e2990f30214f9952405c03a24b565d71.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 83

Designing Social Protection Frameworks for Somalia: Findings and Ways Forward in SCS Gabrielle Smith 29 th September 2014

Designing Social Protection Frameworks for Somalia: Findings and Ways Forward in SCS Gabrielle Smith 29 th September 2014

SESSION 3: FINDINGS OF THE STUDY 2

SESSION 3: FINDINGS OF THE STUDY 2

1. Activities and Methods 2. Macro Level Context 3. Vulnerability Analysis 4. Mapping of Social Protection 5. Enabling Environment 3

1. Activities and Methods 2. Macro Level Context 3. Vulnerability Analysis 4. Mapping of Social Protection 5. Enabling Environment 3

1. Activities and Methods 6

1. Activities and Methods 6

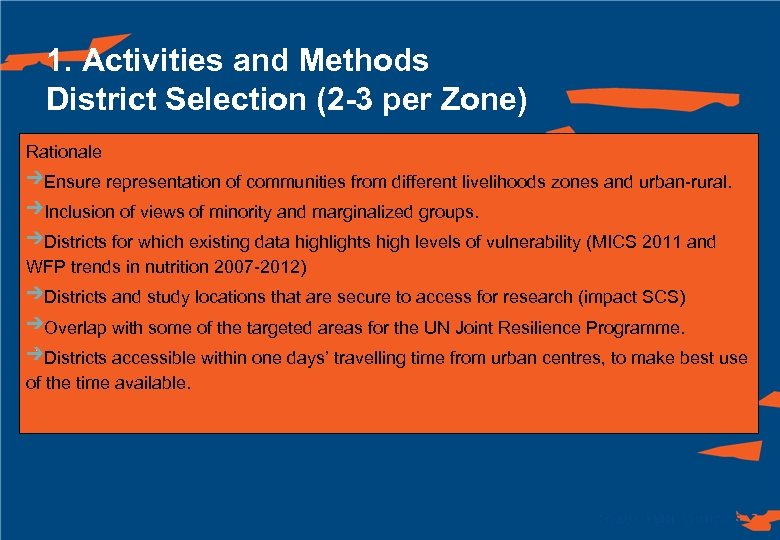

1. Activities and Methods District Selection (2 -3 per Zone) Rationale Ensure representation of communities from different livelihoods zones and urban-rural. Inclusion of views of minority and marginalized groups. Districts for which existing data highlights high levels of vulnerability (MICS 2011 and WFP trends in nutrition 2007 -2012) Districts and study locations that are secure to access for research (impact SCS) Overlap with some of the targeted areas for the UN Joint Resilience Programme. Districts accessible within one days’ travelling time from urban centres, to make best use of the time available. 7

1. Activities and Methods District Selection (2 -3 per Zone) Rationale Ensure representation of communities from different livelihoods zones and urban-rural. Inclusion of views of minority and marginalized groups. Districts for which existing data highlights high levels of vulnerability (MICS 2011 and WFP trends in nutrition 2007 -2012) Districts and study locations that are secure to access for research (impact SCS) Overlap with some of the targeted areas for the UN Joint Resilience Programme. Districts accessible within one days’ travelling time from urban centres, to make best use of the time available. 7

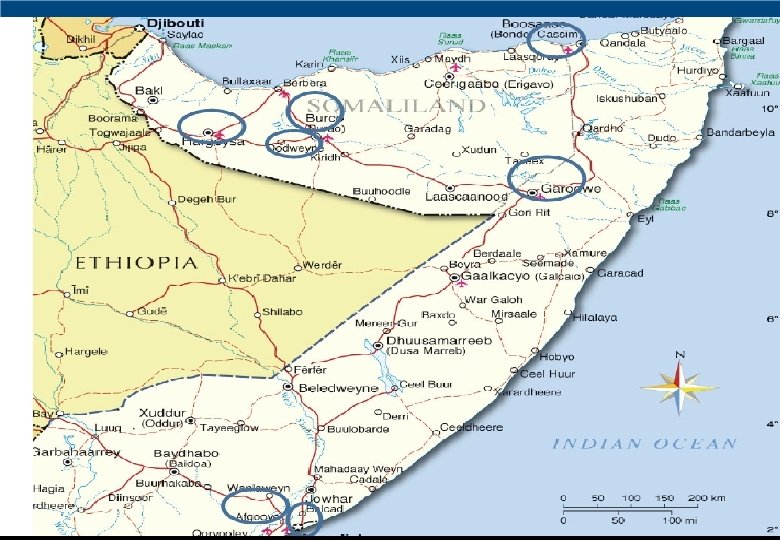

Study Sites Somaliland 8

Study Sites Somaliland 8

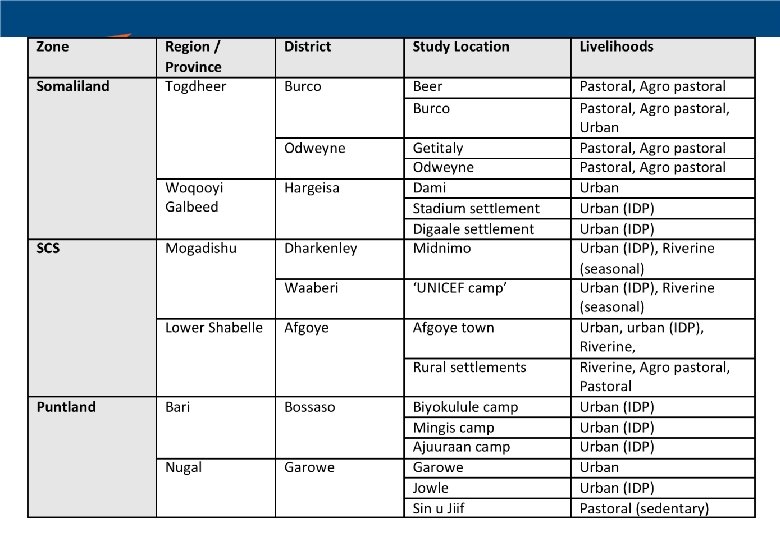

Study Sites 9

Study Sites 9

1. Activities and Methods Qualitative Research Activities 1. Literature Review: relevant secondary data, to inform the study approach. Underpinned by the team’s extensive knowledge of social protection schemes internationally. => conceptual framework and parameters of the study 1. Vulnerability Analysis: qualitative data collected from community members and key informants, triangulated with secondary data sources, to identify key drivers of inequality and vulnerability in each Zone and the factors that affect this. Including participation of vulnerable groups - children, women, the elderly, the disabled, IDP and pastoral communities and minority clans. 2. Mapping of Social Protection and the Enabling Environment: mapping existing social protection and safety net related initiatives, institutions and structures at national, sub-national and community level; and the current policy, institutional and regulatory framework. 10

1. Activities and Methods Qualitative Research Activities 1. Literature Review: relevant secondary data, to inform the study approach. Underpinned by the team’s extensive knowledge of social protection schemes internationally. => conceptual framework and parameters of the study 1. Vulnerability Analysis: qualitative data collected from community members and key informants, triangulated with secondary data sources, to identify key drivers of inequality and vulnerability in each Zone and the factors that affect this. Including participation of vulnerable groups - children, women, the elderly, the disabled, IDP and pastoral communities and minority clans. 2. Mapping of Social Protection and the Enabling Environment: mapping existing social protection and safety net related initiatives, institutions and structures at national, sub-national and community level; and the current policy, institutional and regulatory framework. 10

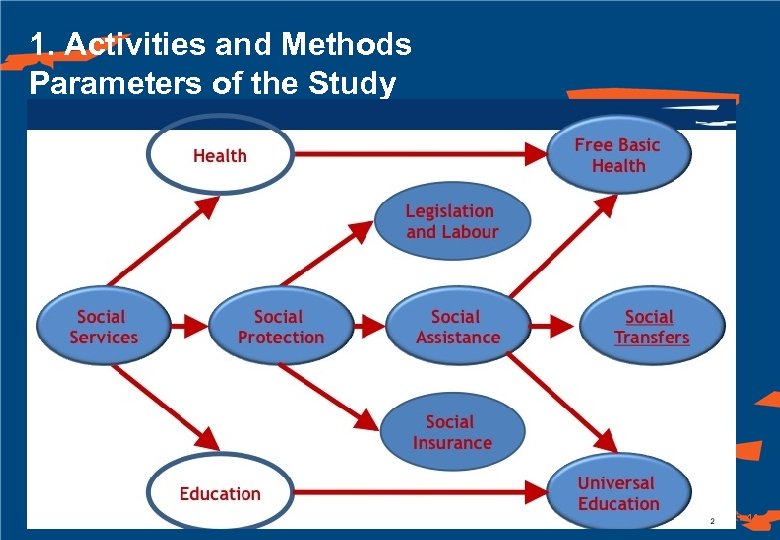

1. Activities and Methods Parameters of the Study 11

1. Activities and Methods Parameters of the Study 11

1. Activities and Methods Focus on Social Transfers (CTs) 1. cash based social transfers are at the core of any social protection 2. 3. 4. policy framework and are one of the foundation building blocks in LICs Given issues of capacity, important to limit scope in the short to medium term Cash transfers proven to be feasible and appropriate in this context Huge amount of evidence that well designed CTs can contribute to all the functions of social protection (protect consumption; prevent fall further into poverty; promote investments in human development, assets and the labour market for more productive livelihoods and transform relations in society – tool for poverty, reduction, resilience building and multidimensional wellbeing. 12

1. Activities and Methods Focus on Social Transfers (CTs) 1. cash based social transfers are at the core of any social protection 2. 3. 4. policy framework and are one of the foundation building blocks in LICs Given issues of capacity, important to limit scope in the short to medium term Cash transfers proven to be feasible and appropriate in this context Huge amount of evidence that well designed CTs can contribute to all the functions of social protection (protect consumption; prevent fall further into poverty; promote investments in human development, assets and the labour market for more productive livelihoods and transform relations in society – tool for poverty, reduction, resilience building and multidimensional wellbeing. 12

1. Activities and Methods Research Instruments Qualitative research: group and one-on-one discussions with communities and particular demographic groups 1. 2. 3. 4. Community Mapping Focus group discussions Life History interviews Key Informant Interviews Visual aids (timelines of community events and lifecycle events, seasonal calendars) Participants FGD/LHI • Older people 50+ (m/f) • Adults of working age 25 -50 (m/f) • Young people 18 -25 (m/f) • People with disabilities • School age children 10 -14 • Minority groups (Gabooye) (m/f) Key Informants • District level government • Community/religious leaders • Local service providers and CBOs • Development Partners • Central Government • Financial service providers • INGOs 15

1. Activities and Methods Research Instruments Qualitative research: group and one-on-one discussions with communities and particular demographic groups 1. 2. 3. 4. Community Mapping Focus group discussions Life History interviews Key Informant Interviews Visual aids (timelines of community events and lifecycle events, seasonal calendars) Participants FGD/LHI • Older people 50+ (m/f) • Adults of working age 25 -50 (m/f) • Young people 18 -25 (m/f) • People with disabilities • School age children 10 -14 • Minority groups (Gabooye) (m/f) Key Informants • District level government • Community/religious leaders • Local service providers and CBOs • Development Partners • Central Government • Financial service providers • INGOs 15

2. Macro level context 18

2. Macro level context 18

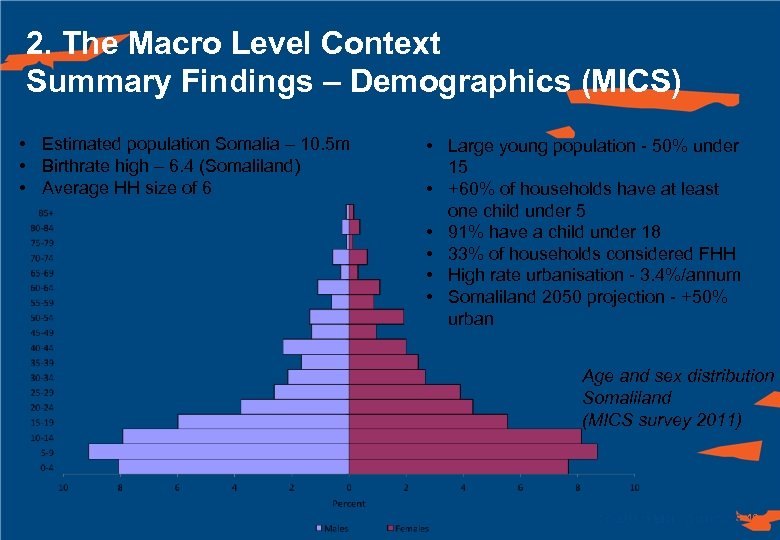

2. The Macro Level Context Summary Findings – Demographics (MICS) • Estimated population Somalia – 10. 5 m • Birthrate high – 6. 4 (Somaliland) • Average HH size of 6 • Large young population - 50% under 15 • +60% of households have at least one child under 5 • 91% have a child under 18 • 33% of households considered FHH • High rate urbanisation - 3. 4%/annum • Somaliland 2050 projection - +50% urban Age and sex distribution Somaliland (MICS survey 2011) 19

2. The Macro Level Context Summary Findings – Demographics (MICS) • Estimated population Somalia – 10. 5 m • Birthrate high – 6. 4 (Somaliland) • Average HH size of 6 • Large young population - 50% under 15 • +60% of households have at least one child under 5 • 91% have a child under 18 • 33% of households considered FHH • High rate urbanisation - 3. 4%/annum • Somaliland 2050 projection - +50% urban Age and sex distribution Somaliland (MICS survey 2011) 19

2. The Macro Level Context Socio-economic Summary GDP per capita $347 (2012), 4 th lowest in the world. Chronic unemployment - way above SSA average. Strong markets are a critical support facilitating movement of people, money and goods. $1. 3 bn in remittances is transferred annually however not equitably received HH survey for Somaliland (2013) estimated poverty in urban areas at 29% (v Ethiopia 26%) and rural poverty is 38% (v Ethiopia 30%). Excludes urban IDPs and nomadic communities. Therefore these are likely to be underestimates. Income inequality much higher than Ethiopia (Gini) HDIs for women and children much lower than neighbouring countries (education, health, access to services). Many correlate with poverty; generally worse in rural areas Child and maternal under-nutrition in acute and chronic forms are an enduring problem. The majority of HH food is purchased, even in rural areas – access a major challenge. Prone to droughts and floods - frequency and severity of climatic shocks is increasing. Insecurity on-going challenge in SCS 20

