Drug trafficking in Central Asia and its implications.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 30

Drug trafficking in Central Asia and its implications

Drug trafficking in Central Asia and its implications

Outline of the lecture 1. Background of drug trade and trafficking in Central Asia. 2. The drug routes from Central Asia to Europe and elsewhere. 3. Drug trafficking in Afghanistan and foreign involvement. 4. Regional impact of the Afghan heroin trade. 5. Anti drug trafficking efforts in the countries of Central Asia. 6. The fight against drug trafficking in Kazakhstan.

Outline of the lecture 1. Background of drug trade and trafficking in Central Asia. 2. The drug routes from Central Asia to Europe and elsewhere. 3. Drug trafficking in Afghanistan and foreign involvement. 4. Regional impact of the Afghan heroin trade. 5. Anti drug trafficking efforts in the countries of Central Asia. 6. The fight against drug trafficking in Kazakhstan.

The Silk Road which once brought prosperity to Central Asia in the silk trade is now a highway for drugs from Afghanistan to Russia that has contributed to economic, political and social problems in the region. The drug trade is proliferating in Central Asia because of its weak states and geo-strategic location. The low volume of drug seizures (about 4 percent of the estimated total opiate flows) indicates the lack of state power to regulate Central Asian borders as well as the corruption of its officials. The propagation of the drug trade perpetuates the weakness of Central Asian states by destabilizing the region through financing militant Islamic groups’ campaigns, increasing drug abuse, and the spread of AIDS/HIV.

The Silk Road which once brought prosperity to Central Asia in the silk trade is now a highway for drugs from Afghanistan to Russia that has contributed to economic, political and social problems in the region. The drug trade is proliferating in Central Asia because of its weak states and geo-strategic location. The low volume of drug seizures (about 4 percent of the estimated total opiate flows) indicates the lack of state power to regulate Central Asian borders as well as the corruption of its officials. The propagation of the drug trade perpetuates the weakness of Central Asian states by destabilizing the region through financing militant Islamic groups’ campaigns, increasing drug abuse, and the spread of AIDS/HIV.

A large factor in the development of the drug trade in Central Asia is due to the region’s geography. Three of Central Asia’s southern states, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, share a collective border of about 3, 000 km with Afghanistan, which produces about 70 percent of the world’s heroin. An estimated 99 percent of Central Asia’s opiates originate from Afghanistan. Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Kazakhstan share a border with the Chinese province, Xinjiang, through which drug traffickers access major opiate producers such as Laos, Thailand Myanmar. Central Asia’s proximity to these states makes the region a hub for the drug trade throughout the world. During the Soviet era, Central Asia’s border to Afghanistan was mostly blocked off with little cross-border trade or travel. When Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the border began to open up. Veterans from the war started to bring back heroin in small quantities, but as soon as its potential large profits were realized, criminal groups took over the trade. Soviet Union created Central Asian states, often without ethnic or topographical considerations, causing them to be notoriously weak.

A large factor in the development of the drug trade in Central Asia is due to the region’s geography. Three of Central Asia’s southern states, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, share a collective border of about 3, 000 km with Afghanistan, which produces about 70 percent of the world’s heroin. An estimated 99 percent of Central Asia’s opiates originate from Afghanistan. Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Kazakhstan share a border with the Chinese province, Xinjiang, through which drug traffickers access major opiate producers such as Laos, Thailand Myanmar. Central Asia’s proximity to these states makes the region a hub for the drug trade throughout the world. During the Soviet era, Central Asia’s border to Afghanistan was mostly blocked off with little cross-border trade or travel. When Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the border began to open up. Veterans from the war started to bring back heroin in small quantities, but as soon as its potential large profits were realized, criminal groups took over the trade. Soviet Union created Central Asian states, often without ethnic or topographical considerations, causing them to be notoriously weak.

With the downfall of the Soviet Union’s, poor border delimitations, transition to a capitalist economy and absence of historical statehood, led the Central Asian economy to collapse and political situation to become chaotic. Disadvantaged people in the region turned to the drug trade for profit and took advantage of the lack of border controls. Drugs became and continue to be a major source of funding for Islamic militant groups and warlords trying to gain control in the region. These militant groups, which the international community often deem as terrorist groups, use drugs to finance their campaigns. As Abdurahim Kakharov, a deputy interior minister of Tajikistan said in 2000 "terrorism, organized crime and the illegal drug trade are one interrelated problem. ” The Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), classified as a terrorist organization by the Clinton administration in 2000, is deeply involved with drug trafficking. Although the IMU, whose power was at its peak in the late 1990 s, claimed to fight against the region’s civil government in the name of the caliphate, it also appeared to be highly motivated by the drug trade.

