043f31197828e084cae58ad29f5de995.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 96

Data Modeling and Database Design Chapter 6: The Relational Data Model

The Motivation for Logical Data Modeling • Completion of conceptual modeling phase results in reasonably clear picture of data requirements for application system at high level of abstraction • Note: conceptual data model is technology-independent • During conceptual modeling, analysis and design activity is not constrained by boundaries of anticipated technology that will be used for implementation lest the richness of design will be compromised • Conceptual schema may contain constructs not directly compatible with technology intended for implementation Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 2

The Motivation for Logical Data Modeling (continued) • Sometimes further refinement may be required to eliminate data redundancy in design • Transforming conceptual schema to state better compatible with implementation technology of choice is achieved via logical data modeling • Logical data modeling phase serves as transition from technology-independent conceptual schema to technologydependent design Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 3

The Relational Data Model • E. F. Codd in 1970 used the concept of mathematical relations to define the relational data model • Database = collection of relations • Relation = two-dimensional table • Row in the table = related data values = tuple • Column in the table = attribute • Set of all tuples in the table = relation • Relation consists of a heading and a body • Heading = relation schema, intension, relvar • Body = extension • Domain = set of possible atomic values of an attribute Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 4

A Technical Definition of a Relational Data Model • If r is relation whose structure is defined by set of attributes A 1, A 2, …, An, then R(A 1, A 2, …, An) is called relation schema of relation r • An attribute, A, is ordered pair (N, D) where N is the name of attribute and D is the domain that named attribute represents – Alternatively, an attribute represents a ‘named role’ of a domain • Domain of Ai (i = 1, 2, …, n) is often denoted as Dom (Ai) • Relation schema, R, is named collection of attributes (R, {C}) where R is name of relation schema and {C} is set { (N 1, D 1), (N 2, D 2), . . . (Nn, Dn) } where N 1, N 2. …, Nn are distinct names • r is relation (or relation state) over schema R Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 5

A Technical Definition of a Relational Data Model (continued) • Relation state r of relation schema R(A 1, A 2. …, An), also denoted as r(R), is set of n-tuples {t 1, t 2. …, tm} • Each n-tuple tj (j = 1, 2, …, m) in r(R) is ordered list of n values <v 1 j, v 2 j, …, vnj> where each vij (i = 1, 2, …, m) is element of Dom (Ai) (i = 1, 2, …, n) or when allowed, a missing value represented by special value called null • Number of attributes (n) in R is called degree (or arity) of R • Number of tuples, m, in relation state is called cardinality of relation Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 6

A Technical Definition of a Relational Data Model (continued) • Relation schema is sometimes loosely (and incorrectly) referred to as a relation – C. J. Date (2004) has coined the term relvar (abbreviation for relation variable) to distinguish relation schema from relation • Relational schema defines set of relation schemas in relational data model • Important to note difference between relation and relation schema as well as relation schema and relational schema (also known as database schema) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 7

Characteristics of a Relation • A relation: – Is equivalent to a two-dimensional table – Has a heading and a body • Attributes of relation schema have unique names • Values of attribute in relation come from same domain that has no null values • Attributes of relation cannot have null values • Order of arrangement of tuples is immaterial Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 8

Characteristics of a Relation (continued) • Each attribute value in tuple is atomic; hence, composite and multivalued attributes are not allowed in relation • Order of arrangement of attributes in relation schema is immaterial as long as correspondence between attributes and their values in relation is maintained • Derived attributes are not captured in relation schema • All tuples in relation must be distinct (i. e. , relation schema must have unique identifier) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 9

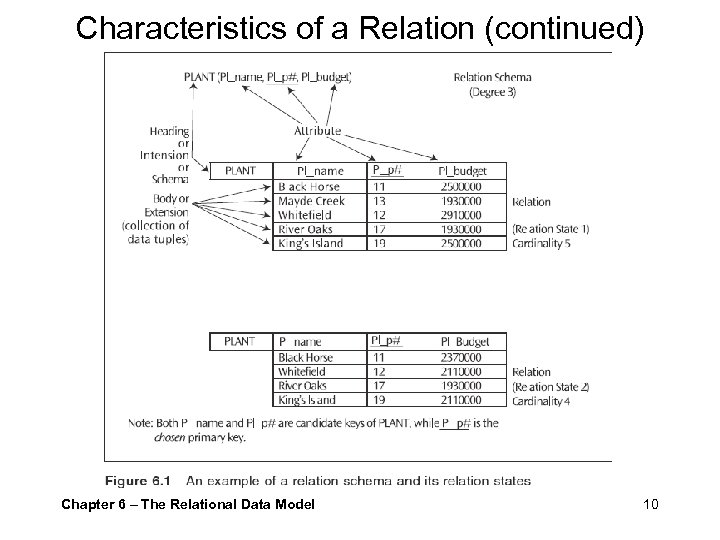

Characteristics of a Relation (continued) Example Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 10

Universal Relation Schema Defined • Universal Relation Schema (URS) assumption dictates that every attribute name must be unique because attributes have global meaning in database schema – Therefore, if attribute name appears in several relation schemas, all of these denote same meaning • In ER model, however, same attribute name is allowed to appear in different entity types since they imply different roles for the attribute name • Thus, mapping of attributes from ER model to logical schema requires careful attention in order to ensure unique attribute names in logical schema • Note: referencing foreign key and corresponding referenced primary (or alternate) key having the same attribute name in a logical schema does not violate the URS assumption Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 11

Naming Conventions • Since relational database theory stipulates that attribute names must be unique over entire relational schema, the following guidelines represent the approach used in this chapter for developing attribute names: – Each attribute name begins with up to a three-letter prefix that represents a meaningful abbreviation of the name of relation schema to which attribute belongs • This prefix is followed by an underscore character • Only first letter of prefix is capitalized – Following the underscore character is suffix that corresponds to attribute name itself • This suffix may contain only lowercase letters, a pound sign (#), and underscore characters, and corresponds to name of the attribute in conceptual data model – Examples: Pl_name, Pl_p#, Pl_budget Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 12

Data Integrity Constraints • Data integrity constraints: – Are rules that govern the behavior of data at all times in a database – Generally referred to as just integrity constraints – Are technical expressions of business rules that emerge from user requirement specifications for database application • The source of integrity constraints is the business rules – Prevail across all tiers of data modeling – conceptual, logical, and physical – Are considered to be part of the schema in that they are declared along with structural design of data model (conceptual, logical, and physical) and hold for all valid states of a database that correctly model an application (Ullman and Widom, 1997) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 13

Classification of Data Integrity Constraints • Inherent Model-based Constraints: – Constraints driven by modeling grammar • Schema-based or Declarative Constraints: – – – Domain constraints Key constraints Relationship structural constraints Entity integrity constraints Referential integrity constraints Functional dependency constraints • Semantic Integrity Constraints: – Application-based procedural constraints – DBMS-based procedural constraints (e. g. , assertions, triggers, etc. ) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 14

Types of Data Integrity Constraints • State Constraints: – All declarative and procedural constraints that every valid state of a database must satisfy • Transition Constraints: – Procedural constraints that define legal transitions of state Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 15

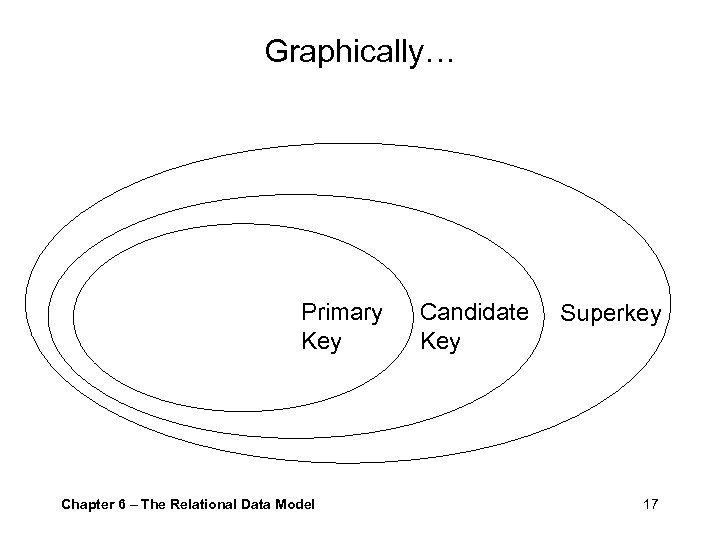

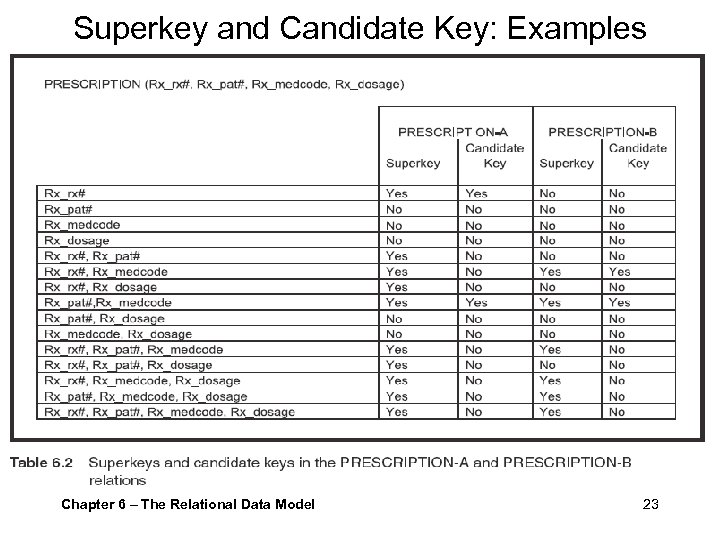

The Concept of Unique Identifiers • Superkey: – A set of one or more attributes, which taken collectively, uniquely identifies a tuple of a relation {uniqueness property} • Candidate Key: – A superkey with no proper subset that uniquely identifies a tuple of a relation {uniqueness property + irreducibility} • Primary Key: – A candidate key with no missing values for the constituent attributes {uniqueness property + irreducibility + entity integrity constraint} • Alternate Key: – Any candidate key that is not serving the role of the primary key Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 16

Graphically… Primary Key Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model Candidate Key Superkey 17

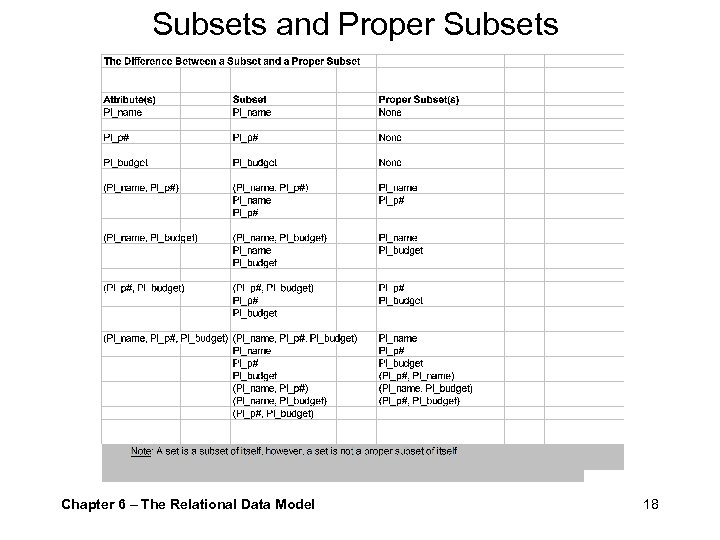

Subsets and Proper Subsets Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 18

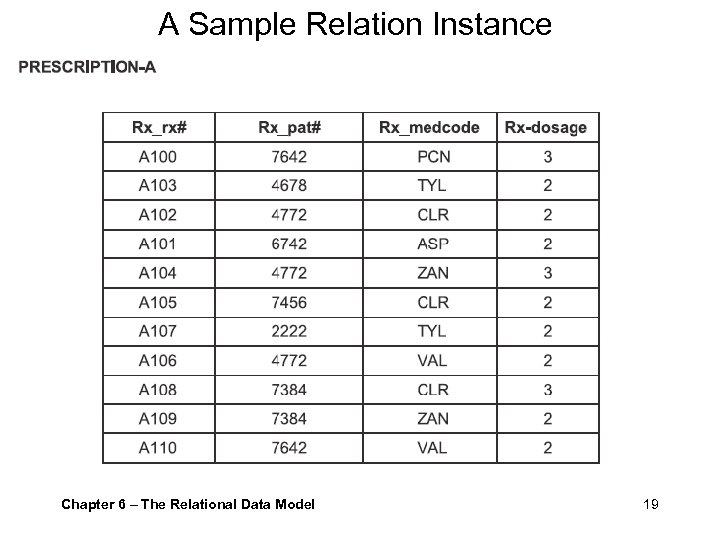

A Sample Relation Instance Example Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 19

