diaphragmatichernia-100613045650-phpapp02 (1).pptx

- Количество слайдов: 37

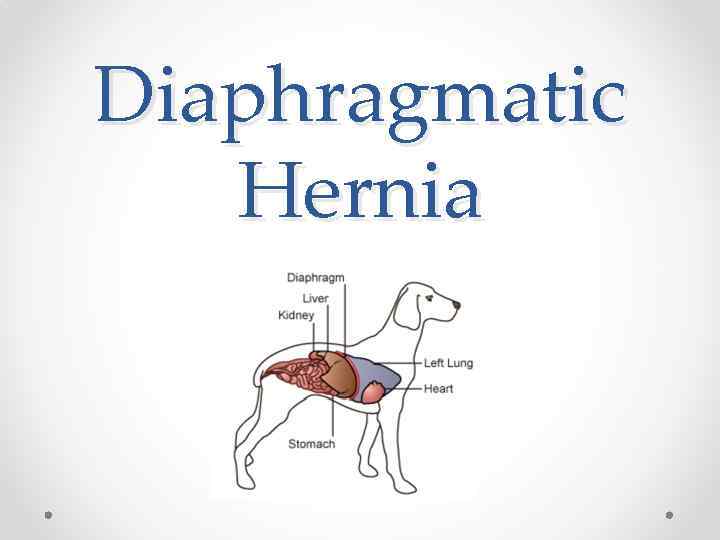

Diaphragmatic Hernia

Diaphragmatic Hernia

Intro • A hernia is an abnormal protrusion of an organ or a portion of it through the containing wall of its cavity, beyond its normal confines. • DH occurs when the continuity of the diaphragm is disrupted such that the abdominal organs can migrate into the thoracic cavity.

Intro • A hernia is an abnormal protrusion of an organ or a portion of it through the containing wall of its cavity, beyond its normal confines. • DH occurs when the continuity of the diaphragm is disrupted such that the abdominal organs can migrate into the thoracic cavity.

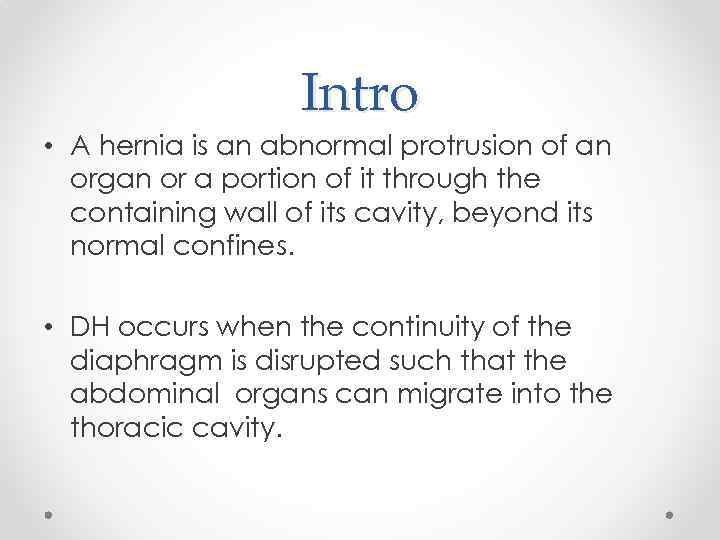

Applied Anatomy

Applied Anatomy

Types • Congenital Ø Pleuroperitoneal hernia Ø Peritoneopericardial hernia • Acquired-secondary to trauma. Congenital pleuroperitoneal hernias are seldom diagnosed in small animals because many affected animals die at birth or shortly thereafter.

Types • Congenital Ø Pleuroperitoneal hernia Ø Peritoneopericardial hernia • Acquired-secondary to trauma. Congenital pleuroperitoneal hernias are seldom diagnosed in small animals because many affected animals die at birth or shortly thereafter.

Traumatic Diaphragmatic Hernia

Traumatic Diaphragmatic Hernia

Cause • Direct , Indirect or Iatrogenic • Most diaphragmatic hernias in dogs and cats are caused by trauma, particularly motor vehicle accidents. • Diaphragmatic hernias may also occur in animals with connective tissue disorders.

Cause • Direct , Indirect or Iatrogenic • Most diaphragmatic hernias in dogs and cats are caused by trauma, particularly motor vehicle accidents. • Diaphragmatic hernias may also occur in animals with connective tissue disorders.

