8236d2505860d2ff13f5a1c690f377ef.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 82

Diversity Algorithms for Worrisome Software and Networks (DAWSON) James Just, Nathan Li Global Info. Tek, Inc. Karl Levitt, Jeff Rowe, Tufan Demir UC Davis R. Sekar Consultant (SUNY Stony Brook) 12 July 2005

Diversity Algorithms for Worrisome Software and Networks (DAWSON) James Just, Nathan Li Global Info. Tek, Inc. Karl Levitt, Jeff Rowe, Tufan Demir UC Davis R. Sekar Consultant (SUNY Stony Brook) 12 July 2005

Overview • Project overview • Layer 1 Diversity: Prevent exploitation • Layer 2 Diversity: Accept exploitation, but prevent the successful execution of injected code • Transforms implemented and ongoing Key: randomization • Analytic results • Testing status and results • Demo tonight

Overview • Project overview • Layer 1 Diversity: Prevent exploitation • Layer 2 Diversity: Accept exploitation, but prevent the successful execution of injected code • Transforms implemented and ongoing Key: randomization • Analytic results • Testing status and results • Demo tonight

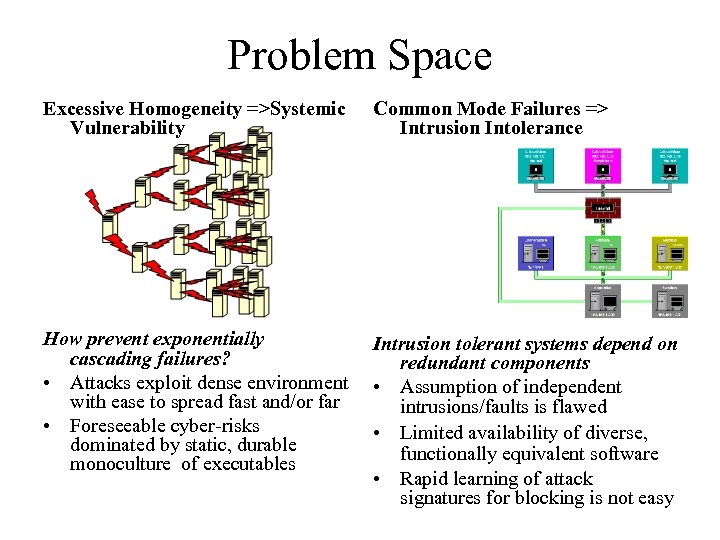

Problem Space Excessive Homogeneity =>Systemic Vulnerability Common Mode Failures => Intrusion Intolerance How prevent exponentially cascading failures? • Attacks exploit dense environment with ease to spread fast and/or far • Foreseeable cyber-risks dominated by static, durable monoculture of executables Intrusion tolerant systems depend on redundant components • Assumption of independent intrusions/faults is flawed • Limited availability of diverse, functionally equivalent software • Rapid learning of attack signatures for blocking is not easy

Problem Space Excessive Homogeneity =>Systemic Vulnerability Common Mode Failures => Intrusion Intolerance How prevent exponentially cascading failures? • Attacks exploit dense environment with ease to spread fast and/or far • Foreseeable cyber-risks dominated by static, durable monoculture of executables Intrusion tolerant systems depend on redundant components • Assumption of independent intrusions/faults is flawed • Limited availability of diverse, functionally equivalent software • Rapid learning of attack signatures for blocking is not easy

DAWSON Goal and Approach • Break exploitation of memory errors in monocultures through run-time injection of synthetic diversity • Deliver defense in depth for Windows executables that break exploits, break payloads, prevent bypass, etc. – – Preserve functionality of executables Transform absolute memory addresses, names, order, etc Randomize relative memory addresses Annotation files (e. g. , Vulcan-ized)can facilitate some advanced transforms without source code – Pseudo-random numbers produce unique transformations on each restart of application • DAWSON objective: Beat program metric by 10 X for large fraction of exploit space – 100 functional equivalents with no more than 3 susceptible to same exploit as baseline code for non-data attacks – Low overhead transforms (<10% runtime performance)

DAWSON Goal and Approach • Break exploitation of memory errors in monocultures through run-time injection of synthetic diversity • Deliver defense in depth for Windows executables that break exploits, break payloads, prevent bypass, etc. – – Preserve functionality of executables Transform absolute memory addresses, names, order, etc Randomize relative memory addresses Annotation files (e. g. , Vulcan-ized)can facilitate some advanced transforms without source code – Pseudo-random numbers produce unique transformations on each restart of application • DAWSON objective: Beat program metric by 10 X for large fraction of exploit space – 100 functional equivalents with no more than 3 susceptible to same exploit as baseline code for non-data attacks – Low overhead transforms (<10% runtime performance)

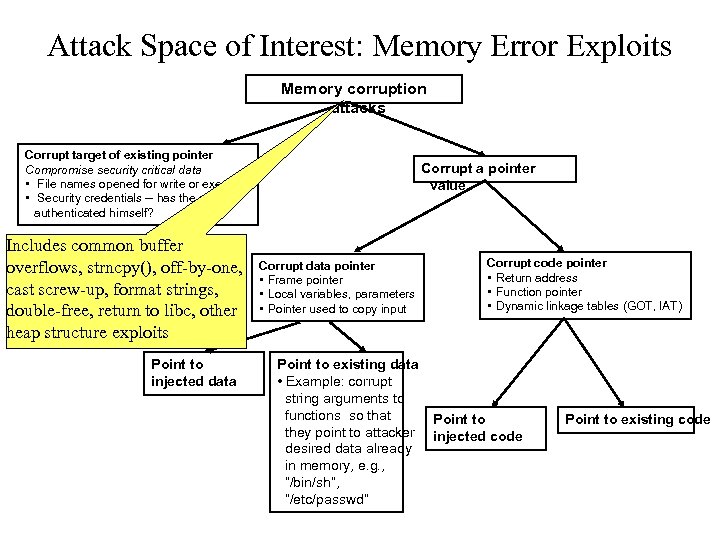

Attack Space of Interest: Memory Error Exploits Memory corruption attacks Corrupt target of existing pointer Compromise security critical data • File names opened for write or execute • Security credentials -- has the user authenticated himself? Includes common buffer overflows, strncpy(), off-by-one, cast screw-up, format strings, double-free, return to libc, other heap structure exploits Point to injected data Corrupt a pointer value Corrupt data pointer • Frame pointer • Local variables, parameters • Pointer used to copy input Point to existing data • Example: corrupt string arguments to functions so that they point to attacker desired data already in memory, e. g. , “/bin/sh”, “/etc/passwd” Corrupt code pointer • Return address • Function pointer • Dynamic linkage tables (GOT, IAT) Point to injected code Point to existing code

Attack Space of Interest: Memory Error Exploits Memory corruption attacks Corrupt target of existing pointer Compromise security critical data • File names opened for write or execute • Security credentials -- has the user authenticated himself? Includes common buffer overflows, strncpy(), off-by-one, cast screw-up, format strings, double-free, return to libc, other heap structure exploits Point to injected data Corrupt a pointer value Corrupt data pointer • Frame pointer • Local variables, parameters • Pointer used to copy input Point to existing data • Example: corrupt string arguments to functions so that they point to attacker desired data already in memory, e. g. , “/bin/sh”, “/etc/passwd” Corrupt code pointer • Return address • Function pointer • Dynamic linkage tables (GOT, IAT) Point to injected code Point to existing code

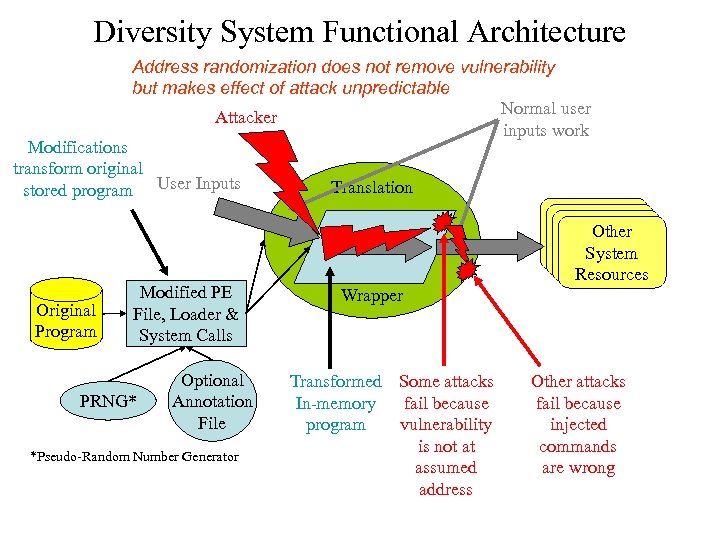

Diversity System Functional Architecture Address randomization does not remove vulnerability but makes effect of attack unpredictable Normal user Attacker inputs work Modifications transform original stored program User Inputs Original Program Modified PE File, Loader & System Calls PRNG* Optional Annotation File *Pseudo-Random Number Generator Translation Other System Resources Wrapper Transformed Some attacks In-memory fail because program vulnerability is not at assumed address Other attacks fail because injected commands are wrong

Diversity System Functional Architecture Address randomization does not remove vulnerability but makes effect of attack unpredictable Normal user Attacker inputs work Modifications transform original stored program User Inputs Original Program Modified PE File, Loader & System Calls PRNG* Optional Annotation File *Pseudo-Random Number Generator Translation Other System Resources Wrapper Transformed Some attacks In-memory fail because program vulnerability is not at assumed address Other attacks fail because injected commands are wrong

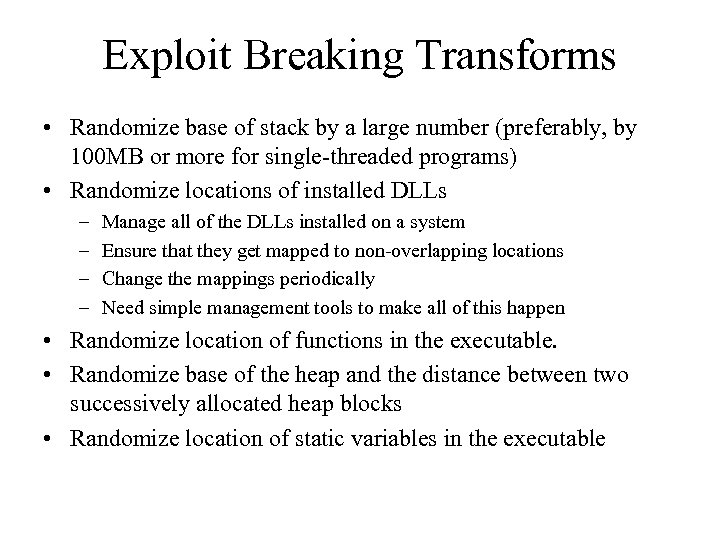

Exploit Breaking Transforms • Randomize base of stack by a large number (preferably, by 100 MB or more for single-threaded programs) • Randomize locations of installed DLLs – – Manage all of the DLLs installed on a system Ensure that they get mapped to non-overlapping locations Change the mappings periodically Need simple management tools to make all of this happen • Randomize location of functions in the executable. • Randomize base of the heap and the distance between two successively allocated heap blocks • Randomize location of static variables in the executable

Exploit Breaking Transforms • Randomize base of stack by a large number (preferably, by 100 MB or more for single-threaded programs) • Randomize locations of installed DLLs – – Manage all of the DLLs installed on a system Ensure that they get mapped to non-overlapping locations Change the mappings periodically Need simple management tools to make all of this happen • Randomize location of functions in the executable. • Randomize base of the heap and the distance between two successively allocated heap blocks • Randomize location of static variables in the executable

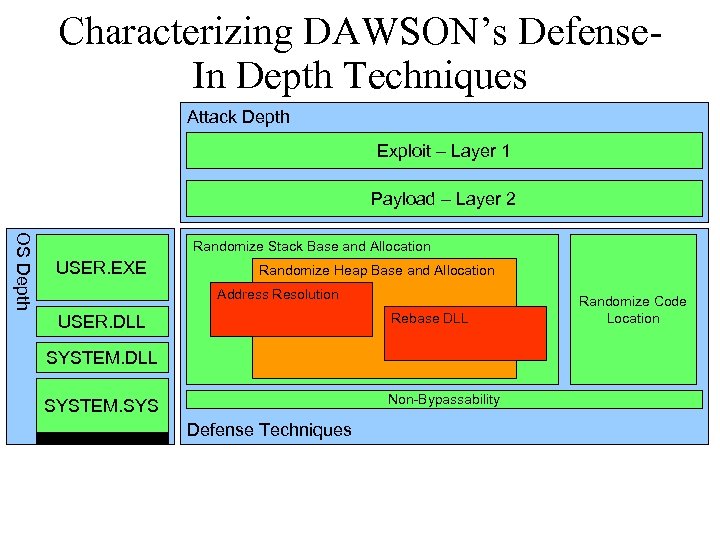

Characterizing DAWSON’s Defense. In Depth Techniques Attack Depth Exploit – Layer 1 Payload – Layer 2 OS Depth Randomize Stack Base and Allocation USER. EXE Randomize Heap Base and Allocation Address Resolution Rebase DLL USER. DLL SYSTEM. DLL Non-Bypassability SYSTEM. SYS Defense Techniques Randomize Code Location

Characterizing DAWSON’s Defense. In Depth Techniques Attack Depth Exploit – Layer 1 Payload – Layer 2 OS Depth Randomize Stack Base and Allocation USER. EXE Randomize Heap Base and Allocation Address Resolution Rebase DLL USER. DLL SYSTEM. DLL Non-Bypassability SYSTEM. SYS Defense Techniques Randomize Code Location

Evaluation Plan • Analytic study determines impact and size of implemented randomizations • Live exploit testing using: – Real applications with known vulnerabilities and exploits – Synthetic applications with new vulnerabilities and exploits (non-stack smashing attacks) – Emulab network testbed – Varied randomization settings to explore effectiveness • Red Team for sophisticated unknown attacks (e. g. , derandomizing) and bypass testing

Evaluation Plan • Analytic study determines impact and size of implemented randomizations • Live exploit testing using: – Real applications with known vulnerabilities and exploits – Synthetic applications with new vulnerabilities and exploits (non-stack smashing attacks) – Emulab network testbed – Varied randomization settings to explore effectiveness • Red Team for sophisticated unknown attacks (e. g. , derandomizing) and bypass testing

