c72518e7ffdf9c041b3e9d746a7acc97.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 63

Deirdre Kann NWS Albuquerque Some material in this presentation is based on earlier presentations prepared by: Randall Dole and Robert S Webb NOAA OAR, Earth System Research Laboratory (ESRL) David Gutzler, UNM, provided additional material and collaboration Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – March 2011 1

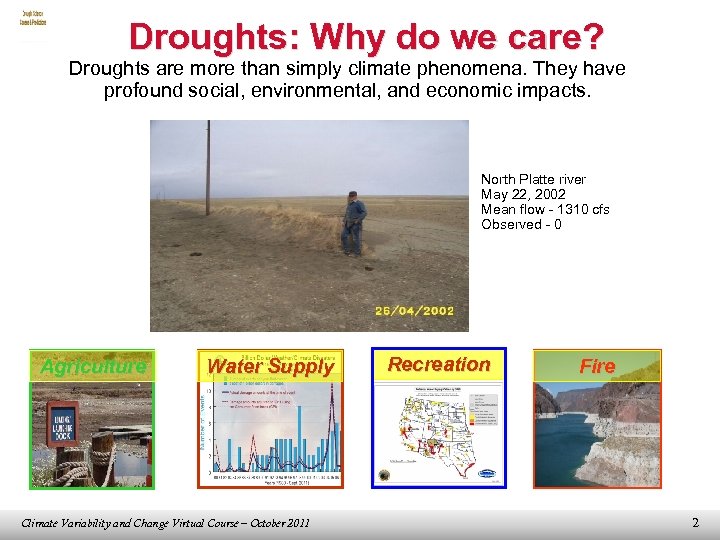

Droughts: Why do we care? Droughts are more than simply climate phenomena. They have profound social, environmental, and economic impacts. North Platte river May 22, 2002 Mean flow - 1310 cfs Observed - 0 Agriculture Water Supply Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 Recreation Fire 2

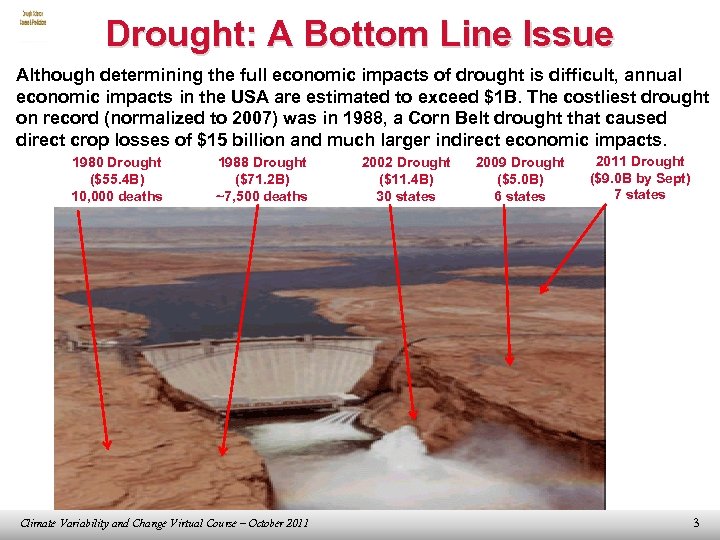

Drought: A Bottom Line Issue Although determining the full economic impacts of drought is difficult, annual economic impacts in the USA are estimated to exceed $1 B. The costliest drought on record (normalized to 2007) was in 1988, a Corn Belt drought that caused direct crop losses of $15 billion and much larger indirect economic impacts. 1980 Drought ($55. 4 B) 10, 000 deaths 1988 Drought ($71. 2 B) ~7, 500 deaths Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 2002 Drought ($11. 4 B) 30 states 2009 Drought ($5. 0 B) 6 states 2011 Drought ($9. 0 B by Sept) 7 states 3

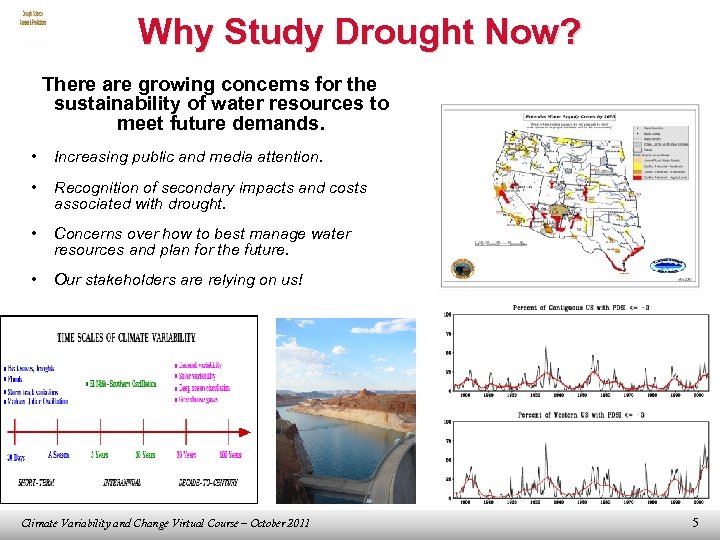

Why Study Drought Now? There are growing concerns for the sustainability of water resources to meet future demands. • Increasing public and media attention. • Recognition of secondary impacts and costs associated with drought. • Concerns over how to best manage water resources and plan for the future. • Our stakeholders are relying on us! Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 5

Objectives of this Lesson • A brief review of drought definitions, climatology and monitoring tools • Drought Causes – what are the mechanisms that maintain drought across seasons and years? • Drought Predictability – are there methodologies in place to help us forecast and prepare for extended droughts? Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 6

What is Drought? There is no unique definition. National Drought Policy Commission: “ A persistent abnormal moisture deficiency having adverse impacts on vegetation, animals, and people. ” Key ingredients: Persistent water deficiency + adverse impacts Meteorological - Rainfall deficit. Agricultural - Topsoil moisture deficit. Agricultural impacts. Hydrological - Surface or sub-surface water supply shortage. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 7

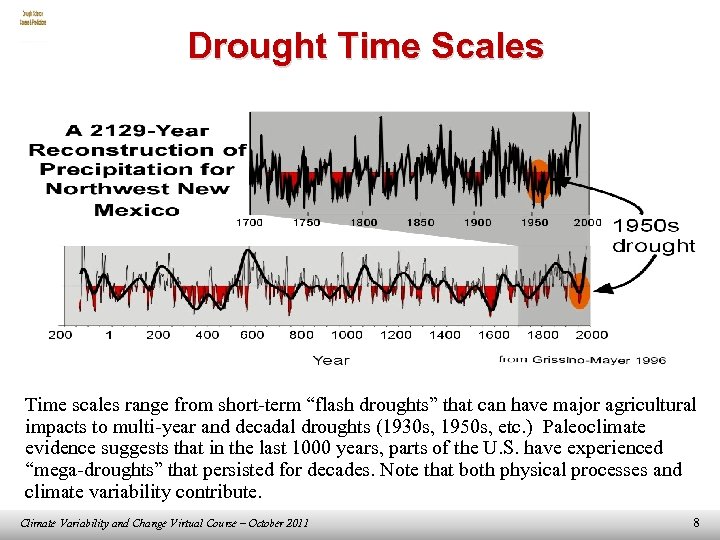

Drought Time Scales Time scales range from short-term “flash droughts” that can have major agricultural impacts to multi-year and decadal droughts (1930 s, 1950 s, etc. ) Paleoclimate evidence suggests that in the last 1000 years, parts of the U. S. have experienced “mega-droughts” that persisted for decades. Note that both physical processes and climate variability contribute. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 8