2. The Macro Level Context Socio-economic Summary GDP per capita $347 (2012), 4 th lowest in the world. Chronic unemployment - way above SSA average. Strong markets are a critical support facilitating movement of people, money and goods. $1. 3 bn in remittances is transferred annually however not equitably received HH survey for Somaliland (2013) estimated poverty in urban areas at 29% (v Ethiopia 26%) and rural poverty is 38% (v Ethiopia 30%). Excludes urban IDPs and nomadic communities. Therefore these are likely to be underestimates. Income inequality much higher than Ethiopia (Gini) HDIs for women and children much lower than neighbouring countries (education, health, access to services). Many correlate with poverty; generally worse in rural areas Child and maternal under-nutrition in acute and chronic forms are an enduring problem. The majority of HH food is purchased, even in rural areas – access a major challenge. Prone to droughts and floods - frequency and severity of climatic shocks is increasing. Insecurity on-going challenge in SCS 20

2. The Macro Level Context Key Conclusions for the Framework Poverty is multidimensional and has both social and economic characteristics. Women and children are particularly vulnerable; however others - elderly, disabled and youth - are also likely to be vulnerable but data for these groups does not exist. Data is lacking but the situation is likely to be worse in South Central Somalia given the overlying shocks and access constraints. There exist both chronic long-term and transient poverty and food insecurity. There are multiple challenges to be addressed, a number of which correlate with income insecurity and which it will be important to consider in the design of social protection programmes; however it is unlikely that a single programme or even programmes can address all needs simultaneously. 28

2. The Macro Level Context Key Conclusions for the Framework Poverty is multidimensional and has both social and economic characteristics. Women and children are particularly vulnerable; however others - elderly, disabled and youth - are also likely to be vulnerable but data for these groups does not exist. Data is lacking but the situation is likely to be worse in South Central Somalia given the overlying shocks and access constraints. There exist both chronic long-term and transient poverty and food insecurity. There are multiple challenges to be addressed, a number of which correlate with income insecurity and which it will be important to consider in the design of social protection programmes; however it is unlikely that a single programme or even programmes can address all needs simultaneously. 28

3. Vulnerability Analysis 29

3. Vulnerability Analysis 29

3. Vulnerability Analysis 1. Defining vulnerability 2. Trends in livelihoods and factors affecting vulnerability 3. Shocks and stresses 4. Coping strategies 5. Community analysis of vulnerability 30

3. Vulnerability Analysis 1. Defining vulnerability 2. Trends in livelihoods and factors affecting vulnerability 3. Shocks and stresses 4. Coping strategies 5. Community analysis of vulnerability 30

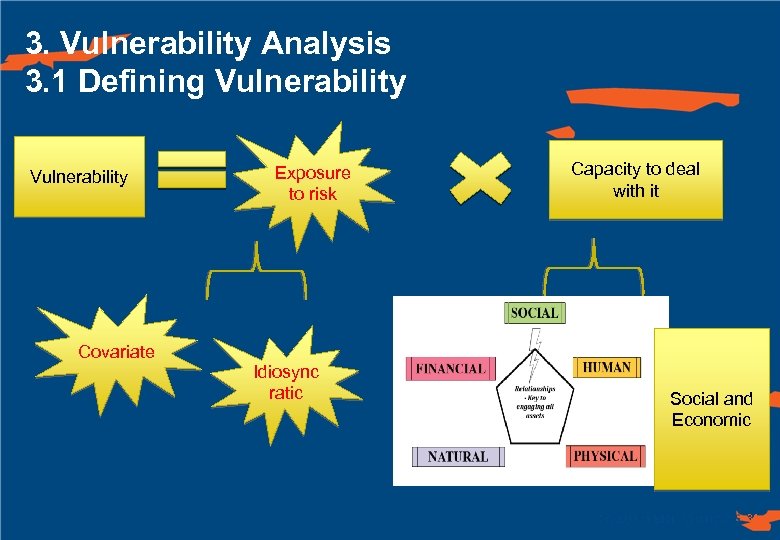

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 1 Defining Vulnerability Covariate Exposure to risk Idiosync ratic Capacity to deal with it Social and Economic 31

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 1 Defining Vulnerability Covariate Exposure to risk Idiosync ratic Capacity to deal with it Social and Economic 31

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Trends in Vulnerability of Livelihoods Main drivers contributing to vulnerability of livelihoods: Environmental shocks, conflict, poor governance, marginalization and chronic poverty Extensive economic hardship - vast majority of households in the study are low income. Collective purchasing power is low. Number of major trends in livelihoods were identified § Increasing poverty and vulnerability affecting livelihoods in rural areas, on account of recurring climatic shocks and other constraints to livelihoods such as lack of economic opportunity. § Increasing economic migration and rapid urbanisation. § In South Central Somalia a major additional constraint is recent conflict and insecurity - a driver behind the growth of the population in the camps visited. § Some improvements to services however these remain grossly inadequate and inaccessible to the majority in rural areas and to IDP and poor communities in urban areas. Vicious cycle: these trends are a consequence of the underlying drivers and also further contribute to these drivers to increase vulnerability of livelihoods Affecting different groups in different ways 32

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Trends in Vulnerability of Livelihoods Main drivers contributing to vulnerability of livelihoods: Environmental shocks, conflict, poor governance, marginalization and chronic poverty Extensive economic hardship - vast majority of households in the study are low income. Collective purchasing power is low. Number of major trends in livelihoods were identified § Increasing poverty and vulnerability affecting livelihoods in rural areas, on account of recurring climatic shocks and other constraints to livelihoods such as lack of economic opportunity. § Increasing economic migration and rapid urbanisation. § In South Central Somalia a major additional constraint is recent conflict and insecurity - a driver behind the growth of the population in the camps visited. § Some improvements to services however these remain grossly inadequate and inaccessible to the majority in rural areas and to IDP and poor communities in urban areas. Vicious cycle: these trends are a consequence of the underlying drivers and also further contribute to these drivers to increase vulnerability of livelihoods Affecting different groups in different ways 32

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Trends in Rural Livelihoods • Constraints to the founding principles of pastoralism that enable HH to deal with shock. § Reduction in herd sizes (livestock disease, recurrent droughts and general water scarcity, overgrazing and land use change) § Changes in herd composition – cattle all but vanished; some camels and – more often - small stock. § Access to rangeland is becoming constrained (land acquisition and fencing off of traditional communal grazing land for private use) => conflict • Chronic lack of alternative opportunities for productive livelihoods or employment. § Untapped potential of agriculture – little investment in agriculture - production low, with some considering that production over time has been declining. § Farming still water-dependent and exposed to the climatic trends mentioned above. Potentially more vulnerable since it is sedentary • Strong desire and attempts to diversify but limited options • Mainly peri-urban (teashops, trading, fodder production, Khat sale) 33

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Trends in Rural Livelihoods • Constraints to the founding principles of pastoralism that enable HH to deal with shock. § Reduction in herd sizes (livestock disease, recurrent droughts and general water scarcity, overgrazing and land use change) § Changes in herd composition – cattle all but vanished; some camels and – more often - small stock. § Access to rangeland is becoming constrained (land acquisition and fencing off of traditional communal grazing land for private use) => conflict • Chronic lack of alternative opportunities for productive livelihoods or employment. § Untapped potential of agriculture – little investment in agriculture - production low, with some considering that production over time has been declining. § Farming still water-dependent and exposed to the climatic trends mentioned above. Potentially more vulnerable since it is sedentary • Strong desire and attempts to diversify but limited options • Mainly peri-urban (teashops, trading, fodder production, Khat sale) 33

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Trends in migration and urbanisation • Increasing sedentarisation leading to more ‘urban‘ characteristics even in rural areas: • Increasing sedentarisation of pastoralists as a result of constraints to nomadic livelihoods and changes in herd size and composition. • Agro-pastoralists increasingly relying on a semi-sedentary household for agriculture with pastoral satellites. • Creation/expansion of overcrowded and impoverished informal ‘IDP’ settlements • Increasing migration to urban areas, particularly for pastoral HH in the north • Growth of IDP settlements in Mogadishu due to insecurity and seasonal shocks elsewhere in SCS (many from riverine areas) • Trend for HH to settle for long periods (lack of hope pastoralists v farmers SCS hope to return and attempting to do so – splitting of HH) • Out-migration of able bodied and (esp male) youth => high proportion of FHHH and dependent people remain in rural settlements • Includes overseas - Yemen, Ethiopia, Libya and on to Europe and the Middle East 34

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Trends in migration and urbanisation • Increasing sedentarisation leading to more ‘urban‘ characteristics even in rural areas: • Increasing sedentarisation of pastoralists as a result of constraints to nomadic livelihoods and changes in herd size and composition. • Agro-pastoralists increasingly relying on a semi-sedentary household for agriculture with pastoral satellites. • Creation/expansion of overcrowded and impoverished informal ‘IDP’ settlements • Increasing migration to urban areas, particularly for pastoral HH in the north • Growth of IDP settlements in Mogadishu due to insecurity and seasonal shocks elsewhere in SCS (many from riverine areas) • Trend for HH to settle for long periods (lack of hope pastoralists v farmers SCS hope to return and attempting to do so – splitting of HH) • Out-migration of able bodied and (esp male) youth => high proportion of FHHH and dependent people remain in rural settlements • Includes overseas - Yemen, Ethiopia, Libya and on to Europe and the Middle East 34

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Trends in Urban Livelihoods • Primarily daily labourers – (construction and hauling, domestic servants) and petty trades (tea shops, hawking/street vendors, buying and selling milk, shoe shining, car washing and selling Khat). • Jobs are insecure and poorly paid and there is increasing competition as the influx to the cities continues. • IDPs face discrimination in the job market in competition with local people. • Markets and opportunities in the city can be far from IDP settlements and expensive to reach. • Households find it difficult to invest or diversify livelihoods as they lack the capital and skills (more acute for pastoral than farming backgrounds) • Begging increase (esp. Mogadishu – organised begging in groups) • Heterogeneity of IDP settlements depending on location and length of establishment 35

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Trends in Urban Livelihoods • Primarily daily labourers – (construction and hauling, domestic servants) and petty trades (tea shops, hawking/street vendors, buying and selling milk, shoe shining, car washing and selling Khat). • Jobs are insecure and poorly paid and there is increasing competition as the influx to the cities continues. • IDPs face discrimination in the job market in competition with local people. • Markets and opportunities in the city can be far from IDP settlements and expensive to reach. • Households find it difficult to invest or diversify livelihoods as they lack the capital and skills (more acute for pastoral than farming backgrounds) • Begging increase (esp. Mogadishu – organised begging in groups) • Heterogeneity of IDP settlements depending on location and length of establishment 35

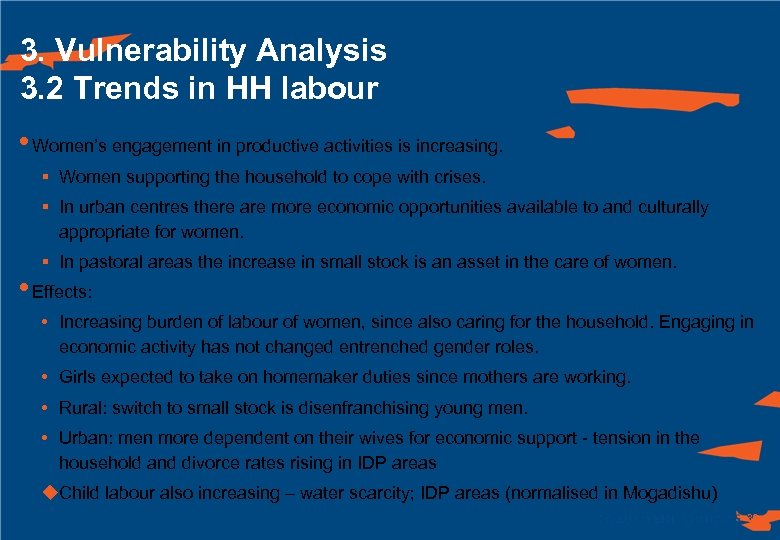

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Trends in HH labour • Women’s engagement in productive activities is increasing. § Women supporting the household to cope with crises. § In urban centres there are more economic opportunities available to and culturally appropriate for women. § In pastoral areas the increase in small stock is an asset in the care of women. • Effects: • Increasing burden of labour of women, since also caring for the household. Engaging in economic activity has not changed entrenched gender roles. • Girls expected to take on homemaker duties since mothers are working. • Rural: switch to small stock is disenfranchising young men. • Urban: men more dependent on their wives for economic support - tension in the household and divorce rates rising in IDP areas u. Child labour also increasing – water scarcity; IDP areas (normalised in Mogadishu) 36

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Trends in HH labour • Women’s engagement in productive activities is increasing. § Women supporting the household to cope with crises. § In urban centres there are more economic opportunities available to and culturally appropriate for women. § In pastoral areas the increase in small stock is an asset in the care of women. • Effects: • Increasing burden of labour of women, since also caring for the household. Engaging in economic activity has not changed entrenched gender roles. • Girls expected to take on homemaker duties since mothers are working. • Rural: switch to small stock is disenfranchising young men. • Urban: men more dependent on their wives for economic support - tension in the household and divorce rates rising in IDP areas u. Child labour also increasing – water scarcity; IDP areas (normalised in Mogadishu) 36

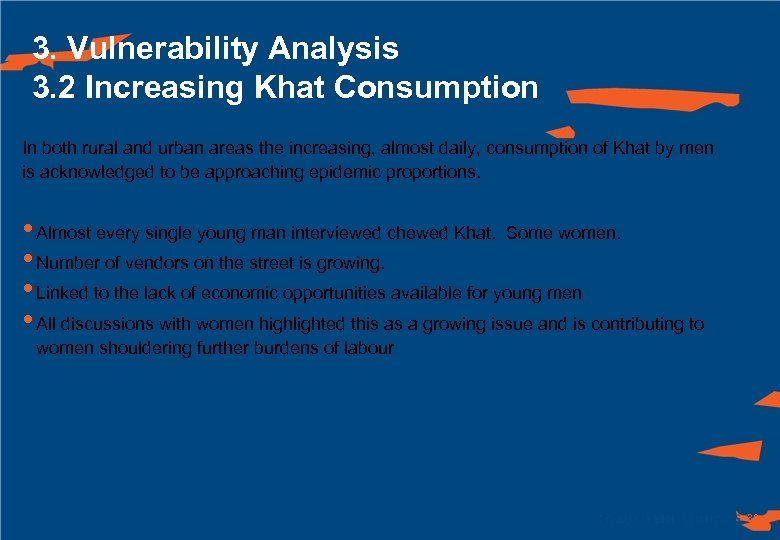

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Increasing Khat Consumption In both rural and urban areas the increasing, almost daily, consumption of Khat by men is acknowledged to be approaching epidemic proportions. • Almost every single young man interviewed chewed Khat. Some women. • Number of vendors on the street is growing. • Linked to the lack of economic opportunities available for young men • All discussions with women highlighted this as a growing issue and is contributing to women shouldering further burdens of labour 38

