0e0beb423069e3f605c084aa8c3ba29c.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 60

Debt and Debt Crises Ugo Panizza UNCTAD There are my own views

The standard view • Facts – Countries get into debt problems because of lax fiscal policies – Countries have an incentive to default on their external debt obligations • Policies – Debt crises should always be followed by a fiscal retrenchment – We need to implement policies that reduce a country's incentive to default

Background • U. Panizza, F. Sturzenegger, and J. Zettelmeyer (2009) "The Economics and Law of Sovereign Debt and Sovereign Default" Journal of Economic Literature • B. Eichengreen, R. Hausmann, and U. Panizza (2003) “The Pain of Original Sin” University of Chicago Press • E. Borensztein, and U. Panizza (2009)"The Costs of Sovereign Default" IMF Staff Papers • E. Levy Yeyati and U. Panizza (2010) "The Elusive Cost of Sovereign Default, " Journal of Development Economics • E. Borensztein, E. Levy Yeyati, and U. Panizza (2006) Living with Debt, Harvard University Press and IDB • C. Campos, D. Jaimovich, and U. Panizza (2006) “The Unexplained Part of Public Debt, ” Emerging Markets Review

Outline • Facts – How debt grows – When do countries borrow and default • Policies – Avoiding debt explosions – What to do during debt crises – How to deal with defaults

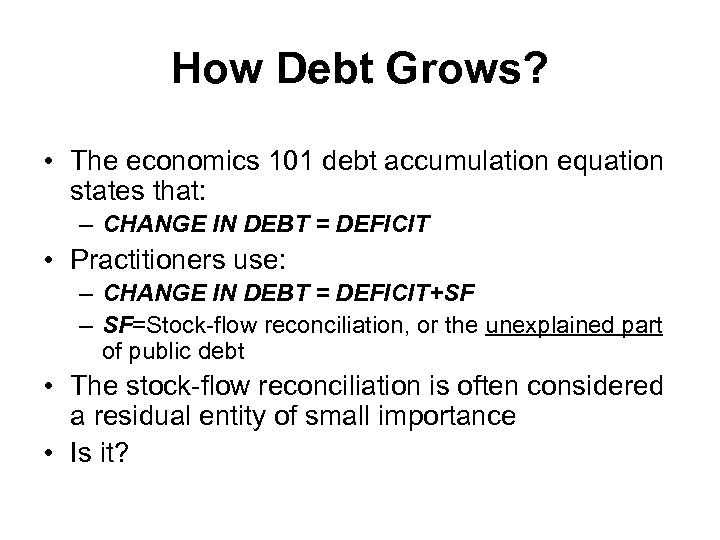

How Debt Grows? • The economics 101 debt accumulation equation states that: – CHANGE IN DEBT = DEFICIT • Practitioners use: – CHANGE IN DEBT = DEFICIT+SF – SF=Stock-flow reconciliation, or the unexplained part of public debt • The stock-flow reconciliation is often considered a residual entity of small importance • Is it?

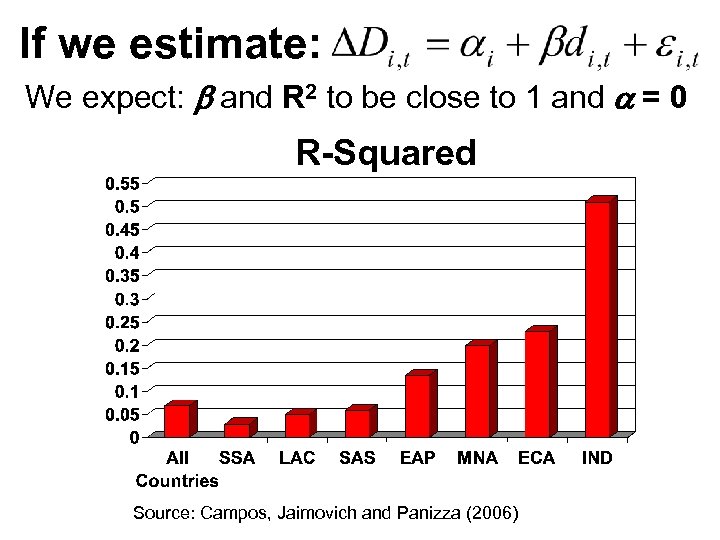

If we estimate: We expect: b and R 2 to be close to 1 and a = 0 R-Squared Source: Campos, Jaimovich and Panizza (2006)

