ec04cab03283187a64dcc5546b3af9b3.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 47

Cultural studies: Studying popular culture http: //johncmullen. blogspot. com

What is Popular Culture? ____________________ Popular culture can be defined (cf. Storey): 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. quantitatively: culture of the many - forms widely favored residually: denoting all that is not high culture as being same as mass culture (commercialized) as culture originating from the “people” as culture of resistance Related culture concepts: grassroots, popular, common, mass, élite, high-middle-low brow

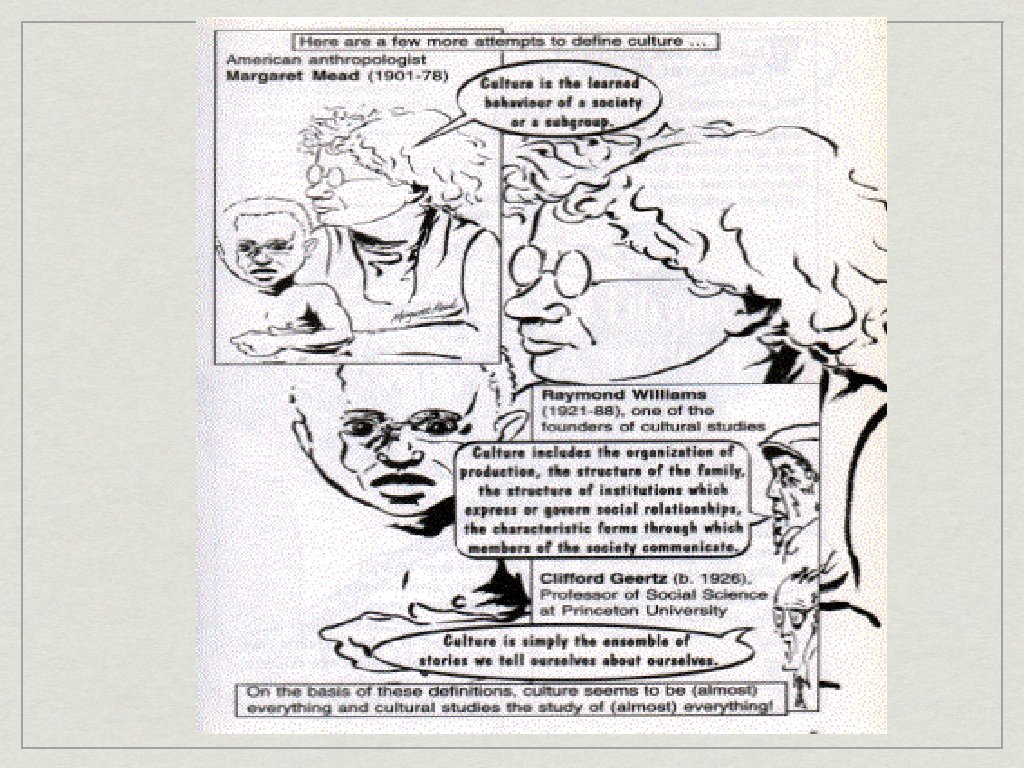

Culture: approaches and definitions ____________________ E. B. Tylor (1871): Culture is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, customs, and other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society M. Mead (1960 s): Culture is a learned behavior of a society or a subgroup R. Williams (1970 s): Culture includes the organization of production, the structure of the family, the structure of institutions which express or govern social relationships, the characteristic forms through which members of the society communicate C. Geertz (1980 s): Culture is simply the ensemble of stories we tell ourselves about ourselves But we often concentrate on the leisure activities which are part of culture,

Theodor Adorno We will spend some time on Adorno because he was the grandfather of the study of popular culture, even though his opinion about it was very negative Adorno was denied a teaching position at a university because he was Jewish. Dialectic of the Enlightenment written 1944, published 1947 One of the first writer to systematically write about popular culture… even if from a rather negative standpoint,

Adorno asked important new questions: Why does popular music make so much money? What does it do for people? What is its aesthetic and psychological value? What happens when people listen to it? How does it affect their lives?