Status (Interim Products) • Integrated automated transforms – – Randomization of most DLL locations Randomized stack base address Randomized heap address and frames Automated permutation of the Import Address Table in PE files – Automated replacement of DLL names and functions with random strings in PE files • Analysis of exploit effort to break randomization • Synthetic application with advanced memory error vulnerabilities and associated exploits • Automated testing configuration for Emulab • Native Windows (MFC, . Net) PE File Editor

Status (Interim Products) • Integrated automated transforms – – Randomization of most DLL locations Randomized stack base address Randomized heap address and frames Automated permutation of the Import Address Table in PE files – Automated replacement of DLL names and functions with random strings in PE files • Analysis of exploit effort to break randomization • Synthetic application with advanced memory error vulnerabilities and associated exploits • Automated testing configuration for Emulab • Native Windows (MFC, . Net) PE File Editor

Status (In-Process) • • • Kernel 32 and ntdll relocation – not automated yet PEB obfuscation SEH monitoring Reordering of binary code blocks and insertion of dead code blocks Local variable location modification – not quite automated yet Asymmetric transformation of function parameters using dummy functions. Fail-crash & detection mechanism (to defeat brute force trial and error) Memory protection to defeat scanning attacks Evaluating non-bypassable mechanisms – Balzer wrapper mechanism – UC Davis investigating option from another project • Red Team testing

Status (In-Process) • • • Kernel 32 and ntdll relocation – not automated yet PEB obfuscation SEH monitoring Reordering of binary code blocks and insertion of dead code blocks Local variable location modification – not quite automated yet Asymmetric transformation of function parameters using dummy functions. Fail-crash & detection mechanism (to defeat brute force trial and error) Memory protection to defeat scanning attacks Evaluating non-bypassable mechanisms – Balzer wrapper mechanism – UC Davis investigating option from another project • Red Team testing

Remaining Risks and Mitigations • Most problems have been solved since last meeting • Remaining risks – Randomizing ntdll and kernel 32 – Randomizing base of executables without source – Bypassability – Derandomizing attacks – There exists undocumented Windows tables with DLL location information that we are unaware of

Remaining Risks and Mitigations • Most problems have been solved since last meeting • Remaining risks – Randomizing ntdll and kernel 32 – Randomizing base of executables without source – Bypassability – Derandomizing attacks – There exists undocumented Windows tables with DLL location information that we are unaware of

Transition • Intermediate products available for use by other SRS contractors • Integrate with follow-on projects/products • If successful: – Package for military users – Possible GITI “commercial” product – Possible open source “toolkit” approach – Transition to Microsoft or other software vendors – Some expressions of VC interest • Standard research publications

Transition • Intermediate products available for use by other SRS contractors • Integrate with follow-on projects/products • If successful: – Package for military users – Possible GITI “commercial” product – Possible open source “toolkit” approach – Transition to Microsoft or other software vendors – Some expressions of VC interest • Standard research publications

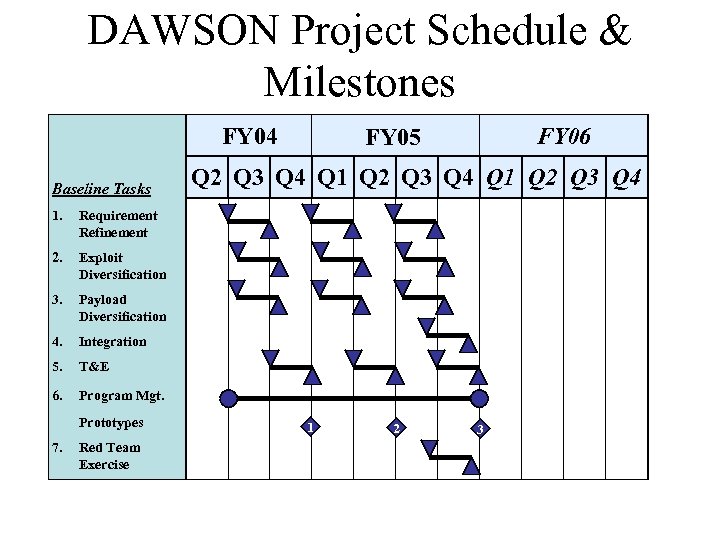

DAWSON Project Schedule & Milestones FY 04 Baseline Tasks 1. Exploit Diversification 3. Payload Diversification 4. Integration 5. T&E 6. Q 2 Q 3 Q 4 Q 1 Q 2 Q 3 Q 4 Requirement Refinement 2. FY 06 FY 05 Program Mgt. Prototypes 7. Red Team Exercise 1 2 3

DAWSON Project Schedule & Milestones FY 04 Baseline Tasks 1. Exploit Diversification 3. Payload Diversification 4. Integration 5. T&E 6. Q 2 Q 3 Q 4 Q 1 Q 2 Q 3 Q 4 Requirement Refinement 2. FY 06 FY 05 Program Mgt. Prototypes 7. Red Team Exercise 1 2 3

Layer 1: Address Randomization to Break Exploits • Dynamic Run Time Randomization • User Mode Function Hooking • Randomizations - Stack randomization - Heap randomization - DLL Base Randomization

Layer 1: Address Randomization to Break Exploits • Dynamic Run Time Randomization • User Mode Function Hooking • Randomizations - Stack randomization - Heap randomization - DLL Base Randomization

Stack Randomization • Two levels of stack randomization are applied – Stack base randomization through hooking stack space function – Stack frame randomization by inserting fake Thread_START_ROUTINE

Stack Randomization • Two levels of stack randomization are applied – Stack base randomization through hooking stack space function – Stack frame randomization by inserting fake Thread_START_ROUTINE

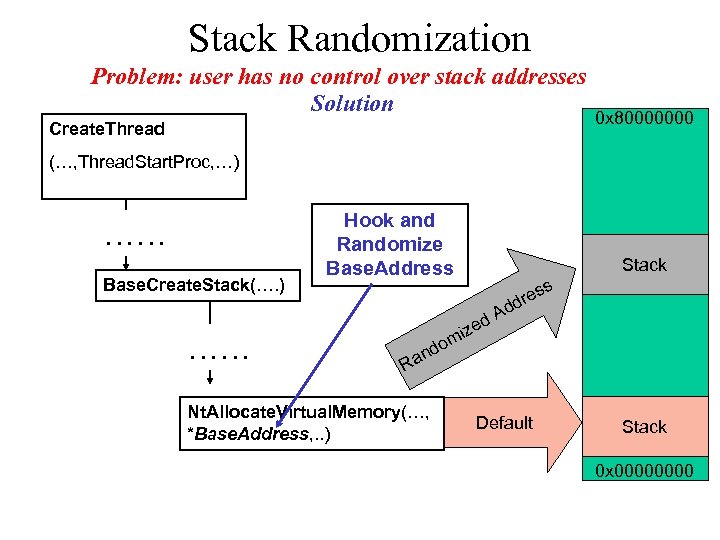

Stack Randomization Problem: user has no control over stack addresses Solution Create. Thread 0 x 80000000 (…, Thread. Start. Proc, …) …… Base. Create. Stack(…. ) …… Hook and Randomize Base. Address Stack s d ize m s dre d A o d an R Nt. Allocate. Virtual. Memory(…, *Base. Address, . . ) Default Stack 0 x 0000

Stack Randomization Problem: user has no control over stack addresses Solution Create. Thread 0 x 80000000 (…, Thread. Start. Proc, …) …… Base. Create. Stack(…. ) …… Hook and Randomize Base. Address Stack s d ize m s dre d A o d an R Nt. Allocate. Virtual. Memory(…, *Base. Address, . . ) Default Stack 0 x 0000

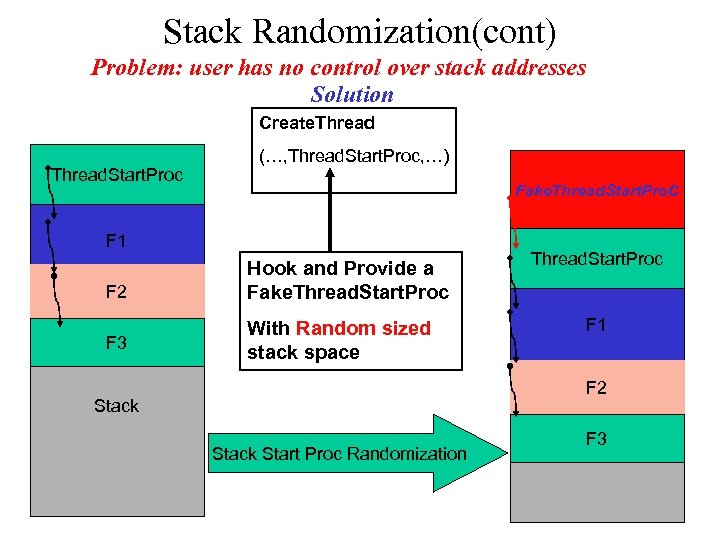

Stack Randomization(cont) Problem: user has no control over stack addresses Solution Create. Thread. Start. Proc (…, Thread. Start. Proc, …) Fake. Thread. Start. Proc F 1 F 2 F 3 Hook and Provide a Fake. Thread. Start. Proc With Random sized stack space Thread. Start. Proc F 1 Stack F 2 Stack Start Proc Randomization F 3

Stack Randomization(cont) Problem: user has no control over stack addresses Solution Create. Thread. Start. Proc (…, Thread. Start. Proc, …) Fake. Thread. Start. Proc F 1 F 2 F 3 Hook and Provide a Fake. Thread. Start. Proc With Random sized stack space Thread. Start. Proc F 1 Stack F 2 Stack Start Proc Randomization F 3

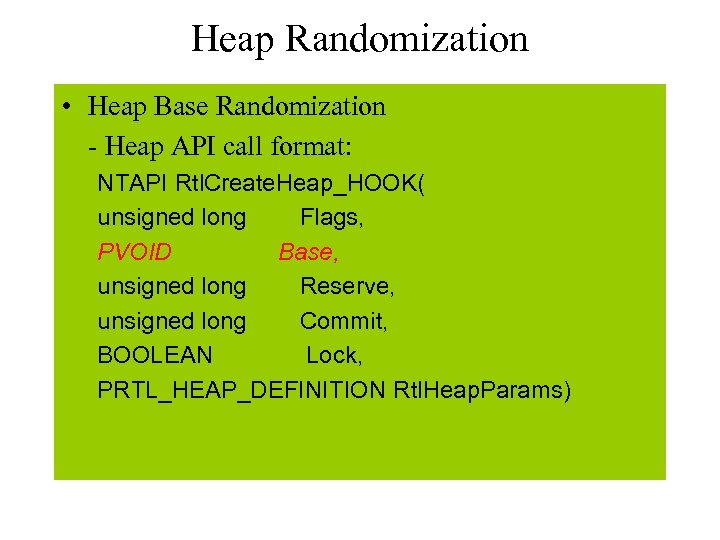

Heap Randomization • Heap Base Randomization - Heap API call format: NTAPI Rtl. Create. Heap_HOOK( unsigned long Flags, PVOID Base, unsigned long Reserve, unsigned long Commit, BOOLEAN Lock, PRTL_HEAP_DEFINITION Rtl. Heap. Params)

Heap Randomization • Heap Base Randomization - Heap API call format: NTAPI Rtl. Create. Heap_HOOK( unsigned long Flags, PVOID Base, unsigned long Reserve, unsigned long Commit, BOOLEAN Lock, PRTL_HEAP_DEFINITION Rtl. Heap. Params)

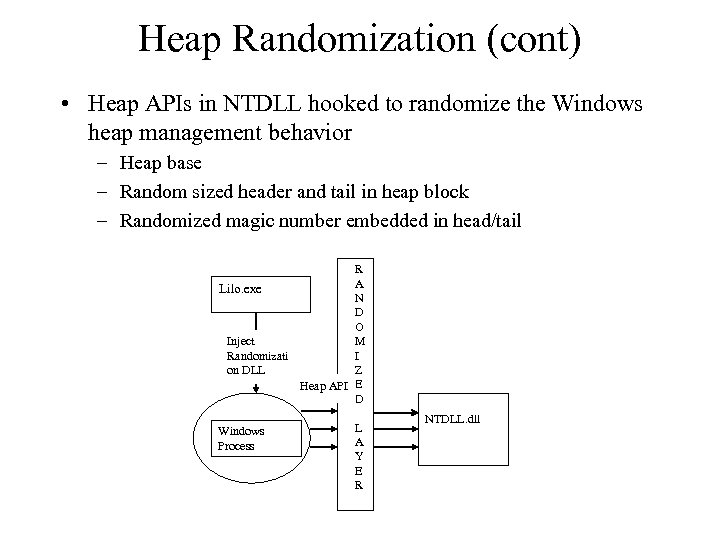

Heap Randomization (cont) • Heap APIs in NTDLL hooked to randomize the Windows heap management behavior – Heap base – Random sized header and tail in heap block – Randomized magic number embedded in head/tail R A Lilo. exe N D O M Inject I Randomizati Z on DLL Heap API E D Windows Process L A Y E R NTDLL. dll

Heap Randomization (cont) • Heap APIs in NTDLL hooked to randomize the Windows heap management behavior – Heap base – Random sized header and tail in heap block – Randomized magic number embedded in head/tail R A Lilo. exe N D O M Inject I Randomizati Z on DLL Heap API E D Windows Process L A Y E R NTDLL. dll

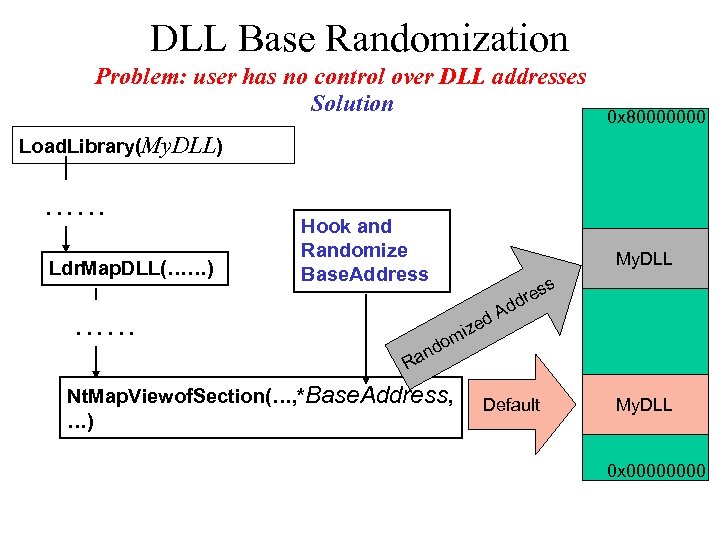

DLL Base Randomization Problem: user has no control over DLL addresses Solution 0 x 80000000 Load. Library(My. DLL) …… Ldr. Map. DLL(……) Hook and Randomize Base. Address …… d an My. DLL d ize s res dd A om R Nt. Map. Viewof. Section(…, *Base. Address, …) Default My. DLL 0 x 0000