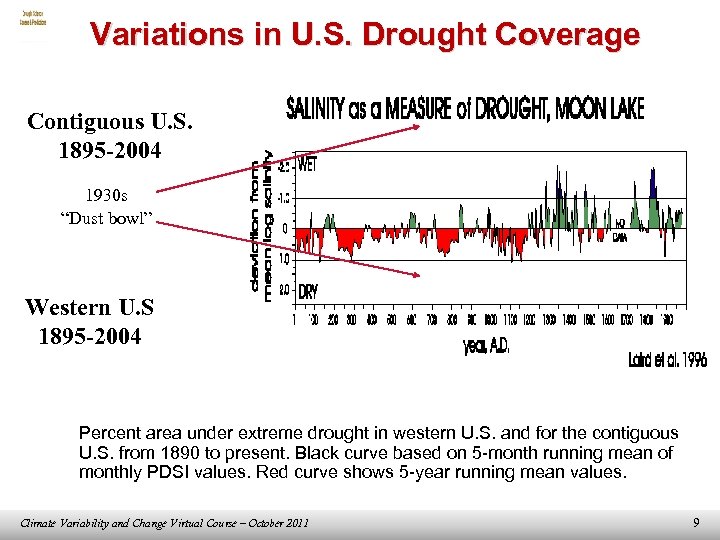

Variations in U. S. Drought Coverage Contiguous U. S. 1895 -2004 1930 s “Dust bowl” Western U. S 1895 -2004 Percent area under extreme drought in western U. S. and for the contiguous U. S. from 1890 to present. Black curve based on 5 -month running mean of monthly PDSI values. Red curve shows 5 -year running mean values. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 9

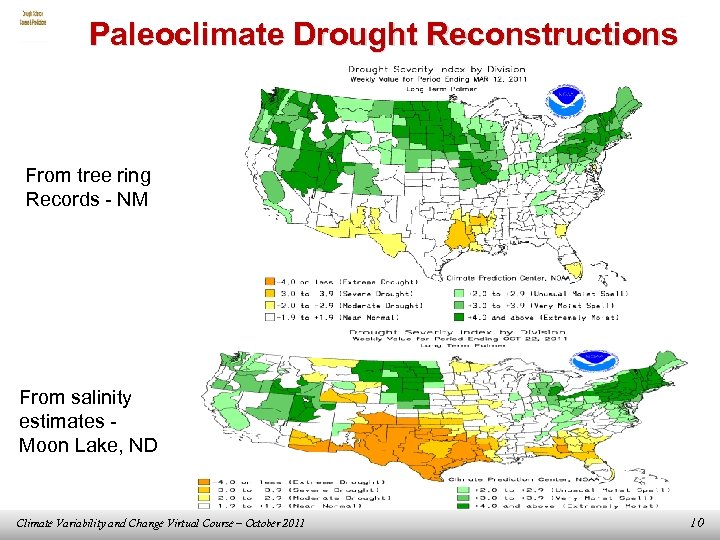

Paleoclimate Drought Reconstructions From tree ring Records - NM From salinity estimates Moon Lake, ND Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 10

U. S. Drought and Climate – Take Home Points • Drought is a recurrent part of the U. S. climate. At least part of the country is in drought at any given time, averaging about 20% of the country and ranging from roughly 5% to 80%. • Widespread drought can affect the country for many years, such as during the 1930 s “Dust Bowl” period. • For the continental U. S. , the most extensive U. S. drought in the modern observational record occurred from 1933 to 1938. In July 1934, 80% of the U. S. was gripped by moderate or greater drought and 63% was experiencing severe to extreme drought. During 1953 -1957, severe drought covered up to 50% of the country. • Paleoclimate records depict multi-decadal droughts far greater in severity than anything observed in modern instrumental records Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 11

Quantitative Drought Measures Numerous drought indices - all have strengths and shortcomings. Among the most common: • Percent of normal precipitation (problem: non-normal distribution) • Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) - responds slowly • Standardized precipitation index, SPI (only considers P) • Crop Moisture Index, CMI - simple water balance, top layer • Deciles or quintiles - Requires fairly long, stable climate record There is a strong need to develop improved, regionally-dependent drought measures that are more directly connected to impacts. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 12

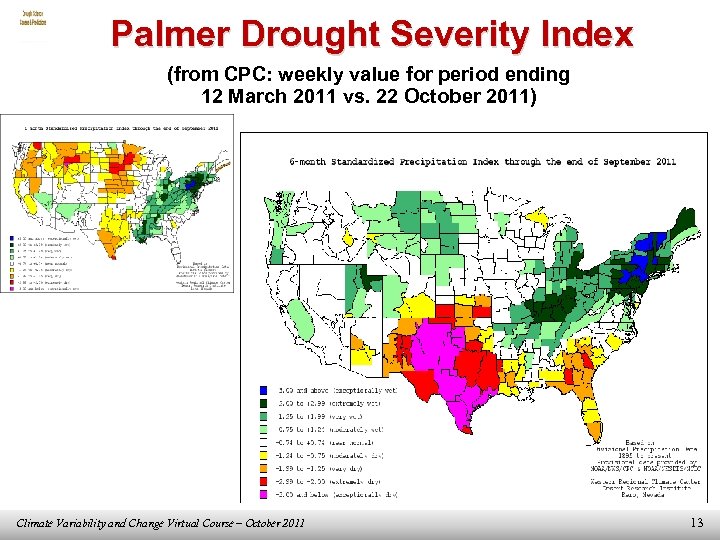

Palmer Drought Severity Index (from CPC: weekly value for period ending 12 March 2011 vs. 22 October 2011) Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 13

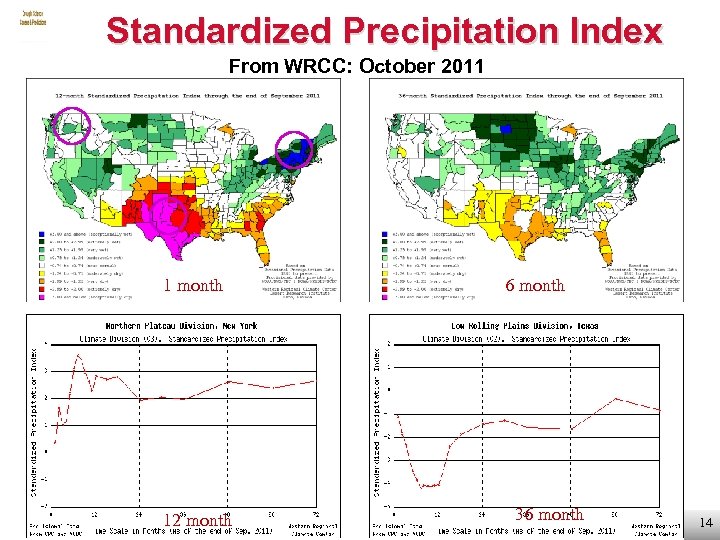

Standardized Precipitation Index From WRCC: October 2011 1 month 12 month 6 month 36 month 14

