0886d27be850756ca19ba8e374885d14.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 30

Developmental Prosopagnosia:

Developmental Prosopagnosia:

Developmental prosopagnosia: Face recognition impairment without any apparent deficits in vision, intelligence or social functioning, and in the absence of any obvious brain injury. Prevalence of about 2. 5% in Caucasian and Hong Kong Chinese (Kennerknecht et al, 2006, 2008).

Developmental prosopagnosia: Face recognition impairment without any apparent deficits in vision, intelligence or social functioning, and in the absence of any obvious brain injury. Prevalence of about 2. 5% in Caucasian and Hong Kong Chinese (Kennerknecht et al, 2006, 2008).

Face-specificity of developmental prosopagnosia: Mixed group. Some DPs are also agnosic for other within-class discriminations (e. g. specific cars, horses: retain basic-level recognition). Some DPs have deficits with recognition and other types of face processing (e. g. emotion or gender discrimination, Ariel and Sadeh 1996). Duchaine et al (2006): 1/3 have navigational difficulties, 1/5 have speech-reading problems in noisy environments. Some DPs have deficits confined to face recognition.

Face-specificity of developmental prosopagnosia: Mixed group. Some DPs are also agnosic for other within-class discriminations (e. g. specific cars, horses: retain basic-level recognition). Some DPs have deficits with recognition and other types of face processing (e. g. emotion or gender discrimination, Ariel and Sadeh 1996). Duchaine et al (2006): 1/3 have navigational difficulties, 1/5 have speech-reading problems in noisy environments. Some DPs have deficits confined to face recognition.

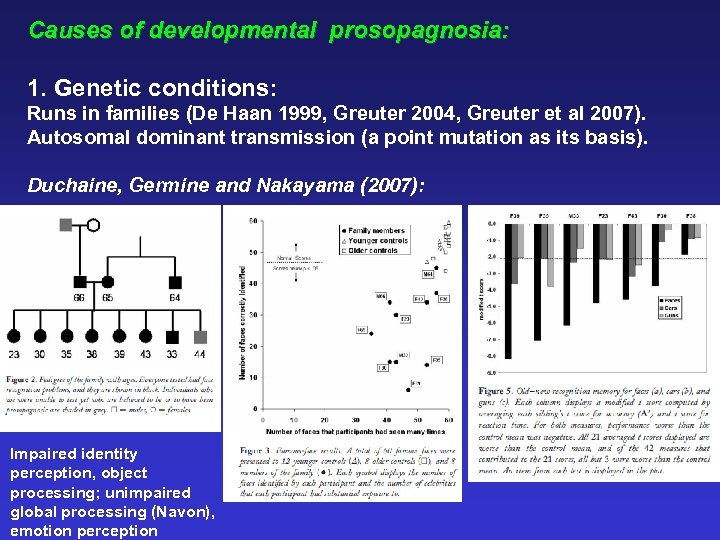

Causes of developmental prosopagnosia: 1. Genetic conditions: Runs in families (De Haan 1999, Greuter 2004, Greuter et al 2007). Autosomal dominant transmission (a point mutation as its basis). Duchaine, Germine and Nakayama (2007): Impaired identity perception, object processing; unimpaired global processing (Navon), emotion perception

Causes of developmental prosopagnosia: 1. Genetic conditions: Runs in families (De Haan 1999, Greuter 2004, Greuter et al 2007). Autosomal dominant transmission (a point mutation as its basis). Duchaine, Germine and Nakayama (2007): Impaired identity perception, object processing; unimpaired global processing (Navon), emotion perception

Causes of developmental prosopagnosia: 2. Early visual problems: e. g. severe myopia or cataracts (Le Grand et al 2001; Le Grand, Mondloch, Maurer and Brent 2003). 3. Early brain damage?

Causes of developmental prosopagnosia: 2. Early visual problems: e. g. severe myopia or cataracts (Le Grand et al 2001; Le Grand, Mondloch, Maurer and Brent 2003). 3. Early brain damage?

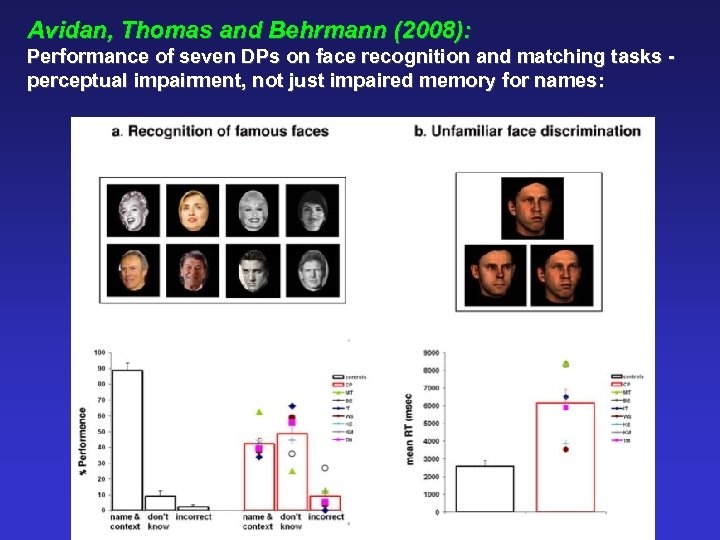

Avidan, Thomas and Behrmann (2008): Performance of seven DPs on face recognition and matching tasks perceptual impairment, not just impaired memory for names:

Avidan, Thomas and Behrmann (2008): Performance of seven DPs on face recognition and matching tasks perceptual impairment, not just impaired memory for names:

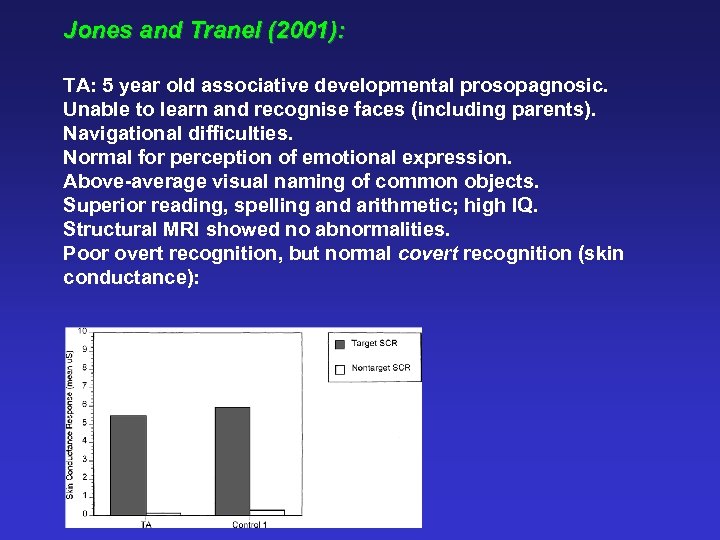

Jones and Tranel (2001): TA: 5 year old associative developmental prosopagnosic. Unable to learn and recognise faces (including parents). Navigational difficulties. Normal for perception of emotional expression. Above-average visual naming of common objects. Superior reading, spelling and arithmetic; high IQ. Structural MRI showed no abnormalities. Poor overt recognition, but normal covert recognition (skin conductance):

Jones and Tranel (2001): TA: 5 year old associative developmental prosopagnosic. Unable to learn and recognise faces (including parents). Navigational difficulties. Normal for perception of emotional expression. Above-average visual naming of common objects. Superior reading, spelling and arithmetic; high IQ. Structural MRI showed no abnormalities. Poor overt recognition, but normal covert recognition (skin conductance):

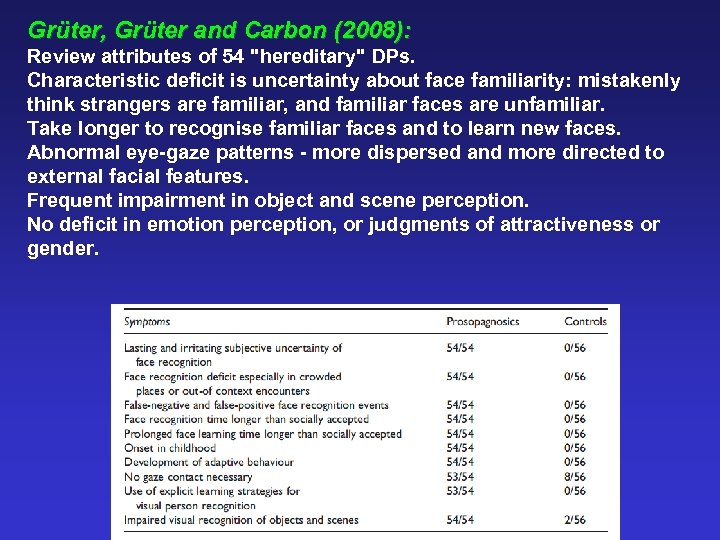

Grüter, Grüter and Carbon (2008): Review attributes of 54 "hereditary" DPs. Characteristic deficit is uncertainty about face familiarity: mistakenly think strangers are familiar, and familiar faces are unfamiliar. Take longer to recognise familiar faces and to learn new faces. Abnormal eye-gaze patterns - more dispersed and more directed to external facial features. Frequent impairment in object and scene perception. No deficit in emotion perception, or judgments of attractiveness or gender.

Grüter, Grüter and Carbon (2008): Review attributes of 54 "hereditary" DPs. Characteristic deficit is uncertainty about face familiarity: mistakenly think strangers are familiar, and familiar faces are unfamiliar. Take longer to recognise familiar faces and to learn new faces. Abnormal eye-gaze patterns - more dispersed and more directed to external facial features. Frequent impairment in object and scene perception. No deficit in emotion perception, or judgments of attractiveness or gender.