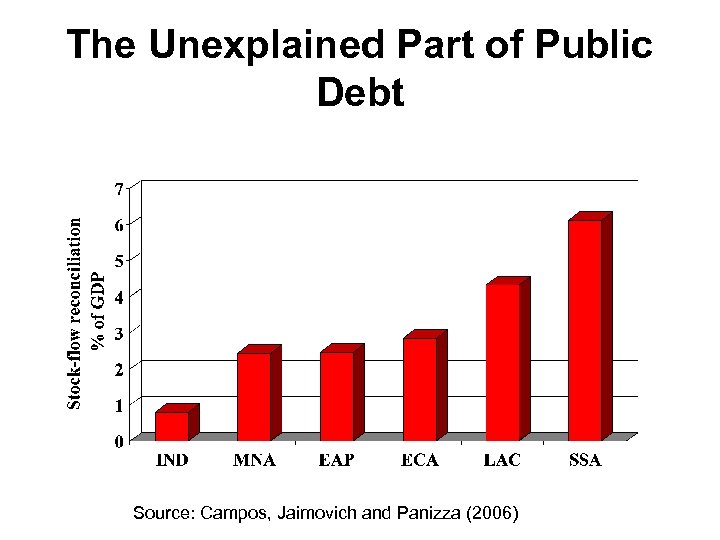

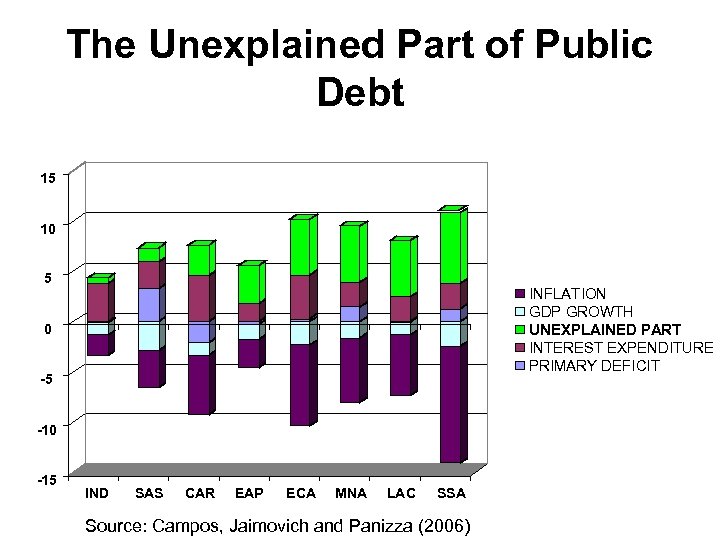

The Unexplained Part of Public Debt Source: Campos, Jaimovich and Panizza (2006)

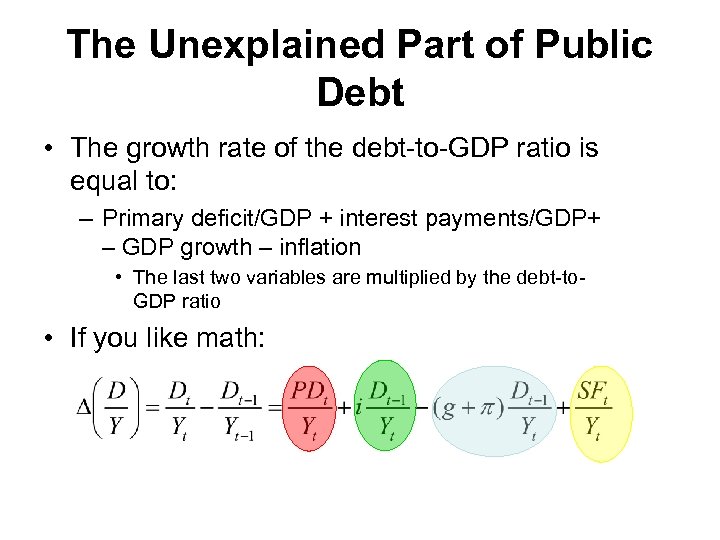

The Unexplained Part of Public Debt • The growth rate of the debt-to-GDP ratio is equal to: – Primary deficit/GDP + interest payments/GDP+ – GDP growth – inflation • The last two variables are multiplied by the debt-to. GDP ratio • If you like math:

The Unexplained Part of Public Debt 15 10 5 INFLATION GDP GROWTH UNEXPLAINED PART INTEREST EXPENDITURE PRIMARY DEFICIT 0 -5 -10 -15 IND SAS CAR EAP ECA MNA LAC SSA Source: Campos, Jaimovich and Panizza (2006)