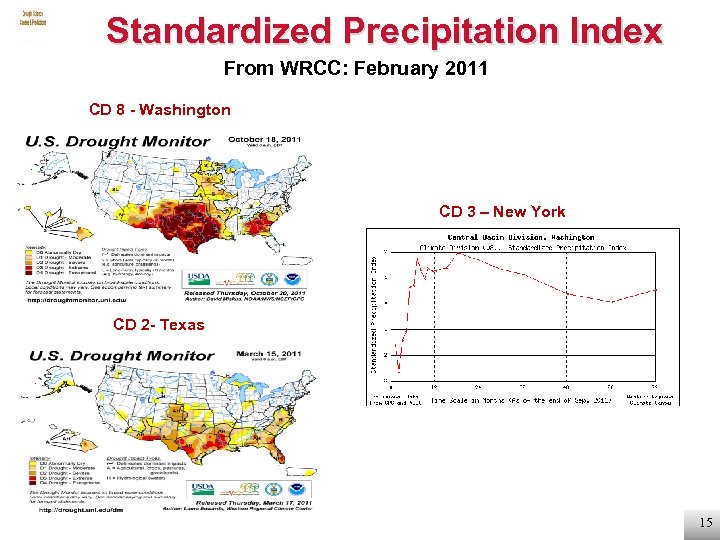

Standardized Precipitation Index From WRCC: February 2011 CD 8 - Washington CD 3 – New York CD 2 - Texas 15

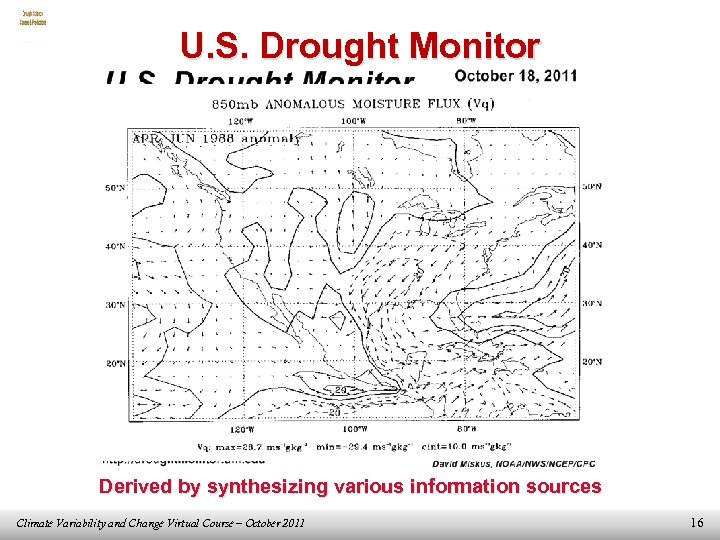

U. S. Drought Monitor Derived by synthesizing various information sources Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 16

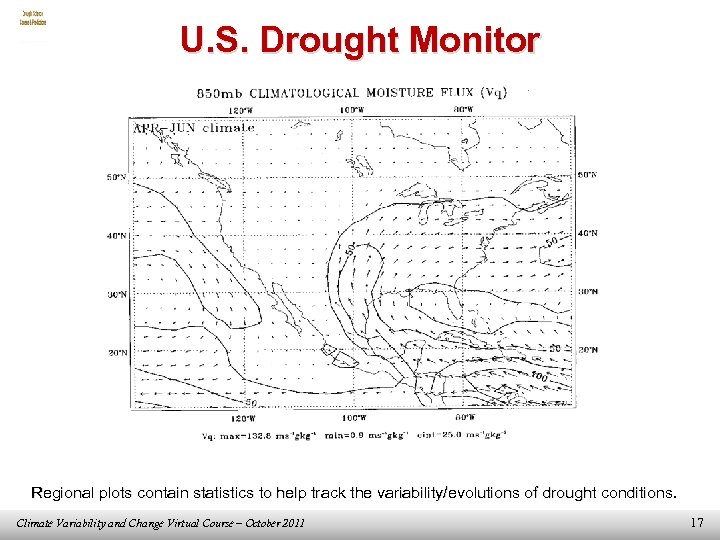

U. S. Drought Monitor Regional plots contain statistics to help track the variability/evolutions of drought conditions. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 17

Poll Question #1 Definitions of drought vary, but drought is best defined as: a. A physical phenomenon b. A result of climate variability c. A negative socioeconomic impact d. All of the above Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 18

Drought Monitoring – Take Home Points • There is no unique definition of drought, nor is there one “best” drought index. All have strengths and limitations. • Consider impacts - the “human dimension”. • Keep in mind the types of drought and their lag relationships. • Be wary of calling a premature end to the drought. Hydrological impacts may persist well after precipitation has returned to near normal. • Key factors to monitor in drought include severity, longevity, spatial pattern and scale. Impacts will vary regionally and depend strongly on the time of year. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 19

Drought Causes You, as the local office climate expert, might be asked, “What is the cause of this drought? ” And your answer is … Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 20

“A persistent upper-level ridge over the region. ” Persistent upper-level ridges are often identified as the proximate cause of drought conditions. Specific physical factors that help to produce droughts include: anomalous subsidence, changes in horizontal moisture transports, and shifts in the storm tracks. Ridges effect all these factors. Subsidence occurs downshear of ridge axis. Subsidence suppresses precipitation in several ways: • Adiabatic warming inhibits large-scale condensation • Mid-tropospheric warming produces static stabilization • Low-level divergence inhibits moisture convergence Even weak subsidence can strongly suppress precipitation. In addition, storm tracks are usually diverted around ridges. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 21

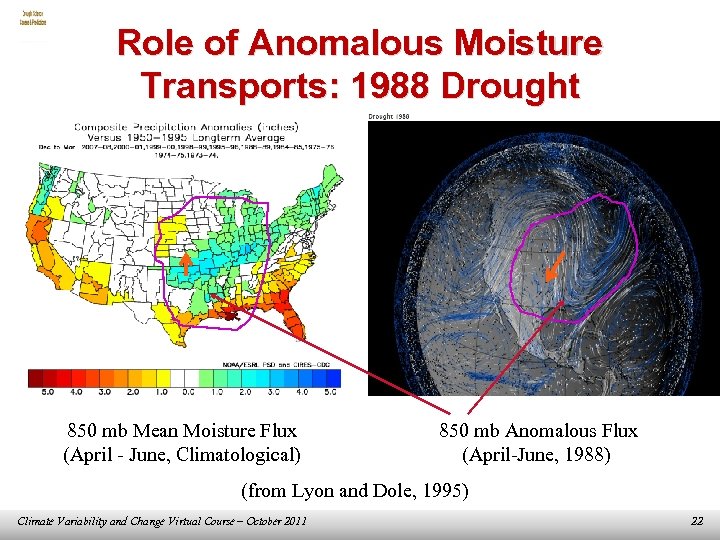

Role of Anomalous Moisture Transports: 1988 Drought 850 mb Mean Moisture Flux (April - June, Climatological) 850 mb Anomalous Flux (April-June, 1988) (from Lyon and Dole, 1995) Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 22