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Increasing Khat Consumption In both rural and urban areas the increasing, almost daily, consumption of Khat by men is acknowledged to be approaching epidemic proportions. • Almost every single young man interviewed chewed Khat. Some women. • Number of vendors on the street is growing. • Linked to the lack of economic opportunities available for young men • All discussions with women highlighted this as a growing issue and is contributing to women shouldering further burdens of labour 38

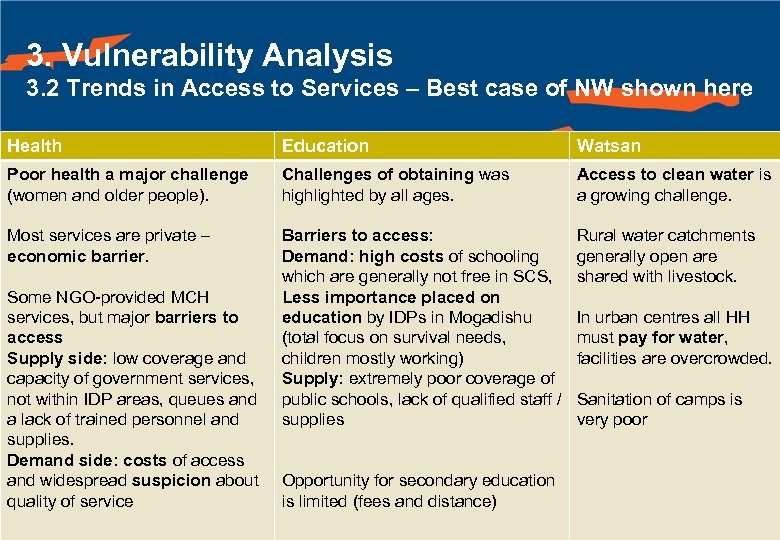

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Trends in Access to Services – Best case of NW shown here Health Education Watsan Poor health a major challenge (women and older people). Challenges of obtaining was highlighted by all ages. Access to clean water is a growing challenge. Most services are private – economic barrier. Barriers to access: Demand: high costs of schooling which are generally not free in SCS, Less importance placed on education by IDPs in Mogadishu (total focus on survival needs, children mostly working) Supply: extremely poor coverage of public schools, lack of qualified staff / supplies Rural water catchments generally open are shared with livestock. Some NGO-provided MCH services, but major barriers to access Supply side: low coverage and capacity of government services, not within IDP areas, queues and a lack of trained personnel and supplies. Demand side: costs of access and widespread suspicion about quality of service In urban centres all HH must pay for water, facilities are overcrowded. Sanitation of camps is very poor Opportunity for secondary education is limited (fees and distance) 39

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Trends in Access to Services – Best case of NW shown here Health Education Watsan Poor health a major challenge (women and older people). Challenges of obtaining was highlighted by all ages. Access to clean water is a growing challenge. Most services are private – economic barrier. Barriers to access: Demand: high costs of schooling which are generally not free in SCS, Less importance placed on education by IDPs in Mogadishu (total focus on survival needs, children mostly working) Supply: extremely poor coverage of public schools, lack of qualified staff / supplies Rural water catchments generally open are shared with livestock. Some NGO-provided MCH services, but major barriers to access Supply side: low coverage and capacity of government services, not within IDP areas, queues and a lack of trained personnel and supplies. Demand side: costs of access and widespread suspicion about quality of service In urban centres all HH must pay for water, facilities are overcrowded. Sanitation of camps is very poor Opportunity for secondary education is limited (fees and distance) 39

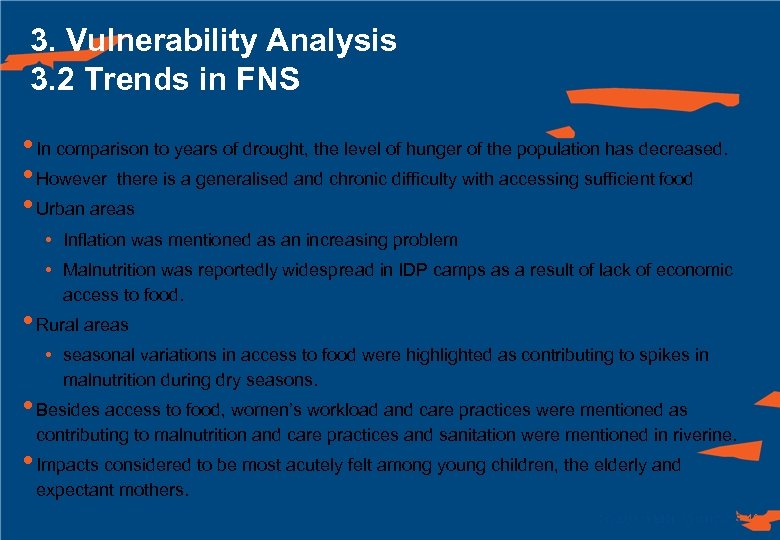

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Trends in FNS • In comparison to years of drought, the level of hunger of the population has decreased. • However there is a generalised and chronic difficulty with accessing sufficient food • Urban areas • Inflation was mentioned as an increasing problem • Malnutrition was reportedly widespread in IDP camps as a result of lack of economic access to food. • Rural areas • seasonal variations in access to food were highlighted as contributing to spikes in malnutrition during dry seasons. • Besides access to food, women’s workload and care practices were mentioned as contributing to malnutrition and care practices and sanitation were mentioned in riverine. • Impacts considered to be most acutely felt among young children, the elderly and expectant mothers. 40

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 2 Trends in FNS • In comparison to years of drought, the level of hunger of the population has decreased. • However there is a generalised and chronic difficulty with accessing sufficient food • Urban areas • Inflation was mentioned as an increasing problem • Malnutrition was reportedly widespread in IDP camps as a result of lack of economic access to food. • Rural areas • seasonal variations in access to food were highlighted as contributing to spikes in malnutrition during dry seasons. • Besides access to food, women’s workload and care practices were mentioned as contributing to malnutrition and care practices and sanitation were mentioned in riverine. • Impacts considered to be most acutely felt among young children, the elderly and expectant mothers. 40

3. 3 Shocks and stresses 42

3. 3 Shocks and stresses 42

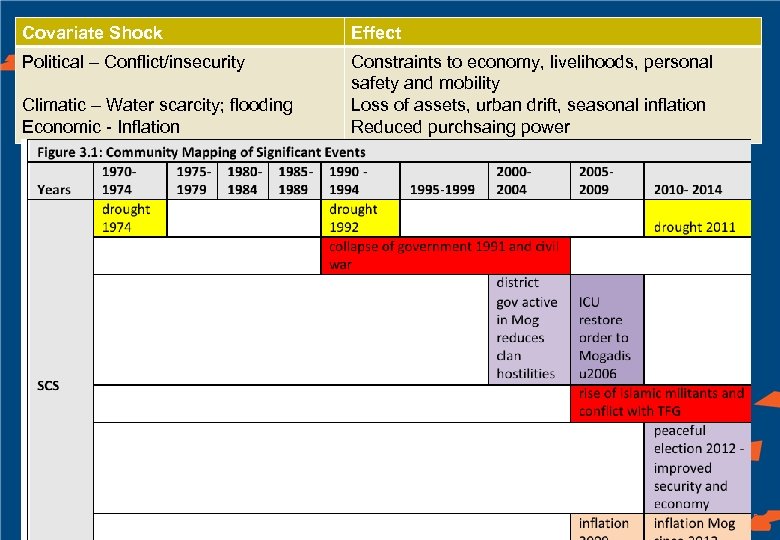

Covariate Shock Effect 3. 3 Covariate shocks and stresses Political – Conflict/insecurity Climatic – Water scarcity; flooding Economic - Inflation Constraints to economy, livelihoods, personal safety and mobility Loss of assets, urban drift, seasonal inflation Reduced purchsaing power 43

Covariate Shock Effect 3. 3 Covariate shocks and stresses Political – Conflict/insecurity Climatic – Water scarcity; flooding Economic - Inflation Constraints to economy, livelihoods, personal safety and mobility Loss of assets, urban drift, seasonal inflation Reduced purchsaing power 43

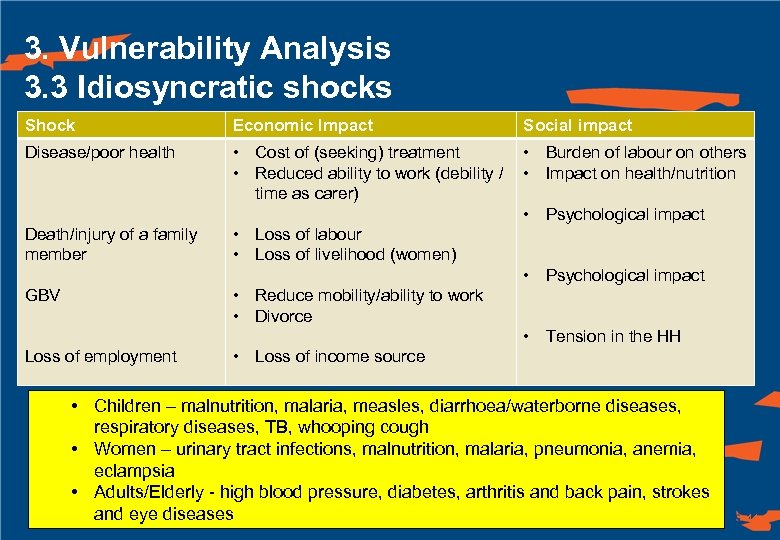

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 3 Idiosyncratic shocks Shock Economic Impact Disease/poor health • Cost of (seeking) treatment • Burden of labour on others • Reduced ability to work (debility / • Impact on health/nutrition time as carer) • Psychological impact • Loss of labour • Loss of livelihood (women) • Psychological impact • Reduce mobility/ability to work • Divorce • Tension in the HH • Loss of income source Death/injury of a family member GBV Loss of employment Social impact • Children – malnutrition, malaria, measles, diarrhoea/waterborne diseases, respiratory diseases, TB, whooping cough • Women – urinary tract infections, malnutrition, malaria, pneumonia, anemia, eclampsia • Adults/Elderly - high blood pressure, diabetes, arthritis and back pain, strokes and eye diseases 44

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 3 Idiosyncratic shocks Shock Economic Impact Disease/poor health • Cost of (seeking) treatment • Burden of labour on others • Reduced ability to work (debility / • Impact on health/nutrition time as carer) • Psychological impact • Loss of labour • Loss of livelihood (women) • Psychological impact • Reduce mobility/ability to work • Divorce • Tension in the HH • Loss of income source Death/injury of a family member GBV Loss of employment Social impact • Children – malnutrition, malaria, measles, diarrhoea/waterborne diseases, respiratory diseases, TB, whooping cough • Women – urinary tract infections, malnutrition, malaria, pneumonia, anemia, eclampsia • Adults/Elderly - high blood pressure, diabetes, arthritis and back pain, strokes and eye diseases 44

3. 4 Coping Strategies 45

3. 4 Coping Strategies 45

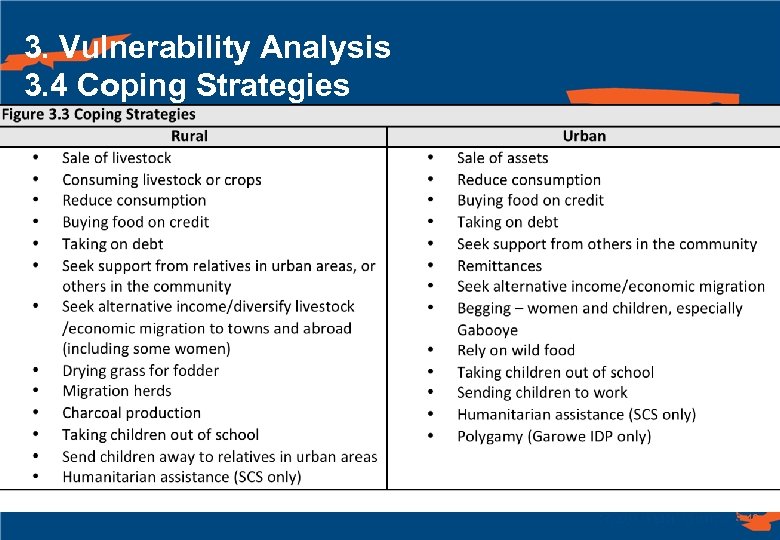

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 4 Coping Strategies 46

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 4 Coping Strategies 46

3. 5 Community Analysis of Vulnerability 47

3. 5 Community Analysis of Vulnerability 47

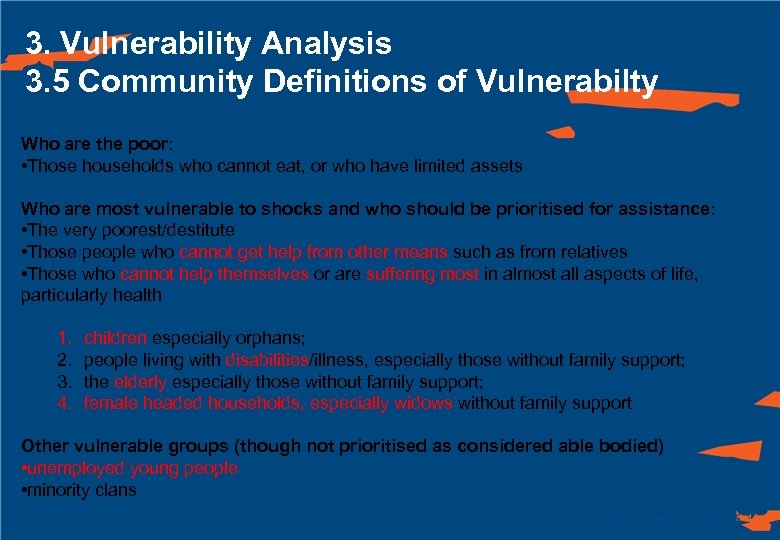

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 5 Community Definitions of Vulnerabilty Who are the poor: • Those households who cannot eat, or who have limited assets Who are most vulnerable to shocks and who should be prioritised for assistance: • The very poorest/destitute • Those people who cannot get help from other means such as from relatives • Those who cannot help themselves or are suffering most in almost all aspects of life, particularly health 1. 2. 3. 4. children especially orphans; people living with disabilities/illness, especially those without family support; the elderly especially those without family support; female headed households, especially widows without family support Other vulnerable groups (though not prioritised as considered able bodied) • unemployed young people • minority clans 48