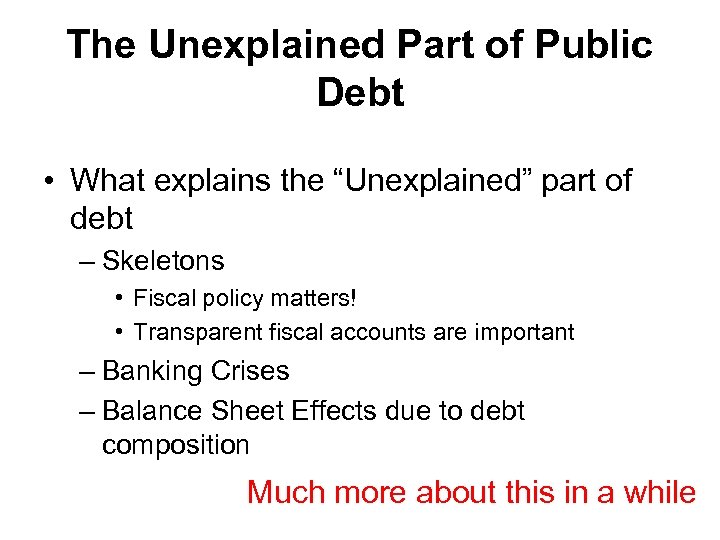

The Unexplained Part of Public Debt • What explains the “Unexplained” part of debt – Skeletons • Fiscal policy matters! • Transparent fiscal accounts are important – Banking Crises – Balance Sheet Effects due to debt composition Much more about this in a while

The Unexplained Part of Public Debt • There also things that we can explain but may not have anything to do with fiscal policy – Output collapses – Sudden jumps in borrowing costs – Natural disasters

Outline • Facts – How debt grows – When do countries borrow and default • Policies – Avoiding debt explosions – What to do during debt crises – How to deal with defaults

Why is sovereign debt special? • Creditor rights are not as well defined for sovereign debt as is the case for private debts. • If a private firm becomes insolvent, creditors have a claim on the company’s assets. • In the case of a sovereign debt, in contrast, the legal recourse available to creditors has limited applicability and uncertain effectiveness. – Sovereign immunity – Little to attach • So, why do countries repay and why do lenders lend?

Theory

The Economic Theory of Sovereign Debt • The literature started with (and it's still tied to) an influential theoretical paper by Eaton and Gersovitz (Review of Economic Studies, 1981) • The story of the paper was: – Countries borrow in bad times (low economic growth) and repay in good times (high economic growth) – Since there are no repayments in bad times, there cannot be defaults either – As a consequence, defaults can only happen in good times – Defaults are thus strategic (countries can pay but they decide not to pay) – The only reason that prevents countries from defaulting is that defaults are costly

The Economic Theory of Sovereign Debt • So, what are the costs of default? – The traditional economic literature has emphasized – Reputational costs • Countries that default will no longer be able to access the international capital market – Trade costs • Default will lead to sanctions which, in turn, will have a negative effect on trade

From theory to the data

Do countries borrow in bad times?

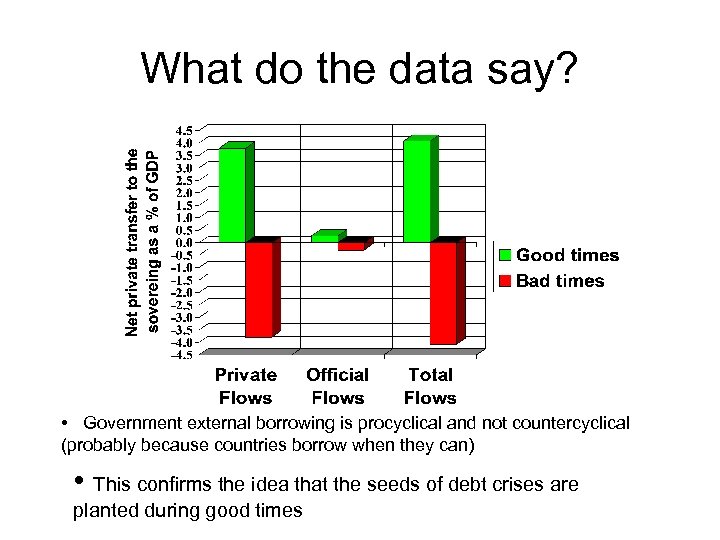

What do the data say? • Government external borrowing is procyclical and not countercyclical (probably because countries borrow when they can) • This confirms the idea that the seeds of debt crises are planted during good times

Do countries default in good times?

