Презентация лекции по политологии.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 31

Discipline Political Science Zhunusova Bota Nadirovna Teacher of Regional Studies Department cell phone: 87013092091, email: botanadir@mail. ru

1. Theme: Essence of Political Science and the Development of Political thought QUESTIONS OF THE LECTURE 1. Political Science, its essence, schools and trends 2. The essence of politics 3. Social-political ideas of thinkers of the West and the East

Recommended Literature 1. Brown, B. E. (2006)Comparative Politics. Notes and Readings (USA: Thomson Wadsworth) 2. Grigsby, E. (2005)Analysing Politics. An Introduction to Political Science (USA: Thomson Wadsworth) 3. Hauss, Ch. (2006)Comparative Politics. 5 -th edition. Domestic Responses to Global Challenges (USA: Thomson Wadsworth) 4. Jackson, R. J. and D. Jackson (2003)An introduction to Political Science. (Toronto: Pearson Education Canada Inc. )

Key issues 1. What are the defining features of politics as an activity? 2. How has «politics» been understood by various thinkers and traditions? 3. Does politics take place within all social institutions, or only in some? 4. What approaches to the study of politics as an academic discipline have been adopted?

Focus on… • Power is one of the basic categories of political science • Power can be said to be exercised whenever A gets B to do something that B would not otherwise have done. However, A can influence B in various ways. This allows us to distinguish between different dimensions of power. Please consider what are they?

Political science is a branch of social science that deals with theory and practice of politics and the description and analysis of political systems and political behavior. Political Science is often described as the study of who gets what, where, when and why. Discovering a proper balance between the individual, the society and its Government for civilization and human progress is paramount.

Fields and subfields of political science include political theory and philosophy, civics and comparative politics, theory of direct democracy, apolitical governance, participatory direct democracy, national systems, cross-national political analysis, political development, international relations, foreign policy, international law, politics, public administration, administrative behavior, public law, judicial behavior, and public policy. Political science also studies power in international relations and theory of Great powers and Superpowers.

Political science is methodologically diverse. Approaches to the discipline include classical political philosophy, interpretivism, structuralism, and behavioralism, realism, pluralism, and institutionalism. Political science, as one of the social sciences, uses methods and techniques that relate to the kinds of inquiries sought: primary sources such as historical documents and official records, secondary sources such as scholarly journal articles, survey research, statistical analysis, case studies, and model building.

Studies of political scientists Political scientists study the allocation and transfer of power in decision-making, the roles and systems of governance including governments and international organizations, political behavior and public policies. They measure the success of governance and specific policies by examining many factors, including stability, justice, material wealth, and peace. Some political scientists seek to advance positive theses by analyzing politics. Others advance normative theses, by making specific policy recommendations.

Frameworks of political science Political Scientists provide the frameworks that journalists, special interest groups, politicians, and the electorate analyze issues. Political scientists may serve as advisers to specific politicians, or even run for office as politicians themselves. Political scientists can be found working in governments, in political parties or as civil servants. They may be involved with nongovernmental

organizations (NGOs) or political movements. In a variety of capacities, people educated and trained in political science can add value and expertise to corporations. Private enterprises such as think tanks, research institutes, polling and public relations firms often employ political scientists. In the United States, political scientists known as "Americanists" look at a variety of data including elections, public opinion and public policy such as Social Security reform, foreign policy, U. S. congressional power, and the U. S. Supreme Court—to name only a few issues.

Universities offer B. A. programs in political science Most American colleges and universities offer B. A. programs in political science. M. A. and Ph. D programs are common at larger universities. Some universities offer B. S or M. S. degrees. The term political science is more popular in North America than elsewhere; other institutions, especially those outside the United States, see political science as part of a broader discipline of political studies, politics, or government. While political science implies use of the scientific method, political studies implies a broader approach, although the naming of degree courses does not necessarily reflect their content.

History of development of political science Confucius The Chinese philosopher Confucius (551 -471 BC) was one of the first thinkers to adopt a distinct approach to political philosophy. His philosophy was "rooted in his belief that a ruler should learn self-discipline, should govern his subjects by his own example, and should treat them with love and concern. "

His political beliefs were strongly linked to personal ethics and morality, believing that only a morally upright ruler who possessed "de", or virtue, should be able to exercise power, and that the behavior of an individual ought to be consistent with their rank in society. He stated that "Good government consists in the ruler being a ruler, the minister being a minister, the father being a father, and the son being a son. "