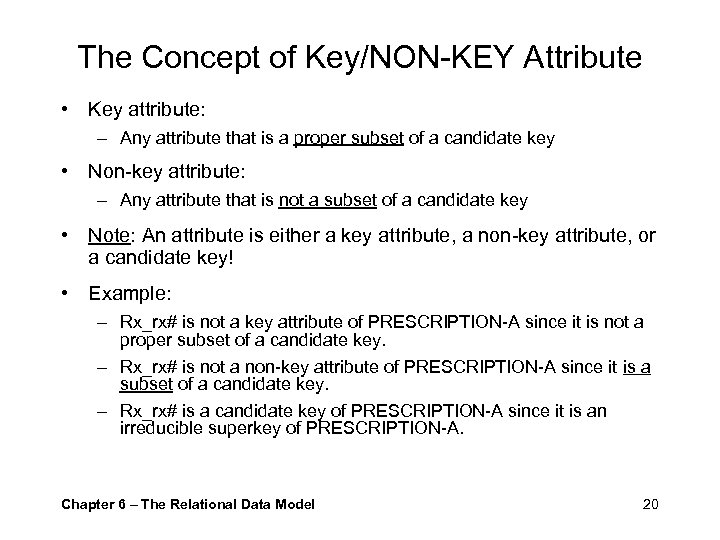

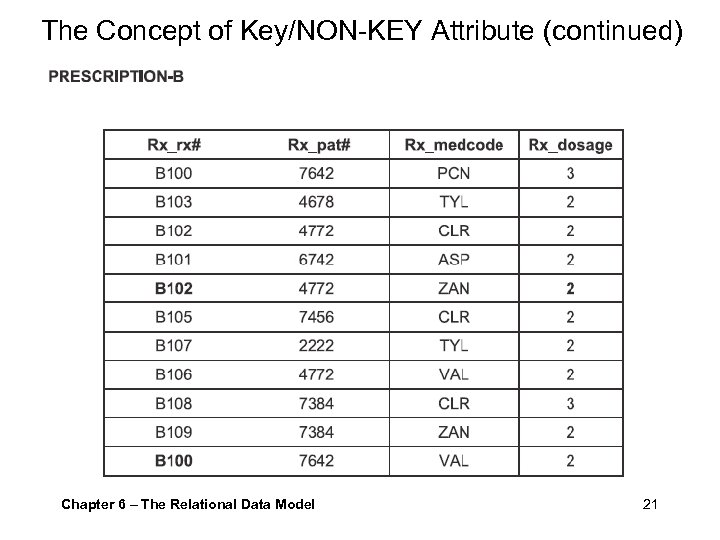

The Concept of Key/NON-KEY Attribute • Key attribute: – Any attribute that is a proper subset of a candidate key • Non-key attribute: – Any attribute that is not a subset of a candidate key • Note: An attribute is either a key attribute, a non-key attribute, or a candidate key! • Example: – Rx_rx# is not a key attribute of PRESCRIPTION-A since it is not a proper subset of a candidate key. – Rx_rx# is not a non-key attribute of PRESCRIPTION-A since it is a subset of a candidate key. – Rx_rx# is a candidate key of PRESCRIPTION-A since it is an irreducible superkey of PRESCRIPTION-A. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 20

The Concept of Key/NON-KEY Attribute (continued) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 21

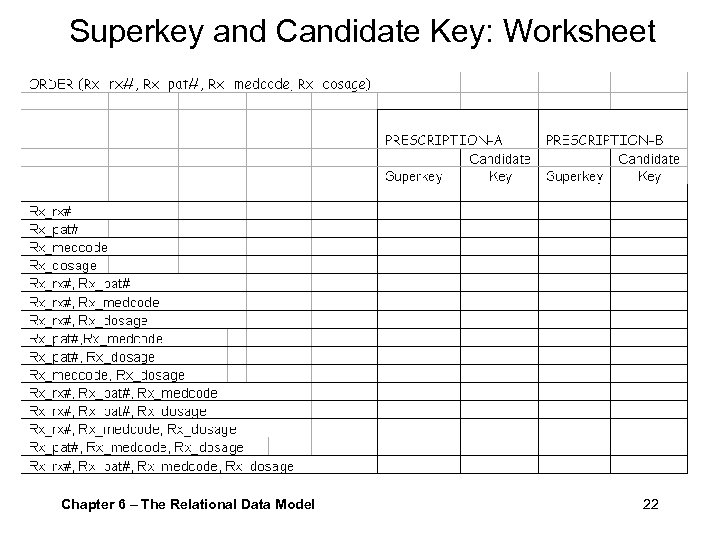

Superkey and Candidate Key: Worksheet Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 22

Superkey and Candidate Key: Examples Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 23

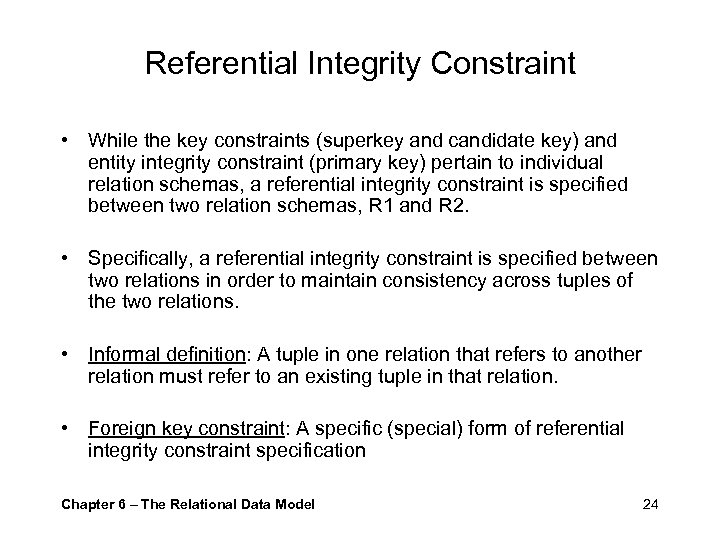

Referential Integrity Constraint • While the key constraints (superkey and candidate key) and entity integrity constraint (primary key) pertain to individual relation schemas, a referential integrity constraint is specified between two relation schemas, R 1 and R 2. • Specifically, a referential integrity constraint is specified between two relations in order to maintain consistency across tuples of the two relations. • Informal definition: A tuple in one relation that refers to another relation must refer to an existing tuple in that relation. • Foreign key constraint: A specific (special) form of referential integrity constraint specification Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 24

Foreign Key Constraint • Foreign Key Constraint Establishes an explicit association between two relation schemas and maintains the integrity of such an association • Foreign key: An attribute(s) set, A 2, in a relation schema R 2 that shares the same domain with a candidate key (A 1) of another relation schema R 1; A 2 is said to reference or refer to the relation schema R 1. Note: R 2 is known as the referencing relation and R 1 is called the referenced relation. The attribute(s) doing the referencing (A 2 in R 2) is the foreign key, while the candidate key being referenced (A 1 in R 1) is the referenced attribute(s). • Referred to as Inclusion Dependency, this constraint is algebraically expressed as: R 2. { A 2} C R 1. { A 1} Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 25

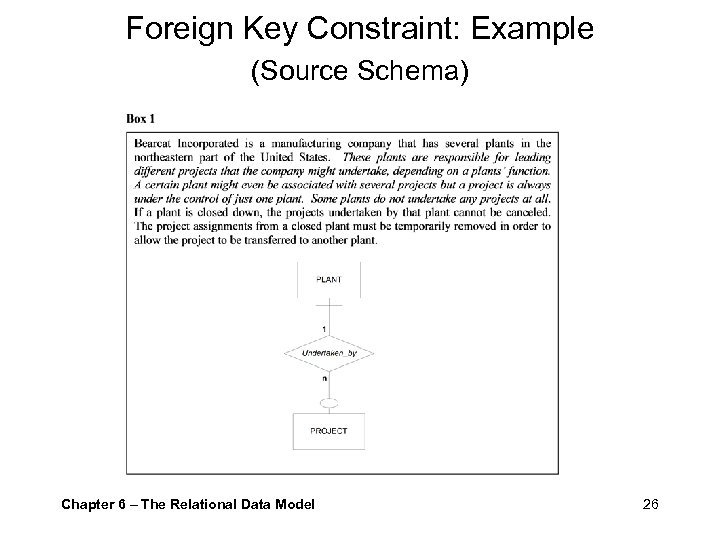

Foreign Key Constraint: Example (Source Schema) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 26

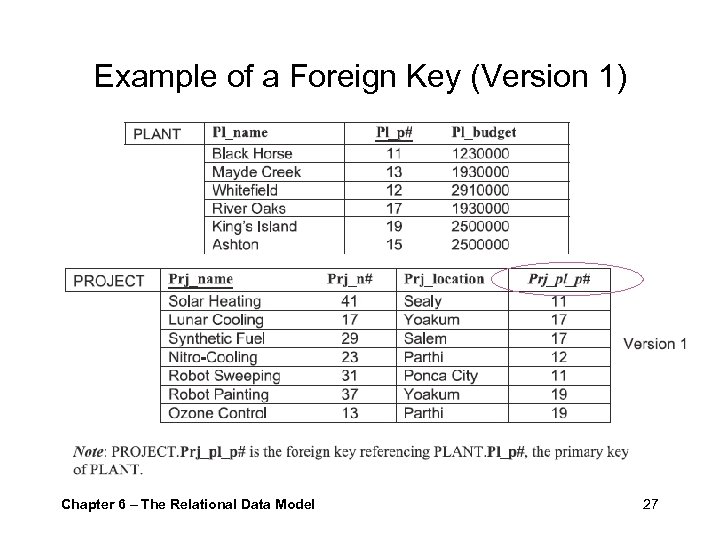

Example of a Foreign Key (Version 1) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 27

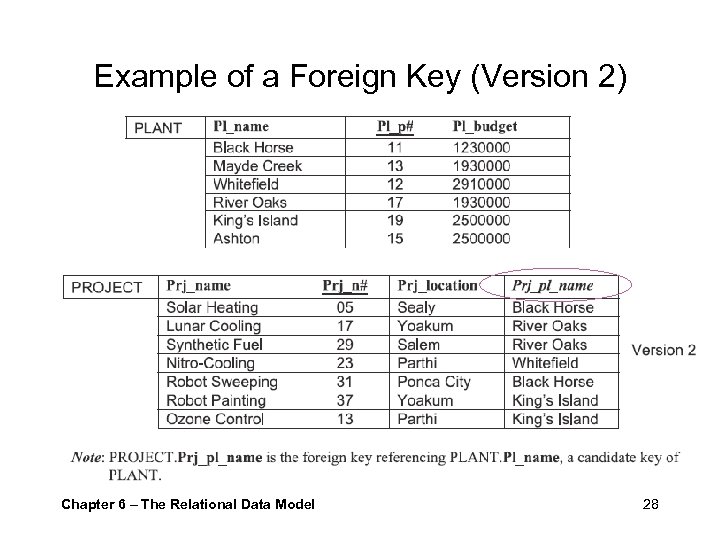

Example of a Foreign Key (Version 2) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 28

Naming Convention for Foreign Keys • The name of a foreign key attribute in the referencing relation schema consists of: – The prefix used for the attribute names in the referencing relation schema, – An underscore, and – The referenced attribute name Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 29

A Brief Introduction to Relational Algebra Selection (σ) : Selects all tuples that satisfy the selection condition from a relation R. Projection (π) : Produces a new relation with only some of the attributes of R, and removes duplicate tuples. Union (U) : Produces a relation that includes all the tuples in R 1 or R 2 or both R 1 and R 2; R 1 and R 2 must be union compatible. . Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 30