With the downfall of the Soviet Union’s, poor border delimitations, transition to a capitalist economy and absence of historical statehood, led the Central Asian economy to collapse and political situation to become chaotic. Disadvantaged people in the region turned to the drug trade for profit and took advantage of the lack of border controls. Drugs became and continue to be a major source of funding for Islamic militant groups and warlords trying to gain control in the region. These militant groups, which the international community often deem as terrorist groups, use drugs to finance their campaigns. As Abdurahim Kakharov, a deputy interior minister of Tajikistan said in 2000 "terrorism, organized crime and the illegal drug trade are one interrelated problem. ” The Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), classified as a terrorist organization by the Clinton administration in 2000, is deeply involved with drug trafficking. Although the IMU, whose power was at its peak in the late 1990 s, claimed to fight against the region’s civil government in the name of the caliphate, it also appeared to be highly motivated by the drug trade.

The IMU had alliances with the Taliban government and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan along with members of Tajik government from fighting together in the Tajik civil war. This allowed the IMU to easily transport drugs from Afghanistan and Tajikistan. Before the U. S military dismantled it in 2001, the IMU frequently made small incursions in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan around August, after the harvest of heroin. Arguably, the IMU used incursions to create instability in the states and distract law enforcement to more easily transport the new heroin harvests. The UNODC estimates that the IMU brought in 60 percent of the heroin traffic in the region. The IMU’s deep involvement in the drug trade indicates that it may have focused more on criminal activities than political and religious aims. Aside from militant groups, government officials at all levels are involved in the illicit drug trade in Central Asia. The collapse of economies post-Soviet Union leads many low-paid government authorities to corruption. They are often given bribes to look the other way as smugglers transport drugs through the border.

The IMU had alliances with the Taliban government and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan along with members of Tajik government from fighting together in the Tajik civil war. This allowed the IMU to easily transport drugs from Afghanistan and Tajikistan. Before the U. S military dismantled it in 2001, the IMU frequently made small incursions in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan around August, after the harvest of heroin. Arguably, the IMU used incursions to create instability in the states and distract law enforcement to more easily transport the new heroin harvests. The UNODC estimates that the IMU brought in 60 percent of the heroin traffic in the region. The IMU’s deep involvement in the drug trade indicates that it may have focused more on criminal activities than political and religious aims. Aside from militant groups, government officials at all levels are involved in the illicit drug trade in Central Asia. The collapse of economies post-Soviet Union leads many low-paid government authorities to corruption. They are often given bribes to look the other way as smugglers transport drugs through the border.

Fear of retaliating violence from drug lords also factors in the corruption of lowlevel officials. Corruption in the region, however, has evolved from passive low-level bribing to the direct involvement of state institutions and senior government officials. In 2001, the secretary of Tajikistan’s Security Council admitted that many of its government’s representatives are involved in the drug trade. Also pointing to highlevel government corruption in the drug trade, Turkmenistan’s president, Saparmurat Niyazov, publicly declared that smoking opium was healthy. Central Asian state governments tend to have low drug confiscation levels, as officials only use the arrests to provide an appearance of fighting drugs and to ensure a state monopoly on the trade. For instance, although trafficking has increased since 2001, the number of opiate seizures in Uzbekistan fell from 3, 617 kg in 2001 to 1, 298 kg in 2008, while heroin confiscations remain constant.

Fear of retaliating violence from drug lords also factors in the corruption of lowlevel officials. Corruption in the region, however, has evolved from passive low-level bribing to the direct involvement of state institutions and senior government officials. In 2001, the secretary of Tajikistan’s Security Council admitted that many of its government’s representatives are involved in the drug trade. Also pointing to highlevel government corruption in the drug trade, Turkmenistan’s president, Saparmurat Niyazov, publicly declared that smoking opium was healthy. Central Asian state governments tend to have low drug confiscation levels, as officials only use the arrests to provide an appearance of fighting drugs and to ensure a state monopoly on the trade. For instance, although trafficking has increased since 2001, the number of opiate seizures in Uzbekistan fell from 3, 617 kg in 2001 to 1, 298 kg in 2008, while heroin confiscations remain constant.