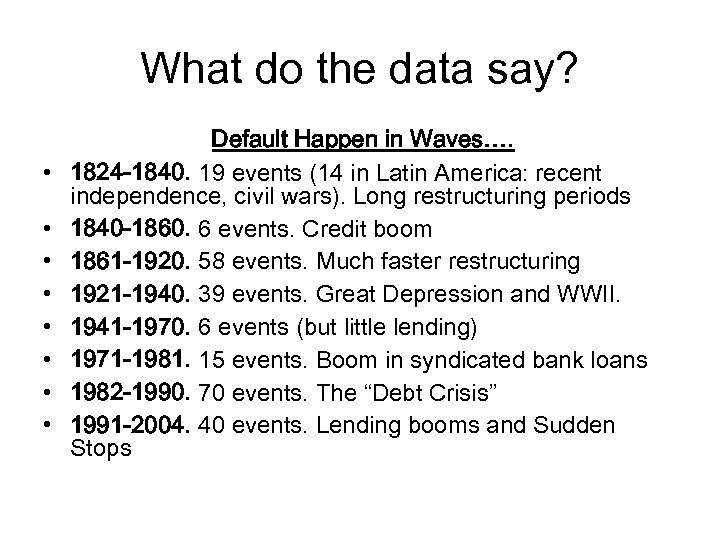

What do the data say? • • Default Happen in Waves…. 1824 -1840. 19 events (14 in Latin America: recent independence, civil wars). Long restructuring periods 1840 -1860. 6 events. Credit boom 1861 -1920. 58 events. Much faster restructuring 1921 -1940. 39 events. Great Depression and WWII. 1941 -1970. 6 events (but little lending) 1971 -1981. 15 events. Boom in syndicated bank loans 1982 -1990. 70 events. The “Debt Crisis” 1991 -2004. 40 events. Lending booms and Sudden Stops

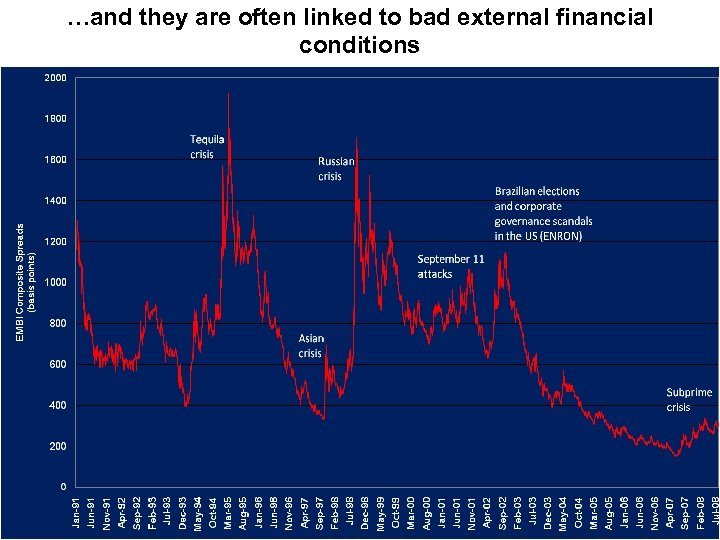

…and they are often linked to bad external financial conditions

Do defaulter pay a high cost?

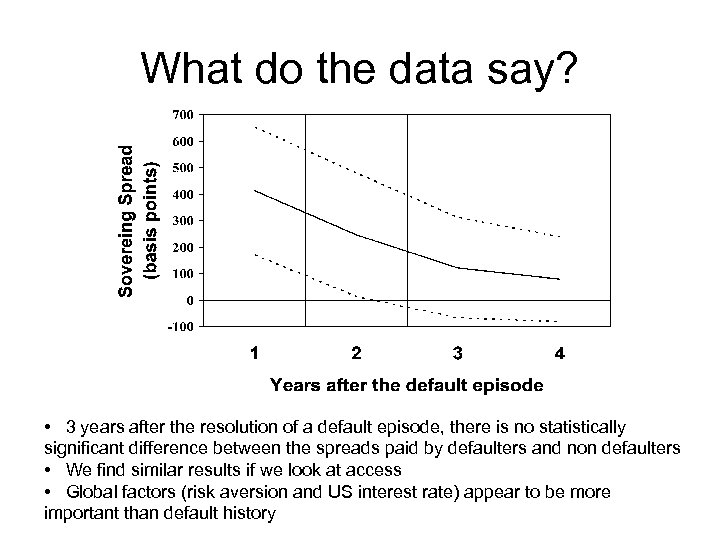

What do the data say? • 3 years after the resolution of a default episode, there is no statistically significant difference between the spreads paid by defaulters and non defaulters • We find similar results if we look at access • Global factors (risk aversion and US interest rate) appear to be more important than default history

What do the data say? • There is some evidence that defaults have a negative effect on trade • But this is still controversial and the channel is not clear – No evidence that defaults have a direct impact on trade credit – No evidence (at least in recent years) of explicit sanctions

What do the data say? • Anyway, who cares? – We do know that defaults are bad because they lead to deep recessions • Econometric estimates found that, on average, default episodes are associated with a 2 percentage points drop in GDP growth • But do we really know what we think we know? – Are default episodes bad for growth or is it low growth that causes default? – That is, do defaults happen in bad times?