DLL Base Randomization Problem: user has no control over DLL addresses Solution 0 x 80000000 Load. Library(My. DLL) …… Ldr. Map. DLL(……) Hook and Randomize Base. Address …… d an My. DLL d ize s res dd A om R Nt. Map. Viewof. Section(…, *Base. Address, …) Default My. DLL 0 x 0000

DLL Base Randomization • DLLs aligned on 64 k boundaries - working to change this through “junk code” insertion • Does not work for ntdll and kernel 32 rebase from user mode hooking - kernel driver/system call hooking approach is being explored. - Another technique used in Layer 2 defense

DLL Base Randomization • DLLs aligned on 64 k boundaries - working to change this through “junk code” insertion • Does not work for ntdll and kernel 32 rebase from user mode hooking - kernel driver/system call hooking approach is being explored. - Another technique used in Layer 2 defense

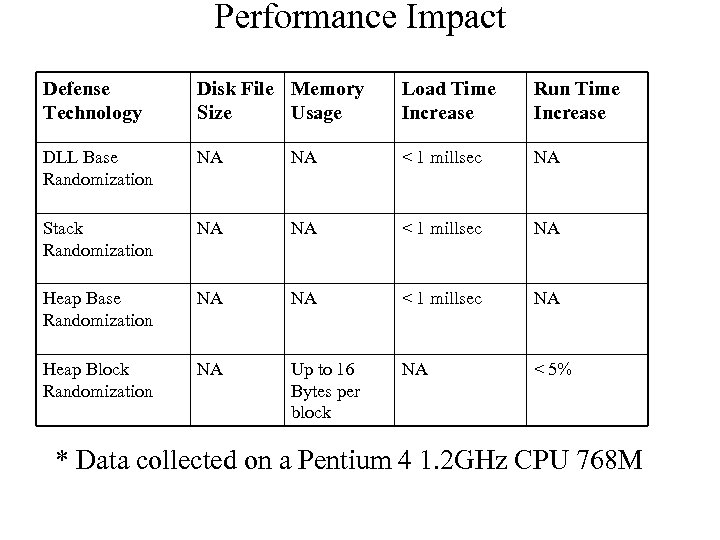

Performance Impact Defense Technology Disk File Memory Size Usage Load Time Increase Run Time Increase DLL Base Randomization NA NA < 1 millsec NA Stack Randomization NA NA < 1 millsec NA Heap Base Randomization NA NA < 1 millsec NA Heap Block Randomization NA Up to 16 Bytes per block NA < 5% * Data collected on a Pentium 4 1. 2 GHz CPU 768 M

Performance Impact Defense Technology Disk File Memory Size Usage Load Time Increase Run Time Increase DLL Base Randomization NA NA < 1 millsec NA Stack Randomization NA NA < 1 millsec NA Heap Base Randomization NA NA < 1 millsec NA Heap Block Randomization NA Up to 16 Bytes per block NA < 5% * Data collected on a Pentium 4 1. 2 GHz CPU 768 M

Layer 2 - Diversity to Break Malicious Payloads • Windows executables typically call API functions for any significant task • All API functions are provided in DLLs – Load address of API functions is not known until the program loads – Load address of API functions varies from host to host • Major goal of Windows exploits is to locate the addresses of critical DLL functions • Our Approach: Introduce synthetic diversity into the Windows DLL system, preventing injected code from locating and executing any system calls.

Layer 2 - Diversity to Break Malicious Payloads • Windows executables typically call API functions for any significant task • All API functions are provided in DLLs – Load address of API functions is not known until the program loads – Load address of API functions varies from host to host • Major goal of Windows exploits is to locate the addresses of critical DLL functions • Our Approach: Introduce synthetic diversity into the Windows DLL system, preventing injected code from locating and executing any system calls.

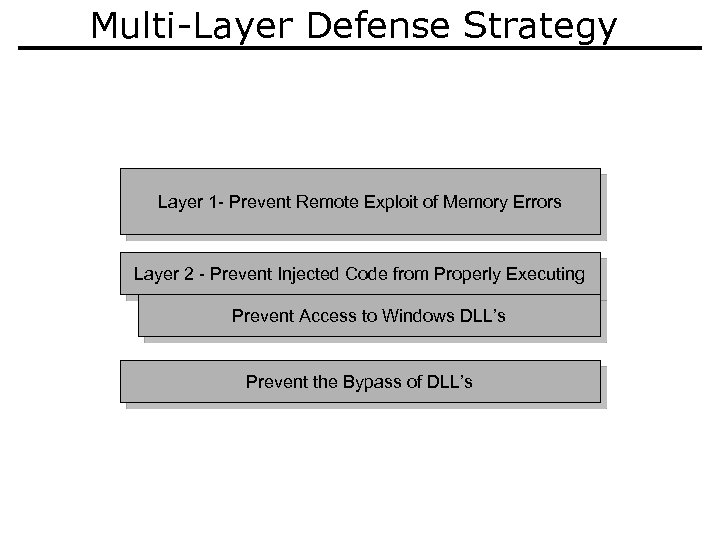

Multi-Layer Defense Strategy Layer 1 - Prevent Remote Exploit of Memory Errors Layer 2 - Prevent Injected Code from Properly Executing Prevent Access to Windows DLL’s Prevent the Bypass of DLL’s

Multi-Layer Defense Strategy Layer 1 - Prevent Remote Exploit of Memory Errors Layer 2 - Prevent Injected Code from Properly Executing Prevent Access to Windows DLL’s Prevent the Bypass of DLL’s

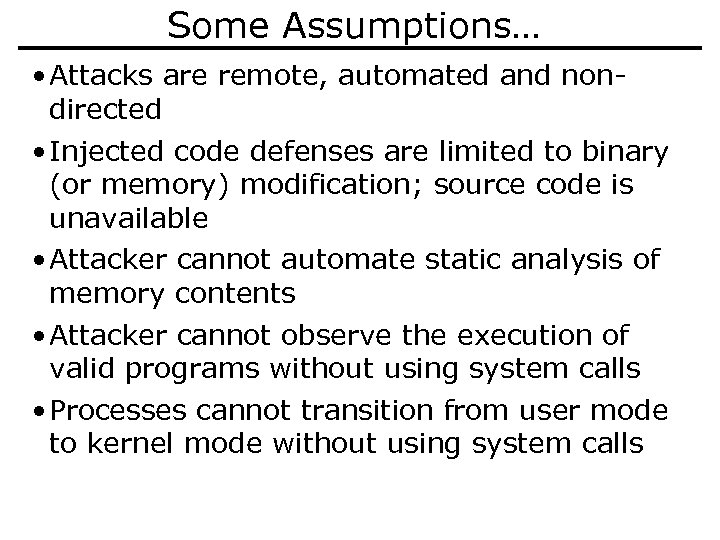

Some Assumptions… • Attacks are remote, automated and nondirected • Injected code defenses are limited to binary (or memory) modification; source code is unavailable • Attacker cannot automate static analysis of memory contents • Attacker cannot observe the execution of valid programs without using system calls • Processes cannot transition from user mode to kernel mode without using system calls

Some Assumptions… • Attacks are remote, automated and nondirected • Injected code defenses are limited to binary (or memory) modification; source code is unavailable • Attacker cannot automate static analysis of memory contents • Attacker cannot observe the execution of valid programs without using system calls • Processes cannot transition from user mode to kernel mode without using system calls

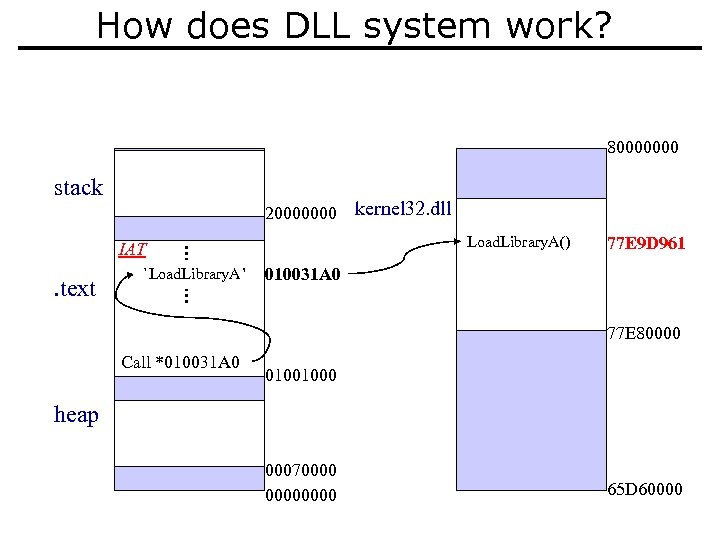

How does DLL system work? 80000000 stack 20000000 . text IAT `Load. Library. A’ 77 E 9 D 961 kernel 32. dll Load. Library. A() 77 E 9 D 961 010031 A 0 77 E 80000 Call *010031 A 0 01001000 heap 00070000 65 D 60000

How does DLL system work? 80000000 stack 20000000 . text IAT `Load. Library. A’ 77 E 9 D 961 kernel 32. dll Load. Library. A() 77 E 9 D 961 010031 A 0 77 E 80000 Call *010031 A 0 01001000 heap 00070000 65 D 60000

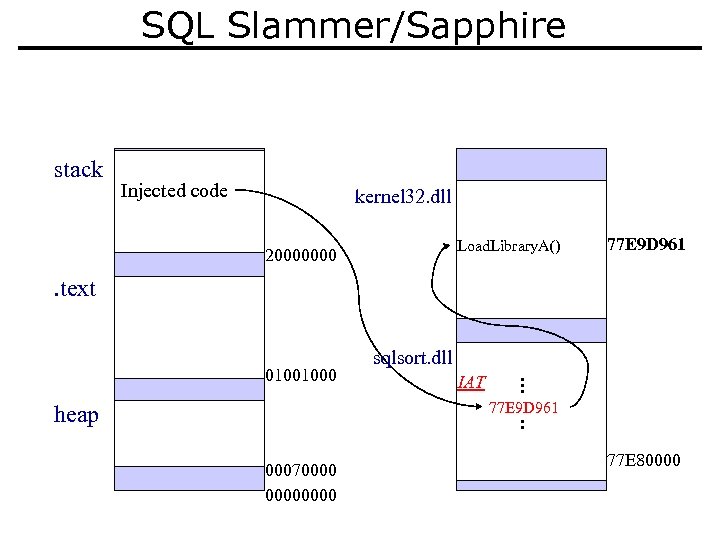

SQL Slammer/Sapphire stack Injected code kernel 32. dll Load. Library. A() 20000000 77 E 9 D 961 . text 01001000 sqlsort. dll IAT 77 E 9 D 961 heap 00070000 77 E 80000

SQL Slammer/Sapphire stack Injected code kernel 32. dll Load. Library. A() 20000000 77 E 9 D 961 . text 01001000 sqlsort. dll IAT 77 E 9 D 961 heap 00070000 77 E 80000

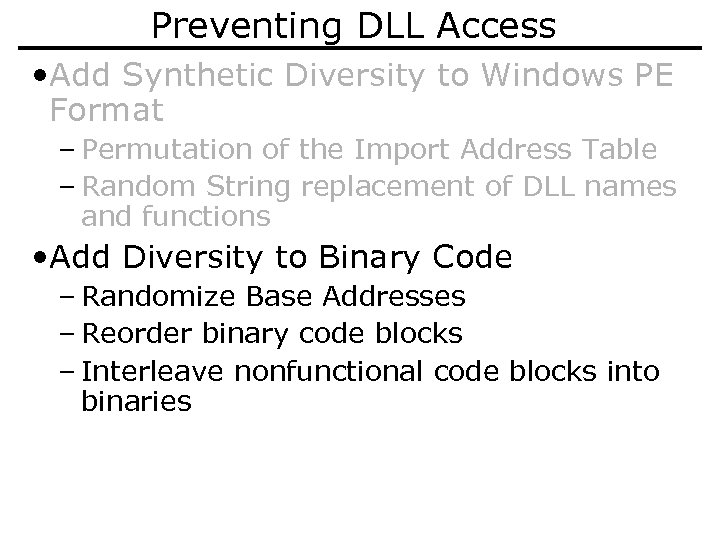

Preventing DLL Access • Add Synthetic Diversity to Windows PE Format – Permutation of the Import Address Table – Random String replacement of DLL names and functions • Add Diversity to Binary Code – Randomize Base Addresses – Reorder binary code blocks – Interleave nonfunctional code blocks into binaries

Preventing DLL Access • Add Synthetic Diversity to Windows PE Format – Permutation of the Import Address Table – Random String replacement of DLL names and functions • Add Diversity to Binary Code – Randomize Base Addresses – Reorder binary code blocks – Interleave nonfunctional code blocks into binaries

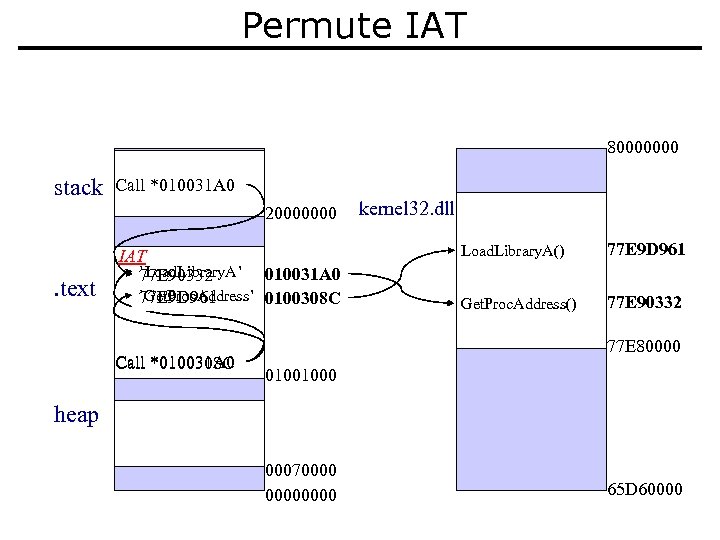

Permute IAT 80000000 stack Call *010031 A 0 20000000 . text IAT `Load. Library. A’ 010031 A 0 77 E 90332 `Get. Proc. Address’ 0100308 C 77 E 9 D 961 Call *010031 A 0 *0100308 C kernel 32. dll Load. Library. A() 77 E 9 D 961 Get. Proc. Address() 77 E 90332 77 E 80000 01001000 heap 00070000 65 D 60000