The illicit drug trade has created adverse social effects in Central Asia. The number of registered drug users in the region has increased dramatically since 1990 as the drug trafficking has made drugs more widely available, which in turn lowers the cost, promoting abuse. In 1996 there were about 40, 000 registered drug users, while in 2006 there were over 100, 000 registered users. This rapid increase in drug users is fueling the spread of HIV/AIDS in the region as users share needles and perform unprotected sex. It is estimated that 60 -70 percent of newly registered HIV/AIDS cases are a result of using shared needles. The UNODC maintains that there has been a six-fold increase in HIV/AIDS cases since 2000 in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

The illicit drug trade has created adverse social effects in Central Asia. The number of registered drug users in the region has increased dramatically since 1990 as the drug trafficking has made drugs more widely available, which in turn lowers the cost, promoting abuse. In 1996 there were about 40, 000 registered drug users, while in 2006 there were over 100, 000 registered users. This rapid increase in drug users is fueling the spread of HIV/AIDS in the region as users share needles and perform unprotected sex. It is estimated that 60 -70 percent of newly registered HIV/AIDS cases are a result of using shared needles. The UNODC maintains that there has been a six-fold increase in HIV/AIDS cases since 2000 in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

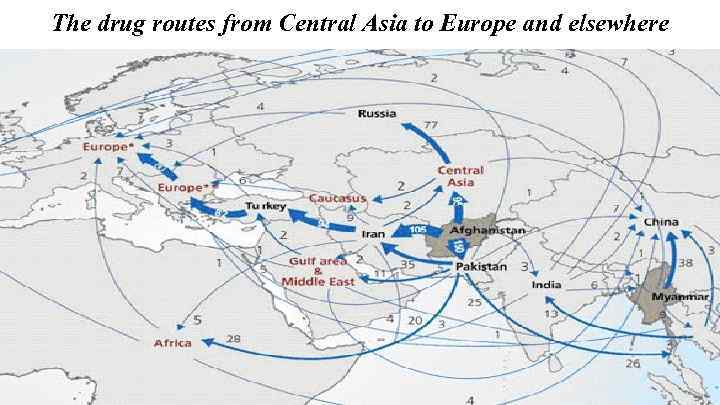

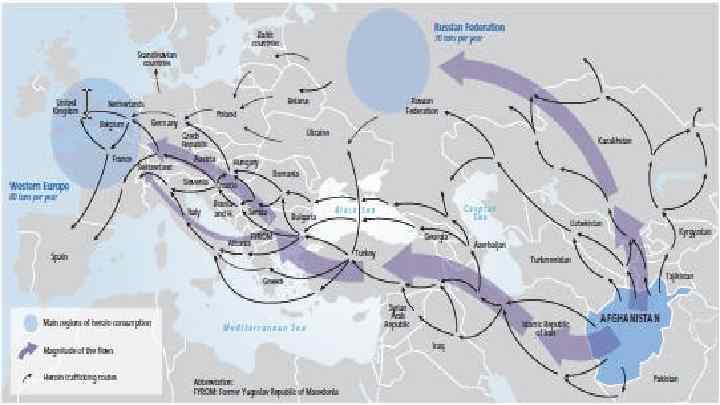

The drug routes from Central Asia to Europe and elsewhere

The drug routes from Central Asia to Europe and elsewhere

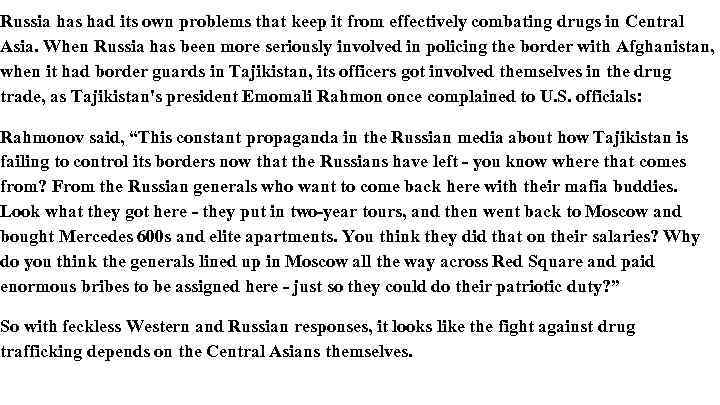

Russia has had its own problems that keep it from effectively combating drugs in Central Asia. When Russia has been more seriously involved in policing the border with Afghanistan, when it had border guards in Tajikistan, its officers got involved themselves in the drug trade, as Tajikistan's president Emomali Rahmon once complained to U. S. officials: Rahmonov said, “This constant propaganda in the Russian media about how Tajikistan is failing to control its borders now that the Russians have left - you know where that comes from? From the Russian generals who want to come back here with their mafia buddies. Look what they got here - they put in two-year tours, and then went back to Moscow and bought Mercedes 600 s and elite apartments. You think they did that on their salaries? Why do you think the generals lined up in Moscow all the way across Red Square and paid enormous bribes to be assigned here - just so they could do their patriotic duty? ” So with feckless Western and Russian responses, it looks like the fight against drug trafficking depends on the Central Asians themselves.

