f9bb50f733ac229d374ed4f823315bad.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 69

“Currency Board Systems and Hong Kong’s Evolving Arrangements” Professor Tsang Shu-ki Department of Economics Hong Kong Baptist University www. sktsang. com A presentation at the Central Banking Course Hong Kong Monetary Authority 29 September 2009 1

Outline of the talk (1) I. III. IV. How can an exchange rate be fixed? History of currency boards Classical currency boards and modern monetary economy V. Modern currency boards and the AEL Model 2

Outline of the talk (2) VI. Hong Kong’s currency board system before and after the seven technical measures of 9/1998 VII. Hong Kong’s currency board system and the three refinements of 5/2005 VIII. The prospects for currency boards References 3

I. How can an exchange rate be fixed? (1) • I. a) b) Basically there are two ways to do so, assuming that a fixed exchange rate regime is desirable (which in itself is a separate issue). Government controls and intervention Foreign exchange controls: e. g. China and Malaysia. Foreign exchange market intervention by the central bank: difficult for an economy with large capital flows, e. g. Bank of England in 1992. 4

I. How can an exchange rate be fixed? (2) II. Market-driven methods a) The Gold Standard (黃金本位制 ): late 19 th Century and early 20 th Century b) Currency Boards (貨幣局 ): previously mainly in British colonies; now in Hong Kong, Estonia, Lithuania, Bulgaria etc. (Argentina adopted the system in 1991 but abandoned it in early 2002. ) 5

I. How can an exchange rate be fixed? (3) • Both II (a) and (b) depend on self-interested market force to fix the exchange rate, without the need for government controls or intervention. The key activity is arbitrage (套戥 ). If the prices for the same product in two sub-markets differ from each other, then any market participant can buy the product at a lower price in one sub-market, and sell the product in the other at a higher price. A profit will be obtained at no risk. As many market participants perform similar arbitrage, the two prices should equalise, provided that the transaction cost is negligible. 6

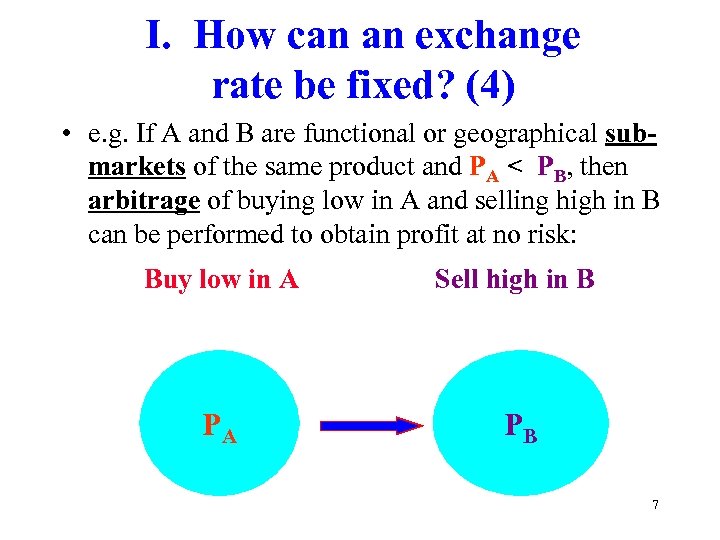

I. How can an exchange rate be fixed? (4) • e. g. If A and B are functional or geographical submarkets of the same product and PA < PB, then arbitrage of buying low in A and selling high in B can be performed to obtain profit at no risk: • Buy low in A PA Sell high in B PB 7

I. How can an exchange rate be fixed? (5) • If the price, say PA, in one sub-market can be firmly locked, because of sufficient reserves of the party that fixes it, the price in the other submarket, PB, will converge to PA, subject to the transaction cost (交易成本 ). That was how the Gold Standard worked. That is how the currency board system is supposed to work, although A and PA refer to a different component and its price in the “monetary base” (貨幣基礎 ). 8

II. History of currency boards (1) • The first currency board was set up in Mauritius in the 19 th Century: to be exact 1849. Dozens of economies---many former colonies of Britain, e. g. Falkland Islands, Malaya, Singapore, ---adopted the system. It worked well in fixing their exchange rates. 9