Permute IAT 80000000 stack Call *010031 A 0 20000000 . text IAT `Load. Library. A’ 010031 A 0 77 E 90332 `Get. Proc. Address’ 0100308 C 77 E 9 D 961 Call *010031 A 0 *0100308 C kernel 32. dll Load. Library. A() 77 E 9 D 961 Get. Proc. Address() 77 E 90332 77 E 80000 01001000 heap 00070000 65 D 60000

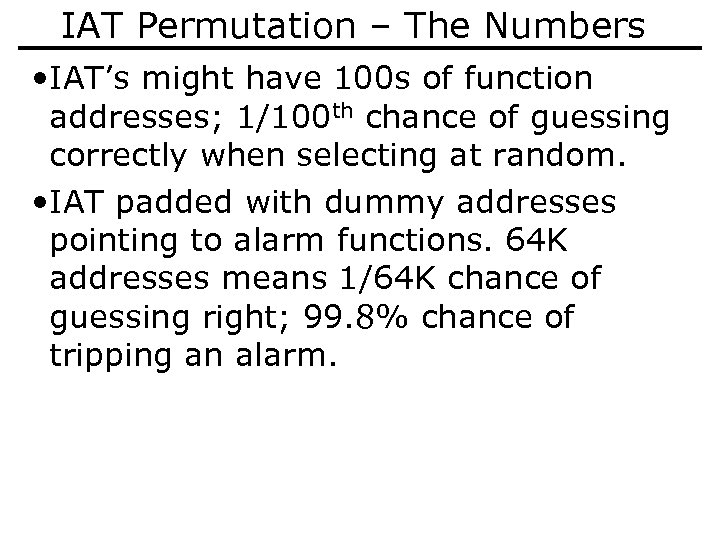

IAT Permutation – The Numbers • IAT’s might have 100 s of function addresses; 1/100 th chance of guessing correctly when selecting at random. • IAT padded with dummy addresses pointing to alarm functions. 64 K addresses means 1/64 K chance of guessing right; 99. 8% chance of tripping an alarm.

IAT Permutation – The Numbers • IAT’s might have 100 s of function addresses; 1/100 th chance of guessing correctly when selecting at random. • IAT padded with dummy addresses pointing to alarm functions. 64 K addresses means 1/64 K chance of guessing right; 99. 8% chance of tripping an alarm.

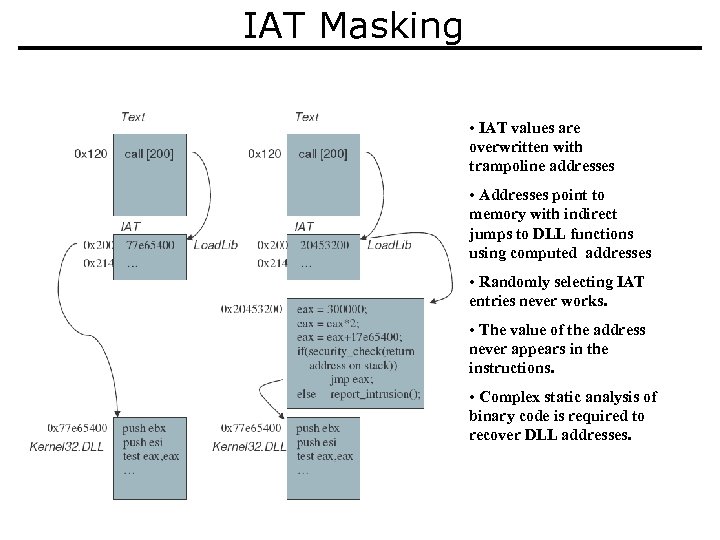

IAT Masking • IAT values are overwritten with trampoline addresses • Addresses point to memory with indirect jumps to DLL functions using computed addresses • Randomly selecting IAT entries never works. • The value of the address never appears in the instructions. • Complex static analysis of binary code is required to recover DLL addresses.

IAT Masking • IAT values are overwritten with trampoline addresses • Addresses point to memory with indirect jumps to DLL functions using computed addresses • Randomly selecting IAT entries never works. • The value of the address never appears in the instructions. • Complex static analysis of binary code is required to recover DLL addresses.

Preventing DLL Access • Add Synthetic Diversity to Windows PE Format – Permutation of the Import Address Table – Random String replacement of DLL names and functions • Add Diversity to Binary Code – Randomize Base Addresses – Reorder binary code blocks – Interleave nonfunctional code blocks into binaries

Preventing DLL Access • Add Synthetic Diversity to Windows PE Format – Permutation of the Import Address Table – Random String replacement of DLL names and functions • Add Diversity to Binary Code – Randomize Base Addresses – Reorder binary code blocks – Interleave nonfunctional code blocks into binaries

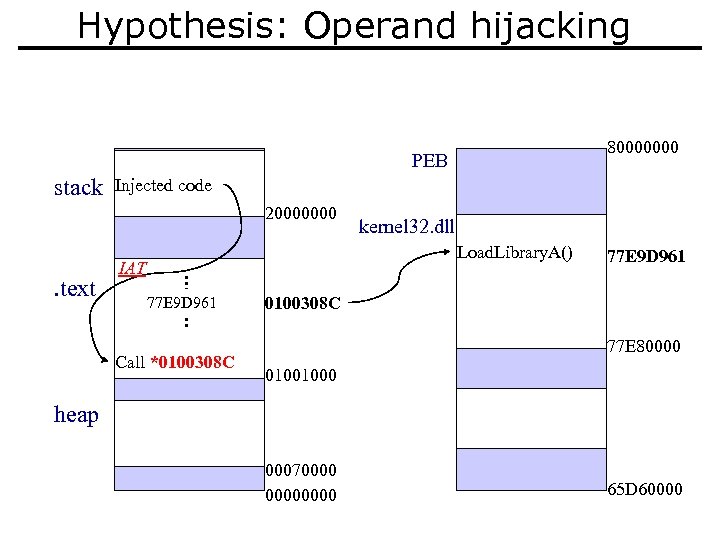

Hypothesis: Operand hijacking 80000000 PEB stack Injected code 20000000 . text kernel 32. dll Load. Library. A() IAT 77 E 9 D 961 Call *0100308 C 77 E 9 D 961 0100308 C 77 E 80000 01001000 heap 00070000 65 D 60000

Hypothesis: Operand hijacking 80000000 PEB stack Injected code 20000000 . text kernel 32. dll Load. Library. A() IAT 77 E 9 D 961 Call *0100308 C 77 E 9 D 961 0100308 C 77 E 80000 01001000 heap 00070000 65 D 60000

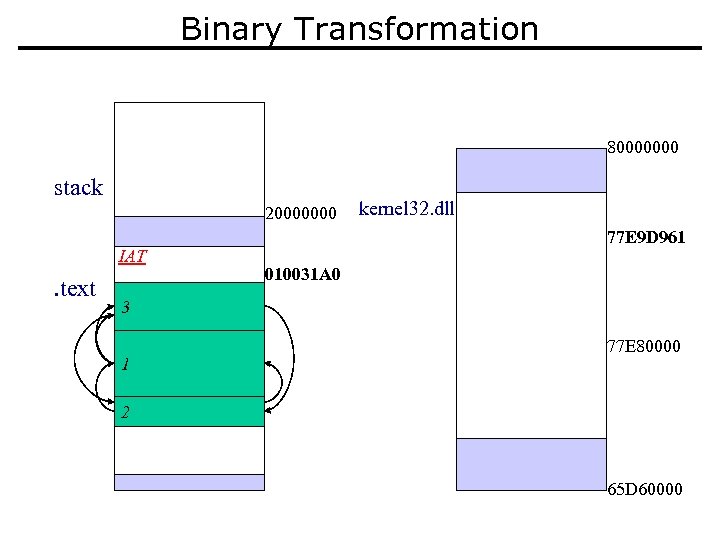

Binary Transformation 80000000 stack 20000000 IAT . text kernel 32. dll 77 E 9 D 961 010031 A 0 3 1 1 2 77 E 80000 3 2 65 D 60000

Binary Transformation 80000000 stack 20000000 IAT . text kernel 32. dll 77 E 9 D 961 010031 A 0 3 1 1 2 77 E 80000 3 2 65 D 60000

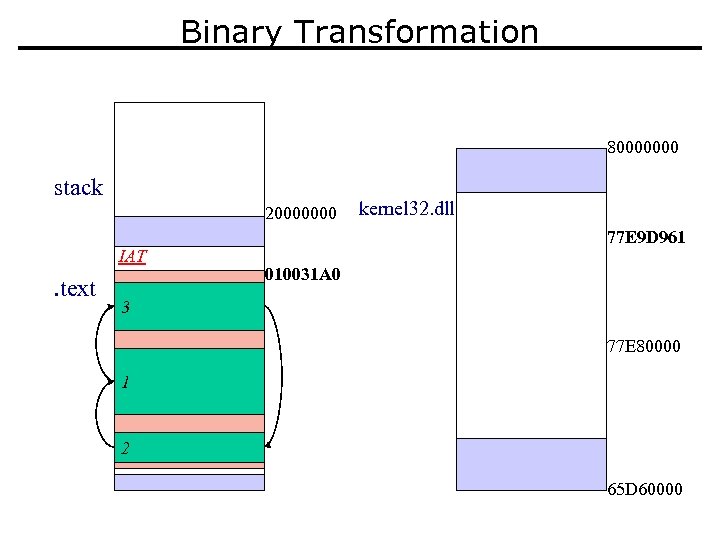

Binary Transformation 80000000 stack 20000000 IAT . text kernel 32. dll 77 E 9 D 961 010031 A 0 3 2 1 77 E 80000 2 65 D 60000

Binary Transformation 80000000 stack 20000000 IAT . text kernel 32. dll 77 E 9 D 961 010031 A 0 3 2 1 77 E 80000 2 65 D 60000

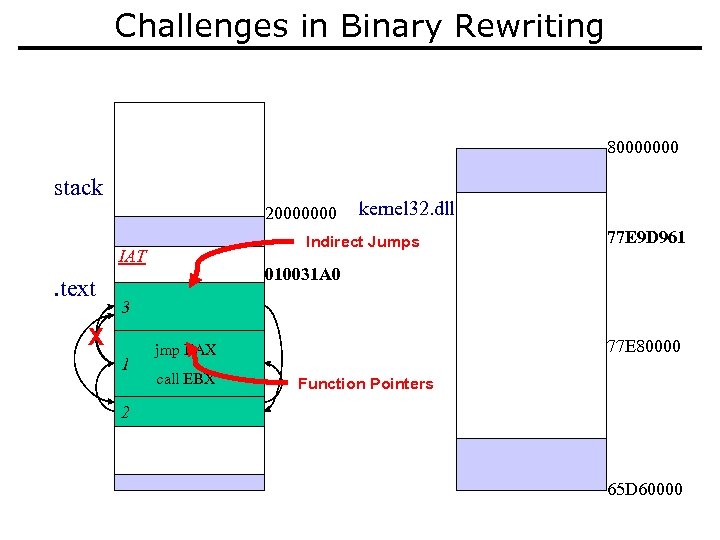

Challenges in Binary Rewriting 80000000 stack 20000000 Indirect Jumps IAT . text X 3 1 1 2 kernel 32. dll 77 E 9 D 961 010031 A 0 JMP EAX Call EBX jmp EAX call EBX 77 E 80000 Function Pointers 3 2 65 D 60000

Challenges in Binary Rewriting 80000000 stack 20000000 Indirect Jumps IAT . text X 3 1 1 2 kernel 32. dll 77 E 9 D 961 010031 A 0 JMP EAX Call EBX jmp EAX call EBX 77 E 80000 Function Pointers 3 2 65 D 60000

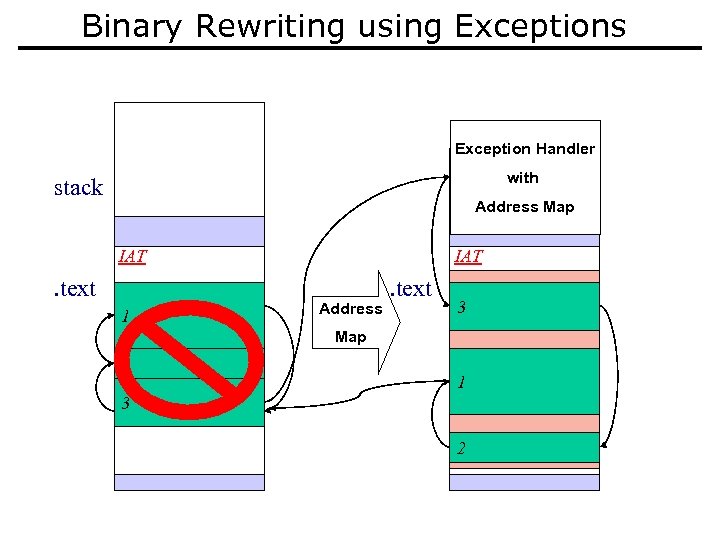

Binary Rewriting using Exceptions Exception Handler with stack Address Map IAT . text 1 IAT Address . text 3 Map 2 2 1 3 2

Binary Rewriting using Exceptions Exception Handler with stack Address Map IAT . text 1 IAT Address . text 3 Map 2 2 1 3 2

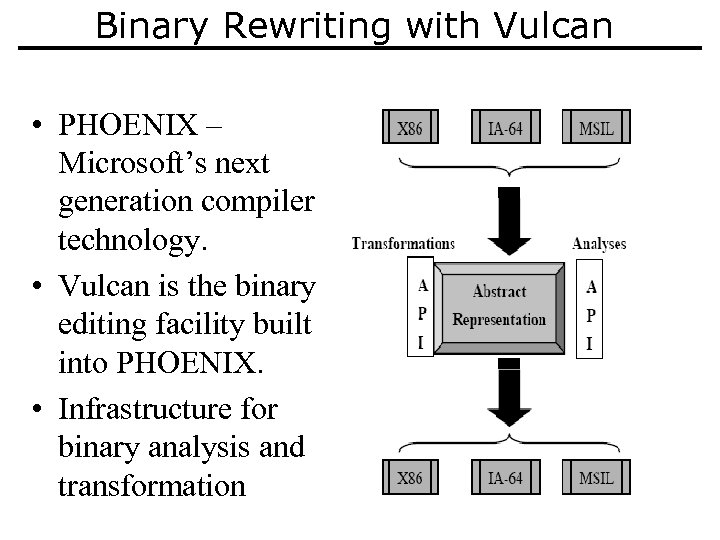

Binary Rewriting with Vulcan • PHOENIX – Microsoft’s next generation compiler technology. • Vulcan is the binary editing facility built into PHOENIX. • Infrastructure for binary analysis and transformation