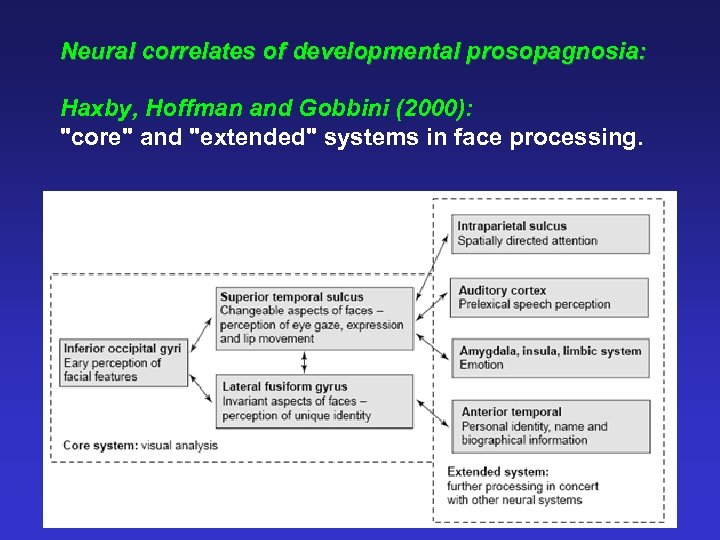

Neural correlates of developmental prosopagnosia: Haxby, Hoffman and Gobbini (2000): "core" and "extended" systems in face processing.

Neural correlates of developmental prosopagnosia: Haxby, Hoffman and Gobbini (2000): "core" and "extended" systems in face processing.

Normal participants: (a) greater activity in core regions for faces than for non-face objects. (b) core regions show repetition suppression attenuated activity in response to repeated facial information. - fusiform gyrus shows attenuation in response to identity repetition. - superior temporal sulcus shows attentuation in response to expression repetition.

Normal participants: (a) greater activity in core regions for faces than for non-face objects. (b) core regions show repetition suppression attenuated activity in response to repeated facial information. - fusiform gyrus shows attenuation in response to identity repetition. - superior temporal sulcus shows attentuation in response to expression repetition.

Developmental prosopagnosics: f. MRI studies equivocal - many (but not all) show apparently-normal fusiform gyrus activity in DPs (Avidan et al 2008). Furl et al (2011): Suggest continua both of impairment and FG activity, not an absolute deficit. 15 DPs and 15 normals. As a group, DPs had reduced face-selective responses in bilateral FFA compared to non-DPs. Individual DPs also more likely than normals to lack expected face-selective activity in core regions.

Developmental prosopagnosics: f. MRI studies equivocal - many (but not all) show apparently-normal fusiform gyrus activity in DPs (Avidan et al 2008). Furl et al (2011): Suggest continua both of impairment and FG activity, not an absolute deficit. 15 DPs and 15 normals. As a group, DPs had reduced face-selective responses in bilateral FFA compared to non-DPs. Individual DPs also more likely than normals to lack expected face-selective activity in core regions.

Avidan, Hasson, Malach and Behrmann (2005): DPs show unimpaired RH functioning, but reduced LH activity in response to faces (especially in FG). Avidan and Behrmann (2007): Normal repetition-habituation effects in FFA of DP individuals. Dobel et al (2008): DPs show reduced M 170, especially over LH.

Avidan, Hasson, Malach and Behrmann (2005): DPs show unimpaired RH functioning, but reduced LH activity in response to faces (especially in FG). Avidan and Behrmann (2007): Normal repetition-habituation effects in FFA of DP individuals. Dobel et al (2008): DPs show reduced M 170, especially over LH.

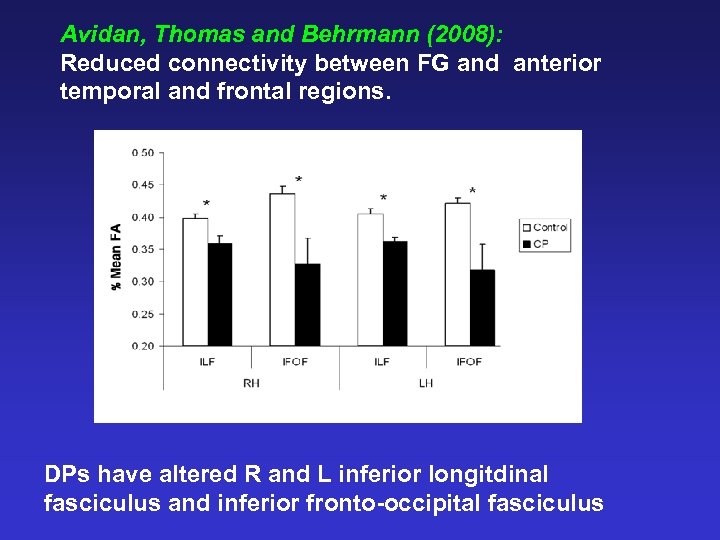

Avidan, Thomas and Behrmann (2008): Reduced connectivity between FG and anterior temporal and frontal regions. DPs have altered R and L inferior longitdinal fasciculus and inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus

Avidan, Thomas and Behrmann (2008): Reduced connectivity between FG and anterior temporal and frontal regions. DPs have altered R and L inferior longitdinal fasciculus and inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus

PT - a developmental prosopagnosic: Retired schoolteacher - 55 year old right-handed male. University educated - OU Physics Tutor, with degree in Zoology and Biology. WAIS- III IQ 142, Verbal IQ 135, Performance IQ 140. Initially presented after an incident concerning students whom he couldn’t identify at school; has subsequently had to take early retirement. Normal in everyday activities, housework, cooking etc. CT scan revealed no obvious abnormalties.