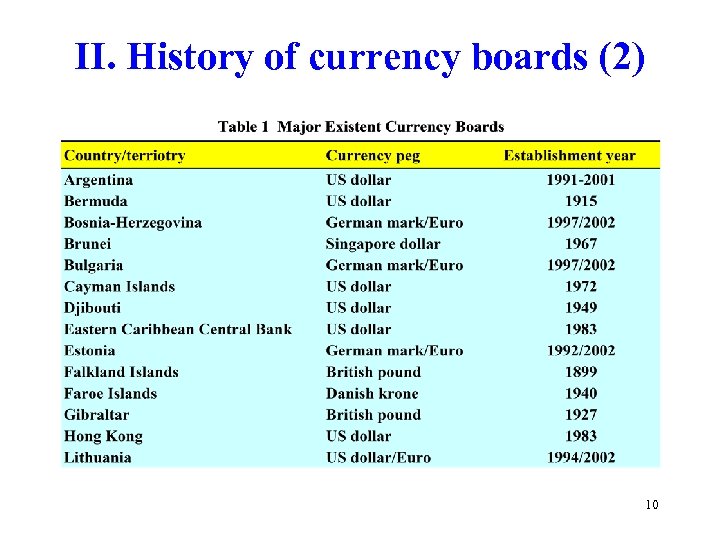

II. History of currency boards (2) 10

III. Classical currency boards (1) • The idea is surprisingly simple. A “currency board” issues currency notes (paper money), and trivially coins, with 100 per cent foreign reserves backing at a fixed exchange rate. This represents a strong commitment to economic discipline (經濟紀律 ). Any holder of paper money therefore rests assured that he can exchange his notes into foreign currency at the fixed rate. 11

III. Classical currency boards (2) • In a modern financial system, people hold much more than paper money. Bank deposits typically exceed currency notes by ten to twenty times. No currency boards can have reserves that fully match bank deposits. Hong Kong's foreign currency reserves (being the 8 th largest in the world) are about 41% of the total amount of notes and coins and deposits in Hong Kong dollar. 12

III. Classical currency boards (3) • How is the exchange rate of bank deposits fixed? Like the gold standard, it is through arbitrage. First, if there is speculation against the currency, funds will flow out of the economy and domestic interest rates will rise. This should attract back the funds; and the exchange rate can be stabilised. Such a phenomenon is called “specie flow”, or interest rate arbitrage (利率套戥 ). 13

III. Classical currency boards (4) • However, in a time of crisis, it is doubtful whether higher interest rates alone could fix the exchange rate. Hence a more important form of arbitrage, i. e. currency/exchange rate arbitrage (匯率套戥 ), is necessary. Since the exchange rate of paper money is fixed, the exchange rate of bank deposits has to follow suit. Any rate differential gives rise to profitable activity of cash arbitrage (現鈔套戥 ), that closes the gap. 14

III. Classical currency boards (5) • Take Hong Kong’s system since 1983 as a theoretical example. Since HK$ notes are issued against certificates of indebtedness (CIs) backed by US$ at the rate of 7. 80, if the market rate of deposit weakens to say 8. 00 against the US dollar, anyone can theoretically withdraw cash from his HK dollar deposit account, surrender the paper money through the NIBs or other banks to the "currency board" (the Exchange Fund) and get US$ at the fixed but stronger rate of 7. 80. 15

III. Classical currency boards (6) • With HK$ 7. 8 million in cash, he will be given US$ 1 million. By selling the US$ 1 million in the market, he fetches HK$ 8 million. So he obtains a profit of HK$ 200, 000. That is arbitrage, risk-free (無風險 ), except that there may be transaction costs. Many others will want to do the same. The selling pressure on the US dollar will push the market rate back to 7. 80, i. e. , equalising prices in the two submarkets (the cash market and the deposit market). 16

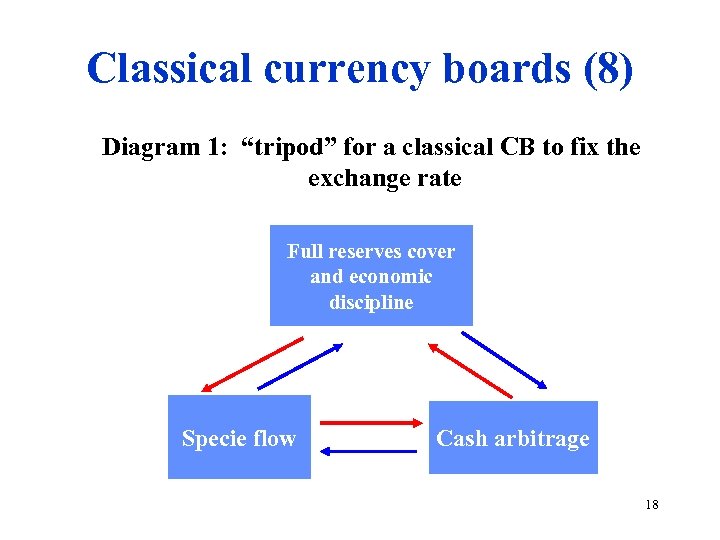

III. Classical currency boards (7) • In sum, there are three anchors for a classical currency board: (1) economic discipline because of the 100% foreign reserves requirement for the issuance of currency (so theoretically paper money cannot be increased without a balance of payments surplus); (2) specie flow in the form of interest arbitrage; and (3) exchange rate (cash) arbitrage that binds the spot exchange rate. • As illustrated in Diagram 1, these three anchors reinforce one another. 17

Classical currency boards (8) Diagram 1: “tripod” for a classical CB to fix the exchange rate Full reserves cover and economic discipline Specie flow Cash arbitrage 18