Binary Rewriting with Vulcan • PHOENIX – Microsoft’s next generation compiler technology. • Vulcan is the binary editing facility built into PHOENIX. • Infrastructure for binary analysis and transformation

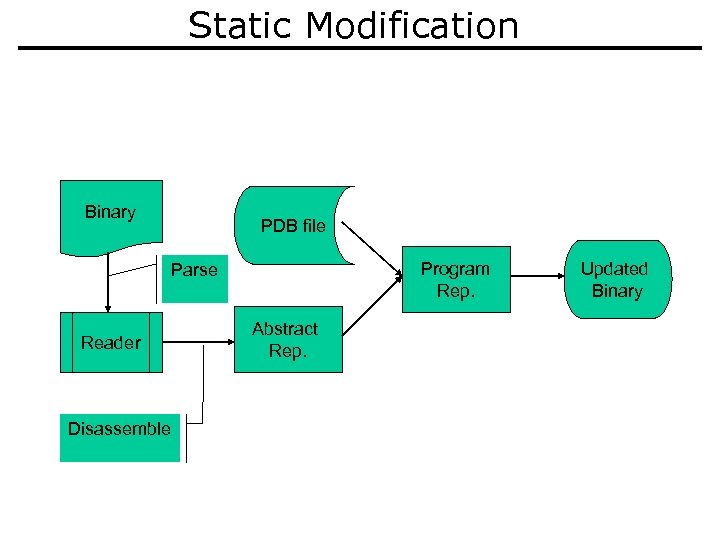

Static Modification Binary PDB file Program Rep. Parse Reader Disassemble Abstract Rep. Updated Binary

Static Modification Binary PDB file Program Rep. Parse Reader Disassemble Abstract Rep. Updated Binary

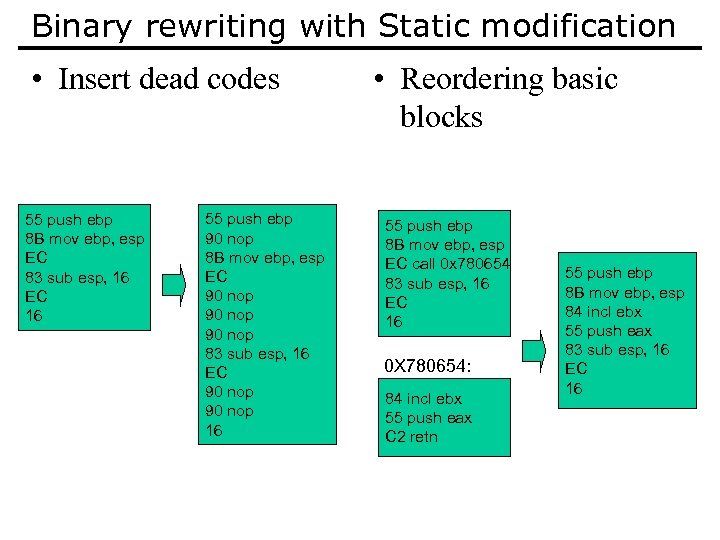

Binary rewriting with Static modification • Insert dead codes 55 push ebp 8 B mov ebp, esp EC 83 sub esp, 16 EC 16 55 push ebp 90 nop 8 B mov ebp, esp EC 90 nop 83 sub esp, 16 EC 90 nop 16 • Reordering basic blocks 55 push ebp 8 B mov ebp, esp EC call 0 x 780654 83 sub esp, 16 EC 16 0 X 780654: 84 incl ebx 55 push eax C 2 retn 55 push ebp 8 B mov ebp, esp 84 incl ebx 55 push eax 83 sub esp, 16 EC 16

Binary rewriting with Static modification • Insert dead codes 55 push ebp 8 B mov ebp, esp EC 83 sub esp, 16 EC 16 55 push ebp 90 nop 8 B mov ebp, esp EC 90 nop 83 sub esp, 16 EC 90 nop 16 • Reordering basic blocks 55 push ebp 8 B mov ebp, esp EC call 0 x 780654 83 sub esp, 16 EC 16 0 X 780654: 84 incl ebx 55 push eax C 2 retn 55 push ebp 8 B mov ebp, esp 84 incl ebx 55 push eax 83 sub esp, 16 EC 16

Binary rewriting with Static modification • Randomize base of static variables – A tag is assigned during compilation process to all Operands of Intermediate Representation – Update the tag if the base of static variables changes – Analyze and Make corresponding changes in the code with the tag information

Binary rewriting with Static modification • Randomize base of static variables – A tag is assigned during compilation process to all Operands of Intermediate Representation – Update the tag if the base of static variables changes – Analyze and Make corresponding changes in the code with the tag information

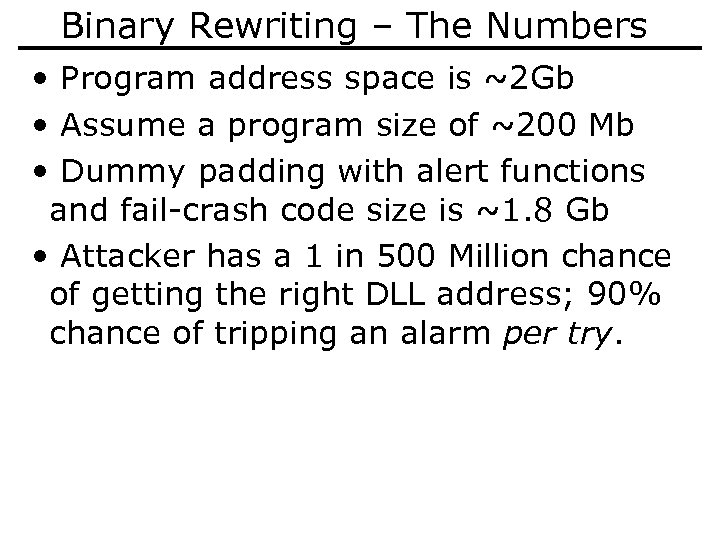

Binary Rewriting – The Numbers • Program address space is ~2 Gb • Assume a program size of ~200 Mb • Dummy padding with alert functions and fail-crash code size is ~1. 8 Gb • Attacker has a 1 in 500 Million chance of getting the right DLL address; 90% chance of tripping an alarm per try.

Binary Rewriting – The Numbers • Program address space is ~2 Gb • Assume a program size of ~200 Mb • Dummy padding with alert functions and fail-crash code size is ~1. 8 Gb • Attacker has a 1 in 500 Million chance of getting the right DLL address; 90% chance of tripping an alarm per try.

Additional Details… Are there other places to find DLL addresses? • Kernel 32. DLL is always loaded in a fixed memory location during boot – Manually modify the Windows boot procedure to rebase kernel 32. dll on boot. • All processes contain a “Process Environment Block” (PEB) data structure with all dll addresses to improve the performance of the loader.

Additional Details… Are there other places to find DLL addresses? • Kernel 32. DLL is always loaded in a fixed memory location during boot – Manually modify the Windows boot procedure to rebase kernel 32. dll on boot. • All processes contain a “Process Environment Block” (PEB) data structure with all dll addresses to improve the performance of the loader.

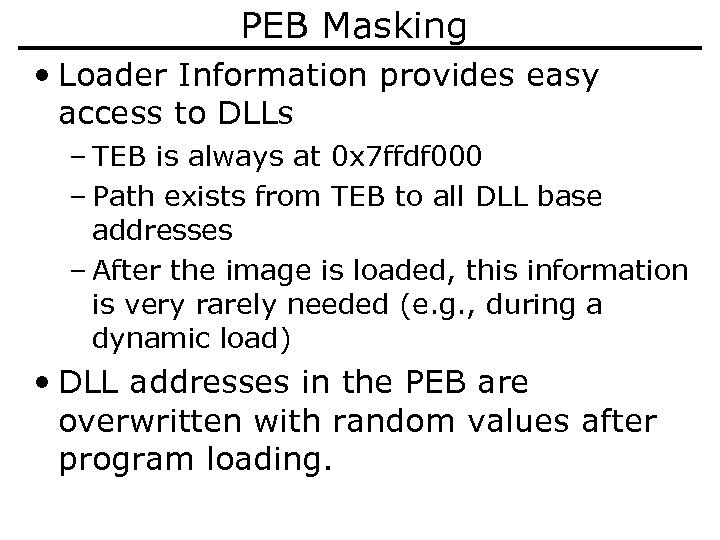

PEB Masking • Loader Information provides easy access to DLLs – TEB is always at 0 x 7 ffdf 000 – Path exists from TEB to all DLL base addresses – After the image is loaded, this information is very rarely needed (e. g. , during a dynamic load) • DLL addresses in the PEB are overwritten with random values after program loading.

PEB Masking • Loader Information provides easy access to DLLs – TEB is always at 0 x 7 ffdf 000 – Path exists from TEB to all DLL base addresses – After the image is loaded, this information is very rarely needed (e. g. , during a dynamic load) • DLL addresses in the PEB are overwritten with random values after program loading.

Preserving Functionality • Include a Wrapper around loader functions • Restores information prior to certain Kernel 32 functions (e. g. , Load. Library) • Re-hides the information prior to passing control back to the (vulnerable) application

Preserving Functionality • Include a Wrapper around loader functions • Restores information prior to certain Kernel 32 functions (e. g. , Load. Library) • Re-hides the information prior to passing control back to the (vulnerable) application

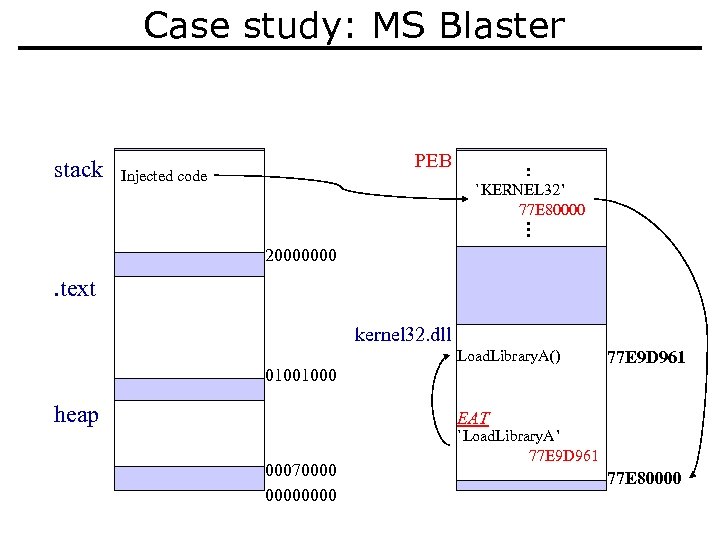

Case study: MS Blaster stack PEB Injected code `KERNEL 32’ 77 E 80000 20000000 . text kernel 32. dll Load. Library. A() 01001000 heap 77 E 9 D 961 EAT 00070000 `Load. Library. A’ 77 E 9 D 961 77 E 80000

Case study: MS Blaster stack PEB Injected code `KERNEL 32’ 77 E 80000 20000000 . text kernel 32. dll Load. Library. A() 01001000 heap 77 E 9 D 961 EAT 00070000 `Load. Library. A’ 77 E 9 D 961 77 E 80000

Preventing DLL Access • Key points – No runtime execution infrastructure – No performance impact upon running programs – Access prevention is policy free

Preventing DLL Access • Key points – No runtime execution infrastructure – No performance impact upon running programs – Access prevention is policy free

Preventing DLL Bypass • Problem: Attacker can provide assembly components that implement some DLL functions making direct low level (undocumented) Windows system calls • Trap System Interrupts for Runtime Checking

Preventing DLL Bypass • Problem: Attacker can provide assembly components that implement some DLL functions making direct low level (undocumented) Windows system calls • Trap System Interrupts for Runtime Checking

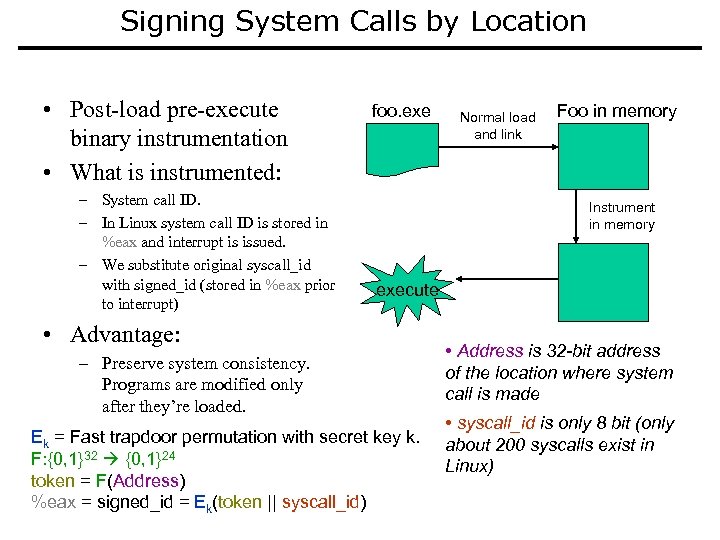

Signing System Calls by Location • Post-load pre-execute binary instrumentation • What is instrumented: – System call ID. – In Linux system call ID is stored in %eax and interrupt is issued. – We substitute original syscall_id with signed_id (stored in %eax prior to interrupt) foo. exe Normal load and link Foo in memory Instrument in memory execute • Advantage: – Preserve system consistency. Programs are modified only after they’re loaded. Ek = Fast trapdoor permutation with secret key k. F: {0, 1}32 {0, 1}24 token = F(Address) %eax = signed_id = Ek(token || syscall_id) • Address is 32 -bit address of the location where system call is made • syscall_id is only 8 bit (only about 200 syscalls exist in Linux)

Signing System Calls by Location • Post-load pre-execute binary instrumentation • What is instrumented: – System call ID. – In Linux system call ID is stored in %eax and interrupt is issued. – We substitute original syscall_id with signed_id (stored in %eax prior to interrupt) foo. exe Normal load and link Foo in memory Instrument in memory execute • Advantage: – Preserve system consistency. Programs are modified only after they’re loaded. Ek = Fast trapdoor permutation with secret key k. F: {0, 1}32 {0, 1}24 token = F(Address) %eax = signed_id = Ek(token || syscall_id) • Address is 32 -bit address of the location where system call is made • syscall_id is only 8 bit (only about 200 syscalls exist in Linux)