Russia has had its own problems that keep it from effectively combating drugs in Central Asia. When Russia has been more seriously involved in policing the border with Afghanistan, when it had border guards in Tajikistan, its officers got involved themselves in the drug trade, as Tajikistan's president Emomali Rahmon once complained to U. S. officials: Rahmonov said, “This constant propaganda in the Russian media about how Tajikistan is failing to control its borders now that the Russians have left - you know where that comes from? From the Russian generals who want to come back here with their mafia buddies. Look what they got here - they put in two-year tours, and then went back to Moscow and bought Mercedes 600 s and elite apartments. You think they did that on their salaries? Why do you think the generals lined up in Moscow all the way across Red Square and paid enormous bribes to be assigned here - just so they could do their patriotic duty? ” So with feckless Western and Russian responses, it looks like the fight against drug trafficking depends on the Central Asians themselves.

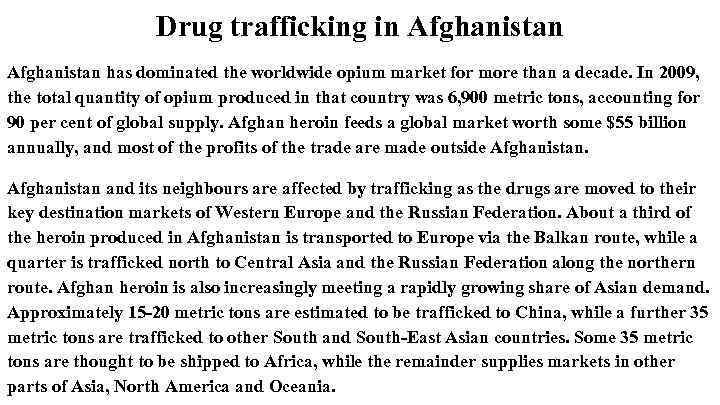

Drug trafficking in Afghanistan has dominated the worldwide opium market for more than a decade. In 2009, the total quantity of opium produced in that country was 6, 900 metric tons, accounting for 90 per cent of global supply. Afghan heroin feeds a global market worth some $55 billion annually, and most of the profits of the trade are made outside Afghanistan and its neighbours are affected by trafficking as the drugs are moved to their key destination markets of Western Europe and the Russian Federation. About a third of the heroin produced in Afghanistan is transported to Europe via the Balkan route, while a quarter is trafficked north to Central Asia and the Russian Federation along the northern route. Afghan heroin is also increasingly meeting a rapidly growing share of Asian demand. Approximately 15 -20 metric tons are estimated to be trafficked to China, while a further 35 metric tons are trafficked to other South and South-East Asian countries. Some 35 metric tons are thought to be shipped to Africa, while the remainder supplies markets in other parts of Asia, North America and Oceania.

Drug trafficking in Afghanistan has dominated the worldwide opium market for more than a decade. In 2009, the total quantity of opium produced in that country was 6, 900 metric tons, accounting for 90 per cent of global supply. Afghan heroin feeds a global market worth some $55 billion annually, and most of the profits of the trade are made outside Afghanistan and its neighbours are affected by trafficking as the drugs are moved to their key destination markets of Western Europe and the Russian Federation. About a third of the heroin produced in Afghanistan is transported to Europe via the Balkan route, while a quarter is trafficked north to Central Asia and the Russian Federation along the northern route. Afghan heroin is also increasingly meeting a rapidly growing share of Asian demand. Approximately 15 -20 metric tons are estimated to be trafficked to China, while a further 35 metric tons are trafficked to other South and South-East Asian countries. Some 35 metric tons are thought to be shipped to Africa, while the remainder supplies markets in other parts of Asia, North America and Oceania.

