and/or organize the project and its members into subgroups. • GENI policies may consider project identity, e. g. , for resource allocation as well as authorization.

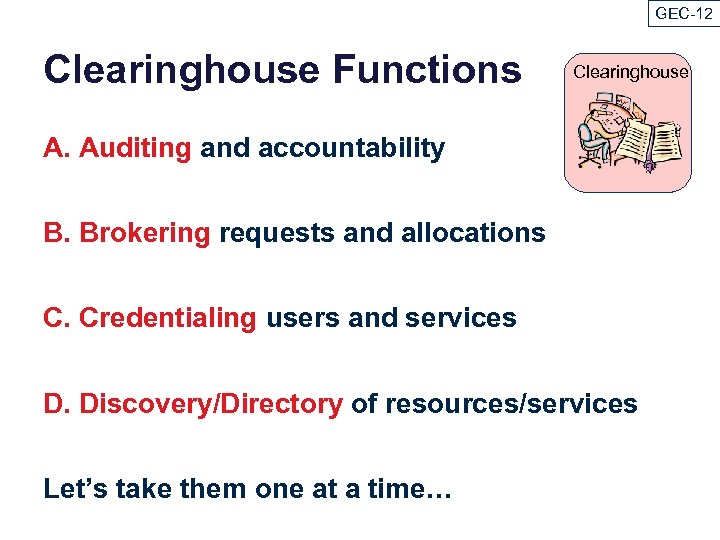

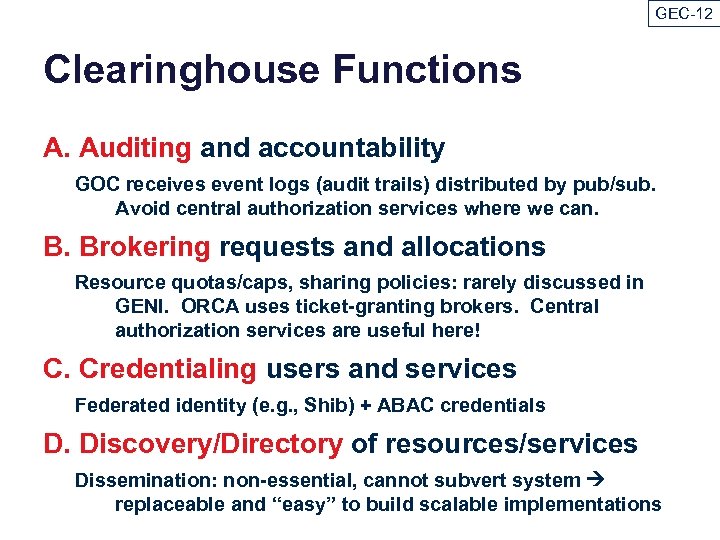

GEC-12 Clearinghouse Functions Clearinghouse A. Auditing and accountability B. Brokering requests and allocations C. Credentialing users and services D. Discovery/Directory of resources/services Let’s take them one at a time…

GEC-12 Clearinghouse Functions A. Auditing and accountability GOC receives event logs (audit trails) distributed by pub/sub. Avoid central authorization services where we can. B. Brokering requests and allocations Resource quotas/caps, sharing policies: rarely discussed in GENI. ORCA uses ticket-granting brokers. Central authorization services are useful here! C. Credentialing users and services Federated identity (e. g. , Shib) + ABAC credentials D. Discovery/Directory of resources/services Dissemination: non-essential, cannot subvert system replaceable and “easy” to build scalable implementations

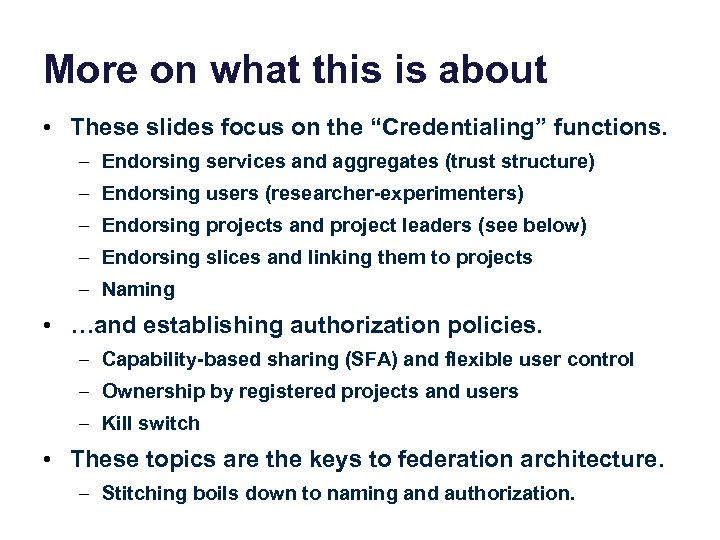

More on what this is about • These slides focus on the “Credentialing” functions. – Endorsing services and aggregates (trust structure) – Endorsing users (researcher-experimenters) – Endorsing projects and project leaders (see below) – Endorsing slices and linking them to projects – Naming • …and establishing authorization policies. – Capability-based sharing (SFA) and flexible user control – Ownership by registered projects and users – Kill switch • These topics are the keys to federation architecture. – Stitching boils down to naming and authorization.