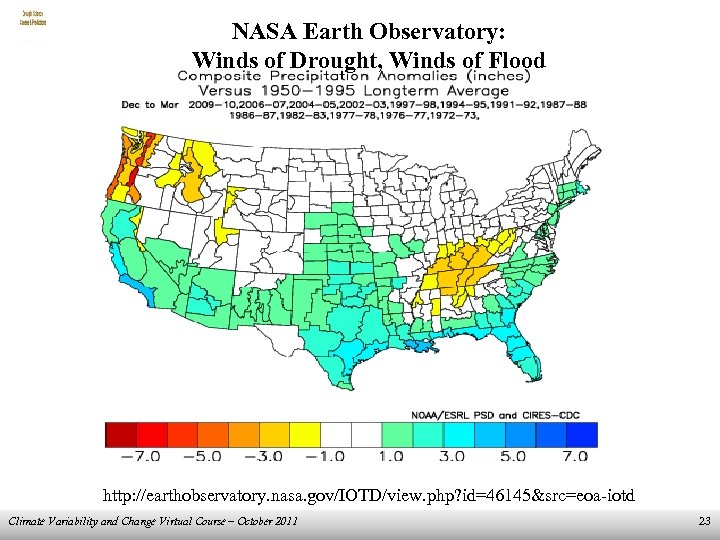

NASA Earth Observatory: Winds of Drought, Winds of Flood http: //earthobservatory. nasa. gov/IOTD/view. php? id=46145&src=eoa-iotd Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 23

Next Question: What is the cause of this persistent ridge pattern? Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 24

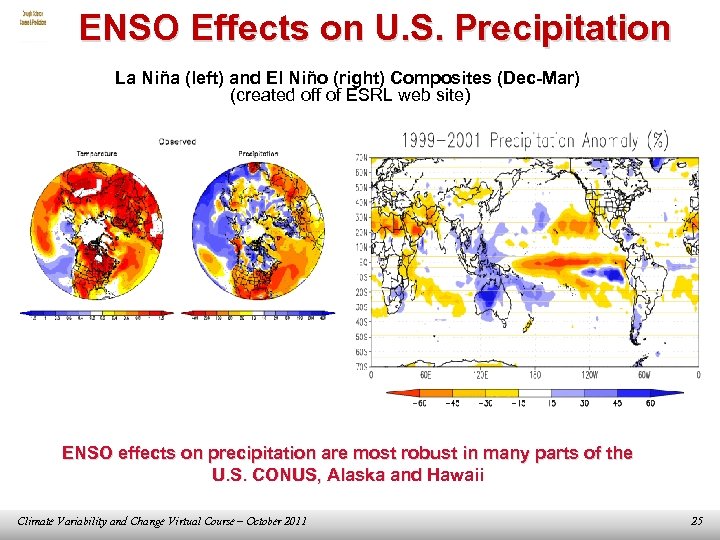

ENSO Effects on U. S. Precipitation La Niña (left) and El Niño (right) Composites (Dec-Mar) (created off of ESRL web site) ENSO effects on precipitation are most robust in many parts of the U. S. CONUS, Alaska and Hawaii Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 25

Poll True or False: All areas across the U. S. CONUS can attribute a majority of their observed droughts to the ENSO cycle. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 26

What are the mechanisms that cause and maintain drought? Can atmospheric general circulation models depict the role of SST forcing and landatmosphere feedbacks in the development and maintenance of drought? Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 27

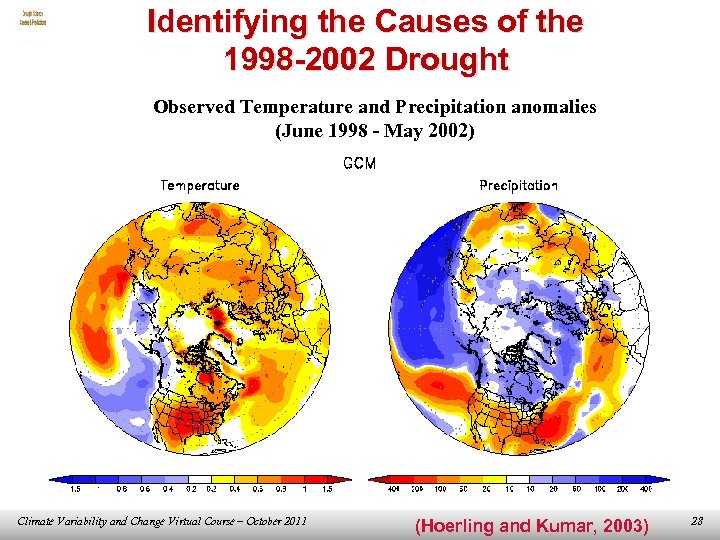

Identifying the Causes of the 1998 -2002 Drought Observed Temperature and Precipitation anomalies (June 1998 - May 2002) Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 (Hoerling and Kumar, 2003) 28

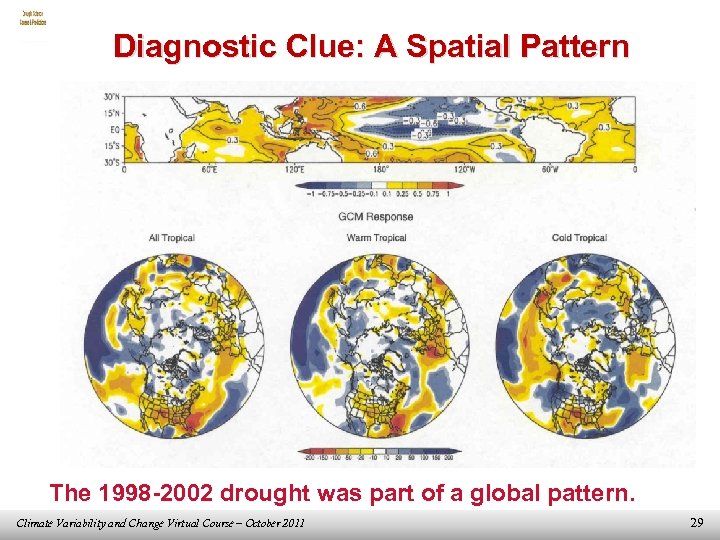

Diagnostic Clue: A Spatial Pattern The 1998 -2002 drought was part of a global pattern. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 29

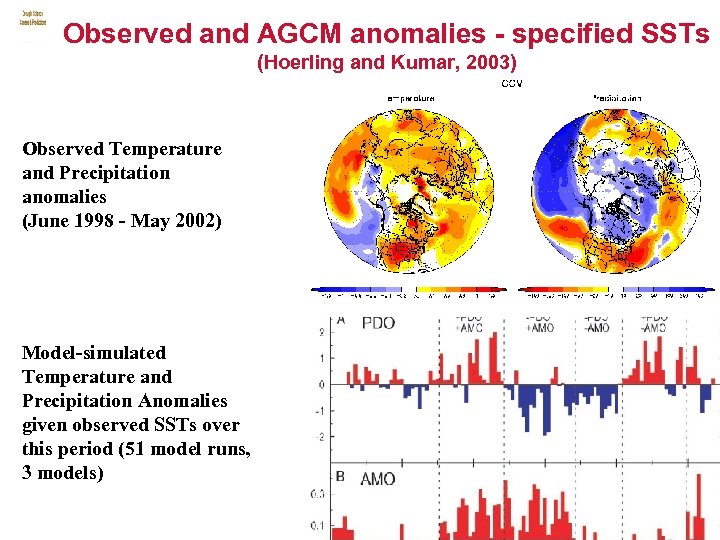

Observed and AGCM anomalies - specified SSTs (Hoerling and Kumar, 2003) Observed Temperature and Precipitation anomalies (June 1998 - May 2002) Model-simulated Temperature and Precipitation Anomalies given observed SSTs over this period (51 model runs, 3 models) 30