Reading Adorno is a member of the Frankfurt school of philosophers and social critics. These thinkers were (are) influenced by some of the writings of Karl Marx, and also by Freudian ideas; they use these ideas as tools for social criticism. Adorno uses Marx’s idea of “commodity fetishism” to analyze the phenomenon of popular music.

More background on Adorno is not only a philosopher but a musician and composer, a student of Schoenberg’s student Alban Berg. The “popular music” Adorno is writing about is jazz in the late 1930’s. But his ideas are at least as easy to apply to contemporary popular music as they were for the jazz of his day.

Adorno’s basic idea Music – both popular and the classical music played in concert halls and on the radio – is driven primarily by commercial interests. “Music, with all the attributes of the ethereal and sublime which are generously accorded it, serves in America today as an advertisement for commodities which one must acquire in order to be able to hear music. ”

The basic idea (continued) In other words, commercial music exists to sell CD’s, stereos, i-pods and concert tickets rather than these things existing to make music available. Both the music makers and the listeners have become submerged in the commercial process, and neither is really musically free.

Commodity fetishism A fetish is a substitute object of desire. So, in the most familiar kind of case, sexual desire might be displaced onto garments worn by the individual whom one cannot, for whatever reason, directly desire or have. Karl Marx said that commodities can be fetishes. In this case, the displaced desire is the desire for freedom, and for the fruits of your labor. Here’s what happens. You are alienated (estranged, separated) from the fruits of your labor. The products you help make are too far from your control for you to recognize them as your own. In return for your labor, you get pounds sterling, which are only a small percentage of the value you have added to the product.

Commodity fetishism (continued) According to Marx…. the relation of the producers to the sum total of their own labor is presented to them as a social relation existing not between themselves, but between the products of their labors. ’”

Commodity fetishism (cont. ) So instead of a relationship between you and some musicians, who might play for you in exchange for some service you would render to them, there is now a relationship between your dollars and their CD. But the dollars and the CD are part of a capitalist system that is driven by the need to make money, not the need to make and hear good music.

Popular (and classical) music as “fetish” What do you really like when you like a popular song, a rap concert, or a performance at the symphony? Not the music, says Adorno. Rather, it’s the (illusory) feeling of your own wealth (when you buy the concert ticket); the feeling of belonging, of being “cool”, when you like what is popular, or of being “individual” when you like “alternative” music or “non-commercial” rap.

The Culture Industry “The culture industry fuses the old and familiar into a new quality. In all its branches, products which are tailored for consumption by masses, and which to a great extent determine the nature of that consumption, are manufactured more or less according to plan” Adorno in « The Culture Industry reconsidered »

“People know what they want because they know what other people want” (Adorno)

. . . But can it deliver? “The culture industry does not sublimate; it represses. By repeatedly exposing the objects of desire, breasts in a clinging sweater or the naked torso of the athletic hero, it only sublimates the unsublimated forepleasure which habitual deprivation has long since reduced to masochistic semblance” (1117 -8).

Adorno on pop music …some of its principal characteristics are: unabating repetition of some particular musical formula comparable to the attitude of a child incessantly uttering the same demand (‘I want to be happy’); the limitation of many melodies to very few tones, comparable to the way in which a small child speaks before he has the full alphabet at his disposal. . Treating adults like children is involved in that representation of fun which is aimed at relieving the strain of their adult responsabilities. Theodor Adorno, Essays on Music (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 445.