Pathophysiology • The abrupt increase in intraabdominal pressure accompanying forceful blows to the abdominal wall causes the lungs to rapidly deflate (&if the glottis is open), producing a large pleuroperitoneal pressure gradient. • The tears occur at the weakest points of the diaphragm, generally the muscular portions (mainly costal muscle). • Location and size of the tear or tears depend on the position of the animal at the time of impact and the location of the viscera. Also determines the viscera that gets herniated. • Types - Circumferential or radial or both • Right or Left

Pathophysiology • The abrupt increase in intraabdominal pressure accompanying forceful blows to the abdominal wall causes the lungs to rapidly deflate (&if the glottis is open), producing a large pleuroperitoneal pressure gradient. • The tears occur at the weakest points of the diaphragm, generally the muscular portions (mainly costal muscle). • Location and size of the tear or tears depend on the position of the animal at the time of impact and the location of the viscera. Also determines the viscera that gets herniated. • Types - Circumferential or radial or both • Right or Left

Clinical signs • The animals may be presented in shock acutely after the trauma (with or without associated injuries), or the hernia may be an incidental finding (during ovariohysterectomy surgeries). • chronic diaphragmatic hernia – • respiratory (i. e. , dyspnea, exercise intolerance) • gastrointestinal systems (i. e. , anorexia, vomiting, diarrhoea, weight loss, pain after ingestion of food) • nonspecific (e. g. , depression). • Many animals with chronic hernias are not dyspneic at the time of diagnosis.

Clinical signs • The animals may be presented in shock acutely after the trauma (with or without associated injuries), or the hernia may be an incidental finding (during ovariohysterectomy surgeries). • chronic diaphragmatic hernia – • respiratory (i. e. , dyspnea, exercise intolerance) • gastrointestinal systems (i. e. , anorexia, vomiting, diarrhoea, weight loss, pain after ingestion of food) • nonspecific (e. g. , depression). • Many animals with chronic hernias are not dyspneic at the time of diagnosis.

Clinical signs • Animals with recent traumatic diaphragmatic hernias frequently are in shock when presented with pale or cyanotic mucous membranes, tachypnea, tachycardia, and/or oliguria. Cardiac arrhythmias are common and associated with significant morbidity. • Clinical signs depend on which organs have herniated and may be attributed to the gastrointestinal, respiratory, or cardiovascular system. • liver - most commonly herniated organ, associated with hydrothorax caused by entrapment and venous occlusion. • Other organs – SI > stomach > spleen > omentun > pancreas > colon > rectum > uterus.

Clinical signs • Animals with recent traumatic diaphragmatic hernias frequently are in shock when presented with pale or cyanotic mucous membranes, tachypnea, tachycardia, and/or oliguria. Cardiac arrhythmias are common and associated with significant morbidity. • Clinical signs depend on which organs have herniated and may be attributed to the gastrointestinal, respiratory, or cardiovascular system. • liver - most commonly herniated organ, associated with hydrothorax caused by entrapment and venous occlusion. • Other organs – SI > stomach > spleen > omentun > pancreas > colon > rectum > uterus.

Diagnostic Imaging

Diagnostic Imaging

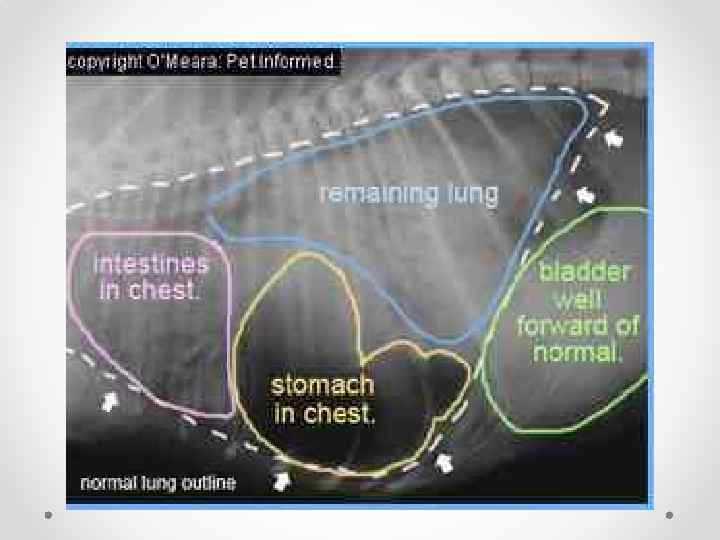

Diagnostic Imaging • Definitive diagnosis - radiography or ultrasonography. If significant pleural effusion is present, thoracentesis may be necessary. • Radiographic Signs Ø loss of the diaphragmatic line, Ø loss of the cardiac silhouette, Ø dorsal or lateral displacement of lung fields, Ø presence of gas or a barium-filled stomach or intestines in the thoracic cavity, Ø pleural effusion, Ø failure to observe the stomach or liver in the abdomen. • In a recent study, thoracic radiographs revealed evidence of diaphragmatic hernia in only 66% of affected animals.