Authentication • Assume: – Non-bypassibility - Every time a program makes system call, we always intercept it before the kernel. – Memory trace inspection – We need to inspect the stack of the program. • Method: – Decrypt the signed_id. • (token || syscall_id) = Dk(%eax) # %eax contains the signed_id – Inspect the program stack for return address. Compute token of the address: • check_token = F(Memory[%esp]) – If check_token == token, then • set %eax = syscall_id • Forward the system call to kernel – Otherwise fail

Authentication • Assume: – Non-bypassibility - Every time a program makes system call, we always intercept it before the kernel. – Memory trace inspection – We need to inspect the stack of the program. • Method: – Decrypt the signed_id. • (token || syscall_id) = Dk(%eax) # %eax contains the signed_id – Inspect the program stack for return address. Compute token of the address: • check_token = F(Memory[%esp]) – If check_token == token, then • set %eax = syscall_id • Forward the system call to kernel – Otherwise fail

Outline • Higher level view of attack space • Solution approach and how it defeats these attacks • Possible implementation approaches and the choices made in DAWSON • Vulnerabilities • Analysis of increase in attack effort due to DAWSON – Another way of answering “how many of N copies are vulnerable to an attack”

Outline • Higher level view of attack space • Solution approach and how it defeats these attacks • Possible implementation approaches and the choices made in DAWSON • Vulnerabilities • Analysis of increase in attack effort due to DAWSON – Another way of answering “how many of N copies are vulnerable to an attack”

Memory Error Exploits • Behind 80% of CERT advisories in last 2 years – Numbers have increased from about 50% over past 5+ years – Even faster increase in newer types of memory error exploits • Roughly half of the advisories are due to heap or integer overflows and format strings – Mechanism of choice in “mass-market” attacks • Implication: memory error exploits will continue to dominate in the next several years

Memory Error Exploits • Behind 80% of CERT advisories in last 2 years – Numbers have increased from about 50% over past 5+ years – Even faster increase in newer types of memory error exploits • Roughly half of the advisories are due to heap or integer overflows and format strings – Mechanism of choice in “mass-market” attacks • Implication: memory error exploits will continue to dominate in the next several years

Overview of Memory Errors • Memory error = pointer expression accessing “unintended object” • Two basic types – Spatial error • Out-of-bounds access • Corrupted or uninitialized pointer access – Temporal error • dangling pointer access • Significant for stack-allocated and heapallocated objects

Overview of Memory Errors • Memory error = pointer expression accessing “unintended object” • Two basic types – Spatial error • Out-of-bounds access • Corrupted or uninitialized pointer access – Temporal error • dangling pointer access • Significant for stack-allocated and heapallocated objects

Memory Error Exploits • Temporal and uninitialized pointer errors haven’t yet been exploited • Pointer corruption is most popular • Typically, multiple memory errors used – Stack-smashing = out-of-bounds write + use of corrupted pointer – Heap overflow = out-of-bounds write + use of 2 corrupted pointers • Attack = Exploit + Payload execution – DAWSON Layer 1 breaks exploit phase using address space randomization

Memory Error Exploits • Temporal and uninitialized pointer errors haven’t yet been exploited • Pointer corruption is most popular • Typically, multiple memory errors used – Stack-smashing = out-of-bounds write + use of corrupted pointer – Heap overflow = out-of-bounds write + use of 2 corrupted pointers • Attack = Exploit + Payload execution – DAWSON Layer 1 breaks exploit phase using address space randomization

Address Space Randomization (ASR) • Absolute address randomization – Randomize absolute address of an object – Distances between objects may not be randomized • Relative address randomization – Randomize distances between objects, even those within the same segment

Address Space Randomization (ASR) • Absolute address randomization – Randomize absolute address of an object – Distances between objects may not be randomized • Relative address randomization – Randomize distances between objects, even those within the same segment

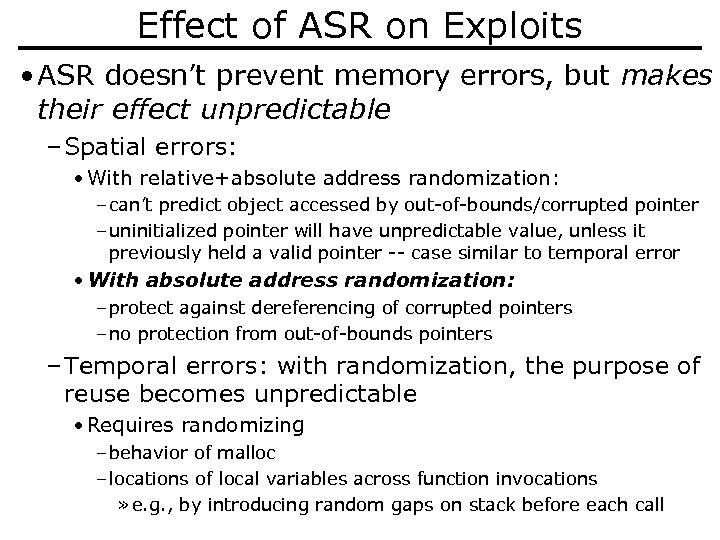

Effect of ASR on Exploits • ASR doesn’t prevent memory errors, but makes their effect unpredictable – Spatial errors: • With relative+absolute address randomization: – can’t predict object accessed by out-of-bounds/corrupted pointer – uninitialized pointer will have unpredictable value, unless it previously held a valid pointer -- case similar to temporal error • With absolute address randomization: – protect against dereferencing of corrupted pointers – no protection from out-of-bounds pointers – Temporal errors: with randomization, the purpose of reuse becomes unpredictable • Requires randomizing – behavior of malloc – locations of local variables across function invocations » e. g. , by introducing random gaps on stack before each call

Effect of ASR on Exploits • ASR doesn’t prevent memory errors, but makes their effect unpredictable – Spatial errors: • With relative+absolute address randomization: – can’t predict object accessed by out-of-bounds/corrupted pointer – uninitialized pointer will have unpredictable value, unless it previously held a valid pointer -- case similar to temporal error • With absolute address randomization: – protect against dereferencing of corrupted pointers – no protection from out-of-bounds pointers – Temporal errors: with randomization, the purpose of reuse becomes unpredictable • Requires randomizing – behavior of malloc – locations of local variables across function invocations » e. g. , by introducing random gaps on stack before each call

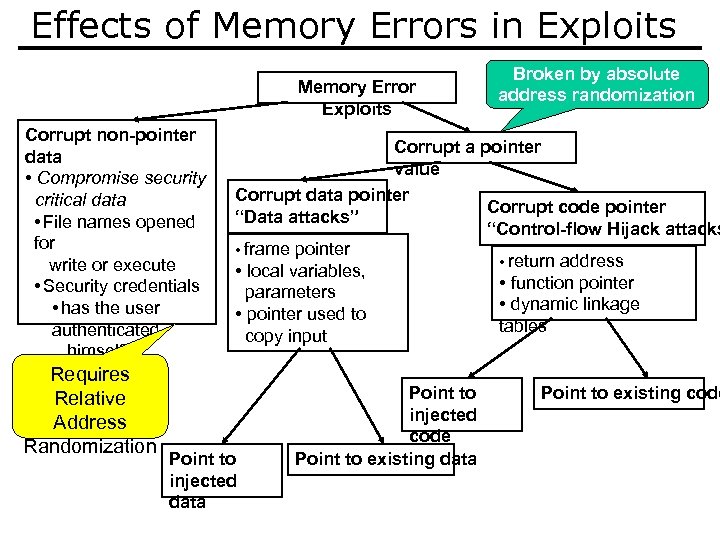

Effects of Memory Errors in Exploits Memory Error Exploits Corrupt non-pointer data • Compromise security critical data • File names opened for write or execute • Security credentials • has the user authenticated himself? Requires Relative Address Randomization Broken by absolute address randomization Corrupt a pointer value Corrupt data pointer Corrupt code pointer “Data attacks” “Control-flow Hijack attacks • frame pointer • return address • local variables, • function pointer parameters • dynamic linkage • pointer used to tables copy input Point to injected data Point to injected code Point to existing data Point to existing code

Effects of Memory Errors in Exploits Memory Error Exploits Corrupt non-pointer data • Compromise security critical data • File names opened for write or execute • Security credentials • has the user authenticated himself? Requires Relative Address Randomization Broken by absolute address randomization Corrupt a pointer value Corrupt data pointer Corrupt code pointer “Data attacks” “Control-flow Hijack attacks • frame pointer • return address • local variables, • function pointer parameters • dynamic linkage • pointer used to tables copy input Point to injected data Point to injected code Point to existing data Point to existing code

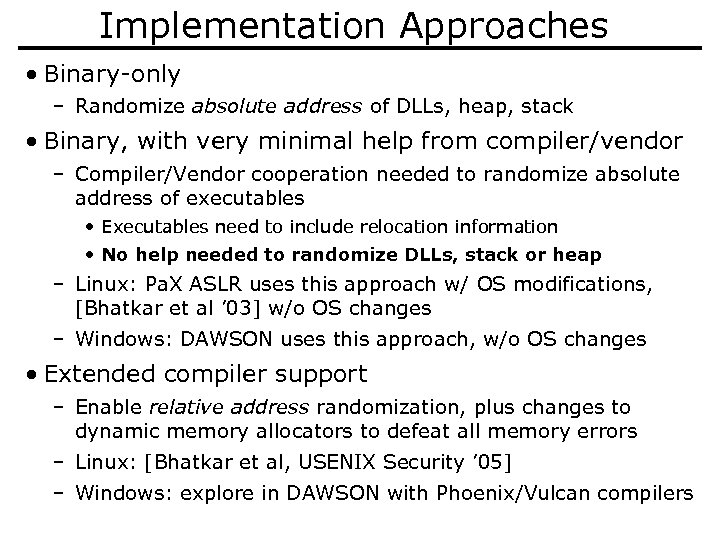

Implementation Approaches • Binary-only – Randomize absolute address of DLLs, heap, stack • Binary, with very minimal help from compiler/vendor – Compiler/Vendor cooperation needed to randomize absolute address of executables • Executables need to include relocation information • No help needed to randomize DLLs, stack or heap – Linux: Pa. X ASLR uses this approach w/ OS modifications, [Bhatkar et al ’ 03] w/o OS changes – Windows: DAWSON uses this approach, w/o OS changes • Extended compiler support – Enable relative address randomization, plus changes to dynamic memory allocators to defeat all memory errors – Linux: [Bhatkar et al, USENIX Security ’ 05] – Windows: explore in DAWSON with Phoenix/Vulcan compilers

Implementation Approaches • Binary-only – Randomize absolute address of DLLs, heap, stack • Binary, with very minimal help from compiler/vendor – Compiler/Vendor cooperation needed to randomize absolute address of executables • Executables need to include relocation information • No help needed to randomize DLLs, stack or heap – Linux: Pa. X ASLR uses this approach w/ OS modifications, [Bhatkar et al ’ 03] w/o OS changes – Windows: DAWSON uses this approach, w/o OS changes • Extended compiler support – Enable relative address randomization, plus changes to dynamic memory allocators to defeat all memory errors – Linux: [Bhatkar et al, USENIX Security ’ 05] – Windows: explore in DAWSON with Phoenix/Vulcan compilers

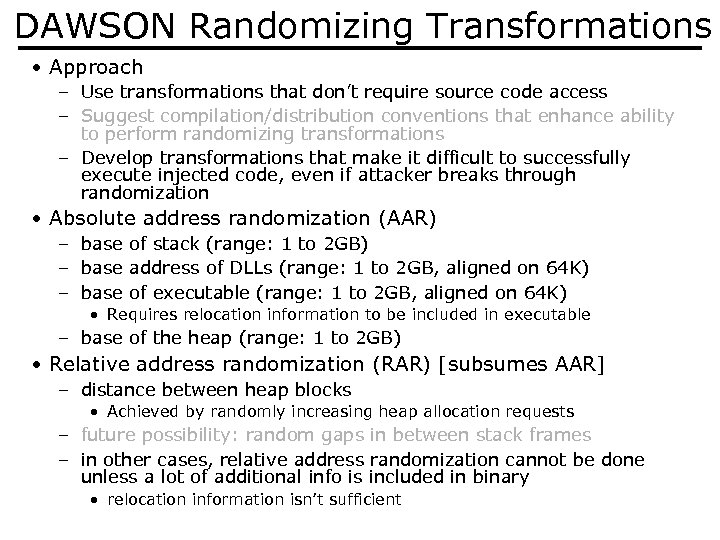

DAWSON Randomizing Transformations • Approach – Use transformations that don’t require source code access – Suggest compilation/distribution conventions that enhance ability to perform randomizing transformations – Develop transformations that make it difficult to successfully execute injected code, even if attacker breaks through randomization • Absolute address randomization (AAR) – base of stack (range: 1 to 2 GB) – base address of DLLs (range: 1 to 2 GB, aligned on 64 K) – base of executable (range: 1 to 2 GB, aligned on 64 K) • Requires relocation information to be included in executable – base of the heap (range: 1 to 2 GB) • Relative address randomization (RAR) [subsumes AAR] – distance between heap blocks • Achieved by randomly increasing heap allocation requests – future possibility: random gaps in between stack frames – in other cases, relative address randomization cannot be done unless a lot of additional info is included in binary • relocation information isn’t sufficient

DAWSON Randomizing Transformations • Approach – Use transformations that don’t require source code access – Suggest compilation/distribution conventions that enhance ability to perform randomizing transformations – Develop transformations that make it difficult to successfully execute injected code, even if attacker breaks through randomization • Absolute address randomization (AAR) – base of stack (range: 1 to 2 GB) – base address of DLLs (range: 1 to 2 GB, aligned on 64 K) – base of executable (range: 1 to 2 GB, aligned on 64 K) • Requires relocation information to be included in executable – base of the heap (range: 1 to 2 GB) • Relative address randomization (RAR) [subsumes AAR] – distance between heap blocks • Achieved by randomly increasing heap allocation requests – future possibility: random gaps in between stack frames – in other cases, relative address randomization cannot be done unless a lot of additional info is included in binary • relocation information isn’t sufficient