Introduction to Relational Algebra (continued) Intersection (∩) : Produces a relation that includes all the tuples in both R 1 and R 2; R 1 and R 2 must be union compatible. Difference (-) : Produces a relation that includes all the tuples in R 1 that are not in R 2; R 1 and R 2 must be union compatible. Natural Join (*) : Produces all the combinations of tuples from R 1 and R 2 that satisfy a join condition; R 1 and R 2 must be join compatible. . Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 31

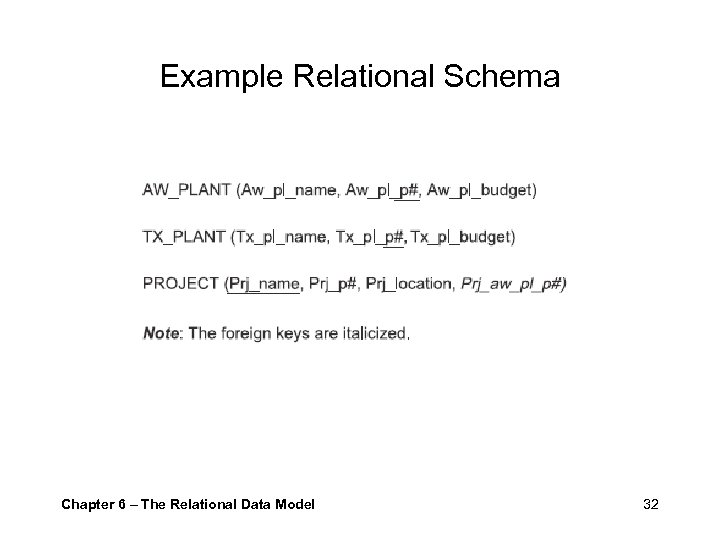

Example Relational Schema Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 32

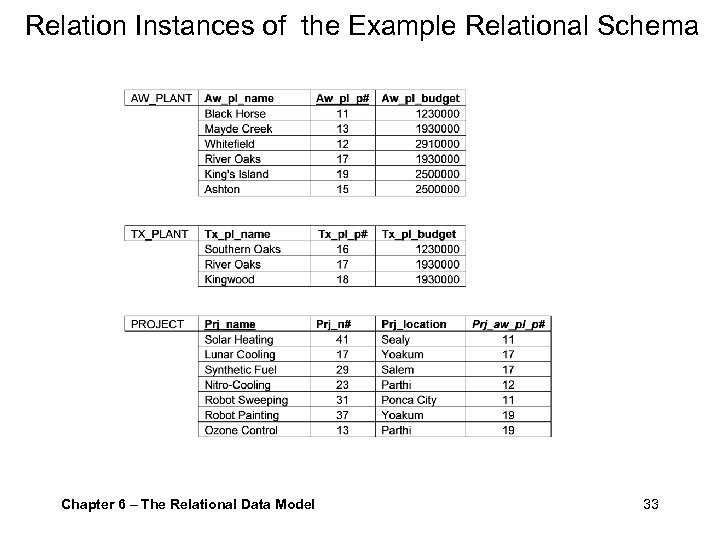

Relation Instances of the Example Relational Schema Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 33

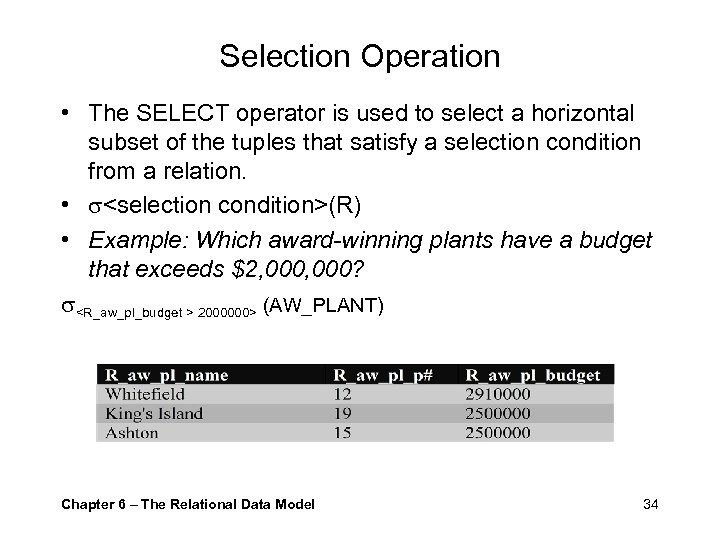

Selection Operation • The SELECT operator is used to select a horizontal subset of the tuples that satisfy a selection condition from a relation. • <selection condition>(R) • Example: Which award-winning plants have a budget that exceeds $2, 000? <R_aw_pl_budget > 2000000> (AW_PLANT) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 34

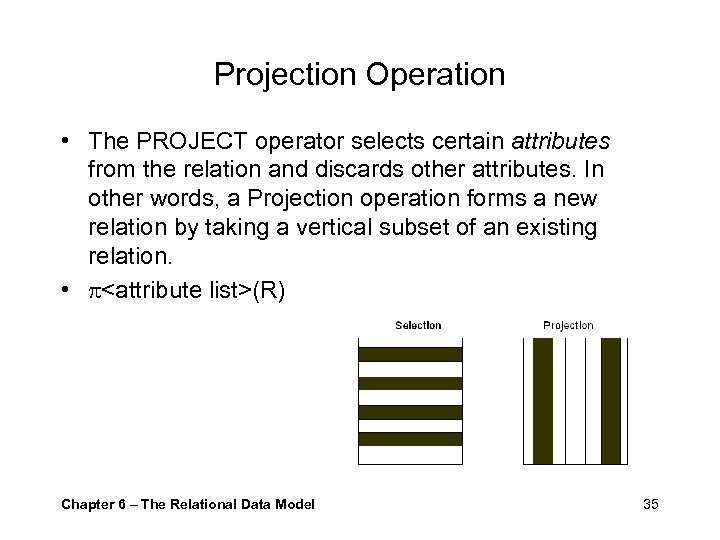

Projection Operation • The PROJECT operator selects certain attributes from the relation and discards other attributes. In other words, a Projection operation forms a new relation by taking a vertical subset of an existing relation. • <attribute list>(R) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 35

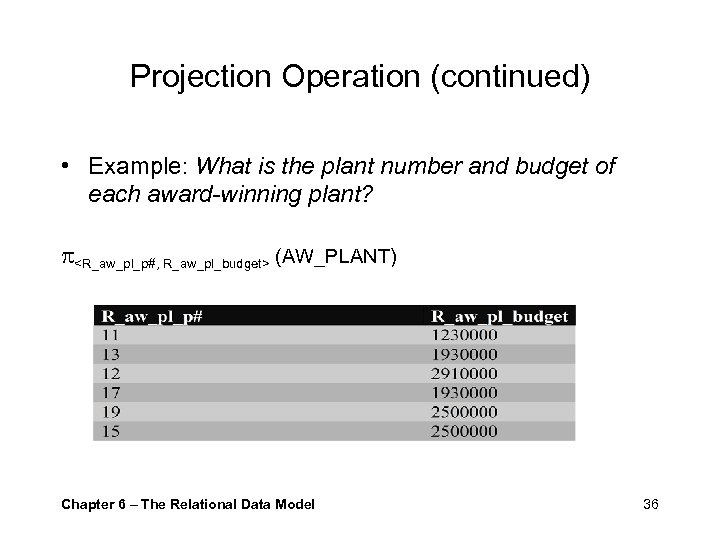

Projection Operation (continued) • Example: What is the plant number and budget of each award-winning plant? <R_aw_pl_p#, R_aw_pl_budget> (AW_PLANT) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 36

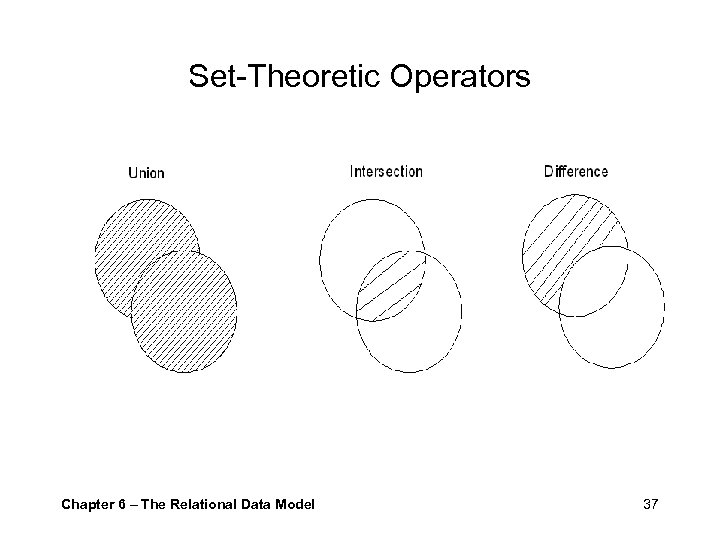

Set-Theoretic Operators Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 37

Union Compatibility in Set-Theoretic Operators Two relations R(A 1, A 2, …, An) and S(B 1, B 2, …, Bn) are said to be union compatible: – If they have the same degree (i. e. , have the same number of attributes) and – If the domain of Ai is equal to the domain of Bi for 1 i n (i. e. , corresponding attributes in R and S share the same domain) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 38

Set-Theoretic Operators Defined • Union (R S) Yields a relation that includes all tuples that are either exclusively in R or exclusively in S or in both R and S. That is, duplicate tuples are eliminated. • Intersection (R S) Yields a relation that includes all tuples that are in both R and S. • Difference (R – S) Yields a relation that includes all tuples that are in R but not in S. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 39

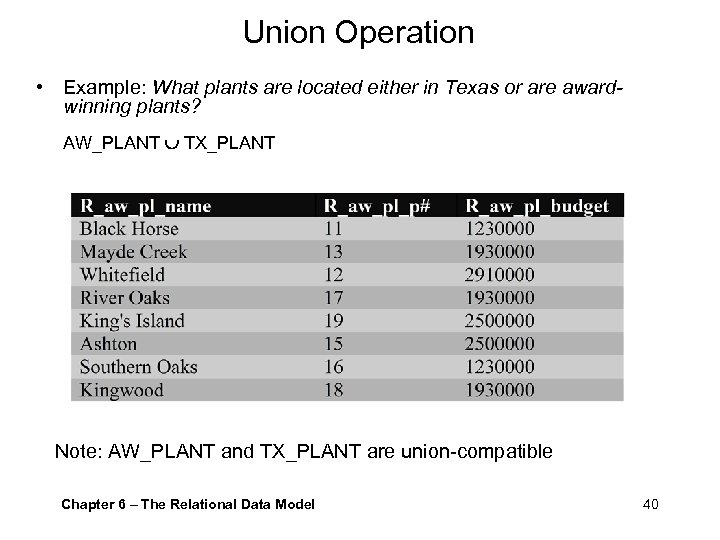

Union Operation • Example: What plants are located either in Texas or are awardwinning plants? AW_PLANT TX_PLANT Note: AW_PLANT and TX_PLANT are union-compatible Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 40

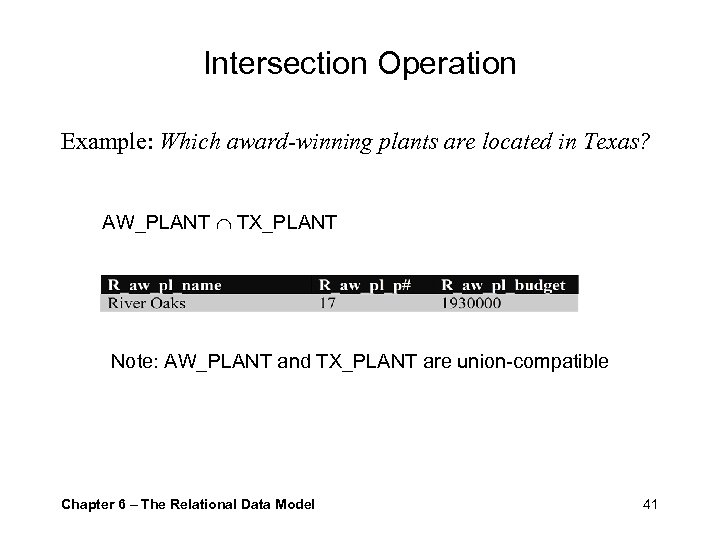

Intersection Operation Example: Which award-winning plants are located in Texas? AW_PLANT TX_PLANT Note: AW_PLANT and TX_PLANT are union-compatible Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 41