PKI? • We can build an architecture around this trust model using either: 1. SSL communication with an always-on server for each delegating principal; 2. signed assertions with asymmetric crypto (PKI); 3. all of the above. • Each choice involves some painful tradeoffs. • We revisit these tradeoffs later…. CA

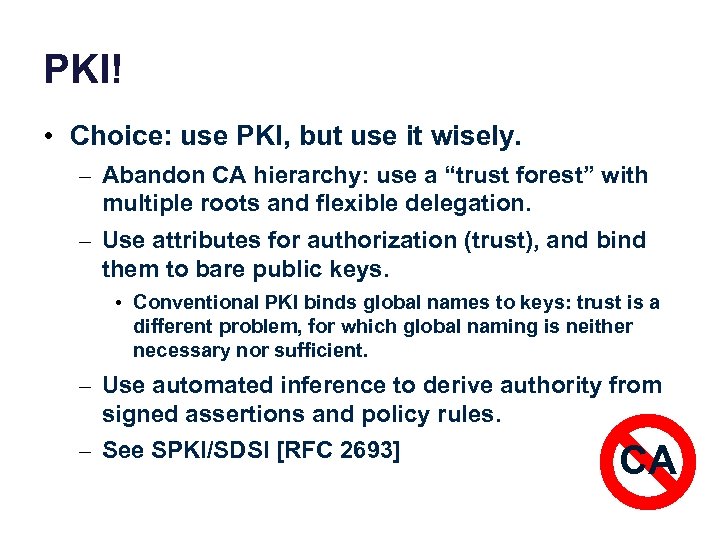

PKI! • Choice: use PKI, but use it wisely. – Abandon CA hierarchy: use a “trust forest” with multiple roots and flexible delegation. – Use attributes for authorization (trust), and bind them to bare public keys. • Conventional PKI binds global names to keys: trust is a different problem, for which global naming is neither necessary nor sufficient. – Use automated inference to derive authority from signed assertions and policy rules. – See SPKI/SDSI [RFC 2693] CA

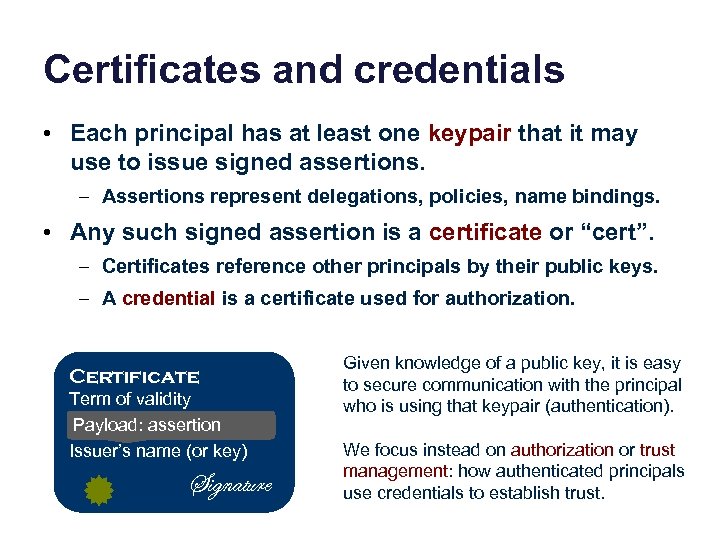

Certificates and credentials • Each principal has at least one keypair that it may use to issue signed assertions. – Assertions represent delegations, policies, name bindings. • Any such signed assertion is a certificate or “cert”. – Certificates reference other principals by their public keys. – A credential is a certificate used for authorization. Certificate Term of validity Payload: assertion Issuer’s name (or key) Signature Given knowledge of a public key, it is easy to secure communication with the principal who is using that keypair (authentication). We focus instead on authorization or trust management: how authenticated principals use credentials to establish trust.

b623581221967ce1fe886c2661cf8885.ppt