Diagnostic Imaging • Definitive diagnosis - radiography or ultrasonography. If significant pleural effusion is present, thoracentesis may be necessary. • Radiographic Signs Ø loss of the diaphragmatic line, Ø loss of the cardiac silhouette, Ø dorsal or lateral displacement of lung fields, Ø presence of gas or a barium-filled stomach or intestines in the thoracic cavity, Ø pleural effusion, Ø failure to observe the stomach or liver in the abdomen. • In a recent study, thoracic radiographs revealed evidence of diaphragmatic hernia in only 66% of affected animals.

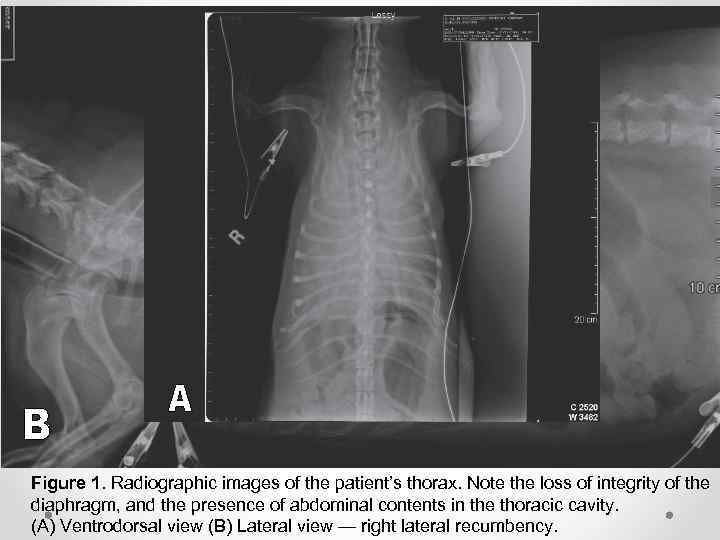

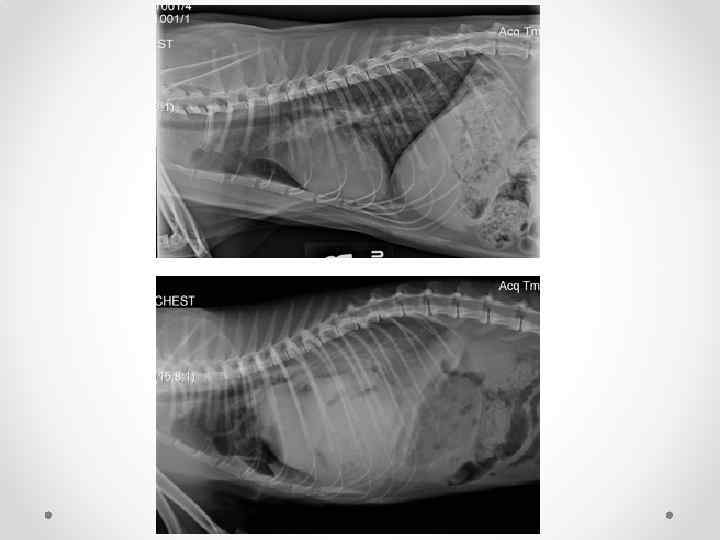

Figure 1. Radiographic images of the patient’s thorax. Note the loss of integrity of the diaphragm, and the presence of abdominal contents in the thoracic cavity. (A) Ventrodorsal view (B) Lateral view — right lateral recumbency.

Figure 1. Radiographic images of the patient’s thorax. Note the loss of integrity of the diaphragm, and the presence of abdominal contents in the thoracic cavity. (A) Ventrodorsal view (B) Lateral view — right lateral recumbency.