IV. Classical currency boards and modern monetary economy (1) • The inefficiency of cash arbitrage in a modern monetary economy is however a big problem. In HK, for example, there are only about 7 dollars of cash for every 100 dollars of bank deposit. Moreover, just 50 cents of the cash are in the hands of banks. • If people engage actively in converting their deposits into cash to do arbitrage, it will be equivalent to a bank run. 19

IV. Classical currency boards and modern monetary economy (2) • Since the establishment of the linked exchange rate system, there has been very little, if at all, cash arbitrage activity. • Between 1983 and 1998, the link was defended with a combination of market interventions including direct foreign exchange operations and manipulation of liquidity and interest rates. 20

V. Modern currency boards and the AEL Model (1) • Argentina, Estonia and Lithuania adopted varieties of the currency board system in 1991, 1992 and 1994 respectively. I have dubbed them as the AEL Model (阿愛立 模式 ). Though latecomers, all three AEL countries used an improved version of the system. It overcame the problem of cash movements for arbitrage, with which Hong Kong was struggling. 21

V. Modern currency boards and the AEL Model (2) • They instituted a reserves system whereby each bank had an account with the central bank, in which any reserves for notes and deposits as well as the clearing balances were kept. The central bank guaranteed the full convertibility of all the claims of each bank, at the fixed exchange rate. In effect, the convertibility undertaking (兌換保 証 )covers the whole monetary base (整個貨幣 基礎 ), i. e. essentially all the domestic liabilities of the central bank, and not only cash. This set-up bypassed the problem of moving cash around for arbitrage. 22

V. Modern currency boards and the AEL Model (3) • Under such a system, no banks will dare quote an exchange rate that deviates from the official rate, say 7. 80. If Bank A quotes a rate of 8. 00, Bank B can immediately sell US$ 1 million to it, fetching HK$ 8 million, with an instruction that Bank A transfers the amount to its account at the central bank, which will convert HK$ 8 million into US$ 1. 026 million for Bank B at the fixed rate of 7. 80. A profit of US$26, 000 then goes to Bank B. Other banks will also be jumping at the arbitrage opportunity if Bank A does not change its quote. 23

V. Modern currency boards and the AEL Model (4) • Note that no cash movements are involved in all these electronic transactions (電子交易 ), as the central bank plays the role of settling arbitrage activities between banks by providing the necessary foreign reserves. The market exchange could only deviate from the official rate for the small amount of transaction costs involved, if at all. • With this improved currency board system, Argentina, Estonia and Lithuania were able to ensure 100 per cent stability in their spot exchange rates. 24

V. Modern currency boards and the AEL Model (5) • In 1995, Argentina faced serious crises: – 20 per cent of bank deposits were lost in less than three months; – sixty banks folded up; – economic growth rate was a negative 4. 6%; and – unemployment shot up to 16%. • Yet the spot market exchange rate adhered strictly to the official rate (of 1 peso against 1 US$). 25

V. Modern currency boards and the AEL Model (6) • The same “miracle” occurred in Lithuania. A banking crisis broke out in December 1995: – The nation's two largest banks were closed. – Deposits fell by 15% in the first quarter of 1996. • Yet the official rate of 4 litas against 1 US dollar was not challenged at all. 26

VI. Hong Kong’s currency board before and after the 7 technical measures (1) • Between 1984 and April 1998, the Hong Kong currency board system did not behave according to theory of the classical currency board. The key problem was that there was no effective currency arbitrage mechanism. Cash-based arbitrage was a non-starter, because it represented a very small, and increasingly small, % of total money supply. There was simply very little cash to use for arbitrage. 27

VI. Hong Kong’s currency board before and after the 7 technical measures (2) • Other than the CIs, there were no explicit reserves backing or convertibility undertaking. As a result, currency arbitrage outside cash could not be carried out. The monetary authority had to depend on the manipulation of interbank liquidity and interest rates, as well as outright intervention in the foreign exchange market to defend the Hong Kong dollar. Some would call that “central banking in disguise”. 28

VI. Hong Kong’s currency board before and after the 7 technical measures (3) • In the meantime, HK embarked on a process of strengthening monetary control. In 1988, the Accounting Arrangements were imposed, giving the monetary authority an indirect handle on banking liquidity. In the 1990 s, the issuance of EFBNs (Exchange Fund bills and notes), the setting up of the LAF (liquidity adjustment facility), and the eventual establishment of the HKMA (Hong Kong Monetary Authority) were key milestones. 29

VI. Hong Kong’s currency board before and after the 7 technical measures (4) • The HKMA made it known that it would defend the Hong Kong dollar by having flexible ways to manipulate the monetary base and to influence interest rates. • Mr. Andrew Sheng, then Deputy Chief Executive of the HKMA, said on the heel of the Mexican crisis, “. . in recent years the HKMA has introduced various reforms to its monetary management tools, or more aptly, our monetary armoury, to maintain exchange rate stability. ” 30