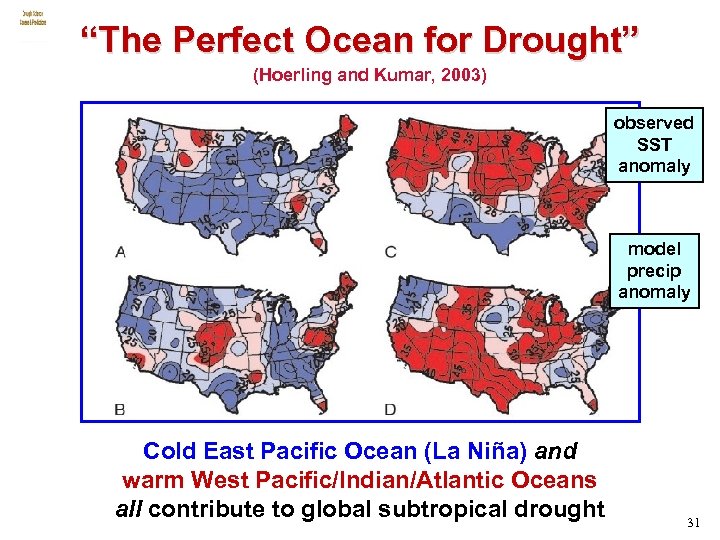

“The Perfect Ocean for Drought” (Hoerling and Kumar, 2003) observed SST anomaly model precip anomaly Cold East Pacific Ocean (La Niña) and warm West Pacific/Indian/Atlantic Oceans all contribute to global subtropical drought 31

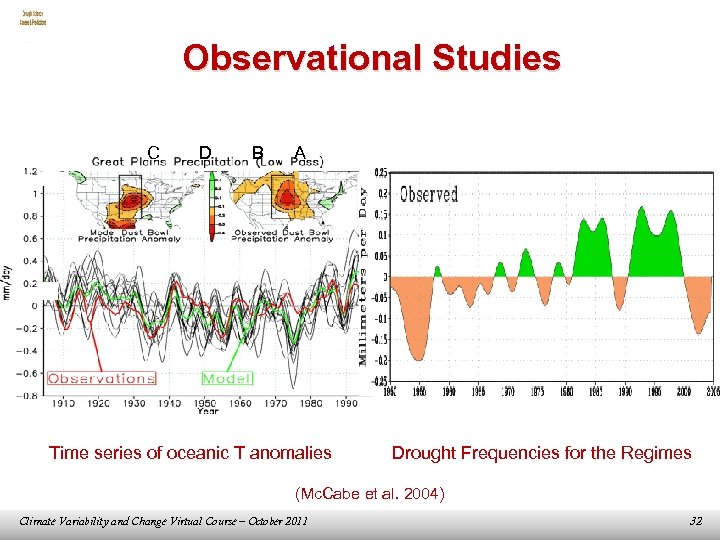

Observational Studies C D B A Time series of oceanic T anomalies Drought Frequencies for the Regimes (Mc. Cabe et al. 2004) Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 32

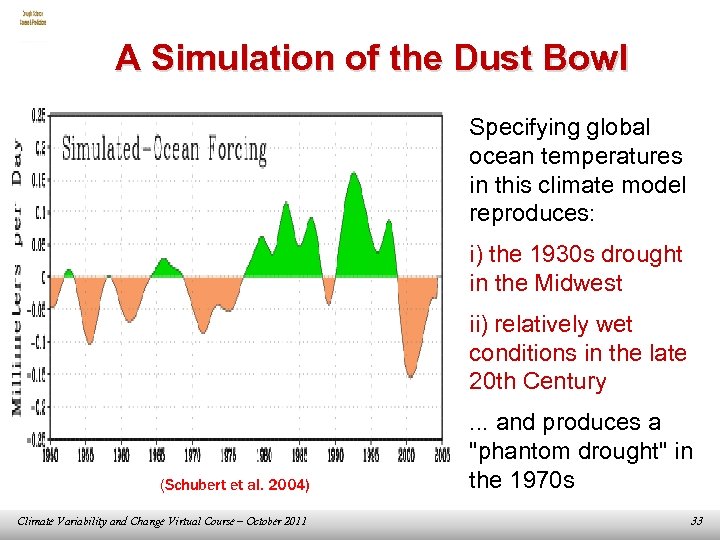

A Simulation of the Dust Bowl Specifying global ocean temperatures in this climate model reproduces: i) the 1930 s drought in the Midwest ii) relatively wet conditions in the late 20 th Century (Schubert et al. 2004) Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 . . . and produces a "phantom drought" in the 1970 s 33

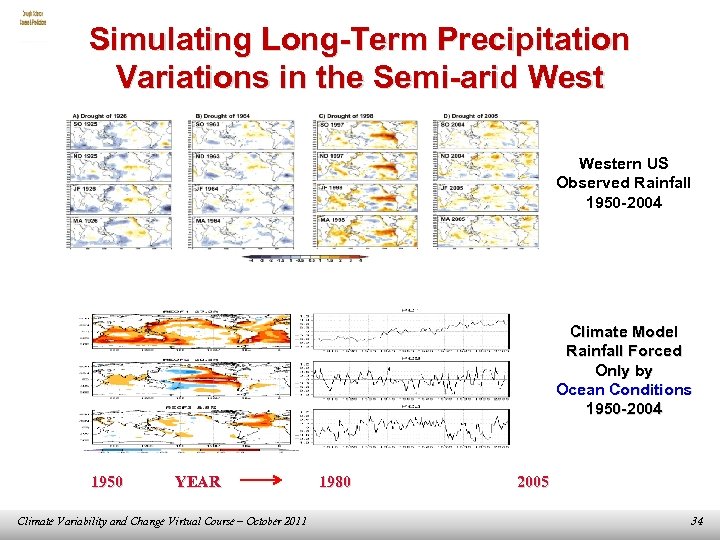

Simulating Long-Term Precipitation Variations in the Semi-arid Western US Observed Rainfall 1950 -2004 Climate Model Rainfall Forced Only by Ocean Conditions 1950 -2004 1950 YEAR Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 1980 2005 34