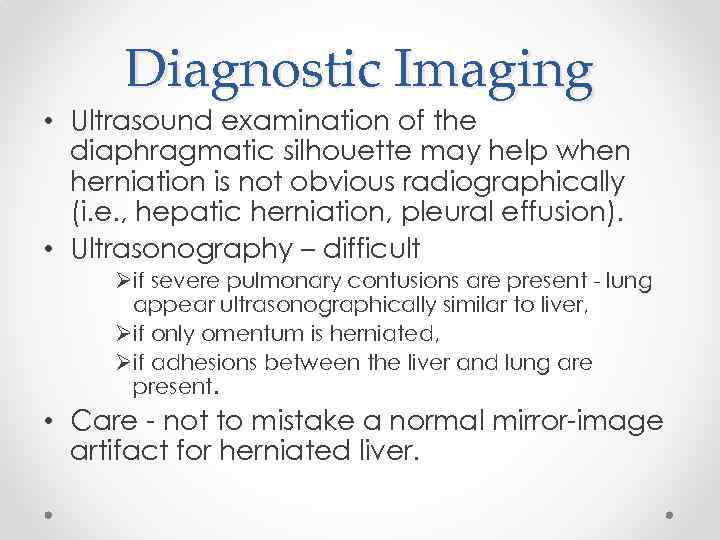

Diagnostic Imaging • Ultrasound examination of the diaphragmatic silhouette may help when herniation is not obvious radiographically (i. e. , hepatic herniation, pleural effusion). • Ultrasonography – difficult Øif severe pulmonary contusions are present - lung appear ultrasonographically similar to liver, Øif only omentum is herniated, Øif adhesions between the liver and lung are present. • Care - not to mistake a normal mirror-image artifact for herniated liver.

Diagnostic Imaging • Ultrasound examination of the diaphragmatic silhouette may help when herniation is not obvious radiographically (i. e. , hepatic herniation, pleural effusion). • Ultrasonography – difficult Øif severe pulmonary contusions are present - lung appear ultrasonographically similar to liver, Øif only omentum is herniated, Øif adhesions between the liver and lung are present. • Care - not to mistake a normal mirror-image artifact for herniated liver.

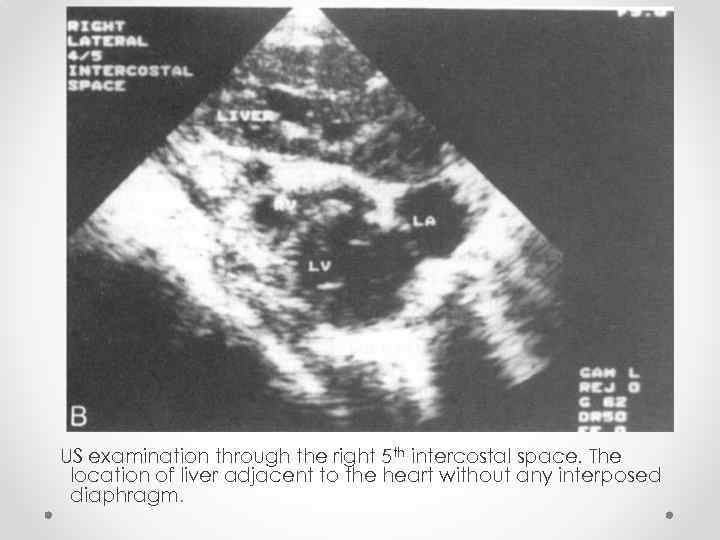

US examination through the right 5 th intercostal space. The location of liver adjacent to the heart without any interposed diaphragm.

US examination through the right 5 th intercostal space. The location of liver adjacent to the heart without any interposed diaphragm.

Diagnostic Imaging • Positive contrast celiography Ø Prewarmed water-soluble iodinated contrast agent Ø Intra Peritoneal @ 1. 1 ml/kg (dose doubled in ascites), Ø patient gently rolled from side to side or the pelvis is elevated, Ø films are taken immediately after the injection and manipulation. • Criteria for evaluation Ø presence of contrast medium in the pleural cavity, Ø absence of a normal liver lobe outline in the abdomen, Ø incomplete visualization of the abdominal surface of the diaphragm. • Positive-contrast celiograms should be interpreted cautiously, because omental and fibrous adhesions may seal the defect, resulting in false negative studies.

Diagnostic Imaging • Positive contrast celiography Ø Prewarmed water-soluble iodinated contrast agent Ø Intra Peritoneal @ 1. 1 ml/kg (dose doubled in ascites), Ø patient gently rolled from side to side or the pelvis is elevated, Ø films are taken immediately after the injection and manipulation. • Criteria for evaluation Ø presence of contrast medium in the pleural cavity, Ø absence of a normal liver lobe outline in the abdomen, Ø incomplete visualization of the abdominal surface of the diaphragm. • Positive-contrast celiograms should be interpreted cautiously, because omental and fibrous adhesions may seal the defect, resulting in false negative studies.