VI. Hong Kong’s currency board before and after the 7 technical measures (5) • “. . . As was seen in January (1995), our determination to use the interest rate tool was sufficient to deter further speculation against the HK dollar. In fact, currently, the HK dollar is at a stronger level than it was at 1994 year end. ” (Sheng, 1995, p. 60) “To the extent that the HKMA intervenes through the use of foreign exchange swaps, any increase in the monetary base is fully backed by foreign exchange. We use a whole range of instruments in influencing the level of interbank liquidity to manage interbank interest rates, and consequently, maintain exchange rate stability. ” (p. 61) 31

VI. Hong Kong’s currency board before and after the 7 technical measures (6) • In October 1997, the Hong Kong dollar suffered a strong speculative attack. Doubts were cast on the nature and the robustness of Hong Kong’s currency board. A controversy arose concerning whether and to what extent the HKMA did intervene in the markets on 23 October 1997, and was therefore responsible for the unprecedented high interest rates---with overnight interbank rates going up to 280% at one point. 32

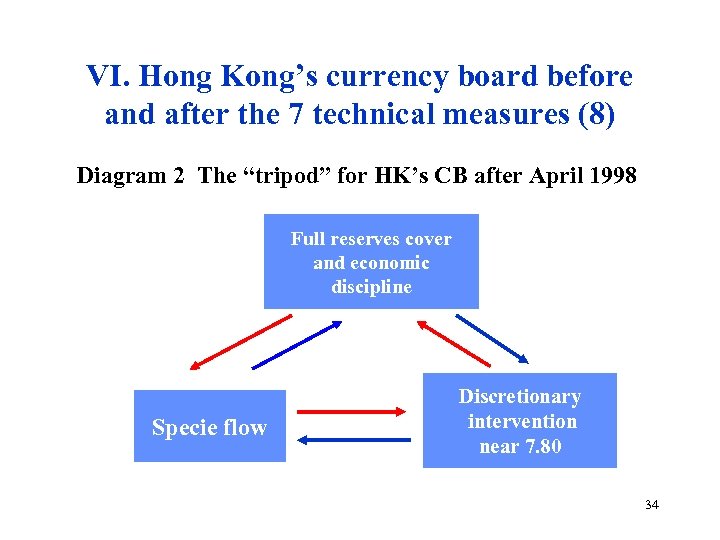

VI. Hong Kong’s currency board before and after the 7 technical measures (7) • In April 1998, the HKMA announced a commitment not to actively manage the clearing balance of the banking system to defend the exchange rate (FSB, 1998, paras. 3. 36 -3. 41; Annex 3. 5), the HKMA would keep to the rule of automatic adjustment. • However, the HKMA reserved the option of discretionary intervention to defend the exchange rate near the 7. 80 level. 33

VI. Hong Kong’s currency board before and after the 7 technical measures (8) Diagram 2 The “tripod” for HK’s CB after April 1998 Full reserves cover and economic discipline Specie flow Discretionary intervention near 7. 80 34

VI. Hong Kong’s currency board before and after the 7 technical measures (9) • The intervention in the stock and futures markets by the Hong Kong government in August 1998 touched off a huge controversy. On 5 September 1998, the HKMA announced seven technical measures (七項 技術措施 ) to strengthen the link. These measures can actually be grouped into two categories: (1) the convertibility undertaking (CU) that banks could exchange their Hong Kong dollar balances with the HKMA into US dollars at the fixed exchange rate of 7. 75; and (2) the replacement of the Liquidity Adjustment Facility (LAF) by a formal Discount Window (with no penalties against frequent users). 35

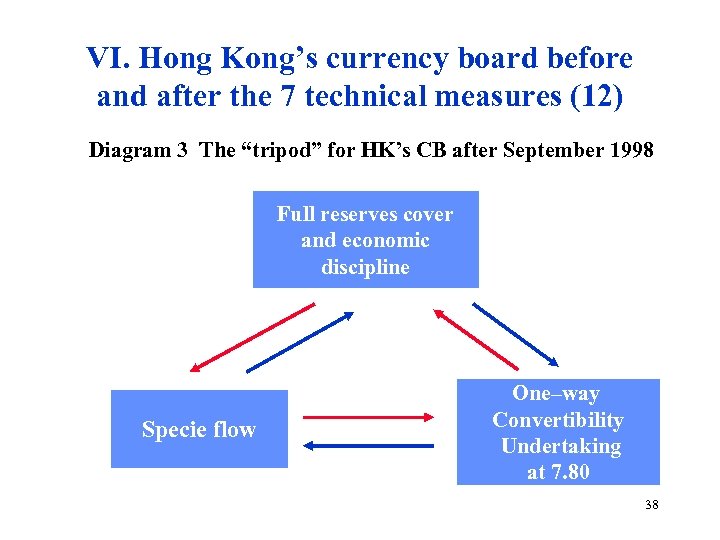

VI. Hong Kong’s currency board before and after the 7 technical measures (10) • The first move means that the coverage of convertibility was effectively extended from bank notes to the whole monetary base. The Discount Window, on the other hand, enlarged the monetary base. As said above, a system of convertible reserves is the core mechanism in the AEL (Argentina, Estonia and Lithuania) Model of modernised currency board arrangements. The new tripod of CB that the HKMA instituted in September 1998 can be depicted as in Diagram 3. 36