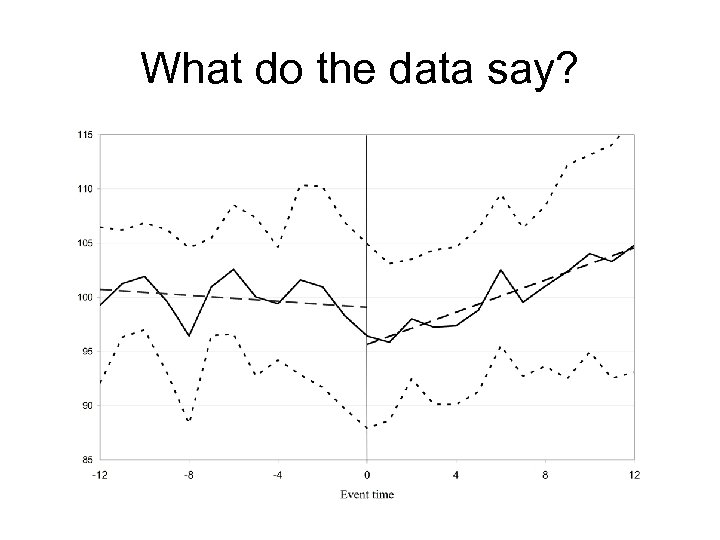

What do the data say? • Causality is always very hard to assess • But, if we look at high frequency data, we find that: – Growth collapses anticipate defaults – Default episodes are often followed by a rapid rebound of the economy

What do the data say?

Do countries default too early or too late? • Hell, the last thing I should be doing is tell a country we should give up our claims. But there comes a time when you have to face reality. – Unnamed financial industry official. Both are taken (Source: Bluestein, 2005, p 163) • The problem historically has not been that countries have been too eager to renege on their financial obligations, but often too reluctant. – Memo prepared by the Central Banks of England Canada (Source: Bluestein, 2005, p 102)

Political costs of default • There is a (small) literature of political costs of currency devaluations (Cooper 1971). • Frankel (2005) finds that a devaluation increases turnover of finance ministers from 36 to 58 percent. – Applying Frankel’s approach, bond defaults increase minister turnover from 19 to 40 percent. But bank defaults increase it only to 24 percent. – Governments lose votes after defaults • The high political cost of default may affect the timing of the decision by the government. It could cause “gambles for redemption” – Mickey Mouse model (Borensztein and Panizza, 2009)

Summing up: Theory versus Reality • Theory – Countries get into trouble because of lax fiscal policy – Countries borrow in bad times – If ever, countries default in good times (strategic defaults) • So, if anything, they default too much – Defaults are very bad for the economy, with long lasting negative consequences • Reality – Many debt explosions have nothing to do with fiscal policy – Countries borrow in good times – Countries default in bad times (justified defaults) • And sometimes too late – Defaults do not seem to have long lasting negative consequences

Outline • Facts – How debt grows – When do countries borrow and default • Policies – Avoiding debt explosions – What to do during debt crises – How to deal with defaults

Prudent Fiscal Policy • Control the flow of debt – Only borrow when the social return is higher than the opportunity cost of funds – This requires strengthening fiscal policies and institutions • Fiscal rules • Budget institutions – Hierarchical rules – Transparency Rules – Like motherhood and apple pie, this is always good, but it may not be enough

Avoid disasters in the banking sector • It is mostly about preventing lending booms (Borio, Reinhart, Rogoff)