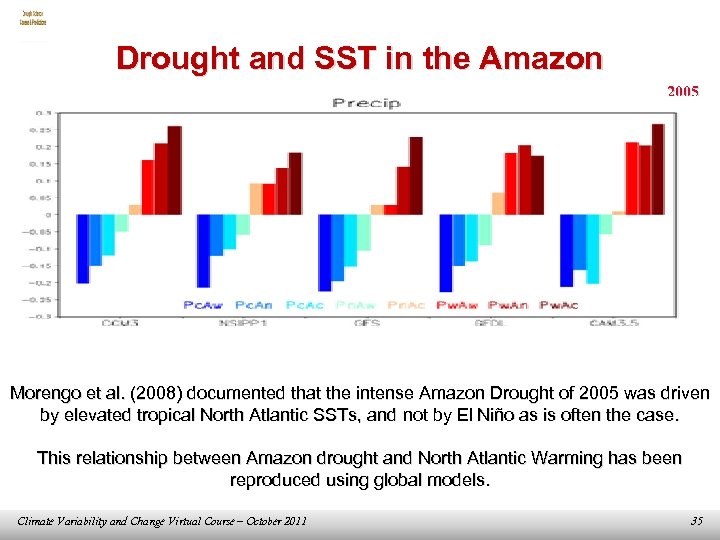

Drought and SST in the Amazon 2005 Morengo et al. (2008) documented that the intense Amazon Drought of 2005 was driven by elevated tropical North Atlantic SSTs, and not by El Niño as is often the case. This relationship between Amazon drought and North Atlantic Warming has been reproduced using global models. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 35

The Drought Working Group of the U. S. Climate Variability and Predictability Research Program (CLIVAR) was formed to provide guidance on research for improving monitoring tools and prediction of long-term drought. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 36

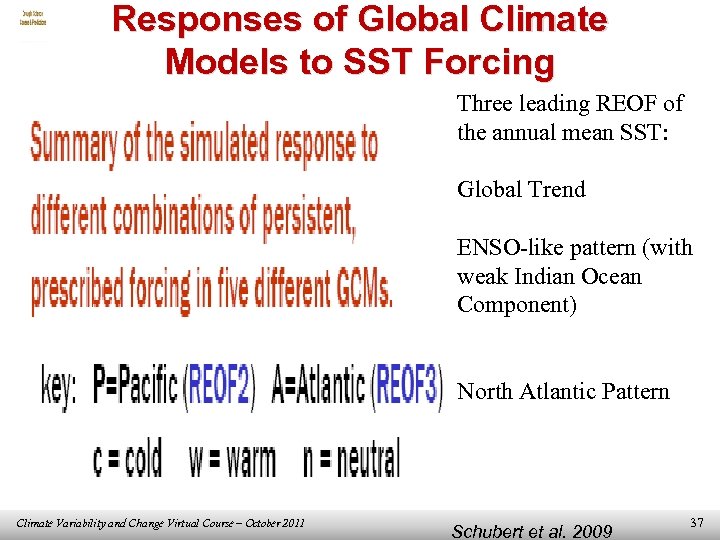

Responses of Global Climate Models to SST Forcing Three leading REOF of the annual mean SST: Global Trend ENSO-like pattern (with weak Indian Ocean Component) North Atlantic Pattern Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 Schubert et al. 2009 37

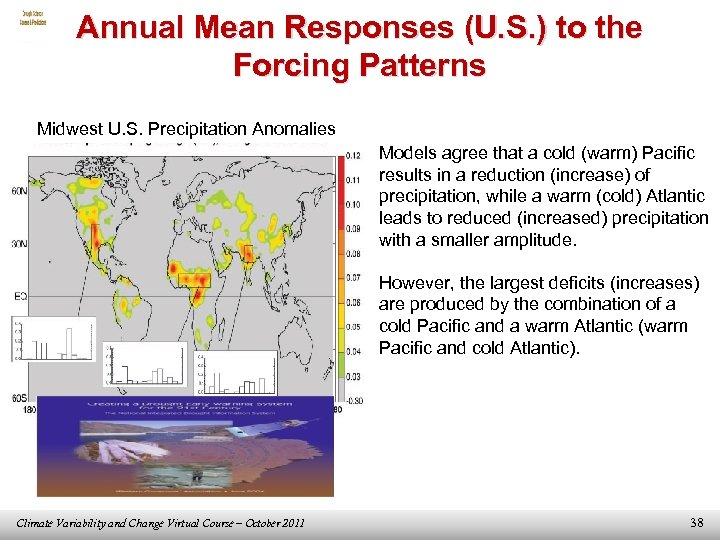

Annual Mean Responses (U. S. ) to the Forcing Patterns Midwest U. S. Precipitation Anomalies Models agree that a cold (warm) Pacific results in a reduction (increase) of precipitation, while a warm (cold) Atlantic leads to reduced (increased) precipitation with a smaller amplitude. However, the largest deficits (increases) are produced by the combination of a cold Pacific and a warm Atlantic (warm Pacific and cold Atlantic). Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 38

Soil Moisture Feedback • Soil moisture can influence the weather through its impact on evaporation and other surface energy fluxes. • Soil moisture anomalies can persist for months. • Because of a lack of observations, models are often used to investigate the feedback mechanisms. • Feedbacks between the land atmosphere have been shown to be an important component of drought persistence into the summer. • Several studies have shown that while SST anomalies contribute to the development of drought, particularly in the cold season, soil moisture deficits act to extend the drought into summer. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 39

Coupling Between Soil Moisture and Precipitation Koster et al. (2004) used multiple modeling runs to identify locations at which soil moisture anomalies have a substantial impact on precipitation. These are referred to as “hot spots” and include the Great Plains. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 40

Other Factors • Random component - “Droughts happen” (or don’t happen!) • Other ocean forcing (extratropical, tropical Atlantic) • Other large scale modes of variability beyond ENSO (NAO/AO) • Land surface/soil moisture/vegetation feedbacks. • Not addressed here: aerosols, solar variations, etc. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 41

Poll Sea Surface Temperatures in which ocean basin provides the dominant remote forcing for U. S. Drought? a. Tropical Indian b. Northern Extratropical Pacific c. Northern Extratropical Atlantic d. Tropical Pacific Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 42

Drought Causes: Take Home Points • Identifying drought causes requires knowledge of the processes that produce precipitation locally and how they are influenced by climate variations. • Drought time scales and patterns provide important clues to causes. • Short-term droughts - internal dynamics; longer-term, forcing more likely. • Most systematic signals are associated with tropical Pacific/Indian Ocean SST sectors, especially in cold season. Emerging evidence that Atlantic SSTs also play a role, most likely in warm season (modulation of Bermuda high, moisture fluxes). • Role of land surface is less systematic. Not an initial cause, but may produce a positive feedback for sustaining some droughts. Land surface effects have a much stronger and more systematic impact on temperatures than precipitation. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 43

Drought Predictability Because droughts occur across time scales, different kinds of indices or drought measures and forecast tools should be considered. Both precipitation and temperature forecasts are relevant. We need to consider the net water budget, as well as impacts (e. g. , evaporation, vegetation stress). Note that water demand also generally increases with increasing temperature. The degree to which we can predict drought is clearly determined by our skill at predicting physical modes and patterns at the longer scales. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 44

National Integrated Drought Information System “Creating a National Drought Early Warning System” WGA (2004), NIDIS Bill (2006), USGEO (2006) Preceded by: Western States Water Policy Commission (1998), NDMC, National Drought Bill efforts (2000) Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 45