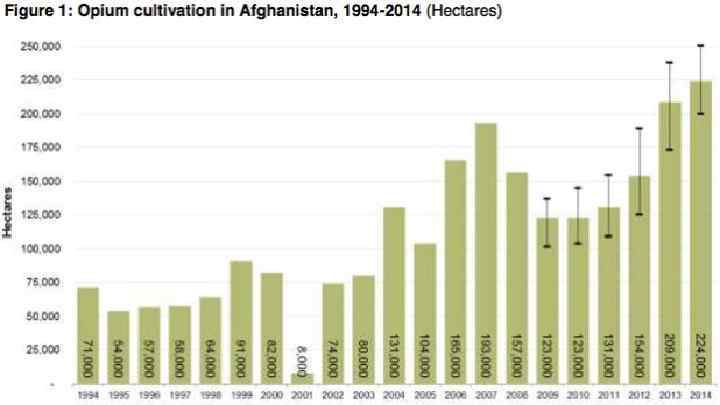

Background - During the Taliban regime The Taliban in collaboration with the United Nations– had imposed a successful ban on poppy cultivation and heroin production in Afghanistan in 2000. However, the US government and media have constantly been accusing the defunct “hard-line Islamic regime”, without even acknowledging the Taliban contribution to eradication of poppy cultivation. Due to the Taliban regime’s efforts opium production declined by more than 90 per cent in 2001. In fact the surge in opium cultivation production coincided with the onslaught of the US-led military operation and the downfall of the Taliban regime. From October through December 2001, farmers started to replant poppy on an extensive basis. The success of Afghanistan’s 2000 drug eradication program under the Taliban had been acknowledged at the October 2001 session of the UN General Assembly (which took place barely a few days after the beginning of the 2001 bombing raids). No other UNODC member country was able to implement a comparable program.

Background - During the Taliban regime The Taliban in collaboration with the United Nations– had imposed a successful ban on poppy cultivation and heroin production in Afghanistan in 2000. However, the US government and media have constantly been accusing the defunct “hard-line Islamic regime”, without even acknowledging the Taliban contribution to eradication of poppy cultivation. Due to the Taliban regime’s efforts opium production declined by more than 90 per cent in 2001. In fact the surge in opium cultivation production coincided with the onslaught of the US-led military operation and the downfall of the Taliban regime. From October through December 2001, farmers started to replant poppy on an extensive basis. The success of Afghanistan’s 2000 drug eradication program under the Taliban had been acknowledged at the October 2001 session of the UN General Assembly (which took place barely a few days after the beginning of the 2001 bombing raids). No other UNODC member country was able to implement a comparable program.

In the wake of the US invasion, shift in rhetoric. UNODC is now acting as if the 2000 opium ban had never happened. In fact, both Washington and the UNODC now claim that the objective of the Taliban in 2000 was not really “drug eradication” but a devious scheme to trigger “an artificial shortfall in supply”, which would drive up World prices of heroin.

In the wake of the US invasion, shift in rhetoric. UNODC is now acting as if the 2000 opium ban had never happened. In fact, both Washington and the UNODC now claim that the objective of the Taliban in 2000 was not really “drug eradication” but a devious scheme to trigger “an artificial shortfall in supply”, which would drive up World prices of heroin.

Drug trafficking in Afghanistan and foreign involvement Since the US led invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001, the Golden Crescent opium trade has soared. According to the US media, this lucrative contraband is protected by Osama, the Taliban, not to mention, of course, the regional warlords, in defiance of the “international community”. In response to the post-Taliban surge in opium production, the Bush administration has boosted its counter terrorism activities, while allocating substantial amounts of public money to the Drug Enforcement Administration’s West Asia initiative, dubbed “Operation Containment. ” In the wake of the 2001 US bombing of Afghanistan, the British government of Tony Blair was entrusted by the G-8 Group of leading industrial nations to carry out a drug eradication program, which would, in theory, allow Afghan farmers to switch out of poppy cultivation into alternative crops. The British were working out of Kabul in close liaison with the US DEA’s “Operation Containment”.

Drug trafficking in Afghanistan and foreign involvement Since the US led invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001, the Golden Crescent opium trade has soared. According to the US media, this lucrative contraband is protected by Osama, the Taliban, not to mention, of course, the regional warlords, in defiance of the “international community”. In response to the post-Taliban surge in opium production, the Bush administration has boosted its counter terrorism activities, while allocating substantial amounts of public money to the Drug Enforcement Administration’s West Asia initiative, dubbed “Operation Containment. ” In the wake of the 2001 US bombing of Afghanistan, the British government of Tony Blair was entrusted by the G-8 Group of leading industrial nations to carry out a drug eradication program, which would, in theory, allow Afghan farmers to switch out of poppy cultivation into alternative crops. The British were working out of Kabul in close liaison with the US DEA’s “Operation Containment”.