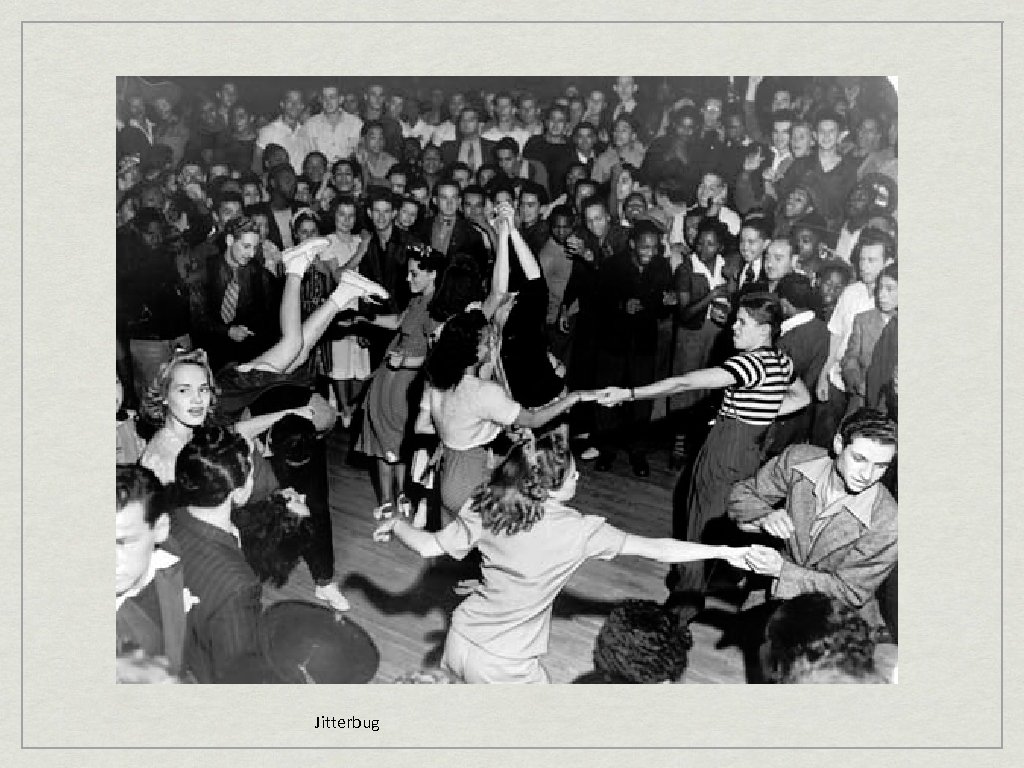

Jitterbug

On music for dancing in order to become a jitterbug or simply to ‘like’ popular music, it does not by any means suffice to give oneself up and to fall into line passively. To become transformed into an insect, man needs that energy which might possibly achieve his transformation into a man. Adorno, Essays on Music, 468.

Regressive Listening The commodity system of music requires regressive (i. e. , childish) listeners. “Their (our) primitivism is not that of the undeveloped, but of the forcibly retarded. Whenever they have a chance, they display the pinched hatred of those who really sense the other but exclude it in order to live in peace…. ”

A simplistic representation of Adorno’s position

Objections to Adorno’s analyses (in particular of popular music) - 1. Empirical studies do not support his views “The idea of the industry foisting rubbish more or less at will on a totally passive audience is facile. If it could do so it would, but it can not. Most records are not hits, the industry is notoriously slow in picking up on crazes and audiences soon tire of artists who are hyped into the charts. ” Martin Cloonan

2. Adorno only considers reflexive listening to be valuable, but this is a culture-bound judgement. 3. If Adorno was right, then changes in popular music would never accompany real changes in society. Punk and rap for example would not correspond to any social change. 4. He supposes a monumental quantity of false consciousness.

The result is that Adorno’s theories are regarded today as ‘largely obsolete and unscientific, in the eyes of the cultural historian who is preoccupied with understanding both systems of production and the development of the symbolic landscape of a given society’. Ludovic Tournès, ‘Reproduire l’œuvre: la nouvelle économie musicale’, in La Culture de Masse en France, ed. Jean-Pierre Rioux and Jean-François Sirinelli (Paris: Fayard, 2002), 221 [Translation: JM].