VI. Hong Kong’s currency board before and after the 7 technical measures (11) • It was a partial adoption of the AEL model. The CU was one-way (單向兌換保証 ) (on the weak side) only, but currency arbitrage ensured that the 7. 80 fixed rate could not be breached. Further tidying up of the system since then included the 500 -day shift of the CU rate from 7. 75 to 7. 80, the increase in the transparency of currency board operations and the changes in the transferability and convertibility among the components of the monetary base etc. 37

VI. Hong Kong’s currency board before and after the 7 technical measures (12) Diagram 3 The “tripod” for HK’s CB after September 1998 Full reserves cover and economic discipline Specie flow One–way Convertibility Undertaking at 7. 80 38

VII. Hong Kong’s currency board and the three refinements (1) • Since late 2003, speculative pressure on a revaluation of the Chinese renminbi rose and there were large inflows into Hong Kong, leading to near zero short term interest rates, large aggregate balances and strong spot rates for the HK dollar (at one point to about 7. 70). 39

VII. Hong Kong’s currency board and the three refinements (2) • The very low interest rates failed to generate sufficient and effective interest arbitrage to offset the revaluation pressure, i. e. to weaken the exchange rate to the 7. 80 level supposedly as a result of outflow of funds. • This was the reverse of the difficulty experienced before the seven technical measures of September 1998. Then very high interest rates were not powerful enough in strengthening the HK dollar against devaluation pressure supposedly through attracting inflow of funds. • Hence a two-way CU (雙向兌換保証 ) seemed necessary. 40

VII. Hong Kong’s currency board and the three refinements (3) • On May 18, 2005, the HKMA introduced the three refinements (三項優化措施 ): 1) a strong-side Convertibility Undertaking by the HKMA to buy US dollars from licensed banks at 7. 75; 2) the shifting over 5 weeks of the existing weak-side Convertibility Undertaking by the HKMA to sell US dollars to licensed banks from 7. 80 to 7. 85, so as to achieve symmetry around the Linked Rate of 7. 80; 41

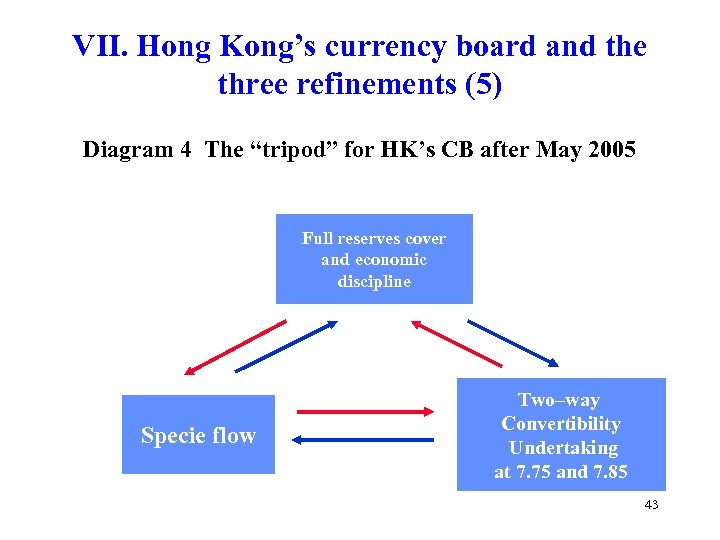

VII. Hong Kong’s currency board and the three refinements (4) 3) within the zone defined by the levels of the Convertibility Undertakings (the "Convertibility Zone"), the HKMA may choose to conduct market operations consistent with Currency Board principles. These market operations shall be aimed at promoting the smooth functioning of the Linked Exchange Rate System, for example, by removing any market anomalies that may arise from time to time. • With these three refinements, the latest currency board system can be depicted as follows: 42

VII. Hong Kong’s currency board and the three refinements (5) Diagram 4 The “tripod” for HK’s CB after May 2005 Full reserves cover and economic discipline Specie flow Two–way Convertibility Undertaking at 7. 75 and 7. 85 43

VII. Hong Kong’s currency board and the three refinements (6) • The “wide corridor” of 7. 75 -7. 85: The convertibility zone (兌換範圍 ) is regarded as very wide by some commentators but vulnerable to speculation by others. In my article “Liquidity management, two-way CU …. ”, I discussed the possibility of a powerful speculator “pushing the exchange rate up and down the corridor” of 50 pips” (http: //www. sktsang. com/Archive. I/Tsang 021201. pdf) 44