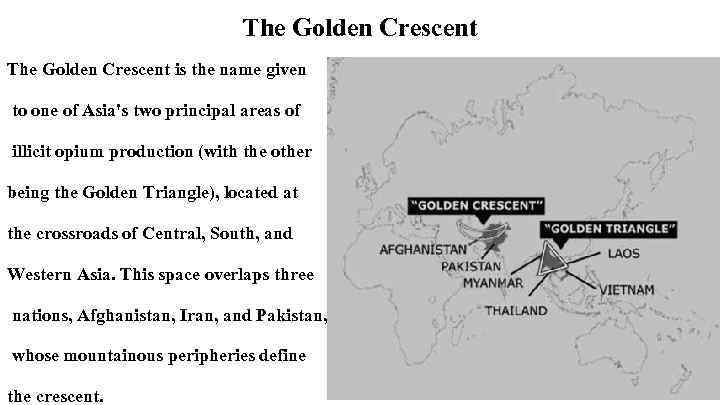

The Golden Crescent is the name given to one of Asia's two principal areas of illicit opium production (with the other being the Golden Triangle), located at the crossroads of Central, South, and Western Asia. This space overlaps three nations, Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan, whose mountainous peripheries define the crescent.

The Golden Crescent is the name given to one of Asia's two principal areas of illicit opium production (with the other being the Golden Triangle), located at the crossroads of Central, South, and Western Asia. This space overlaps three nations, Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan, whose mountainous peripheries define the crescent.

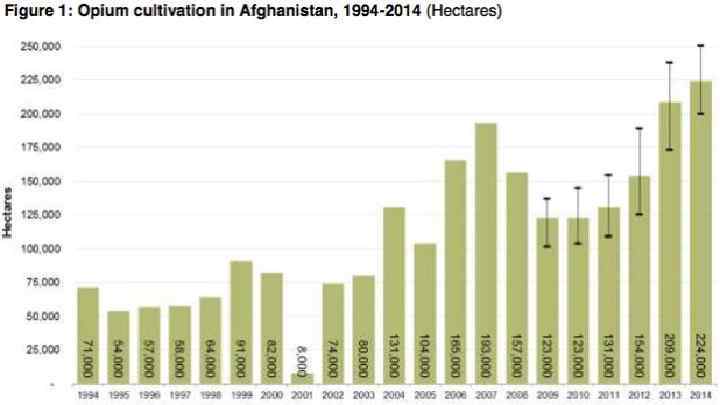

The UK sponsored crop eradication program is an obvious smokescreen. Since October 2001, opium poppy cultivation has skyrocketed. The presence of occupation forces in Afghanistan did not result in the eradication of poppy cultivation. Quite the opposite. The Taliban prohibition had indeed caused “the beginning of a heroin shortage in Europe by the end of 2001″, as acknowledged by the UNODC. Heroin is a multibillion dollar business supported by powerful interests, which requires a steady and secure commodity flow. One of the “hidden” objectives of the war was precisely to restore the CIA sponsored drug trade to its historical levels and exert direct control over the drug routes. Immediately following the October 2001 invasion, opium markets were restored. Opium prices spiraled. By early 2002, the opium price (in dollars/kg) was almost 10 times higher than in 2000. In 2001, under the Taliban opiate production stood at 185 tons, increasing to 3400 tons in 2002 under the US sponsored puppet regime of President Hamid Karzai.

The UK sponsored crop eradication program is an obvious smokescreen. Since October 2001, opium poppy cultivation has skyrocketed. The presence of occupation forces in Afghanistan did not result in the eradication of poppy cultivation. Quite the opposite. The Taliban prohibition had indeed caused “the beginning of a heroin shortage in Europe by the end of 2001″, as acknowledged by the UNODC. Heroin is a multibillion dollar business supported by powerful interests, which requires a steady and secure commodity flow. One of the “hidden” objectives of the war was precisely to restore the CIA sponsored drug trade to its historical levels and exert direct control over the drug routes. Immediately following the October 2001 invasion, opium markets were restored. Opium prices spiraled. By early 2002, the opium price (in dollars/kg) was almost 10 times higher than in 2000. In 2001, under the Taliban opiate production stood at 185 tons, increasing to 3400 tons in 2002 under the US sponsored puppet regime of President Hamid Karzai.

It is worth recalling the history of the Golden Crescent drug trade, which is intimately related to the CIA’s covert operations in the region since the onslaught of the Soviet-Afghan war and its aftermath. Prior to the Soviet-Afghan war (1979 -1989), opium production in Afghanistan and Pakistan was directed to small regional markets. There was no local production of heroin. The Afghan narcotics economy was a carefully designed project of the CIA, supported by US foreign policy. As revealed in the Iran-Contra and Bank of Commerce and Credit International (BCCI) scandals, CIA covert operations in support of the Afghan Mujahideen had been funded through the laundering of drug money. “Dirty money” was recycled –through a number of banking institutions (in the Middle East) as well as through anonymous CIA shell companies–, into “covert money, ” used to finance various insurgent groups during the Soviet-Afghan war, and its aftermath.