PT - a developmental prosopagnosic: Retired schoolteacher - 55 year old right-handed male. University educated - OU Physics Tutor, with degree in Zoology and Biology. WAIS- III IQ 142, Verbal IQ 135, Performance IQ 140. Initially presented after an incident concerning students whom he couldn’t identify at school; has subsequently had to take early retirement. Normal in everyday activities, housework, cooking etc. CT scan revealed no obvious abnormalties.

Summary of testing with PT: Good at object naming, object semantics and object decision. Normal at matching unfamiliar faces. Poor at emotional judgements of faces. Poor at familiarity judgements of faces. Poor at face naming; better at naming other withincategory objects (e. g. flowers).

Summary of testing with PT: Good at object naming, object semantics and object decision. Normal at matching unfamiliar faces. Poor at emotional judgements of faces. Poor at familiarity judgements of faces. Poor at face naming; better at naming other withincategory objects (e. g. flowers).

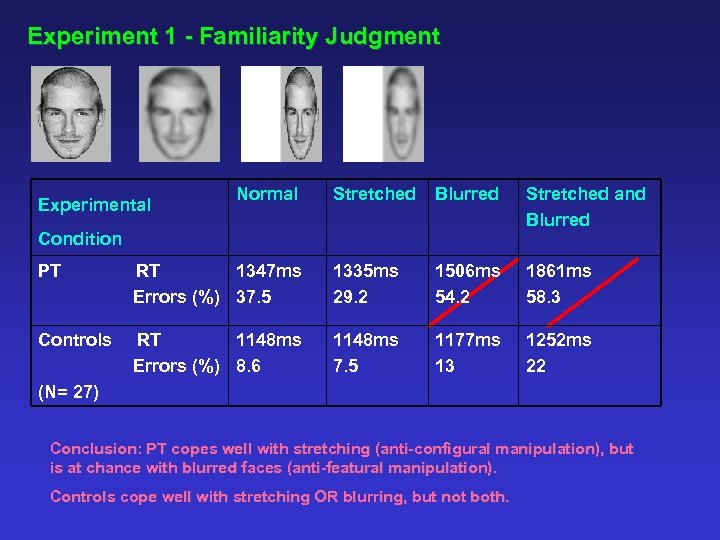

Experiment 1 - Familiarity Judgment Experimental Normal Stretched Blurred Stretched and Blurred Condition PT RT 1347 ms Errors (%) 37. 5 1335 ms 29. 2 1506 ms 54. 2 1861 ms 58. 3 Controls RT 1148 ms Errors (%) 8. 6 1148 ms 7. 5 1177 ms 13 1252 ms 22 (N= 27) Conclusion: PT copes well with stretching (anti-configural manipulation), but is at chance with blurred faces (anti-featural manipulation). Controls cope well with stretching OR blurring, but not both.

Experiment 1 - Familiarity Judgment Experimental Normal Stretched Blurred Stretched and Blurred Condition PT RT 1347 ms Errors (%) 37. 5 1335 ms 29. 2 1506 ms 54. 2 1861 ms 58. 3 Controls RT 1148 ms Errors (%) 8. 6 1148 ms 7. 5 1177 ms 13 1252 ms 22 (N= 27) Conclusion: PT copes well with stretching (anti-configural manipulation), but is at chance with blurred faces (anti-featural manipulation). Controls cope well with stretching OR blurring, but not both.

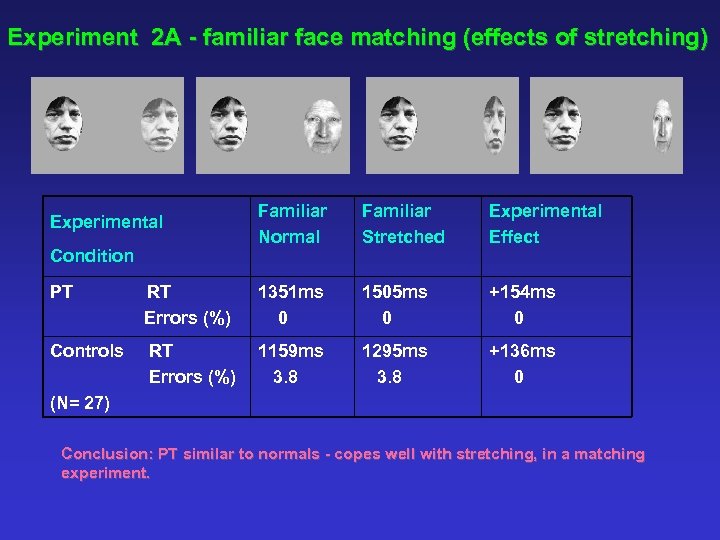

Experiment 2 A - familiar face matching (effects of stretching) Experimental Condition Familiar Normal Familiar Stretched Experimental Effect PT RT Errors (%) 1351 ms 0 1505 ms 0 +154 ms 0 Controls RT Errors (%) 1159 ms 3. 8 1295 ms 3. 8 +136 ms 0 (N= 27) Conclusion: PT similar to normals - copes well with stretching, in a matching experiment.