NIDIS Vision and Goals “A dynamic and accessible drought information system that provides users with the ability to determine the potential impacts of drought and the associated risks they bring, and the decision support tools needed to better prepare for and mitigate the effects of drought. ” Implementation requires: • Coordinate a national drought monitoring and forecasting system • Creating a drought early warning system • Providing an interactive drought information delivery system for products and services—including an internet portal and standardized products (databases, forecasts, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), maps, etc) • Designing mechanisms for improved interaction with public (education materials, forums, etc) Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 46

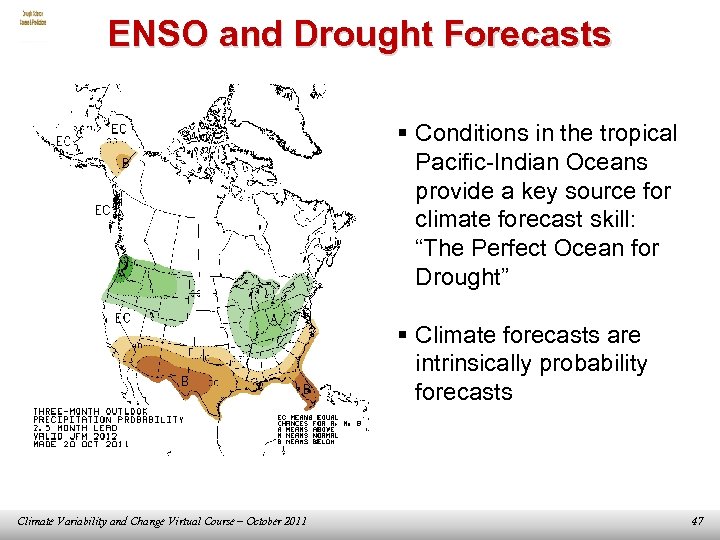

ENSO and Drought Forecasts § Conditions in the tropical Pacific-Indian Oceans provide a key source for climate forecast skill: “The Perfect Ocean for Drought” § Climate forecasts are intrinsically probability forecasts Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 47

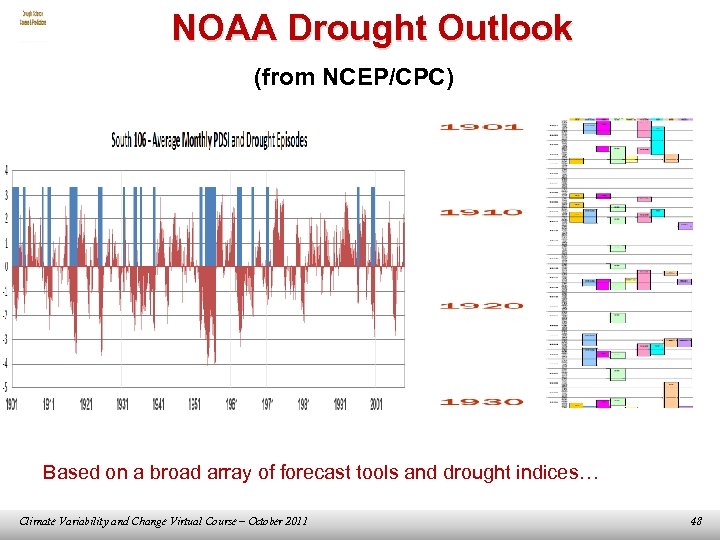

NOAA Drought Outlook (from NCEP/CPC) Based on a broad array of forecast tools and drought indices… Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 48

If we could forecast ocean anomalies, maybe there is some hope that we could make drought forecasts! Still we need to extract the signal of the ocean anomalies from all the climate noise. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 49

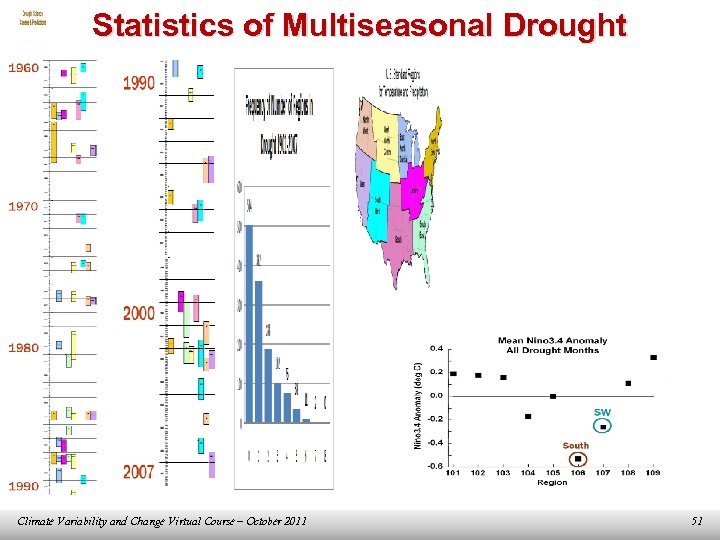

Statistics of Multiseasonal Drought Goal is to define a drought index in a manner similar to that used by seasonal forecasters at CPC, such that the relationship between drought forecasts and seasonal outlooks could be more seamless. Drought is defined as 6 consecutive 3 -month anomalies in the lowest tercile. We are also examining 12 -month anomalies. Statistics of drought episodes for 9 U. S. regions are being examined to study drought onset, demise, and the relationship to SST anomalies. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 50

Statistics of Multiseasonal Drought Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 51

Some Encouraging Results Composites comparing drought with Nino 3. 4 results agree with previous studies. However, while droughts in the south and southwest are related to SSTs, we cannot attribute all drought episodes to SST anomalies. Improved statistics of drought onset and demise may aid in the predictability of drought. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 52

Can we Improve Predictability? • Beyond a few weeks, the major source for current predictive skill is related to changes in the distribution of tropical heating, particularly over the Pacific and Indian Oceans. • We need to use both observational data and models to improve our both our understanding and our predictability of drought. • A “significant” percentage of drought likely can’t be forecast due to natural climate variability at temporal and spatial scales we can’t predict. • However, there is great public interest in drought prediction. We need to continue to work with our customers to develop predictive information to support them. WFOs and RFCs already do this on shorter time scales. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 53

Drought Summary • Drought is a recurrent part of the U. S. climate, and causes profound human and environmental impacts • Large-scale sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies, especially in the tropical Pacific and Indian Oceans, contribute significantly to seasonal and decadal drought variations • The El Nino-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) plays a significant, and potentially predictable, role in drought development and persistence, especially during the winter and spring • Land-surface and vegetation feedbacks can contribute to prolonging droughts and increasing drought severity • One of the goals of the CLIVAR drought monitoring program is an improvement in the predictive abilities of long term drought. • The development of seasonal maps showing locations of “hot spots” could be exploited to improve the skill of weather and climate prediction Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 54

Questions? More talking points and references are available on the following slides. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 55

Drought and Climate Summary What Causes Drought? • Direct causes are systematic shifts in storm tracks away from the affected region or persistent wind patterns that reduce moisture transports into the region. • A blocking weather pattern that features persistent, stationary high pressure over the affected area is often observed with droughts. • The conditions that produce droughts often also lead to increased sunshine and higher daytime temperatures and evaporation. Thus, summertime droughts are often associated with severe heat waves and increased wildfire risks, and place increased demands on energy as well as water resources. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 56