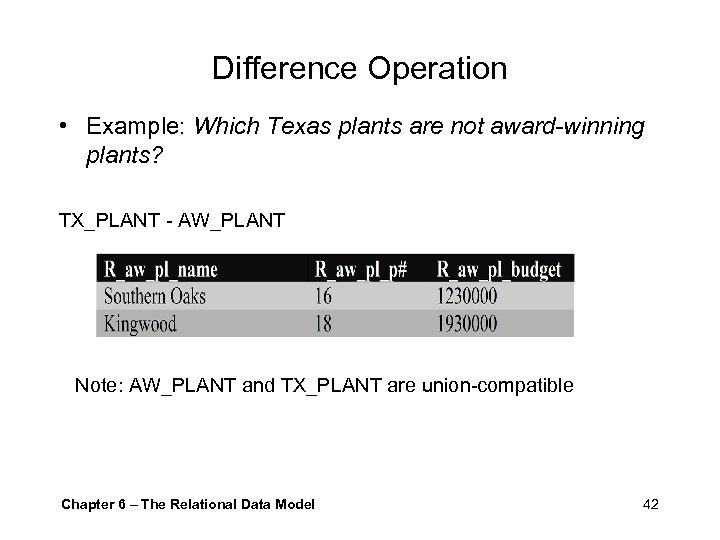

Difference Operation • Example: Which Texas plants are not award-winning plants? TX_PLANT - AW_PLANT Note: AW_PLANT and TX_PLANT are union-compatible Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 42

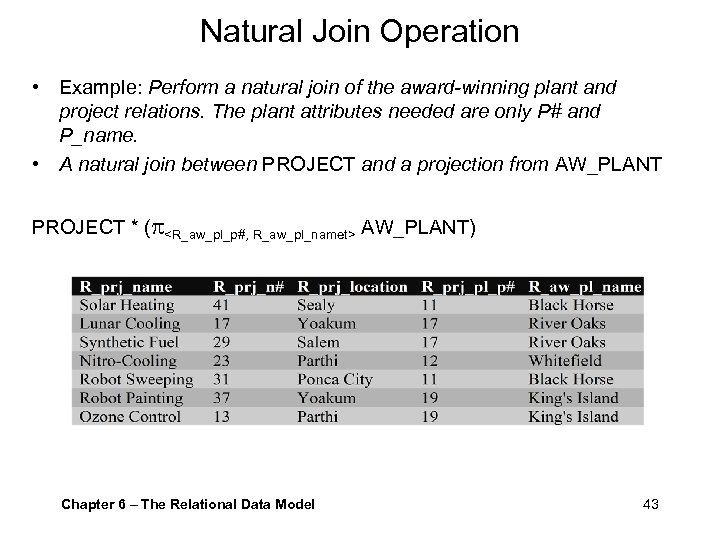

Natural Join Operation • Example: Perform a natural join of the award-winning plant and project relations. The plant attributes needed are only P# and P_name. • A natural join between PROJECT and a projection from AW_PLANT PROJECT * ( <R_aw_pl_p#, R_aw_pl_namet> AW_PLANT) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 43

Views • A view is a named ‘virtual’ relation schema constructed from one or more relation schemas. • Unlike a relation schema, a view does not store data. • A view is just a logical window used to ‘view’ selected data (attributes and tuples) from one or a set of relations. • The value of a view at any given time is a ‘derived’ relation state resulting from the evaluation of a specified relational expression (e. g. , join, project) at that time. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 44

Advantages of Views • Views allow the same data to be seen by different users in different ways at the same time. • Views provide security by restricting user access to a predetermined set of tuples and attributes from predetermined relations. • Views hide data complexity from the user. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 45

Mapping: ER Model → Logical Schema • More specifically: Mapping a Fine-granular Design. Specific ER model into a relational schema • The goal of any schema transformation method ought to be the preservation of the information capacity of the source data model (e. g. , ER model) in the target data model (e. g. , relational data model). Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 46

Mapping Entity Types • Create a relation schema for each base entity type in the ER diagram. • Create an attribute for every stored attribute. This implies: – For composite attributes only their constituent atomic components are recorded – Derived attributes are not recorded – Multi-valued attributes do not exist in a Fine-granular Design. Specific ER model • Choose a primary key from among the candidate keys by underlining the attribute(s) constituting the primary key. • For each weak entity type, add the primary key of the identifying parent entity type as attribute(s) in the relation schema. – The attribute(s) thus added plus the partial key of the weak entity type form the primary key of the relation schema representing the weak entity type. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 47

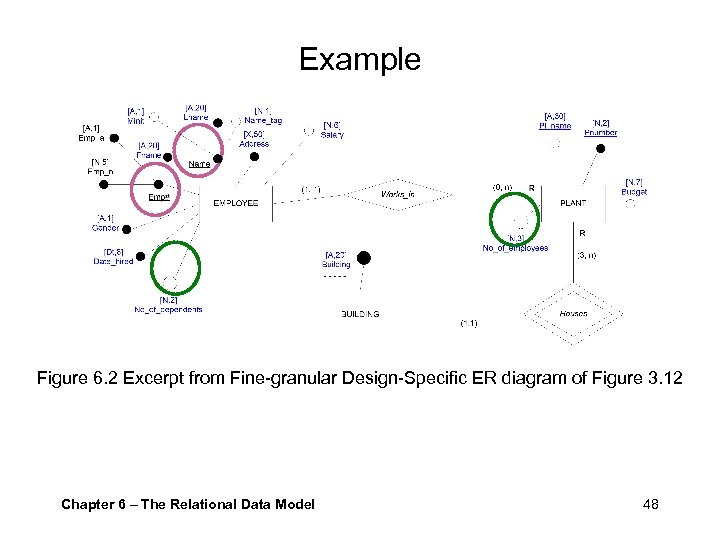

Example Figure 6. 2 Excerpt from Fine-granular Design-Specific ER diagram of Figure 3. 12 Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 48

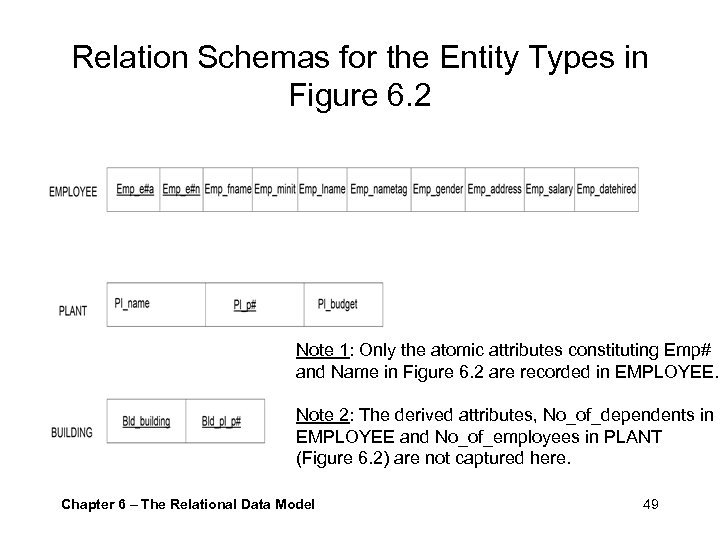

Relation Schemas for the Entity Types in Figure 6. 2 Note 1: Only the atomic attributes constituting Emp# and Name in Figure 6. 2 are recorded in EMPLOYEE. Note 2: The derived attributes, No_of_dependents in EMPLOYEE and No_of_employees in PLANT (Figure 6. 2) are not captured here. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 49

Mapping Relationship Types • Characteristic of the Design-Specific ER model: – Only binary or recursive relationships are present – Only 1: 1 or 1: n cardinality constraints are present • Relationship type mapped by enforcing a foreign key constraint between the relation schemas participating in the relationship type. • Remember: – A referential integrity constraint requires that the referenced attribute(s) exist in the referenced relation schema – The foreign key constraint requires that the referenced attribute(s) be a candidate key of the referenced relation. • Note: Participation constraints are not mapped. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 50

Mapping Cardinality Ratio of 1: n • Add a foreign key attribute to the referencing schema (Child in the relationship) – A foreign key must share the same domain with a candidate key in the referenced schema (Parent) – Best Practice: use primary key as the referenced attribute • Remember: – The entity type on the “many-side” of the relationship type is the referencing relation schema (“child”), – The entity type on the “one-side” is the referenced relation schema (“parent”). Notation: Directed arc emanating from a foreign key points to a candidate key/the primary key) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 51

![Mapping Relationship Types [Cardinality constraint of 1: n] Note: The foreign key in EMPLOYEE Mapping Relationship Types [Cardinality constraint of 1: n] Note: The foreign key in EMPLOYEE](https://present5.com/presentation/043f31197828e084cae58ad29f5de995/image-52.jpg)

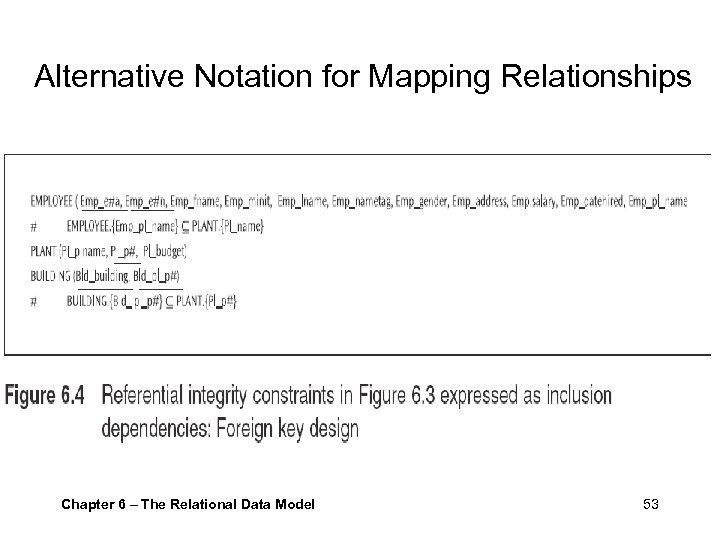

Mapping Relationship Types [Cardinality constraint of 1: n] Note: The foreign key in EMPLOYEE (Emp_pl_name) referencing PLANT is referring to a candidate key (Pl_name) of PLANT – not its primary key, while the foreign key in BUILDING (Bld_pl_p#) referencing PLANT is referring to the primary key (Pl_p#) of PLANT. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 52

Alternative Notation for Mapping Relationships Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 53

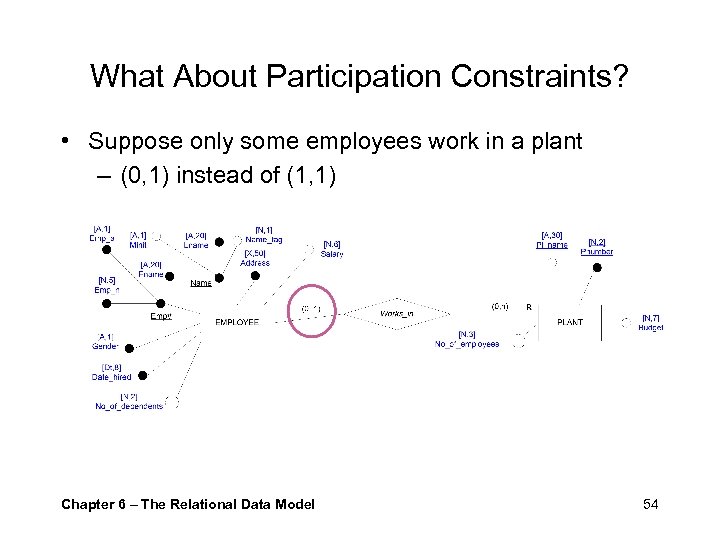

What About Participation Constraints? • Suppose only some employees work in a plant – (0, 1) instead of (1, 1) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 54