But low debt can’t buy you love

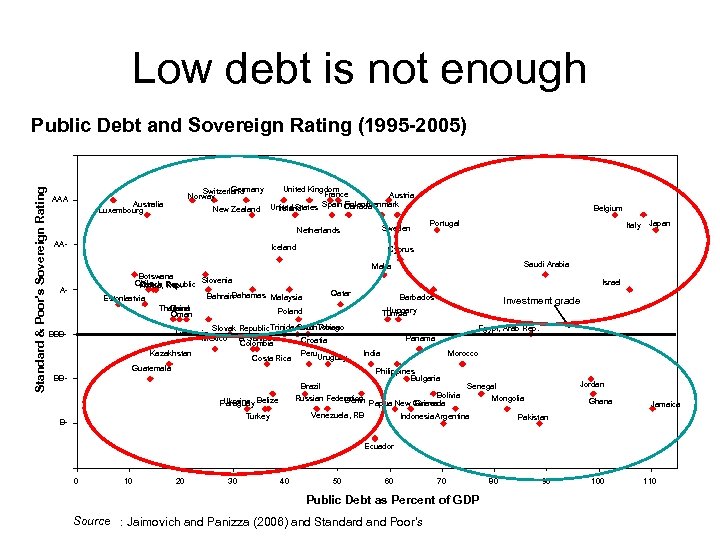

Low debt is not enough Standard & Poor's Sovereign Rating Public Debt and Sovereign Rating (1995 -2005) AAA Germany Switzerland Norway Australia Luxembourg New Zealand United Kingdom France Austria Denmark Canada United States Spain Finland Ireland Sweden Netherlands AA- Iceland Belgium Portugal Italy Cyprus Saudi Arabia Malta Botswana Slovenia Chile Czech Rep. Korea, Republic Bahamas Malaysia Bahrain Estonia Latvia Thailand China Poland Oman A- Israel Qatar BB- Egypt, Arab Rep. India Morocco Philippines Bulgaria Bolivia Papua New Guinea Grenada Venezuela, RB Turkey Investment grade Panama Brazil Russian Federation Benin Ukraine Paraguay Belize B- Barbados Hungary Tunisia South Africa Slovak Republic Trinidad and Tobago Lithuania Mexico El Salvador Croatia Colombia Kazakhstan Peru. Uruguay Costa Rica Guatemala BBB- Japan Jordan Senegal Mongolia Indonesia Argentina Ghana Jamaica Pakistan Ecuador 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 Public Debt as Percent of GDP Source : Jaimovich and Panizza (2006) and Standard and Poor's 80 90 100 110

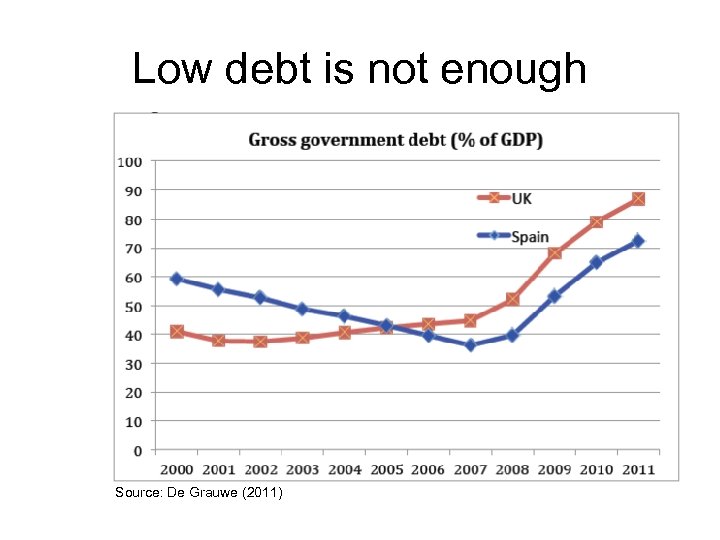

Low debt is not enough Source: De Grauwe (2011)

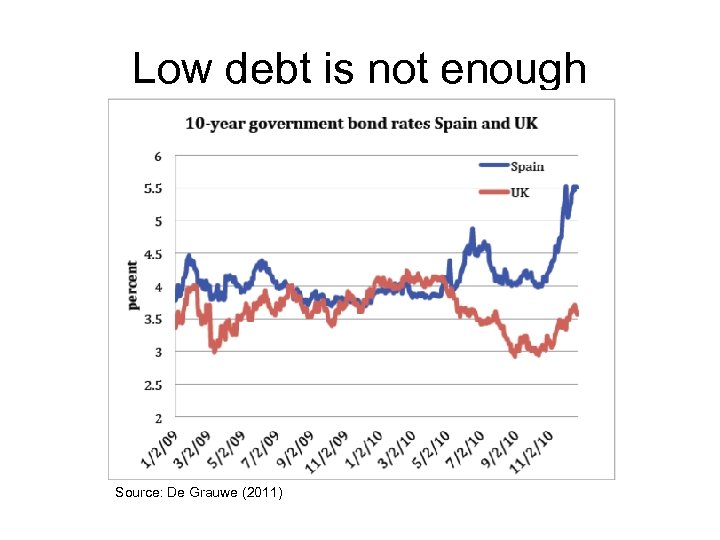

Low debt is not enough Source: De Grauwe (2011)