Full name: Plato (Πλάτων) Plato The Greek philosopher Plato(428348 BC), in his book The Republic, argued that all conventional political systems (democracy, monarchy, oligarchy and timarchy) were inherently corrupt, and that the state ought to be governed by an elite class of educated philosopher-rulers, who would be trained from birth and

selected on the basis of aptitude: "those who have the greatest skill in watching over the community. " This has been characterised as authoritarian and elitist by some later scholars, notably Karl Popper in his book The Open Society and its Enemies, who described Plato's schemes as essentially totalitarian and criticised his apparent advocacy of censorship. ] The Republic has also been labeled as communist, due to its advocacy of abolishing private property and the family among the ruling classes; however, this view has been discounted by many scholars, as there are implications in the text that this will extend only to the ruling classes, and that ordinary citizens "will have enough private property to make the regulation of wealth and poverty a concern. "

Aristotle In his book Politics, the Greek philosopher Aristotle(384– 322 BC) asserted that man is, by nature, a political animal. He argued that ethics and politics are closely linked, and that a truly ethical life can only be lived by someone who participates in politics. Like Plato, Aristotle identified a number of different forms of government, and argued that each "correct" form of government may devolve into a "deviant" form of government, in which its institutions were corrupted.

• According to Aristotle, kingship, with one ruler, devolves into tyranny; aristocracy, with a small group of rulers, devolves into oligarchy; and polity, with collective rule by many citizens, devolves into democracy. In this sense, Aristotle does not use the word "democracy" in its modern sense, carrying positive connotations, but in its literal sense of rule by the demos, or common people. A more accurate view of Aristotle denouncing democracy was that it was described as mob rule, or ochlocracy.

Niccolò Machiavelli, one of the most influential political scientists In his work The Prince, the Renaissance Italian political theorist Machiavelli put forward a political worldview which described practical methods for an absolute ruler to attain and maintain political power. His work is sometimes viewed as rejecting traditional views of morality for a ruler: "for Machiavelli, there is no moral basis on which to judge the difference between legitimate and illegitimate uses of power. "

It is from Machiavelli that the term Machiavellian is derived, referring to an amoral person who uses manipulative methods to attain power; his works have been studied and theories practiced by leaders including totalitarians such as Benito Mussolini, and Adolf Hitler, each of whom justified the use of brutality for purposes of state security. However, many scholars have questioned this view of Machiavelli's theory, arguing that "Machiavelli did not invent 'Machiavellianism' and may not even have been a 'Machiavellian' in the sense often ascribed to him. " Instead, Machiavelli considered the stability of the state to be the most important goal, and argued that qualities traditionally considered morally desirable, such as generosity, were undesirable in a ruler and would lead to the loss of power.

John Locke In the First Treatise of Government, Locke refutes theory of the Divine Right of Kings as put forward by Robert Filmer; he "minutely examines key Biblical passages" and concludes that absolute monarchy is not supported by Christian theology. "Locke singles out Filmer's contention that men are not 'naturally free' as the key issue, for that is the 'ground'. . . on which Filmer erects his argument for the claim that all 'legitimate' government is 'absolute monarchy'. "

In the Second Treatise of Government, Locke examines the concept of the social contract put forward by other theorists such as Thomas Hobbes, but reaches a different conclusion. Although he agreed with Hobbes on the concept of a state of nature before existing forms of government arose, he challenged Hobbes' view that the state of nature was equivalent to a state of war, instead arguing that there were certain natural rights belonging to all human beings, which continued even after a political authority was established. "The state of nature has a law of nature to govern it, which obliges everyone. . . being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, liberty, health or possessions". According to one scholar, the basis of Locke's thought in the Second Treatise is that "contract or consent is the ground of government and fixes its limits. . . behind [this] doctrine lies the idea of the independence of the individual person. " In other words, Locke's view was different from Hobbes' in that he interpreted the idea of the "state of nature" differently, and he argued that people's natural rights were not necessarily eliminated by their consent to be governed by a political authority.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau The 18 th century French philosopher Jean. Jacques Rousseau, in his book The Social Contract, put forward a system of political thought which was closely related to those of Hobbes and Locke, but different in important respects. In the opening sentence of the book, Rousseau argued that ". . . man was born free, but he is everywhere in chains" He defined political authority and legitimacy as stemming from the "general will", or volonté generale; for Rousseau, "true Sovereignty is directed always at the public good". This concept of the general will implicitly "allows for individual diversity and freedom. . . [but] also encourages the well-being of the whole, and therefore can conflict with the particular interests of individuals. "

As such, Rousseau also argues that the people may need a "lawgiver" to draw up a constitution and system of laws, because the general will, "while always morally sound, is sometimes mistaken". Rousseau's thought has been seen by some scholars as contradictory and inconsistent, and as not addressing the fundamental contradiction between individual freedom and subordination to the needs of society, "the tension that seems to exist between liberalism and communitarianism". As one Catholic scholar argues, "that it [The Social Contract] contains serious contradictions is undeniable. . . its fundamental principles-the origin of society, absolute freedom and absolute equality of all--are false and unnatural. " The Catholic Encyclopedia further argues that Rousseau's concept of the general will would inevitably lead to "the suppression of personality, the reign of force and caprice, the tyranny of the multitude, the despotism of the crowd", i. e. the subordination of the individual to society as a whole.