It is worth recalling the history of the Golden Crescent drug trade, which is intimately related to the CIA’s covert operations in the region since the onslaught of the Soviet-Afghan war and its aftermath. Prior to the Soviet-Afghan war (1979 -1989), opium production in Afghanistan and Pakistan was directed to small regional markets. There was no local production of heroin. The Afghan narcotics economy was a carefully designed project of the CIA, supported by US foreign policy. As revealed in the Iran-Contra and Bank of Commerce and Credit International (BCCI) scandals, CIA covert operations in support of the Afghan Mujahideen had been funded through the laundering of drug money. “Dirty money” was recycled –through a number of banking institutions (in the Middle East) as well as through anonymous CIA shell companies–, into “covert money, ” used to finance various insurgent groups during the Soviet-Afghan war, and its aftermath.

Washington’s Hidden Agenda: Restore the Drug Trade The revenues generated from the CIA sponsored Afghan drug trade are sizeable. The Afghan trade in opiates constitutes a large share of the worldwide annual turnover of narcotics, which was estimated by the United Nations to be of the order of $400 -500 billion. The IMF estimated global money laundering to be between 590 billion and 1. 5 trillion dollars a year, representing 2 -5 percent of global GDP. A large share of global money laundering as estimated by the IMF is linked to the trade in narcotics. According to the British newspaper The Independent (29 February 2004), drug trafficking constitutes “the third biggest global commodity in cash terms after oil and the arms trade. Afghanistan produced 6, 400 tons of opium in 2014, about 90 percent of the world's supply.

Washington’s Hidden Agenda: Restore the Drug Trade The revenues generated from the CIA sponsored Afghan drug trade are sizeable. The Afghan trade in opiates constitutes a large share of the worldwide annual turnover of narcotics, which was estimated by the United Nations to be of the order of $400 -500 billion. The IMF estimated global money laundering to be between 590 billion and 1. 5 trillion dollars a year, representing 2 -5 percent of global GDP. A large share of global money laundering as estimated by the IMF is linked to the trade in narcotics. According to the British newspaper The Independent (29 February 2004), drug trafficking constitutes “the third biggest global commodity in cash terms after oil and the arms trade. Afghanistan produced 6, 400 tons of opium in 2014, about 90 percent of the world's supply.