A tale of two countries

The importance of debt structure • Debt denominated in foreign currency or short-maturity debt is associated with: – Lower Credit Ratings – Sudden Stops – Higher volatility – Limited ability of conducting monetary policy – Contractionary devaluations • An appropriate debt structure can reduce risk

How to make debt safer • New and safer instruments – Local currency – Contingent debt instruments • GDP index bonds • Commodity linked bonds • Catastrophe bonds • Dedollarize official lending

Why do we need official intervention? • Market failures – Critical mass – Standards – Instruments cannot be patented • Political economy – Shortsighted politicians may underinsure

Outline • Facts – How debt grows – When do countries borrow and default • Policies – Avoiding debt explosions – What to do during debt crises – How to deal with defaults

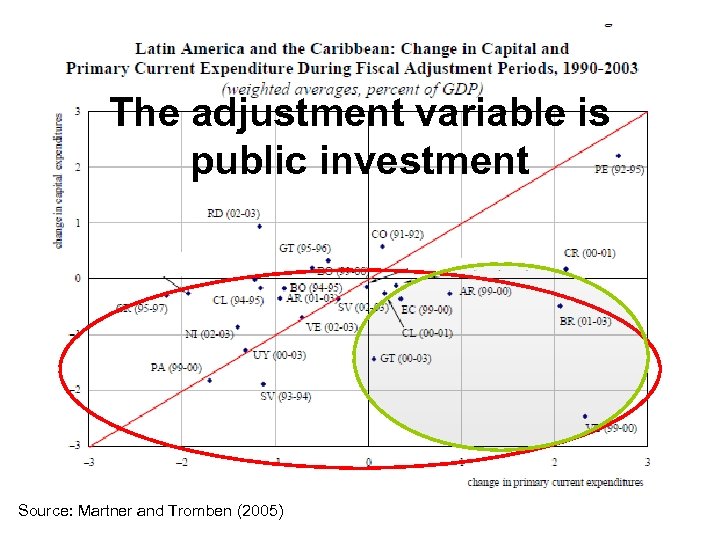

Fiscal consolidation? • The instinctive response to a debt crisis is (almost) always: we need a fiscal adjustment • This does not make much sense if the debt crisis is not rooted in fiscal problems • In fact, it may hurt. • Not only in the short-run, but also in the long-run: – Recessions lead to a permanent output loss (Cerra and Saxena, 2008) – The adjustment variable is public investment (Easterly, Irwin, Serven, 2008; Martner and Tromben, 2005)

The adjustment variable is public investment Source: Martner and Tromben (2005)

…and this is very bad for growth, and for the fiscal adjustment When growth-promoting spending is cut so much that the present value of future government revenues falls by more than the immediate improvement in the cash deficit, fiscal adjustment becomes like walking up the down escalator. (Easterly, Irwin, Serven, 2008)

What can the international community do? • Don’t ask for fiscal contractions if fiscal profligacy was not the problem • If a fiscal contractions is needed, don’t frontload it (Blanchard and Cottarelli, 2010) • Think about fiscal targets that protect investment (Blanchard and Giavazzi, 2004, Buiter, 198? ) • Also think about the quality of public investment (Pritchett, 2000, Dabla-Norris et al. , 2011, )

When is a fiscal contraction needed? • Think hard about the math Dd=-ps+(i-g)d – Multiple equilibria (high i and low i) – The international community can help (especially when the global i is very low) – Don’t lend at punitive interest rates • Bagehot was right for banking crises, but he might be wrong for sovereign debt crises – Moral hazard is often overstated (Meltzer versus Krugman)

Outline • Facts – How debt grows – When do countries borrow and default • Policies – Avoiding debt explosions – What to do during debt crises – How to deal with defaults

From earlier this morning • Theory – Countries borrow in bad times – If ever, countries default in good times (strategic defaults) • So, if anything, they default too much – Defaults are very bad for the economy, with long lasting negative consequences • Reality – Countries borrow in good times – Countries default in bad times (justified defaults) • And sometimes too late – Defaults do not seem to have long lasting negative consequences

To default or not to default? • Let me start by saying that I am not (I repeat NOT) suggesting that countries should default more often • But I want to ask, why is there this disconnect between theory and reality? • The theory might be wrong • Or, they may be a problem with the world • My hunch is that this is due to a mix of political failure and a lousy international financial architecture

Is the world wrong? • In a well working system, countries should be able to borrow when they need funds (i. e. , in bad times) – But during bad times, the international capital markets are not willing to provide credit at a reasonable interest rate – Therefore, countries borrow in good times because this is when they have access to credit • Same reason why Willie Sutton robbed banks – Unfortunately, sometimes they borrow too much in good times and this behavior sows the seeds of future crises • We need to fix the political economy of debt – The real reason why Willie Sutton robbed banks

Strategic or justified? • Most of the defaults we observe are justified (or unavoidable, at least ex-post) episodes • Strategic defaults are very rare – So, we cannot use econometric methods to assess the cost of these very rare events – What we are actually assessing is the cost of non-strategic defaults • But why are they rare? • Probably because they are costly • But what is the cost?