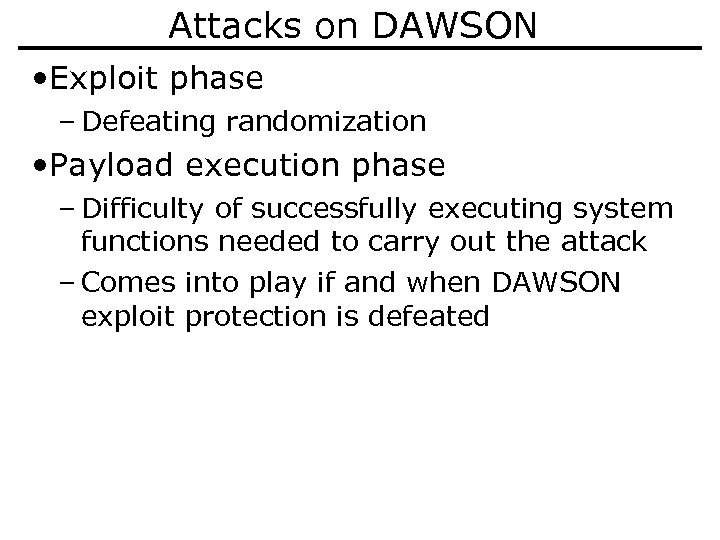

Attacks on DAWSON • Exploit phase – Defeating randomization • Payload execution phase – Difficulty of successfully executing system functions needed to carry out the attack – Comes into play if and when DAWSON exploit protection is defeated

Attacks on DAWSON • Exploit phase – Defeating randomization • Payload execution phase – Difficulty of successfully executing system functions needed to carry out the attack – Comes into play if and when DAWSON exploit protection is defeated

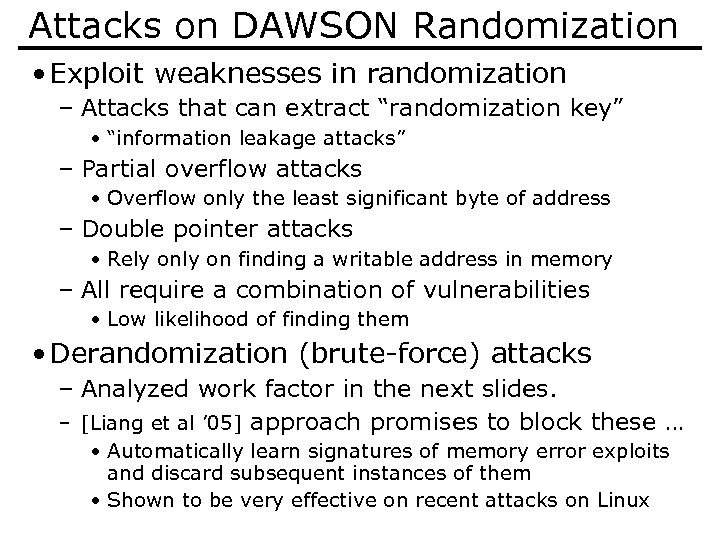

Attacks on DAWSON Randomization • Exploit weaknesses in randomization – Attacks that can extract “randomization key” • “information leakage attacks” – Partial overflow attacks • Overflow only the least significant byte of address – Double pointer attacks • Rely on finding a writable address in memory – All require a combination of vulnerabilities • Low likelihood of finding them • Derandomization (brute-force) attacks – Analyzed work factor in the next slides. – [Liang et al ’ 05] approach promises to block these … • Automatically learn signatures of memory error exploits and discard subsequent instances of them • Shown to be very effective on recent attacks on Linux

Attacks on DAWSON Randomization • Exploit weaknesses in randomization – Attacks that can extract “randomization key” • “information leakage attacks” – Partial overflow attacks • Overflow only the least significant byte of address – Double pointer attacks • Rely on finding a writable address in memory – All require a combination of vulnerabilities • Low likelihood of finding them • Derandomization (brute-force) attacks – Analyzed work factor in the next slides. – [Liang et al ’ 05] approach promises to block these … • Automatically learn signatures of memory error exploits and discard subsequent instances of them • Shown to be very effective on recent attacks on Linux

![Probability of Successful Attacks Pr(A) = Pr(V)/[EE(A) * PEE(A)] • Success probability of attack Probability of Successful Attacks Pr(A) = Pr(V)/[EE(A) * PEE(A)] • Success probability of attack](https://present5.com/presentation/8236d2505860d2ff13f5a1c690f377ef/image-63.jpg) Probability of Successful Attacks Pr(A) = Pr(V)/[EE(A) * PEE(A)] • Success probability of attack A exploiting vulnerability V • EE: “exploit effort” –Given by range of randomization of addresses involved in A • PEE: “payload execution effort” –Attempts to successfully execute “attack payload” • Multiplicative effect requires rerandomization after every failed attack

Probability of Successful Attacks Pr(A) = Pr(V)/[EE(A) * PEE(A)] • Success probability of attack A exploiting vulnerability V • EE: “exploit effort” –Given by range of randomization of addresses involved in A • PEE: “payload execution effort” –Attempts to successfully execute “attack payload” • Multiplicative effect requires rerandomization after every failed attack

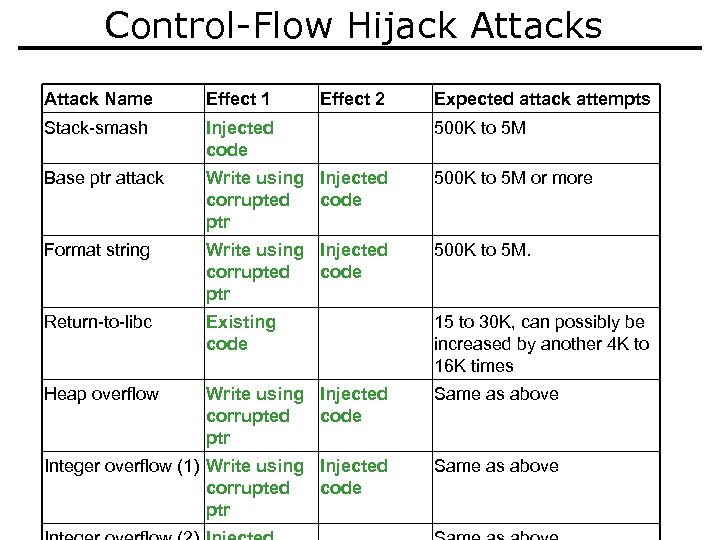

Control-Flow Hijack Attacks Attack Name Effect 1 Effect 2 Expected attack attempts Stack-smash Injected code 500 K to 5 M Base ptr attack Write using Injected corrupted code ptr 500 K to 5 M or more Format string Write using Injected corrupted code ptr 500 K to 5 M. Return-to-libc Existing code 15 to 30 K, can possibly be increased by another 4 K to 16 K times Heap overflow Write using Injected corrupted code ptr Same as above Integer overflow (1) Write using Injected corrupted code ptr Same as above

Control-Flow Hijack Attacks Attack Name Effect 1 Effect 2 Expected attack attempts Stack-smash Injected code 500 K to 5 M Base ptr attack Write using Injected corrupted code ptr 500 K to 5 M or more Format string Write using Injected corrupted code ptr 500 K to 5 M. Return-to-libc Existing code 15 to 30 K, can possibly be increased by another 4 K to 16 K times Heap overflow Write using Injected corrupted code ptr Same as above Integer overflow (1) Write using Injected corrupted code ptr Same as above

![Data Attacks Attack Name Effect 1 Effect 2 Expected attack attempts [Chen et al] Data Attacks Attack Name Effect 1 Effect 2 Expected attack attempts [Chen et al]](https://present5.com/presentation/8236d2505860d2ff13f5a1c690f377ef/image-65.jpg) Data Attacks Attack Name Effect 1 Effect 2 Expected attack attempts [Chen et al] Wu. Ftpd Write using corrupted pointer Corrupt data value 15 to 30 K, can possibly be increased by another 4 K to 16 K times [Chen et al] Null. Httpd Write using corrupted pointer Corrupt data value Same as above [Chen et al] Telnetd Write using corrupted pointer Corrupt data value Same as above [Chen et al] GHttpd Write using corrupted pointer [Chen et al] Sshd Corrupt data value Same as above Need more details.

Data Attacks Attack Name Effect 1 Effect 2 Expected attack attempts [Chen et al] Wu. Ftpd Write using corrupted pointer Corrupt data value 15 to 30 K, can possibly be increased by another 4 K to 16 K times [Chen et al] Null. Httpd Write using corrupted pointer Corrupt data value Same as above [Chen et al] Telnetd Write using corrupted pointer Corrupt data value Same as above [Chen et al] GHttpd Write using corrupted pointer [Chen et al] Sshd Corrupt data value Same as above Need more details.

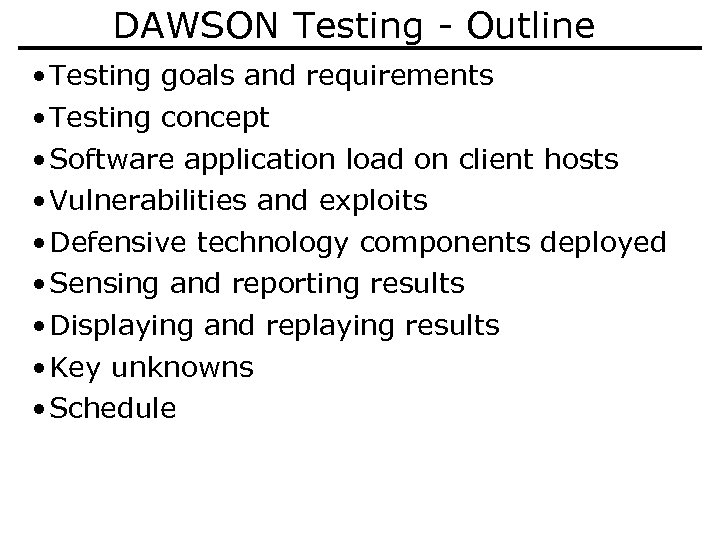

DAWSON Testing - Outline • Testing goals and requirements • Testing concept • Software application load on client hosts • Vulnerabilities and exploits • Defensive technology components deployed • Sensing and reporting results • Displaying and replaying results • Key unknowns • Schedule

DAWSON Testing - Outline • Testing goals and requirements • Testing concept • Software application load on client hosts • Vulnerabilities and exploits • Defensive technology components deployed • Sensing and reporting results • Displaying and replaying results • Key unknowns • Schedule

T&E Goals and Requirements • Demonstrate that address randomization defeats all types of memory error attacks, especially nonstack smashing attacks • Results to date from June testing – replay & summary • Plans for future testing • Red Team will address impact of targeted attacks

T&E Goals and Requirements • Demonstrate that address randomization defeats all types of memory error attacks, especially nonstack smashing attacks • Results to date from June testing – replay & summary • Plans for future testing • Red Team will address impact of targeted attacks

Additional Testing Requirements • Approaches to Vulnerability Testing: – Find new vulnerabilities in real applications or – Inject new vulnerabilities into real application or – Build new vulnerabilities into synthetic application • We chose to build vulnerabilities into synthetic application because exploitation was easier • Also had to build exploits that were automatable and observable

Additional Testing Requirements • Approaches to Vulnerability Testing: – Find new vulnerabilities in real applications or – Inject new vulnerabilities into real application or – Build new vulnerabilities into synthetic application • We chose to build vulnerabilities into synthetic application because exploitation was easier • Also had to build exploits that were automatable and observable

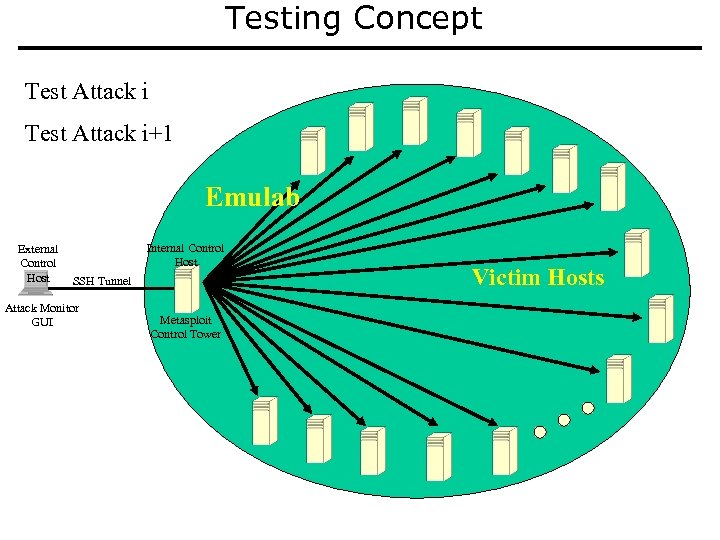

Testing Concept Test Attack i+1 Emulab External Control Host Internal Control Host SSH Tunnel Attack Monitor GUI Metasploit Control Tower Victim Hosts

Testing Concept Test Attack i+1 Emulab External Control Host Internal Control Host SSH Tunnel Attack Monitor GUI Metasploit Control Tower Victim Hosts

Details of Testing Concept • Build synthetic application with exploitable advanced memory error vulnerabilities • Build associated exploits and new marker payload • Incorporate attacks and payload into Metasploit • Automate Emulab startup of 100+ victim hosts with real and synthetic applications and defensive technologies • Automate control of defenses (e. g. , some, all or none) • Automate script to launch each attack against each victim host in Emulab and iterate until experiment is complete • Report on and display attack launches and successful/unsuccessful exploits – Within each trial – Cumulative across trials and experiments • Capture data from each trial for later replay and analysis • Design experiments to: – Validate DAWSON performance against program metrics – Measure value of transforms against different types of attacks by turning one or more on and off in different experiments

Details of Testing Concept • Build synthetic application with exploitable advanced memory error vulnerabilities • Build associated exploits and new marker payload • Incorporate attacks and payload into Metasploit • Automate Emulab startup of 100+ victim hosts with real and synthetic applications and defensive technologies • Automate control of defenses (e. g. , some, all or none) • Automate script to launch each attack against each victim host in Emulab and iterate until experiment is complete • Report on and display attack launches and successful/unsuccessful exploits – Within each trial – Cumulative across trials and experiments • Capture data from each trial for later replay and analysis • Design experiments to: – Validate DAWSON performance against program metrics – Measure value of transforms against different types of attacks by turning one or more on and off in different experiments