Experiment 2 A - familiar face matching (effects of stretching) Experimental Condition Familiar Normal Familiar Stretched Experimental Effect PT RT Errors (%) 1351 ms 0 1505 ms 0 +154 ms 0 Controls RT Errors (%) 1159 ms 3. 8 1295 ms 3. 8 +136 ms 0 (N= 27) Conclusion: PT similar to normals - copes well with stretching, in a matching experiment.

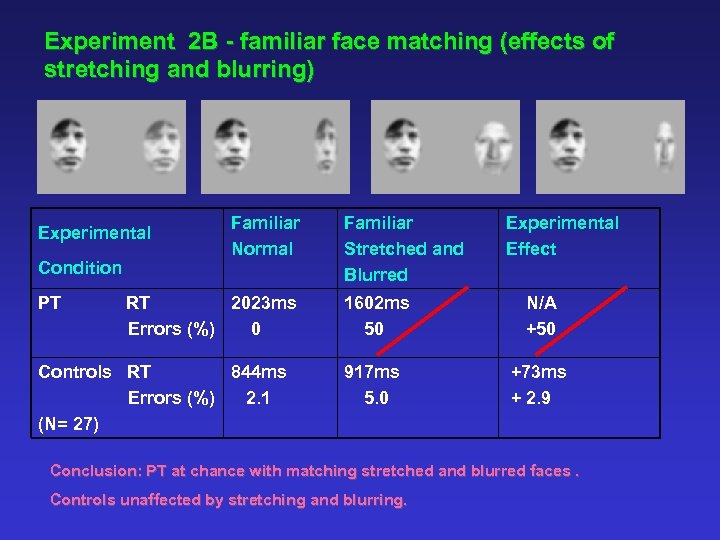

Experiment 2 B - familiar face matching (effects of stretching and blurring) Experimental Condition PT Familiar Normal RT 2023 ms Errors (%) 0 Controls RT 844 ms Errors (%) 2. 1 (N= 27) Familiar Stretched and Blurred Experimental Effect 1602 ms 50 N/A +50 917 ms 5. 0 +73 ms + 2. 9 Conclusion: PT at chance with matching stretched and blurred faces. Controls unaffected by stretching and blurring.

Experiment 2 B - familiar face matching (effects of stretching and blurring) Experimental Condition PT Familiar Normal RT 2023 ms Errors (%) 0 Controls RT 844 ms Errors (%) 2. 1 (N= 27) Familiar Stretched and Blurred Experimental Effect 1602 ms 50 N/A +50 917 ms 5. 0 +73 ms + 2. 9 Conclusion: PT at chance with matching stretched and blurred faces. Controls unaffected by stretching and blurring.

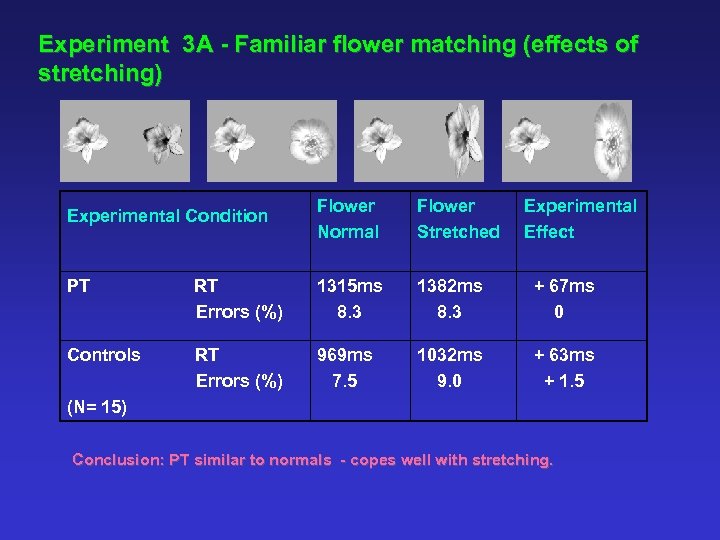

Experiment 3 A - Familiar flower matching (effects of stretching) Experimental Condition Flower Normal Flower Stretched Experimental Effect PT RT Errors (%) 1315 ms 8. 3 1382 ms 8. 3 + 67 ms 0 Controls RT Errors (%) 969 ms 7. 5 1032 ms 9. 0 + 63 ms + 1. 5 (N= 15) Conclusion: PT similar to normals - copes well with stretching.

Experiment 3 A - Familiar flower matching (effects of stretching) Experimental Condition Flower Normal Flower Stretched Experimental Effect PT RT Errors (%) 1315 ms 8. 3 1382 ms 8. 3 + 67 ms 0 Controls RT Errors (%) 969 ms 7. 5 1032 ms 9. 0 + 63 ms + 1. 5 (N= 15) Conclusion: PT similar to normals - copes well with stretching.