VII. Hong Kong’s currency board and the three refinements (7) • “From this perspective, a two-way CU with no spread would kill its fun. ” The problems that this generates are familiar. The foreign exchange market in HKD/USD will be displaced, leading to layoffs. (Some could argue that it is a matter of sacrificing private interests for the sake of the public good. ) Moreover, imagine a CU with no spread and a near-zero AB in an international financial centre. I can’t honestly recommend it as a “solution” and I didn’t, especially given Hong Kong’s post-1998 developments. 45

VII. Hong Kong’s currency board and the three refinements (8) • What is the alternative? Interestingly, we have to travel some distance to find it. A convertibility zone of hundreds of pips would mean that any speculating party, in spite of its market power, faces a relatively “spacious corridor” and the risk and cost of his actions are increased. • See Tsang Shu-ki, “The convertibility zone and operations to remove market anomalies” (www. sktsang. com/Archive. I/Convertibility zone and anomalies. pdf) 46

VII. Hong Kong’s currency board and the three refinements (9) • I remember long time ago I used to play one-a-side (plastic) football games with my younger brother in the narrow corridor of our old home. The “goals” were simply conceived to exist at either end of the corridor, but “long-range” shooting was forbidden. Being physically stronger, I always resorted to the ploy of kicking the ball to one side and then speeding past him on the other to collect the ball back after its rebound from the wall. The rest was peanut. 47

VII. Hong Kong’s currency board and the three refinements (10) • What if the corridor had been quite wide? The rebound from the wall, from whether the left or the right, would have taken longer to reach me. So my little brother would have had time to turn around and chase the ball almost on a par with me. I would not have had the easy job of rushing it towards an open “goal”. • A convertibility zone is a trade-off between stability as well as credibility on the one hand, and liquidity and flexibility on the other. • This is a reality for the CBA in Hong Kong, which is an international financial centre with huge daily capital flows. Too rigid a system would mean that any pressure cannot be shared by several “buffer” variables. 48

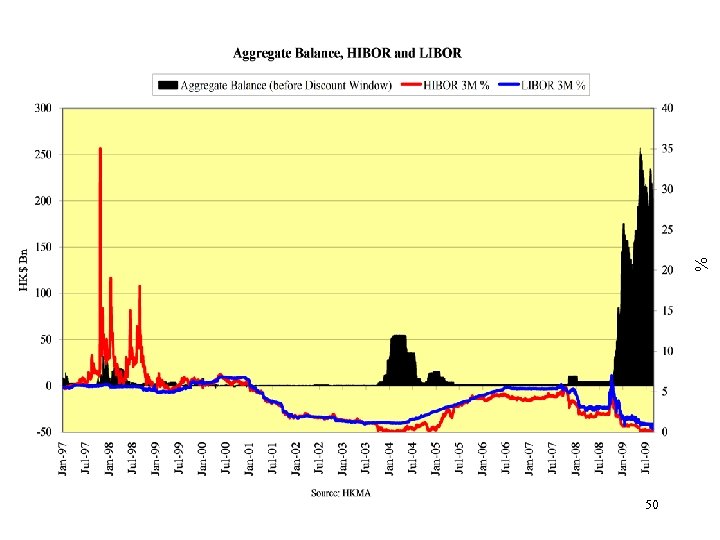

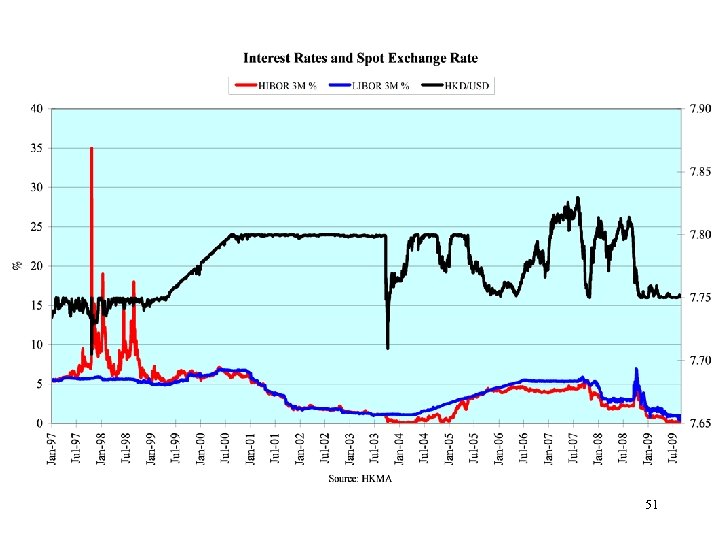

VII. Hong Kong’s currency board and the three refinements (11) • However, a consequence of this “flexibility” is the phenomenon of “multiple equilibria” among the spot exchange rate, the interest rate and the aggregate balance. And there is “no mean-reverting tendency” towards 7. 80 as our “linked exchange rate”. • In a period of global financial disturbances from outside, these non-reverting phenomena involving different variables are going to become more pronounced. In any case, the currency board system in HK would probably remain intact. Any cost, if at all, would be borne by other economic variables. 49