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 5 Community Definitions of Vulnerabilty Who are the poor: • Those households who cannot eat, or who have limited assets Who are most vulnerable to shocks and who should be prioritised for assistance: • The very poorest/destitute • Those people who cannot get help from other means such as from relatives • Those who cannot help themselves or are suffering most in almost all aspects of life, particularly health 1. 2. 3. 4. children especially orphans; people living with disabilities/illness, especially those without family support; the elderly especially those without family support; female headed households, especially widows without family support Other vulnerable groups (though not prioritised as considered able bodied) • unemployed young people • minority clans 48

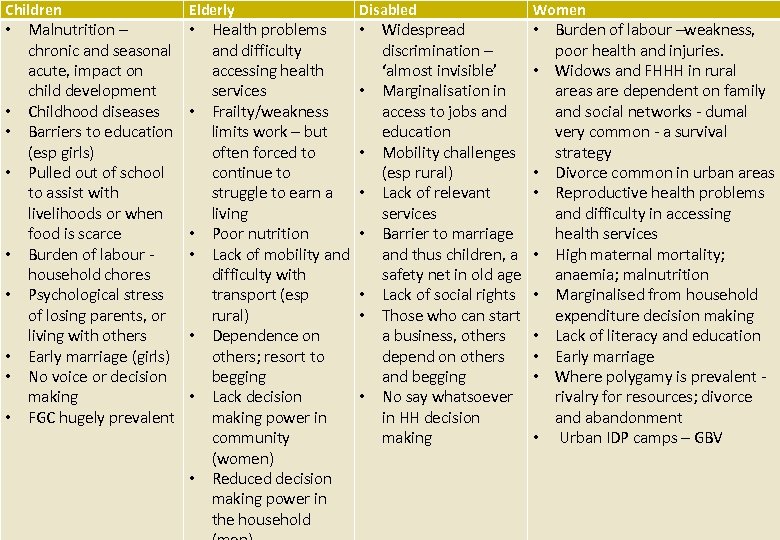

Children Elderly Disabled • Health problems • Widespread 4. 2 Vulnerability Analysis • Malnutrition – chronic and seasonal acute, impact on child development • Childhood diseases • Barriers to education (esp girls) • Pulled out of school to assist with livelihoods or when food is scarce • Burden of labour - household chores • Psychological stress of losing parents, or living with others • Early marriage (girls) • No voice or decision making • FGC hugely prevalent • • • and difficulty accessing health services Frailty/weakness limits work – but often forced to continue to struggle to earn a living Poor nutrition Lack of mobility and difficulty with transport (esp rural) Dependence on others; resort to begging Lack decision making power in community (women) Reduced decision making power in the household • • discrimination – ‘almost invisible’ Marginalisation in access to jobs and education Mobility challenges (esp rural) Lack of relevant services Barrier to marriage and thus children, a safety net in old age Lack of social rights Those who can start a business, others depend on others and begging No say whatsoever in HH decision making Women • Burden of labour –weakness, poor health and injuries. • Widows and FHHH in rural areas are dependent on family and social networks - dumal very common - a survival strategy • Divorce common in urban areas • Reproductive health problems and difficulty in accessing health services • High maternal mortality; anaemia; malnutrition • Marginalised from household expenditure decision making • Lack of literacy and education • Early marriage • Where polygamy is prevalent - rivalry for resources; divorce and abandonment • Urban IDP camps – GBV 49

Children Elderly Disabled • Health problems • Widespread 4. 2 Vulnerability Analysis • Malnutrition – chronic and seasonal acute, impact on child development • Childhood diseases • Barriers to education (esp girls) • Pulled out of school to assist with livelihoods or when food is scarce • Burden of labour - household chores • Psychological stress of losing parents, or living with others • Early marriage (girls) • No voice or decision making • FGC hugely prevalent • • • and difficulty accessing health services Frailty/weakness limits work – but often forced to continue to struggle to earn a living Poor nutrition Lack of mobility and difficulty with transport (esp rural) Dependence on others; resort to begging Lack decision making power in community (women) Reduced decision making power in the household • • discrimination – ‘almost invisible’ Marginalisation in access to jobs and education Mobility challenges (esp rural) Lack of relevant services Barrier to marriage and thus children, a safety net in old age Lack of social rights Those who can start a business, others depend on others and begging No say whatsoever in HH decision making Women • Burden of labour –weakness, poor health and injuries. • Widows and FHHH in rural areas are dependent on family and social networks - dumal very common - a survival strategy • Divorce common in urban areas • Reproductive health problems and difficulty in accessing health services • High maternal mortality; anaemia; malnutrition • Marginalised from household expenditure decision making • Lack of literacy and education • Early marriage • Where polygamy is prevalent - rivalry for resources; divorce and abandonment • Urban IDP camps – GBV 49

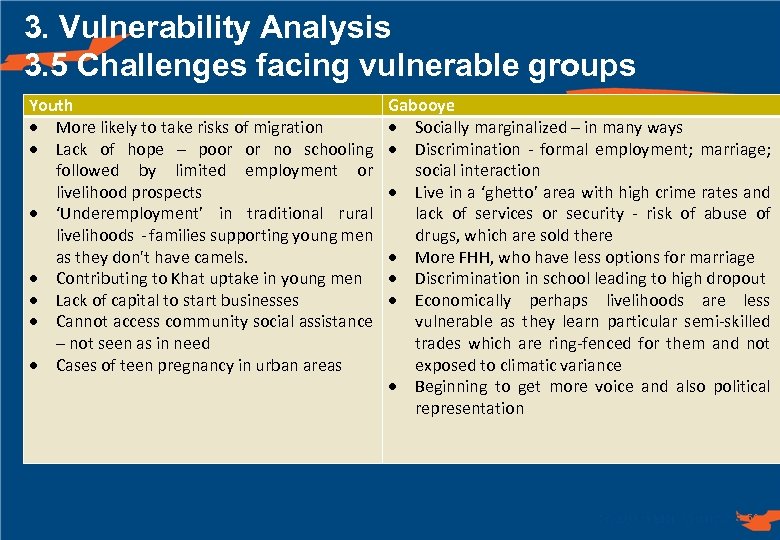

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 5 Challenges facing vulnerable groups Youth More likely to take risks of migration Lack of hope – poor or no schooling followed by limited employment or livelihood prospects ‘Underemployment’ in traditional rural livelihoods - families supporting young men as they don't have camels. Contributing to Khat uptake in young men Lack of capital to start businesses Cannot access community social assistance – not seen as in need Cases of teen pregnancy in urban areas Gabooye Socially marginalized – in many ways Discrimination - formal employment; marriage; social interaction Live in a ‘ghetto’ area with high crime rates and lack of services or security - risk of abuse of drugs, which are sold there More FHH, who have less options for marriage Discrimination in school leading to high dropout Economically perhaps livelihoods are less vulnerable as they learn particular semi-skilled trades which are ring-fenced for them and not exposed to climatic variance Beginning to get more voice and also political representation 50

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 5 Challenges facing vulnerable groups Youth More likely to take risks of migration Lack of hope – poor or no schooling followed by limited employment or livelihood prospects ‘Underemployment’ in traditional rural livelihoods - families supporting young men as they don't have camels. Contributing to Khat uptake in young men Lack of capital to start businesses Cannot access community social assistance – not seen as in need Cases of teen pregnancy in urban areas Gabooye Socially marginalized – in many ways Discrimination - formal employment; marriage; social interaction Live in a ‘ghetto’ area with high crime rates and lack of services or security - risk of abuse of drugs, which are sold there More FHH, who have less options for marriage Discrimination in school leading to high dropout Economically perhaps livelihoods are less vulnerable as they learn particular semi-skilled trades which are ring-fenced for them and not exposed to climatic variance Beginning to get more voice and also political representation 50

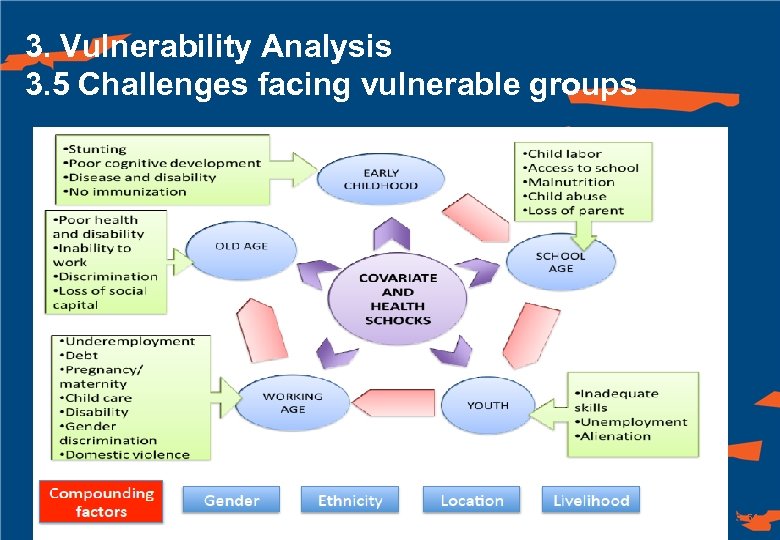

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 5 Challenges facing vulnerable groups 51

3. Vulnerability Analysis 3. 5 Challenges facing vulnerable groups 51

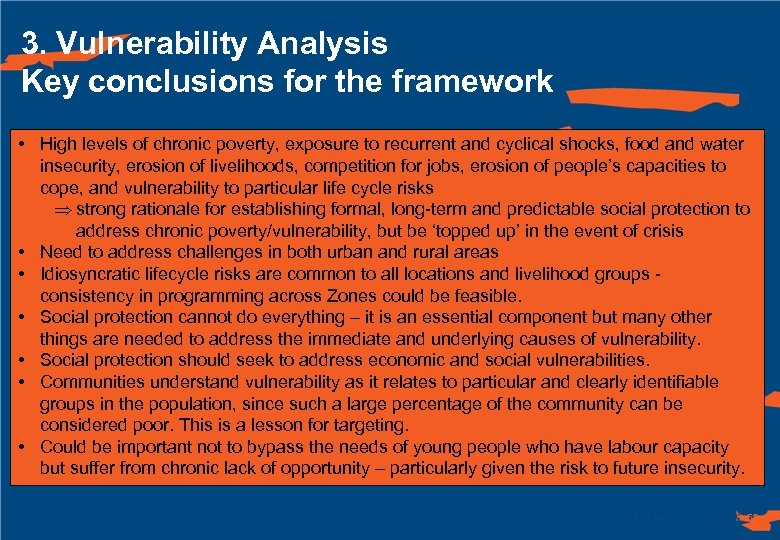

3. Vulnerability Analysis Key conclusions for the framework • High levels of chronic poverty, exposure to recurrent and cyclical shocks, food and water insecurity, erosion of livelihoods, competition for jobs, erosion of people’s capacities to cope, and vulnerability to particular life cycle risks strong rationale for establishing formal, long-term and predictable social protection to address chronic poverty/vulnerability, but be ‘topped up’ in the event of crisis • Need to address challenges in both urban and rural areas • Idiosyncratic lifecycle risks are common to all locations and livelihood groups - consistency in programming across Zones could be feasible. • Social protection cannot do everything – it is an essential component but many other things are needed to address the immediate and underlying causes of vulnerability. • Social protection should seek to address economic and social vulnerabilities. • Communities understand vulnerability as it relates to particular and clearly identifiable groups in the population, since such a large percentage of the community can be considered poor. This is a lesson for targeting. • Could be important not to bypass the needs of young people who have labour capacity but suffer from chronic lack of opportunity – particularly given the risk to future insecurity. 52

3. Vulnerability Analysis Key conclusions for the framework • High levels of chronic poverty, exposure to recurrent and cyclical shocks, food and water insecurity, erosion of livelihoods, competition for jobs, erosion of people’s capacities to cope, and vulnerability to particular life cycle risks strong rationale for establishing formal, long-term and predictable social protection to address chronic poverty/vulnerability, but be ‘topped up’ in the event of crisis • Need to address challenges in both urban and rural areas • Idiosyncratic lifecycle risks are common to all locations and livelihood groups - consistency in programming across Zones could be feasible. • Social protection cannot do everything – it is an essential component but many other things are needed to address the immediate and underlying causes of vulnerability. • Social protection should seek to address economic and social vulnerabilities. • Communities understand vulnerability as it relates to particular and clearly identifiable groups in the population, since such a large percentage of the community can be considered poor. This is a lesson for targeting. • Could be important not to bypass the needs of young people who have labour capacity but suffer from chronic lack of opportunity – particularly given the risk to future insecurity. 52

4. Mapping Social Protection 53

4. Mapping Social Protection 53

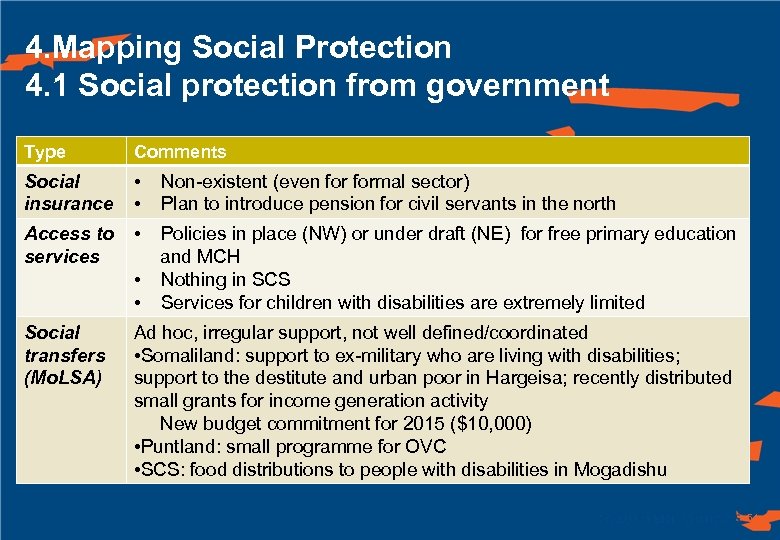

4. Mapping Social Protection 4. 1 Social protection from government Type Comments Social insurance • • Access to services • Policies in place (NW) or under draft (NE) for free primary education and MCH • Nothing in SCS • Services for children with disabilities are extremely limited Social transfers (Mo. LSA) Ad hoc, irregular support, not well defined/coordinated • Somaliland: support to ex-military who are living with disabilities; support to the destitute and urban poor in Hargeisa; recently distributed small grants for income generation activity New budget commitment for 2015 ($10, 000) • Puntland: small programme for OVC • SCS: food distributions to people with disabilities in Mogadishu Non-existent (even formal sector) Plan to introduce pension for civil servants in the north 54