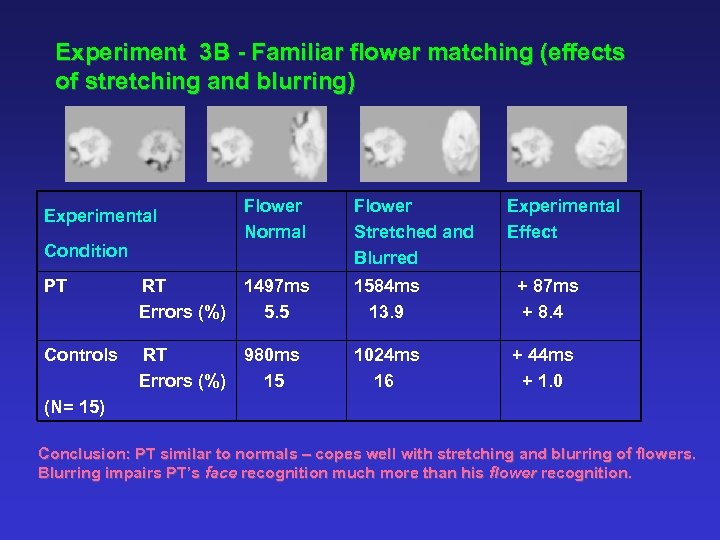

Experiment 3 B - Familiar flower matching (effects of stretching and blurring) Experimental Condition Flower Normal Flower Stretched and Blurred Experimental Effect PT RT Errors (%) 1497 ms 5. 5 1584 ms 13. 9 + 87 ms + 8. 4 Controls RT Errors (%) 980 ms 15 1024 ms 16 + 44 ms + 1. 0 (N= 15) Conclusion: PT similar to normals – copes well with stretching and blurring of flowers. Blurring impairs PT’s face recognition much more than his flower recognition.

Experiment 3 B - Familiar flower matching (effects of stretching and blurring) Experimental Condition Flower Normal Flower Stretched and Blurred Experimental Effect PT RT Errors (%) 1497 ms 5. 5 1584 ms 13. 9 + 87 ms + 8. 4 Controls RT Errors (%) 980 ms 15 1024 ms 16 + 44 ms + 1. 0 (N= 15) Conclusion: PT similar to normals – copes well with stretching and blurring of flowers. Blurring impairs PT’s face recognition much more than his flower recognition.

Conclusions: PT has a problem with configural processing - blurring impairs performance by preventing use of featural details. May be face-specific; he can process configural information from flowers (so not a generalised problem within-class discriminations). Other prosopagnosics exist who appear to have a specific deficit in configural processing (but not necessarily face-specific). . .

Conclusions: PT has a problem with configural processing - blurring impairs performance by preventing use of featural details. May be face-specific; he can process configural information from flowers (so not a generalised problem within-class discriminations). Other prosopagnosics exist who appear to have a specific deficit in configural processing (but not necessarily face-specific). . .

Duchaine, Yovel, Butterworth and Nakayama (2006): Edward: Lifelong face recognition difficulties. Also problems with expression perception. No navigational difficulties. No face-selective M 170. No inversion effect (unlike normals). Normal contrast sensitivity, BORB and naming of line drawings.

Duchaine, Yovel, Butterworth and Nakayama (2006): Edward: Lifelong face recognition difficulties. Also problems with expression perception. No navigational difficulties. No face-selective M 170. No inversion effect (unlike normals). Normal contrast sensitivity, BORB and naming of line drawings.

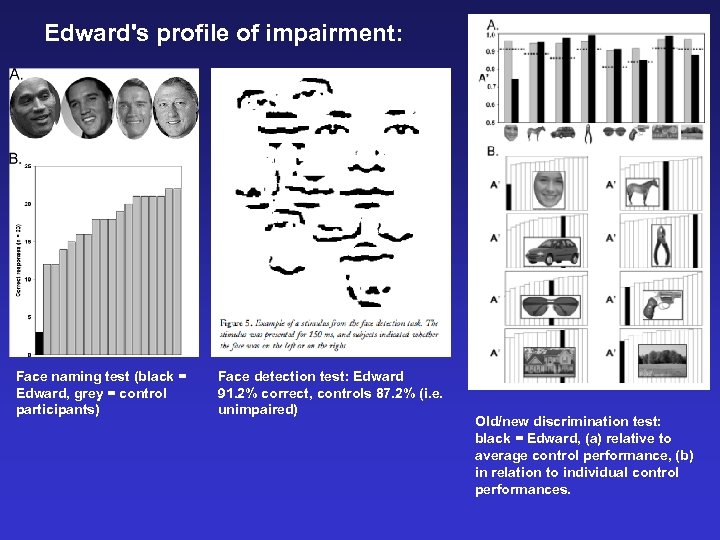

Edward's profile of impairment: Face naming test (black = Edward, grey = control participants) Face detection test: Edward 91. 2% correct, controls 87. 2% (i. e. unimpaired) Old/new discrimination test: black = Edward, (a) relative to average control performance, (b) in relation to individual control performances.

Edward's profile of impairment: Face naming test (black = Edward, grey = control participants) Face detection test: Edward 91. 2% correct, controls 87. 2% (i. e. unimpaired) Old/new discrimination test: black = Edward, (a) relative to average control performance, (b) in relation to individual control performances.