% 50

51

VII. Hong Kong’s currency board and the three refinements (12) • In the aftermath of the latest financial tsunami, the aggregate balance has risen to historically unprecedented levels, with interest rates falling to near zero. Yet the exchange rate has been consistently strong, close to the CU of 7. 75. Actually the CU has been triggered on quite a number of occasions. • This is a testimony to the robustness of the currency board system in Hong Kong. • One risk is of course that there might be a drastic swing to the weak-side CU of 7. 85, if internal and/or external shocks arise. 52

VIII. The prospects for currency boards (1) • The currency board system is supposed to be the most disciplined and transparent fixed exchange rate regime in the world. • Through arbitrage in a situation of sufficient reserves covering the monetary base and sound banking, the efficiency risk of the spot exchange rate is largely eliminated. • However, the systemic risk still remains. 53

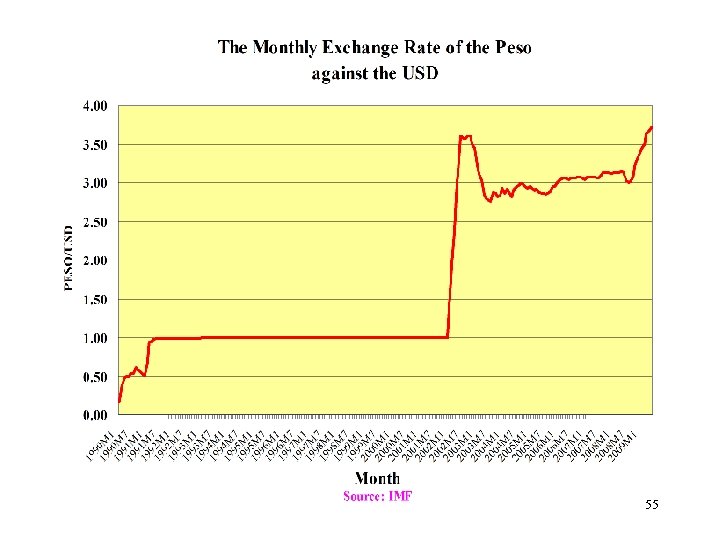

VIII. The prospects for currency boards (2) • Systemic risk refers to the risk of the system being abandoned not because the spot exchange rate cannot be fixed, but as a result of the economic pains associated with a “misaligned” exchange rate or very weak economic fundamentals (e. g. Argentina), and of any decision based on politics. Risk premium will be reflected in interest rates and forward exchange rates. Argentina was forced to abandon the system in early 2002. 54

55

VIII. The prospects for currency boards (3) • The beginning of the end for the AEL Model? Estonia and Lithuania both became a member of the EU in 2004. Both then joined the Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II) and officially stated their objective to adopt the euro soon after the mandatory minimum requirement of two years. Estonia has been maintaining the currency board arrangement with a fixed rate of one euro to 15. 6466 Estonian kroons, while Lithuania’s currency has been pegged at the rate of 3. 4528 litas per euro. 56

VIII. The prospects for currency boards (4) • However, the process is nothing automatic. Both have been on the watch list by the European Central Bank on the basis of convergence criteria and conditions for final accession to the euro area, i. e. the replacement of their own national currencies by the euro. Estonia's effort has been hindered by failing to meet the inflation target (a nominal convergence criterion) set by the EU (Eesti Pank, “Estonia's National Changeover Plan”, July 2009, www. eestipank. info/pub/en/EL/ELiit/euro/eplaan_1. pdf • Lithuania has been bothered by a similar problem, and “according to the current data, the most favourable period for Lithuania to join the euro area will begin from 2010. ” (Lietuvos Bankas, “Adoption of the Euro in Lithuania”, www. lb. lt/eng/euro/index. htm. 57

VIII. The prospects for currency boards (5) • The debate between a fixed exchange rate system and a floating rate regime is a long standing one, and unlikely to be solved any time soon. • In between, there can of course be “basket peg”, “crawling peg”, “target zone”, “managed float”, and their various combinations. • The purists would argue for “corner solutions”: either “hard peg” or “clean float”, as the various combinations suffer from a lack of “credibility”. 58

VIII. The prospects for currency boards (6) • A small open economy with very flexible asset and factor markets will find it beneficial to adopt a fixed rate because the certainty will promote long term investment and facilitate structural changes. • For developing and emerging markets, it will help to impose monetary discipline and promote the development of long-term capital market (and avoid the “original sin”). 59

VIII. The prospects for currency boards (7) • There may be a “fear of floating” for small open economies, because of the absence of a “nominal anchor”. Some have resorted to “inflation targeting” as an alternative. • On the other hand, though, whether the fixed rate is an appropriate one, particularly in times of significant structural or international sea changes, is always a headache. A fixed rate can also become a “sitting duck” for speculators. 60