Medical Management • If the animal is dyspneic, oxygen should be provided by face mask, nasal insufflation, or an oxygen cage. • Positioning the animal in sternal recumbency with the forelimbs elevated may help ventilation. • If moderate or severe pleural effusion is present, thoracentesis should be performed. • Fluid therapy and antibiotics should be given if the animal is in shock.

Medical Management • If the animal is dyspneic, oxygen should be provided by face mask, nasal insufflation, or an oxygen cage. • Positioning the animal in sternal recumbency with the forelimbs elevated may help ventilation. • If moderate or severe pleural effusion is present, thoracentesis should be performed. • Fluid therapy and antibiotics should be given if the animal is in shock.

When should you repair the diaphragmatic hernia? The timing of surgical repair depends upon Ø The extent of the initial cardiopulmonary dysfunction, Ø The presence or absence of organ entrapment, Ø The degree of compromised pulmonary function, and Ø Whether or not the animal’s condition is improving, stable, or deteriorating. Ø Diaphragmatic herniorrhaphy may require immediate surgery if aggressive supportive care cannot stabilize respiratory function. Ø Acute dilatation of a herniated stomach or strangulated bowel are examples of situations where emergency surgery may be indicated.

When should you repair the diaphragmatic hernia? The timing of surgical repair depends upon Ø The extent of the initial cardiopulmonary dysfunction, Ø The presence or absence of organ entrapment, Ø The degree of compromised pulmonary function, and Ø Whether or not the animal’s condition is improving, stable, or deteriorating. Ø Diaphragmatic herniorrhaphy may require immediate surgery if aggressive supportive care cannot stabilize respiratory function. Ø Acute dilatation of a herniated stomach or strangulated bowel are examples of situations where emergency surgery may be indicated.

Preoperative Management • Prophylactic antibiotics in animals with hepatic herniation. • Massive release of toxins into the circulation may occur with hepatic strangulation or vascular compromise. Premedicating such patients with steroids may be beneficial. • An ECG should be performed on all trauma patients before surgery.

Preoperative Management • Prophylactic antibiotics in animals with hepatic herniation. • Massive release of toxins into the circulation may occur with hepatic strangulation or vascular compromise. Premedicating such patients with steroids may be beneficial. • An ECG should be performed on all trauma patients before surgery.

Anesthesia • Chamber or mask induction should be avoided. • Supplementing oxygen before induction improves myocardial oxygenation. • Drugs with minimal respiratory depressant effects. • Injectable anesthetics allowing rapid intubation are preferred. • Inhalation anesthetics should be used for maintenance of anesthesia. • The lungs should be allowed to expand slowly after surgery. • Nitrous oxide is contraindicated in patients with diaphragmatic hernia. • Intermittent positive pressure ventilation should be performed, and high inspiratory pressures should be avoided to help prevent reexpansion pulmonary edema. • Drugs such as methylprednisolone may be beneficial for preventing reexpansion pulmonary edema in animals with chronic diaphragmatic hernia.

Anesthesia • Chamber or mask induction should be avoided. • Supplementing oxygen before induction improves myocardial oxygenation. • Drugs with minimal respiratory depressant effects. • Injectable anesthetics allowing rapid intubation are preferred. • Inhalation anesthetics should be used for maintenance of anesthesia. • The lungs should be allowed to expand slowly after surgery. • Nitrous oxide is contraindicated in patients with diaphragmatic hernia. • Intermittent positive pressure ventilation should be performed, and high inspiratory pressures should be avoided to help prevent reexpansion pulmonary edema. • Drugs such as methylprednisolone may be beneficial for preventing reexpansion pulmonary edema in animals with chronic diaphragmatic hernia.

SURGICAL APPROACHES • A midline abdominal celiotomy (xiphoid to pubis) is the easiest and most versatile approach. • Positioning the patient's head toward the top of the table and tilting the table at a 30° to 40° angle will facilitate gravitation of abdominal viscera out of the thorax. • Rarely is it necessary to extend the incision into the thorax via a median sternotomy however the animal should be prepared in case this becomes necessary.

SURGICAL APPROACHES • A midline abdominal celiotomy (xiphoid to pubis) is the easiest and most versatile approach. • Positioning the patient's head toward the top of the table and tilting the table at a 30° to 40° angle will facilitate gravitation of abdominal viscera out of the thorax. • Rarely is it necessary to extend the incision into the thorax via a median sternotomy however the animal should be prepared in case this becomes necessary.