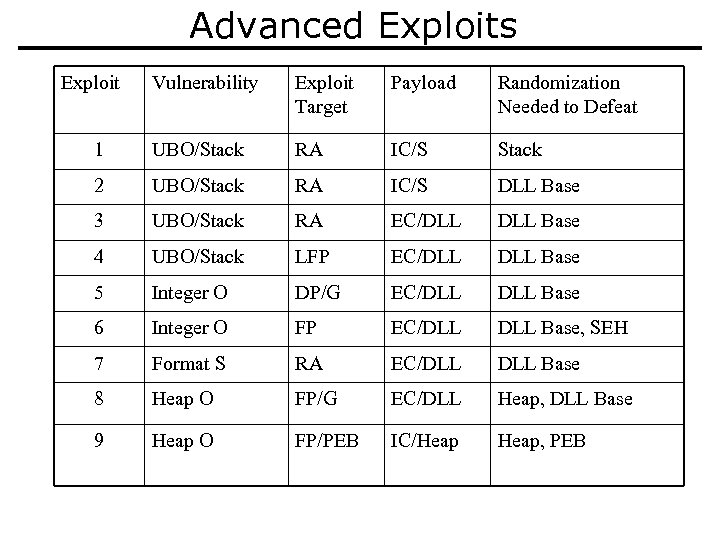

Advanced Exploits Exploit Vulnerability Exploit Target Payload Randomization Needed to Defeat 1 UBO/Stack RA IC/S Stack 2 UBO/Stack RA IC/S DLL Base 3 UBO/Stack RA EC/DLL Base 4 UBO/Stack LFP EC/DLL Base 5 Integer O DP/G EC/DLL Base 6 Integer O FP EC/DLL Base, SEH 7 Format S RA EC/DLL Base 8 Heap O FP/G EC/DLL Heap, DLL Base 9 Heap O FP/PEB IC/Heap, PEB

Advanced Exploits Exploit Vulnerability Exploit Target Payload Randomization Needed to Defeat 1 UBO/Stack RA IC/S Stack 2 UBO/Stack RA IC/S DLL Base 3 UBO/Stack RA EC/DLL Base 4 UBO/Stack LFP EC/DLL Base 5 Integer O DP/G EC/DLL Base 6 Integer O FP EC/DLL Base, SEH 7 Format S RA EC/DLL Base 8 Heap O FP/G EC/DLL Heap, DLL Base 9 Heap O FP/PEB IC/Heap, PEB

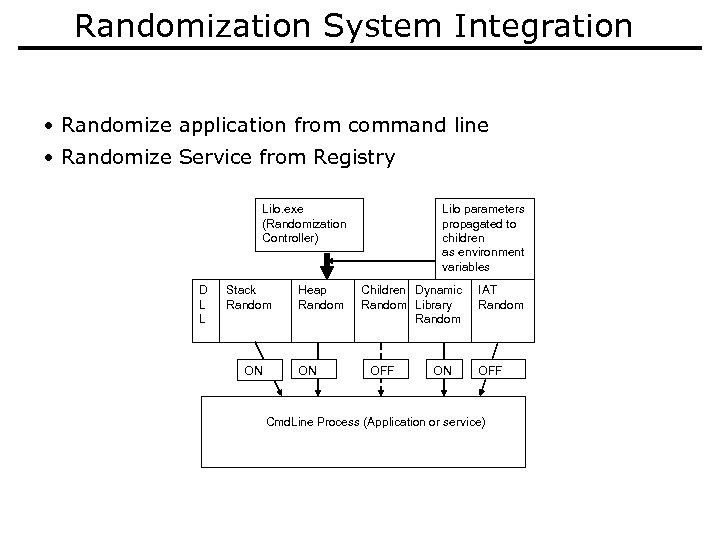

Randomization System Integration • Randomize application from command line • Randomize Service from Registry Lilo. exe (Randomization Controller) D L L Stack Random ON Heap Random ON Lilo parameters propagated to children as environment variables Children Dynamic Random Library Random OFF ON IAT Random OFF Cmd. Line Process (Application or service)

Randomization System Integration • Randomize application from command line • Randomize Service from Registry Lilo. exe (Randomization Controller) D L L Stack Random ON Heap Random ON Lilo parameters propagated to children as environment variables Children Dynamic Random Library Random OFF ON IAT Random OFF Cmd. Line Process (Application or service)

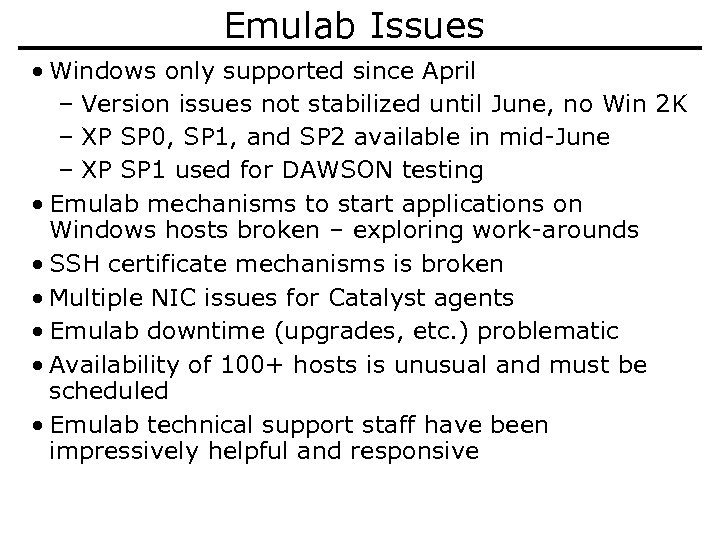

Emulab Issues • Windows only supported since April – Version issues not stabilized until June, no Win 2 K – XP SP 0, SP 1, and SP 2 available in mid-June – XP SP 1 used for DAWSON testing • Emulab mechanisms to start applications on Windows hosts broken – exploring work-arounds • SSH certificate mechanisms is broken • Multiple NIC issues for Catalyst agents • Emulab downtime (upgrades, etc. ) problematic • Availability of 100+ hosts is unusual and must be scheduled • Emulab technical support staff have been impressively helpful and responsive

Emulab Issues • Windows only supported since April – Version issues not stabilized until June, no Win 2 K – XP SP 0, SP 1, and SP 2 available in mid-June – XP SP 1 used for DAWSON testing • Emulab mechanisms to start applications on Windows hosts broken – exploring work-arounds • SSH certificate mechanisms is broken • Multiple NIC issues for Catalyst agents • Emulab downtime (upgrades, etc. ) problematic • Availability of 100+ hosts is unusual and must be scheduled • Emulab technical support staff have been impressively helpful and responsive

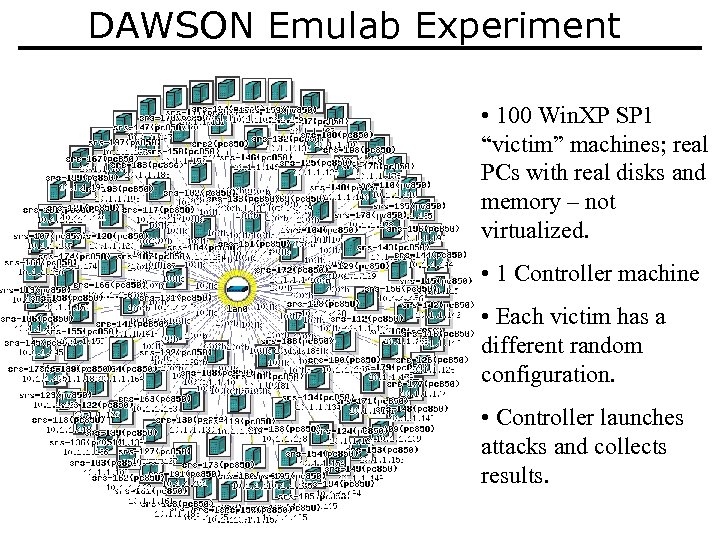

DAWSON Emulab Experiment • 100 Win. XP SP 1 “victim” machines; real PCs with real disks and memory – not virtualized. • 1 Controller machine • Each victim has a different random configuration. • Controller launches attacks and collects results.

DAWSON Emulab Experiment • 100 Win. XP SP 1 “victim” machines; real PCs with real disks and memory – not virtualized. • 1 Controller machine • Each victim has a different random configuration. • Controller launches attacks and collects results.

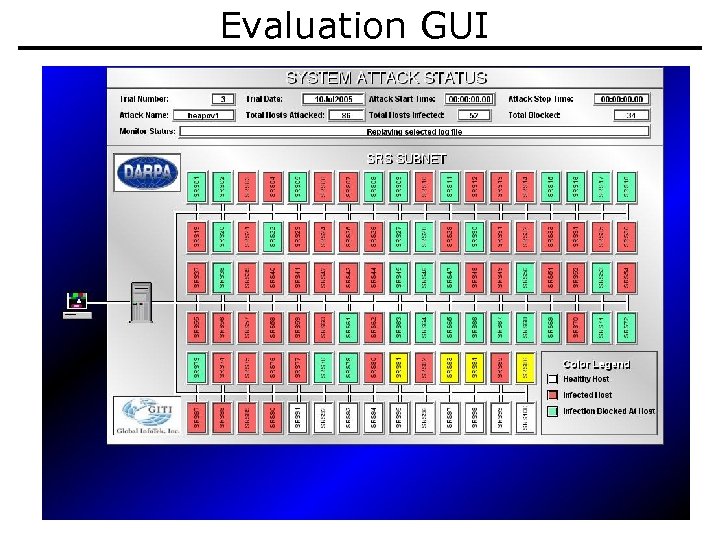

Evaluation GUI

Evaluation GUI

Vulnerabilities & Exploits • Windows XP SP 1 – Lsass – RPC-DCOM • Microsoft SQL Server Desktop Edition (MSDE) 2000 from the Office XP (MSDN Disk 0818) – Pre-authentication – Resolution server • Synthetic application (running as service if possible) – Heap overflow (one definite, one with no exploit) – Buffer overflow (four variants) – Integer overflow (two variants) – Format string (one definite)

Vulnerabilities & Exploits • Windows XP SP 1 – Lsass – RPC-DCOM • Microsoft SQL Server Desktop Edition (MSDE) 2000 from the Office XP (MSDN Disk 0818) – Pre-authentication – Resolution server • Synthetic application (running as service if possible) – Heap overflow (one definite, one with no exploit) – Buffer overflow (four variants) – Integer overflow (two variants) – Format string (one definite)

Defensive Technologies Deployed • DLL base randomization (except ntdll) • Stack randomization (except for initial thread) • Heap randomization • IAT randomization and DLL name string removal • Not deployed in test configuration currently – DLL name obfuscation – PEB masking • May have working version effective against Blaster soon

Defensive Technologies Deployed • DLL base randomization (except ntdll) • Stack randomization (except for initial thread) • Heap randomization • IAT randomization and DLL name string removal • Not deployed in test configuration currently – DLL name obfuscation – PEB masking • May have working version effective against Blaster soon

Sensing & Reporting • Markers written by successful attacks • Host agents sense marker file changes • Host agents report to Catalyst Monitor Display

Sensing & Reporting • Markers written by successful attacks • Host agents sense marker file changes • Host agents report to Catalyst Monitor Display

Initial Victim Host Software • Windows XP SP 1 • Cygwin (already part of image) • IIS v. 5. 1 • MSDE 2000 (from MS Office XP or 2000 disk) • Synthetic application • Java 1. 4. 1 • Catalyst Host Agent (probably only CT agent) – How will we start these applications at boot time • Others (Office, Winzip, Adobe Acrobat Reader, …)

Initial Victim Host Software • Windows XP SP 1 • Cygwin (already part of image) • IIS v. 5. 1 • MSDE 2000 (from MS Office XP or 2000 disk) • Synthetic application • Java 1. 4. 1 • Catalyst Host Agent (probably only CT agent) – How will we start these applications at boot time • Others (Office, Winzip, Adobe Acrobat Reader, …)

Initial Software for Internal Control Host • Windows XP SP 1 • Metasploit v. 2. 4+ updated with DAWSON exploits and payloads • Catalyst Control Tower • Java 1. 4. 1+ • Others (Office XP, Winzip, Adobe Acrobat Reader, …)

Initial Software for Internal Control Host • Windows XP SP 1 • Metasploit v. 2. 4+ updated with DAWSON exploits and payloads • Catalyst Control Tower • Java 1. 4. 1+ • Others (Office XP, Winzip, Adobe Acrobat Reader, …)

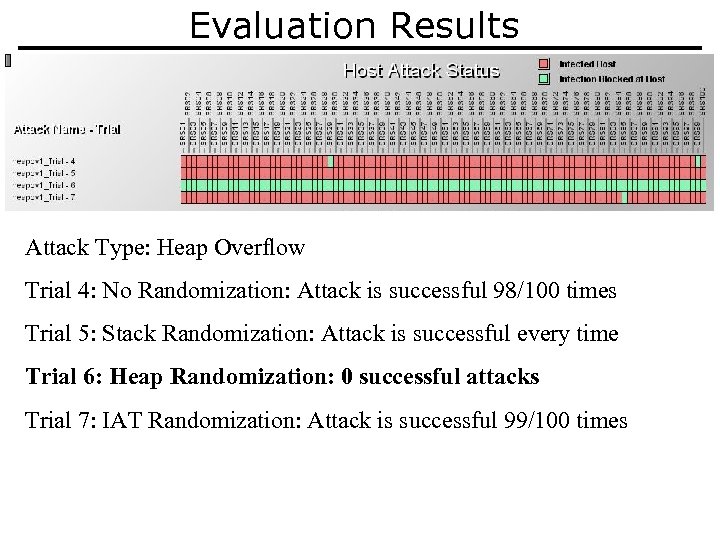

Evaluation Results Attack Type: Heap Overflow Trial 4: No Randomization: Attack is successful 98/100 times Trial 5: Stack Randomization: Attack is successful every time Trial 6: Heap Randomization: 0 successful attacks Trial 7: IAT Randomization: Attack is successful 99/100 times

Evaluation Results Attack Type: Heap Overflow Trial 4: No Randomization: Attack is successful 98/100 times Trial 5: Stack Randomization: Attack is successful every time Trial 6: Heap Randomization: 0 successful attacks Trial 7: IAT Randomization: Attack is successful 99/100 times

Summary • DAWSON is effective against attacks reported so far, and likely for future attacks as well. • Some residual vulnerabilities exist, but these are mainly theoretical possibilities at the moment • EE ranges between 13 K and 5 M for different attacks – In future, may be improved to between 500 K and 50 M

Summary • DAWSON is effective against attacks reported so far, and likely for future attacks as well. • Some residual vulnerabilities exist, but these are mainly theoretical possibilities at the moment • EE ranges between 13 K and 5 M for different attacks – In future, may be improved to between 500 K and 50 M