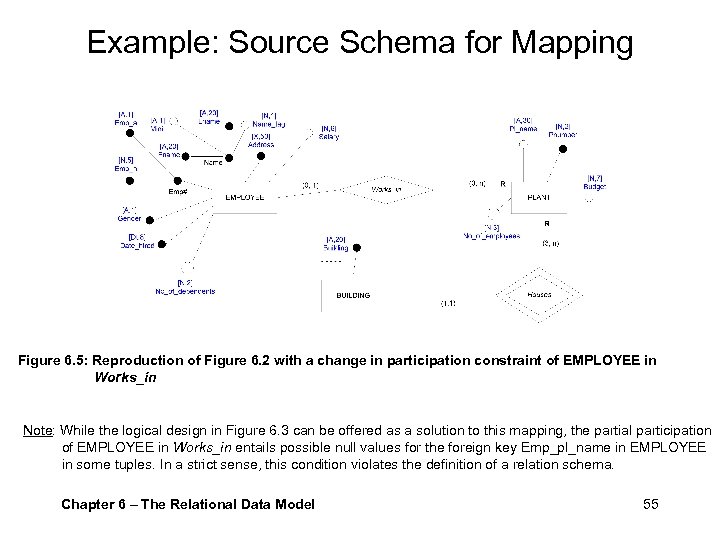

Example: Source Schema for Mapping Figure 6. 5: Reproduction of Figure 6. 2 with a change in participation constraint of EMPLOYEE in Works_in Note: While the logical design in Figure 6. 3 can be offered as a solution to this mapping, the partial participation of EMPLOYEE in Works_in entails possible null values for the foreign key Emp_pl_name in EMPLOYEE in some tuples. In a strict sense, this condition violates the definition of a relation schema. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 55

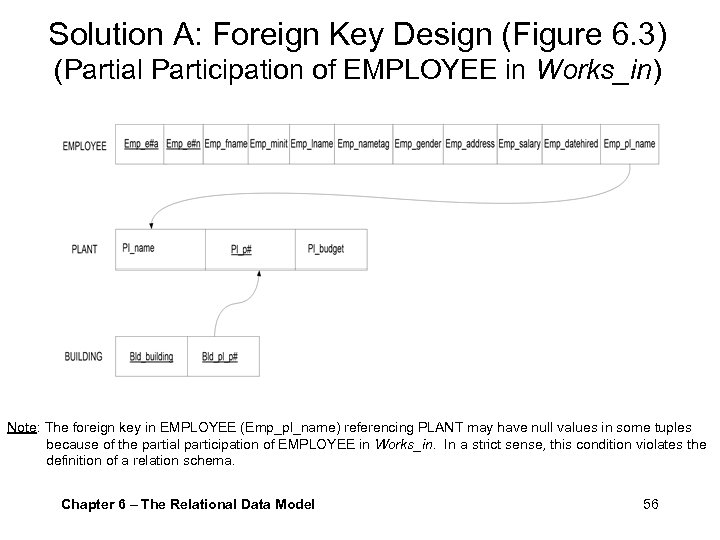

Solution A: Foreign Key Design (Figure 6. 3) (Partial Participation of EMPLOYEE in Works_in) Note: The foreign key in EMPLOYEE (Emp_pl_name) referencing PLANT may have null values in some tuples because of the partial participation of EMPLOYEE in Works_in. In a strict sense, this condition violates the definition of a relation schema. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 56

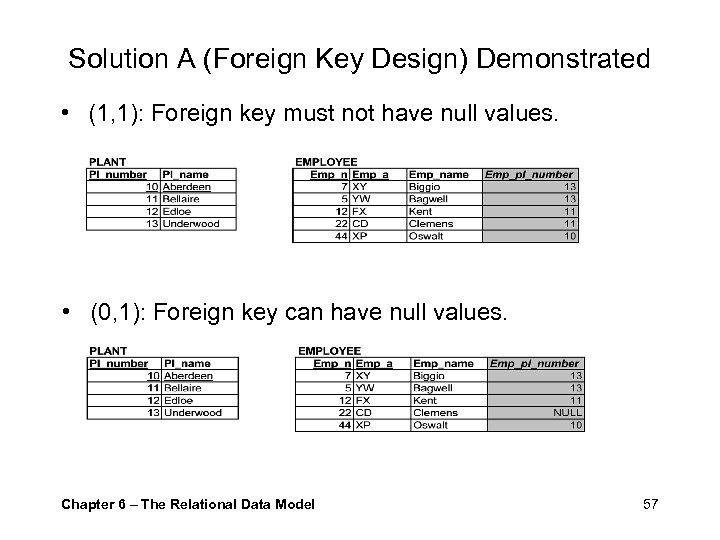

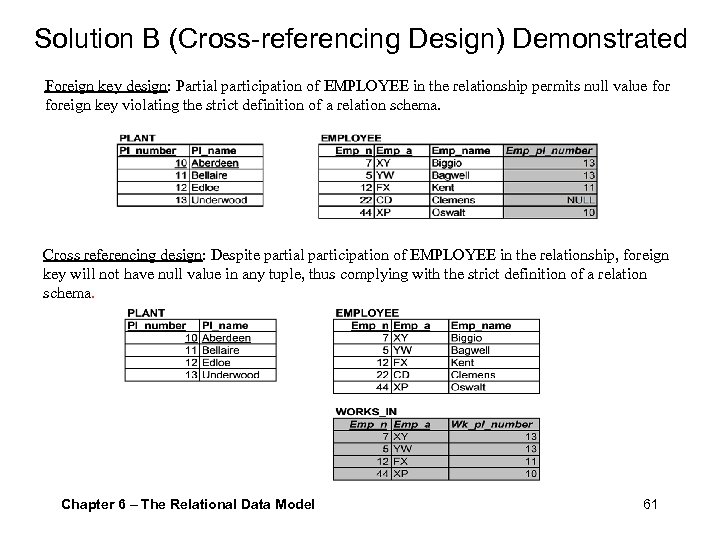

Solution A (Foreign Key Design) Demonstrated • (1, 1): Foreign key must not have null values. • (0, 1): Foreign key can have null values. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 57

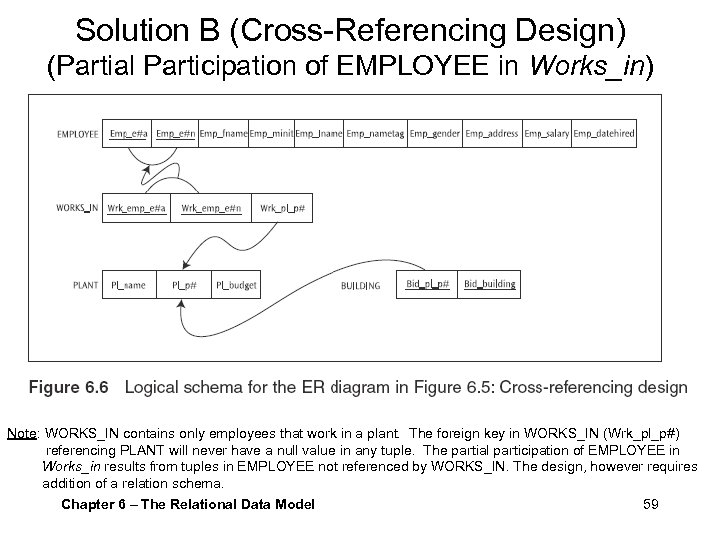

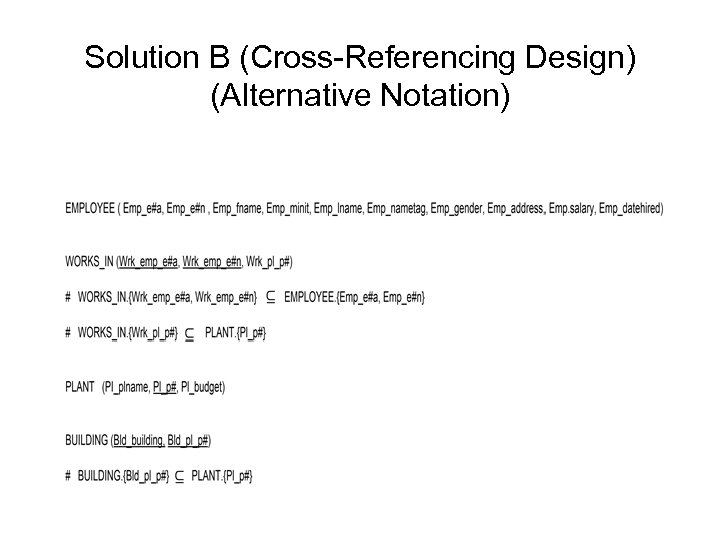

Solution B (Cross-Referencing Design) • Cross-referencing design: Create a separate relation schema representing the relationship type. – Tuples in the relation “WORKS_IN” represent only employees who actually work in a plant. – All tuples in “WORKS_IN” have corresponding employee tuples in the EMPLOYEE relation. – The EMPLOYEE relation may also contain additional tuples i. e. , tuples for employees who do not work in any plant. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 58

Solution B (Cross-Referencing Design) (Partial Participation of EMPLOYEE in Works_in) Note: WORKS_IN contains only employees that work in a plant. The foreign key in WORKS_IN (Wrk_pl_p#) referencing PLANT will never have a null value in any tuple. The partial participation of EMPLOYEE in Works_in results from tuples in EMPLOYEE not referenced by WORKS_IN. The design, however requires addition of a relation schema. 59 Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model

Solution B (Cross-Referencing Design) (Alternative Notation)

Solution B (Cross-referencing Design) Demonstrated Foreign key design: Partial participation of EMPLOYEE in the relationship permits null value foreign key violating the strict definition of a relation schema. Cross referencing design: Despite partial participation of EMPLOYEE in the relationship, foreign key will not have null value in any tuple, thus complying with the strict definition of a relation schema. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 61

Mapping Cardinality Ratio 1: 1 • Case 1: The participation of one of the entity types in the relationship type is total. • Case 2: The participation of both entity types in the relationship type is partial. • Case 3: The participation of both entity types in the relationship type is total. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 62

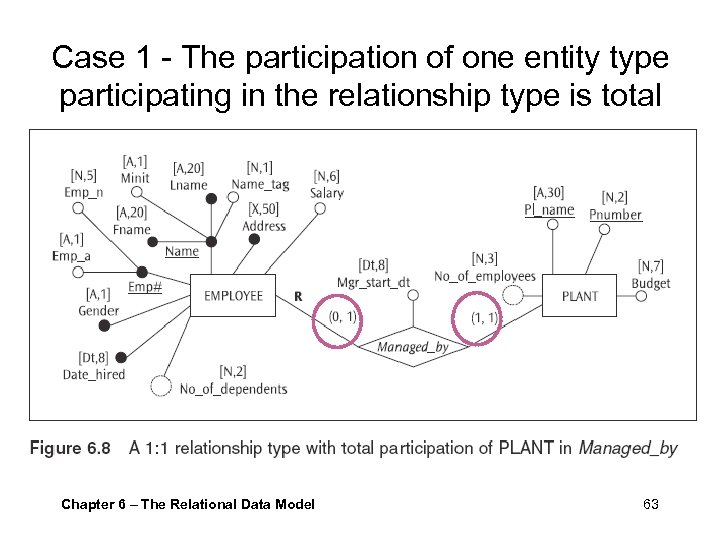

Case 1 - The participation of one entity type participating in the relationship type is total Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 63

Case 1 - The participation of one entity type participating in the relationship type is total Steps: • Choose the entity type with the total participation in the relationship to be the referencing relation schema (i. e. , child). • Foreign key must not have a null value. [Specification of total participation of child in the relationship] • Foreign key must be unique. [Specification of 1: 1 cardinality constraint] Add to constraints! • Add the foreign key to the child relation schema referencing the primary key (or an alternate key) in the referenced relation schema. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 64