SURGICAL PROCEDURE • Incision is made from xiphoid to a point caudal to the umbilicus. Once the peritoneal cavity is opened, the diaphragm is exposed and the situation evaluated. • The herniated contents are replaced in their proper position and inspected for damage. • Torsion of one or more liver lobes, ruptured viscus, intussusception, costal abdominal hernia – should be expected • If adhesions exist, they should be broken down using blunt dissection so as to avoid excess hemorrhage and inadvertent damage to a vital structure. • Using large sponges or laparotomy pads moistened with warm saline, the liver and bowel are retracted caudally.

SURGICAL PROCEDURE • Incision is made from xiphoid to a point caudal to the umbilicus. Once the peritoneal cavity is opened, the diaphragm is exposed and the situation evaluated. • The herniated contents are replaced in their proper position and inspected for damage. • Torsion of one or more liver lobes, ruptured viscus, intussusception, costal abdominal hernia – should be expected • If adhesions exist, they should be broken down using blunt dissection so as to avoid excess hemorrhage and inadvertent damage to a vital structure. • Using large sponges or laparotomy pads moistened with warm saline, the liver and bowel are retracted caudally.

• All thoracic fluid should be aspirated. • The lungs should be expanded to remove atelectasis and to inspect for pulmonary tears and persistent areas of collapse. • Edges of the tear should be debrided • Recommended to suture the hernia from dorsal to ventral. • Hernia is closed with a single layer, simple continuous suture pattern using synthetic absorbable suture material (Dexon, Vicryl, PDS, Maxon) or monofilament nonabsorbable suture material (Nylon, Prolene, Novafil). • When tears near the caval hiatus are sutured, care is taken to avoid constriction of the vena cava by placing sutures to close to the cava.

• All thoracic fluid should be aspirated. • The lungs should be expanded to remove atelectasis and to inspect for pulmonary tears and persistent areas of collapse. • Edges of the tear should be debrided • Recommended to suture the hernia from dorsal to ventral. • Hernia is closed with a single layer, simple continuous suture pattern using synthetic absorbable suture material (Dexon, Vicryl, PDS, Maxon) or monofilament nonabsorbable suture material (Nylon, Prolene, Novafil). • When tears near the caval hiatus are sutured, care is taken to avoid constriction of the vena cava by placing sutures to close to the cava.

Air can be evacuated from the chest using several techniques. 1. Prior to tying the last knot of the hernial closure, a carmalt forceps is placed in the rent. 2. Intravenous catheter with a syringe 3. Needle thoracentesis 4. A 12 - to 14 -French feeding tube is brought into the peritoneal cavity through a paramedian stab incision in the cranioventral body wall. With the use of a 3 -way stopcock and 60 cc syringe, air is evacuated from the thorax until a gentle negative pressure is obtained. 5. A 12 - to 14 -French diameter thoracostomy tube can be placed in the 7 th or 8 th intercostal space.

Air can be evacuated from the chest using several techniques. 1. Prior to tying the last knot of the hernial closure, a carmalt forceps is placed in the rent. 2. Intravenous catheter with a syringe 3. Needle thoracentesis 4. A 12 - to 14 -French feeding tube is brought into the peritoneal cavity through a paramedian stab incision in the cranioventral body wall. With the use of a 3 -way stopcock and 60 cc syringe, air is evacuated from the thorax until a gentle negative pressure is obtained. 5. A 12 - to 14 -French diameter thoracostomy tube can be placed in the 7 th or 8 th intercostal space.

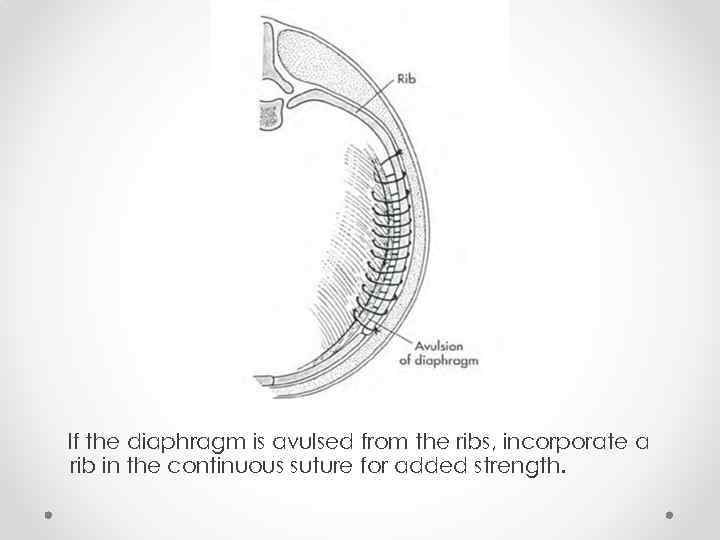

If the diaphragm is avulsed from the ribs, incorporate a rib in the continuous suture for added strength.