John Stuart Mill In the 19 th century, John Stuart Mill pioneered the liberal conception of politics. He saw democracy as the major political development of his era and, in his book On Liberty, advocated stronger protection for individual rights against government and the rule of the majority. He argued that liberty was the most important right of human beings, and that the only just cause for interfering with the liberty of another person was self-protection. One commentator refers to On Liberty as "the strongest and most eloquent defense of liberalism that we have. " Mill also emphasised the importance of freedom of speech, claiming that "we can never be sure that the opinion we are attempting to stifle is a false opinion, and if we were sure, stifling it would be an evil still. "

Karl Marx was among the most influential political philosophers of history. His theories, collectively termed Marxism, were critical of capitalism and argued that in the due course of history, there would be an "inevitable breakdown of capitalism for economic reasons, to be replaced by communism. " He defined history in terms of the class struggle between the bourgeoisie, or property-owning classes, and the proletariat, or workers, a struggle intensified by industrialisation:

The development of Modern Industry, therefore, cuts from under its feet the very foundation on which the bourgeoisie produces and appropriates products. What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable. Utopia for Marx was the classless society in which the state and the church would be very weak or nonexistent. The workers ultimately would own the means of production, state ownership would be a mere transition period, therefore the people would be free. Because the state as Marx knew it would practically disappear over time, there would be no need for borders so individuals would be free to move from nation to nation without prosecution. This latter idea of internationalism is the direct opposition to the Nazi utopia of the Master race and national socialism. Although Marxism is mostly associated with the Soviet Union for obvious reasons, one may also see in the European Union many but not all of Marx's ideas such as universal health care, open border and the free movement of people, and less economic inequality.

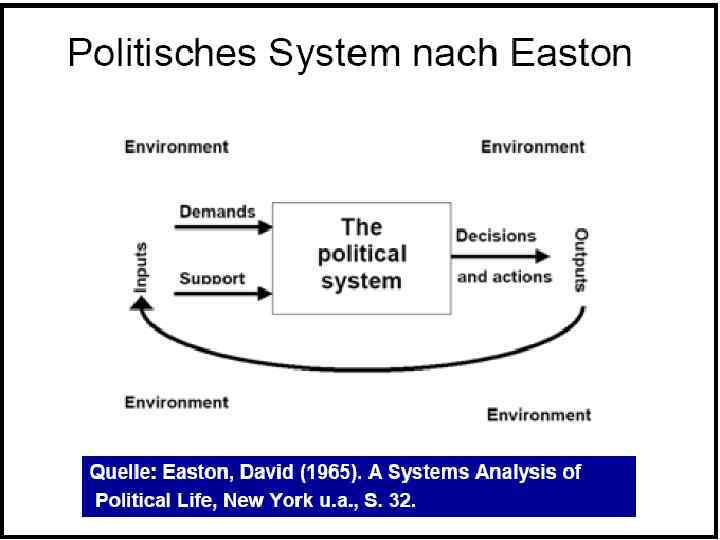

The political system by David Easton This ambitious model sets out to explain the entire political process, as well as the function of major political actors, through the application of what is called systems analysis. A system is an organized or complex whole, a set of interrelated and interdependent parts that form a collective entity. In the case of the political system, a linkage exists between what Easton calls ″inputs″ and ″outputs″. Inputs into the political system consist of demands and supports from the general public. .

Demands can range from pressure for higher living standards, improved employment prospects, and more generous welfare payments to greater protection for minority and individual rights. Supports are ways in which the public contributes to the political system by paying taxes, offering compliance, and being willing to participate in public life. Outputs consist of the decisions and actions of government, including the making of policy, the passing of laws, the imposition of taxes, and the allocation of public funds. These outputs generate ″feedback″, which in turn shapes further demands and supports. The political system tends towards long-term equilibrium or political stability, as its survival depends on outputs being brought into line with inputs.

Summary • So, politics is the activity through which people make, preserve and amend the general rules under which they live. As such, it is an essentially social activity, inextricably linked, on the one hand, to the existence of diversity and conflict, and on the other to a willingness to cooperate and act collectively. Politics is better seen as a search for conflict resolution than as its achievement, as not all conflicts are, or can be, resolved. • Politics has been understood differently by different thinkers and within different traditions. Politics has been viewed as the art of government or as ″what concerns the state″, as the conduct and management of public affairs, as the resolution of conflict through debate and compromise, and as the production, distribution and use of resources in the course of social existence.

Презентация лекции по политологии.ppt