4. Mapping Social Protection 4. 1 Social protection from government Type Comments Social insurance • • Access to services • Policies in place (NW) or under draft (NE) for free primary education and MCH • Nothing in SCS • Services for children with disabilities are extremely limited Social transfers (Mo. LSA) Ad hoc, irregular support, not well defined/coordinated • Somaliland: support to ex-military who are living with disabilities; support to the destitute and urban poor in Hargeisa; recently distributed small grants for income generation activity New budget commitment for 2015 ($10, 000) • Puntland: small programme for OVC • SCS: food distributions to people with disabilities in Mogadishu Non-existent (even formal sector) Plan to introduce pension for civil servants in the north 54

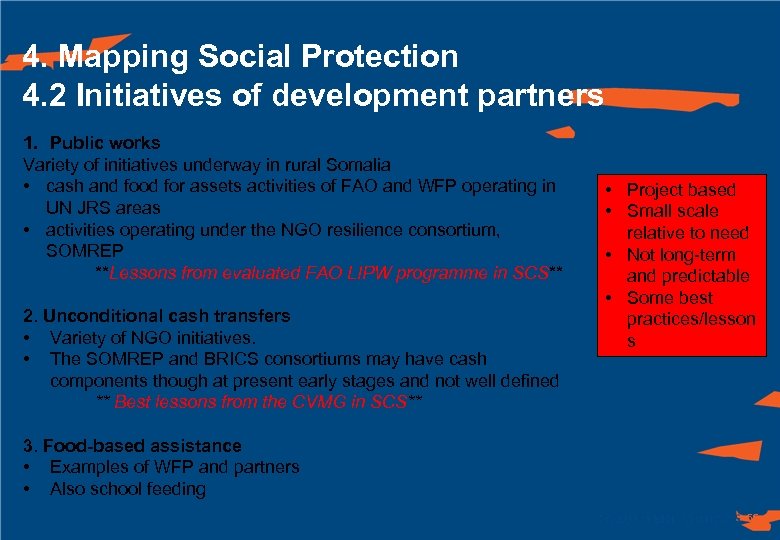

4. Mapping Social Protection 4. 2 Initiatives of development partners 1. Public works Variety of initiatives underway in rural Somalia • cash and food for assets activities of FAO and WFP operating in UN JRS areas • activities operating under the NGO resilience consortium, SOMREP **Lessons from evaluated FAO LIPW programme in SCS** 2. Unconditional cash transfers • Variety of NGO initiatives. • The SOMREP and BRICS consortiums may have cash components though at present early stages and not well defined ** Best lessons from the CVMG in SCS** • Project based • Small scale relative to need • Not long-term and predictable • Some best practices/lesson s 3. Food-based assistance • Examples of WFP and partners • Also school feeding 55

4. Mapping Social Protection 4. 2 Initiatives of development partners 1. Public works Variety of initiatives underway in rural Somalia • cash and food for assets activities of FAO and WFP operating in UN JRS areas • activities operating under the NGO resilience consortium, SOMREP **Lessons from evaluated FAO LIPW programme in SCS** 2. Unconditional cash transfers • Variety of NGO initiatives. • The SOMREP and BRICS consortiums may have cash components though at present early stages and not well defined ** Best lessons from the CVMG in SCS** • Project based • Small scale relative to need • Not long-term and predictable • Some best practices/lesson s 3. Food-based assistance • Examples of WFP and partners • Also school feeding 55

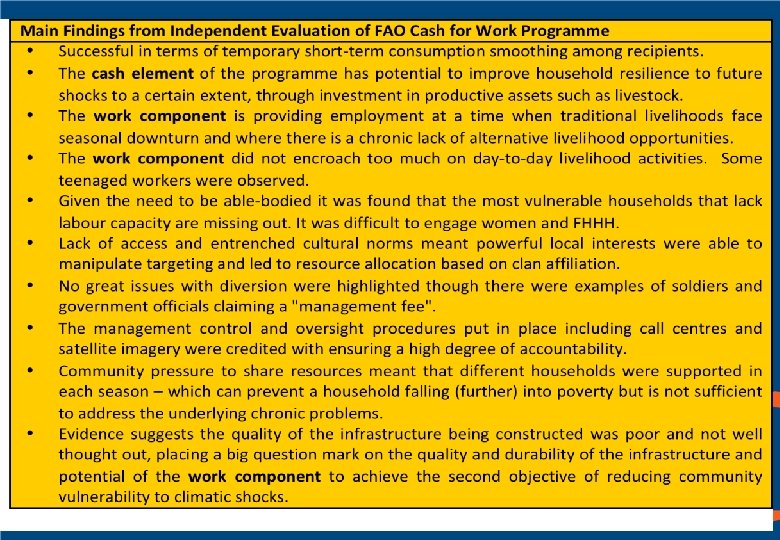

4. Mapping Social Protection 4. 2 Experiences of development partners: FAO 56

4. Mapping Social Protection 4. 2 Experiences of development partners: FAO 56

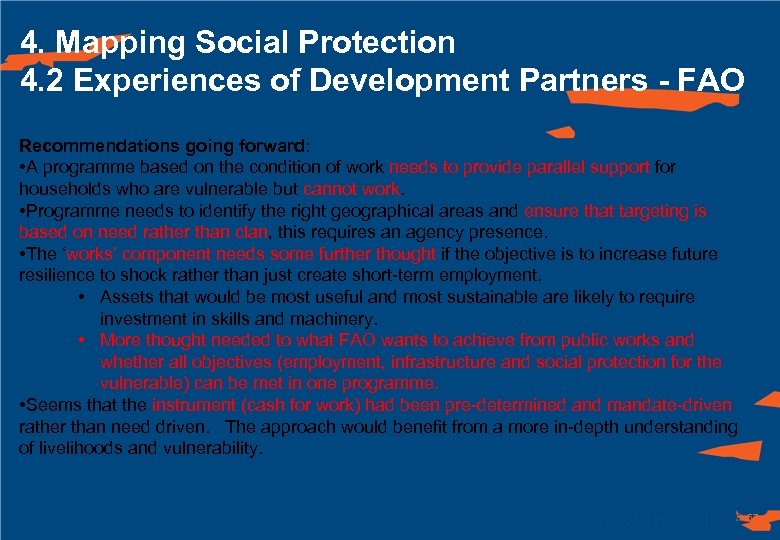

4. Mapping Social Protection 4. 2 Experiences of Development Partners - FAO Recommendations going forward: • A programme based on the condition of work needs to provide parallel support for households who are vulnerable but cannot work. • Programme needs to identify the right geographical areas and ensure that targeting is based on need rather than clan, this requires an agency presence. • The ‘works’ component needs some further thought if the objective is to increase future resilience to shock rather than just create short-term employment. • Assets that would be most useful and most sustainable are likely to require investment in skills and machinery. • More thought needed to what FAO wants to achieve from public works and whether all objectives (employment, infrastructure and social protection for the vulnerable) can be met in one programme. • Seems that the instrument (cash for work) had been pre-determined and mandate-driven rather than need driven. The approach would benefit from a more in-depth understanding of livelihoods and vulnerability. 57

4. Mapping Social Protection 4. 2 Experiences of Development Partners - FAO Recommendations going forward: • A programme based on the condition of work needs to provide parallel support for households who are vulnerable but cannot work. • Programme needs to identify the right geographical areas and ensure that targeting is based on need rather than clan, this requires an agency presence. • The ‘works’ component needs some further thought if the objective is to increase future resilience to shock rather than just create short-term employment. • Assets that would be most useful and most sustainable are likely to require investment in skills and machinery. • More thought needed to what FAO wants to achieve from public works and whether all objectives (employment, infrastructure and social protection for the vulnerable) can be met in one programme. • Seems that the instrument (cash for work) had been pre-determined and mandate-driven rather than need driven. The approach would benefit from a more in-depth understanding of livelihoods and vulnerability. 57

4. Mapping Social Protection 4. 2 Experiences of Development Partners - CVMG 58

4. Mapping Social Protection 4. 2 Experiences of Development Partners - CVMG 58

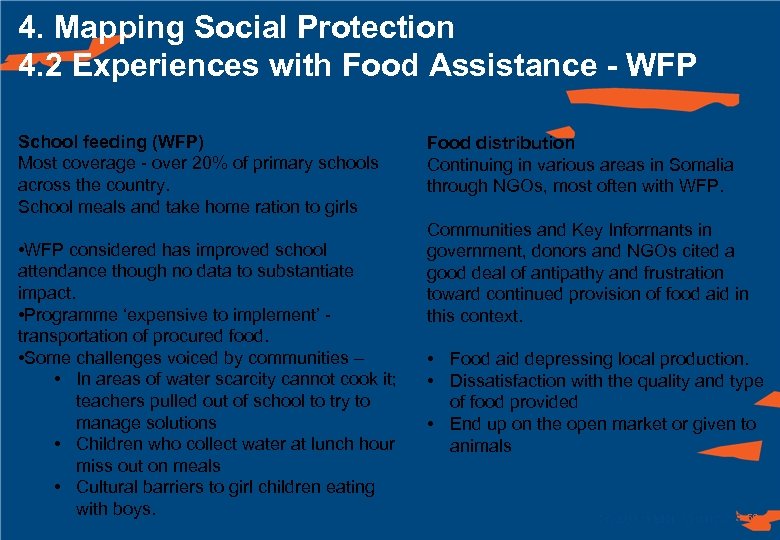

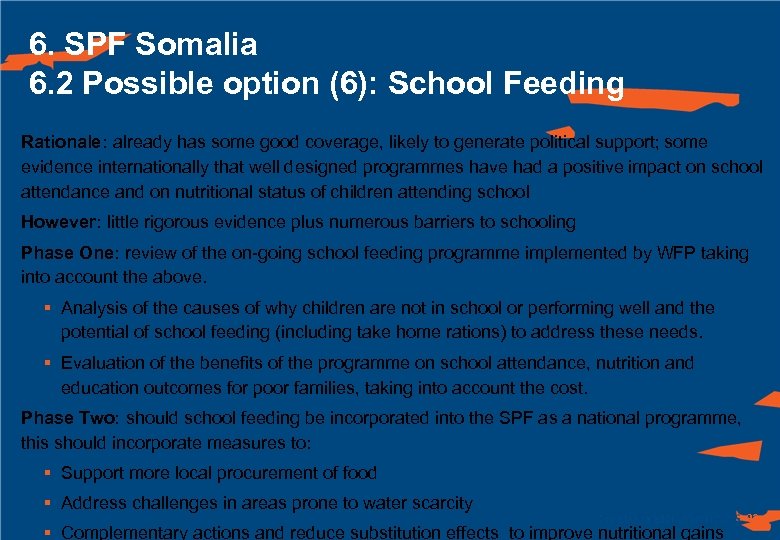

4. Mapping Social Protection 4. 2 Experiences with Food Assistance - WFP School feeding (WFP) Most coverage - over 20% of primary schools across the country. School meals and take home ration to girls • WFP considered has improved school attendance though no data to substantiate impact. • Programme ‘expensive to implement’ transportation of procured food. • Some challenges voiced by communities – • In areas of water scarcity cannot cook it; teachers pulled out of school to try to manage solutions • Children who collect water at lunch hour miss out on meals • Cultural barriers to girl children eating with boys. Food distribution Continuing in various areas in Somalia through NGOs, most often with WFP. Communities and Key Informants in government, donors and NGOs cited a good deal of antipathy and frustration toward continued provision of food aid in this context. • Food aid depressing local production. • Dissatisfaction with the quality and type of food provided • End up on the open market or given to animals 59

4. Mapping Social Protection 4. 2 Experiences with Food Assistance - WFP School feeding (WFP) Most coverage - over 20% of primary schools across the country. School meals and take home ration to girls • WFP considered has improved school attendance though no data to substantiate impact. • Programme ‘expensive to implement’ transportation of procured food. • Some challenges voiced by communities – • In areas of water scarcity cannot cook it; teachers pulled out of school to try to manage solutions • Children who collect water at lunch hour miss out on meals • Cultural barriers to girl children eating with boys. Food distribution Continuing in various areas in Somalia through NGOs, most often with WFP. Communities and Key Informants in government, donors and NGOs cited a good deal of antipathy and frustration toward continued provision of food aid in this context. • Food aid depressing local production. • Dissatisfaction with the quality and type of food provided • End up on the open market or given to animals 59

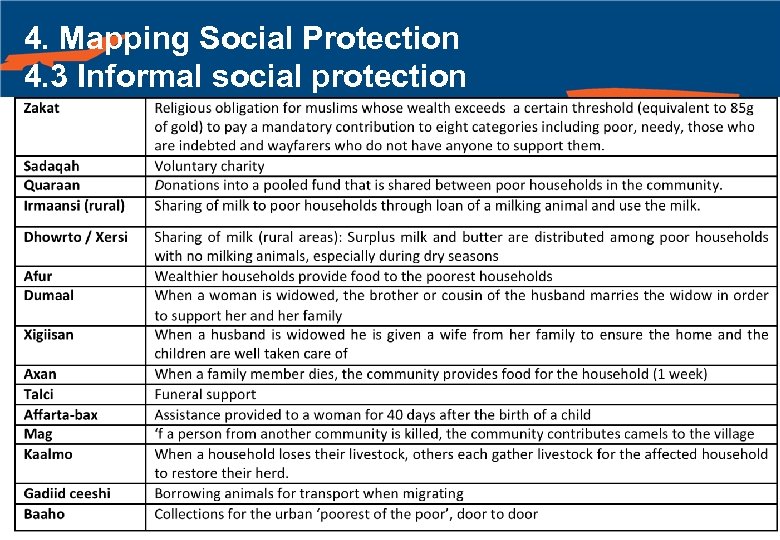

4. Mapping Social Protection 4. 3 Informal social protection 60

4. Mapping Social Protection 4. 3 Informal social protection 60

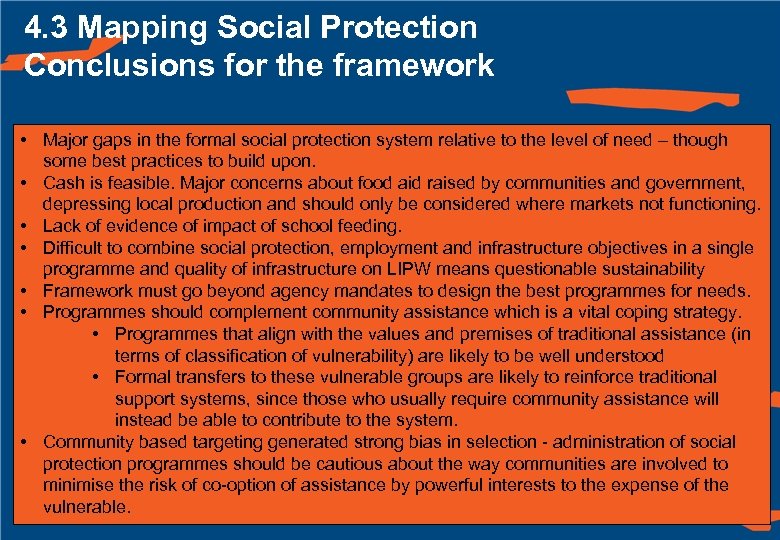

4. 3 Mapping Social Protection Conclusions for the framework • Major gaps in the formal social protection system relative to the level of need – though some best practices to build upon. • Cash is feasible. Major concerns about food aid raised by communities and government, depressing local production and should only be considered where markets not functioning. • Lack of evidence of impact of school feeding. • Difficult to combine social protection, employment and infrastructure objectives in a single programme and quality of infrastructure on LIPW means questionable sustainability • Framework must go beyond agency mandates to design the best programmes for needs. • Programmes should complement community assistance which is a vital coping strategy. • Programmes that align with the values and premises of traditional assistance (in terms of classification of vulnerability) are likely to be well understood • Formal transfers to these vulnerable groups are likely to reinforce traditional support systems, since those who usually require community assistance will instead be able to contribute to the system. • Community based targeting generated strong bias in selection - administration of social protection programmes should be cautious about the way communities are involved to minimise the risk of co-option of assistance by powerful interests to the expense of the vulnerable. 61