If the diaphragm is avulsed from the ribs, incorporate a rib in the continuous suture for added strength.

Peritoneopericardial Diaphragmatic Hernia

Peritoneopericardial Diaphragmatic Hernia

PPDH • Less commonly recognized by small animal clinicians than traumatic diaphragmatic hernias. • Although PPDH often are associated with respiratory embarrassment, asymptomatic PPDH is common. , • always congenital in dogs and cats • faulty development or prenatal injury of the septum transversum. -teratogen, genetic defect, or prenatal injury.

PPDH • Less commonly recognized by small animal clinicians than traumatic diaphragmatic hernias. • Although PPDH often are associated with respiratory embarrassment, asymptomatic PPDH is common. , • always congenital in dogs and cats • faulty development or prenatal injury of the septum transversum. -teratogen, genetic defect, or prenatal injury.

• Cardiac abnormalities and sternal deformities concomitant with PPDH. • The combination of congenital cranial abdominal wall, caudal sternal, diaphragmatic, and pericardial defects has been reported in dogs, often associated with ventricular septal defects or other intracardiac defects. • Polycystic kidneys have been reported in association with PPDH in cats. • Several breed predispositions have been recognized Dogs - Weimaraners and cocker spaniels Ø Cats - Domestic longhair and Himalayan Ø

• Cardiac abnormalities and sternal deformities concomitant with PPDH. • The combination of congenital cranial abdominal wall, caudal sternal, diaphragmatic, and pericardial defects has been reported in dogs, often associated with ventricular septal defects or other intracardiac defects. • Polycystic kidneys have been reported in association with PPDH in cats. • Several breed predispositions have been recognized Dogs - Weimaraners and cocker spaniels Ø Cats - Domestic longhair and Himalayan Ø

Diagnosis Signalment. • Not uncommon for the diagnosis to be made when the animal is middle aged or older because clinical signs vary and may be intermittent. may be at increased risk. History. • The clinical signs may be referable to the gastrointestinal, cardiac, or respiratory systems and include anorexia, depression, vomiting, diarrhoea, weight loss, wheezing, dyspnoea, exercise intolerance, and/or pain after eating. • Neurologic signs occur as a result of hepatoencephalopathy.

Diagnosis Signalment. • Not uncommon for the diagnosis to be made when the animal is middle aged or older because clinical signs vary and may be intermittent. may be at increased risk. History. • The clinical signs may be referable to the gastrointestinal, cardiac, or respiratory systems and include anorexia, depression, vomiting, diarrhoea, weight loss, wheezing, dyspnoea, exercise intolerance, and/or pain after eating. • Neurologic signs occur as a result of hepatoencephalopathy.

Physical Examination Findings • Ascites, muffled heart sounds, murmurs caused either by displacement of the heart by visceral organs or by intracardiac defects, and concurrent ventral abdominal wall defects. • The most commonly herniated organ is the liver, and associated pericardial effusion is common.

Physical Examination Findings • Ascites, muffled heart sounds, murmurs caused either by displacement of the heart by visceral organs or by intracardiac defects, and concurrent ventral abdominal wall defects. • The most commonly herniated organ is the liver, and associated pericardial effusion is common.

Diagnostic Imaging • Contrast studies (i. e. , nonselective angiogram, barium contrast study) - only if definitive diagnosis cannot be made on survey films or with ultrasound. • A distinct curvilinear radiopacity between the cardiac silhouette and the diaphragm on a lateral thoracic radiograph in cats with PPDH. the dorsal peritoneopericardial mesothelial remnant; • Ultrasonography is useful Ø Discontinuity of the diaphragmatic outline Ø Abdominal organs may be visualized in the pericardial sac. Hepatic herniation evident. • Echocardiography - performed in animals with murmurs.

Diagnostic Imaging • Contrast studies (i. e. , nonselective angiogram, barium contrast study) - only if definitive diagnosis cannot be made on survey films or with ultrasound. • A distinct curvilinear radiopacity between the cardiac silhouette and the diaphragm on a lateral thoracic radiograph in cats with PPDH. the dorsal peritoneopericardial mesothelial remnant; • Ultrasonography is useful Ø Discontinuity of the diaphragmatic outline Ø Abdominal organs may be visualized in the pericardial sac. Hepatic herniation evident. • Echocardiography - performed in animals with murmurs.