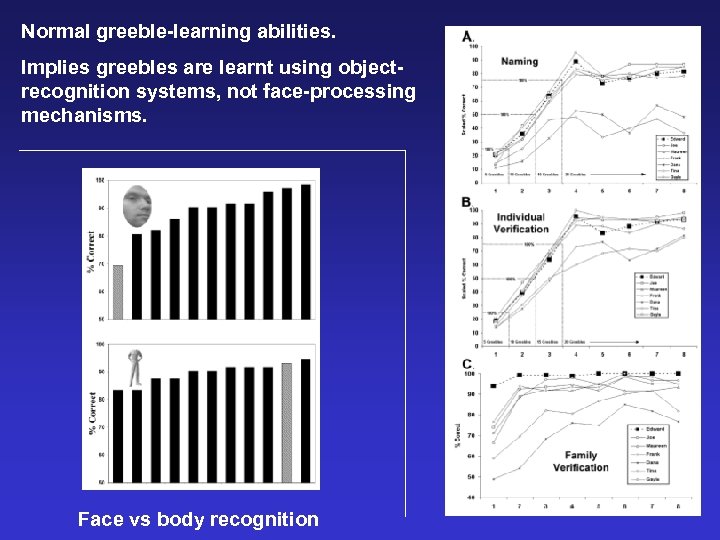

Normal greeble-learning abilities. Implies greebles are learnt using objectrecognition systems, not face-processing mechanisms. Face vs body recognition

Normal greeble-learning abilities. Implies greebles are learnt using objectrecognition systems, not face-processing mechanisms. Face vs body recognition

Edward's profile of impairment and its implications: Fairly specific problems with face recognition and emotion recognition. Normal-range performance with inverted faces and headless bodies shows he has no problems with low-level pattern recognition (e. g. curvature discrimination) or within-class discrimination generally. Normal second-order configural processing for houses but not faces - so no general configural deficit. Deficit apparently at the structural encoding stage of face processing. Duchaine et al suggest Edward failed to develop a face-specific processing mechanism; this did not affect other objectrecognition systems.

Edward's profile of impairment and its implications: Fairly specific problems with face recognition and emotion recognition. Normal-range performance with inverted faces and headless bodies shows he has no problems with low-level pattern recognition (e. g. curvature discrimination) or within-class discrimination generally. Normal second-order configural processing for houses but not faces - so no general configural deficit. Deficit apparently at the structural encoding stage of face processing. Duchaine et al suggest Edward failed to develop a face-specific processing mechanism; this did not affect other objectrecognition systems.

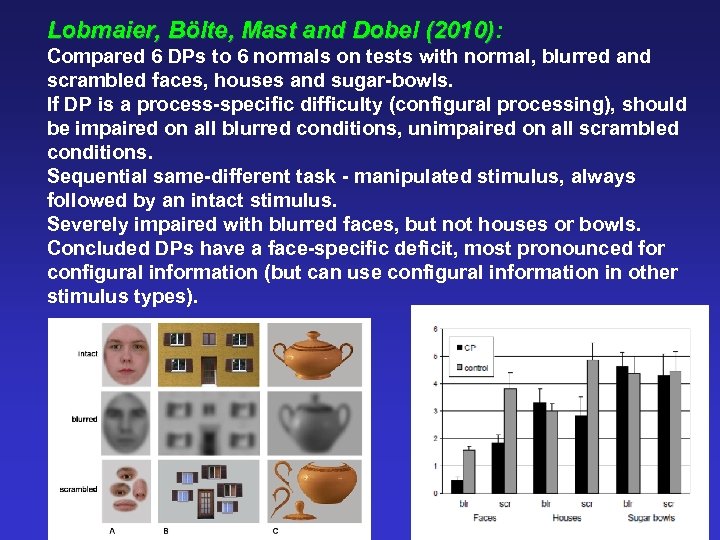

Lobmaier, Bölte, Mast and Dobel (2010): (2010) Compared 6 DPs to 6 normals on tests with normal, blurred and scrambled faces, houses and sugar-bowls. If DP is a process-specific difficulty (configural processing), should be impaired on all blurred conditions, unimpaired on all scrambled conditions. Sequential same-different task - manipulated stimulus, always followed by an intact stimulus. Severely impaired with blurred faces, but not houses or bowls. Concluded DPs have a face-specific deficit, most pronounced for configural information (but can use configural information in other stimulus types).

Lobmaier, Bölte, Mast and Dobel (2010): (2010) Compared 6 DPs to 6 normals on tests with normal, blurred and scrambled faces, houses and sugar-bowls. If DP is a process-specific difficulty (configural processing), should be impaired on all blurred conditions, unimpaired on all scrambled conditions. Sequential same-different task - manipulated stimulus, always followed by an intact stimulus. Severely impaired with blurred faces, but not houses or bowls. Concluded DPs have a face-specific deficit, most pronounced for configural information (but can use configural information in other stimulus types).