4. 3 Mapping Social Protection Conclusions for the framework • Major gaps in the formal social protection system relative to the level of need – though some best practices to build upon. • Cash is feasible. Major concerns about food aid raised by communities and government, depressing local production and should only be considered where markets not functioning. • Lack of evidence of impact of school feeding. • Difficult to combine social protection, employment and infrastructure objectives in a single programme and quality of infrastructure on LIPW means questionable sustainability • Framework must go beyond agency mandates to design the best programmes for needs. • Programmes should complement community assistance which is a vital coping strategy. • Programmes that align with the values and premises of traditional assistance (in terms of classification of vulnerability) are likely to be well understood • Formal transfers to these vulnerable groups are likely to reinforce traditional support systems, since those who usually require community assistance will instead be able to contribute to the system. • Community based targeting generated strong bias in selection - administration of social protection programmes should be cautious about the way communities are involved to minimise the risk of co-option of assistance by powerful interests to the expense of the vulnerable. 61

5. Enabling Environment 62

5. Enabling Environment 62

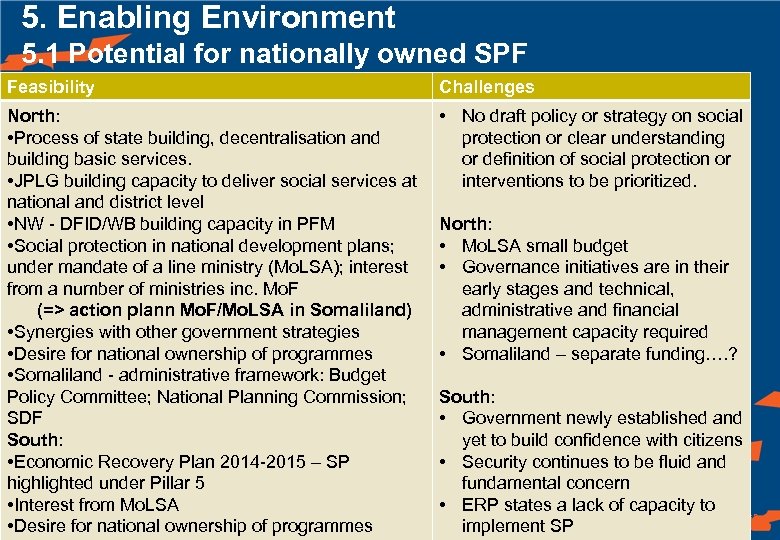

5. Enabling Environment 5. 1 Potential for nationally owned SPF Feasibility Challenges North: • Process of state building, decentralisation and building basic services. • JPLG building capacity to deliver social services at national and district level • NW - DFID/WB building capacity in PFM • Social protection in national development plans; under mandate of a line ministry (Mo. LSA); interest from a number of ministries inc. Mo. F (=> action plann Mo. F/Mo. LSA in Somaliland) • Synergies with other government strategies • Desire for national ownership of programmes • Somaliland - administrative framework: Budget Policy Committee; National Planning Commission; SDF South: • Economic Recovery Plan 2014 -2015 – SP highlighted under Pillar 5 • Interest from Mo. LSA • Desire for national ownership of programmes • No draft policy or strategy on social protection or clear understanding or definition of social protection or interventions to be prioritized. North: • Mo. LSA small budget • Governance initiatives are in their early stages and technical, administrative and financial management capacity required • Somaliland – separate funding…. ? South: • Government newly established and yet to build confidence with citizens • Security continues to be fluid and fundamental concern • ERP states a lack of capacity to 63 implement SP

5. Enabling Environment 5. 1 Potential for nationally owned SPF Feasibility Challenges North: • Process of state building, decentralisation and building basic services. • JPLG building capacity to deliver social services at national and district level • NW - DFID/WB building capacity in PFM • Social protection in national development plans; under mandate of a line ministry (Mo. LSA); interest from a number of ministries inc. Mo. F (=> action plann Mo. F/Mo. LSA in Somaliland) • Synergies with other government strategies • Desire for national ownership of programmes • Somaliland - administrative framework: Budget Policy Committee; National Planning Commission; SDF South: • Economic Recovery Plan 2014 -2015 – SP highlighted under Pillar 5 • Interest from Mo. LSA • Desire for national ownership of programmes • No draft policy or strategy on social protection or clear understanding or definition of social protection or interventions to be prioritized. North: • Mo. LSA small budget • Governance initiatives are in their early stages and technical, administrative and financial management capacity required • Somaliland – separate funding…. ? South: • Government newly established and yet to build confidence with citizens • Security continues to be fluid and fundamental concern • ERP states a lack of capacity to 63 implement SP

5. Enabling Environment 5. 2 Administration and implementing partners Administrative processes on social transfer programme: communications; registration and enrolment of beneficiaries; establishing and maintaining the database; preparing monthly payment requests; monitoring; managing a grievance process While national and local government capacity being built, in all Zones some support to implementation will be required, and will be essential in SCS. • Government role: In the North it could be possible for district authorities to be directly involved in elements of the administration cycle. In SCS this is considered unlikely in the short-term and transitional programming required. • CSO role: civil society partners with expertise in cash transfer operations provide added value and support for administrative duties, with a plan for progressive transfer of responsibility (HSNP Kenya). Resilience consortia. But coordination challenges. • UN role: high level coordination, supporting CSOs to set up robust monitoring and accountability mechanisms, advocacy around governance and fundraising, and capacity development 64

5. Enabling Environment 5. 2 Administration and implementing partners Administrative processes on social transfer programme: communications; registration and enrolment of beneficiaries; establishing and maintaining the database; preparing monthly payment requests; monitoring; managing a grievance process While national and local government capacity being built, in all Zones some support to implementation will be required, and will be essential in SCS. • Government role: In the North it could be possible for district authorities to be directly involved in elements of the administration cycle. In SCS this is considered unlikely in the short-term and transitional programming required. • CSO role: civil society partners with expertise in cash transfer operations provide added value and support for administrative duties, with a plan for progressive transfer of responsibility (HSNP Kenya). Resilience consortia. But coordination challenges. • UN role: high level coordination, supporting CSOs to set up robust monitoring and accountability mechanisms, advocacy around governance and fundraising, and capacity development 64

5. Enabling Environment 5. 3 Implementing partners (payment provider) International best practice to outsource payment services to a dedicated provider Hawala money transfer system and mobile money transfer services have been used to successfully to deliver cash transfers • Mobile money transfer market in Somalia is one of the most rapidly expanding markets globally (GSMA) • Mobile money coverage is rapidly expanding and is already penetrating rural areas. In the areas visited on this study, penetration appeared greater than Hawala agents and almost all businesses are accepting e-money now • Difficult to extrapolate this up to national level – but different business model and impact than seen elsewhere, seems to becoming truly financially inclusive (even in Kenya people still cash out v here being used as true e-money) • It has potential to support households in the event of migration or displacement. • Globally, e-payments proven to be cheaper and more efficient for governments over time and most are transitioning. Good practice to assess the relative merits through a tender. It may be that more than 1 provider is needed in at least in the first instance. 67

5. Enabling Environment 5. 3 Implementing partners (payment provider) International best practice to outsource payment services to a dedicated provider Hawala money transfer system and mobile money transfer services have been used to successfully to deliver cash transfers • Mobile money transfer market in Somalia is one of the most rapidly expanding markets globally (GSMA) • Mobile money coverage is rapidly expanding and is already penetrating rural areas. In the areas visited on this study, penetration appeared greater than Hawala agents and almost all businesses are accepting e-money now • Difficult to extrapolate this up to national level – but different business model and impact than seen elsewhere, seems to becoming truly financially inclusive (even in Kenya people still cash out v here being used as true e-money) • It has potential to support households in the event of migration or displacement. • Globally, e-payments proven to be cheaper and more efficient for governments over time and most are transitioning. Good practice to assess the relative merits through a tender. It may be that more than 1 provider is needed in at least in the first instance. 67

5. Enabling Environment 5. 4 Opportunity for long-term support Clearly this is essential (15 years minimum – compare to Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda) Has been one of the challenges in supporting developmental initiatives in Somalia Donor appetite for longer-term engagement, and financing of SP, is growing DFID/EC provide extensive financial and TA support to long-term CT programmes in LICs • DFID has earmarked ‘some sort of support’ for social protection (currently undefined) and is recruiting a Social Development Advisor • EU cited willingness to support a framework based on a longer-term engagement strategy with continual support provided to the very poor and vulnerable and ability to scale up during a crisis; and to support capacity building for programme delivery. • ECHO - humanitarian funds can be used as part of longer-term strategies, if these improve response to and mitigate impact of future humanitarian emergencies. • Could co-finance a mechanis’ to fund scaling up of CT when a shock occurs’, • Could finance the longer-term systems on which such seasonal ‘safety nets’ would be based. 68

5. Enabling Environment 5. 4 Opportunity for long-term support Clearly this is essential (15 years minimum – compare to Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda) Has been one of the challenges in supporting developmental initiatives in Somalia Donor appetite for longer-term engagement, and financing of SP, is growing DFID/EC provide extensive financial and TA support to long-term CT programmes in LICs • DFID has earmarked ‘some sort of support’ for social protection (currently undefined) and is recruiting a Social Development Advisor • EU cited willingness to support a framework based on a longer-term engagement strategy with continual support provided to the very poor and vulnerable and ability to scale up during a crisis; and to support capacity building for programme delivery. • ECHO - humanitarian funds can be used as part of longer-term strategies, if these improve response to and mitigate impact of future humanitarian emergencies. • Could co-finance a mechanis’ to fund scaling up of CT when a shock occurs’, • Could finance the longer-term systems on which such seasonal ‘safety nets’ would be based. 68

5. Enabling Environment 5. 4 Potential of financing mechanisms Historically low domestic revenues => limited budget for social services. Donor funding is required - what financing mechanisms currently exist? Somaliland - potential of the SDF: • first example of a multi-donor trust fund (MDTF) supporting national development priorities. This year the fund is projected to make up 6% of the national budget • Sectors prioritized at present do not relate to social development but this could change • Forthcoming World Bank MDTF for infrastructure could change the priorities under SDF • DFID hope a second phase of the SDF could look at basic services in Sool and Sanaag (concept note stage, eta 2015 -2016). There is the opportunity of using this mechanism for funding sp programmes. Country wide - Stability fund: to be set up by DFID, focus on bottom up approaches that act as peace dividend. It hasn’t focused yet on basic services. There could be opportunities for supporting the implementation of the framework through the Fund in the future. World Bank MDTF for infrastructure (appetite for joint funding of national priorities) 70

5. Enabling Environment 5. 4 Potential of financing mechanisms Historically low domestic revenues => limited budget for social services. Donor funding is required - what financing mechanisms currently exist? Somaliland - potential of the SDF: • first example of a multi-donor trust fund (MDTF) supporting national development priorities. This year the fund is projected to make up 6% of the national budget • Sectors prioritized at present do not relate to social development but this could change • Forthcoming World Bank MDTF for infrastructure could change the priorities under SDF • DFID hope a second phase of the SDF could look at basic services in Sool and Sanaag (concept note stage, eta 2015 -2016). There is the opportunity of using this mechanism for funding sp programmes. Country wide - Stability fund: to be set up by DFID, focus on bottom up approaches that act as peace dividend. It hasn’t focused yet on basic services. There could be opportunities for supporting the implementation of the framework through the Fund in the future. World Bank MDTF for infrastructure (appetite for joint funding of national priorities) 70

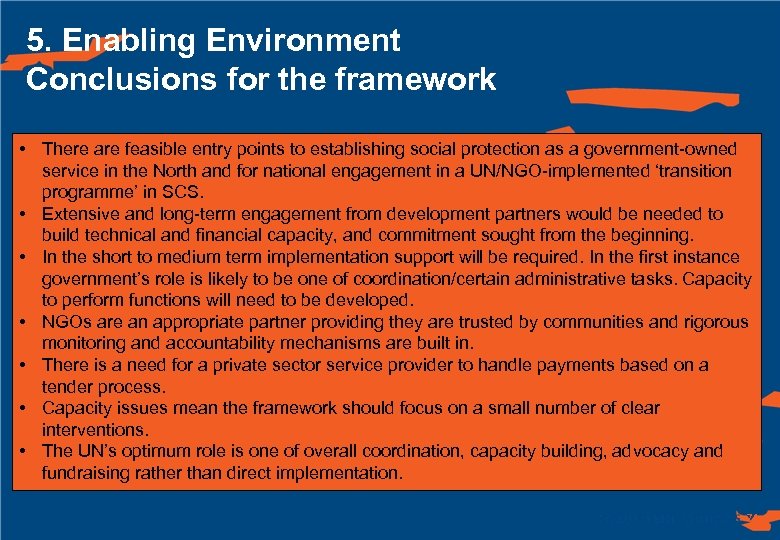

5. Enabling Environment Conclusions for the framework • There are feasible entry points to establishing social protection as a government-owned service in the North and for national engagement in a UN/NGO-implemented ‘transition programme’ in SCS. • Extensive and long-term engagement from development partners would be needed to build technical and financial capacity, and commitment sought from the beginning. • In the short to medium term implementation support will be required. In the first instance government’s role is likely to be one of coordination/certain administrative tasks. Capacity to perform functions will need to be developed. • NGOs are an appropriate partner providing they are trusted by communities and rigorous monitoring and accountability mechanisms are built in. • There is a need for a private sector service provider to handle payments based on a tender process. • Capacity issues mean the framework should focus on a small number of clear interventions. • The UN’s optimum role is one of overall coordination, capacity building, advocacy and fundraising rather than direct implementation. 71