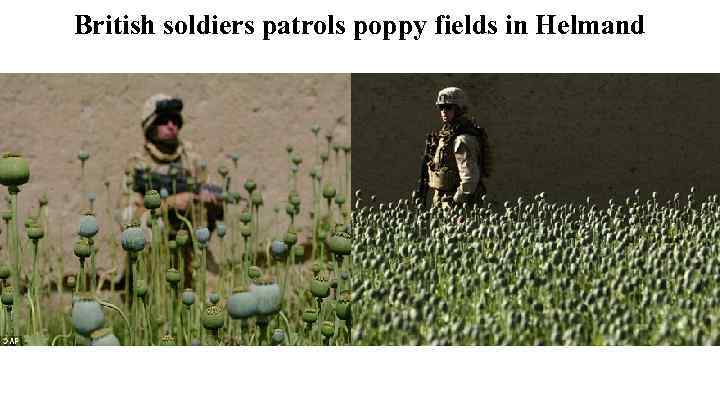

British soldiers patrols poppy fields in Helmand

British soldiers patrols poppy fields in Helmand

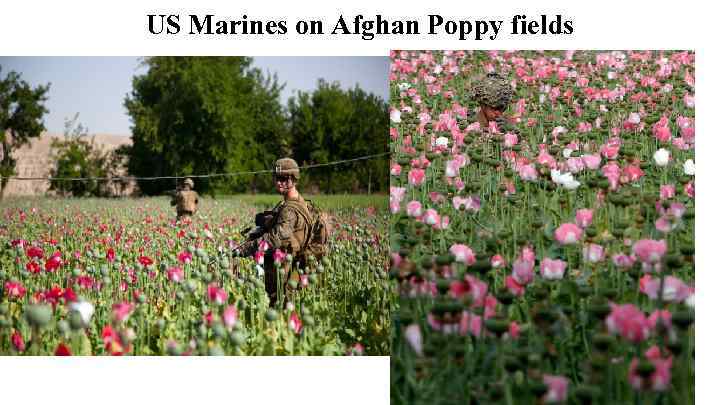

US Marines on Afghan Poppy fields

US Marines on Afghan Poppy fields

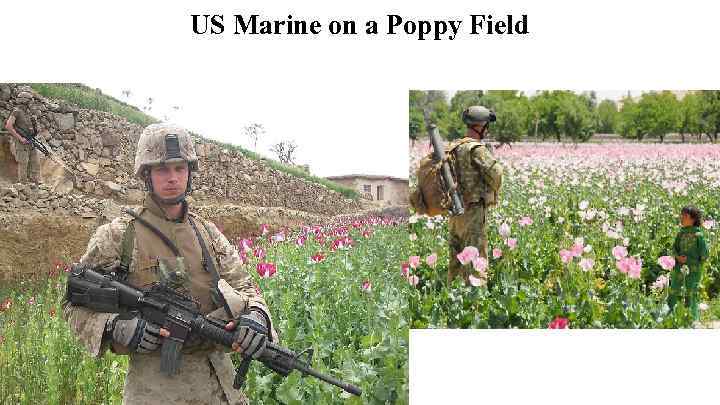

US Marine on a Poppy Field

US Marine on a Poppy Field

The Making of a Narco State After 14 years of war, the US and the West have not defeated the Taliban, but they have managed to create a nation ruled by drug lords. "Narco corruption went to the top of the Afghan government, " wrote a U. S. official. "President Karzai was playing us like a fiddle. " While highlighting Karzai’s patriotic struggle against the Taliban, the media fails to mention that Karzai collaborated with the Taliban. He had also been on the payroll of a major US oil company, UNOCAL. In fact, since the mid 1990 s, Hamid Karzai had acted as a consultant and lobbyist for UNOCAL in negotiations with the Taliban.

The Making of a Narco State After 14 years of war, the US and the West have not defeated the Taliban, but they have managed to create a nation ruled by drug lords. "Narco corruption went to the top of the Afghan government, " wrote a U. S. official. "President Karzai was playing us like a fiddle. " While highlighting Karzai’s patriotic struggle against the Taliban, the media fails to mention that Karzai collaborated with the Taliban. He had also been on the payroll of a major US oil company, UNOCAL. In fact, since the mid 1990 s, Hamid Karzai had acted as a consultant and lobbyist for UNOCAL in negotiations with the Taliban.

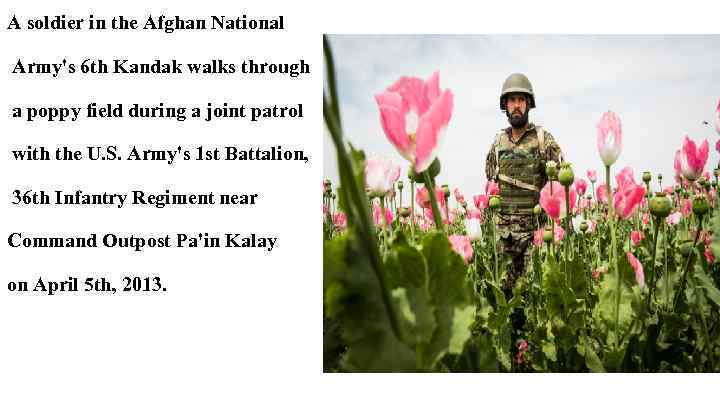

A soldier in the Afghan National Army's 6 th Kandak walks through a poppy field during a joint patrol with the U. S. Army's 1 st Battalion, 36 th Infantry Regiment near Command Outpost Pa'in Kalay on April 5 th, 2013.

A soldier in the Afghan National Army's 6 th Kandak walks through a poppy field during a joint patrol with the U. S. Army's 1 st Battalion, 36 th Infantry Regiment near Command Outpost Pa'in Kalay on April 5 th, 2013.

Criminalization of US Foreign Policy US foreign policy supports the workings of a thriving criminal economy in which the demarcation between organized capital and organized crime has become increasingly blurred. The heroin business is not “filling the coffers of the Taliban” as claimed by US government and the international community: quite the opposite! The proceeds of this illegal trade are the source of wealth formation, largely reaped by powerful business/criminal interests within the Western countries. These interests are sustained by US foreign policy. Decision-making in the US State Department, the CIA and the Pentagon is instrumental in supporting this highly profitable multibillion dollar trade, third in commodity value after oil and the arms trade. The Afghan drug economy is “protected”. But by whom?

Criminalization of US Foreign Policy US foreign policy supports the workings of a thriving criminal economy in which the demarcation between organized capital and organized crime has become increasingly blurred. The heroin business is not “filling the coffers of the Taliban” as claimed by US government and the international community: quite the opposite! The proceeds of this illegal trade are the source of wealth formation, largely reaped by powerful business/criminal interests within the Western countries. These interests are sustained by US foreign policy. Decision-making in the US State Department, the CIA and the Pentagon is instrumental in supporting this highly profitable multibillion dollar trade, third in commodity value after oil and the arms trade. The Afghan drug economy is “protected”. But by whom?