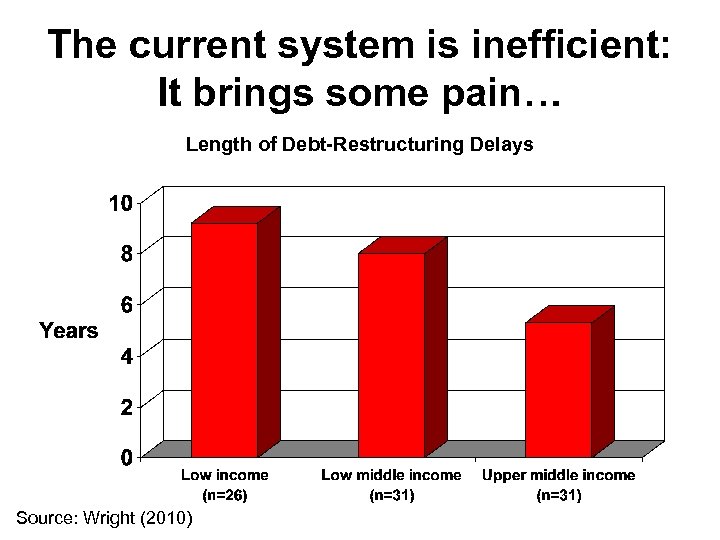

The current system is inefficient: It brings some pain… Length of Debt-Restructuring Delays Source: Wright (2010)

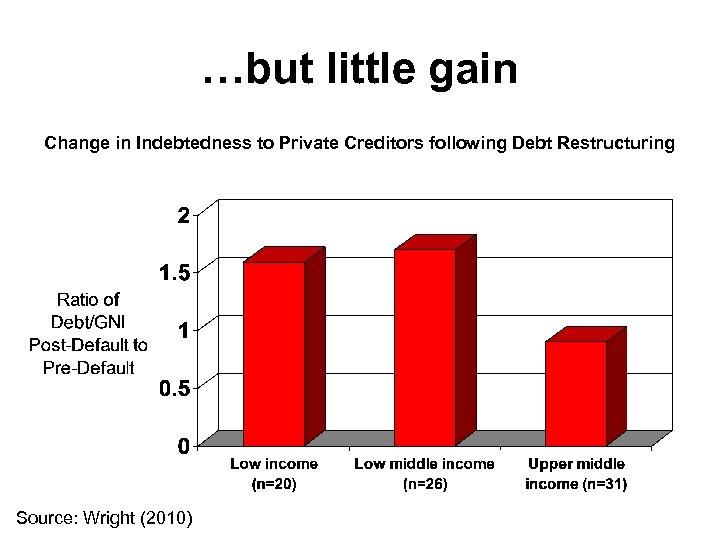

…but little gain Change in Indebtedness to Private Creditors following Debt Restructuring Source: Wright (2010)

Is this inefficient system efficient? • Some pain and no gain might be inefficient expost, but could be efficient ex-ante • High costs of defaults are necessary to create willingness to pay, establish credibility, and lower borrowing cost – Dooley (2000), Shleifer (2003) • This is why countries suboptimally delay default • This is why some borrowing countries are opposed to the creation of a mechanism that may eliminate these inefficiencies

From second best to first best • This is clearly a second best solution – Countries suffer – They destroy value and decrease recovery rates

From second best to first best • An alternative story – The international community and financial markets implicitly forgive countries that default out of necessity but would impose a harsh punishment on countries that default strategically (Grossman and van Huyk, AER 1988) – If this is the case, policymakers need to signal that the default is indeed unavoidable and not strategic – A way of doing this is to go through considerable pain in order to delay the default as long as possible • Also second best, but in this case there is a solution

From second best to first best • Solution: – The first best could be achieved with the creation of a body with the ability to assess whether a default was indeed unavoidable • A bankruptcy court for sovereigns • By increasing potential recovery rates, it could be efficient both ex-ante and ex-post • Everybody (lenders and borrowers) is better off

Debt and Debt Crises Ugo Panizza UNCTAD There are my own views

0e0beb423069e3f605c084aa8c3ba29c.ppt