Face-specificity of developmental prosopagnosia: Germine , Cashdollar, Düzel and Duchaine (2011): A. W. : 19 -year old female, discovered by web-based screening. Developmental associative agnosic - not prosopagnosic. Selectively impaired for remembering guns, horses, scenes, tools, doors, and cars. Normal on 7 tests of face recognition, plus memory for houses and spectacles. Normal at matching visual shapes (faces, bodies, objects - i. e. has a memory deficit, not a perceptual deficit). Structural MRI revealed no abnormalties; no familial history. Implies development of face recognition and object recognition are separate processes normal face recognition can develop even if object recognition is impaired.

Face-specificity of developmental prosopagnosia: Germine , Cashdollar, Düzel and Duchaine (2011): A. W. : 19 -year old female, discovered by web-based screening. Developmental associative agnosic - not prosopagnosic. Selectively impaired for remembering guns, horses, scenes, tools, doors, and cars. Normal on 7 tests of face recognition, plus memory for houses and spectacles. Normal at matching visual shapes (faces, bodies, objects - i. e. has a memory deficit, not a perceptual deficit). Structural MRI revealed no abnormalties; no familial history. Implies development of face recognition and object recognition are separate processes normal face recognition can develop even if object recognition is impaired.

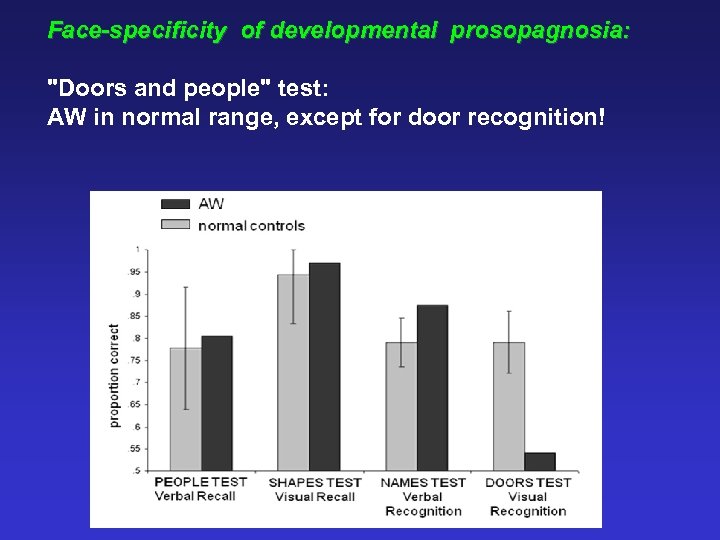

Face-specificity of developmental prosopagnosia: "Doors and people" test: AW in normal range, except for door recognition!

Face-specificity of developmental prosopagnosia: "Doors and people" test: AW in normal range, except for door recognition!

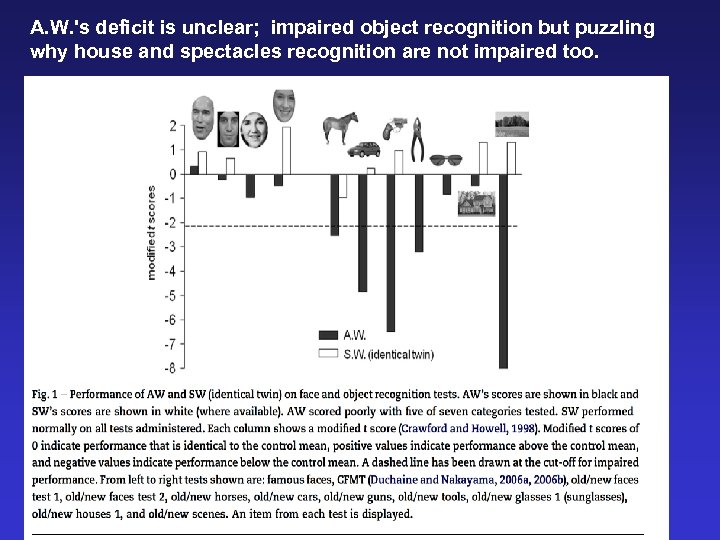

A. W. 's deficit is unclear; impaired object recognition but puzzling why house and spectacles recognition are not impaired too.

A. W. 's deficit is unclear; impaired object recognition but puzzling why house and spectacles recognition are not impaired too.

Conclusions: DP is evidence for the domain specificity of face recognition. Suggests face recognition is produced by mechanisms that are largely uninvolved in the development of other visual recognition systems (otherwise DPs would be agnosic too). Specific developmental disorders (DP, dyslexia, dyscalculia) imply that other, unrelated systems can develop normally. Specificity of DP impairment, in absence of brain damage, provides useful opportunities to investigate neural substrate of face processing. FFA is necessary but not sufficient for normal face processing. Heterogeneous group: some appear to have configural processing deficits, others a more associative deficit.

Conclusions: DP is evidence for the domain specificity of face recognition. Suggests face recognition is produced by mechanisms that are largely uninvolved in the development of other visual recognition systems (otherwise DPs would be agnosic too). Specific developmental disorders (DP, dyslexia, dyscalculia) imply that other, unrelated systems can develop normally. Specificity of DP impairment, in absence of brain damage, provides useful opportunities to investigate neural substrate of face processing. FFA is necessary but not sufficient for normal face processing. Heterogeneous group: some appear to have configural processing deficits, others a more associative deficit.