U. S Drought and Climate: Summary Factors influencing persistence of drought - 1 • Large-scale sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies, especially in the tropical Pacific and Indian Oceans, contribute significantly to seasonal and decadal drought variations. • Land-surface and vegetation feedbacks can contribute to prolonging droughts and increasing drought severity. • Atmospheric teleconnections such as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and the Pacific North American (PNA) pattern, and random changes circulation, may produce short, but intense, “flash droughts”, adversely affecting agriculture at critical times in the growing season. • The El Nino-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) plays a significant, and potentially predictable, role in drought development and persistence, especially during the winter and spring • Recent NOAA research has shown the importance of the warming trend in the Indo-Pacific region in the severe, sustained Western drought of 1999 -2004. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 57

U. S Drought and Climate: Summary Factors influencing persistence of drought - 2 • The roles of multi-decadal oscillations of SST patterns in the Pacific and the Atlantic in droughts are less certain but are being actively investigated. • Long-term warming trends have led to changes in the timing of snow melt and stream flows, especially in the West. This is resulting in earlier peak stream flows and diminished summer-time flows. • Observed increases in temperature appear to have slightly increased the intensity of recent droughts. This trend is projected to continue, and may lead to more intense droughts during periods of dry weather due to increases in evaporation. • In general, models suggest that as the planet warms, storminess and the jet stream tracks will shift northward. Such a shift would increase the likelihood of dry conditions in some southwestern and southern parts of the U. S. , although confidence in regional projections of precipitation changes is low. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 58

SST and Soil Moisture Feedback and the Time Scale of Drought • The soil moisture-drought relationship has a strong dependence on the time scale of drought • Short-term droughts are mostly influenced by simultaneous remote SST forcing • Medium- and long-term droughts are influenced by both preceding and simultaneous remote SST forcing • The tropical Pacific provides the dominant forcing, but the tropical Indian Ocean has an impact on medium- and long term droughts • Soil moisture feedback likely contributes more to the persistence of drought from winter to summer Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 59

Drought Forecasts – Take Home Points • Climate forecasts are intrinsically probability forecasts. • Beyond a few weeks, the major source for current predictive skill is related to changes in the distribution of tropical heating, particularly over the Pacific and Indian Oceans. • Users are interested in current information and predictions across a broad range of time scales. Short-term: use ensemble model forecasts plus CPC’s hazard assessment product. Crop moisture can change significantly on these time scales. • For longer-term outlooks that relate to hydrologic conditions, use the current Drought Outlook and monthly and seasonal forecasts. • CPC issues a drought outlook product on a monthly basis. This is currently constructed subjectively from a blend of current conditions, knowledge of seasonal cycle, and various forecast products. • One of the goals of the CLIVAR drought monitoring program is an improvement in the predictive abilities of long term drought. • The development of seasonal maps showing locations of “hot spots” could be exploited to improve the skill of weather and climate prediction. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 60

Current Areas of NOAA Research • Understanding relationships between seasonal to decadal ocean variability and droughts. • Improving understanding of the role of land surface and vegetation feedbacks in prolonging and increasing the severity of droughts. • Understanding the causes of long-lived droughts, such as in the 1930 s Dust Bowl period, and developing associated predictive capabilities. • Improving objective drought monitoring and prediction capability, including estimates of soil moisture and snow water storage. • Developing a drought early warning capability through the National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS). • Incorporating the broader range of drought variability contained in paleohydrologic records into resource management and drought planning. • Determining potential relationships between droughts and changes in greenhouse gases, aerosols, and land use. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 61

Drought Resources • • NESDIS/NCDC – official archive for drought data sets; analyses of climate trends, monitoring and historical perspective on current seasons, and paleoclimate reconstructions of drought. NOAA Climate Program Office – intramural and extramural support for development of a predictive understanding of the climate system, the required observational capabilities, delivery of climate services NWS/NCEP/CPC – intraseasonal to multi-season climate variability forecasts; diagnostic studies of major climate anomalies; real time monitoring of climate; seasonal drought outlooks. OAR/GFDL – studies of climate variability and change; development of comprehensive climate models for use in both seasonal forecasting and multi-decadal climate change projections; projections of future climate change. OAR/ESRL – diagnostic studies of climate variability and changes; impacts of climate on extreme events, experimental forecast products week two to multi-season, modelintercomparisons, ENSO-extreme event risks, etc. International Research Institute for Climate Prediction (IRI) - enhances society's capability to understand, anticipate and manage the impacts of seasonal climate fluctuations, in order to improve human welfare and the environment, especially in developing countries. National Drought Mitigation Center (NDMC) helps people and institutions develop and implement measures to reduce societal vulnerability to drought, stressing preparedness and risk management rather than crisis management Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 62

Drought Research References CLIVAR Drought Research Resources Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 63

Recent Drought Research References Capotondi, A. , and M. A. Alexander, 2010: Relationship between precipitation in the Great Plains of the United States and Global SSTs: Insights from the IPCC AR 4 models. J. Climate, 23, 2941 -2959. Cook, B. I. , E. R. Cook, K. J. Anchukaitis, R. Seager, and R. L. Miller, 2011: Forced and unforced variability of twentieth century North American droughts and pluvials. Clim. Dyn. , 37, 1097 -1110. Enfield, D. B. , A. M. Mestas-Nuñez, and P. J. Trimble, 2001: The Atlantic multidecadal oscillation and its relation to rainfall and river flows in the continental U. S. Geophys. Res. Let. , 28, 2077 -2080. Feng, S. , Q. Hu, and R. J. Oglesby, 2011: Influence of Atlantic sea surface temperatures on persistent drought in North America. Clim. Dyn. , 37, 569 -586. Guan, B. , and S. Nigam, 2009: Analysis of Atlantic SST variability factoring interbasin links and the secular trend: Clarified structure of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. J. Climate, 22, 4228 -4240. Hoerling, M. , X. -W. Quan, and J. Eischeid, 2009: Distinct causes for two principal U. S. droughts of the 20 th century. Geophys. Res. Lett. , 36, L 19708. Kushnir, Y. , R. Seager, M. Ting, N. Naik, and J. Nakamura, 2010: Mechanisms of tropical Atlantic SST influence on North American precipitation variability. J. Climate, 23, 5610 -5629. Mo, K. C. , J. -K. E. Schemm, and S. -H. Yoo, 2009: Influence of ENSO and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation on drought over the United States. J. Climate, 22, 5962 -5983. Nigam, S. , B. Guan, and A. Ruiz-Barradas, 2011: Key role of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation in 20 th century drought and wet periods over the Great Plains. Geophys. Res. Lett. , 38, L 16713. Pegion, P. J. , and A. Kumar, 2010: Multimodel estimates of atmospheric response to modes of SST variability and implications for droughts. J. Climate, 23, 4327 -4342. Shin, S. -I. , P. D. Sardeshmukh, and R. S. Webb, 2010: Optimal tropical sea surface temperature forcing of North American drought. J. Climate, 23, 3907 -3818. Climate Variability and Change Virtual Course – October 2011 64

c72518e7ffdf9c041b3e9d746a7acc97.ppt