5. Enabling Environment Conclusions for the framework • There are feasible entry points to establishing social protection as a government-owned service in the North and for national engagement in a UN/NGO-implemented ‘transition programme’ in SCS. • Extensive and long-term engagement from development partners would be needed to build technical and financial capacity, and commitment sought from the beginning. • In the short to medium term implementation support will be required. In the first instance government’s role is likely to be one of coordination/certain administrative tasks. Capacity to perform functions will need to be developed. • NGOs are an appropriate partner providing they are trusted by communities and rigorous monitoring and accountability mechanisms are built in. • There is a need for a private sector service provider to handle payments based on a tender process. • Capacity issues mean the framework should focus on a small number of clear interventions. • The UN’s optimum role is one of overall coordination, capacity building, advocacy and fundraising rather than direct implementation. 71

SESSION 4: ESTABLISHING A SOCIAL PROTECTION FRAMEWORK: DESIGN ISSUES 72

SESSION 4: ESTABLISHING A SOCIAL PROTECTION FRAMEWORK: DESIGN ISSUES 72

1. Targeting approaches and mechanisms 2. Attaching conditions 3. Supporting people of working age – ‘graduation’ programmes, public works and unconditional transfers 4. Dealing with Covariate Shocks 73

1. Targeting approaches and mechanisms 2. Attaching conditions 3. Supporting people of working age – ‘graduation’ programmes, public works and unconditional transfers 4. Dealing with Covariate Shocks 73

4. Design Issues 4. 1 Targeting Approaches • Targeting approaches: during programme and policy design, establish a rationale and criteria of eligibility for those who should receive a benefit • Targeting mechanisms: how to operationalise these approaches - to identify and reach the targeted beneficiaries. Poverty Targeted Approach Inclusive Lifecycle Approach • Rational – to target scarce • Rationale – programmes accessible to everyone resources at those living in within an eligible category of the population that is poverty. considered vulnerable, directing resources to • Focus on household units, tackling the main lifecycle risks. usually those that are “poor’. • Focus on the individual (who is still part of a • Seeks to tackle the symptom, household/family unit) which is poverty itself: in • Tries to tackle the causes of poverty, recognising other words, all those who that people face risks and challenges that vary are suffering from the across the lifecycle and that these contribute to symptom should receive making them more vulnerable to falling into similar treatment. poverty. As such it attempts to capture more diffuse notions of vulnerability or social exclusion 74

4. Design Issues 4. 1 Targeting Approaches • Targeting approaches: during programme and policy design, establish a rationale and criteria of eligibility for those who should receive a benefit • Targeting mechanisms: how to operationalise these approaches - to identify and reach the targeted beneficiaries. Poverty Targeted Approach Inclusive Lifecycle Approach • Rational – to target scarce • Rationale – programmes accessible to everyone resources at those living in within an eligible category of the population that is poverty. considered vulnerable, directing resources to • Focus on household units, tackling the main lifecycle risks. usually those that are “poor’. • Focus on the individual (who is still part of a • Seeks to tackle the symptom, household/family unit) which is poverty itself: in • Tries to tackle the causes of poverty, recognising other words, all those who that people face risks and challenges that vary are suffering from the across the lifecycle and that these contribute to symptom should receive making them more vulnerable to falling into similar treatment. poverty. As such it attempts to capture more diffuse notions of vulnerability or social exclusion 74

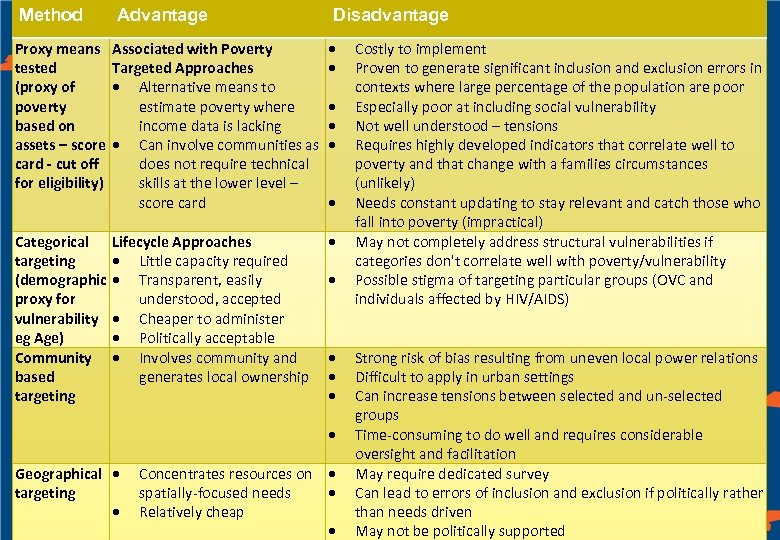

Method Advantage Disadvantage Proxy means tested (proxy of poverty based on assets – score card - cut off for eligibility) Associated with Poverty Targeted Approaches Alternative means to estimate poverty where income data is lacking Can involve communities as does not require technical skills at the lower level – score card Categorical targeting (demographic proxy for vulnerability eg Age) Community based targeting Lifecycle Approaches Little capacity required Transparent, easily understood, accepted Cheaper to administer Politically acceptable Involves community and generates local ownership Costly to implement Proven to generate significant inclusion and exclusion errors in contexts where large percentage of the population are poor Especially poor at including social vulnerability Not well understood – tensions Requires highly developed indicators that correlate well to poverty and that change with a families circumstances (unlikely) Needs constant updating to stay relevant and catch those who fall into poverty (impractical) May not completely address structural vulnerabilities if categories don't correlate well with poverty/vulnerability Possible stigma of targeting particular groups (OVC and individuals affected by HIV/AIDS) 4. Design Issues 4. 1 Targeting Methods Geographical targeting Concentrates resources on spatially-focused needs Relatively cheap Strong risk of bias resulting from uneven local power relations Difficult to apply in urban settings Can increase tensions between selected and un-selected groups Time-consuming to do well and requires considerable oversight and facilitation May require dedicated survey Can lead to errors of inclusion and exclusion if politically rather than needs driven 75 May not be politically supported

Method Advantage Disadvantage Proxy means tested (proxy of poverty based on assets – score card - cut off for eligibility) Associated with Poverty Targeted Approaches Alternative means to estimate poverty where income data is lacking Can involve communities as does not require technical skills at the lower level – score card Categorical targeting (demographic proxy for vulnerability eg Age) Community based targeting Lifecycle Approaches Little capacity required Transparent, easily understood, accepted Cheaper to administer Politically acceptable Involves community and generates local ownership Costly to implement Proven to generate significant inclusion and exclusion errors in contexts where large percentage of the population are poor Especially poor at including social vulnerability Not well understood – tensions Requires highly developed indicators that correlate well to poverty and that change with a families circumstances (unlikely) Needs constant updating to stay relevant and catch those who fall into poverty (impractical) May not completely address structural vulnerabilities if categories don't correlate well with poverty/vulnerability Possible stigma of targeting particular groups (OVC and individuals affected by HIV/AIDS) 4. Design Issues 4. 1 Targeting Methods Geographical targeting Concentrates resources on spatially-focused needs Relatively cheap Strong risk of bias resulting from uneven local power relations Difficult to apply in urban settings Can increase tensions between selected and un-selected groups Time-consuming to do well and requires considerable oversight and facilitation May require dedicated survey Can lead to errors of inclusion and exclusion if politically rather than needs driven 75 May not be politically supported

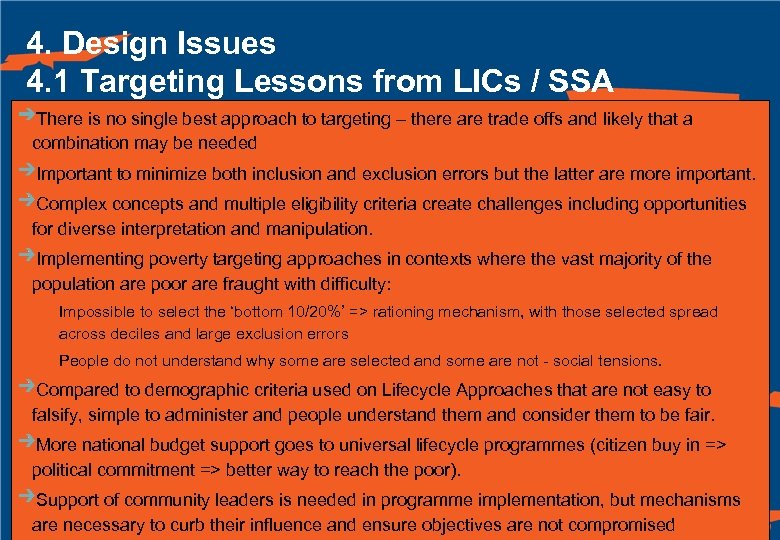

4. Design Issues 4. 1 Targeting Lessons from LICs / SSA There is no single best approach to targeting – there are trade offs and likely that a combination may be needed Important to minimize both inclusion and exclusion errors but the latter are more important. Complex concepts and multiple eligibility criteria create challenges including opportunities for diverse interpretation and manipulation. Implementing poverty targeting approaches in contexts where the vast majority of the population are poor are fraught with difficulty: § Impossible to select the ‘bottom 10/20%’ => rationing mechanism, with those selected spread across deciles and large exclusion errors § People do not understand why some are selected and some are not - social tensions. Compared to demographic criteria used on Lifecycle Approaches that are not easy to falsify, simple to administer and people understand them and consider them to be fair. More national budget support goes to universal lifecycle programmes (citizen buy in => political commitment => better way to reach the poor). Support of community leaders is needed in programme implementation, but mechanisms 76 are necessary to curb their influence and ensure objectives are not compromised

4. Design Issues 4. 1 Targeting Lessons from LICs / SSA There is no single best approach to targeting – there are trade offs and likely that a combination may be needed Important to minimize both inclusion and exclusion errors but the latter are more important. Complex concepts and multiple eligibility criteria create challenges including opportunities for diverse interpretation and manipulation. Implementing poverty targeting approaches in contexts where the vast majority of the population are poor are fraught with difficulty: § Impossible to select the ‘bottom 10/20%’ => rationing mechanism, with those selected spread across deciles and large exclusion errors § People do not understand why some are selected and some are not - social tensions. Compared to demographic criteria used on Lifecycle Approaches that are not easy to falsify, simple to administer and people understand them and consider them to be fair. More national budget support goes to universal lifecycle programmes (citizen buy in => political commitment => better way to reach the poor). Support of community leaders is needed in programme implementation, but mechanisms 76 are necessary to curb their influence and ensure objectives are not compromised

4. Design Issues 4. 2 Attaching Conditions CCT: families perform some activity in order to continue to receive benefits – sending children to school or attending health clinics. • Lack of conclusive evidence that implementing conditions has any impact on human development compared to what would have been achieved through the CT alone • See similar investments made on unconditional programmes • High costs of monitoring conditionality • Imposing conditions where so many barriers to accessing services exist risks penalising households, over-stretching services and reducing quality. Don’t impose conditions, incentivise families 77

4. Design Issues 4. 2 Attaching Conditions CCT: families perform some activity in order to continue to receive benefits – sending children to school or attending health clinics. • Lack of conclusive evidence that implementing conditions has any impact on human development compared to what would have been achieved through the CT alone • See similar investments made on unconditional programmes • High costs of monitoring conditionality • Imposing conditions where so many barriers to accessing services exist risks penalising households, over-stretching services and reducing quality. Don’t impose conditions, incentivise families 77

4. Design Issues 4. 3 Meeting the needs of those with labour capacity Limitations with most LIPW • Prerequisites for a successful LIPW with social protection objectives often not met (employment insufficient duration; timing doenst coincide with periods of need/labour availability; need repeated support year on year; works condition should not impact negatively on the household (time away from livelihoods/child labour) Alternatives: • Graduation Programme • Unconditional Transfers • Transfers to others in the family • Limited quality and sustainability of work outputs • Additional costs of the work component (especially when benefits not sustained) • Not addressing underlying causes of vulnerability - abilty to access long-term, productive livelihood opportunities 78

4. Design Issues 4. 3 Meeting the needs of those with labour capacity Limitations with most LIPW • Prerequisites for a successful LIPW with social protection objectives often not met (employment insufficient duration; timing doenst coincide with periods of need/labour availability; need repeated support year on year; works condition should not impact negatively on the household (time away from livelihoods/child labour) Alternatives: • Graduation Programme • Unconditional Transfers • Transfers to others in the family • Limited quality and sustainability of work outputs • Additional costs of the work component (especially when benefits not sustained) • Not addressing underlying causes of vulnerability - abilty to access long-term, productive livelihood opportunities 78

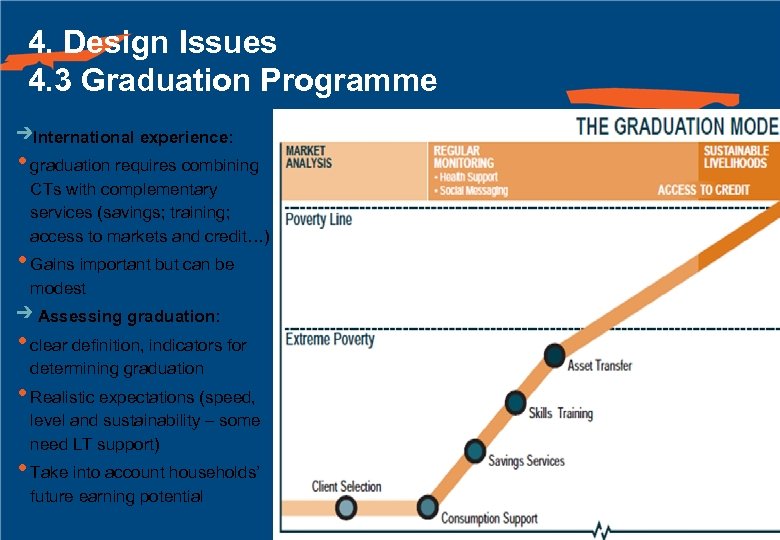

4. Design Issues 4. 3 Graduation Programme International experience: • graduation requires combining CTs with complementary services (savings; training; access to markets and credit…) • Gains important but can be modest Assessing graduation: • clear definition, indicators for determining graduation • Realistic expectations (speed, level and sustainability – some need LT support) • Take into account households’ future earning potential 79