Surgical Treatment • Surgical repair should be performed as early as possible (generally when the animal is between 8 and 16 weeks of age), when it is unlikely that adhesions will be present • The pliable nature of the skin, muscles, sternum, and rib cage facilitates closure of large defects. Early correction of PPDH may prevent acute decompensation and the possible development of acute postoperative pulmonary oedema. • If the hernia is not diagnosed until the animal is older, conservative or surgical management may be used; • Some animals that are initially managed medically may have progression of clinical signs necessitating surgical intervention or resulting in death.

Surgical Treatment • Surgical repair should be performed as early as possible (generally when the animal is between 8 and 16 weeks of age), when it is unlikely that adhesions will be present • The pliable nature of the skin, muscles, sternum, and rib cage facilitates closure of large defects. Early correction of PPDH may prevent acute decompensation and the possible development of acute postoperative pulmonary oedema. • If the hernia is not diagnosed until the animal is older, conservative or surgical management may be used; • Some animals that are initially managed medically may have progression of clinical signs necessitating surgical intervention or resulting in death.

Preoperative Management • Prophylactic antibiotics should be given before induction of anesthesia in animals with hepatic herniation. • In animals with hepatic strangulation or vascular compromise, repositioning of the liver into the abdominal cavity may cause a massive release of toxins into the bloodstream; • premedicating such patients with steroids may be beneficial.

Preoperative Management • Prophylactic antibiotics should be given before induction of anesthesia in animals with hepatic herniation. • In animals with hepatic strangulation or vascular compromise, repositioning of the liver into the abdominal cavity may cause a massive release of toxins into the bloodstream; • premedicating such patients with steroids may be beneficial.

Anesthesia • Chamber or mask induction should be avoided. • Supplementing oxygen before induction improves myocardial oxygenation. • Drugs with minimal respiratory depressant effects. • Injectable anesthetics allowing rapid intubation are preferred. • Inhalation anesthetics should be used for maintenance of anesthesia. • The lungs should be allowed to expand slowly after surgery. • Nitrous oxide is contraindicated in patients with diaphragmatic hernia. • Intermittent positive pressure ventilation should be performed, and high inspiratory pressures should be avoided to help prevent reexpansion pulmonary edema. • Drugs such as methylprednisolone may be beneficial for preventing reexpansion pulmonary edema in animals with chronic diaphragmatic hernia.

Anesthesia • Chamber or mask induction should be avoided. • Supplementing oxygen before induction improves myocardial oxygenation. • Drugs with minimal respiratory depressant effects. • Injectable anesthetics allowing rapid intubation are preferred. • Inhalation anesthetics should be used for maintenance of anesthesia. • The lungs should be allowed to expand slowly after surgery. • Nitrous oxide is contraindicated in patients with diaphragmatic hernia. • Intermittent positive pressure ventilation should be performed, and high inspiratory pressures should be avoided to help prevent reexpansion pulmonary edema. • Drugs such as methylprednisolone may be beneficial for preventing reexpansion pulmonary edema in animals with chronic diaphragmatic hernia.

Surgical Technique • Make a ventral midline abdominal incision. If greater exposure is needed, extend the incision cranially through the sternum. • Enlarge the diaphragmatic defect if necessary and replace the abdominal organs in the abdominal cavity. • If adhesions are present, gently dissect the tissues from the thoracic structures, resecting or debriding necrotic tissue as necessary. • Debride the edges of the defect and close in a simple continuous suture pattern. Do not close the pericardial sac. • Remove air from the pericardial sac or pleural cavity or both after closing the defect. • If continued pneumothorax or effusion is likely, place a chest tube. Repair concomitant sternal or abdominal wall defects.

Surgical Technique • Make a ventral midline abdominal incision. If greater exposure is needed, extend the incision cranially through the sternum. • Enlarge the diaphragmatic defect if necessary and replace the abdominal organs in the abdominal cavity. • If adhesions are present, gently dissect the tissues from the thoracic structures, resecting or debriding necrotic tissue as necessary. • Debride the edges of the defect and close in a simple continuous suture pattern. Do not close the pericardial sac. • Remove air from the pericardial sac or pleural cavity or both after closing the defect. • If continued pneumothorax or effusion is likely, place a chest tube. Repair concomitant sternal or abdominal wall defects.

Thank You

Thank You