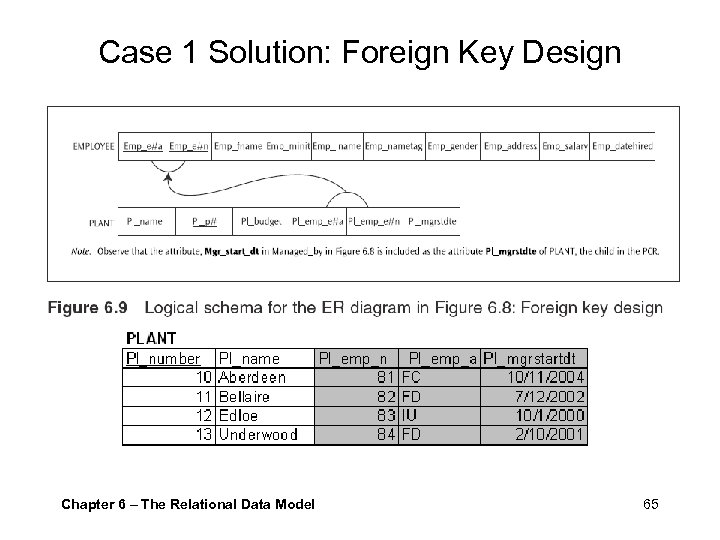

Case 1 Solution: Foreign Key Design Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 65

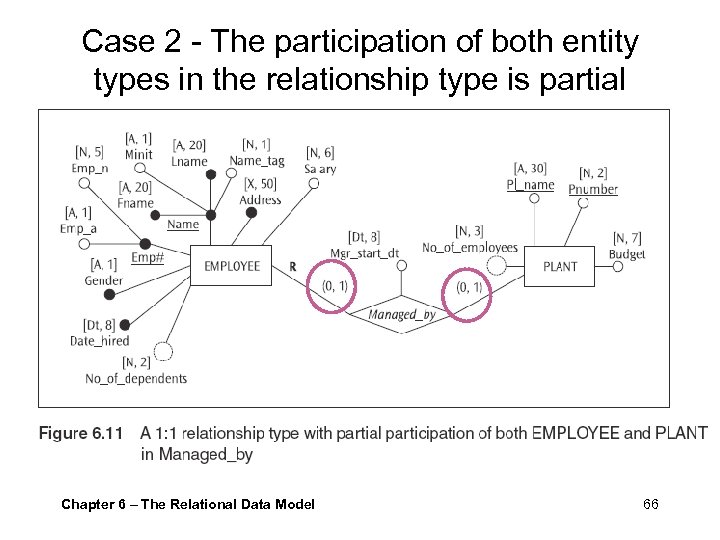

Case 2 - The participation of both entity types in the relationship type is partial Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 66

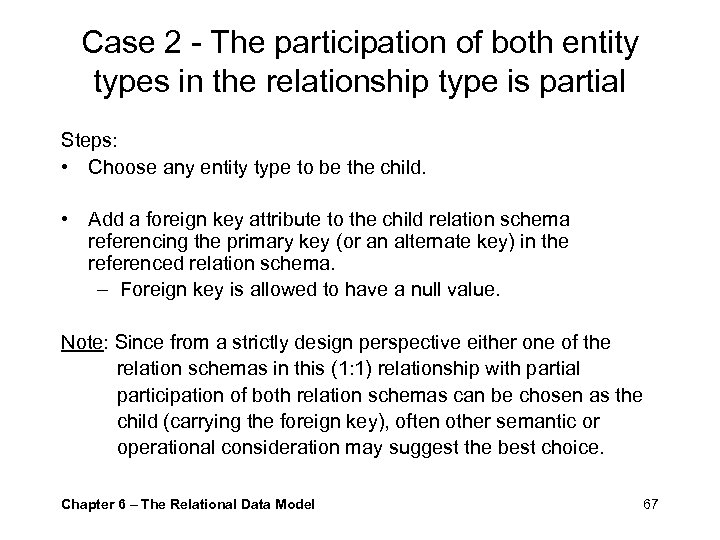

Case 2 - The participation of both entity types in the relationship type is partial Steps: • Choose any entity type to be the child. • Add a foreign key attribute to the child relation schema referencing the primary key (or an alternate key) in the referenced relation schema. – Foreign key is allowed to have a null value. Note: Since from a strictly design perspective either one of the relation schemas in this (1: 1) relationship with partial participation of both relation schemas can be chosen as the child (carrying the foreign key), often other semantic or operational consideration may suggest the best choice. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 67

Case 2 Solution: Foreign Key Design Note: In this design the foreign key may have null value in some tuples Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 68

![Case 2: An Alternative Solution [Cross-Referencing Design] • • Create a separate relation schema Case 2: An Alternative Solution [Cross-Referencing Design] • • Create a separate relation schema](https://present5.com/presentation/043f31197828e084cae58ad29f5de995/image-69.jpg)

Case 2: An Alternative Solution [Cross-Referencing Design] • • Create a separate relation schema representing the relationship type. Here, MANAGED_BY references PLANT as well as EMPLOYEE. Note: Foreign keys in MANAGED_BY will never have a null value in any tuple Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 69

Mutual Referencing Design • Can be used for both case 1 and case 2 • Since this is a (1: 1) relationship, both relation schemas can be parent as well as child. – Add foreign key to both relation schemas • Demerits: – Unnecessary to establish the relationship – Creates a cycle; so, enforcement of at least one of the referencing must be deferred until run time. – Entails specification of additional constraints for consistency maintenance across the relations • Merit: Can facilitate optimal data access Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 70

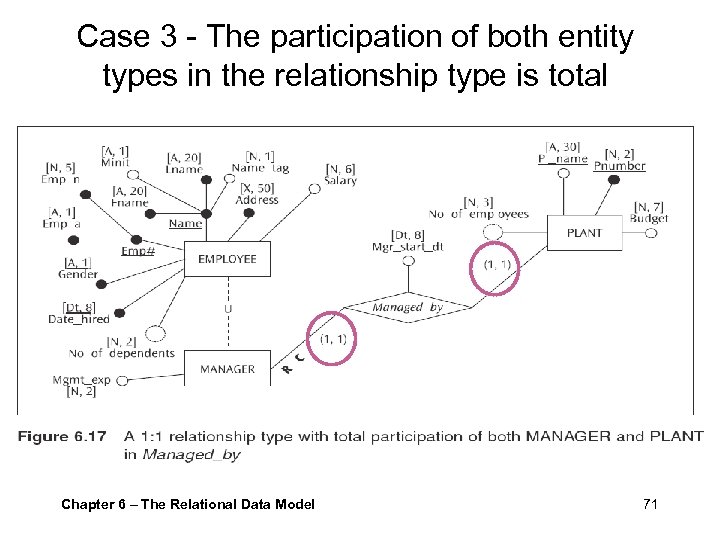

Case 3 - The participation of both entity types in the relationship type is total Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 71

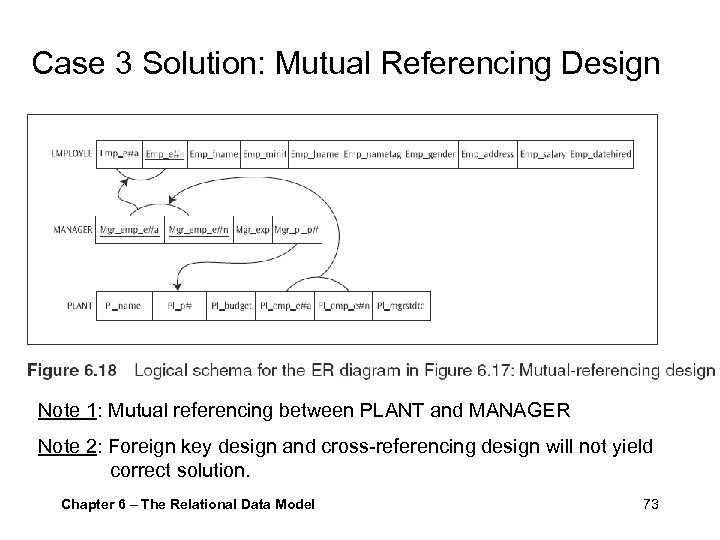

Case 3 - The participation of both entity types in the relationship type is total Steps • Use mutual referencing – i. e. , add a foreign key in both relation schemas. • Issues: {Require procedural intervention} – Consistency maintenance across the relation schemas – Mutual referencing creates a cycle requiring run-time resolution • Alternative Solution: Use a single-schema design (i. e. , collapse the two relation schemas into one) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 72

Case 3 Solution: Mutual Referencing Design Note 1: Mutual referencing between PLANT and MANAGER Note 2: Foreign key design and cross-referencing design will not yield correct solution. Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 73

Information Lost in the Mapping Process • Both methods (Directed arc and Inclusion dependency) are incapable of distinguishing between 1: 1 and 1: n cardinality ratios • Both methods do not map the participation constraints of a relationship type • The optional/mandatory property of an attribute is not retained in the transformation • Alternate keys (candidate keys not chosen as the primary key) can no longer be identified Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 74

Information Lost in the Mapping Process (continued) • The composite nature of some collection of atomic attributes is ignored in the mapping process • Derived attributes specified in the ER diagram are not carried forward • Deletion rules are not mapped to the logical schema • Attribute type and size specified in the ER diagram are not carried forward Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 75

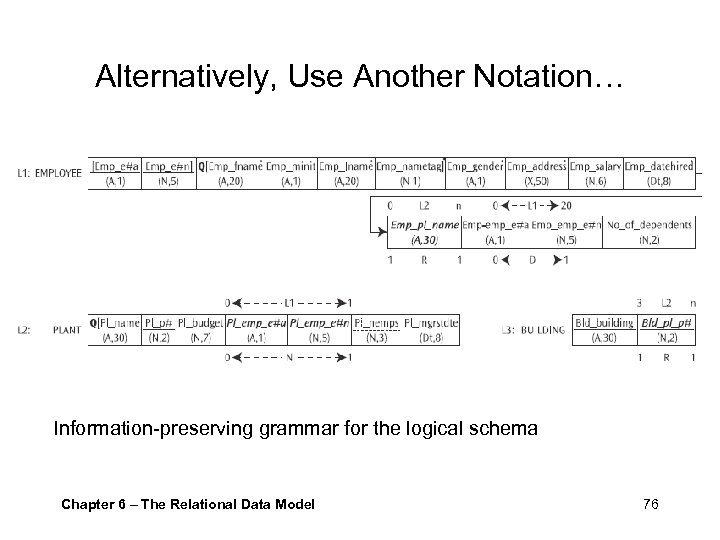

Alternatively, Use Another Notation… Information-preserving grammar for the logical schema Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 76

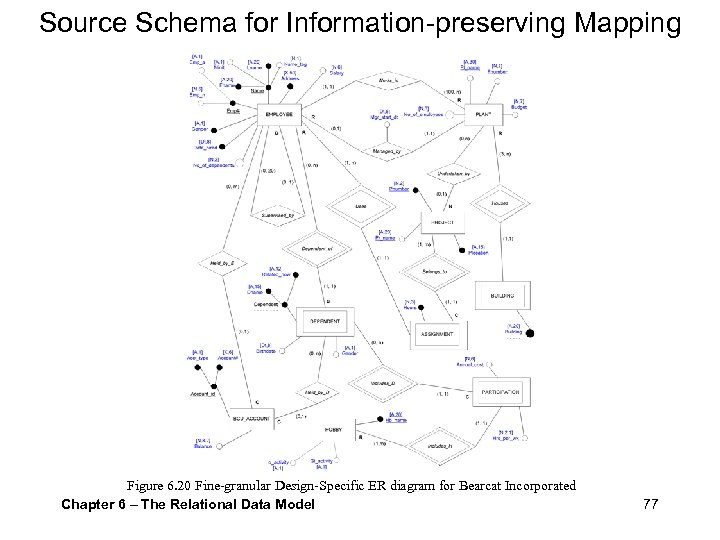

Source Schema for Information-preserving Mapping Figure 6. 20 Fine-granular Design-Specific ER diagram for Bearcat Incorporated Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 77