VIII. The prospects for currency boards (8) • The merit of floating is that it serves as a good “barometer” giving early warning signals about the economy. One could say that it actually imposes continuing discipline on the authorities as well as the private enterprises and they should adjust in time. The demerit is volatility and overshooting typical of financial markets. • Well, the debate will no doubt go on. 61

VIII. The prospects for currency boards (9) • Although the AEL Model is disintegrating, the principles behind its operations are sound and can serve as lessons for aspiring fixed exchange rate regimes, provided that the rate is not misaligned in a fundamental sense and suitable economic policies are implemented to support its viability. • There seems to be little choice for Hong Kong but to stick with the currency board system in the near term. 62

VIII. The prospects for currency boards (10) • In the future, the authorities may consider the possibility of re-pegging the Hong Kong dollar to the Renminbi or even a monetary union with the Mainland. However, many conditions (including the full convertibility of the Renminbi) need to be fulfilled first. 63

References (1) • Blejer, Mario (2003), “Argentina: Managing the Financial Crisis”, a presentation at the World Bank on 22 October 2003 (http: //info. worldbank. org/etools/bspan/Presentation. Vi ew. asp? PID=940&EID=328). • Financial Services Bureau (FSB) (1998), Report on Financial Market Review, Hong Kong SAR Government, April. • Gulde-Wolf, Anne-Marie and Keller, Peter (2002), “Another Look at Currency Board Arrangements And Hard Exchange Rate Pegs for Advanced EU Accession Countries”, in Urmas Sepp and Martti Randveer (eds. ), Alternative Monetary Regimes in Entry to EMU, Eesti Pank, November. 64

References (2) • Hanke, Steve H. and Schuler, Kurt (1994), Currency Boards for Developing Countries, San Francisco: International Center for Economic Research. • Ho, Corrine (2002), “A survey of the institutional and operational aspects of modern-day currency boards”, BIS Working Paper No. 110, March. • Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) (1994), The Practice of Central Banking in Hong Kong. • HKMA (1999), “The currency board account and other fine-tuning measures to strengthen the currency board arrangements in Hong Kong”, Quarterly Bulletin, May, pp. 1 -6. 65

References (3) • Latter, Anthony (1993), “The currency board approach to monetary policy--from Africa to Argentina and Estonia, via Hong Kong”, Monetary Management in Hong Kong, Hong Kong Monetary Authority, proceedings of the Seminar on Monetary Management. • Nenovsky, Nikolay and Rizopoulos, Yorgos (2003), “Extreme Monetary Regime Change: Evidence from Currency Board Introduction in Bulgaria”, Journal of Economic Issues, vol. XXXVII, no. 4, December 2003. 66

References (4) • Nugée, John (1995), “A brief history of the Exchange Fund”, Quarterly Bulletin, Hong Kong Monetary Authority, May, pp. 1 -17. • Sheng, Andrew (1995), “The linked exchange rate system: review and prospects”, Quarterly Bulletin, Hong Kong Monetary Authority, May, pp. 54 -61. • Tsang, Shu-ki (1999 a), A Study of the Linked Exchange Rate System and Policy Options for Hong Kong, consultancy report, Hong Kong Policy Research Institute, submitted in October 1996 and published in full in January 1999. 67

References (5) • Tsang, Shu-ki (1999 b), “Legal Frameworks of Currency Board Systems”, HKMA Quarterly Bulletin, August 1999. • Tsang, Shu-ki (1999 c), “Fixing the Exchange Rate through a Currency Board Arrangement: Efficiency Risk, Systemic Risk and Exit Cost”, Asian Economic Journal, 13(3), pp. 239 -266. • Tsang, Shu-ki (1999 d) “The Currency Board Arrangement in Hong Kong: Viability and Optimality Through the Crisis”, in Rising to the Challenge in Asia: A Study of Financial Markets: Volume 3 - Sound Practices, Asian Development Bank. 68

References (6) • Tsang, Shu-ki (2004), “One country, two monetary systems: Hong Kong and China”, in Suthiphand Chirathivat, Emil. Maria Claassen and Jürgen Schroeder (eds. ), East Asia's Monetary Future: Integration in the Global Economy, Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 42 -60. • 曾澍基,(2006), 香港联系汇率的回顾与展望 〉 載 《 〈 , 全球化和区域经济一体化中的香港经济 》 ,陈广汉、 袁持平主编,广州:中山大学出版社,頁 237 -258。 • Tsang, S. K. , (December 2007), “ Fixing the Exchange Rate for an International Financial Center: The Case of Hong Kong”, International Business and Finance Issues, in Alan N. Kendall(ed. ), Nova Science Publishers : 223 -242. • Yam, Joseph (1999), A Modern Day Currency Board System, Hong Kong Monetary Authority. 69

f9bb50f733ac229d374ed4f823315bad.ppt