« Le culte de la culture populaire n'est, bien souvent, qu'une inversion verbale et sans effet, donc faussement révolutionnaire, du racisme de classe qui réduit les pratiques populaires à la barbarie ou à la vulgarité : comme certaines célébrations de la féminité ne font que renforcer la domination masculine, cette manière en définitive très confortable de respecter le « peuple » , qui, sous l'apparence de l'exalter, contribue à l'enfermer ou à l'enfoncer dans ce qu'il est en convertissant la privation en choix ou en accomplissement électif, procure tous les profits d'une ostentation de générosité subversive et paradoxale, tout en laissant les choses en l'état, les uns avec leur culture ou leur (langue) réellement cultivée et capable d'absorber sa propre subversion distinguée, les autres avec leur culture ou leur langue dépourvues de toute valeur sociale ou sujettes à de brutales dévaluations que l'on réhabilite fictivement par un simple faux en écriture théorique. » — Pierre Bourdieu, Méditations pascaliennes, Seuil, 1997

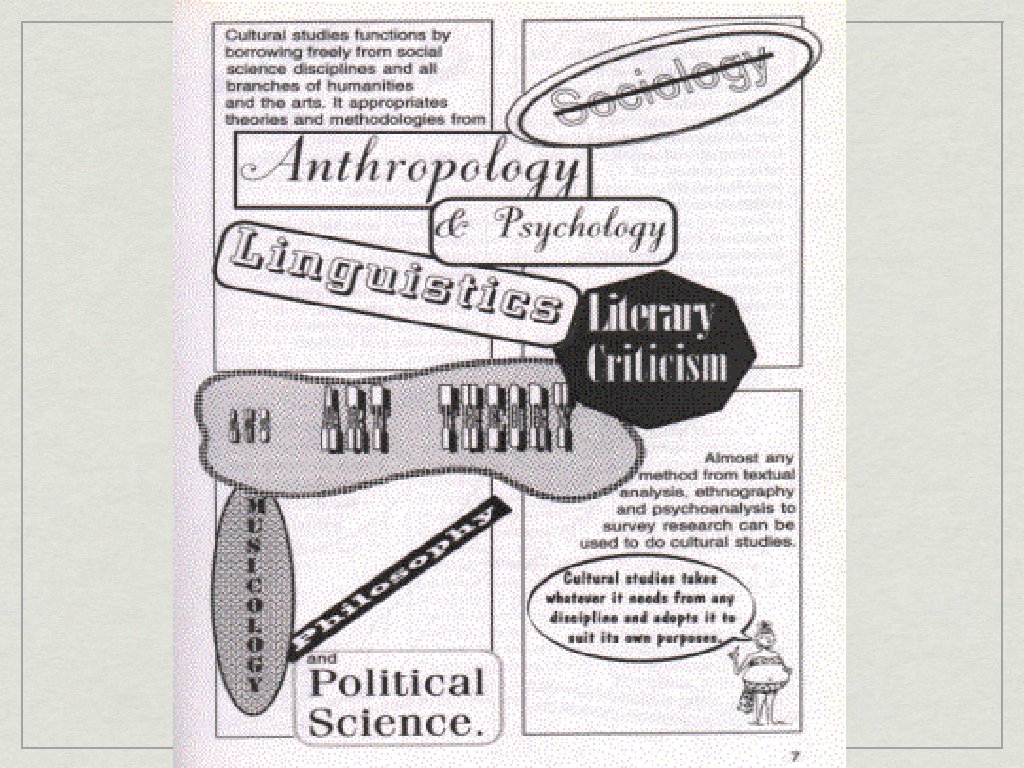

Culture as an object of study ____________________ Subject area not clearly defined: all-inclusive notion of culture and study of a range of practices Principles and theories from social sciences disciplines, the humanities, and the arts are adapted to the purposes of cultural analysis Methodologies : textual analysis, ethnography, psychoanalysis, survey research, etc.