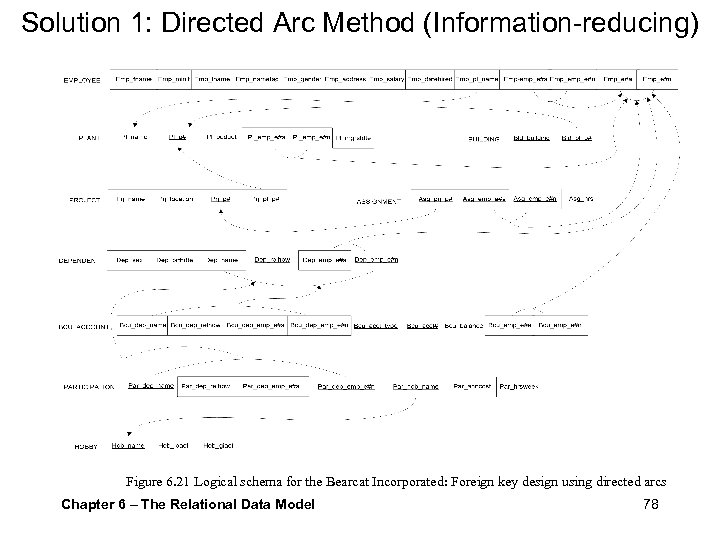

Solution 1: Directed Arc Method (Information-reducing) Figure 6. 21 Logical schema for the Bearcat Incorporated: Foreign key design using directed arcs Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 78

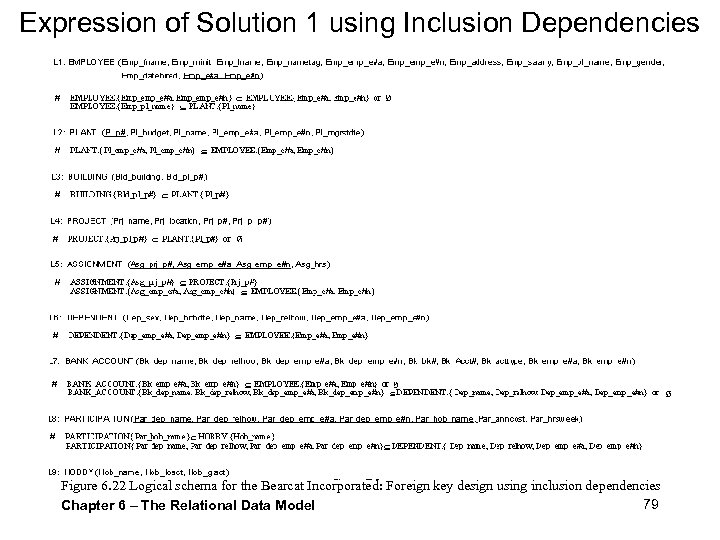

Expression of Solution 1 using Inclusion Dependencies Figure 6. 22 Logical schema for the Bearcat Incorporated: Foreign key design using inclusion dependencies 79 Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model

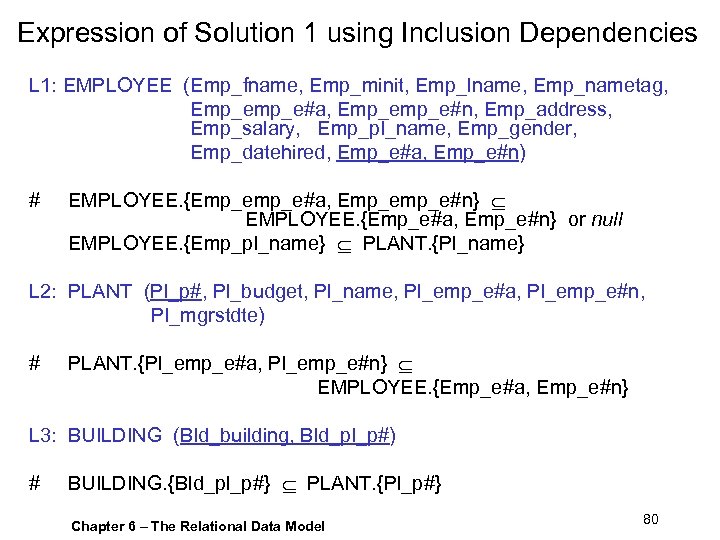

Expression of Solution 1 using Inclusion Dependencies L 1: EMPLOYEE (Emp_fname, Emp_minit, Emp_lname, Emp_nametag, Emp_e#a, Emp_e#n, Emp_address, Emp_salary, Emp_pl_name, Emp_gender, Emp_datehired, Emp_e#a, Emp_e#n) # EMPLOYEE. {Emp_e#a, Emp_e#n} or null EMPLOYEE. {Emp_pl_name} PLANT. {Pl_name} L 2: PLANT (Pl_p#, Pl_budget, Pl_name, Pl_emp_e#a, Pl_emp_e#n, Pl_mgrstdte) # PLANT. {Pl_emp_e#a, Pl_emp_e#n} EMPLOYEE. {Emp_e#a, Emp_e#n} L 3: BUILDING (Bld_building, Bld_pl_p#) # BUILDING. {Bld_pl_p#} PLANT. {Pl_p#} Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 80

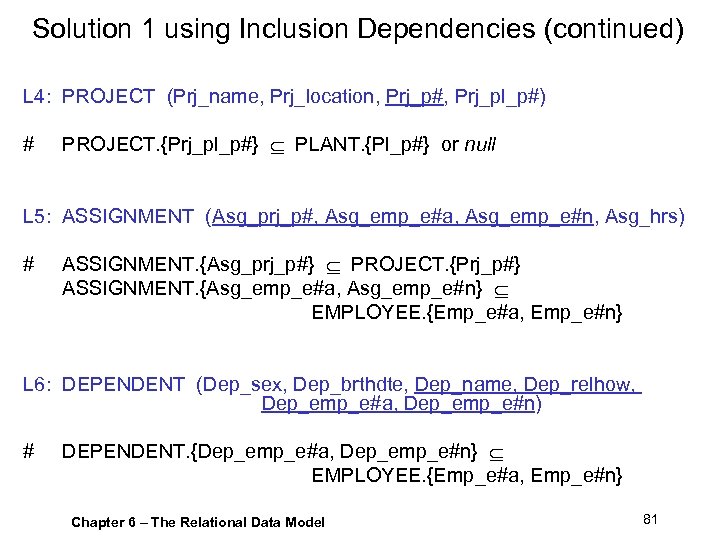

Solution 1 using Inclusion Dependencies (continued) L 4: PROJECT (Prj_name, Prj_location, Prj_p#, Prj_pl_p#) # PROJECT. {Prj_pl_p#} PLANT. {Pl_p#} or null L 5: ASSIGNMENT (Asg_prj_p#, Asg_emp_e#a, Asg_emp_e#n, Asg_hrs) # ASSIGNMENT. {Asg_prj_p#} PROJECT. {Prj_p#} ASSIGNMENT. {Asg_emp_e#a, Asg_emp_e#n} EMPLOYEE. {Emp_e#a, Emp_e#n} L 6: DEPENDENT (Dep_sex, Dep_brthdte, Dep_name, Dep_relhow, Dep_emp_e#a, Dep_emp_e#n) # DEPENDENT. {Dep_emp_e#a, Dep_emp_e#n} EMPLOYEE. {Emp_e#a, Emp_e#n} Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 81

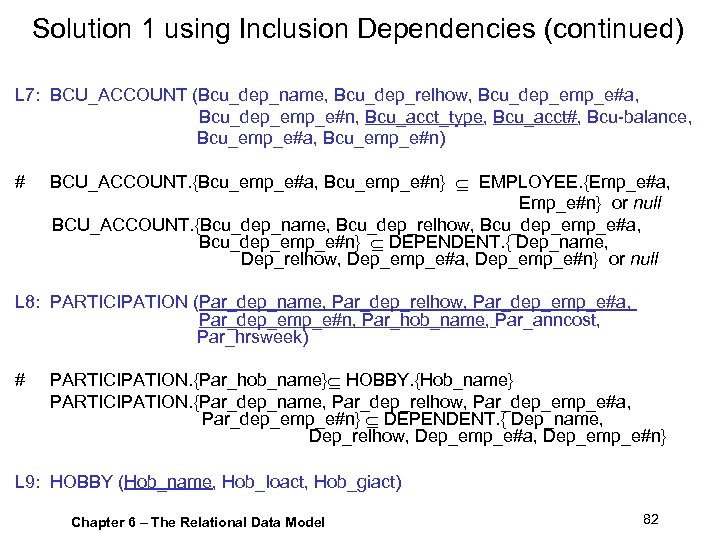

Solution 1 using Inclusion Dependencies (continued) L 7: BCU_ACCOUNT (Bcu_dep_name, Bcu_dep_relhow, Bcu_dep_emp_e#a, Bcu_dep_emp_e#n, Bcu_acct_type, Bcu_acct#, Bcu-balance, Bcu_emp_e#a, Bcu_emp_e#n) # BCU_ACCOUNT. {Bcu_emp_e#a, Bcu_emp_e#n} EMPLOYEE. {Emp_e#a, Emp_e#n} or null BCU_ACCOUNT. {Bcu_dep_name, Bcu_dep_relhow, Bcu_dep_emp_e#a, Bcu_dep_emp_e#n} DEPENDENT. { Dep_name, Dep_relhow, Dep_emp_e#a, Dep_emp_e#n} or null L 8: PARTICIPATION (Par_dep_name, Par_dep_relhow, Par_dep_emp_e#a, Par_dep_emp_e#n, Par_hob_name, Par_anncost, Par_hrsweek) # PARTICIPATION. {Par_hob_name} HOBBY. {Hob_name} PARTICIPATION. {Par_dep_name, Par_dep_relhow, Par_dep_emp_e#a, Par_dep_emp_e#n} DEPENDENT. { Dep_name, Dep_relhow, Dep_emp_e#a, Dep_emp_e#n} L 9: HOBBY (Hob_name, Hob_Ioact, Hob_giact) Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 82

Solution 2: Information-preserving Mapping Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 83

Mapping EER Constructs • Mapping a specialization/generalization hierarchy and lattice • Mapping a categorization • Mapping an aggregation Remember: • SC/sc relationships always have a cardinality ratio of 1: 1 • The participation of a subclass in the relationship is always total Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 84

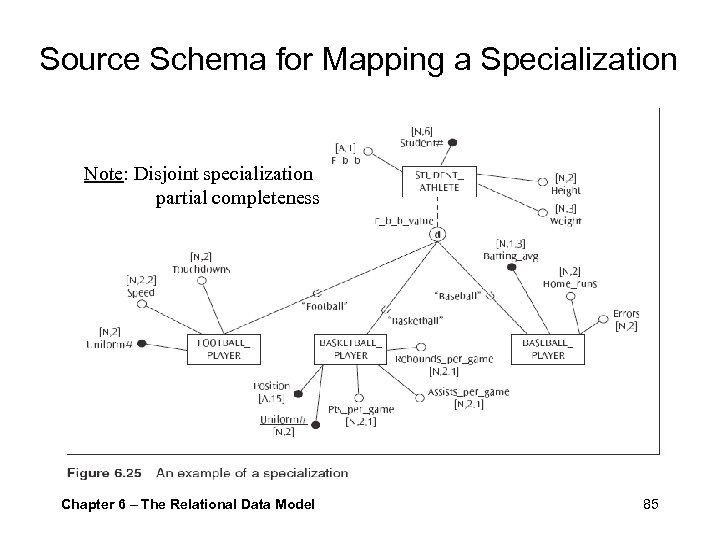

Source Schema for Mapping a Specialization Note: Disjoint specialization partial completeness Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 85

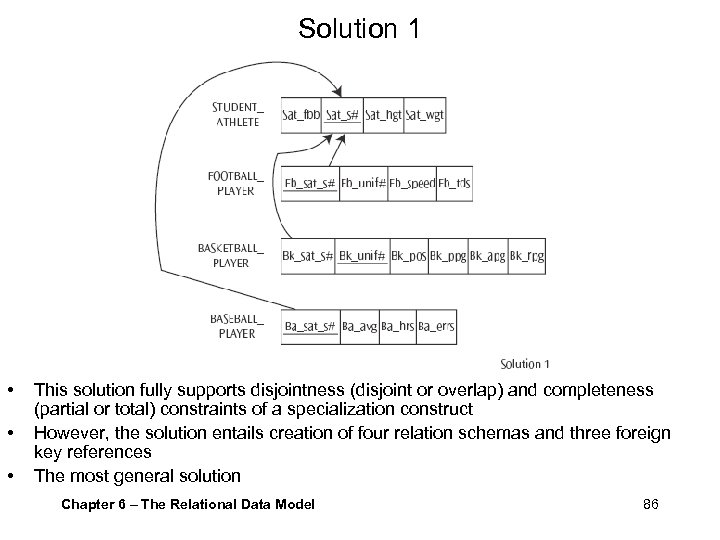

Solution 1 • • • This solution fully supports disjointness (disjoint or overlap) and completeness (partial or total) constraints of a specialization construct However, the solution entails creation of four relation schemas and three foreign key references The most general solution Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 86