4. Design Issues 4. 3 Graduation Programme International experience: • graduation requires combining CTs with complementary services (savings; training; access to markets and credit…) • Gains important but can be modest Assessing graduation: • clear definition, indicators for determining graduation • Realistic expectations (speed, level and sustainability – some need LT support) • Take into account households’ future earning potential 79

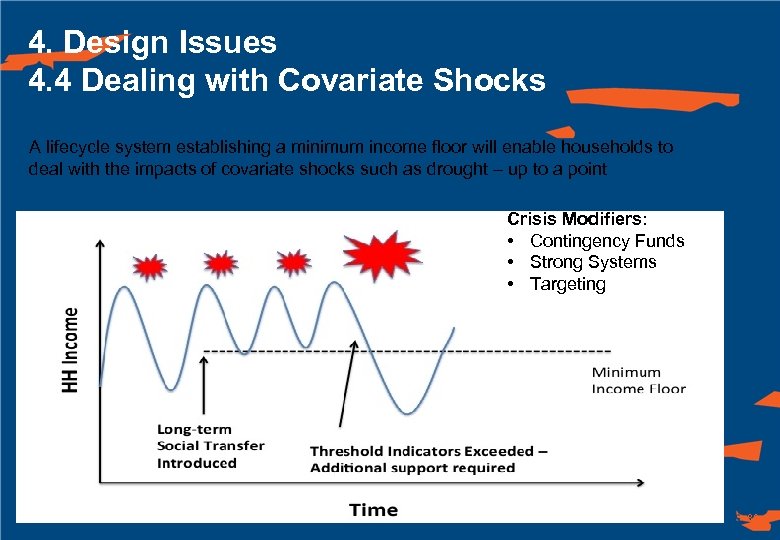

4. Design Issues 4. 4 Dealing with Covariate Shocks A lifecycle system establishing a minimum income floor will enable households to deal with the impacts of covariate shocks such as drought – up to a point Crisis Modifiers: • Contingency Funds • Strong Systems • Targeting 80

4. Design Issues 4. 4 Dealing with Covariate Shocks A lifecycle system establishing a minimum income floor will enable households to deal with the impacts of covariate shocks such as drought – up to a point Crisis Modifiers: • Contingency Funds • Strong Systems • Targeting 80

SESSION 5: A SOCIAL PROTECTION FRAMEWORK FOR SOMALIA 81

SESSION 5: A SOCIAL PROTECTION FRAMEWORK FOR SOMALIA 81

1. Principles, vision and approach 2. Programme options 82

1. Principles, vision and approach 2. Programme options 82

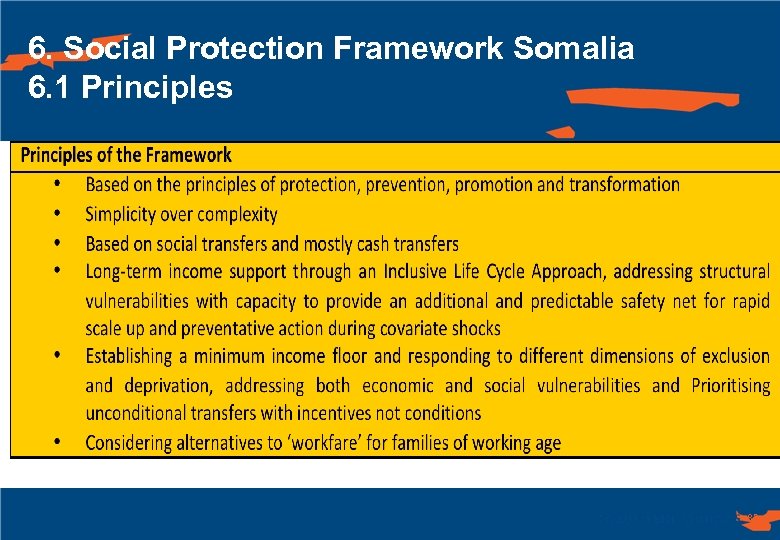

6. Social Protection Framework Somalia 6. 1 Principles 83

6. Social Protection Framework Somalia 6. 1 Principles 83

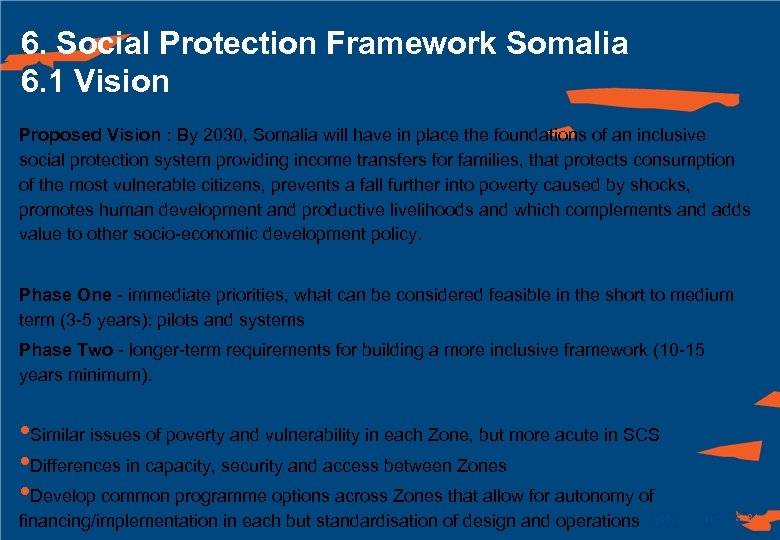

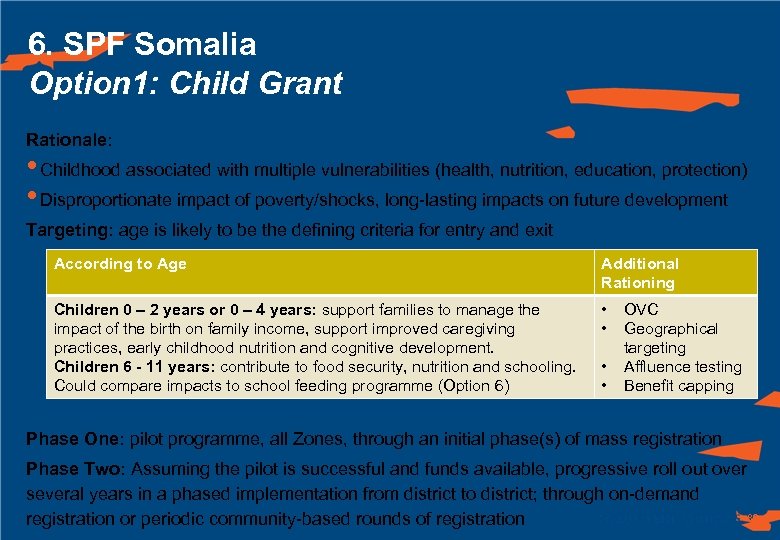

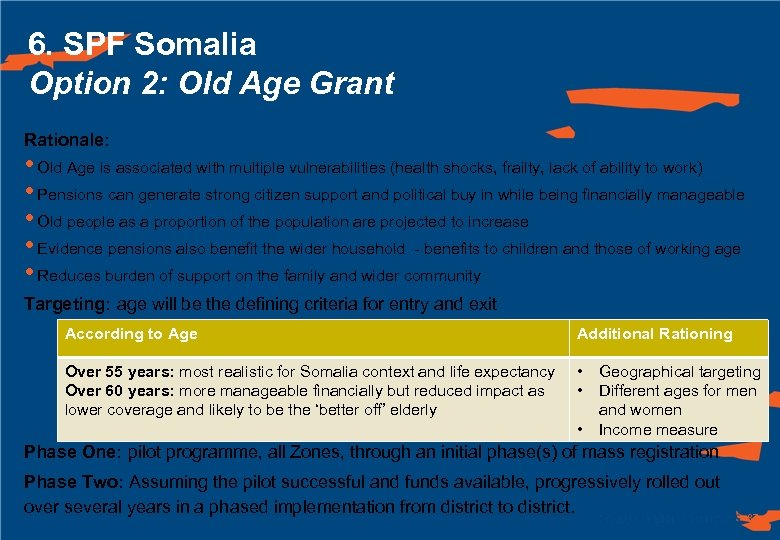

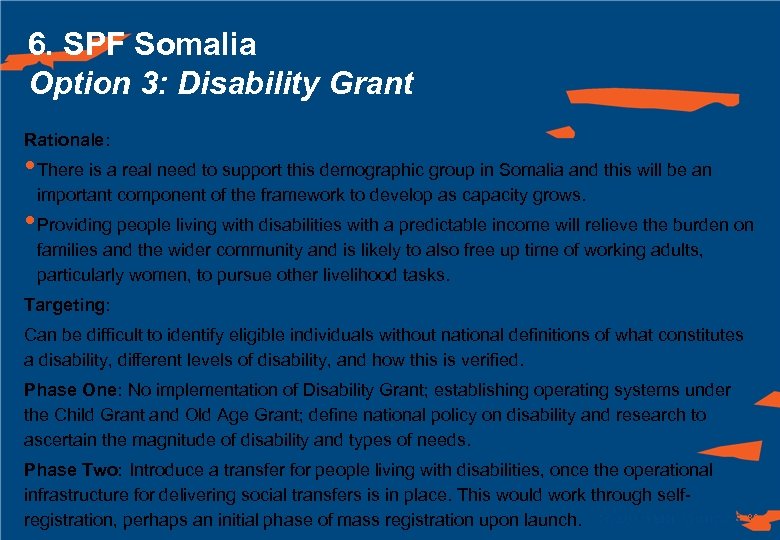

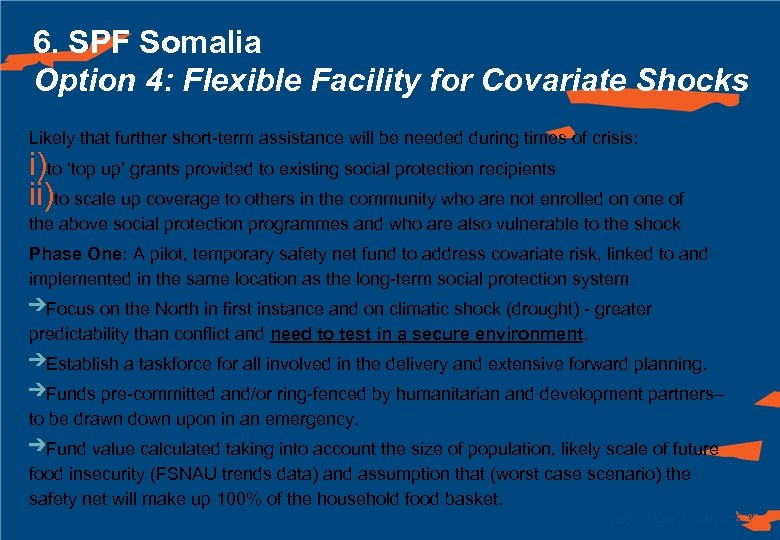

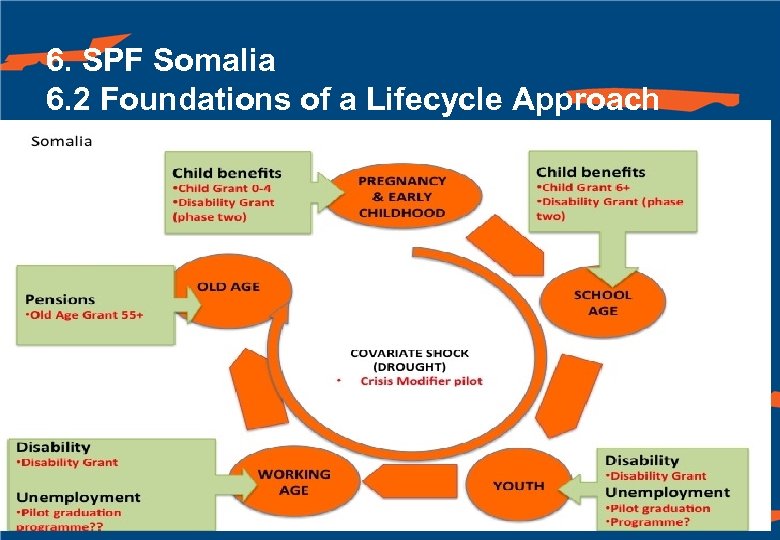

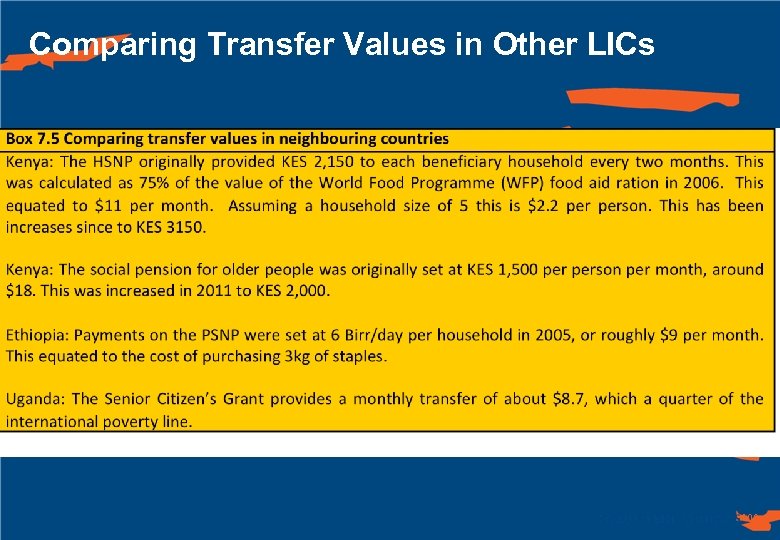

6. Social Protection Framework Somalia 6. 1 Vision Proposed Vision : By 2030, Somalia will have in place the foundations of an inclusive social protection system providing income transfers for families, that protects consumption of the most vulnerable citizens, prevents a fall further into poverty caused by shocks, promotes human development and productive livelihoods and which complements and adds value to other socio-economic development policy. Phase One - immediate priorities, what can be considered feasible in the short to medium term (3 -5 years): pilots and systems Phase Two - longer-term requirements for building a more inclusive framework (10 -15 years minimum). • Similar issues of poverty and vulnerability in each Zone, but more acute in SCS • Differences in capacity, security and access between Zones • Develop common programme options across Zones that allow for autonomy of financing/implementation in each but standardisation of design and operations 84