What is Cultural Studies? ____________________ Study of culture rather than society Examines cultural practices in their relationship to power; how power shapes these practices Progressive, radical, political, at the outset

Historical background ____________________ Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) established in 1964 Working Papers in Cultural Studies in 1972 Forefathers: Richard Hoggart, Raymond Williams, E. P. Thompson, Stuart Hall Studied role of popular culture in class-based society in England

R. Hoggart & R. Williams ____________________ Working class intellectuals The culture of common people (working class culture) seen as more authentic than middle- and upper-class culture; derives from experience Against canonical élitism Mass culture seen as “colonizing”working class culture

Hoggart regrets what he sees as the break-up of the old, class culture, lamenting the loss of the close-knit communities and their replacement by the emerging manufactured mass culture. Key features of this are the tabloid newspapers, advertising, and the triumph of Hollywood. These "alien" phenomena, he believes, have colonized local communities and robbed them of their distinctive features.

R. Hoggart ____________________ Founder of CCCS The Uses of Literacy (1957) programmatic work; parts of it written as a manifesto Critical reading of art needs to reveal the “felt quality of life” of a society; art captures the experience of the everyday as the unique

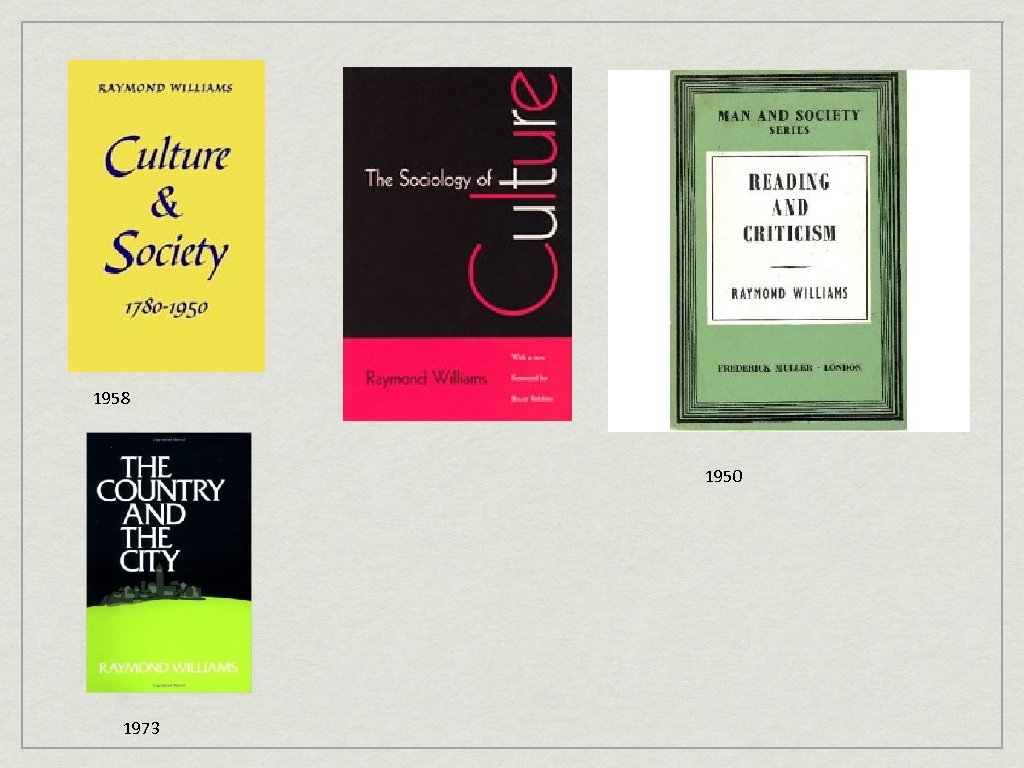

1958 1950 1973

R. Williams ____________________ Marxist tradition Culture is an expression of the coherence of organic communities resisting determinism in its various forms Culture: material, intellectual and spiritual (base and superstructure in the marxist sense), Centrality of texts that capture “the structure of feeling” of everyday life, the sense of an époque. He speaks of dominant, residual and emergent ideologies and cultural forms