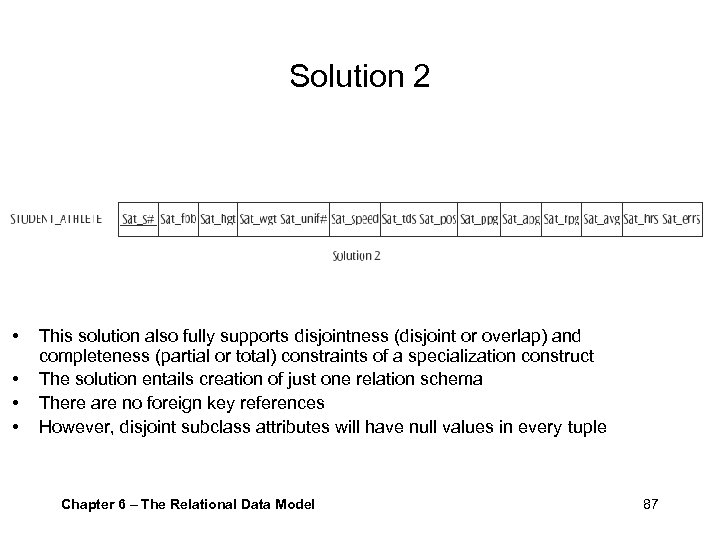

Solution 2 • • This solution also fully supports disjointness (disjoint or overlap) and completeness (partial or total) constraints of a specialization construct The solution entails creation of just one relation schema There are no foreign key references However, disjoint subclass attributes will have null values in every tuple Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 87

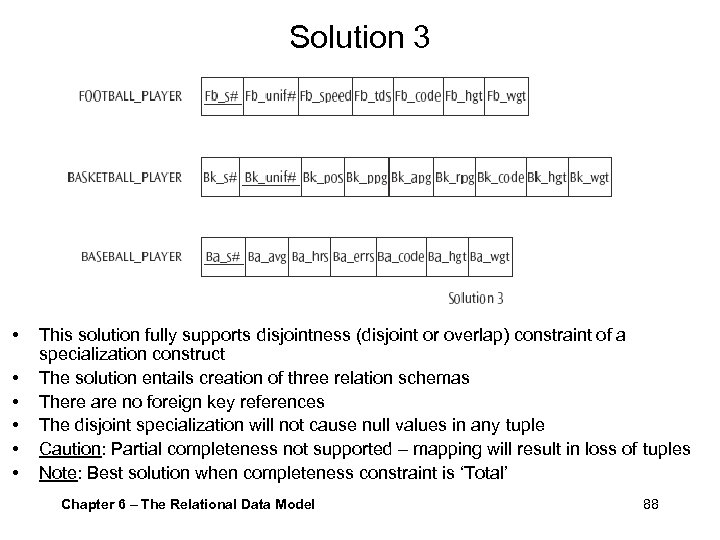

Solution 3 • • • This solution fully supports disjointness (disjoint or overlap) constraint of a specialization construct The solution entails creation of three relation schemas There are no foreign key references The disjoint specialization will not cause null values in any tuple Caution: Partial completeness not supported – mapping will result in loss of tuples Note: Best solution when completeness constraint is ‘Total’ Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 88

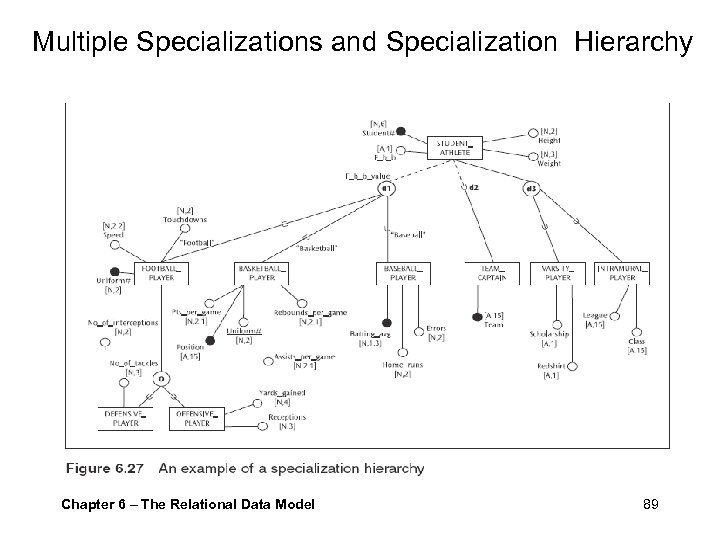

Multiple Specializations and Specialization Hierarchy Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 89

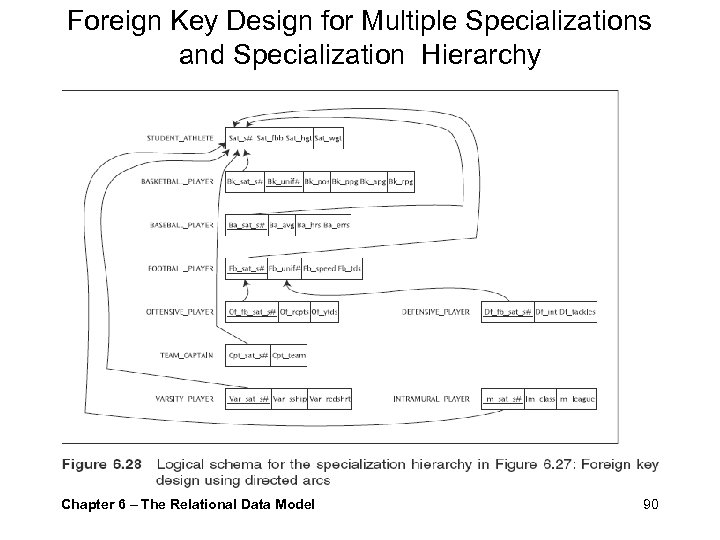

Foreign Key Design for Multiple Specializations and Specialization Hierarchy Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 90

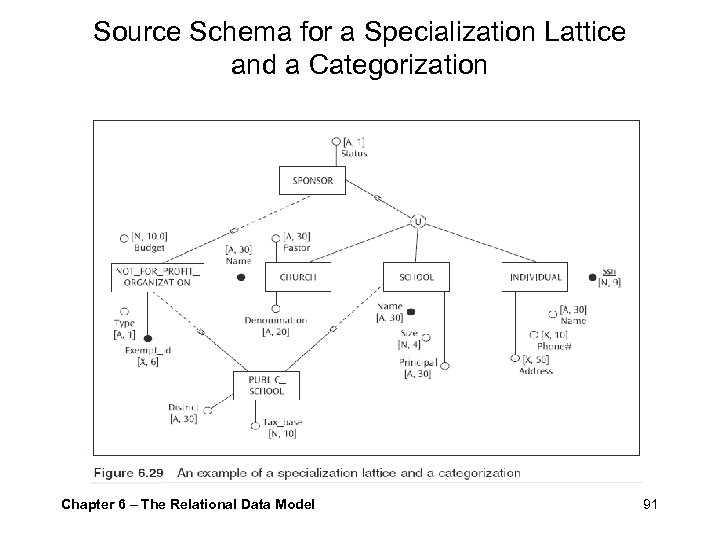

Source Schema for a Specialization Lattice and a Categorization Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 91

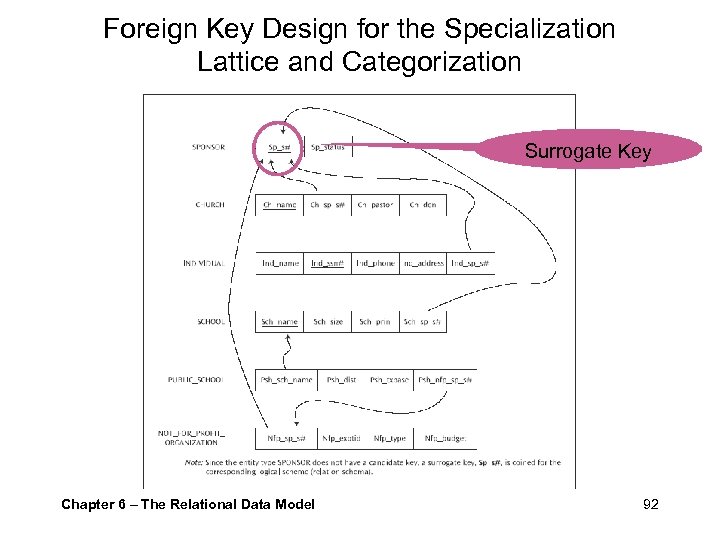

Foreign Key Design for the Specialization Lattice and Categorization Surrogate Key Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 92

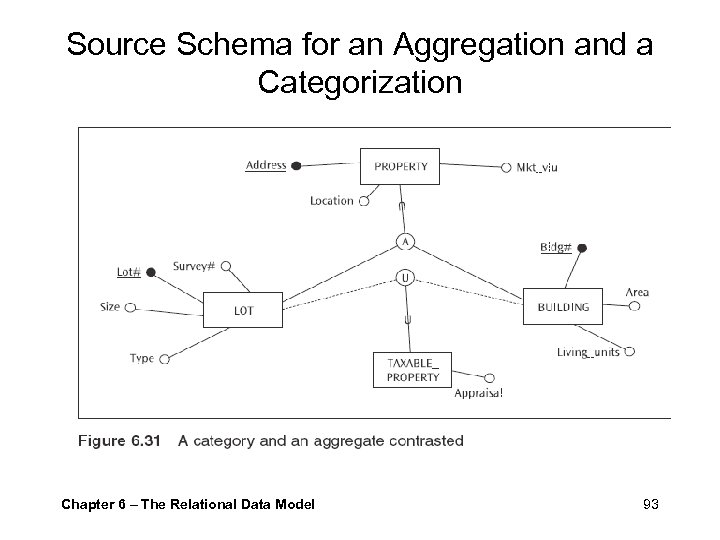

Source Schema for an Aggregation and a Categorization Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 93

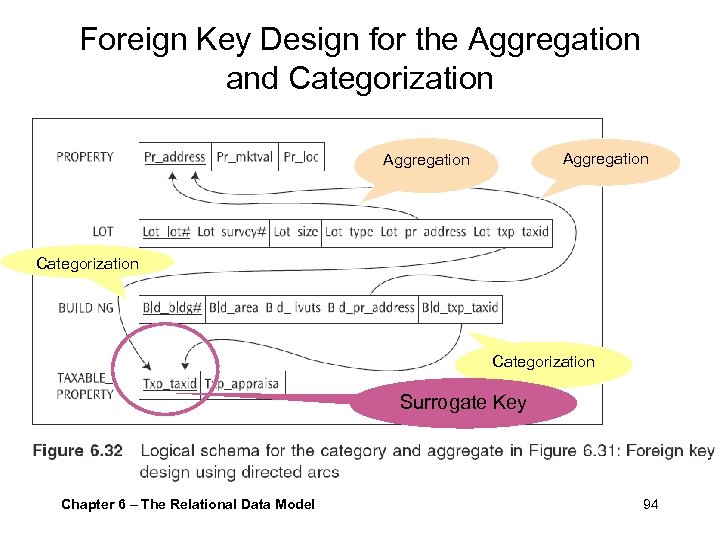

Foreign Key Design for the Aggregation and Categorization Aggregation Categorization Surrogate Key Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 94

Information Lost in EER Mapping • The type of relationship (e. g. , specialization/generalization, categorization, aggregation) is not carried forward to the logical schema • SC/sc relationships (i. e. , intra-entity class relationships) become indistinguishable from the regular (i. e. , inter-entity class) relationships • The disjointness constraint of a specialization/generalization is lost during the conversion process Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 95

Information Lost in EER Mapping (continued) • Multiple specializations of the same superclass are not captured • Specialization lattices are not discernible • The number of subclasses participating in a specialization and the number of superclasses participating in a categorization and/or aggregation is lost in the mapping • The completeness constraint of a SC/sc relationship is not present in the logical schema Chapter 6 – The Relational Data Model 96

043f31197828e084cae58ad29f5de995.ppt