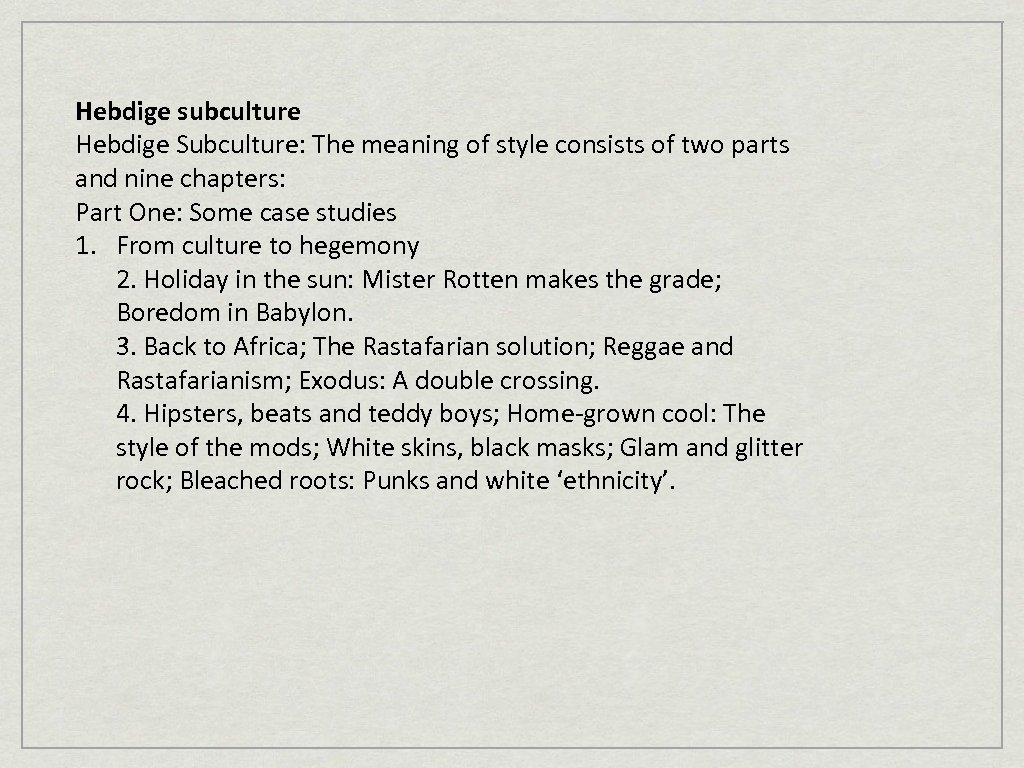

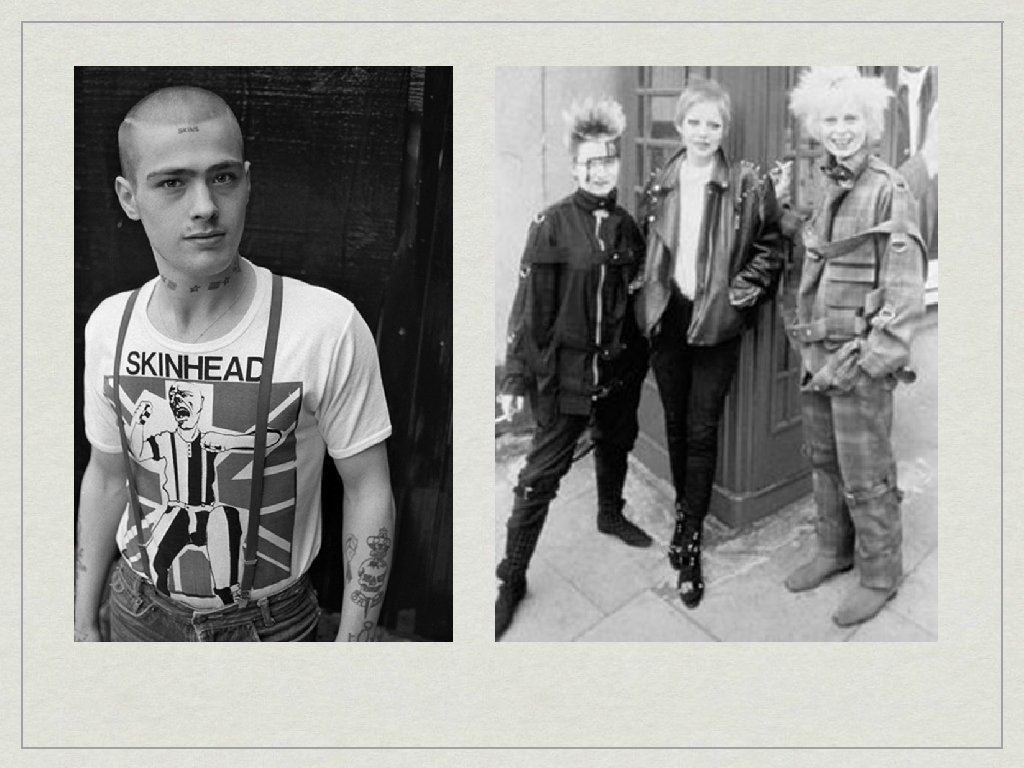

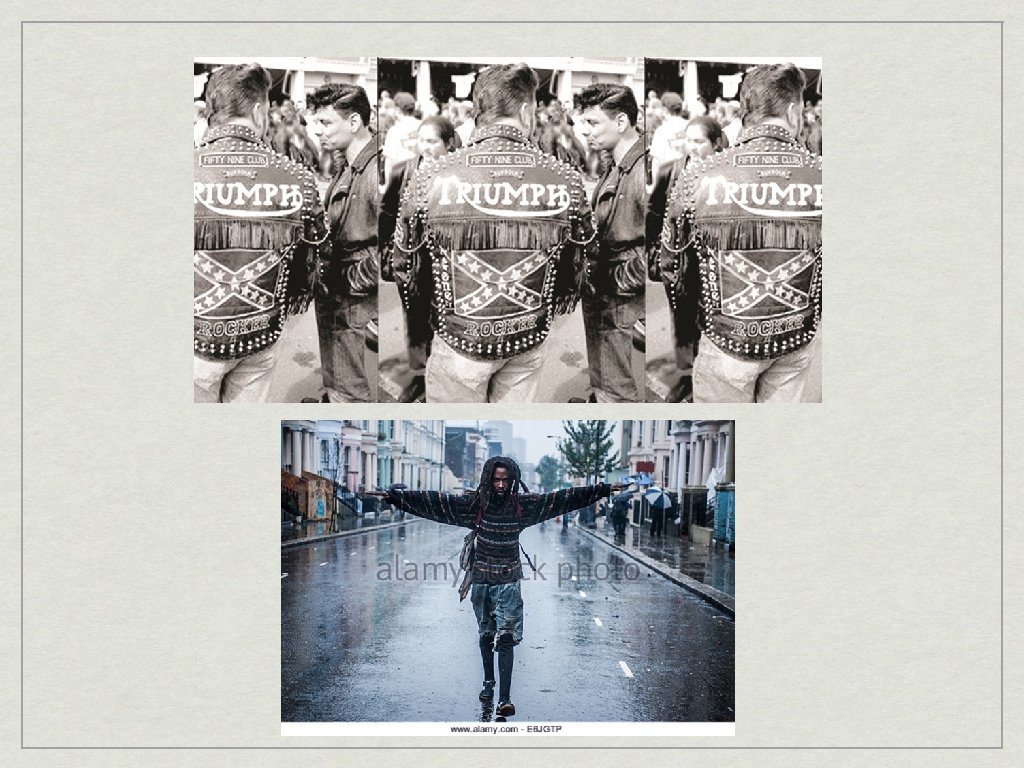

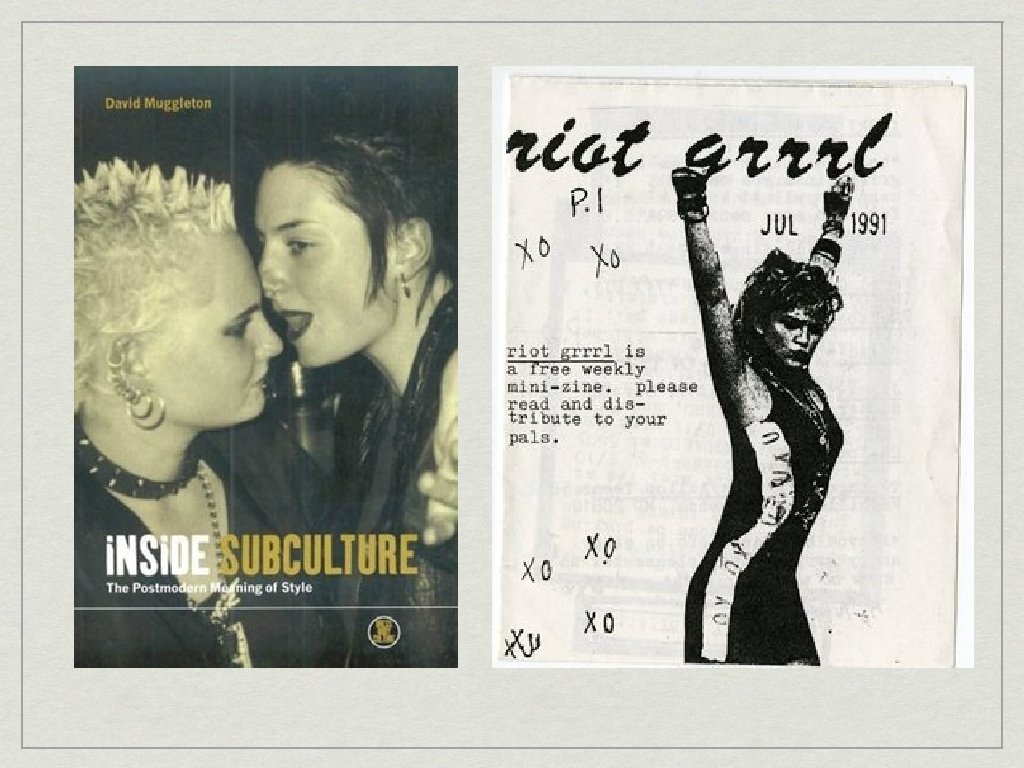

Hebdige subculture Hebdige Subculture: The meaning of style consists of two parts and nine chapters: Part One: Some case studies 1. From culture to hegemony 2. Holiday in the sun: Mister Rotten makes the grade; Boredom in Babylon. 3. Back to Africa; The Rastafarian solution; Reggae and Rastafarianism; Exodus: A double crossing. 4. Hipsters, beats and teddy boys; Home-grown cool: The style of the mods; White skins, black masks; Glam and glitter rock; Bleached roots: Punks and white ‘ethnicity’.

Part Two: A reading 5. The function of subculture; Specificity: Two types of teddy boy; The sources of style. 6. Subculture: The unnatural break; Two forms of incorporation. 7. Style as intentional communication; Style as bricolage; Style in revolt: Revolting style. 8. Style as homology; Style as signifying practice. 9. O. K. , it’s Culture, but is it Art?

ec04cab03283187a64dcc5546b3af9b3.ppt